Abstract

Building placement strongly conditions performance, experience, and meaning in architecture and urban planning, yet siting rationales in design studio work are rarely made explicit or examined systematically. This post hoc, observational study analyzes 22 student proposals for a paddle school on a defended coastal headland in Cascais, Portugal, to reveal siting patterns and test convergence toward an expert recommendation. Each project is mapped onto a common grid and encoded as building mass and external paths, and a site-specific expert prior is formalized as a polygon that follows the defended wall and upper terrace, combining edge protection, elevation, and ocean prospect. Alignment with this prior is assessed using exact permutation tests under uniform and elevation-stratified random siting, and each proposal is summarized by three descriptors that capture where mass concentrates, how far it extends, and how broadly it uses the site. Results show a pronounced nucleus along the upper terrace, a contour-parallel circulation spine, and extensive underused areas elsewhere, with alignment to the expert prior significantly above chance. Clustering projects by the three descriptors differentiates siting families, from edge-anchored schemes to prospect-led variants and a small set of deliberate counterexamples. The framework turns studio designs into auditable evidence of how cohorts occupy a site and makes siting heuristics explicit and testable, supporting more transparent discussion of site strategies in architectural education and informing practice-oriented design guidance.

1. Introduction

In architecture and urban planning, where a building is placed on a site is rarely a neutral choice. Siting decisions bring together multiple objectives such as programmatic fit, access and mobility, exposure and refuge, prospect and constraint, and they often determine how a project will be lived and perceived in the long term, influencing daylight, microclimate, accessibility, and future adaptability. In this paper, we use the term siting for placement within a given site (architectural localization) and reserve site selection for the choice between alternative sites [1].

Phenomenological accounts of place stress how edges, thresholds and horizons structure the experience of site and anchor architectural meaning [1]. Landscape-based readings of prospect and refuge similarly highlight defended edges, elevated benches and long views as key to how occupants perceive safety and outlook [2,3]. Morphological and configurational approaches show how linear terraces, streets and walls help organize co-presence and movement patterns in everyday urban space [4,5]. In this study, we treat these architectural readings not as background rhetoric but as hypotheses about siting that can be made explicit, encoded and tested at cohort scale.

In both practice and education, however, the reasoning behind siting tends to remain tacit and is seldom examined in a systematic way. It is embedded in accumulated professional experience, in how designers read edge and field, and in the compressed dialogue of desk crits and reviews [6,7]. Students see individual placements and hear local arguments for or against them, but the cohort-level patterns that emerge across a group or over several years often remain invisible. What is not made comparable and commensurable is hard to teach, to assess, and to transfer.

Recent work in spatial analytics, visual analytics and urban morphology shows that drawings and plans can be turned into comparable evidence without abandoning architectural interpretation. Heatmaps, cohort summaries and reproducible pipelines have been used to document urban typologies, land use and public space patterns in ways that remain legible to designers [8,9,10,11]. Related work in architectural education has used visual analytics and AI-assisted image generation to turn studio processes into analyzable evidence [12]. At the same time, planning research has long treated siting as a multi-objective decision problem that can be framed through explicit preferences, coverage objectives and trade-offs between criteria such as access, protection and exposure [13,14]. Together, these strands imply that siting heuristics can be clarified, tested and debated rather than simply assumed.

Our stance in this research is primarily architectural, with computational facets regarded as supporting evidence. Drawings and studio intent lead, and computation provides a lens that keeps readings consistent across the cohort. We use a simple grid representation of the site and a lightweight Buildings (B) and Paths (P) encoding so that the analytical language remains close to how architects already read plans. From this encoding we derive three interpretable descriptors of each project’s use of the site. Focus summarizes where building mass tends to land, spread describes how far it extends, and breadth indicates how much of the admissible field is effectively used. Computation does not generate form; it organizes evidence about where projects have actually been placed.

To connect cohort patterns with practice-based judgment, we introduce an expert prior. By this, we mean a site-specific, experience-based hypothesis about where an experienced architect, reading the same context, would tend to place the building. In the present study, that hypothesis gives special weight to the defended wall and upper terrace and combines edge protection, elevation and ocean view, which are recurrent siting logics in coastal fortification sites [1,2,3]. We formalize this expert prior as a polygon that is independent of student work and use it as a yardstick for alignment. Section 3.4 details how the prior was specified and how it was kept concealed from students during studio teaching.

The empirical setting is a second-year architecture studio with 22 students working on a compact sports and teaching facility on a defended coastal terrace. Students designed freely on a common topographic base and without any expert baseline during the semester. Only after the studio concluded did we remap each project onto a neutral grid, encode buildings and paths, and construct the expert prior. The study is therefore post hoc and observational. We report descriptive and explanatory evidence about cohort-level patterns, alignment and heterogeneity, not causal effects of any intervention.

Conceptually, the aim of this work is not to introduce yet another generic spatial-analysis technique, but to bring together three strands that are often treated separately: phenomenological readings of place and edge, morphological accounts and pattern-based heuristics for siting in design studio. Building on these traditions, we treat siting as a field of architectural judgment that can be rendered explicit rather than as an opaque by-product of individual schemes. The framework we propose has a dual contribution. Architecturally and pedagogically, it offers a compact vocabulary of siting patterns that can be used to structure critique, compare alternatives and discuss deliberate departures from a prior. Methodologically, it shows how a neutral grid, a lightweight Buildings/Paths encoding and simple permutation-based metrics can turn a studio cohort into auditable evidence about how a site is actually occupied, without displacing drawings or design intent. In this way, the study responds to the Issue’s focus by demonstrating how visual analytics can strengthen, rather than replace, architectural reasoning about siting.

Within this frame, we address three questions that are stated explicitly as testable hypotheses. H1 asks whether siting choices depart from a uniform use of the admissible field in ways that reveal recurrent cohort-level patterns for buildings and paths. H2 asks whether cohort placements align more closely with the expert prior than expected under permutation-based nulls that respect the geometry of the site, including elevation structure. H3 asks whether the cohort decomposes into a small number of readable siting families in the space defined by the three descriptors instead of forming a diffuse cloud of unrelated solutions. In later sections we refer to a building nucleus, a contour-parallel spine, and short connective stitches and gateways along the terrace; their precise meaning is defined in Section Terminology for Site and Circulation.

By answering these questions, the research offers three contributions. First, it proposes a reproducible and auditable protocol that turns studio outcomes into cohort-scale siting evidence that can travel across sites and institutions. Second, it provides quantitative support for recurrent siting pattern heuristics [15], including a clear formulation of an expert prior that remains falsifiable rather than prescriptive. Third, it suggests a metacognitive scaffold for architectural education in which students and tutors can see where a cohort converges, where it diverges and which parts of a site tend to remain unexplored, with potential implications for both studio teaching and early-stage practice.

2. Case Study and Research Setting

2.1. Context and Program

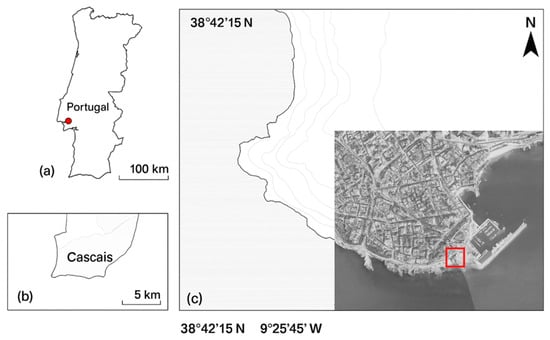

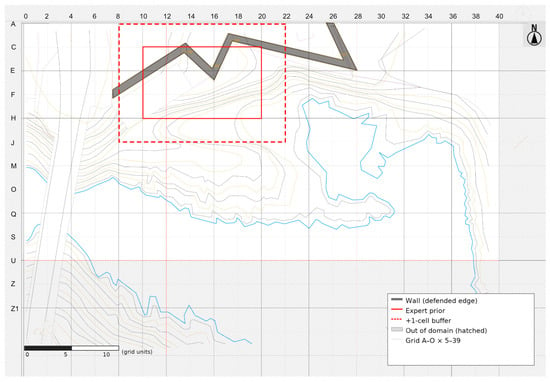

The empirical setting is a second-year architecture studio in which 22 students work on a compact sports and teaching facility on a coastal headland in Cascais, Portugal, west of Lisbon (Figure 1). The site occupies a defended terrace overlooking the Atlantic, with a seventeenth-century wall on the landward side and a stepped topography descending toward the water. At territorial scale, Figure 1 locates the headland within Cascais and delineates the project intervention area. At site scale, Figure 2 presents the analytical grid and study boundary, showing the admissible field, the expert prior, and its one-cell buffer.

Figure 1.

Location analysis map of the study area. (a) Portugal, with a red dot marking the Cascais–Lisbon coastal area on the western coast. (b) Municipal context of Cascais within the Lisbon metropolitan region. (c) Local site around Praia de Santa Marta, with the study area (red square) centered at approximately 38.6916° N, 9.4210° W. Lightly shaded and hatched backgrounds differentiate land, sea and base aerial imagery.

Figure 2.

Analytical site plan with a 15 × 35 grid over the admissible field (hatched outside), showing the defended wall (dark gray), the expert prior polygon (solid red), and its +1-cell buffer (dashed red). The blue line marks the shoreline and the coastal headland. Distances are expressed in grid units.

The brief asks students to design a small padel school with indoor and outdoor courts, basic teaching and support spaces, and service access for deliveries and maintenance. Beyond satisfying the functional program, the project is framed explicitly as a siting exercise in which the building must engage the existing structure of the place. Students are invited to work with three recurrent demands in coastal fortification sites: (i) clear and legible service access that does not compromise the public edge; (ii) weather-sheltered edges near the defended wall; and (iii) a processional sequence that prolongs and intensifies the ocean prospect instead of treating it as a single viewpoint.

Students work from a common topographic base that identifies the wall, the main level breaks, and the shoreline. They are encouraged to explore different ways of anchoring mass to the wall, negotiating level change, and opening views, but they were not provided with any explicit analytical baseline or preferred siting zone during the semester. Analysis and hypothesis specification, including the definition of the expert prior, were undertaken only after studio completion in order to avoid feedback bias. The studio thus offers a controlled but naturalistic setting in which siting behavior can be observed under a shared brief without explicit steering toward a particular zone.

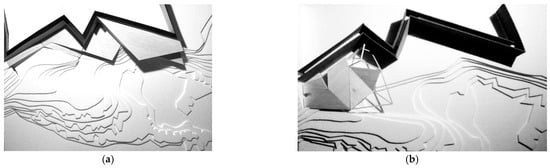

Figure 3a,b illustrates two representative 1:100 study models from early stages of the studio. One explores a hinged landing that crosses the ridge and then follows a contour-parallel promenade along the wall. The other opts for a more compact anchor against the wall with a stitched terrace segment. Both examples show how students coupled massing and slope lines in physical models before any analytical encoding was introduced.

Figure 3.

(a,b) Representative 1:100 study models from the studio cohort. Two distinct strategies along the defended wall and stepped terrain: (a) hinged landing with ridge-crossing and contour-parallel promenade, (b) compact edge anchor with a stitched terrace segment. The sequence illustrates how students coupled architectural massing with slope lines before the analytical encoding used later in the paper.

2.2. Site Structure and Affordances

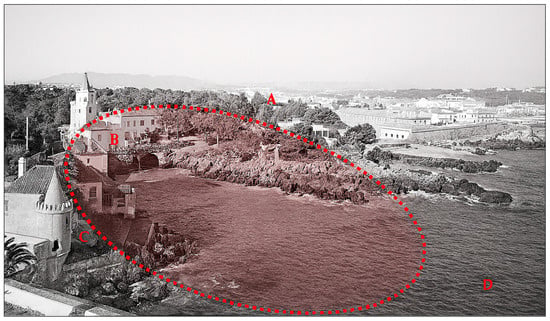

The site can be read as a clear edge–elevation–prospect archetype. A defended wall defines a linear edge along the upper terrace. The ground then steps down toward the ocean in a sequence of benches that alternate exposure and shelter (Figure 4). This simple but powerful structure resonates with classical accounts of urban form and street centrality that stress the role of linear edges, breaks in slope, and long views in organizing movement and attention [11,16,17].

Figure 4.

Archival photograph of the study area in Cascais, Portugal. A—17th-century fortress; B—19th-century bridge; C—opposite shore with a 20th-century house by architect Raul Lino; D—Atlantic Ocean. The red dotted line marks the project intervention area.

Three intertwined logics, familiar to practicing architects, organize siting judgments on this terrace and provide the analytical frame for the study.

Edge and heritage: The wall acts at once as a wind buffer, a civic interface, and a strong spatial datum. Buildings that lean on it can borrow its thickness and continuity, but they must also respect its heritage value and public character.

Elevation and prospect: The upper terrace offers long views along and across the coast, together with a degree of protection from direct exposure. Benches and contour breaks mediate this exposure and provide intermediate positions. Placements that sit too low risk losing the prospect and reading as detached from the defended edge.

Access across gradient: Movement parallel to the contour keeps effort manageable, while selective ridge crossings and short ramps create decisive links between levels. A coherent siting strategy should therefore incorporate at least one clear, contour-aligned spine and a few robust connectors that unify the terraces.

Taken together, these affordances motivate the hypothesis that many robust solutions will sit near the wall–terrace interface, with an arm of movement running along the upper bench. In the analytical framework, this hypothesis is captured by the expert prior polygon: an elongated band along the upper terrace adjacent to the defended wall, later tested against permutation-based nulls. For sensitivity analyses, a one-cell buffer around this polygon accommodates boundary uncertainty and small registration errors.

The analytical site plan in Figure 2 shows the 15 × 35 grid that discretizes the admissible field, together with the defended wall and the shoreline. The expert prior appears as a shaded band along the wall on the upper terrace, with its buffered variant indicated by a dashed outline. While the polygon is introduced here as a visual element, its provenance, operational definition, and role in the statistical tests are detailed in Section 3.4. In what follows, we use the term nucleus for the upper-terrace band where building mass tends to concentrate and spine for the main contour-parallel route that organizes movement across the site.

2.3. Cohort, Task, and Ethics

The cohort comprises 22 students enrolled in the same design studio under a common brief, timetable, and support infrastructure. Teaching follows a conventional studio format with weekly desk crits and intermediate reviews. Students are free to choose their siting and massing strategies, as long as they respect basic constraints on protected fabric and access to the wall. No quantitative analytics or siting tools are provided during the semester, and the expert previously used in the analysis is deliberately concealed from students.

At the end of the term, each student submits a set of drawings and physical models that document their proposal. For the present study, we use plan drawings at a consistent scale and the associated topographic information as the primary analytical material. All submissions are anonymized and assigned stable codes before encoding; participation in the analytical study is independent of grading, and no personal or physiological data are collected. According to institutional guidelines, this use of anonymized student work does not constitute research with human subjects. The combination of a shared brief, a single site, and a cohort of 22 independent proposals provides a rich yet tractable dataset for cohort-scale analysis of siting, while preserving the individuality of each design.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Analytical Stance

The study is post hoc and observational. We do not intervene in the studio during the semester or provide students with quantitative siting tools. Instead, we read the completed proposals through a consistent spatial lens and ask whether their placements, taken together, exhibit regularities that depart from chance and align with an explicit siting hypothesis.

Our aim is architectural legibility rather than methodological novelty. Drawings and studio intent remain the primary carriers of meaning; heatmaps, descriptors, and tests exist to keep those readings comparable across students and transferable across cohorts, in line with recent cohort-scale urban visual analytics and typology discovery work [8,9,10,18,19].

The design unit is the individual project. The analytical support is a neutral grid over an admissible mask, but all inference is conducted at the project level to respect spatial dependence. Each project is summarized by a small set of interpretable descriptors, and cohort means are compared to permutation-based null distributions that preserve the geometry of the site.

The overall pipeline has four steps:

- Remap each project onto a common grid and define the admissible field.

- Encode buildings and paths as fractional cell weights.

- Derive project-level descriptors (focus, spread, breadth) and specify an expert prior polygon.

- Test alignment and solution families using permutation tests and clustering in descriptor space.

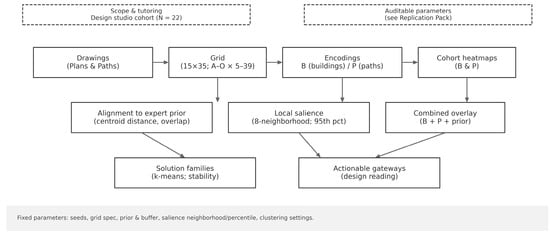

Figure 5 summarizes the end-to-end workflow. Formal equations and implementation details are outlined here and fully documented in the Supplementary Materials, together with a complete replication pack [19,20].

Figure 5.

Analysis workflow. Drawings → grid → B/P encodings → cohort heatmaps → prior-alignment tests → local salience → solution families. Parameters are fixed and reproducible (Replication Pack).

3.2. Neutral Grid and Admissible Field

To compare projects, we divide the admissible field into a 15 × 35 grid. Each cell covers roughly 2.5 × 2.5 m, close to the scale of a small platform where two or three people can stand or pass, and interact socially [21], so the grid remains architectural rather than a purely abstract raster [19]. Cells are indexed by row and column, and cell centers are used as reference points for distances. The resolution balances spatial detail and cohort size; sensitivity checks at ±25 percent yielded the same qualitative patterns of nuclei, underused areas, and alignment with the expert prior, as detailed in the Supplementary Materials.

We then define an admissible-cell mask that removes non-buildable areas such as water, protected fabric, and the wall’s footprint and structural buffer. Mask creation follows a simple rule set (digitized polygons → union → morphological clean-up), and the resulting admissible mask is included in the replication pack for audit and cartographic consistency [19].

3.3. Representation of Buildings and Paths

For each student project, we work from the final plan at a common scale. Building footprints and primary circulation paths are redrawn on the analytical grid. The goal is not to trace every door and step, but to capture the main volumes and movement lines in a way that remains faithful to the architectural intent.

We distinguish:

- Buildings (B): closed footprints or compact clusters of rooms that read as building mass.

- Paths (P): main circulation routes that organize movement across the site, including contour-parallel promenades and decisive ridge crossings.

For each cell, we estimate the fraction of its area occupied by buildings or crossed by paths. Let and denote the raw coverage fractions in cell . These fractions are then quantized to quarter steps in the set to make hand encoding robust and to avoid spurious precision. The resulting values and are used as building and path weights.

Cohort heatmaps for buildings and paths are obtained by summing these weights across the 22 projects and then normalizing by the number of projects. Top-cell tables list the cells in the top decile of cohort building or path weight, making the main landing zones and connectors auditable in a way that parallels previous cohort-scale “where the work lands” analyses [8,9].

All encodings were performed by a single primary operator trained in both architectural drawing and spatial analysis. A second researcher independently re-encoded a stratified subset of projects (25 percent of the cohort) to check consistency. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved, and the agreed-upon rules are given in the Supplementary Materials together with a short codebook.

Having a common grid and a consistent representation of buildings and paths allows us to ask not only how each project uses the site, but also how the cohort relates to an explicit siting hypothesis. We make this hypothesis concrete in the form of an expert prior, described next.

Terminology for Site and Circulation

Several terms used later in the Results are defined here for clarity.

- Ridge is the high line of the headland that runs broadly parallel to the defended wall and defines the upper terrace.

- Nucleus refers to the upper-terrace band near the wall where building mass tends to concentrate.

- Spine is the principal contour-parallel path on the upper terrace that organizes movement across the site.

- Stitches are short links that either maintain continuity along the spine or cross the ridge at decisive points between terraces.

- Gateways are edge entrances or hinges where movement converges to access the building nucleus.

- The expert prior is a pre-specified polygon over the upper-terrace band adjacent to the wall, with a one-cell buffer that accounts for registration tolerances.

These terms keep the analytic language close to how architects already describe massing and circulation on stepped sites and resonate with wider accounts of spines and connectors in urban networks [16,22,23,24].

3.4. Expert Prior: Provenance and Concealment

The expert prior used in this study was not generated by an algorithm. It originates in the heuristic judgment of the studio coordinator, an architect with long-standing experience in site planning and in teaching this studio. The polygon was discussed and agreed upon within the eight-member teaching team responsible for the studio, who shared weekly tutorials and reviews, so it reflects a collective professional reading of the site rather than a single idiosyncratic preference. In earlier iterations of the same course, the coordinator had expressed a clear recommendation that buildings should engage the defended wall and the upper terrace to combine protection, elevation, and ocean prospect in a compact, walkable ensemble, consistent with established readings of coastal fortification sites [1,2,3].

For the cohort analyzed in this paper, we deliberately concealed this recommendation from students in order to observe their siting behavior without direct guidance toward a specific zone. Students received the same topographic base, program, and site constraints, but at no point during the semester were they shown any expert baseline for placement. Only after the studio concluded did we formalize the coordinator’s heuristic stance as a polygonal expert prior to the analytical grid, as described in Section 3.2, and fix it before any alignment analyses were run.

A grid cell is counted as inside the expert prior if its center lies inside the polygon. All alignment metrics are based on this binary inside-or-outside assignment at the cell level, combined with the weighted building layer at the project level. In the Discussion, we return to the fact that this remains a single, site-specific prior—albeit agreed within one coordinated teaching team—and we treat it explicitly as an experience-based hypothesis rather than as a normative rule.

3.5. Project-Level Descriptors: Focus, Spread, and Breadth

To summarize how each project uses the site, we derive three interpretable descriptors from the building weights: focus, spread, and breadth. These descriptors are designed so that an architect can read them intuitively while they remain amenable to statistical analysis and typology discovery [9,25].

Let index the admissible cells and let be the coordinates of the center of cell .

Focus is the weighted centroid of building mass (1):

It answers the question of where the mass tends to land.

Spread is the radius of gyration of building mass around the focus (2):

where is the Euclidean distance between cell center and the focus. Spread captures how far the project extends in plan.

Breadth is the normalized entropy of the building weight distribution over the admissible field (3):

where is the probability mass at cell . Breadth ranges from 0 to 1 and indicates how broadly the project explores the field.

Equations (1)–(3) parallel compact descriptors used in urban morphology and pattern analysis [9,25] and provide a low-dimensional, readable basis for later clustering. Additional details on units and conversion from grid units to meters are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

3.6. Alignment Metrics and Normalization for Building Area

We use two complementary metrics to quantify alignment between projects and the expert prior: centroid-to-prior distance and mass overlap. Both metrics operate at the project level and are defined in ways that explicitly control for differences in total building area, in line with enrichment-style measures in spatial analysis [25,26,27].

Centroid-to-prior distance: For each project, we compute the Euclidean distance between its building focus and the nearest admissible cell center inside the expert prior polygon. This yields a single distance per project . Lower values indicate that the project’s main mass is closer to the prior. Cohort alignment is summarized by the mean distance across the 22 projects.

Mass overlap proportion: For each project, we compute the proportion of its building mass that falls inside the prior area (4):

where is the set of cells whose centers lie inside the prior polygon and is the admissible field. This proportion is invariant to the total building area of project and directly addresses the concern that differences in overall building size could distort overlap.

At the cohort level we report the mean overlap across projects and an enrichment odds ratio that compares the share of building mass inside the prior to the share of grid cells covered by the prior within the admissible field [26,27]. The odds ratio expresses how much more intensively the prior band is used than would be expected from its size alone. The distribution of total building area across projects and its relationship to are reported in the Supplementary Materials; these diagnostics indicate that the overlap metric is not dominated by larger schemes.

3.7. Permutation Design, Elevation Structure, and Uncertainty

To formalize the idea of “closer than chance,” we compare the observed cohort statistics to permutation-based null distributions that preserve the geometry of the site. Rather than permuting individual cells, we randomize project centroids within the admissible field, so that inference remains at the project level and per-cell multiple testing is avoided [25].

We use two families of nulls:

- Uniform null: For each permutation replicate we randomize the locations of building foci across the admissible field while preserving the set of admissible cells. This effectively asks how far from the prior we would expect the cohort mean centroid distance to be if sitings were uniform over the field.

- Elevation-stratified null: To respect the site’s elevation structure, we also build a null in which centroids are only shuffled within their original elevation stratum. This tests whether alignment can be explained solely by a generic preference for higher ground, or whether there is additional structure tied to the defended wall-upper-terrace band [19,23,24].

For each null type we generate permutation replicates in the main analysis (here ), and use these to approximate the null distribution of the cohort statistic. For each test, we report the exact permutation p-value, defined as the proportion of permutation replicates that are as or more extreme than the observed value, with the inequality reversed where appropriate for overlap [25].

To quantify uncertainty, we also compute bias-corrected and accelerated 95 percent confidence intervals for the observed cohort statistics using bootstrap resampling at the project level [28]. Standardized effect sizes are reported: for distances we use the difference between the null mean and observed mean in units of the null standard deviation, and for overlap we report the odds ratio with its 95 percent confidence interval. For interpretability, we also give a common-language effect size defined as the probability that a random null replicate is less aligned than the observed cohort.

3.8. Locally Dominant Connectors in Paths

Global path counts can hide the importance of short, decisive connectors such as ridge crossings and contour-parallel stitches. To identify these elements, we compute a simple local salience measure over the path layer, following previous work that treats locally salient connectors as structural elements in movement networks [16,22,29].

For each admissible cell we calculate the sum of path weights in its 8-cell neighborhood and compare this to the distribution of such sums over the entire admissible field. Local salience is defined as the empirical percentile of this neighborhood sum. Cells at or above the 95th percentile are classified as locally dominant connectors.

This procedure highlights globally rare yet locally dominant segments whose removal would materially weaken access or legibility [16,22,29]. The choice of neighborhood size and percentile threshold was tested in sensitivity analyses; the identity of key connectors is stable across reasonable variations. Full neighborhood statistics and robustness checks, including Jaccard overlaps between salience sets, are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

3.9. Solution Families: Clustering and Validation

To address the third research question (H3), we examine whether the cohort decomposes into a small number of readable siting families rather than forming a diffuse cloud of unrelated solutions. We do this by clustering projects in the three-dimensional space of building descriptors: focus, spread, and breadth.

We standardize each descriptor across projects by z-scoring and run k-means clustering with k-means++ initialization. Candidate values of from 2 to 6 are scanned. For each we compute the average silhouette coefficient and the Davies–Bouldin index. We then select the smallest whose average silhouette lies within 5 percent of the best value, using the Davies–Bouldin index as a complementary check, following standard practice in internal cluster validation [30,31].

To avoid over-interpreting unstable partitions, we assess cluster stability using bootstrap resampling. We generate 1000 bootstrap samples of the 22 projects and re-cluster each sample with the selected . For each cluster we compute the Jaccard similarity between its membership in the full data and its membership in each bootstrap replicate. High Jaccard values indicate that a given family is stable under resampling.

Labels for the resulting families are assigned by architectural reading of their typical focus, spread, and breadth combinations rather than by numerical rank. This ensures that the typology remains legible to architects and consistent with the narrative vignettes in the Results. Internal correlations between descriptors are checked to ensure that no single dimension dominates the clustering.

3.10. Reproducibility and Supplementary Materials

All analyses were implemented in Python (version 3.10.12) using widely available libraries for numerical computing, spatial processing, and clustering. The replication pack contains the input grid, admissible mask, expert prior polygons, building and path layers for each project, project-level descriptors, permutation summaries, salience sets, and cluster assignments, together with an analysis notebook and an environment specification [19,20]. A checksum manifest and a short data dictionary allow external readers to verify file integrity and interpret fields.

To keep the main text readable, detailed file structures, parameter lists, and code-level descriptions are documented in the replication pack. All figures and tables in the paper correspond one-to-one with outputs in the replication pack, so that reviewers and readers can reproduce the key statistics without reconstructing the workflow from scratch [19,20]. Key numerical summaries are also provided as Supplementary Tables S1–S8 with the journal.

4. Results

We organize the results around the three hypotheses introduced in Section 1. Section 4.1 addresses H1 by examining how buildings and paths use (and leave unused) the admissible field. Section 4.2 addresses H2 by testing alignment with the expert prior under permutation-based null models. Section 4.3 zooms in on locally dominant connectors and shows how divergent sitings can remain coherent. Section 4.4 addresses H3 by identifying siting families in the focus–spread–breadth space. Section 4.5 summarizes these regularities and briefly notes robustness checks.

All distances are reported in grid units unless otherwise stated; meter equivalents and additional summaries are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

4.1. Cohort Portrait and Non-Uniform Site Use (H1)

We begin with an architectural reading of how the cohort uses the site and then check this reading against the grid-based evidence.

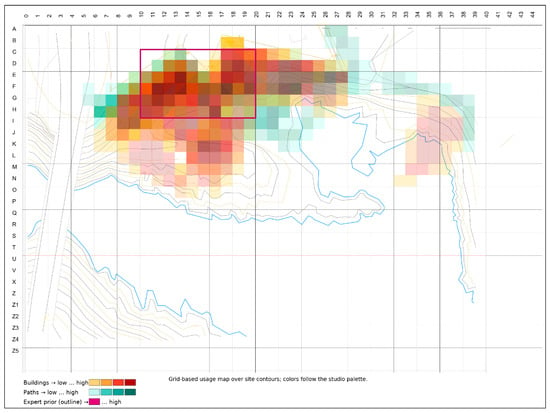

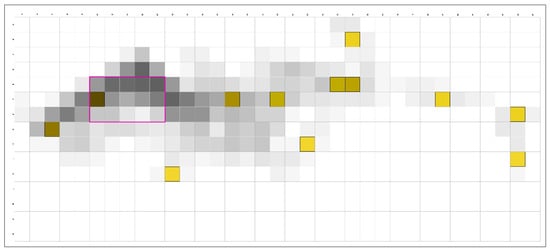

At the cohort scale, building use coalesces into a thick, legible band along the upper terrace adjacent to the defended wall. The highest building intensities form a nucleus centered approximately on E–G/10–14, where prospect, shelter, and service economy coincide (Figure 6). This nucleus behaves as a plateau rather than a single spike: a belt of two to three cells tolerates small shifts in placement while preserving the same siting logic of edge protection, elevated prospect, and proximity to the terrace for efficient access. The band aligns with the ridge and the main bench described in Section 2.2, and coincides with the upper-terrace portion of the expert prior defined in Section 3.4.

Figure 6.

Combined B (warm) and P (cool) overlays on the admissible field; expert prior rectangular outline in purple.

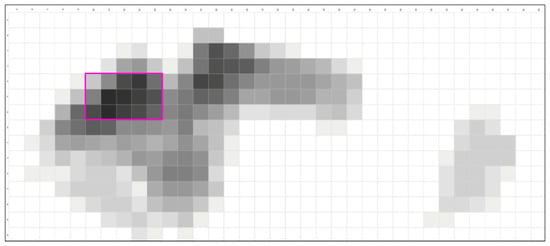

Coverage statistics confirm that the field is far from uniformly used. Buildings occupy 203 of 525 admissible cells (38.7%) (Figure 7), while paths occupy 171 cells (32.6%) (Figure 8); the union of building and path cells covers 257 cells (49.0%). Exactly 322 cells (61.3%) carry zero building weight (Figure 6). In other words, the cohort activates about half of the admissible grid and leaves the remainder unbuilt. Siting activity is concentrated in a narrow band around the wall–terrace interface rather than scattered across the entire field.

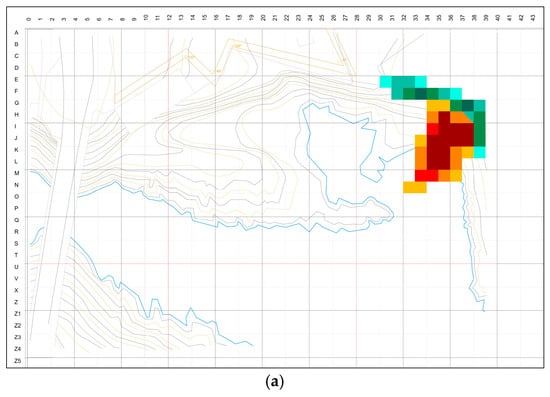

Figure 7.

Building (B) intensity across the cohort on the 15 × 35 grid (A–O × 5–39) over the admissible field. The cohort nucleus along the upper-terrace (E–G/10–14) is outlined in dark pink. The Colorbar displays the summed B-weights per-cell (N = 22), with no kernel smoothing applied.

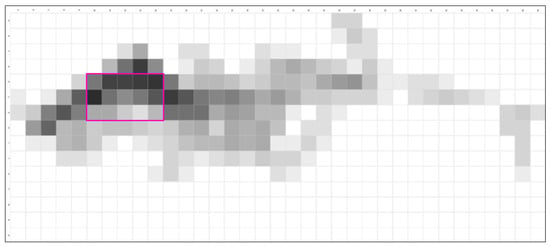

Figure 8.

Path (P) intensity across the cohort. Contour—parallel arm near F10–F15, with short stitches to and from the building nucleus (around F10–F15). Colorbar: summed P-weights (N = 22); no smoothing. Expert prior in a rectangular dark pink box.

Path intensity is organized as a clear contour-parallel spine along the upper terrace (roughly F10–F15), punctuated by short stitches that pull movement to and from the nucleus (Figure 8). The F10–F15 spine reads as a local axis of continuity and resilience: building mass anchors to the wall–terrace interface, and circulation sweeps the upper bench to minimize gradient costs while preserving view corridors. Variety appears mainly in where stitches “bite” into the spine and how the spine bends at terrace hinges, yielding teachable differences in access legibility and processional sequence. Table 1 lists the top-15 cells by weighted usage for buildings and paths.

Table 1.

Top-15 cells by weighted usage for B and P layers (N = 22).

A local salience lens refines this depiction. Using the neighborhood-based salience measure defined in Section 3.8, the ten most locally salient cells in the path layer have a mean z-score of 1.60 (range 1.37–1.93) relative to the distribution of neighborhood sums in the admissible field. These cells typically occur at ridge crossings and terrace hinges where short segments play outsized structural roles, echoing how locally central connectors behave in spatial street networks [29]. Section 4.3 revisits these cells in more detail.

Taken together, these findings support H1. The cohort does not distribute siting evenly across the admissible field. Instead, it converges on an edge–prospect nucleus with a directional path spine, leaving extensive areas underused.

4.2. Alignment with the Expert Prior (H2)

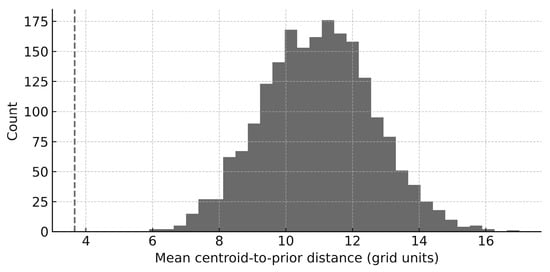

We next test whether this non-uniform pattern is more than a visual impression by quantifying alignment with the expert prior polygon. Alignment is measured at the project level using the two complementary metrics defined in Section 3.6: centroid-to-prior distance and mass overlap proportion. Exact permutation tests are used to assess whether the observed cohort statistics are closer to the prior than expected under the null [25]. Figure 9 shows the permutation null distribution for the cohort mean centroid-to-prior distance.

Figure 9.

Permutation null (M = 2000) for the cohort mean centroid-to-prior distance. The vertical line marks the observed mean (3.664 for the strict prior; 3.002 for the +1-cell buffered prior). One-sided p < 0.001 in both cases; bootstrap 95% CI [1.857, 6.094] for the strict prior.

Students’ building centroids are substantially closer to the expert prior than expected under a uniform null. An illustrative subset (N = 19) of student-level centroid distances to the prior is listed in Table 2 cohort-level mean distances and inference are based on all 22 projects and can be fully reproduced from the descriptors in the replication pack. Under the strict prior, the observed mean distance is 3.66 grid units compared to a null mean of 10.98 (one-sided permutation , approximately 4.3 standard deviations below the null mean). With a +1-cell buffered prior, the observed mean is 3.00 versus 9.83 (one-sided , approximately 4.1 standard deviations). A bootstrap 95% confidence interval for the observed mean distance under the strict prior is [1.86, 6.09], indicating that the cohort mean remains far from the null expectation even when sampling uncertainty is taken into account.

Table 2.

Illustrative subset (N = 19) of student-level centroid distances to the expert prior. Cohort-level statistics for all 22 projects are reported in Section 4.2; full per-project values are available in the replication pack.

Mass overlap tells a consistent story while explicitly controlling for differences in total building area. The expert prior covers 2.86% of grid cells in the admissible field, yet the cohort concentrates 19.5% of its building weight inside that band. This yields an enrichment odds ratio of 8.24 for inside-versus-outside occupancy (Supplementary Table S3). Because overlap is defined as a proportion of each project’s own building mass (Equation (4)), it is invariant to total building area and not driven by larger schemes. Correlations between total area and overlap are small and non-significant (Supplementary Materials), indicating that the enrichment is substantive rather than an artifact of size.

To address the concern that topography and spatial autocorrelation might inflate significance, we also examine null models that preserve the site’s elevation profile, as described in Section 3.7. Under elevation-stratified permutations, in which project centroids are only shuffled within their original elevation stratum (upper terrace versus lower benches), mean distances and overlaps remain substantially more aligned with the prior than expected by chance (full diagnostics in the Supplementary Materials). The closer-than-chance conclusion, therefore, does not arise solely from a generic preference for higher ground. Instead, it reflects a more specific alignment with the defended wall and upper-terrace band.

Robustness checks with buffered and data-driven priors (for example, a prior defined by the top decile of cohort building-weight cells) lead to the same qualitative conclusion: the expert prior is consonant with, rather than determinative of, cohort behavior, both in coverage (Table 3) and in mass overlap (Supplementary Table S3). Reported p-values are exact (permutation-based) [25], effect sizes are given alongside significance (standardized distance differences and odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals), and all inference is conducted at the project level to avoid per-cell multiple testing.

Table 3.

Cell-based coverage of the expert prior for Buildings (B) and corresponding odds ratio (OR).

For practice, lower mean distances indicate that, taken together, the projects tend toward the defended edge–upper-terrace band more than a random siting would. An odds ratio greater than one means that this band is used more intensively than its size alone would suggest. Within the limits of an observational design, these results support H2: the cohort aligns with the expert prior substantially more than expected under multiple null assumptions that respect both geometry and elevation.

4.3. Locally Dominant Connectors and Divergent Placements

Global heatmaps can mask the role of short, decisive connectors. The local salience measure defined in Section 3.8 recovers these segments and shows how minority solutions remain coherent when they strengthen the underlying connective grammar, in line with how locally central street segments underpin network resilience [29].

The 8-cell neighborhood salience measure identifies globally rare but locally dominant path segments. Recurrent high-salience cells appear near E13–F14 and F11–F12, where ridge crossings and terrace hinges link the contour-parallel spine to lower benches (Figure 10). These segments are not long in absolute terms, but their removal would sever access or blur the processional sequence. Salience sets are stable across reasonable changes in neighborhood size, weighting, and thresholds, with high Jaccard overlaps reported in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 10.

Paths (P) intensity with local salience overlay on the 15 × 35 grid (A–O × 5–39) over the admissible field. Locally dominant connectors (≥95th percentile). Salient cells within the admissible field; labels at E13–F14, E14–F14, F11–F12, D13, G8.

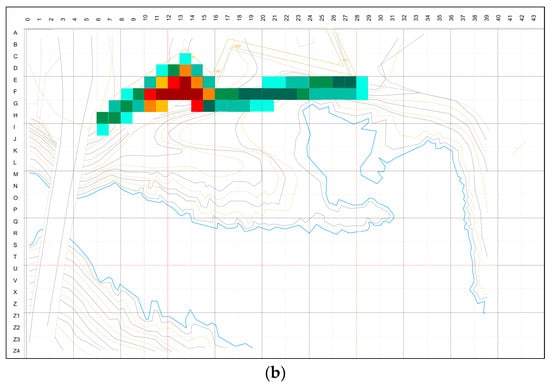

Two vignettes illustrate how projects can deviate from the main nucleus and still remain architecturally legible when they invest in such connectors (Figure 11a,b):

Figure 11.

(a,b) Cohort vignettes illustrating: (a) typical edge-anchored, arm-aligned, above (student S15) and (b) divergent lower-terrace, ridge-crossings, below (student S10) solutions.

- In one project, the centroid sits downslope, with the building settled into the slope rather than anchored directly on the upper terrace. The proposal remains coherent because a strong connector climbs back to the F10–F15 spine, preserving access and prospect despite the lower placement.

- In another project, the centroid projects seaward beyond the prior band, adopting a promontory-led stance. Here, a pair of robust connectors maintain attachment to the defended edge and the main circulation spine, preventing the building from reading as an isolated object.

In both cases, deviations from the prior increase exposure and construction demands, but they do so in a structurally intelligible way. These examples show that coherence without consensus is possible: minority sitings can depart from the common nucleus provided they reinforce the connective grammar encoded in the ridge, spine, stitches, and gateways. This nuance informs the interpretation of H2 by showing that alignment is a cohort-level regularity rather than an absolute requirement for coherence at the project level.

4.4. Solution Families in Focus–Spread–Breadth Space (H3)

To address H3 we examine whether projects cluster into a small number of siting families when described by focus, spread, and breadth (Equations (1)–(3)). We cluster the z-standardized triplets using k-means with k-means++ initialization and choose by the average silhouette score, cross-checked with the Davies–Bouldin index, following standard practice in internal cluster validation [30,31]. The selected solution has four clusters. Internal metrics and bootstrap stability assessments are provided in the replication pack (see Data Availability Statement).

The four families have clear architectural readings rather than opaque statistical labels:

- Type I: Deep (concentrated edge anchor).Projects in this group are concentrated around the nucleus and have low spread and low breadth. They favor a thick edge condition with service depth and compact circulation. Access is organized by a small number of short, high-quality gateways from the spine to the building.

- Type II: Extended (arm-aligned).Here, the mass leans along the terrace with moderate to high spread and intermediate breadth. Sectionally, these schemes read as a linear promenade along the bench, with a long arm that tracks the contour. This increases lateral prospect but depends on disciplined service docking to remain legible.

- Type III: Fragmented (benched scatter).These proposals distribute mass across several benches, with higher spread and breadth and more fragmented anchoring. They demand stronger structural stitching and careful placement of gateways to avoid noisy access and to keep the main spine intelligible.

- Type IV: Prospect-led (promontory bias).This family pushes mass toward the seaward side, prioritizing viewpoints. Exposure, structural reach, and service distances become constraints that need to be mitigated by dual connectors back to the defended edge and spine.

Family labels are assigned by architectural reading of typical focus–spread–breadth combinations rather than by numerical rank, keeping the typology legible to designers. Cluster membership is stable under bootstrap resampling for Types I–III, with Type IV appearing consistently in resamples that include sufficient promontory-led schemes (Supplementary Materials). This stability supports H3: the cohort decomposes into a small set of readable siting families rather than forming an amorphous cloud of unrelated solutions.

4.5. Summary and Robustness

Across the cohort, three empirical regularities emerge. First, the admissible field is used in a strongly non-uniform way: roughly half of the grid remains unbuilt, while buildings and paths concentrate in an edge–prospect nucleus with a contour-parallel spine and a small set of decisive connectors (Section 4.1 and Section 4.3). Second, siting aligns with the expert prior far more than expected under uniform and elevation-stratified null models, both in centroid-to-prior distance and in mass overlap (Section 4.2). Third, projects group into four siting families in focus–spread–breadth space, each with a distinct architectural stance that can be named and discussed in studio rather than treated as an undifferentiated cloud of alternatives (Section 4.4).

Sensitivity analyses reported in the Supplementary Materials show that these patterns are robust to changes in grid resolution, admissible mask, prior definition, and random seeds. Within the post hoc observational design described in Section 3, the cohort-level maps and statistics thus provide a stable descriptive basis for the interpretive and pedagogical discussion that follows.

5. Discussion

This section interprets the cohort-level findings in architectural and pedagogical terms, and reflects on their implications and limits.

5.1. Edge, Elevation, and Prospect as a Teachable Heuristic

At cohort scale, the nucleus, spine, and underused zones make visible a siting logic that architectural theory often describes but rarely quantifies. Phenomenological accounts emphasize edges, thresholds, and horizons as anchors of meaning [1]; landscape readings of prospect and refuge stress how defended edges, benches, and long views structure perception and use [2,3]; and morphological work shows how linear terraces and walls organize co-presence and movement [4,11,16,22].

In this studio, the defended wall and upper terrace instantiate these ideas in a compact form. The building nucleus emerges where three demands coincide:

- i

- shelter and thickness from the wall,

- ii

- elevation and continuity from the bench, and

- iii

- prospect toward the ocean.

The empirical finding that roughly one fifth of all building mass falls inside a narrow band that occupies less than three percent of the admissible field, with odds ratios far above one, is one way of quantifying this convergence. The cohort could, in principle, have scattered mass across multiple benches. Instead, most projects choose to “lean” on the wall–terrace interface. The permutation results suggest that this is not just a trivial reflection of “build high when you can,” because elevation-stratified nulls still yield mean distances and overlaps far from the observed values (Section 4.2). What matters is not elevation alone, but elevation anchored to a specific linear edge.

This observation does not claim that there is a single correct placement. Rather, it supports the idea that edge–elevation–prospect constitutes a robust heuristic for this type of defended coastal terrace: a default stance that many independent designers converge on when given the same ground condition and program. Making this heuristic explicit, testable, and falsifiable is one of the main architectural contributions of the study. Instead of invoking the wall, bench, and view only in narrative, we show where, and how consistently, they carry building mass in a real cohort.

In this sense, the statistical descriptors do not replace architectural judgment; they simply make visible, at cohort scale, how consistently students enact siting logics that architects already recognize in words and sketches.

5.2. Minority Solutions, Coherence, and Connective Grammar

The strong convergence around the nucleus could tempt a prescriptive reading: that anything outside the prior band is inferior. The detailed path analysis and the identification of locally dominant connectors complicate this view.

Global building statistics say little about how minority placements keep or lose coherence. The salience-based path lens [16,22,29] shows that several projects with centroids downslope or seaward nonetheless maintain a clear relationship to the defended edge and the upper-terrace spine. They do so by investing in a small number of decisive stitches and gateways that recover access, prospect, and legibility. These connectors act as “structural words” in the site’s circulation grammar.

This has two consequences for how we read alignment with the expert prior. First, it shows that coherence is not synonymous with coincidence. A project can diverge from the prior polygon and still share the underlying edge–bench–prospect logic if it builds a robust connective spine back to the nucleus region. Second, it sharpens the distinction between exploratory divergence and noisy dispersion. Some lower or promontory-led sitings are clearly deliberate counter-examples: they trade off construction complexity and exposure against distinctive experiential sequences, while staying structurally tied to the defended edge. Others simply diffuse mass across benches without a clear connective strategy, making access harder to read.

By separating placement and connectivity, the framework helps tutors and students move beyond binary judgments of “good” versus “bad” siting. It becomes possible to say: “This project chooses a riskier bench, but its connectors are strong enough to keep the ensemble legible,” or “This scatter across levels does not yet achieve a coherent spine.” Minority intelligence, in this sense, is recognized and articulated rather than lost in averages.

5.3. Implications for Studio Teaching

The findings speak directly to how siting is taught and discussed in design studio. In many architectural schools, siting remains largely tacit, negotiated through desk crits and reviews in which the emphasis falls on individual projects [7]. Students see where each peer places the building but seldom see the cohort pattern. As a result, it is difficult to talk collectively about what the group did with a site, which parts of the field remain unexplored, or how divergent solutions relate to shared heuristics.

The protocol used here suggests three concrete pedagogical affordances:

- Making cohort patterns visible: Heatmaps and nuclei reveal how much of the admissible field the cohort actually used, where buildings tend to land, and which terraces remain untested. This enables tutors to shift from anecdotal impressions (“everyone is on the wall”) to auditable evidence (“about 20% of mass falls in 3% of the grid; the lower bench is barely used”). Such evidence can ground discussions about risk, comfort zones, and missed opportunities.

- Naming siting families: The four families identified in focus–spread–breadth space offer a compact vocabulary for studio: deep anchor, extended arm, fragmented benches, and prospect-led stance. Rather than treating each project as sui generis, tutors can use these families as scaffolds: “You are closer to the extended arm type; what would it mean to commit more to the spine?” or “This fragmented bench scheme has the risks of Type III but not yet its connective strengths.” The labels are descriptive, not evaluative, and can help students situate their work in a shared space of options.

- Separating heuristics from prescriptions: The expert prior is deliberately framed as an experience-based hypothesis that can be tested against the cohort rather than imposed on students. In a prospective setting, tutors could show earlier cohorts’ nuclei and connectors as “what tends to happen here” and then invite deliberate alignment or challenge. This supports metacognitive reflection—students can ask not only “Where did I put it?” but also “Which heuristic was I following, and why?”

Importantly, none of these uses require students to manipulate statistical machinery.

The grid, nuclei, and families are presented in the same visual and spatial terms they already use in drawings. The analytical apparatus stays backstage; what comes to the foreground are discussable siting structures.

5.4. From Studio Evidence to Early-Stage Practice

While the empirical material comes from a single studio cohort, the reasoning has implications beyond education. Siting decisions in practice are often made under time pressure and subject to multiple stakeholders, regulations, and engineering constraints [19,20,21]. In such contexts, rules of thumb—“stay on the bench,” “hug the defended edge,” “keep one clean ridge crossing”—play a crucial role, but they are rarely documented, re-examined, or adapted as conditions change.

The present framework suggests that it is possible to move toward lightweight, auditable siting briefs that capture this experiential knowledge without over-automating it. A designer or planning authority could, for instance, define a prior band and a small set of descriptors for a new headland, based on precedent and on expert reading. Early-stage options could then be compared not only visually but also in terms of their distance to, or deliberate deviation from, these priors.

Such use would not replace judgement. It would make explicit which options work with—or against—established heuristics, and at what structural cost. In projects with public accountability, this may help articulate why certain placements are defended: not as idiosyncratic preferences, but as consistent responses to edge, elevation, and prospect that have been observed across multiple cohorts or sites.

5.5. Validity, Limits, and Future Work

The study’s design is intentionally modest and carries several limits that constrain interpretation.

First, it is post hoc and observational, not experimental. We analyze an existing cohort after the fact; we do not manipulate siting feedback or randomly assign students to conditions. As a result, we can describe where and how the cohort tends to build and how this relates to a pre-specified expert hypothesis, but we cannot claim causal effects of any intervention or feedback protocol. The permutation tests provide exact answers to specific “closer than chance?” questions [25], but they do so on a fixed cohort and site.

Second, the study is based on a single site and one cohort of 22 projects. The defended coastal terrace is a strong formal archetype, but it is not representative of all sites, and the studio has its own culture, guidance, and peer dynamics. The scope of inference is therefore analytic rather than statistical: we generalize to a family of steep coastal or fortified terrace sites with a clear upper bench, a recognizable crest line, and at least one strong prospect towards landscape or water, rather than to an abstract population of all possible sites. Within that family, the regularities we observe (nucleus, spine, connectors, families) are internally coherent and robust to methodological variations (grid resolution, priors, seed choice), but they still need to be tested on other terrains and with other groups before any broader generalization is attempted.

Third, the expert prior is a single-expert construction. It captures one practitioner’s reading of edge–bench–prospect on this site. We treat it as an explicit, falsifiable hypothesis rather than as a normative rule, but the fact remains that other architects might draw a different prior band or place more emphasis on alternative logics (for example, cross-ridge visibility or lower-bench wind protection). Extending the framework to multi-expert priors, or to priors derived from historical ensembles, is a natural next step.

Fourth, the grid representation is deliberately coarse. A 2.5 × 2.5 m cell is more meaningful than a one-meter raster for architectural reading, but it inevitably abstracts over fine-grained differences in edge condition, micro-topography, and façade articulation. The aim here is to reveal cohort-scale siting patterns, not to resolve detailed tectonic or microclimatic effects. Combining this approach with higher-resolution environmental simulations or visibility analyses would sharpen insights at smaller scales.

Despite these limits, the combination of a transparent workflow, explicit priors, permutation-based inference, and a full replication pack [5,19,25] provides a reproducible baseline for future work. A natural extension is a prospective, multi-studio design in which some cohorts receive siting feedback based on previous years’ patterns, while others follow conventional teaching, and where hypotheses are pre-registered in advance. Another is a multi-site comparison, examining whether similar nuclei and families appear in other edge–elevation–prospect contexts, such as river bluffs, urban ramparts, or cliffside campuses. In both cases, the core idea remains the same: to bring siting heuristics out of the realm of tacit opinion and into a space where they can be seen, compared, tested, and taught.

A systematic evaluation of learning outcomes and transfer across studios is deliberately left outside the scope of this article and will be addressed in subsequent work, where the present protocol will be used prospectively as part of a broader pedagogical study.

6. Conclusions

This study treated a second-year architecture studio as an analyzable cohort, remapping 22 proposals for a compact sports facility on a defended coastal terrace onto a neutral grid and encoding them as buildings and paths. A site-specific expert prior formalized an experience-based siting hypothesis around the defended wall and upper terrace, and alignment was quantified with simple, interpretable descriptors and permutation-based tests. Within this post hoc, observational design, three empirical regularities emerged: siting is strongly non-uniform and concentrates in an edge–elevation–prospect nucleus; cohort placements align with the expert prior far more than expected under null models that respect the site’s geometry and elevation; and projects organize into a small number of readable siting families rather than a diffuse cloud of unrelated solutions.

Architecturally, the work shows that familiar siting logics on stepped coastal sites—leaning on a defended edge, staying on the upper bench, and working with long views—can be made explicit, encoded, and tested at cohort scale without collapsing design into a single correct answer. Minority solutions that depart from the nucleus remain coherent when they invest in a strong connective grammar of spines, stitches, and gateways, while more scattered schemes expose the cost of ignoring this structure. The protocol thus distinguishes between convergence around a robust heuristic and the diversity of principled departures from it, giving tutors and students a language to discuss both.

Methodologically and pedagogically, the main contributions are threefold. First, the study offers a lightweight, reproducible workflow that turns studio outputs into cohort-scale siting evidence, accompanied by a replication pack that makes every step auditable and portable across sites and institutions. Second, it frames the expert prior as an explicit, falsifiable hypothesis rather than a normative rule, showing how alignment and divergence can be quantified without prescribing form. Third, it proposes a metacognitive scaffold for architectural education in which cohorts can see where they tend to build, which parts of a site remain unexplored, and how their projects fall into a small set of siting families that can be named and debated.

These conclusions are necessarily bounded by the specificity of a single site, cohort, and expert prior. Even so, they show that siting heuristics in architecture can move from tacit intuition to explicit, testable patterns, and that these patterns can inform both studio teaching and early-stage practice. Extending this approach to other terrains, briefs, and schools, and to prospective studies where siting feedback is openly discussed with students, would turn individual studios into a cumulative evidence base on how architects learn to place buildings in complex landscapes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings15244528/s1: Tables S1–S8, which report coverage and underuse statistics, top-usage cells, prior enrichment and odds ratios, centroid descriptors, local salience diagnostics, typical and divergent siting cases, and the distribution of total building area for the 19-project subset discussed in the main text.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M.; methodology, N.M.; software, V.M.; validation, N.M.; formal analysis, V.M. and N.M.; investigation, N.M. and V.M.; data curation, N.M.; visualization, V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.; writing—review and editing, N.M.; supervision, N.M.; project administration, N.M.; funding acquisition, N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), Lisbon, Portugal, under the co-financed contract CEECINST/00112/2018/CP1530/CT0014.

Data Availability Statement

All data and code used in this study are openly available at Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17433474. The replication pack includes configuration files, machine-readable CSVs for all descriptors, the admissible mask and expert prior, sample B/P encodings, permutation outputs, and a SHA-256 manifest. Key numerical summaries are also provided as Supplementary Tables S1–S8 with the journal, while full visual vignettes and figure panels remain available in the open replication pack.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participating students and colleagues for their constructive discussions. Figure 4 is reproduced with permission from the Cascais Municipal Archive; photograph author and date unknown. A large language model was used to assist with language editing and organization only. Data coding, statistical analyses, figures, and all substantive interpretations were produced and checked by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

B = Buildings (mass); P = Paths; OR = odds ratio; CLES = common language effect size; BCa = bias-corrected and accelerated (bootstrap).

References

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- McHarg, I.L. Design with Nature, 25th Anniversary ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, N.; Gomes, J.C.; Urbano, P.; Duarte, J.P. A Land Use Planning Ontology: LBCS. Future Internet 2012, 4, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, B. How Designers Think: The Design Process Demystified, 4th ed.; Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhou, M. Urban human activity density spatiotemporal variations and the relationship with geographical factors: An exploratory Baidu heatmaps-based analysis of Wuhan, China. Growth Change 2020, 51, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.; Beirão, J.N.; Montenegro, N.; Duarte, J.P. On the discovery of urban typologies: Data mining the many dimensions of urban form. Urban Morphol. 2012, 16, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, F.; Ortner, T.; Moreira, G.; Hosseini, M.; Vuckovic, M.; Biljecki, F.; Silva, C.T.; Lage, M.; Ferreira, N. The State of the Art in Visual Analytics for 3D Urban Data. Comput. Graph. Forum 2024, 43, e15112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, N.; Beirão, J.; Duarte, J. Describing and locating public open spaces in urban planning. Int. J. Des. Sci. Technol. 2012, 19, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro, N. Integrative Analysis of Text-To-Image Ai Systems in Architectural Design Education: Pedagogical Innovations and Creative Design Implications. J. Archit. Urban 2024, 48, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Xie, Z. Optimization of Urban Shelter Locations Using Bi-Level Multi-Objective Location-Allocation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borba, B.F.d.C.; de Gusmão, A.P.H.; Clemente, T.R.N.; Nepomuceno, T.C.C. Optimizing Police Facility Locations Based on Cluster Analysis and the Maximal Covering Location Problem. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2022, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M.; Jacobson, M.; Fiksdahl-King, I.; Shlomo, A. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Porta, S.; Crucitti, P.; Latora, V. The network analysis of urban streets: A primal approach. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2006, 33, 705–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.; Weng, D.; Liu, S.; Tian, Y.; Xu, M.; Wu, Y. A survey of urban visual analytics: Advances and future directions. Comput. Vis. Media 2023, 9, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longley, D.W.; Goodchild, P.A.; Maguire, M.F.; Rhind, D.J. Geographic Information Science and Systems, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro, N.; Gomes, J.; Urbano, P.; Duarte, J. An OWL2 land use ontology: LBCS. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.T. The Hidden Dimension; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 1992; p. 217. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Hidden_Dimension.html?hl=pt-PT&id=p3g0ngEACAAJ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Turner, A. From axial to road-centre lines: A new representation for space syntax and a new model of route choice for transport network analysis. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2007, 34, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, G.; Ha, J. Resilient by design: Simulating street network disruptions across every urban area in the world. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 182, 104016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigdinos, S.; Salamouras, G.; Chatziioannou, I.; Bakogiannis, E.; Nikitas, A. A worldwide review of formal national street classification plans enhanced via an analytical hierarchy process: Street classification as a tool for more sustainable cities. Cities 2024, 154, 105371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, P. Permutation Tests: A Practical Guide to Resampling Methods for Testing Hypotheses; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevtsuk, A.; Kalvo, R. Patronage of urban commercial clusters: A network-based extension of the Huff model for balancing location and size. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2018, 45, 508–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Claramunt, C. Topological analysis of urban street networks. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2004, 31, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. Better bootstrap confidence intervals. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1987, 82, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crucitti, P.; Latora, V.; Porta, S. Centrality measures in spatial networks of urban streets. Phys. Rev. E 2006, 73, 36125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, D.L.; Bouldin, D.W. A cluster separation measure. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1979, PAMI-1, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).