Abstract

In historic and cultural districts characterized by the coexistence of residential and commercial functions, street spaces play a pivotal role in shaping urban cultural continuity and local identity. They simultaneously support the daily lives and emotional attachment of residents while accommodating the tourism activities of visitors. Despite this dual significance, the distinct functional and experiential expectations of residents and tourists have resulted in multidimensional perceptual differences, which have not been sufficiently addressed in previous studies yet are crucial for enhancing street space quality. Using the Sajinqiao Historic and Cultural District in Xi’an, China, as a case study, this research develops a perceptual evaluation system for street spaces and applies an enhanced IPA-KANO model to examine variations in explicit importance, attribute performance, and implicit importance between residents and tourists. Findings indicate that residents attach greater importance to religious sites, community facilities, and cultural belonging, whereas tourists prioritize transport accessibility, iconic architecture, and commercial vibrancy. Both groups expressed relatively low satisfaction with several key cultural experience elements. Based on these results, this study proposes targeted optimization strategies for elements identified as highly important yet underperforming, providing a practical framework for balancing heritage conservation with contemporary tourism development in such integrated urban environments.

1. Introduction

In 2016, UNESCO’s global report Culture: Urban Future emphasized that “historic street spaces create and transmit a sense of place for future generations, providing spatial support for social activities such as storytelling, performing arts, rituals, and other intergenerational practices, collectively shaping urban identity” [1]. In China, a Historic and Cultural District is a statutory concept within the national cultural heritage protection system. It specifically refers to an area recognized through official declaration, evaluation, and designation according to the Regulations on the Protection of Famous Historic and Cultural Cities, Towns, and Villages [2], signifying its important historical and cultural value. In the international context, the roughly corresponding concepts often have a broader scope, such as “Historic Urban Areas” or “Historic Areas” [3,4]. The street spaces within China’s Historic and Cultural Districts, characterized by their unique spatiotemporal attributes, systematic layout, and diverse functions [5], carry profound historical and cultural significance. These spaces function as hubs for community interaction and facilities for daily life [6], bearing the emotional memories of residents [7,8]. They also form an urban framework that connects tangible and intangible cultural heritage, holding immense conservation value. With the development of modern tourism, the street spaces in Historic and Cultural Districts, owing to their distinctive architectural styles, human-scale spatial dimensions, and localized commercial facilities, have increasingly become venues for cultural experiences and even key cultural attractions that draw tourist flows, thereby assuming a role in promoting cultural and economic functions [9,10].

International research on modern urban design and heritage conservation emphasizes the importance of “place making” and “shared space” in historic districts. Kevin Lynch’s The Image of the City [11] and Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities [12] laid the cognitive foundation for understanding the interaction between residents and street spaces, highlighting that quality streets require distinctive architectural texture, diverse activity scenarios, and a secure community environment. Although both focus on the needs of local residents, their theories indirectly support the cultural and tourism functions of historic districts—spatial legibility and street vitality objectively become fundamental elements for attracting tourists. In 2011, UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape [13] aimed to integrate the goals of heritage conservation with socio-economic development, promoting comprehensive and sustainable heritage management. In terms of material heritage, integrity focuses on the soundness and health of heritage as a whole—encompassing its structure, environment, and constituent parts—while authenticity centers on the veracity of the sources of information that constitute the heritage, including materials, craftsmanship, design, function, and even intangible spiritual elements. The two concepts are mutually reinforcing: if the materials or design (core elements of authenticity) of a heritage site are extensively replaced or altered, its overall historical and artistic value (the concentrated expression of integrity) will inevitably be compromised. Consequently, the international heritage conservation community has reached a consensus that integrity and authenticity must be applied in tandem, requiring comprehensive assessment and coordinated protection of heritage sites. Furthermore, at the level of intangible cultural heritage, “visibility” manifests as the degree to which it is embodied through material carriers, practical processes, and social functions, the “degree of transmission” of traditional crafts measures the breadth and depth of its intergenerational transmission. The “preservation” of tangible cultural heritage and the “transmission” of intangible cultural heritage complement each other, jointly forming the dual objectives for achieving sustainable conservation of living heritage within historic districts. Therefore, for the street spaces of historic and cultural districts, appropriate conservation and utilization should be closely aligned with the demands of urban socio-economic development [14], providing residents with comfortable and convenient living environments while enhancing attractiveness to tourists, thereby making these spaces shared by both residents and visitors.

In the process of urban renewal in China, historic and cultural districts generally face issues such as declining street environmental quality and disordered landscape features, which not only constrain the improvement of local residents’ quality of life but also lead to inconsistent levels of tourist satisfaction. According to data from the 2023 “China Historic District Perception Survey Report”, 46% of tourists questioned the historical authenticity of renovated districts, while 83% of residents expressed concern about the loss of community belonging [15]. This reflects the multi-dimensional perceptual differences arising from the conflict between residents’ needs for localized living and tourists’ demands for cultural experiences within the spatial context of historic districts.

Tourism intervention not only alters the physical landscape of historic district street spaces but also profoundly impacts residents’ lives [16]. The sustainable development of these spaces must simultaneously respond to the behavioral patterns and consumption demands of tourists, as well as the functional needs of residents for their living environment [17]. Achieving a balance between host and guest needs constitutes a core challenge for realizing resource sharing in these districts and promoting sustainable development. Recent studies have employed improved Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA) for quadrant-based evaluations of tourist satisfaction [18], while others have utilized artificial intelligence technologies to analyze street space characteristics based on tourist behavior data [19,20]. However, most existing literature on spatial perception in historic districts focuses either on residents or tourists in isolation, lacking a comparative analysis that integrates the perspectives of both groups. Furthermore, spatial optimization pathways that balance the preservation of historical value with commercial development remain underexplored.

In summary, addressing the conflicts between the needs of residents and tourists and the challenge of coordinating street space preservation in historic districts with urban development necessitates foundational research from the user’s perspective. By studying the perceptual differences between residents and tourists, it is essential to explore optimization strategies for street spaces that balance the preservation of residents’ living environments with the attraction of tourist experiences.

This study selects the Sajinqiao Historic District in the old town of Xi’an, China, where commercial and residential functions coexist, as a case study. It constructs a street space evaluation system to explore the perceptual differences between residents and tourists regarding street space in historic districts and proposes optimization strategies for such spaces that promote the harmonious coexistence of cultural heritage preservation and residential-tourism functions. Based on a “physical-psychological” dual-perception framework, an evaluation index system for street space in historic districts is established (Section 3). Through questionnaire surveys, perceptual data from residents and tourists are systematically collected to assess the degree to which their needs are met across five dimensions: architectural style, spatial form, street environment, cultural continuity, and spatial atmosphere. A comparative analysis of the evaluations from the two groups is conducted to reveal the comprehensive mechanism by which the physical environment and humanistic experience interact within the street space of historic districts. To address the impact of differences in the validity of subjective evaluations between residents and tourists on the credibility of the findings, an improved Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA-KANO model) is employed. This model is used to investigate the relationship between street spatial elements and subjective perception from the dual perspectives of residents and tourists, enabling the classification, identification, and prioritization of the needs and preferences of both groups (Section 4). This approach more scientifically and objectively reveals their authentic demand structures and importance evaluation results. The research provides a scientific basis for the conservation and development of street spaces in historic districts characterized by the coexistence of residence and tourism, and offers practical optimization strategies (Section 5).

2. Literature Review

This study begins with the two key concepts of host–guest sharing and the perception of historic district street spaces, summarizing previous relevant research.

2.1. Host–Guest Shared Concept

In tourism research, anthropologists first emphasized the necessity of studying host–guest relationships [21]. American anthropologist Valene L. Smith pointed out that host–guest relationships have always been a core theme and research focus in tourism anthropology [22]. As important cultural carriers and tourist destinations, the rise and development of historic districts have led to encounters between local residents and tourists in street spaces, resulting in host–guest relationships with spatial specificity [23]. During tourism activities, the interactions and communicative behaviors between these two groups in the street spaces of historic districts break the inherent “host–guest binary opposition” [24]. Host–Guest Shared is based on the needs of residents (as “hosts”) and tourists (as “guests”), aiming to meet residents’ daily and productive needs while providing high-quality tourism services for visitors [25]. By improving public service facilities in historic district streets, it strives to create a harmonious and shared street space environment for both residents and tourists.

With the vigorous development of the cultural and tourism industry, the concept of “Host–Guest Shared” has gradually become a topic of academic focus, primarily in the following directions: First, the theoretical construction and model exploration of host–guest relationships. Xinran Lehto and colleagues proposed analyzing host–guest relationships through hedonism, constructing a model of hedonistic tourism that includes a tripartite alliance of economy, experience, and hospitality. The synergy among these three aspects shapes a positive host–guest relationship, offering a new pathway for promoting host–guest shared experiences and sustainable tourism development [26]. Second, the transformation of value logic and reflection on local practices. Vanessa Muler González and other scholars found that in the context of tourism degrowth, the value logic of Host–Guest Shared in Spanish towns has been reshaped, with tourism values shifting from market orientation to a greater emphasis on harmony and low consumption [27]. Robina-Ramirez, Sánchez-Oro, Cabezas-Hernández and associates taking the Tajo International Nature Park as a case study, explored the impact of host–guest social exchanges on socio-economic welfare in tourist destinations, providing empirical evidence for analyzing the economic and social effects of Host–Guest Shared [28]. Third, research on spatial perception and emotional mechanisms. Zhang’s team revealed a divergence in the perception of accessibility to public open spaces between tourists and residents: tourists focus on spatial attractiveness, while residents emphasize daily travel costs. Furthermore, they found that perceived accessibility affects place attachment through the mediating role of place satisfaction, offering a basis for coordinating host–guest needs [29]. Tao Hui and other scholars studying heritage tourism destinations in China, revealed the four-stage evolution of host–guest interactions from a micro-mechanism perspective and highlighted the role of residents’ positive emotions in promoting their participation in tourism activities, deepening the understanding of the emotional dynamics of Host–Guest Shared [30]. Fourth, from an interdisciplinary perspective of environmental psychology and behavioral geography, Vikas Mehta’s study on vibrant streets compellingly reveals the material attributes of public spaces that foster social interaction. Through empirical observations and interviews in community commercial streets, the research indicates that a street’s vitality stems not only from its functional role as a thoroughfare but also from its potential as a social space. The findings reveal that streets capable of becoming catalysts for “shared spaces” typically exhibit the following characteristics: shops that serve as community gathering points and bearers of collective memory; diverse business formats that meet daily needs; and street furniture and building facades that create a pleasant pedestrian environment. These physical elements collectively form a stage that supports serendipitous encounters and spontaneous social interactions. This blurs the boundaries between local residents and visitors, encouraging them to share the same public domain. Mehta’s work demonstrates at the micro-behavioral level that “shared use” is not an abstract concept but can be actively cultivated through thoughtful physical environment design [31].

Based on the aforementioned research, while the application of the “Host–Guest Shared” concept in tourism studies has yielded certain achievements, the mechanisms underlying host–guest sharing in historic and cultural districts characterized by the integration of residence and tourism still require further investigation to refine quantitative evaluation models.

2.2. Perception of Street Space in Historic Districts

The street space of historic districts serves as a core carrier for activating the urban cultural lineage [32]. However, under the influence of commercialization and touristification, historic streets face changes in user groups and functional shifts [33], and their specific issues of disordered landscape features can easily lead to behavioral and psychological exclusion among both residents and tourists [34]. Therefore, enhancing the perceived quality of street space is not only key to ensuring tourism quality but also a practical requirement for optimizing street space in historic districts.

Research on the perception of street space in historic districts primarily focuses on three methodological approaches: First, data-driven and quantitative analysis for measuring street morphology and perception. For instance, based on deep learning of street view imagery, measurements can be conducted including street environmental characteristics, service facilities, and walkability perception [35]. Lotfata, taking Iranian cities as an example, indicated that space syntax can be used to analyze how modern urban interventions alter the spatial structure of historic urban areas [36]. Zeng and Shen, focusing on Zhangzhou Ancient City, utilized both physical and perceptual indicators to assess the walking environment [37]. Through longitudinal research, they revealed how renewal projects changed the street walking environment and residents’ walking behaviors, demonstrating that new technologies enable multi-dimensional quality analysis of streets. Second, perception experiments focusing on users’ subjective experiences and behavioral mechanisms. Ding established an evaluation and optimization system from a community governance perspective [38]. By constructing a multi-dimensional indicator system and a neural network evaluation model, this study concentrated on the subjective experiences and behavioral mechanisms of tourists and residents in historic public spaces, revealing the significant role of spatial renewal in community governance and people-oriented development. Scholars like Park used confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling to examine the causal relationships between nostalgia, authenticity, satisfaction, and revisit intention among tourists visiting Suwon Gidong Mural Alley in South Korea, emphasizing the importance of tourist satisfaction [39]. Third, building upon the foundation of subjective psychological measurement, the quantitative analysis of visual perception provides a complementary perspective for understanding the behavioral mechanisms of tourists. For instance, Ding Wenqing et al. developed a dual-perception evaluation system integrating eye-tracking experiments and the semantic differential method, systematically analyzing the influence mechanisms of spatial elements on tourists’ behavioral preferences and psychological experiences [40]. Additionally, such quantitative analysis has been extended to the relationship between the overall physical form and perception. As demonstrated by Zagroba, Szczepańska, and Senetra, who established historical interpretive criteria, the orderliness and harmony of urban layout and architectural design significantly influence spatial perception [41].

Existing research has primarily focused on street spatial elements and the subjective experiential perceptions of the general public as key study areas for historic district street spaces. However, there remains a lack of systematic quantitative comparison and in-depth analysis regarding the perceptual differences between tourists and residents within the same spatial context. Building upon the research frameworks established in existing literature concerning the perceived quality of historic district street spaces and user behavior mechanisms, this study addresses the previously underexplored issue of perceptual differences between tourists and residents in their use of street spaces. It aims to identify and analyze the similarities and differences in their experiential perceptions through questionnaire surveys, thereby providing an empirical basis for a deeper understanding of the differentiated needs various user groups have for historic district street spaces.

2.3. Geometric Qualities of Public Space and Pedestrian Networks

The usability of open public spaces is fundamentally shaped by their geometric qualities and the pedestrian networks they are part of. The pedestrian network, acting as the skeleton of the urban fabric, primarily dictates the space’s accessibility and guides the flow of people. Meanwhile, the inherent geometric characteristics of the space itself directly influence users’ willingness to linger and interact. This relationship forms the theoretical foundation for the “Physical Perception” dimension in this study.

In A Pattern Language (1977), Christopher Alexander systematically outlined a series of design patterns for creating pleasant spaces, such as “Positive Space”, “Pedestrian Street”, and “Small Public Squares” [42]. These patterns deeply elucidate how geometric forms, boundary definitions, scale, and the layout of spatial pathways fundamentally encourage social interaction and dwell time.

In his work Design for a Living Planet, Michael Mehaffy proposed the “Place Network Theory,” which he describes as a “grand unified theory of urbanism” that synthesizes ideas from thinkers such as Christopher Alexander, Jane Jacobs, and Kevin Lynch. This theory emphasizes the adaptability of place networks across different urban contexts [43]. Moreover, in the renewal of historic districts, the continuity of geometric patterns is crucial for preserving the spirit of place. Together, these theories indicate that well-designed geometric patterns in public spaces can naturally attract people, encouraging congregation and active use.

Pedestrian networks connecting the aforementioned spaces and acting as the lifeblood that animates them. Neo-traditional urbanism, as advocated by Leon Krier [44] and Nir Buras, prioritizes walkability as a core principle. It promotes interconnected street networks emphasizing the experience of pedestrians and cyclists. Through high connectivity and permeability, such network structures significantly enhance spatial accessibility, thereby naturally fostering dense and diverse daily interactions and laying the foundation for users’ spatial perception.

The guiding mechanisms of spatial geometry and pedestrian networks on behavioral patterns have been thoroughly validated through contemporary empirical research. These studies focus on how to utilize artificial intelligence and neuroarchitecture tools—such as eye-tracking and electroencephalography (EEG)—to conduct quantitative analysis of human–environment interactions. Research by scholars including Ann Sussman, Cleo Valentine, and Justin Hollander demonstrates that human gaze behavior toward architectural interfaces and urban boundaries follows highly regular subconscious patterns [45]. For instance, building facades exhibiting specific proportions, symmetry, or complexity, along with spatial boundaries offering a “sense of edge shelter,” significantly attract visual attention and encourage users to linger. These findings cognitively validate core tenets of Christopher Alexander’s Pattern Language theory and Jan Gehl’s public space theory—namely, that spatial geometric characteristics profoundly influence user behavioral preferences and spatial perception through subconscious visual and psychological mechanisms.

Jan Gehl’s theory of public space in Life Between Buildings provides the most direct theoretical bridge for this research [46]. Gehl systematically elucidated how spatial geometry and pathway design collectively influence pedestrian activity. He emphasized that spaces encouraging interaction and use must possess the following qualities: first, a human scale and refined geometric articulation to create a sense of intimacy; second, a clear, comfortable, and safe pedestrian network to ensure accessibility; and third, boundary designs that promote “lingering,” offering a “stage” for observation and interaction. Gehl’s theory closely connects macro-level spatial forms with micro-level individual behavior.

In summary, the geometric properties of open spaces and pedestrian networks form an inseparable whole. By influencing accessibility, visual appeal, and behavioral comfort, they fundamentally promote the use of space. This interdependence constitutes a key rationale for the street space perception evaluation system developed in this study (See Section 3.3.1 for details).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Subject of Study

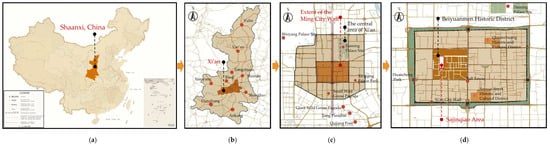

This study selects the Sajinqiao Historic District in Xi’an, China, as the research site. Xi’an is a globally renowned historic and cultural city, the starting point of the ancient Silk Road, and a significant destination for both domestic and international tourism [47]. The Sajinqiao area belongs to the northwestern part of the Beiyuanmen Historic and Cultural District [48], located within the old town boundaries defined by the Ming Dynasty city wall of Xi’an (Figure 1). The street space of Sajinqiao carries the unique ethnic traditions, religious culture, and historical memories of the Hui people (The Hui people, one of China’s largest ethnic minorities, practice Islam and maintain distinctive cultural practices, such as observing dietary codes that exclude pork and alcohol, and traditionally gathering around mosques that often blend Arabic and Chinese architectural styles.) [49], serving as a vital living space for local residents and a charming space for tourists to experience Xi’an’s local customs and culture [7,50]. This study area represents a typical case characterized by both the social stability of a high-density permanent population and the heterogeneous flow of diverse tourists, providing a representative empirical sample for researching perceptual differences between the two key subjects of residents and tourists.

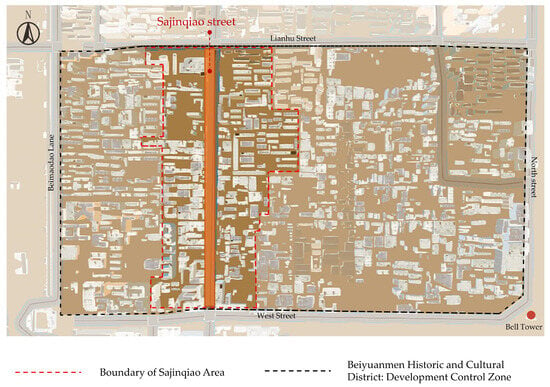

Figure 1.

Location of the Sajinqiao Historic District: (a) Geographical Location of Shaanxi within China; (b) Geographical Location of Xi’an within Shaanxi; (c) Location of the Hui Quarter (Muslim Quarter); (d) Location of the Sajinqiao Area within the Beiyuanmen Historic and Cultural District.

The main street of Sajinqiao spans 800 m in total, connecting with the east–west arterial roads of Lianhu Road to the north and West Street (Xi Dajie) to the south. The Sajinqiao area studied in this paper centers on the main street of Sajinqiao (covering the entire section of Sajinqiao–Damaishi Street) and extends 200–300 m outward on both sides, delineated in combination with the existing building fabric, covering an area of approximately 52 hectares (Figure 2). The road network within the area is well-preserved, with an overall road width of less than 20 m, accommodating pedestrian walking, vehicle traffic, and commercial activities.

Figure 2.

Location and Scope of the Sajinqiao Area.

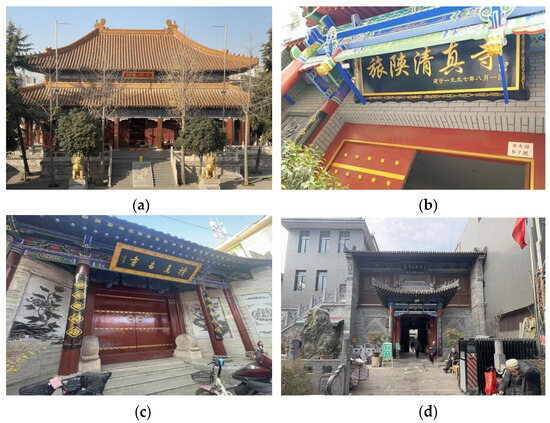

The residential function of the Sajinqiao Historic District is primarily characterized by traditional courtyard dwellings of the Muslim Quarter (Huifang), while its commercial function centers on Halal specialty catering and market-based businesses. These two functions are interwoven along the street, collectively sustaining the local lifestyle and vibrant urban atmosphere [51]. The historical and cultural elements of Sajinqiao Street are predominantly rooted in religious culture (Figure 3), including Buddhist culture represented by the Xiwutai Yunju Temple—a provincial-level key cultural relic protection unit—and the Islamic culture of the Hui people embodied by mosques. Three Islamic mosques are distributed along the southern section of the street, from north to south: the Xi’an Lüshan Mosque, the Sajinqiao Ancient Mosque, and the Sajinqiao West Mosque. As historical buildings, they serve as key nodes for showcasing religious culture, simultaneously shaping the spirit of place and inheriting the historical and cultural heritage of Sajinqiao.

Figure 3.

Cultural Heritage Protection Units in the Sajinqiao Area: (a) Xiwutai Yunju Temple; (b) Xi’an Lüshan Mosque; (c) Ancient Mosque; (d) West Mosque.

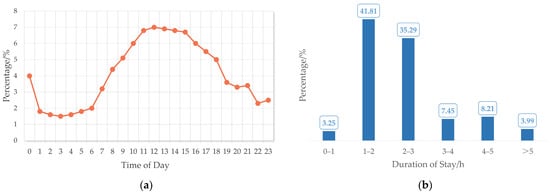

The Sajinqiao Historic District is one of the key tourist destinations in Xi’an. According to an analysis of the district’s population and mobile phone signaling data conducted by scholars (Figure 4), the average daily visitor flow during the 2023 Spring Festival, Labor Day, and National Day holidays exceeded 20,000 people. Field observation and research analysis indicate that 11:00–13:00 is the peak period for tourist arrivals, accounting for approximately 20% of the daily total visitor volume (Figure 4a). The duration of visits to the Sajinqiao area is concentrated between 1 and 3 h, comprising about 77% of the total tourist visits (Figure 4b) [52]. Tourist activities primarily focus on visiting the Xiwutai Yunju Temple, various mosques, dining at local eateries, and experiencing local folk culture. Additionally, our interviews revealed some resident complaints about public space occupation and daily life disruptions. Approximately 35% of respondents in the resident survey mentioned congestion and noise issues during peak tourism periods, which impacted their daily routines.

Figure 4.

Distribution of Tourist Arrival Patterns and Length of Stay in the Sajinqiao Area Within a Single Day: (a) Intraday Pattern of Tourist Arrivals in the Area; (b) Intraday Distribution of Tourist Stay Duration. (Source: Adapted from Reference [52]).

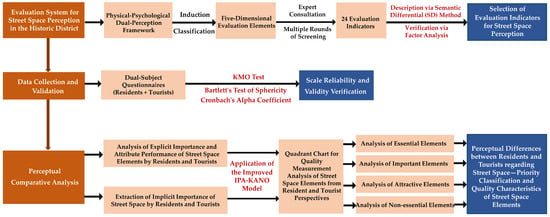

3.2. Research Framework

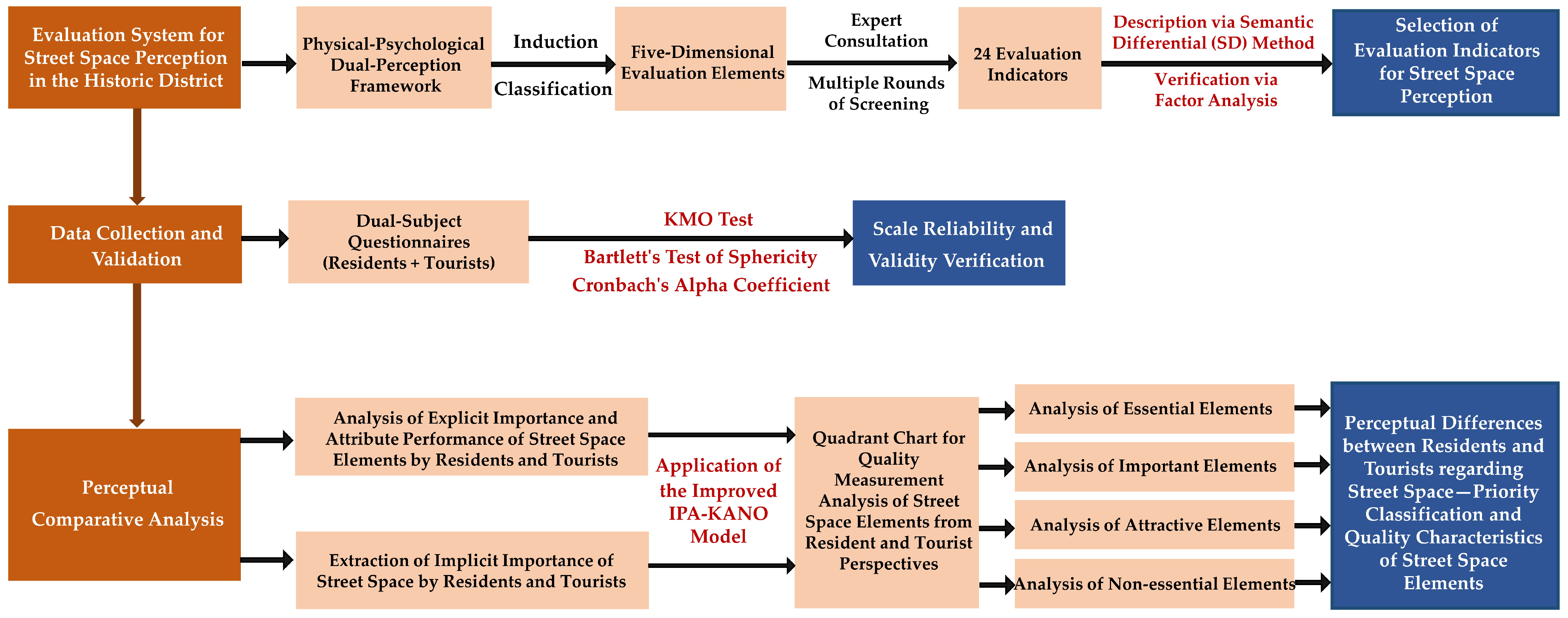

The research framework is illustrated in the figure below (Figure 5). First, this study is based on a “physical-psychological” dual-perception framework (see Section 3.3.1 for full theoretical justification), which structures the perception of street space into five dimensions: architectural style, spatial form, street environment, cultural continuity, and spatial atmosphere. This division is grounded in Jan Gehl’s theory of public space and principles of environmental psychology. Through a comprehensive literature review and field investigations, a set of evaluation indicators were initially identified, systematically classified, and integrated according to the five proposed dimensions. Then, through expert consultation and multiple rounds of screening and optimization, a final evaluation system consisting of 24 indicators was formed. All indicators were described using the Semantic Differential (SD) method [53,54]. Furthermore, factor analysis was employed to extract common factors of street spatial elements, and a factor loading matrix was used to verify the classification and naming of the indicators, thereby finalizing the evaluation system for perceiving street space in historic districts. Second, a dual-subject questionnaire targeting both residents and tourists was designed. Data from residents and tourists were collected through a combination of online and offline methods. The reliability and validity of the scale were verified using the KMO test [55], Bartlett’s test of sphericity [56], and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient [57]. Finally, we adopted an improved IPA-KANO model [58]. This model enabled us to compare the explicit importance and performance ratings between and within the groups, while also incorporating the analysis of implicit importance. Consequently, quadrant maps were plotted to facilitate a quantitative analysis of the priority and quality characteristics of street space elements. This model was used to plot quadrant maps of perceptual elements for residents and tourists, enabling a quantitative analysis of the priority classification and quality characteristics of street spatial elements.

Figure 5.

Research Framework Diagram for the Evaluation of Street Space Perception in Historic and Cultural Districts.

3.3. Research Methods

3.3.1. Establishing an Evaluation System for Street Space Perception in the District

Based on the “physical-psychological” dual-perception framework, this study constructs an evaluation system applicable to the spatial elements of streets in historic and cultural districts. This system emphasizes a comprehensive consideration of both the physical environment and humanistic experiences, dividing spatial perception into five dimensions. At the physical perception level, drawing on Jan Gehl’s concept of “people-oriented” from public space theory [59]—which particularly focuses on the impact of the spatial environment on human activities and perception—physical perception is parsed into three dimensions: Architectural Style (B1), Spatial Form (B2), and Street Environment (B3). These dimensions are designed to reflect their support for perceptual values related to daily life, social interaction, and safety. At the psychological perception level, grounded in environmental psychology and related socio-cultural theories, psychological perception is divided into two dimensions: Cultural Continuity (B4) and Spatial Atmosphere (B5). This division aims to encompass multi-layered perceptual content ranging from socio-cultural psychology to individual emotional experiences. This classification not only reflects the cognitive logic progressing from material entities to non-material connotations but also aligns with the comprehensive evaluation needs for the conservation and development of historic and cultural districts, thereby providing a theoretical basis for the systematic evaluation of street spatial elements [60]. Subsequently, by referencing existing literature on spatial perception and combining findings from field investigations, C-level evaluation factors suitable for assessing street space perception in historic and cultural districts were derived from the B-level elements.

Architectural Style (B1): Selecting architectural style (B1) as an evaluation metric traces its theoretical origins to architectural typology theory. This theory emphasizes that architectural style represents the cumulative manifestation of explicit contextual elements within a region, authentically documenting the evolution of urban architectural styles while systematically reflecting the physical form and visual characteristics of the area. Within this theoretical framework, dimension B1 follows typology’s operational logic of “progressing from overall typological identification to analysis of local elements.” It naturally subdivides into Building Appearance (C1), which focuses on universal formal characteristics, and Heritage Elements (C2), which carry specific historical memories. Together, these encompass elements such as street-facing building forms, facade configurations, color applications, and iconic historical structures.

Spatial Form (B2): This primarily pertains to Spatial Layout (C3). It covers elements like traditional residential patterns, mixed commercial-residential configurations, and the linear structure of the street space. These aspects embody the spatial organization and layout logic of the district.

Street Environment (B3): This dimension can be detailed into Traffic Environment (C4), Streetscape Greening (C5), and Infrastructure (C6). It involves factors such as traffic accessibility and convenience, the quality and diversity of street greenery, and the provision of public service and leisure facilities. These elements jointly constitute the functional and environmental quality of the street.

Cultural Continuity (B4): This can be broken down into Traditional Crafts (C7), Culinary Culture (C8), and Religious Culture (C9). It includes elements like local traditional skills, folk culture experiences, distinctive food culture, and religious cultural components. These elements carry the district’s intangible cultural traditions and collective memory.

Spatial Atmosphere (B5): This dimension is subdivided into Residential Atmosphere (C10) and Commercial Atmosphere (C11). It encompasses the types of human activities, the distinctive character of places, as well as the mix and uniqueness of commercial offerings. These factors together shape the social vitality and overall ambiance of the place.

These five dimensions systematically integrate various elements ranging from the physical environment to humanistic experiences, collectively constructing the theoretical framework for the “physical-psychological” dual-perception evaluation. Furthermore, relevant evaluation indicators from the literature on street space perception were reviewed to provide a reference for decomposing the C-level evaluation factors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reference Sources for Evaluation Indicators of Street Space Perception in Historic and Cultural Districts.

Based on this foundation, further consultations were conducted with planning and design experts through multiple rounds of evaluation to screen, modify, and optimize the initially selected indicators. This process ultimately led to the construction of a comprehensive evaluation system (Table 2) consisting of five dimensions: Architectural Style (B1), Spatial Form (B2), Street Environment (B3), Cultural Continuity (B4), and Spatial Atmosphere (B5), comprising a total of 24 indicators. All indicators within this system are derived from mature evaluation elements that have been widely applied in existing literature. Through systematic integration and localization adaptation, the system ensures scientific rigor and comparability while providing a practical theoretical basis for the objective assessment of district spatial quality.

Table 2.

Evaluation System for Street Space Perception in Historic and Cultural Districts.

To better understand this evaluation system, the key indicators within it will be explained below.

- (1)

- Religious buildings are singled out in terms of preservation status because they serve as the spiritual and cultural core of the Sajinqiao Historic District, embodying unique ethnic traditions and community identity that require prioritized conservation to maintain the district’s overall heritage significance. This emphasis directly ties into the integrity and authenticity of historic buildings, as the preservation of religious structures ensures their physical wholeness and material truthfulness, which in turn reinforces the cultural continuity and perceptual value of the entire historic environment.

- (2)

- The “transmission degree” measures the breadth and depth of intergenerational transmission of traditional crafts, serving as a key indicator of their vitality. Grounded in UNESCO’s focus on sustaining living heritage, this concept underscores the importance of effective transmission mechanisms. Our assessment examines the recognition of representative bearers and the frequency of transmission activities to evaluate the resilience and continuity of these crafts.

- (3)

- Cultural Atmosphere of Religious Sites: This refers to the holistic environment of religious spaces (e.g., mosques) in Sajinqiao, combining tangible elements (architecture, layout, decor) and intangible elements (sounds, smells, activities) that create a sense of spiritual and cultural place.

- (4)

- In our study, the assessment of “Spatial Layout (C3)” is precisely based on the analysis of characteristic land use patterns found in the case study area. As shown in our framework table, the three sub-categories under C3 each define a specific land use configuration: (D6) Residential Pattern of Settling Around Mosques: reflects a religious-residential land use relationship, (D7) Spatial Form of ‘Shop in Front, Residence in Back’: embodies a mixed commercial-residential land use pattern, and (D8) Linear Commercial Pedestrian Street: represents a dedicated commercial pedestrian land use.

- (5)

- Specifically, the indicators of Landscape Coordination (D11) and Landscape Richness (D12) are designed to evaluate the integration, design quality, and visual diversity of all street-level landscape elements. This comprehensive assessment inherently includes the materials, patterns, and vegetated areas that constitute the ground plane, which are central to the concept of floorscape.

Subsequently, the Semantic Differential (SD) method was employed to describe the specific evaluation indicators in the questionnaire. For detailed descriptions of each indicator, please refer to Table 3.

Table 3.

Description of Evaluation Indicators for SD Factor Adjective Pairs.

3.3.2. Factor Analysis

Factor analysis originated in the early 20th century as a method for defining and measuring intelligence, pioneered by scholars such as K. Pearson and C. Spearman [67]. It is a multivariate statistical technique used for dimensionality reduction [56], enabling the simplification and condensation of original data. The primary objective of factor analysis is to describe a set of observable, interrelated variables using the smallest number of unobservable, uncorrelated factors, while reasonably explaining the correlations among the original variables [61].

In this study, factor analysis is employed to assess the overall explanatory power of the scale and to examine the grouping of evaluation factors through the factor loading matrix.

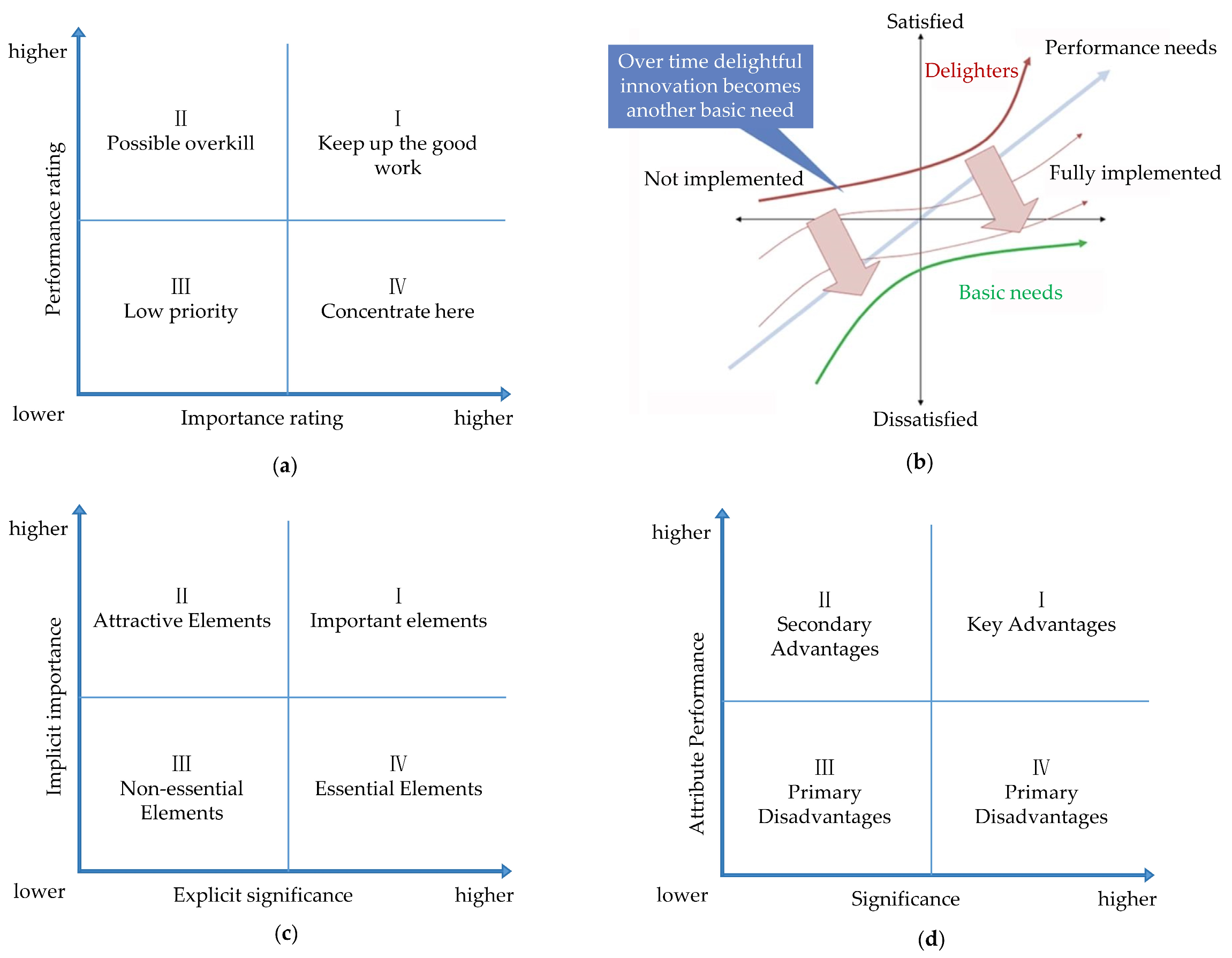

3.3.3. Improved IPA-KANO Model Analysis Method

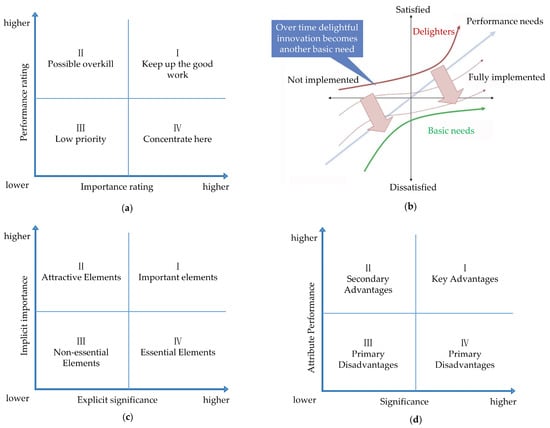

Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA) is a tool for deciding resource allocation priorities by comparing the importance (using “explicit importance,” i.e., preference level, in this study) of attributes with their performance (i.e., satisfaction level) (Figure 6a) [68]. The IPA matrix serves as an effective hierarchical decision-making framework by categorizing attributes into distinct quadrants, which directly prescribes strategic priorities for management and resource allocation. This approach is conceptually aligned with hierarchical analysis methods like the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) in structuring complex decisions, and with MICMAC analysis in identifying key factors based on their driving power and dependence.

Figure 6.

Schematic Diagrams Related to the IPA-KANO Model: (a) Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA); (b) Kano Model; (c) IPA-KANO Quality Optimization; (d) IPA-KANO Quality Optimization Model.

The Kano model, proposed by the Japanese scholar Noriaki Kano, is a tool for classifying and prioritizing user needs (Figure 6b) [69]. Since differences in the validity of subjective evaluations between residents and tourists can impact the credibility of research findings, and based on the similarities and differences between IPA and the Kano model, scholars have integrated them to propose the IPA-KANO quality measurement model (Figure 6c) [70,71].

The specific integration process in this study is as follows: First, an evaluation system for perceiving street space in the district is constructed. Based on the IPA model, questionnaires are designed for both resident and tourist groups regarding the explicit importance and attribute performance satisfaction of street spatial elements. Second, using the importance and satisfaction scores of each element as bivariate data, correlation analysis is conducted with the SPSS 27.0 software, and the correlation coefficient is used as the implicit importance score for different elements. Third, based on the constructed IPA-KANO explicit-implicit analysis model and utilizing theories related to the Kano model, street spatial elements are divided into four quadrants according to their explicit and implicit importance. These quadrants correspond to different quality attributes: High Explicit-High Implicit (Important Elements—Key Advantages), High Explicit-Low Implicit (Essential Elements—Primary Disadvantages), Low Explicit-High Implicit (Attractive Elements—Secondary Advantages), and Low Explicit-Low Implicit (Non-essential Elements—Secondary Disadvantages). Finally, based on the ranking of attribute performance scores for each type of quality element, improvements and enhancements are targeted for street spatial elements that both residents and tourists consider highly important but are dissatisfied with (Figure 6d).

3.4. Questionnaire Design

Based on the established evaluation index system and the descriptive table of evaluation indicators for SD factor adjective pairs, this study quantifies and observes each indicator through carefully designed questionnaires. The design emphasizes clarity, neutrality, and logical flow to minimize biases and enhance response accuracy.

3.4.1. Questionnaire Structure and Measurement Dimension

The questionnaire adopts a modular design consisting of three parts:

- Explicit Importance Questionnaire: Based on a 5-point Likert scale [72] (5 = Very important; 4 = Important; 3 = Neutral; 2 = Unimportant; 1 = Very unimportant), residents and tourists were asked to rate their preference level for each street space element in the Sajinqiao area. The average score for each street space element serves as the measure of its explicit importance.

- Attribute Performance Questionnaire: Also using a 5-point Likert scale as the scoring basis (5 = Very satisfied; 4 = Satisfied; 3 = Neutral; 2 = Dissatisfied; 1 = Very dissatisfied), the corresponding average satisfaction score for each street space element reflects its actual performance level.

- Demographic Characteristics: On one hand, the tourist group profile includes gender, age group, education level, frequency of visits, mode of transportation, and revisit intention. On the other hand, the resident group profile includes gender, age group, education level, length of residence, and type of householder (original inhabitant/tenant/business operator).

Additionally, to examine whether significant differences exist between residents’ and tourists’ perceptions of street space elements, non-parametric independent tests were conducted using SPSS 27.0 on the ordinal scores of explicit importance and attribute performance between the two groups.

3.4.2. Data Collection and Distribution

The data collection process employed a combination of offline on-site intercept surveys and online distribution. The on-site surveys, conducted along the main street and key nodal spaces of Sajinqiao, utilized a random intercept method where surveyors approached potential respondents at randomly selected time intervals. This was designed to approximate a random sample of the population using the space. All surveys were conducted under the principles of transparency and with the informed consent of participants. The data collection spanned two months (January to February 2025), covering both weekdays and holiday periods to control for temporal variations.

A total of 400 questionnaires were distributed. After excluding invalid responses, 348 valid questionnaires were ultimately collected (162 from residents and 186 from tourists), resulting in a resident-to-tourist ratio of approximately 1:1. The effective questionnaire rate was 87.0%. (A random intercept method was used to enhance sample representativeness. The balanced resident-to-tourist ratio was designed to equally capture the perspectives of these two core user groups and facilitate robust comparison.)

3.5. Demographic Characteristics Analysis of the Respondent Groups

A statistical analysis of the basic information of the surveyed residents (Table 4) reveals the following demographic characteristics: Firstly, the gender ratio is balanced. In terms of age structure, the population is predominantly composed of young and middle-aged adults, with the 30–44 age group representing the highest proportion, followed by the 18–30 age group. Additionally, preliminary observations of the resident population suggest that age (generational differences) may also be a factor influencing perceptions of cultural values. For instance, older residents exhibit stronger attachment to traditional religious sites, while younger residents place greater emphasis on modern functional facilities. Although this study focuses on the core “residents-tourists” contrast and does not delve into demographic subgroup differences, exploring the subtle influences of factors like age and length of residence provides important directions for future research. This will aid in comprehensively understanding the diversity of local community perspectives. Regarding ethnic composition, the Hui ethnic group accounts for a significantly high percentage, reflecting the notable ethnic aggregation characteristics of the surveyed Sajinqiao area. This ethnic composition also demonstrates the continuity and stability of traditional Hui lifestyles and cultural practices in local daily life, indicating a strong inherent resilience that makes their culture less susceptible to complete assimilation by external tourists due to tourism development. Furthermore, the education level is primarily concentrated in the medium education cohort, as the combined percentage of those with high school/technical secondary school education and junior college/bachelor’s degree holders exceeds 80%. Finally, concerning householder type, local residents and business operators constitute the majority, indicating a relatively high level of community stability.

Table 4.

Basic Information Statistics of Surveyed Residents.

A statistical analysis of the basic information of the surveyed tourists (Table 5) reveals the following demographic characteristics. The gender distribution in our tourist sample is balanced (Male: 46.9%, Female: 53.1%), which aligns with the general pattern of tourism demographics where both genders actively participate in cultural tourism. The age distribution, dominated by the 18–30 (34.6%) and 30–44 (37.7%) age groups, reflects that young and middle-aged adults are the primary demographic engaging in urban cultural tourism. This sample characteristic is consistent with the profile of tourists typically attracted to historic cultural districts like Sajinqiao. A notable feature is the prominence of highly educated individuals, indicating a relatively high overall cultural level among the visitors. Geographically, tourists from within Shaanxi Province and those from outside the province each account for approximately half of the total visitors. This balanced distribution between intra-provincial and inter-provincial sources reflects a broad and diverse geographical coverage of Xi’an’s tourist market. Regarding tourism behavior, both revisit intention and recommendation willingness are significantly high, demonstrating strong recognition and satisfaction with the tourism experience. Analysis of visitor frequency reveals that repeat visitors accounted for 59.1% of total visitors, exceeding first-time visitors (40.9%), indicating the district’s sustained tourism appeal.

Table 5.

Basic Information Statistics of Surveyed Tourists.

Moreover, after conducting a one-way ANOVA analysis of variance on the raw data, the results revealed no significant correlation between revisit frequency and visitor age with any of the perceived dimensions of the Sajinqiao Historic District (p-values for all measured indicators exceeded 0.05). This indicates that within this study, the number of times visitors revisit the historic district and their age do not exert a statistically significant influence on their environmental perception evaluations.

3.6. Evaluation Criterion System Naming

To ensure the scientific validity and structural reliability of the evaluation index system, this study employed factor analysis to empirically validate the five predefined dimensions: architectural style, spatial form, street environment, cultural continuity, and spatial atmosphere. Through factor analysis, five common factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted (Table 6). These factors collectively explained 68.67% of the total variance (exceeding the 60% threshold), indicating that the scale possesses sufficient overall explanatory power to represent the information captured by the 24 items in the questionnaire.

Table 6.

Total Variance Explained.

Furthermore, the factor loading matrix is an essential component of factor analysis results, and its necessity is primarily reflected in the following two aspects:

First, the factor loading matrix objectively reflects the strength of the intrinsic relationships between observed variables (i.e., the 24 specific indicators) and latent common factors (i.e., the five perceptual dimensions). As shown in Table 7, the loadings of all indicators on their corresponding factors are above 0.5 (for example, the loadings of D1–D5 on Factor 1 range from 0.848 to 0.906), indicating that the indicators effectively represent their respective dimensions and exhibit strong convergent validity, thereby verifying the rationality of the theoretical construction.

Table 7.

Rotated Factor Loading Matrix.

Furthermore, by analyzing the distribution of rotated factor loadings, the consistency between the initial theoretical grouping and the data-driven dimensions can be verified. In this study, all indicators loaded significantly on their preset factors without notable cross-loading phenomena, demonstrating that the original division of the five dimensions based on the “physical-psychological” framework has an empirical basis, and that the index system possesses a clear structure and reliable classification.

The factor loading matrix was used to group the initial evaluation factors most closely associated with the five common factors. The results indicate that the principal components corresponding to each evaluation index align with the categorization established in Section 3.3.3, confirming the correctness of the theoretical grouping (Table 7).

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Evaluation Criterion System Analysis

To ensure the robustness of the following results, the validity and reliability of the dataset were first confirmed using standard statistical tests, as detailed below. To assess the suitability of the data for factor analysis, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were conducted [73].

The KMO test measures the sampling adequacy by comparing the magnitudes of the simple correlations between variables to the magnitudes of the partial correlations. A high KMO value indicates stronger inter-correlations among the variables; a value above 0.7 is generally considered acceptable for factor analysis, while a value below 0.5 suggests the data are unsuitable. The KMO statistic is calculated using the following formula:

From Table 8, it can be observed that in this study, the KMO test result for the resident group is 0.794, and the significance (p-value) of Bartlett’s test of sphericity is less than 0.001. For the tourist group, the KMO test result is 0.935, and the significance (p-value) of Bartlett’s test of sphericity is also less than 0.001. These results indicate strong correlations and good construct validity. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is used to measure the reliability of the questionnaire [74], and its calculation formula is as follows:

Table 8.

Questionnaire Validity Analysis.

It can be clearly observed from Table 9 that the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the overall questionnaire were 0.912 for the resident group and 0.914 for the tourist group, while the coefficients for both the satisfaction and importance sections exceeded 0.7, demonstrating high reliability of the survey instrument.

Table 9.

Questionnaire Reliability Analysis.

4.2. Analysis of Explicit Importance and Attribute Performance

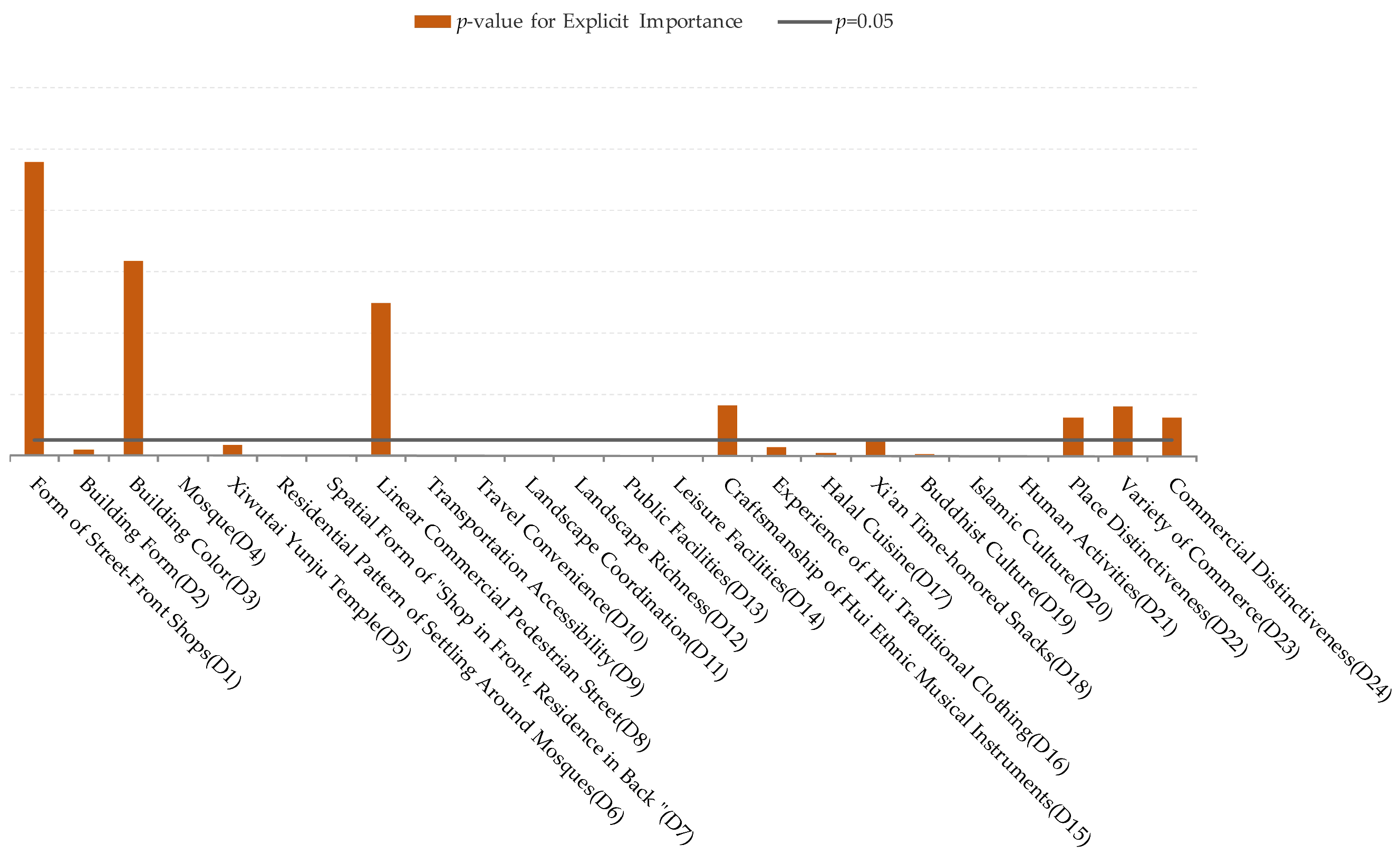

4.2.1. Analysis of Explicit Importance

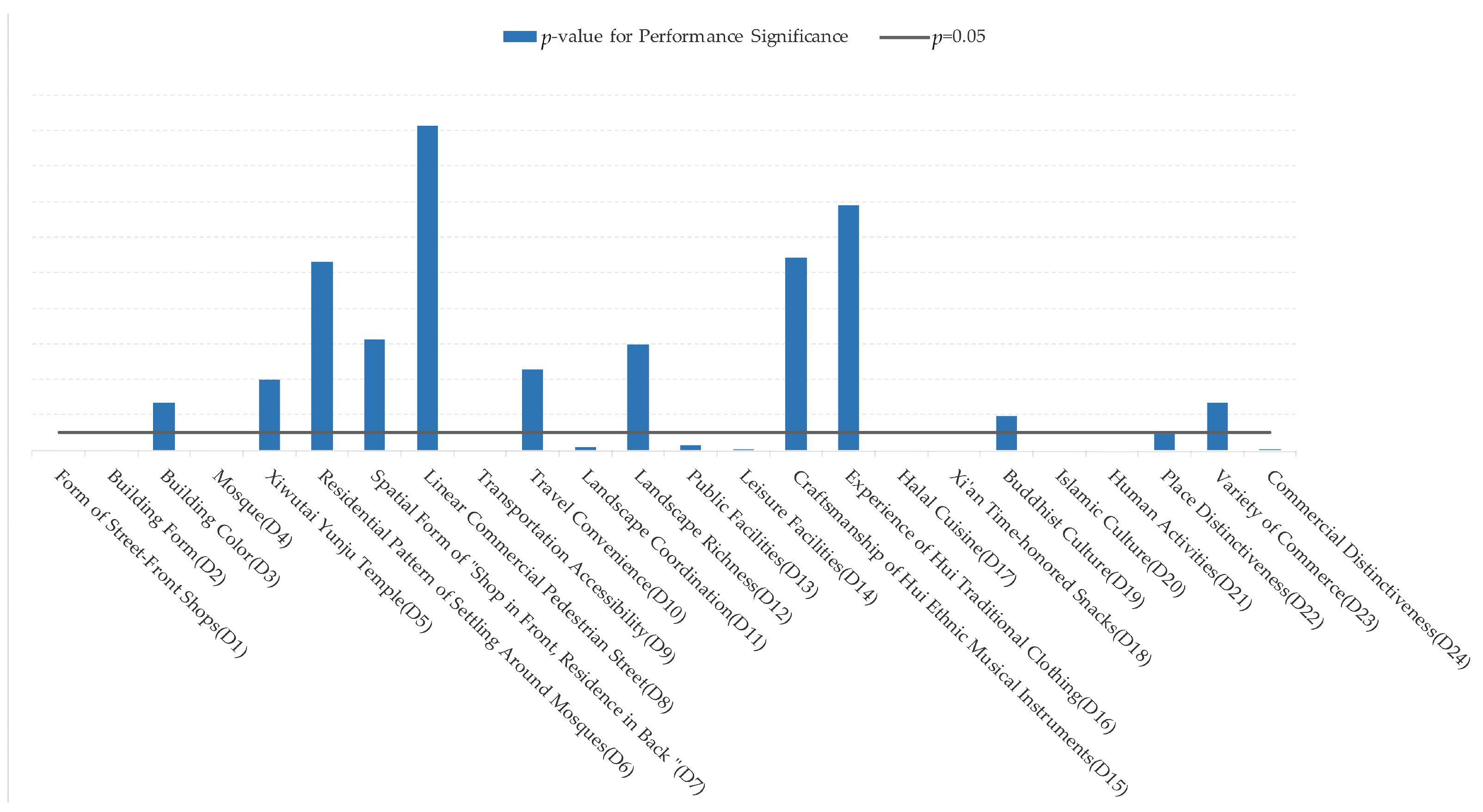

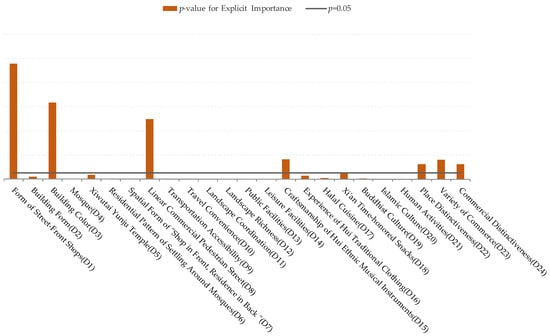

The analysis of explicit importance aims to examine whether statistically significant differences exist between residents and tourists in their perceived importance of specific street space elements. This analysis is based on the significance level (p-value) of the mean difference in importance ratings assigned by the two groups to the same element. In the corresponding graph, orange bars represent the p-values for each indicator, with a reference line set at p = 0.05. A p-value below 0.05 indicates a significant difference in the perceived importance of that element between the two groups (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Analysis of Differences in Explicit Importance between Residents and Tourists.

An intergroup analysis was conducted on the variables to examine the significance level (p-value) of differences in explicit importance. A p-value below the 0.05 reference line indicates a significant divergence in the importance evaluation of an element between the two groups. The analysis identified 11 elements exhibiting significant differences.

Among these, the following elements were rated as significantly more important by residents than by tourists: mosques, the residential pattern of settling around mosques, the spatial form of “shop in front, residence in back,” transportation accessibility, travel convenience, landscape coordination, landscape richness, public facilities, leisure amenities, Islamic culture, and human activity elements (Table 10).

Table 10.

Analysis Table of Significant Differences in Perceived Importance Between Residents and Tourists.

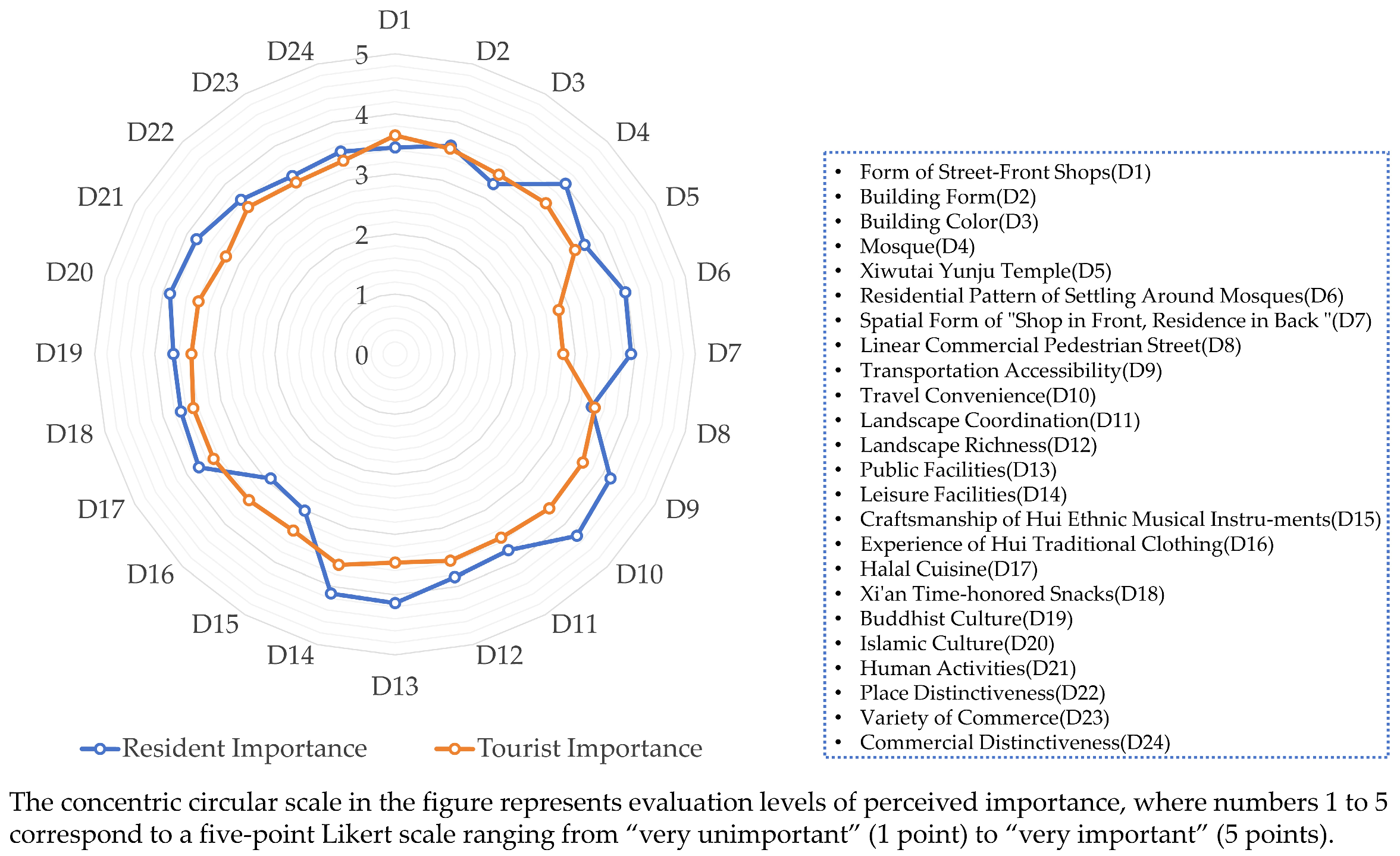

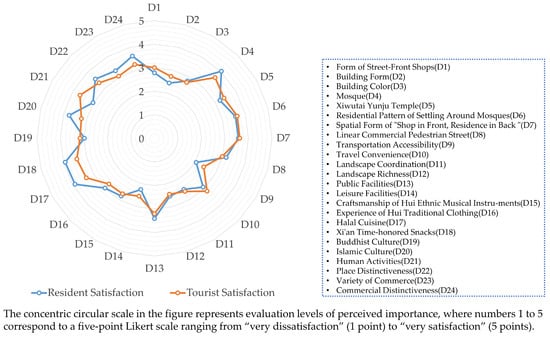

An intra-group analysis of the variables revealed that residents assigned relatively low explicit importance (below the average score of 3.13) to the following elements: the form of street-front shops, architectural morphology, building colors, transportation accessibility, travel convenience, landscape coordination, landscape richness, leisure facilities, the making of Hui ethnic musical instruments, experience of Hui traditional clothing, Buddhist culture, and human activities. In contrast, they showed a higher tendency to assign importance to other elements.

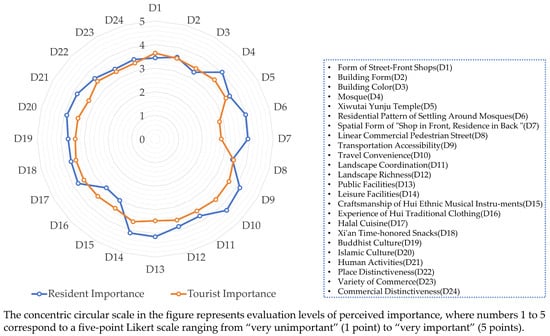

For tourists, eight street space elements were perceived with low explicit importance (below the average score of 3.41): the residential pattern of settling around mosques, the spatial form of “shop in front, residence in back,” the making of Hui ethnic musical instruments, Buddhist culture, Islamic culture, human activities, variety of commerce, and commercial distinctiveness (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Radar Chart Comparing the Explicit Importance Assigned by Residents and Tourists.

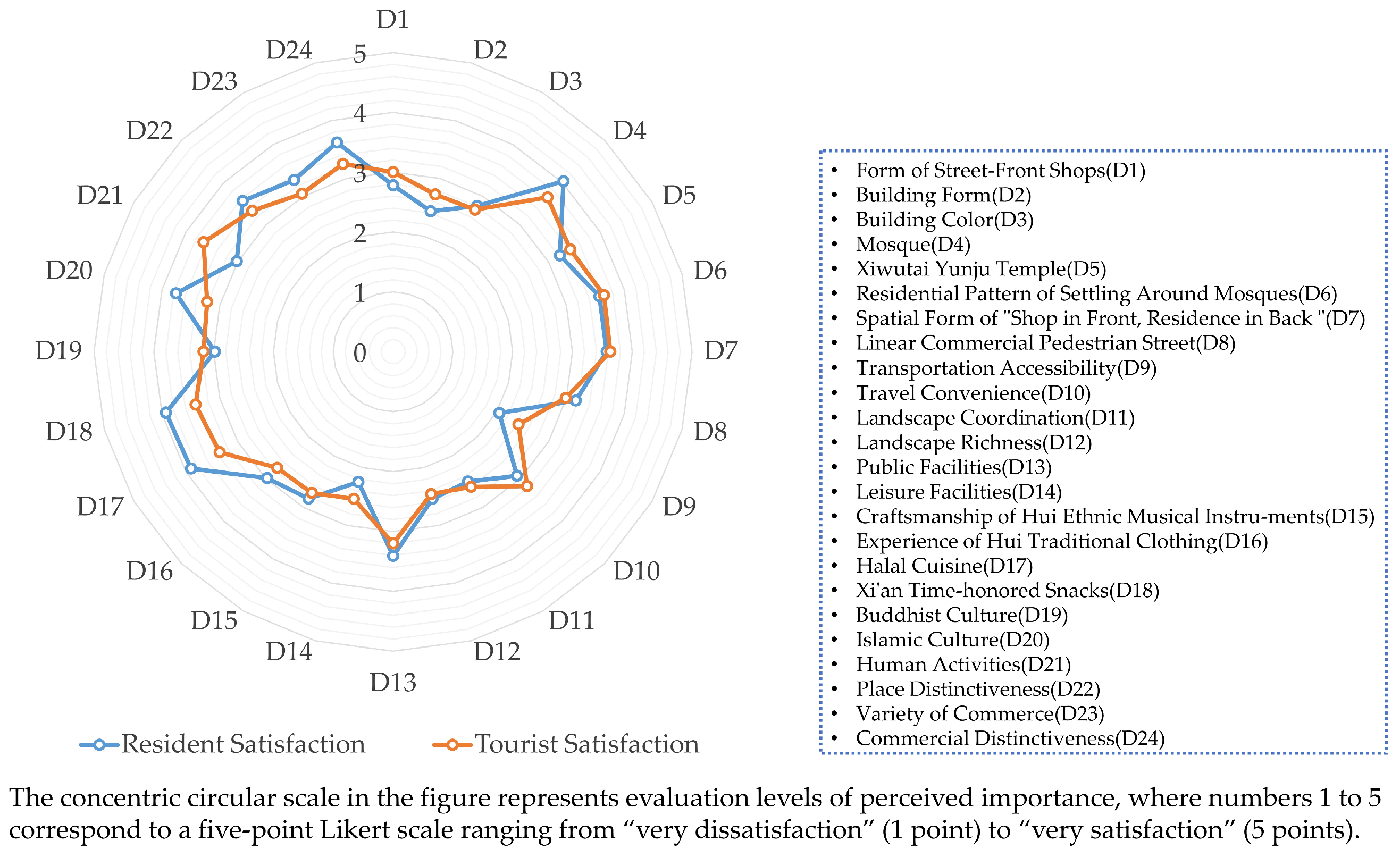

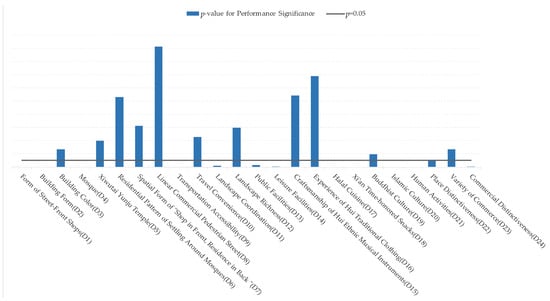

4.2.2. Attribute Performance Analysis

Attribute performance analysis (also referred to as satisfaction analysis) aims to examine whether statistically significant differences exist between residents and tourists in their actual experiential satisfaction with specific elements. This analysis is based on the significance level (p-value) of the mean difference in satisfaction ratings assigned by the two groups to the same element. In the corresponding graph, blue bars represent the performance significance p-values for each indicator, with a reference line set at p = 0.05. A p-value below 0.05 indicates a significant difference in experiential satisfaction regarding that element between the two groups (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Analysis of Significance Differences in Attribute Performance between Residents and Tourists.

Among these elements, the importance ratings for Halal cuisine, Xi’an time-honored snacks, and Islamic cultural elements were significantly higher among residents than among tourists (Table 11).

Table 11.

Analysis of Differences in Attribute Performance between Residents and Tourists.

An intra-group analysis of the variables reveals that both residents and tourists express relatively high satisfaction with approximately half of the street space elements. Specifically, elements such as the residential pattern of settling around mosques, the spatial form of “shop in front, residence in back,” Halal cuisine, Xi’an time-honored snacks, Islamic culture, place distinctiveness, and commercial characteristics received consistently high satisfaction ratings from both groups. Notable differences in satisfaction priorities emerged between the two groups. Residents reported higher satisfaction levels (above the average score of 3.13) with elements including mosques, the Xiwutai Yunju Temple, linear commercial pedestrian streets, landscape richness, and variety of commerce. In contrast, tourists assigned higher satisfaction scores (above the average of 3.08) to transportation convenience, public facilities, Buddhist culture, and human activities. These distinctions highlight the divergent priorities and experiential focuses of residents and tourists within the same spatial context (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Radar Chart Comparing Attribute Performance between Residents and Tourists.

4.3. Element Quality Analysis

4.3.1. Extraction of Implicit Importance

Explicit importance refers to the direct evaluation of the significance of street space elements by residents and tourists, while implicit importance reflects the underlying significance derived indirectly from users’ evaluations of other aspects. Although interrelated, explicit and implicit importance are distinct concepts. Their integration through quadrant-based analysis enables a comprehensive measurement of element quality.

Using SPSS 27.0 statistical software, correlation analysis was conducted on the bivariate data of explicit importance and attribute performance for both residents and tourists (Table 12). The correlation coefficients obtained from this analysis serve as quantitative indicators of implicit importance for different elements. A higher absolute value of the correlation coefficient indicates a stronger implicit importance of the element, revealing its latent impact on overall satisfaction beyond directly stated preferences.

Table 12.

Correlation between Explicit Importance and Attribute Performance Satisfaction.

Within the resident group, 14 street space variables exhibited a statistically significant correlation (p < 0.05) between explicit importance and attribute performance satisfaction (Table 12). These variables include: form of street-front shops, architectural morphology, building colors, Xiwutai Yunju Temple, residential pattern of settling around mosques, spatial form of “shop in front, residence in back,” transportation accessibility, travel convenience, landscape coordination, landscape richness, public facilities, leisure amenities, Buddhist culture, and human activities.

Among these, the absolute correlation coefficient |r| for Xiwutai Yunju Temple and travel convenience fell within the range of 0.3 to 0.5, indicating a low but significant correlation. The |r| values for the other 12 elements were below 0.3, suggesting a weak significant correlation. This implies that an improvement in either the explicit importance or attribute performance satisfaction for these elements could potentially lead to an improvement in the other. For the remaining street space elements within the resident group, the correlation coefficients |r| were below 0.15 (p > 0.05), indicating no significant correlation and thus low implicit importance (Table 13).

Table 13.

Implicit Importance of Street Space Elements Perceived by Residents and Tourists (Expressed by Correlation Coefficient |r|).

Within the tourist group, 15 street space variables showed a significant correlation (p < 0.05) between explicit importance and attribute performance satisfaction (Table 12). These variables are form of street-front shops, architectural morphology, building colors, Xiwutai Yunju Temple, residential pattern of settling around mosques, spatial form of “shop in front, residence in back,” linear commercial pedestrian streets, transportation accessibility, travel convenience, landscape coordination, landscape richness, leisure amenities, craftsmanship of Hui ethnic musical instruments, experience of Hui traditional clothing, and human activities.

Among these, the absolute correlation coefficient |r| for four elements—travel convenience, public facilities, Halal cuisine, and Xi’an time-honored snacks—fell within the range of 0.3 to 0.5 (p < 0.05), indicating a low significant correlation. The other correlated elements demonstrated a weak significant correlation (|r| < 0.3, p < 0.05) (Table 13).

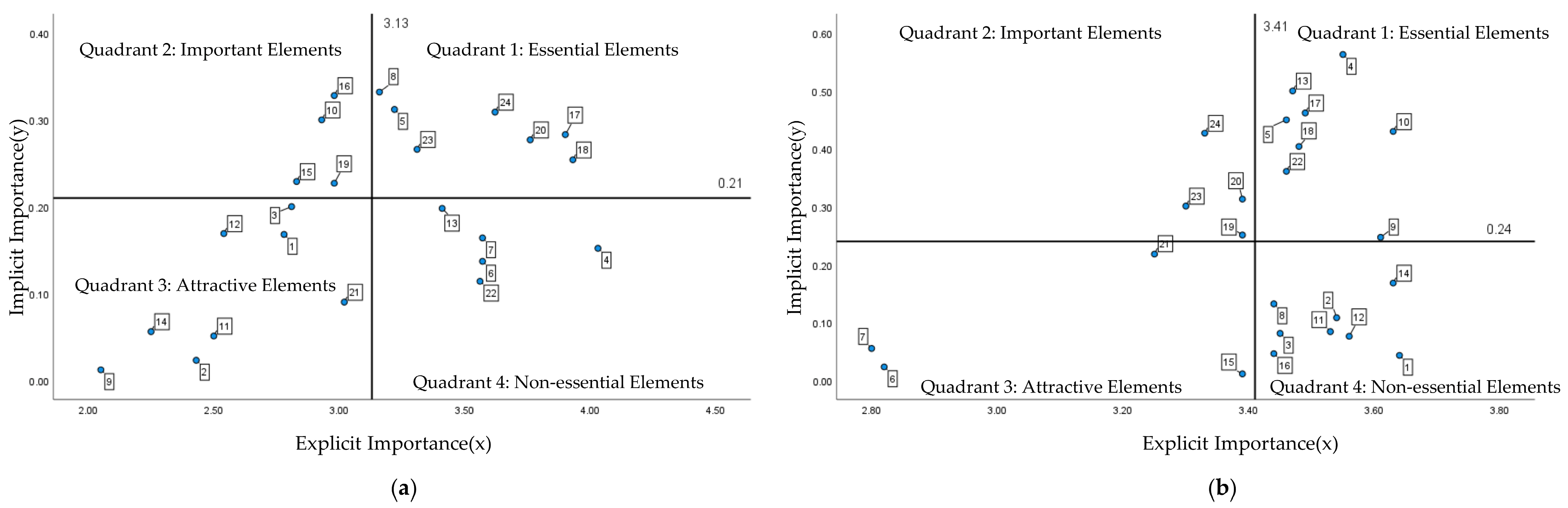

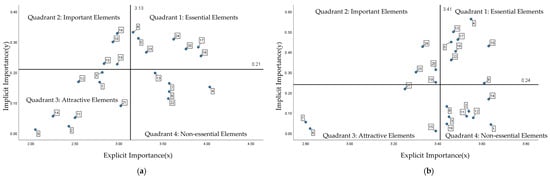

4.3.2. Quality Measurement Analysis

The IPA-KANO quality measurement quadrant is used to visualize the relationship between explicit and implicit importance. Weighted averages of the implicit importance |r|-values—derived from the correlation between explicit importance and attribute performance—are calculated separately for residents and tourists. The horizontal axis represents explicit importance, while the vertical axis represents the average implicit importance. Using the mean values of explicit and implicit importance for residents and tourists as the origin of the quadrant (Figure 11), the essential elements, important elements, and attractive elements of the street space are identified from the perspectives of both residents and tourists.

Figure 11.

IPA-KANO Quality Measurement Model: (a) Quality Measurement Analysis of Street Space Elements from the Resident Perspective; (b) Quality Measurement Analysis of Street Space Elements from the Tourist Perspective. (The numbered labels in the figure correspond to the numerical codes for each D-level indicator).

As can be seen from the data in Table 14, the essential elements for residents are centered on religion and daily living infrastructure, highlighting the spirit of place and community identity, whereas for tourists, they focus on transportation and cultural landmarks, pursuing convenience and symbolic experiences. Attractive elements for both groups revolve around cultural uniqueness, while non-essential elements reflect their differentiated demands for functionality and esthetics. By integrating physical, psychological, and conscious perception, the street space of Sajinqiao not only sustains the traditional life of residents but also provides tourists with a multi-dimensional cultural immersion experience.

Table 14.

Quality Measurement of Street Space Elements in Sajinqiao from Resident and Tourist Perspectives.

- 1.

- Analysis of Essential Elements

- Commonality: Both residents and tourists regard elements that carry cultural significance and provide basic functions within the street space as essential. Residents emphasize cultural landmarks such as mosques (D4) and public facilities (C13), while tourists focus on the presentation of street features like architectural form (D2). This is because cultural landmarks convey regional heritage, and basic functional elements satisfy both daily living and tourism needs, forming the foundation for perceiving street identity and ensuring fundamental experiences.

- Difference: The essential elements for residents revolve around spatial patterns closely linked to daily life, such as “settling around mosques (D6)” and “shop in front, residence in back (D7)”, which stem from the spatial dependency formed through long-term habituation. In contrast, tourists prioritize intuitively perceptible elements related to the tourism experience, such as the form of street-front shops (D1), as first-time visitors require quickly constructing an understanding of the street’s character, whereas these elements represent the everyday cultural environment for residents.

- 2.

- Analysis of Important Elements

- Commonality: Important elements for both groups encompass distinctive commercial offerings (e.g., Halal cuisine D17, Xi’an time-honored brands D18) and cultural experiences (e.g., Islamic culture D20). This is because commerce serves as a vital carrier of street vibrancy and local culture, while cultural experiences deepen the unique perception of a space. Whether for enriching the daily lives of residents or enhancing the tourism experience for visitors, both require the support of commercial and cultural elements.

- Difference: Important elements for residents include cultural spaces like the “Xiwutai Yunju Temple (D5)”, which represent an extension of their daily spiritual and life scenes. Tourists, conversely, prioritize “transportation accessibility (D9) and travel convenience (D10)”. This is because efficient movement between attractions is crucial for tourists, significantly impacting the smoothness of their itineraries. In contrast, residents, with their fixed daily travel routes, exhibit less reliance on these specific transportation elements.

- 3.

- Analysis of Attractive Elements

- Commonality: Attractive elements for both groups involve the extension of cultural experiences (e.g., experience of Hui traditional clothing D16, Buddhist culture D19) and distinctive activities (e.g., human activities D21). These components break through routine experiences by adding interest to residents’ daily lives and creating unique memory points for tourists, thereby activating the appeal and vitality of the street space.

- Difference: The attractive elements for residents are associated with content characterized by daily participation and local life ambiance, such as “travel convenience (D10)” and “craftsmanship of Hui ethnic musical instruments (D15)”, representing a fresh exploration of the familiar environment. In contrast, tourists focus on elements exclusive to tourism that are suitable for sharing, such as “place distinctiveness (D22)”, pursuing unique experiences within limited tour time, which differs from the residents’ immersive, daily-life perception.

- 4.

- Analysis of Non-essential Elements

- Commonality: Non-essential elements primarily consist of external architectural forms (e.g., street-front shop forms D1, architectural morphology D2) and certain auxiliary transportation or landscape items (e.g., transportation accessibility D9, landscape coordination D11). This is because these elements have an indirect impact on both the daily functional needs of residents (already adapted to their lifestyle rhythms) and the core experience of tourists (focused on culture, commerce, and unique activities), thus not being key to perceiving the value of street space.

- Difference: Residents rated “human activities (D21)” as non-essential, as they are accustomed to such daily occurrences and these activities cause little disruption to their living space functionality. In contrast, tourists pay less attention to resident lifestyle patterns such as “settling around mosques (D6)” and “shop in front, residence in back (D7)” because their focus during visits is on content that can be directly translated into experiential gains; the daily living scenes of residents do not constitute a core part of their tourism appeal. This differs from the residents’ familiarity and relative indifference towards their own living environment.

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Findings

This study systematically analyzed the perceptual characteristics of the Sajinqiao Historic District through a multi-dimensional evaluation system, revealing significant differences in the perception of street space between residents and tourists. The results indicate that residents place greater importance on elements related to religious sites and community living patterns, with their level of emphasis being significantly higher than that of tourists. In contrast, tourists show stronger concern for elements associated with transportation convenience and commercial vitality. Further analysis demonstrates that tourists’ actual satisfaction with visual elements such as street-facing building appearances is significantly lower than that of residents. Additionally, both groups report relatively low satisfaction levels with cultural experience elements, reflecting insufficient depth in the district’s cultural presentation. These findings highlight the structural differences in spatial perception between different user groups, providing important insights for the refined management and quality enhancement of historic and cultural districts.

5.2. Comparative Analysis of Existing Studies

This study, focusing on the perception of street space in the Sajinqiao Historic District, shares common ground with previous research while also achieving innovative breakthroughs, as detailed below.

Similar to earlier studies [75,76], this research also identified significant differences in the focus of spatial perception among different groups due to their cultural backgrounds and usage needs. Specifically, religious sites and community living patterns exerted a stronger attraction for residents, while architectural style, spatial layout, street environment, and commercial atmosphere significantly influenced tourists’ perceptual evaluations, confirming the fundamental importance of the physical street space to the tourism experience.

Unlike previous studies that often relied on a single IPA method to assess tourist satisfaction or investigated the psychological and behavioral perceptions of either tourists or residents from a single dimension, this study adopts an integrated approach. It combines an improved IPA-KANO model with a dual-group questionnaire survey method, simultaneously incorporating both residents and tourists into the research framework.

By comprehensively considering element importance, attribute performance, and the classification and prioritization of user needs, this approach allows for a more holistic and precise dissection of the perceptual differences between the two groups. For instance, the analysis reveals that residents’ long-term lived experiences and the emotional attachments formed thereby influence their spatial evaluation, leading them to emphasize residential patterns, religious buildings like mosques, and community infrastructure, and to assign significantly higher importance to cultural continuity elements. In contrast, tourists are more susceptible to immediate environmental experiences and visual elements, focusing on transportation convenience and cultural landmarks, which clearly correlates their satisfaction deeply with travel ease and the depth of cultural experiences.

Based on the perceptual study of residents and tourists, this research can provide more targeted design strategies for the spatial optimization of the Sajinqiao Historic District, contributing to the inheritance of historical culture and the improvement of spatial quality while balancing the living needs of residents and the tourism experience of visitors.

5.3. Optimization and Enhancement Strategies

Based on the IPA-KANO model analysis, which reveals differences in needs and satisfaction levels between residents and tourists regarding street space elements in the Sajinqiao Historic District, the following optimization strategies for essential elements are formulated from a dual-perspective approach:

- Optimization Strategies from the Resident Perspective

Optimization from the resident perspective should focus on enhancing daily convenience and community identity. First, maintain and repair mosques to ensure their function for religious activities, and add related cultural activities to strengthen residents’ sense of community identity. Second, preserve the unique spatial patterns of “settling around mosques” and “shop in front, residence in back,” while improving infrastructure such as water supply, power supply, and drainage to optimize the living and business experience. Third, increase the provision of public facilities, such as densifying the distribution of seating, trash bins, and lighting, to facilitate daily life. Finally, add cultural signage and historical information boards to highlight the district’s cultural characteristics and deepen residents’ sense of belonging.

- Optimization Strategies from the Tourist Perspective

Optimization from the tourist perspective should focus on enhancing cultural experiences and travel convenience. On one hand, it is essential to upgrade street-front shops by unifying signage styles and adding greenery to highlight the distinctive character of the historic district, while simultaneously preserving the historical appearance of buildings through regular maintenance and repairs to ensure their exterior and colors align with the overall style and avoid excessive modernization [77]. On the other hand, increasing rest areas and green belts along commercial pedestrian streets will improve comfort and safety, supplemented by adding green landscapes and leisure facilities (such as seating and pavilions) to optimize the tourism experience.

These perspective-specific optimization strategies aim to balance the authenticity of residents’ daily lives with the attractiveness of cultural experiences for tourists. This approach enables the Sajinqiao Historic District to accurately address the needs of both residents and tourists while steadfastly preserving its historical and cultural character, thereby enhancing satisfaction for both groups.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study provides a systematic analysis of the perceptual characteristics of street space in the Sajinqiao Historic District, several aspects warrant further refinement.

Precisely because Xi’an is a world-renowned historical and cultural city and the starting point of the Silk Road, its tourism appeal exerts a global influence. Visitors to the city exhibit extensive diversity and universality in terms of scale, geographic origin, and demographic composition. As a quintessential example of Huizhou-Han cultural integration, the Shajinqiao Historic District, thanks to its diverse visitor reception system, serves as an ideal setting for studying perceptual differences among visitors and residents from diverse backgrounds. This study focuses on the street spaces within the district that combine residential and tourism functions. Through large-scale questionnaire surveys of local residents and domestic/international tourists, it covers diverse sample groups varying in age, education level, travel frequency, and cultural background. This approach enables a relatively comprehensive revelation of the universal patterns and specific characteristics of intersubjective perceptual differences.

It should be noted, however, that due to significant variations among historical tourism cities in cultural foundations, spatial forms, tourism development intensity, and community structures, the applicability of this study’s conclusions—derived from the Sajinqiao case—to other types of historic districts (e.g., purely commercial, heritage preservation, or religious sites) requires validation through cross-regional comparative analysis in future research. Future research will focus on in-depth studies of historic districts with distinct functional roles and cultural characteristics, thereby enhancing the theoretical framework’s adaptability and practical guidance value.