Impact of Multiple Environmental Factors of Space Clusters for Informal Learning in Library Renovation and Update

Abstract

1. Introduction

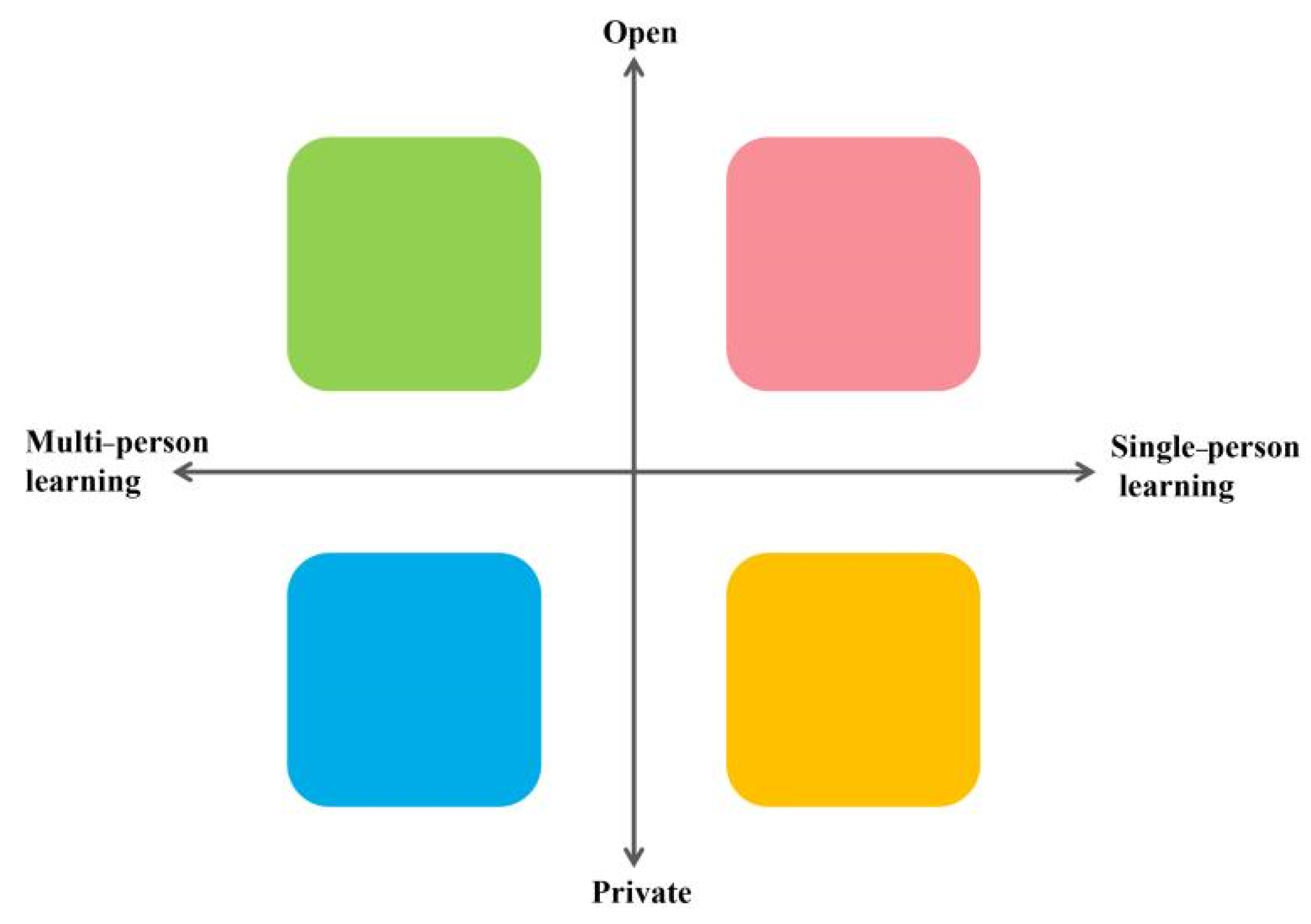

2. Literature Review

3. Research Methodology

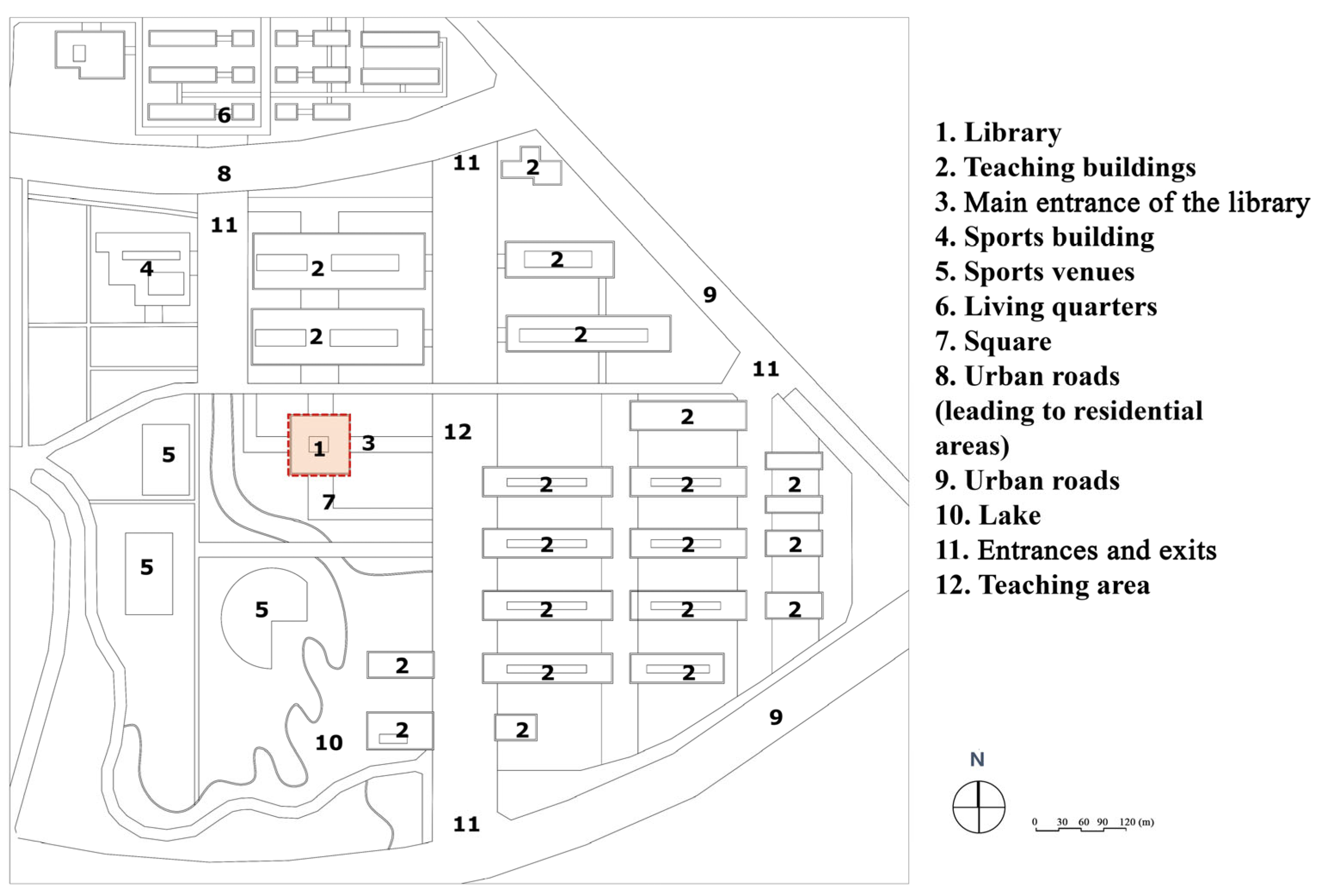

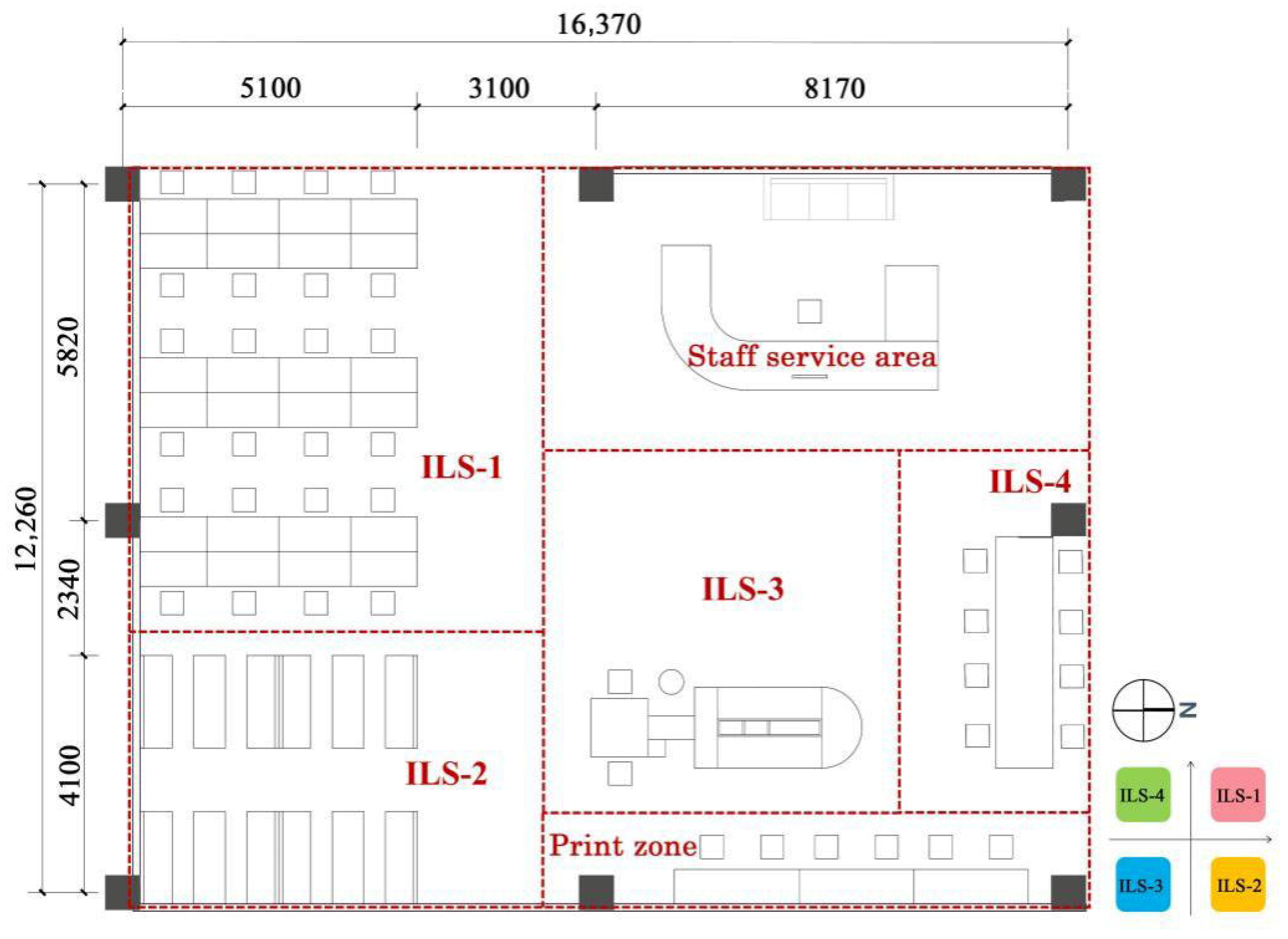

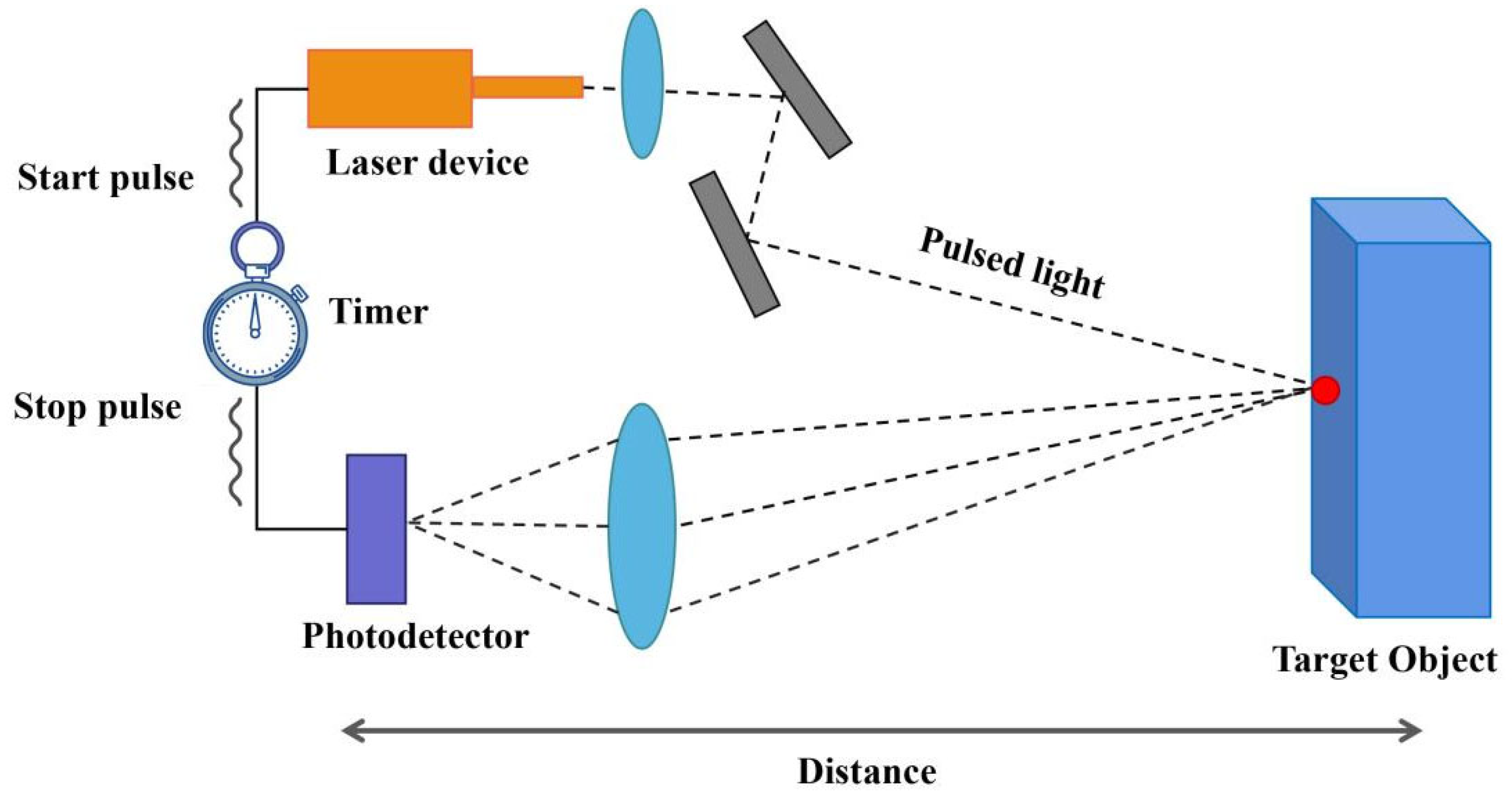

3.1. Research Subjects

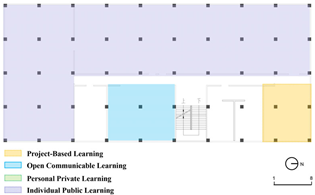

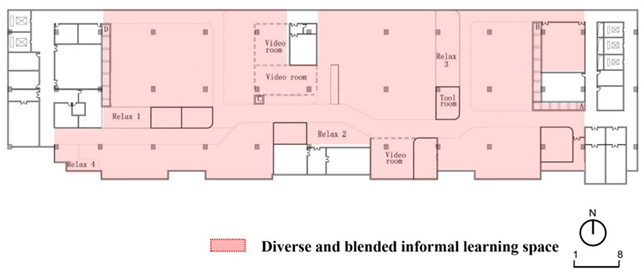

3.1.1. Case Study

3.1.2. Introduction of Research Subjects

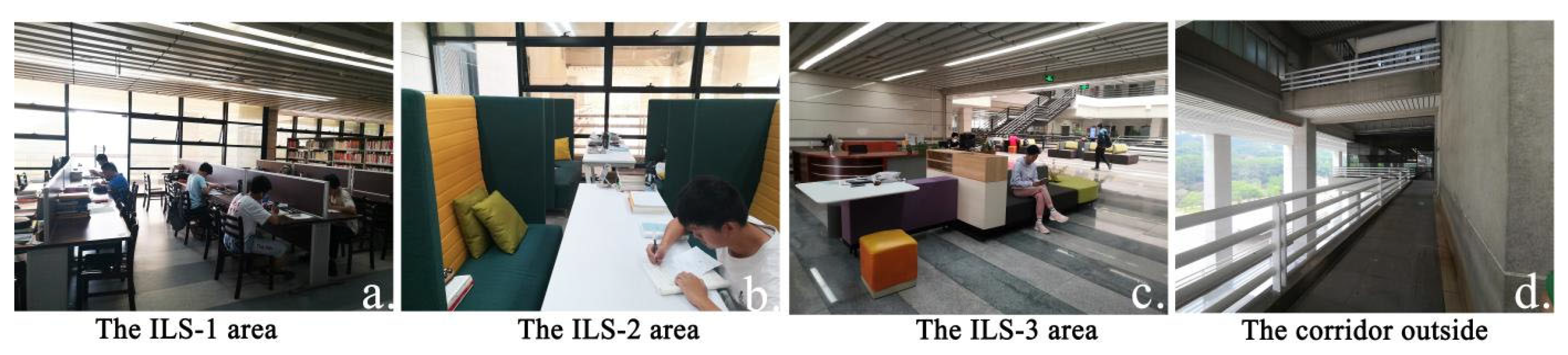

3.2. Selection of Positioning Technology

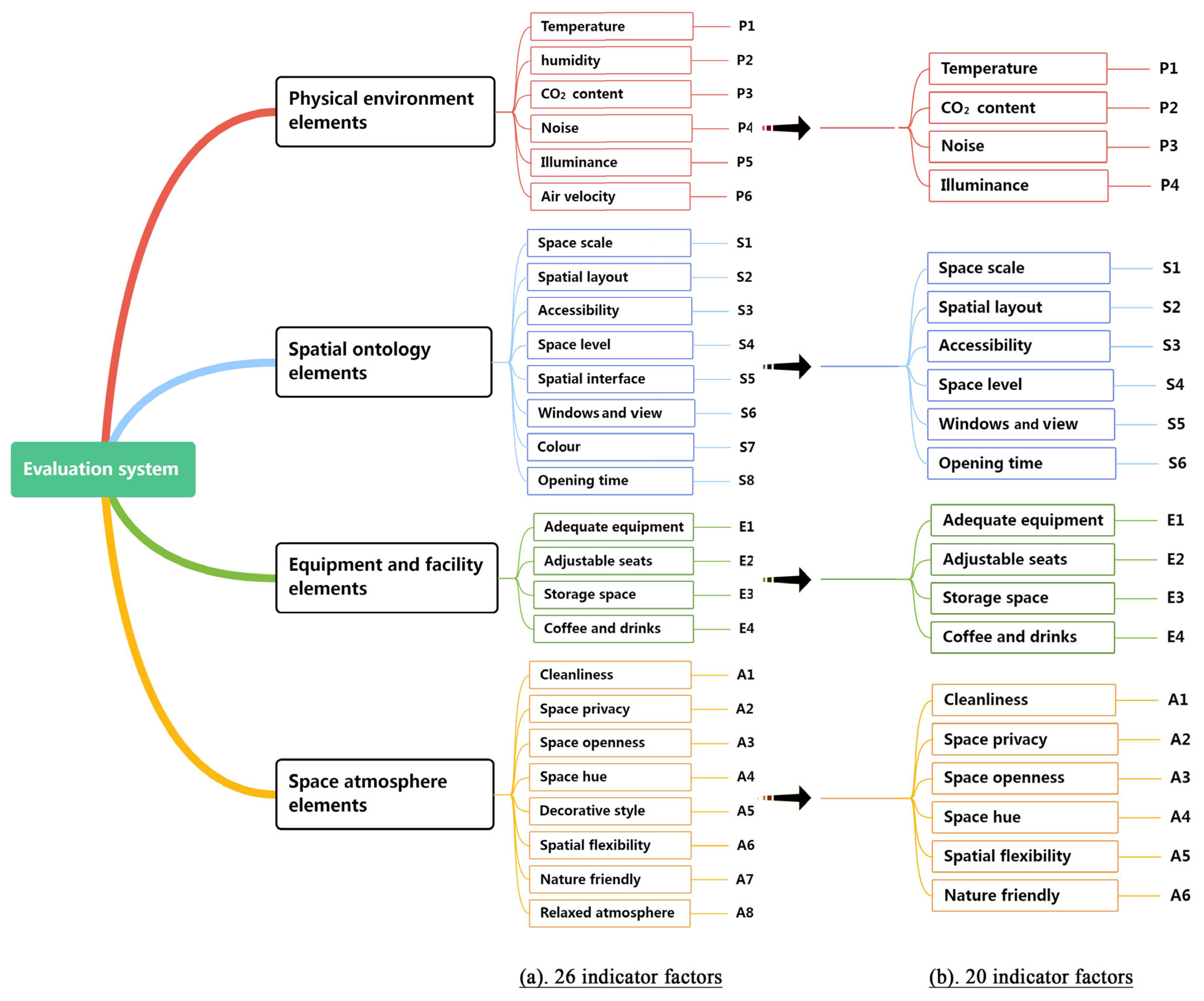

3.3. Preliminary Establishment of Evaluation System

3.4. Weight Calculation of Indicators

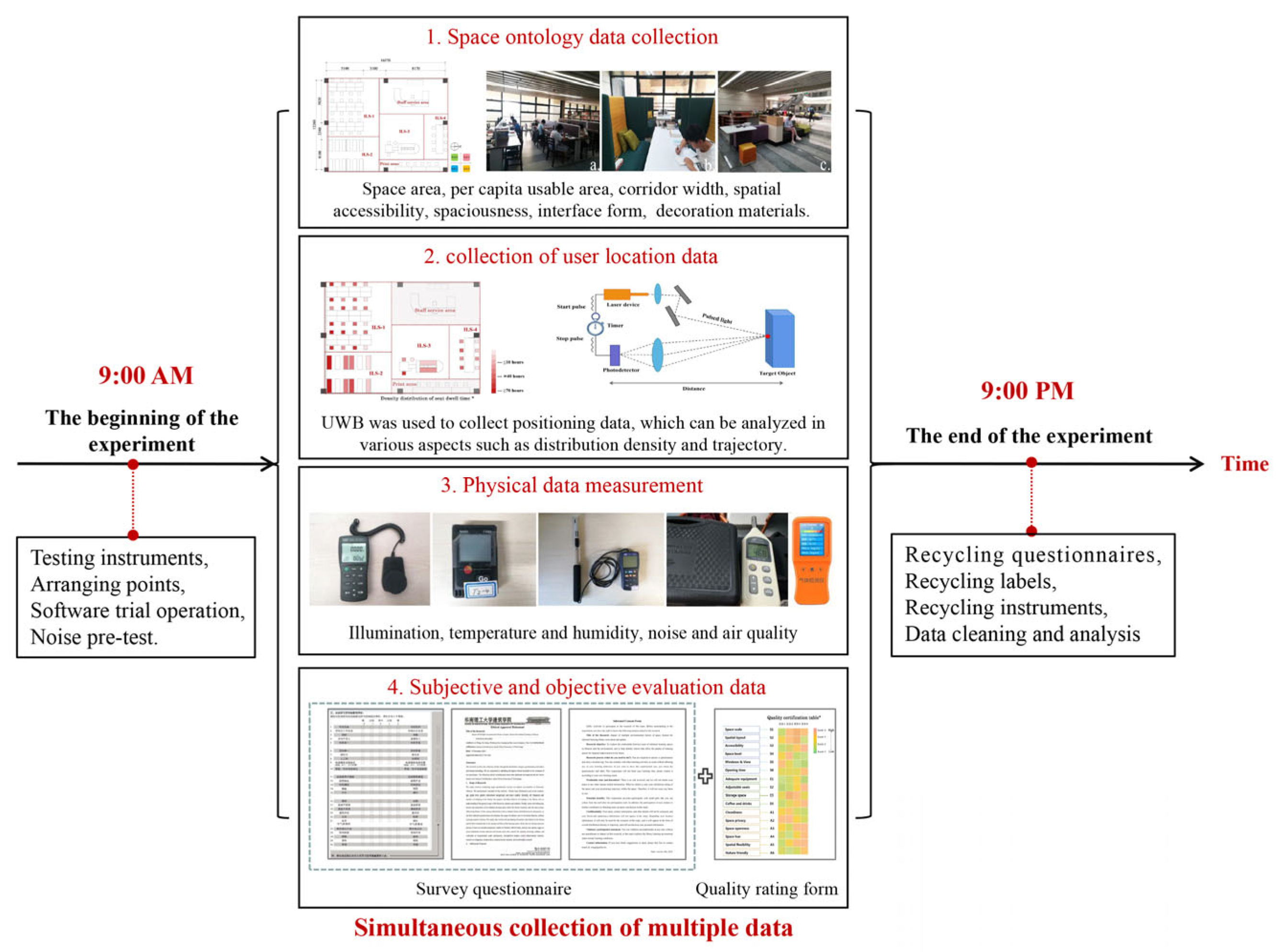

3.5. Specific Implementation of the Experiment

3.6. Collection of Objective and Subjective Data

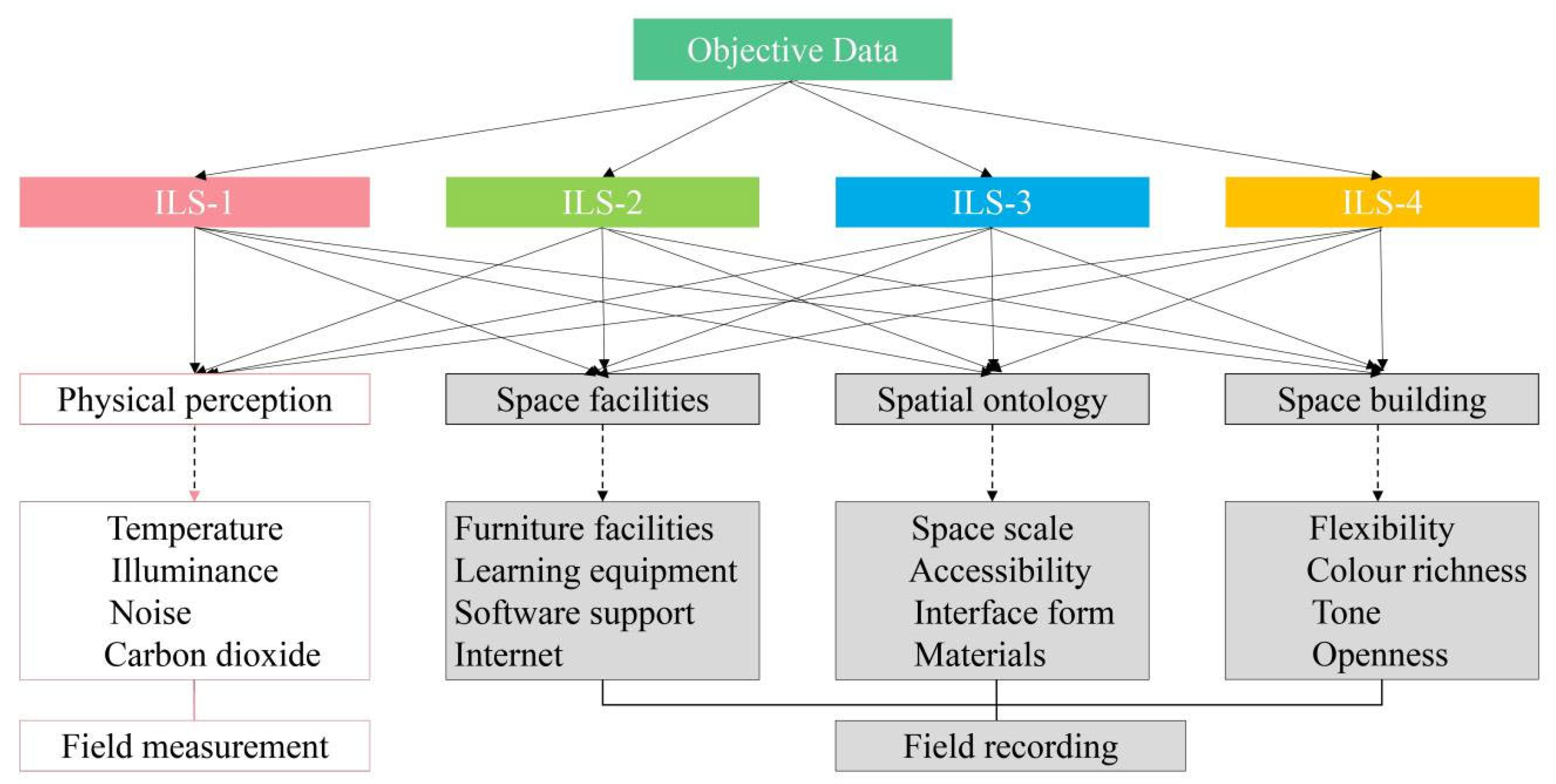

3.6.1. Measurement of Physical Environment Data

3.6.2. Collection of Other Objective Data

3.6.3. Collection of Subjective Data

4. Results

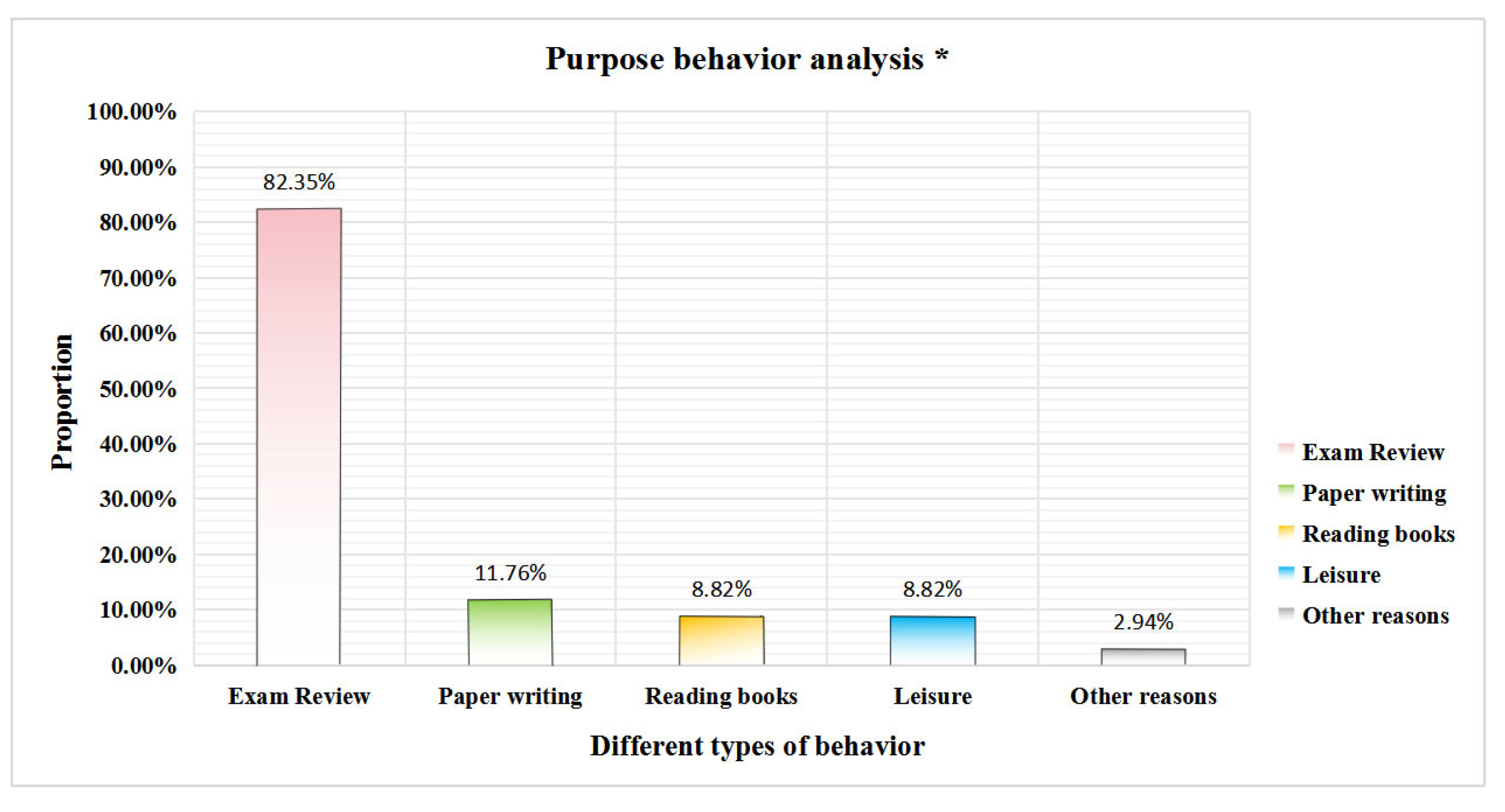

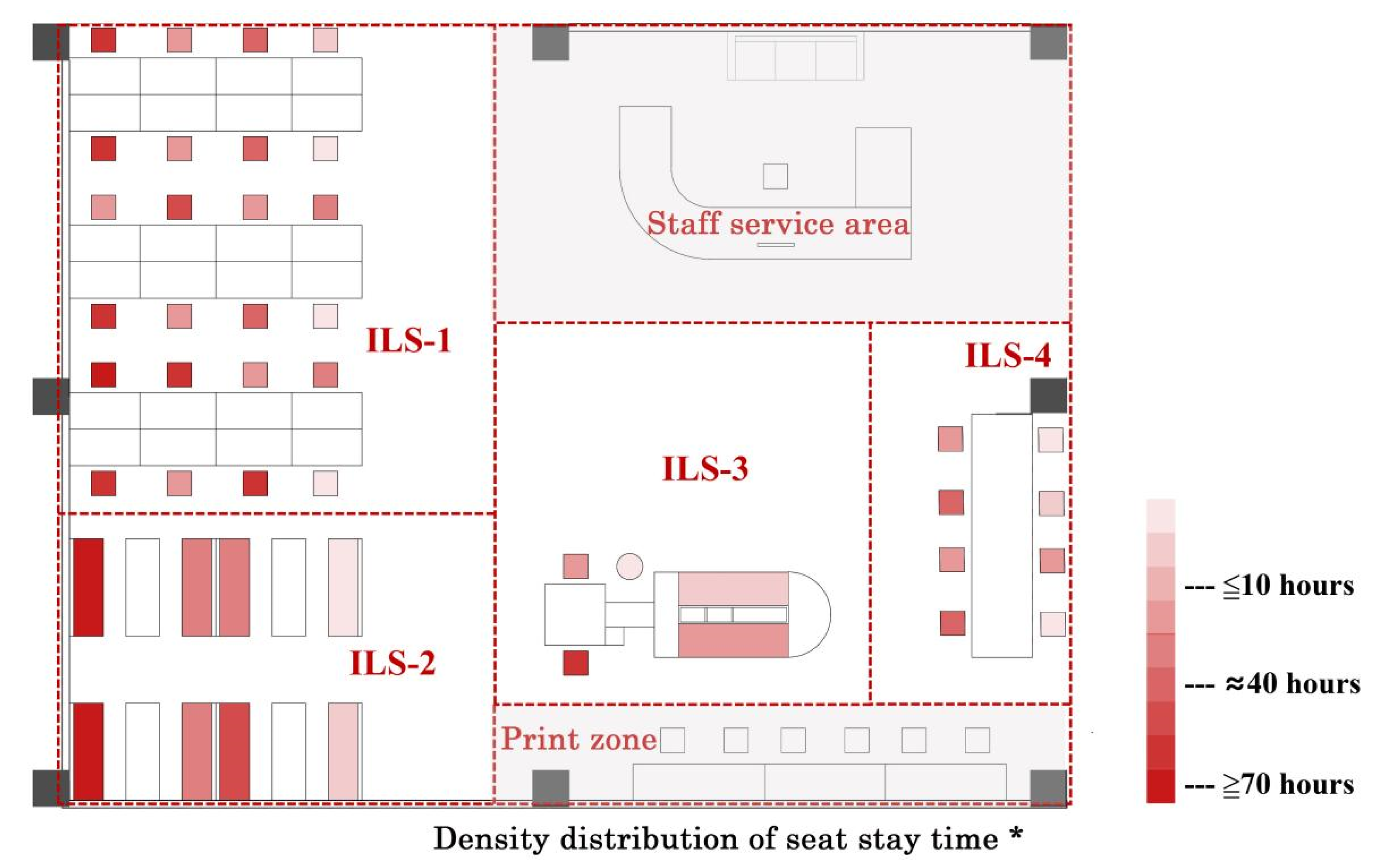

4.1. User Attributes and Learning Behaviour

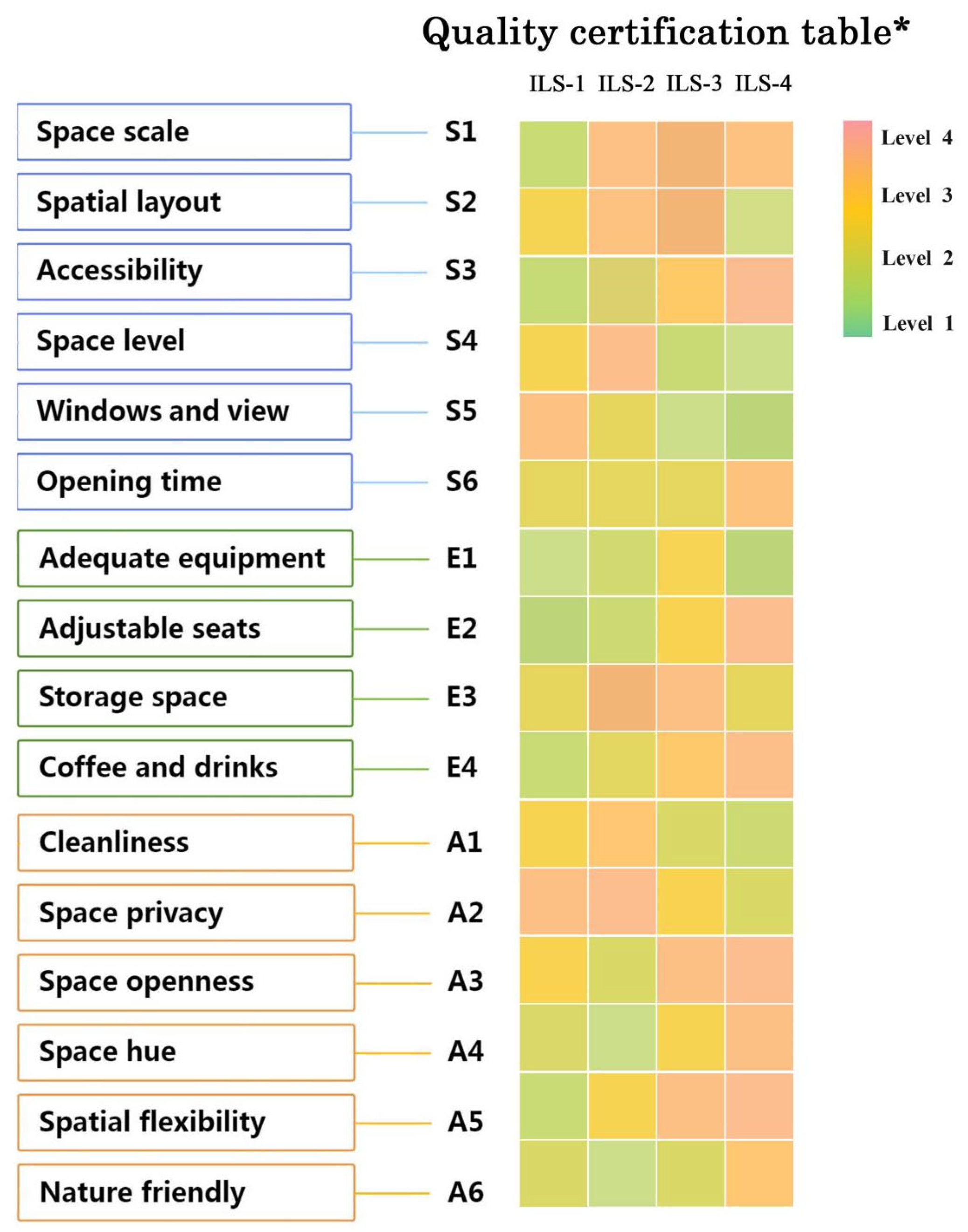

4.2. Subjective Evaluation Results

4.3. Performance of Physical Data

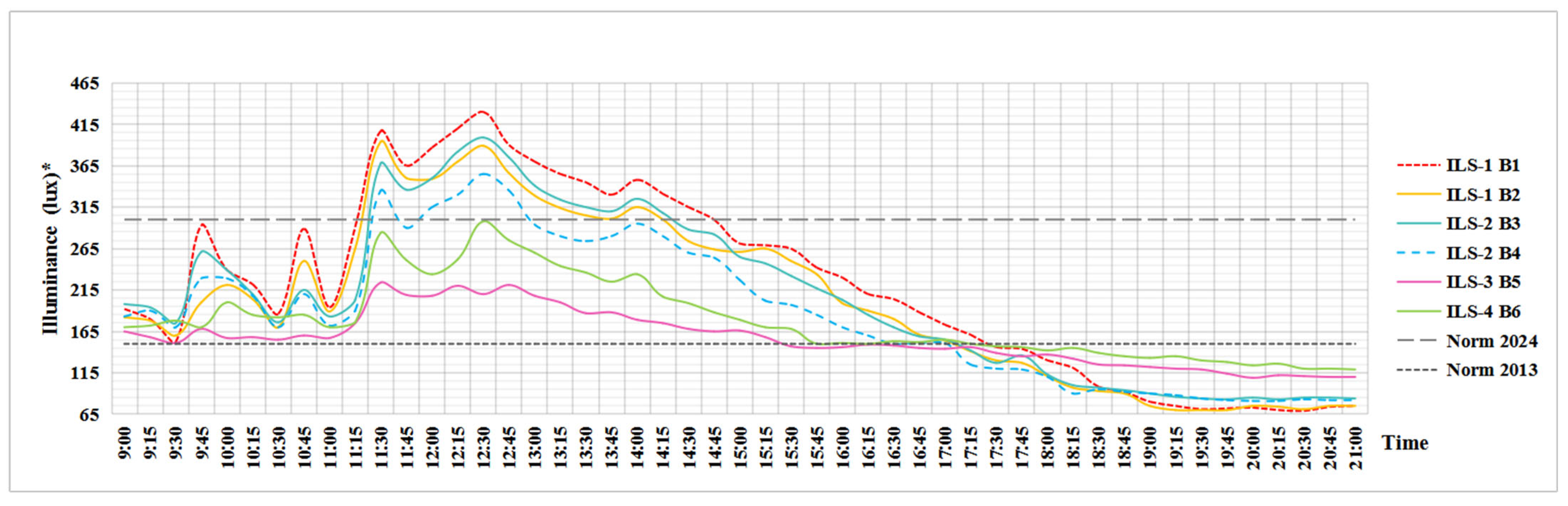

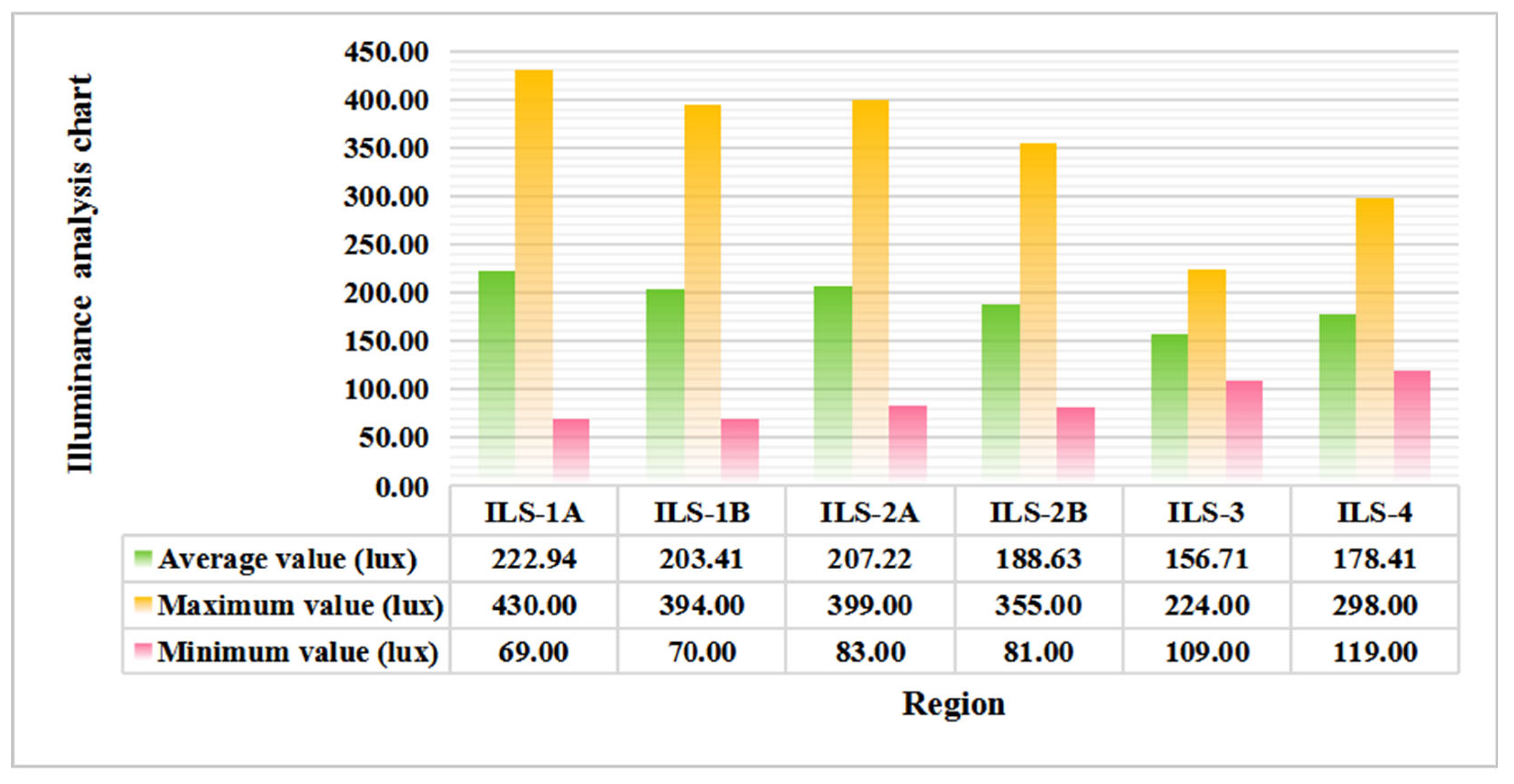

4.3.1. Illuminance

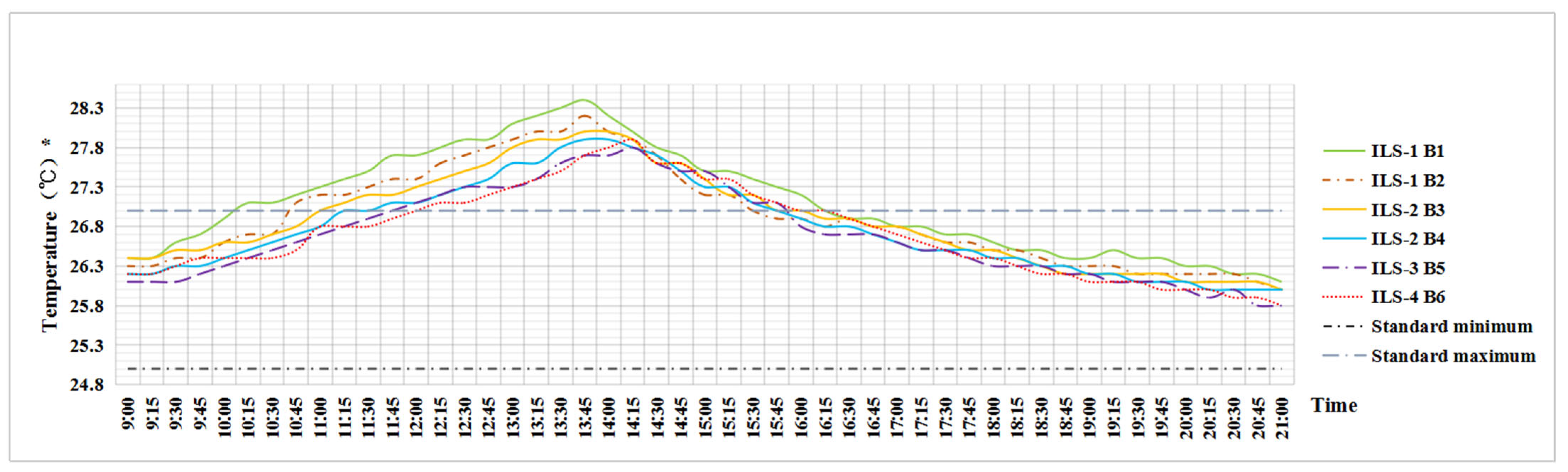

4.3.2. Temperature

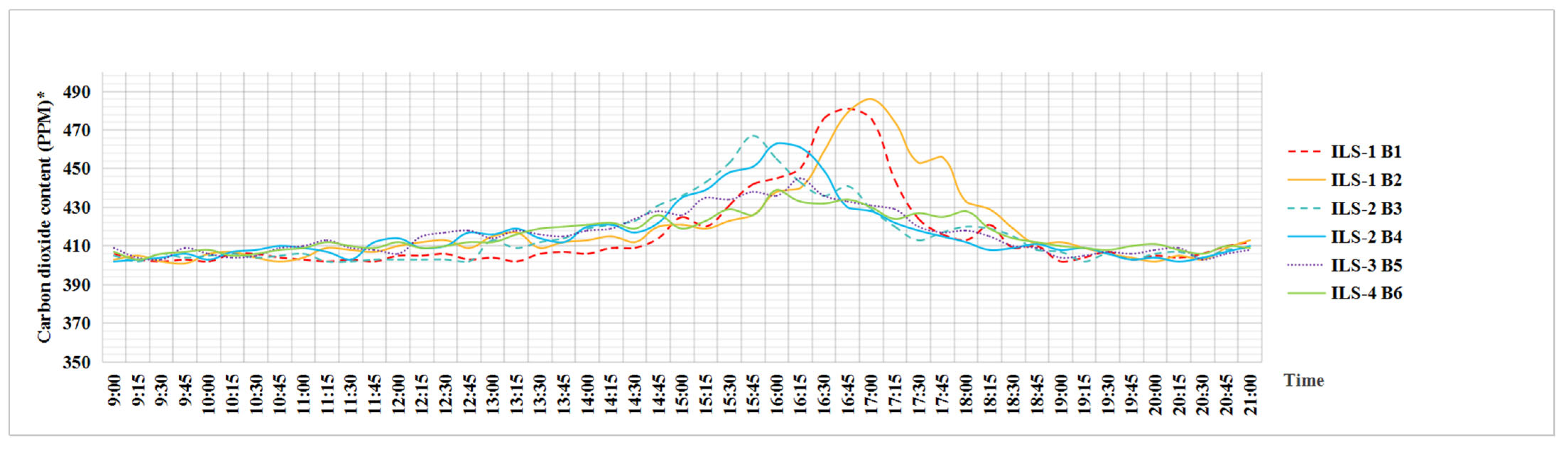

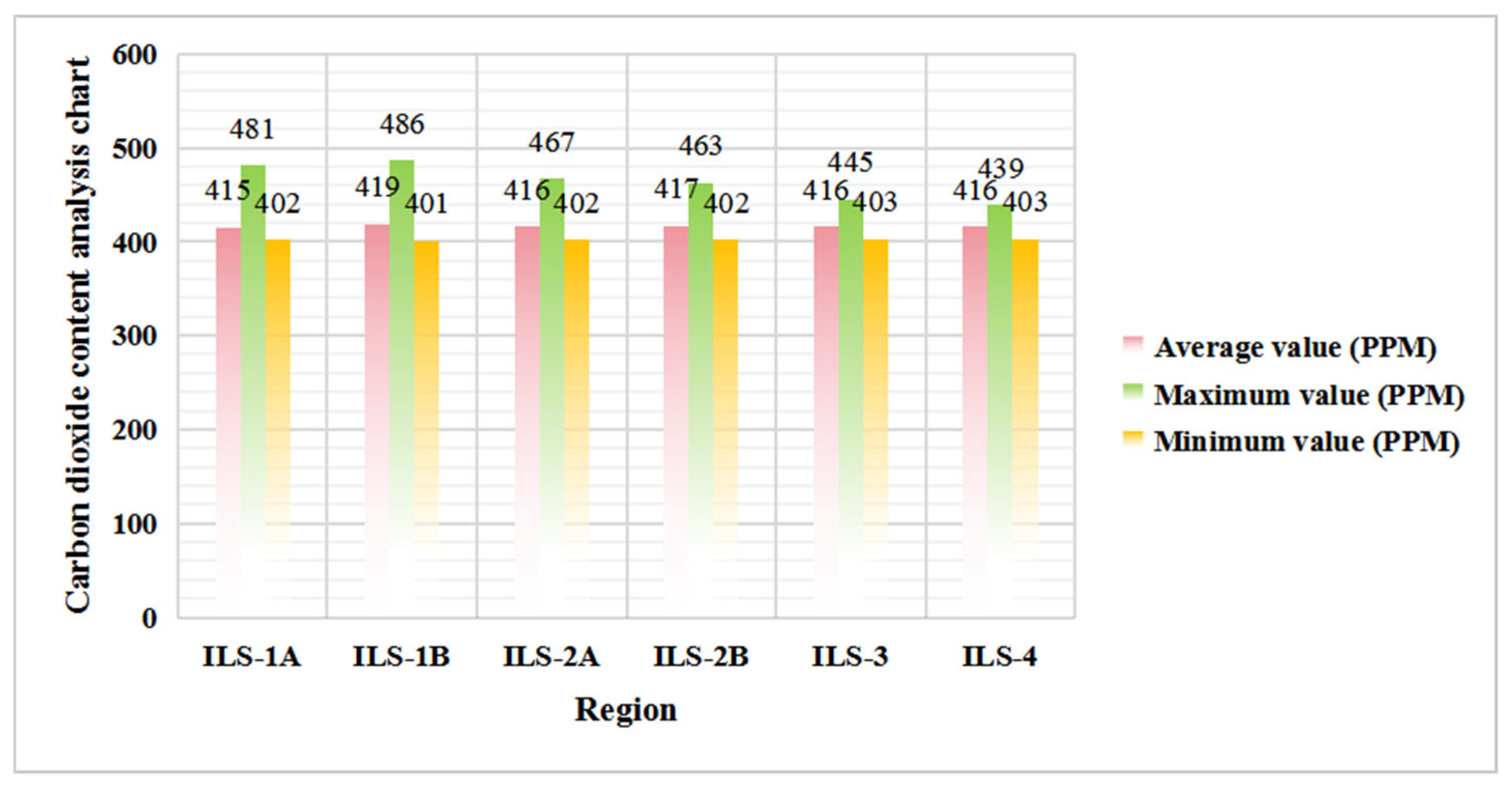

4.3.3. Carbon Dioxide Content

4.3.4. Noise

4.4. Performance of Other Objective Data

4.5. Results of Weight Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Relationship Between User Attributes and Selection Preferences

5.2. Correlation Between Physical Environment and Preferences

5.3. Exploration of Subjective and Objective Evaluation Results

5.4. Exploration of Key Factor Weights

5.5. Research Limitations

6. Conclusions

6.1. Main Conclusion

6.2. Optimisation Strategy

6.3. Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

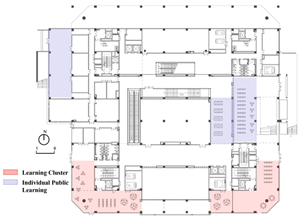

| 1. Group Embedded Library (17 Libraries) | |||

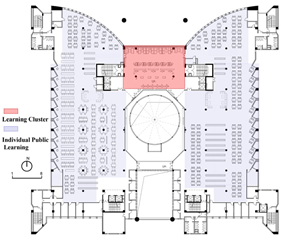

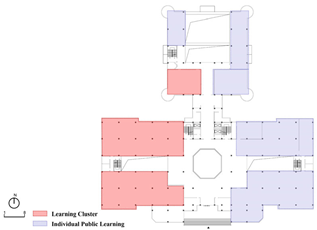

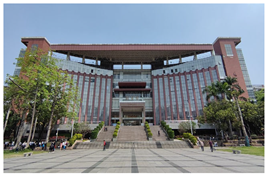

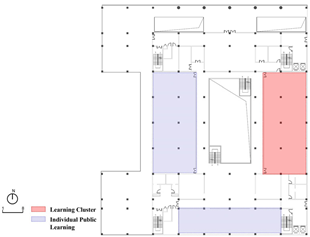

| Abbreviation for University Library | Representative floor plan | Photo of library | The area, number of users, characteristics, and floor of the learning cluster. |

| ZDDXQ-L (Renovated) |  |  | From the third to the fifth floor, 490 m2, 164 users. A typical learning cluster module located on the north side of the atrium, which included various learning methods such as exhibitions, individual learning, and group discussions. |

| GDDXC-L (Renovated) |  |  | From the third to the fifth floor, 576 m2, 136 users. The coffee learning cluster located on the north side of the atrium included coffee sales functions, as well as various learning methods. |

| GKDGZ-L (Renovated) |  |  | From the second to the fifth floor, 300 m2, 140 users. Fully utilising the space around spiral staircase, creating learning cluster with various ILS. |

| ZDNXQ-L (Renovated) |  |  | First floor, 192 m2, 45 users. On one side of the courtyard, a discussion and learning space that was close to nature has been created, fully utilising the green scenery of the courtyard. |

| HSSP-L (Renovated) |  |  | First floor, third floor, and sixth floor. 700 m2, 625 m2 and 208 m2. 125, 80, and 40 users. The latest renovation has added innovative learning spaces to meet the diverse learning needs of users. |

| HSPY-L (Renovated) |  |  | The top floor. 770 m2, 260 users. A mixed learning space for coffee learning has been set up between two traditional reading rooms. |

| JDSP-L (Renovated) |  |  | First floor, the top floor. 980 m2, 240 users. A smart learning space has been set up on the west side of the entrance hall, which included various ILS and advanced equipment and facilities. |

| GMD-L (Renovated) |  |  | Second, third, and fourth floors. 456 m2, 120 users. In 2023, multiple learning clusters were renovated, including four types of ILS, to fully meet the learning needs of students. |

| GZCLO-L (Renovated) |  |  | First floor, 178 m2, 80 users. A mixed learning area has been set up using the lobby space of the entrance hall, which could also be used as an exhibition or small lecture hall. |

| GZCLN-L (Renovated) |  |  | Third floor, 215 m2, 24 users. On the west side was a learning cluster that includes coffee sales, and on the east side was a learning cluster that includes art exhibition functions. |

| HN-L (Renovated) |  |  | First floor, 490 m2, 145 users. Although the library has a relatively small area, it still utilised the first floor space to create a learning cluster and also served as an exhibition venue. |

| HGWS-L (Renovated) |  |  | Second, third, and fourth floors. 317 m2, 66 users. A learning cluster has been created in the hub area between the east and west sides, which has been well received by a large number of students. |

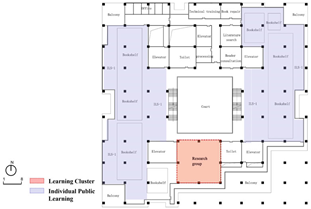

| GDUT-L (Renovated) |  |  | Third, fourth, and fifth floors. 200 m2, 68 users. There were 7 learning clusters with different themes, and this paper explored one of them. |

| HGGJ-L (New library) |  |  | Second floors. 245 m2, 50 users. The design concept of the library was a “knowledge valley”, which utilised the middle “valley” space to create a learning cluster. |

| GGLD-L (Renovated) |  |  | First floors. S1 = 115 m2, 16 users. S2 = 280 m2, 45 users. By utilising the buffer space on the first floor of the atrium and the secondary entrance, a diverse, free, and mixed learning cluster has been created. |

| JDPY-L (Renovated) |  |  | Second floors. 256 m2, 40 users. Utilised the hub areas of transportation on both sides to create learning clusters with various informal learning options. |

| 2. Independent and Separate Library (Two Libraries) | |||

| Abbreviation for University Library | Representative floor plan | Photo of library | The area, number of users, characteristics, and floor of the ILS. |

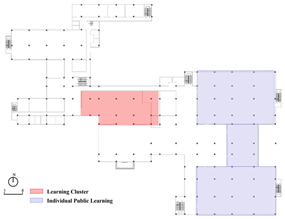

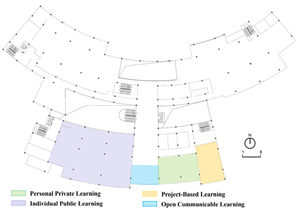

| HGDXC-L (Unrenovated Library) |  |  | ILS1 = 940 m2, 200 users. ILS2 = 250 m2, 50 users. ILS3 = 203 m2, 40 users. ILS4 = 145 m2, 25 users. Third to sixth floors. Four different types of ILS existed independently with partitions between them. |

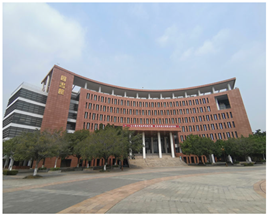

| GDGHG-L (Unrenovated Library) |  |  | ILS1 = 140 m2 and 360 m2, 90 users and 200 users. ILS2 = 61 m2, 16 users. ILS4 = 86 m2, 24 users. The first floor consisted of ILS1 and ILS2, located in two separate rooms. The second floor consisted of ILS4 and ILS1, which were also independently configured. |

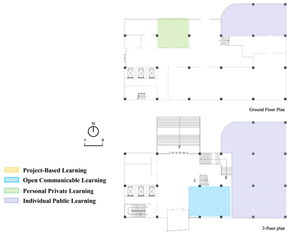

| GMCG-L (Renovated) |  |  | Second floor. ILS1 = 792 m2, 80users. ILS3 = 108 m2, 15 users. ILS4 = 72 m2, 15 users. Partition informal learning spaces through different rooms. |

| 3. Borderless Library (One Libraries) | |||

| Abbreviation for University Library | Representative floor plan | Photo of library | The area, number of users, characteristics, and floor of the ILS. |

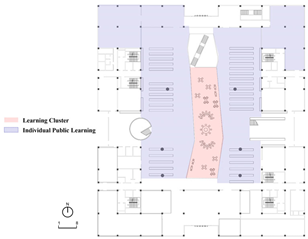

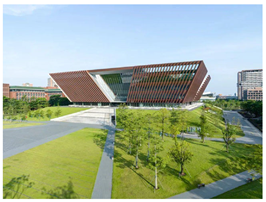

| GKG-SC (New library) |  |  | ILS = 2300 m2, 360 users. fourth to sixth floors. An academic and creative centre that served as a library in the school and the place where students spent the longest time in their daily studies. All informal learning was mixed together. |

References

- Long, P.; Oblinger, D.G. Trends in learning space design. Learn. Spaces 2006, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Guo, W.; Caneparo, L.; Wan, G.; Liu, X.; Xue, Y. Research on the design of Informal Learning Space (ILS) in universities in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area—A survey on the Guangzhou Campus of HKUST. In Proceedings of the Forum on the Fate and Development of Cities in the Guangdong Hong Kong Macao Greater Bay Area, Macau, China, 18 May 2024; pp. 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, P.A.; Stallings, L.; Pierce, R.L.; Largent, D. Classroom Interaction Redefined: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Moving beyond Traditional Classroom Spaces to Promote Student Engagement. J. Learn. Spaces 2018, 7, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Karasic, V.M. From commons to classroom: The evolution of learning spaces in academic libraries. J. Learn. Spaces 2016, 5, 601384. [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Webber, L. Informal learning places–Oft forgotten yet important places for student learning: Time for a design rethink!”. Des. Community Theme Rep. 2015, 2, 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dokmeci Yorukoglu, P.N.; Kang, J. Analysing sound environment and architectural characteristics of libraries through indoor soundscape framework. Arch. Acoust. 2016, 41, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, M. How do makerspaces communicate who belongs? Examining gender inclusion through the analysis of user journey maps in a makerspace. J. Learn. Spaces 2020, 9, 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Baden, M. Using problem-based learning: New constellations for the 21st century. J. Excell. Coll. Teach. 2014, 25, 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Quay, J. Experience and participation: Relating theories of learning. J. Exp. Educ. 2003, 26, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Zou, Y.; Dong, W.; Zhou, X. Optimal Design and Verification of Informal Learning Spaces (ILS) in Chinese Universities Based on Visual Perception Analysis. Buildings 2022, 12, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenburger, E. Rural High School Libraries: Places Prone to Promote Positive School Climates. J. Learn. Spaces 2021, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Elrod, R. “I Didn’t Realize That I Needed Books That Often”: Demonstrating Library Value during the Temporary Closure of an Academic Branch Library. J. Learn. Spaces 2019, 8, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B.; Masrabaye, F.; Guiradoumngué, G.M.; Zheng, J.; Liu, L. Progress in research on sustainable urban renewal since 2000: Library and visual analyses. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrico, S.; Lindell, A. A Post-Occupancy Look at Library Building Renovations: Meeting the Needs of the Twenty-First Century Users. In Meeting the Needs of Student Users in Academic Libraries; Chandos Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 37–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Kou, Z.; Oldfield, P.; Heath, T.; Borsi, K. Informal learning spaces in higher education: Student preferences and activities. Buildings 2021, 11, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatlin, A.R.; Kuhn, W.; Boyd, D.; Doukopoulos, L.; McCall, C.P. Successful at scale: 500 faculty, 39 classrooms, 6 years: A case study. J. Learn. Spaces 2021, 10, 601441. [Google Scholar]

- Fouad, A.T.Z.; Sailer, K.E.R.S.T.I.N. The design of school buildings. Potentiality of informal learning spaces for self-directed learning. In Proceedings of the 12th International Space Syntax Symposium, Beijing, China, 9–11 July 2019; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.T.; Huang, W.P.; Lin, T.P.; Hwang, R.L. Implementation of green building specification credits for better thermal conditions in naturally ventilated school buildings. Build. Environ. 2015, 86, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, T. Identification of representative pollutants in multiple locations of an Italian school using solid phase micro extraction technique. Build. Environ. 2014, 82, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braat-Eggen, E.; Reinten, J.; Hornikx, M.; Kohlrausch, A. The influence of background speech on a writing task in an open-plan study environment. Build. Environ. 2020, 169, 106586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P.; Davies, F.; Zhang, Y.; Barrett, L. The impact of classroom design on pupils’ learning: Final results of a holistic, multi-level analysis. Build. Environ. 2015, 89, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhafaji, A.S.; Fallahkhair, S. Smart ambient: Development of mobile location based system to support informal learning in the cultural heritage domain. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 14th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, Athens, Greece, 7–10 July 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, S.; Xu, H.; Kang, J. Effects of implanted wood components on environmental restorative quality of indoor informal learning spaces in college. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.K. John Dewey in the 21st century. J. Inq. Action Educ. 2017, 9, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, P. Malcolm S Knowles. In Twentieth Century Thinkers in Adult & Continuing Education; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2001; pp. 144–159. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council; Board on Behavioral; Sensory Sciences; Committee on Developments in the Science of Learning with Additional Material from the Committee on Learning Research & Educational Practice. How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, D.; Mitchell, P. The Cube and the Poppy Flower: Participatory Approaches for Designing Technology-Enhanced Learning Spaces. J. Learn. Spaces 2017, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Informal and Incidental Learning in the New Update on Adult Learning Theory; Jossey-Boss: San Francisco, DC, USA, 2001; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Basdogan, M.; Morrone, A.S. Coffeehouse as classroom: Examining a flexible and active learning space from the pedagogy-space-technology-user perspective. J. Learn. Spaces 2021, 10, 601454. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, G.; Matthews, G. (Eds.) Exploring Informal Learning Space in the University: A Collaborative Approach; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guinther, L.L.; Carll-White, A. Utilizing Emergency Departments as Learning Spaces through a Post-Occupancy Evaluation. J. Learn. Spaces 2014, 3, 601364. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, G.; Matthews, G. Evaluating university’s informal learning spaces: Role of the university library? New Rev. Acad. Librariansh. 2013, 19, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeren, E. Gender differences in formal, non-formal and informal adult learning. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2011, 33, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beil, K.; Hanes, D. The influence of urban natural and built environments on physiological and psychological measures of stress—A pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 1250–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, S.A.; Chyung, S.Y. Factors that influence informal learning in the workplace. J. Workplace Learn. 2008, 20, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, D.W. Exploring the icebergs of adult learning: Findings of the first canadian survey of informal learning practices. Can. J. Study Adult Educ. 1999, 13, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.S.; Thang, S.M.; Noor, N.M. The usage of social networking sites for informal learning: A comparative study between Malaysia students of different gender and age group. Int. J. Comput.-Assist. Lang. Learn. Teach. (IJCALLT) 2018, 8, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrop, D.; Turpin, B. A study exploring learners’ informal learning space behaviors, attitudes, and preferences. New Rev. Acad. Librariansh. 2013, 19, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taib, N. The Effects of Ornamental Plants and Users’ Perception on Thermal Comfort in Landscape Gardens of a High-rise Office Building. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Mino, L. A study on student perceptions of higher education classrooms: Impact of classroom attributes on student satisfaction and performance. Build. Environ. 2013, 70, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, M.; Toyinbo, O.; Putus, T.; Nevalainen, A.; Shaughnessy, R.; Haverinen-Shaughnessy, U. Indoor environmental quality in school buildings, and the health and wellbeing of students. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2014, 217, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, D.A.; Greeves, R.; Saxby, B.K. The effect of low ventilation rates on the cognitive function of a primary school class. Int. J. Vent. 2007, 6, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Q.; Qiu, J.; Liu, Y. Occupants’ thermal comfort and perceived air quality in natural ventilated classrooms during cold days. Build. Environ. 2019, 158, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.H.; Wu, F.; Su, B. Impacts of library space on learning satisfaction—An empirical study of university library design in Guangzhou, China. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2018, 44, 724–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.R.; Ahlers, S.T.; House, J.F.; Schrot, J. Repeated exposure to moderate cold impairs matching-to-sample performance. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 1989, 60, 1063–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Wang, L.; Caneparo, L. Research on the Factors That Influence and Improve the Quality of Informal Learning Spaces (ILS) in University Campus. Buildings 2024, 14, 3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramu, V.; Taib, N.; Massoomeh, H.M. Informal academic learning space preferences of tertiary education learners. J. Facil. Manag. 2022, 20, 679–695. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K. Mapping diaries, or where do they go all day. In Studying Students: The Undergraduate Research Project at the University of Rochester; Association of College and Research Libraries: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, K.; Newton, C. Transforming the twenty-first-century campus to enhance the net-generation student learning experience: Using evidence-based design to determine what works and why in virtual/physical teaching spaces. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2014, 33, 903–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldock, J.; Rowlett, P.; Cornock, C.; Robinson, M.; Bartholomew, H. The role of informal learning spaces in enhancing student engagement with mathematical sciences. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 48, 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Lin, H.; Liu, X.; Guo, W.; Yao, J.; He, B.-J. An Assessment of the Psychologically Restorative Effects of the Environmental Characteristics of University Common Spaces. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 110, 107645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, E.; Brown, M. The case for a learning space performance rating system. J. Learn. Spaces 2011, 1, 601341. [Google Scholar]

- da Graça, V.A.C.; Kowaltowski, D.C.C.K.; Petreche, J.R.D. An evaluation method for school building design at the preliminary phase with optimisation of aspects of environmental comfort for the school system of the State São Paulo in Brazil. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 984–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.J.; Hong, S.M.; Mumovic, D.; Taylor, I. Using a unified school database to understand the effect of new school buildings on school performance in England. Intell. Build. Int. 2015, 7, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Hong, S.; Yang, E. Perceived Productivity in Open-Plan Design Library: Exploring Students’ Behaviors and Perceptions. J. Learn. Spaces 2021, 10, 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Nordquist, T.; Norback, D. The prevalence and incidence of sick building syndrome in Chinese pupils in relation to the school environment: A two-year follow-up study. Indoor Air 2011, 21, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLane, Y.; Dawkins, J. Building of Requirement: Liberating Academic Interior Architecture. J. Learn. Spaces 2014, 3, 601365. [Google Scholar]

- Morieson, L.; Murray, G.; Wilson, R.; Clarke, B.; Lukas, K. Belonging in space: Informal learning spaces and the student experience. J. Learn. Spaces 2018, 7, 601410. [Google Scholar]

- Marble, S.; Fairbanks, K. Toni Stabile Student Center, Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism-Marble Fairbanks. Archit. Des. 2009, 79, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewe, M. (Ed.) Renewing Our Libraries: Case Studies in RE-Planning and Refurbishment; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Chen, Z.; Kong, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.J. The prevention strategies for strengthening the resilience of urban high-rise and high-density built environment based on multi-objective optimization: An empirical study in Guangzhou, China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 101, 107106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, J.; Xiong, K.; Liu, S.; He, B.-J. Identification of factors affecting public willingness to pay for heat mitigation and adaptation: Evidence from Guangzhou, China. Urban Clim. 2023, 48, 101405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias Pereira, L.; Bispo Lamas, F.; Gameiro da Silva, M. Improving energy use in schools: From IEQ towards energy-efficient planning—Method and in-field application to two case studies. Energy Effic. 2019, 12, 1253–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Mehari, A.; Genovese, P.V. The Relationship between Spatial Behavior and External Spatial Elements in Ancient Villages Based on GPS-GIS: A Case Study of Huangshan Hinterland, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.M.; Yang, Y.; Nguyen, T.D.; Yuan, S.; Xie, L. ULOC: Learning to Localize in Complex Large-Scale Environments with Ultra-Wideband Ranges. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.11122. [Google Scholar]

- Brunacci, V.; De Angelis, A.; Costante, G.; Carbone, P. Development and analysis of a UWB relative localization system. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezici, S.; Tian, Z.; Giannakis, G.B.; Kobayashi, H.; Molisch, A.F.; Poor, H.V.; Sahinoglu, Z. Localization via ultra-wideband radios: A look at positioning aspects for future sensor networks. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2005, 22, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, R.; Swaisaenyakorn, S.; Parini, C.G.; Batchelor, J.; Alomainy, A. Localization of wearable ultrawideband antennas for motion capture applications. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2014, 13, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberghe, S.; Mikhaylova, E.; D’Hoe, E.; Mollet, P.; Karp, J.S. Recent developments in time-of-flight PET. EJNMMI Phys. 2016, 3, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamyrin, B.A. Time-of-flight mass spectrometry (concepts, achievements, and prospects). Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2001, 206, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindhelm, C.K. Activity recognition and step detection with smartphones: Towards terminal based indoor positioning system. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on Personal, Indoor and Mobile Radio Communications-(PIMRC), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 9–12 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rangachari, S.; Loizou, P.C. A noise-estimation algorithm for highly non-stationary environments. Speech Commun. 2006, 48, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB50034-2024; Building Lighting Design Standard. China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2024.

- JGJ38-2015; Code for Design of Library Buildings. China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- GB50325-2020; Standard for Indoor Environmental Pollution Control of Civil Building Engineering. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Tibbits, G.; Jolly, L.; Szymakowski, J.; Maynard, N.; Tadé, M.O. The engineering pavilion—A learning space developing engineers for the global community. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning (ICL), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 3–6 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez, M.B.; Delgado-Kloos, C. Augmented reality for STEM learning: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2018, 123, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, H.; Thuneberg, H. The role of self-determination in informal and formal science learning contexts. Learn. Environ. Res. 2019, 22, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Han, C. The influence of learning styles on perception and preference of learning spaces in the university campus. Buildings 2021, 11, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancheva, E.; Ivanova, M. Informal learning in the workplace: Gender differences. In Private World(s) Gender and Informal Learning of Adults; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 157–182. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y.; Zhao, F.; Xue, M.; Jiang, B.; Lau, S.S.Y.; Zhang, L. Factors Influencing Seating Preferences in Semi-Outdoor Learning Spaces at Tropical Universities. Buildings 2023, 13, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; Luther, M.; Chil, B.; Zhao, J.; Liu, C. Students’ sound environment perceptions in informal learning spaces: A case study on a university campus in Australia. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 1, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, T. Learning at work in technology intensive environments. J. Workplace Learn. 2002, 14, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, Y.K.; Chen, Y. The influence of indoor environmental factors on learning: An experiment combining physiological and psychological measurements. Build. Environ. 2022, 221, 109299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs. Help: Typical Noise Levels and Subjective Evaluation. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/search/all?keywords=noise (accessed on 13 May 2012).

- Lee, K.E.; Williams, K.J.; Sargent, L.D.; Williams, N.S.; Johnson, K.A. 40-second green roof views sustain attention: The role of micro-breaks in attention restoration. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, H.; White, M.P.; Wheeler, B.W.; Bethel, A.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Nikolaou, V.; Garside, R. Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2016, 19, 305–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waxman, L.; Clemons, S.; Banning, J.; McKelfresh, D. The library as place: Providing students with opportunities for socialization, relaxation, and restoration. New Libr. World 2007, 108, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukiran, J.M.; Ariffin, J.; Ghani, A.N.A. Cooling effects of two types of tree canopy shape in Penang, Malaysia. GEOMATE J. 2016, 11, 2275–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, K.; Ge, J. Predicting the temperature distribution of a non-enclosed atrium and adjacent zones based on the Block model. Build. Environ. 2022, 214, 108952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandvliet, D.; Broekhuizen, A. Spaces for learning: Development and validation of the School Physical and Campus Environment Survey. Learn. Environ. Res. 2017, 20, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Library Abbreviation | GDUT-L | GMD-L | HSPY-L | HN-L | GDDXC-L | GZCLO-L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of ILS | Inserted into the existing learning space in groups, scattered in various areas of each floor. | Appearing in small groups, mainly distributed on the first and highest floors. | Appearing in small groups and distributed on the first floor. | |||

| Important cluster name | Music group, 24 h study group, art group, exhibition group, innovation group. | Literature centre, music centre. | Reading group, music group. | Art group. | Exhibition group, catering group. | Exhibition group |

| Number of clusters | 7 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Renovation time | 2022 | 2023 | 2010 | 2013 | 2018 | 2013 |

| Feasibility of measuring | Higher | High | Low | High | High | High |

| Key case | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Number | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 | Cluster 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILS-1 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| ILS-2 | × | × | √ | × | × | × | √ |

| ILS-3 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| ILS-4 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Space quality | Higher | Ordinary | Higher | High | Ordinary | Ordinary | Higher |

| Unique feature | 24 h open | Alumni document exhibition | Strong learning atmosphere | Piano room | Surround atria | Including training room | Including training room |

| Scale (m2) | 72 | 182 | 213 | 468 | 336 | 170 | 170 |

| Number of users | 10–15 | 15–25 | 30–40 | 40–60 | 12 | 20–25 | 25–30 |

| Feasibility of measuring | High | High | High | Low | Lower | Low | Low |

| Key case | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Type Characteristics | Corresponding Indicators |

|---|---|

| 1. Frequency range | 3.5 GHz to 4.2 GHz |

| 2. Data transfer rate | Default 6.8 Mbps, supports 110 Kbps or 850 kbps |

| 3. Typical transmission power | −22 dBm |

| 4. X-Y positioning accuracy | Error value less than 10 cm |

| 5. Point to point range | Maximum value of 300 m |

| 6. Operation temperature | −40–60 °C |

| Ranking | Number 1 | Number 2 | Number 3 | Number 4 | Number 5 | Number 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | 6/21 | 5/21 | 4/21 | 3/21 | 2/21 | 1/21 |

| Factor | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | A6 |

| Types | Number | Impact Factor | Satisfactory Rate | Average Rate | Complaint Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. (Physical factors) | 1 | P1. Temperature | 26.47% | 55.88% | 17.65% |

| 2 | P2. Carbon dioxide content | 47.06% | 41.18% | 11.76% | |

| 3 | P3. Noise | 50.95% | 38.49% | 10.56% | |

| 4 | P4. Illuminance | 50.00% | 32.35% | 17.65% | |

| S. (Spatial ontology) | 5 | S1. Space scale | 52.94% | 41.18% | 5.88% |

| 6 | S2. Spatial layout | 46.05% | 39.24% | 14.71% | |

| 7 | S3. Accessibility | 44.12% | 50.00% | 5.88% | |

| 8 | S4. Space level | 38.24% | 50.00% | 11.76% | |

| 9 | S6. Windows and view | 26.47% | 50.00% | 23.53% | |

| 10 | S8. Opening duration | 35.29% | 42.17% | 22.54% | |

| F. (Space facilities) | 11 | F1. Adequate equipment | 51.00% | 38.24% | 10.76% |

| 12 | F2. Adjustable seats | 35.29% | 38.24% | 26.47% | |

| 13 | F3. Storage space | 38.24% | 34.29% | 27.47% | |

| 14 | F4. Coffee and drinks | 28.40% | 45.13% | 26.47% | |

| A. (Atmosphere building) | 15 | A1. Cleanliness level | 33.29% | 43.18% | 23.53% |

| 16 | A2. Space privacy | 35.29% | 47.06% | 17.65% | |

| 17 | A3. Space openness | 17.65% | 38.24% | 44.12% | |

| 18 | A4. Space hue | 29.41% | 58.82% | 11.76% | |

| 19 | A5. Spatial flexibility | 35.29% | 47.06% | 17.65% | |

| 20 | A6. Nature friendly | 26.47% | 41.18% | 32.35% |

| Number | Factors | Weight | Sum of Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Space privacy | 10.34% | 50.58% |

| 2 | Illuminance | 9.20% | |

| 3 | Noise level (dB A) | 8.62% | |

| 4 | Temperature | 8.05% | |

| 5 | Space scale | 7.47% | |

| 6 | Adequate equipment | 6.90% | |

| 7 | Adjustable seats | 5.75% | 49.42% |

| 8 | Opening duration | 5.17% | |

| 9 | Carbon dioxide content | 4.78% | |

| 10 | Nature friendly | 4.42% | |

| 11 | Spatial layout | 4.18% | |

| 12 | Spatial flexibility | 4.02% | |

| 13 | Space hue | 3.96% | |

| 14 | Storage space | 3.76% | |

| 15 | Space level | 3.04% | |

| 16 | Windows and view | 2.87% | |

| 17 | Accessibility | 2.50% | |

| 18 | Cleanliness | 2.10% | |

| 19 | Space openness | 1.72% | |

| 20 | Coffee and drinks | 1.15% |

| Key Elements | Weight | Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| P. (Physical factors) | 30.65% | 1 |

| S. (Spatial ontology) | 25.03% | 3 |

| E. (Space equipment) | 17.56% | 4 |

| A. (Atmosphere building) | 26.76% | 2 |

| Different Scholars | Average Noise in the Quiet Zone | Average Noise in the Dynamic Area | Overall Average Noise Level | Average Noise Fluctuation in Adjacent Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harrop and Turpin | 51.6 dB | 55.0 dB | 53.1 dB | ±3.4 dB |

| This study | 50.2 dB (ILS-2), 52.4 dB (ILS-1) | 53.2 dB (ILS-3), 56.6 dB (ILS-4) | 53.1 dB | ±0.8–3.4 dB |

| Different Libraries | Average Noise in the Quiet Zone | Average Noise in the Dynamic Area | Overall Average Noise Level | Average Noise Fluctuation in Adjacent Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Group embedded’ mode | 50.2 dB (ILS-2), 52.4 dB (ILS-1) | 53.2 dB (ILS-3), 56.6 dB (ILS-4) | 53.1 dB | ±0.8–3.4 dB |

| ‘Independent separation’ mode | 44.5 dB | 57.9 dB | 51.2 dB | ±13.4 dB |

| ‘Boundaryless’ mode | 62.0 dB | 66.9 dB | 64.2 dB | 0.6–2.5 dB * |

| Method | Specific Measures |

|---|---|

| 1. Natural materials | Choose natural materials such as wood, stone, and bamboo for decoration, and use wooden furniture. |

| 2. Natural light | By designing large windows or folding doors, natural light can enter and create a bright and comfortable natural atmosphere. |

| 3. Green plants or plant walls | Install green plants and plant walls in shared spaces or corners, such as foliage plants or fresh flowers. |

| 4. Open space layout | Create environments that can be in contact with nature, utilising courtyards for multi-level design. |

| 5. Soft furnishings and handicrafts | Choose abstract soft furnishings with natural imagery, such as trees or flowers. Use handicrafts such as weaving and embroidery to add natural elements. |

| 6. Colour combinations | Use natural colours such as wood brown, light brown, and green. |

| Optimisation Strategy | Main Improving Factors | Auxiliary Improving Factors |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Use partitions, bookshelves, storage cabinets, or large green plants for separation. | A2. Space privacy | P3. Noise; P1. Temperature E3. Storage space; A6. Pro-nature design; |

| 2. Strengthen the top lighting, install desk lamps, use more transparent materials for the atrium, and add doors to enter the outer corridor. | P4. Illuminance | S5. Landscape view; A3. Space openness |

| 3. Add sound insulation materials around the discussion or collaboration area. | P3. Noise interference | A2. Space privacy |

| 4. Air vents should be opened at the top of the atrium, and the internal space should adopt an intelligent temperature control system. | P1. Temperature | P2. Air quality |

| 5. Improve the fresh air system and enhance air flow. | P2. Air quality | P1. Temperature |

| 6. Use natural materials and handicrafts; use natural colours more in colour matching; add green plants to introduce natural scenery. | A6. Pro-nature design | P1. Temperature; A3. Space openness |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Song, J.; Guo, W.; Wan, G.; Caneparo, L.; Liu, X. Impact of Multiple Environmental Factors of Space Clusters for Informal Learning in Library Renovation and Update. Buildings 2025, 15, 4530. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244530

Wang L, Song J, Guo W, Wan G, Caneparo L, Liu X. Impact of Multiple Environmental Factors of Space Clusters for Informal Learning in Library Renovation and Update. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4530. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244530

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Li, Jiru Song, Weihong Guo, Guangting Wan, Luca Caneparo, and Xiao Liu. 2025. "Impact of Multiple Environmental Factors of Space Clusters for Informal Learning in Library Renovation and Update" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4530. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244530

APA StyleWang, L., Song, J., Guo, W., Wan, G., Caneparo, L., & Liu, X. (2025). Impact of Multiple Environmental Factors of Space Clusters for Informal Learning in Library Renovation and Update. Buildings, 15(24), 4530. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244530