Abstract

The social sustainability of Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) emphasizes that PPP investment should meet local residents’ public service requirements. However, due to profit seeking, the private sectors in PPPs may ignore public requirements, which leads to the distribution of PPP investment in infrastructure sectors away from social sustainability. However, the evaluation of PPPs’ investment distribution with consideration for the public requirements has not received sufficient attention. Meanwhile, the underlying influencing factors also remain unexplored. Based on the priorities of public requirements, this study evaluated PPPs’ social sustainability effects (PPPSEs) to analyze whether the distribution of PPP investment in infrastructure sectors matches these priorities. Furthermore, this study empirically analyzed the factors that influence PPPSEs. This study used the data from China’s 28 provincial-level regions from 2017 to 2021. The results indicate that the PPPSEs vary across different regions in China. Regarding the influencing factors, the purchasing power of local residents, fiscal pressure, and PPP project experience significantly influenced the PPPSEs. This study supports decision making in choosing PPP projects and managing the PPP mode from the perspective of social sustainability.

1. Introduction

Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) refer to a long-term cooperative relationship used to develop the infrastructure and infrastructure-based public services [1,2]. Recently, PPPs have been advocated in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—launched by the United Nations in 2015—to mobilize and share expertise, technology, and financial resources to enhance regional sustainable development [3]. Besaiso et al. [4] and Shi et al. [5] indicated that “sustainability” is emerging as a key topic for future PPP studies through bibliometric research in the PPP literature. To achieve this target, it is necessary to evaluate whether PPP development is aligned with sustainable development [6,7,8]. While the economic (e.g., the value for money) and environmental (e.g., the use of eco-friendly materials) dimensions have been more extensively examined [4,9,10], the social aspect has been addressed in more selective ways. Prior studies have focused on public participation [10,11], project stakeholders’ well-being [12], the affordability of public services for vulnerable groups and equal opportunity [10,13,14], and employment opportunity and household income [14] in the implementation of PPPs. However, these studies have mainly focused on the externalities of PPPs at the project level, aiming to translate the SDGs into concrete actions during the project process, and have not explored to the same degree such externalities from a regional perspective [15].

At the regional level, Yuan, Zhang, Tanm and Skibniewski [15] defined PPPs’ social sustainability as improving the local social access to necessary public services for both present and future generations through introducing private sectors. However, there may be a conflict between the private sector’s tendency towards high-profit infrastructure projects and the public service requirements of local residents [7,10,16], which results in PPP development not being aligned with sustainable development. For the private sector, the motivation to participate in PPP projects is to maximize profit rather than meet public requirements, leading them to prioritize large-scale, heavy, or long and stable profitable infrastructure sectors [1,9,12,17], finally resulting in the infrastructure sectors related to public requirements being neglected [10,16,18]. Meanwhile, unbalanced PPP investments will also shift costs to future administrations and users. Future generations may not have access to certain necessary public services and be forced to reinvest in them [7,16].

On the other hand, the analysis of influencing factors is also a key issue in PPP studies [19], as it can reveal the underlying mechanisms behind PPP development and support developing effective management strategies [11]. Previous studies have identified a set of influencing factors or drivers/determinants/critical success factors for PPP development, such as the deficit situation, infrastructure demand, the economic environment, government effectiveness, and early PPP project experience [2,15,20,21,22]. However, these studies have mainly used these factors to explain the scale of PPP investment—such as the number or total investment of PPP projects—and have used these factors less to explain the PPPs’ effects on sustainable development, especially the social dimension. Wang and Ma [23] reviewed the sustainability-oriented PPP studies and suggested that the influencing factors and barriers for PPPs in promoting sustainable development require further exploration.

In summary, the evaluation of PPPs’ effects on sustainable development has always developed from the perspectives of economy and environment, while the social dimension should receive greater attention [15]. Furthermore, in the social dimension, due to profit seeking, the private sector in PPPs may ignore public requirements, which leads to the distribution of PPP investment in infrastructure sectors away from social sustainability [7,10,16]. However, the evaluation of PPPs’ investment distribution with consideration for the public requirements has not received sufficient attention. Meanwhile, the influencing factors underlying PPP investment distribution remain unexplored. Many influencing factors have been used to explain the PPP investment scale, rather than the PPP investment distribution [23].

Against this background, the research question of this study is as follows: considering the public requirements and the PPPs’ investment distribution, what is the development status of the social sustainability of PPPs, and what underlying factors influence this? This study aims to evaluate the PPPs’ social sustainability effects (PPPSEs)—which reflect whether the distribution of PPP investment in infrastructure sectors aligns with the priorities of public requirements—and further explore the underlying influencing factors behind the effects. This study used the data from China’s 28 provincial-level regions from 2017 to 2021. The results indicate that the PPPSEs vary across different regions in China, and that the purchasing power of local residents, fiscal pressure, and PPP project experience significantly influence the PPPSEs. These empirical findings contribute to research on the sustainability of PPPs in two ways: how to understand the effects of PPPs in the context of social sustainability, and how to consider regional conditions and project experience when initiating PPP projects. Particularly, this study provides an analysis of the distribution of PPP investment. Previous studies have mainly focused on the overall scale of PPP investment rather than its sub-sectoral structure.

The rest of this study is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the social sustainability of PPPs and its underlying influencing factors. Section 3 introduces the methodology, including the model for evaluating PPPSEs, the research hypotheses, and the model for analyzing influencing factors. Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 and Section 6 discuss and conclude, respectively.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Social Sustainability of PPP

Sustainable development means that the present generation develops without compromising the ability of future generations to do so—i.e., intergenerational equity [16], and always cites the three dimensions of economy, environment, and society (Triple Bottom Line, TBL) to analyze intragenerational equity [7,10,18]. Existing studies on the evaluation of PPPs’ sustainability have also mainly developed from the perspective of TBL [6]. In TBL, the economic dimension has been extensively studied, especially the value for money (VFM), which focuses on whether the PPPs alleviate the long-term fiscal burden of public investment [5,7,9,24]. On the other hand, some mainstream infrastructure sustainability evaluation tools—such as Envision, Civil Engineering Environmental Quality Assessment and Awards Scheme (CEEQUAL), and Infrastructure Sustainability Rating Tool (IS)—mainly focus on environmental issues, such as the use of eco-friendly materials [25]. The social dimension should receive greater attention [9,25].

Social sustainability is closely related to the quality of life of local residents, which will impose high demands on the infrastructure and infrastructure-based public services [7,16,25,26,27]. Cuthill [28] indicated that a direct way to improve social sustainability is to develop public services. As a particular delivery mode for public services, the improvement of the accessibility of public services can serve as a fundamental criterion for measuring the PPPSEs [29]. In this vein, Yuan, Zhang, Tan, and Skibniewski [15] developed a framework of the PPPs’ social sustainability. The framework indicated that, in the social dimension, the function of PPPs is to provide public services for local residents through introducing non-government capital, and the effects of PPPs on social sustainability refer to improving the social access to public services by leveraging private sectors [15]. According to this connotation, the “social sustainability effects” can be measured by the degree of improvement in the social access to public services [15,28]. And, for PPPs, the “PPPs’ social sustainability effects” can be measured by the impact of PPP investment on this accessibility, or, alternatively, by the degree to which the PPPs’ investment distribution aligns with and contributes to the public requirements [15,28]. If PPPs’ investment distribution aligns with the public requirements, this means that the PPP investment not only enables the present generation to obtain the necessary public services—i.e., to ensure intragenerational equity [10,16,18], but also does not compromise the ability of future generations to obtain their needed public services (e.g., avoiding future generations not having access to necessary public services and being forced to reinvest in them)—i.e., to ensure intergenerational equity [7,16].

However, although PPPs can drive private sectors to invest in infrastructure and benefit the public by introducing non-government capital [30], the private participants in PPPs may harm public interest [12]. Because the private sectors are profit-driven, they may prefer to invest in infrastructure sectors that have more profit opportunities and will not proactively consider public requirements [1,27,30]. Some infrastructure sectors may be unprofitable, but are indeed necessary for local residents [16]. This preference of the private sector may result in some infrastructure sectors related to public requirements being neglected, which can lead to unbalanced PPP investment across infrastructure sectors—such as unnecessary public supplement (over-investment) or under-investment, hidden debt, and budgetary burden—all of which will lead to unequal development, ultimately destroying social sustainability [6,18,31]. For example, Cuthill [28] indicated that, in South East Queensland, more than 70% of the infrastructure plan is invested in some specific infrastructure sectors, such as road, while the “social and community infrastructure (including health, education, and others)” is neglected. However, these social and community infrastructure projects are urgently needed, and yet, due to underfunding in this infrastructure allocation, they are effectively neglected, which will result in negative social outcomes [28]. Patil, Tharun, and Laishram [6] indicated that, in India, due to better profitability, more than 80% of the PPP investment has been invested in transport sectors as of March 2012, and other, less profitable sectors failed to attract sufficient private sector investment. A similar phenomenon has also been observed in China. Cheng et al. [32] indicated that toll road projects are more attractive to the private sector in China, as these projects usually have a higher financial self-liquidation ratio.

Therefore, to prevent PPPs from deviating from social sustainability, it is necessary to examine the priority public service requirements of local residents and direct PPP investment toward meeting these requirements [9,10]. Wang and Ma [23] indicated that the social sustainability of PPPs should align with a people-first principle. Public attitudes and expectations should be considered prior to selecting PPP projects [24]. She, Shen, Jiao, Zuo, Tam, and Yan [8] suggested that public services essential to people should receive sufficient policy attention.

2.2. The Influencing Factors of PPP Development

Currently, in order to reveal the underlying mechanisms behind PPP development and support the formulation of management strategies, many studies have aimed to gain insight into the factors influencing PPP development—such as the drivers or determinants of PPP mode adoption, and the critical success factors of PPP project implementation [26]. These previous studies typically focused on the influencing factors, such as the macro-economic environment [33], fiscal environment [31], political environment [34], PPP experience [35], and others. Consensus has largely been reached regarding these factors. Therefore, this study screened several quantitative empirical studies that consider different dependent variables reflecting PPP development to review the research on this issue, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Previous studies related to the factors influencing PPP development.

Although consensus has largely been reached regarding these factors, the same factor exerts different influencing effects on different dependent variables. For example, regarding the influencing factor of the PPP fund, Tan and Zhao [34] observed that it has a significant impact on the PPP adoption rate, and Fleta-Asin and Munoz [21] observed that it has a significant impact on the degree of private involvement in PPPs in renewable energies; however, Guo et al. [36] found no significant effect of this factor on PPP number. Therefore, from the perspective of influencing factors, it is also necessary to explore different dependent variable contexts to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of these factors. Specifically, most previous studies focused on the scale of PPP investment, such as the number of PPP projects and the total PPP investment. The distribution of PPP investment across the infrastructure sector has received less attention. Meanwhile, the concept of sustainability features less in these empirical studies [7], particularly social sustainability.

3. Methodology

3.1. The Model for Evaluating PPPSE

In recent years, China has been promoting the adoption of PPPs and has a large PPP market globally [36,37], meaning abundant empirical data is available for research in China. Meanwhile, in August 2016, China issued a document titled “Effectively Implement Public–Private Partnerships in Traditional Infrastructure Sectors” to introduce PPPs into several infrastructure sectors [38], thereby enabling observation of the distribution of PPP investment across different infrastructure sectors. Particularly, China is committed to utilizing PPPs to improve the provision of public services and promote regional sustainable development [39], where it has various exploitable empirical experiences. Therefore, China has rich project experience, relevant issues regarding the investment distribution, and a fitting research context, which offer reference value for other regions worldwide. In this vein, this study chose China as the research case.

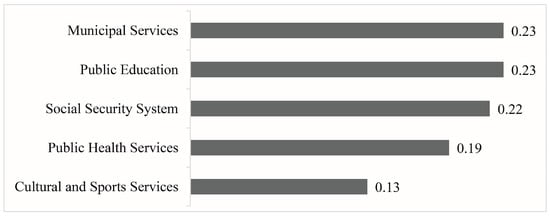

Yuan, Zhang, Tan, and Skibniewski [15] have proposed a social sustainability contribution evaluation system (SSCES) for PPP applicable to China, which identifies the public service requirements for socially sustainable development and the priority weights of each requirement, including municipal services, public education, social security systems, public health services, and cultural and sports services. These requirements and their weights are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The public service requirements with weights from SSCES for PPPs.

In Figure 1, the high-weight public service requirements include municipal services, public education, social security systems, and public health services, with weights of 0.23, 0.23, 0.22, and 0.19, respectively. These public services are closely related to the basic living needs. From the perspective of social welfare, projects in these infrastructure sectors often lack significant profitability [6,40]. Cultural and sports services have a relatively low weight, which are improvement-oriented public services for enhancing well-being; they are not basic needs.

To improve social sustainability, infrastructure sectors related to high-weight public service requirements should be prioritized in PPP investment. PPP investments should prioritize meeting more important public requirements. Based on the SSCES for PPPs proposed by Yuan, Zhang, Tan, and Skibniewski [15], this study further developed the calculation formula for PPPSEs, which adopts the following multi-criteria evaluation method:

where is the weight of the public service requirements, and is a proportion index, which is the proportion of PPP investment in the infrastructure sector corresponding to relative to total PPP investment in a region, multiplied by 100.

PPPSEs can reflect whether PPP investment aligns with public requirements. According to the calculation formula of PPPSEs, if PPP investment is concentrated in the high-weight public service requirements, then, in terms of social sustainability, the PPP mode has been properly utilized and matches public requirements, and the PPPSE value will be large. Conversely, if low-weight public service requirements account for a large share of PPP investment, it indicates that the PPP mode has not been properly utilized and does not match the public requirements, leading to a small PPPSE value. By calculating the PPPSEs, it is possible to determine whether the private sectors in different regions can improve social access to public services when investing in infrastructure. Furthermore, it should be noted that this does not mean the low-weight public service requirements are off-limits for PPP investment, but rather that they should not be over-invested in it.

3.2. Research Hypotheses of Influencing Factors

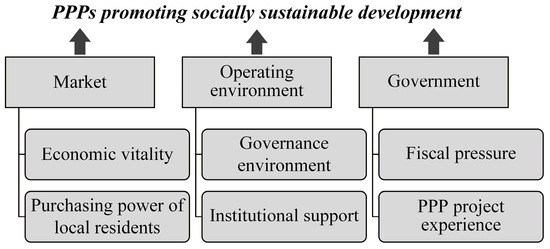

The research hypothesis framework of the factors that may influence PPPSEs is built upon a generic framework developed by Yang et al. [41]. This framework explains the PPP development environment in three dimensions: market, operating environment, and government. This framework has been adopted by many studies on drivers, critical success factors, and determinants of PPPs, such as Guo, alvarezA, Yuan, and Kato [36], Tan and Zhao [34], and Pan et al. [42]. Based on the framework of Yang, Hou, and Wang [41], the research hypothesis framework used in this study is presented in Figure 2. And the research hypotheses of influencing factors are as follows.

Figure 2.

The research hypothesis framework of the influencing factors.

As noted in previous studies, economic vitality is a key factor in implementing sustainable PPPs [35,43,44,45]. For the private sector, a vibrant economic environment means lower project-related uncertainties [21]. On the one hand, a vibrant economic environment means that the PPP project will more easily secure financing, which can reduce the costs of implementation [17,43]. On the other hand, regions with vibrant economies tend to have greater infrastructure demands, which can guarantee the revenue of PPP projects [17,21,35]. When the uncertainties surrounding the project are reduced, the private sector will worry less about its own returns. Thus, its profit-seeking tendencies will be reduced, and it will be more willing to invest in infrastructure sectors that are related to public requirements. Consequently, this study proposed the first research hypothesis:

RH1.

Economic vitality is positively correlated with the PPPSEs.

Meanwhile, for the revised PPP mode and user-paid PPP projects, local residents are the end-users of PPP projects, and their purchasing power will affect the revenue risk of PPP projects [35,46]. The greater purchasing power of local residents can ensure the revenue of PPP projects and boost the private sector’s future expectations [47], thereby reducing its overemphasis on project profitability. Consequently, this study proposed the second research hypothesis:

RH2.

The purchasing power of local residents is positively correlated with the PPPSEs.

A sound governance environment can regulate the private sector’s investment behaviors [19,21,45], which can ensure that PPP investment meets public requirements. There is no specific PPP law at the national level in China [36]. The governance environment cannot be directly measured by the legal environment. Therefore, this study considered specialized PPP governance units established by governments that vary across regions in China. These units are typically responsible for administrative governance, including project evaluation and selection, project information collection, and monitoring for all PPP projects within their jurisdictions—such as the Shandong PPP governance unit [48] and Henan PPP governance unit [49]. With the establishment of these units, public requirements can be thoroughly considered. PPP projects failing to meet these requirements or lacking priority will not be approved. These units strengthen the public control over PPPs [46,47], which can ensure that the distribution of PPP investment responds to public requirements. Consequently, this study proposed the third research hypothesis:

RH3.

The establishment of a PPP governance unit is positively correlated with the PPPSEs.

In terms of institutional support, this study referred to Guo, alvarezA, Yuan, and Kato [36] and Tan and Zhao [34], who considered regional PPP funds. High-profit infrastructure projects are easily financed due to their higher returns. These projects are expected to receive more attention from the private sector. PPP funds can alleviate the private sector’s financing burden [21,34,50], thereby improving the financial attractiveness of projects with higher social value and reducing the private sector’s focus on those projects with higher economic value. Consequently, this study proposed the fourth research hypothesis:

RH4.

The establishment of PPP funds is positively correlated with the PPPSEs.

Existing studies have indicated that it is difficult for local governments lacking sufficient fiscal capacity to implement PPPs [32,34]. When fiscal revenue struggles to cover public expenditure, governments may lack the capacity to alleviate the operational pressure of the private sector through industry subsidies and other forms of support, which will destroy the confidence of the private sector [35,51]. Therefore, the high fiscal pressure will hinder the implementation of PPP projects and will cause private sectors to pursue high-profit projects for self-protection rather than focus on public requirements. Consequently, this study proposed the fifth research hypothesis:

RH5.

The fiscal pressure is negatively correlated with the PPPSEs.

Governments’ prior experience with PPP projects can improve PPPSEs in various ways. On the one hand, the credibility obtained by governments through honoring commitments in previous projects is a key factor attracting the private sector to invest in PPP projects [35]. Governments’ credibility can boost the private sector’s expectations of project returns [52], which can reduce their preference for high-profit projects. On the other hand, project experience is crucial for enhancing governments’ capacity to manage PPPs [50]. Governments with rich PPP project experience tend to have strengths in negotiating, operating, and supervising PPP projects [22], which ensures that the private sector does not neglect public requirements. Therefore, PPP project experience can support PPP development towards social sustainability. Consequently, this study proposed the sixth research hypothesis:

RH6.

PPP project experience is positively correlated with the PPPSEs.

3.3. The Model and Variables for Exploring Influencing Factors

In China, there may be some underlying time-varying unique characteristics (such as macro investment environment and PPP-related regulations) that cause PPP development to fluctuate over time [32]. Therefore, when choosing the econometric model for testing RH1–RH6, the fixed effects model was adopted. In particular, the error term is associated with the temporal dimension. This model can control for the impacts of time-varying variables, making it suitable for examining the causes of changes within an entity [35].

In this case, this study developed the Model PPPSE as follows:

where β is the coefficient value, X is the independent variable of the influencing factor (0–1 variable does not take logarithms), i is the region, t is the year, μ is the time fixed, and ε is a random error.

PPPSE was taken as the dependent variable. The relevant literature was reviewed to identify the independent variables. Table 2 presents the research hypotheses, independent variables, and the previous literature that used these variables.

Table 2.

Independent variables in this study.

3.4. Data Set

The data used in this study were obtained from China, and the data samples exclude Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan. Additionally, the data samples also exclude regions which rarely use the PPP mode—Shanghai, Tianjin, and Xizang. Finally, the samples in this study include 28 provincial-level regions (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Xizang).

PPP investment data were collected from the China Ministry of Finance (MF) PPP database (www.cpppc.org). Since the public service requirements and their weights in PPPSE Formula (1) are derived from the SSCES for PPPs proposed by Yuan, Zhang, Tan, and Skibniewski [15]—with the weights based on a 2017 survey that reflects the public preferences after 2017—this study has selected data from 2017 onwards to align the evaluation data with the model. Furthermore, due to data availability, the data covers the period up to 2021. Finally, the data covers the period from 2017 to 2021 and was collected in January 2022. The MF PPP database is an official database that contains information on all PPP projects in China and has been used in numerous studies on PPPs, such as Guo, alvarezA, Yuan, and Kato [36], Feng and Zhang [51], Xiong et al. [54], Tan and Zhao [34], and Cheng, Yang, Gao, Tao, and Xu [33]. In particular, in November 2023, China issued a document titled “Guiding Opinions on Standardizing the Implementation of a New Mechanism for Public–Private Partnerships (abbreviated as China PPP New Mechanism)”, which determined the future development of PPPs in China and particularly adjusted the application scope of PPP mode to a user-pays franchise scheme [55]. In the future, China’s new PPP projects can only be user-pay projects. Therefore, to ensure the findings are meaningful for future research, the data samples, in line with the revised PPP mode, include only user-pays PPP projects. Furthermore, the MF PPP database includes the infrastructure sector categories for each PPP project. Based on this, this study screened the PPP projects in the five sectors specified in the SSCES for PPPs—municipal services, public education, social security systems, public health services, and cultural and sports services—and calculated their investment amounts. Particularly, for comprehensive development projects involving multiple sub-projects—such as integrated infrastructure or area development—that do not fall within the five sectors (e.g., smart city and small-town development), this study further examined their construction content (also available in the MF PPP database). If they involve content related to the five sectors, this study considered them to have improved the accessibility of public services in the corresponding sectors and included them in the statistics of these sectors.

For data on influencing factors, since the private sector’s or government’s decisions are usually based on the previous year’s conditions rather than the current year’s, the independent variables are lagging by one year, taking the value from 2016 to 2020 (whereas the dependent variable PPPSE takes the value from 2017 to 2021). This address can also avoid potential endogeneity problems resulting from two-way causality [42]. GDPR, PINC, and FISRAT data were obtained from the China Statistical Yearbook 2017–2021. The PPPUNIT and PPPFUND data were obtained from the authors’ own statistics. PPPHIST data were obtained from the MF PPP database.

4. Results

4.1. The Results of PPPSEs

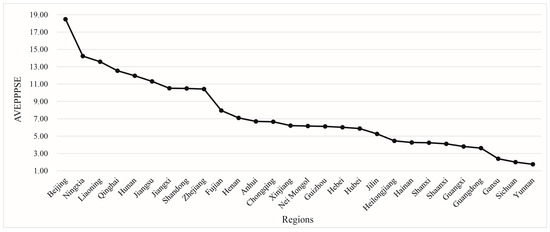

Using Formula (1), this study calculated the PPPSEs in China’s 28 provincial-level regions (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Xizang) from 2017 to 2021. The results are presented in Table A1 in Appendix A. To more clearly illustrate the distribution of PPPSEs, this study further calculated the average PPPSEs (AVEPPPSE) in each region between 2017 and 2021, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The AVEPPPSE in China’s 28 provincial-level regions between 2017 and 2021.

According to the results in Table A1 (in Appendix A) and Figure 3, the PPPSEs vary across regions and years in China. In terms of average PPPSE levels, some regions—such as Beijing, Ningxia, Liaoning, Qinghai, and Hunan—exhibit a higher AVEPPPSE. However, some regions—such as Yunnan, Sichuan, Gansu, Guangdong, and Guangxi—exhibit a lower AVEPPPSE. In particular, there is a substantial gap between the high and low values of AVEPPPSE, with the highest AVEPPPSE values (in Beijing, Ningxia, and Liaoning) exceeding 13, but the lowest AVEPPPSE values (in Yunnan, Sichuan, and Gansu) are below 3. Furthermore, some regions saw significant fluctuations in their PPPSE values between 2017 and 2020. For example, the PPPSE value in Shanxi has a large variance of 45.91, with a maximum value of 17.78 (year 2017) but a minimum value of 0.64 (year 2020). Meanwhile, Zhejiang’s PPPSE value has a variance of 14.87, with a maximum value of 16.92 (year 2017) but a minimum value of 6.37 (year 2020). In summary, in China, from 2017 to 2021, PPPSEs exhibit significant variation in different regions and years, and the alignment between PPP investment and public requirements shows spatial differentiation and temporal fluctuations. In the following sections, econometric models will be used to explain the variation in PPPSEs.

4.2. The Results of Influencing Factors

Based on the PPPSE model in Formula (2), this study developed seven empirical models to identify the optimal model with the most significant effects on PPPSEs across contexts involving individual or combined influencing factors. First, the influencing factors of each of the three dimensions were separately incorporated into the PPPSE model, designated as Models 1, 2, and 3. Model 1 includes the market dimension factors (RH1 and RH2); Model 2 includes the operating environment dimension factors (RH3 and RH4); and Model 3 includes the government dimension factors (RH5 and RH6). Second, the influencing factors of pairwise dimension combinations were separately incorporated into the PPPSE model, designated as Models 4, 5, and 6. Model 4 includes factors from the market and operating environment dimensions (RH1, RH2, RH3, and RH4); Model 5 includes factors from the market and government dimensions (RH1, RH2, RH5, and RH6); and Model 6 includes factors from the operating environment and government dimensions (RH3, RH4, RH5, and RH6). Finally, the influencing factors of all three dimensions were incorporated into the PPPSE model, designated as Model 7, which includes factors from the market, operating environment, and government dimensions (RH1–RH6). The results of Models 1–7 are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The results of Model 1 to Model 7.

Based on the results, across Models 1–7 with different combinations of influencing factors, PINC, FISRAT, and PPPHIST are all statistically significant. To test RH1–RH6, this study ultimately selected Model 7 for discussing the findings. Furthermore, the variance inflation factor (VIF) values in Model 7 range from 1.019 to 2.689. All VIF values are below 10, indicating the absence of multicollinearity issues [53].

In Model 7, three research hypotheses are statistically significant: RH2 in the market dimension, and RH5 and RH6 in the government dimension, pertaining to local residents’ purchasing power (PINC), fiscal pressure (FISRAT), and PPP project experience (PPPHIST). Conversely, three research hypotheses are not statistically significant: RH1 in the market dimension, and RH3 and RH4 in the operating environment dimension, involving economic vitality (GDPR), PPP governance units (PPPUNIT), and PPP funds (PPPFUND).

Regarding the estimated coefficients of the significant factors, the coefficient for PINC is positive, supporting RH2. The coefficient for FISRAT is positive, contrary to the expectation in RH5. The coefficient for PPPHIST is negative, contrary to the expectation in RH6. These results will be discussed in the following section.

Furthermore, this study tested the robustness of the results using two methods: replacing the dependent variable data and excluding extreme values from the sample [42,44]. First, for the dependent variable PPPSE, the calculated data were replaced with percentile rank data, designated as Model R1. Second, given the considerable variation in PPPSEs across regions and years, to mitigate the impact of extreme values, this study winsorized the top and bottom 5% of the sample, designated as Model R2. The robustness test results are presented in Table 4, where Models R1 and R2 exhibited the same sign directions and significance levels as Model 7. Thus, the robustness of the results is confirmed.

Table 4.

The robustness test results.

5. Discussion

5.1. The PPPSEs and Influencing Factors

The evaluation of PPPSEs in this study considers the priority difference in public requirements. Based on the data from China, the evaluation results indicate significant regional and annual variations in PPPSEs. Based on the research hypotheses (RH1–RH6), six factors influence PPPSEs in China, though they differ in statistical significance and direction of effect. Among these, RH2, RH5, and RH6 are statistically significant and thus supported, and the estimated coefficient of RH2 is consistent with its hypothesis, but the estimated coefficients of RH5 and RH6 are contrary to their respective hypotheses. Additionally, RH1, RH3, and RH4 are not statistically significant and thus rejected. This study will first discuss the statistically significant hypotheses (RH2, RH5, and RH6) in turn, then collectively address the statistically insignificant ones (RH1, RH3, and RH4). The statistical significance and direction of effect of each hypothesis will be further explained in a separate discussion.

First, PINC (reflecting the purchasing power of local residents) is a significant influencing factor, and the estimated coefficient of PINC is positive, which supports RH2. Purchasing power determines whether local residents can pay for public services [22]. This is important for the revised PPP mode in the context of China PPP New Mechanism, as it determines the revenue risk of user-pays PPP projects [35,46]. Stronger purchasing power of local residents can boost the future expectations of private sectors, so they are less preoccupied with project profitability. When the profit-seeking tendencies of the private sectors are reduced, they engage in more socially sustainable behaviors.

Second, FISRAT (reflecting fiscal pressure) is a significant influencing factor, but the estimated coefficient of FISRAT is positive, which is contrary to the expectation in RH5. RH5 argues that fiscal pressure reduces PPPSEs by destroying the confidence of the private sector. This opposing phenomenon may be due to the government’s motivation to develop PPPs. The function of PPPs is to finance infrastructure, particularly under huge fiscal pressure [20,36]. When the governments’ financial capital is insufficient to cover the public service requirements, they value the non-government capital brought by PPPs and introduce these capitals to prioritize the basic needs and high-weight public service requirements. Consequently, social sustainability is promoted. This result is supported by empirical evidence. An enormous culture–tourism PPP project (which has low priority in SSCESs for PPPs)—City Park PPP Project—in Yuzhong (a county-level region which faces enormous fiscal pressure in Gansu) has been widely disputed as it not introducing PPP investment into high-priority infrastructure sectors [56]. This project has been questioned precisely for violating the principles of social sustainability. Thus, the local governments, especially those under huge fiscal pressure, tend to pay greater attention to this issue.

Third, PPPHIST (reflecting PPP project experience) is a significant influencing factor, but the estimated coefficient of PPPHIST is negative, which is contrary to the expectation in RH6. RH6 argues that PPP project experience can enhance PPPSEs by improving government credibility and capacity. However, these positive effects may be offset by local governments’ path dependence—meaning that governments may prefer to invest in infrastructure sectors with which they are familiar and have relevant experience [32,57]. Governments tend to accept familiar things, particularly when they have experienced them [58]. To explain this result, this study further identified regions with the most extensive PPP project experience. For example, in Yunnan and Sichuan, PPP investment has long focused on transport: the annual share of transport PPP projects in total PPP investment from 2017 to 2021 has been approximately 50%. Transport projects are more profitable and more attractive to private sectors [6], but this may be over-invested, which leads to the neglect of other public requirements. Owing to path dependence, governments may continue to invest in these infrastructure sectors because they are familiar with and have experience in these sectors [32,57,58], although these sectors are not priority sectors for local residents. Consequently, the PPPSE values continue to be low in these regions (see Table A1), which reflects the potential effects of path dependence on social sustainability. This study further examines the condition of PPP development to explain why experience leads to a lock-in effect rather than the learning effect which can improve government’s capacity. There is a unique cadre incentive mechanism in China—the political tournament system—which ties officials’ promotions to their administrative performance [59]. The political tournament system affects the government’s behaviors in PPPs. In order to gain political advancement through performance achievements, local officials may pursue increasing infrastructure investments in the short term to boost the economy [60]. Consequently, the local governments tend to prefer rapid investment in the sectors they are familiar with, ultimately leading to redundant construction and resource waste [59]. That is, under the condition of the political tournament system, the experience may be treated as a short-term asset rather than a long-term learning asset.

Finally, the influences of GDPR, PPPUNIT, and PPPFUND on PPPSEs are not significant, indicating that economic vitality, PPP governance units, and PPP funds do not influence the distribution of PPP investment in infrastructure sectors, at least for the sample analyzed; consequently, RH1, RH3, and RH4 are rejected. This evidence is inconsistent with the results of previous studies. For example, Panayides, Parola, and Lam [53] observed a significant relationship between GDPR and PPP investment scale, and Tan and Zhao [34] observed a significant relationship between PPPUNIT, PPPFUND, and PPP adoption rate. This may be due to the differences in dependent variables. Previous studies have focused on the scale of PPP investment, but this study focuses on the distribution of PPP investment—the PPPSEs reflect the proportion of different infrastructure sectors in a given region. Panayides, Parola, and Lam [53] used GDPR to explain the scale of PPP investment, specifically in the vertical sector of ports; this dependent variable cannot reflect the horizontal distribution of PPP investment across different infrastructure sectors, like this study does. Tan and Zhao [34] used PPPUNIT and PPPFUND to explain PPP adoption rate, and the underlying mechanism is that PPPUNIT and PPPFUND create better institutional support for PPP implementation. However, in RH3 and RH4, this study assumed that PPPUNIT and PPPFUND can intervene in the private sector’s investment tendencies through environmental governance. One possibility is that PPPUNIT and PPPFUND have played a promotional role, but have not yet played a governance role. This is also emphasized in China PPP New Mechanism. China PPP New Mechanism points out that the local governments should effectively take on their main responsibilities and fulfill their governance duties such as project evaluation, selection, and monitoring [55]. In summary, the factors of GDPR, PPPUNIT, and PPPFUND may influence the scale of PPP investment, but do not influence the distribution of PPP investment across infrastructure sectors. Previous studies have mainly focused on the overall scale of PPP investment rather than its sub-sectoral structure. The differences in research findings, arising from variations in dependent variables, highlight the contribution of this study. By focusing on the distribution rather than the scale of PPP investment, this study reveals that the same factors can exert differing effects under distinct objectives.

5.2. Practical Implications

This study enriches the connotation of sustainable development from the perspective of public service provision and supports the strategic management of the PPP mode from the perspective of social sustainability. Social sustainability-oriented PPPs are referred to as people-first PPPs, and local residents’ public service requirements should receive more attention [18]. For PPPs in China, it is necessary to introduce PPP investment to municipal services, public education, and other priority infrastructure sectors [15]. However, the private sector may focus on high-profit infrastructure sectors rather than these priority ones [1,9,16,27]. In this process, three factors—the purchasing power of local residents, fiscal pressure, and PPP project experience—may significantly influence the distribution of PPP investment across infrastructure sectors (as reflected in the PPPSE value). These results can answer two questions: first, how to understand the effects of PPP in the context of social sustainability; second, how to consider regional conditions and project experience when initiating PPP projects.

First, although PPPs can promote socially sustainable development by improving the accessibility to infrastructure, they may also undermine socially sustainable development if they fail to align with public requirements. PPP investments that deviate from public requirements may result in infrastructure being located far away from residential communities [56]. For example, as mentioned above, the Yuzhong City Park PPP Project has also been widely disputed due to its being located on the urban outskirts, but the public spaces in the urban center remain insufficient [56]. The convenience of residents’ daily lives has not been improved. Therefore, it should make rational utilization of non-government capital introduced through the PPP mode, channeling it into necessary public service sectors, and leveraging the experience and technical advantages of private sectors to enhance the scientific planning of infrastructure, thereby better improving the living environment for residents [30]. In fact, for social sustainability, the PPPs should never neglect the people-first approach.

Second, there are two conditions for local governments to consider when adopting the PPP mode: the region’s fiscal pressure (which has a positive relationship with PPPSEs) and the purchasing power of local residents (which has a positive relationship with PPPSEs). When the government’s own financial resources are insufficient to provide public services, they can consider using PPPs to introduce non-governmental capital [36]. But, as mentioned above, non-governmental capital should be introduced into necessary public service sectors. Meanwhile, the purchasing power of local residents becomes important, as it determines the revenues of PPP projects, especially in the context of the PPP mode in China being revised to a user-pays franchise scheme in 2023 [55]. If local residents’ purchasing power is insufficient, PPP projects are difficult to implement [35,46]. Such is the case in Anqing—which has abundant tourism resources and where the purchasing power and travel demands of people are well-performed—where the Anqing New Energy Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure PPP Project operates smoothly due to guaranteed project returns [61]. Therefore, the government needs to comprehensively consider the necessity of projects driven by fiscal pressures and the feasibility of projects caused by the purchasing power of local residents, so as to launch PPP projects at an appropriate time and promote socially sustainable development. On the other hand, the government should avoid path dependence in PPP project selection (owing to the negative relationship between PPP project experience and PPPSEs). The lock-in effect of the simple mode damages PPPs’ development [32]. If the government continues to invest in familiar sectors, this will lead to overinvestment and bring potential government debts for the future [15]. Inside, project experience should be valued as the learning asset to improve the government’s capacity in regulating PPPs.

Although this study focused on China, the findings can also serve as a reference for other regions. On the one hand, this study indicates that it is necessary to focus not only on the scale of PPP investment or the adoption rate of PPPs, but also on the distribution of PPP investment across different infrastructure sectors. The issue of PPP investment being concentrated in a specific sector is also observed in other regions. For example, in India, over 80% of PPP investments were allocated to transport sectors as of March 2012 [6]. Similarly, in South East Queensland, over 70% of the infrastructure plan is allocated to specific sectors, such as roads [28]. From the perspective of social sustainability, regions need to examine whether the distribution of PPP investment aligns with the public requirements. The multi-criteria evaluation method for PPPSEs presented in Formula (1) can provide methodological guidance, but the weights assigned to public requirements need to be adjusted to align with regional conditions. On the other hand, globally, China has a large PPP market, with rich project experience and a relatively well-developed institutional system [36,37]. However, in many regions—such as India, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Malaysia—there are still many challenges in PPP regulation. Yang et al. [62] compared the differences in critical success factors of PPPs between China and these regions. The results indicated that transparent procurement, effective contract management, and good governance are lacking in regions outside China. These regions should place greater emphasis on treating project experience as a learning asset, drawing on such experiences to improve the government’s capacity in negotiating, operating, and supervising PPP projects.

6. Conclusions

This study found that, in China, PPPSEs exhibited significant regional and annual variations, and the purchasing power of local residents, fiscal pressure, and PPP project experience significantly influence the PPPSEs. These findings contribute to understanding the effects of PPPs in the context of social sustainability, and provide implications for the decision making of PPP development.

First, prior studies have mainly discussed the social sustainability of PPPs at the project level. However, this study focused on the regional level and used the sub-sectoral structure of PPP investment as the research object instead of the overall scale. This focus endows this study with a novel contribution by indicating that the distribution of PPP investment in infrastructure sectors may be inconsistent with public requirements. This study enhances a deeper understanding of how to utilize PPPs and non-governmental capital to improve public services under the social sustainability orientation. In the context of social sustainability, the PPPs should align with the people-first principle, and the non-governmental capital should be introduced into basic and necessary public service sectors. This provides valuable insights for various regions of the world facing the issue of PPP investment’s being concentrated in a specific sector.

Second, by examining a different dependent variable (PPP investment distribution in the context of social sustainability), this study also expands the understanding of the factors influencing PPP development. The same factor may exert different effects under different objectives, which helps to gain a more comprehensive understanding and make more effective use of these factors’ effects in regulating PPPs. For example, according to the findings in this study, the management of the PPP mode should align with local conditions, and efforts should be made to avoid inefficient and unbalanced investments.

In the future, more studies should be conducted to advance the social sustainability of PPPs. First, in evaluating PPPSEs, to better reflect the public requirements and align with socially sustainable development, the weights of public requirements should be adjusted to consider the characteristics of different regions or periods. Second, the attributes and behavioral characteristics of PPP participants—particularly the private sectors, which may engage in investment behaviors contrary to public requirements—should also be examined as influencing factors to promote sustainable development at a more micro level.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y.; methodology, S.Z.; software, L.Z.; validation, J.Y., Y.T., and M.J.S.; formal analysis, L.Z.; investigation, L.Z.; resources, J.Y.; data curation, L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.T. and S.Z.; visualization, L.Z.; supervision, S.Z.; project administration, S.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 72072031 and 72134002; and the Qinglan Project of Jiangsu Province of China.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The PPPSEs in China’s 28 provincial-level regions between 2017 and 2021.

Table A1.

The PPPSEs in China’s 28 provincial-level regions between 2017 and 2021.

| Regions | PPPSE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

| Beijing | 22.63 | 18.77 | 18.57 | 16.23 | 16.21 |

| Ningxia | 9.66 | 20.18 | 13.82 | 13.82 | 13.64 |

| Liaoning | 13.19 | 13.95 | 14.17 | 13.28 | 13.30 |

| Qinghai | 12.37 | 12.97 | 12.46 | 12.45 | 12.45 |

| Hunan | 11.03 | 11.30 | 12.13 | 13.13 | 12.20 |

| Jiangsu | 10.01 | 10.26 | 11.21 | 12.81 | 12.27 |

| Jiangxi | 9.42 | 8.16 | 9.86 | 12.04 | 13.12 |

| Shandong | 10.64 | 11.70 | 10.31 | 9.95 | 9.91 |

| Zhejiang | 16.92 | 10.40 | 11.78 | 6.37 | 6.69 |

| Fujian | 7.30 | 7.97 | 8.16 | 8.20 | 8.16 |

| Henan | 7.95 | 7.33 | 6.67 | 6.84 | 6.69 |

| Anhui | 4.14 | 7.71 | 8.66 | 6.64 | 6.32 |

| Chongqing | 2.82 | 8.62 | 8.38 | 8.13 | 5.34 |

| Xinjiang | 10.47 | 5.82 | 6.44 | 4.43 | 3.91 |

| Nei Mongol | 7.94 | 5.90 | 6.72 | 5.15 | 5.07 |

| Guizhou | 7.82 | 6.81 | 5.29 | 5.63 | 5.06 |

| Hebei | 7.02 | 6.39 | 5.49 | 5.60 | 5.61 |

| Hubei | 4.17 | 6.19 | 6.53 | 6.27 | 6.22 |

| Jilin | 7.86 | 2.20 | 5.26 | 5.39 | 5.59 |

| Heilongjiang | 7.31 | 7.53 | 2.98 | 2.71 | 1.73 |

| Hainan | 6.07 | 3.83 | 3.82 | 3.82 | 3.82 |

| Shanxi | 17.78 | 1.04 | 1.07 | 0.64 | 0.65 |

| Shaanxi | 5.05 | 4.51 | 4.05 | 3.84 | 3.13 |

| Guangxi | 9.32 | 4.36 | 2.36 | 1.40 | 1.59 |

| Guangdong | 5.84 | 3.23 | 2.77 | 3.20 | 3.04 |

| Gansu | 5.05 | 1.35 | 1.48 | 1.80 | 2.28 |

| Sichuan | 5.16 | 3.84 | 0.42 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Yunnan | 4.61 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 1.15 | 1.25 |

References

- Tariq, S.; Zhang, X. Critical Analysis of the Private Sector Roles in Water PPP Failures. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B.; Pena-Miguel, N. Analysing the link between corruption and PPPs in infrastructure projects: An empirical assessment in developing countries. J. Econ. Policy Reform 2022, 25, 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Besaiso, H.; Abualqumboz, M.; Cheng, X. Review of Studies on Sustainability of Public-Private Partnership Projects: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 1551–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Duan, K.; Wu, G.; Zhang, R.; Feng, X. Comprehensive metrological and content analysis of the public-private partnerships (PPPs) research field: A new bibliometric journey. Scientometrics 2020, 127, 2145–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, N.A.; Tharun, D.; Laishram, B. Infrastructure development through PPPs in India: Criteria for sustainability assessment. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2016, 59, 708–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinz, A.; Roudyani, N.; Thaler, J. Public-private partnerships as instruments to achieve sustainability-related objectives: The state of the art and a research agenda. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Y.; Shen, L.; Jiao, L.; Zuo, J.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Yan, H. Constraints to achieve infrastructure sustainability for mountainous townships in China. Habitat Int. 2018, 73, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizkorodov, E. Evaluating risk allocation and project impacts of sustainability-oriented water public-private partnerships in Southern California: A comparative case analysis. World Dev. 2021, 140, 105232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueskes, M.; Verhoest, K.; Block, T. Governing public-private partnerships for sustainability: An analysis of procurement and governance practices of PPP infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Cen, J.; Liu, B.; Qian, L.; Yuan, J. How Does Policy Implementation Affect the Sustainability of Public-Private Partnership Projects? A Stakeholder-Based Framework. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2022, 45, 1029–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ke, Y.; Sankaran, S. Achieving Social Sustainability in Public-Private Partnership Elderly Care Projects: A Chinese Case Study. Buildings 2025, 15, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, D.; Casady, C.B. The effects of contractual and relational governance on public-private partnership sustainability. Public Adm. 2024, 102, 1418–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourasia, A.S.; Dalei, N.N.; Jha, K. Evaluating public-private partnership role on the sustainability of airports in India. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 3595–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, L.; Tan, Y.; Skibniewski, M.J. Evaluating the regional social sustainability contribution of public-private partnerships in China: The development of an indicator system. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, J.F.M.; Enserink, B. Public-Private Partnerships in Urban Infrastructures: Reconciling private sector participation and sustainability. Public Adm. Rev. 2009, 69, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, S.; Zhang, X. Socioeconomic, Macroeconomic, and Sociopolitical Issues in Water PPP Failures. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Chen, B.; Wang, H.; Zhu, D. Public-private partnerships as a governance response to sustainable urbanization: Lessons from china. Habitat Int. 2020, 95, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Lam, P.T.I.; Chan, D.W.M.; Cheung, E.; Ke, Y. Critical Success Factors for PPPs in Infrastructure Developments: Chinese perspective. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, J.; Saz-Carranza, A. Determinants of public-private partnership policies. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 1171–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleta-Asin, J.; Munoz, F. Renewable energy public-private partnerships in developing countries: Determinants of private investment. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.J. Motivations, Obstacles, and Resources Determinants of Public-Private Partnership in State Toll Road Financing. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2014, 37, 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Ma, M. Public-private partnership as a tool for sustainable development—what literatures say? Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Liu, Y.; Hope, A.; Wang, J. Review of studies on the public private partnerships (PPP) for infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 773–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel Diaz-Sarachaga, J.; Jato-Espino, D.; Alsulami, B.; Castro-Fresno, D. Evaluation of existing sustainable infrastructure rating systems for their application in developing countries. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 71, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yu, Y.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.C.; Xu, J. Developing a project sustainability index for sustainable development in transnational public-private partnership projects. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 1034–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.C.; Chen, C.; Martek, I. Review of social responsibility factors for sustainable development in public-private partnerships. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 26, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthill, M. Strengthening the ‘Social’ in Sustainable Development: Developing a Conceptual Framework for Social Sustainability in a Rapid Urban Growth Region in Australia. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The Social Dimension of Sustainable Development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Su, L.; Kuinkel, M.S. Research status and trend of PPP in the US and China: Visual knowledge mapping analysis. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 3598–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, W.; Zhang, B.; Tiong, R.L.K. Official Tenure, Fiscal Capacity, and PPP Withdrawal of Local Governments: Evidence from china’s PPP project platform. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Ke, Y.; Lin, J.; Yang, Z.; Cai, J. Spatio-temporal dynamics of public private partnership projects in China. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Yang, Z.; Gao, H.; Tao, H.; Xu, M. Does PPP Matter to Sustainable Tourism Development? An Analysis of the Spatial Effect of the Tourism PPP Policy in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Zhao, J.Z. Explaining the adoption rate of public-private partnerships in Chinese provinces: A transaction cost perspective. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, J.; Moreira, A.C. The importance of non-financial determinants on public-private partnerships in Europe. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1563–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Del Barrio Álvarez, D.; Yuan, J.; Kato, H. Determinants of the formation process in public-private partnership projects in developing countries: Evidence from China. Local Gov. Stud. 2023, 50, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Qiang, W.; Liu, X. Exploring the geography of urban comprehensive development in mainland Chinese cities. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Development and Reform Commission. Effectively Implement Public Private Partnerships in Traditional Infrastructure Sectors. Available online: https://new.tzxm.gov.cn/zckd/jdhy/202001/t20200109_1262183.shtml (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Li, J.; Xiong, W.; Casady, C.B.; Liu, B.; Wang, F. Advancing Urban Sustainability through Public-Private Partnerships: Case study of the gu’an new industry city in china. J. Manag. Eng. 2023, 39, 05022016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razin, E.; Hazan, A.; Elron, O. The rise and fall (?) of public-private partnerships in Israel’s local government. Local Gov. Stud. 2022, 48, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Y. On the Development of Public-Private Partnerships in Transitional Economies: An explanatory framework. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Chen, H.; Zhou, G.; Kong, F. Determinants of Public-Private Partnership Adoption in Solid Waste Management in Rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleta-Asin, J.; Munoz, F. How does risk transference to private partner impact on public-private partnerships’ success? Empirical evidence from developing economies. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 72, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, W.; Song, J. The moderating role of governance environment on the relationship between risk allocation and private investment in PPP markets: Evidence from developing countries. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, D.; Zhu, D.; Quayson, M.; Hossin, M.A.; Omoruyi, O.; Bediako, A.K. A multicriteria decision framework for governance of PPP projects towards sustainable development. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 87, 101580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouton, J.; Sanogo, W.; Djomgoue, N. Risk allocation in energy infrastructure PPPs projects in selected African countries: Does institutional quality, PPPs experience and income level make a difference? Econ. Change Restruct. 2023, 56, 537–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, E.; Zhang, Z.; He, S.; Jiang, X.; Skitmore, M. Why Are PPP Projects Stagnating in China? An Evolutionary Analysis of China’s PPP Policies. Buildings 2024, 14, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Finance of Shandong Province. Shandong PPP Governance Unit. Available online: http://czt.shandong.gov.cn/art/2017/9/18/art_10601_3430368.html (accessed on 16 October 2023).

- Department of Finance of Henan Province. Hena PPP Governace Unit. Available online: https://czt.henan.gov.cn/2020/11-30/1911878.html (accessed on 16 October 2023).

- Chan, D.W.M.; Sarvari, H.; Husein, A.A.J.A.; Awadh, K.M.; Golestanizadeh, M.; Cristofaro, M. Barriers to Attracting Private Sector Investment in Public Road Infrastructure Projects in the Developing Country of Iran. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zhang, T. Effect of private capital in rival projects on public-private partnership adoption in China. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2023, 30, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Zhao, J.Z. The Rise of Public-Private Partnerships in China: An effective financing approach for infrastructure investment? Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 79, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayides, P.M.; Parola, F.; Lam, J.S.L. The effect of institutional factors on public-private partnership success in ports. Transp. Res. Part A Poilicy Pract. 2015, 71, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Zhong, N.; Wang, F.; Zhang, M.; Chen, B. Political opportunism and transaction costs in contractual choice of public-private partnerships. Public Adm. 2022, 100, 1125–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Development and Reform Commission; Ministry of Finance. Guiding Opinions on Standardizing the Implementation of a New Mechanism for Public Private Partnerships. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/2023/issue_10826/202311/content_6915818.html (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Wang, J. Focusing on the City Park PPP Project in Yuzhong. Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_24058410 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Mu, R.; de Jong, M.; Koppenjan, J. The rise and fall of Public-Private Partnerships in China: A path-dependent approach. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 794–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. From State to Market: Private Participation in China’s Urban Infrastructure Sectors, 1992-2008. World Dev. 2014, 64, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y. The assisting hand’ or ‘the grabbing hand’: Experimental evidence from PPP investments in the implementation of official rotation systems. J. Chin. Gov. 2025, 10, 218–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopanska, A.; Asinski, R. Fiscal and political determinants of local government involvement in public-private partnership (PPP). Local Gov. Stud. 2019, 45, 957–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Cui, N.; Xue, S.; Du, Q. The impacts of whole life cycle project management on the sustainable development goals. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Thuc, L.D.; Kim, S.Y. Critical Success Factors of Public-Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects from a Middle-Income Country: A Comparison with Countries in Asia. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 05024023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).