Abstract

Natural playgrounds in early childhood education support children’s development and environmental awareness by offering various experiences. However, in many kindergartens, natural playgrounds are insufficient, and it is emphasized that playgrounds should be improved through participatory design processes carried out with children. The aim of this study is to identify the spatial expectations of five-year-old children regarding natural playgrounds by involving them in a participatory design process at a kindergarten in Bursa, Türkiye. A multi-method approach was developed by combining age-appropriate techniques for children within participatory design workshops. Children’s explanations of their designs were evaluated through reflexive thematic analysis, resulting in the emergence of eight themes that reflect their spatial expectations for the design of natural playgrounds. The study revealed the play actions children wish to perform, the experiences they desire, and the natural spaces and spatial elements they designed. The findings show that five-year-old children were able to collaboratively design a natural playground through a participatory process. This research highlights the need to increase participatory design practices with children in order to create natural playgrounds that support children’s holistic development in kindergartens.

1. Introduction

In early childhood education environments (ECEEs), several barriers to outdoor play exist, including school readiness pressure, safety concerns, and a lack of playgrounds. The quality of outdoor playgrounds is often overlooked, with restrictions on both their design and access, leading to reduced time spent outdoors [1,2,3,4]. These playgrounds, generally equipped with traditional structures and limited greenery, often fail to offer truly ‘natural’ experiences [3,5]. It is stated that such playgrounds may overlook children’s holistic development [6,7]. Children also criticize the limited play opportunities in equipment-based playgrounds and prefer natural playgrounds [8,9]. They perceive the natural environment as a beautiful setting and express happiness from being there [10]. Children are more likely to engage in manipulative activities, use natural materials, and explore a wider range of challenging opportunities in natural playgrounds [11]. Natural playgrounds can enhance outdoor learning in early childhood education by promoting health, well-being, and a connection with nature, thereby offering rich, hands-on learning experiences [1,12,13]. Therefore, designing natural playgrounds in kindergartens is also important for children’s healthy development [14,15,16].

Participatory studies, where children can voice their opinions and share their experiences, are essential for improving ECEEs [17,18,19,20]. Preschool children are capable of participating in research and developing ideas related to their spaces and can actively contribute to design processes [21,22,23,24,25]. However, research involving preschool children’s perspectives is limited [4,18,26], and their views are often not incorporated into the organization of time and space in ECEEs [4]. It has been suggested that participatory studies be increased within preschool education policies to enhance outdoor space usage [4,14]. Despite acknowledging the importance of outdoor play and the roles children can play in shaping ECEEs, few studies focus on designing playgrounds with children’s participation [8,27,28]. While these studies offer playground designs based on children’s preferences and needs, they were not specifically aimed at participatory natural playground design.

In Türkiye, integrating natural playgrounds into ECEEs is considered a way to enhance the objectives of the preschool education program, emphasizing the importance of outdoor spaces for play, field trips, and morning walks [29]. However, ECEEs are criticized for lacking green spaces, playgrounds, and facilities that meet children’s developmental needs [30,31]. Research indicates that playgrounds in ECEEs lack suitable play materials, essential learning equipment, and natural features, failing to align with children’s interests and needs [32,33]. It is emphasized that playgrounds should be designed collaboratively with children, teachers, and parents, with support from the Ministry and contributions from experts [31]. Despite the importance of participatory design in ECEEs, there are few theoretical studies on this approach [34,35,36,37,38]. In this context, and taking into account the limited outdoor activities in the Preschool Education Program [29], the inadequacy of definitions related to playground design, and criticisms in the literature regarding the lack of participatory design studies with children, this study has been designed to develop natural playgrounds in kindergartens through a participatory design process with children.

Within this framework, a research project defining a participatory design model for natural playgrounds in kindergartens was conducted in collaboration between the Bursa Provincial Directorate of National Education and Bursa Uludağ University in Türkiye. The originality of this project lies in its participatory approach, which, unlike other studies in the literature, enables 5-year-old children to collaboratively design natural playgrounds in kindergartens and express their expectations through this process. Led by two academicians and two doctoral students from the Department of Architecture, the project is distinctive in that five-year-old children actively participated as designers. To hear the voices of all children, a multi-method approach was developed combining age-appropriate techniques in art-based and knowledge-based methods [18,25,27,28]. The workshops were designed in collaboration with preschool teachers and linked to the Ministry of National Education Preschool Program to support children’s development. The aim of this study is to demonstrate that five-year-old children can collaboratively design a natural playground in kindergartens through a participatory process and to reveal their spatial expectations regarding natural playgrounds within the framework of the following research questions:

- What play actions (affordances) do five-year-old children wish to engage in within natural playgrounds?

- What experiences do five-year-old children desire from a natural playground in a kindergarten?

- What types of spaces and spatial elements can five-year-old children design for natural playgrounds in kindergartens?

2. Background

2.1. The Importance of Natural Playgrounds for Early Childhood and Education

Fostering environmental awareness and sustainable behavior in early childhood education and care (ECEC) is addressed through three key competences: valuing sustainability, promoting nature, and adaptability. Promoting nature enables children to connect with their natural environment, understand the interdependence between humans, plants, animals, and the land, and recognize how human actions can impact nature. The most recurring aspect of promoting nature is encouraging emotional connections (joy, love, wonder) with nature to inspire a desire to protect it [39]. It is essential to provide preschool children with opportunities to engage with, value, and understand the natural world and its biodiversity, foster curiosity, and teach them to act for sustainability [40].

Natural playgrounds offer children a variety of choices and opportunities that cater to their diverse interests and abilities, providing stimulation, excitement, and challenging play. These playgrounds enable children to explore risks, experience achievement, and engage in healthy positive risk-taking that supports their development [41,42]. They can enhance socialization, focus during play, and foster autonomy while reducing stress, boredom, and behavioral issues [8,43,44]. They support children’s activity levels [45] and enhance motor skills, especially through sloping and challenging topographical features [7]. It has been stated that preschool children show a desire to build their own structures with natural materials while playing in nature, and that their problem-solving behaviors develop as they interact with the natural environment [46]. The open and fluid character of nature is reported to create a dynamic space for children’s play, fostering creativity and social participation, as well as supporting responsibility [47]. Early childhood educators view these spaces as valuable for independent exploration, collaboration, creative problem-solving, and building a sense of belonging, self-confidence, and competence [16]. Additionally, it has been noted that play in nature provides children with the opportunity to discover their own abilities and contributes to the development of their emotional regulation [48]. Natural playgrounds, with their connection to plant and animal life, are considered essential for a ‘good’ childhood, offering children rich sensory experiences and supporting their physical, social, emotional, and cognitive development [4]. It is stated that children develop an awareness of protecting flora and fauna by creating shared play stories from their encounters with nature [3].

Natural playgrounds provide diverse play opportunities for children. Nicholson’s [49] loose parts theory suggests that both natural and manufactured open-ended materials support children’s development, allowing for portable, re-designed, and combinable play elements. Gibson’s [50] affordance theory emphasizes the importance of the environment’s role in offering play opportunities that adapt to children’s abilities and perceptions. Heft [51] further categorized outdoor environments, highlighting the functional play opportunities. These studies underline the significance of both natural and manufactured elements in fostering children’s development in natural playgrounds.

2.2. Experiences of Preschool Children in Natural Playgrounds

It has been noted that preschool children prefer playing in natural environments and that these settings offer various play affordances. Norðdahl and Einarsdóttir [10] revealed that children enjoy having diverse play opportunities in outdoor environments such as playing with water and mud, interacting with other living creatures, and engaging in ball games. They also enjoy physically challenging yet safe activities, exploration, social interaction, and creating or finding their own shelter, as well as taking pleasure in aesthetic and beautiful outdoor experiences. Hagen et al. [52] stated that, according to teachers’ observations in kindergarten outdoor play areas, children mostly preferred natural places where they could interact with natural elements and search for small creatures. Cetken-Aktas and Sevimli-Celik [53], based on observations of children’s outdoor play preferences in kindergartens, found that children used grassy areas for various purposes (such as observing insects or playing football), swung on trees, and utilized natural materials like rocks, stones, and branches for different activities. Zamani [54], reported that preschool children showed curiosity toward small changes in the natural environment, animals, and new experiences. Lerstrup and Konijnendijk van den Bosch [5], described that, in forests and playgrounds used by preschool children, they engaged in play actions such as running and rolling on flat and sloped surfaces; hiding and seeking shelter in dens; balancing and jumping on trees, logs, and rocks; and digging, shaping, splashing, and floating objects with sand, soil, mud, and snow. The study also revealed that children observed and collected small creatures in nature, and that fire provided them with affordances to prepare edible foods and sit together around it. Dyment and O’Connell [55], noted that children could use soft surfaces for running, imagining, or watching others; sandpits for building castles, roads, or cakes; and rocks, bushes, and trees for climbing, hiding, or creating forts demonstrating their diverse and imaginative use of natural materials.

These research shows that children prefer natural playgrounds since they engage in various activities and interact with natural elements. In these studies, it was found that children enjoy physical challenges; playing with water (pouring, mixing, floating, observing small animals, etc.) and mud/sand (building structures, burying toys); observing small creatures and caring for animals; playing on sloped surfaces (sliding, rolling, climbing, etc.) and open flat grassy areas (resting, playing ball, running, walking, etc.); interacting with trees by swinging, rocking, or climbing; balancing on trees, logs, stones/rocks, or climbing them; using bridges; cooking over a fire and sitting around it; creating private spaces and finding hidden places (branches, rocks, bushes, and trees); and incorporating loose parts like sticks, leaves, and pine cones into their play) [5,10,53,54,55]. These studies reveal the play affordances that natural environments offer to children, and the findings are primarily based on observations of children’s play.

2.3. Participatory Studies Reflecting Preschool Children’s Expectations of Outdoor Playgrounds

Participatory studies conducted with children are important both for their multi-dimensional development [56,57,58,59] and for designing environments that meet their needs [17,18]. In recent years, participatory studies involving preschool children have increased, with the aim of understanding their expectations for outdoor playgrounds. In these studies, a multi-method approach is used, bringing together visual and verbal tools to provide children with various means of expression, which is in line with the perspective of the Mosaic Approach developed by Clark [18]. There are many studies showing that children express their preferences regarding playgrounds through participation in semi-structured individual interviews, focus group interviews, informal conversations, walking tours, digital photographs, photo preferences, drawings, models, collages, video presentations, storytelling, digital 3D models and by taking part in design workshops that integrate these techniques [4,10,38,47,54,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67].

Among the participatory studies reflecting preschool children’s expectations for outdoor playgrounds, only a few involve children’s active participation in playground design. Rocca et al. [27] aimed to understand five-year-old children’s vision of their ideal kindergarten garden, first enabling children to express their ideas through story-based analyses and observations of the existing area (including old photographs, stories, memories, and drawings), and later through their drawings and the collaborative garden collage they created. Menconi and Grohmann [28], in a playground design project involving children aged 5–10, enabled children to express their ideas through drawings, written texts, and posters used to evaluate the existing space, as well as through the models they created during the design process and by evaluating the 3D digital models developed by university students based on these models. Similarly, Kucks & Hughes [8], in a sensory garden design process involving 4–6-year-old children aimed to develop an approach to outdoor design, enabled children to express their ideas through various techniques such as observation, drawing, model making, and interviews.

Although there are participatory studies reflecting preschool children’s expectations regarding playgrounds, research that actively involves children in playground design is quite limited, and these studies do not specifically focus on designing a natural playground for kindergartens. Therefore, this study aims to present children’s expectations for natural playgrounds in kindergartens through a design they develop, using a model that strengthens their participation in the playground design process.

3. Methods

The participatory design model of this study is structured as adult-initiated, shared decision-making with children, as defined by Hart [21] in his eight-step Ladder of Participation. At this level, adult-led activities are realized with little input from adults, and meaningful input is provided by children, who are involved in every stage of planning and implementation. Their views are not only taken into consideration, but they also actively participate in decision-making. In this study, although the process was initiated by adults, children were intellectually and physically engaged in every stage of the design process. The targeted level of participation aligns with Lansdown’s [68] definition of collaborative participation, which is initiated by adults but carried out in partnership with children. This approach enables children to influence or challenge decisions and processes, and allows them to gradually assume more self-directed roles over time. In this context, the design process also corresponds to the design by children approach described by Lozanovska and Xu [69] in which children act as active designers contributing original and innovative ideas.

3.1. Ethical Considerations

During the development process of the project titled “A Participatory Design Model for Children to Create Natural Playgrounds in Kindergartens”, officials from the Provincial Directorate of National Education, the kindergarten principal, and relevant teachers confirmed that the project aligns with the objectives of the Harezmi Education Model and can be implemented in early childhood education. A protocol was established through an agreement between Bursa Uludağ University and the Bursa Provincial Directorate of National Education. Following this, research permission was granted by the Bursa Provincial Directorate of National Education Research Evaluation Committee, and ethics approval was obtained for the participatory design process. Consent forms outlining the project’s purpose and activities were provided to parents, who gave written consent for their children’s participation. Parents who deemed it appropriate for their children to participate in projects within the scope of the Harezmi Education Model provided consent for this study. In this context, no preliminary interviews were conducted with the parents, and participation in the project was voluntary. On the first day, a presentation explaining the purpose of the project was given to the children, and they were asked whether they wanted to participate; oral assent was obtained from each child. Although the children were willing to participate in the design process, it was also emphasized that they could withdraw from the activity at any time.

Children’s privacy and anonymity were prioritized, and parents consented to using photos for scientific purposes. The children’s abilities and self-expression were respected, allowing them the time and space to share their thoughts. They were encouraged and appreciated for their efforts, without offering outcome-based rewards. The children’s work was not interfered with, and they were allowed to work at their own pace. Reactions to activities were observed for signs of discomfort, and support or the option to leave was offered if necessary. Academic language was avoided, with terms explained in a child-friendly way. In the article, the identities of the children were kept confidential, and while their designs and comments were presented, only codes based on the initials of their names were used.

3.2. Setting

The kindergarten located on the Bursa Uludağ University campus was chosen for the project due to its inclusivity, aiming to involve children from diverse socio-economic backgrounds, including families of academics, administrative staff, service workers, and local residents (Figure 1). The kindergarten’s suitability for the project was also influenced by its garden, which offers opportunities for children to explore nature, and its location within a green campus surrounded by wooded areas. Trudeau [70] also emphasizes the importance of the site location within the natural environment in defining a natural playground. However, while the environment is natural, there are limited alternative play opportunities with standard equipment. The kindergarten is a single-story building with a 1368 m2 indoor area, surrounded by playgrounds on all sides, with an entrance from the east. The total outdoor area is 4739 m2, with the east- and south-facing playgrounds actively used, while the north- and west-facing areas are closed off. These unused spaces contain materials, coops, and plastic playhouses. In the east-facing section of the front playground, there is a neglected adventure play area with wooden elements like balance beams, hanging rings, climbing surfaces, and a tree swing, along with a pergola. Another part of the front playground features wooden play structures such as swings, a slide, wooden picnic tables, a playhouse, a portable plastic seesaw, a toy car, a small slide, and a sandbox (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The location of the kindergarten within the campus of the University and the playground of the kindergarten.

Figure 2.

The views from front playground.

3.3. Participants

A group consisting of 2 teachers and 20 students (11 boys, 9 girls), aged 5 (60–72 months), participated in this project. These students were recommended by the kindergarten administration because they are part of the Harezmi Education Model, which was introduced as a pilot study in 2016 by the Ministry of National Education to enhance critical thinking and problem-solving skills through design. With the motto “think, design, produce together for humanity,” the model promotes a multidisciplinary approach, encouraging collaboration among teachers, parents, school communities, scientists, public institutions, NGOs, and experts [71].

3.4. Workshops

Throughout the design process, the research team provided essential resources and opportunities, yet refrained from any directive involvement, allowing children the autonomy to make decisions and express their ideas freely. Unlike other participatory design workshops, the designs in this study were not critically evaluated, nor were suggestions or ideas provided. In the workshops, the children first expressed their ideas individually and then, through collaborative work, developed these ideas into a joint design proposal. In this process, where adults acted as observers or advisors when needed, the children took the lead in the design process. Throughout the participatory design process, the children presented their original and innovative ideas at every stage.

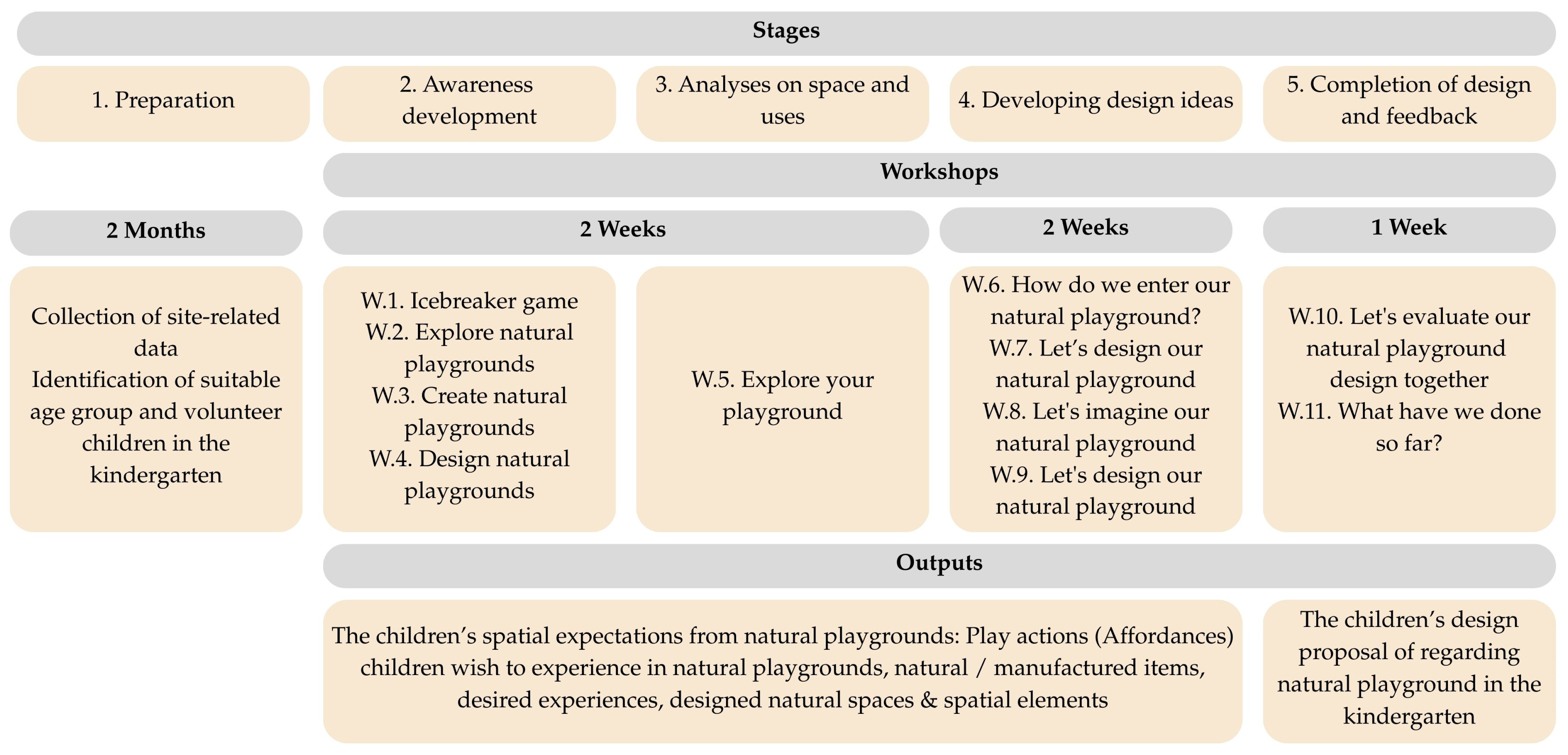

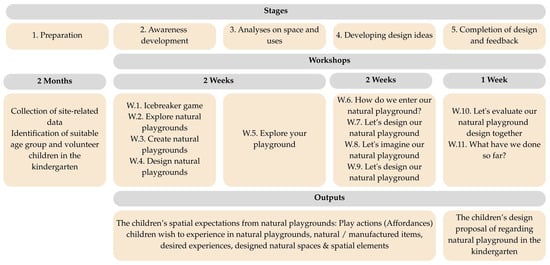

The method in the participatory design model was structured around a five-stage framework and employed a multi-method approach, combining age-appropriate techniques for preschoolers. The stages and context of the participatory design model are summarized below:

(1) Preparation: At this stage, the project’s work plan and schedule were developed together with the Provincial Directorate of National Education, the kindergarten principal, and the relevant teachers. Ethical permissions were obtained. Site-related data were collected by obtaining existing maps of the kindergarten and capturing photographs and video recordings. Additionally, the children who would participate in the study were identified, parental consent was obtained.

(2) Awareness Development: Four workshops were conducted on different days to raise awareness about natural playgrounds through presentations. In the first workshop (W.1. Icebreaker game), a game was first played, suggested by the teachers, in which everyone threw a ball to get to know each other. This was followed by an initial presentation aimed at raising awareness about architecture and design. After showing the children visuals and short videos of the work of children participating in other participatory design workshops, they were asked whether they wanted to join this study to design their own kindergarten playground. In the second workshop (W.2. Explore natural playgrounds), following a story reading, an informal group discussion was held with the children around the question, “How can we play with a tree?” Afterwards, the children expressed their ideas in drawings. In the third workshop (W.3. Create natural playgrounds), during a visit to the Faculty of Architecture, the children examined models and, following a presentation on natural playgrounds, created individual models and expressed their envisioned playgrounds. In the fourth and final workshop of this phase (W.4. Design natural playgrounds), after a presentation on play possibilities with natural materials in playgrounds, the children individually designed playgrounds by creating models. During the awareness development phase, presentations were made to demonstrate the potential uses of natural playgrounds. However, to avoid being directive, photos from the kindergartens’ natural playgrounds were not shown. The children were asked to interpret their expectations for natural playgrounds in the context of their own kindergartens.

(3) Analysis of Space and Uses: A workshop (W.5. Explore your playground) that included a child-led tour and collective map-making allowed children to express their experiences and preferences regarding the current use of the playground in the kindergarten. The children drew the existing playgrounds on a blank site plan together with the researchers. This stage focused on exploring what children liked, disliked, and desired in relation to play.

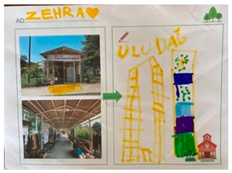

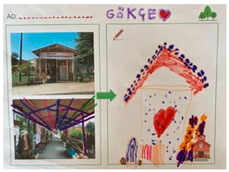

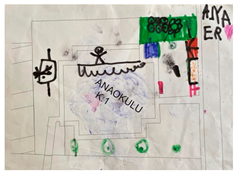

(4) Development of Design Ideas: Four workshops dedicated to the participatory design of natural playground in the kindergarten were held on different days. In the sixth workshop (W.6. How do we enter our natural playground?), the children expressed their suggestions for the entrance to the playgrounds in their kindergartens by drawing on worksheets that included photographs of the entrances. In the seventh workshop (W.7. Let’s design our natural playground), the children worked individually to illustrate their envisioned natural playgrounds on the kindergarten site plan. In the eighth workshop (W.8. Let’s imagine our natural playground), the children created a collage on a blank site plan to express their collective design ideas. In the ninth workshop (W.9. Let’s design our natural playground), the children, voluntarily divided into four groups, collaboratively developed a design on the kindergarten model based on the collage created in the previous workshop. In model-making, materials familiar to the 5-year-old children from kindergarten activities (play dough, cardboard, paper, scissors) were used, and, when necessary, a limited number of additional materials suitable for the workshop’s objectives were provided (sugar cubes, wooden sticks, plastic caps/boxes).

(5) Completion of Design and Feedback: Two workshops were conducted on different days to develop and present the digital model of the natural playground design. In the tenth workshop (W.10. Let’s evaluate our natural playground design together), the digital model, created by the doctoral students in the project team, was revised based on feedback from the children. In the eleventh and final workshop (W.11. What have we done so far?), the revised playground designs were presented again to the children for evaluation. The purpose of the three-dimensional digital model was to show the children their designs through a different architectural representation technique, help them perceive that their ideas were feasible, and allow them to critique the final design in terms of their own expectations. For this reason, the model was used as a design tool developed rapidly for iterative feedback. Additionally, interviews were conducted with children and teachers to gather feedback about the process. With their approval, the participatory design process and the natural playground project were completed. Since the children participated in the participatory design process, they were congratulated and given certificates of appreciation prepared in their names.

The activities in the workshops were designed through the collaborative efforts of two kindergarten teachers, one specialist from the Bursa Provincial Directorate of National Education, and the project team, with a focus on aligning them with the learning outcomes of early childhood education in Türkiye. A 5-week program was created and integrated into the kindergarten’s daily educational activities, which consisted of 1 to 1.5 h sessions held twice a week. These activities took place in both the classroom and the playground with the five-year-old group during May and June in the kindergarten. The stages and context of the participatory design model are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A Participatory Design Model for Children to Create Natural Playgrounds in Kindergartens: Stages, Workshops, and Outputs [36].

In this study, a combination of art-based (drawing, collage, three-dimensional modeling) and knowledge-based methods (interviews, group discussions, child-led tours, learning trips) were employed to engage five-year-old children in the design process [72]. Drawing and collage were chosen as they allow children to express themselves both individually and in groups. Model making was incorporated to enhance spatial perception and help children visualize their designs [59]. Individual interviews enabled children to elaborate on their ideas while group interviews were conducted to introduce topics like the importance of the natural playgrounds [24]. A child-led tour gave children the opportunity to express their views on the playground either verbally or non-verbally [73]. During the tour, children were encouraged to create maps representing their use of the space [18]. Additionally, a learning trip to the faculty of architecture allowed children to explore design concepts with expert guidance [72]. Digital models were developed by the architects in the research team to assess how well the children’s expectations were reflected in the design and to enable them to make decisions between alternatives [28]. The techniques chosen were tailored to the goals of the workshops, focusing on the content of the children’s models, drawings, and collages, which were evaluated based on their explanations rather than the quality of the work.

3.5. Data Analysis

In this study, the reflexive thematic analysis approach was employed, highlighting the researcher’s active and interpretive role in constructing themes rather than merely identifying them within the data [74]. The data were analyzed following the six-phase thematic analysis process outlined by Braun and Clarke [75]. First, the children’s comments on ppt presentations, drawings, models, collages, and child-led tour discussions were transcribed from audio recordings. In the second phase, the entire dataset was analyzed through two rounds of coding, during which the interview transcripts were read twice by the researchers and coding was conducted based on handwritten notes. Prominent features were organized, initial codes were developed, and data for each code were collated; unrelated codes, particularly those not connected to natural play spaces, were excluded. To ensure the objectivity, reliability, and accuracy of the coding process while minimizing researcher bias, two researchers independently coded the same data and then collaboratively reviewed the codes. In the third phase, potential themes were identified from the codes, and data were categorized under these themes. The relationships between themes and coded extracts were verified. The researchers jointly examined the potential themes to evaluate their coherence and relevance. In the fifth phase, themes were named, their content clarified, and representative examples were chosen. In the sixth phase, direct quotations were used to ensure validity, and the themes were linked to the research questions and relevant literature. All data items were treated equally during coding, with extracts organized for each theme while maintaining a clear relationship between data and analysis, ensuring consistency. Consequently, children’s spatial expectations for their natural playground design were categorized based on codes derived from the play actions they wished to experience. The analysis identified natural and manufactured items (codes), desired experiences (themes), and the corresponding designed natural spaces and spatial elements required to support these experiences (categories).

4. Findings

4.1. Awareness Development

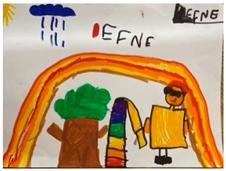

In the participatory design process, during the awareness development workshops, children reflected on the play affordances that natural playgrounds provide, what they wanted to do in these spaces, and the features they expected in a natural playground. In the first workshop, after the researchers explained the concepts of architecture and design and showed examples of models created by children in various design processes, the children expressed a desire to redesign the playground in their kindergarten. In the second workshop, following the reading of the story “The Last Tree in the City”, the children made comments demonstrating the importance they attach to nature. When asked how they could play with trees, plants, or leaves, they thought about their play in natural environments and provided a wide range of examples, such as hiding behind trees, climbing trees, playing in a treehouse, drawing on snow, leaves, or soil, planting flowers and saplings, making mud cakes and decorating them with flowers, creating potions from plants, making a fire from branches, and making music by hitting branches. They then expressed these imagined play affordances in detail through the drawings they created.

In the third workshop, following a visit to the architecture department to examine models and a presentation featuring images and videos of natural playgrounds, the children designed their own natural playgrounds by creating models. In their models, they did not include traditional playground equipment but instead created natural playgrounds incorporating elements such as water, soil, and hills. In this context, the awareness-building phase provided children with an opportunity to express their expectations for natural playgrounds through drawings and model-making, as well as to explore the potential of natural playgrounds, serving as a preparatory stage for the collaborative participatory design process (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of natural playground designs.

During the awareness development phase, a small number of children expressed expectations for playground elements inspired by their experiences in shopping malls and amusement parks (such as ice-skating rinks or trampolines). Additionally, children who had gone on picnics with their families talked about their play experiences in natural environments. This phase helped the children better understand the play potential of natural settings.

4.2. Analysis of Space and Uses, Development of Design Ideas

After moving into the design process of the natural playground in the kindergarten, during the fifth workshop (W.5. Explore your playground), the children analyzed the existing playground on a guided tour they led themselves. They showed the researchers in detail the features of the playground they liked and disliked. During the tour, they identified the playhouse (which contained a beehive), unused huts, and wire fences as areas they did not like. They also made various suggestions, such as reusing the idle huts for taking care of animals, creating a kitchen where they could make potions in the area where they observed flowers and insects, and having play areas with soil and mud. While the researchers took notes on these suggestions, the children tried drawing their playgrounds on a site plan showing the empty layout of the area. Through this activity, the children reflected in greater detail on the actions they wanted to carry out in the playground. In the sixth workshop (W.6. How do we enter our natural playground?), the children made suggestions indicating that the entrance to the natural playground should be consistent with the nature of the playground itself (e.g., jumping on stones, fences covered with plants, etc.). In the seventh workshop (W.7. Let’s design our natural playground), the children individually designed the natural playgrounds on a blank site plan of the kindergarten using their drawings (Table 2). The children incorporated natural elements such as water, trees, plants, surfaces, animals, stones, soil/sand, and loose parts in their individual designs of natural playground.

Table 2.

Examples of kindergarten’s entrance and natural playground designs.

In the eighth workshop (W.8. Let’s imagine our natural playground), the children created a collaborative collage of the first proposed natural playground for their kindergarten by cutting out visuals such as water, stones, and plants and combining them with their individual ideas. In the ninth workshop (W.9. Let’s design our natural playground), they formed four groups according to their preferences and expressed their natural playground designs in detail using modeling clay. In the collaborative design for the playground, the children related these natural elements to their spatial expectations and expressed their design proposals through a shared collage and model. The children were able to use play dough effectively as a means of expression in their models and demonstrated in detail the spaces and elements they wished to create in natural playgrounds, reflecting their forms and features (e.g., plants in the water channel, stones in the pond, vegetables in the vegetable garden, fruits on the trees).

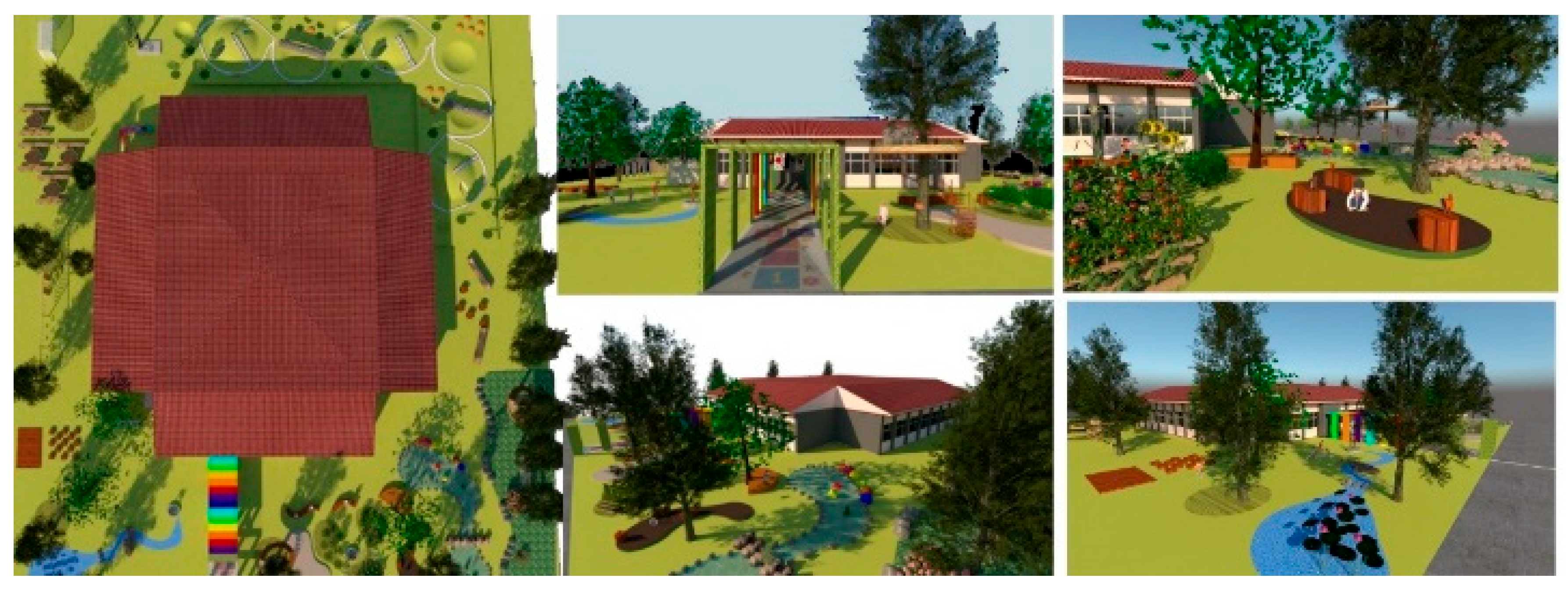

In this context, the children requested the following features: at the playground entrance (Figure 4, Area 1), they wanted a colorful canopy, spaces for displaying activities, seating elements, ground arrangements for play, and natural elements such as water, stones, flowers, and plants. In the front playground (Figure 4, Area 2), they proposed a natural pond with animals and water plants, vegetable and fruit flower gardens, a fountain, a vegetable/fruit, potion, and mud kitchen, a mud play area, an arts/painting area, a music wall, and logs. In the front playground (Figure 4, Area 3), they wanted a sand play area, fruit trees, a natural water channel, and a treehouse. In the side playgrounds (Figure 4, Area 4), they proposed green hills, flat grassy areas, a race course, and logs. In the back playground, they requested water features, green hills, tunnels, and a race course. In addition, the children suggested the inclusion of manufactured equipment such as swings, a climbing bar, a trampoline, a basketball hoop, and a soccer goal, as well as facilities like a stage for dancing/activities, picnic/crafting tables, cupboards, and kitchen counters (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

(a) Collage depicting the children’s design of the natural playground (W.8. Let’s imagine our natural playground); (b) Model depicting the children’s design of the natural playground (W.9. Let’s design our natural playground).

Figure 5.

Digital model depicting the children’s design of the natural playground (W.10. Let’s evaluate our natural playground design together).

In the tenth workshop (W.10. Let’s evaluate our natural playground design together), the children reviewed a digital model corresponding to their designs and provided critiques and suggestions. Although the level of realism in representing the character of the natural play environment designed by the children was limited in the model, the children were still able to perceive that their proposed natural playground could be realized. They carefully examined whether the natural spaces, spatial elements, and the intended uses they envisioned were present in the model. The three-dimensional model allowed them to better understand and evaluate the features of the natural playground they had designed. They checked whether the elements they had designed were included in the playground, whether the spaces were of the desired size, and whether safety was adequate in certain areas (e.g., the height of railings in the treehouse, the distances between picnic tables to avoid collisions, etc.). In addition to these adjustments, the digital model was adjusted, replacing the water feature in the back garden with an area for ball games as per the children’s suggestions. After the revisions were completed, in the eleventh workshop (W.11. What have we done so far?), the children confirmed that the visuals presented to them again were in line with their expectations. Converting the model created by the children into a digital model constituted the first step in developing the preliminary design.

In the participatory design process, the children’s expectations regarding the natural playground they designed were identified within the framework of the play actions (affordances) they wished to perform, as well as the corresponding codes, themes (desired experiences), and categories (designed natural spaces and spatial elements). The findings addressing the research questions of this study are presented in Table 3, revealing the children’s expectations in relation to eight identified themes.

Table 3.

Spatial expectations expressed by children through their natural playground design.

4.2.1. Exploring the Potential of Water Through Active, Passive, and Imaginative Experiences

Children offered the most water-related suggestions to create different types of play in natural playgrounds. They wanted to immerse themselves in water, float their toys, cross bridges and stones over the water, transport water to other areas, and combine water with other natural elements. They also wanted to incorporate living creatures (such as fish, frogs, and plants) and stones for jumping in the pools.

D.4: “There is a stony water. I would like to get wet there. There is a lake with stones in it. We jump over it.

A.2: “There is a lake in the backyard. Frogs and fish are in the water, while herbs and roses are on the surface.”

N.: “There is a waterway leading to the pool. Surrounding it is a stone and sand pool. The stones are there for jumping.”

N. and A.1: “A lake was created in the south garden. Plants were added to the water. The stones along the creek allow us to dip our feet in the water and even swim.”

D.5: “I would like to float my toys in the water. I would like to get into the water.”

The children also expressed to benefit from water in their playground, such as using it for activities like watering plants. They aimed to naturalize the pond and water channel with stones and aquatic plants, observe living creatures, and create both active and imaginative play experiences.

Z.1: “We can take water from the pool to water the trees and flowers.”

A.1: “I use the water in the garden for plants and experiments.”

With these expectations, the children designed water elements for different purposes: a fountain for watering and use in the play kitchen, a water channel for floating toys and entering the water, and a natural pond for observing living creatures and engaging in imaginative play.

4.2.2. Learning and Having Fun with Trees

Children incorporated active actions such as hiding, swinging, playing ball, climbing, and running around trees into their play. They also suggested activities like planting and nurturing saplings, picking fruits from trees, reaching honeycombs, and using branches to start a fire to cook something. These suggestions reflect children’s desire to engage in both active play with trees and to interact with nature by taking responsibility, observing seasonal cycles, and learning from them.

G.: “There is a treehouse. I can play in the treehouse whenever I want. I also play in the garden. I climb the tree with steps. There is a swing on the tree.”

D.1: “I play ball with my friend here. We tie a rope to the tree and play volleyball with other balls.”

O.: “I am climbing the apple tree. I pick the apples and give them to my dad.”

In this context, the children proposed new fruit trees, treehouses, hammocks hanging from trees, and a fire pit in the garden.

4.2.3. Exploring the Life Cycle with Plants, Creativity, and Developing Aesthetic Sensibilities

Children wanted to plant seeds and grow plants, eat the vegetables and fruits they cultivated, observe flowers, and use them in their imaginative play such as making potions or cakes. They also expressed a desire to beautify their surroundings with flowers.

Z.2: “There is a potion area where we make potions. There is a place to grow fruits and vegetables.”

Z.1: “There is a seed area. There is a potion-making area.”

K.1: “I would be very happy if the entrance gate were colorful and there were flowers and fences at the entrance.”

B.: “I made a kitchen next to the vegetable garden.”

It can be seen that children viewed plants as elements for learning about the natural life cycle, nourishment, and also as tools for imaginative play. Flowers were seen as elements that could enhance the aesthetic quality of the environment, appealing to their visual and olfactory senses. In this context, children designed vegetable, fruit, and flower gardens, as well as a garden kitchen to support these areas.

4.2.4. Incorporating Topography into Active and Passive Experiences

Children expressed a desire to use topography for actions such as sliding, running, climbing, rolling, resting, lying down, having picnics, eating, and playing ball, as well as for events like shows and celebrations.

Z.2: “There are hills I can jump on. I made green hills and tunnels.”

A.3: “I made an obstacle course. I slide down the grassy hill and can also pass underneath it.”

B.: “I made tunnels between the sand hills in the backyard and soil tunnels.”

D.4: “There is grass for rolling.”

The children discovered that the surface movements and characteristics of the topography could create play potential. They wanted to use topography for both active and passive actions by creating flat grassy areas and sloped surfaces. They suggested various types of hills (grass/sand/soil) and tunnels to crawl through in the garden, designing them into a connected course for racing games.

4.2.5. Communicating with Animals

Children expressed a desire to have various animals in the garden, such as fish, frogs, insects, butterflies, cats, and rabbits, so they could feed, observe, and incorporate them into their play.

G.: “There are rabbits in the garden, and we can feed them.”

Z.2: “There is an area with animals like rabbits and cats.”

It was evident that children imagined the natural playground as an environment where they could interact with animals and wanted to become part of the natural life cycle of living creatures. In this context, they proposed natural ponds, flower gardens, and animal pens where these creatures could live.

4.2.6. Experiencing Movement and Stillness with Stones

Children used stones in the playground for actions such as jumping, climbing, balancing, hiding inside caves made of stones, and resting.

D.4: “There is water and stones. I can jump over the stones.”

G.: “There is a cave, and we can rest there.”

L.: “I would like to jump over colorful stones from the entrance path.”

O.: “I would like a stone castle for children to play with in the garden.”

In this context, it was observed that children considered stones as materials that could respond to both their active and passive play, incorporating them into their imaginative play. Consequently, they proposed creating bridges, boundary elements, seating areas, caves, and castles from stones.

4.2.7. Developing Hands-On Creation Practices with Soil/Sand

Children expressed a desire to create various shapes with soil, sand, and water, dig holes, and build mounds.

Ç.: “There is a place to play with mud.”

D.2: “I made a sand and mud course in the back and side gardens.”

M.2: “I play in the mud in the water, and my friend plays with sand.”

D.5: “There is a yellow sand pool next to the bridge and the stream.”

It was observed that children viewed sand and soil as materials that, when combined with water, could facilitate open-ended play. They designed a soil play area where they could play with mud like dough, make food and various objects, and also created a mud kitchen. Additionally, they suggested a sand play area where they could engage in construction activities.

4.2.8. Experiencing Construction/Creation Practices with Loose Parts

In addition to natural elements, children wanted to play with loose parts like wooden blocks and sticks, stacking, arranging them side by side, and moving them around. With loose parts they aimed to build various play spaces in the playground. Additionally, children also wanted small loose parts for crafting.

A.1: “There is a maze. I walk through the maze, then jump and go down the stairs at the end. Then I jump again, go through the sticks, and reach the house from the maze.”

A.2: “I built a house with a garden in nature. I made fences around it.”

Children designed special play spaces, such as houses, castles, and stages, using loose parts in the playground. They also created spaces for both imaginative and active play, such as mazes and obstacle courses.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

5.1. Natural Playgrounds for Early Childhood and Education

This study shows that preschool children designing a natural playground for their own kindergarten can be an important process for improving the educational environment and fostering children’s awareness of environmental issues. Deng et al. [76] note that interaction with natural elements should be supported in early childhood education settings in order to promote sustainable environmental behaviors. Nordén and Avery [64] emphasize that preschool children’s participation in the design of outdoor spaces can form the basis for attitudes toward sustainability and responsible behavior later in life. Cañón-Vargas et al. [67] demonstrate that school gardens—defined as tools for experiential learning and understanding the human–nature relationship—contribute to preschool environmental awareness by providing opportunities to grow plants and observe living organisms. In this study, the children expressed their interest in the existing trees, natural planting areas, and small creatures such as insects and butterflies living in their kindergarten environment, and stated that they wished to protect these areas. In their design proposals, they developed ideas that would support the use of these areas to strengthen their interaction with the natural environment.

5.2. Experiences and Spatial Expectations of Preschool Children in Natural Playgrounds

It has been observed that children’s expectations of natural playground, along with the related play actions, align with findings from previous participatory studies and other research based on observations of children’s play. The themes identified regarding the expected opportunities in natural playgrounds are consistent with the theories of loose parts [49] and affordances [50], as well as with the functional taxonomy of children’s outdoor environments [51]. These themes also align with the findings of studies exploring children’s preferences for outdoor play environments. The landform, vegetation/trees, natural materials, moving/loose parts, sand and stone, water, insects, and small animal habitats that offer play actions (affordances) were identified by children in this study as components of a natural playground. Children recommended natural spaces, elements and manufactured items, including streams, fountains, edible landscape materials, nature-themed art, hiding places, tunnels, fallen trees, digging pits, storage space for equipment, etc. [8,9,10,14,28,62,63,65,70,77]. Dankiw et al. [48] state that structured (designed and safe) and unstructured (natural and spontaneous) play in natural playground design offer different opportunities and risks, and that creating hybrid spaces (incorporating both natural materials and some built elements) is important. In this study, the diversity of the children’s proposals was found to be consistent with this definition. As noted by Zamani [54], a balanced integration of natural elements with manufactured play features also emerged in the children’s expectations.

In this project, the children expressed their imagined experiences in detail, developed their own play scenarios, and designed natural spaces and spatial elements suitable for their intended play activities. The children primarily designed spaces in the natural playground that were water-related. They reorganized the topography of the playground, creating hills and pits at different heights and slopes, alongside flat areas and paths. They also proposed areas where they could interact with living creatures such as trees, plants, and animals. In addition, they incorporated both natural and manufactured loose parts into the natural playground. It was observed that 5-year-old children were able to design spaces and spatial elements suitable for the play actions they wished to engage in within a natural playground. They were able to design a natural playground where they could diversify their physical activities in their own kindergarten [7,15], find rich opportunities for exploration and learning through interaction with nature and living creatures [4,16], experience risky play [41,42], use their creativity by manipulating natural materials [11,16,47], construct spaces with natural materials [46], and create various play scenarios by engaging with nature [3].

Children paid attention to several design criteria during the natural playground design process. They were mindful of creating spaces that were appropriate to their scale, interconnected, and safe, ensuring accessibility between areas, supporting multi-purpose use, giving the environment a natural identity, providing climatic comfort, and establishing a connection with the context. Herrington and Lesmeister [78] defined the physical factors contributing to early childhood development and quality play for ECEEs as the “Seven Cs.” The aspects that children valued in the design of natural playgrounds in their kindergartens are consistent with the criteria emphasized in the literature for designing such spaces. In their designs, the children attempted to create the character of the natural playground (Character). In their drawings and models, they expressed the playground spaces using organic forms inspired by nature (e.g., the shapes of the pond and canal). They positioned the play areas in different sections by considering the context, offering suggestions such as placing kitchens under trees to provide shade (Context). They designed the sections of the natural playground by taking into account the functional relationships between them and the continuity of movement (Connectivity). For example, they positioned the mud kitchen, vegetable garden, and fruit trees around the pond and canal. Taking into account the different experiences offered by the natural playground, the children created areas suitable for both individual use and for multiple children at the same time (Change, Chance). Additionally, they organized the spaces in a way that was defined and easily perceivable for themselves (Clarity). They ensured that the spaces were appropriate for their size and actions (e.g., the dimensions of the mud and potion kitchens). They also related the capacity of the space to its size (e.g., water surfaces, which they intended to use the most, occupied the largest areas in the design). The children also included areas and elements in their designs to meet the needs for risky play and challenge (Challenge). Similar to Kamal’s [79] study, the children in this study considered safety issues in the playground (e.g., falling from a treehouse, bumping into picnic tables while running). At the same time, in line with Hinchion et al. [42], who noted that risky play can be perceived as both frightening and enjoyable, providing children with a sense of control, choice, decision-making, and achievement, they wanted to engage in exciting, risk-taking experiences such as jumping or rolling from hills, entering water, or making fires. Considering these evaluations of 5-year-old children during the design process of natural playgrounds, it can be inferred that involving children in the design process could lead to effective improvements in developing high play-value areas in kindergartens.

5.3. Participatory Design Process for Natural Playgrounds

In this research, a participatory design process was employed to facilitate the collaborative design of natural playgrounds in kindergarten with the involvement of five-year-old children. The overarching goal throughout the process was to position children as active designers and decision-makers in the project. They were encouraged to freely articulate their visions, thoughts, and recommendations regarding their playgrounds, translating their expressions into tangible design products. In the context of this study, it was observed that five-year-old children were able to actively participate in the design process with motivation and by using their creativity. As a result, it was observed that five-year-old children were able to design the natural playground in their kindergarten by working together, using representations of design, and relating to the context. In the participatory design process, the children collaboratively completed their envisioned natural playground design. From this perspective, the participatory design process corresponds to the level on Hart’s [21] ladder of participation where adults initiate the process but children generate their own decisions. Within a design process in which adults provided only limited input, the 5-year-old children were able to make collective decisions that reflected their expectations for the natural playground. At the same time, Hart [80] notes that not every child may participate at the same level on each step of the ladder. In this study, the researchers took into account situations in the workshops where some children were more hesitant than others or where children became bored or challenged by certain activities. Necessary supports were provided to address these issues, and, unlike the initial plan, small revisions were made to the program according to the children’s interests within the participatory design process. For example, presentation times were shortened, workshops related to the previous activity were conducted twice or three times in the same week, and the design of the entrance gate and pedestrian path was integrated into the program to enable a holistic design of the kindergarten playground. However, it was surprising that some children showed a remarkably high level of interest in designing, generated a large number of suggestions for the natural playground, and were able to express these ideas in detail through drawings and model-making.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that children can articulate their expectations for natural playgrounds in kindergartens through participatory design processes and can present design proposals accordingly. The study found that children in this age group could propose realistic and practical solutions to design natural playgrounds. Although the project has not yet been implemented due to the ongoing search for financial resources, which is a limitation, the inclusion of children in the implementation phase is also important. Therefore, it is considered that the implementation phase of the participatory design model could be further improved. Extending the current workshop program over an entire academic year by integrating both the design and implementation stages, and determining at which phases of implementation children can participate and what types of activities they can be involved in, may be beneficial. In this way, children can maintain an active role throughout the entire participatory design process, allowing the outcomes to be presented in a more concrete and tangible manner. Furthermore, the findings of the study are limited to a participatory design process conducted in a single kindergarten with children enrolled in the Harezmi Education Model. In future research, involving children from different kindergartens and various educational models could enhance the generalizability and scope of the findings. In conclusion, this study suggests that participatory design initiatives should be conducted to enhance the quality of kindergarten spaces and emphasizes the importance of increasing efforts to involve children in such processes. By applying the participatory design model for natural playgrounds in different kindergartens, it may be possible to develop quality playgrounds that are sensitive to the context and the needs of the children.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.E.Ş. and S.P.; methodology, B.E.Ş. and S.P.; validation, B.E.Ş. and S.P.; formal analysis, B.E.Ş. and S.P.; investigation, B.E.Ş., S.P. and A.B.Z.; resources, B.E.Ş., S.P. and A.B.Z.; data curation, B.E.Ş., S.P. and A.B.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, B.E.Ş., S.P., A.B.Z. and H.A.; writing—review and editing, B.E.Ş. and S.P.; visualization, A.B.Z. and H.A.; supervision, B.E.Ş. and S.P.; project administration, B.E.Ş. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Bursa Provincial Directorate of National Education Research Evaluation Committee (ethical approval number: E-86896125-605.01-76914432, approved on 25 May 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on the scientific research project entitled “A Participatory Design Model for Children to Create Natural Playgrounds in Kindergartens.” The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Bursa Provincial Directorate of National Education and Bursa Uludağ University for their institutional collaboration. They also thank the director and teachers of the Bursa Uludağ University Kindergarten, as well as the children and PhD students who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Richard, B.; Turner, J.; Stone, M.R.; McIsaac, J.-L.D. How an early learning and child care program embraced outdoor play: A case study. J. Child. Educ. Soc. 2023, 4, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpogianni, D.E. Why are the children not outdoors? Factors supporting and hindering outdoor play in Greek public day-care centres. Int. J. Play 2019, 8, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarth, H. ‘I like to dance with the flowers!’: Exploring the possibilities for biodiverse futures in an urban forest school. Child. Soc. 2024; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernan, M.; Devine, D. Being Confined within? Constructions of the Good Childhood and Outdoor Play in Early Childhood Education and Care Settings in Ireland. Child. Soc. 2010, 24, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerstrup, I.; Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C. Affordances of outdoor settings for children in preschool: Revisiting Heft’s functional taxonomy. Landsc. Res. 2016, 42, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, S.; Studtmann, K. Landscape interventions: New directions for the design of children’s outdoor play environments. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1998, 42, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjørtoft, I. Landscape as playscape: The effects of natural environments on children’s play and motor development. Child. Youth Environ. 2004, 14, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucks, A.; Hughes, H. Creating a sensory garden for early years learners: Participatory designing for student wellbeing. In School Spaces for Student Well-Being and Learning: Insights from Research and Practice; Franz, J., Hughes, H., Willis, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Woolley, H.; Tang, Y.; Liu, H.; Luo, Y. Young children’s and adults’ perceptions of natural play spaces: A case study of Chengdu, southwestern China. Cities 2018, 72, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norðdahl, K.; Einarsdóttir, J. Children’s views and preferences regarding their outdoor environment. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2014, 15, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, L.; Cabezas-Benalcázar, C.; Morrissey, A.M.; Versace, V.L. Traditional vs. naturalised design: A comparison of affordances and physical activity in two preschool playscapes. Landsc. Res. 2018, 44, 1031–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, J.; van der Wilt, F.; van Santen, S.; van der Veen, C.; Hovinga, D. The importance of play in natural environments for children’s language development: An explorative study in early childhood education. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2022, 31, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviranta, L.; Lindfors, E.; Rönkkö, M.L.; Luukka, E. Outdoor learning in early childhood education: Exploring benefits and challenges. Educ. Res. 2023, 66, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merewether, J. Young children’s perspectives of outdoor learning spaces: What matters? Australas. J. Early Child. 2015, 40, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, K.; van Rhijn, T.; Harwood, D.; Haines, J.; Barton, K. Exploring early childhood educators’ perceptions of children’s learning and development on naturalized playgrounds. Early Child. Educ. J. 2023, 53, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlembach, S.; Kochanowski, L.; Brown, R.D.; Carr, V. Early childhood educators’ perceptions of play and inquiry on a nature playscape. Child. Youth Environ. 2018, 28, 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, M. Nurseries Design Guide; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A. Talking and listening to children. In Children’s Spaces; Dudek, M., Ed.; Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Muela, A.; Larrea, I.; Miranda, N.; Barandiaran, A. Improving the quality of preschool outdoor environments: Getting children involved. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 27, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakr, A.F.; El Sayad, Z.T.; Shokralla Thomas, S.M. Virtual reality as a tool for children’s participation in kindergarten design process. Alex. Eng. J. 2019, 58, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R. Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship; UNICEF International Child Development: Florence, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A. Transforming Children’s Spaces: Children’s and Adults’ Participation in Designing Learning Environments; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langston, A.; Abbott, L.; Lewis, V.; Kellet, M. Early childhood. In Doing Research with Children and Young People; Fraser, S., Lewis, V., Ding, S., Kellett, M., Robinson, C., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2004; pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts-Holmes, G. Doing Your Early Years Research Project: A Step-By-Step Guide; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brinck, J.; Leinonen, T.; Lipponen, L.; Kallio-Tavin, M. Zones of participation–a framework to analyse design roles in early childhood education and care (ECEC). CoDesign 2022, 18, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansdown, G. Can You Hear Me? The Right of Young Children to Participate in Decisions Affecting Them; Bernard van Leer Foundation: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2005; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Rocca, L.; Donadelli, G.; Ziliotto, S. Let’s plan the school garden: A participatory project on sustainability in a nursery school in Padua. Rev. Int. Geogr. Educ. Online 2012, 2, 219–243. [Google Scholar]

- Menconi, M.E.; Grohmann, D. Participatory retrofitting of school playgrounds: Collaboration between children and university students to develop a vision. Think. Ski. Creat. 2018, 29, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of National Education [Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı]. Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı Okul Öncesi Eğitimi Programı [Ministry of National Education Preschool Education Program]. 2013. Available online: https://mufredat.meb.gov.tr/Dosyalar/20195712275243-okuloncesi_egitimprogrami.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Güngör, S. Examining the gardens of preschool educational institutions in terms of landscape design and space usage: Example of Selçuklu District. J. Agric. Fac. Gaziosmanpaşa Univ. 2017, 34, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaçan, M.O.; Halmatov, M.; Olcay Kartaltepe, O. Examining the gardens of the preschool education institutions. J. Early Child. Stud. 2017, 1, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, Y.; Özer, Z. Outdoor play activities and outdoor environment of early childhood education in Turkey: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Early Child Dev. Care 2021, 192, 1752–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geney, F.; Özsoy, Z.; Bay, D.N. Outdoor properties of preschool education institutions: Sample of Eskisehir. J. Soc. Sci. Eskiseh. Osman. Univ. 2019, 20, 735–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyükçınar, A.; Özemir, F.P. A review study on co-research with children in preschool environments. In World Children Conference III (22–24 April 2022) Proceedings Book; Altınay, Z., Altınay, F., Eds.; IKSAD Global Publishing House: Antalya, Turkey, 2022; Volume II, pp. 900–910. [Google Scholar]

- Ergüneş Kütük, G. Children’s Participation and Biophilic Design in Preschool Learning Environments. Design Studies Master Program. Master’s Thesis, İzmir University of Economics, İzmir, Türkiye, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Şahin, B.E.; Polat, S. A participatory design model for children to create natural playgrounds in kindergartens. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2025, 1792, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, F. Okul Öncesi Eğitim Kurumlarında dış Mekân Tasarımında Çocukların Beklentilerinin Belirlenmesi. Ph.D. Thesis, Ankara University, Ankara, Türkiye, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Arabacı, N.; Çıtak, Ş. Okul öncesi dönemdeki çocukların “oyun” ve “açık alan (bahçe)” etkinlikleri ile ilgili görüşlerinin incelenmesi ve örnek bir bahçe düzenleme çalışması [Review of opinions regarding the “play” and “open spaces (gardens)” for pre-school children and a study on arranging a sample playground]. Akdeniz Eğitim Araştırmaları Derg. 2017, 11, 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. Key Data on Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe—2025; Eurydice Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- The Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation of 16 June 2022 on Learning for the Green Transition and Sustainable Development 2022/C 243/01 (Text with EEA Relevance). Official Journal of the European Union. 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32022H0627%2801%29 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Little, H.; Eager, D. Risk, challenge and safety: Implications for play quality and playground design. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 18, 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinchion, S.; McAuliffe, E.; Lynch, H. Fraught with frights or full of fun: Perspectives of risky play among six-to-eight-year-olds. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2021, 29, 696–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M.; Ishikawa, T.; Brunelle, S.; Herrington, S. Landscapes for play: Effects of an intervention to promote naturebased risky play in early childhood centres. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; He, M. Utilisation and design of kindergarten outdoor space and the outdoor activities: A case study of kindergartens in Bergen, Norway and Anji in China. Int. Perspect. Early Child. Educ. Dev. 2021, 34, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, K.; van Rhijn, T.; Breau, B.; Harwood, D.; Haines, J.; Coghill, M. A quasi-experimental investigation of young children’s activity levels and movements in equipment-based and naturalized outdoor play environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 97, 102364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zeng, W.; Kloos, H.; Brown, R.; Carr, V. Preschool engineering play on nature playscapes. Early Child. Educ. J. 2024, 53, 2207–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alme, H.; Reime, M.A. Nature kindergartens: A space for children’s participation. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2021, 24, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankiw, K.A.; Kumar, S.; Baldock, K.L.; Tsiros, M.D. Parent and early childhood educator perspectives of unstructured nature play for young children: A qualitative descriptive study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, S. How not to cheat children: The theory of loose parts. Landsc. Archit. 1971, 62, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Heft, H. Affordances of children’s environments: A functional approach to environmental description. Child. Environ. Q. 1988, 5, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen, A.; Skaug, H.N.; Synnes, K. Children’s favorite places on the kindergarten playground—According to the staff. J. Eur. Teach. Educ. Netw. 2019, 14, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cetken-Aktas, S.; Sevimli-Celik, S. Play preferences of preschoolers according to the design of outdoor play areas. Early Child. Educ. J. 2023, 51, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, Z. Young children’s preferences: What stimulates children’s cognitive play in outdoor preschools? J. Early Child. Res. 2017, 15, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyment, J.; O’Connell, T.S. The impact of playground design on play choices and behaviors of pre-school children. Child. Geogr. 2013, 11, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, S.E.; Kemp, S.P. Integrating social science and design inquiry through interdisciplinary design charrettes: An approach to participatory community problem-solving. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2006, 38, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkola, T.M.; Kangas, J.; Reunamo, J. Children’s creative participation as a precursor of 21st-century skills in Finnish early childhood education and care context. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2024, 111, 102437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevón, E.; Mustola, M.; Siippainen, A.; Vlasov, J. Participatory research methods with young children: A systematic literature review. Educ. Rev. 2023, 77, 1000–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iltus, S.; Hart, R.A. Participatory planning and design of recreational spaces with children. Archit. Et Comport. 1994, 10, 361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Sahimi, N.N. Preschool children preferences on their school environment. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 42, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Salı, G.; Akyol, A.K.; Baran, G. An analysis of pre-school children’s perception of schoolyard through their drawings. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 2105–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Haas, C.; Ashman, G. Kindergarten children’s introduction to sustainability through transformative, experiential nature play. Australas. J. Early Child. 2014, 39, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, K. What’s in a dream? Natural elements, risk and loose parts in children’s dream playspace drawings. Australas. J. Early Child. 2018, 43, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordén, B.; Avery, H. Redesign of an outdoor space in a Swedish preschool: Opportunities and constraints for sustainability education. Int. J. Early Child. 2020, 52, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakan, A.; Acer, D. Analysis of preschool children’s outdoor play behaviours. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cologon, K. “But Marley can’t play up here!” Children designing inclusive and sustainable playspaces through practitioner research. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañón-Vargas, A.M.; Melo-Mora, S.P.; Sosa, E. School gardens as a research setting for early childhood children to strengthen their environmental awareness and scientific skills. Discov. Educ. 2025, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansdown, G. Every Child’s Right to be Heard: A Resource Guide on the Committee on the Rights of Children General Comment No 12; Save the Children and UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lozanovska, M.; Xu, L. Children and university architecture students working together: A pedagogical model of children’s participation in architectural design. CoDesign 2012, 9, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudeau, M. ‘What is natural in natural playgrounds?’: Nature, sustainability and environmental education in Calgary’s natural playgrounds. Environ. Educ. Res. 2024, 31, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of National Education [Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı]. Harezmi Eğitim Modeli Çerçeve Metni [Framework Document of the Hârezmî Education Model]. 2023. Available online: https://ogm.meb.gov.tr/meb_iys_dosyalar/2024_04/02131433_harezmiegitimmodelicerceveprogram.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Derr, V.; Chawla, L.; Mintzer, M. Placemaking with Children and Youth; New Village Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Manassakis, E.S. Children’s participation in the organisation of a kindergarten classroom. J. Early Child. Res. 2020, 18, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport. Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Ismail, M.A.; Sulaiman, R. Exploring the impact of biophilic design interventions on children’s engagement with natural elements. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luken, E.; Carr, V.; Douglas Brown, R. Playscapes: Designs for play, exploration and science inquiry. Child. Youth Environ. 2011, 21, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, S.; Lesmeister, C. The design of landscapes at child-care centres: Seven Cs. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]