Abstract

Medium-deep borehole heat exchanger (MBDHE) is a clean building heating solution that offers improved indoor thermal comfort, but it risks heat extraction capacity deterioration due to insufficient geothermal heat flux recovery. Cross-seasonal heat storage can mitigate heat extraction capacity deterioration. However, previous studies focused on optimizing the heat storage parameters without considering the mutual inhibition between geothermal heat flux recovery and the heat storage. This paper proposes a soil heat deficit regulation-based cross-seasonal heat storage method, which expands the soil heat deficit to enhance the geothermal heat flux recovery and heat storage simultaneously for improved heating performance of the MDBHE. The effectiveness of the proposed method is demonstrated by using an MDBHE model validated against actual engineering data. The results show that the flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation is more effective than the temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation. Expanding the soil heat deficit by lowering the heat extraction temperature effectively increases the heat extraction capacity of MDBHE by up to 44.82% with a relatively stable heat storage efficiency. Expanding the soil heat deficit by increasing the heat extraction flow rate increases the heat extraction capacity by up to 55.93% and improves the heat storage efficiency by up to 18.71%. Furthermore, the robustness of the soil heat deficit regulation is verified under different heat storage conditions. Therefore, the proposed method can effectively improve the heating performance of MDBHE, enhancing indoor thermal comfort and contributing to the advancement of low-carbon building heating.

1. Introduction

To achieve carbon neutrality and meet the growing global energy demand, transitioning to sustainable, renewable energy heating solutions is crucial for both environmental sustainability and energy security [1]. Geothermal resources, known for their wide distribution, low carbon emissions, reliability, and ability to enhance indoor thermal comfort, have become a primary source of clean heating in northern China [2]. Medium-deep borehole heat exchanger (MDBHE) technology offers advantages such as higher outlet temperatures, minimal land use, and reduced surface disturbance [3], making it particularly suitable for large-scale deployment in urban areas with limited land resources. In recent years, the application of MDBHE has rapidly expanded. Since 2013, the integration of MDBHE with heat pump systems has gradually been adopted in northern China, currently serving over 30 million square meters of building area [4].

Extensive research, including field experiments, analytical calculations, and numerical simulation studies, has been conducted to investigate the heating performance of the DBHE system. Wang et al. [5] monitored an MDBHE system for an office building in Harbin, with an average heat exchange rate of 152.6 W/m and a heat pump coefficient of performance (COP) ranging from 4.46 to 6.89. Deng et al. [6] monitored an MDBHE with a depth of 2750 m, reporting an average heat extraction rate of 429.5 kW and a system COP of 3.68. To accurately model the long-term and short-term heat transfer processes of MDBHEs, Luo et al. [7,8,9] developed a series of analytical models, such as the non-uniform finite line source method [7] and the Response Factor Matrix method [10].

Continuous heat extraction of MDBHE causes a gradual underground soil temperature decrease during long-term operation, which diminishes the heat extraction capacity of MDBHE [11,12]. Chen et al. [13] reported that after ten years of operation, the soil temperature at a radial distance of 1 m from the borehole can fall by up to 7.46%, corresponding to a 9.67% reduction in heat extraction capacity. To mitigate this degradation in heat extraction capability, cross-seasonal heat storage is adopted [14,15]. During the non-heating season, the circulating fluid transfers heat to the underground from high-temperature sources such as solar energy and industrial or commercial waste heat, thereby raising the soil temperature. During the heating season, the stored heat is released to maintain or even enhance MDBHE heating performance.

Currently, cross-seasonal heat storage research mainly focuses on optimizing various heat storage parameters [16,17,18]. S. Brown et al. [19] conducted a comprehensive sensitivity analysis on an MDBHE, examining the effects of borehole depth, geothermal gradient, and flow rate on heat storage efficiency. Huang et al. [20] demonstrated that for effective heat storage in an MDBHE, fluid inflow from the inner pipe releases more heat into the surrounding rock and soil, increasing heat storage capacity by 10.81 kW compared to inflow from the annular space under the same conditions. Krusemark et al. [21] analyzed how deviations in borehole trajectories significantly influence the amounts of heat stored and recovered, and the overall storage efficiency. Fu et al. [22] examined the influence of borehole layout, the number of boreholes, inter-borehole spacing, and borehole depth on the seasonal heat storage performance of MDBHE arrays. This is primarily achieved by optimizing the heat storage process to mitigate the decline in MDBHE’s heat extraction performance and improve heat storage efficiency.

During the heat storage process in the non-heating season, soil temperature recovery involves both geothermal heat flux recovery [23] and heat storage [16]. In the geothermal heat flux recovery process, heat is transferred from the higher-temperature radial and deep soil to the lower-temperature soil surrounding the MDBHE. In contrast, during heat storage, heat is transferred from the circulating fluid inside the MDBHE to the surrounding lower-temperature soil. The directions of heat transfer in geothermal heat flux recovery and heat storage are opposite, creating a mutual inhibition effect that limits the full contribution of both processes to soil temperature recovery. Current research on cross-seasonal thermal storage primarily focuses on optimizing various heat storage parameters to improve heat storage efficiency. However, this approach may inadvertently reduce the effectiveness of geothermal heat flux recovery. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the interaction between geothermal heat flux recovery and heat storage to optimize soil temperature recovery and ensure more efficient overall performance.

This paper proposes a novel soil heat deficit regulation-based cross-seasonal heat storage method for MDBHE. By expanding the soil heat deficit, the geothermal heat flux recovery and heat storage are enhanced simultaneously, thereby improving the heating performance of the MDBHE and enhancing indoor thermal comfort. Section 2.1 explains the working principle of this mechanism, while Section 2.2 discusses the development and validation of the model. Using the developed model, the impact of heat extraction temperature (Section 3.1) and heat extraction flow rate (Section 3.2) on the heating performance of MDBHE is analyzed. Finally, Section 4 demonstrates the robustness of the soil heat deficit regulation across different heat storage conditions. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

- A novel soil heat deficit regulation-based cross-seasonal heat storage method for MDBHE is proposed, which expands the soil heat deficit to enhance the geothermal heat flux recovery and heat storage simultaneously.

- (2)

- The effectiveness of the proposed cross-seasonal heat storage method is demonstrated with two soil heat deficit regulation strategies.

- (3)

- The robustness of the soil heat deficit regulation is verified across different heat storage conditions.

2. Methodology

2.1. Working Principles of Cross-Seasonal Heat Storage Based on Soil Heat Deficit Regulation

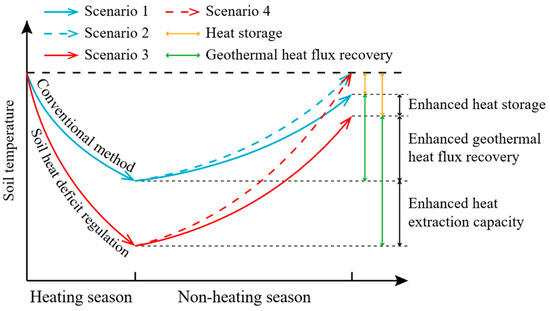

To address the decline in heating performance caused by soil temperature degradation during the heating season (Scenario 1 in Figure 1), a conventional approach is to inject heat into the surrounding soil during the non-heating season using a high-temperature circulating fluid, thereby accelerating soil temperature recovery (Scenario 2 in Figure 1). This study proposes a soil heat deficit regulation-based cross-seasonal heat storage method for MDBHE (Scenario 4 in Figure 1). By expanding the soil heat deficit (i.e., lowering the heat extraction temperature or increasing the heat extraction flow rate), the geothermal heat flux recovery and heat storage are simultaneously enhanced, leading to a significant improvement in the heating performance of MDBHE.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the cross-seasonal heat storage of the MDBHE based on the soil heat deficit regulation. Scenario 1—conventional method without heat storage; Scenario 2—conventional method with heat storage; Scenario 3—soil heat deficit regulation without heat storage; Scenario 4—soil heat deficit regulation with heat storage.

During the cross-seasonal heat storage, soil heat recovery involves two primary processes: (i) geothermal heat flux recovery, where geothermal heat flows from the deep and radial soil layers toward the cooled surrounding soil zone around the MDBHE; and (ii) heat storage, where heat flows from the high-temperature circulating fluid inside the MDBHE toward the cooled surrounding soil zone around the MDBHE. However, the heat transfer direction of these two processes opposes each other, resulting in a phenomenon of mutual inhibition. This opposing heat transfer direction prevents the optimal utilization of geothermal heat flux recovery and reduces the overall efficiency of heat storage, therefore limiting the effectiveness of cross-seasonal heat storage of the MDBHE.

To effectively resolve this issue, this study proposes a soil heat deficit regulation-based cross-seasonal heat storage method for MDBHE. The soil heat deficit is defined as the difference in the amount of heat in the soil before and after the heat extraction, as described in Equation (1). If the soil heat deficit can be replenished during the non-heating season, the heat extraction capacity of MDBHE in the second year can be maintained at the same level as in the first year. By expanding the soil heat deficit, the geothermal heat flux recovery (Scenario 3 in Figure 1) can be enhanced while maintaining sufficient space for cross-seasonal heat storage regulation and improving heat storage efficiency. The effectiveness of this approach will be verified through temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation (Section 3.1) and the flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation (Section 3.2). The robustness of the soil heat deficit regulation will be demonstrated across different heat storage conditions in Section 4.1.

where refers to the soil heat deficit; refers to the amount of heat contained in the soil before heat extraction; refers to the heat contained in the soil after heat extraction; refers to the geothermal heat flux recovery; refers to the heat storage.

2.2. Mathematical Model and Validation

The heat transfer process within the MDBHE is divided into three main parts [24]: (i) heat conduction between the surrounding soil and the outer tube wall; (ii) heat conduction between the outer tube wall and the circulating fluid in the annular space; and (iii) heat conduction between the circulating fluid in the annular space and the circulating fluid inside the inner tube. For simplification, the following assumptions are made: (i) the heat exchange process inside the MDBHE is treated as a quasi-steady-state; (ii) the heat capacity and storage effects of the inner and outer tube walls are neglected, and only heat conduction through the walls is considered; (iii) there are no gaps or thermal contact resistance between the backfill material, tube wall, and borehole wall; and (iv) the thermophysical properties of all materials (including the circulating fluid, backfill, and surrounding soil) are considered as constant.

The numerical model for the MDBHE is developed using the open source finite element software OpenGeoSys 6.3.2 (OGS) [25]. OGS employs a dual-continuum finite element framework to simulate the temporal variations in the inlet and outlet temperatures of the MDBHE, along with the surrounding soil temperature field. In the numerical grid, the MDBHE and its backfill material are represented as one-dimensional line elements, while the surrounding soil is discretized using three-dimensional prismatic elements [3,26]. The governing equations for the circulating fluid inside the inner pipe and annular space are given in Equations (2) and (4), respectively, with Robin-type boundary conditions described in Equations (3) and (5). The heat transfer in the grout surrounding the outer pipe is primarily governed by conduction (assuming that the grout porosity is zero), as expressed in Equation (6), with the corresponding Robin-type boundary condition provided in Equation (7). Finally, the rock temperature is determined by the energy balance equation considering both heat convection and conduction, as shown in Equation (8), with a Neumann-type boundary condition in Equation (9).

where and refer to the density and specific heat capacity of the circulating fluid, respectively. and denote the inner and outer pipe flow velocities, respectively. represents the hydrodynamic thermos-dispersion tensor, which in this case can be simplified as the fluid thermal conductivity. H and are the heat source/sink term and heat transfer boundary, respectively. In the boundary flux terms, and represent the heat transfer coefficients between the inner and outer pipes, and between the outer pipe and grout, respectively. The subscript represents the grout. In the boundary flux term, is the thermal resistance between the grout and rock, and is the soil temperature. The heat transfer coefficients , and are functions of the borehole geometry and thermal resistances. For the detailed calculation method of heat transfer coefficients, readers can refer to [27]. is the effective porosity, and the subscript denotes groundwater. The heat flux boundary condition was imposed on the rock/grout interface .

A numerical heat transfer model is developed to evaluate and optimize the thermal performance of the MDBHE for cross-seasonal heat storage. To accurately simulate heat transfer, the computational domain is set to 200 m × 200 m × 2300 m, ensuring a sufficient distance from the MDBHE to prevent thermal interference at the boundaries. The boundary conditions are defined as follows: (i) a Dirichlet boundary condition is applied to the top surface, governed by the monthly average ambient temperature; (ii) Neumann boundary conditions are assigned to the lateral boundaries [28]; and (iii) a constant heat flux of 60 mW/m2 is imposed at the bottom boundary to represent the local geothermal heat flux [29]. The initial soil temperature field is initialized based on local geological survey data, assuming a surface temperature of 15 °C and a geothermal gradient of 33.0 °C/km [30]. The thermophysical properties of the stratified soil are summarized in Table 1 [31], while the geometric specifications and operational parameters of the MDBHE are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Thermophysical properties of the underground soil with depth.

Table 2.

Basic parameters of the MDBHE model.

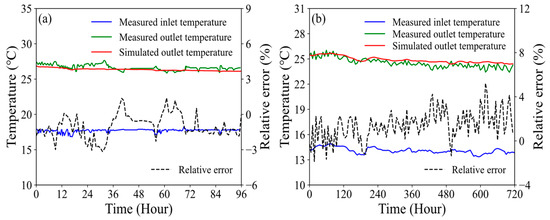

The MDBHE model developed in OGS has been previously validated through analytical solutions, numerical benchmarks, and field experiments [32]. In this study, further validation is carried out by comparing the simulation results with the measured data [33,34] (see Figure 2). In Figure 2a, slight fluctuations in the inlet and outlet temperatures were observed, which can be attributed to variations in outdoor ambient conditions and indoor heating demand. The comparison reveals a maximum relative deviation of 4% between the simulated and measured outlet temperatures. Figure 2b presents a comparison with 720 h of experimental data from another project, where the overall error is found to be less than 6%. Therefore, the developed numerical model is considered reliable for simulating heat transfer between the MDBHE and the surrounding soil, as well as for calculating soil temperatures and the inlet and outlet temperatures.

Figure 2.

Comparison between measured and simulated outlet temperatures: (a) measured outlet temperature reported in Ref. [33]; (b) measured outlet temperature reported in Ref. [34].

2.3. Evaluation Criteria

To assess the impact of expanding the soil heat deficit on cross-seasonal heat storage performance, two evaluation criteria are employed: heat extraction capacity and heat storage efficiency. The calculation formulas are as follows:

where and are the mass flow rates of the circulating fluid during the non-heating season and heating season (kg·s−1); and are the inlet and outlet temperatures (°C); , , , and are the start and end times of the non-heating season and heating season (s); is the simulation time step; and are the heat extraction and heat storage capacity (kW); and are the accumulated extracted and stored heat (J); is the seasonal average heat extraction capacity; is the heat storage efficiency (%). The superscript “storage” refers to the heat supplied after cross-seasonal heat storage; “no storage” refers to the heat supplied without storage.

2.4. Simulated Conditions

The soil heat deficit-based regulation for cross-seasonal heat storage of MDBHE involves both temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation and flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation. The benchmark case in this study is based on the conventional operating conditions commonly used in practical engineering applications. Under the benchmark condition, the heat extraction temperature is set to 21 °C, and the heat extraction flow rate is set to 10 m3/h. To regulate the soil heat deficit, temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation involves gradually decreasing the heat extraction temperature, with four distinct temperature settings: 18 °C, 15 °C, 12 °C, and 9 °C (Section 3.1). Flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation involves gradually increasing the heat extraction flow rate, with four distinct flow rate settings: 15, 20, 25, and 30 m3/h (Section 3.2). During the non-heating season, the heat storage temperature is consistently set to 50 °C, with the heat storage flow rate maintained at 20 m3/h. Furthermore, to demonstrate the robustness of the soil heat deficit regulation under varying heat storage conditions (Section 4.1), the heat storage temperatures are set to 50 °C, 60 °C, and 70 °C based on the maximum soil heat deficit (achieved with a heat extraction temperature of 9 °C and a heat extraction flow rate of 30 m3/h) to compare MDBHE’s performance. These configurations provide a comprehensive evaluation of the impact of soil heat deficit regulation on MDBHE’s cross-seasonal heat storage performance and the robustness of the proposed regulation approach.

3. Results

3.1. Effectiveness of Temperature-Based Soil Heat Deficit Regulation

3.1.1. Soil Heat Deficit Regulation

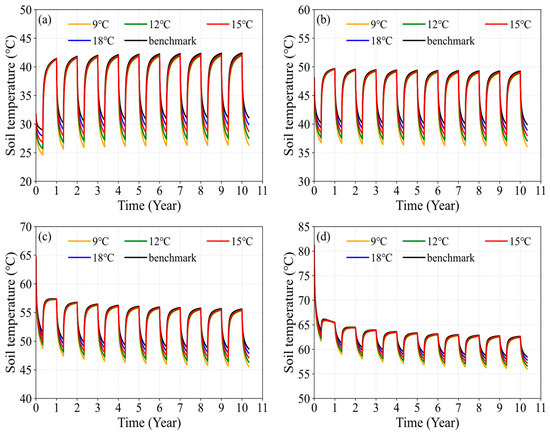

The temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation is achieved by adjusting the heat extraction temperature. Different heat extraction temperatures affect the heat exchange between the circulating fluid and the surrounding soil, thereby altering the soil heat deficit in the surrounding soil zone. Figure 3 shows the variation in soil temperature at 0.7 m from the MDBHE under temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation. During the heating season, lowering the heat extraction temperature reduces soil temperature. For example, at the end of the first heating season, when the heat extraction temperature is reduced from the baseline of 21 °C to 18 °C, 15 °C, 12 °C, and 9 °C, the soil temperature at a depth of 500 m decreases by 1.08 °C, 2.17 °C, 3.25 °C, and 4.34 °C, respectively. A further comparison of soil temperature changes at different depths reveals the impact of heat extraction temperature on soil temperature. When the heat extraction temperature is reduced from the baseline of 21 °C to 9 °C, at the end of the first heating season, the soil temperature decreases by 4.34 °C at 500 m, 3.43 °C at 1000 m, 2.75 °C at 1500 m, and 2.17 °C at 2000 m. This phenomenon arises because, as the heat extraction temperature decreases, the temperature difference between the circulating fluid and the shallow soil layers increases, resulting in more heat being absorbed by the circulating fluid from the shallow soil layer. As the circulating fluid moves deeper, its temperature gradually rises, reducing the amount of additional heat absorbed from the deeper soil layers. Therefore, the temperature drop in the shallow soil layers is greater than that in the deeper soil layers. These results indicate that lowering the heat extraction temperature increases the soil heat deficit, with this deficit being primarily concentrated in the shallow soil layers.

Figure 3.

Variation in soil temperature under temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation: (a) 500 m depth; (b) 1000 m depth; (c) 1500 m depth; (d) 2000 m depth.

The heat storage process during the non-heating season accelerates soil temperature recovery. However, different heat extraction temperatures create varying soil temperature fields at the beginning of the non-heating season, affecting heat storage performance. For example, the soil temperature in the benchmark condition increased by 12.52 °C (43.22%) at a depth of 500 m during the first non-heating season. In contrast, when the heat extraction temperatures are set to 18 °C, 15 °C, 12 °C, and 9 °C, the soil temperature increased by 13.55 °C (48.61%), 14.58 °C (54.43%), 15.61 °C (60.71%), and 16.65 °C (67.61%), respectively. This indicates that as the heat extraction temperature decreases, the increase in soil temperature becomes more pronounced during the non-heating season. Therefore, while the soil temperature difference at the beginning of the non-heating season is more pronounced, this difference diminishes significantly by the end of the non-heating season. For example, at the beginning of the first non-heating season, the maximum soil temperature differences at depths of 500, 1000, 1500, and 2000 are 4.34 °C, 3.43 °C, 2.75 °C, and 2.17 °C, respectively. By the end of the first non-heating season, these differences reduce to 0.22 °C, 0.16 °C, 0.13 °C, and 0.11 °C. This happens because lower heat extraction temperatures lead to a greater soil heat deficit at the beginning of the non-heating season. This, in turn, enhances both geothermal heat flux recovery and heat storage, ultimately accelerating soil temperature recovery. In conclusion, the lower the heat extraction temperature, the stronger the geothermal heat flux recovery and heat storage during the non-heating season, resulting in more significant soil temperature recovery. The soil heat deficit induced by lowering the heat extraction temperature is largely recovered.

3.1.2. Effects on Heat Extraction Capacity

The variation in heat extraction temperature directly influences the heat extraction capacity of the MDBHE, as shown in Figure 4. Compared to the benchmark condition, a lower heat extraction temperature results in a greater increase in the heat extraction capacity of the MDBHE, with the most significant enhancement occurring at the start of the heating season. For example, at the beginning of the first heating season, compared to the benchmark condition, the heat extraction capacities at heat extraction temperatures of 18 °C, 15 °C, 12 °C, and 9 °C increased by 19.70 kW (13.41%), 39.38 kW (26.80%), 59.08 kW (40.21%), and 78.77 kW (53.61%), respectively. By the end of the first heating season, the heat extraction capacities at the same temperatures increased by 10.45 kW (11.12%), 19.69 kW (22.22%), 29.54 kW (33.34%), and 39.38 kW (44.45%), respectively, compared to the benchmark condition. This occurs because, when the heat extraction temperature is lowered, the temperature difference between the circulating fluid and the surrounding soil increases, leading to a significant increase in the heat extraction capacity of MDBHE.

Figure 4.

Variation in heat extraction capacity under temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation: (a) hourly variation; (b) seasonal average value.

Figure 4b shows the variation in the seasonal average heat extraction capacity of the MDBHE under temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation. Lowering the heat extraction temperature greatly enhances the seasonal average heat extraction capacity of MDBHE. For example, in the first heating season, reducing the heat extraction temperature to 18 °C, 15 °C, 12 °C, and 9 °C results in increases in the seasonal average heat extraction capacity of 10.76, 21.52, 32.28, and 43.04 kW (11.20%, 22.41%, 33.61%, and 44.82%), respectively, compared to the benchmark condition. Over the entire operational period, temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation produces a maximum increase of 44.82% in the MDBHE’s seasonal average heat extraction capacity compared to the benchmark condition. During the entire operational period, the seasonal average heat extraction capacity in the benchmark condition increases slightly from 96.03 kW to 96.14 kW. In contrast, lowering the heat extraction temperature slightly reduces the seasonal average heat extraction capacity. For heat extraction temperatures of 18 °C, 15 °C, 12 °C, and 9 °C, the seasonal average heat extraction capacity decreases by only 0.36%, 0.74%, 1.32%, and 1.06%, respectively. Overall, temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation significantly improves the heat extraction capacity of MDBHE, with only a slight decrease in seasonal average heat extraction capacity over the operational period.

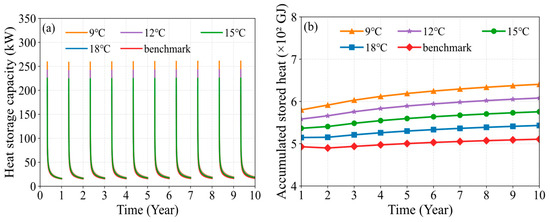

3.1.3. Effects on Heat Storage Efficiency

The variation in heat extraction temperature during the heating season alters the underground soil temperature field, which subsequently affects the heat storage capacity of MDBHE during the non-heating season. Figure 5a shows the changes in MDBHE’s heat storage capacity during the non-heating season under temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation. Compared to the benchmark condition, lowering the heat extraction temperature leads to a greater increase in heat storage capacity at the start of the non-heating season. However, the differences in heat storage capacity become minimal by the end of the non-heating season. For example, at the beginning of the first non-heating season, lowering the heat extraction temperature to 18 °C, 15 °C, 12 °C, and 9 °C increases the heat storage capacity of the MDBHE by 16.94, 33.87, 50.81, and 67.74 kW (8.86%, 17.71%, 26.57%, and 35.42%), respectively, compared to the benchmark condition. By the end of the first non-heating season, these increases are reduced to 0.33, 0.67, 1.00, and 1.32 kW (2.13%, 4.41%, 6.53%, and 8.66%), respectively. This occurs because a lower heat extraction temperature creates a larger soil heat deficit at the beginning of the non-heating season, leading to a greater increase in MDBHE’s heat storage capacity. However, as heat storage progresses, the soil heat deficit diminishes, which consequently reduces the increase in MDBHE’s heat storage capacity.

Figure 5.

Variation in (a) heat storage capacity and (b) accumulated stored heat of the MDBHE under temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation.

Figure 5b illustrates the variation in the accumulated stored heat of the MDBHE during the non-heating season under temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation. Compared to the benchmark condition, lowering the heat extraction temperature significantly increases the accumulated stored heat, with a more pronounced increase over the operational period. For example, in the first non-heating season, reducing the heat extraction temperature to 18 °C, 15 °C, 12 °C, and 9 °C results in an increase in accumulated stored heat from 492.87 GJ (benchmark condition) to 514.70, 536.54, 558.32, and 580.11 GJ, respectively, corresponding to increases of 4.52%, 9.04%, 13.54%, and 18.05%. Over the entire operational period, the accumulated stored heat under the benchmark condition increases by 3.62%. In contrast, when the heat extraction temperature is lowered to 18 °C, 15 °C, 12 °C, and 9 °C, the accumulated stored heat increases by 5.53%, 7.29%, 8.92%, and 10.43%, respectively. This is due to the larger soil heat deficit induced by lower heat extraction temperatures, which increases over time and enables more heat to be stored. Overall, temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation significantly enhances the accumulated stored heat during the non-heating season.

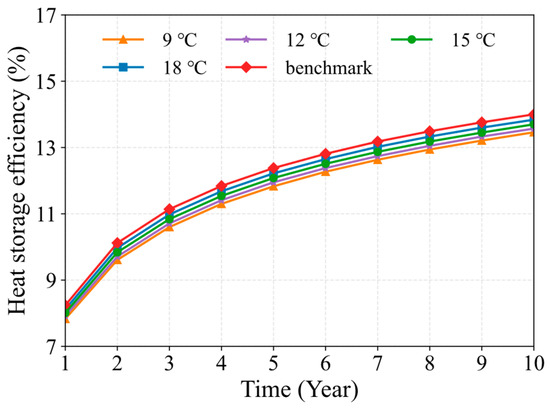

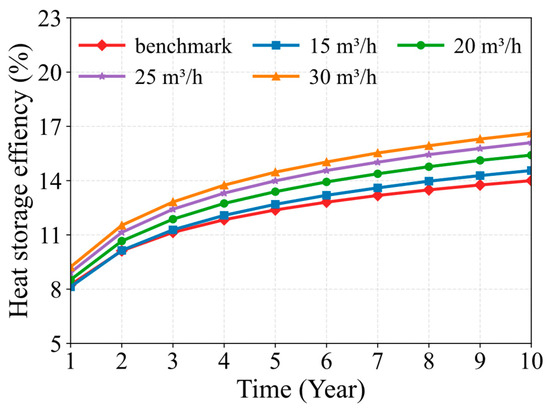

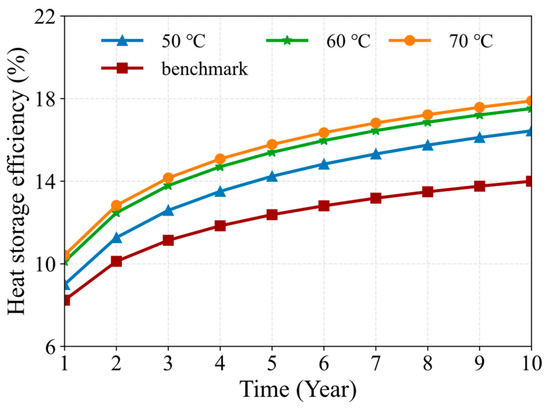

Figure 6 shows the variation in heat storage efficiency over time under temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation. It can be observed that heat storage efficiency gradually increases over the operational period. However, lowering the heat extraction temperature slightly decreases the MDBHE’s heat storage efficiency. For instance, under the benchmark condition, the heat storage efficiency increases from 8.24% to 14.00% over the entire operational period. When the heat extraction temperature is lowered from the benchmark condition to 18 °C, 15 °C, 12 °C, and 9 °C, the heat storage efficiency in the first year decreases from 8.24% to 8.12%, 8.01%, 7.92%, and 7.83%, respectively. Over the entire operational period, the maximum reduction in heat storage efficiency compared to the benchmark condition under temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation is only 0.54%. This is because lowering the heat extraction temperature concentrates the soil heat deficit in the shallow soil layers, where most of the heat is stored during the non-heating season. This increases the thermal influence radius of the shallow soil. Consequently, a larger portion of the heat stored in the shallow soil dissipates during the heating season, leading to a slight reduction in the MDBHE’s heat storage efficiency. Overall, temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation significantly enhances geothermal heat flux recovery and heat storage, greatly improving the heat extraction capacity (as shown in Figure 4), while the reduction in heat storage efficiency is minimal (as shown in Figure 6). Therefore, temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation proves to be an effective method for improving the MDBHE’s cross-seasonal heat storage performance.

Figure 6.

Variation in heat storage efficiency of the MDBHE under temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation.

3.2. Effectiveness of Flow Rate-Based Soil Heat Deficit Regulation

3.2.1. Soil Heat Deficit Regulation

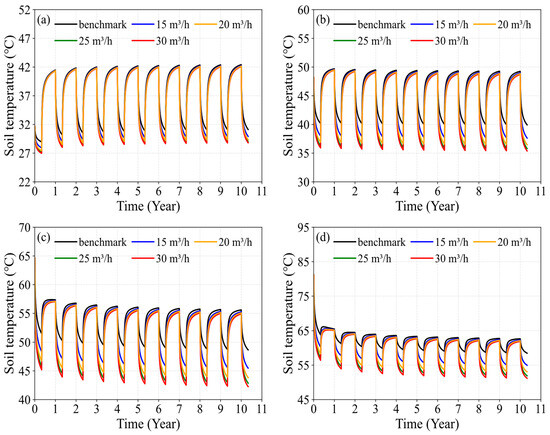

The flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation is achieved by adjusting the heat extraction flow rate. Variations in the flow rate affect the heat exchange between the circulating fluid and the surrounding soil, which in turn influences the soil heat deficit within the surrounding soil zone. Figure 7 illustrates the variation in soil temperature at a distance of 0.7 m from the MDBHE under different flow rate-based soil heat deficit conditions. During the heating season, increasing the heat extraction flow rate leads to a reduction in soil temperature. For instance, at the end of the first heating season, when the heat extraction flow rate is increased from the baseline of 10 m3/h to 15, 20, 25, and 30 m3/h, the soil temperature at 500 m depth decreases by 1.03 °C, 1.55 °C, 1.83 °C, and 2.00 °C, respectively. When the flow rate increases from the baseline of 10 m3/h to 30 m3/h, the soil temperature at the end of the first heating season decreases by 2.00 °C at 500 m, 4.26 °C at 1000 m, 6.31 °C at 1500 m, and 7.24 °C at 2000 m, compared to the benchmark condition. This occurs because, as the flow rate increases, the heat exchange time between the circulating fluid and the shallow soil layers decreases, resulting in less efficient heat transfer. Consequently, the circulating fluid’s temperature during heat exchange with deeper soil layers is lower, allowing it to absorb more heat from the deep soil layers. As a result, the temperature decrease is more significant in the deeper soil layers than in the shallow soil layers. These results suggest that increasing the heat extraction flow rate enhances the soil heat deficit, which is primarily concentrated in the deeper soil layers.

Figure 7.

Variation in soil temperature under flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation: (a) 500 m depth; (b) 1000 m depth; (c) 1500 m depth; (d) 2000 m depth.

The heat storage process during the non-heating season accelerates soil temperature recovery. However, varying heat extraction flow rates create different soil temperature profiles at the beginning of the non-heating season, which subsequently influences heat storage performance. For example, in the first non-heating season, the soil temperature under the benchmark condition increased by 12.52 °C (43.22%) at a depth of 500 m. In comparison, with heat extraction flow rates set to 15, 20, 25, and 30 m3/h, the soil temperature increased by 13.49 °C (48.28%), 13.97 °C (50.94%), 14.23 °C (52.45%), and 14.39 °C (53.37%), respectively. This demonstrates that increasing the heat extraction flow rate results in a more significant increase in soil temperature during the non-heating season. As a result, although the soil temperature difference at the beginning of the non-heating season is more pronounced with higher heat extraction flow rates, this difference decreases considerably by the end of the non-heating season. For instance, at the beginning of the first non-heating season, the maximum temperature differences at 500, 1000, 1500, and 2000 m, compared to the benchmark condition, are 2.00 °C, 4.26 °C, 6.31 °C, and 7.42 °C, respectively. By the end of the first non-heating season, these differences narrowed to 0.13 °C, 0.23 °C, 0.32 °C, and 0.41 °C. This phenomenon occurs because higher heat extraction flow rates lead to a larger soil heat deficit at the beginning of the non-heating season, enhancing both geothermal heat flux recovery and heat storage, thus accelerating soil temperature recovery. The soil heat deficit created by higher heat extraction flow rates is largely restored by the end of the non-heating season.

3.2.2. Effects on Heat Extraction Capacity

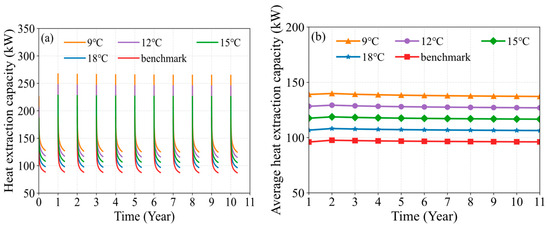

As shown in Figure 8, variations in the heat extraction flow rate directly impact the heat extraction capacity of the MDBHE. Compared to the benchmark condition, higher heat extraction flow rates result in greater improvements in the heat extraction capacity of the MDBHE, with more significant increases observed at the beginning of the heating season. For example, at the beginning of the first heating season, when the heat extraction flow rates are set to 15, 20, 25, and 30 m3/h, the heat extraction capacity of the MDBHE increases by 88.81 kW (60.45%), 149.26 kW (101.60%), 186.31 kW (126.81%), and 207.75 kW (141.41%) relative to the benchmark condition. However, by the end of the first heating season, the corresponding improvements in heat extraction capacity are 21.72 kW (24.51%), 32.80 kW (37.02%), 39.08 kW (44.11%), and 42.98 kW (48.50%) relative to the benchmark condition. This phenomenon occurs because, at the beginning of the heating season, the soil temperature is relatively higher. When the heat extraction flow rate is increased, the heat extraction capacity improves more significantly. However, as heat is extracted and the soil temperature decreases, the additional increase in heat extraction capacity with further increases in heat extraction flow rate becomes less pronounced.

Figure 8.

Variation in heat extraction capacity under flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation: (a) hourly variation; (b) seasonal average value.

Figure 8b illustrates the variation in the seasonal average heat extraction capacity of the MDBHE under flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation. Increasing the heat extraction flow rate significantly improves the seasonal average heat extraction capacity of the MDBHE. For example, during the first heating season, when the heat extraction flow rate is increased to 15, 20, 25, and 30 m3/h, the seasonal average heat extraction capacity increases by 26.51 kW, 40.55 kW, 48.65 kW, and 53.71 kW, corresponding to improvements of 27.60%, 42.23%, 50.66%, and 55.93%, respectively, compared to the benchmark condition. Over the entire operational period, the seasonal average heat extraction capacity of MDBHE increased by a maximum of 55.93% under flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation. In contrast, under the benchmark condition, the seasonal average heat extraction capacity slightly increased from 96.03 kW to 96.14 kW. However, increasing the heat extraction flow rate slightly reduces the seasonal average heat extraction capacity. At flow rates of 15, 20, 25, and 30 m3/h, the seasonal average heat extraction capacity decreases by 2.35%, 3.29%, 3.73%, and 3.98%, respectively. Overall, flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation significantly enhances the heat extraction capacity of MDBHE, with only a slight decrease in the seasonal average heat extraction capacity over the entire operational period.

3.2.3. Effects on Heat Storage Efficiency

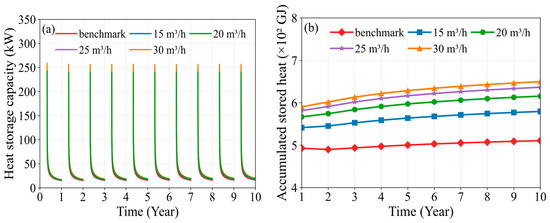

The variation in heat extraction flow rate during the heating season alters the underground soil temperature field, which subsequently affects the MDBHE’s heat storage capacity during the non-heating season. Figure 7 illustrates the variation in MDBHE’s heat storage capacity during the non-heating season under flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation. Compared to the benchmark condition, increasing the heat extraction flow rate significantly enhances the heat storage capacity at the beginning of the non-heating season. However, by the end of the non-heating season, the difference in heat storage capacity becomes much smaller. For example, at the beginning of the first non-heating season, when the heat extraction flow rate is increased to 15, 20, 25, and 30 m3/h, the MDBHE’s heat storage capacity increases by 33.85, 51.32, 61.26, and 67.46 kW, corresponding to improvements of 17.70%, 26.83%, 32.03%, and 35.28%, respectively, compared to the benchmark condition. By the end of the first non-heating season, the increase in heat storage capacity is reduced to 0.81, 1.23, 1.49, and 1.65 kW, corresponding to improvements of 5.32%, 8.05%, 9.73%, and 10.79%. This occurs because higher heat extraction flow rates lead to a greater soil heat deficit at the beginning of the non-heating season, which leads to a larger increase in MDBHE’s heat storage capacity. However, as the heat storage process progresses, the soil heat deficit decreases significantly, which in turn reduces the enhancement in heat storage capacity.

Figure 9b shows the variation in the accumulated stored heat of MDBHE during the non-heating season under flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation. Compared to the benchmark condition, increasing the heat extraction flow rate significantly boosts the accumulated stored heat, with a more substantial increase observed over the entire operational period. For example, during the first non-heating season, increasing the heat extraction flow rate to 15, 20, 25, and 30 m3/h leads to an increase in accumulated stored heat from 492.87 GJ (benchmark condition) to 541.37 GJ, 566.76 GJ, 581.39 GJ, and 590.58 GJ, corresponding to increases of 9.84%, 14.99%, 17.96%, and 19.82%, respectively. Over the entire operational period, the accumulated stored heat under the benchmark condition increases by 3.62%. In contrast, when the heat extraction flow rate is raised to 15, 20, 25, and 30 m3/h, the accumulated stored heat increases by 8.14%, 8.63%, 9.49%, and 10.02%, respectively. This occurs because a higher heat extraction flow rate leads to a greater soil heat deficit, and over time, the increasing soil heat deficit allows for more heat to be stored. However, as the flow rate increases, the rate of increase in accumulated stored heat gradually decreases. For instance, during the first non-heating season, for every 5 m3/h increase in heat extraction flow rate, the accumulated stored heat increases by 9.84%, 4.69%, 2.58%, and 1.58%, respectively. In conclusion, increasing the heat extraction flow rate significantly enhances the soil heat deficit, thereby improving MDBHE’s heat storage capacity. However, as the heat extraction flow rate increases, the rate of increase in accumulated stored heat gradually diminishes.

Figure 9.

Variation in (a) heat storage capacity and (b) accumulated stored heat of the MDBHE under flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation.

Figure 10 illustrates the temporal variation in heat storage efficiency under flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation. It is evident that heat storage efficiency increases gradually over the operational period. Moreover, higher heat extraction flow rates lead to enhanced heat storage efficiency for MDBHE. For example, under the benchmark condition, heat storage efficiency increases from 8.24% to 14.00% over the entire operational period. When the heat extraction flow rate is increased from the baseline of 10 m3/h to 15, 20, 25, and 30 m3/h, the heat storage efficiency in the first year shifts from 8.24% to 8.13%, 8.52%, 8.92%, and 9.23%, while in the last year it increases from 14.00% to 14.56%, 15.41%, 16.10%, and 16.62%, respectively. Over the entire operational period, flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation results in a maximum improvement of 18.71% (from 14.00% to 16.62%) compared to the benchmark condition. This improvement is attributed to the fact that increasing the heat extraction flow rate focuses the soil heat deficit in deeper soil layers. The lower temperatures in these deeper soils create favorable conditions for the circulating fluid to store more heat, progressively enhancing the heat storage efficiency of the MDBHE. In summary, flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation significantly expands the soil heat deficit, leading to enhanced geothermal heat flux recovery and heat storage, and consequently improving both heat extraction capacity and heat storage efficiency of MDBHE.

Figure 10.

Variation in heat storage efficiency of the MDBHE under flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Robustness of Soil Heat Deficit Regulation

The previous section discussed the effectiveness of the proposed cross-seasonal heat storage regulation under both temperature-based and flow rate-based soil heat deficit conditions. Building on this, the current section examines the robustness of soil heat deficit regulation under different heat storage conditions during the non-heating season. Specifically, while the heat storage temperature in the previous section was set to 50 °C, in this section, the heat storage temperature is adjusted to 50 °C, 60 °C, and 70 °C, all based on the maximum soil heat deficit. The response of heat extraction capacity and heat storage efficiency of MDBHE is then evaluated over multiple years to assess the robustness of the proposed soil heat deficit regulation.

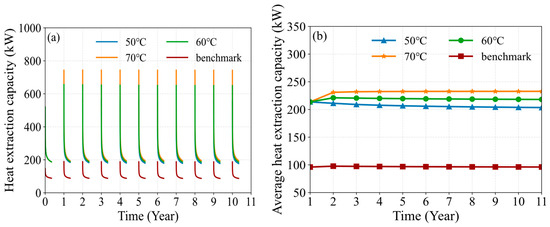

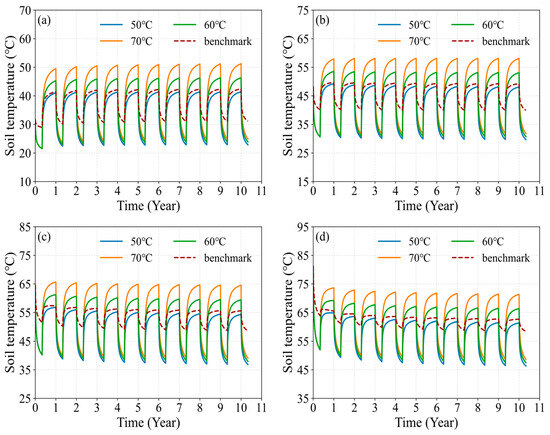

As shown in Figure 11, compared to the benchmark condition, the heat extraction capacity of MDBHE increases significantly with the expansion of the heat deficit, and the higher the heat storage temperature, the greater the heat extraction capacity. However, under different heat storage temperatures, the difference in heat extraction capacity at the beginning of the heating season is more pronounced, while at the end of the heating season, the heat extraction capacity becomes almost identical. For example, when the heat storage temperatures are 50 °C, 60 °C, and 70 °C, compared to the benchmark condition, the heat extraction capacity at the beginning of the first heating season after cross-seasonal heat storage increases by 379.83 kW, 466.8 kW, and 553.85 kW, corresponding to increases of 200.92%, 246.95%, and 292.97%, respectively. However, by the end of the heating season, the increase in heat extraction capacity drops to 95.85 kW, 100.38 kW, and 105.69 kW, with increases of 108.19%, 113.31%, and 118.89%, respectively, and the difference in heat extraction capacity decreases significantly. This is because higher heat storage temperatures raise the surrounding soil temperature (as shown in Figure 12), resulting in a larger difference in heat extraction capacity at the beginning of the heating season. However, as the heating season progresses, the surrounding soil temperature under different heat storage conditions gradually becomes more uniform, narrowing the gap in heat extraction capacity by the end of the heating season.

Figure 11.

Variation in heat extraction capacity under different heat storage conditions: (a) hourly variation; (b) seasonal average value.

Figure 12.

Variation in soil temperature under different heat storage conditions: (a) 500 m depth; (b) 1000 m depth; (c) 1500 m depth; (d) 2000 m depth.

Higher heat storage temperatures and an expanded soil heat deficit result in a stronger seasonal average heat extraction capacity for MDBHE, with a smaller decrease in seasonal average heat extraction capacity over time. In some cases, the seasonal average heat extraction capacity even increases with higher heat storage temperatures and a greater soil heat deficit. Figure 11b illustrates the variation in MDBHE’s seasonal average heat extraction capacity under different heat storage conditions. When the soil heat deficit is maximized, the seasonal average heat extraction capacity is significantly higher at heat storage temperatures of 50 °C, 60 °C, and 70 °C compared to the benchmark condition. Specifically, at heat storage temperatures of 50 °C, 60 °C, and 70 °C, with an expanded soil heat deficit, the seasonal average heat extraction capacity increases by 122.50%, 126.88%, and 142.01%, respectively, compared to the benchmark condition. Under the benchmark condition, MDBHE’s seasonal average heat extraction capacity increases slightly from 96.03 kW to 96.14 kW, a 0.11% increase. However, when the heat storage temperature is 50 °C with an expanded soil heat deficit, the seasonal average heat extraction capacity decreases from 213.67 kW to 203.48 kW, a reduction of 4.77%. At a heat storage temperature of 60 °C with expanded soil heat deficit, the seasonal average heat extraction capacity increases from 213.67 kW to 218.12 kW, representing an overall increase of 2.08%. At a heat storage temperature of 70 °C with expanded soil heat deficit, the seasonal average heat extraction capacity increases from 213.67 kW to 232.76 kW, a total increase of 8.93%. This improvement is due to the heat storage during the non-heating season, raising the surrounding soil temperature, thereby increasing the temperature difference between the circulating fluid and the surrounding soil at the beginning of the heating season. The increased temperature difference enhances MDBHE’s seasonal average heat extraction capacity. In conclusion, increasing the soil heat deficit and adjusting the heat storage temperature can significantly improve MDBHE’s heat extraction capacity.

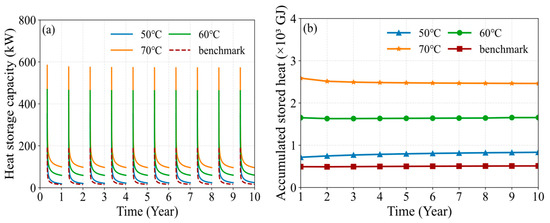

The heat storage temperature and soil heat deficit directly influence the heat storage capacity of the MDBHE. As shown in Figure 13a, higher heat storage temperatures and increased soil heat deficit significantly improve the heat storage capacity of MDBHE, particularly at the beginning of the non-heating season. For example, at the start of the first non-heating season, compared to the benchmark condition, the heat extraction capacity increases by 161.94 kW (84.68%), 277.31 kW (145.01%), and 392.65 kW (205.32%) when the heat storage temperature is set to 50 °C, 60 °C, and 70 °C, respectively. This improvement is attributed to the higher heat storage temperatures and increased soil heat deficit, which amplify the temperature difference between the circulating fluid and the surrounding soil, thereby boosting the heat transfer driving force and enhancing the heat storage capacity. Furthermore, the accumulated stored heat of MDBHE during the non-heating season also increases significantly, as shown in Figure 13b. For instance, during the first non-heating season, compared to the benchmark condition, the accumulated stored heat increases by 222.63 GJ (45.17%), 1158.83 GJ (235.19%), and 2094.96 GJ (425.05%) when the heat storage temperature is set to 50 °C, 60 °C, and 70 °C, respectively. In contrast, under the benchmark condition, the accumulated stored heat increases slightly over time, with a total increase of 3.62% over the entire operational period. However, under the expanded soil heat deficit, the cumulative heat storage changes by 16.43%, 0.21%, and −4.83% over the entire operational period when the heat storage temperatures are 50 °C, 60 °C, and 70 °C, respectively. This suggests that while increasing the heat storage temperature in combination with an expanded soil heat deficit significantly boosts the heat storage capacity and accumulated stored heat of MDBHE, higher heat storage temperatures lead to a slight decrease in accumulated stored heat.

Figure 13.

Variation in (a) heat storage capacity and (b) accumulated stored heat of the MDBHE under different heat storage conditions.

Figure 14 illustrates the variation in heat storage efficiency of MDBHE under different heat storage temperatures and soil heat deficits during cross-seasonal heat storage. Compared to the benchmark condition, increasing both the heat storage temperature and soil heat deficit significantly enhances the heat storage efficiency of MDBHE. For example, in the first year, the heat storage efficiency under the benchmark condition is 8.24%, while under increased soil heat deficit, the efficiency at heat storage temperatures of 50 °C, 60 °C, and 70 °C increases to 9.00%, 10.11%, and 10.42%, respectively. Over the entire operational period, increasing both the soil heat deficit and heat storage temperature results in a maximum improvement of 27.79% (from 14.00% to 17.89%) in heat storage efficiency compared to the benchmark condition. However, when the heat storage temperature increases from 60 °C to 70 °C, the improvement in heat storage efficiency is much smaller compared to the increase from 50 °C to 60 °C. For instance, in the first year, when the heat storage temperature increases from 50 °C to 60 °C, the heat storage efficiency increases from 9.00% to 10.11%, a 12.33% increase. In contrast, when the heat storage temperature increases from 60 °C to 70 °C, the efficiency only rises from 10.11% to 10.42%, a 3.07% increase. In conclusion, increasing both the soil heat deficit and heat storage temperature significantly improves the MDBHE’s heat extraction capacity and heat storage efficiency, confirming the robustness of the proposed soil heat deficit regulation. However, when the heat storage temperature exceeds a certain level (e.g., above 60 °C), the efficiency gains from further increases in heat storage temperature become less pronounced.

Figure 14.

Variation in heat storage efficiency of the MDBHE under different heat storage conditions.

4.2. Limitations and Outlook

This study analyzes the heat extraction capacity and heat storage efficiency of the MDBHE under temperature-based and flow-rate-based soil heat deficit regulation. The results indicate that increasing the soil heat deficit can significantly enhance the heat extraction capacity of the MDBHE. Furthermore, the robustness of the soil heat deficit regulation is demonstrated across different heat storage conditions. However, it is important to note that while increasing the heat extraction flow rate and raising the heat storage temperature lead to improved performance, they also result in higher operational costs for the MDBHE. As such, careful consideration of economic factors is essential during the design phase. It is worth mentioning that this study focuses on verifying the effectiveness of temperature-based and flow-rate-based soil heat deficit regulation, without providing the optimal combination of heat extraction temperature, heat extraction flow rate, heat storage temperature, and heat storage flow rate. Future research could explore the use of advanced machine learning techniques, such as deep learning models [35], to optimize these parameter combinations, ultimately improving both the heating performance and heat storage efficiency of the MDBHE. Additionally, there is potential to improve heat transfer efficiency to enhance the overall heating performance of MDBHE. Future work will explore enhanced heat transfer technologies, such as enhanced surfaces like spiral tube walls [36], which can boost heat exchange efficiency by increasing surface area and optimizing fluid dynamics.

5. Conclusions

This study proposes a novel cross-seasonal heat storage method based on soil heat deficit regulation for the MDBHE, which expands the soil heat deficit to enhance the geothermal heat flux recovery and heat storage simultaneously, while also improving indoor thermal comfort. The effectiveness of the proposed cross-seasonal heat storage regulation method is analyzed under temperature-based and flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulations. The robustness of the soil heat deficit regulation is demonstrated across different heat storage conditions. The main findings of the study are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- The effectiveness of the proposed cross-seasonal thermal storage regulation method is analyzed under temperature-based and flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulations. Under the temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation, the soil heat deficit was mainly concentrated in the shallow soil layers, while the flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation was mainly concentrated in the deep soil layers.

- (2)

- The flow rate-based soil heat deficit regulation is more effective than the temperature-based soil heat deficit regulation. Expanding the soil heat deficit by lowering the heat extraction temperature increases the heat extraction capacity of MDBHE by up to 44.82% (from 93.03 kW to 139.07 kW), with relatively stable heat storage efficiency. In contrast, expanding the soil heat deficit by increasing the heat extraction flow rate enhances the heat extraction capacity by up to 55.93% (from 93.03 kW to 149.74 kW) and improves heat storage efficiency by up to 18.71%.

- (3)

- The robustness of the soil heat deficit regulation is verified under various heat storage conditions. Increasing both the heat storage temperature and the soil heat deficit significantly enhances the heat extraction capacity and heat storage efficiency. However, once the heat storage temperature reaches a certain level, further increases in heat storage temperature result in diminishing returns in heat storage efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.W. and S.Z.; methodology, R.W. and Y.Z.; software, J.L., Y.Z. and R.W.; validation, Y.Z. and J.Z.; formal analysis, J.L. and Y.Z.; investigation, J.L. and J.Z.; resources, Y.Z. and J.Z.; data curation, R.W. and H.S.; Writing—original draft, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L., R.W. and H.S.; visualization, R.W. and Z.F.; supervision, S.Z. and Z.F.; project administration, J.L. and S.Z.; funding acquisition, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is financially supported by the Key Laboratory of Coal Resources Exploration and Comprehensive Utilization, Ministry of Natural Resources (Project No. SMDZ-KF2024-5); Shaanxi Innovation Capacity Support Plan (Project No. 2025JC-GXPT-040); Shaanxi Innovation Capacity Support Plan (Project No. 2025ZC-KJXX-05); Key Research and Development Project of Shaanxi Province (Project No. 2024SF-YBXM-596, 2024SF-YBXM-604); and High-Level Talent Programme of Shaanxi Province (Project No. 050700/71240000000113).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Jun Liu and Yuping Zhang were employed by the company Shaanxi Coal Geology Group Company Limited. Author Jingyue Zhang was employed by the company Shaanxi Coal Geology Investigation Research Institute Co., Ltd. Author Heng Shi was employed by the company Qingdao Haier Air Conditioner Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDBHE | Medium-deep borehole heat exchanger |

| COP | Coefficient of performance |

| OGS | OpenGeoSys |

| soil heat deficit | |

| Amount of heat contained in the soil before heat extraction | |

| Amount of heat contained in the soil after heat extraction | |

| Geothermal heat flux recovery | |

| Heat storage | |

| Density of the circulating fluid | |

| Specific heat capacity of the circulating fluid | |

| Inner pipe flow velocities | |

| Outer pipe flow velocities | |

| Hydrodynamic thermos-dispersion tensor | |

| H | Heat source/sink term |

| Heat transfer boundary | |

| Heat transfer coefficients | |

| Soil temperature | |

| Effective porosity | |

| Mass flow rates of the circulating fluid during the non-heating season | |

| Mass flow rates of the circulating fluid during the heating season | |

| Inlet temperatures | |

| Outlet temperatures | |

| Start time of the non-heating season | |

| End time of the non-heating season | |

| Start time of the heating season | |

| End time of the heating season | |

| Heat extraction capacity | |

| Heat storage capacity | |

| Accumulated extracted heat | |

| Accumulated stored heat | |

| Seasonal average heat extraction capacity | |

| Heat storage efficiency |

References

- Afolabi, J.A. Towards carbon neutrality in Europe: The role of technology exports, renewable energy consumption, and resource productivity. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 395, 127862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Gordon, J.A.; Lu, X.; Zhang, D.; Davidson, M.R. Reaching carbon neutrality in China: Temporal and subnational limitations of renewable energy scale-up. Adv. Appl. Energy 2025, 20, 100238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolo, I.; Brown, C.S.; Nibbs, W.; Cai, W.; Falcone, G.; Nagel, T.; Chen, C. A comprehensive review of deep borehole heat exchangers (DBHEs): Subsurface modelling studies and applications. Geotherm. Energy 2024, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, P.; Cai, W.; Sun, X.; Chen, C. In-situ test and numerical investigation on the long-term performance of deep borehole heat exchanger coupled heat pump heating system. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 61, 104855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhan, T.; Liu, G.; Ni, L. A field test of medium-depth geothermal heat pump system for heating in severely cold region. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 48, 103125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Ma, M.; Wei, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, M. A specially-designed test platform and method to study the operation performance of medium-depth geothermal heat pump systems (MD-GHPs) in newly-constructed project. Energy Build. 2022, 272, 112369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Shen, J.; Song, Y.; Tian, Z.; Fan, J.; Zhang, L. A unified analytical model for vertical ground heat exchangers: Non-uniform finite line source method (NFLS). Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Ye, J.; Ni, L.; Sun, C. Analytical and semi-analytical models of multi-applicability for medium-deep borehole heat exchanger. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 344, 120282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L. Thermal performance analysis of a deep coaxial borehole heat exchanger with a horizontal well based on a novel semi-analytical model. Renew. Energy 2025, 239, 122073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhou, C.; Huang, X.; Luo, H.; Luo, Y.; Cheng, N.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, S.; Fan, J.; Zhang, L. Study on thermal radius and capacity of multiple deep borehole heat exchangers: Analytical solution, algorithm and application based on Response Factor Matrix method (RFM). Energy 2024, 296, 131132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Niu, D.; Wang, F.; Chai, J.; Lu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lin, Z. Effects of climate change on long-term building heating performance of medium-deep borehole heat exchanger coupled heat pump. Energy Build. 2023, 293, 113208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Ma, D. Heat transfer and rock-soil temperature distribution characteristics in whole life cycle for different structure sizes of medium-deep U-shaped butted well. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 60, 104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Yang, F.; Tan, H.; Wang, B. Field measurements and numerical investigation on heat transfer characteristics and long-term performance of deep borehole heat exchangers. Renew. Energy 2023, 205, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, G.; Li, X.; Pan, Y. Numerical investigation on thermal storage and release characteristics of ground heat exchangers under cross-seasonal multi-cycle operation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 281, 128574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Dennehy, C.; Javed, S.; Garber-Slaght, R.; Dunn, K.; Zody, Z.J.; Potter, J.; Wagner, A. Techno-economic feasibility of borehole thermal energy storage system connected to geothermal heat pumps for seasonal heating load of two buildings in Fairbanks, Alaska. Energy Build. 2025, 345, 116036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyska, C.; Zábranová, E. Seasonal energy extraction and storage by deep coaxial borehole heat exchangers in a layered ground. Renew. Energy 2024, 237, 121530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Deng, J.; Liao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, M.; Peng, C.; Wei, Q.; Cai, W.; Yu, J. How to make full use of heat storage characteristic of mid-deep borehole heat exchangers hybrid with heat pump storage systems: Field tests and simulation analysis. Energy 2025, 338, 138906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yu, M.; Mao, Y.; Zhu, K.; Yang, J.; Zhang, W.; Cui, P. Operation characteristics of mid-deep U-type borehole heat exchanger with heat storage in non-heating seasons. J. Energy Storage 2025, 111, 115379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.S.; Kolo, I.; Falcone, G.; Banks, D. Repurposing a deep geothermal exploration well for borehole thermal energy storage: Implications from statistical modelling and sensitivity analysis. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 220, 119701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, J.; Zhu, K.; Dong, J.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y. Energy conversion through deep borehole heat exchanger systems: Heat storage analysis and assessment of threshold inlet temperature. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 294, 117589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krusemark, M.; Seib, L.; Ohagen, M.; Welsch, B.; Pham, H.T.; Sass, I. Impact of borehole path deviations on the efficiency of a medium-deep geothermal storage system: Case study of the SKEWS MD-BTES Demosite. J. Energy Storage 2025, 125, 116959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Yu, M.; Liu, J.; Cui, P.; Zhang, W.; Mao, Y.; Zhuang, Z. Influence of heat storage on performance of multi-borehole mid-deep borehole heat exchangers. J. Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.A.; Blum, P.; Bayer, P. Influence of spatially variable ground heat flux on closed-loop geothermal systems: Line source model with nonhomogeneous Cauchy-type top boundary conditions. Appl. Energy 2016, 180, 572–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, P.; Yu, M. Investigation on the heat transfer characteristics of the U-tube and the coaxial tube medium-shallow borehole heat exchangers. Renew. Energy 2025, 248, 123145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolditz, O.; Bauer, S.; Bilke, L.; Böttcher, N.; Delfs, J.O.; Fischer, T.; Görke, U.J.; Kalbacher, T.; Kosakowski, G.; McDermott, C.I.; et al. OpenGeoSys: An open-source initiative for numerical simulation of thermo-hydro-mechanical/chemical (THM/C) processes in porous media. Environ. Earth Sci. 2012, 67, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Hein, P.; Sachse, A.; Kolditz, O. Geoenergy Modeling II: Shallow Geothermal Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Diersch, H.J.G.; Bauer, D.; Heidemann, W.; Rühaak, W.; Schätzl, P. Finite element modeling of borehole heat exchanger systems: Part 1. Fundamentals. Comput. Geosci. 2011, 37, 1122–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Witte, F.; Kolditz, O.; Shao, H. Shifted thermal extraction rates in large Borehole Heat Exchanger array—A numerical experiment. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 167, 114750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Gao, P.; Song, R.; Linyou, Z.; Xiaoyin, T.; Fang, H.; Ping, Z.; Zhonghe, P.; Lijuan, H.; Shengbiao, H.; et al. Compilation of heat flow data in the continental area of China (4th edition). Chin. J. Geophys. 2016, 59, 2892–2910. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Mu, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, K.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y. Geothermal field division and its geological influencing factors in Guanzhong basin. Geol. China 2017, 44, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Wang, F.; Chen, S.; Chen, C.; Liu, J.; Deng, J.; Kolditz, O.; Shao, H. Analysis of heat extraction performance and long-term sustainability for multiple deep borehole heat exchanger array: A project-based study. Appl. Energy 2021, 289, 116590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Shao, H.; Naumov, D.; Kong, Y.; Tu, K.; Kolditz, O. Numerical investigation on the performance, sustainability, and efficiency of the deep borehole heat exchanger system for building heating. Geotherm. Energy 2019, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Wang, F.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Z. Experimental and numerical investigation of heat transfer performance and sustainability of deep borehole heat exchangers coupled with ground source heat pump systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 149, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Ren, J.; Sun, H.; Du, S.; Wen, H. Heating and storage of medium-deep borehole heat exchangers: Analysis of operational characteristics via an optimized analytical solution model. J. Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Chen, R.; Guan, S.; Li, W.-T.; Yuen, C. BuildingGym: An open-source toolbox for AI-based building energy management using reinforcement learning. Build. Simul. 2025, 18, 1909–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karouei, S.H.H.; Abbas, W.N.; Ali, M.; Nayyef, D.R.; Hussein, K.K.A.; Hammoodi, K.A.; Azizi, S.S.H. Numerical investigation of the effects of geometric and fluid parameters on the thermal performance of a double -tube spiral heat exchanger with a conical turbulator. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 65, 105613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).