Convergence and Divergence: A Comparative Study of the Residential Cultures of Tujia and Miao Traditional Villages in Western Hunan, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

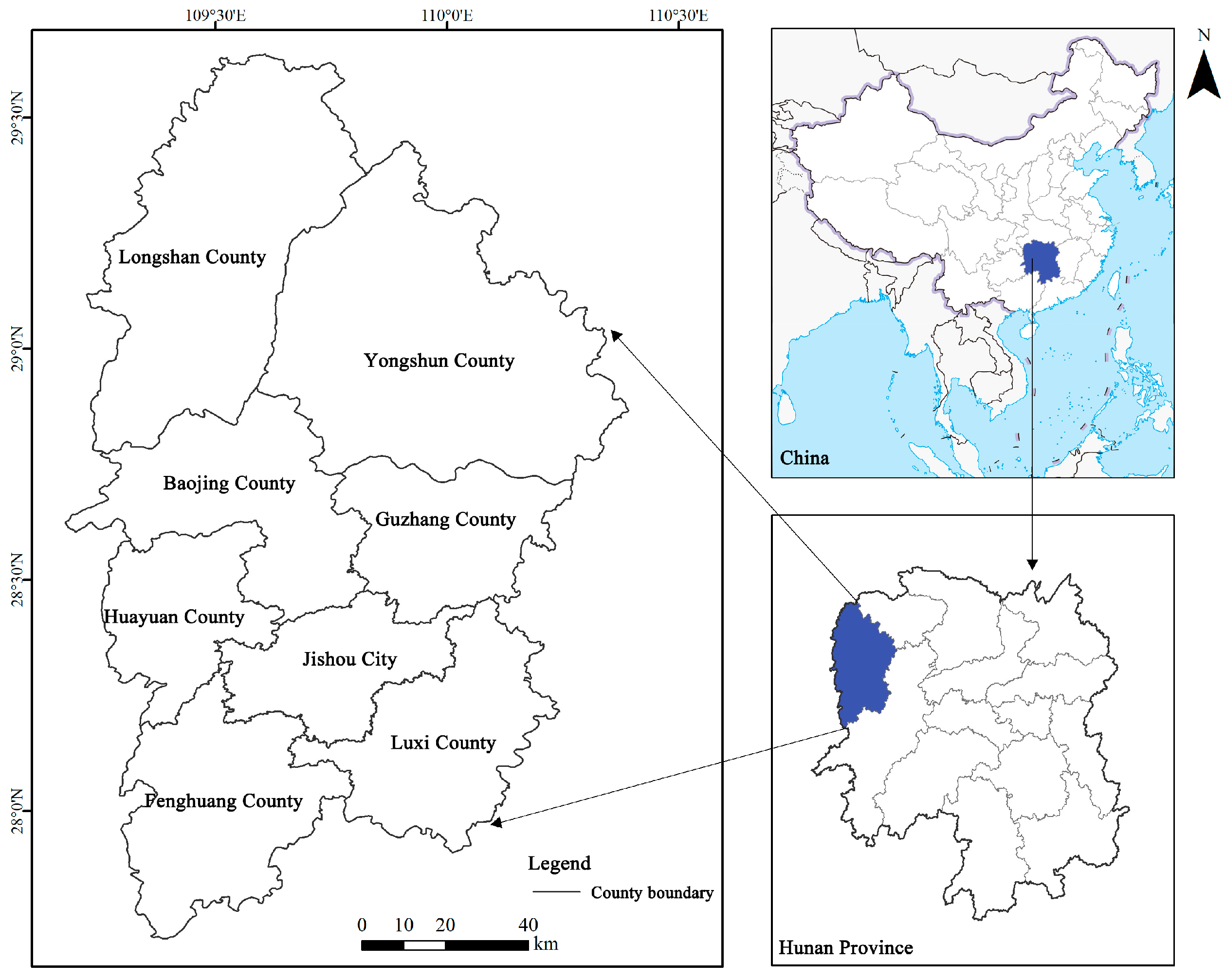

2.1. Study Areas

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. GIS Spatial Analysis

2.3.2. In-Depth Field Research

2.3.3. Cultural Interpretation

3. Results

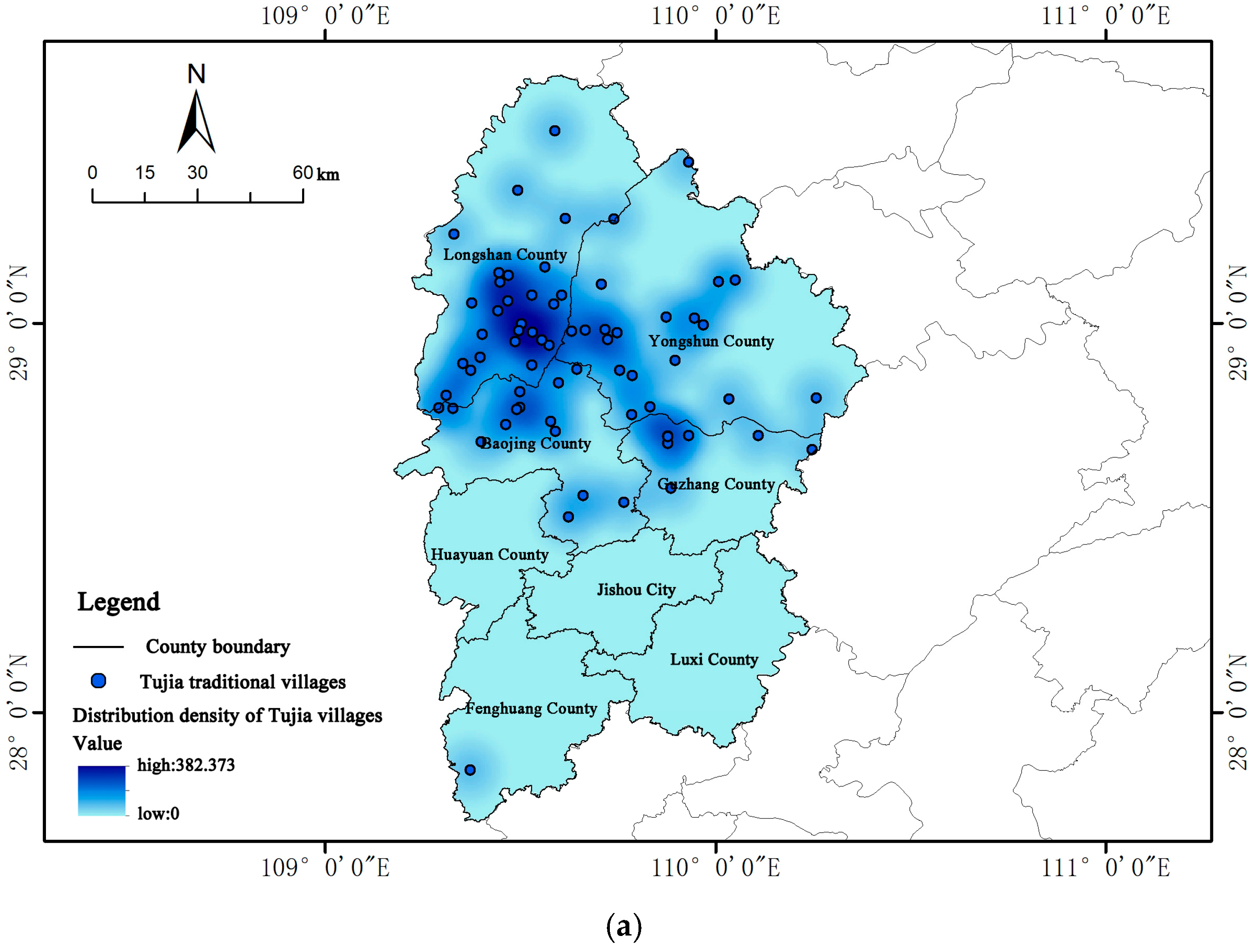

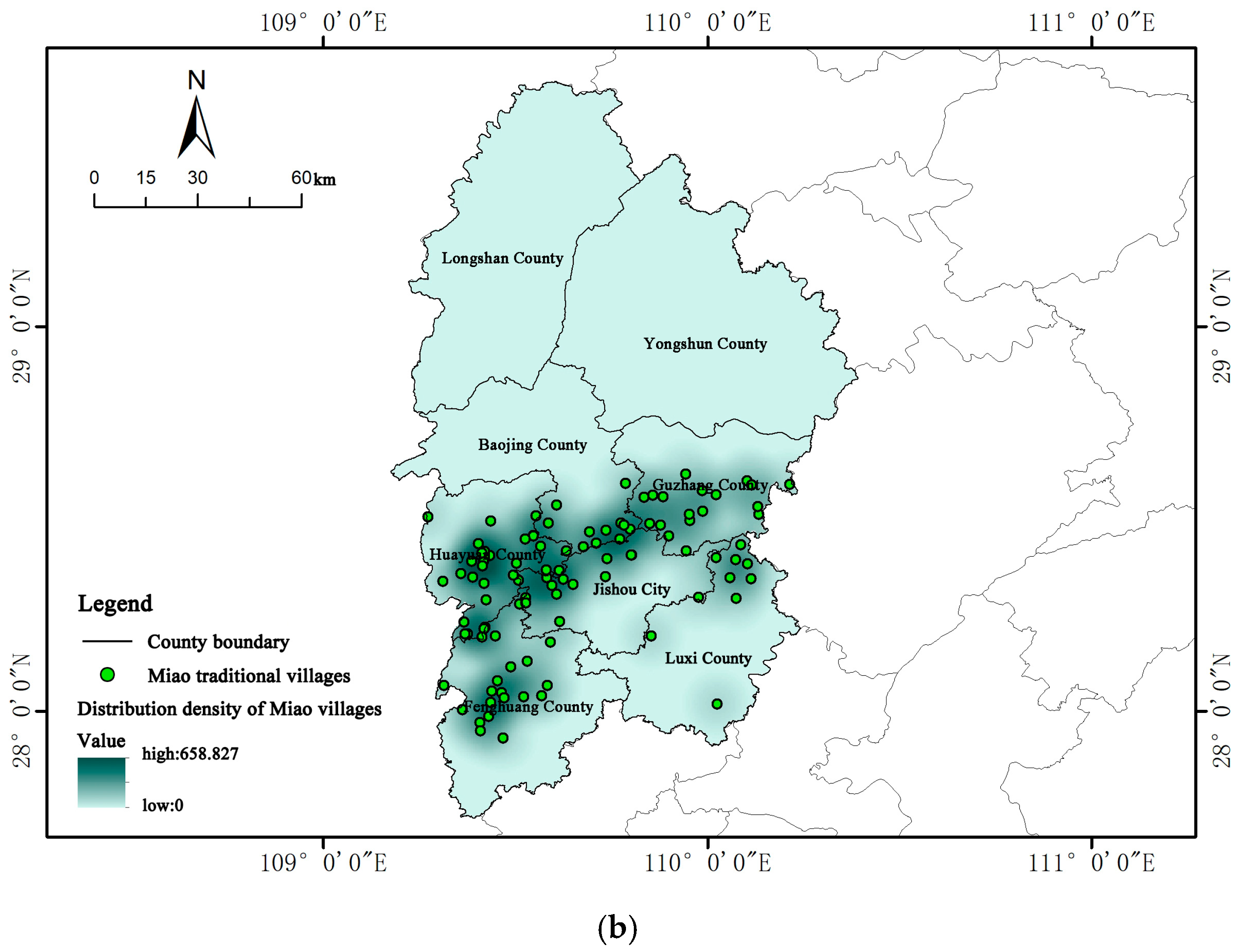

3.1. Historical Origins and Spatial Distribution of the Tujia and Miao Peoples

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Tujia and Miao Village Patterns

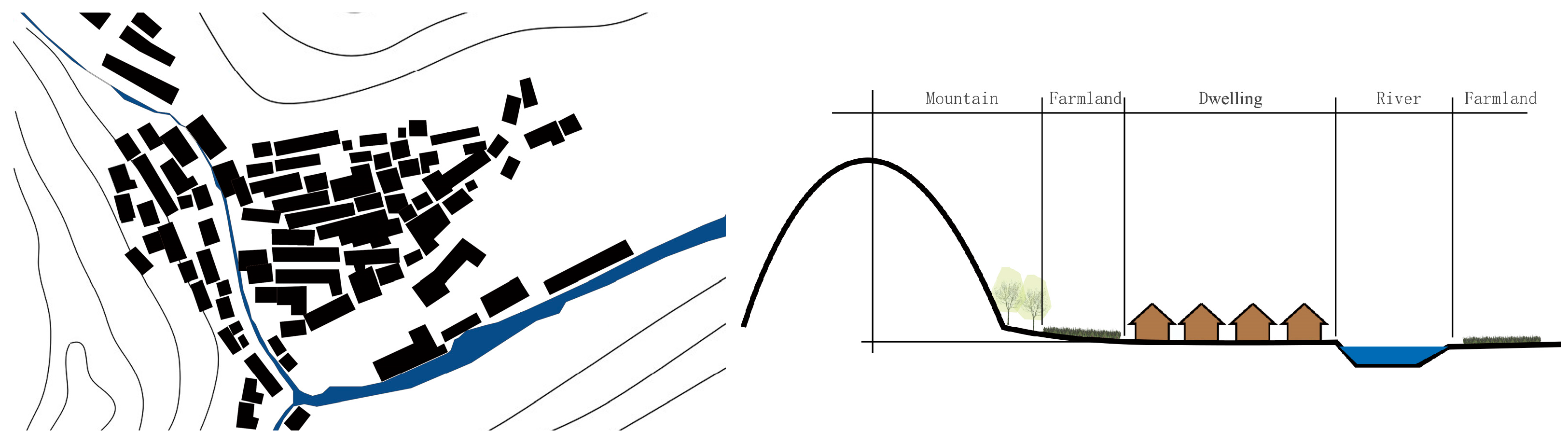

3.2.1. Village Site Selection

3.2.2. Village Layout

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Tujia and Miao Dwellings

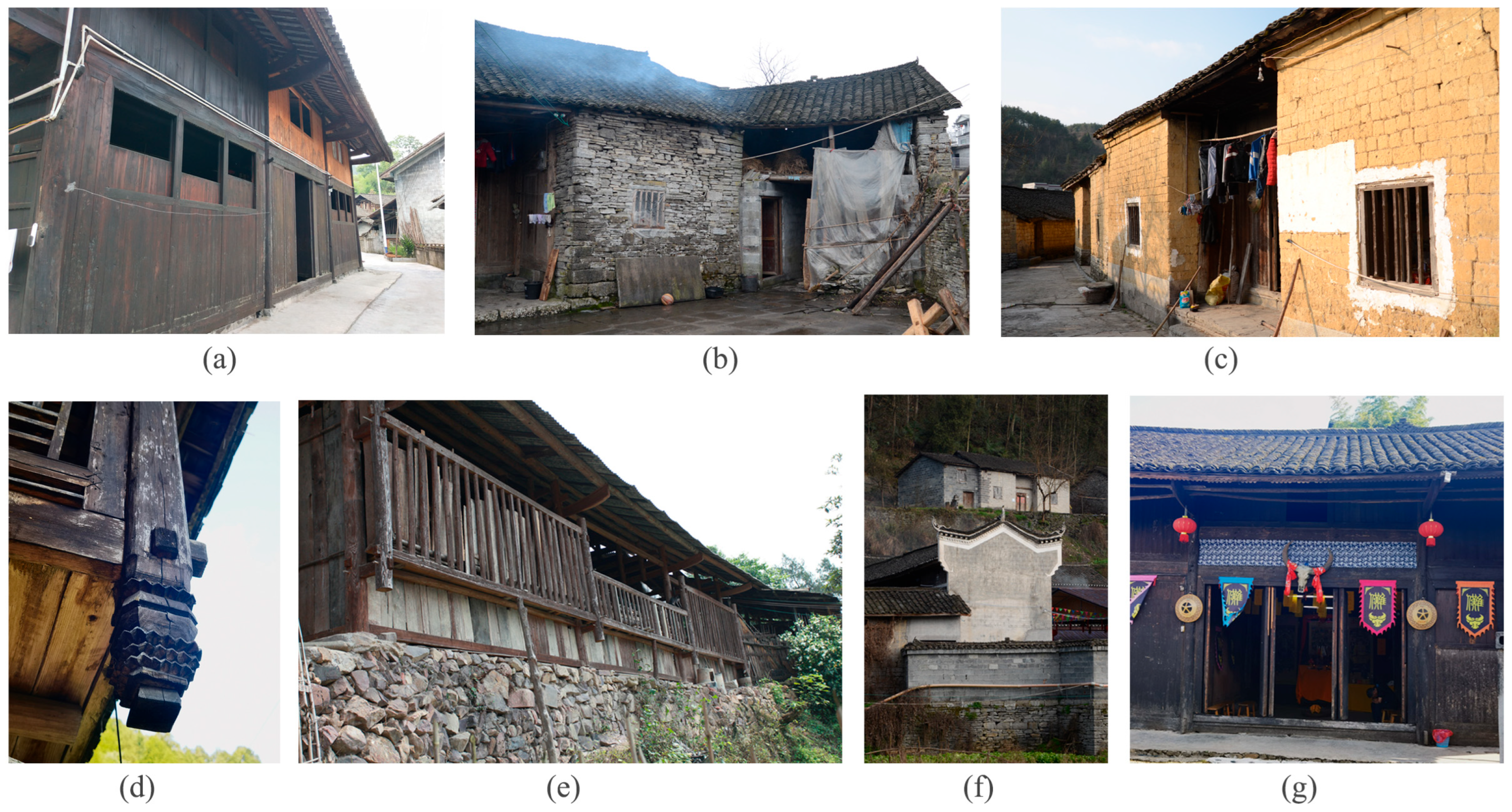

3.3.1. Construction Materials and Decoration

3.3.2. Planar Form and Spatial Configuration

3.4. Comparative Analysis of Folk Beliefs Between Tujia and Miao Ethnic Groups

4. Conclusions and Discussion

4.1. Conclusions

4.2. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, T.; Li, C.; Zhang, R.; Cong, Z.; Mao, Y. Spatial Heterogeneity and Influence Factors of Traditional Villages in the Wuling Mountain Area, Hunan Province, China Based on Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression. Buildings 2023, 13, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, G. A Digital Analysis of the “L”-Shaped Tujia Dwellings in Southeast Chongqing Based on Shape Grammar. Buildings 2025, 15, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Kang, T.; Fu, C.; Jiao, Y.; Hu, W. Spatiotemporal evolutionary characteristics of landscape carrying capacity in mountainous traditional villages during rural tourism development. Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xia, H.; Qian, Z.; Hu, C.; Liu, T. Wind Environment Adaptability and Parametric Simulation of Tujia Sanheyuan Courtyard Dwellings in Southeastern Chongqing, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; He, S.; Qiu, T.; He, C.; Xu, J.; Tang, W.; Li, Y. Predicting the Health Behavior of Older Adults in Western Hunan Villages Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Buildings 2024, 14, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Zhuo, X.; Xiao, D. Ethnic differentiation in the internal spatial configuration of vernacular dwellings in the multi-ethnic region in Xiangxi, China from the perspective of cultural diffusion. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.B.; Xiao, D.W.; Tao, J. Heritage and divergence: A comparative study of village dwelling cultures of the Yao ethnic group in southern Hunan and northern Guangdong. J. Hum. Settl. West China 2024, 39, 157–162. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Min, T.; Zhang, T. Cultural Resilience from Sacred to Secular: Ritual Spatial Construction and Changes to the Tujia Hand-Waving Sacrifice in the Wuling Corridor, China. Religions 2025, 16, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, T.; Zhang, T. Resilience Mechanisms in Local Residential Landscapes: Spatial Distribution Patterns and Driving Factors of Ganlan Architectural Heritage in the Wuling Corridor. Heritage 2025, 8, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigiotti, S.; Santarsiero, M.L.; Del Monaco, A.I.; Marucci, A. A Typological Analysis Method for Rural Dwellings: Architectural Features, Historical Transformations, and Landscape Integration: The Case of “Capo Due Rami”, Italy. Land 2025, 14, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Olmedo, P.; Núñez-González, M. Triana: Unveiling Urban Identity and Dwelling Architecture in the Modern Era. Heritage 2025, 8, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, D.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Cao, Y. Research on the form and formation mechanisms of Tujia traditional settlement in the Wuling Mountains, China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Xu, R.; Yi, X.; Qiu, H. Spatial distribution of toponyms and formation mechanism in traditional villages in Western Hunan, China. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, B.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J. Research on the Revitalization Path of Ethnic Villages Based on the Inheritance of Spatial Cultural Genes—Taking Tujia Village of Feng Xiang Xi in Guizhou Province as a Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Man, T.; He, L.; He, Y.; Qian, Y. Delineating Landscape Features Perception in Tourism-Based Traditional Villages: A Case Study of Xijiang Thousand Households Miao Village, Guizhou. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Xiao, D. Study on the Spatial Divergence of Hunan Minority Characteristic Villages. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 40, 114–119. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, M.M.; Getis, A. Handbook of Applied Spatial Analysis: Software Tools, Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J. Constructing a “Clustered—Boundary—Cellular” Model: Spatial Differentiation and Sustainable Governance of Traditional Villages in Multi-Ethnic China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.Q. Comprehensive review of studies on the origin of the Tujia ethnic group. Guizhou Ethn. Stud. 1999, 2, 83–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lei, X. Ethnic self-awareness and the construction of “ancestral identity”: The case of the “Ba people” in the Tujia ancestral identity. J. South-Cent. Minzu Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2010, 30, 28–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Du, J.; Ran, D.; Yi, C. Spatio-temporal distribution and evolution of the Tujia traditional settlements in China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.C. The migration process of the Miao people as reflected in oral classics. Guizhou Ethn. Stud. 2018, 39, 190–194. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Xu, W.; Xiao, Y.; Shi, J.; Hu, X.; Yan, B. Temporal and spatial patterns of traditional village distribution evolution in Xiangxi, China: Identifying multidimensional influential factors and conservation significance. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Xiao, D.; Li, J.; Xu, Z.; Tao, J. Research on Traditional Village Spatial Differentiation from the Perspective of Cultural Routes: A Case Study of 338 Villages in the Miao Frontier Corridor. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.H. Study on Spatial Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in Xiangxi Prefecture. Master’s Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.B. Living Analysis of Miao Architectural Culture in Guizhou; Guizhou People’s Publishing House: Guiyang, China, 2005. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.S.; Yuan, M.; Pang, H. Morphological characteristics and cultural connotations of Tujia Diaojiaolou in western Hubei. J. South-Cent. Minzu Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2018, 38, 59–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Wang, J.P.; Ren, Y.P. Comparative study of settlement and architectural space of Miao and Tujia stilted dwellings under Central Plains cultural influence. Urban. Archit. 2019, 16, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.Y. Study on the differences between Tujia and Miao folk houses in Xiangxi area. Design 2020, 33, 124–125. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. Vernacular Dwellings in Western Hunan; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2008. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. Comparative analysis of Tujia and Miao stilted dwellings in Chongqing and Sichuan. Sichuan Archit. Sci. Res. 2013, 2, 318–320. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gong, T.; An, X. A Study on the Techniques of Building Large-scale Wooden Works for the Tujia Nationality in the West of Hubei Province: Taking “YaoShiTou” as an Example. Decoration 2020, 5, 103–107. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Riccio, T. Zhuiniu Water Buffalo Ritual of the Miao: Cultural Narrative Performed. Religions 2022, 13, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, N. From Ancestors to “Gaxian”: The Occurrence of the Ritual of Tomb Sacrifice of the Miao Ethnic Group in Xiangxi: A Case Study of Jixin Miao Village in Fenghuang County, Western Hunan. J. Hunan Univ. Sci. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 25, 169–177. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Ye, J.C. On the Significance of the Study of Hall/Room Patterns in Dazhuangshi Biji. J. Archit. Hist. 2021, 2, 30–36. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Man, Y. Comparative Study of Residential Space of Miao and Tujia Ethnic Groups in Western Hunan. Master’s Thesis, Jilin Jianzhu University, Changchun, China, 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Long, B. Differences of stilted building from a typological perspective. Archit. J. 2011, S2, 142–147. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.L.; Li, X.F.; Tang, S.K. Types and evolution of hall-space layouts in traditional dwellings of western Hunan. Archit. J. 2022, 2, 82–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. On the “Multiple Children” Symbol of the Totem Worship of the Miao Nationality in Guizhou. Guizhou Ethn. Stud. 2019, 40, 65–69. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Bai, G.X. Ritual dance and body practice: Symbolic interpretation of Tujia’s waving ceremony. J. Ethnol. Stud. 2022, 43, 143–148. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.F.; Shan, W.B. Soul lineage, ancestral lineage and cultural lineage: Exploring how the Baishou tradition contributes to the shared spiritual home of the Chinese nation. J. Hubei Minzu Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2025, 43, 62–72. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.; Shu, Y. Tujia folk beliefs and their ethnic spirit. Guizhou Ethn. Stud. 2021, 42, 130–136. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Village Name | County | Longitude/ Latitude | Attribute | Formation Period | Ethnic | Area/km2 | Folk Culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lanhuadong | Yongshun | 110.0342/ 28.80708 | Administrative | Qing Dynasty | Tujia | 16.6 | Hand-Waving Dance, Tujia Brocade Patterns, DaLiuZi Playing, Crying-Wedding Songs |

| Daming | Yongshun | 110.0507/ 29.11616 | Natural | Ming Dynasty | Tujia | 1.58 | Hand-Waving Dance, DaLiuZi Playing |

| Xilong | Yongshun | 109.7166/ 28.98801 | Administrative | Qing Dynasty | Tujia | 20 | Hand-Waving Dance, DaLiuZi Playing |

| Laoche | Longshan | 109.5027/ 28.99814 | Administrative | Ming Dynasty | Tujia | 29.23 | Hand-Waving Dance, Tujia Brocade Patterns, Tima Songs, DaLiuZi Playing, MaoGuSi Dance |

| Longbi | Guzhang | 109.8489/ 28.48839 | Natural | Ming Dynasty | Miao | 12 | Miao Drums |

| Dongwei | Huayuan | 109.3960/ 28.25243 | Natural | Ming Dynasty | Miao | 6.88 | Miao Drums, Zhuiniu, Crying-Wedding Songs |

| Dongshao | Huayuan | 109.4352/ 28.27553 | Natural | Qing Dynasty | Miao | 2.3 | Zhuiniu, Crying-Wedding Songs |

| Mixi | Baojing | 109.8069/ 28.59480 | Administrative | Ming Dynasty | Tujia and Miao | 12.5 | Hand-Waving Dance, Tujia Brocade Patterns, DaLiuZi Playing, Crying-Wedding Songs |

| …… | …… | …… | …… | …… | …… | …… | …… |

| Mituo | Fenghuang | 109.4469/ 28.19519 | Natural | Ming Dynasty | Miao | 6.2 | Miao Embroidery, Crying-Wedding Songs |

| Name | Village | Gender | Age | Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ma | Dongxi Village, Guzhang County | Male | 40 | Cadre |

| Shi | Wengcao Village, Guzhang County | Male | 31 | Cadre |

| Long | Jiulong Village, Guzhang County | Male | 60 | Doctor |

| Zhang | Zimu Village, Guzhang County | Male | 74 | Craftsman |

| Xiang | Xilong Village, Yongshun County | Male | 49 | Resident |

| Wu | Gupo Village, Huayuan County | Male | 61 | Resident |

| Xiang | Mixi Village, Baojing County | Female | 36 | Resident |

| … | … | … | … | … |

| Wang | Liangdeng Village, Fenghuang County | Female | 37 | Resident |

| Distance to Nearest River | <100 m | 100–500 m | 500–1000 m | >1000 m |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Tujia villages | 14 | 21 | 9 | 25 |

| Number of Miao villages | 16 | 23 | 17 | 46 |

| Name | Photo | Layout View | Feature Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laosiyan Village, Guzhang County |  |  | Tujia village, faces north with its southern elevation higher than the northern. Surrounded by mountains on the east, west, and south, the Youshui River flows along its northern edge. Dwellings are scattered throughout the terrain. |

| Xina Village, Yongshun County |  |  | Tujia village, surrounded by mountains on three sides, with dwellings built along the slopes and nestled beside the river, creating a picturesque scene of staggered heights. |

| Lanhuadong Village, Yongshun County |  |  | Tujia village, surrounded by mountains, with steep slopes and towering peaks. Dwellings are built on the flat areas along the surrounding hillsides, forming a dispersed cluster layout. |

| Wengcao Village, Guzhang County |  |  | Miao village, encircled by mountains, nestled along both banks of a small stream, and situated on the gentle slopes of a basin. Dwellings are arranged along the foothills, with houses clustered closely together to form a labyrinthine network of alleys. |

| Dongxi Village, Guzhang County |  |  | Miao village, nestles among towering mountains, oriented north to south. Its dwellings are built in harmony with the terrain, forming a compact, terraced layout. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, G.; Zhang, M.; He, S. Convergence and Divergence: A Comparative Study of the Residential Cultures of Tujia and Miao Traditional Villages in Western Hunan, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 4539. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244539

Chen G, Zhang M, He S. Convergence and Divergence: A Comparative Study of the Residential Cultures of Tujia and Miao Traditional Villages in Western Hunan, China. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4539. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244539

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Gong, Mengmiao Zhang, and Shaoyao He. 2025. "Convergence and Divergence: A Comparative Study of the Residential Cultures of Tujia and Miao Traditional Villages in Western Hunan, China" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4539. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244539

APA StyleChen, G., Zhang, M., & He, S. (2025). Convergence and Divergence: A Comparative Study of the Residential Cultures of Tujia and Miao Traditional Villages in Western Hunan, China. Buildings, 15(24), 4539. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244539