Abstract

This study numerically investigates the deformation and consolidation behavior of high-water-content river sediment improved by a combined vacuum preloading and internal air-bag pressurization (VPA) system. A 2D axisymmetric finite-element model in Abaqus 2021 with the Modified Cam-Clay constitutive law is established to simulate the treatment process. Key design parameters—air-bag pressure, pressurization timing, embedment depth, and staged loading—are systematically analyzed. Results show that: (1) Under a −80 kPa vacuum, an additional 20 kPa air-bag pressure reduces the maximum inward horizontal displacement by over 20%, while effective stress increases linearly with pressure; (2) Early pressurization (20 days) better controls lateral deformation and accelerates strength gain; (3) Staged pressurization (20 kPa upper, 40 kPa lower) outperforms uniform loading in both displacement control and cost-effectiveness; (4) Compared to 30 kPa surcharge preloading, VPA further reduces horizontal displacement by 10–18% under equivalent total load. The hybrid “vacuum–air-bag–surcharge” scheme yields the highest effective stress and smallest lateral deformation. The VPA method enhances sediment engineering properties, providing a viable approach for resource utilization of dredged materials.

1. Introduction

Converting the vast volume of waste soils generated during construction—such as river-channel dredged sediment—into reusable backfill materials is a pivotal step toward achieving the recycling of waste in material science and building engineering, and is essential for fostering sustainable development and a circular economy in the building sector [1,2]. River sediment, a typical waste rich in clay particles, is characterized by high water content, low permeability, and extremely low strength; it must be effectively dewatered and solidified before it can meet the requirements for engineering backfill [3,4,5]. Owing to its simple operation and relatively low cost, avacuum preloading has been extensively adopted for stabilizing soft soils and hydraulic fills, and it is currently one of the most frequently employed techniques for dewatering and drying river sediment so that it can be reused as a resource [6,7].

However, conventional vacuum preloading exhibits pronounced limitations when applied to the resource treatment of river-channel sediment. Constrained by atmospheric pressure, the vacuum that can be applied theoretically does not exceed 100 kPa and is often markedly lower in the field [8,9]. For deep layers or extremely wet sediments, this stress level is frequently insufficient to dewater the soil to the desired strength, thereby restricting the quality of the recycled backfill [10]. Moreover, the inward contraction of the treated soil during vacuum preloading may induce adverse ground movements in the surrounding area. When addressing realistic boundary conditions and deformation modes in numerical analyses of soil–foundation systems, it is crucial to consider the constraints applied to the model boundaries, as they can significantly influence the computed stress and deformation response [11]. To overcome the vacuum ceiling, various combined improvement schemes—such as vacuum-surcharge preloading [12,13,14,15] and electro-osmosis-vacuum systems [16,17,18]—have been investigated. More recently, vacuum preloading coupled with air-bag pressurization has emerged as a novel technique; flexible air bags installed in advance within the soil are inflated with compressed air to deliver an additional surcharge, effectively elevating the total stress in the improved zone without unduly increasing construction complexity [19].

Although preliminary studies have demonstrated the potential of the Vacuum-Preloading–Air-Bag (VPA) method for improving soil strength and controlling lateral deformation, most existing work is limited to small-scale laboratory tests and macroscopic performance evaluation. Systematic investigations into the detailed deformation characteristics, stress-state evolution, and key influencing factors-such as air-bag pressure, pressurization timing, embedment depth, and loading regime—during VPA treatment of river-channel sediment are still scarce [20,21]. Moreover, finite-element numerical simulation, a powerful tool for elucidating soil consolidation mechanisms, has been rarely applied in this specific field.

Building on previous laboratory investigations, this study establishes a two-dimensional axisymmetric finite-element model using Abaqus 2021 to systematically analyze the deformation behavior and effective-stress evolution during the VPA treatment of river-channel sediment. Particular attention is paid to the influence of air-bag pressure magnitude, pressurization timing, installation depth and staged loading patterns on horizontal ground displacement, and effective stress; the results are compared with those obtained from conventional vacuum preloading and vacuum–surcharge preloading. The outcomes are expected to provide a theoretical basis and design guidance for optimizing VPA technology to promote the resource utilization of river sediment in engineering practice.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 describes the finite-element model, including geometry, boundary conditions, and material parameters; Section 3 presents and discusses the results of parametric studies on air-bag pressure, timing, depth, and staged loading, alongside comparisons with conventional methods; Section 4 concludes with the key findings and their practical implications for optimizing VPA technology in the resource utilization of river sediment.

2. Finite Element Modeling

2.1. Geometric Dimensions and Boundary Conditions

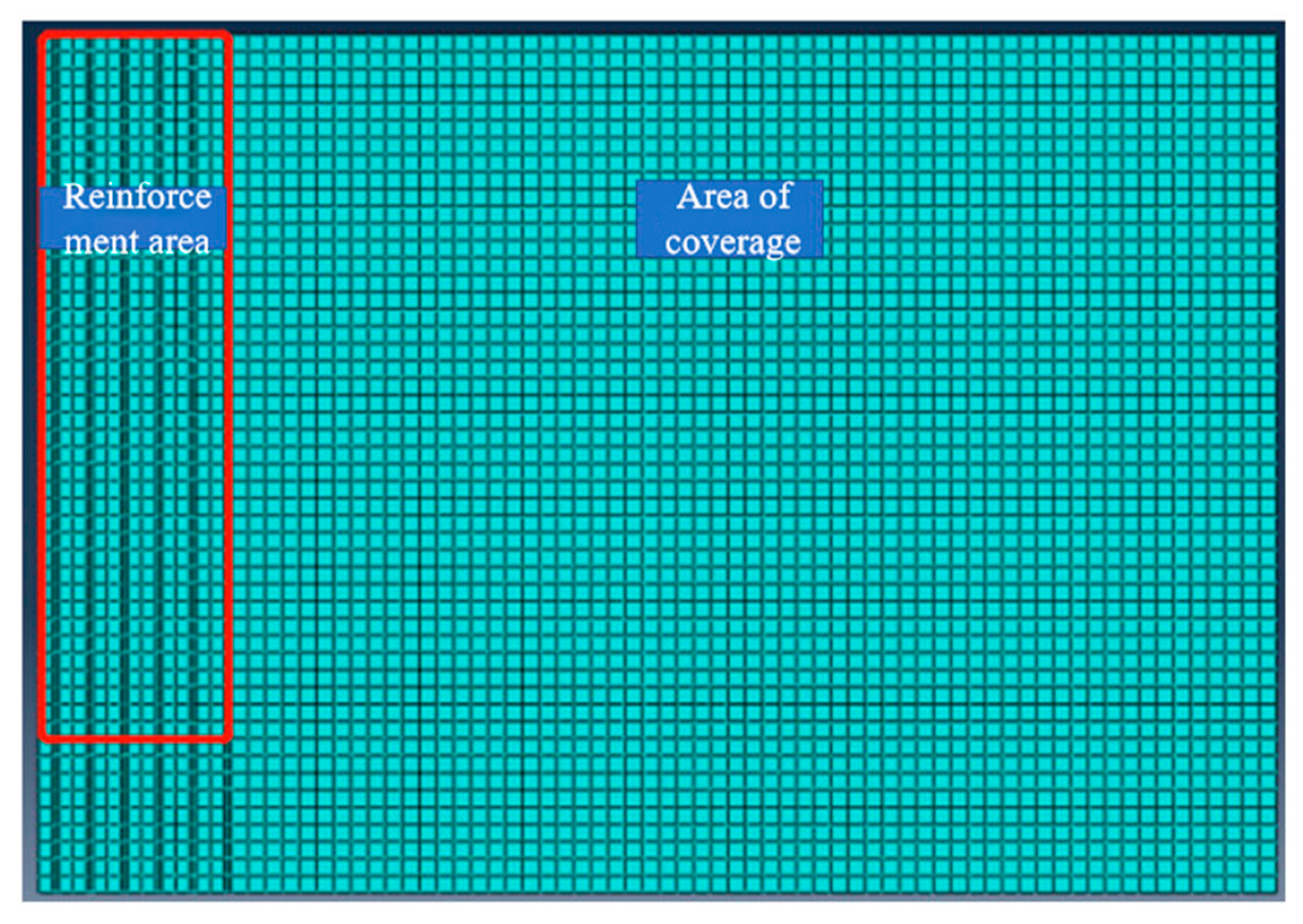

A 2-D axisymmetric model was adopted, representing a cylindrical domain around a single prefabricated vertical drain (PVD). Consequently, only half of the domain was discretized to improve computational efficiency. The mesh spans 36 m in radius (horizontal direction) and 25 m in depth (vertical direction), as shown in Figure 1. This comprises a 6 m radius treatment zone (where the PVDs and air-bag are installed) surrounded by a 30 m wide influence zone. The lateral extent of 30 m was determined through preliminary analyses to ensure that the fixed side boundaries (restrained in the X-direction) do not artificially constrain horizontal displacements, as the deformation and pore pressure changes near these boundaries were negligible.

Figure 1.

Finite-element model diagram.

Prefabricated vertical drains (PVDs) are spaced at 1 m centers and penetrate to a depth of 20 m. In the axisymmetric model, each drain is represented as a continuous line element at a radial distance corresponding to its installation position. A negative pore-water pressure of –80 kPa is applied directly along these drain boundaries to simulate the vacuum condition. The ground surface is a free-draining boundary with pore pressure set to zero. The base of the model is fully fixed (restrained in both X and Y directions), simulating a rigid, impermeable layer.

A smear zone with a radius of 0.2 m (approximately 3 times the equivalent diameter of the drain, which is 0.067 m) is incorporated around each PVD to account for the disturbance during drain installation. Within this smear zone, the horizontal permeability (ks) is reduced to 30% of the undisturbed value (kh), as specified in Table 1. The drain–soil interaction is purely hydraulic via the pore–pressure boundary condition; the structural stiffness of the PVD itself is neglected.

Table 1.

Modified Cambridge model parameters.

2.2. The Basic Properties of Soil and the Determination of Numerical Simulation Parameters

The soil investigated numerically was retrieved from a construction site in Pudong New Area, Shanghai, at a depth of 12.0–15.0 m below ground level. It corresponds to the typical “Fourth Shanghai Layer” of clayey deposits, sampled at coordinates 121°31′19″ N, 31°12′24″ E [19].

The fundamental geotechnical properties of the dredged soil used in this study are summarized as follows. The soil has a liquid limit (wL) of 42.4% and a plastic limit (wP) of 23.6%, with a natural water content (w) of 70%. The specific gravity (Gs) is 2.70, and the bulk density (ρ) is 1.6 g/cm3. The clay-sized fraction (<5 μm) accounts for 44.6% of the particle size distribution. In terms of mechanical and hydraulic behavior, the soil exhibits a compression index (Cc) of 0.35, a vertical hydraulic conductivity (kv) of 2.17 × 10−7 cm/s, and a coefficient of vertical consolidation (cv) of 2.24 × 10−8 cm2/s. These properties are consistent with those reported in the earlier study by Wu et al. (2022) [19].

Because the vacuum preloading method for treating soft ground is essentially a seepage-consolidation problem, the Modified Cam-Clay model is adopted in this study to investigate the deformation behavior and effective-stress evolution of the soil under the combined vacuum–air-bag pressure system. The compression index and swelling/recompression modulus used in the model were obtained from standard oedometer tests conducted in the laboratory. The logarithmic plastic bulk modulus and the critical-state stress ratio are derived from the sum of , . The parameters used for calculation are shown in Table 1.

Although the improved zone (initial void ratio e0 = 1.85) and the surrounding influence zone (e0 = 1.4) have different initial densities, a single set of MCC parameters (λ, κ, M) was applied for simplicity and due to the lack of comprehensive constitutive data for the native soil. This assumption is justified as the primary focus of the study is on the response of the treated dredged sediment, and the influence zone primarily serves to provide a realistic boundary. The parameter e listed in Table 1 represents the initial void ratio (e1) of the soil in the geostatic step.

2.3. Air-Bag Modeling and Loading Scheme

The air bag is modeled as a 0.01 m-thick, highly flexible layer with a minimal elastic modulus of 1 kPa to minimize its structural stiffness impact on the soil. It is represented using compatible quadrilateral elements (CPE4) and is placed mid-span between adjacent drains at a specified depth. The air-bag pressure is applied as a distributed positive pressure on the surface of these bag elements. The term “embedment depth” used throughout this paper refers to the top elevation of the air-bag layer. For example, an embedment depth of 5 m means the top of the air bag is at 5 m below the surface.

The model comprises three analysis steps, one geostatic equilibrium step followed by two soil-consolidation steps: Step 1 establishes geostatic equilibrium, eliminating spurious displacements caused by the soil’s self-weight. Step 2 applies −80 kPa of negative pore–water pressure along the drain boundary, allowing the soil to undergo partial consolidation and gain sufficient strength to sustain the forthcoming positive pressure. Step 3 imposes positive pressure on the air-bag boundary, enabling the soil to continue consolidating under the combined vacuum (negative) and air-bag (positive) pressures; the total treatment period is 100 days.

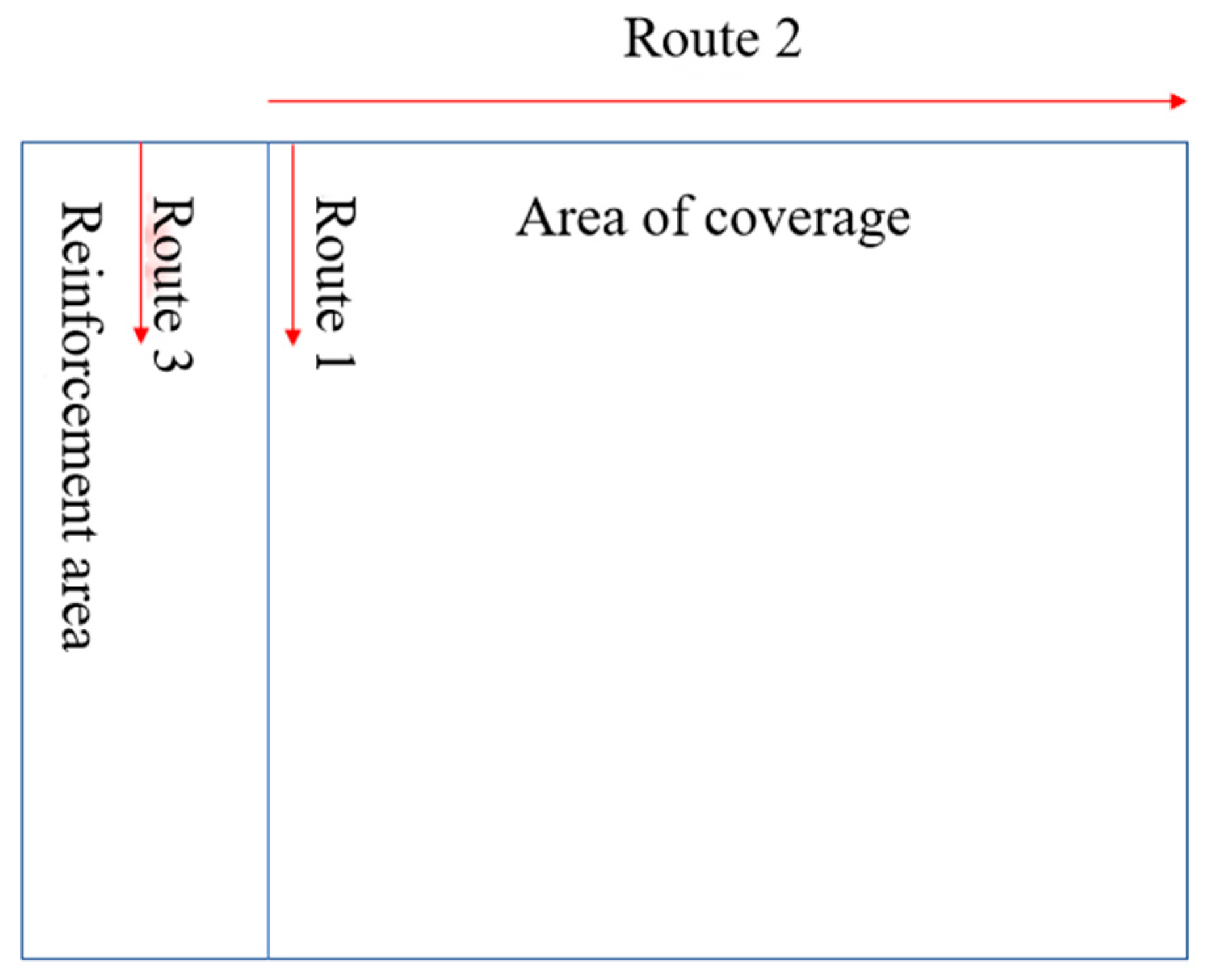

2.4. Selection of Analysis Profile for the Reinforced Soil

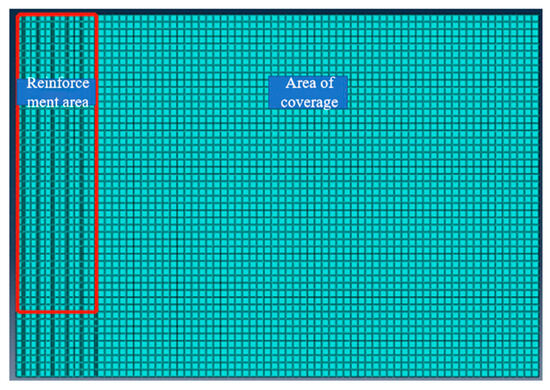

After ground improvement was completed, three representative soil transects were selected to investigate the horizontal displacement and the increase in effective stress under different scenarios. Transect 1 runs through the soil at a certain depth along the edge of the improved zone; Transect 2 lies in the surface layer of the affected area; Transect 3 is located within the improved zone at a specified depth, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Soil analysis route.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Influence of Air-Bag Pressure Magnitude and Pressurization Timing

The magnitude of the air-bag pressure and the timing of its application are key factors governing soil deformation in the proposed method. To quantify their influence on post-improvement lateral deformation and effective stress, four numerical cases—differing in pressure level and pressurization schedule—were analyzed; the details are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cases with Different Air-bag Pressure Levels and Pressurization Times.

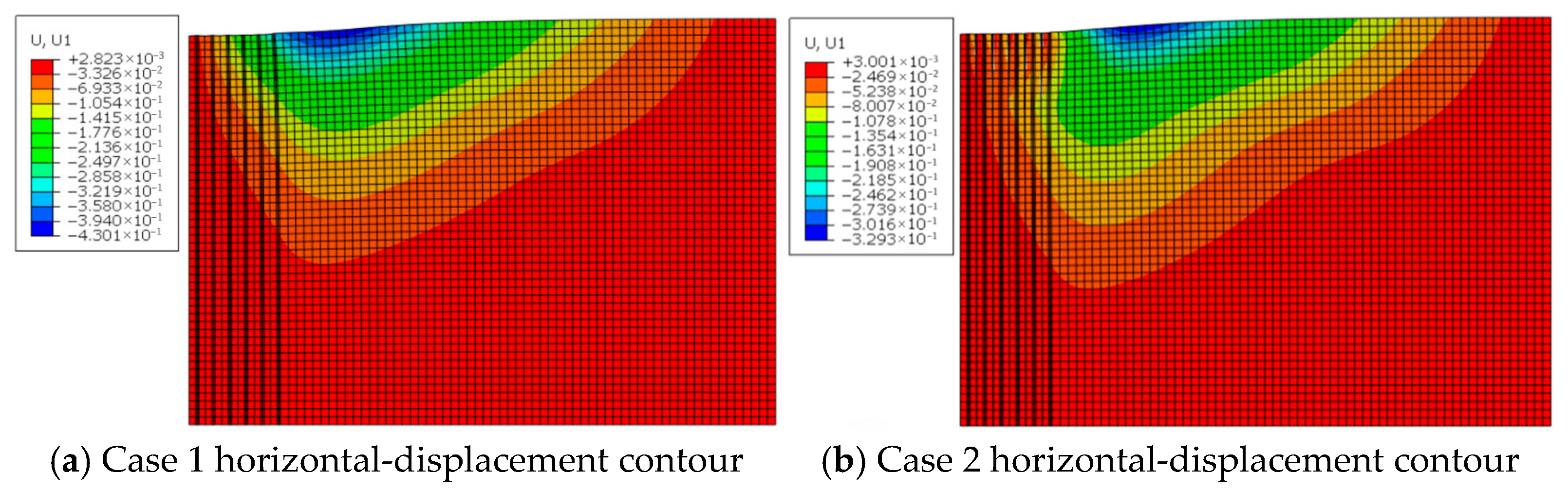

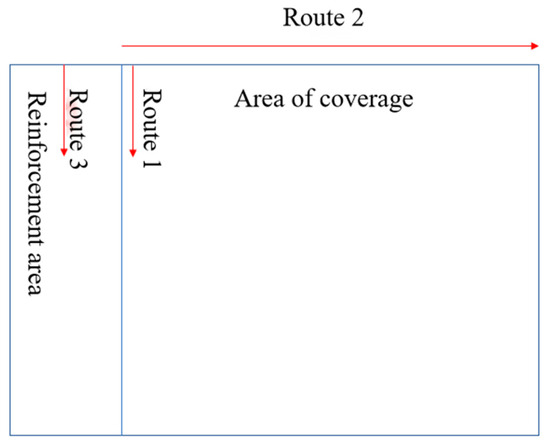

Figure 3 presents the horizontal-displacement contours for Cases 1 and 2 after improvement. Where the air-bag pressure is applied, the inward (negative) horizontal displacements in both the improved zone and the affected area are markedly smaller than those induced by vacuum alone; the reduction is most pronounced at the depth where the air bag is installed. This demonstrates that the lateral expansion generated by the air-bag pressure counteracts part of the inward vacuum-induced contraction, decreasing the inward horizontal displacement by more than 20% in the interval where the maximum negative displacement occurs. Consequently, when lateral deformation of the affected soil must be controlled, the combined vacuum–air-bag system can be adopted to achieve simultaneous ground improvement and restraint of lateral movement.

Figure 3.

Contours of horizontal soil displacement.

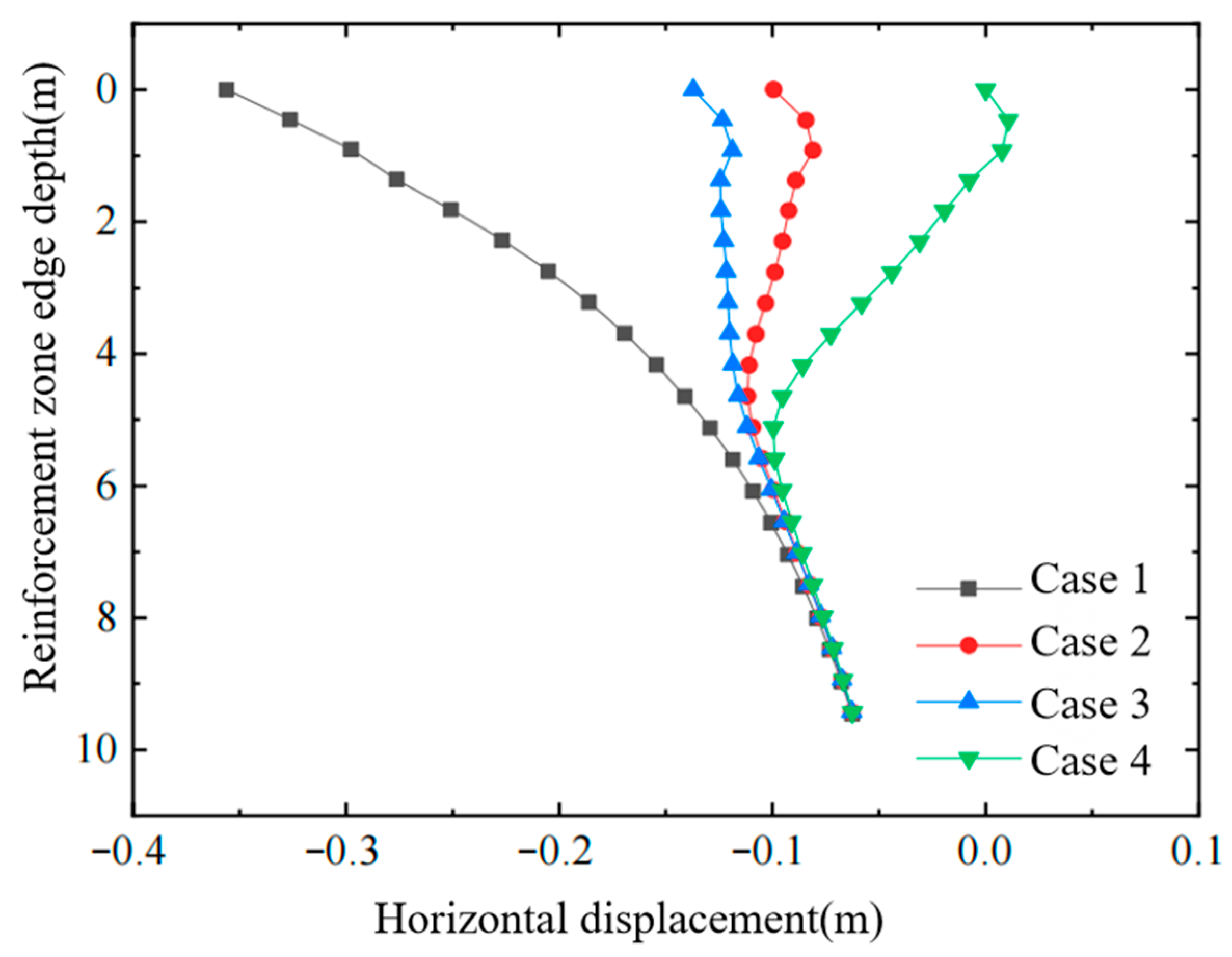

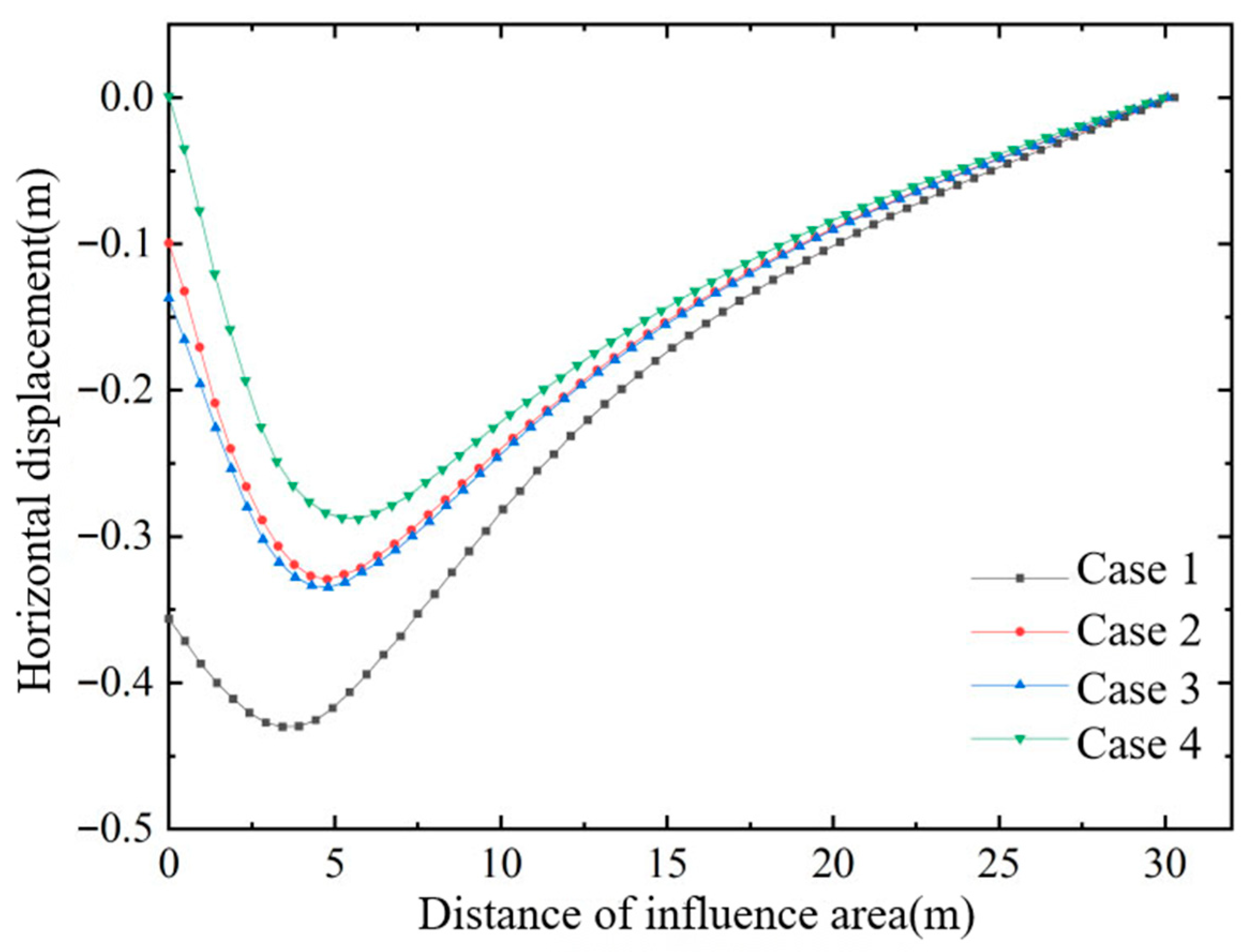

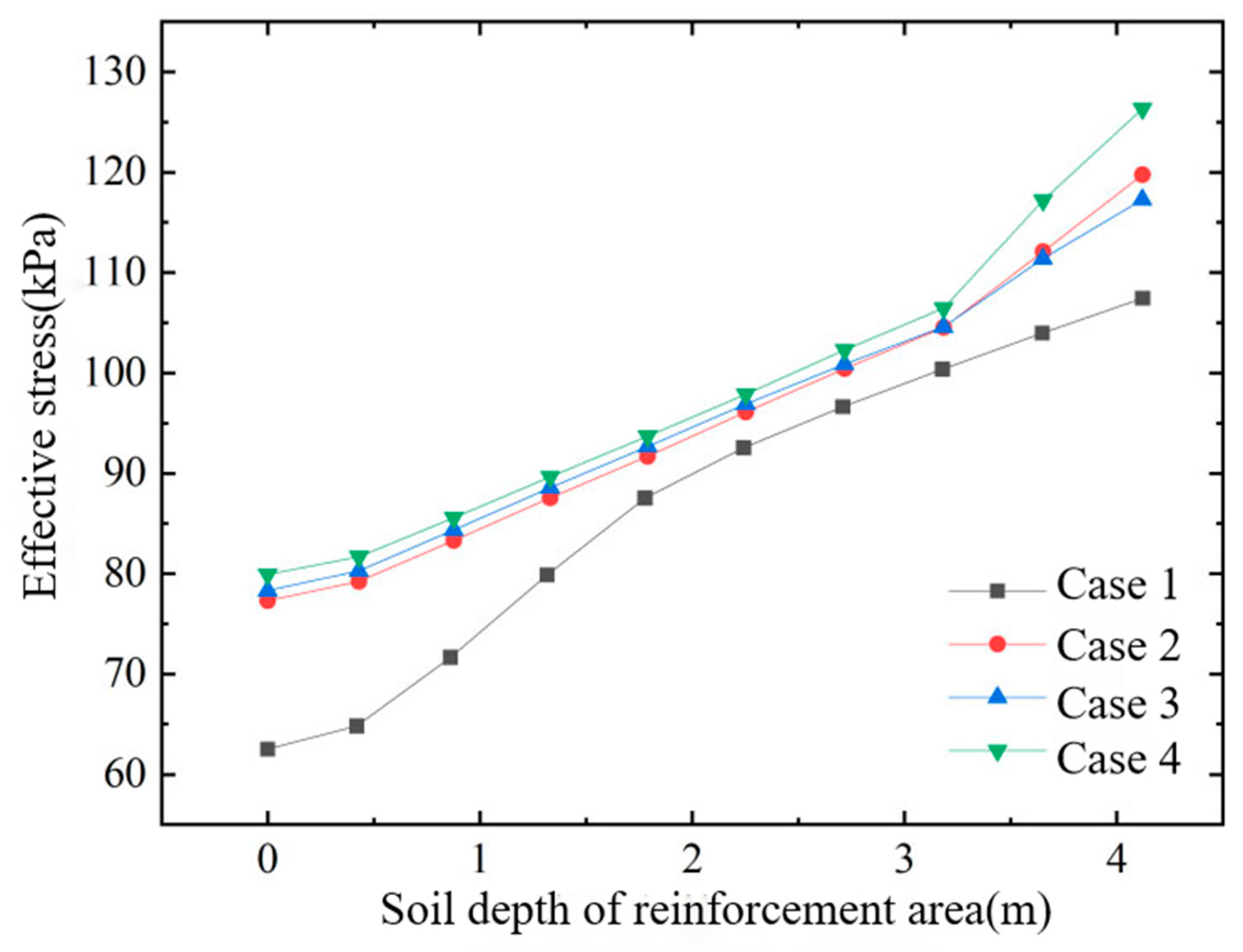

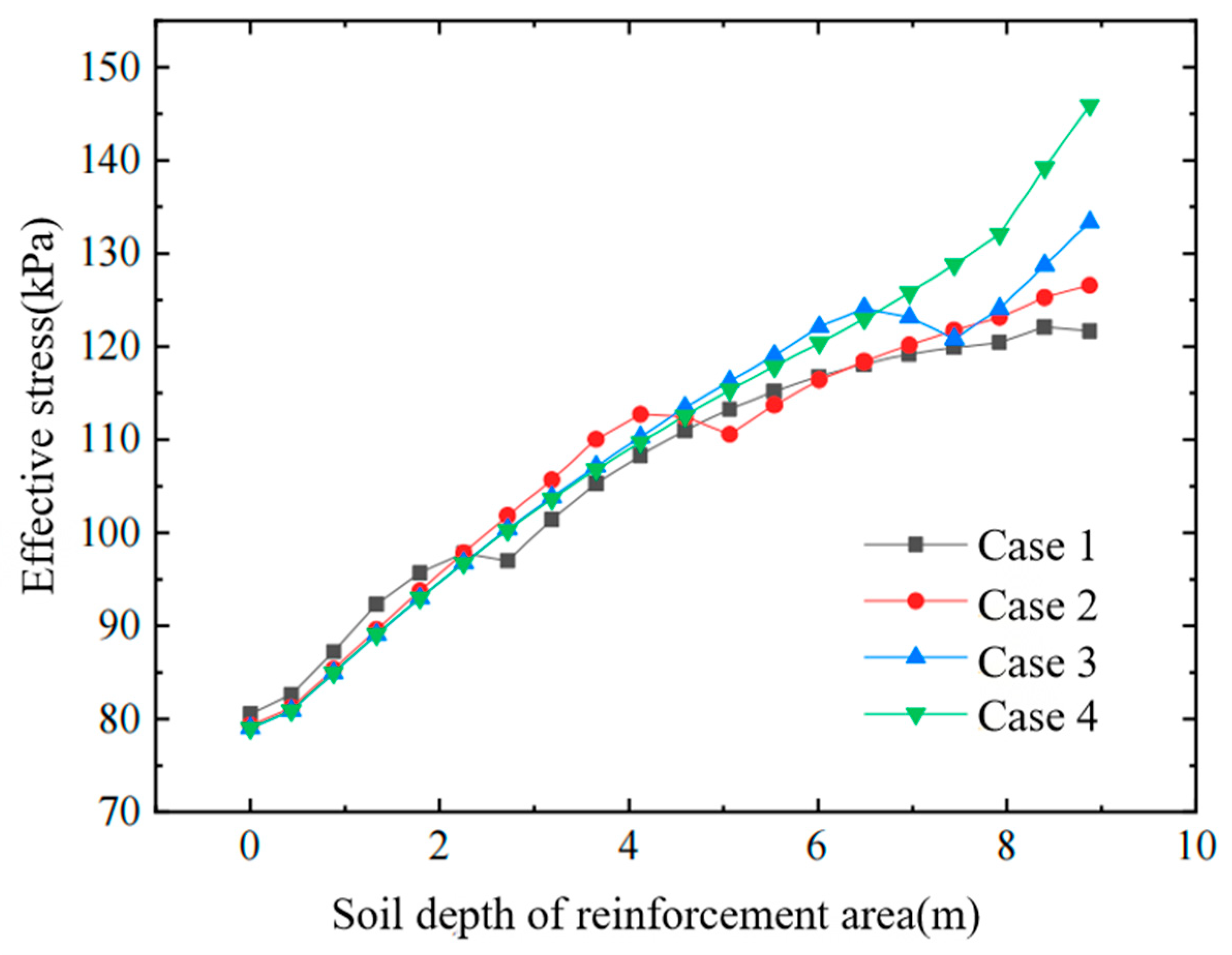

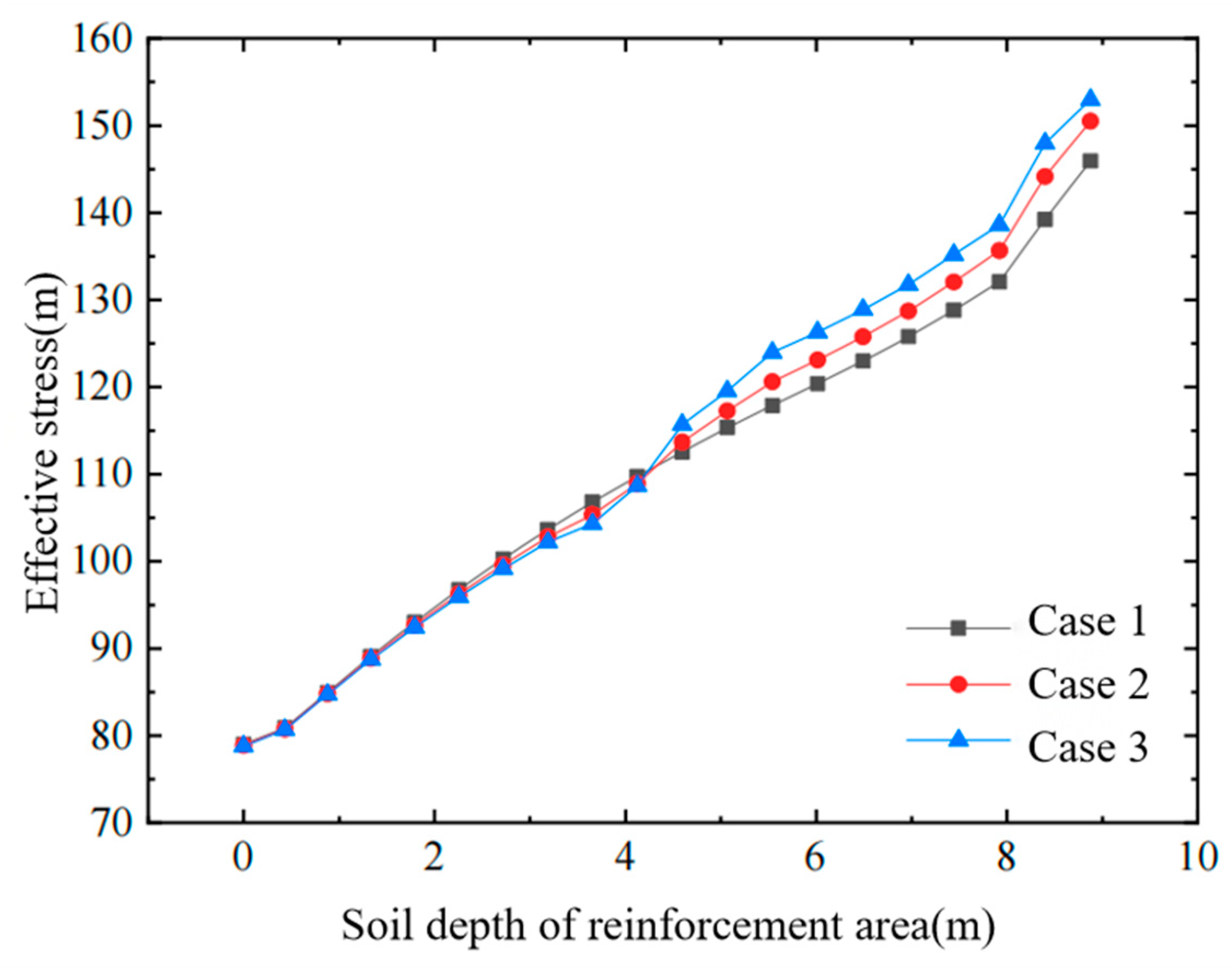

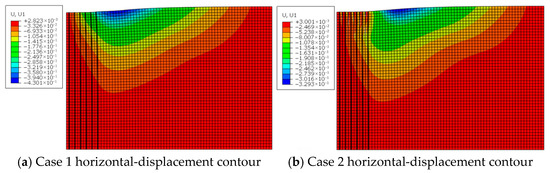

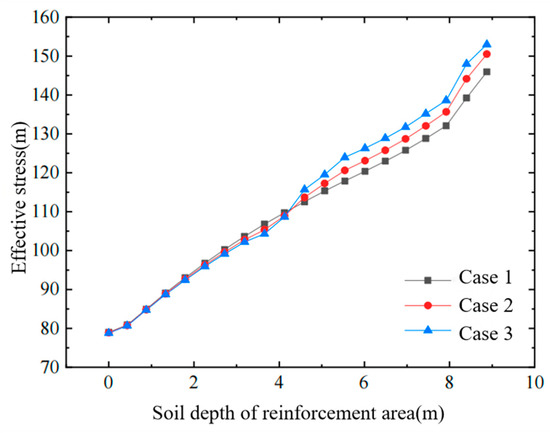

Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 show, respectively, the variation in horizontal displacement with depth at the edge of the improved zone, the variation in horizontal displacement with distance in the surface layer of the affected area, and the variation in effective stress with depth inside the improved zone. From these plots, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Figure 4.

Horizontal displacement of soil at the edge of reinforced area.

Figure 5.

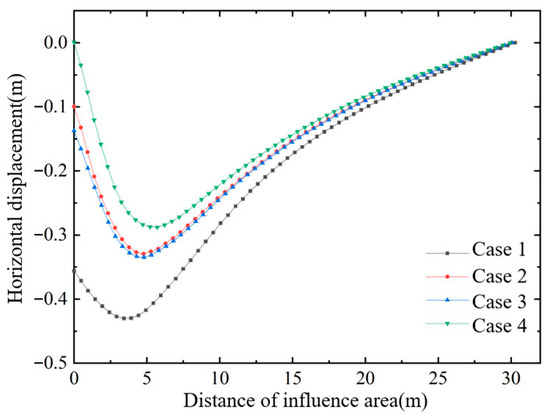

Horizontal displacement of soil in affected area.

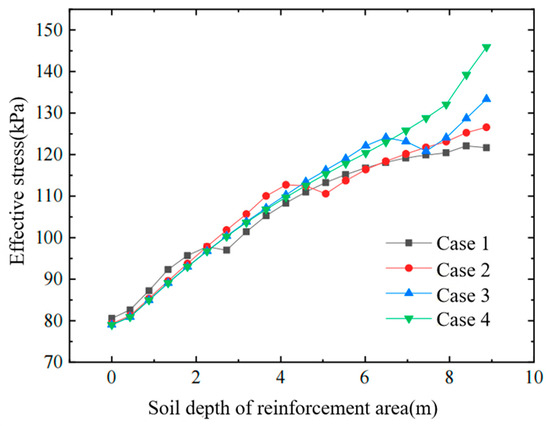

Figure 6.

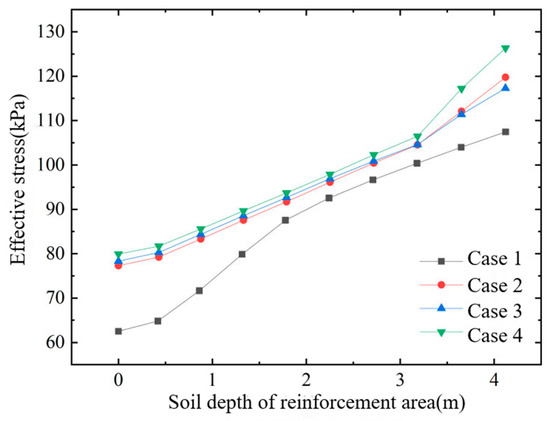

Effective stress of soil in reinforced area.

- (1)

- Conventional vacuum preloading produces large negative horizontal displacements at the edge of the improved zone. The combined vacuum–air-bag method, however, generates a lateral expansion that counteracts part of the vacuum-induced inward force, thereby reducing horizontal deformation and decreasing the negative horizontal displacements in both the improved zone and the adjacent affected area.

- (2)

- As the air-bag pressure increases, the reduction in negative horizontal displacement becomes more pronounced, especially within the depth interval where the bag is installed. Because lateral earth pressure grows with depth, the influence of the air-bag pressure on horizontal displacement gradually diminishes downward and becomes essentially identical below the level of the bag.

- (3)

- The final magnitude of horizontal displacement is closely related to the timing of air-bag pressurization; the earlier the pressure is applied—when the soil’s effective stress is still low—the more pronounced the improvement in horizontal displacement becomes.

- (4)

- At the same depth, the effective stress in the soil increases significantly after air-bag pressurization and rises with the magnitude of the air-bag pressure, thereby enhancing soil strength.

3.2. Influence of Air-Bag Embedment Depth

Lateral displacement of a soil layer results from the cumulative movement of that layer and all underlying strata. To quantify how air-bag embedment depth affects post-improvement lateral deformation and effective stress, four numerical cases with different bag depths were analyzed; the details are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cases with different air-bag embedment depths.

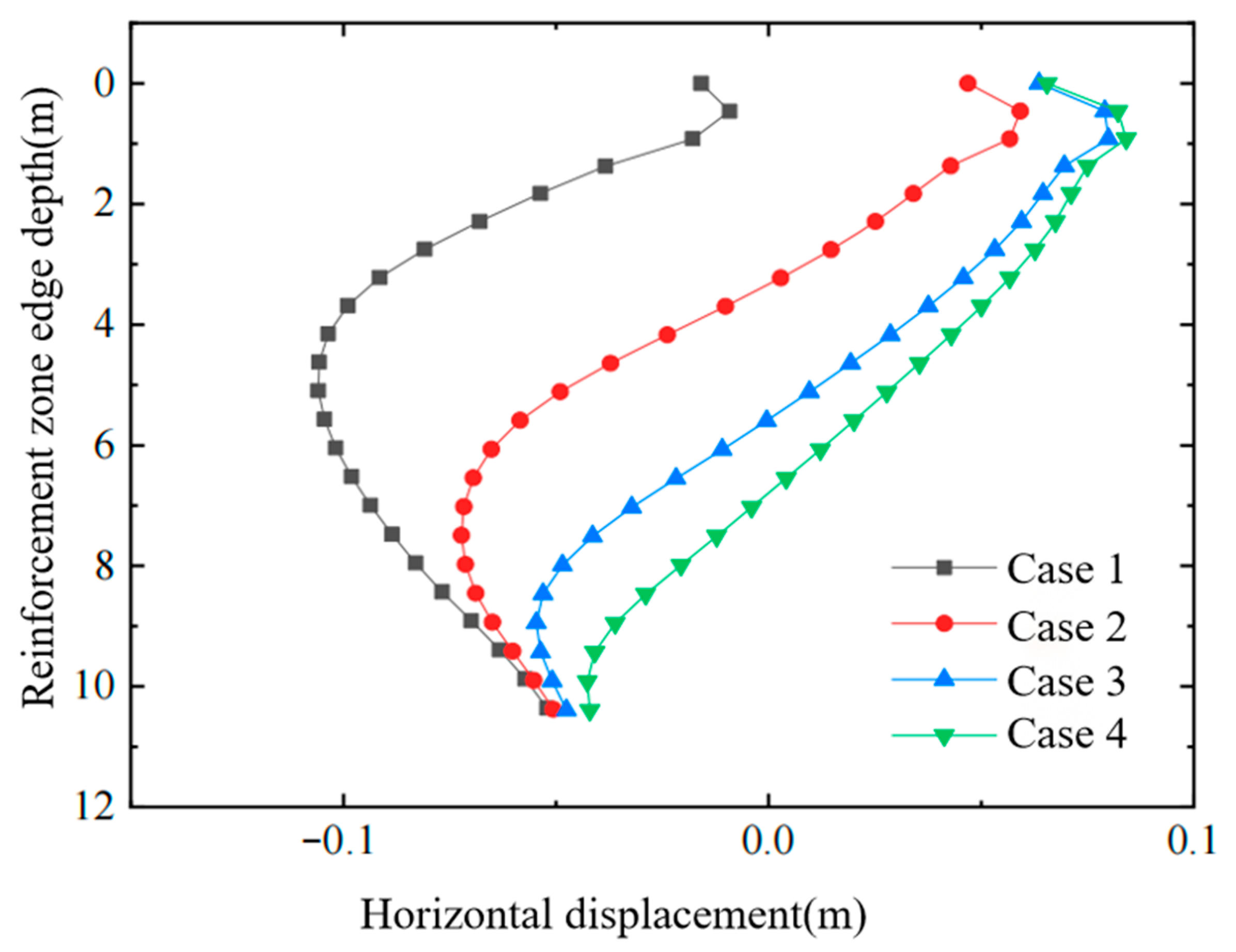

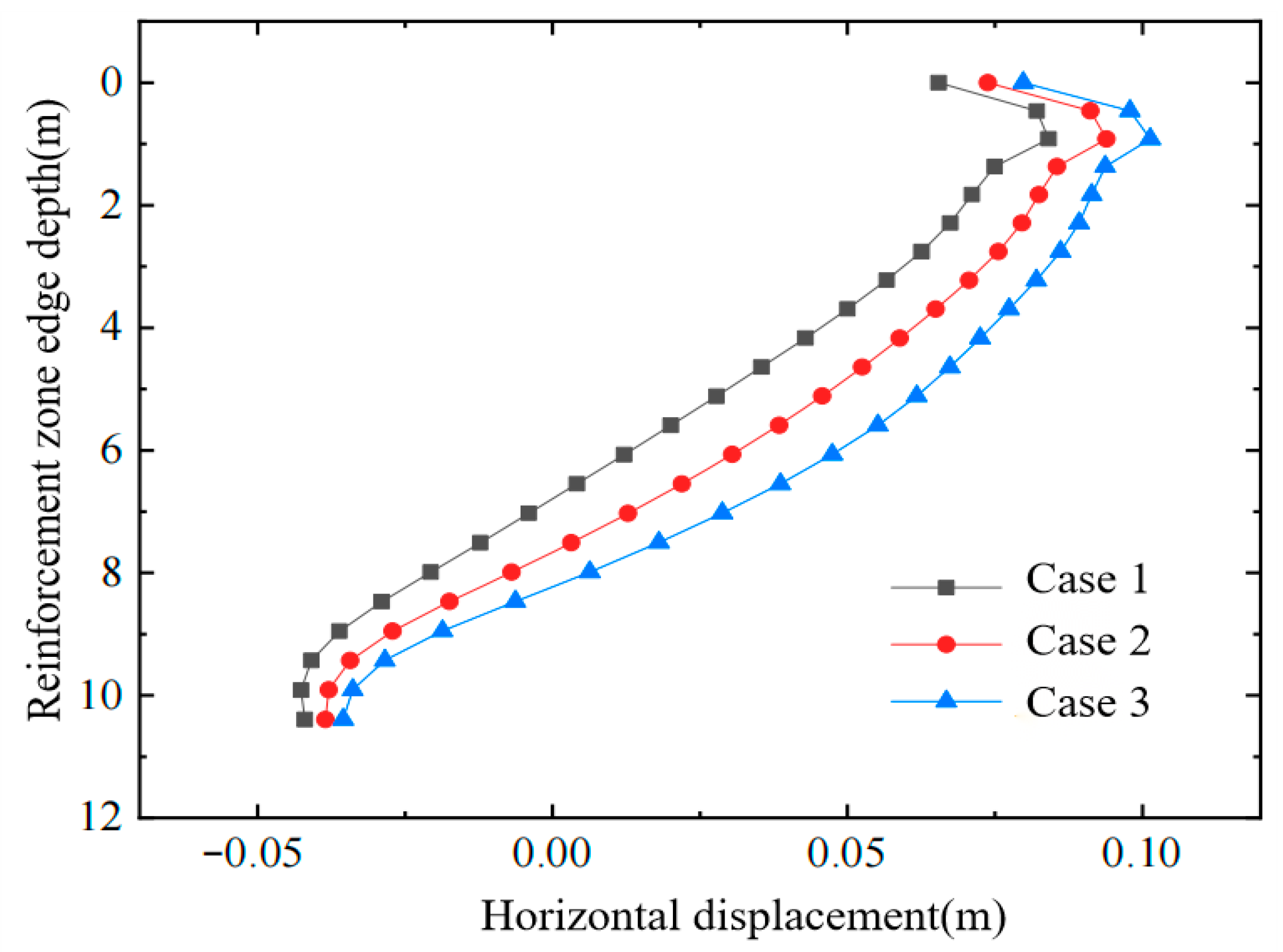

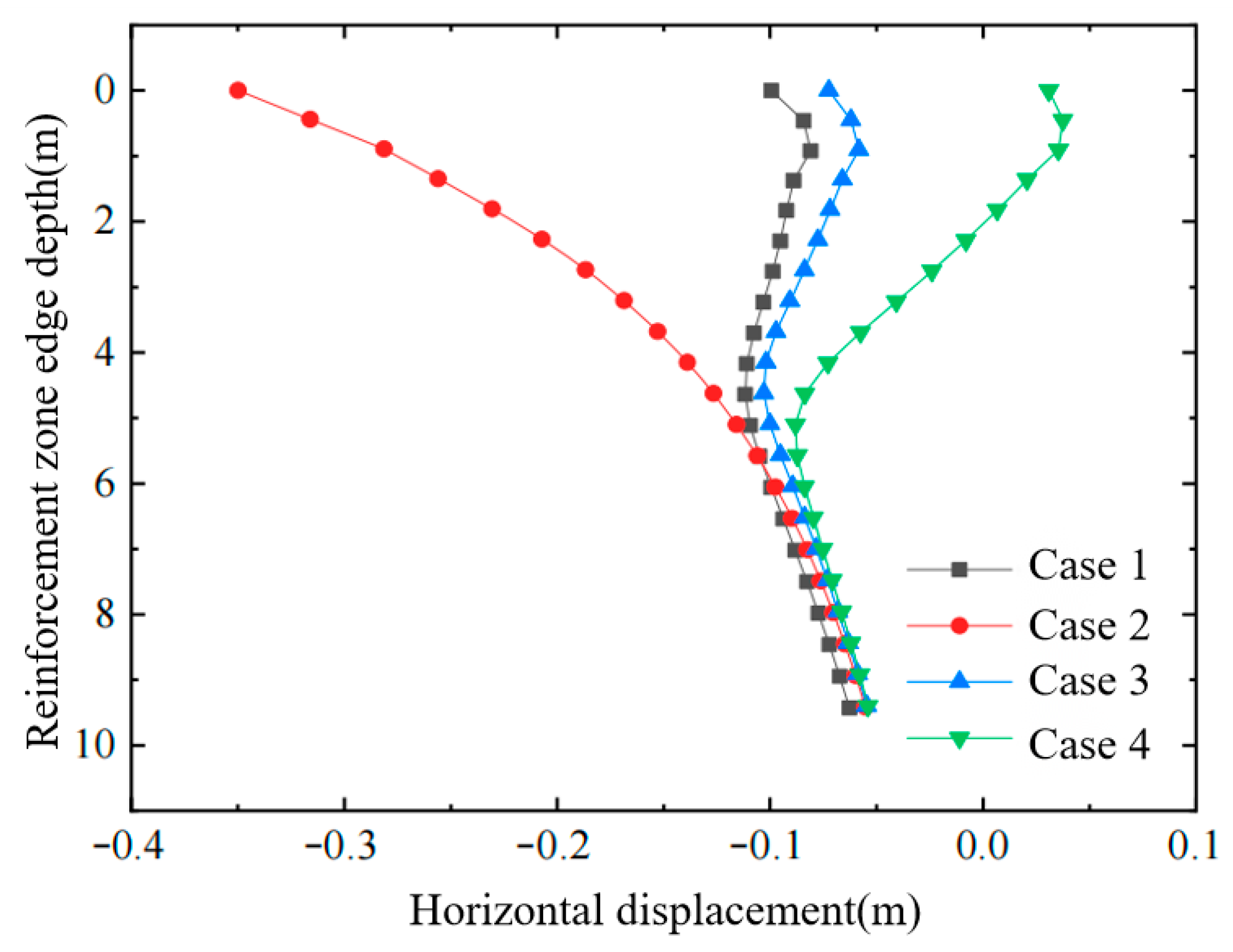

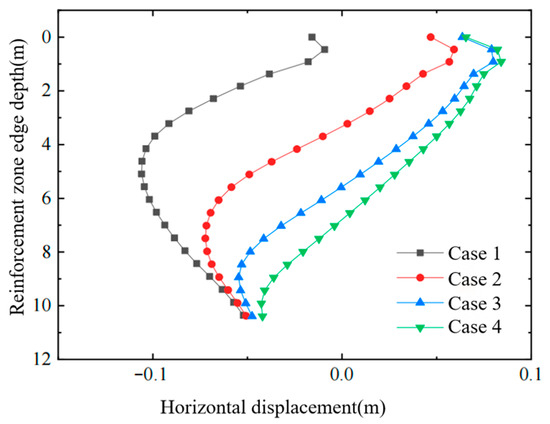

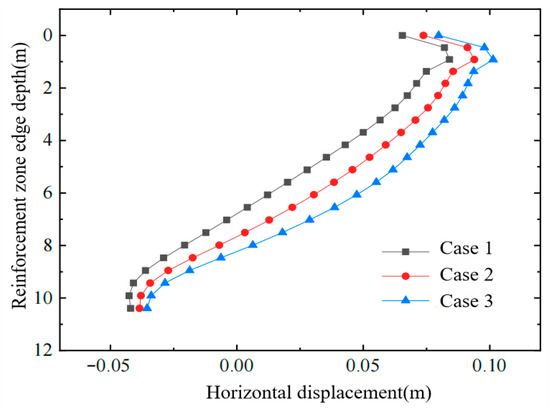

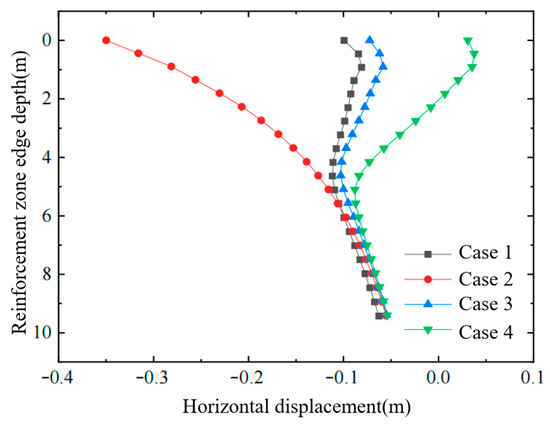

Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 present, respectively, the distributions of (i) horizontal displacement with depth at the edge of the improved zone, (ii) horizontal displacement with lateral distance in the affected area, and (iii) effective stress with depth inside the improved zone, all after treatment with different air-bag embedment depths. From these figures, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Figure 7.

Horizontal displacement of soil at the edge of the improved zone. Note: The air-bag embedment depth denotes the top elevation of the air-bag layer.

Figure 8.

Horizontal displacement of soil in the influence zone.

Figure 9.

Effective stress of soil within the improved zone.

- (1)

- For a given air-bag pressure, the horizontal displacement of the soil decreases as the bag is placed deeper. A greater embedment depth reduces the lateral movement of the deeper strata, which in turn diminishes the cumulative displacement propagated upward; consequently, the horizontal displacement in the upper layers also declines. Therefore, an appropriate air-bag depth can be selected whenever control of horizontal displacement in the affected zone is required.

- (2)

- Increasing the air-bag embedment depth raises the effective stress in the deeper soil layers, thereby further enhancing the overall strength of the foundation.

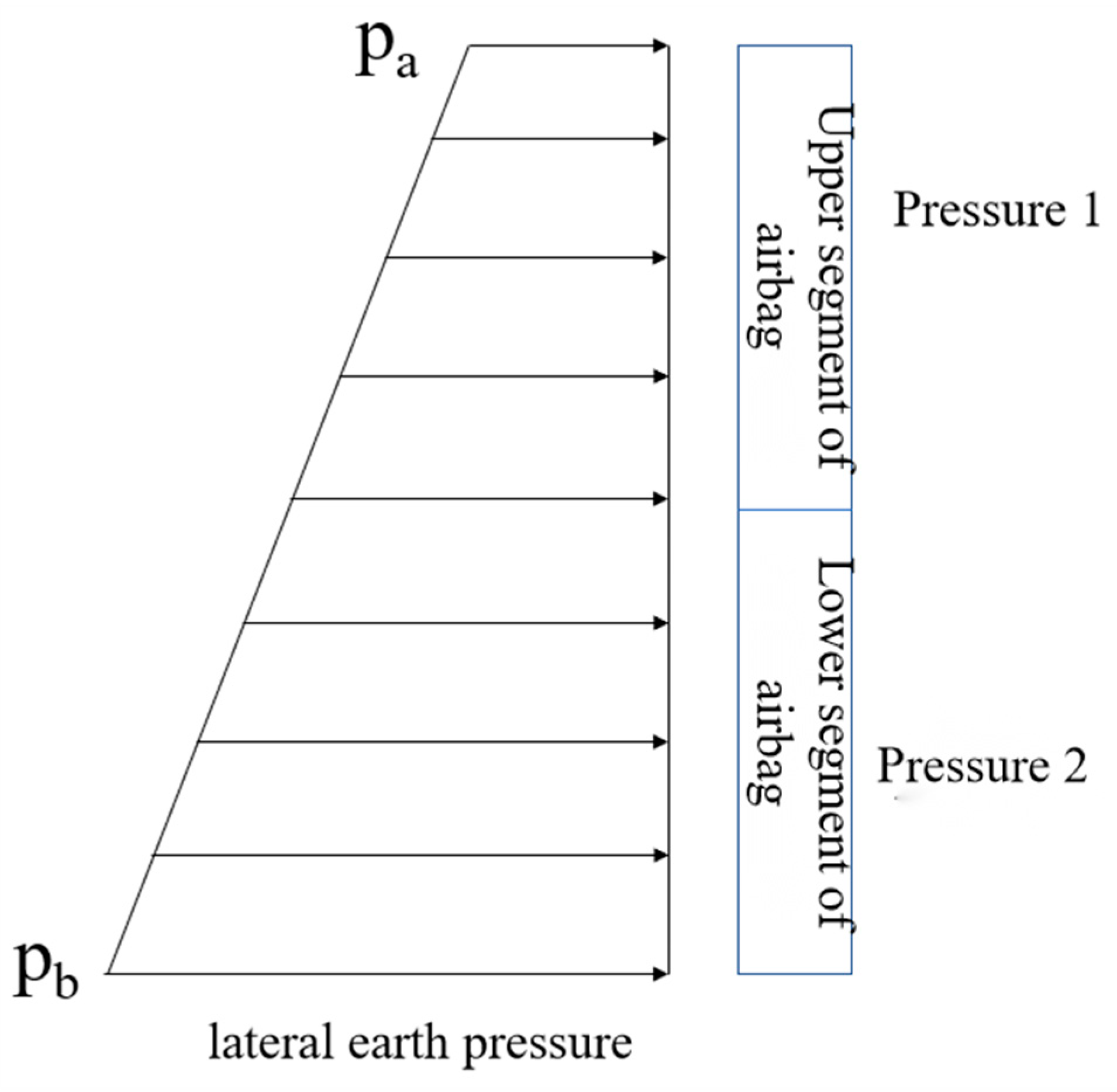

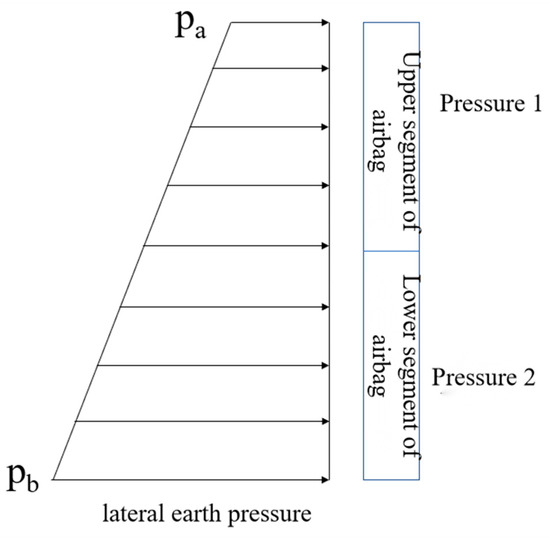

3.3. Optimized Multi-Stage Pressurization

Since lateral earth pressure increases with depth, the air-bag becomes better constrained at greater depths; consequently, the pressure can be appropriately enlarged below a certain elevation to enhance the improvement of the deeper soil and further reduce its lateral displacement. A stepped pressurization scheme—lower pressure in the upper part and higher pressure in the lower part—is adopted, as illustrated in Figure 10. The specific working conditions are shown in Table 4.

Figure 10.

Stepped air-bag pressurization method.

Table 4.

Cases with different staged pressurization schemes.

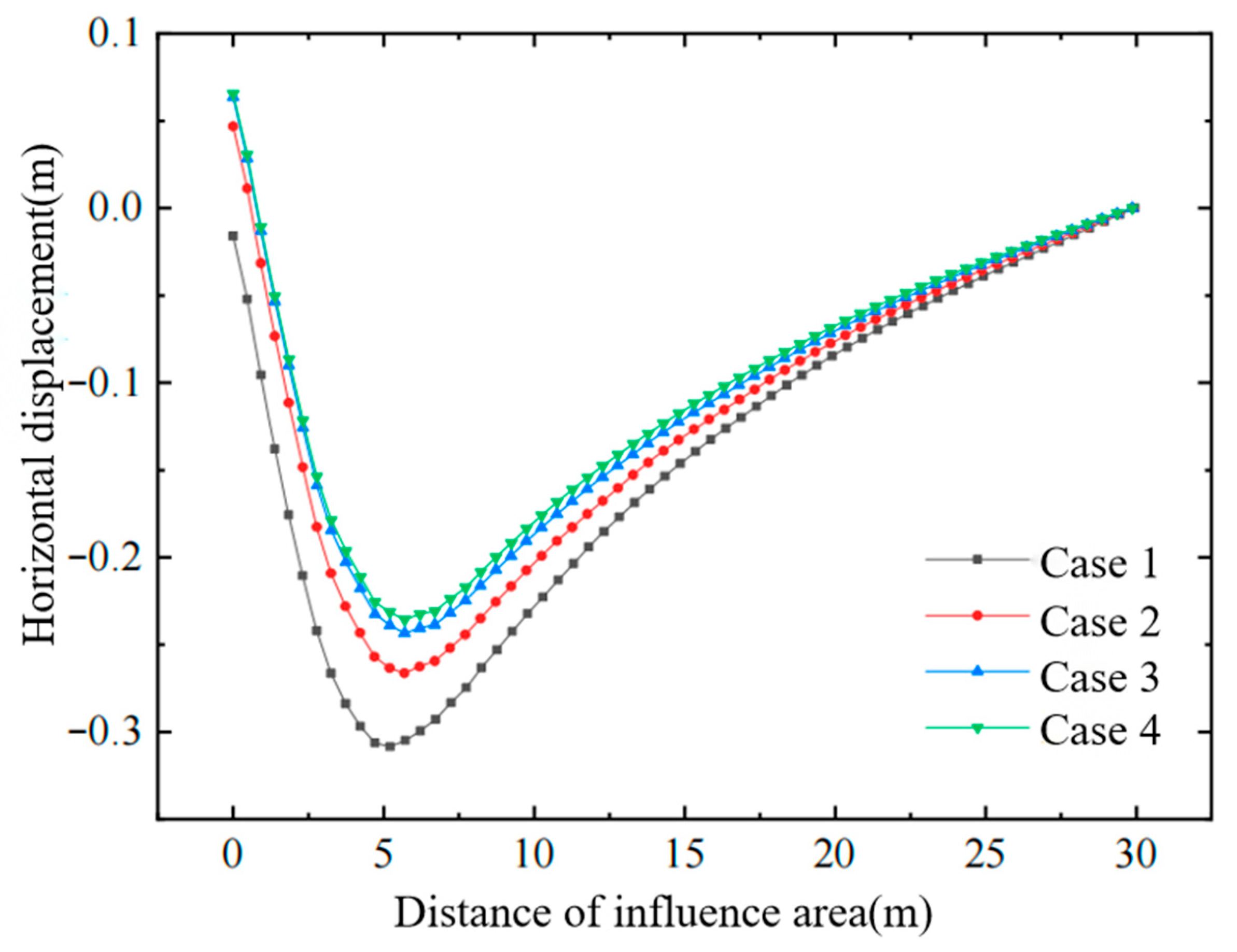

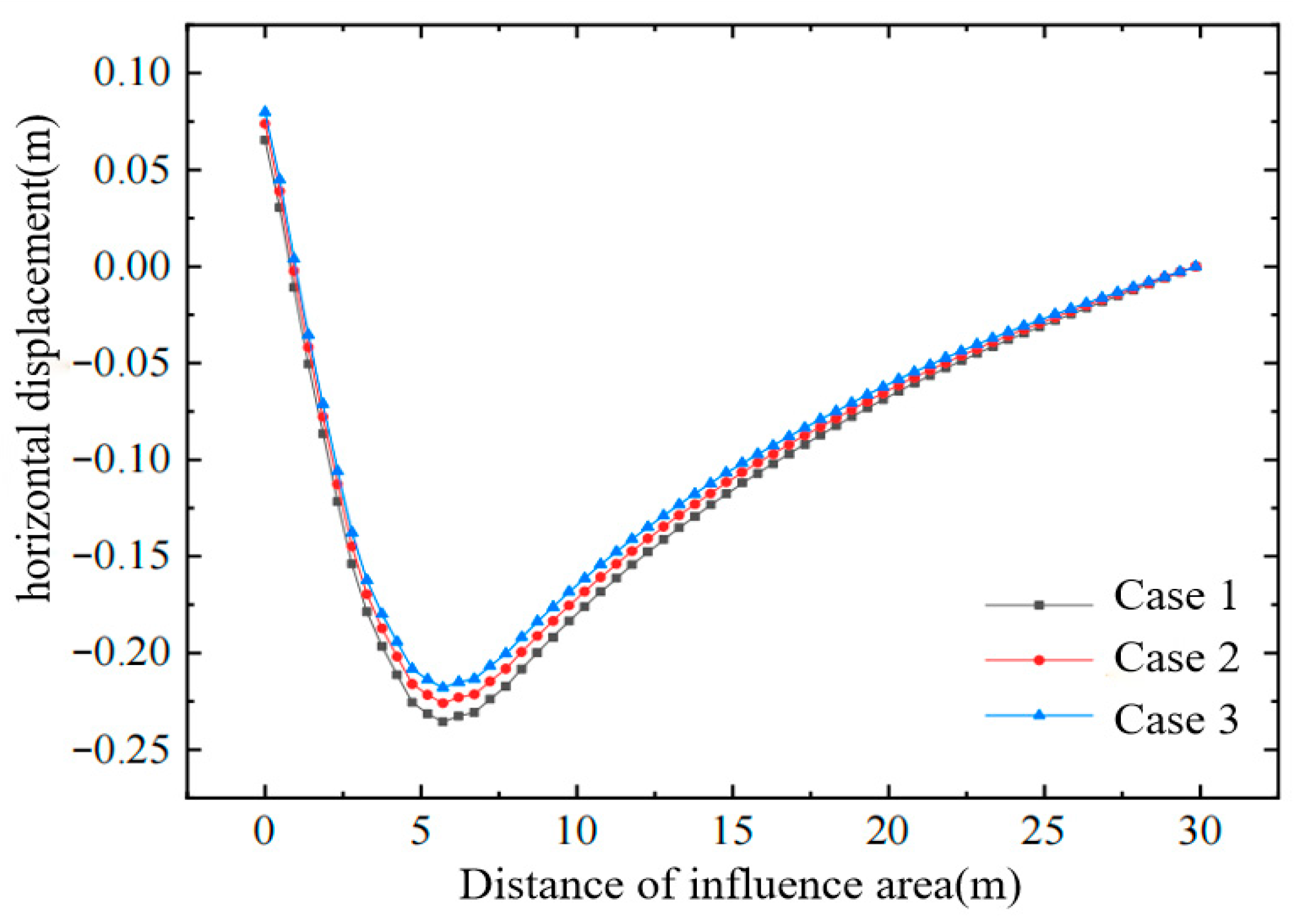

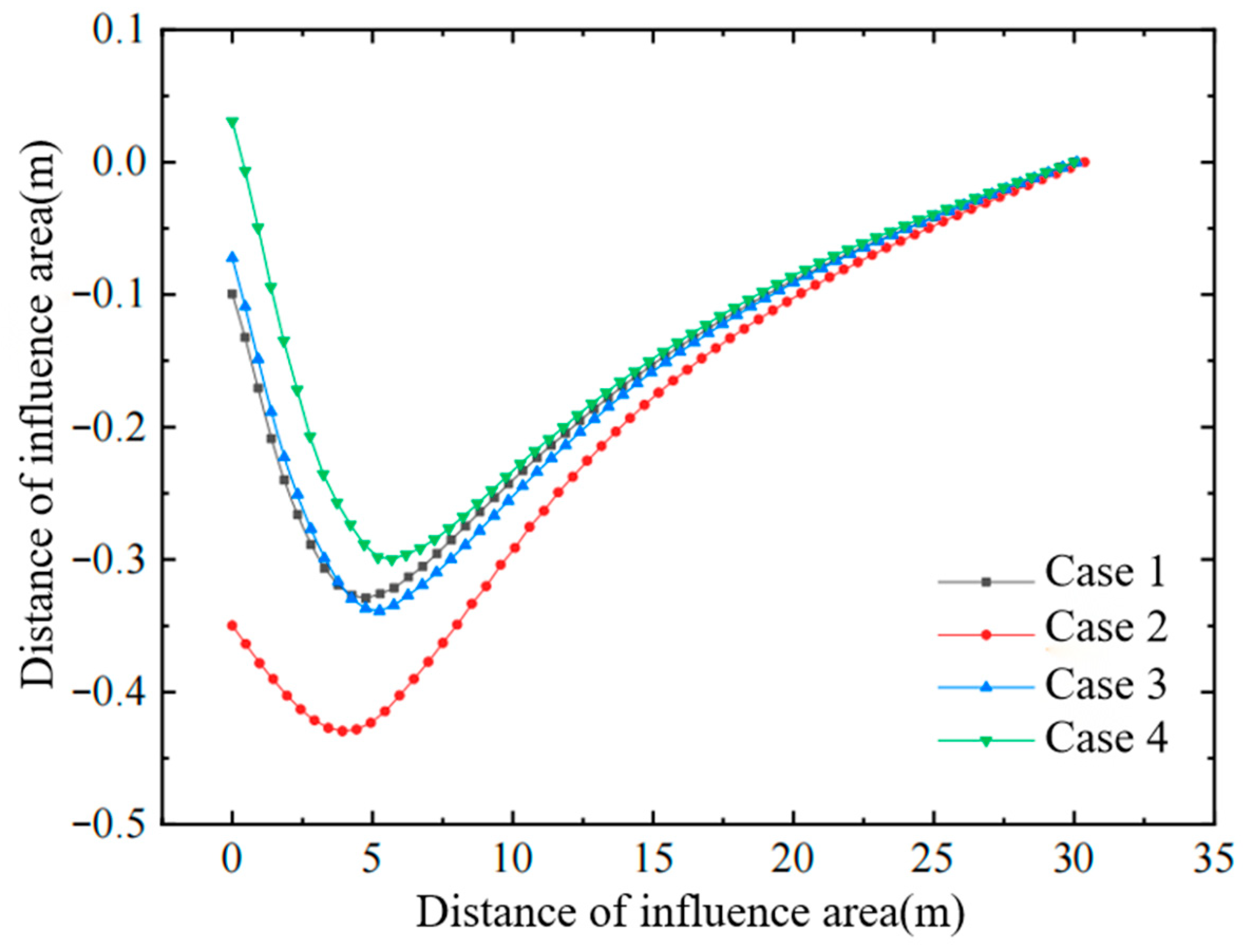

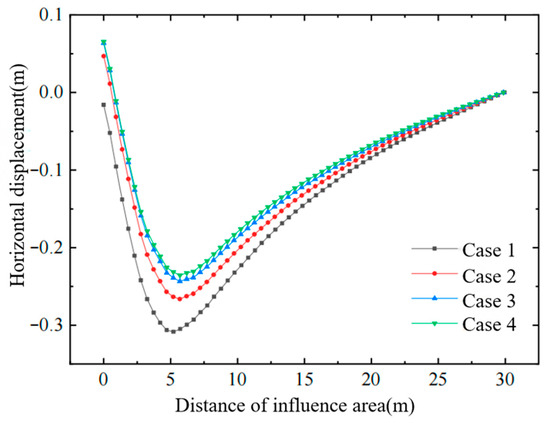

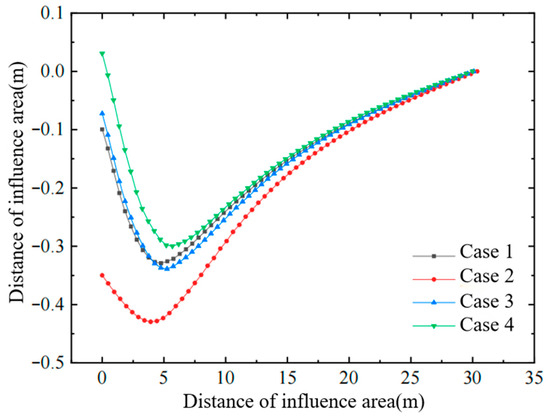

Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 show, respectively, (i) horizontal displacement versus depth at the edge of the improved zone, (ii) horizontal displacement versus lateral distance in the influence zone, and (iii) effective stress versus depth inside the improved zone, all after treatment with different stepped air-bag pressurization schemes. From these figures, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Figure 11.

Horizontal displacement of soil at the edge of the improved zone.

Figure 12.

Horizontal displacement of soil in the influence zone.

Figure 13.

Effective stress of soil within the improved zone.

- (1)

- Compared with applying a uniform air-bag pressure over the entire depth, the stepped “smaller-at-top, larger-at-bottom” pressure distribution more effectively counteracts the inward vacuum-induced contraction, reducing the horizontal displacement of the deep soil and, in turn, further decreasing the negative horizontal displacement of the upper layers.

- (2)

- The stepped air-bag pressure (lower at the top, higher at the bottom) further increases the effective stress in the deeper soil, thereby enhancing the overall strength of the foundation.

3.4. Application of Combined Surcharge Preloading

To better protect adjacent buildings and underground utilities, vacuum preloading is often combined with surcharge preloading to control lateral soil deformation. This section, therefore, examines the effectiveness of (i) vacuum + surcharge preloading, (ii) vacuum + air-bag pressurization, and (iii) the simultaneous use of all three measures in restraining lateral soil movement; the cases investigated are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Cases with different air-bag embedment depths.

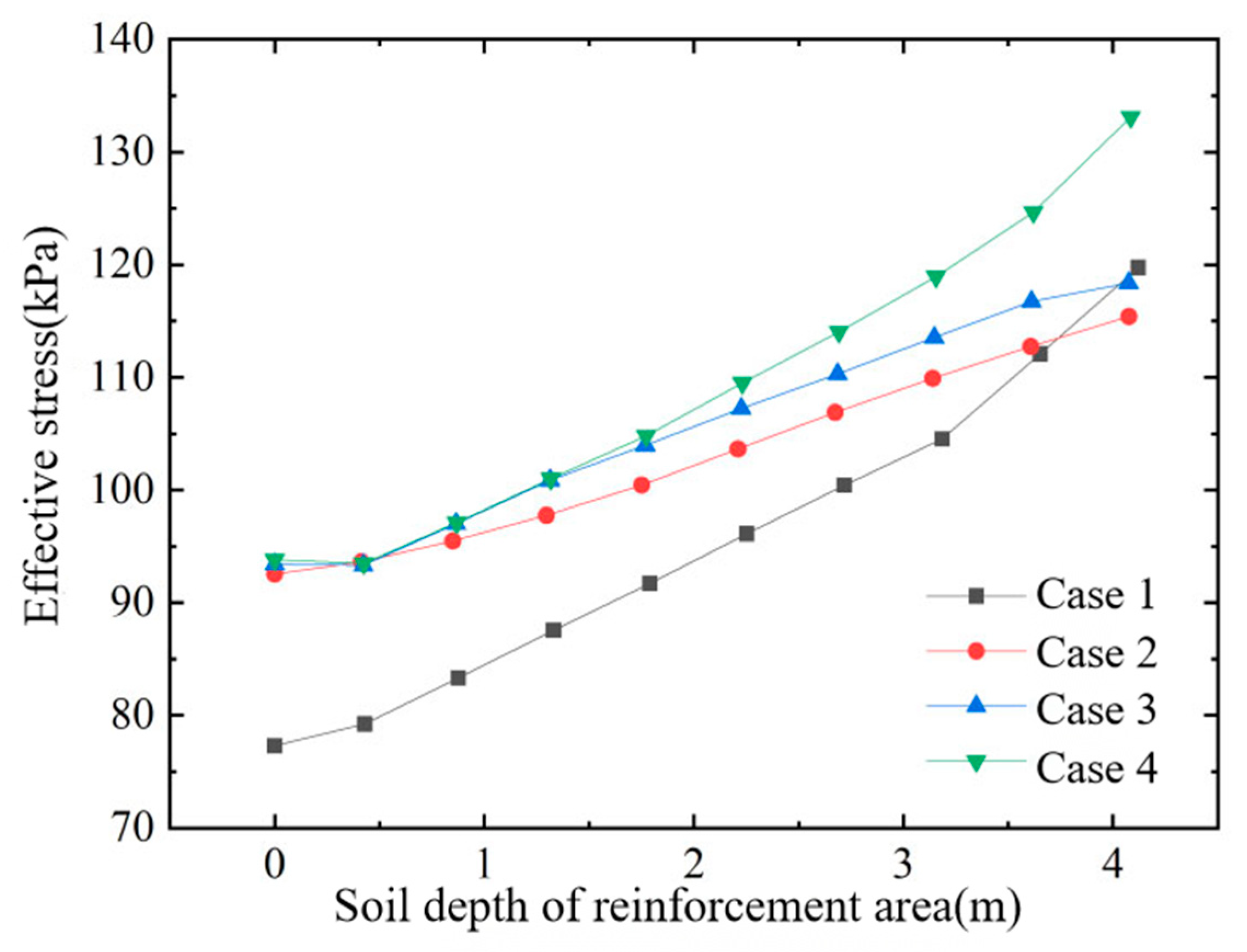

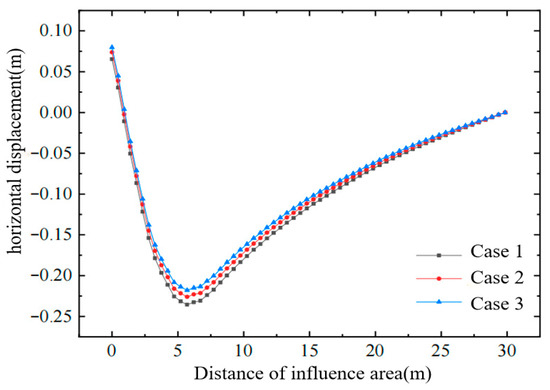

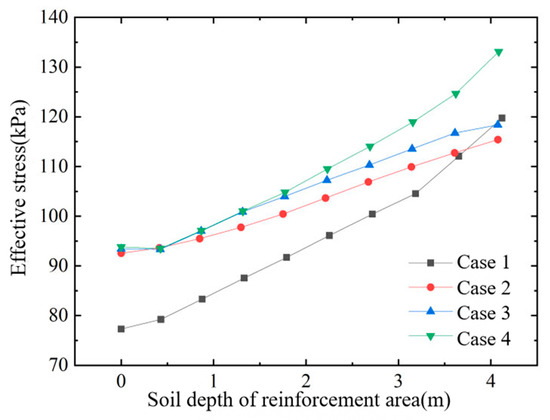

Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16 present, respectively, the distributions of (i) horizontal displacement with depth at the edge of the improved zone, (ii) horizontal displacement with lateral distance in the influence zone, and (iii) effective stress with depth inside the improved zone, after treatment by (a) vacuum + air-bag pressurization, (b) vacuum + surcharge preloading, and (c) the simultaneous application of all three measures. From these figures, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Figure 14.

Horizontal displacement of soil at the edge of the improved zone.

Figure 15.

Horizontal displacement of soil in the influence zone.

Figure 16.

Effective stress of soil within the improved zone.

- (1)

- Compared with the combined vacuum–surcharge preloading method, the vacuum preloading plus air-bag pressurization scheme produces an additional reduction in negative (inward) horizontal soil displacement.

- (2)

- Under the same air-bag pressure, the combined vacuum–air-bag–surcharge preloading method further reduces lateral soil displacement and increases effective stress.

- (3)

- At the same surcharge pressure, increasing the air-bag pressure reduces the soil’s negative horizontal displacement, with the reduction being most pronounced within the depth interval where the air bag is installed.

- (4)

- For the same surcharge pressure and soil depth, the effective stress in the soil increases significantly after air-bag pressurization, and this effective stress rises with the magnitude of the air-bag pressure.

The finding that a 10 kPa internal air-bag pressure can reduce lateral displacement more effectively than a 30 kPa external surcharge, despite the lower pressure magnitude, can be attributed to the fundamental difference in load application mechanism. The internal air-bag applies pressure directly within the soil mass, generating lateral expansion that more efficiently counteracts the inward shear strains induced by vacuum preloading. In contrast, the surcharge load applied at the surface must transfer downward, primarily inducing vertical compression, with a less pronounced direct effect on lateral restraint at depth. Furthermore, for the hybrid vacuum–air-bag–surcharge configuration, it was observed that the surcharge predominantly enhances consolidation in the upper layers, while the air-bag is more effective in controlling deformation and increasing effective stress in the deeper layers. This depth-dependent effect suggests that in practical designs, a combined approach can be optimized to target specific zones of concern.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The VPA method significantly reduces inward horizontal displacement by over 20% under –80 kPa vacuum and 20 kPa air-bag pressure, while effective stress increases linearly with pressure.

- (2)

- Early pressurization (20 days) enhances lateral deformation control and strength gain. Deeper embedment (e.g., 10 m) further reduces displacement and increases deep-layer effective stress.

- (3)

- Staged pressurization (20 kPa upper, 40 kPa lower) outperforms uniform loading, reducing displacement by an additional 5–8% and improving cost-effectiveness.

- (4)

- Under equivalent total load, VPA reduces horizontal displacement by 10–18% compared to vacuum–surcharge preloading.

- (5)

- The hybrid vacuum–air-bag–surcharge scheme achieves the highest effective stress and minimal lateral deformation.

- (6)

- Limitations and Future Work: The model assumes axisymmetric conditions and idealized soil homogeneity. Future studies should incorporate 3D effects, soil heterogeneity, and field validation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; Methodology, Y.L. and H.C.; Software, K.M.; Validation, H.C.; Visualization, T.J.; Formal analysis, R.Z.; Investigation, R.Z., Y.D. and J.Z.; Resources, Y.D. and J.Z.; Data curation, K.M. and T.J.; Writing—original draft, K.M.; Writing—review and editing, Y.L. and H.C.; Supervision, Y.W.; Project administration, Y.W.; Funding acquisition, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research work herein was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant No. 2232024D-15), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 42472339), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (grant No. 24ZR1400300), and the Discipline Development and Research Capacity Enhancement Project of Donghua University (grant No. 2025XKNLTS-21).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yulu Dong and Juntao Zhang were employed by the company Shanghai Chengtou Channel Construction Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| VPA | Vacuum preloading–air-bag |

| PVD | Prefabricated vertical drain |

| MCC | Modified Cam-Clay |

| λ | Compression index |

| κ | Swelling index |

| M | Critical state stress ratio |

| e | Void ratio |

| k | Permeability coefficient |

References

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Gao, Y. The status quo of dredged spoils utilization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 25, 39–41+50. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, J.; Yan, S.; Indraranata, B. Vacuum preloading techniques- recent developments and applications. GeoCongress 2008 Geosustain. Geohazard Mitig. 2008, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indraratna, B.; Rujikiatkamjorn, C.; Balasubramaniam, A.; McIntosh, G. Soft ground improvement via vertical drains and vacuum assisted preloading. Geotext. Geomembr. 2012, 30, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Shang, J. Vacuum preloading consolidation of Yaoqiang Airport runway. Geotechnique 2000, 50, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voottipruex, P.; Bergado, D.; Lam, L.; Hino, T. Back-analyses of flow parameters of PVD improved soft Bangkok clay with and without vacuum preloading from settlement data and numerical simulations. Geotext. Geomembranes 2014, 42, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indraratna, B.; Rujikiatkamjorn, C.; Kelly, R.; Buys, H. Sustainable soil improvement via vacuum preloading. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Ground Improv. 2010, 163, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, H.; O’Kelly, B.C. Sustainability of combined vacuum and surcharge preloading. In Proceedings of the 2014 Geo-Congress: Geo-Characterization and Modeling for Sustainability, Atlanta, GA, USA, 23–26 February 2014; GSP. American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2014; Volume 234, pp. 3826–3835. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Chen, G.; Deng, Q.; Xu, Y.; Ye, P. Influence of prefabricated vertical drains spacing on FeCl3-vacuum consolidation of a landfill sludge. Soils Found 2021, 61, 1630–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergado, D.; Chai, J.; Miura, N.; Balasubramaniam, A. PVD improvement of soft Bangkok clay with combined vacuum and reduced sand embankment preloading. Geotech. Eng. 1998, 29, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Qiao, H.; Wang, J.; Geng, X.; Wang, P.; Cai, Y. Experimental tests on effect of deformed prefabricated vertical drains in dredged soil on consolidation via vacuum preloading. Eng. Geol. 2017, 222, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, M.; Lezgy-Nazargah, M.; Shafaie, V.; Movahedi Rad, M. Numerical Study of the Ultimate Bearing Capacity of Two Adjacent Rough Strip Footings on Granular Soil: Effects of Rotational and Horizontal Constraints of Footings. Buildings 2024, 14, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.-C.; Carter, J.; Hayashi, S. Vacuum consolidation its combination with embankment loading. Can. Geotech. J. 2006, 43, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saowapakpiboon, J.; Bergado, D.; Voottipruex, P.; Lam, L.; Nakakuma, K. PVD improvement combined with surcharge and vacuum preloading including simulations. Geotext. Geomembranes 2011, 29, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.-W.; Chu, J. Soil improvement for a storage yard using the combined vacuum fill preloading method. Can. Geotech. J. 2005, 42, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indraratna, B.; Rujikiatkamjorn, C.; Ameratunga, J.; Boyle, P. Performance prediction of vacuum combined surcharge consolidation at Port of Brisbane. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2011, 137, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hu, L. Laboratory tests of electro-osmotic consolidation combined with vacuum preloading on kaolinite using electrokinetic geosynthetics. Geotext. Geomembr. 2019, 47, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, F.; Mi, W.; Cai, Y.; Fu, H.; Wang, P. Experimental study on the improvement of marine clay slurry by electroosmosis-vacuum preloading. Geotext. Geomembr. 2016, 44, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.H.; Yu, X.J.; Gao, M.J.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Xu, W. Consolidation experimental study on vacuum-electroosmosis combined reinforcement technology. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2017, 39, 250–258. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, R.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Tran, Q.C. Experimental study of PVD-improved dredged soil with vacuum preloading and air pressure. Geotext. Geomembr. 2022, 50, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Nguyen Xuan Quang, C. Experimental study on vacuum preloading combined with intermittent airbag pressurization for treating dredged sludge. Geotext. Geomembr. 2025, 53, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, H.; Lu, Y.; Wu, J.; Quang, C.N.X. Experimental study on controlling surrounding soil deformation during vacuum preloading by Volume-Compensated Airbag. China Civ. Eng. J. 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).