Abstract

The stability of rock masses in karst regions is critically influenced by the coexistence of karst caves and joints. This study investigates the mechanical behavior, energy evolution, and failure modes of large-scale (1 m3) rock-like specimens containing a 30 cm karst cave and joints at varying positions and dip angles (α). The results indicate that joint dip angles between 30° and 60° define a critical strength deterioration zone, with the minimum peak strength (44 MPa, 24.1% lower than the 0° specimen) occurring at α = 60°. Side-positioned joints induced greater strength weakening than top-positioned ones. Energy analysis revealed that α significantly governs energy accumulation and dissipation; the elastic energy minimum was also observed at α = 60°. Specimens with side-positioned joints exhibited higher energy dissipation efficiency, promoting extensive crack propagation. The research results suggest that in engineering, are as with joints inclined at 30–60° should be avoided as much as possible, and the energy-dissipating capacity of near-vertical (~90°) joints should be utilized to enhance the stability of the rock mass in karst tunnel engineering.

1. Introduction

China’s urban rail transit network has expanded rapidly and now reaches world-leading levels. This expansion has increased demand for underground space. National development strategies require extensive infrastructure to traverse complex karst regions [1]. Karst rock masses are commonly influenced by surface water and groundwater and are characterized by caves, fissures, and joints [2,3]. Chemical and mechanical interactions between rock mass and water promote the development of fissures, fractured zones, and caves, which reduce rock mass stability [4]. Tunnel construction in karst regions often faces a heightened risk of geological hazards, including ground subsidence [5], and poses substantial challenges to engineering works [6]. Consequently, a thorough understanding of karst features is crucial for evaluating rock mass stability and designing appropriate engineering structures.

Karst landforms are widespread in China. Large karst areas occur in Guizhou, northern Guangdong, Guangxi, southern Sichuan, and eastern Yunnan. These regions account for approximately 30% of southwestern China and constitute one of the world’s most representative karst zones. Karst caves are three-dimensional defects within the rock mass. They increase construction risk and markedly affect the mechanical properties of rocks [7,8]. Karst collapse results from instability and failure of overlying soil under loading. Different karst collapse mechanisms correspond to different stress states. Romanov et al. [9] used two-dimensional karst evolution models and simplified three-dimensional Discrete Element Method (DEM) models to clarify that dissolution controls the development of collapse vulnerabilities, while mechanical collapse occurs over short periods. Yi and Zhang [10] found that rock mass stress in tunnels increases with cave span and decreases with the distance between caves. Wang et al. [11] identified cave span as the main influencing factor, followed by the degree of filling, and the height-to-span ratio had the least influence. Wang et al. [12] reported a positive correlation between horizontal load and cave length and a negative correlation between vertical load and roof thickness. In addition, cave height had a relatively small impact on the load-bearing capacity. Huang et al. [13] derived an analytical expression for the collapse surface using variational methods. They also proposed a formula for the minimum safe roof thickness required to prevent cave collapse.

Joints increase the diversity and complexity of fracture patterns in rock masses and are the primary factor that reduces their overall strength. Therefore, analysis of the geometric and mechanical properties of joints is essential for rock engineering stability. Jaeger [14] was the first to quantify the influence of joint dip angle on rock strength using the single weak plane theory. The findings revealed that rock strength attained a minimum when the angle between a joint plane and the direction of maximum principal stress approached the material’s internal friction angle. This critical angle is known as the “most dangerous joint dip angle”. Bandis and Stavros [15] proposed the size effect theory for joint mechanical behavior and reported that the influence of joint dip angle increases nonlinearly with rock scale. Li et al. [16,17] confirmed this discovery using discrete element simulations. They concluded that, for large-scale rock masses containing multiple joint sets, spatial variability in joint dip angles causes stress redistribution and local strain concentration. These effects significantly reduce the macroscopic strength. Fan et al. [18] investigated crack formation in red sandstone containing discontinuous joints with different dip angles under uniaxial compression. They also found that the final failure mode depends on the pre-existing crack angle. Uniaxial compressive strength followed an approximate U-shaped trend: it first decreased and then increased as joint dip angle increased [19]. When the joint dip angle ranged from 30° to 60°, shear slip along the joint surface was the dominant failure mode. Failure likelihood peaked when the joint was oriented at 45° to the loading direction. When the dip angle was greater than 75°, the failure mode shifted to tensile fracture across the joint, and the rate of energy release significantly increased [20]. However, existing models generally neglect the stress perturbation caused by karst caves [21]. In practice, circumferential tensile stress around the karst caves may activate originally stable high-dip joints (θ > 60°) and induce asymmetric failure [17,22].

Karst caves and joints commonly coexist and interact in natural rock masses. Existing studies have improved understanding of how individual caves and joints affect the mechanical behavior of rock masses. However, most investigations focus on the impact of geometric characteristics of a single cave and joint on rock masses. Experimental work is often limited to small specimens and employs loading protocols that differ from field conditions. Although a few studies have begun to explore the coupling effect of holes (or caves) and joints [23], they primarily focus on damage evolution and crack propagation, often neglecting the crucial energy dissipation mechanisms. Moreover, the use of smaller-scale models limits their direct applicability to large-scale engineering scenarios. As rock engineering advances into deeper and more geologically complex environments, research must transition from single-factor analyses to systematic studies that incorporate coupled multi-field interactions. Current approaches remain constrained by single-defect theory and lack a three-dimensional model that integrates cave diameter, joint dip angle, and energy distribution. To bridge this gap, we first embedded fixed-size karst caves in rock mass specimens and varied joint position and dip angle to decouple the coupled cave-joint systems. Subsequently, we evaluated how cave presence and joint dip angle jointly influenced the strength, energy dissipation mechanisms, and failure modes of rock mass. The findings provide a scientific basis for engineering survey and design. They also support safety and more cost-effective engineering decisions.

2. Experimental Design and Methods

2.1. Specimen Preparation

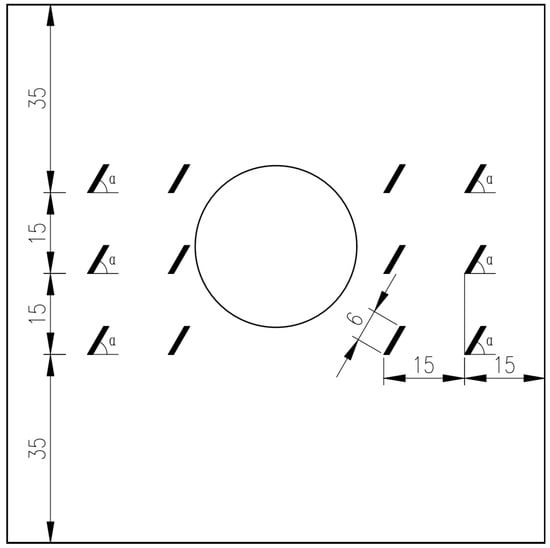

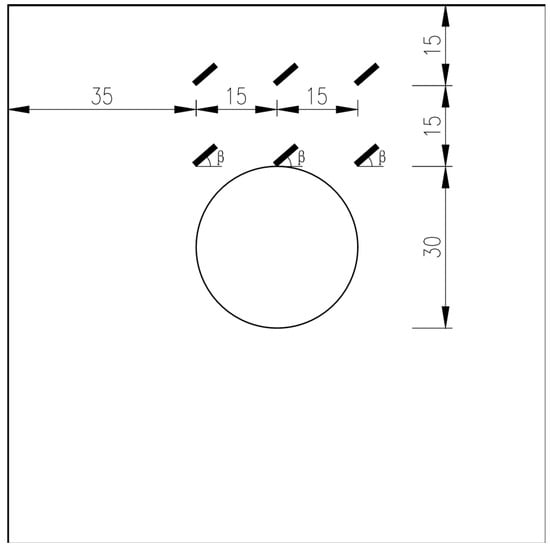

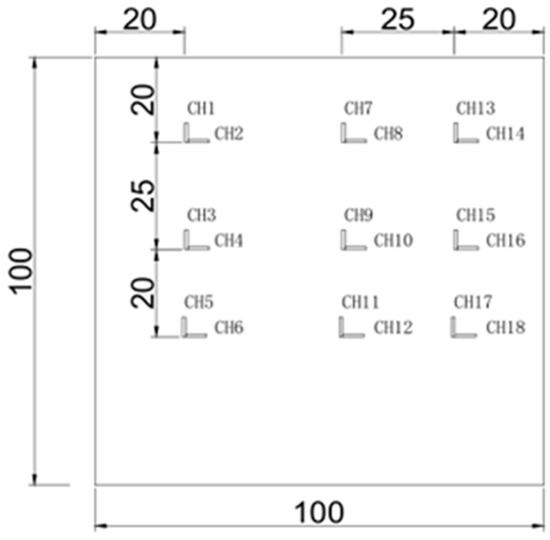

This experiment was conducted for a bridge site in the karst region of Baiyun District, Guangzhou City. Parameters for different rock and soil layers were classified and statistically analyzed following a review of geological exploration reports. Representative layer parameters were selected as prototype values for the models. This experiment adopted a holistic modeling scheme. It drew on Zhang’s [24] center symmetry model, Lei’s [25] bottom arch cave model, and Xu’s [26] simply supported beam model for beam-and-slab structure. The designed scheme aimed to more accurately reproduce the cave formation process and the associated surrounding pressure conditions. Specimens containing caves and joints with varying positions and dip angles were fabricated. Their geometric details are displayed in Figure 1 and Figure 2. The concrete mix ratio was cement: sand: water: gypsum = 200:600:120:80 (The concrete mix proportion for this test was determined based on prior experiments) [27]. Materials used to simulate karst caves and joints were fixed at designated positions before they were poured into the model box. Expandable Polystyrene (EPS) spheres were used to simulate karst caves. When the specimen reached initial setting, a dissolution agent was injected to form internal karst caves. Steel plates penetrating the model box were installed to simulate joints. After the specimen reached final setting, the steel plates were removed to create penetrating cracks. Figure 3 shows the experimental procedure. A total of eight cubic concrete specimens (100 × 100 × 100 cm) were produced. Other test parameters are listed in Table 1, where the T and S denote joints located at the top and on both sides, respectively, while the “0” represents that the angle between the joint and the horizontal direction is 0°.

Figure 1.

Side-positioned joints with different dip angles.

Figure 2.

Top-positioned joints with different dip angles.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of specimen pouring: (a) Weighing and mixing; (b) Pouring; (c) Vibration and compaction; (d) Demolding.

Table 1.

Specimen parameters.

2.2. Model Parameters and Experimental Protocol

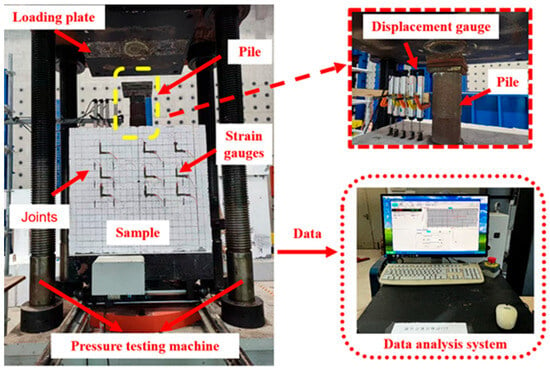

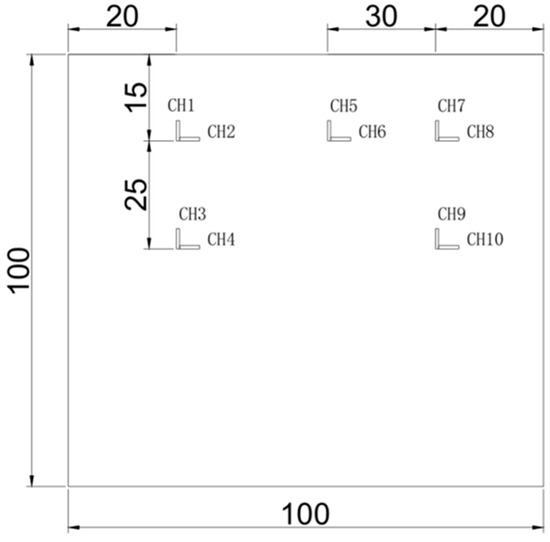

The experiment was conducted at the Seismic Center of Guangzhou University using a microcomputer-controlled electro-hydraulic servo pressure testing machine (see Figure 4). The apparatus offers a maximum test force of 1000 kN and a maximum axial displacement of 300 mm. The system enabled synchronous acquisition of displacement, strain, and load. The specimen surface was pre-coated with putty powder and marked with orthogonal ink lines at 5 cm intervals to form a grid for crack observation. The load was transmitted to the specimen via a circular steel plate with a diameter of 20 cm and a thickness of 3 cm, which was placed on the top surface of the specimen. Several strain gauges were attached to the specimen surface to record strain data (see Figure 5 and Figure 6). A displacement-controlled loading method was employed. First, each specimen was preloaded to 1/50 of the estimated failure load. When the preload was reached, the strain gauges and displacement transducers were checked for proper operation. Subsequently, the preload was unloaded to zero, and the specimen was reloaded. The formal loading was performed at a constant displacement rate of 0.18 mm/min.

Figure 4.

Microcomputer-controlled electro-hydraulic servo pressure testing machine.

Figure 5.

Layout of strain gauges for specimens containing top-positioned joints.

Figure 6.

Layout of strain gauges for specimens containing side-positioned joints.

In the energy analysis, two key assumptions were adopted: (1) the interfacial friction between the specimen and loading plates was neglected, and (2) the specimen was treated as a closed system. These are conventional in this field of study. The potential influence of interfacial friction on the energy calculation was evaluated based on pre-test calibration, confirming that the introduced relative error is less than 5%. Furthermore, the closed-system assumption holds under the stable laboratory conditions (constant temperature and humidity) maintained throughout testing, which prevented significant mass transfer or additional energy losses. These considerations ensure the rigor of the subsequent energy analysis.

3. Experimental Observations and Analysis

3.1. Stress–Strain Curves of Jointed Rock Masses Containing Karst Caves

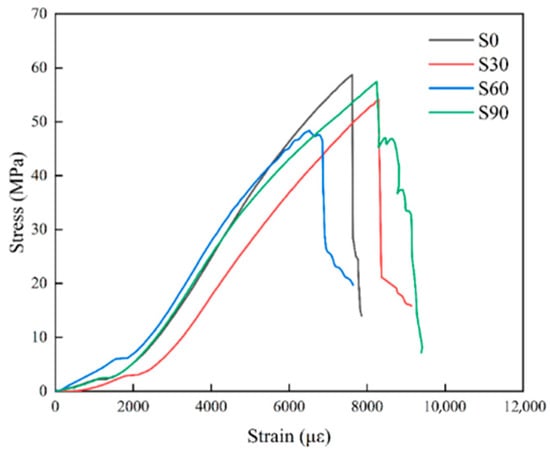

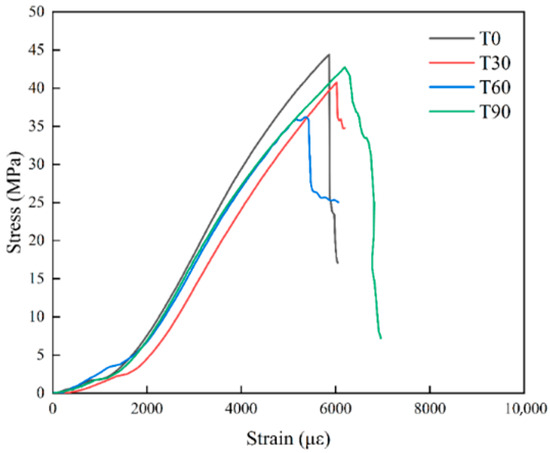

Figure 7 and Figure 8 present the stress–strain curves for specimens containing joints with different positions and dip angles. The curves revealed three stages: an initial gradual increase, a significant increase, and a sudden decrease.

Figure 7.

Stress–strain curves of specimens containing top-positioned joints.

Figure 8.

Stress–strain curves of specimens containing side-positioned joints.

The influence of joint dip angle on peak stress and residual strength varied across specimens containing top-positioned joints. The specimen with a 0° joint exhibited the highest peak stress, 58 MPa. Since the joint hindered formation of a primary shear plane, specimen failure was dominated by axial splitting. Post-peak stress dropped sharply due to concentrated energy release. This observation indicted abrupt stiffness loss and brittle fracture. Energy release was most intense and stress decayed rapidly to extremely low levels. The specimen exhibited limited capacity for plastic energy dissipation and did not develop a stable residual strength plateau. These features—high strength, low ductility, and sudden failure—are characteristic of brittle instability and prevented a stable transition to the ultimate state. This occurred because the joint was perpendicular to the main loading direction and therefore could not form an effective slip path. Consequently, internal energy was not dissipated, and cracks rapidly propagated along the axial direction after peak load.

In contrast, specimens T60 and T30 were more susceptible to shear slip along pre-existing joint surfaces. The 60° specimen exhibited the lowest peak stress, 48 MPa. The 30° specimen reached a peak stress of 54 MPa. Both groups showed a transition from strong brittle behavior to pronounced ductile failure. The stress–strain curve displayed a combined “fracture-sliding” trend. This indicated that a continuous failure path did not form.

The joint plane of the specimen T90 was aligned with the direction of the principal compressive stress, and its peak strength reached 57 MPa. This value was comparable to that of the 0° specimen. The post-peak stress drop was markedly more gradual. A sustained residual strength was observed, and crack propagation was stable. These effects produced peak attenuation, gradual energy release, and structural buffering capacity. Consequently, energy release during testing remained steady.

The combined effects of joint dip angle and joint arrangement produced pronounced differences in mechanical responses. Specimens containing side-positioned joints showed greater loss of structural integrity than those containing top-positioned joints. Peak strengths of specimens containing side-positioned joints across all dip angle groups decreased by an average of 20–25%. For example, the peak strength of the 0° specimen declined from 58 MPa to 44 MPa. This indicated that a larger number of joints promoted crack penetration and accelerated strength degradation. Side-positioned joints were much more likely to intersect the principal stress path. This occurred because top joints could cause local crushing, while global failure still depended on crack propagation through the specimen midsection. Thus, top joints produced only minor local weakening and had limited effect on the overall load-bearing capacity. Consequently, the failure mechanism shifted from “stress-controlled” to “joint-controlled.” The structural response to external loads transitioned from stable axial compression to complex combinations of shear fractures. From a design and material-control perspective, penetrating joints oriented at 30–60° to the direction of the principal compressive stress should be avoided. Joints in this angular range generate large shear stress components, promote joint surface cutting, and increase the risk of shear slip instability.

3.2. Variation in Ultimate Load-Bearing Capacity of Jointed Rock Masses Containing Karst Caves

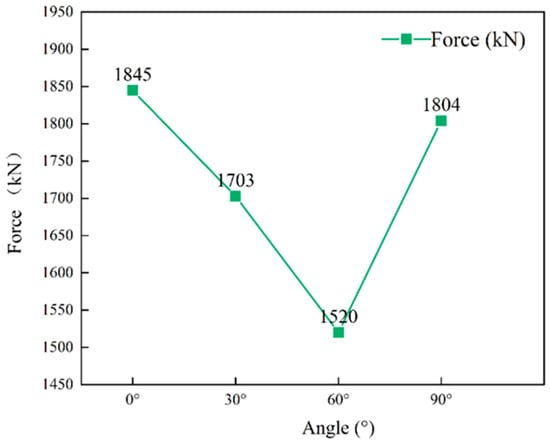

We obtained the ultimate load-bearing capacity (σu) for specimens with α = 0–90° from their stress–strain curves. Figure 9 presents the results for specimens containing joints located at the karst cave roof. Figure 10 shows the results for specimens containing joints positioned on both sides of the karst cave. These plots were used to assess the influence of joint distribution on the σu of karst cave roof.

Figure 9.

Variation in σu for specimens containing top-positioned joints.

Figure 10.

Variation in σu for specimens containing side-positioned joints.

Roof joints strongly influenced the specimen’s σu. As α increased from 0° to 90°, the σu followed a pronounced V-shaped trend (see Figure 9). When α was 0°, σu was the highest at 1845 kN, because a continuous load path inhibited crack propagation. As α increased to 30° and 60°, σu decreased to 1703 kN and 1520 kN, respectively. The 60° specimen had the lowest σu, which represented a decrease of approximately 17.6% compared to the 0° specimen. α = 60° most favored shear-slip failure and posed the greatest risk of overall instability. Although the data intervals are set at 30°, the overall trend is consistent with previous studies on jointed rock masses. For instance, Fan et al. [18] conducted uniaxial compression tests on sandstone with non-penetrating flaws and observed that strength recovery beyond α = 60° is continuous and smooth, without evidence of anomalies near α = 75°. In their study, the strength increased gradually from α = 60° to α = 90°, attributed to the reduced shear stress component and enhanced interlocking of rock bridges as the joint inclination approaches vertical. When α reached 90°, σu rose to 1804 kN, which approached the initial level. These results indicated that α significantly affected the macroscopic mechanical properties and failure modes of specimens.

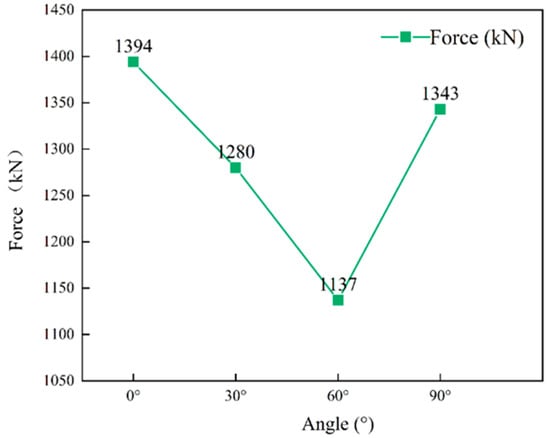

Figure 10 presents the experimental results for specimens containing side-positioned joints with different α. Similarly, the specimens’ σu first decreased and then increased as the α increased. This trend reflected the weak load-bearing structural effect and the stress disturbance control mechanism induced by the geometric configuration. At α = 0°, σu reached a maximum of 1394 kN. The configuration of joints parallel to the load direction minimized interference with the load path and normal stiffness. Consequently, axial stress was transmitted most effectively. Increasing α to 30° reduced σu to 1280 kN (≈8.2% reduction). This change indicated a shift toward a shear-dominated force-transfer mechanism. Consequently, the force direction became more sensitive to displacement changes, and local micro-slip and interface friction intensified. These effects diminished the structure’s ability to transfer load along the primary loading direction. The minimum σu (i.e., 1137 kN) occurred at α = 60°. This value represented a decrease of 18.4% compared to that observed at α = 0°. Consequently, this configuration substantially weakened the overall structural strength. At α = 90°, the σu increased to 1343 kN, which approached the initial level. In this configuration, the joint plane was oriented perpendicular to the principal stress axis. Although the joint interface’s overall shear resistance was reduced, the absence of effective sliding paths preserved a high σu.

A comparison of Figure 9 and Figure 10 revealed that, for a given α, specimens containing top-positioned joints exhibited higher σu than specimens containing side-positioned joints. When joints were located at the roof, the roof load was transferred downward through the intact rock mass beneath the cave. This established an effective load-transfer path. When joints were positioned on both sides, this path was disrupted and σu decreased. These results indicated that the σu of a karst cave roof depended on both cave size and the position of rock discontinuities. A high density of joints and fractures in the rock mass beneath the roof further reduced its overall load-bearing capacity and compromised the safety of pile foundations. Therefore, evaluations of karst cave roof load-bearing capacity must account for the presence and distribution of joints and fractures. Developing assessment methods that incorporate rock mass quality is essential to improve the safety of rock socketed piles in karst regions.

3.3. Calculation Method for Energy Loss

In energy calculations, the concrete specimen was treated as a single continuous medium, and the influence of interfacial friction was neglected. The specimen was assumed to be a closed system with no mass or energy exchange with the external environment. The specimen obeyed the first law of thermodynamics during compressive failure. All external work was supplied by the testing apparatus. The total strain energy (U) of the specimen equals the sum of the elastic strain energy (Ue) and the dissipated strain energy (Ud):

A systematic study was conducted on the load-bearing capacity, energy dissipation characteristics, and failure modes under different testing conditions. We computed U, Ue, and Ud from stress–strain curves of each specimen. These values were used to examine the relationship between mechanical response and energy dissipation [26]. We further assumed that no heat exchange occurred during deformation. Consequently, the total strain energy satisfied U = Ue + Ud:

Where U is the total strain energy (KJ/m3), Ue is the recoverable elastic strain energy, and Ud is the irreversible dissipated strain energy.

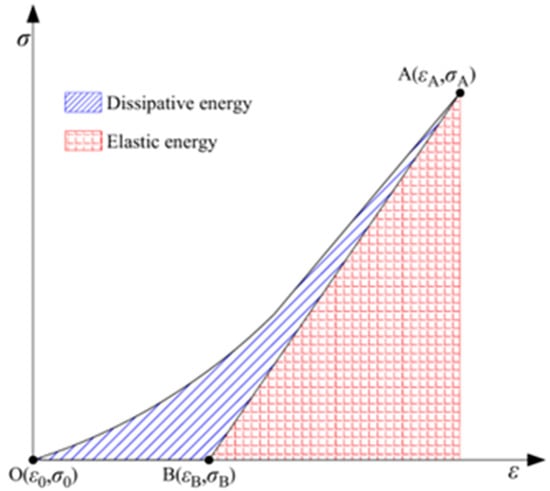

As depicted in Figure 11, the area under the stress–strain curve denotes the total strain energy U, the red shaded region represents the elastic strain energy Ue, and the blue shaded region denotes the dissipated strain energy Ud. Therefore, the total strain energy of the concrete specimen is given by [28]:

Figure 11.

Relationship between Ue and Ud.

According to Hooke’s Law, Equation (1) can be rewritten as:

There is σ2 = σ3 = 0 during uniaxial compression. Equation (2) can be simplified as follows:

3.4. Energy Evolution of Jointed Rock Masses Containing Karst Caves

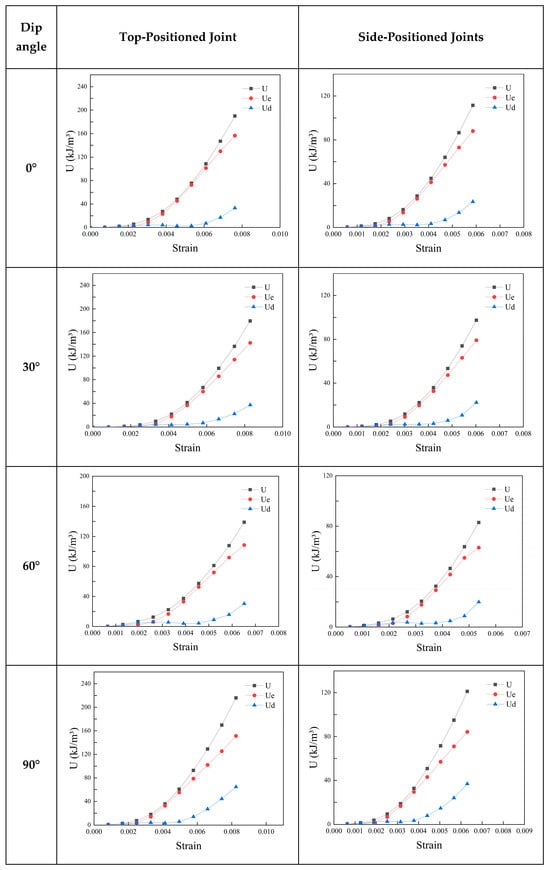

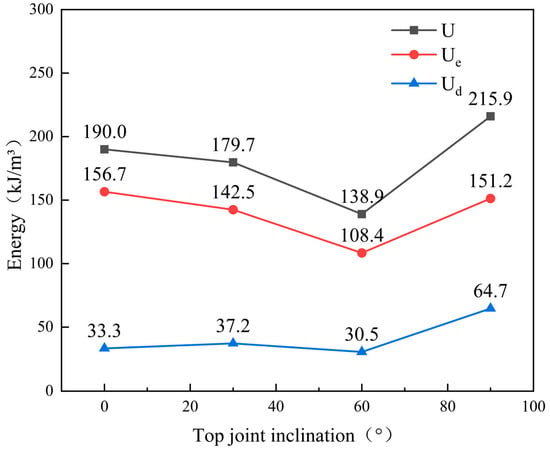

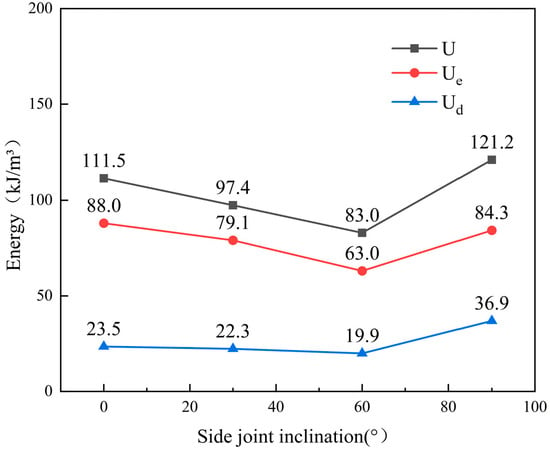

Figure 12 shows the energy evolution of specimens containing joints at different positions and dip angles. It was observed that the joint dip angle significantly influenced the energy accumulation path, the proportion of recoverable energy, and the post-peak energy dissipation capacity during uniaxial deformation. These findings reflected the mechanism by which different joint configurations governed deformation and damage.

Figure 12.

Energy evolution of specimens containing joints with different dip angles.

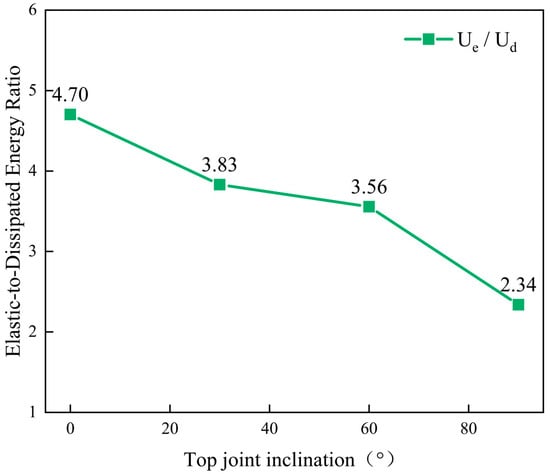

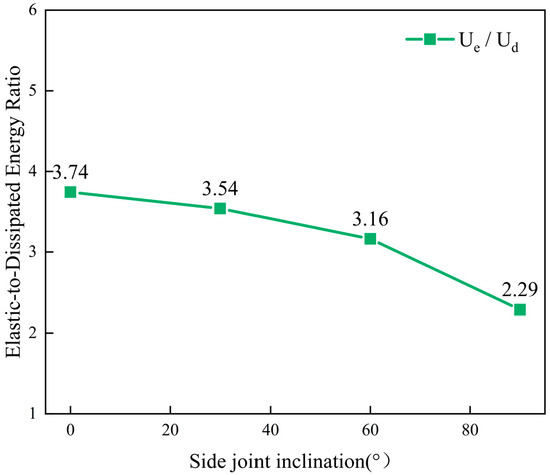

Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16 present the Ue/Ud ratios at peak load for each testing condition. A comparison revealed systematic differences between the two joint configurations. The differences occurred in three aspects: the range of energy absorption, the coordination between elastic and dissipative processes, and the activation of the energy consumption mechanism. Accordingly, we identified three primary mechanism differentiation characteristics: input capability, dissipation efficiency, and elastic-dissipated energy coordination.

Figure 13.

Peak energy for specimens containing top-positioned joints at different dip angles.

Figure 14.

Peak energy for specimens containing side-positioned joints at different dip angles.

Figure 15.

Peak Ue/Ud ratio for specimens containing top-positioned joints with different dip angles.

Figure 16.

Peak Ue/Ud ratio for specimens containing side-positioned joints with different dip angles.

(1) Specimens containing top-positioned joints absorbed more energy than those containing side-positioned joints. This trend held for all four joint dip angles. At α = 0°, the input energy of the specimens containing top-positioned joints was 190 kJ/m3, which was 1.7 times the 112 kJ/m3 measured for the specimens containing side-positioned joints. At α = 90°, the input energy of the specimens containing top-positioned joints reached 216 kJ/m3, which was substantially higher than the 121 kJ/m3 of the specimens containing side-positioned joints. These results indicated that the specimens containing top-positioned joints had a higher potential for energy accumulation under stable loading. This effect likely arose because the primary interference zone was located at the top. That location had a limited impact on the overall stress-transfer path and did not weaken the main load path. Consequently, specimens containing top-positioned joints exhibited higher load-bearing capacity and could withstand greater input energy.

(2) Specimens containing side-positioned joints generally exhibit a higher proportion of dissipated energy than those containing top-positioned joints. At α = 90°, specimens containing side-positioned joints achieved an energy dissipation ratio of 30%. Although the specimen T90 also exhibited a 30% energy dissipation ratio, its total energy input was greater. This indicated that the dissipation efficiency per unit input for specimens containing top-positioned joints did not increase proportionally with higher energy input. At α = 60°, specimens containing side-positioned joints again showed a higher energy dissipation ratio than those containing top-positioned joints. This indicates that the side-positioned joints played a more significant role in crack propagation during loading, leading to the formation of additional fractures near and around the jointed zones. This process consumed more input energy and disrupted the load-transfer paths, thereby reducing the load-bearing capacity.

(3) Regarding elastic-dissipated energy coordination, specimens containing top-positioned joints predominantly exhibited an elastic-dominant, poor-dissipation behavior across most joint dip angles. The Ue/Ud ratios for specimens containing top-positioned joints were 4.70, 3.83, 3.56, and 2.34, respectively, while those for specimens containing side-positioned joints were 3.74, 3.54, 3.16, and 2.29, respectively. These differences were notable. The results indicated that, although specimens containing top-positioned joints exhibited greater energy absorption capacity, the absorbed energy was difficult to release effectively. In contrast, the side-joint arrangement facilitated efficient energy release during the mid-to-late loading stage by generating localized multi-joint plane instability and associated dissipation zones. In the present study, the energy dissipation characteristics further support the monotonic recovery of strength in the range of 60° to 90°. both the total energy input and the proportion of dissipated energy increase steadily with α, particularly from 60° to 90°. The Ue/Ud ratio decreases consistently across this range, indicating a progressive enhancement in energy dissipation capacity without intermediate fluctuations. This smooth transition in energy behavior aligns with the mechanical strength recovery, reinforcing that the 30° interval is sufficient to capture the essential characteristics of the V-shaped trend.

3.5. Failure Modes of Jointed Rock Masses Containing Karst Caves

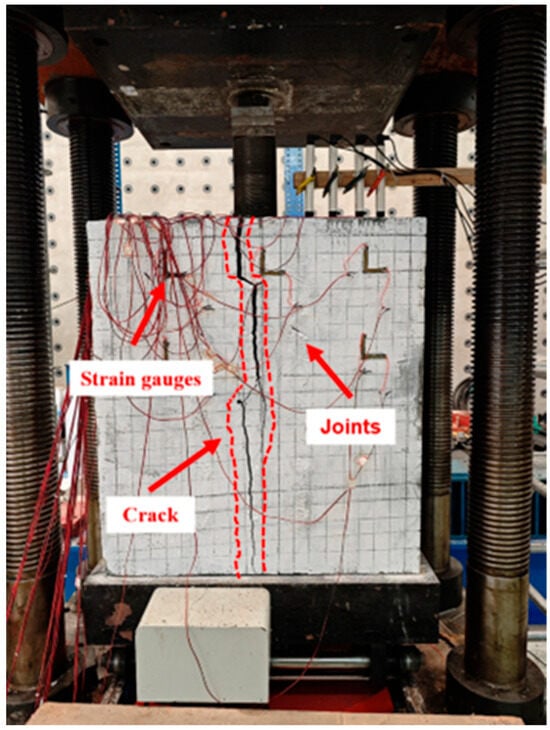

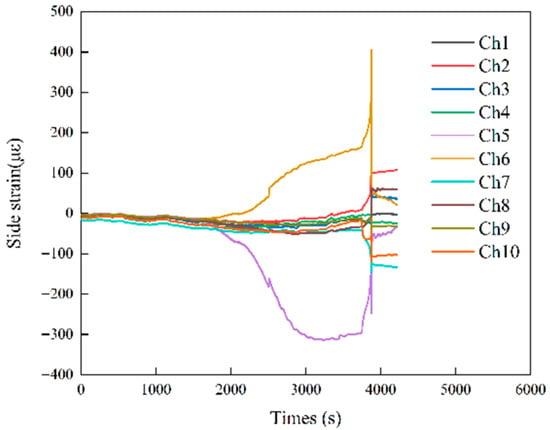

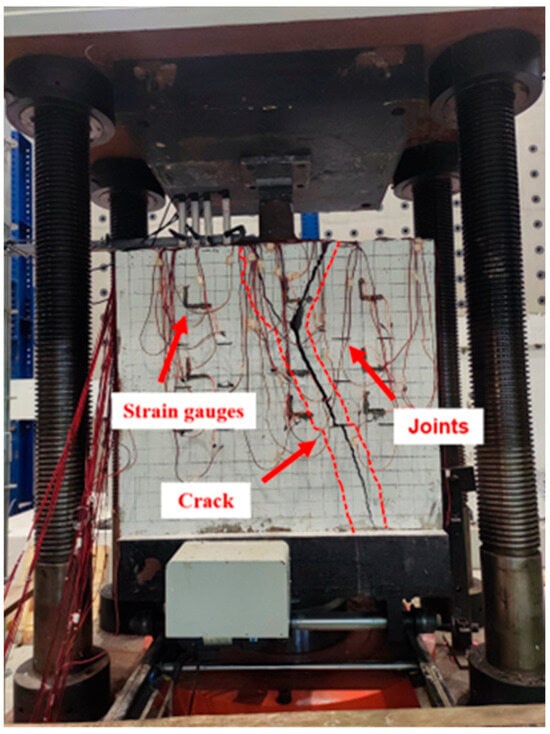

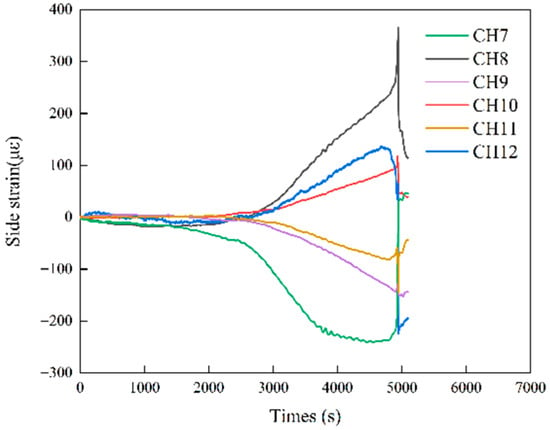

This study designed loading tests for various joint configurations with different dip angles and arrangements. For each configuration, a dense array of strain gauges was installed in critical regions to capture crack evolution. Given the extensive experimental dataset, and to ensure a systematic and readable analysis, the failure modes of the two most representative configurations—T60 and S0—were selected for presentation. These configurations represent the cases with the lowest load-bearing capacity for top-positioned joints and the highest for side-positioned joints, respectively, thus encompassing the primary failure patterns observed across all specimens.

The specimen T60 exhibited initial crack guidance and progressive interface damage during loading. The central region at the specimen’s end served as the crack-initiation site due to a marked initial stress concentration. The crack slightly deviated along the joint direction during the early stage. The joint partially guided this behavior. Since the joint was confined to specimen’s top region, it could not sustain a continuous deviation. The crack returned to the central axis and propagated downwards, which eventually formed secondary axial cracks and a main crack that penetrated the base (see Figure 17). This deviation-and-return process was clearly recorded by strain gauges arranged at the end of the joint. Two orthogonally oriented strain gauges (Ch5, Ch6) showed pronounced negative strain drops and positive strain rises during the mid-to-late loading stage (see Figure 18). These signals indicated significant shear compression and opening deformation on the joint surface prior to formation of the main crack. These findings confirmed the crucial role of the joint in crack initiation and local damage evolution. The asymmetric strain response further emphasized that the joint disturbed the initial crack path during early loading. The axial stress–strain curves showed a significant nonlinear mutation before peak load. This behavior reflected micro-interface sliding, local debonding, and pre-cracking evolution near the joint under compression. These initial inelastic processes significantly broadened the damage zone and increased the variability in crack paths. Energy analysis showed that dissipated energy accounted for 22.0% of the total energy. This indicated that the specimen T60 absorbed and released more energy than specimens containing side-positioned joints. Overall, the failure mechanism could be characterized as: damage initiation and development–enhanced nonlinear dissipation–joint-localized crack guidance–eventual reestablishment of main crack dominance.

Figure 17.

Crack propagation path for specimen T60.

Figure 18.

Strain-time curve for specimen T60.

In specimen S0, the joint direction was perpendicular to the axial load. The joint surface remained closed and showed no significant shear slip or opening during loading (see Figure 19). Two independent cracks first appeared in the upper region. This observation indicated that initial failure concentrated in the upper high-stress zone. The cracks converged in the mid-region. They then propagated rapidly towards the right-side joint and ultimately penetrated the specimen near the joint end. Strain gauges CH7 and CH8, located near the convergence point, recorded abrupt strain changes prior to crack penetration (see Figure 20). This response revealed that the joint participated in local stress release during the cracking termination stage and that marked stress redistribution occurred near the joint end. Although the joint surface did not slip, it was passively engaged during the cracking termination stage and contributed to local instability. Joints were not significantly activated at early stages, but cracks displayed clear path deviation at later stages. This behavior indicated a stress attraction effect toward the right-side joint. Consequently, joints locally guided crack paths during structural instability. The upper two cracks grew synchronously and converged near the mid-section to form a typical multi-path synergistic expansion zone. This pattern indicated spatial differentiation and aggregation of cracks. In addition, strain curves exhibited significant asymmetry across channels, with substantial differences in peak strain. These discrepancies may result from material heterogeneity, variations in local plastic deformation capacity, and stress concentration at the specimen tops. Collectively, these observations indicated complex, localized damage evolution mechanisms during crack propagation.

Figure 19.

Crack propagation path for specimen S0.

Figure 20.

Strain-time curve for specimen S0.

The crack propagation paths, energy dissipation mechanisms, and strain response characteristics differed markedly between the two joint configurations. For the T60 configuration, the crack initiation path was governed by the joint dip angle. The initiation path showed early deviations and disturbances but did not display the typical “differentiation–aggregation” behavior. Before the main crack formed, the joint ends already exhibited crack-tip plasticization and interface sliding. These processes produced a nonlinear curvature in the stress–strain curve before the peak and indicated early activation of a high-energy dissipation mechanism. Composite shear-opening deformations developed along the joint surface prior to crack penetration. These deformations provided a primary channel for crack induction and energy dissipation. For the S0 configuration, two independent cracks formed initially in the upper region. They converged near the midsection and then propagated toward the right joint end. This sequence exemplified the typical “differentiation–aggregation” propagation mode. This synergistic evolution of multiple cracks reflected the stress distribution in the upper high-stress zone and revealed the interactions among the cracks.

4. Conclusions

This study conducted uniaxial compression tests on specimens containing karst caves and joints with different spatial distributions and dip angles to investigate their mechanical response, energy evolution, and failure modes. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The strength displayed a bimodal dependence on joint dip angle. Joint arrangement significantly influenced the failure mechanism. The load-bearing capacity of the roof first decreased and then increased as the joint dip angle increased. The minimum load-bearing capacity occurred at 60°. This minimum resulted from side joints aligning with the principal load-transfer direction and the rock-mass failure path. That alignment reduced the load-bearing capacity more markedly than joints located at the top of the specimen.

(2) The dip angle and the number of joints acted synergistically to control the uniaxial compression behavior of specimens. The dip angle primarily governed failure mode and residual strength, while the number of joints determined load-bearing boundaries and influenced crack propagation conditions. The interaction between these two factors jointly determined the shape and key features of the stress–strain curves.

(3) The spatial arrangement of joints significantly influenced the characteristic energy input, elastic energy, and dissipated energy. Increasing the joint dip angle significantly improved the dissipation capacity and energy coupling efficiency of the specimen. Specimens containing top-positioned joints exhibited superior load absorption capacity, while those containing side-positioned joints showed higher dissipation efficiency and better coordination between elastic energy storage and energy dissipation.

(4) Crack propagation varied significantly among specimens with different joint configurations. In specimen S0, cracks followed a “differentiation–aggregation” propagation pattern. No sliding or opening occurred along the joint surface. Consequently, the specimen underwent rapid brittle fracture. In specimen T60, the joints altered the crack path. Damage initially expanded, and inelastic energy dissipation increased. The joints promoted shear-opening deformation before crack penetration, which facilitated crack initiation and increased the specimen’s energy-dissipation capacity.

The presence of joints significantly reduces the strength of the rock mass, alters its energy dissipation mechanism, and causes the main crack to deflect during failure. Therefore, the design of the safe thickness for a karst cave roof under a pile foundation must account for the influence of rock mass quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.; methodology, J.G. and S.Z.; software, C.Y.; validation, C.Y.; formal analysis, E.Y.; investigation, E.Y.; resources, J.G. and S.Z.; data curation, J.G.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted by Guangzhou University under the commission of CCCC Fourth Harbor Engineering Co., Ltd. and Guangzhou Municipal Engineering Design & Research Institute Co., Ltd. (Contract Number: CSDD-D2-2023-016). The article processing charge (APC) was funded by Yadong Li. The funder had the following involvement with the study: The funder, through its employees (J.G., S.Z., and C.Y.), was involved in the study’s conceptualization, methodology development, resource provision, data curation, and experimental validation.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jianmin Guo, Songtao Zhang, and Chunshan Yang were employed by the company Guangzhou Municipal Engineering Design & Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Li, Y.S.; Weng, X.J.; Wang, R.J.; Zhang, L.S.; Zhang, L.Z. Experimental study on simulating mechanism of water and mud Inrush in tunnel crossing fault fracture zone. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2020, 37, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.; Song, J.; Zhao, N.; Shao, Z. Study on the time-dependent interaction between surrounding rock and yielding supports in deep soft rock tunnels. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2024, 48, 566–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; He, P.; Wang, G.; Hu, J.; Jiang, F.; Yan, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Ma, Z. Analysis of progressive collapse disaster and its anchoring effectiveness in jointed rock tunnel. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2024, 48, 3876–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.X. Research on Occurrence Conditions and Disaster-Causing Mode of Water Inrush During Mountain Tunnel Construction. Master’s thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.L.; Wang, Z.F.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.Q. Characteristics, numerical analysis and countermeasures of mud inrush geohazards of Mountain tunnel in karst region Geomatics. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2242691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Liu, J.Q.; Xu, J.B.; Liang, B.; Li, W.J. Deformation Mechanism and Control Measures for Railway Tunnels under High Ground Stress and Water-rich Soft Rock. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2022, 22, 9364–9371. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.F. Study on the Hazard Assessment of Karst Groundcollapse in Shenzhen Universiade Center. Ph.D. thesis, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, M.H. Research on Mechanical Behavior of Lining Structure of Concealed Karst Tunnel Under Local Water Pressure. Ph.D. thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Romanov, D.; Kaufmann, G.; Al-Halbouni, D. Basic processes and factors determining the evolution of collapse sinkholes—A sensitivity study. Eng. Geol. 2020, 270, 105589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Zhang, X.Y. Analytical Solutions of Surrounding Stress Fields in Multi Caves Tunnel. Highw. Eng. 2014, 39, 268–271. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Gao, S.M.; Liu, L.F.; Wen, W.S.; Li, P.; Chen, J.P. Analysis on the safe distance between shield tunnel through sand stratum and underlying karst cave. Geosyst. Eng. 2019, 22, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ding, H.; Zhang, P. Influence of karst caves at pile side on the bearing capacity of super-long pile foundation. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 4895735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Zhao, L.; Ling, T.; Yang, X. Rock mass collapse mechanism of concealed karst cave beneath deep tunnel. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2017, 91, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, J. Shear failure of anistropic rocks. Geol. Mag. 1960, 97, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandis, S. Experimental Studies of Scale Effects on Shear Strength, and Deformation of Rock Joints. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leeds, West Yorkshire, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Yang, T.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Deng, W.; Gao, Y.; Li, H. Modeling spatial variability of mechanical parameters of layered rock masses and its application in slope optimization at the open-pit mine. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2024, 181, 105859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, F.; Dong, L.; Xu, N.; Feng, P. Experimental Investigation on the Fatigue Mechanical Properties of Intermittently Jointed Rock Models Under Cyclic Uniaxial Compression with Different Loading Parameters. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2018, 51, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Yu, H.; Deng, Z.; He, Z.; Zhao, Y. Cracking and deformation of cuboidal sandstone with a single nonpenetrating flaw under uniaxial compression. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2022, 119, 103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.C.; Zhao, X.Y.; Guo, J.Q. Experimental study on acoustic and mechanical properties of intermittent jointed rock mass. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2020, 39, 1408–1419. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Song, Z. Investigation of mechanical behavior, AE and EMR characteristics of rocks under compression-shear loading via variable-angle shear tests. J. Appl. Geophys. 2023, 217, 105197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Jiang, G.; Yuan, D.; Yang, J.; Guo, C.; Yue, F.; Yuan, P.; Wu, H.; et al. Development characteristics and controlling factors of karst aquifer media in a typical peak forest plain: A case study of Zengpiyan National Archaeological Site Park, South China. Water 2024, 16, 3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Zhu, H.; Liang, W.; Wang, X.; Su, C.; Wei, X. A post-peak dilatancy model for soft rock and its application in deep tunnel excavation. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 15, 683–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S.; Luan, H.; Tian, G.; Feng, C. Analysis on damage evolution of jointed rock masses containing a circular hole under uniaxial compression. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y. Test research on factors influencing bearing capacity of rock-socketed piles in karst area. Rock Soil Mech. 2013, 34, 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.; Yin, J.; Chen, Q.; Yang, W. Experimental study on bearing capacity of rock-socketed pile over karst cave. Min. Metall. Eng. 2017, 37, 19–22+6. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. Bearing Mechanism and Design Method on Rock-Socketed Piles in Karst Areas. Ph.D. thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M.; Yuan, J.; Shan, Y.; Tong, H.; Cui, J. Indoor Scaled Model Test and Numerical Simulation Analysis on the Influencing Factors of Toe Bearing Capacity of Rock-Socketed Piles in Karst Area. Guangdong Archit. Civ. Eng. 2025, 32, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Sun, B.; Cui, J.; Zeng, S.; Shan, Y. A Novel Rock Damping Ratio and Damping Coefficient Based on Linear Energy Damping Law. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 6007–6024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).