1. Introduction

The stack effect in high-rise buildings is driven by buoyancy when the outdoor air temperature is significantly lower than the indoor air temperature. Under such conditions, vertical pressure differences develop along the building envelope and vertical shafts, and air is driven through elevator doors, stairwells, lobbies, and other leakage paths. When parts of a building are subjected to excessive pressure differences or when stack-effect-induced airflow becomes large, serious operational and safety problems can arise; therefore, appropriate control is required [

1,

2].

Stack-effect-related problems are broadly associated with two aspects of building performance: everyday operational (or residential) performance and disaster-prevention (life-safety) performance. In terms of operational performance, reported issues include malfunction and incomplete closing of elevator and internal doors, excessive noise, strong drafts in elevator halls and corridors, increased heating and cooling loads due to infiltration and moisture ingress, odor transfer, and degradation of heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) performance [

1,

3,

4]. From a life-safety perspective, the stack effect can significantly influence smoke movement and the spread of toxic gases during fire events and can also intensify the transport of airborne contaminants under non-fire conditions [

1,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Because these phenomena directly affect both occupant comfort and life safety, reliable mitigation strategies for stack effect are required in high-rise buildings.

Fundamental studies by Tamura and co-workers have clarified the physical mechanisms of the stack effect in tall buildings. Tamura introduced the concept of the thermal draft coefficient (TDC) to quantify stack-effect-induced pressure differences [

1,

2]. Subsequent airtightness studies of exterior walls, stair shafts, elevator shafts, and doors further demonstrated that internal divisions such as shafts and doors are generally less airtight than the exterior envelope and that division-by-division airtightness strongly influences stack-effect behavior [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. These findings provide the theoretical basis for the present study, where TDC-based relationships are used to interpret pressure distributions and to calibrate a multizone model of an actual high-rise office building.

Building on this fundamental knowledge, many studies have investigated stairwell and shaft pressurization and mechanical venting as practical measures for smoke control in tall buildings. Design manuals and handbooks for smoke management in high-rise buildings [

5,

6,

7] and experimental and analytical work on stairwell pressurization, shaft pressurization, and dedicated smoke-control systems [

8,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] have shown that pressurized stairs and shafts, combined with mechanical venting, can effectively limit smoke spread and control pressure differences during fire events. These works form the background against which the present study considers stack-effect control under non-fire conditions.

In parallel, several studies have proposed operational and design strategies that directly target stack-effect problems during normal building operation. HVAC-based pressure control and system operation have been shown to influence stack effect in tall buildings [

3,

4], while zoning, added divisions along vertical airflow paths, and shaft cooling have been suggested as ways to mitigate stack-effect symptoms in residential and office buildings [

23,

24,

25]. More recently, the combined effects of thermal buoyancy, wind action, lobby entrance conditions, on pressure differences have been analyzed for high-rise buildings [

26]. These studies show that local pressurization/depressurization, shaft cooling, zoning, and HVAC-based strategies can effectively alleviate stack-effect symptoms at specific locations.

Nevertheless, stack-effect problems in high-rise buildings continue to be reported. One important reason is that the examination and application of countermeasures have generally focused on the specific locations where problems are observed (for example, a particular elevator hall or lobby), without sufficiently considering the coupling of pressures and airflow throughout the building. In particular, the movement of the neutral pressure level (NPL) and the redistribution of pressure differences among floors and compartments have rarely been analyzed from a whole-building perspective, even in recent studies on pressurization, zoning, and HVAC-based control [

3,

4,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

24,

25,

26]. As a result, local countermeasures may successfully reduce stack-effect symptoms at the treated location but can inadvertently generate secondary problems, such as increased pressure differences, airflow, noise, and incomplete door closing, at other floors or in other compartments through inter-compartment pressure redistribution.

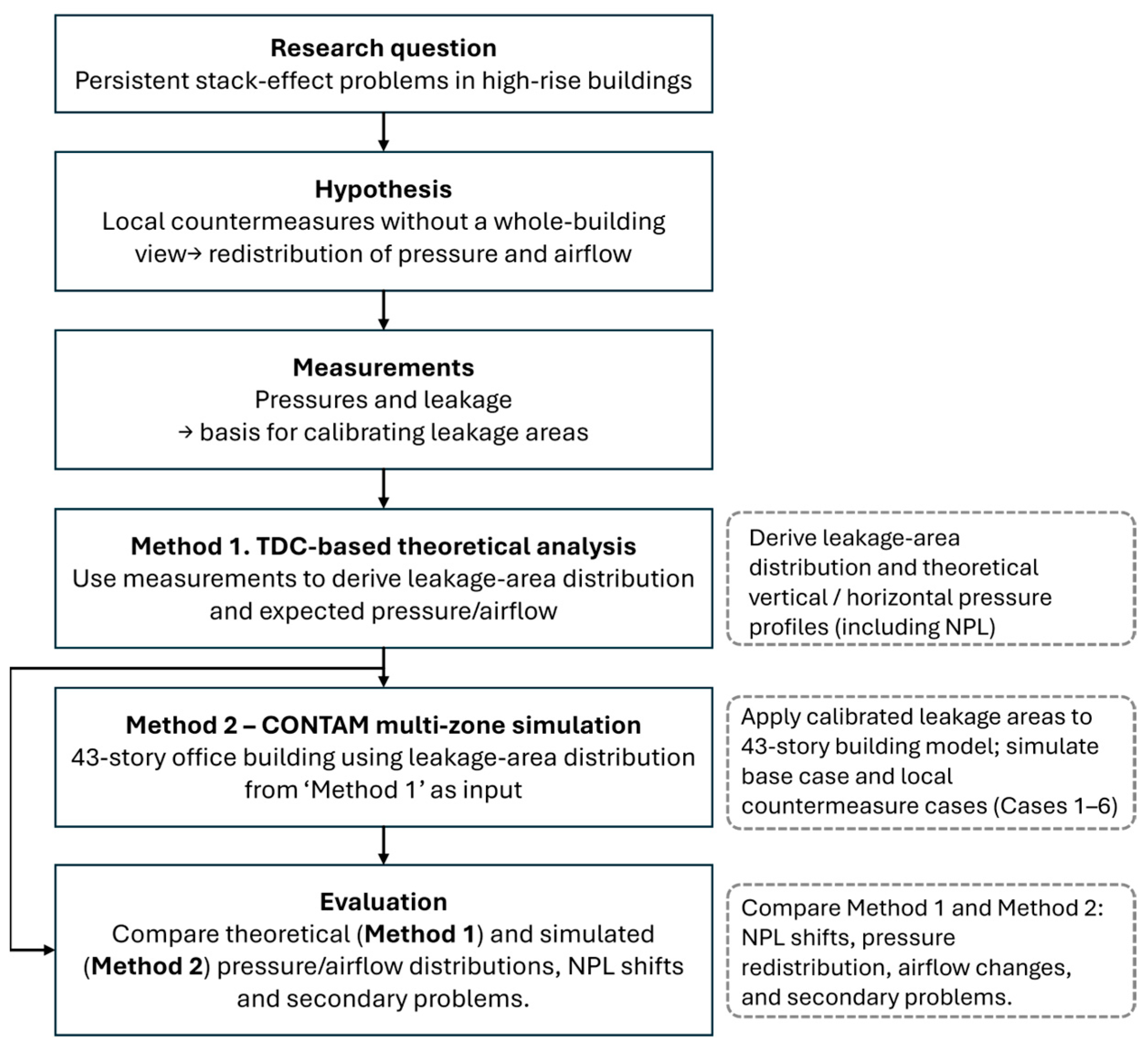

This study aims to address these research gaps by combining theoretical consideration of vertical and horizontal pressure distributions with a calibrated multizone airflow model of a real high-rise office building. A CONTAM model of an existing 43-story office building is developed and calibrated using measured pressure distributions on a representative floor and measured airtightness (equivalent leakage areas) for selected divisions, including exterior walls and elevator doors. Using this calibrated model, we analyze how conventional local stack-effect countermeasures influence the building-wide pressure field, including NPL shifts and redistribution of pressure differences among compartments. The main contributions of this work are threefold. First, we quantify the characteristics and variations of vertical and horizontal pressure distributions under stack effect in an actual high-rise building using a measurement-calibrated multizone model. Second, we evaluate the effectiveness of local countermeasures not only at the target location but also at the scale of the entire building, explicitly considering NPL movement and pressure redistribution, and we identify secondary problems arising in zones where no countermeasure is applied. Third, based on these analyses, we propose a building-wide, interconnected application strategy for local countermeasures that mitigates stack-effect problems while minimizing unintended NPL shifts and secondary adverse effects.

3. Theoretical Analysis of Pressure Distribution Under the Stack Effect

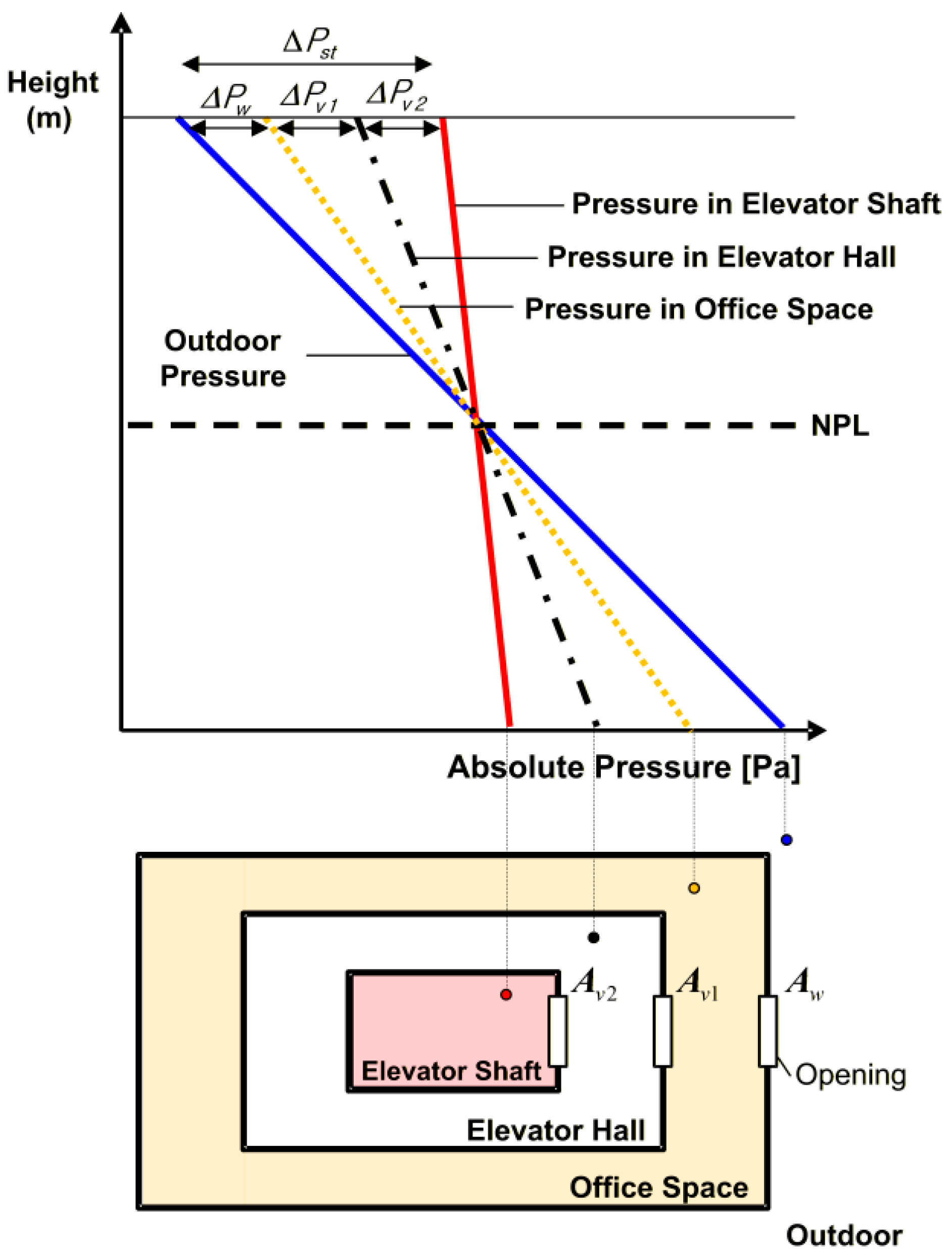

3.1. Vertical Pressure Distribution and Variation

As shown in

Figure 2, the vertical pressure distribution in a building under the stack effect is governed by the location of the neutral pressure level (NPL) and the indoor–outdoor temperature difference. At the NPL, the indoor and outdoor absolute pressures are equal; above and below this level, their magnitude relation is reversed.

In

Figure 2, Q

in and Q

out denote the air inflow and outflow rate (m

3/s), α

A1 and α

A2 are the equivalent leakage areas (m

2), and Δ

P1 and Δ

P2 are the corresponding pressure difference (Pa). In an actual building, an NPL is formed in each vertical shaft, and its height is determined by the level at which the total inflow to the shaft equals the total outflow. Hence, the NPL location is fundamentally controlled by the vertical distribution of leakage areas.

Equations (1)–(3) express these relationships between airflow rates, leakage areas, and pressure differences in a shaft under stack effect, where ρ is the air density (kg/m

3). When α

A1 is larger than α

A2, the NPL lies in the lower part of the building, and the upper floors are subjected to larger pressure differences than the lower floors. Conversely, when the leakage area below the NPL is larger, the NPL shifts upward, and the lower floors experience larger pressure differences. Therefore, any change in the equivalent leakage area in a particular region, or any other factor that modifies the airflow balance above and below the NPL, will shift the NPL and alter the vertical pressure distribution.

The gradients of indoor and outdoor absolute pressure are determined by their respective air temperatures, so the same indoor–outdoor pressure difference occurs at the same vertical distance from the NPL, regardless of the absolute height of the NPL. In the target 43-story office building, these principles are applied mainly to the high-rise elevator shaft, which has its own NPL and dominates the stack-effect problems observed at 1 F and 40 F.

3.2. Horizontal Pressure Distribution and Variation

The horizontal pressure distribution in a building under the stack effect is determined by the relative ratio of leakage areas among building divisions. To illustrate this,

Figure 3 and Equations (4)–(8) consider a simplified floor divided into the exterior and two interior divisions: the interface between the indoor space and the elevator hall, and the interface between the elevator hall and the elevator shaft.

In these equations, γ is the TDC of the building exterior (-), Aw is the leakage area of exterior wall (m2), Atv is the total leakage area of interior divisions (m2), Av1 and Av2 is the leakage areas of the first interior division and the elevator shaft (m2), ΔPw, ΔPtv, ΔPv1, and ΔPv2 are the corresponding pressure difference (Pa) and ΔPst is the total stack effect pressure (Pa).

Equations (4)–(8) show that the pressure differences acting on each division are functions of the leakage-area ratios. A division with a larger leakage area experiences a smaller pressure difference, whereas a more airtight division bears a larger pressure difference. Thus, by changing the leakage areas (for example, by improving airtightness or introducing an additional partition), the horizontal pressure distribution can be intentionally redistributed, even though the overall indoor–outdoor pressure difference due to the stack effect remains unchanged.

Pressurization or depressurization of a specific space also modifies the horizontal distribution. In this case, pressurized/depressurized space is treated as a separate division, and the pressure differences are repartitioned around it. For example, if the upper indoor space in

Figure 3 is pressurized, the pressure difference between the elevator shaft and the indoor space decreases and is shared between the shaft division and the division between the indoor space and the elevator hall, in the same ratio as before pressurization. At the same time, the pressure difference between the indoor and outdoor air increases and is borne by the exterior wall; in this limiting case, the TDC of the building exterior approaches unity. Introducing additional partitions redistributes the pressure difference across multiple divisions and is therefore an effective way of mitigating stack-effect-related problems in individual divisions.

In the target building, the three divisions in

Figure 3 correspond to the high-rise elevator shaft, the high-rise elevator hall, and the adjacent office/vertical-circulation zones on 1 F and 40 F. The local countermeasures investigated in

Section 4 act by changing the leakage areas or pressures of these divisions, and the simulation results in

Section 5 are interpreted directly using these relationships.

4. Target Building and Simulation Model

4.1. Overview of the Target Building and Observed Stack-Effect Problems

Figure 4 shows a longitudinal section and representative floor plans of the target building: (a) a vertical section illustrating the center core and main vertical shafts; (b) the first-floor plan including the main entrances and elevator halls where severe stack-effect problems have been reported; and (c) the 40th-floor plan, which is used as a reference floor for pressure measurements and for presenting horizontal pressure distributions in

Section 5. The building is a large 43-story office building with 8 basement levels and a total floor area of 196,507 m

2. The main vertical circulation elements consist of passages, passenger, shuttle, and emergency elevators, as well as an emergency stairwell that connects all floors.

The passenger elevators are operated separately for low-rise (1 F–17 F), med-rise (1 F, 17 F–28 F), and high-rise (1 F, 28 F–40 F). The passenger elevator system consists of two pairs of shafts facing each other, with four elevator cars operated in each shaft. The shuttle elevators operate between the B7 and 4 F, and the emergency elevators serve all floors. The target building has a center core plan, an elevator hall, and interior doors are installed on all floors except for the first floor. Revolving doors are installed at the main and secondary entrances on the first floor.

The HVAC system of the target building was originally designed so that normal air conditioning operation would not significantly alter the indoor pressure. The control strategy aims to keep the supply and return airflows on each floor approximately balanced, and no explicit building-pressure tracking is implemented. Therefore, in the simulations, only additional supply and exhaust flows associated with the local countermeasures were specified, while the baseline HVAC operation was assumed to have a negligible net effect on building pressurization. In addition, a public pedestrian passage with a closed roof is installed in the north–south direction between the target building and the annex to the east. Revolving doors are installed at the south and north entrances of the passage.

Since completion, various stack-effect problems have been reported in the building. The most serious symptom has been strong noise in the high-rise elevator hall on the first floor (1 F). Other reported problems include noise and strong wind in the high-rise elevator halls on the upper floors when the doors are opened, incomplete closing of doors between high-rise elevator halls and the interior space, and noise at several interior doors. These problems are all caused by excessive pressure differences and airflow through doors and other openings and are therefore directly related to the equivalent leakage areas of the corresponding divisions.

4.2. Measurements for Calibration of Leakage Areas

To reproduce the actual stack-effect characteristics of the target building, the airtightness of each division was not assumed solely from literature values but was calibrated using field measurements on a reference floor (40 F). On this floor, simultaneous measurements of absolute pressure were carried out for all interior compartments and the outdoor space defined by the floor plan. In addition, leakage tests were performed for part of the exterior envelope. The measurement layout of 40 F and the equipment used for the absolute-pressure and air-leakage tests are illustrated in

Figure 5.

Absolute pressures were measured using an absolute manometer (GE Druck DPI 740; range 75,000~115,000 Pa; accuracy ±0.02% of reading; resolution 1 Pa). Differential pressures were monitored with a multichannel scanner (GL Instrument MANA 2200-ip; scan time 0.1~99 s) and a differential pressure gauge (FCO510; range −20,000~20,000 Pa; accuracy ±0.25% of reading; resolution 0.001 Pa). Leakage tests of the exterior envelope were conducted using a blower-door system (Retrotec 2000 series; fan capacity 10,705 CMH; accuracy 5%), following standard building pressurization and airflow measurement procedures [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

The measured pressures were then combined with the TDC-based theoretical relationships described in

Section 3 to back-calculate the equivalent leakage area of each compartment. In this way, a realistic leakage-area distribution was obtained for the target building. Representative calibrated leakage areas for major components (e.g., exterior wall, revolving doors, automatic doors, elevator doors and stair doors), together with the boundary conditions for the base-case simulation, are summarized in

Table 1. Although a full quantitative validation of all airflow rates was not performed, the predicted NPL locations and airflow directions in each elevator shaft were qualitatively checked on site using simple smoke visualization tests, and the observed flow directions were consistent with the simulation results.

4.3. CONTAM Multizone Simulation Model

A multizone airflow model of the entire building was developed using CONTAM. The zones in the model include office spaces, elevator halls (low-, mid-, and high-rise), elevator shafts, the emergency stairwell, the first-floor lobby, entrance zones, the covered public passage and the basement parking area. The zones are connected by doors, leakage paths and shafts according to the architectural layout of the target building.

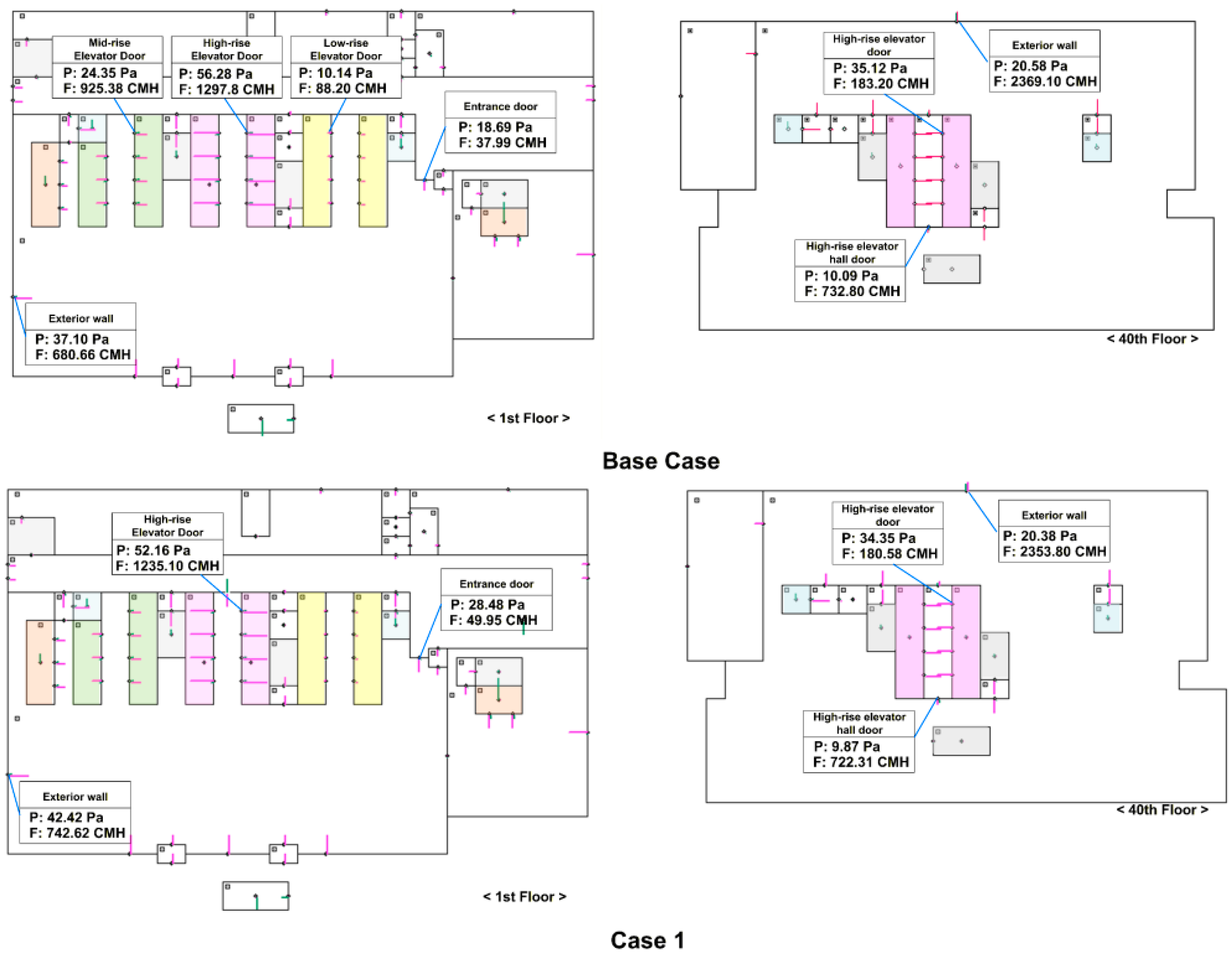

Figure 6 illustrates the CONTAM multizone model on (a) the first floor and (b) the 40th floor. On 1 F, the lobby, vestibules, revolving doors, elevator halls, and entrances are explicitly divided into separate zones, while on 40 F the office zone and the high-rise elevator hall and shaft are modeled in detail. Single doors, revolving doors, and leakage paths are represented as airflow elements between zones.

The leakage area distribution of each boundary surface was implemented in the model based on the calibrated values described in

Section 4.2. The base case indoor temperature was set to the design heating value (24 °C), while the outdoor and underground parking temperatures were set to the measured values (2.5 °C and 15 °C, respectively;

Table 1). As explained in

Section 4.1, the case building is served by a floor-by-floor VAV air-conditioning system that is operated so that the supply and return airflows on each floor are approximately balanced, and the system does not include building-pressure tracking control. Therefore, no net mechanical supply or exhaust flows were imposed on the zones in the base-case model, and the HVAC system was represented only by the additional supply and exhaust flows that implement the local countermeasures described in

Section 4.4 (

Table 2).

Figure 7.

Schematic layouts of local countermeasures: (a) Case 1—exhaust from the 1st-floor high-rise elevator hall; (b) Case 3-1—additional partition at the 1st-floor high-rise elevator hall entrance; (c) Case 3-2—additional partitions at all 1st-floor elevator halls; (d) Case 4—additional supply to 37th–40th-floor high-rise elevator halls; (e) Case 5—duct connection between the high-rise elevator shaft and the 21st-floor mechanical room.

Figure 7.

Schematic layouts of local countermeasures: (a) Case 1—exhaust from the 1st-floor high-rise elevator hall; (b) Case 3-1—additional partition at the 1st-floor high-rise elevator hall entrance; (c) Case 3-2—additional partitions at all 1st-floor elevator halls; (d) Case 4—additional supply to 37th–40th-floor high-rise elevator halls; (e) Case 5—duct connection between the high-rise elevator shaft and the 21st-floor mechanical room.

The simulation for each case was carried out under steady-state conditions using the actual indoor design temperature (24 °C) and the outdoor temperature (2.5 °C) measured when stack-effect problems were observed in the building. No wind pressures were applied; airflow is driven solely by thermal buoyancy due to the indoor–outdoor temperature difference and by the imposed local supply and exhaust flows listed in

Table 2. Under these boundary conditions, CONTAM computes the vertical pressure distribution, including the neutral pressure level (NPL) in each shaft, and the horizontal pressure differences acting on doors and walls at each floor. Thus, pressure differences and airflow rates through each door and leakage path are outputs of the multizone calculation rather than prescribed input settings.

In CONTAM, each leakage path and closed door was modeled as a flow element whose characteristics were defined from the equivalent leakage areas in

Table 1 and the pressure–flow relationships described in

Section 3. The network equations were solved with the standard steady-state solver using default air properties and buoyancy treatment. With the building geometry, thermal boundary conditions (

Table 1), calibrated leakage-area distribution (

Table 1) and case-specific additional flows (

Table 2), the simulations can be reproduced without prescribing any global ventilation airflow rates or pressure setpoints.

4.4. Definition of Local Countermeasure Cases

Local countermeasures were selected to reflect feasible modifications in an occupied building and to address the observed stack effect problems on the first floor and in the high-rise zone. The selected countermeasures and the corresponding simulation cases are summarized in

Table 2. The implementation of the main countermeasures in the CONTAM model is illustrated in

Figure 7 (Case 1:

Figure 7a; Case 3-1:

Figure 7b; Case 3-2:

Figure 7c; Case 4:

Figure 7d; Case 5:

Figure 7e).

Because noise and strong wind at elevator doors on the first floor and on the high-rise floors are caused by airflow through elevator door opening, the main strategy was to reduce the airflow by decreasing the pressure difference across these openings. According to Equation (1), the air through an opening is determined by the opening size and the pressure difference across it. The local countermeasures therefore focus on reducing the pressure difference across elevator doors either by depressurization/pressurization or by redistributing the pressure among additional partitions.

For the high-rise elevator doors on the first floor, two primary approaches were considered:

For the high-rise elevator doors on the upper floors, two additional approaches were examined:

Finally, the influence of opening exterior windows on the stack effect was investigated:

The base case, which represents the current operating condition of the building without any local countermeasures or window openings, was also simulated to provide a reference for comparison.

5. Simulation Results and Discussion

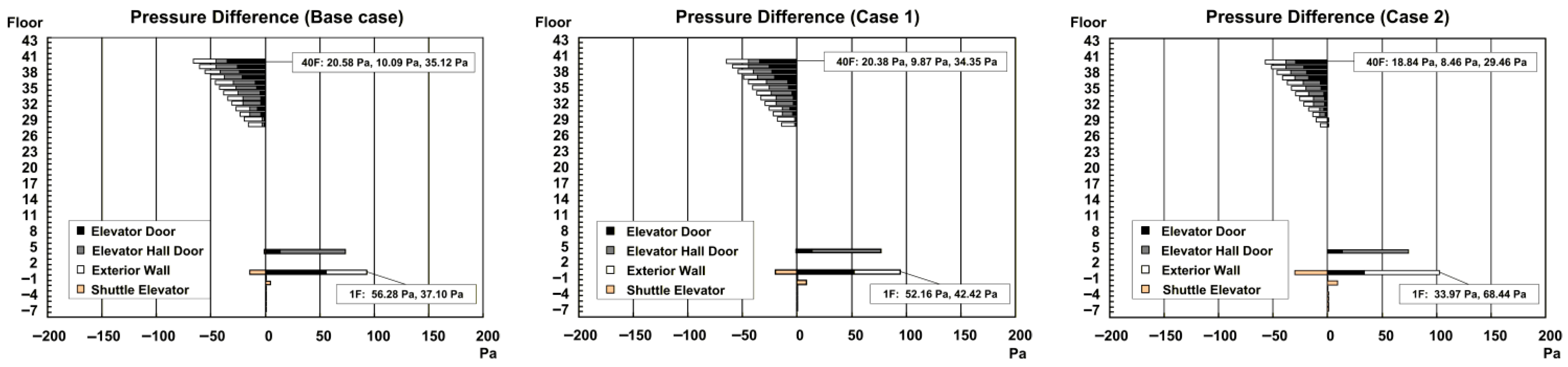

The simulation results were analyzed from three viewpoints:

(i) mitigation of stack-effect problems at the locations where local countermeasures are applied, (ii) occurrence of secondary problems caused by pressure redistribution and neutral pressure level (NPL) shifts, and (iii) the influence of NPL movement on the effectiveness and robustness of each countermeasure.

- (a)

the NPL position along the building height for the base case and the corresponding countermeasure cases,

- (b)

the horizontal pressure differences and airflow on the first floor (1 F), and

- (c)

the horizontal pressure differences and airflow on the representative high-rise floor (40 F).

Figure 8.

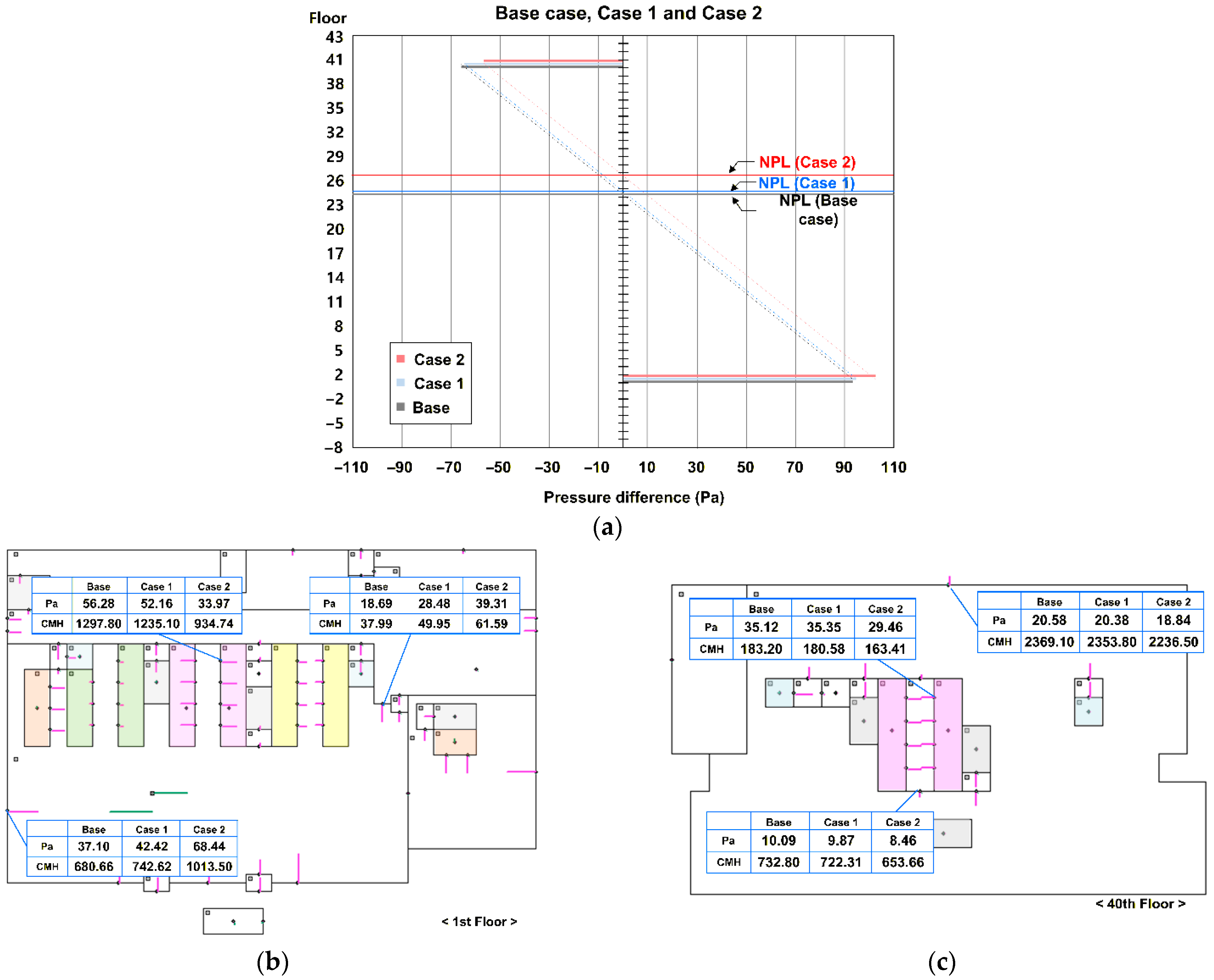

Effects of first-floor depressurization (Cases 1 and 2): (a) NPL in the high-rise shaft; (b) horizontal pressure and airflow on 1 F; (c) horizontal pressure and airflow on 40 F.

Figure 8.

Effects of first-floor depressurization (Cases 1 and 2): (a) NPL in the high-rise shaft; (b) horizontal pressure and airflow on 1 F; (c) horizontal pressure and airflow on 40 F.

Figure 9.

Effects of additional divisions on the first floor (Cases 3-1 and 3-2): (a) NPL in the high-rise shaft; (b) horizontal pressure and airflow on 1 F; (c) horizontal pressure and airflow on 40 F.

Figure 9.

Effects of additional divisions on the first floor (Cases 3-1 and 3-2): (a) NPL in the high-rise shaft; (b) horizontal pressure and airflow on 1 F; (c) horizontal pressure and airflow on 40 F.

Figure 10.

Effects of pressurizing high-rise elevator halls (Case 4): (a) NPL in the high-rise shaft; (b) horizontal pressure and airflow on 1 F; (c) horizontal pressure and airflow on 40 F.

Figure 10.

Effects of pressurizing high-rise elevator halls (Case 4): (a) NPL in the high-rise shaft; (b) horizontal pressure and airflow on 1 F; (c) horizontal pressure and airflow on 40 F.

Figure 11.

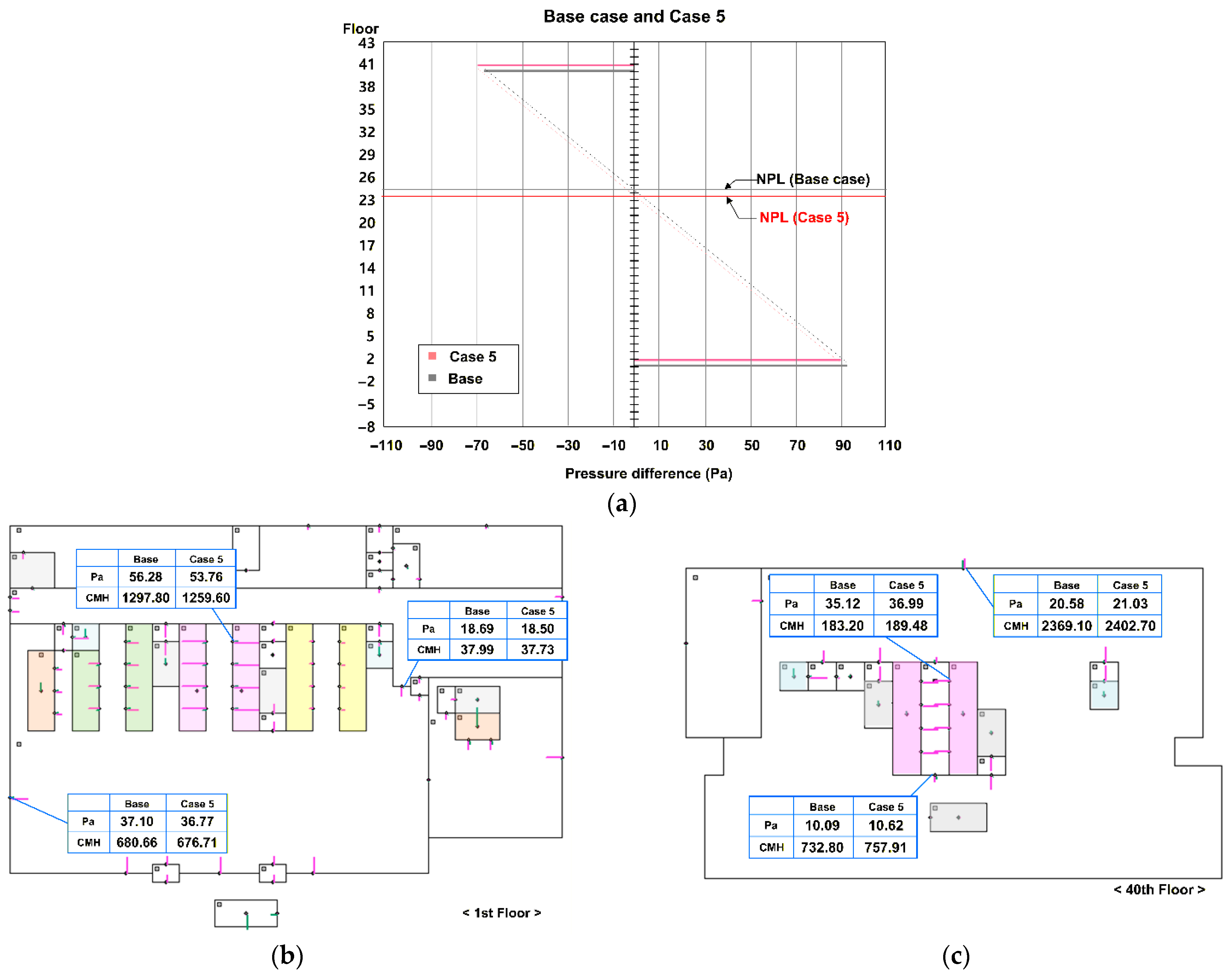

Effects of forced ventilation from the high-rise elevator shaft (Case 5): (a) NPL in the high-rise shaft; (b) horizontal pressure and airflow on 1 F; (c) horizontal pressure and airflow on 40 F.

Figure 11.

Effects of forced ventilation from the high-rise elevator shaft (Case 5): (a) NPL in the high-rise shaft; (b) horizontal pressure and airflow on 1 F; (c) horizontal pressure and airflow on 40 F.

Figure 12.

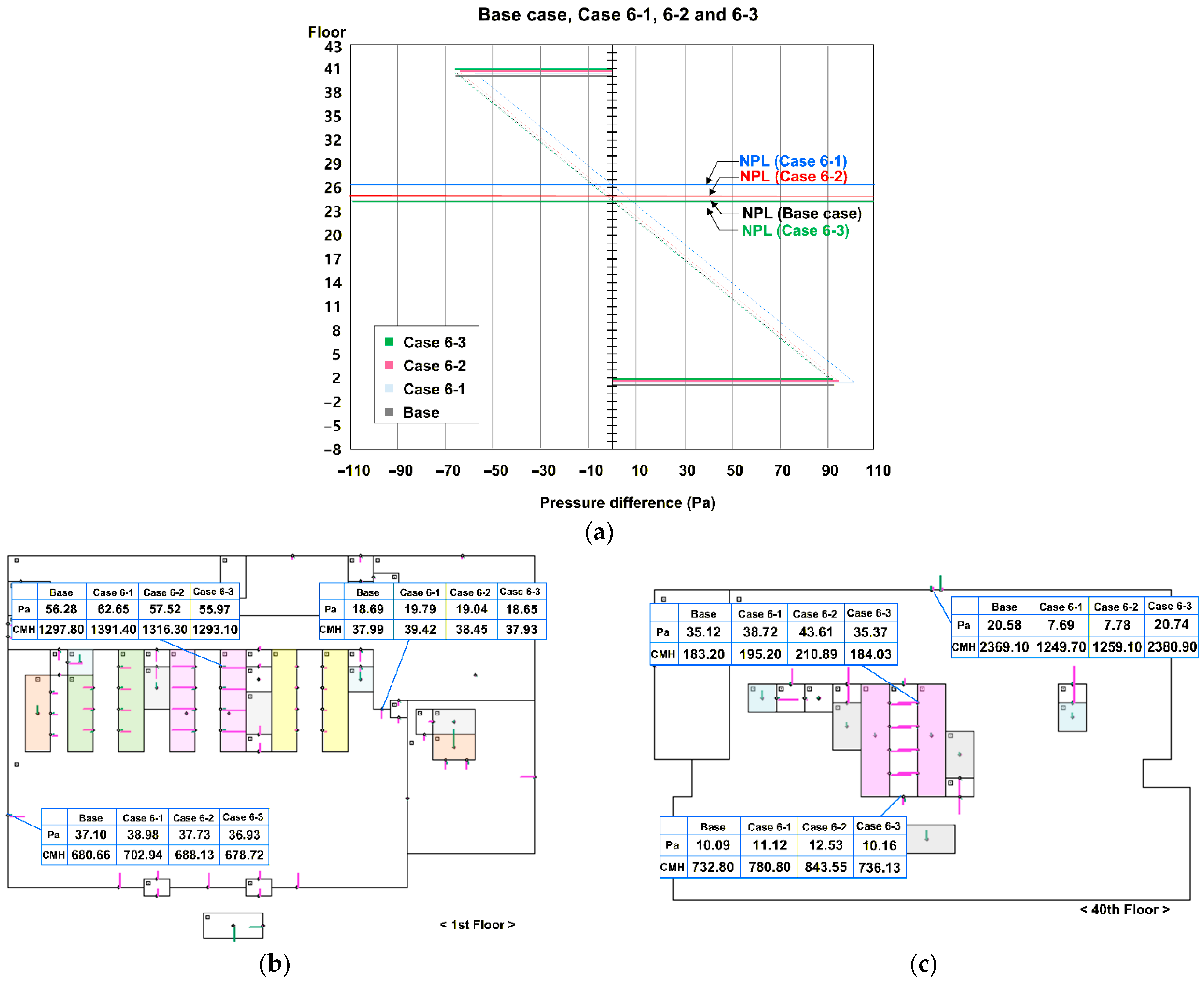

Effects of opening exterior windows (Cases 6-1, 6-2 and 6-3): (a) NPL in the high-rise shaft; (b) horizontal pressure and airflow on 1 F; (c) horizontal pressure and airflow on 40 F.

Figure 12.

Effects of opening exterior windows (Cases 6-1, 6-2 and 6-3): (a) NPL in the high-rise shaft; (b) horizontal pressure and airflow on 1 F; (c) horizontal pressure and airflow on 40 F.

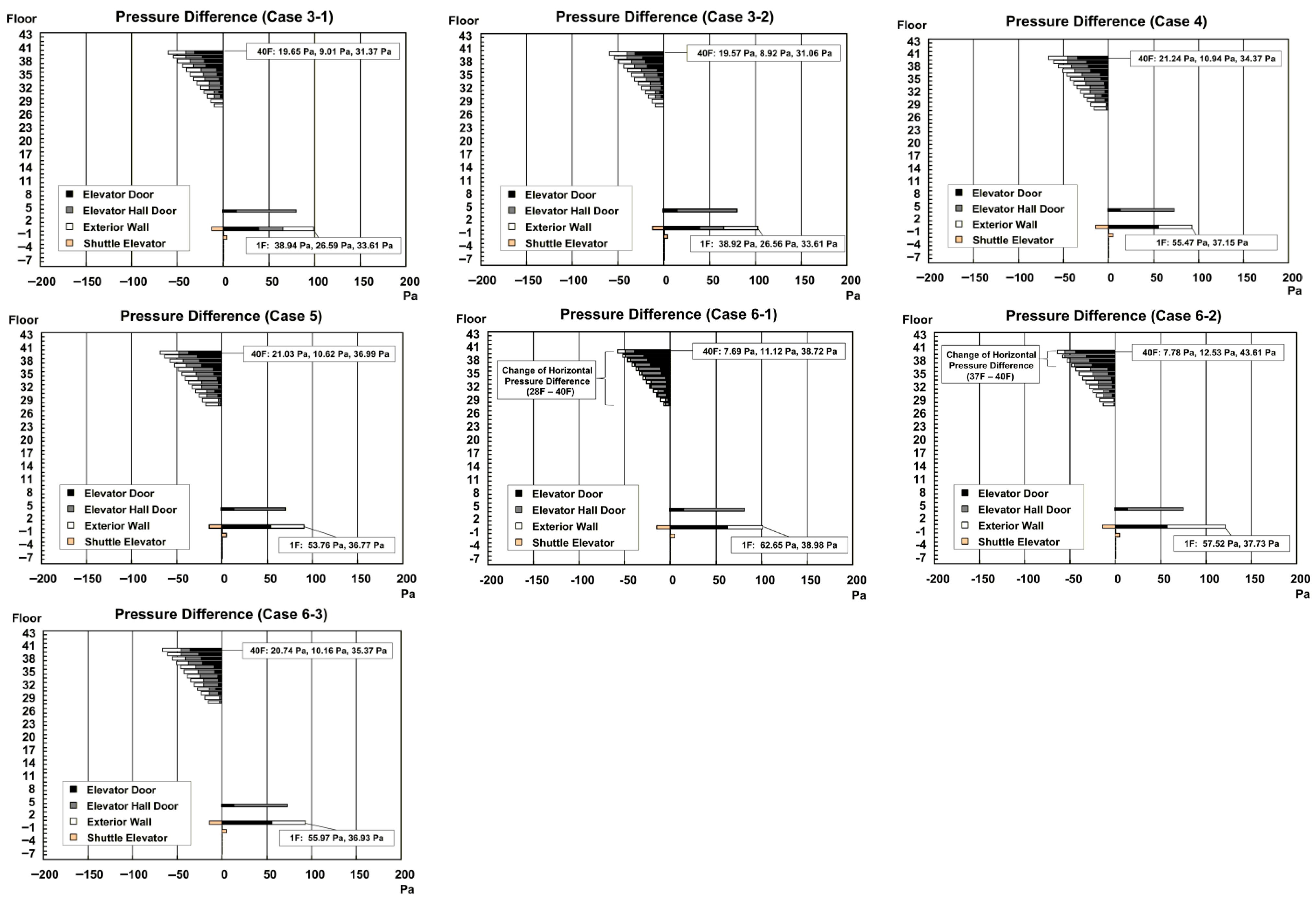

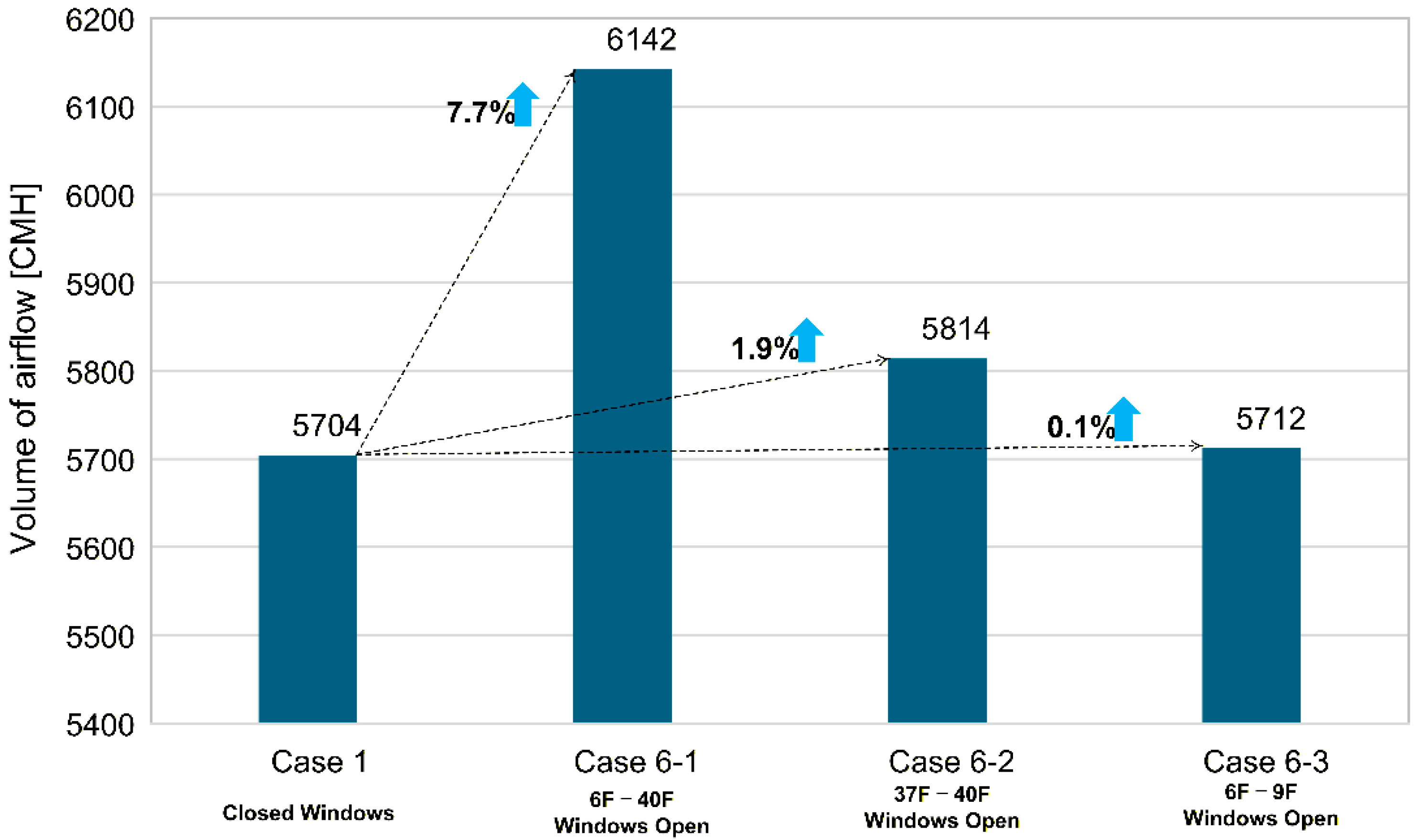

Figure 13 summarizes the airflow rate in the high-rise elevator shaft for the base case and the window-opening cases (Cases 6-1, 6-2, and 6-3). More detailed vertical and horizontal pressure distributions for individual cases are provided in

Appendix A for reference, but are not required to follow the main discussion.

5.1. Effect of Depressurization on the First Floor (Cases 1 and 2)

When the high-rise elevator hall and/or the lobby on 1 F are depressurized (Cases 1 and 2), the pressure difference between the high-rise elevator hall and the high-rise elevator shaft on 1 F decreases compared with the base case (

Figure 8b). In other words, the pressure difference acting on the high-rise elevator doors on 1 F is reduced. This means that the application of these countermeasures mitigates the stack-effect problems at the first floor, such as noise and strong wind when the elevator doors are opened.

However,

Figure 8b also shows that the pressure difference acting on the exterior wall and the entrance doors on 1 F increases. Because depressurization forces a redistribution of pressures among divisions, secondary stack-effect problems such as increased noise and drafts at the entrance door are likely to occur.

Figure 8a,c indicate that depressurization on the first floor reduces the pressure differences acting on the high-rise floors. This reduction is associated with an upward shift in the NPL in the high-rise elevator shaft. The NPL rises because the depressurization on 1 F reduces the air inflow into the shaft, and the vertical pressure balance is re-established at a higher level. Such an upward shift in the NPL can decrease stack-effect problems on the high-rise floors; however, it also reduces the effective pressure difference at 1 F, so the mitigation effect obtained by depressurization on the first floor becomes smaller.

A comparison of Cases 1 and 2 shows that the stronger depressurization applied in Case 2 results in larger variations in pressure differences in each part of the building (

Figure 8a–c). Larger variations can mean higher effectiveness in mitigating the problems at the target location, but it should be noted that the possibility of secondary problems due to pressure transfer also increases.

5.2. Effect of Additional Divisions on the First Floor (Cases 3-1 and 3-2)

The effect of additional partitions on the first floor is shown in

Figure 9, which compares the base case with Case 3-1 and Case 3-2.

Figure 9a presents the NPL height in the high-rise shaft, and

Figure 9b,c show the horizontal pressure differences and airflow on 1 F and 40 F, respectively.

Figure 9b shows that installing an additional division at the entrance of the high-rise elevator hall on 1 F (Case 3-1) reduces the pressure difference acting on the high-rise elevator doors on the floor. Because the additional division shares the pressure difference between the high-rise elevator hall and the high-rise elevator shaft, the pressure difference acting on the exterior wall of 1 F also decreases.

However, pressure transfer between elevator shafts can cause secondary problems. In Case 3-1, the additional division is installed only at the entrance of the high-rise elevator hall, and this configuration increases the absolute pressure in the main lobby. As a result, the pressure differences acting on the mid-rise and low-rise elevator doors become larger (

Figure 9b), and these doors may suffer from increased noise, strong wind and incomplete closure.

In Case 3-2, additional partitions are installed at the entrances of all elevator halls on 1 F (low-, mid- and high-rise). As shown in

Figure 9b, this configuration distributes the pressure differences more evenly among the elevator shafts and the lobby and reduces the pressure differences acting on the mid-rise and low-rise elevator doors compared with Case 3-1. These results emphasize that when an additional division is installed to distribute pressure, pressure transfer on the same partition line, including all shafts connected to that line, must be considered.

Figure 9a,c show that the additional divisions on 1 F also reduce the pressure difference acting on the high-rise floors. This occurs because the additional divisions reduce the air inflow into the high-rise elevator shaft, and the NPL moves upward. Such a shift in the NPL helps mitigate stack-effect problems at upper floors but, similar to the depressurization cases, tend to reduce the effectiveness of the additional division in mitigating problems on the first floor.

5.3. Effect of Pressurization on High-Rise Floors (Case 4)

The effect of pressurizing the high-rise elevator halls is presented in

Figure 10, which compares the base case with Case 4 (pressurization of the high-rise elevator halls on 37 F–40 F).

Figure 10a shows the NPL height in the high-rise shaft, and

Figure 10b,c show the horizontal pressure differences and airflow on 1 F and 40 F, respectively.

As shown in

Figure 10c, pressurization of the high-rise elevator hall reduces the pressure difference acting on the high-rise elevator doors on the upper floors. However, the pressure difference acting on the doors between the high-rise elevator halls and the interior office spaces increases, because the hall pressure is raised relative to the interior. If the pressure difference acting on these hall doors increases, the air leakage volume through the door gaps also increases, which can result in noise, strong wind during door operation and incomplete door closure.

Figure 10a,b show that, when the high-rise elevator hall is pressurized, the pressure differences acting on each division of 1 F decrease because the NPL in the high-rise shaft moves downward. As the airflow from the shaft into the pressurized halls decreases, the shaft draws relatively more air from lower levels, and the NPL descends. Such a downward shift in the NPL increases the original stack-effect pressure acting on many high-rise floors; thus, the effectiveness of pressurization in mitigating problems is reduced.

In summary, stack-effect problems are mitigated on some floors where the elevator halls are directly pressurized, but the downward movement of the NPL increases the pressure differences and airflow on other floors, particularly non-pressurized floors above the new NPL, so that new secondary problems may occur.

5.4. Effect of Forced Ventilation from the Elevator Shaft (Case 5)

The effect of forced ventilation from the high-rise elevator shaft is shown in

Figure 11, which compares the base case with Case 5. In Case 5, the high-rise elevator shaft is connected to the mechanical room on 21 F by a duct in order to exhaust air from the shaft.

Figure 11a shows the NPL height for the base case and Case 5, and

Figure 11b,c show the horizontal pressure differences and airflow on 1 F and 40 F, respectively. When separate ventilation is applied through duct, the pressure difference at each division on the high-rise floors, where the countermeasure was intended to mitigate the problems, increase while the pressure differences on 1 F decrease (

Figure 11b,c). This behavior is the opposite of the original design intent.

This unexpected result occurs because the NPL of the shaft moves downward (

Figure 11a). The downward shift in the NPL indicates that airflow occurs from the mechanical room on 21 F to the high-rise elevator shaft through the duct, rather than from the shaft to the mechanical room. In other words, the duct behaves as an unintended air-supply path. Considering that the ventilation opening was located below the original NPL, this design fails to realize the intended exhaust flow. To achieve forced ventilation from the shaft, the duct connection must be located above the NPL.

Furthermore, if airflow is directly supplied to or exhausted from the elevator shaft to reduce the pressure difference through the movement of the NPL, the vertical pressure distribution changes significantly, which can result in secondary problems in other divisions. When controlling the NPL of an elevator shaft is considered to mitigate stack-effect problems, improvements in airtightness, additional divisions and other measures that restrict airflow in the shaft are more effective than direct supply and exhaust from the shaft in preventing secondary problems.

5.5. Effect of Opening Exterior Windows (Cases 6-1, 6-2, and 6-3)

The effect of opening exterior windows is summarized in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13.

Figure 12a shows the NPL height in the high-rise elevator shaft for the base case and Cases 6-1, 6-2 and 6-3, and

Figure 12b,c show the horizontal pressure differences and airflow on 1 F and 40 F, respectively.

Figure 13 presents the airflow rate in the high-rise elevator shaft for the same set of cases.

As shown in

Figure 12c, when the exterior windows are opened on floors where the high-rise elevator is available (Cases 6-1 and 6-2), the horizontal pressure distribution on those floors changes significantly owing to the change in the leakage area of the exterior wall. As the exterior windows are opened, the relative leakage area of the exterior wall increases on each floor, most of the stack-effect pressure difference that previously acted on exterior wall is transferred to the elevator shaft and elevator hall. Consequently, the pressure differences increase on both the elevator doors and elevator hall doors, which can increase the severity and probability of stack-effect problems.

Figure 12a,b also show that, when windows are opened in the high-rise zone, NPL of the high-rise elevator shaft moves upward, and the pressure differences on 1 F increase. This effect can increase the severity and probability of secondary problems at the entrance level. However, the upward shift in the NPL tends to reduce the pressure differences on certain high-rise floors (

Figure 12c), which may reduce the possibility of problems on those specific floors.

In Case 6-3, the exterior windows are open only on other floors where the high-rise elevator is not available. In this case, no significant impact on the service area of the high-rise elevator is indicated in

Figure 12b,c. Because each elevator shaft is connected on 1 F and the transfer floors (17 F and 28 F), some pressure transfer between shafts still occurs; however, the changes in the NPL of the high-rise shaft and the resulting pressure differences in each part of the building are relatively small.

Figure 13 shows the air flow rate in the high-rise elevator shaft under the different window-opening conditions. The airflow rate increases dramatically as more exterior windows are opened. When the same number of exterior windows is opened, the increase in airflow is much greater when the windows are opened on high-rise floors (Case 6-2) than when they are opened on lower floors (Case 6-3). This result indicates that window opening within the high-rise service zone strongly enhances the stack effect and airflow through the shaft.

Overall, these results suggest that opening exterior windows under winter conditions not only increases the severity and likelihood of stack-effect problems but also increases uncontrolled air exchange in the building, which is unfavorable from an energy-efficiency perspective. Therefore, especially when stack-effect problems are observed, it is essential to restrict the opening of exterior windows, particularly on floors connected to major vertical shafts, for both effective stack-effect control and energy-efficient building operation.

5.6. Discussion on Limitations and Applicability

The simulations in this study were performed under steady state winter conditions corresponding to the actual case building (indoor 24 °C and outdoor 2.5 °C), with all doors and windows closed. Wind pressure, door opening behavior and active pressure control by the HVAC system were not explicitly modeled. Under these assumptions, the absolute values of pressure difference and airflow would change in other climates, operating conditions or control strategies.

The case building uses a floor-by-floor VAV system that is commissioned so that supply and return airflows are approximately balanced and building pressure is kept close to neutral during normal operation. In this situation, previous studies on tall buildings have reported that stack effect pressure differences are governed mainly by buoyancy and leakage, while mechanical ventilation becomes dominant when there is an intentional imbalance between supply and exhaust airflows or active pressure control. For buildings that operate with unbalanced ventilation, strong wind effects or building pressure control, the quantitative results should therefore be recalculated with an appropriate multizone model.

Even so, the main mechanisms identified in this study remain qualitatively valid. Changes in shaft airflow led to movement of the neutral pressure level, and local countermeasures cause redistribution of pressure between connected compartments. The results suggest that countermeasures should be planned at the scale of the whole building, that neutral pressure level movement should be checked explicitly, and that possible secondary problems due to pressure redistribution should be evaluated on all floors connected to major vertical shafts.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the effectiveness and limitations of local countermeasures that are commonly applied to mitigate stack-effect problems in high-rise buildings. A TDC-based theoretical analysis of vertical and horizontal pressure distributions was combined with a calibrated CONTAM multizone airflow model of a 43-story office building. The model was adjusted using measured pressures and leakage characteristics on a reference floor and then used to evaluate several practical countermeasures, including first-floor depressurization, additional partitions, pressurization of high-rise elevator halls, forced ventilation from the elevator shaft, and opening of exterior windows.

The main findings of this study can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

Local countermeasures reduce stack-effect problems at the treated locations, but they also cause pressure redistribution that can generate secondary problems on other floors or in other compartments.

- (2)

Local measures generally shift the neutral pressure level (NPL) in the vertical shafts, changing the vertical pressure distribution and often weakening the intended mitigation effect.

- (3)

The design of pressure transfer paths (e.g., where pressurization or depressurizations is applied) is critical; if poorly designed, large pressure differences are simply moved to other divisions.

- (4)

Effective mitigation requires coordinated measures at both the upper and lower parts of the building, with the number and strength of local measures chosen according to the resulting reduction in shaft airflow, rather than floor-by-floor fixes.

- (5)

For NPL control in vertical shafts, it is more robust to restrict airflow using improved airtightness and additional partitions than to rely on direct shaft supply/exhaust, which tends to create large pressure changes and secondary problems.

From a practical standpoint, these findings indicate that stack effect control in high-rise buildings should be addressed at the whole building level from the design stage and that remedial local countermeasures in existing buildings should be evaluated with a multizone model to check possible NPL shifts and secondary pressure redistribution before implementation.

This study also has several limitations. First, the simulations were carried out under a single winter condition corresponding to the actual temperature difference observed in the case building (indoor 24 °C, outdoor 2.5 °C) and under steady-state conditions; dynamic variations in ΔT, wind, and occupancy were not considered. Second, wind pressures were not coupled to the model, and equivalent leakage areas were treated as constant values based on measurements with doors and windows closed, so changes in leakage due to door operation were not explicitly modeled. Third, HVAC interactions were simplified: because the air-conditioning system of the case building was designed so that supply and return airflows are approximately balanced, normal HVAC operation was assumed to have a negligible net effect on building pressurization, and only the additional flows associated with the local countermeasures were included in the simulations. This assumption is consistent with previous analyses of tall buildings operated with balanced ventilation, which report that stack-effect pressure differences are primarily governed by buoyancy and leakage unless deliberate supply–exhaust imbalances are introduced [

3,

4,

5]. However, in buildings that employ active building-pressure control or intentionally unbalanced ventilation, mechanical ventilation could partly compensate for or exacerbate stack-effect pressures and dedicated coupled HVAC–multizone simulations would be required. In addition, no separate validation of simulated airflow rates using tracer gas, anemometry, or blower-door tests was performed; instead, the model was calibrated against measured pressure distributions and leakage characteristics on the reference floor.

Finally, this work is a detailed case study focusing on the high-rise elevator shaft and representative upper and lower floors of a single 43-story office building; more systematic and quantitative design guidelines would require analysis covering a wider range of floors, climates, building types, and shaft configurations, including buildings with multiple elevator shafts serving different zones and their mutual interactions. These issues are left as future research topics, and it is hoped that the present results will provide a practical reference for developing more effective stack-effect countermeasures in high-rise buildings.