Abstract

Traditional dwellings in southern Xinjiang, exemplified by the Suohema House, have evolved as adaptive responses to the region’s cold and arid climatic conditions, providing thermally comfortable living environments with relatively low energy consumption. Learning from these climate-responsive design strategies offers an effective approach to reconciling the conflict between energy efficiency and indoor comfort. Such exploration is of great significance for preserving regional architectural identity and promoting the development of low-carbon buildings. This study establishes a performance-driven morphological multi-objective optimization framework for traditional dwellings, taking building energy consumption, thermal comfort, and indoor temperature as the primary optimization objectives. The framework integrates parametric modeling, performance simulation, and multi-objective optimization within the Rhino & Grasshopper platform, employing a genetic algorithm to achieve performance-oriented design exploration. Key design variables were identified through data analysis, and the influence weights and prioritization of morphological parameters were quantified. The results reveal that the room depth in residential dwellings (4.57–4.73 m), room width (3.97–6.75 m), room clear height (2.33–2.42 m), wall thickness (lower wall thickness ranging from 1.14 to 1.22 m, upper wall thickness at 0.76 m), and building orientation (true south) have significant impacts on both energy consumption and indoor thermal performance. Based on these findings, adaptive optimization strategies were proposed from three perspectives: scale optimization, spatial hierarchy refinement, and enhancing the performance of building envelopes. The proposed framework provides methodological guidance for the conservation and adaptive renewal of traditional dwellings, as well as for the design of new, green, and low-carbon residential buildings suited to the climatic conditions of southern Xinjiang.

1. Introduction

The construction industry accounts for about 40% of total energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions [1]. Against the backdrop of the “dual carbon” goals and the rural revitalization strategy, energy conservation and emission reduction in the construction sector are of critical importance. In China, energy consumption in rural areas is a significant source of carbon emissions [2]. Due to the lack of scientific and reasonable guidance for new residential buildings, there are certain deficiencies in low-energy buildings in rural areas [3]. However, traditional rural dwellings, which have been in harmony with the climate and environment for hundreds of years, have developed architectural forms that can skillfully respond to the climate, meet basic comfort needs [4], and are in line with local resources and economic levels. The climate adaptability and passive design strategies embodied in the forms of traditional rural dwellings are regarded as valuable sources of inspiration for contemporary green and low-carbon building design [5]. It has become a consensus in the construction field that achieving energy conservation and emission reduction in buildings through reasonable architectural forms and appropriate passive climate regulation strategies is the most direct and effective approach [6,7]. Against this backdrop, architects need to have a deeper understanding of the impact of architectural forms on various performance aspects in order to make effective design decisions [8]. Therefore, investigating the relationship between traditional dwelling forms and the climatic environment, to systematically analyze its morphological characteristics, and to reveal the underlying generative logic. Such analysis retains practical reference value for contemporary rural construction [9].

2. Research Background and Literature Review

With the acceleration of urbanization and the advancement of the national demonstration project for the concentrated and contiguous protection and utilization of traditional villages, there is an urgent need to investigate the morphological characteristics of traditional dwellings, transform the climate-adaptive experiences they contain into quantifiable design parameters and convertible passive design strategies, so that the climate-adaptive experiences they embody can be effectively transmitted and applied in modern architectural design, renovation, and transformation, thereby providing guidance for the construction and renovation of local dwellings. This is of great significance for inheriting regional characteristics, promoting architectural culture, and promoting the development of low-carbon architecture. It also contributes Chinese wisdom to the protection and development of traditional dwelling forms in extreme arid regions.

An increasing number of studies have focused on providing scientific guidance for rural building design and construction. Considerable research has been conducted on traditional dwellings in northwestern China. Existing studies have primarily concentrated on summarizing green building principles and construction methods [10,11], analyzing morphological features and experiential knowledge [12,13], translating spatial forms into contemporary applications [14,15], or validating the effectiveness of vernacular forms in responding to the climatic environment through numerical simulations and measured thermal performance [16,17,18,19]. These studies have laid a solid foundation for understanding the ecological value of traditional dwellings.

With technological advances, scholars have begun exploring the application of genetic algorithms within parametric design platforms in urban environments [20], residential buildings [21,22,23], neighborhoods [24,25,26], and building components [27]. These studies have elucidated the coupling mechanisms between form and climate and identified optimal ranges for morphological parameters under multiple performance objectives [28]. This marks a shift in research methods from empirical induction and single verification to generation and optimization paradigms, providing new ideas and methods for the study of traditional residential forms’ climate adaptability. Although multi-objective optimization methods have matured in the context of urban and architectural form generation, their application to traditional dwellings in China’s extremely arid western regions remains limited [29]. In particular, the issue of how to optimize the form of oasis dwellings to cope with the impact of cold and arid climates remains unsolved.

Based on this, this study takes the traditional South Xinjiang residence, the Suhema House, as the research object. It is characterized by rammed-earth partition walls, gently sloping soil-covered roofs, and thick walls with small window openings. It is the result of an intuitive response and ingenious adaptation to the harsh local climate (cold in winter and dry hot in summer). Its low-tech, multi-benefit features hold significant value for contemporary re-evaluation. This study aims to employ genetic algorithms to construct a multi-objective optimization framework. This framework addresses the challenge of balancing and optimizing morphological parameters under multiple performance objectives, thereby providing scientific guidance for residential construction and low-carbon development in the region.

The innovations of this study are threefold:

- (1)

- A performance-driven multi-objective optimization framework for traditional dwellings is proposed, enabling feedback and adjustment between dwelling morphology and building performance.

- (2)

- Transforming the vague “regional characteristics” of traditional dwellings into a quantifiable set of climate-adaptive morphological features, the influence weights and prioritization of morphological parameters on energy consumption and indoor thermal environment are quantified, addressing the lack of quantitative analysis in previous research on vernacular morphology.

- (3)

- Hierarchical optimization strategies for the Suohema House morphology are developed, aiming to enhance its adaptability to cold and arid climates without compromising the traditional style.

3. Research Approach and Methodology

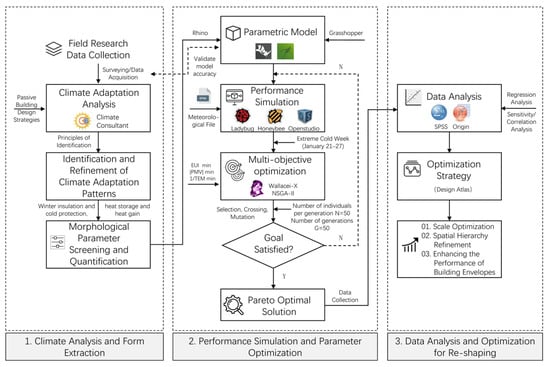

3.1. Research Methods Framework

This study establishes a hierarchical research framework consisting of three sequential steps: climate analysis and morphological extraction, performance simulation and algorithmic optimization, and data analysis and formulation of optimization strategies (Figure 1). First, based on field surveys and climate analysis, the morphological characteristics of the dwellings are identified, and relevant morphological indicators and their parameter ranges are extracted to construct a parametric model. Second, performance simulation and multi-objective optimization are conducted to generate an overall set of relatively optimal morphological schemes. Finally, the resulting data are analyzed to determine the influence weights and prioritization of each morphological parameter. On this basis, optimized design strategies for dwelling morphology are proposed.

Figure 1.

Research Framework.

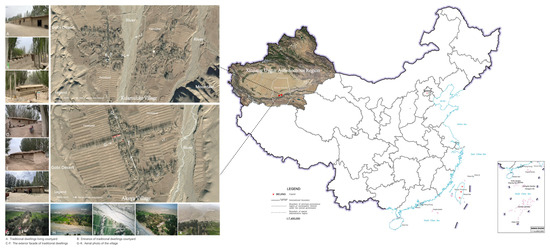

3.2. Study Area Overview

The traditional Suohema House is primarily distributed in the Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture of Xinjiang, specifically within two national-level traditional villages—Kulamuluke Village and Akeya Village in Kuerlemuoleke Township, Qiemo County (Figure 2). These villages are situated on the northern slopes of the Kunlun Mountains, at the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert, representing a transitional zone between highland and Gobi environments. This location features unique climatic and geographic conditions and is highly sensitive to climate variability. Both villages have largely preserved their original settlement patterns. The Suohema Houses are densely clustered, maintaining strong vernacular characteristics, harmonious integration with the natural environment, and a well-preserved pastoral landscape. The villages exhibit simple local customs and abundant grasslands, reflecting the close interplay between human settlement and the surrounding environment. Given the particularity and complexity of the environment, coupled with the unique characteristics of traditional dwelling forms, it is essential to conduct an in-depth exploration of the architectural features of vernacular housing in this region and propose adaptive optimization strategies. This approach is crucial for rural revitalization and the advancement of ecological civilization.

Figure 2.

Study Area.

3.3. Data Sources

Morphological data were collected from 33 representative Suohema Houses with typical forms and clear layouts, located in the two national-level traditional villages of Akeya and Kulamuluke. Surveying and measurement data were specifically obtained from 10 well-preserved Suohema Houses to ensure accuracy and completeness. Climatic data were derived from the Typical Meteorological Year (TMYx) dataset for Qiemo County (https://www.ladybug.tools/epwmap/ (accessed on 26 June 2025)), representing local climate conditions for performance simulation and analysis.

3.4. Climate Adaptation Analysis

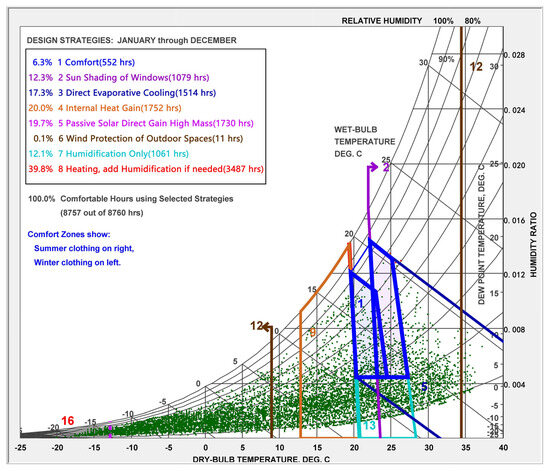

Climate adaptation analysis constitutes the first step in understanding the performance of traditional dwellings. This study employed Climate Consultant as the climate analysis tool and adopted the widely used 2005 ASHRAE dynamic comfort model [30,31] to integrate outdoor meteorological conditions, human thermal comfort requirements, and building design strategies. Combined with field investigations, the analysis identified the local climate characteristics: high solar radiation, low temperatures, frequent wind and sand, limited rainfall, and large diurnal temperature variations. The coldest period occurs from December to February, while peak summer temperatures occur in July and August.

The enthalpy-humidity chart for local residential buildings (Figure 3) indicates that thermal comfort is limited to 6.3% of the year. Over 40% of the time, active heating is required. Considering that internal heat sources such as electrical appliances are minimal in traditional dwellings, removing the internal heat gain option (20%) shows that the actual effective time requiring active heating exceeds 60%.

Figure 3.

Year-Round Climate Environment Analysis of Qiemo.

Based on the combination of passive strategies, the four most effective passive measures are identified: passive solar heating with high thermal mass (19.7%), direct evaporative cooling (17.3%), window shading (12.3%), and simple humidification (12.1%). Considering site-specific microclimatic characteristics, thermal performance requirements, and climate analysis results, insulation emerges as the primary concern. Passive solar heating with high thermal mass significantly improves indoor thermal conditions during spring, autumn, and winter, while window shading, evaporative cooling, and simple humidification are most effective in summer.

3.5. Morphological Feature Extraction

Climate has always been a key variable influencing traditional dwellings, and the generative logic of their morphology is closely related to local climatic conditions [32,33], while also being shaped by regional culture, resource endowment, and socioeconomic factors. Morphology not only represents the result of climate adaptation and environmental regulation [34] but also serves as an important means and medium for such regulation. Traditional dwellings ingeniously guide, capture, regulate, and block the flow of natural energies (such as light, heat, and wind) through their physical spaces, perfectly embodying the ecological wisdom that ‘form follows climate’ [35].

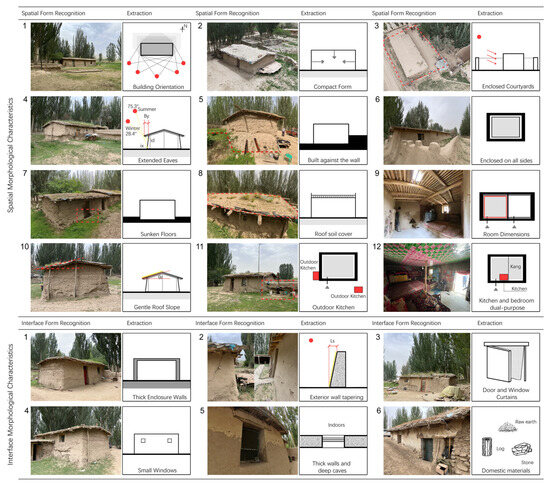

Under this theoretical framework, identifying and extracting climate-responsive characteristics of vernacular dwellings becomes a prerequisite for preserving and developing climate-adaptive practices. To this end, this study draws on Liu Peilin’s [36] identification principles of “landscape genes”, integrating its core concepts with theories of architectural climate adaptability [37,38]. Four specific identification principles (Table 1) are proposed to guide the selection and extraction of vernacular morphological features. Guided by these principles, we systematically analyzed field survey samples. Each preliminarily identified morphological characteristic was cross-referenced against the principles to validate its climatic responsiveness and regional distinctiveness. Subsequently, 18 morphological characteristics of Sohuma residential architecture were identified and extracted across two dimensions: spatial form and interface form (Figure 4).

Table 1.

Principles for Identifying Climate-Responsive Morphological Features of Traditional Dwellings.

Figure 4.

Identification and Extraction of Morphological Characteristics in Suohema Fang Traditional Houses.

Based on the extracted morphological features, key design parameters were further identified and their thermal processes analyzed. Statistical analysis was performed on the collected survey data, and parameter ranges were determined according to the observed minimum and maximum values (Table 2).

Table 2.

Morphological indicators and their value intervals.

- (1)

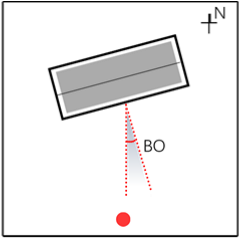

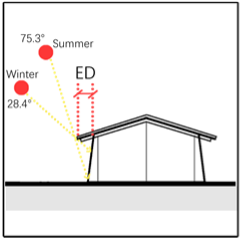

- The “building orientation” design parameter refers to the main orientation of the building. An appropriate orientation maximizes solar gain, enhancing daylighting and passive heating, while avoiding the prevailing winter winds to reduce direct cold air impact and heat loss due to air infiltration.

- (2)

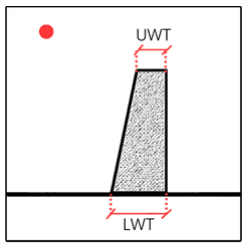

- The design parameters for “thick enclosure” and “exterior wall tapering” are the widths at the top and bottom of the wall. Rammed-earth walls store daytime heat, effectively suppressing external temperature fluctuations, stabilizing interior surface temperatures [39], and mitigating cold wind infiltration.

- (3)

- The design parameter of “extended eaves” is the depth of the eaves. Eaves shield exterior walls from winter winds, reducing heat exchange between indoors and outdoors, and preventing excessive solar heat gain in summer. The shaded area beneath the eaves also creates a transitional space that buffers indoor–outdoor temperature differences.

- (4)

- The design parameters of “small windows” and “thick walls and deep caves” are the window-to-wall ratio. Window size affects daylighting and heat transfer, while minimizing cold wind infiltration and convective heat loss.

- (5)

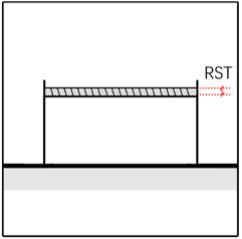

- The design parameter of “roof soil cover” is the thickness of the roof soil layer. The thermal inertia of the soil delays heat transfer through the roof, reducing indoor heat loss in winter and blocking external heat in summer.

- (6)

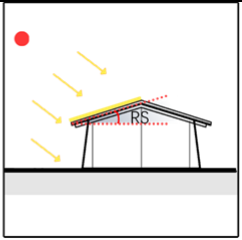

- The design parameters of a “gentle slope roof” are the roof slope. It increases the effective surface area for solar radiation while maintaining wind resistance.

- (7)

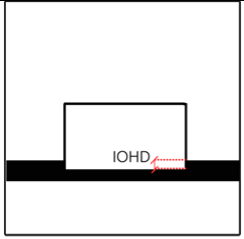

- The design parameters of “sunken floors” are the indoor–outdoor height difference. This utilizes the stable temperature of underground soil to moderate indoor floor temperatures.

- (8)

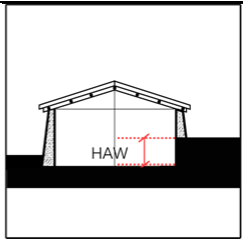

- The design parameter of “built against the wall” is the height against the wall. Utilizing the thermal mass of the ground or mountains enhances insulation and reduces convective heat loss on windward facades.

- (9)

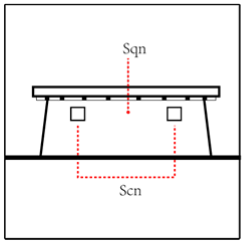

- The design parameters of “enclosed courtyards” are the width and length of the courtyard. These affect solar exposure and natural ventilation, thereby influencing heat exchange between indoors and outdoors.

- (10)

- The design parameters of “room dimensions” and “compact form” are the room’s width, depth and clear height. These influence indoor ventilation and internal heat transfer and storage.

3.6. Design Conditions

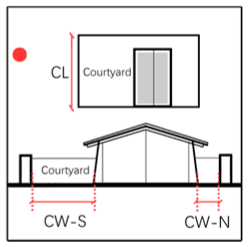

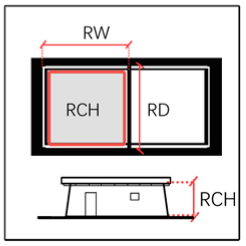

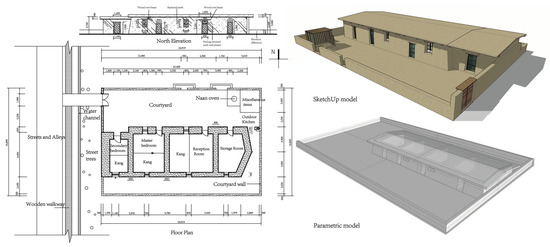

Due to space limitations, this study adopts the commonly found four-room layout as the basic typology (Figure 5). A parametric model was developed using Rhino and Grasshopper software, The Rhino version used was 7.4.21067.13001, and the Grasshopper version was 1.0.0007.

Figure 5.

Building Parameter Information.

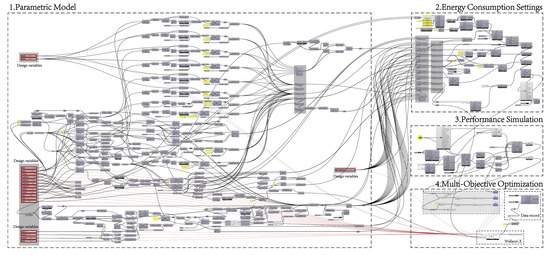

Sixteen parameters (Table 2), including building orientation, window-to-wall ratio, room dimensions, eave depth, and wall thickness, were set as independent variables to enable dynamic control of the building form. Indoor mean temperature (TEM), thermal comfort (PMV), and building energy consumption (EUI) were designated as dependent variables. Compared with other seasons, indoor thermal comfort issues are particularly prominent in winter; therefore, the study focuses on the local extremely cold week (21–27 January). The optimization objectives were defined as follows: (1) maximizing indoor mean temperature, to directly reflect the dwelling’s passive heating performance; (2) the Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) approaches zero, serving to evaluate thermal comfort in residential buildings during extremely cold climatic conditions; and (3) minimizing building energy consumption, to represent overall energy efficiency during the extremely cold week.

Energy consumption simulations were conducted using the OpenStudio simulation engine (version 1.8.0), while PMV and indoor mean temperature were calculated using the Ladybug Tools plugin suite (version 1.8.0). For multi-objective optimization, the Wallacei-X optimizer was employed [40,41], which integrates the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II)—selected for its high prevalence [20], strong reliability [42], computational efficiency [43], and stability [44]—to perform iterative optimization. The simulation and optimization workflow is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Flow chart of parametric simulation optimization platform.

The Wallacei-X parameters were adopted based on commonly used settings in previous studies [45,46] (Table 3). Since Wallacei-X treats solutions approaching the minimum value as optimal by default, the objective functions were adjusted to ensure consistency: indoor temperature was expressed as its reciprocal, and PMV as its absolute value, thereby converting the problem of maximizing indoor temperature and the Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) approaches zero into a minimization problem [47].

Table 3.

Genetic Algorithm Parameter Settings for Wallacei-X.

In this study, multi-objective optimization is primarily achieved through adjustments of the building’s morphological parameters. Therefore, the thermal performance parameters of the building envelope were set according to the limits on thermal transmittance for envelope components specified in the Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Residential Buildings in Severe Cold and Cold Regions (JGJ26-2018) [48].

3.7. Multivariate Statistical Analysis

To investigate the relationship between dwelling performance and morphology, the simulation results were subjected to sensitivity analysis, correlation analysis, and regression analysis. Morphological indicators were comprehensively screened to determine the influence weights and prioritization of each morphological parameter under multiple performance objectives.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Optimization Results Analysis

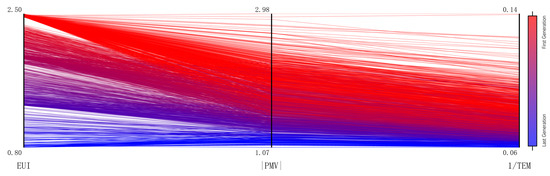

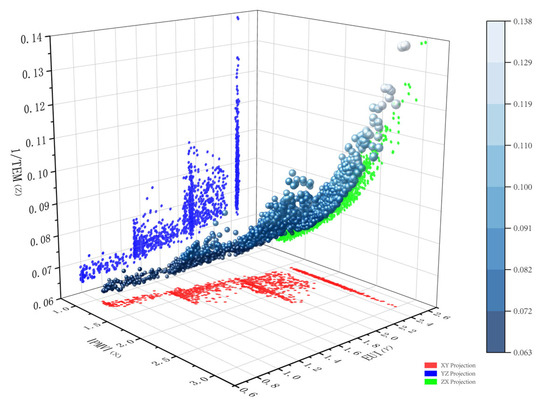

A total of 2500 iterations were performed in this study, generating 2500 solution sets, which formed the basis for subsequent data analysis. As illustrated in the parallel coordinate and scatter plots (Figure 7 and Figure 8), the optimization trends of TEM and PMV are consistent. EUI initially exhibits higher values, which can be attributed to the trade-off between energy consumption and the other two objectives; achieving higher indoor temperatures and improved thermal comfort inevitably requires greater energy expenditure. Through iterative optimization, the population gradually stabilized, ultimately yielding 15 convergent Pareto-optimal solutions [49]. Overall, the Pareto solutions prioritize maintaining adequate indoor temperature and thermal comfort (PMV), while moderately considering winter energy consumption, aligning with the climatic requirements of the region.

Figure 7.

Multi-objective optimization parallel coordinate plot.

Figure 8.

Scatterplot of multi-objective optimization.

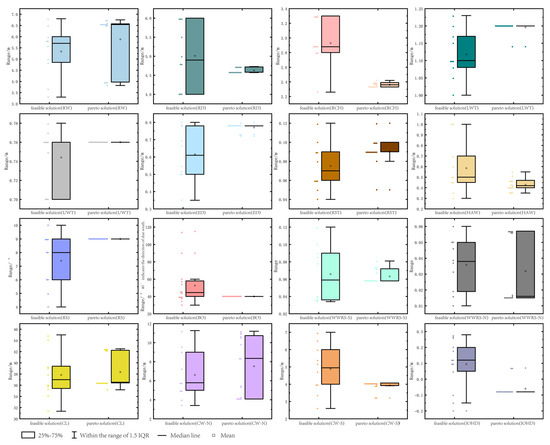

The optimization was conducted based on overall performance, and the morphological parameter values contained in the Pareto front solutions were compiled into recommended ranges, with their optimization trends interpreted to establish suitable value intervals. The performance of Pareto-optimal solutions generally surpasses that of feasible solutions (i.e., the unoptimized, in situ dwelling parameters).

Building orientation fully converged, with south-facing orientation most effective for capturing solar radiation in winter, thereby maximizing indoor mean temperature.

Wall thickness shows a trend toward larger values. The lower wall thickness ranges from 1.14 m to 1.22 m, while the upper wall thickness fully converges around 0.76 m. Roof soil thickness tends toward moderate-to-large values, concentrated near 0.09 m. The high thermal inertia of rammed-earth materials, combined with thicker envelope structures, increases thermal resistance, reduces heat loss, and enhances the thermal performance of walls and roofs. This represents the most direct and effective strategy for improving insulation and maintaining indoor temperature, while also significantly reducing energy consumption.

Window-to-wall ratios (WWR) for south-facing facades tend toward moderate-to-large values, ranging from 0.058 to 0.081, to maximize solar gain in winter while minimizing heat loss through glazing. North-facing WWRs tend toward smaller values, concentrated at 0.015–0.017, to reduce heat loss and enhance insulation.

North-facing courtyard widths have a relatively wide recommended range (4.08–11.15 m), whereas south-facing courtyard widths tend to smaller values (3.2–4.07 m) to create effective windbreaks and reduce cold air infiltration. Courtyard lengths range from 36.34 to 42.51 m, with both Pareto and feasible solutions spanning a wide range.

Height Against Wall is recommended at moderate-to-small values (0.35–0.55 m) to effectively leverage the thermal mass of the ground or mountains. Indoor–outdoor height differences are recommended in a moderate range (−0.08 m to 0.07 m) to slightly improve the microclimate.

Room dimensions show that clear heights are concentrated at 2.33–2.42 m and room depths at 4.57–4.73 m, both tending toward smaller values, which helps reduce energy consumption. Room widths range more broadly (3.97–6.75 m) but tend toward larger values.

Eave depth is recommended at 0.72–0.80 m, showing a trend toward larger values. The roof slope is concentrated at 9°, facilitating solar radiation capture and increasing the width of the roof air layer. (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Optimization results of morphology index.

4.2. Validation of Optimization Results

To validate the effectiveness of the optimization, a relatively balanced optimal solution (No. 49, 8) was compared with the as-built measurements of the dwelling as the baseline. The results indicate that EUI decreased from 2.48 kWh/m2 to 0.797 kWh/m2, PMV improved from −3.77 to −1.12, and the indoor mean temperature (TEM) increased substantially from 11.45 °C to 17.03 °C.

These results demonstrate that the optimized morphological parameters significantly enhance all performance metrics, effectively addressing the primary energy consumption and thermal comfort issues of the local dwellings.

4.3. Data Analysis

4.3.1. Sensitivity Analysis

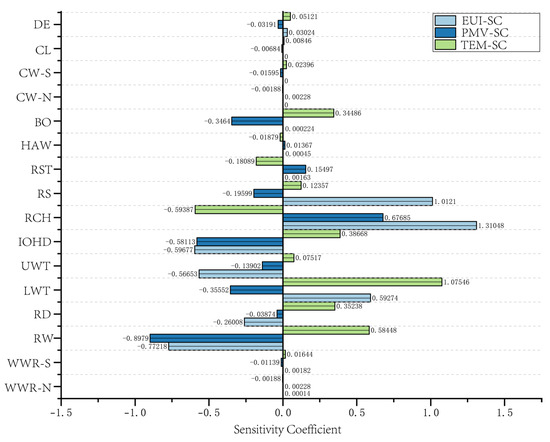

To explore the sensitivity of dwelling morphological parameters to performance objectives, sensitivity coefficients [50] and a parametric simulation platform were used to evaluate the influence of each morphological parameter on the performance targets [51], as expressed in Equation (1):

where is the sensitivity coefficient, is the mean value of the independent variable, and is the mean value of the dependent variable, which includes EUI, PMV, and TEM, simulated for the period of 21–27 January. denotes the variation in the independent variable. In this study, a ±10% variation was applied to all parameters for sensitivity analysis. The resulting change in the dependent variable, , was calculated using the central difference method (Equation (2)). The calculated sensitivity coefficients of each morphological parameter with respect to the performance objectives are shown in Figure 10, and the ranking of sensitivity coefficients is summarized in Table 4.

Figure 10.

Sensitivity analysis of morphological indicators.

Table 4.

Sensitivity Coefficient Rankings of Morphological Parameters for Performance Objectives.

In the energy consumption sensitivity analysis, room clear height and roof slope were identified as the parameters with the greatest impact on EUI, while courtyard width and courtyard length had the least effect. In the PMV sensitivity analysis, room width and room clear height had the largest influence on thermal comfort, whereas courtyard width and the north-facing window-to-wall ratio had the smallest impact. For the indoor mean temperature (TEM) sensitivity analysis, the lower wall thickness and room clear height were the most influential parameters, while courtyard width and the north-facing window-to-wall ratio had minimal effect on indoor temperature.

Considering the overall ranking across all performance objectives, the top three influential parameters were: room clear height, room width, and lower wall thickness. The four least influential parameters were: north-facing courtyard width, north-facing window-to-wall ratio, courtyard length, and south-facing courtyard width.

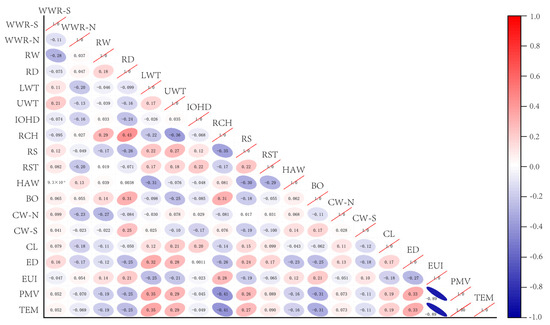

4.3.2. Correlation Analysis

The Pearson correlation analysis results (Figure 11) indicate that thermal comfort (PMV) and indoor mean temperature (TEM) are strongly correlated with room clear height, building orientation, upper and lower wall thickness, and eave depth, confirming that controlling room height and wall thickness has a significant impact on the indoor thermal environment. Energy consumption (EUI) shows strong correlations with room clear height, eave depth, room depth, wall thickness, and building orientation. In contrast, the north- and south-facing window-to-wall ratios exhibit weak correlations with EUI, PMV, and TEM, likely due to the relatively small window sizes and limited parameter ranges, which reduce their influence on the three performance objectives. These findings suggest the presence of complex nonlinear relationships between morphological parameters and performance metrics.

Figure 11.

Heat map of correlation.

The average correlation of each morphological parameter was analyzed according to Equation (3):

where represents the Pearson correlation coefficient, and , and are the absolute values of the correlation coefficients for energy consumption, thermal comfort, and indoor mean temperature, respectively. The composite correlation ranking of the morphological parameters is as follows:

Room clear height, wall thickness, eave depth > building orientation, roof slope, room depth > room width, wall-adjoined height, courtyard length > courtyard width, window-to-wall ratio, indoor–outdoor height difference.

4.3.3. Regression Analysis

Based on the results of the correlation and sensitivity analyses, three morphological parameters with low relevance and low sensitivity—north- and south-facing courtyard widths and courtyard length—were excluded. Subsequently, a partial least squares regression (PLS) analysis [42] was conducted.

The influence weights and prioritization of the remaining morphological parameters are summarized as follows (Table 5): Room clear height, wall thickness > eave depth, building orientation > room depth, room width, roof slope > wall-adjoined height, window-to-wall ratio, roof soil thickness, indoor–outdoor height difference.

Table 5.

Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression Results for Morphological Parameters.

Based on the integrated assessment of sensitivity, correlation, and regression analyses, the following guidelines are proposed for the renovation and design of traditional Suhema House dwellings. First, priority should be given to controlling room dimensions (including room width, depth and room clear height), wall thickness (including upper and lower wall thickness), and building orientation. Second, roof slope and eave depth should be considered as secondary design priorities. Finally, adjustments to window-to-wall ratio, roof soil thickness, indoor–outdoor height difference, and wall-adjoined height can be implemented as supplementary optimization measures.

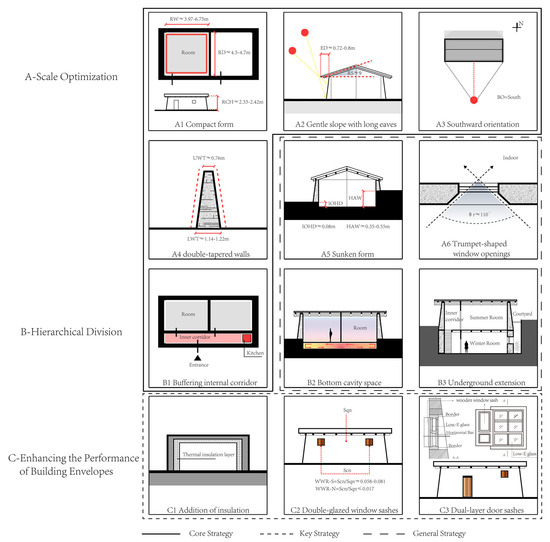

5. Climate-Adaptive Morphological Optimization Strategies for Suoqema Fang Dwellings

Based on the preceding analyses, morphological optimization strategies for Suoqema Fang dwellings are proposed from three perspectives: scale optimization, hierarchical division, and envelope performance enhancement. The importance of each strategy is prioritized according to the comprehensive ranking of morphological parameters (Figure 12), making dwelling morphology a precursor for multidimensional performance improvement [52].

Figure 12.

Schematic Diagram of Morphological Optimization Strategies for Traditional Residential Structures: Suohema House.

5.1. Scale Optimization

Under the premise of maintaining traditional material selection, construction methods, and technical principles, the proportional dimensions of the dwellings are optimized. Low floor heights and short room depths in small-volume units are preferred. Room clear height should be controlled between 2.33 and 2.42 m, and room depth between 4.57 and 4.73 m, as small-volume forms help reduce energy consumption and maintain stable indoor temperatures.

For wall thickness, the original single-sided tapering is modified to a double-sided taper, effectively increasing envelope thickness. The thickness at the upper end of the wall is approximately 0.76 m, while the thickness at the lower end is between 1.14 and 1.22 m. This configuration enhances thermal stability within the interior and improves the overall structural integrity of the dwelling.

For the indoor–outdoor height difference, lowering the indoor floor by approximately 0.08 m and adjusting the outdoor ground slope helps maintain wall-adjoined height between 0.35 and 0.55 m, which reduces winter heat loss.

For the window-to-wall ratio (WWR), the south-facing WWR should be 0.058–0.081, and the north-facing WWR should be no greater than 0.017. Additionally, chamfering the sides of small window openings into a flared shape can improve indoor daylighting without altering window size.

For building orientation, the main façade should face due south to maximize solar gain.

For the roof, slope should be controlled at 9°, with appropriate soil coverage to increase roof mass, enhancing insulation and wind resistance. Eave depth should be maintained between 0.72 and 0.80 m.

5.2. Hierarchical Division

The dwelling space can be divided into multiple levels, creating a climate gradient effect that improves insulation and accommodates functional needs, bridging traditional spatial patterns with modern requirements. Multi-level buffer spaces also facilitate staged temperature and energy control.

On one hand, additional walls can be constructed at the dwelling entrance to form a vestibule or interior corridor, serving as an indoor–outdoor buffer. This not only facilitates circulation between rooms but also extends the thermal path, enhancing insulation and reducing winter heat loss. A three-tiered buffer is thus established, comprising the courtyard, interior corridor, and indoor spaces. On the other hand, creating cavity spaces at the building base allows for spatial transfer and regulation of heat within rooms. Moreover, without altering the overall traditional appearance, expanding the underground space can leverage the natural thermal mass to improve insulation while accommodating dynamic changes in family structure.

5.3. Enhancing the Performance of Building Envelopes

Performance can be improved by replacing or upgrading underperforming or less durable materials or adding movable or replaceable components. For example, an additional internal insulation layer can be added to the existing wall structure to improve thermal performance. Similarly, installing operable wooden window or door panels, or insulating curtains that are opened during the day and closed at night, can reduce nocturnal heat loss. Optimizing the envelope is cost-effective and minimally impacts the traditional architectural appearance, making it particularly significant for the preservation of traditional dwelling aesthetics.

6. Discussion

This study explored the influence of traditional dwelling morphological elements on energy consumption and thermal environment, providing a basis for optimizing morphological design. In practice, Suhema House dwellings do not exist as isolated elements; rather, their components interact in mutually reinforcing or constraining ways. On one hand, features such as heavy envelopes, small window openings, sunken floors, and tapering walls combine multiple performance effects, creating forms that simultaneously satisfy insulation and heat retention requirements. This finding is similar to the conclusion of Gou Weiqin [53]. On the other hand, the diverse demands imposed by the harsh climate often generate conflicting requirements for spatial configuration and physical interfaces. For example, small window openings enhance insulation but reduce natural lighting, while compact forms minimize heat loss but constrain ventilation efficiency. This issue was also addressed in He Wenfang’s research [54], though most studies focus on mitigating it through technical means such as adjustable shading and mechanical ventilation. This study found that in facing such trade-offs, local residents do not rely solely on technological regulation. Instead, after identifying primary comfort needs, they achieve a dynamic balance through habitual preferences (e.g., adjusting clothing) and behavioral strategies (e.g., relocating within the dwelling according to time of day) [55,56], thereby maintaining physiological, psychological, and behavioral adaptation within the environmental energy exchange (Table 6). Clearly, in this case, the priority of insulation is higher than that of lighting and ventilation. This is different from Zhong Wenzhong’s [57] research that focused on ventilation. This is precisely the result of the performance trade-offs and choices made by Suheima House dwellers when facing limited technology and the characteristics of cold climates.

Table 6.

Moving according to the seasons.

Furthermore, optimizing traditional dwelling morphology is not merely a matter of “restoration as original” or “reconstruction from scratch.” Rather, it involves updating, correcting, and modernizing the original forms while preserving their ecological core, inheriting and advancing traditional construction wisdom and climate-adaptive experience. This approach resonates with the concept of “Genuine Constructing” advocated by Zhang Pengju [58]. Furthermore, through quantitative simulation within a multi-objective optimization framework, this study transforms the traditionally vague descriptions of “regionality” and qualitative experiences of climate adaptation in vernacular dwellings into quantifiable, assessable, and optimizable sets of morphological parameters. This constitutes a supplement and deepening of the research conducted by Liu Jintao [59]. At the same time, by carefully introducing appropriate modern technologies and green design methods, the building performance is enhanced and the living needs are met, enabling the dwellings to be rooted in the regional climate environment during the historical construction process. Thus, a balance is achieved among energy efficiency, comfort, cultural identity, and enhancing cultural confidence and recognition is achieved, ultimately constructing a future oasis human settlement paradigm that “allows one to see history, retains nostalgia, enjoys comfort, and keeps up with the times”.

7. Conclusions and Implications

This study, based on field research, extracted the morphological characteristics and key design parameters of traditional Suhema House dwellings in southern Xinjiang. Using genetic algorithms, the study analyzed the optimal parameter ranges for dwelling morphology under multiple objectives, clarified the impact weights and prioritization of each morphological parameter, and provided decision-making guidance for residential design in the region. On this basis, climate-adaptive optimization strategies for residential morphology were proposed, promoting the inheritance of cultural heritage and the continuity of collective memory. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Climate Adaptation Focus: Based on local climate characteristics, the climate adaptation of Suhema House dwellings should focus on the core needs of “withstanding harsh climate environments” and “meeting basic comfort requirements.” The primary strategy is winter insulation and cold resistance, with an emphasis on reducing heat loss and increasing heat gain during construction.

- (2)

- Morphological Recommendations: The recommended morphological form for Suhema House dwellings is a low-rise, compact form with short depth and thick walls. Morphological parameters are classified into three levels of priority. The primary focus should be on controlling room depth (4.57–4.73 m), room width (3.97–6.75 m), room clear height (2.33–2.42 m), wall thickness (lower wall thickness set at 1.14–1.22 m, upper wall thickness at 0.76 m), and building orientation (true south direction). Secondary attention should be given to roof slope (9°) and eave depth (0.72–0.8 m). Finally, factors such as window-wall ratio (WWR South controlled at 0.058–0.081, WWR North ≤ 0.017), indoor–outdoor height difference (−0.08–0.07 m), and indoor-to-outdoor height differences (0.35–0.55 m) should also be considered.

- (3)

- Optimization Strategy: Based on multi-objective optimization results, an optimization strategy for Suoqema Fang dwellings is proposed, which includes:

Scale Optimization: Compact form, gentle roof slope, long eaves, southward orientation, double-tapered walls, sunken form, and trumpet-shaped window openings.

Layered Space Division: Incorporation of a buffering internal corridor, a lower cavity space, and potential underground extension.

Building Envelope Efficiency: Addition of insulation, double-glazed window sashes, and dual-layer door sashes.

However, there are several limitations in this study.

Firstly, the main conclusion of this study is limited to the scenario of extremely cold weather in winter. Further exploration is needed to understand the adaptability to other climate environments such as dry heat and strong solar radiation in summer. For instance, the demand for shading and ventilation in summer environments may require adjustments to the morphological parameters. This is also the direction that needs to be further studied in the next step. Subsequent work will expand the simulated boundary conditions to develop a more comprehensive climate-adaptive design guide.

Secondly, the simulation period was relatively long. In actual practice, due to the fast pace of the early design phase and the frequent changes in design requirements, the multi-objective optimization framework may pose challenges in terms of feedback efficiency for practical application. A highly promising solution is to train machine learning agent models based on the precise simulation data generated in this study to improve feedback efficiency, which will greatly facilitate the application of this framework in practice. This will be the focus of the team’s next work.

Moreover, this study conducted on-site investigations of 33 dwellings and mapped 10 of them. Although the limited sample size may affect the generalizability of conclusions, the selected samples are representative and sufficiently support the proposed methodology and core strategies. The core contribution of this study lies in its research approach, technical route, and generated optimization strategies, which provide design guidance and a replicable research paradigm for the construction of the green oasis rural human environment in other similar arid regions in the northwest.

Author Contributions

Y.T., study principal executor and thesis author; Y.H. conceived and designed the study; X.Z. (Xiaodong Zhang) draws drawings and analyzes data; X.Z. (Xiaoyu Zhang), research and data collection. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (no.: 23BSH066). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of those organizations.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality requirements pertaining to border areas.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- OECD. Transition to Sustainable Buildings: Strategies and Opportunities to 2050; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development: Paris, France, 2013; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/energy/transition-to-sustainable-buildings_9789264202955-en (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Zhang, H.; Li, S. Carbon emissions’ spatial-temporal heterogeneity and identification from rural energy consumption in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 304, 114286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, L.; Qiu, Y.; Ma, Z. Design of the passive solar house in qinba mountain area based on sustainable building technology in winter. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1763–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.-T.; Tran, Q.-B.; Tran, D.-Q.; Reiter, S. An investigation on climate responsive design strategies of vernacular housing in Vietnam. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 2088–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valinejadshoubi, M.; Heidari, S.; Zamani, P. The impact of temperature difference of the sunny and shady yards on the natural ventilation of the vernacular buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 26, 100880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Building Climatology; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010; Volume 4, Available online: https://xueshu.baidu.com/ndscholar/browse/detail?paperid=a82e95a2abd612fb4616df5682b8d3a7&site=xueshu_se (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Oh, J.; Hong, T.; Kim, H.; An, J.; Jeong, K.; Koo, C. Advanced Strategies for Net-Zero Energy Building: Focused on the Early Phase and Usage Phase of a Building’s Life, Cycle. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, E.; Nasrollahi, N.; Khodakarami, J. A comprehensive study of how urban morphological parameters impact the solar potential, energy consumption and daylight autonomy in canyons and buildings. Energy Build. 2024, 305, 113904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. The Formation and Development of Vernacular Architecture Studies. South Archit. 2011, 6, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Z.; Gao, B.; Chen, J. Collective Design Drawings of Green Building in the Northwest of China Desert Regions; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2021; Available online: https://xueshu.baidu.com/ndscholar/browse/detail?paperid=1u2a0ve00v650ge0me240jq0fj164716&site=xueshu_se (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Yang, Z.; Du, C.; Xiong, K. Collective Design Drawings of Green Building in the Southwest of China Multi-Rithnic Regions; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2021; Available online: https://xueshu.baidu.com/ndscholar/browse/detail?paperid=113k08m0xx1u0j40687702g0dd055399 (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Liu, J. The Practice of Green Building in Western China; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015; Available online: https://xueshu.baidu.com/ndscholar/browse/detail?paperid=ce0c58e2e75b15d488871329c1131c46&site=xueshu_se (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X. Breaking the Ground and Rebirth: Study on the Renewal Mode of Native Houses in the Oasis Area of Southern Xinjiang. Dev. Small Cities Towns 2021, 39, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, Z. Research on Green Building Construction Strategy and Technical Path Based on Climate and Geomorphologic Characteristic in the South of the Yangtze River. Archit. J. 2022, S1, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Q. Extraction, identification and translation of the green construction Experience of traditional residential buildings. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 56, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuluxun, N.-R.-M.-M.-T.; Halike, S.-E.-J. Energy Conservation and Low Carbon Strategies for Oasis Residential Buildings in the Arid Area of Eastern Xinjiang Based on Climate Adaptability: Taking Bostan Village in Hami City as an Example. Build. Energy Effic. 2025, 53, 9–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yuan, W.; Liu, Y.; Hao, T.; Liu, J. An Archetype Study on Climate Adaptation of Traditional Vernacular Dwellings in the Temperate Region. New Archit. 2022, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hao, T.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, W.; Liu, J. Dry and Hot Climate Adaption Prototype of Traditional Dwellings. Build. Energy Effic. 2021, 49, 105–115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Q.; Cheng, H.; Li, X. Performance-Oriented Extraction of Residential Forms in Lhasa. World Archit. 2024, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrejon-Esparza, N.M.; González-Trevizo, M.E.; Martínez-Torres, K.E.; Santamouris, M. Optimizing urban morphology: Evolutionary design and multi-objective optimization of thermal comfort and energy performance-based city forms for microclimate adaptation. Energy Build. 2025, 342, 115750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Li, X. A Performance-Oriented Study on the Archetype of Traditional Dwellings in Hehuang Area in Qinghai Province. Build. Energy Eff. 2024, 52, 58–66+130. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, J. Multi-Criteria Performance Interconnection Optimisation Deduction of Atrium Prototype Space Under the Influence of Environmental Factors. World Archit. 2021, 112–117+126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Run, L.; Luo, L.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Jiang, F.; Wang, W. Multi-objective optimization for generative morphological design using energy and comfort models with a practical design of new rural community in China. Energy Build. 2024, 313, 114282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Ma, X. Microclimate-Adaptive Morphological Parametric Design of Streets and Alleys in Traditional Villages. Buildings 2024, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liang, F.; Hong, T.; Lin, Z. Climate-Adaptive Construction Strategies for Coastal Rural Street Spaces Based on Genetic Algorithm: A Case Study of the Coastal Plain Area of Fuzhou. World Archit. 2025, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, S. Research on spatial form optimization of traditional blocks based on genetic algorithm: A case of the old city of Kashgar. City Plan. Rev. 2023, 47, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Valiyappurakkal, V.K.; Shabarise, Y.; Natawadkar, K.; Misra, K. A methodology to assess the constructibility of free-form buildings using building and surface performance indicators: Application to a case study. Energy Build. 2022, 270, 112303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, S.; Lei, Z. Research on the Dimensions Optimisation of Sunshade Components for Lhasa Dwellings from the Perspective of Photothermal Coupling. World Archit. 2024, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Zheng, W.; Li, X.; Yang, W.; Wang, R. Multi-objective optimization design for rural houses in western zones of China. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2022, 65, 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Xiao, Y.; Yin, H. A Review of the Climate Responsive Characteristics Research on Thermal Environment Correlation of Domestic Traditional Dwellings. Dev. Small Cities Towns 2023, 41, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Yang, L. Climatic Adaptation Analysis of Vernacular Houses of Lhasa by Climate Consultant. Build. Sci. 2017, 33, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.Z.; Zhang, T. Four quadrants of the discourse on architectural environmental regulation. New Archit. 2024, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olgyay, V. Design with Climate: Bioclimatic Approach to Architectural Regionalism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1963; Volume 161. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.; Zhang, T. Performance Mechanism of Building Formation and Key Strategies of Adaptive Formation Design. Architect 2019, 6, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, W.; Zhang, T. Environmental Regulation Five: Paradigm Shift of Le Corbusier’s Theory and Practice in a View of Climatic Logic. Architect 2019, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P. The Gene Expression and the Sight Identification of the Ancient Villages ’Cultural Landscape. J. Hengyang Norm. Univ. 2003, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y. Recognition of theoretical foundation of “Regional Gene” conceptin regional building construction system. Huazhong Archit. 2012, 30, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.; Li, S. Research on gene identification and mapping of traditional dwellings in mountainous areas of Southern Hebei. World Archit. 2023, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Yoshino, Y.; Liu, Y. The thermal mechanism of warm in winter and cool in summer in China traditional vernacular dwellings. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 1709–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems: An Introductory Analysis with Applications to Biology, Control, and Artificial Intelligence, Adapt; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Y.; Raslan, R.; Mumovic, D. Implementing multi objective genetic algorithm for life cycle carbon footprint and life cycle cost minimisation: A building refurbishment case study. Energy 2016, 97, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cui, Y.; Zheng, H.; Ning, Q. Optimization and prediction of energy consumption, light and thermal comfort in teaching building atriums using NSGA-II and machine learning. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, W.; Ming, M.A. NSGA-II algorithm based multi -objective optimization design for rural residential buildings along the Yellow River, Inner Mongolia section. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2023, 37, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Huang, Q. Multi-objective Optimization Design Method of Building Performance and Its Application: The Issue of Genetic Algorithm. New Archit. 2021, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexakis, K.; Benekis, V.; Kokkinakos, P.; Askounis, D. Genetic algorithm-based multi-objective optimisation for energy-efficient building retrofitting: A systematic review. Energy Build. 2025, 328, 115216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Fang, Y.; Yang, W.; Lu, Z.; Wang, X. Multi-objective optimal research on low-energy dwellings design based on genetic algorithm in Qinba mountain region, China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Soolyeon, C. Design Optimization of Building Geometry and Fenestration for Day lighting and Energy Performance. Solar Energy 2019, 191, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Residential Buildings in Severe Cold and Zones; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2018; Available online: https://xueshu.baidu.com/ndscholar/browse/detail?paperid=36114ca1ca2e4da5d79791d73c9cd62c&site=xueshu_se (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Deb, K. Muti-Objective Optimization Using Evolutionary Algorithms; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2001; Available online: https://xueshu.baidu.com/ndscholar/browse/detail?paperid=ea2b2550e96e3a4870870e4cdb638bb3&site=xueshu_se (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Lam, J.C.; Hui, S.C.M. Sensitivity Analysis of Energy Performance of office Buildings. Build. Environ. 1996, 31, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, A.; Wright, J. Solution Analysis in Multi-objective Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2012 Building Simulation and Optimization Conference, Loughborough, UK, 10–11 September 2012; pp. 317–324. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Xiao, W.; Pan, Y.; Lei, Z. Space structure optimization and energy efficiency improvement in low-carbon architectural renovation I: Prototypes and mechanisms. J. Southeast Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gou, W.; Saierjiang, H.; Shang, J.; Yang, M.; Zhang, T. Multi-Objective Optimization Design of Traditional Soil Dwelling Renovation Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process—Quality Function Deployment—Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II: Case Study in Tuyugou Village in Turpan, Xinjiang. Buildings 2024, 14, 3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zheng, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, J. Study on climate adaptation of vernacular building in extreme arid climate based on archetype. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 54, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, X. Research on the spatial morphological characteristics of traditional villages in the Tarim Basin. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2025, 39, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Saierjiang, H. Living in a comfortable space: Research on the residential periodic transfer pattern of oasis folk houses in Southern Xinjiang. South Archit. 2020, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Pan, Y.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, T. Identifying bioclimatic techniques for sustainable low-rise high-density residential units: Comparative analysis on the ventilation performance of vernacular dwellings in China. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 108008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P. “Genuine Constructing”: A framework of ideology, methodology, and technology for regional architecture in Western China. Contemp. Archit. 2025, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Saierjiang, H. Analysis on climate adaptability of dwellings in Arid Oasis Area by climate consultant—A case of kashi in xinjiang uygur autonomous region. Urban. Archit. 2021, 18, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).