Abstract

Despite regulatory advances, there continues to be a high accident rate on construction sites, especially on road projects, mainly due to the lack of organization of safety information. Although there is research demonstrating the benefits of the BIM methodology for improving occupational safety, its scope is still limited. This study addresses the integration of occupational health and safety in road projects using the BIM methodology, in line with ISO 19650-1, proposing a standardization framework based on ISO 7817-1:2024. The concept of Level of Information for Safety and Health (LOINSH) is introduced, structured into four categories (100, 200, 300, and 350), which allows risks to be managed progressively throughout the project’s life cycle. The framework defines graphical and alphanumeric requirements for BIM objects, establishing sets of parameters recognized by the open IFC format to ensure interoperability and traceability. It also proposes a system for assessing risks associated with activities and disciplines, facilitating preventive decisions from the design stage onwards. The results indicate that this standardization improves communication and collaboration between agents, reduces workplace accidents, and can be applied to other types of construction works.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the construction sector continues to be affected by high accident rates [1]. Thus, in the last decade, fatal accidents in construction have exceeded between three and six times those in other sectors [2,3]. In 2023, U.S. construction recorded the highest number of fatalities among industrial sectors (1075), the highest in the sector since 2011 [4]. In 2024 in the European Union, 22.9% of fatal occupational accidents in 2022 occurred in construction [5].

The particularities of construction activities contribute to the existence of many risks that are difficult to classify and predict, giving rise to a more complex risk identification process than in other industries [6]. In this sense, research to improve occupational risk prevention contributes to the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2030, in particular, SDG3 “Good Health and Well-being” and SDG8 “Decent Work and Economic Growth” [7].

The research by Liu et al. [8] about patterns in construction accidents in China found that the key factors that cause most incidents are the implementation of an inadequate occupational health management system or its ineffective implementation, the omission or lack of safety information that is not assimilated by workers, as well as psychological and physiological factors, such as absent-mindedness or disobedience to safety regulations, which are usually fatal. Buniya et al. [9] find other major barriers to the implementation of construction safety programmes in Iraq, such as a lack of commitment, inefficient safety training, a non-conductive work environment with a clear lack of collaboration among workers, and a lack of awareness of the dangers of construction site work.

Thus, some of the factors highlighted in recent years that reduce safety are the problems of coordination of safety technicians [10], the lack of technological innovation, and the scarce use of digital technologies to improve safety [11,12], the lack of standardization and resistance to change by the agents involved in the project [13], the lack of innovative strategies for the application of safety by institutions [14], the availability of contradictory, confusing, and disorganized information and security protocols [15], technological limitations that prevent the application of new digital tools [16], and a low level of awareness from workers about safety [17], with a consequent lack of commitment, motivation, and responsibility to apply risk prevention protocols [18].

Based on these factors, Sarvari et al. [19] conclude that the construction sector needs to adopt a more integrated approach to risk management that emphasizes cooperation between actors and the improvement of information and safety flows through the development and implementation of protocols employing digital technologies. This change can facilitate better coordination between all parties involved, as well as better information traceability, enabling a more cohesive and proactive security management strategy that addresses industry-specific risks.

Within this sector, road construction, due to its linear nature, presents particularities that require a differentiated analysis of the construction of buildings and other infrastructures. For example, they are at risk of fatal or serious injury when working near motorists, construction vehicles, and heavy equipment or machinery [20]. In particular, unfavourable working area conditions, atmospheric agents, and a lack of organized risk and safety information, as well as poor prevention training act as key risk factors in road construction [21]. Carelessness and the carefree attitude of workers, as well as habituation to safety and warning signs, also make up other conditioning factors that result in an increase in accident rates in this field of work [22].

In addition, in road projects, the possible presence of vehicle and pedestrian traffic and the vehicles used in construction in the vicinity of the works are critical external factors that aggravate the risks inherent in the construction of these infrastructures [23]. The complex interaction of these internal and external factors creates situations that are difficult to manage and often culminate in accidents [24], the consequences of which are suffered by workers, especially affecting machinery operators and construction labourers [25].

In addition, the presence of special risks requires a specific safety analysis [26,27]. Despite the recent literature on proposals for improving safety in road construction [21,23,28,29], accident statistics require further research. Moreover, the prevention of accidents at work on construction sites requires a high degree of specificity, both because of the nature of the risks involved and because of the temporary nature of the work [30].

During the road design phase, the health and safety of the life cycle of the asset must be taken into account following the principle of prevention through design (PtD, hereinafter), which includes the analysis of safety conditions, the identification of risks, and the provision of preventive measures and signage [31], resulting in a reduction in the accident rate during the subsequent phases [32]. Therefore, all the information on the construction process must be available from this initial phase of the project in a standardized and correctly organized way [33]. Despite its benefits, construction faces challenges when it comes to effectively applying PtD, such as ignorance and a lack of confidence in the results obtained, fear of a considerable increase in cost and time, and a lack of standardization of methodologies and application cases where this technique is used [34].

On the other hand, the construction sector is immersed in a digitalization process known as Construction 4.0, through which several technologies are integrated into production processes [35]. This represents a paradigm shift in all disciplines involved in construction projects, including health and safety management, which will require new methods of evaluation and analysis of this information [36]. In this sense, the enabling tool of Construction 4.0 is the BIM methodology (Building Information Modelling), considered to be the technology with the greatest potential to improve current health and safety results, allowing the interconnection of other digital technologies [37].

BIM already has an increasing application in road projects [38], which has led the European Union to allow member states to require this methodology in public tenders [39]. This is due to its proven benefits for the design and construction of infrastructures, especially roads, and the improvement of coordination between the agents involved through streamlined communication, allowing for the traceability of information [40]. In addition, through BIM, the final conditions of the project can be anticipated accurately, such as being able to apply a preventive strategy from the design, which is more economical and technically feasible than applying corrective measures in situ later [41].

Thus, the evaluation of the health and safety of construction projects is included within the eighth dimension of BIM [42]. In this sense, construction professionals recognize the benefits of BIM for improving risk detection and task planning through 3D visualization [43], resulting in higher quality proactive prevention [44]. Other strengths are also highlighted, such as the identification of high-risk tasks [31]; the detection of potentially dangerous areas [45]; the automated generation of protocols for the identification and action against risk scenarios [43]; and the improvement of the flow of communication between agents through the traceability of safety information [46], along with benefits for the awareness and training of workers in risk prevention [47]. The BIM methodology also enables the automated assessment of risk levels on site for the provision of preventive measures from the design phase [48,49], as well as the preventive management of safety data during the operation of infrastructures [50,51]. These benefits of BIM have already been proven in little research where this technology is applied for safety management in road projects, which today is still a field of very limited extension. The advantages of BIM have been verified both to analyze the risk due to contact between power lines and machinery used during the construction of road works [52] and to carry out automated risk assessments on these infrastructures during their different phases of construction [28].

However, these investigations cover specific cases and conditions, so it is essential to establish a well-organized structure of safety information covering the potential risks in road projects, which can be incorporated into BIM models and managed in an open format using the Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) [53]. Its development has been slower in the case of infrastructures than buildings. Thus, the IFC2x3 standard (ISO 16739-1:2024) [54] covered only buildings (architecture, structure, MEP, and planning and management of facilities), and it is not until IFC4.3 (ISO 16739-1:2024) [54] that it covers both buildings and infrastructures.

Given the need to establish a structure for this information in BIM, the ISO 19650-1 [55], introduces the concept of the Level of Necessary Information, or LOIN, considered as an essential concept for the successful implementation of BIM [56]. This LOIN is established as a methodological framework to define the quality, quantity, and granularity of the information required at any point in the life cycle of an asset in order to ensure the uniqueness of the data and the availability of the information required and that is indispensable for its management [57]. This directive defines LOIN as the result of the interaction of three components: Geometric Information (LOG), of a visual nature and represented on the model itself; Alphanumeric Information (LOI), of a parametric nature and embedded as intrinsic information within each of the BIM objects; and Associated Documentation (DOC), such as links to documentation that is outside the BIM environment database. In this way, this regulation defines the framework of the LOIN under four requirements that must be met: (1) the purpose, the reason for the data; (2) the delivery milestone, when; (3) the agent responsible for this information; and (4) the object to which it applies. With the response to these criteria, the agents involved in the project are responsible for justifying the existence of each piece of information, thus avoiding the overrepresentation of information and problems of duplication [58].

Given the complexity of the LOIN concept, the ISO 7817-1 (July 2024) [57] was developed. It re-codes the concepts and principles; therefore, it is very general to be valid for the information of any element of a construction, from a door to a tunnel. Part 2: ISO/AWI TS 7817-2 [59], which will define how to break down the information requirements according to the LOIN concept based on the purpose of use and the life cycle phase (design, construction, operation, and maintenance), is in early development. This standard will focus on the definition, structuring and validation of the information requirements within the BIM process, and the relationship between the level of information needed and the IFC. This highlights an important gap in this field.

Therefore, the supervision of the quality of project information through the management of LOIN is a dynamic, progressive, and adaptive activity to the changes that occur in the life cycle, so those responsible must enrich the LOIN of the BIM objects as the project phases progress, ensuring that only the necessary information is available at each stage [60]. However, the information from the different elements of the model will not evolve in the same way, since the LOIN is intrinsically linked to the purpose of the information [57].

Thus, to supervise compliance with these LOIN requirements, there is a process of reviewing deliverables, which is currently carried out manually, requiring excessive consumption of time and energy [61]. Consequently, the verification of information quality using automatic validation using machine-readable requirements is essential [62].

Due to the recent publication of the LOIN regulation, there is hardly any literature in which an organized LOIN structure is established to be integrated into BIM models. From a search in WoS, with the terms LOIN (Topic) and BIM (Topic), ten results appear. Only two of them mention the need to establish a LOIN structure for safety information in construction projects. Salzano et al. [63] define, as one of their objectives, the LOIN structure for the management of safety in the different phases of a building’s project, which involves determining the specific data necessary to manage and mitigate risks in each phase. However, they do not present any LOIN information proposal or any parameter structure. On the other hand, Pham et al. [64] establish the LOIN for a BIM-based digital twin solely for contamination risk management during building renovation. Thus, these investigations focus on buildings, leaving aside the rest of the infrastructures, in addition to not addressing any proposal to establish a general LOIN structure to manage all the risks generated during the construction of these infrastructures.

Thus, construction has very high accident rates despite regulatory efforts. It has been shown that the lack of organization of information, deficiencies in its traceability, or difficulties in collaboration and communication between those involved are factors that increase the accident rate in road construction works.

The BIM methodology has been shown to have benefits for the accident rate of workers, the nature of which makes it suitable for the application of PtD. However, despite the increasing number of road projects carried out in BIM, there are few projects where the integration of safety in BIM is realized.

For the successful implementation of the BIM methodology, the correct implementation of the LOIN is essential. For this purpose, there are two basic international standards: ISO 19650-1 [55] and ISO 7817-1:2024 [57]. However, the latter includes principles and concepts that make its application really complex, which is why the development of Part 2 of the standard is being initiated. On the other hand, the normative development of BIM standardization shows that it will take many years to develop the infrastructure-related aspects. In addition, the standardization of safety and health in BIM is scarce and insufficient.

Thus, it is demonstrated that there is a significant gap in the standardization of the level of health and safety information required in road projects carried out in BIM, depending on the nature of the activities, aligning with the need for specificity in the prevention of occupational risks in the construction sector. It is therefore considered to be a key factor impeding the adoption of BIM for health and safety and to be able to achieve its benefits.

Therefore, the aim of this research is to propose the level of information necessary for health and safety in road works which, based on the ISO 7817-1:2024 [57] standard, guarantees the quality and granularity of the information for the assessment of the usual risks in these projects in their design phase, for the usual agents and equipment, and which allows its relation with the IFC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Occupational Risk Assessment Methodology

The proposed standardization is based on the risk assessment methodology [27], whose application in BIM has already been validated [28,49]. It assigns values to the probability of occurrence (Prob_R0i) and the severity of the consequence (Sev_R0i) of the risk. This score can be 1, 2, or 3, from lowest to highest as the probability or severity increases. The level of risk is the result of multiplying the probability by the severity (Val_R0i = Prob_R0i × Sev_R0i). The risk reassessment shall be carried out after applying the following preventive measures, which is the same procedure depending on these factors: reassessed probability (Re_Prob_0i), reassessed severity (Re_Sev_0i), and reassessed risk assessment (Re_Val_0i). The colour coding of the risk levels in the BIM model is the one established by the Spanish Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (SIOSH) [27].

To carry out the above process graphically in the model, each BIM object will represent one or more work units: excavation, embankment, pavement, etc., depending on the risk analysis to be carried out. In addition, each work unit needs a series of activities to carry it out: stakeout, compaction, spreading the primer irrigation, etc., which will have associated risks: cuts, falls at the same level, noise, etc.

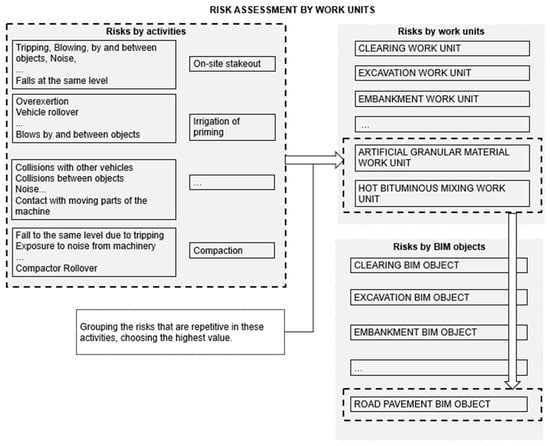

Consequently, each BIM object of a work unit must incorporate as non-graphic information (parameters) all the information of the risk assessment process of the activities necessary to execute it. If any of the risks exist in more than one activity, the one with the highest assessment will be taken to be on the side of safety (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Example diagram of association of the risks of the activities grouped by work units [65], with the elements of the project represented by BIM object.

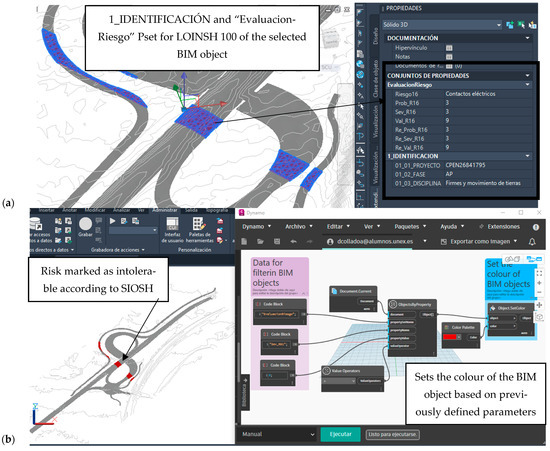

This parameterisation is automated by means of two codes created in Dynamo. The first one creates the parameters of Table 1 and associates them to the BIM objects starting from an Excel sheet in which the necessary information is defined according to the coding of the (SIOSH) [27]. The second shows the preliminary values of risks according to [65], structured in another Excel sheet, and enters them into the BIM objects according to the corresponding work unit. From this point, within the BIM model, the health and safety technician carries out the specific risk assessment according to the context of each activity and the area using tables or 3D views of the model.

Table 1.

Level of alphanumeric and documentary information associated with the LOINSH 100, 200, 300 and 350. Summary of the Pset established for this research.

2.2. Level of Information for Safety and Health (LOINSH)

The objective is to standardize the level of information necessary (LOIN) for health and safety in the design process of a road project using BIM. There will be a work team (or a role) in charge of analyzing health and safety based on the information coming from the rest of the work teams (pavements and earthworks, drainage, structures, etc.). This team will set the different levels of necessary safety information for each BIM object, called LOINSH (Level of Information Necessary for Safety and Health) in order to be able to carry out the analysis of the risk assessment of the road project depending on the type of risk to be analyzed and the stage of the project. The information will refer to certain geometric and analytical characteristics, either non-graphic or linked, such as links to documents related to the Health and Safety Study

In order to have sufficient and ascending granularity in the information, three levels are proposed, from the one that needs or has little information, LOINSH 100 (for example, in planning or informative study), a phase with more information available, LOINSH 200 (preliminary design), up to the complete information of the construction, LOINSH 300 (construction project), adding one more level for risks that require additional information in their analysis. The LOINSH is not associated with the phase, which implies that, in a preliminary project phase, due to the particularity of a risk, the health and safety technician can set a necessary requirement corresponding to a LOINSH 350.

The first two structure the information necessary for a preliminary design stage and the last two for the construction project. This can vary according to the requirements and nature of the project, and especially the requirements of the health and safety analysis, which is being used interchangeably in each of them.

Following the criteria of the BIM Manual of the Government of Catalunya [66], the accuracy of the BIM objects for health and safety will be schematic for the LOINSH 100, metric for LOINSH 200, and centimetric for LOINSH 300 and 350. In addition, the LOINSH 300 addresses the standard risk assessment information, and the LOINSH 350 deals with the special risks as indicated in the standard [27].

2.3. LOINSH 100

This LOINSH 100 will be applied when, due to the available information on the project or the risks to be assessed, a division into work units is not possible or necessary, either due to the lack of definition or because the risk affects large areas of the project. The level of information required will be as follows:

2.3.1. Graphical Information Level

- Level of detail: Determined by elements that have a conceptual geometry, with some division intended to mark a specific risk and that allows for the association of Alphanumeric Information.

- Dimensionality: BIM objects can be two-dimensional or three-dimensional, but in any case, they must allow for the association of parametric information.

- Location: They must be in absolute coordinates.

- Appearance: BIM objects must have a colour based on the result of the risk assessment and re-evaluation according to the SIOSH methodology to be able to visualize it graphically within the model. If this is not possible due to requirements because a single model with all the information is desired, the BIM object will maintain the colour of the corresponding material. Even so, having the associated parameters, it should be possible to make colour filters through any visualization programme.

- Parametric behaviour: The health and safety team will carry out a risk assessment on fixed information on the design of the road, so parametric behaviour is not necessary. If after the risk assessment it is necessary to make changes in the design, these must be made by the work team of the discipline involved.

2.3.2. Level of Alphanumeric Information

It must include the identification of the BIM object and the information of the associated risks. The first is structured in a group of parameters (Pset) recognizable by the BIM Open Standard (IFC) format to be able to identify the name of the project, the phase, and the discipline, called “1_IDENTIFICACION”, based on the BIM Manual of the Directorate-General for Mobility and Road Infrastructure of the Regional Government of Extremadura [67].

The associated information is also structured in the group of parameters “EvaluacionRiesgo”, which includes all the parameters to obtain the result of the evaluation and re-evaluation according to the methodology of the SIOSH [27]. The risk assessment values of the units can be based on known theoretical values extracted from documents such as the risk assessment guide of the Navarre Association of Public Works Companies (NAPWC) [65] or other reference bibliographic values. The parameters of these two Pset can be consulted in Table 1, where each of the parameters and their respective LOINSH are indicated.

2.3.3. Level of Documentary Information

The model must have the capacity to host a URL to link to the Technical Report and Regulations on Health and Safety of the Common Data Environment (CDE), which includes the preventive measures proposed based on the risks assessed. This can be consulted through the “Memoria” and “Normativa” parameter of the “DocumentosSeguridadSalud” Pset added to the BIM model globally, specified at the end of Table 1.

2.4. LOINSH 200

This LOINSH 200 will be applied when, due to the available information on the project or the risks to be assessed, granularity in complete work units is not necessary, and the risks may be grouped for sets of work units. The level of information required will be as follows:

2.4.1. Graphical Information Level

- Level of detail: Determined by BIM objects that represent the typology of the element in a generic way, with a level of metric precision. It is possible that the same BIM object encompasses several elements of the project. In particular, about the discipline of pavements and earthworks, the BIM object can be grouped into a basic section in which the same BIM object contains the different layers of the pavement and represents the finished level of the grading together with the cut slopes. It shall also be possible to divide the layout into sections along project axes or when there is a significant geometrical or constructional difference. It is not necessary to resolve road intersections with precision, but the coordination in plan and elevation must be maintained with the required precision. With regard to the disciplines of structures, drainage, and affected services, the BIM objects must be modelled with the external envelopes of their main elements with the precision required for this LOINSH.

- In the case of BIM objects in the discipline of health and safety, objects will be modelled that represent preventive measures (barriers, signage, etc.) with the precision required in this phase.

- Dimensionality: All elements that make up the disciplines must be three-dimensional in order to have a coordinated BIM object in plan and elevation to which the risk information results can be associated.

- Location and Appearance: The same as the LOINSH 100.

- Parametric Behaviour: The same as the LOINSH 100, with the difference that, in the case of the health and safety discipline itself, it is considered necessary to place preventive measures in an agile and effective manner.

2.4.2. Level of Alphanumeric Information

It must include the identification of the BIM object and the information of the associated risks. The identification parameter group is extended until all those considered in the “1_IDENTIFICACION” Pset (Table 1). With respect to the associated information, the “EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset is presented in Table 1. To start the risk assessment, theoretical values from guides such as the NAPWC [65] or other bibliographic values can be used, which will be reviewed according to the context information of each unit in the BIM model. The units modelled with this LOINSH will have associated the risks of the activities that compose them (Figure 1).

2.4.3. Level of Documentary Information

The same as for LOINSH 100.

2.5. LOINSH 300

This LOINSH will be used when the risk analysis requires complete granularity of the work units and the risks associated with them, as well as a level of centimetre detail, which allows for interference in the execution of activities to be analyzed.

2.5.1. Graphical Information Level

- Level of detail: Determined by objects that have a geometry that defines the typology of the element it represents with centimetre precision. BIM objects must allow for interference analysis. With respect to the discipline of pavements and earthworks, it will be necessary to define a precise and complete section in which its layers are differentiated by materials and units of work. It must also be possible to divide the route into sections so that the risk areas can be precisely differentiated based on the units of work. In addition, embankment and excavation volumes must be obtained, as well as their slopes, to differentiate them, which must be coordinated in plan and elevation with the section of the road surface and with the natural terrain. With respect to the disciplines of structures, drainage, and services affected, it will be necessary to model all the elements that are the object of analysis by means of a BIM object with a geometry with centimetre precision, but it will be necessary to model fabrication details such as armatures, wall bushings, etc.

In the case of health and safety elements, objects representing preventive measures must be modelled unambiguously and with the centimetre precision required at this stage. It will not be necessary to model execution details.

- Dimensionality: All the elements that make up the disciplines must be three-dimensional.

- Location: They must be in absolute coordinates.

- Parametric appearance and behaviour: Same as LOINSH 200.

2.5.2. Level of Alphanumeric Information

Those relating to identification and associated information. The first maintains those indicated in LOINSH 200 plus those in “2_PROYECTO” Pset for objects in the health and safety discipline (Table 1).

The second remains the same “EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset, although it should be noted that there will be differences in its values (not in its structure) related to the granularity of the risk assessment. In general terms, it is proposed that this should last until there is at least one BIM object to which a risk work unit is associated, in this case according to NAPWC [65], as established in Table 2.

Table 2.

Association of disciplines with the elements of the road, as well as with the work units of risk of ANECOP [64] in the construction project stage.

2.5.3. Level of Documentary Information

It will be necessary to define the documentary information parameters belonging to the “DocumentosSeguridadSalud” Pset that are specified at the end of Table 1.

2.6. LOINSH 350

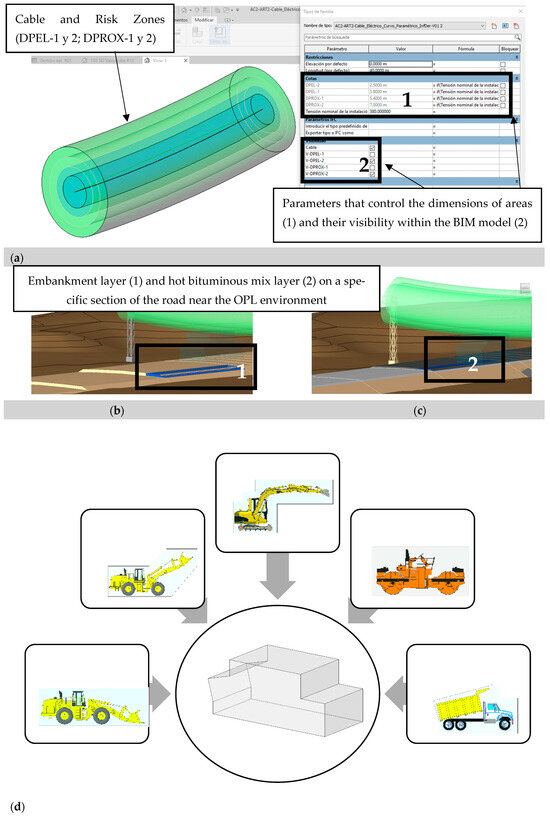

This LOINSH will be applied when the risk to be assessed requires any of the following conditions: 4D information, generation of risk areas associated with the execution of the work unit or any existing element, or there are special risks according to the regulations, for example, the RD 1627/1997 [26].

2.6.1. Graphical Information Level

The same approach as for LOINSH 300 is adopted, increasing the level of detail, allowing the route to be divided into short sections (1 to 10 m) and all road surfaces to be segregated by layers, allowing 4D construction simulation of the sections and layers, associating BIM objects with others that simulate safety zones for the element to be analyzed and risk zones for machinery, and incorporating BIM objects, at least for the envelopes of the machinery necessary for the execution of that work unit. BIM objects must allow for interference analysis.

2.6.2. Level of Alphanumeric Information

In this LOINSH, the BIM objects will incorporate the “1_IDENTIFICACION” and “EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset in the same terms as the LOINSH 300, along with some parameters of the “2_PROYECTO” Pset and “3_OBRA” Pset. The reason for incorporating these parameters is to consult the information related to the machinery, the breakdowns of the work units (02_01_CAPITULO, 02_02_SUBCAPITULO, 02_07_UD OBRA and 02_08_INDIRECTO of the “2_PROYECTO” Pset), and a third parameter (03_01TAREA of the “3_OBRA” Pset) to carry out the construction simulation. This can be found in Table 1.

2.6.3. Level of Documentary Information

As in the LOINSH 300, a URL parameter will be necessary to link the corresponding information from the Health and Safety Study by discipline. In addition, the BIM object will have information associated by one or more URL parameters on the construction process, with information on the assembly, maintenance, and dismantling plan of auxiliary elements such as scaffolding or shoring. This information must be inside the folder whose link is entered to the parameters within the “DocumentosSeguridadSalud” Pset. In order to manage health and safety on roads with BIM, it will be necessary to define the information requirements, which are different depending on the phase. This makes it necessary to establish several levels of information (LOINSH 100, 200, 300, and 350). Finally, according to the disciplines of the BIM manual of the Directorate-General for Mobility and Road Infrastructure of the Regional Government of Extremadura [67], the characteristics of these LOINSH are defined in Table 1 and Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of the definition of the LOINSH proposed for the preliminary project and construction project phases.

3. Results

3.1. Introduction and Application Case

The LOINSH’s standardization proposal is validated in the application to a real road project. In addition, different commercial software specialized in the BIM design of roads has been used for its validation. Although standardization can be extrapolated to other software and commercial houses, software from the Autodesk suite has been used, such as InfraWorks 2024 or Civil 3D 2024, specific to infrastructures and Revit 2024 more typical of buildings. Finally, NavisWorks 2024 is used for 4D simulations. Civil 3D 2024 and Revit 2024 are used in different risk assessment processes to demonstrate the applicability of standardization in different software and contrast the scope and limitations of each.

The choice of one or the other depends on the nature of the project, the handling of the tools by the health and safety team and the scope of the risk analysis. Finally, we will also work with models exported from these programmes to an Open Standard BIM format (IFC).

The results of this research aim to validate the proposed methodological framework at a conceptual level to demonstrate the effectiveness of the organization of safety information in a road project using LOINSH, which provides benefits in the automation of risk assessment. Thus, the application of the proposal will be considered in a single example case, the results of which can be extrapolated to projects of other characteristics.

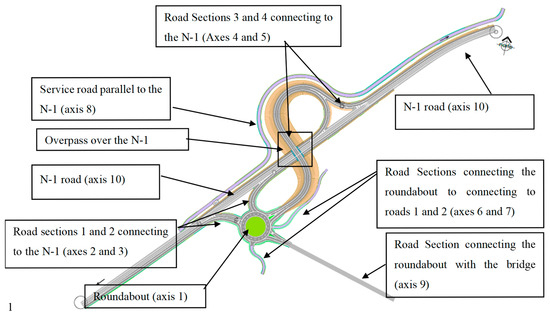

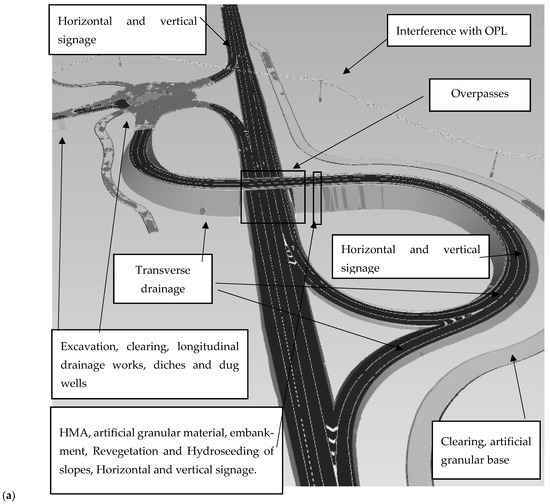

The example project consists of a road located in Miranda de Ebro, Burgos (Spain) to eliminate the level crossing of KP 456 + 727 of the Madrid–Hendaye railway line. To this end, there is a distribution roundabout, an overpass over the National Highway 1 (N-1), a section connecting the underpass with the roundabout, a section connecting the roundabout with the bridge, two sections connecting the roundabout to roads as a replacement for these, four access or exit branches to the N-1, and, finally, a service road parallel to the N-1 (Figure 2). In this investigation, an analysis is carried out of the safety conditions of activities common to road projects regardless of their dimensions, typology, location, etc. For this reason, the case chosen serves as a particular asset on which to demonstrate the viability of applying the methodological framework to a real road so that the results can be extrapolated to any other road project, thus demonstrating the transferability of the proposed LOINSH.

Figure 2.

General plan of the project.

3.2. Generation of the BIM Model for the Preliminary Project Phase with LOINSH 100 and 200 Requirements

First, a BIM model for road safety is created, focused on analyzing safety at the preliminary design stage. It contains the following disciplines: pavements and earthworks, structures, affected services, and health and safety.

The information contained in these disciplines is compiled by specific working teams. The health and safety team collects this information and integrates the results of the risk assessment in accordance with the LOINSH that has been established. In this case, the most appropriate thing would be to use the LOINSH 100 or 200, since, at this stage, it would not be necessary to have a centimetre accuracy, as is required for LOINSH 300 or 350, but it would be sufficient to arrange conceptual or generic objects with schematic (LOINSH 100) or metric (LOINSH 200) precision that inform the technicians of the location, position, and interference of these objects with other elements of the project, since the objective of this phase is not to solve all the design problems but to have a vision of the general configuration of the project, so a generic conception of the definition of structures, pavements, Affected Services, drainage works, and others will be sufficient.

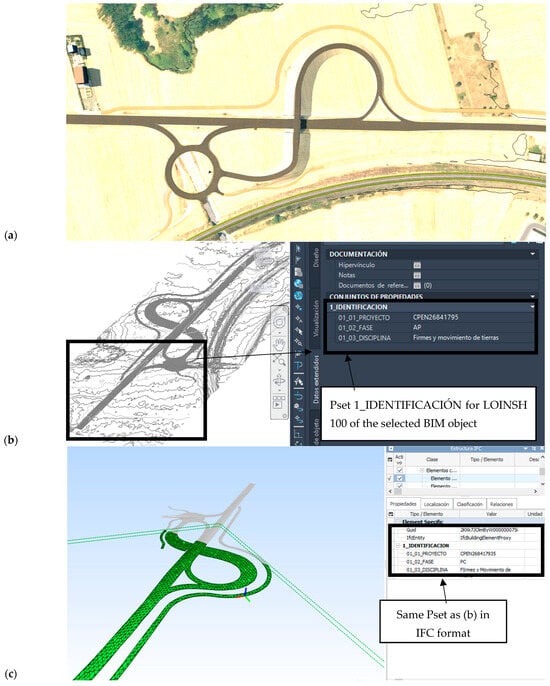

For health and safety assessment, the first step is to create the BIM model of the existing conditions. This was carried out with InfraWorks 2024 with the ETRS89 coordinate system to which vector files were added with information on the lines in the surrounding area of Miranda de Ebro. To this is added the topographic surface, imported as a Digital Terrain Model, and the orthophoto of the area. From this, it is modelled at the preliminary project level, obtaining an approximate geometry of the section and slopes of the necessary earthwork (Figure 3a). In this preliminary design phase, the export to Civil 3D 2024 continues to finalize the geometric fit in plan and elevation.

Figure 3.

BIM objects of the pavement and earthwork model with a LOINSH 100. (a) InfraWorks 2024, (b) Civil 3D 2024, (c) BIM Vision (IFC), and (d) Revit 2024.

In this phase of development, the project is defined as a 50 cm package, with no separation between layers. For this reason, the safety technician prescribes a LOINSH 100 for the safety assessment. From this, the modelling team takes from the surface with the axes of the design road in plan and the contour of the work in InfraWorks 2024 a three-dimensional extrusion of 0.50 m thick. This is a first BIM object at a LOINSH 100 level of the pavement and earthmoving discipline (Figure 3b), since its precision is schematic and it is a BIM object with a level of conceptual detail (Table 3). The health and safety team can then carry out their work through Civil 3D 2024 or through Revit 2024. If it is through the latter, it is necessary that, from Civil 3D 2024, it is exported to IFC format (Figure 3c) and then imported into the software itself (Figure 3d). As can be seen in the figures, this LOINSH 100 incorporates the information of the established Pset (Table 1).

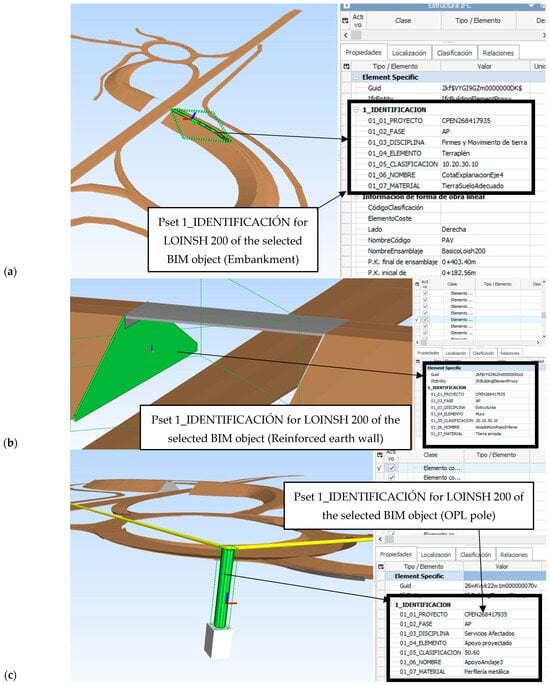

In a more advanced phase of the design in the preliminary design phase, the health and safety technician establishes a LOINSH 200 to have greater precision and division of the road, which allows greater granularity of the risk assessment. To this end, continuing with the discipline of pavements and earthworks, 10 sections of linear works were created, one for each axis of the project, as well as the affected service OPL. At this point, it is not necessary to resolve the road junctions with precision (Figure 4). Figure 4a shows the BIM object of a section with a LOINSH 200 with risk information in relation to earthworks in this phase. The design carried out in the geometry of the road is observed in accordance with the needs of the health and safety team, according to Section 2.4. In this case, it was carried out in Civil 3D 2024, differentiating main axes and in sections of less than 50 m. In addition, these BIM objects do not define any typology, presenting a generic 3D geometry that gives information about the location of the element with metric precision (Table 3).

Figure 4.

BIM objects of models from different disciplines with LOINSH 200 IFC format in BIM Vision. (a) Pavements and earthworks, (b) structures, and (c) Affected Services (OPL).

It can also be seen that these objects have non-graphic information incorporated. In this way, the health and safety team can manage the information model in a simple way, as well as carry out filters and queries for risk assessment. In this case, the “1_IDENTIFICACION” Pset was added (Table 1), according to the Directorate-General for Mobility and Road Infrastructure of the Regional Government of Extremadura [67], Table 3, and Section 2.4, as well as additional parameters such as the axis, the side, the PK, the volume, etc., which allows for the spatial location of the area to be determined and can be staked on site, if necessary.

With respect to the discipline of structures, in Civil 3D 2024, the geometry of the bridge over the N-1 was developed, modelling the BIM objects that represent the bridge according to LOINSH 200: two reinforced earth walls, the embankment slope, the deck, and the abutments (Figure 4b).

With respect to the discipline of Affected Services, the execution of the road crosses an OPL that is represented by generic BIM objects of the outer envelope of the poles and the route of the high-voltage cables (Figure 4c), as described in Section 2.4.

3.3. Health and Safety Analysis in the Preliminary Design Phase

Once the model has been developed with the BIM objects with the LOINSH 100 and 200, the technician will carry out the risk assessment by entering the information in the parameters of the “EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset (Figure 1).

In this case, and as established in these LOINSH, for the evaluation, a grouping is carried out in the main work units and by previous or habitual work, field work, adverse weather conditions, etc., according to the criteria of the NAPWC [65]. After that, the risk assessment methodology is applied: identification, assessment of the level of risk based on probability and severity, preventive measures, and reassessment.

For the validation of the LOINSH, the risk information structures of the work units have been created: excavation, embankment, overpass over N-1, and Affected Services (OPL Replacement). This structure is created by the health and safety technician in Excel.

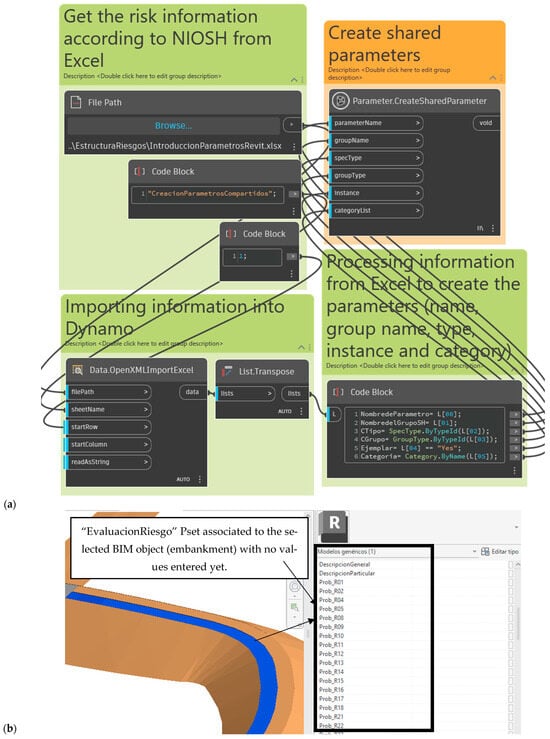

The association of the parameters to the BIM objects of the work units depends on the software chosen. For example, when using Autodesk Revit 2024, risk information structured in Excel was fed into BIM objects using project parameters. To reduce manual process time and reduce errors, two Dynamo scripts are developed. The first has a code to create a file of shared parameters according to the “EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset (Table 1) from Excel and adds them as project parameters to the Revit 2024 model (Figure 5a), automatically generating the “EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset in the BIM model (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Structure of the “EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset in BIM model. (a) Visual programming code in Dynamo to associate parametric information from a sheet in Excel to BIM objects in Revit 2024, (b) BIM object of the pavement and earthwork model with the risk assessment parameters incorporated in Revit 2024.

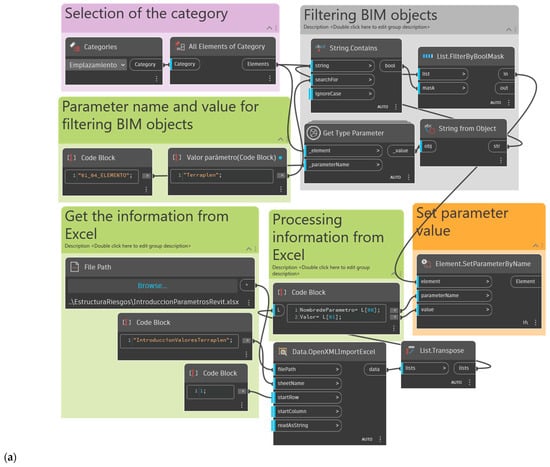

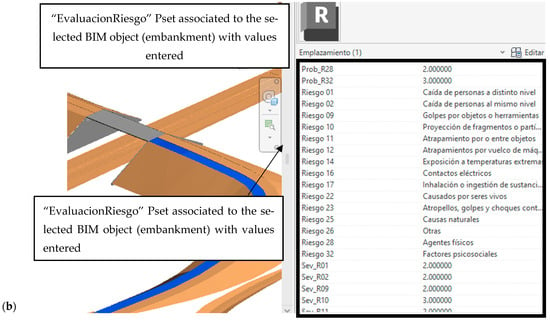

The second script associates the values of each of the parameters of the risk information structure from the Excel sheet to the different BIM objects of the model based on those of the “1_IDENTIFICACION” Pset (Figure 6a). To display only the parameters that apply to that BIM object, a specific category is assigned to that unit of work that represented that BIM object. Figure 6b checks how the category “Site” was associated with the execution of the embankment, and by executing the script, only the parameters of the risk existing in it are associated.

Figure 6.

“EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset values in BIM model. (a) Visual programming code in Dynamo to associate “EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset values of a sheet in Excel to BIM objects in Revit 2024, (b) BIM object of the pavement and earthwork model with the values of the risk assessment parameters.

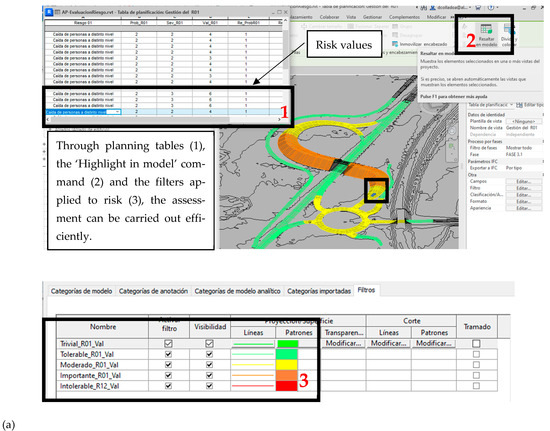

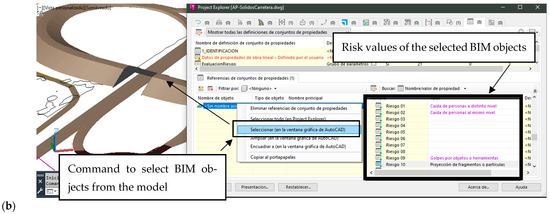

From here, technicians perform risk assessments within the model (Figure 7a). It is worth mentioning that risk values can be managed quickly and efficiently using planning tables in Revit 2024 (Figure 7a) or Project Explorer in Civil 3D 2024 (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Risk assessment within the model. (a) Running filters in Revit 2024 for the graphical representation of risk assessment and management using planning tables. (b) Managing risk assessment parameter values in Civil 3D 2024 with Project Explorer.

In the case of OPL, when the health and safety technician detects its presence and it is a special risk [26], it is necessary to analyze the execution of works near it, which is not possible with a LOINSH 200, as it has metric accuracy. In addition, as its analysis requires generating the risk areas of the OPL, it will be necessary to apply a LOINSH 350 according to the requirements established, see Section 2.6. However, with the geometry of the LOINSH, the minimum free distance is not met, resulting in an intolerable risk that makes it necessary to divert it.

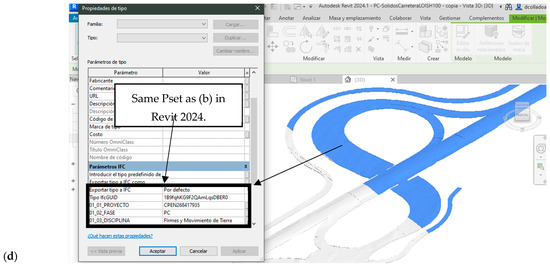

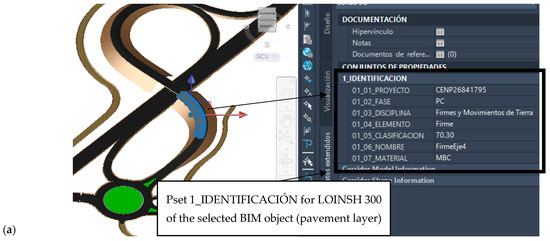

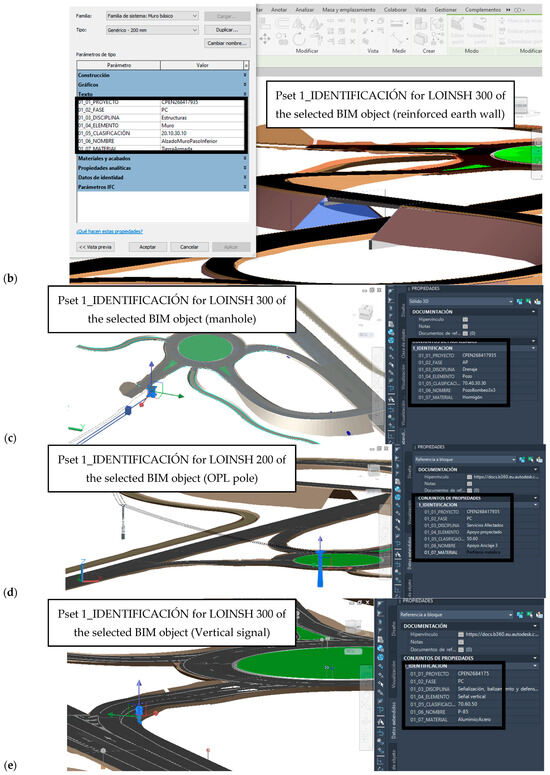

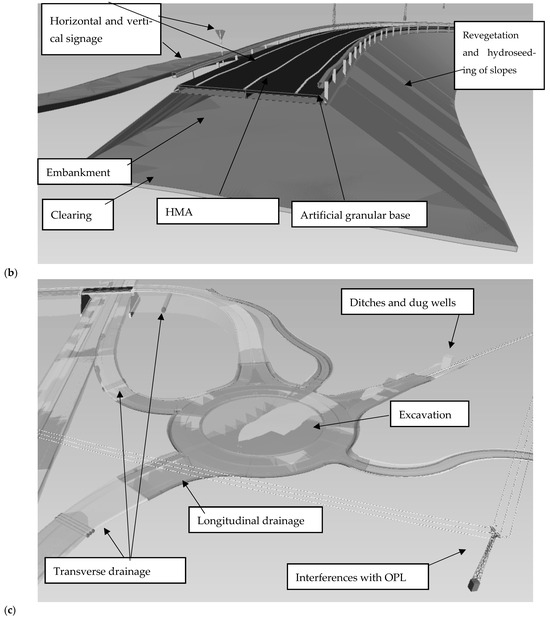

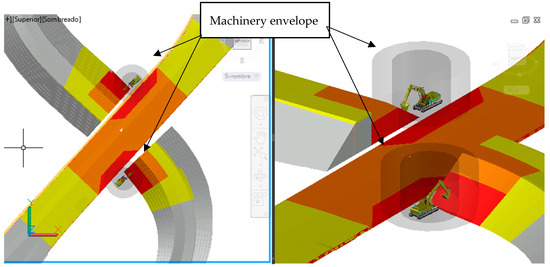

3.4. Generation of the BIM Model for the Project Phase with LOINSH 300 and 350 Requirements

For the validation of the standardization proposed in this phase, the model is developed from the initial one incorporating all the disciplines that are modelled in Civil 3D 2024, except for the structure, which, in order to reach the level of detail required in this phase, the LOINSH has to be modelled in Revit 2024 (Figure 8 and Figure 9). The modelling of BIM objects is centimetre accurate for the resolution of interferences and supervision of the construction process, according to the requirements of Table 3 [67].

Figure 8.

Road model BIM objects with a LOINSH 300 and the “1_IDENTIFICACION” Pset. (a) Pavements in Civil 3D 2024, (b) structures in Autodesk Revit 2024, (c) drainage in Civil 3D 2024, (d) Affected Services (OPL) in Civil 3D 2024, and (e) horizontal and vertical signage in Civil 3D 2024.

Figure 9.

Federated model in NavisWorks 2024, where the work units and their relationship with BIM objects from different disciplines are shown. (a) Complete, (b) cross-section of the road, and (c) roundabout.

For the discipline of pavements and earthworks, pavement sections were defined as follows: width, thicknesses, and ditches (Figure 8a), with the segregation by layers according to Table 3. In the structures discipline, the deck with three trough beams, the neoprene supports, the foundation, and the reinforced earth walls were defined (Figure 8b). The drainage discipline includes the BIM objects of ditches and transverse drainage works, manholes, and collectors until their connection with the existing sewerage network (Figure 8c). In the case of the discipline of Affected Services and the deviation of the OPL, the towers are modelled with a BIM object that defines their precise typology and dimensions and the high-voltage cable with its theoretical catenary curve design (Figure 8d). Given the type of risk when requiring a LOINSH 350, it is necessary to model the risk areas and simulate the construction phases, but this is not possible to do in Civil 3D 2024. Finally, in this phase, the discipline of Signalling, Beaconing, and Defence appears, which is not required for previous LOINSH, modelling the horizontal and vertical signage and barriers (Figure 8e), in accordance with the provisions of Table 3, to assess the risks of the implementation of this discipline.

3.5. Health and Safety Analysis in the Project Phase

The risk information structure follows the “EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset (Table 1) as set out in Section 3.3, the increase in the level of detail of the assessment assumes that there is at least one BIM object to which the risks of a unit are associated [65], as established in Table 2.

Figure 9 shows a federated model of all disciplines in NavisWorks 2024, where the risk work unit associated with the BIM objects marked in that figure is identified, allowing for the management of the associated information.

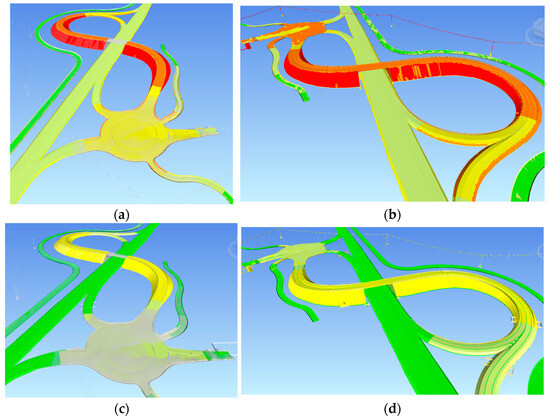

Based on parameterization, the risk assessment in the BIM model has been automated according to the probability and severity of the area analyzed, which must be determined by the technician according to the section and unit of work analyzed. As an example, the result obtained after incorporating the risk assessment into the model with LOINSH 300 is presented in 01. Falling to different levels for the discipline of pavements and earthworks (Figure 10). It should be noted that the appearance of these models by means of colour coding represents the risk levels proposed by the SIOSH methodology [27] and follows the stipulations of the visualization requirements for the LOINSH 300 in Table 3, which allows the safety technician to obtain quick and visual information on the results of the safety and health assessment carried out on the project.

Figure 10.

General visualization in NavisWorks 2024 of the BIM model of the discipline of pavements and earthworks (BIM objects of the HMA pavement and granular material base, excavation slopes, and embankment) in the construction project phase of the assessment of the risk of falling at different levels. Red (intolerable), orange (important risk), yellow (moderate risk), light green (tolerable risk), and green (trivial risk). (a) Initial risk assessment, perspective 1, (b) initial risk assessment, perspective 2, (c) reassessment with provision of preventive measures, perspective 1, and (d) reassessment with provision of preventive measures, perspective 2.

Within the discipline of pavements and earthworks, in accordance with the initial risk assessment 01 (Figure 10a,b), the configuration of the pavement (composed of two layers) is identical in both work units. Given the division carried out, it is possible to carry out a detailed analysis of the risk according to areas, so in the sections of road connecting to the N-1, the risk is moderate (medium probability (2) and harmful severity (2)), continues as moderate in the area of the roundabout, reaching trivial (probability 1, severity 1) in the execution of lanes on the N-1, due to a lower probability of machinery present is lesser, and tolerable (probability 2, severity 1) at the main road due to the lower height in its execution (Figure 10a,b). In the access ramps to the overpass, the probability is maintained, but the severity is increased if the risk occurs due to the height of the earthwork, becoming important (probability 2, severity 3). The application of the graphic standards allows us to quickly observe that the greatest risk of falling at different levels is around the ramps (axes 4 and 5), leading to the overpass crossing the N-1. It is thus demonstrated how the standardization of the proposed LOINSH allows for greater granularity and ease in the analysis and risk management.

After the evaluation, preventive measures are applied in areas of important risk: construction signage, 1-metre-high polypropylene mesh barrier, railings, and the corresponding documentary information. After that, when carrying out the risk reassessment (Figure 10c,d), the probability of the risk is modified from the pavement layers and the embankment so that the important risk (probability 3 and severity 2) becomes moderate (reassessed probability 2 and reassessed severity 2), what was assessed as moderate became tolerable (reassessed probability 1 and reassessed severity 2), and what was tolerable became trivial (reassessed probability 1 and reassessed severity 1) (Figure 10c,d).

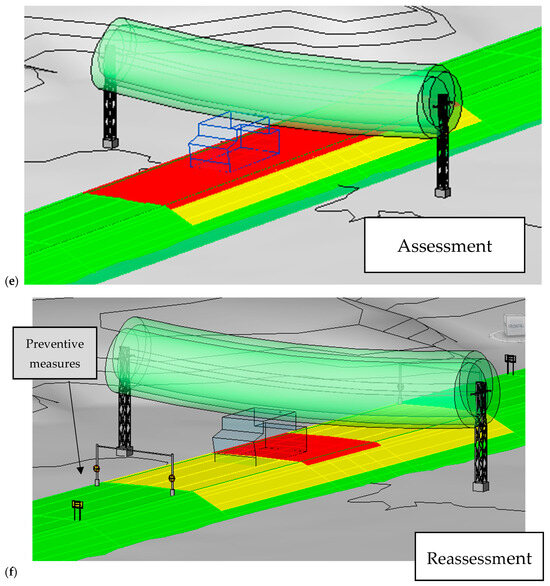

3.6. Health and Safety Analysis of Special Risks in the Project Phase

The 380 kV OPL that crosses perpendicular to the main road and some road sections is a special risk. In the preliminary design stage, the BIM object that represents the discipline of pavements and earthworks included the risks associated with an OPL. The proposed standardization for the LOINSH 100 of the BIM object of the area (level of detail by sections Table 1), allows for traceability of the risk assessment by allowing the area of impact of the OPL (Civil 3D 2024) electrical risk to be marked. On the other hand, the standardization of risks in the LOINSH (“EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset parameters, Table 1–Figure 11a) allows for the result of the evaluation to be graphically displayed (in this case red, as it is intolerable). This parameterization enables automation using Dynamo (Figure 11b).

Figure 11.

Special risk assessment in the preliminary design phase with a LOINSH 100 in Civil 3D 2024. Need to set back the OPL Route due to an intolerable risk in the execution of the first section of axis 4 of the project. (a) “EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset, (b) Dynamo script for colour mapping.

The analysis has been carried out in Revit 2024, considering it is more suitable to meet the requirements of LOINSH 350 (Table 3) by allowing, for example, the creation of BIM objects for risk zones. Among them are that BIM objects must have associated risk zones, as is the case of the OPL with its electrical risk zones (Figure 12a), as well as the phases of the execution of the embankment and pavement layers (Figure 12b,c) or the machinery acting and its envelope (Figure 12d) to determine the interaction between the two. Risk management is carried out from the “EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset (Table 1), which, applied to the division of BIM object by layers of the embankment geometry and pavement according to planning, allows for an analysis of the risks by phases, defined in each one by the interference between machinery and the risk area and to the standardization of colours defined (Figure 12e,f). This is performed in sufficient detail because the LOINSH 350 establishes a requirement that the accuracy of the geometry must be in centimetres (Table 3).

Figure 12.

OPL special risk analysis with LOINSH 350. (a) BIM object of the OPL with its 4 risk zones and their associated parameters, (b) phase of embankment execution by sections and layers according to construction simulation, (c) phase of HMA spreading by sections and layers according to construction simulation, (d) final envelope based on the set of geometries and positions of the machinery used to execute that section of road, (e) risk assessment of the study area for the execution of the embankment and the pavement (red (intolerable), orange (important risk), yellow (moderate risk), light green (tolerable risk), and green (trivial risk)), and (f) risk reassessment with preventive measures in place (1 = light green, 2 = dark green, 4 = yellow, 6 = orange, and 9 = red). Note: Delimitation of the zones according to the diagram in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

There are significant risks that can occur on a roadwork due to interference between tasks. To carry out the risk analysis, it is necessary that the BIM objects meet the requirements of the LOINSH 350 to determine the machinery that acts, execution phases, and risk areas. For example, Figure 13 shows the risk analysis of the interaction between the refining of the slopes and the execution of the nearby drainage work. It is shown how the proposed standardization allows one to simulate the interaction between the risk of hitting workers from the backhoe to workers by applying the standards of “1_IDENTIFICACION” Pset information, centimetre accuracy, 3D representation, “EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset (Table 1), and risk areas (Table 3).

Figure 13.

Visualization of the interference analysis model between construction activities in the construction design phase of the risk assessment of collisions, crashes, and impacts with vehicles in Civil 3D 2024 with LOINSH 350. Red (intolerable risk), orange (important risk), and yellow (moderate risk).

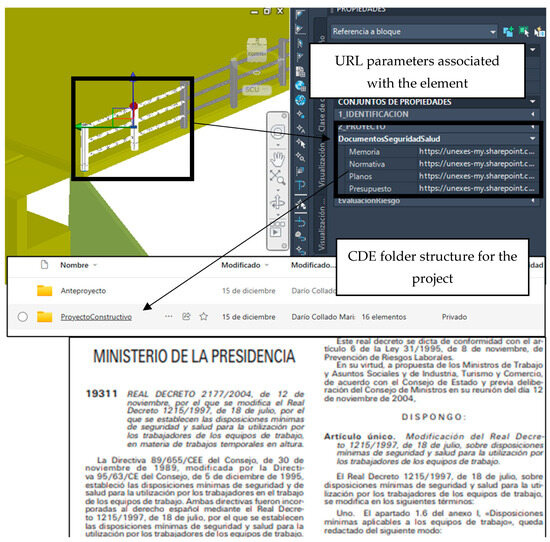

3.7. Documentary Information

Figure 14 reflects how the proposed standardization includes information on the aspects that safety equipment must comply with (hygiene and welfare facilities, collective protection equipment, etc.) such as technical specifications, requirements, and regulations. In this case, the “DocumentosSeguridadSalud” Pset is applied according to LOINSH 300 (Table 1 and Table 3). Figure 14 shows how Royal Decree 2177/2004, which establishes the minimum health and safety requirements for the use of work equipment by workers in temporary work at height, is linked to the sergeant-type railing.

Figure 14.

Documentary information with a LOISNH 300 linked to the BIM objects of the model through the CDE that will appear in the specifications of the Health and Safety Study. It shows RD 2177/2004, which establishes the minimum health and safety provisions for use of work equipment by workers in terms of temporary work at height associated with the BIM railing object.

4. Discussion

Construction is one of the economic activities with the highest number of occupational accidents [1,2,3]. Road construction requires a specific and standardized approach to risk assessment [20,21,22,23] and detailed analysis due to special risks such as high-voltage lines [26,27]. Although there are a significant number of investigations focused on reducing this accident rate [21,23,28,29], they have not been efficient [4].

Construction 4.0 technologies make it possible to improve the health and safety of construction sites [35,36], highlighting the BIM methodology [37], encompassing the management of safety information and risk assessment within its eighth dimension [42].

This eighth dimension [43] consists of work processes that pursue objectives that will give rise to requirements [55]. These will define a way forusing BIM [40], which varies depending on the phase [67].

Therefore, anyone considering a working process to address 8D must define a LOINSH that responds to the above. In fact, those authors who have done so have implicitly assumed a LOINSH 300 in the case of [28,49] and 350 in the case of [52] without addressing the issue. A correct definition of LOINSH [55,57] would complete its work, frame it correctly within the project life cycle, and be the link between all of them.

However, there is no methodology and data structure for health and safety (LOINSH) that can be integrated into BIM models, so the objective of this research is to propose the methodology and framework for standardizing workers’ health and safety risks to comply with the standard ISO 7817-1:2024 [57]., which responds to ISO 19650-1 [55].

4.1. Safety Information from the Design Phase

In road design, PtD must be applied to reduce accident rates in later phases [32]. This research has shown how it is possible to implement the methodology and information structure in BIM from the design phase when the health and safety technician establishes the LOINSH requirements for each BIM object of the model, which is aligned with these investigations, from the preliminary project as Kamardeen [33] pointed out, thus taking advantage of the benefits of PtD [32]. The early establishment of these LOINSH is aligned with the research of Muñoz and Llamo [41] to develop a preventive strategy for the correction of failures that can occur during the life cycle of the infrastructure, which is economically and technically more feasible than applying corrective measures on the side later.

On the other hand, standardization in four levels avoids the overrepresentation of information and its duplicity [58]. In addition, by increasing the level of detail and granularity of the information, the analysis capabilities increase as the project information progresses and/or the type of risk. This is in line with Massimo-Kaiser et al. [60], who establish this concept as a dynamic and progressive entity to be modified according to changes in the information available and according to the life cycle of the asset.

4.2. LOINSH and Pset Structure

For each of the LOINSH, the way to address Geometric Information (LOG), Alphanumeric Information (LOI), and the (DOC), is in compliance with the ISO 7817-1:2024 [57]. This division of the LOINSH allows for the traceability of the information in different assessments when introducing a risk reassessment, which would help reduce accidents, according to Liu et al. [8].

In addition, with respect to the LOG (Table 3), it should be noted that the LOINSH 100 requires BIM objects with schematic precision and specific ramifications aimed at marking a specific risk. This can be used by safety technicians to carry out risk assessments at a very early stage of the project or work units, which, due to their low complexity, can group together several risks, requiring conceptual BIM objects, without seeking to be precise in their geometry (Figure 3 and Figure 11). The LOINSH 200 does have a 3D requirement, which has shown benefits for risk detection and task planning, allowing for the development of higher quality proactive prevention [44], so that even when there is no detailed Geometric Information, there will be a view of the overall configuration of project risks (Figure 4). In the project phase, the available information is greater, as well as the requirements of risk analysis, so the BIM objects of the disciplines will be LOINSH 300 or 350. This implies, in addition to 3D, 4D, centimetre precision, division and segregation by layers, or the possibility of defining risk areas (Figure 8 and Figure 12). This allows us to achieve the benefits that Hire et al. [43] indicated for safety and health by applying 3D models and planning.

In addition, as has been demonstrated in the results (Figure 7, Figure 12 and Figure 13), the proposed LOINSH 300 and 350 allow for the achievement of strengths that the BIM provides by being able to detect high-risk tasks [31], as well as the detection of potentially dangerous areas [45].

Regarding the LOI (Table 1), this paper presents a set of Pset parameters recognized by the IFC standard (Figure 4 for the LOINSH 200 and Figure 8 for the LOINSH 300), which allows for the management of security information, as proposed Ait-Lamallam et al. [53].

In the case of DOC, (end of Table 3) by providing the “DocumentosSeguridadSalud” Pset (end of Table 1), it is possible to consult, for example, the Technical Report on Health and Safety in the Common Data Environment (CDE) (Figure 14). These links participate in the automated generation of protocols for the identification and action against risk scenarios based on the security information that is duly organized in the model, as established by Hire et al. [43].

The organization in different LOINSH (Table 3), and the parameter structure of the BIM model (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 8), gives rise to a single database of the project, improving the coordination of safety technicians [40,46], a factor of safety reduction [10]. It also provides an organized structure for the information for safety management, avoiding contradictory, confusing, and disorganized safety protocols, another cause of reduced safety in construction sites [15].

This will solve the gap detected by Taat et al. [13] in regard to the lack of standardization, as well as the lack of innovative strategies for the implementation of security defined by Boadu et al. [14]. All of this will make it possible to overcome the technological limitations that prevent the application of new digital tools indicated by Yap et al. [16].

4.3. LOINSH Risk Assessment

The results have shown how the established LOINSH allows the risk assessment to be carried out by applying validated methodologies both at a general level [27] and in BIM [49,52]. This represents a significant advance in establishing the information requirements to be able to efficiently carry out the analysis according to the type of risk and the stage of development of the project, which are issues not addressed in these investigations.

It has been demonstrated how, with the established LOINSH requirements, each BIM object can represent one or more units of work, the activities for its execution, and the risks (Figure 9). Thus, these are identified and related to activities and units reflected in the BIM model, which solve the problem announced by Mihić [6] on the difficulty of defining and predicting risks in road construction projects.

On the other hand, by establishing the requirements for the association of activities and risks of an ethereal and unobservable nature, with BIM objects (Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13), it represents an improvement in training and the assimilation of safety information by workers, as well as in risk awareness, since the visual information is much clearer and more direct than the guidelines specified by the prevention technicians orally or by text, as they highlighted [8,9,47], which can imply an increase in the commitment of workers to comply with safety regulations. These requirements will allow for a more detailed analysis of situations of interference between vehicle and pedestrian traffic in the vicinity of the work, detected as a critical risk factor by Kumar Das et al. [23]. All this will facilitate the performance of analysis of the interaction between external and internal factors, which is a cause of accidents [24,25].

The possibility of automation that allows for standardization (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 11) will reduce errors in the review and information exchange processes that have been announced [61,62], improving the reliability and efficiency processes.

The automation of these processes allows for the identification of high-risk tasks [31] and the detection of potentially dangerous areas [45], such as the high risk of falling at different levels on the overpass in Figure 10, or the automated assessment of risk levels on site for the provision of preventive measures and prevention of risk situations from the design phase [48,49], as can be seen in Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13; all of these demonstrated benefits of integrating risk prevention into BIM.

It should be noted that the standardization of the appearance requirements of the LOINSH by colour-coding according to risk levels [27] improves the understanding of risks by offering accurate, clear, and direct visual information [8,9,47], helping to raise awareness among workers [17] and increasing commitment, motivation, and responsibility to apply risk prevention protocols [18].

It should be noted that the evaluation mentioned [27] is qualitative in nature. For this reason, despite the automatic input of preliminary risk values (Figure 5 and Figure 6), this must be reviewed and further developed by the health and safety technician graphically within the BIM model (Figure 7). At his discretion, he can divide some risk zones or others and more or less information (Figure 10). Introducing a LOINSH (Table 3) helps to standardize the assessment and subtracts subjectivity, resulting in a higher quality risk assessment.

Reducing the significant accident rate is urgent in the construction sector [1,4,5] and especially in road construction [8,25]. As it has been demonstrated through LOINSH in road projects, it is possible to integrate occupational risk management into BIM; the improvement it will produce in the organization will contribute to risk reduction. By following BIM standards such as the ISO 19650-1 [55] and the ISO 7817-1 [57], the application of this methodology in the sector, especially with the growth that the use of BIM is having in road projects [38], is allowed for.

In this sense, this research for the improvement of occupational risk prevention contributes to the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2030, in particular, SDG3 “Good Health and Well-being” and SDG8 “Decent Work and Economic Growth” [7].

4.4. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

The following limitations should be considered when applying the methodology presented:

- The correct establishment of the LOINSH required at each milestone and for each risk is key to the correct application of the methodology. Oversetting can lead to inefficiencies that will become exponential as the project becomes larger.

- This definition of LOINSH is based on the qualitative SIOSH methodology. If another methodology of the same type is used, it should be adapted accordingly with regard to the identification and assessment of risks. The methodology would not be valid if a quantitative risk assessment is used.

- The general frameworks of the methodology are transversal to any BIM software, making minor adjustments regarding the introduction of non-graphical information, modelling, and discretization of BIM objects. However, if this software does not allow for the use of visual programming such as Dynamo, Grasshopper, or similar, the processes to be automated will have to be performed manually. This will result in increased time and errors due to the human factor.

- The assessment methodology used is qualitative and does not allow for sensitivity analysis.

Furthermore, as a result of the research carried out, the following lines of future research have emerged:

- Extend the LOINSH data structures to address the other phases of a road’s life cycle: construction, maintenance, and operation.

- To contrast the reduction in on-site accidents in a road project through the application of the methodology presented in this thesis, a comparison with a project carried out in the traditional way must be performed in order to obtain metrics that allow for the quantitative validation of the effectiveness of the proposed standardization of information. This will serve to reinforce the conclusions of this study and the research referenced.

- Create new automations that allow us to move from one LOINSH to another with ease, as well as to transfer the codes developed in Dynamo to an internal programming software so that it is integrated as a command within it, facilitating its application.

- Analyze the development of LOINSH in relation to quantitative risk assessment.

5. Conclusions

This research represents an advancement in the management of health and safety information in road construction projects using the BIM methodology according to ISO 19650-1 [55] from the design phase through the creation and proposed structure of the safety LOINs, known as LOINSH. Following the provisions of ISO 7817-1:2024 [57] in relation to the components of this information and the requirements to which they must respond, this study proposes four different levels that will mark the level of granularity of the BIM objects in the model and their accuracy: LOINSH 100 and 200 for the preliminary design phase, LOINSH 300 and 350 for the project phase.

The study contributes to the standardization of safety information by developing the data structure requirements for each of these LOINSH. Therefore, first of all, the context in which each of these LOINSH should be used is established according to the stage of the construction project. For the preliminary design phase, LOINSH 100 will be used when division into work units is not necessary, requiring schematic precision; while for LOINSH 200, risks must be grouped into sets of work units, whose BIM objects will have metric precision. For the project phase, LOINSH 300 will be used when the complete granularity of risks in work units is required, as well as a centimetric level of detail for the analysis of interference in the execution of activities; while LOINSH 350 will be applied when the risk to be assessed requires 4D information, the generation of risk zones associated with the execution of the work unit is required, or when there are special risks. Thus, it can be seen how each of these LOINSH respond to different needs at different stages of the project life cycle, which makes the management of security information a dynamic, progressive, and adaptive activity to changes that will require continuous review by those responsible for security, which will ensure the uniqueness of the required data at each stage, thus avoiding the overrepresentation of information and problems of duplication, as established by ISO 7817-1:2024 [57].

Likewise, for each of the LOINSH presented, the level of graphic information for each BIM object has been established, justifying the level of detail, dimensionality, location, appearance, and parametric behaviour. In addition, the standardization of Alphanumeric Information is proposed through Pset, sets of parameters recognizable by the IFC format, which ensures the management of security information in an open format without proprietary software restrictions. BIM objects that include LOINSH have a parameter structure definition for identifying information related to the project, phase, discipline, or work unit referred to through “1_IDENTIFICACION” Pset. Likewise, the risk assessment information is included in the “EvaluacionRiesgo” Pset, which contains all the parameters for obtaining the assessment and reassessment results according to the methodology of the SIOSH. Thus, in order to carry out the risk assessment proposed in the previous Pset on the model, it is established as a requirement that each BIM object represents one or more work units to which a series of activities are linked in order to execute it with its associated risks, which will be the assessment objectives. This risk parameter structure takes advantage of BIM’s automated assessment of risk levels on site to enable preventive measures and error correction from the design phase onwards. Regarding the Associated Documentation, the “DocumentosSeguridadSalud” Pset has been proposed to link the information contained in health and safety regulations or technical studies to the model using URL parameters.

Thus, this research has demonstrated how, based on the established LOINSH and the parameter structure presented, it is possible to manage safety information and assess risks during different stages of the road construction life cycle, analyzing the risks arising from the interference of work activities, those linked to the execution of different disciplines, and even those risks considered special, such as the interaction with overhead power lines (OPL), thus justifying that the integration of the BIM methodology through a parameter structure with standardized safety information that benefits occupational risk management in road projects and leads to improved communication flow between agents through the traceability of this information. This research has therefore proposed a framework for standardizing the health and safety risks of road construction workers based on the ISO 7817-1:2024 [57] standard using the BIM methodology in accordance with ISO 19650-1 [55], which will result in a reduction in the high accident rates suffered by workers on road projects. This study therefore aims to lay the foundation for the standardization of safety information for other types of projects in the construction sector in order to reduce their high accident rates and enable the application of the aforementioned standards, thereby extending the benefits of BIM to the safety management of construction projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C.-M., J.P.C.-P., M.N.-F. and A.C.-P.; methodology, D.C.-M., J.P.C.-P., M.N.-F. and A.C.-P.; software, D.C.-M.; validation, J.P.C.-P. and A.C.-P.; formal analysis, D.C.-M. and J.P.C.-P.; investigation, D.C.-M., J.P.C.-P. and M.N.-F.; resources, D.C.-M.; data curation, D.C.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.C.-M.; writing—review and editing, D.C.-M., J.P.C.-P., M.N.-F. and A.C.-P.; visualization, D.C.-M.; supervision, J.P.C.-P. and A.C.-P.; project administration, A.C.-P.; funding acquisition, A.C.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This publication has been made possible thanks the support of the company AC2 INNOVACIÓN (Spain) and the Pre-doctoral Grant from the Regional Government of Extremadura, co-financed by the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+).

Conflicts of Interest

Author Alfonso Cortés-Pérez was employed by the company AC2 Innovación, C/Santa Cristina 3, 10195 Cáceres, Spain. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| CDE | Common Data Environment |

| DOC | Associated Documentation |

| HMA | Hot Mix Asphalt |

| IFC | Industry Foundation Classes |

| LOG | Level Of Geometric Information |

| LOI | Level of Information |

| LOIN | Level Of Information Necessary |

| LOINSH | Level Of Information Necessary for Safety and Health |

| NAPWC | Navarre Association of Public Works Construction Companies |

| SIOSH | Spanish Institute for Occupational Safety and Health |

| Pset | Property Set |

| PtD | Prevention Through Design |

References

- ILOSTAT. Statistics on Safety and Health at Work. Available online: https://ilostat.ilo.org/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Choi, J.; Gu, B.; Chin, S.; Lee, J.S. Machine Learning Predictive Model Based on National Data for Fatal Accidents of Construction Workers. Autom. Constr. 2020, 110, 102974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Xu, K. Analysis of the Characteristics of Fatal Accidents in the Construction Industry in China Based on Statistical Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries News Release. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cfoi.htm (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Eurostat Accidents at Work Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Accidents_at_work_statistics (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Mihić, M. Classification of Construction Hazards for a Universal Hazard Identification Methodology. J. Civil Eng. Manag. 2020, 26, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNO Spain. EL Sector Construcción e Ingeniería Civil: Contribuyendo a la Agenda 2030 La Creación de Ciudades Sostenibles y Resilientes; UNO: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Tang, H.; Feng, R. Unraveling the Evolutionary Patterns of Construction Accidents: A Risk Assessment Framework Based on Average Mutual Information Theory. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]