1. Introduction

Under the guidance of China’s “Dual Carbon” strategy (carbon peak and carbon neutrality), building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPVs) have emerged as a critical pathway for facilitating the low-carbon transformation of the building sector. At the policy level, explicit targets have been set to achieve a 50% coverage rate of photovoltaic systems on the roofs of new public buildings and factory buildings by 2025, alongside the encouragement of maximizing installations on existing building roofs wherever feasible. Concurrently, the technical standard system related to BIPV continues to be refined, with numerous regions promoting its large-scale implementation through technical guidelines, pilot projects, and financial subsidies. Driven by the synergistic effects of policy, standardization, and practical application, BIPV is rapidly evolving from a forward-looking technology into a key solution for constructing low-carbon cities and advancing the transformation of the energy structure.

Among the application forms of building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPVs), façade integration primarily encompasses three major categories: photovoltaic curtain walls, photovoltaic windows, and photovoltaic shading systems, each achieving synergistic optimization of energy generation and building performance at distinct levels [

1]. Among these, research on photovoltaic curtain walls predominantly focuses on the comprehensive effects of panel orientation, tilt angle, and cavity structure on both building heat transfer and power generation performance [

2]. For instance, Liu et al. [

3] proposed a novel symmetrical pentahedral photovoltaic curtain wall, composed of a vertical façade, upper and lower inclined surfaces, and two side surfaces. By optimizing structural parameters such as the opening angle of the upper inclined surface, the convex horizontal side length ratio, and the extension length, they significantly enhanced the power generation efficiency per unit area. Compared to traditional vertical BIPV curtain walls, this design demonstrates significant improvement in annual power generation across different orientations, with the most pronounced enhancement reaching 104% in the west-facing scenario. Research on photovoltaic windows primarily focuses on the performance of various semi-transparent photovoltaic materials in regulating indoor daylighting and reducing cooling loads, thereby balancing visual comfort with energy-saving potential [

4]. For instance, Li et al. [

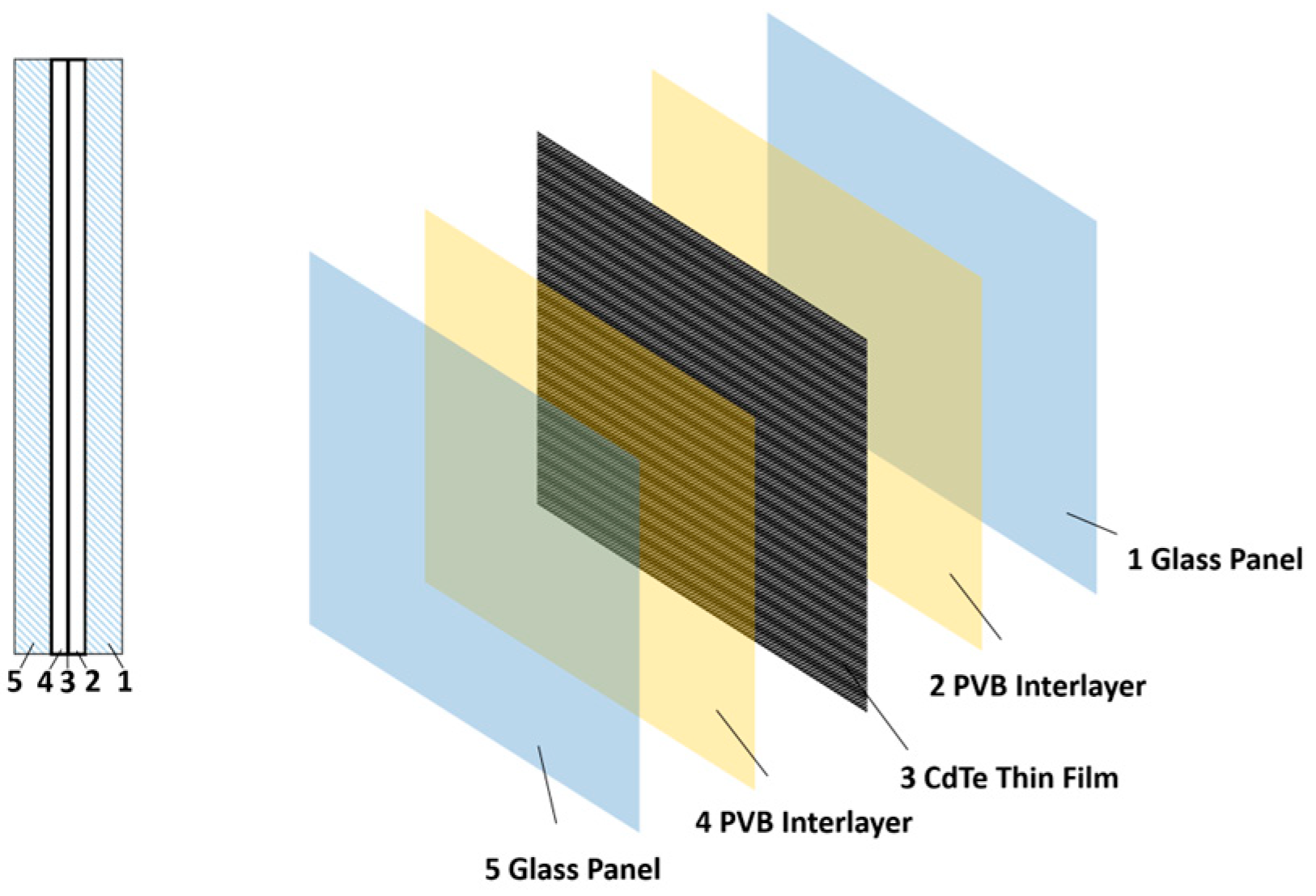

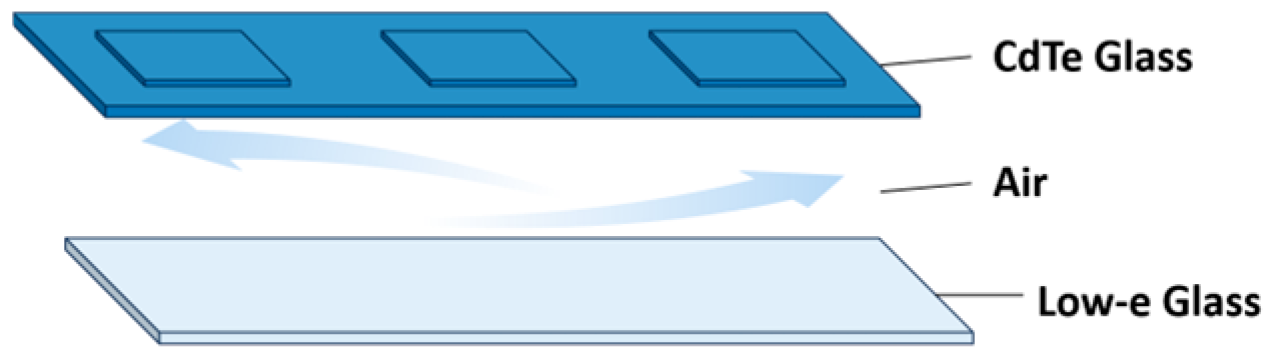

5] proposed a novel photovoltaic energy-saving window (PEW), composed of laterally slidable CdTe photovoltaic glass, a retractable polyurethane insulation shade in the middle, and an inner layer of double-pane transparent glass. Their investigation into the influence of parameters such as the number of transparent glass layers, thickness of the insulation shutter, number of photovoltaic glass layers, and light transmittance on building heating load revealed that the PEW reduced the annual heating load by 23.54% compared to double-pane transparent glass and by 15.42% compared to triple-pane transparent glass. Photovoltaic shading systems, through geometric optimization and dynamic control, enhance photovoltaic efficiency while fulfilling their shading function and improving the indoor photothermal environment [

6]. For example, Ye et al. [

7] integrated photovoltaic modules into building shading structures, enabling on-site power generation while blocking excessive sunlight. Utilizing a GIS-based spatiotemporal analysis and multi-objective optimization method, their study achieved a 57.40% increase in daily power generation efficiency per unit area compared to static horizontal installation. In summary, current research has independently advanced various BIPV technologies from the perspectives of structural design, material performance, and system control. However, the deep integration between photovoltaic systems and passive building energy-saving design has not yet been fully realized. Integrated modeling and the synergistic optimization mechanism for multiple performance aspects remain areas requiring further exploration.

In research on the performance optimization design of BIPV systems, existing studies have extensively elucidated the coupling mechanisms between photovoltaic design and the building’s physical environment. Specifically, current research focuses on systematically analyzing how key parameters—such as the arrangement of photovoltaic panels as building envelopes, shading coefficients, and light transmittance—comprehensively influence building thermal performance in both winter (insulation) and summer (heat mitigation), and consequently affect visual comfort indicators, including indoor illuminance and glare probability [

8]. The core objective is to achieve multi-objective synergy and global optimization among building energy production, energy-saving benefits, and occupant comfort [

9]. For instance, Wijeratne et al. [

10] employed the NSGA-II multi-objective optimization algorithm to optimize both the life cycle cost and life cycle energy output of BIPV roof systems. Their approach identified optimal solutions for rooftop BIPV panels and skylight BIPV configurations, streamlining the process of identifying economically viable and highly efficient design solutions during the early project stages. Chen et al. [

11] integrated transfer learning, the NSGA-III genetic algorithm, and CFD simulations into a multi-objective optimization framework to enhance multidimensional performance of photovoltaic façades in educational buildings, including carbon emissions, power generation, indoor lighting, and thermal comfort. Their optimal solution achieved a reduction in carbon emissions of 27.5 kgCO

2/m

2. Sadatifar et al. [

12] applied a Monte Carlo-based stochastic optimization method to iteratively optimize three key parameters of photovoltaic shading panels—tilt angle, length, and quantity—across five climate zones and two building types. This approach realized synergistic optimization of “power generation–energy saving–comfort,” providing a feasible pathway for the customized design of BIPV systems in diverse contexts. Bakmohammadi et al. [

13] integrated a deep learning model for façade segmentation with a multi-objective optimization algorithm to optimize three sustainability dimensions of building-integrated photovoltaic façades: energy self-sufficiency rate, economic payback period, and life cycle greenhouse gas emission rate. Their results demonstrated that the optimal solution under balanced weighting could achieve an electricity self-sufficiency rate of 5% to 7%. It should be noted, however, that with the emergence of new technologies such as grid-interactive functionalities, indicators such as energy flexibility must also be incorporated during the design phase, as they significantly influence the system’s grid interaction capability in actual operation. The aforementioned study, along with others, lacks comprehensive consideration of integrated factors including power generation capacity, carbon emissions, and energy flexibility. Nevertheless, with the rise of grid-interactive technologies and other innovations, the role of BIPV systems is evolving from that of a passive energy producer to an active grid supporter and flexible resource [

14]. This shift necessitates the proactive inclusion of emerging performance metrics, such as energy flexibility, already at the design stage, since early design decisions directly determine the system’s future grid interaction capability and carbon reduction potential in real-world operation [

15]. However, existing research predominantly focuses on balancing thermal and visual comfort performance, and still lacks a comprehensive design framework capable of coordinating multiple objectives such as power generation capacity, life cycle carbon emissions, and energy flexibility. This research gap substantially limits the potential of BIPV systems to maximize their role in achieving building-grid synergy and fulfilling the “Dual Carbon” goals.

In current research on performance simulation and uncertainty analysis of building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPVs), meteorological parameter uncertainty has garnered significant attention; however, predominant evaluation methodologies exhibit notable limitations. Most existing approaches rely on typical meteorological year (TMY) data or “typical day” sequences derived from historical weather data, which primarily capture short-term meteorological variations (e.g., hourly, daily, weekly, or seasonal fluctuations) but systematically fail to incorporate the annual weather changes driven by global warming [

16]. For instance, Wang et al. [

17] utilized TMY data to conduct annual hourly simulations, performing a comparative analysis of three BIPV systems—photovoltaic roofs, photovoltaic windows, and photovoltaic shading—to evaluate their energy performance and load-matching characteristics across different climate zones. Tang et al. [

18] employed TMY data incorporating urban heat island effects, combined with a three-dimensional local climate zone (LCZ) model and machine learning techniques, to assess the annual power generation potential of urban rooftop and façade BIPV systems and quantify the nonlinear relationships between urban morphological factors, climatic conditions, and system performance. Similarly, Xu et al. [

19] applied Hong Kong TMY data to analyze how geometric and color parameters affect the power generation efficiency and total output in a composite solar façade system comprising photovoltaic walls and shading elements. Their results demonstrated that photovoltaic shading achieves higher generation efficiency than photovoltaic walls under more favorable solar incidence angles. Zou et al. [

20] developed a novel dynamic vertical building-integrated photovoltaic envelope system, which adaptively adjusts slat angles and louver positions to simultaneously optimize power generation, daylighting, and thermal load regulation. Using typical seasonal day and annual meteorological data for Beijing in their simulation analysis, the study demonstrated that this dynamic configuration could increase the annual net energy output by at least 226% compared to conventional static photovoltaic shading systems. However, this prevalent neglect of long-term climatic dynamics directly compromises the accuracy of life cycle performance assessments and operational effectiveness of BIPV systems. For instance, Wang et al. [

21] highlighted through a coupled analytical framework that climate change-induced extreme events—such as prolonged periods of low wind and solar availability—significantly elevate levelized electricity costs and power supply demand imbalance risks. If such year-to-year changing factors are not considered during the design phase, BIPV design strategies will lack foresight, thereby undermining their long-term climate adaptability and operational reliability. In summary, prevailing uncertainty assessments for BIPV systems remain largely confined to short-term meteorological fluctuations and static climate assumptions. To enhance the resilience of BIPV buildings in future warming environments, it is imperative to integrate climate scenario data reflecting long-term trends into performance simulations and to establish a new uncertainty assessment framework that incorporates interannual temporal analysis. Such advancements are essential to support the low-carbon, robust operation and sustainable adaptation of BIPV systems over their full life cycle.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Input Parameter Correlation Analysis

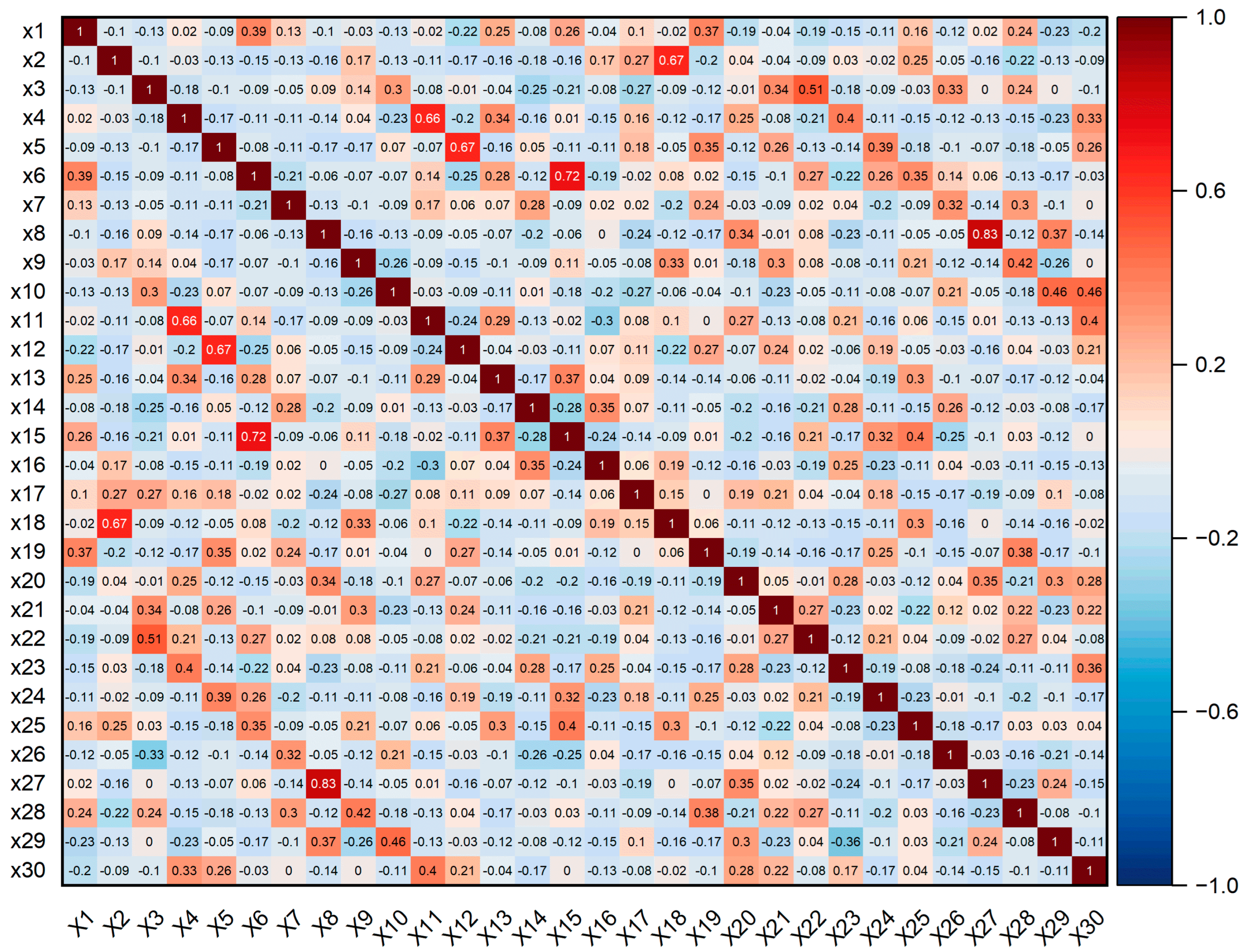

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 present the correlation analysis results among input variables under Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) and random sampling conditions, respectively. Comprehensive analysis demonstrates that LHS significantly outperforms random sampling in controlling inter-variable correlations, rendering it more suitable for subsequent global sensitivity analysis.

Specifically, under Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) conditions (

Figure 13), the Pearson correlation coefficients between input variables predominantly range from −0.17 to 0.15, with all absolute coefficient values remaining below 0.2. These results indicate only negligible correlations among variables, essentially satisfying the independence assumption required for global sensitivity analysis. In contrast, under random sampling conditions (

Figure 14), the correlation coefficients demonstrate a wider distribution, primarily spanning −0.2 to 0.4, with several notably elevated coefficients observed. These substantial correlations reveal that random sampling fails to effectively control inter-variable dependencies, and its inherent correlation structure may potentially interfere with subsequent sensitivity analysis, even leading to misinterpretation of parameter influences.

In summary, Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) effectively suppresses spurious correlations introduced by the sampling process, ensuring fundamental independence among variables and thereby establishing a more reliable data foundation for sensitivity analysis. Consequently, subsequent analyses in this study will primarily utilize LHS-generated data to ensure the robustness and reliability of conclusions.

In summary, this study employs Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to control inter-variable correlations, a method selected based on its established authority in the field of uncertainty analysis. The seminal work of McKay et al. [

43] clearly indicates that LHS outperforms simple random sampling in terms of covering the input variable space and ensuring the statistical properties of outputs. The computational results of this study (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14) validate the effectiveness of this method in the current context, as it effectively suppresses spurious correlations introduced by the sampling process, ensures fundamental independence among variables, and provides a more reliable data foundation for sensitivity analysis. Therefore, all subsequent analyses are based on LHS-sampled data to ensure the robustness and reliability of the research conclusions.

3.2. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis Results

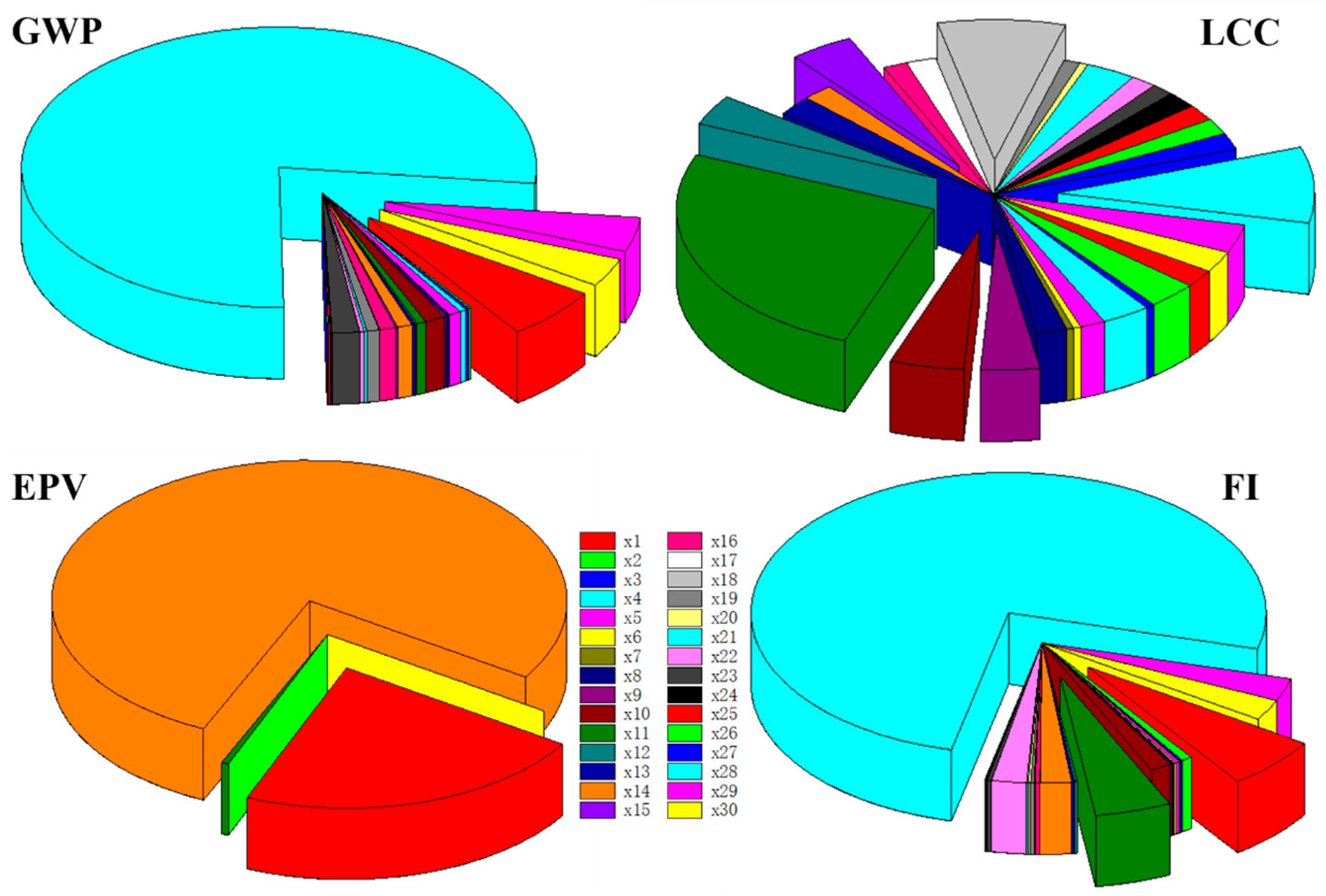

Based on the Sobol sensitivity analysis method, first-order sensitivity indices measure the independent contribution of individual input variables to the variance of the output, reflecting their isolated impact on the model output. In contrast, total-order indices comprehensively account for the interactions between the variable and others, capturing its overall influence on the system output under coupled conditions. This study systematically presents the specific numerical results of the first-order and total-order indices for each variable in

Appendix A.2 and

Appendix A.3, respectively. Preliminary analysis reveals non-negligible interactions among the input variables, which cannot be fully captured by first-order indices alone. Relying solely on first-order indices may lead to an underestimation of variable influence. Therefore, this study primarily uses the total-order sensitivity index as the basis for determining variable significance. Regarding the determination of the significance threshold for total-order indices, traditional approaches often rely on subjective experience or predefined fixed criteria. To enhance objectivity, this study adopts the arithmetic mean of the absolute values of all variables’ total-order indices as the discrimination threshold. Variables exceeding this threshold are considered to have a significant impact on the output, while those below are deemed non-significant.

Based on the total-order sensitivity index contribution pie chart presented in

Figure 15, the following variables are identified as exerting significant influence on the comprehensive performance of building-integrated photovoltaics (including energy consumption, indoor comfort, and power generation benefits): X1 (building orientation), X9 (wall thermal absorptance), X10 (north window-to-wall ratio), X11 (south window-to-wall ratio), X12 (west window-to-wall ratio), X14 (photovoltaic shading angle), X15 (photovoltaic window visible transmittance), X18 (north window insulation level), X28 (equipment power density), X29 (lighting power density), and X30 (occupancy density). These parameters collectively demonstrate critical impacts on system behavior through complex intervariable interactions. In summary, employing Sobol total-order sensitivity analysis, this study not only identifies key parameters with predominant influence on building integrated performance under multivariate interaction scenarios, but also reveals potential mechanisms of synergistic or antagonistic effects among variables. These analytical outcomes provide crucial foundations for subsequent BIPV performance optimization, parameter adjustment strategies, and uncertainty management, thereby facilitating more precise resource allocation and system control during both design and operational phases.

Comparing the aforementioned sensitivity analysis results with existing studies reveals both shared patterns and distinct characteristics. Consistent with our finding that photovoltaic shading angle is a key parameter, Sadatifar et al. [

12] also identified it as one of the core variables for achieving the synergistic optimization of “power generation-energy saving-comfort” in their multi-objective research, which validates the effectiveness of our model in identifying such critical design parameters. However, whereas Chen et al. [

11] focused more on reducing carbon emissions through building form and envelope optimization, and Sadatifar et al. [

12] concentrated on balancing power generation, energy efficiency, and comfort, this study introduces an energy flexibility index to further reveal the significant impact of equipment and lighting power density on this emerging metric. This finding addresses the limitations of traditional analytical frameworks that primarily focus on building performance itself, providing more specific parametric guidance for grid-interactive BIPV building design.

3.3. Uncertain Impacts of Climate Change on BIPV Building Performance

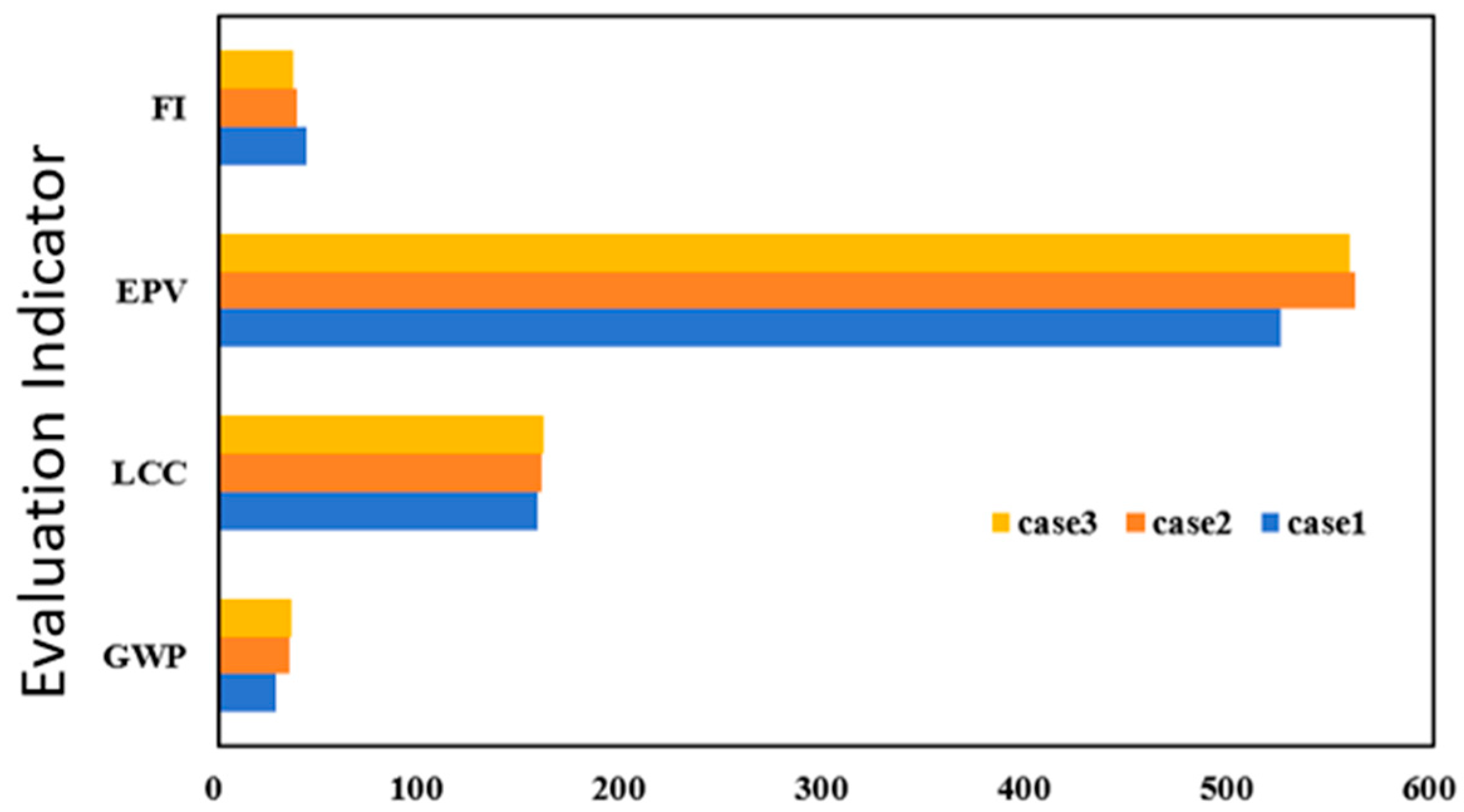

Through performance simulations of BIPV buildings under Case 1 (baseline scenario), Case 2 (2050s climate scenario), and Case 3 (2080s climate scenario), this study reveals the evolving trends of building performance under different future climate scenarios, considering global climate change impacts, as illustrated in

Figure 16. The results demonstrate that with intensifying climate change, both carbon emissions and life cycle costs of BIPV buildings show increasing trends, while energy flexibility gradually declines, indicating persistent challenges to overall building performance in the future. However, regarding power generation performance, due to variations in direct solar radiation conditions, BIPV buildings exhibit the highest generation potential during the mid-building life cycle (Case 2), suggesting possible enhancements in photovoltaic conversion efficiency during specific climate phases.

This study reveals the evolving patterns of BIPV performance under climate change, which aligns with existing research while highlighting the advantages of our methodology in long-term risk assessment. Similar to our finding that BIPV power generation potential increases under mid-term climate conditions due to changes in solar radiation, Tang et al. [

18] also emphasized the decisive influence of solar radiation conditions on the power generation potential of BIPV at the urban scale. However, many studies aimed at optimizing BIPV system performance, such as Xu et al.’s [

19] parametric analysis of high-rise residential buildings in Hong Kong, typically base their evaluations on static or historical climate conditions. While such studies can effectively assess system performance during specific periods, they fail to capture long-term climate evolution trends driven by global warming and the associated risks of extreme events. Wang et al.’s [

21] research on the increasing frequency of extreme windless and low-sunlight events and their impact on rising electricity costs directly warns of the systemic risks posed by ignoring year-to-year climate variations. In contrast, by incorporating future climate scenarios and an uncertainty analysis framework, this study quantifies the potential deviations in performance indicators over the long term, providing a more forward-looking perspective for evaluating the robustness and climate adaptability of BIPV systems throughout their life cycle.

Collectively, although climate change adversely affects building energy consumption, carbon emissions, and economic performance, photovoltaic technology demonstrates potential for more efficient energy harvesting under certain future climate conditions. Therefore, actively advancing photovoltaic technology applications and promoting widespread BIPV implementation will represent crucial development pathways for addressing climate challenges and facilitating building decarbonization transitions.

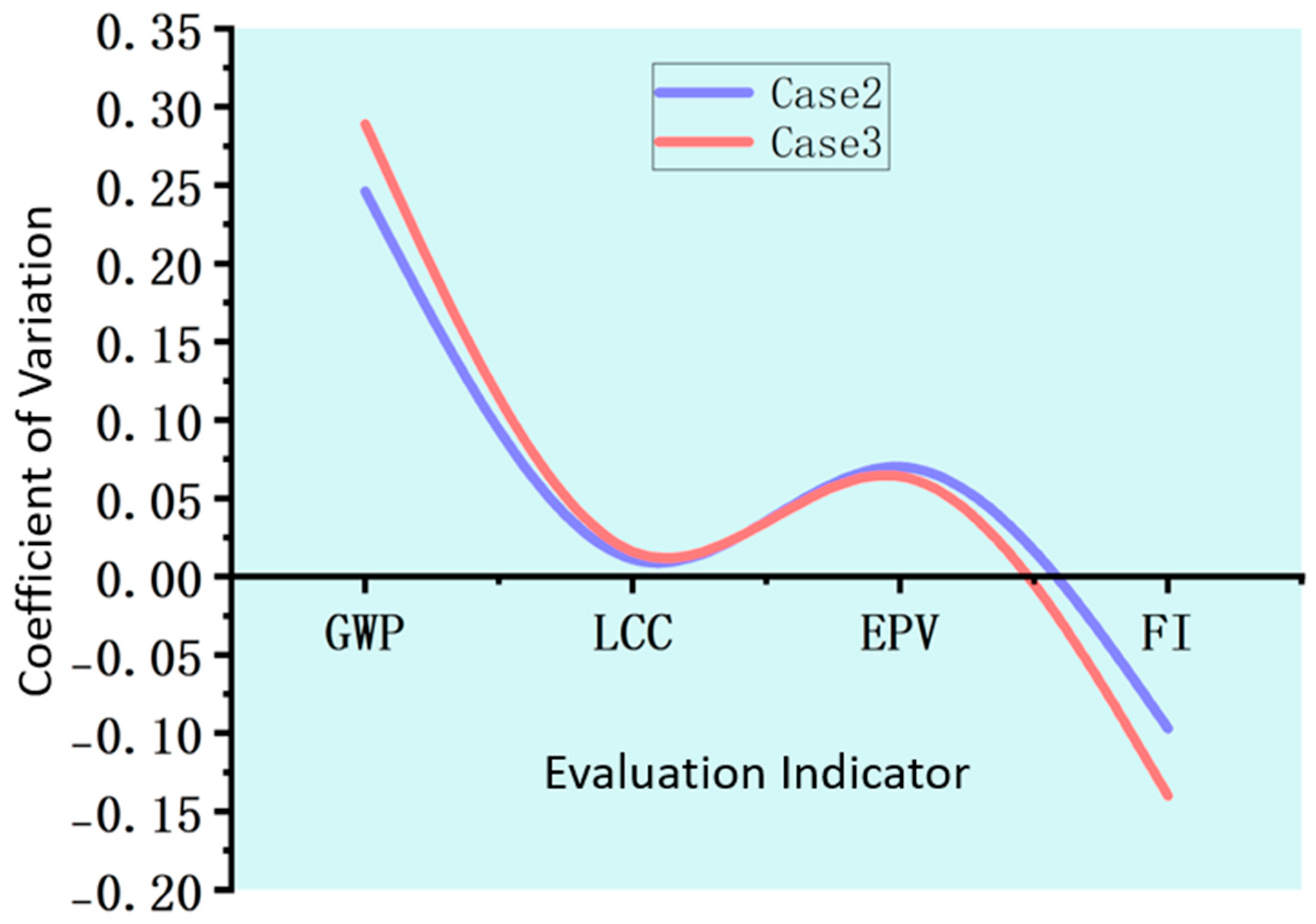

Figure 17 and

Table 14 present robustness evaluation indicators for different future scenarios considering climate change. The results indicate that the building sector in future high-renewable energy power systems will face significant climate adaptation challenges. Key metrics, including carbon emission intensity and energy flexibility, exhibit substantial fluctuations across different climate pathways, reflecting their high sensitivity and exposure to climate change. These findings further reveal the particularly pronounced impact of climate constraints on the carbon footprint during building operational phases.

To address these challenges, the following pathways should be actively promoted. At the technical level, climate-responsive design strategies should be integrated, including enhanced thermal inertia of building envelopes, adoption of adjustable shading and natural ventilation systems, and development of integrated photovoltaic–storage–direct current–flexibility (PSDF) energy systems. At the policy level, building carbon accounting methodologies and low-carbon performance incentive mechanisms should be refined to shift the focus from “energy consumption control” to “carbon emission management.” At the system coordination level, leveraging smart grid technologies and demand-side response mechanisms should expand buildings’ potential as flexible loads, transforming them from mere energy consumers into proactive “prosumers.”

In conclusion, climate adaptation must be deeply integrated throughout the entire building design and operational life cycle. Through systematic innovation in technology, policy, and mechanisms, the climate resilience of the building sector can be effectively enhanced, achieving synergistic advancement of green low-carbon transition and systemic security.

3.4. Life Cycle Economic and Reliability Analysis

Based on the aforementioned life cycle cost (LCC) model and cost parameter analysis, the impact of climate change on the economic sustainability of BIPV buildings cannot be overlooked. Simulation results (see

Figure 17) indicate that as climate change intensifies, the life cycle cost of BIPV buildings shows a significant upward trend: Case 2 (2050s) increases by 1.1% compared to the baseline scenario, while Case 3 (2080s) rises further to 1.6%. This cost escalation primarily stems from three factors: increased cooling energy costs due to prolonged air conditioning operation caused by rising temperatures, higher maintenance costs resulting from accelerated equipment aging due to frequent extreme weather events, and efficiency degradation caused by the accelerated performance decline of photovoltaic materials in high-temperature environments.

The long-term maintenance and reliability of BIPV systems are crucial to ensuring their economic sustainability. According to the operational and maintenance cost data in

Table 11, the annual maintenance cost of the photovoltaic system is 21,898 ¥, and the inverter replacement cost is 3120.5 ¥ per year. In the context of climate change, these costs may increase significantly. Extreme high temperatures can accelerate the aging of component materials, frequent extreme weather events may raise the risk of physical damage, and temperature fluctuations can affect the stability of electronic equipment—all of which pose challenges to the long-term reliability of the system. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a preventive maintenance system and select equipment with stronger climate adaptability to enhance system reliability.

Beyond techno-economic factors, the widespread adoption of BIPV technology faces multiple challenges in architectural design and regulatory constraints. From an architectural design perspective, integrating photovoltaic facades, shading systems, and windows requires balancing aesthetics, structural safety, and energy efficiency. Building codes impose technical requirements for fire prevention, waterproofing, and structural strength, which limit the design flexibility of BIPV systems. On the policy and regulatory front, although the national government has set a target for photovoltaic coverage in new buildings by 2025, local implementation rules and standards remain underdeveloped. This is particularly evident in the lack of unified technical standards and approval guidelines for BIPV retrofitting in existing buildings. Furthermore, ambiguities in grid connection policies—such as technical requirements for integration, feed-in tariff subsidies, and electricity trading mechanisms—increase policy-related investment risks for projects.

Finally, from a broader environmental sustainability perspective, while this study primarily focuses on carbon emissions during the operational phase, a comprehensive assessment of BIPV’s environmental benefits requires consideration of its cumulative environmental impacts throughout the entire life cycle. The manufacturing process of photovoltaic components involves high energy consumption and certain carbon emissions. Although power generation during the operational phase can offset these emissions, it takes a longer time to achieve true carbon neutrality. Additionally, the rare metals and toxic substances contained in the components may cause pollution during disposal, necessitating the establishment of a robust recycling system. Future research should develop more comprehensive life cycle assessment models for BIPV to provide a scientific basis for technology selection and policy formulation.

4. Conclusions

Building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPVs), as a pivotal technology for enhancing renewable energy utilization in buildings, currently face challenges, including the lack of integrated design models, unidimensional performance analysis, and insufficient consideration of climate change factors. To address these limitations, this study proposes a comprehensive performance analysis methodology for BIPV systems that incorporates global climate change impacts. The methodology is developed through four key components: (1) establishing an integrated BIPV simulation model for photovoltaic curtain walls, shading systems, and roofs by coupling EnergyPlus, Optics6, and WINDOW 7.7; (2) constructing a comprehensive performance evaluation framework encompassing four dimensions: global warming potential (GWP) of carbon emissions, electricity generation, energy flexibility, and economic costs; (3) generating hourly meteorological data under future climate scenarios, covering both mid-term (2050s) and long-term (2080s) building life cycle stages using the CCWorldWeatherGen tool; and (4) implementing Monte Carlo simulations to generate comprehensive BIPV performance datasets across variable combinations, followed by sensitivity and uncertainty analyses to identify key influencing factors and quantify climate change impacts on various performance indicators. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

The sensitivity analysis of design parameters reveals that variables exerting significant influence on the comprehensive performance of building-integrated photovoltaics (including energy consumption, indoor comfort, and power generation benefits) include: building orientation, wall thermal absorptance, north window-to-wall ratio, south window-to-wall ratio, west window-to-wall ratio, photovoltaic shading angle, photovoltaic window visible transmittance, north window insulation level, equipment power density, lighting power density, and occupancy density. Specifically, equipment power density and lighting power density demonstrate the most pronounced combined effects on carbon emissions and flexibility index. Variations in building envelope thermal performance exhibit greater impact on life cycle costs than on carbon emissions. Photovoltaic shading shows more responsive power generation performance compared to photovoltaic curtain walls and windows. Furthermore, the east wall insulation level, photovoltaic window visible transmittance, and solar heat gain coefficient present non-negligible influences on building economic costs.

The uncertainty analysis of climate change impacts demonstrates that with intensifying climate change, both carbon emissions and life cycle costs progressively increase while energy flexibility continuously declines, indicating sustained pressure on overall system performance. However, under specific mid-term climate conditions, BIPV systems exhibit enhanced power generation potential due to altered solar radiation patterns, suggesting possible improvements in photovoltaic energy conversion efficiency in future scenarios. To address climate challenges, it is imperative to integrate climate-adaptive design strategies with advanced energy systems such as integrated photovoltaics–storage-direct current–flexibility (PSDF) configurations, while simultaneously promoting policy mechanism transformations. Consequently, actively advancing BIPV technology implementation and embedding climate resilience throughout the building life cycle represent crucial pathways for achieving building decarbonization and enhancing systemic climate adaptation capacity.

The study has limitations: its methodology relies on static assumptions and struggles to capture real-world dynamics, while its data and case studies are context-specific, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Future work should integrate dynamic simulations and diverse data to validate the framework, alongside exploring the integration of smart technologies to enhance the adaptability of BIPV design.