Abstract

Streets are vital socio-spatial infrastructures that shape mobility, well-being, and social inclusion across age groups. This study conducts a comprehensive bibliometric and comparative review of all-age-friendly street walkability research in the Chinese (CNKI) and English (Web of Science) literature from 1994 to 2024. Using CiteSpace for keyword co-occurrence, clustering, and burst detection, 204 publications were analyzed to map thematic evolution and methodological trends. Results reveal a persistent elderly-oriented bias and fragmented cross-scale integration, with international studies demonstrating earlier theoretical maturity and multi-scalar analytical models, while Chinese research advances in streetscape image analysis, VR simulations, and perception-based designs. Despite their differing trajectories, both studies converge on the shared goal of enhancing walkability, health, and urban livability. This review highlights key research gaps—particularly intergenerational assessment frameworks, explainable analytics, and policy translation—and proposes pathways toward integrating design, planning, and governance to promote all-age-friendly streets worldwide.

1. Introduction

With the accelerated pace of global urbanization, urban planning and design have progressively shifted from a singular focus on economic growth towards a greater emphasis on social equity, environmental sustainability, and residents’ quality of life. The concept of inclusive cities underscores the equitable provision of urban spaces and services, ensuring that residents of all ages, genders, abilities, and social backgrounds can equally access urban resources and services. Within this context, the creation of livable streets has emerged as a significant objective in contemporary urban planning. Developing age-friendly street environments, particularly those catering to the needs of vulnerable groups such as children and the elderly, has become a crucial step in achieving the goals of inclusive urban development.

Currently, China is confronting dual severe challenges in its demographic structure: declining birth rates and an aging population. As vulnerable groups in urban settings, children and the elderly heavily rely on walking and street environments for daily activities, such as children traveling to school and older adults accessing shops and healthcare facilities. However, street design in many Chinese cities remains predominantly vehicle-oriented, overlooking the needs of pedestrians and non-motorized transport. This has resulted in street environments that are insufficiently friendly to children and the elderly. Globally, urban street design also commonly faces issues of inadequate development. For instance, although some cities in developed countries have made notable progress in creating pedestrian- and bicycle-friendly streets [1], many still struggle with challenges such as inequitable distribution of street space and a lack of age-friendly facilities.

1.1. Definition and Characteristics of “Age-Friendly”

“Age-friendly” (all-age friendly) refers to urban spaces, facilities, and services that meet the needs of residents across all age groups, particularly addressing the specific requirements of vulnerable populations such as children and the elderly, thereby creating an inclusive, safe, and comfortable living environment [2].

The core concepts and practices of age-friendly approaches were widely implemented even before the 1980s. The barrier-free design movement of the 1970s, which aimed to provide accessible environments for older adults and people with disabilities, can be regarded as an early practice of the age-friendly concept.

Recent research has focused on defining and identifying the core characteristics of age-friendly cities. A 2014 study [3] preliminarily defined the concept of age-friendly cities, emphasizing that such cities must not only align infrastructure and spatial planning with the needs of all age groups but also foster intergenerational trust and solidarity. Building on the analysis of similarities and differences between elderly-friendly and child-friendly city concepts, a 2016 study further advanced this discourse by issuing a manifesto for cities that are friendly to all ages. Meanwhile, Western scholars such as Nicholas Boys Smith [4] and the organization “Create Streets” he founded have emphasized the impact of traditional street morphology and human-scale design on social interaction and emotional well-being, proposing “visual preference” and “emotional comfort” as key dimensions for evaluating street quality [4]. Furthermore, principles advocated by the Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU)—such as “walkability first” and “mixed-use development”—have also provided theoretical support for the design of all-age-friendly streets [5]. In recent years, eye-tracking and visual attention scanning technologies have been applied to diagnose street emotional comfort. From the perspective of “cognitive urbanism”, Sussman and Hollander (2021) revealed how visual characteristics of the environment influence pedestrians’ emotions and behavioral patterns, offering empirical evidence for micro-scale street design [6].

1.2. Research Significance of “Age-Friendly” Pedestrian Environments

The importance of building inclusive cities and age-friendly street environments cannot be overstated. Firstly, for children, a friendly street environment can foster the development of independent mobility, enhance their sense of social participation, and boost self-confidence. Secondly, for older adults, a well-designed street environment can extend their period of independent living and improve their quality of life. Due to declining physical strength, older adults rely more heavily on pedestrian environments, where safety, comfort, and accessibility directly influence the scope and frequency of their daily activities [7]. Furthermore, age-friendly street environments can promote intergenerational communication and strengthen community cohesion, thereby contributing to social harmony and development.

Within the context of the age-friendly cities concept, scholars have extensively explored this topic from various disciplinary perspectives and research dimensions. However, several issues remain unresolved: there is a lack of systematic integration of core research questions and future trends; the potential of interdisciplinary research methods has not been fully exploited, particularly in integrating new technologies with traditional theories; and the depth of international comparative studies needs further enhancement. Addressing these research gaps, this review aims to advance the field through three dimensions: First, it systematically synthesizes key issues and developmental trajectories in age-friendly street research, integrating existing theoretical frameworks and practical experiences. Second, it delves into interdisciplinary research paradigms to explore potential pathways for methodological innovation. Third, by comparing domestic and international research findings, it elucidates the impact of cultural contexts on pedestrian environment design, providing a global reference for localized practices. This study not only seeks to address existing theoretical gaps but also aims to establish a foundation for developing a scientifically and culturally adaptive evaluation system for age-friendly streets. Ultimately, it aims to steer research on urban pedestrian environments toward more intelligent and human-centered directions.

2. Methods and Data

2.1. Methods

As a method for literature research, bibliometric analysis of cultural literature effectively integrates the strengths of multiple disciplines such as mathematics, statistics, and sociology to conduct quantitative investigations. The CiteSpace (v6.1) visualization tool, characterized by its intuitiveness, scientific rigor, and practicality, enables statistical analysis of textual information and plays a significant role in comprehensively evaluating research hotspots and exploring developmental trends.

This study employs bibliometric analysis methods and utilizes CiteSpace software to generate corresponding analytical maps. In terms of research scope, bibliometric studies primarily focus on three key aspects: basic characteristics, research hotspots, and research frontiers. Through visual analysis of these three components, the evolutionary trajectory of “age-friendly street walkability” can be intuitively presented, revealing research hotspots and future development trends [8].

2.2. Data Source

The Chinese literature data in this paper were primarily sourced from the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) database. An exact search was conducted using keywords such as “elderly and child-friendly”, “age-friendly”, “walkability”, “child-friendly”, “age-adaptive”, and “street walking”, with the literature type limited to academic journals. After screening, 78 articles were obtained. International literature data were collected from the Web of Science (WoS) core collection, covering the period from 1994 to 2024. An advanced search was performed using the keywords “Age-friendly” OR “child-friendly” AND “street” AND “Walkability”, with the literature type restricted to core journals. To enhance the representativeness and accessibility of the data, the refinement function was applied to filter disciplines such as architectural engineering and related fields, resulting in 163 articles.

3. Analysis of Research Hotspots

3.1. Analysis of Keyword Co-Occurrence Networks

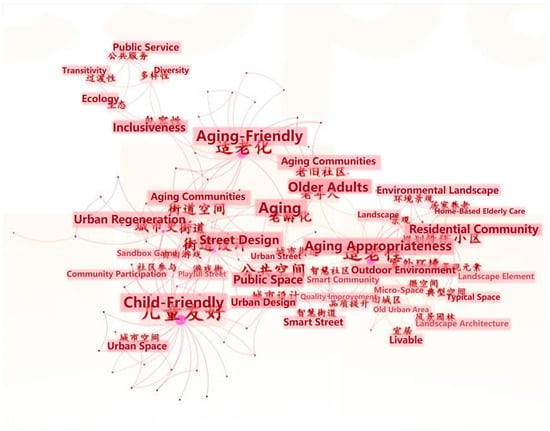

In this study, the collected data from 78 Chinese articles were imported into CiteSpace 6.1.R6 for analysis. Regarding network node settings, “keywords” were selected as the analysis nodes, and the top 50 most frequently cited keywords from each time slice were chosen to generate a keyword co-occurrence network map (Figure 1) in the field of age-friendly spatial research.

Figure 1.

Keyword Co-occurrence Network (Chinese Literature). Note: Reveals weak integration between “child-friendly” and “age-adaptive” research.

This network map reveals key core nodes such as “child-friendly”, “community governance”, and “aging”. The thick connecting lines between these core nodes indicate a strong correlation between the two primary groups—the elderly and children—in existing research findings. However, studies on street environment governance from a perspective that simultaneously addresses the needs of both the elderly and children have not yet formed a systematic framework. Specifically, in the keyword co-occurrence network map, “child-friendly” and “age-adaptive” appear as two independent nodes with thin connecting lines, reflecting a weak correlation between them. Furthermore, the map clearly shows that nodes addressing the common concerns of both age groups or the broader all-age perspective are limited in number and do not occupy a prominent position in the overall network. This suggests that current research in urban design and street environment planning needs to improve its focus on inclusively addressing the needs of specific demographic groups.

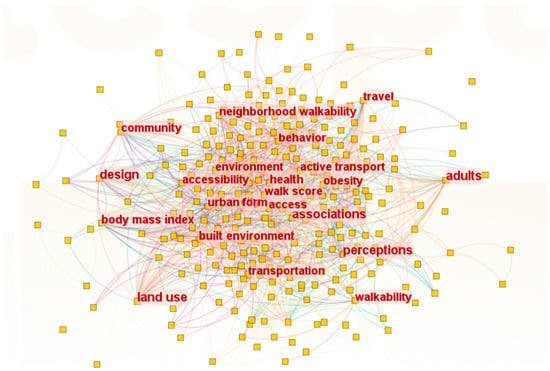

In the co-occurrence network map of the 163 English literature articles (Figure 2), keywords such as “built environment”, “walkability”, and “health” are connected by thick lines, indicating their strong interrelatedness in research. Other keywords, including “community behavior”, “urban form”, “transportation”, and “land use”, also occupy significant positions.

Figure 2.

Keyword Co-occurrence Network (English Literature). Note: Shows strong, established links between “built environment”, “walkability”, and “health”.

First, “built environment” is closely associated with “urban form” and “land use”. Studies have shown that compact urban forms and mixed land use can significantly enhance neighborhood walkability. For instance, high-density residential areas with convenient access to public service facilities can reduce residents’ reliance on cars, encourage walking and cycling, and thereby promote physical activity and improve health outcomes [9]. Second, there is a strong correlation among “transportation”, “walkability”, and “health”. Effective transportation planning should not only focus on vehicle lane design but also prioritize pedestrian-friendly infrastructure, such as sidewalks, bicycle lanes, and public transit systems. Research indicates that areas with heavy traffic flow and high vehicle speeds are often less conducive to walking and increase the risk of traffic accidents [10], negatively impacting residents’ health. Conversely, traffic calming measures (e.g., speed bumps, pedestrian priority zones) can significantly improve neighborhood walkability and subsequently promote health [11].

“Community behavior” is another critical keyword, and its relationship with “walkability” and “health” is primarily reflected in social interactions and behavioral patterns. A well-designed walking environment not only promotes physical activity but also enhances interactions among community members, strengthening social cohesion. Walkable neighborhoods often feature more public spaces, such as parks and squares, which provide opportunities for social engagement and recreation, further contributing to mental health [12]. In North America and Europe, significant progress has been made in research on age-friendly walking environments. These studies emphasize that an age-friendly walking environment must address the needs of not only adults but also children, older adults, and people with disabilities. For example, in the Netherlands and Denmark, urban planners have successfully created walking environments suitable for residents of all ages by designing accessible sidewalks, increasing green spaces, and reducing traffic flow [13].

The interrelationships among the built environment, walkability, and health have been widely validated in practical applications. By optimizing the built environment and enhancing neighborhood walkability, residents’ health outcomes can be significantly improved.

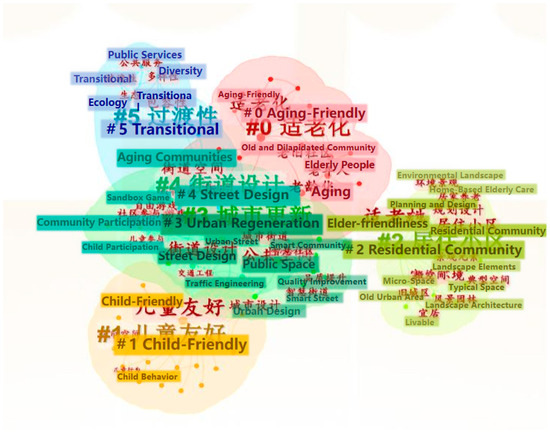

3.2. Keyword Cluster Analysis

In the keyword cluster analysis map of Chinese literature (Figure 3), a total of six clusters were generated: age-adaptive, residential neighborhoods, urban renewal, street design, child-friendly, and transitionality. Research on the correlation between the two core groups—the elderly and children—has yielded relatively abundant results, with significant overlap and integration observed between these themes. For example, in the #3 urban renewal cluster analysis, studies not only incorporate age-friendly considerations but also address child-friendly approaches. The #4 street design cluster explores issues related to aging and practices of all-age inclusivity in depth.

Figure 3.

Keyword Clusters (Chinese Literature). Note: Clusters like “urban renewal” show parallel but separate study of elderly and child needs.

Additionally, when research focuses on topics such as child participation, child-friendly environments, and aging, issues related to community governance and the creation of livable environments are naturally incorporated into the research framework.

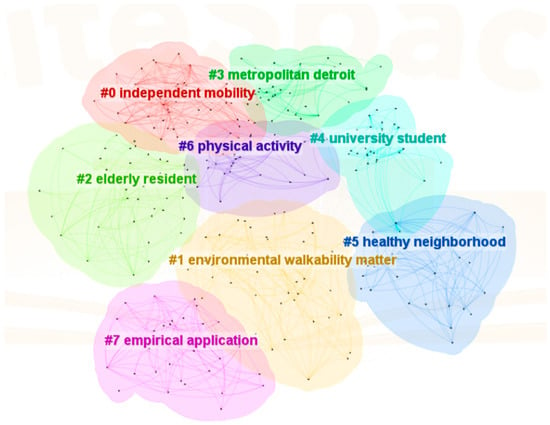

In the keyword cluster analysis map of English literature (Figure 4), seven clusters were generated, forming distinct thematic research groups that reflect the multidimensionality and complexity of current studies on age-friendly walking environments. First, Cluster #0 “independent mobility” highlights the focus on residents’ ability to move independently, particularly among older adults and children. Well-designed walking environments and public transportation systems can significantly enhance independent mobility. For example, in Sweden, urban planners have improved the independent travel capabilities of older adults and children by implementing barrier-free transportation systems and pedestrian-friendly communities [14]. Cluster #1 “environmental walkability matter” represents one of the core research themes, reflecting academic attention to the quality of walking environments and how to optimize physical conditions to promote walking behavior. Cluster #2 “elderly resident” emphasizes the specific needs of older adults in walking environments within aging societies. Due to declining physical functions, older adults require higher standards for walking environments, such as smooth pavements, adequate lighting, and resting facilities [15]. Additionally, Cluster #4 “university student” and Cluster #3 “metropolitan Detroit” demonstrate the geographical and demographic specificity of research. University students, as a distinct group, are influenced by both campus environments and urban design in their walking behaviors. For instance, in metropolitan areas like Detroit, USA, urban planners have significantly increased walking frequency and physical activity levels among students by optimizing pedestrian environments around campuses [16]. Cluster #5 “healthy neighborhood” further underscores the close relationship between walking environments and residents’ health. Cluster #6 “physical activity” is closely linked to “environmental walkability matter” and “elderly resident”. Residents living in walkable neighborhoods exhibit significantly higher levels of physical activity compared to those in car-dependent communities. For older adults, moderate physical activity can delay aging, prevent chronic diseases, and improve quality of life [17].

Figure 4.

Keyword Clusters (English Literature). Note: Illustrates a multi-scale focus, from independent mobility to specific age groups.

Keyword cluster analysis based on bibliometric methods effectively reveals the multidimensionality and complexity of research on age-friendly walking environments. By optimizing walking environments, particularly through designs catering to the needs of specific groups such as older adults and children, residents’ physical activity levels can be significantly enhanced, leading to improved health outcomes.

3.3. Keyword Burst Detection

The keyword burst detection mechanism focuses on analyzing patterns of changes in word frequency over time, aiming to identify those keywords with high rates of frequency change and rapid growth as burst keywords from a broad range of everyday vocabulary. Furthermore, by integrating the evolutionary trends of these burst keywords with an in-depth analysis of current research hotspots, the research frontiers can be delineated into three distinct phases:

In the first phase, dating back to before 2005, the concept of “age-friendly” was primarily regarded as one of the social elements, emphasizing its application in urban design. During the second phase, from 2005 to 2017, research on “age-friendly” experienced explosive growth, with its application boundaries significantly expanding to encompass multiple disciplinary areas such as urban morphology, questionnaire surveys, reliability assessment, activity space environments, and multifunctional land use. In the third phase, post–2017, the walkability of “age-friendly” streets has become increasingly intertwined with urban design quality, while also intersecting deeply with areas such as resident satisfaction surveys, indicator system construction, space syntax theory, and health-related studies. This trend suggests that, in future academic exploration, the walkability of “age-friendly” streets is poised to serve as a comprehensive evaluation indicator system, playing an increasingly important role in optimizing urban environmental design and assessing resident health outcomes.

4. Discussion

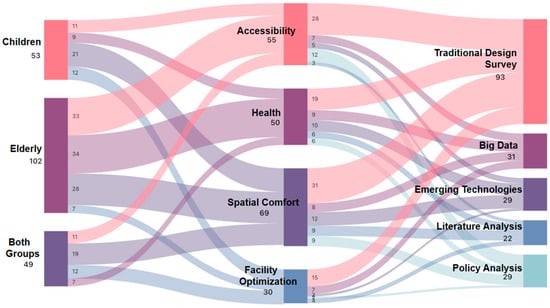

Through manual screening of the 241 Chinese and English articles retrieved, studies with unclear research subjects or unconventional research questions were excluded, resulting in 204 valid articles for visual analysis (Figure 5). As illustrated in the figure: the first column categorizes the research subjects into three groups—children (53 articles), the elderly (102 articles), and both groups (49 articles). The second column classifies the research questions into four primary domains within architecture and urban planning: accessibility, health, spatial comfort, and facility optimization. The third column outlines the research methodologies employed: traditional design investigation, big data analysis, emerging technologies, literature analysis, and policy analysis.

Figure 5.

Sankey Diagram of Research Focus. Note: Quantifies the dominance of elderly-focused studies and traditional methods.

Based on the Sankey diagram analysis of the 204 valid articles, current research on age-friendly streets exhibits significant structural characteristics and dimensional imbalances. In terms of subject distribution, the elderly group dominates absolutely with 102 articles (50% of the total), far exceeding the children group (53 articles) and the intergenerational group (49 articles). This distribution highlights the urgency of addressing aging society needs while also revealing a systematic lack of integrated intergenerational research.

Among research dimensions, spatial comfort emerged as the highest focus with 69 articles (34%), with children studies concentrating 39.6% on this topic, reflecting the critical importance of environmental safety and experiential quality in children’s activity space design. Accessibility, health promotion, and facility optimization showed differentiated distribution with 55, 50, and 30 articles, respectively. While elderly research demonstrated balanced attention across multiple dimensions—consistent with their composite needs for mobility convenience, health maintenance, and environmental safety—the intergenerational group showed particularly weak attention to health issues (only 7 articles), revealing a serious deficiency in exploring cross-generational health intervention mechanisms.

Methodologically, there exists a binary divide between traditional path dependency and technological transformation: traditional design investigation dominates with 93 articles (45.6%), showing deep application inertia in accessibility and spatial comfort studies. Although big data analysis and emerging technologies have penetrated health and comfort studies (9 and 12 articles, respectively), they haven’t yet formed systematic applications, particularly evidenced by the mere 2 articles using emerging technologies in facility optimization research, exposing significant shortcomings in technology-enabled refined decision-making.

Current core contradictions concentrate on three aspects: fragmented intergenerational research limiting exploration of age-inclusive mechanisms, imbalanced technological application restricting spatial quality improvement efficacy, and absent interdisciplinary methodological integration hindering systematic solutions for complex urban problems. Future breakthroughs require bridging these three gaps: establishing high-density urban age-friendly theory to integrate intergenerational needs, utilizing 5G+BeiDou real-time evaluation systems to enhance technical support for facility optimization, and creating multi-department collaboration mechanisms to promote deep integration of policy analysis and spatial design. Only through these approaches can we achieve the paradigm shift from passive response to active leadership in smart city evolution.

4.1. Analysis of Domestic Research in China

With the acceleration of urbanization and the diversification of demographic structures, the concept of age-friendly streets, as an important principle in urban planning and construction, has garnered increasing attention within China’s academic community. In recent years, Chinese scholars have achieved substantial results in the field of age-friendly street research, focusing primarily on age-adaptive street environment design, child-friendly street space design, and the evaluation of street environments through scientific survey methods.

In terms of age-adaptive design, scholars have employed methods such as field surveys, questionnaires, and data analysis to explore the impact of urban street environments on the mobility and quality of life of older adults. For instance, Liu Yue and Ma Hui utilized space syntax theory to analyze the spatial structure of the Binjiang Road in Yibin and proposed recommendations for age-adaptive design [18]. Jiang Yining and Zhang Xinyu adopted the PSPL survey method to assess the age-friendliness of street spaces in Shanghai’s Siping Road community, providing a scientific basis for street renovation [19]. Child-friendly street space design represents another key research focus. Cheng Can, Zhu Xiaoyang, and Ji Wei proposed design principles and methods for creating child-friendly street spaces from the perspectives of planning, design, and management [20]. In the evaluation of street environments, Li Haiwei, Chen Chongxian, and Liu Xinyi, among others, combined human-eye-view street imagery and machine learning technologies to conduct spatial effect analyses of the age-friendliness of urban streets [21].

Overall, research on age-friendly environments has shown significant evolution and progress over time in terms of research objectives, methods, and tools. Early studies (before 2010) primarily focused on the needs of single demographic groups, such as older adults or children, employing mainly qualitative methods like field surveys, questionnaires, and case studies to address street design issues. In recent years (post–2010), research objectives have gradually shifted from single-group focus to age-friendly approaches, emphasizing street designs that simultaneously meet the needs of children, older adults, and other age groups. Methodologically, studies have transitioned from purely qualitative to integrated qualitative-quantitative approaches, with new technologies such as space syntax theory, PSPL surveys, human-eye-view street imagery, and machine learning being widely applied to the assessment and optimization of street environments.

4.2. Analysis of International Research

International research on age-friendly theories and practices began in the 1980s. Early studies primarily focused on the impact of urban environments on specific demographic groups (e.g., children and older adults), addressing topics such as children’s play spaces and accessibility facilities for the elderly [22]. By the mid-1990s, research in this area gained significant momentum. In 1994, Sherry Ahrentzen’s concept of the “all-age community” marked the initial formalization of age-friendly principles, emphasizing the need for communities to adapt to the evolving requirements of different age groups [23].

Subsequently, the scope of research expanded to include urban planning, architectural design, sociology, and other disciplines. Evaluation frameworks targeting children and older adults were developed, such as the Child-Friendly Cities Initiative (CFCI), which assesses urban friendliness based on children’s rights, protection, and participation [24]. Similarly, the Global Age-Friendly Cities Guide (GAFGC) and the Age-Friendly Community Assessment Tool (AFCT) evaluate cities’ adherence to elderly-friendly principles across dimensions including outdoor spaces, transportation, housing, and social participation, examining their impact on quality of life [25]. Concurrently, scholars critiqued car-centric urban sprawl models, arguing that such approaches neglect pedestrian and public transportation infrastructure, thereby compromising the safety and convenience of children and older adults. They emphasized that small-scale, mixed-use communities are more conducive to fostering social interaction and neighborhood cohesion, enhancing the well-being of these groups [26].

Since the 21st century, regions such as North America and Europe have increasingly embraced the “walkable city” movement, actively promoting the planning and development of pedestrian-oriented systems [27]. During this phase, research on walkability shifted from a community-level focus to a greater emphasis on street-scale environments, with studies increasingly centered on the intrinsic qualities of street design. Regarding the impact of the built environment on walking behavior among older adults, some scholars have examined factors such as the spatial distribution of service facilities and street connectivity to explore their correlation with elderly mobility. For instance, Li Harmer et al. found that higher land-use mix is associated with increased walking convenience and frequency among older adults [28]. Frank et al. demonstrated that land-use diversity and street network connectivity at the neighborhood level influence walking behavior in the elderly [29]. Additionally, cutting-edge research is increasingly employing physiological and neurological methods to diagnose the emotional comfort of street environments. Eye-tracking and visual attention scanning technologies, for instance, provide objective data on how pedestrians subconsciously perceive and react to street scenes. By analyzing metrics like fixation duration and saccadic paths, researchers can identify design features that cause “visual clutter” or induce calm, offering a quantifiable basis for creating streets that are not only physically accessible but also psychologically pleasant for all age groups. This paradigm shift towards neuro-architectural approaches complements traditional surveys and behavioral observations, promising a more holistic understanding of all-age-friendly street design.

In summary, international research has established a robust theoretical foundation and practical framework for age-friendly urban development. Future efforts should prioritize localized adaptation, interdisciplinary collaboration, and technological innovations (e.g., big data and artificial intelligence) to advance more inclusive and livable urban environments, ensuring that people of all ages can benefit equitably from urban development.

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Chinese and International Research

Research on age-friendly street walkability demonstrates significant temporal disparities and complementary characteristics between Chinese and international contexts. From a chronological perspective, studies in Western developed countries originated in the 1980s with a focus on specific vulnerable groups. Key milestones include the introduction of the “all-age community” concept and the emergence of the “walkable city” paradigm, culminating in well-established evaluation systems such as the Child-Friendly Cities Initiative (CFCI) and the Global Age-Friendly Cities Guide (GAFGC). In contrast, Chinese research prior to 2010 primarily concentrated on fragmented explorations of either age-adaptive or child-friendly interventions, with integrated all-age approaches gaining traction only in the past decade. CiteSpace analysis reveals a mere 12.7% co-occurrence rate between “child-friendly” and “age-adaptive” keywords in Chinese literature, indicating insufficient theoretical integration.

Methodologically—international research has established a multi-scalar technical framework integrating macro-level (e.g., space syntax analysis), meso-level (e.g., GIS-based land-use mix evaluation), and micro-level (e.g., PSPL behavioral annotation) approaches [30]. While Chinese studies have innovatively applied streetscape image recognition and VR simulation technologies, manual coding of the “research scope” field in Web of Science/CNKI literature shows that cross-regional comparative studies account for only 8.3% of domestically published English-language papers, with persistent challenges such as limited interpretability of machine learning models.

Interdisciplinarity—manifests distinctly: International research has developed a tripartite “social-spatial-health” theoretical framework. Public health studies validate correlations between walkable environments and chronic disease prevention—e.g., North American research demonstrates a significant negative correlation between walkability and cardiovascular disease incidence [31]. Sociology contributes “inclusive space” theories [32], while urban planning proposes operational models like the “15-min neighborhood” [33]. Conversely, Chinese research remains dominated by architectural perspectives (61.5% of CNKI literature), with limited public management engagement resulting in less actionable policy recommendations. For instance, only 7.6% of age-adaptive retrofit projects in China (2023 Ministry of Civil Affairs data) incorporated resident participation mechanisms—far below Copenhagen’s 90% co-creation rate in “citizen laboratories” [34]. This phenomenon of fragmented intergenerational research stems from multi-dimensional roots. At the disciplinary level, the dominance of architectural perspectives (constituting 61.5% of CNKI literature) in Chinese research naturally favors physical space and formal aesthetics, while relatively underemphasizing systematic analysis of intergenerational interaction mechanisms from the viewpoints of public policy, sociology, and public health. At the policy level, the early parallel promotion of “age-friendly” and “child-friendly” urban agendas in China, while achieving progress within their respective domains, has inadvertently fostered separate policy systems, evaluation standards, and academic communities, thereby intensifying the segregation of perspectives between generations. To bridge this divide, future efforts urgently require the construction of a comprehensive research framework that integrates “policy-space-society-health” dimensions.

Policy implementation—reveals sharper contrasts: Developed countries have established integrated “legislation-planning-evaluation” systems, exemplified by Paris’s annual investment of €230 million in child-friendly street upgrades [35]. Despite China’s *“14th Five-Year Plan for Urban-Rural Community Service System Construction”*, local execution faces triple challenges: insufficient interdepartmental coordination, absence of dedicated all-age indicators in existing Urban Road Design Specifications, and deficient long-term maintenance mechanisms. A 2022 National Development and Reform Commission audit reported that only 38% of pilot “elderly-child” projects established post-implementation evaluation frameworks.

Research frontiers—exhibit dynamic divergence: International studies focus on refining health impact assessment tools (e.g., genetic testing to analyze walkability’s effects on telomerase activity) [36], climate-adaptive design (e.g., London’s “canopy cover-thermal stress-walk comfort” linkage model), and digital twin applications (e.g., Singapore’s virtual urban management) [37]. Chinese research should prioritize developing “vertical accessibility” models for high-density cities leveraging Hong Kong’s skywalk systems [38]; advancing BeiDou-based trajectory analysis technologies [39]; and innovating “community planner” institutions [40]. Chengdu’s “Park City” initiative—integrating child-friendly indicators into green space standards—exemplifies potential breakthroughs through localized innovation [41].

Fundamentally, these differences reflect distinct urbanization stages: Europe and North America address “post-automobile city” renewal, while China confronts compound challenges of motorization and aging. Future breakthroughs require tripartite synergy: Theoretical: Reconstructing all-age-friendly theories for Asian high-density urban contexts; Technological: Innovating real-time environmental assessment systems integrating 5G and BeiDou technologies; Institutional: Establishing multi-departmental street design review committees [42].

Against the backdrop of smart city development and dual-carbon goals, research on age-friendly streets stands at a historical inflection point, poised to pioneer low-carbon walkability systems and intergenerational digital inclusion.

5. Conclusions and Future Envision

Leveraging the CiteSpace visualization tool, this study systematically examined 241 articles from the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and Web of Science (WoS) databases published between 1994 and 2024. However, it is important to acknowledge several limitations. The reliance on the CNKI and WoS core collections may not capture all relevant local reports or non-English studies. Furthermore, while bibliometric analysis effectively maps macrotrends, it has inherent boundaries in probing the theoretical depth of individual studies. The focus on the built environment–behavior–health nexus also means that the moderating effects of broader socio-cultural and economic variables on age-specific street perceptions are not fully explored. Despite these limitations, this review has delved into the evolutionary trajectory, core themes, and future trends of “age-friendly street walkability” research. In the future, walkability in age-friendly streets is expected to become a key metric for assessing urban environmental quality and health standards. In summary, this study not only comprehensively reviews the evolution, hotspots, and frontiers of international research on age-friendly street walkability but also aims to provide diverse reference perspectives and theoretical foundations for domestic studies, thereby fostering a deeper understanding of the field and contributing to the optimization of pedestrian environment design.

- (1)

- Integrating Digital Technology with Architecture

Capitalizing on the rapid advancement of big data technology, instant information processing capabilities have significantly improved, facilitating closer cross-regional, cross-domain, and interdisciplinary research collaboration. Concurrently, research perspectives are increasingly aligned with pressing social issues, highlighting a core value orientation of “human-centered care” [43]. By integrating multi-source data resources, more thorough and detailed analyses of various cities, specific regions, and vulnerable groups have been conducted. These trends suggest that future research on age-friendly streets is likely to witness emerging hotspots and frontier directions.

- (2)

- Interdisciplinary Integration of Architecture with Other Fields

As societal demands diversify, single-discipline perspectives have become inadequate for addressing complex real-world challenges. While architecture has achieved significant in research on elderly and child-friendly environments, addressing the public space needs of diverse demographic groups necessitates interdisciplinary integration. This cross-disciplinary approach has already demonstrated promise in recent age-adaptive and child-friendly retrofit projects, where designs have evolved from single-dimensional solutions to comprehensive, multi-disciplinary strategies.

- (3)

- Emphasizing Long-Term Policy Orientation and Benefits

In recent years, macro-level policies have consistently focused on improving community service facilities and creating livable environments. In 2022, the Ministry of Civil Affairs issued a significant announcement launching a two-year pilot initiative targeting the construction of “elderly and child-friendly facilities” in response to public concerns. This initiative aims to enhance public service delivery, diversify convenience-oriented services, and strengthen foundational aspects of community safety. Policy directions have increasingly crystallized around prioritizing elderly and children populations, establishing clear guidelines for age-adaptive and child-friendly transformations.

- (4)

- Design Recommendations and Policy Implications

Building upon the bibliometric and comparative analysis, this study proposes a series of integrated design and policy recommendations for governments and urban decision-makers. Firstly, it is essential to develop segment-based street design guidelines that establish differentiated standards for child-friendly, elderly-friendly, and all-age-shared street types, thereby reflecting the distinct behavioral needs of each group. Furthermore, visual comfort assessment tools, such as eye-tracking and streetscape image analysis, should be incorporated to construct a quantifiable emotional comfort evaluation system. Concurrently, implementing micro-scale spatial interventions—including resting nodes, interactive installations, and universal accessibility facilities along pedestrian routes—can significantly enhance dwell time and spontaneous social interaction. To ensure these designs are genuinely responsive, community co-design mechanisms must be promoted. This entails tailoring participatory tools for children and the elderly within the design process, such as employing “Participatory Mapping” and “model co-creation” for children, and organizing “focus groups” combined with “tangible, accessible physical models” for discussions with the elderly. This approach ensures they are not merely symbolic consultees but active co-creators of the design. Finally, achieving sustainable outcomes necessitates establishing cross-departmental street design review committees, led by the Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Development and integrating resources from Transport, Health, Civil Affairs, and other relevant departments. This committee should clearly delineate the mandates and boundaries of responsibility for all parties involved: the housing department would lead the formulation and implementation of physical spatial design standards; the transport department would be responsible for optimizing pedestrian and public transport connectivity and implementing traffic calming measures; the health department would provide health impact assessment indicators; and the civil affairs department would embed social mechanisms for community participation and long-term maintenance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.G., X.H. and X.Y.; methodology, X.G., X.H. and B.Z.; software, X.G.; validation, X.H., X.G. and X.Y.; formal analysis, X.G. and Y.W.; investigation, Y.W., T.Y. and X.G.; resources, X.G. and X.H.; data curation, X.G. and Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.G. and Y.W.; writing—review and editing, X.H., B.Z., T.Y. and M.W.; visualization, X.G. and Y.W.; supervision, X.H., B.Z. and M.W.; project administration, X.H. and B.Z.; funding acquisition, X.H. and M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52208039), Beijing Urban Governance Research Base Open Funding (2025CSZL13) and R&D Program of Beijing Municipal Education Commission (110052972508-06). We would also like to thank for the support in data collection from the College Students’ Innovative Entrepreneurial Training Plan Program (10805136025XN066-419).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, X. Investigation and Research on the Public Space of Main Blocks in American Cities Combining Big Data and PSPL Survey Method. Master’s Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Tang, J. A review of the research status and trends in all-age-friendly urban environments. World Archit. 2025, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facer, K.; Horner, L.K.; Manchester, H. Towards the All-Age Friendly City: Working Paper 1 of the Bristol All-Age Friendly City Group; Future Cities Catapult: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boys Smith, N. Heart in the Right Street; Create Streets: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Duany, A.; Plater-Zyberk, E.; Speck, J. Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, A.; Hollander, J.B. Cognitive Architecture: Designing for How We Respond to the Built Environment, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Ke, W. Spatiotemporal evolution characteristics and typical regional patterns of sub-aging and aging types in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2025, 80, 1520–1536. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J. The development history of scientific knowledge mapping. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2008, 26, 449–460. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrainy, H.; Khosravi, H. The impact of urban design features and qualities on walkability and health in under-construction environments: The case of Hashtgerd New Town in Iran. Cities 2013, 31, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chau, C.; Ng, W.; Leung, T. A review on the effects of physical built environment attributes on enhancing walking and cycling activity levels within residential neighborhoods. Cities 2016, 50, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesaniemi, Y.K.; Danforth, E.; Jensen, M.D.; Kopelman, P.G.; Lefèbvre, P.; A Reeder, B. Dose-response issues concerning physical activity and health: An evidence-based symposium. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, S351–S358. [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Knuiman, M.; Timperio, A.; Van Niel, K.; Pikora, T.J.; Bull, F.C.; Shilton, T.; Bulsara, M. Evaluation of the implementation of a state government community design policy aimed at increasing local walking: Design issues and baseline results from RESIDE, Perth Western Australia. Prev. Med. 2008, 46, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Xu, M.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Z. The walking friendliness of ladder trails for the elderly: An empirical study in Chongqing. Front. Arch. Res. 2022, 11, 830–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, T.E. The relative influence of urban form on a child’s travel mode to school. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2007, 41, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Chow, L.-F.; Li, M.-T.; Ubaka, I.; Gan, A. Forecasting transit walk accessibility: Regression model alternative to buffer method. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2003, 1835, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajna, S.; Ross, N.A.; Brazeau, A.-S.; Bélisle, P.; Joseph, L.; Dasgupta, K. Associations between neighbourhood walkability and daily steps in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cerin, E.; Conway, T.L.; Adams, M.A.; Frank, L.D.; Pratt, M.; Salvo, D.; Schipperijn, J.; Smith, G.; Cain, K.L.; et al. Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 2016, 387, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, H. Application of space syntax in the age-adaptive design of living streets: A case study of Binjiang Road in Yibin City. Beauty Times (Urban Ed.) 2024, 2, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X. Investigation and research on the age-adaptability of living street space based on PSPL survey method: A case study of Siping Community in Shanghai. Archit. Cult. 2024, 1, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Zhu, X.; Ji, W. Research on urban street space design based on child-friendly concept. Eng. Technol. Res. 2024, 9, 181–184+207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, C.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, S. Research on the spatial effects of urban street age-friendliness levels combining street view imagery and machine learning. J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2024, 26, 1469–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, C.L.; Carlson, N.E.; Bosworth, M.; Michael, L. The relation between neighborhood built environment and walking activity among older adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 168, 461–468. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S. Research on the Renewal Strategy System of Old Urban Communities from the Perspective of All-Age Friendliness. Master’s Thesis, China Academy of Urban Planning & Design, Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Chen, K. Research on child-friendly city: A case study of Pearl District, Portland, USA. Urban Dev. Stud. 2016, 23, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W. International practices and enlightenment of age-adaptive renewal in all-age communities. Archit. Cult. 2023, 8, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. Big City, Small Things: Seeing the Big Picture Through Small Details. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Harmer, P.A.; Cardinal, B.J.; Bosworth, M.; Acock, A.; Johnson-Shelton, D.; Moore, J. Built environment, adiposity, and physical activity in adults aged 50–75. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 35, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, D. Research progress on walkability measurement in the United States and its enlightenment. Urban Plan. Int. 2012, 27, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, L.; Kerr, J.; Rosenberg, D.; King, A. Healthy aging and where you live: Community design relationships with physical activity and body weight in older Americans. J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7 (Suppl. S1), S82–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creatore, M.I.; Glazier, R.H.; Moineddin, R.; Fazli, G.S.; Johns, A.; Gozdyra, P.; Matheson, F.I.; Kaufman-Shriqui, V.; Rosella, L.C.; Manuel, D.G.; et al. Association of neighborhood walkability with change in overweight, obesity, and diabetes. JAMA 2016, 315, 2211–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, H.; Ren, C. Review of “The experience, challenges and prospects of American TOD”. Urban Plan. Overseas 2004, 6, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. Study on the Evolution of Spatial Structure in Mountainous Towns. Ph.D. Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Research on Planning Strategies for Urban Elderly-Friendly Communities Oriented Towards Aging in Place. Ph.D. Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhi, W.; Zhu, C. Sustainable futures: Overview of UIA2023 Copenhagen World Congress of Architects. Time + Archit. 2023, 5, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Long, Y.; Batty, M. Review and prospect of urban models: New thinking after an interview with Michael Batty. City Plan. Rev. 2014, 38, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Yuan, Q.; Yu, T. International experience and enlightenment of dynamic adaptive planning for cities coping with climate change uncertainty. Urban Plan. Int. 2021, 36, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Editorial Department of China Journal of Highway and Transport. Review of academic research on traffic engineering in China: 2016. China J. Highw. Transp. 2016, 29, 1–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. Setting paths for urban spatial growth based on green infrastructure and its application in Hangzhou. Urban Plan. Forum 2017, 236, 104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, Q. Big data based urban rural planning decision making theory and practice. Planners 2014, 30, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, F.; Liu, W.; Zhang, M.; Hu, T.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, H.; Sui, F.; Wang, T.; Xu, H.; Huang, Z.; et al. Five-dimensional model and ten applications of digital twin. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2019, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M. Research on the Design of Urban Park Furniture Based on Humanized Concept. Master’s Thesis, Sichuan Agricultural University, Sichuan, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Liu, T. Research on inclusive design and construction of small public spaces under the concept of all-age friendliness. World Archit. 2024, 6, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yin, L. Creating healthy cities: Application of planning spatial technology in public health research. Shanghai Urban Plan. Rev. 2017, 3, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).