Abstract

Effective training is essential for addressing the continuous requirement for enhancing productivity and safety in construction. Virtual reality (VR) has emerged as a powerful tool for simulating site environments with high fidelity. While previous studies have explored the potential of VR in construction training, there is potential to incorporate advanced construction theories, such as lean principles, which are critical for optimizing work processes and safety. Thus, this study aims to develop an integrated VR-lean training system that integrates lean principles into traditional VR training, focusing on improving productivity and ergonomic safety—two interrelated challenges in construction. This study developed a virtual training environment for scaffolding installation, employing value stream mapping—a key lean tool—to guide trainees in eliminating waste and streamlining workflows. A before-and-after experimental design was implemented, involving 64 participants randomly assigned to non-lean VR or integrated VR-lean training groups. Training performance was assessed using productivity and ergonomic safety indicators, while a post-training questionnaire evaluated training outcomes. The results demonstrated significant productivity improvements in integrated VR-lean training compared to non-lean VR training, including a 12.3% reduction in processing time, a 21.6% reduction in waste time, a 20.8% increase in productivity index, and an 18.4% decrease in number of errors. These gains were driven by identifying and eliminating waste categories, including rework, unnecessary traveling, communication delays, and idling. Additionally, reducing rework contributed to a 7.2% improvement in the safety risk index by minimizing hazardous postures. A post-training questionnaire revealed that training satisfaction was strongly influenced by platform reliability and stability, and user-friendly, easy-to-navigate interfaces, while training effects of the integrated training were enhanced by before-session on waste knowledge and after-training feedback on optimized workflows. This study provides valuable insights into the synergy of lean principles and VR-based training, demonstrating the significant impact of lean within VR scenarios on productivity and ergonomic safety. The study also provides practical recommendations for designing immersive training systems that optimize construction performance and safety outcomes.

1. Introduction

The construction industry exhibits relatively lower productivity compared to other industries like manufacturing [1]. According to the Centre for Economic Development Australia [2], the labour productivity in construction increased by only 17% over the past three decades, whereas broader market-sector industries saw a 64% increase. Similarly, ref. [3] reported that construction productivity consistently lags that of manufacturing and service industries, primarily due to fragmented adoption of automation technologies and the lack of standardized processes across the project lifecycle. Moreover, construction sites often present complex conditions, contributing to persistent safety concerns. In 2019, of 5333 private-sector work fatalities in the United States, 1061 (approximately one in five) occurred in construction [4]. Occupational injuries and accidents due to poor ergonomics are prevalent in the construction industry [5]. Such injuries often result from improper posture, repetitive strain, and poorly designed tools or workstations—issues that ergonomic safety research seeks to mitigate.

Training programs for construction workers are essential to mitigate challenges related to productivity and ergonomic safety. Recently, visualization technologies such as building information modelling (BIM), virtual reality (VR), and augmented reality (AR) have been widely adopted in construction training to improve learning outcomes [6,7,8]. These approaches facilitate easier dissemination and more effective absorption of knowledge and skills among construction workers. Numerous studies suggest that these technologies enhance training outcomes for productivity or construction safety [9,10]. For example, ref. [11] demonstrated that VR-based training improved productivity by 12% in scaffolding installation. Ref. [12] delivered safety training via a virtual platform for university students and found significant improvements in learning experience and motivation. Although VR training provides immersive, interactive simulations that replicate real-world construction environments, it is still challenging to identify and eliminate inefficient task sequences and avoid hazardous behaviors.

Lean is a management philosophy and methodology aimed at targeting inefficiencies and non-value-adding activities, with the potential to broaden process optimization and increase productivity. Integrating VR-based training with lean thinking provides a structured approach to enhancing both safety and efficiency by identifying workflow bottlenecks and standardizing safe, value-adding practices across training and execution phases [13,14]. For example, refs. [15,16] suggested that lean practices can positively influence occupational health and safety by reducing non-value-adding activities and mitigating associated risk factors [17]. Although lean principles have been proven to enhance productivity, their application in safety management remains fragmented and largely qualitative. Studies consistently demonstrated that safety and productivity are not mutually exclusive [17] but can improve synergistically through effective management practices. Nevertheless, in practice, the construction industry often reflects a misperception of trade-off between these goals [18,19].

This study considers scaffolding installation as a construction case. Scaffolding is one of the most prevalent temporary structures in construction projects, yet inefficiencies or delays in its installation can seriously affect project schedules as well as ergonomic safety. According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration [20], approximately 65% of construction workers have engaged in scaffolding-related activities. Because scaffolding installation requires strict time-sequencing, it is well-suited to the application of lean principles. Meanwhile, scaffolding activities have a significant impact on construction workers’ health and safety. Ref. [20] reported that about 9750 scaffolding-related accidents occur annually in the U.S. construction industry, highlighting the urgent need to improve efficiency and safety in scaffolding operations.

This study aims to develop an integrated VR-lean training system and examine its impacts on construction productivity and ergonomic safety. First, the proposed approach embedded lean principles into a VR-based training framework, concentrating on scaffolding installation. This approach incorporated realistic activities, such as task sequences, location-specific actions, and clear role definitions for each trainee. Next, 64 participants were recruited to attend presentation and practice sessions, and a trial run to ensure baseline knowledge of the VR platform and scaffolding installation. Then, all participants were randomly assigned to two groups, receiving either non-lean VR training or integrated VR-lean training. Task performance, including productivity and ergonomic safety indicators, was evaluated and compared between the two groups. In addition, training outcomes were assessed via a questionnaire survey. Finally, a post-training questionnaire was implemented to explore the factors influencing the effect of the integrated VR-lean training, offering insights for optimizing training design and implementation.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews literature on VR-based construction training for productivity and safety, and the impact of lean on productivity and safety. Section 3 details the research methodology, including the design, evaluation and comparison of non-lean VR and integrated-lean training. Section 4 presents the results, while Section 5 discusses key findings and provides recommendations for future research. Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. VR/AR in Construction Training

Traditional construction training methods rely on handouts and presentations and often provide identical content, scenarios, and difficulty levels to all trainees, irrespective of their skill levels [21]. Moreover, traditional approaches do not adequately represent the complex and dynamic situations that trainees may face in real-world projects [13]. In this context, onsite training considers real-world complexities but is time-consuming, costly, and will potentially expose trainees to hazards that have not been adequately introduced beforehand [6].

Recently, immersive and visualization technologies, such as VR, BIM, gaming technologies, and AR, have been predominantly applied in architectural visualization and construction training [7,22]. A typical virtual training system consists of hardware (e.g., cameras for vision, microphones for audio, and sensors for motion detection), software, and supporting algorithms, regardless of the technology used to create the virtual environment. Mature VR technologies, including Oculus Rift, Samsung VR, and ANTVR Kit, have been adopted to overcome the limitations of traditional handout- and slide-based methods. For example, some studies have developed fully immersive virtual environments to enhance training outcomes for high-risk tasks, such as crane operations [23,24] and scaffolding installation [11], while others have designed virtual components integrated with safety information accessible via smart devices [12]. In a review of VR applications for ergonomic safety analysis, ref. [25] found that most studies focused on the automotive industry, where VR is primarily applied to workstation ergonomics and process development. Extending such applications to construction is particularly valuable, as construction tasks involve unique challenges, such as assessing forces exerted by workers during scaffold assembly or identifying ergonomic risks from awkward postures and repetitive motions. VR-based training programs have shown promise in addressing these challenges by replicating real-world construction environments, allowing trainees to practice identifying and mitigating safety risks without exposure to actual hazards [26,27]. Furthermore, VR immersive experiences have been found to be user-friendly and to enhance participants’ confidence in construction tasks [28]. Compared with traditional video and slide-based training methods, VR-based training also improves skill acquisition, understanding, and memory retention [29].

While the benefits of VR/AR technologies are recognized, many researchers argue that integrating advanced production and management theories, methods and practices can further enhance VR training performance [6]. For instance, ref. [30] illustrated that construction activities performed with improper work or time sequences may pose workers to higher hazards. In such cases, trainees often require additional time to retrieve information and complete tasks in the correct order, which can lead to mental fatigue. Similarly, ref. [6] suggested VR-based training research should investigate work modes and theoretical frameworks that optimize work sequences and improve worker skills. Within this context, the lean concept, which emphasizes eliminating waste and streamlining workflows, offers valuable potential for advancing VR-related training by improving efficiency and reducing hazards in immersive learning scenarios.

2.2. Lean, Productivity, and Safety

Since the 1990s, lean construction has been recognized as a systematic approach to identifying and eliminating waste and has more recently gained increasing attention in areas such as sustainability, health, and safety within construction [31]. Waste is typically classified into eight categories: overproduction, defects, inventory, process, transportation, waiting, motion, and underutilized talent [32]. To overcome these types of waste, various lean tools have been developed, such as 5S (i.e., sort, simplify, sweep, standardize, and self-discipline), just-in-time (a method ensuring production matches demand in timing and quantity), poka-yoke (error-proofing mechanisms), and value stream mapping (visual workflow analysis and improvement) [33,34,35,36]. Practically, the primary benefits of lean are associated with productivity improvements [37]. Ref. [38] illustrated that lean practices can significantly improve workflow, scheduling, and quality.

Besides, adopting lean can also positively influence operational health and safety. For instance, ref. [39] identified strong synergies among lean, safety, and ergonomics during production. Likewise, ref. [16] evaluated the alignment between lean principles and worker safety behavior through content analysis and expert discussions and validated that lean practices such as the Last Planner System (LPS) can provide substantial safety benefits. Ref. [15], based on a survey of 67 U.S. builders, reported that lean implementation contributes to reducing accident rates in construction. Moreover, ref. [40] developed a conceptual model incorporating common lean tools—such as 5S, visual management, LPS, and just-in-time—and demonstrated that these practices play a significant role in improving construction health and safety. Their questionnaire results further revealed positive relationships between the use of lean tools and safety planning, compliance, participation, and inspection. Ref. [41] assessed the impact of lean practices on safety risk management in off-site construction and provided a generic checklist of lean management practices to improve the safety success rate of off-site construction projects. Otherwise, ref. [42] designed a safety planning and control process based on lean construction technologies, representing improved efficiency of safety management. Ref. [43] developed an accident-enabled training scenario and a lean-oriented training protocol for crane operator training under productivity pressures, and their findings demonstrated that integrating lean thinking improved safety performance in virtual environments.

However, there are still several limitations. First, most existing studies investigating relationships between lean and occupational health and safety rely on subjective and qualitative methods, such as surveys, questionnaires, and discussions with onsite workers and experts. Only a few have employed quantitative analysis to assess the extent of safety improvements achieved through lean integration. Second, although VR and lean principles have each been shown to affect productivity and safety training positively, the impact of integrating lean within a virtual environment on training performance remains underexplored. Accordingly, this study investigates the training outcomes of combining lean with traditional VR-based training. Third, there is an insufficient understanding of the key factors that influence the effect of training systems. This limitation arises because most prior studies have relied on simple satisfaction surveys, thereby overlooking deeper insights into the drivers of meaningful training outcomes [44].

3. Research Method

This study developed a VR-lean training platform for scaffolding installation to quantify the impact of VR-based lean principles on construction training. 64 civil engineering students were randomly assigned to either a non-lean VR training group or an integrated VR-lean training group. After training, work performance was evaluated using productivity and ergonomic safety indicators, as well as questionnaires assessing training outcomes. Meanwhile factors influencing the effect of the integrated system were identified using Entropy weighting and generalized additive models.

3.1. Training Platform

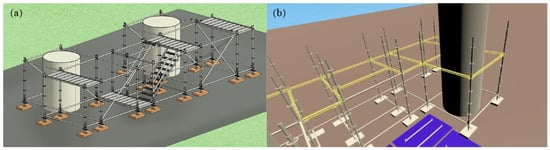

The training platform was developed based on a real construction project. This project involved the repair of a pre-heater tower, where scaffolding was erected onsite to support construction activities. Virtual components were created in Revit (version 2018.3) and exported into the VR environment, while Unity3D (version 2018.3) was used to develop the interactive virtual environment with C# as the programming language. The hardware setup included an HTC Vive headset (90 Hz refresh rate, resolution), an HTC Vive wireless controller with a trackpad, grip buttons, and dual-stage trigger, as well as a Dell S2340L 23-inch monitor. In the virtual platform, scaffolding components were modeled to match real-world dimensions and placements, enabling trainees to practice realistic construction procedures. To simplify the real-life scenario for VR simulation, secondary elements such as toe boards, mesh guards, and minor fixings were excluded from the initial version to maintain focus on core assembly skills and structural stability. The VR environment does not include audio, so all guidance and feedback are delivered visually. An illustration of the virtual training case is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The VR training platform of scaffolding installation, including: (a) the complete virtual project and (b) scaffolding components and installation activities.

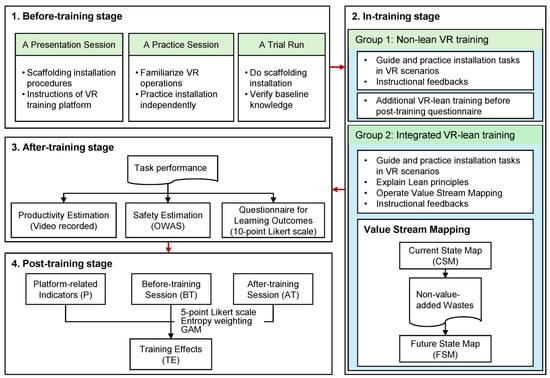

3.2. Training Design

The training design in this study is illustrated in Figure 2. First, all trainees attended a presentation covering the installation procedure and instructions for the VR-based training platform. This was followed by a practice session in which participants were familiarized with VR operations and practiced scaffolding installation independently.

Figure 2.

The training design and evaluation flowchart.

Subsequently, trainees were randomly assigned to one of two groups. A before-and-after experimental design was applied to minimize potential learning or carryover effects between training conditions.

- Group 1 received non-lean VR training, which simulated installation activities using the video-assisted feedback method [45]. No lean principles, waste identification, or optimization strategies were introduced. Trainers provided instructional feedback based on their observations of trainees’ task performance, with particular attention to error correction and basic guidance during installation.

- Group 2 received integrated VR and lean training. In addition to the basic VR training provided to Group 1, this approach embedded value stream mapping (VSM), a key lean construction tool, into the VR scenarios to serve as a structured guidance mechanism during task execution. Individual participants developed a current state map (CSM) using VSM to identify waste in each installation activity, such as rework, unnecessary travelling, idling, and poor planning. Based on this analysis, a future state map (FSM) was introduced to illustrate an optimized workflow with reduced waste.

To evaluate and compare the two approaches, after-training task performance was assessed through productivity and ergonomic safety indicators, along with a questionnaire on learning outcomes. A comparative analysis was conducted to quantitatively identify differences between the two groups. Details of assessment methods are presented in Section 3.5.

Finally, participants completed a post-training questionnaire to qualitatively assess training effects of the integrated training system. These subjective measures helped identify key factors influencing user engagement and the perceived impacts of the training. Based on the combined quantitative and qualitative findings, a framework was developed to guide future improvements of the integrated VR-lean training approach. Details of this post-training questionnaire are provided in Section 3.6.

3.3. Participants

A total of 64 participants were recruited for the experiment. All were undergraduate students enrolled in the civil engineering program at Southwest University, China, with a mean age of 22.4 years (range: 21 to 23). None had prior experience in scaffolding installation, lean, virtual reality, or occupational health and safety training. No-experience participants provide a relatively homogeneous baseline and a controlled experimental setting for comparing the effects of the two training approaches. Participants were randomly divided into two groups of 32 each. Given the exploratory nature of this study, this relatively small sample size was considered appropriate [46]. Moreover, a minimum of 30 participants per group was deemed sufficient, since performance comparisons were conducted using either a parametric or non-parametric t-test, depending on assumptions [47,48].

Two facilitators acted as both researchers and trainers. To reduce inconsistency, they worked with both groups, followed a standardized training protocol, and ensured identical task sequences and introductory materials, especially in the before-training stage. During the in-training stage, they provided feedback and guidance based on observed behaviors and performance for Group 1. For Group 2, they guided participants in applying lean principles via VSM, including the development of CSM and FSM. Throughout the experiment, facilitators closely monitored interactions within the virtual scenario through a real-time display. They systematically recorded performance, identified learning challenges and errors, and delivered tailored instructional interventions to support understanding and skill development.

3.4. Presentation and Practice

A 30 min presentation introduced participants to scaffolding installation and the VR training platform. The session included a video of onsite scaffolding installation and slides explaining the seven-step scaffolding installation process: checking components, placing base plates, inserting base plates, inserting transoms, installing ledgers, installing bracing, and conducting a final inspection. This simplified installation procedure was adopted to maintain consistency across trainees and to isolate the effects of lean integration. The experiment should therefore be viewed as an initial validation of the VR-lean concept under controlled conditions rather than a direct representation of all real-world scenarios. Nevertheless, the underlying framework is designed to be scalable to real construction operations, which often involve multi-level assemblies, dynamic site conditions, coordination among multiple workers, and unexpected operational variations.

Next, participants attended a practice session. This session was designed to familiarize them with VR operations (e.g., moving objects, interacting with scaffolding components) and the basic installation sequence under a virtual environment. Each trainee independently engaged with the virtual training scenario, applying the scaffolding skills introduced during the lecture. This session ensured a comparable baseline competence in VR operation before formal training. Both groups received identical practice content and duration, ensuring equivalent exposure.

Following the presentation and practice sessions, participants completed a trial run consisting of a full scaffolding installation. A t-test was conducted on trial-run performance to examine whether the two groups vary significantly in scaffolding installation performance before subsequent training.

3.5. Training Evaluation

Training performance was evaluated using scaffolding installation task performance on productivity and ergonomic safety indicators, as summarized in Table 1. For productivity, indicators included processing time, value-adding time, waste time, productivity index, and number of installation errors. To assess ergonomic risks, trainees’ working postures were recorded and analyzed using the Ovako Working Posture Analysis System (OWAS) method, a well-established method for identifying and mitigating harmful postures [49,50]. In this study, working posture was selected as a proxy indicator for scaffolding installation because awkward postures during reaching, lifting, and exerting force are common onsite risks and may lead to injuries [51].

Table 1.

Productivity and ergonomic safety indicators for evaluating training performance.

According to OWAS, scaffolding installation activities were assigned different codes in terms of the back (1–4), arms (1–3), legs (1–7), and lifting force (1–3). These codes were then used to classify risk categories (C1–C4), where C1 represents non-harmful postures and C4 represents extremely harmful postures requiring immediate correction. For example, a trainee working with a bent and twisted back, arms below shoulder level, kneeling legs, and a lifting force under 10 kg would be coded as 4161 and categorized as C4, the most hazardous level. Postural data were collected at 30-s intervals following the OWAS protocol [52]. Observed activities included erecting the scaffolding foundation, assembling ground-level scaffolding, and installing first-floor scaffolding in the virtual environment, all of which required intensive use of the back, arms, and legs during lifting tasks.

In this study, all video recordings were assessed independently by two trained researchers. Each researcher extracted the productivity indicators and coded the OWAS posture categories following a predefined protocol. The two sets of results were then compared, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached, ensuring a consistent interpretation of the assessment criteria.

In addition, participants completed a questionnaire survey using a 10-point Likert scale (1 = lowest awareness/satisfaction; 10 = highest awareness/satisfaction) to evaluate training outcomes, including waste identification, concept of value, ergonomic safety, and streamlined workflow (core knowledge areas in lean and ergonomic safety), as well as overall satisfaction. This survey was administered to both groups immediately after training for comparison. A t-test was conducted to determine whether the integrated VR training led to significant improvements in these measures.

3.6. Integrated VR-Lean Training Framework

A post-training questionnaire survey was designed to investigate factors influencing training effects of the integrated training. This questionnaire was identical for two groups. Participants completed the survey immediately after finishing the integrated VR-lean training. Those who initially received non-lean VR training later completed an additional round of integrated VR-lean training and were subsequently asked to fill out the questionnaire. Ten potential factors (shown in Table 2) were identified and grouped into four categories: platform-related indicators (P), before-training session (BT), after-training session (AT), and training effects (TE). Each factor was rated on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated “not important/useful at all” and 5 indicated “extremely important/useful”.

Table 2.

Factors influencing training effects of the integrated VR-lean system.

Nonlinear models were applied to explore the individual impacts of P, BT, and AT on TE. There are two steps. The first step involved applying the entropy weighting method to determine indicator weights and compute the integrated weights of the four categorical indicators. Values for each indicator are normalized using the following equation:

where is the normalized value of indicator .

The information entropy of each indicator was then calculated as:

where is the ith observation value of indicator .

The relative weight of indicator was expressed as:

Finally, the categorical indicator z was computed as:

In the second step, the contribution of each category of explanatory indicators (P, BT, or AT) to TE was independently estimated using a generalized additive model (GAM). GAM is a robust non-parametric model for modelling nonlinear relationships through local smooth spline functions [53]. The GAM can be expressed as:

where y is the response indicator, is its expected value, g is a link function, represents the regression spline function of explanatory indicator , and is the error term. The contributions of explanatory indicators were estimated based on the deviance explained in GAM. The GAM models were conducted using the R package “mgcv” (version 1.8-42) [54].

In addition, Pearson correlation analysis was performed to further identify various factors from P, BT, and AT influencing individual dimensions of TE. According to [55], correlation strength can be classified based on its coefficient: perfect (1), very strong (0.7–0.9), strong (0.4–0.6), moderate (0.3), weak (0.2), negligible (0.1) and none (0).

4. Results

4.1. Training Performance on Productivity

A t-test was conducted to compare the processing time of the two groups before VR-based training. The resulting p-value is 0.80, indicating no significant difference in baseline performance between groups. This finding confirms that neither group had prior knowledge of scaffolding installation, lean, VR, or occupational health and safety training. Thus, it is reasonable to investigate the differential impacts of non-lean and integrated VR-lean training by comparing after-training task performance.

A Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was performed to verify whether the training data followed a normal distribution and to determine the appropriate statistical test. Table 3 presents the results of the normality test for productivity indicators. The results show that processing time, value-adding time, waste time, productivity index, and number of errors are not normally distributed. Accordingly, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was selected to compare these indicators between the two groups.

Table 3.

Normality testing of productivity indicators using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

Table 4 summarizes the productivity performance of the non-lean VR and integrated VR-lean training systems, with individual participant data provided in Supplementary S1. Results indicate that integrated VR-lean training improved productivity performance, with gains of 12.3% in processing time, 21.6% in waste time, 20.8% in productivity index, and 18.4% in number of errors. These four indicators have p-values below 0.05, confirming that the integrated platform significantly outperformed the non-lean VR system. This outcome is expected, as lean is widely recognized to enhance productivity by eliminating waste [56]. In scaffolding installation, the most frequent forms of waste are rework, unnecessary travelling, and using incorrect scaffolding components, which explains the notable reduction in errors following the integrated VR-lean training.

Table 4.

Summary of productivity performance in non-lean and integrated VR-lean training.

In contrast, the integrated VR training did not result in a significant improvement in value-adding time. The mean value-adding time for non-lean VR training was 11.90 min, compared with 11.51 min for integrated VR training. The corresponding p-value of 0.435 indicates the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant. Value-adding activities are defined as those that transform materials into finished products or contribute to the form, fit, or function of the production flow [57]. Within this study, the application of VSM had minimal effect on value-adding activities but facilitated the identification and elimination of non-value-adding processes. Consequently, although value-adding time remained stable, overall productivity improved due to the decreased non-value-adding activities.

4.2. Training Performance on Ergonomic Safety

Table 5 presents the normality test for safety performance. Results show that all safety indicators deviate from a normal distribution; therefore, the non-parametric test, Mann–Whitney U, was applied to examine whether significant safety improvements occurred after the integrated VR-lean training.

Table 5.

Normality testing of safety indicators using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

Table 6 presents ergonomic safety performance indicators for both training modes. The overall risk index decreased by 7.2%, from 174.11 in non-lean VR training to 161.64 in integrated VR-lean training, which represented a statistically significant improvement. The number of high-risk activities in categories C3 and C4 declined by 38.5% (26 to 16) and 50% (8 to 4), respectively. The reduction in C3 was statistically significant (p = 0.037), whereas the reduction in C4 was not (p = 0.207). Overall, these results illustrate that integrating lean principles into traditional VR training enhanced safety performance.

Table 6.

Summary of safety performance in non-lean VR and integrated VR-lean training.

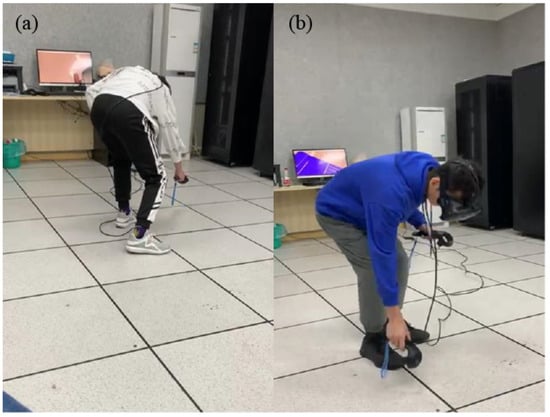

A detailed examination revealed that the most harmful postures occurred during the installation of baseplates into standards and the insertion of transoms and ledgers into standards. These postures included code 4141 (C4), characterized by a bent and twisted back, arms below shoulder level, and standing on two bent legs (Figure 3a), and code 2141 (C3), characterized by a bent back, arms below shoulder level, and standing on two bent legs (Figure 3b). Unnecessary rework in these activities increased the likelihood of trainees adopting these harmful postures. In contrast, other waste categories, such as unnecessary travelling, idling, and waiting, had minimal impact on the occurrence of harmful postures.

Figure 3.

The most harmful postures in the risk category of C4 (4141) (a) and C3 (2141) (b).

4.3. Evaluation of Learning Outcomes

Figure 4 illustrates a comparative analysis between Group 1 and 2 across five aspects of learning outcomes. The implementation of integrated VR-lean training substantially enhanced participants’ competency levels compared to non-lean VR training. Notable improvements were observed in waste identification (mean score increased from 4.2 to 7.7), concept of value (4.5 to 8.2), ergonomic safety (5.2 to 6.8), and streamlined workflow (4.5 to 9.1). A t-test confirmed that all improvements were statistically significant (p < 0.05). In addition, overall satisfaction increased from 5.8 to 7.5, underscoring the effectiveness of the integrated VR-lean training platform in enhancing competency and learning experience.

Figure 4.

Improvement in training outcomes from non-lean VR to integrated VR-lean training.

4.4. Factors Affecting Training Effects

Table 7 presents the GAM results for factors influencing training effects (TE) of the integrated VR-lean approach. Among the three categories, platform (P) and before-training sessions (BT) have higher impacts on TE, explaining 32.3% and 31.4% of the deviance, respectively. Both effects are statistically significant at the 0.01 level. In contrast, after-training session (AT) shows the lowest influence, contributing 6.2% of the total deviance, with statistical significance at the 0.05 level.

Table 7.

Individual impacts of platform, before- and after-training session on training effects.

Training effects of the integrated VR-lean training were determined by different aspects of training design. Table 8 shows the correlation results between individual dimensions of TE and various factors from P, BT, and AT. The results showed that training satisfaction (TE1) is strongly associated with platform-related indicators, including platform reliability and stability (P1, R = 0.47) and a user-friendly, easy-to-navigate interface (P2, R = 0.43). These correlations are significant at the 0.01 level. Second, ergonomic safety improvement (TE2) is strongly correlated with the feedback session (AT1, R = 0.49) and moderately correlated with platform reliability and stability (P1, R = 0.39) as well as the before-training session on the waste concept (BT2, R = 0.34). Third, these three indicators (AT1, BT2, P1) also emerge as the top three determinants of productivity improvement (TE3). Future enhancements should prioritize these factors to further strengthen the integrated VR-lean training experience.

Table 8.

Correlation results between training effects and factors from P, BT, and AT.

5. Discussions

VR techniques have proven effective in construction training by providing close-to-reality representations of construction environments, often delivering superior training experiences compared to traditional presentation-based methods. Although many studies have investigated the role of VR techniques in enhancing training experiences and satisfaction, some researchers, such as ref. [6], emphasize that work modes and construction theories—particularly those addressing inappropriate work or task sequencing—should not be overlooked. Lean principles are well recognized for their ability to identify and eliminate waste, thereby optimizing workflows and task sequences. This study demonstrates that integrating lean into VR training can improve training performance and outcomes, ultimately contributing to high productivity and safety in construction. This viewpoint is evidenced through the development and evaluation of an integrated VR-lean training system that combines VR and lean principles based on a scaffolding installation project.

The contributions of this study can be summarized in three main aspects. First, it validates that introducing lean principles into VR-based training environments enhances training performance. Numerous studies have demonstrated that lean can improve construction productivity. In accordance with prior research, this study finds that during the scaffolding installation process, lean practices improved four productivity indicators, including a 12.3% reduction in processing time, a 21.6% reduction in waste time, a 20.8% increase in productivity index, and an 18.4% decrease in the number of errors. Moreover, this study provides empirical evidence on the impact of lean principles on ergonomic safety. A few existing studies have examined the role of lean principles in improving safety performance, and most rely on qualitative investigations [16]. In the scaffolding installation context, non-value-adding activities such as rework, unnecessary traveling, communication, and idling have varying effects on harmful working postures. Among these, rework has a significant influence on the most harmful postures, categorized as C3 and C4 safety risk levels, while unnecessary traveling, communication, and idling have only a limited influence on posture-related safety performance. By minimizing unnecessary movements and overburden (muri), lean practices reduce physical strain associated with repetitive tasks and awkward postures, thereby mitigating musculoskeletal injury risks [11]. Furthermore, standardizing work processes promotes ergonomic best practices. As one trainee responded in the open-ended survey, “The standardized workflow really helps us avoid poor postures by ensuring everything is set at the right height and within easy reach, reducing strain on the body.” The continuous improvement philosophy of lean, particularly through the transition from CSM to FSM, empowers workers to collaboratively identify and address ergonomic challenges. Although lean training is primarily designed for waste elimination and efficiency, it enhances workers’ understanding of ergonomic principles. It is reflected in the observed increase in the mean value for ergonomic safety understanding, which rose from 5.2 in non-lean VR training to 6.8 in integrated VR-lean training.

Second, the findings suggest that productivity and safety can be achieved simultaneously in construction, demonstrating that one does not need to be sacrificed for the other. Integrating lean principles with VR-based training supports both objectives by streamlining processes and reducing hazardous work practices. Specifically, the integrated VR-lean training resulted in statistically significant improvements of 12.3% to 21.6% in processing time, waste time, productivity index, and number of errors (Table 4), while also reducing the overall risk index by 7.2% (Table 6). However, the effectiveness of this approach is constrained by the value-adding components specific to each case. In other words, the marginal benefits of lean practices tend to diminish as a project approaches complete waste elimination, a dynamic often overlooked in previous studies.

Third, this study provides practical guidance for the development of integrated VR-lean training platforms in construction. Although the effectiveness of VR in enhancing training is widely recognized, a few studies have explored factors influencing training satisfaction and effectiveness, particularly in relation to different objectives such as productivity and ergonomic safety. For example, ref. [44] argued that many studies evaluate VR training platforms through basic satisfaction surveys, without considering more substantive aspects such as user interaction with the system or the configuration of interactive elements. This study reveals that training effects in VR-lean training are strongly influenced by platform reliability and stability, as well as user-friendly, easy-to-navigate interfaces. However, the use of wired VR devices occasionally causes scenario interruptions due to disconnection, restricting the movement range of trainees and affecting the overall training experience. Furthermore, the absence of sound features reduced immersion; several trainees remarked that spatial audio would have made the environment more engaging and realistic. On the other hand, training effects were significantly affected by supplementary sessions: a before-training session explaining the concept of waste and an after-training feedback session discussing values and waste, particularly through FSM. These sessions were conducted in presentation format. However, one trainee suggested that training effects could be further enhanced if the system were capable of automatically detecting errors or inappropriate workflows during training and generating optimized workflows in real time. Such features would streamline learning and provide actionable insights to support continuous improvements.

However, this study still has several limitations. First, the VR-lean training experiment was conducted using a simplified seven-step scaffolding installation and involved 64 undergraduate civil engineering students without field experience. In practice, real-world installations are typically more complex and performed by skilled professional workers. Future research should therefore extend the integrated VR-lean framework to more complex and realistic construction tasks (e.g., multi-story scaffolding erection, formwork installation, and steel component assembly) and recruit employed construction workers to validate its generalizability and applicability in diverse engineering environments. Second, this study focused exclusively on ergonomic health and safety rather than overall occupational risks. Harmful working postures are an appropriate proxy for ergonomic safety; however, they cannot represent broader occupational safety, which also includes transportation accidents, contact with objects and equipment, and falls from heights. Further research should examine how lean principles affect these additional safety dimensions [58]. Third, the absence of audio limits the realism and comprehensiveness of the simulated scenario, while the wired VR configuration restricts trainees’ movement range. In future experiments, the VR-lean system will incorporate wireless VR devices and spatial auditory or other sensory cues to enhance immersion and support more natural user movements.

6. Conclusions

This study developed and evaluated an integrated VR-lean training system that incorporates lean principles to enhance construction training. VR is well recognized for its strengths in visualization and immersion, while lean thoughts are effective in identifying and eliminating waste and streamlining workflows. Accordingly, the proposed approach significantly improved productivity and ergonomic safety in scaffolding installation.

First, the integrated VR-lean training outperformed the non-lean VR training by substantially improving productivity. These benefits were primarily driven by the elimination of non-value-adding activities, such as rework, unnecessary traveling, and poor planning, through the application of VSM. Thus, this integrated VR-lean system can serve as a useful tool to pre-train workers in low-waste, standardized workflows in construction practices.

Second, integrating lean principles into VR technology resulted in a 7.2% improvement in the safety risk index, compared to non-lean VR training. In the context of scaffolding installation, this improvement was mainly attributed to the reduction of hazardous postures in rework activities. The study provides quantitative evidence of the synergy between lean practices and safety outcomes, confirming that productivity and safety can be achieved concurrently in construction.

Third, the study identifies four critical factors influencing the training effects of the integrated VR-lean training. These factors include platform reliability and stability (P1), user-friendly, easy-to-navigate interfaces (P2), before-training session on the waste concept (BT2) and post-training feedback (AT1). Notably, before-training on waste knowledge and after-training on optimized workflows significantly improved the training effects on productivity and safety. Furthermore, continuous improvement could be achieved if the future system can automatically detect errors or inappropriate workflows during training and generate optimized workflows in real time.

This integrated VR-lean approach provides a robust framework for advancing construction training by fostering workflow optimization and safety awareness. This study establishes a transformative precedent for incorporating lean thinking into immersive VR. It offers a scalable, evidence-based model that redefines training paradigms to drive systemic improvements in operational efficiency and workforce safety.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings15244534/s1, Table S1: The training performance of participants in the traditional VR training group; Table S2: The training performance of participants in the integrated VR training group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, validation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, R.L. Methodology, validation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, P.W. Investigation, visualization, writing—review and editing, C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Education and teaching Reform Research Project of Chongqing [grant number: 243060].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hasan, A.; Baroudi, B.; Elmualim, A.; Rameezdeen, R. Factors affecting construction productivity: A 30 year systematic review. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2018, 25, 916–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.; Brooks, J. Size Matters: Why Construction Productivity Is So Weak; Centre for Economic Development Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rathnayake, A.; Middleton, C. Systematic review of the literature on construction productivity. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 03123005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Labor. Commonly Used Statistics; Department of Labor: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Liao, L.; Liao, K.; Wei, N.; Ye, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, Z. A holistic evaluation of ergonomics application in health, safety, and environment management research for construction workers. Saf. Sci. 2023, 165, 106198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yi, W.; Chi, H.L.; Wang, X.; Chan, A.P. A critical review of virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR) applications in construction safety. Autom. Constr. 2018, 86, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Teizer, J.; Lee, J.K.; Eastman, C.M.; Venugopal, M. Building information modeling (BIM) and safety: Automatic safety checking of construction models and schedules. Autom. Constr. 2013, 29, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhalmahapatra, K.; Maiti, J.; Krishna, O. Assessment of virtual reality based safety training simulator for electric overhead crane operations. Saf. Sci. 2021, 139, 105241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G.; Fernández-Arias, P.; Antón-Sancho, Á.; Vergara, D. Examining the role of augmented reality and virtual reality in safety training. Electronics 2024, 13, 3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigwanto, A.; Widayati, N.; Wibowo, M.A.; Sari, E.M. Lean Construction: A Sustainability Operation for Government Projects. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, P.; Chi, H.L.; Li, X. Adopting lean thinking in virtual reality-based personalized operation training using value stream mapping. Autom. Constr. 2020, 119, 103355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, A.; Le, Q.T.; Park, C.S. Framework for integrating safety into construction methods education through interactive virtual reality. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2016, 142, 04015011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teizer, J.; Cheng, T.; Fang, Y. Location tracking and data visualization technology to advance construction ironworkers’ education and training in safety and productivity. Autom. Constr. 2013, 35, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Whyte, J.; Sacks, R. Construction safety and digital design: A review. Autom. Constr. 2012, 22, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahmens, I.; Ikuma, L.H. An Empirical Examination of the Relationship between Lean Construction and Safety in the Industrialized Housing Industry. Lean Constr. J. 2009, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambatese, J.A.; Pestana, C.; Lee, H.W. Alignment between lean principles and practices and worker safety behavior. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04016083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, P.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, T. Developing optimal scaffolding erection through the integration of lean and work posture analysis. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 2109–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, L.S.; Clarke, J.A.; Cullen, K.; Bielecky, A.; Severin, C.; Bigelow, P.L.; Irvin, E.; Culyer, A.; Mahood, Q. The effectiveness of occupational health and safety management system interventions: A systematic review. Saf. Sci. 2007, 45, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, A.; Borys, D.; Else, D. Management of Safety Rules and Procedure. A Review of the Literature; IOSH Research Committee: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Scaffolding; Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Jeelani, I.; Han, K.; Albert, A. Development of virtual reality and stereo-panoramic environments for construction safety training. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 1853–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, P.; Wang, J.; Chi, H.L.; Wang, X. A critical review of the use of virtual reality in construction engineering education and training. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; Kim, C.; Kim, H. Interactive modeler for construction equipment operation using augmented reality. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2012, 26, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juang, J.R.; Hung, W.H.; Kang, S.C. SimCrane 3D+: A crane simulator with kinesthetic and stereoscopic vision. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2013, 27, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.G.; Winkler, I.; Gomes, M.M.; Pinto, U.D.M. Ergonomic analysis supported by virtual reality: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the 2020 22nd Symposium on Virtual and Augmented Reality (SVR), Porto de Galinhas, Brazil, 7–10 November 2020; pp. 463–468. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, R.; Perlman, A.; Barak, R. Construction safety training using immersive virtual reality. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2013, 31, 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Q.T.; Pedro, A.; Park, C.S. A social virtual reality based construction safety education system for experiential learning. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2015, 79, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.; Serne, J.; Tafazzoli, M. Virtual reality safety training assessment in construction management and safety and health management programs. In Proceedings of the Computing in Civil Engineering 2023, Corvallis, OR, USA, 25–28 June 2023; pp. 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Scorgie, D.; Feng, Z.; Paes, D.; Parisi, F.; Yiu, T.; Lovreglio, R. Virtual reality for safety training: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Saf. Sci. 2024, 171, 106372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stork, S.; Schubö, A. Human cognition in manual assembly: Theories and applications. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2010, 24, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, P.; Holweg, M.; Rich, N. Learning to evolve: A review of contemporary lean thinking. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2004, 24, 994–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, T. Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production; Productivity Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Filip, F.; Marascu-Klein, V. The 5S lean method as a tool of industrial management performances. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2015; Volume 95, p. 012127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansah, R.H.; Sorooshian, S. Effect of lean tools to control external environment risks of construction projects. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 32, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek-Burlikowska, M.; Szewieczek, D. The Poka-Yoke method as an improving quality tool of operations in the process. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 2009, 36, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bajjou, M.S.; Chafi, A.; En-Nadi, A. The potential effectiveness of lean construction tools in promoting safety on construction sites. Int. J. Eng. Res. Afr. 2017, 33, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, A.; Pagell, M.; Johnston, D.; Veltri, A. When does lean hurt?—An exploration of lean practices and worker health and safety outcomes. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 3300–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Hao, J.L.; Qian, L.; Tam, V.W.; Sikora, K.S. Implementing lean construction techniques and management methods in Chinese projects: A case study in Suzhou, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 124944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, M.F.; Ramos, A.L.; Carneiro, P.; Gonçalves, M.A. A continuous improvement assessment tool, considering lean, safety and ergonomics. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2020, 11, 879–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yuan, H.; Wang, G.; Li, S.; Wu, G. Impacts of lean construction on safety systems: A system dynamics approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simukonda, W.; Emuze, F. A Perception Survey of Lean Management Practices for Safer Off-Site Construction. Buildings 2024, 14, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.h.; Yin, Y. Study on the mechanism of a lean construction safety planning and control system: An empirical analysis in China. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 101856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Man, F.; Han, S.; Kim, M.; Du, Q.; Chi, H.L. Integrating lean thinking into crane operator training with a digital coach to enhance safety and productivity in virtual environments. Autom. Constr. 2025, 178, 106430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, D.; Oh, S.H.; Kwon, H. Virtual reality for preoperative patient education: Impact on satisfaction, usability, and burnout from the perspective of new nurses. World J. Clin. Cases 2024, 12, 6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oseni, Z.; Than, H.H.; Kolakowska, E.; Chalmers, L.; Hanboonkunupakarn, B.; McGready, R. Video-based feedback as a method for training rural healthcare workers to manage medical emergencies: A pilot study. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, J. Sampling Essentials: Practical Guidelines for Making Sampling Choices; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- VanVoorhis, C.W.; Morgan, B.L. Understanding power and rules of thumb for determining sample sizes. Tutorials Quant. Methods Psychol. 2007, 3, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.K.; Park, J.H. More about the basic assumptions of t-test: Normality and sample size. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2019, 72, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurin, T.A.; de Macedo Guimarães, L.B. Ergonomic assessment of suspended scaffolds. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2006, 36, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, C.P.; Singh, A.K. Ergonomic study and design of the pulpit of a wire rod mill at an integrated steel plant. J. Ind. Eng. 2015, 2015, 412921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Buvens, M. Ergonomic evaluation of scaffold building. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 4338–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivi, P.; Mattila, M. Analysis and improvement of work postures in the building industry: Application of the computerised OWAS method. Appl. Ergon. 1991, 22, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastie, T.J. Generalized additive models. In Statistical Models in S; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 249–307. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.N. mgcv: GAMs and generalized ridge regression for R. R News 2001, 1, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Akoglu, H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 18, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Singh, H.; Singh, G. Productivity improvement using lean manufacturing in manufacturing industry of Northern India: A case study. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2018, 67, 1394–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, W.; Wang, J.; Wu, P.; Wang, X. Value adding and non-value adding activities in turnaround maintenance process: Classification, validation, and benefits. Prod. Plan. Control 2022, 31, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Aisheh, Y.I.; Tayeh, B.A.; Alaloul, W.S.; Almalki, A. Health and safety improvement in construction projects: A lean construction approach. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2022, 28, 1981–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).