Abstract

The stress–strain relationship of steel bars is fundamental for the fire safety assessment of reinforced concrete structures. This study investigated the mechanical properties of hot-rolled ribbed steel bars at elevated temperatures through tensile tests. The results show that the elastic modulus, yield strength, and ultimate strength decrease with increasing temperature, with a significant decline especially at 300–700 °C, and the yield plateau shortens or even disappears. The ultimate strain initially decreases and then increases when the temperature exceeds 400 °C. Relevant experimental data were collected and analyzed to discuss the temperature dependence of these properties. A simplified trilinear/bilinear constitutive model that accounts for the disappearing yield plateau with a defined critical temperature of 300 °C is proposed. The fracture mechanism was investigated through fractographic analysis. The experimental results were used to validate both the proposed model and the EC2 model, demonstrating that the former achieves higher accuracy for the steel bars studied.

1. Introduction

The mechanical properties of steel bars are critical to concrete structures, yet they deteriorate during and after a fire, potentially causing severe damage or collapse. Consequently, the stress–strain relationship of steel at elevated temperatures is a key factor for predicting structural behavior under fire and for conducting post-fire safety assessments [1]. This change is attributed to the increased interatomic distance and weakened atomic bonds at high temperatures, which fundamentally alter the shape and characteristic parameters of the stress–strain curve [2].

Extensive experimentation has characterized the degradation of steel bar’s mechanical properties at high temperatures [3,4,5]. The steady-state test is the most common method, in which a specimen is heated to a target temperature at a predetermined rate and then subjected to a tensile load until failure, with simultaneous recording of load and deformation [6]. These tests consistently show that as temperature rises, the elastic modulus, yield strength, and ultimate strength of steel gradually decrease, the yield plateau shortens or vanishes, and deformation capacity changes significantly [7].

Based on experimental evidence, researchers have established various constitutive models to characterize the stress–strain behavior of steel bars under thermal exposure, including bilinear [8], multilinear [9], and linear-plus-curve formulations [10]. The bilinear model proposed by Lie [8] has gained widespread adoption in North America due to its computational simplicity, while the linear-plus-curve model specified in EC2 [10] remains predominant in European practices. Although the EC2 model incorporates strain-hardening effects below 400 °C, its implementation requires 26 equations with 42 independently determined parameters, making it substantially more complex than Lie’s two-stage representation.

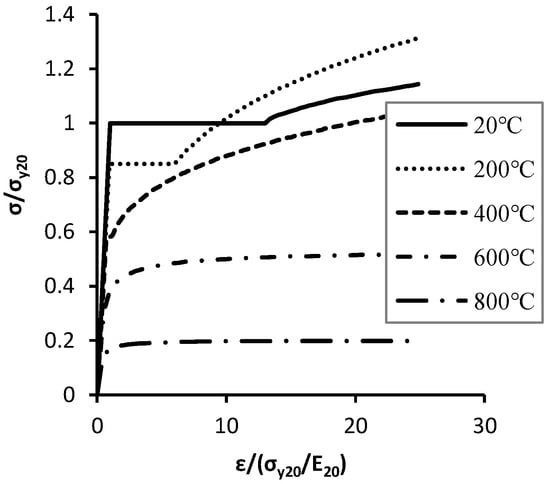

Notably, these established models fail to adequately address temperature-dependent variations in yield plateau characteristics and ultimate strain. To bridge this gap, Poh [11] developed an advanced constitutive model integrating three distinct phases: linear elasticity, yield plateau, and nonlinear strain hardening (Figure 1). This sophisticated framework employs a unified continuous function coupled with temperature-dependent parameters to establish a comprehensive stress–strain—temperature relationship, demonstrating advantages in numerical simulation applications. However, the model neglects temperature-induced evolution of ultimate strain. In a modified approach, Quiel [4] enhanced the EC2 formulation by substituting ultimate strength for yield strength and introducing temperature-dependent ultimate strain calibrated through experimental validation. Kodur [2] found that high-temperature creep, which is not often included in constitutive models, had a significant influence on the fire response of steel structures.

Figure 1.

Relative stress–strain relationships of steel bars at various temperatures (Poh [11]).

In the performance-based design of concrete structures for fire resistance, employing an accurate constitutive model of steel reinforcement is fundamental for assessing fire safety [12]. However, a comprehensive characterization of the high-temperature stress–strain relationship for widely used Chinese hot-rolled ribbed bars remains lacking in the current literature. While ACI 216 [13] provides strength reduction factors, it does not furnish a complete stress–strain model. EC2 [10] does include a detailed constitutive model, describing the evolution of ultimate strength and ultimate strain with temperature, but its practical application is hindered by a large number of required parameters. To address these limitations, this study conducted static tensile tests on hot-rolled ribbed bars (HRB335 and HRB400E) at various temperatures. Based on the observed characteristics of the measured stress–strain curves, a new constitutive model for steel reinforcement at elevated temperatures is proposed. Furthermore, by integrating experimental data with existing domestic and international research, the temperature-dependent variations in key mechanical properties, including the modulus of elasticity, yield strength, ultimate strength, strain at the onset of strain hardening, ultimate strain, and the characteristics of the yield plateau, were systematically analyzed. Finally, a fracture analysis of the tensile specimens is performed to elucidate the underlying failure mechanisms of steel reinforcement under high-temperature conditions.

2. Tensile Tests of Steel Reinforcement at Elevated Temperatures

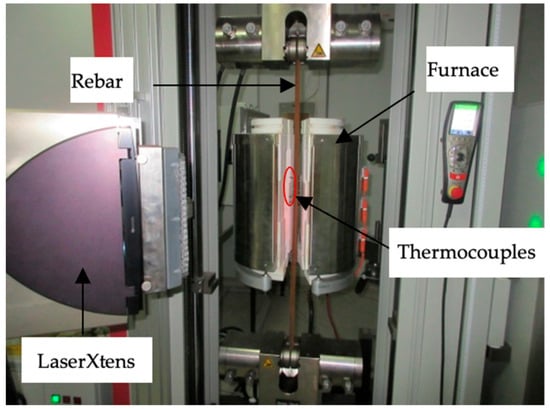

The high-temperature tensile tests on the steel reinforcement were conducted using a Zwick Z100TEW universal testing machine (Ulm, Germany), with a maximum load capacity of 250 kN. The high-temperature furnace used has a temperature range of 200–1100 °C, with a temperature fluctuation of ±2 °C during the testing process. Displacement was measured using a fully automatic, high-precision laser extensometer (laserXtens, Ulm, Germany). The extensometer has a gauge length of 64 mm and a resolution of 0.15 μm. The setup for the high-temperature tensile testing equipment is shown on Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Elevated temperature testing arrangement.

The test specimens were hot-rolled ribbed steel bars, specifically grades HRB335 and HRB400E, which are widely used in China. The measured chemical compositions of the steel bars are presented in Table 1, where the values are given in mass percentage. Each specimen had a length of 1100 mm and a nominal diameter of 16 mm.

Table 1.

Chemical components of steel bars (percentage of element by mass).

The tensile tests were conducted in accordance with ASTM E21-09 [14]. A constant temperature loading regime was employed. The test temperatures included ambient temperature (20 °C), 200 °C, 300 °C, 400 °C, 500 °C, 600 °C, 800 °C, and 1000 °C. During the loading process, a constant strain rate of 0.005/min was maintained until specimen failure. Three samples were tested for each operating condition.

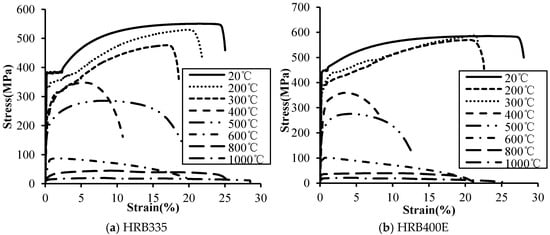

3. Stress–Strain Relationship Curves of Steel Reinforcement at Elevated Temperatures

The stress–strain relationship curves for the steel bar at elevated temperatures are shown in Figure 3. Stress was calculated as the applied load divided by the nominal cross-sectional area, and strain was taken as the elongation divided by the original gauge length. As can be observed from Figure 3, as the temperature increases, the modulus of elasticity, yield strength, and ultimate strength of the steel bar all decrease by varying degrees. The strength decreases significantly beyond 400 °C. The ultimate strain, however, exhibits a trend of first decreasing and then increasing with rising temperature.

Figure 3.

Stress–strain relationships of steel bars at various temperatures.

It can be observed from Figure 3 that the length of the yield plateau is highly sensitive to temperature, showing progressive shortening until its complete disappearance. The plateau is markedly reduced at 300 °C and is entirely absent at 400 °C. This behavior is corroborated by data from independent studies presented in Table 2, which report a critical temperature range consensus of 300–400 °C for this phenomenon. For streamlined application in engineering practice, a conservative and unified threshold of 300 °C is proposed for both HRB335 and HRB400E grades.

Table 2.

Critical temperature at which yield plateau disappeared at elevated temperatures.

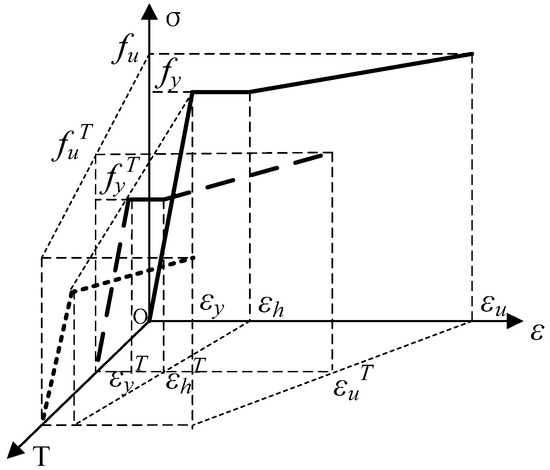

Considering comprehensively the characteristics of mechanical property changes in steel bar under elevated temperatures, a constitutive model, as shown in Figure 4, is proposed. The temperature at which the yield plateau disappears is defined as the critical temperature. When the temperature is below the critical temperature and the yield plateau has not yet fully vanished, a trilinear model is adopted. When the temperature exceeds the critical temperature, the yield plateau disappears, and the stress–strain behavior transitions directly into the strain-hardening stage after the elastic limit is reached; thus, a bilinear model is employed.

Figure 4.

Stress–strain relationship for steel bars at elevated temperatures.

Therefore, once the temperature-dependent variation in the characteristic parameters, namely, the modulus of elasticity, yield strength, ultimate strength, ultimate strain, and the strain at the onset of strain hardening, are fully determined, the complete stress–strain relationship at elevated temperatures can be obtained, as given by Equation (1).

where and represent the stress and strain of the steel bar at elevated temperatures, respectively; , , and represent the modulus of elasticity, yield strength, and ultimate strength of the steel bar at elevated temperatures, respectively; , , and represent the yield strain, the strain at the onset of strain hardening, and the ultimate strain of the steel bar at elevated temperatures, respectively.

4. Characteristic Parameters of Mechanical Properties for Steel Bar at Elevated Temperatures

As temperature increases, both the grain strength and grain boundary strength of steel bar decrease. For commonly used structural steels, when the temperature reaches approximately 727 °C, the microstructure of the steel transforms from pearlite to austenite, and the crystal structure changes from a body-centered cubic lattice to a face-centered cubic lattice. Upon exceeding 1100 °C, the steel becomes essentially fully austenitized, at which point its strength is very low. Consequently, for the statistical analysis of the characteristic mechanical parameters of steel bar at elevated temperatures, the ambient temperature is taken as 20 °C. For temperatures exceeding 1100 °C, the yield and ultimate strengths are zero.

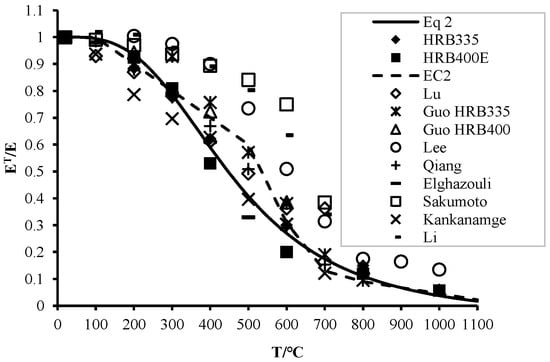

4.1. Modulus of Elasticity

Existing test results indicate that the modulus of elasticity gradually decreases with increasing temperature and is largely independent of the specific type of steel bar. Figure 5 presents the measured modulus of elasticity of steel bar at different temperatures. As can be seen from the figure, the measured results from various researchers [10,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] exhibit considerable scatter, but the overall trend is consistent. At relatively low temperatures (less than 300 °C), the decrease in the modulus of elasticity is relatively slow. As the temperature increases, the modulus decreases rapidly. When the temperature exceeds 700 °C, the modulus of elasticity becomes very small due to steel softening, and the rate of decrease slows down again. The relationship between the relative value of the modulus of elasticity and temperature is given by Equation (2). The proposed model is compared with the experimental results and the EC2 model. Figure 5 shows that between 300 °C and 600 °C, the EC2 model is slightly higher than the model proposed in this paper, while at other temperatures the results of the two models are similar. Overall, the model proposed herein lies at the lower bound of all the experimental data and agrees well with the test results obtained in this study.

where and represent the modulus of elasticity of the steel bar at elevated temperatures and ambient temperature, respectively.

Figure 5.

Relationship between relative elastic modulus and temperature [10,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

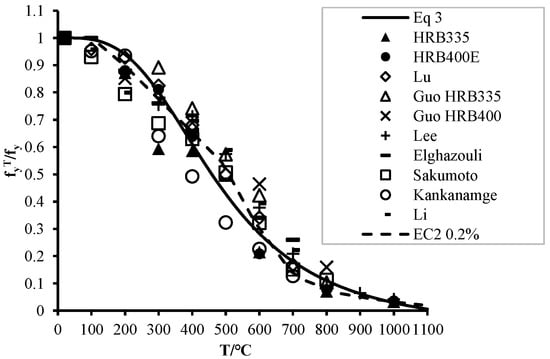

4.2. Yield Strength

Prior to the disappearance of the yield plateau, the elastic limit is taken as the yield strength. After the critical temperature is exceeded and the yield plateau has vanished, the stress at 0.2% strain is adopted as the yield strength. Figure 6 presents the experimental results for the yield strength of steel bar at elevated temperatures. Similarly to the modulus of elasticity at high temperatures, the test results from different researchers [10,15,16,17,19,20,21,22] show considerable scatter, but the overall trend remains consistent. At relatively low temperatures (<300 °C), the decrease in yield strength is slow. As the temperature increases further, the yield strength decreases rapidly. When the temperature exceeds 700 °C, the rate of decrease in yield strength slows down again. Equation (3) gives the relationship between the relative value of the yield strength and temperature for steel bar. As can be seen from Figure 6, the model proposed in this paper shows good agreement with both the EC2 model and the experimental results obtained in this study, and overall, it correlates well with the experimental data.

where and represent the yield strength of the steel bar at elevated temperatures and ambient temperature, respectively.

Figure 6.

Relationship between relative yield strength and temperature [10,15,16,17,19,20,21,22].

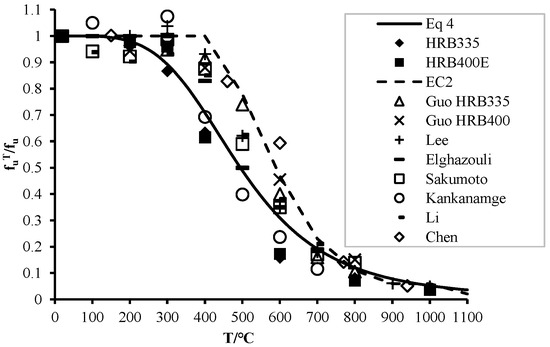

4.3. Ultimate Strength

Figure 7 presents the experimental results for the ultimate strength of steel bar at elevated temperatures [10,16,17,19,20,21,22,23]. As temperature increases, the steel bar undergoes softening, leading to a reduction in its ultimate strength. However, when the temperature is below 300 °C, the decline is minimal. Within the range of 300 °C to 700 °C, the ultimate strength decreases drastically. Beyond 700 °C, the ultimate strength becomes very small, and its rate of decrease diminishes again. Equation (4) gives the relationship between the relative value of the ultimate strength and temperature. As can be observed from the figure, for temperatures below 700 °C, the EC3 model generally lies at the upper bound of the experimental data, which is potentially unconservative, whereas the model proposed in this paper primarily corresponds to the lower bound of the test results.

where and represent the ultimate strength of the steel bar at elevated temperatures and ambient temperature, respectively.

Figure 7.

Relationship of relative ultimate strength and temperature [10,16,17,19,20,21,22,23].

4.4. Strain at the Onset of Strain Hardening

The critical temperature at which the yield plateau disappears for steel bar is taken as 300 °C. Assuming an approximately linear degradation of the yield plateau length with increasing temperature, the strain at the onset of strain hardening at elevated temperatures can be calculated using linear interpolation:

where and represent the yield strain and the strain at the onset of strain hardening of the steel bar at ambient temperature, respectively; and represent the yield strength and modulus of elasticity at elevated temperatures, respectively.

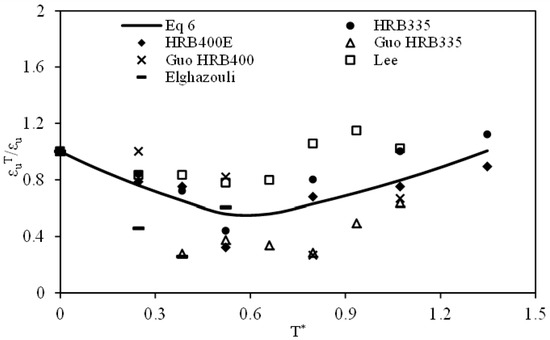

4.5. Ultimate Strain

At elevated temperatures, the lattice structure of steel bar undergoes phase transformation. Around 300 °C, the ductility decreases due to the blue brittleness phenomenon, which is strain aging due to interstitial atoms. However, at higher temperatures, the softening of the steel bar leads to a significant increase in its ductility. Figure 8 presents the experimental results for the ultimate strain of steel bar/steel at different normalized temperatures [16,17,19]. Considerable scatter can be observed in the test data, yet the overall trend is consistent: the ultimate strain first decreases and then increases with rising normalized temperature. Figure 8 indicates that the minimum value of the ultimate strain occurs at approximately 400 °C. The relationship between the relative value of the ultimate strain and the normalized temperature can be approximately described by an exponential function. Equation (6) gives this relationship for the ultimate strain of steel bar at elevated temperatures.

where and represent the ultimate strain of the steel bar at elevated temperatures and ambient temperature, respectively, and the normalized temperature is defined as .

Figure 8.

Relationship of relative ultimate strain of steel and temperature [16,17,19].

5. Fractographic Characteristics and Analysis

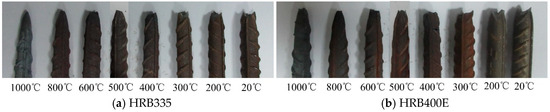

Figure 9 shows the failure modes of the steel bar specimens tested at different temperatures. As shown in the figure, the failure modes are similar for temperatures below 400 °C, characterized by significant local necking and a semi cup-and-cone fracture. When the temperature exceeds 400 °C, the gauge length within the high-temperature zone becomes noticeably and uniformly elongated. Furthermore, the reduction in area gradually increases with rising temperature.

Figure 9.

Failure modes of steel bars at various temperatures.

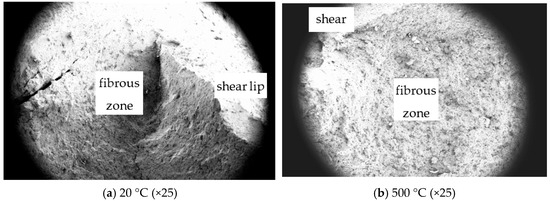

To further investigate the fracture mechanism of steel bar under elevated temperatures, field emission scanning electron microscopy was employed to examine the fracture surfaces obtained from the static tensile tests. Figure 10 shows the macroscopic morphologies of the fracture surfaces for HRB400E steel bars tested at ambient temperature and 500 °C.

Figure 10.

Macroscopic images of tensile fracture of HRB400E at different temperatures.

The observations indicate that the fractures are ductile in nature. The fracture origin is located in the central region of the fracture surface, exhibiting a fibrous appearance. The peripheral shear lip region forms an angle of approximately 45° with the tensile axis. At ambient temperature, noticeable dimples are present at the fracture origin, and distinct micro-cracks are observed on the fracture surface. These features are typically attributed to the combined effects of hydrogen-induced damage and applied stress. In contrast, the fracture origin region at 500 °C appears relatively flat, and the area occupied by the shear lip is reduced. This suggests an enhanced deformation capacity of the steel bar at 500 °C.

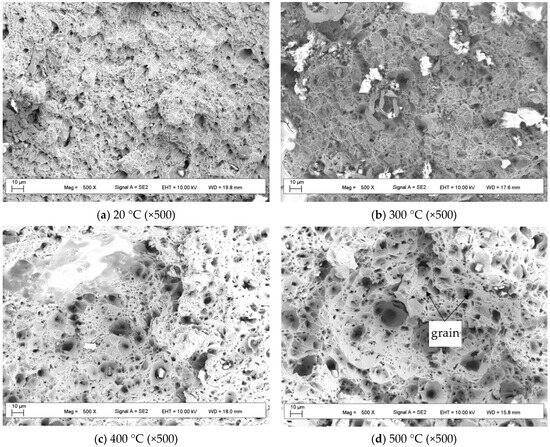

Figure 11 shows the microscopic morphologies of the tensile fracture surfaces for HRB400E steel bars at different temperatures. As can be seen from the figure, the fracture surface at ambient temperature exhibits a large number of dimples, indicative of transgranular ductile fracture. As the temperature gradually increases to 400 °C, the number of dimples on the fracture surface decreases, indicating a gradual reduction in the plastic deformation capacity of the steel bar. Figure 8 also shows that the ultimate strain of steel reinforcement reaches its minimum value near this temperature. This phenomenon occurs because, around 300 °C, the steel experiences blue brittleness, where the pinning effect of carbon and nitrogen atoms leads to an increase in dislocation density, resulting in a decrease in the material’s deformation capacity.

Figure 11.

Microscopic images of tensile fracture of HRB400E at different temperatures.

However, when the temperature rises to 500 °C, the number of dimples on the fracture surface significantly increases, reflecting enhanced plasticity. Concurrently, it can be observed that as the temperature increases, both the diameter and depth of the dimples gradually enlarge. This is attributed to the increased cohesiveness between particles at higher temperatures, requiring microvoids to coalesce and grow to a larger size before fracture occurs, consequently leading to the increase in dimple size and depth. The presence of fine grains observed in Figure 11d is caused by dynamic recrystallization occurring at the fracture surface under a high temperature. Dynamic recrystallization enables grain boundaries to acquire sufficient driving force for migration at elevated temperatures, resulting in the softening of the steel bar.

6. Model Validation

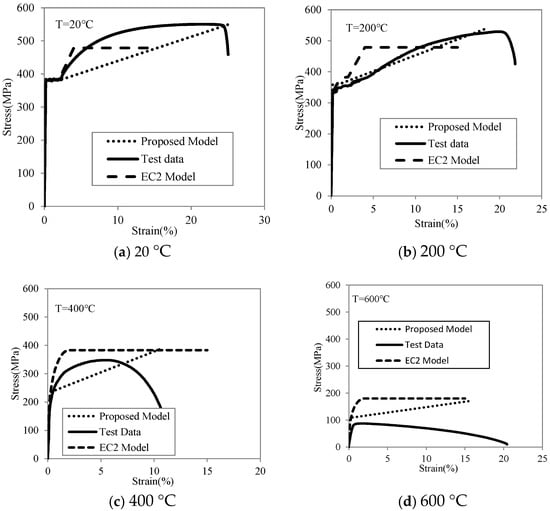

The proposed prediction model is compared with experimental results and the model specified in EC2, as illustrated in Figure 12. When comparing the prediction model with the experimental data, the proposed model shows good agreement with the test results at 200 °C and below. The experimental results for yield strength, ultimate strength, and ultimate strain align well with the predictions of the model, demonstrating strong consistency. This good agreement with experimental data is also maintained at 400 °C.

Figure 12.

Comparison of proposed model with test data and Eurocode 2.

However, at 600 °C and above, the experimental results are noticeably lower than the predicted values from the model, which can be attributed to changes in the physical properties of the steel reinforcement induced by high temperatures. This indicates that the proposed prediction model still has certain limitations at 600 °C.

In comparison with the EC2 model, it can be seen that the EC2 model exhibits slightly better consistency with experimental data at ambient temperature than the proposed model. However, at 200 °C and above, the predictions of the EC2 model are generally higher than both the proposed model and the experimental results. Therefore, the EC2 model should be applied with caution for this type of steel bar.

7. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the high-temperature mechanical behavior and microstructural evolution of steel reinforcement through steady-state tensile tests and fractographic analysis. The principal findings are summarized as follows:

(1) The modulus of elasticity, yield strength, and ultimate strength of steel reinforcement exhibit a temperature-dependent degradation. The reduction is moderate below 300 °C, accelerates significantly in the range of 300–700 °C, and is followed by a pronounced softening stage beyond 700 °C, during which the residual strength remains very low and the rate of strength loss diminishes.

(2) The yield plateau shortens progressively with increasing temperature and disappears completely around 300 °C. The ultimate strain shows a non-monotonic trend with temperature: it initially decreases, reaches a minimum around 400 °C—indicating the poorest deformation capacity—and subsequently increases at higher temperatures.

(3) A simplified yet practical constitutive model is proposed to describe the stress–strain relationship of steel bar under high temperatures, explicitly accounting for the temperature-induced shortening and eventual disappearance of the yield plateau. The model is supplemented by analytical expressions for key parameters, including the modulus of elasticity, yield strength, ultimate strength, strain at the onset of strain hardening, and ultimate strain.

(4) Fractographic evidence confirms that all specimens failed in a ductile manner, with fractures initiating centrally. As temperature rises, the number of dimples initially decreases and then increases, accompanied by a consistent growth in dimple size. This microstructural evolution reflects the initial deterioration and subsequent recovery of material plasticity under elevated temperatures. Recrystallization phenomena observed at higher temperatures contribute to the macroscopic softening behavior of the steel.

(5) From the data comparison in model validation, it can be observed that the proposed model in this paper shows excellent agreement with the test data at 200 °C when compared against both EC2 and experimental results. However, certain limitations of the proposed model are also evident: its accuracy at 20 °C is inferior to that of the EC2 model, and at 600 °C, the model generally overestimates the values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T.; Methodology, H.T.; Validation, J.Z.; Formal analysis, J.Z.; Investigation, H.T. and W.X.; Data curation, W.X.; Writing—review & editing, G.B.; Supervision, G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Hongyong Tang was employed by the company East China Architectural Design & Research Institute Co., Ltd. Author Jia Zhu was employed by the company Shanghai Xiandai Architectural Decoration & Landscape Design Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Leal Matilla, A.; Ferrández, D.; Prieto Barrio, M.I.; Varum, H. Systematic Review on the Behaviour of Carbon and Stainless Steel Reinforcing Bars in Buildings Under High Temperatures. Buildings 2025, 15, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodur, V.; Dwaikat, M.; Fike, R. High-Temperature Properties of Steel for Fire Resistance Modeling of Structures. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2010, 22, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, C. Elevated-temperature mechanical properties of high-strength structural steels over 500 MPa under transient state conditions. Fire Saf. J. 2025, 157, 104505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiel, S.E.; Irwin, C.H.; Naito, C.J.; Vermaak, N. Mechanical Characterization of Normal and High-Strength Steel Bars in Reinforced Concrete Members under Fire. J. Struct. Eng. 2020, 146, 04020110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yan, R.; Xu, L. Effect of Tensile-Strain Rate on Mechanical Properties of High-Strength Q460 Steel at Elevated Temperatures. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 04020188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, F.U.; Cashell, K.A.; Anguilano, L. Experimental Study of the Post-Fire Mechanical and Material Response of Cold-Worked Austenitic Stainless Steel Reinforcing Bar. Materials 2022, 15, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.-Q.; Song, L.-X. Mechanical properties of TMCP Q690 high strength structural steel at elevated temperatures. Fire Saf. J. 2020, 116, 103190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, T.T. Structural Fire Protection; ASCE: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Corradi, L.; Poggi, C.; Setti, P. Interaction domains for steel beam-columns in fire conditions. J. Constr. Steel Res. 1990, 17, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Standards Institution. Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures—Part 1–2: General Rules-Structural Fire Design; British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Poh, K.W. Stress-Strain-Temperature Relationship for Structural Steel. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2001, 13, 371, Erratum in J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2014, 26, 388–389. https://doi.org/10.1061/(Asce)Mt.1943-5533.0000902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMalva, K.J. Structural Fire Engineering; ASCE: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- American Concrete Institute. Code Requirements for Determining Fire Resistance of Concrete and Masonry Construction Assemblies; Joint ACI-TMS Committee 216: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM E21; Standard Test Methods for Elevated Temperature Tension Tests of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Niu, H.; Lu, Z.; Chen, L. An experimental study of the constitutive relation between reinforced bar and concrete under elevated temperature. J. Tongji Univ. 1990, 03, 287–297. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lv, T.; Shi, U.; Guo, Z. Experimental studies on the strength and deformation of I–V reinforcement and concrete at elevated temperatures. J. Fuzhou Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 1996, 24, 11–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Engelhardt, M. Pre-yielding effects of ASTM A992 steel at elevated temperatures. Int. J. Steel Struct. 2014, 14, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, X.H.; Bijlaard, F.S.K.; Kolstein, H. Elevated-temperature mechanical properties of high strength structural steel S460N: Experimental study and recommendations for fire-resistance design. Fire Saf. J. 2013, 55, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghazouli, A.Y.; Cashell, K.A.; Izzuddin, B.A. Experimental evaluation of the mechanical properties of steel reinforcement at elevated temperature. Fire Saf. J. 2009, 44, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakumoto, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Ohashi, M.; Saito, H. High-temperature properties of fire-resistant steel for buildings. J. Struct. Eng. 1992, 118, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankanamge, N.; Mahendran, M. Mechanical properties of cold-formed steels at elevated temperatures. Thin-Walled Struct. 2011, 49, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Jiang, S.; Yin, Y. Experimental studies on the properties of constructional steel at elevated temperatures. J. Struct. Eng. 2003, 129, 1717–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Young, B.; Uy, B. Behavior of high strength structural steel at elevated temperatures. J. Struct. Eng. 2006, 132, 1948–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).