Spatial Performance Optimization of High-Altitude Residential Buildings Based on the Thermal Buffer Effect: A Case Study of New-Type Vernacular Housing in Lhasa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

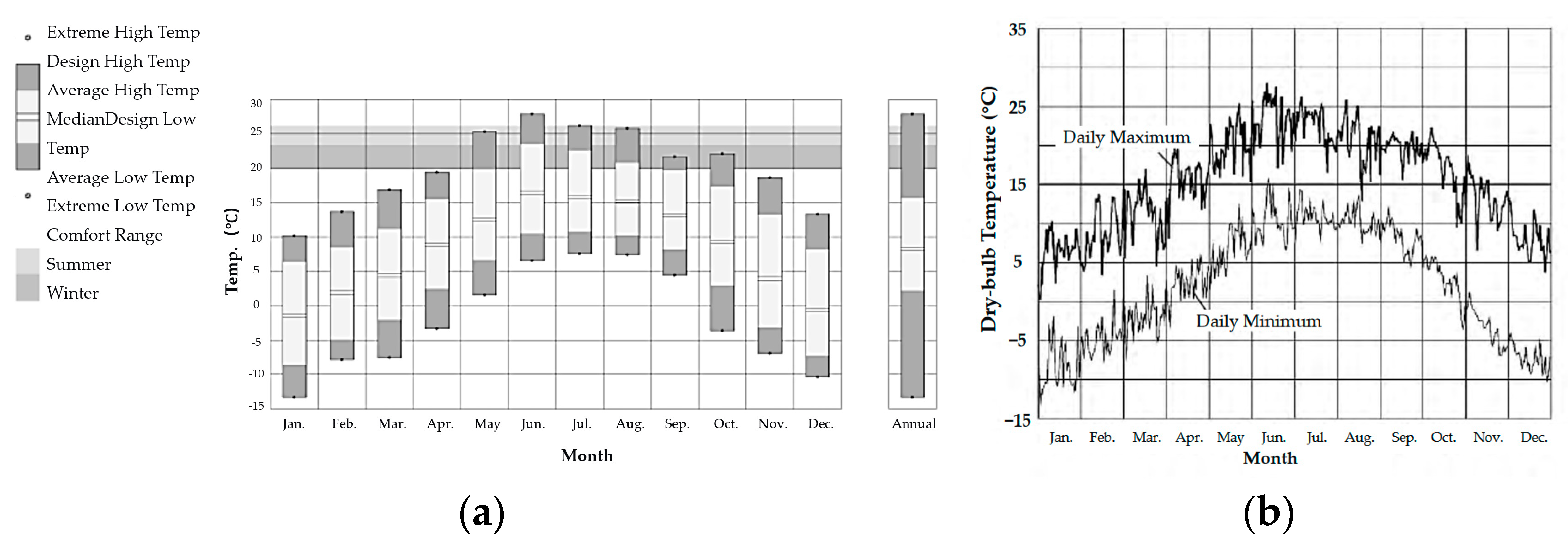

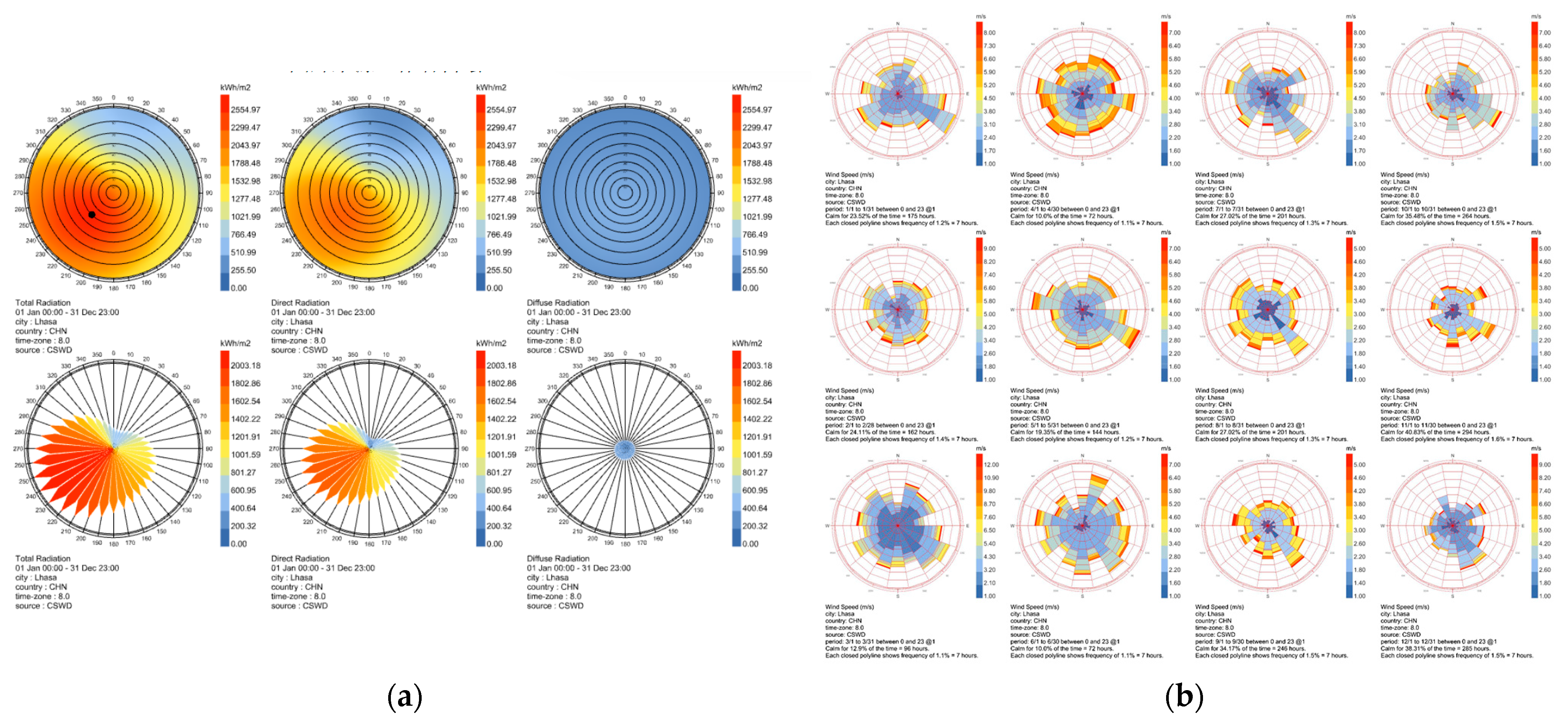

2.1. Case Study and Climate Data

2.2. Thermal-Buffer Framework: Thermal Buffer Strategies

2.2.1. Spatial Hierarchy

2.2.2. Additional Boundaries

2.3. Baseline Definition and Assumptions

2.4. Model Development and Spatial Zoning

2.4.1. Geometric Modeling and Prototype Selection

2.4.2. Spatial Zoning and Functional Grading

2.4.3. Thermal Buffer Boundary Space Modeling

2.4.4. Model Validation and Experimental Design

2.5. Envelope and Material Properties

2.6. Simulation and Optimization Framework

- (1)

- Building–Environment Information Module

- (2)

- Performance Calculation Module

- (3)

- Optimization and Output Module

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Baseline Thermal Environment and Space-Type Definition

3.2. Scale Effects and Functional-Grading Response

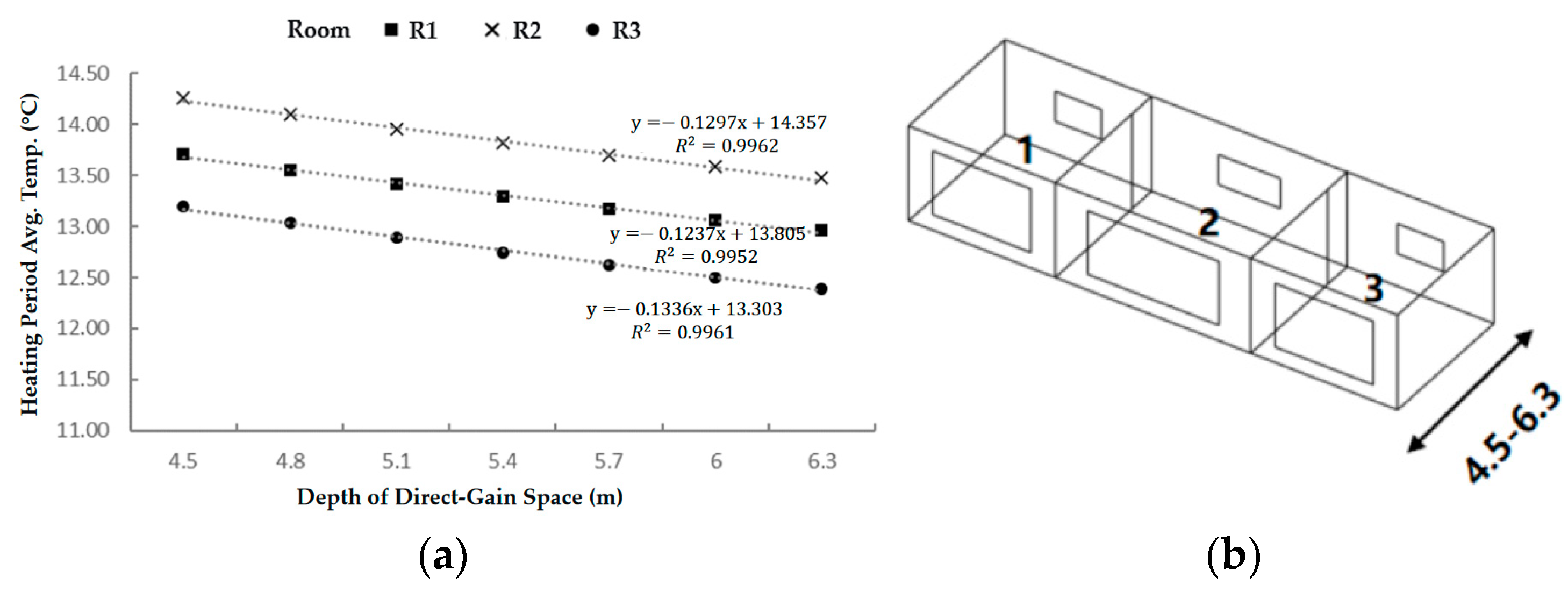

3.2.1. Horizontal Scale Effects of Layout

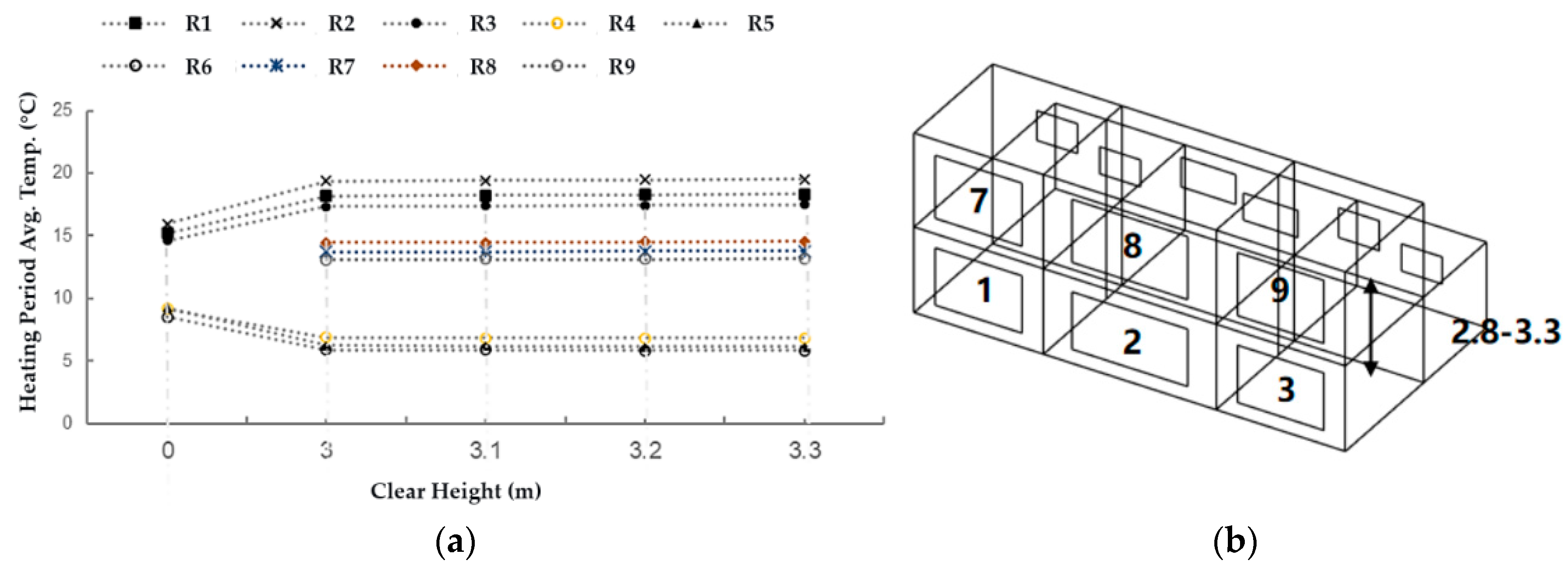

3.2.2. Vertical Scale Effects of Layout

3.2.3. Functional Spatial Thermal Comfort Grading and Application Effects

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Boundary-Space Parameters

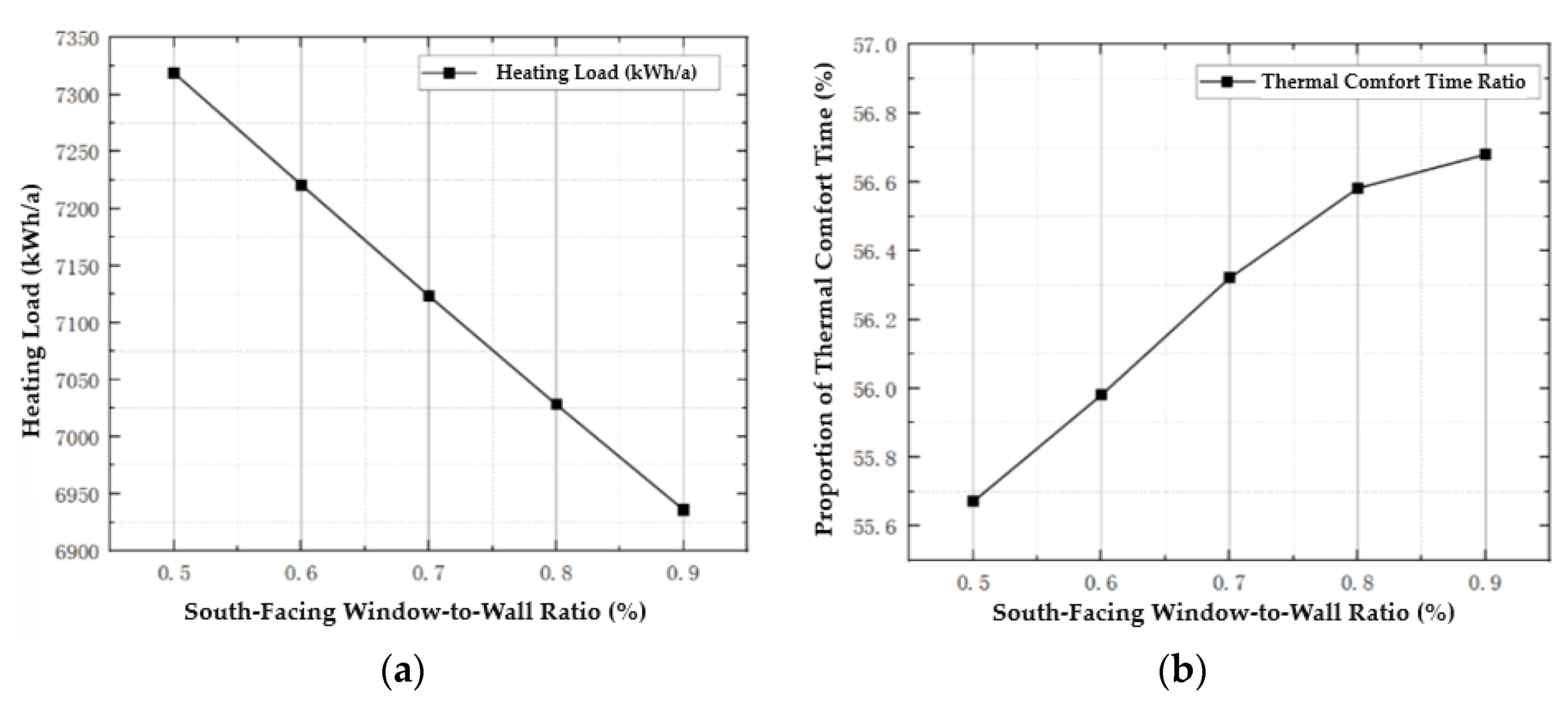

3.3.1. Sunspace (South-Facing)

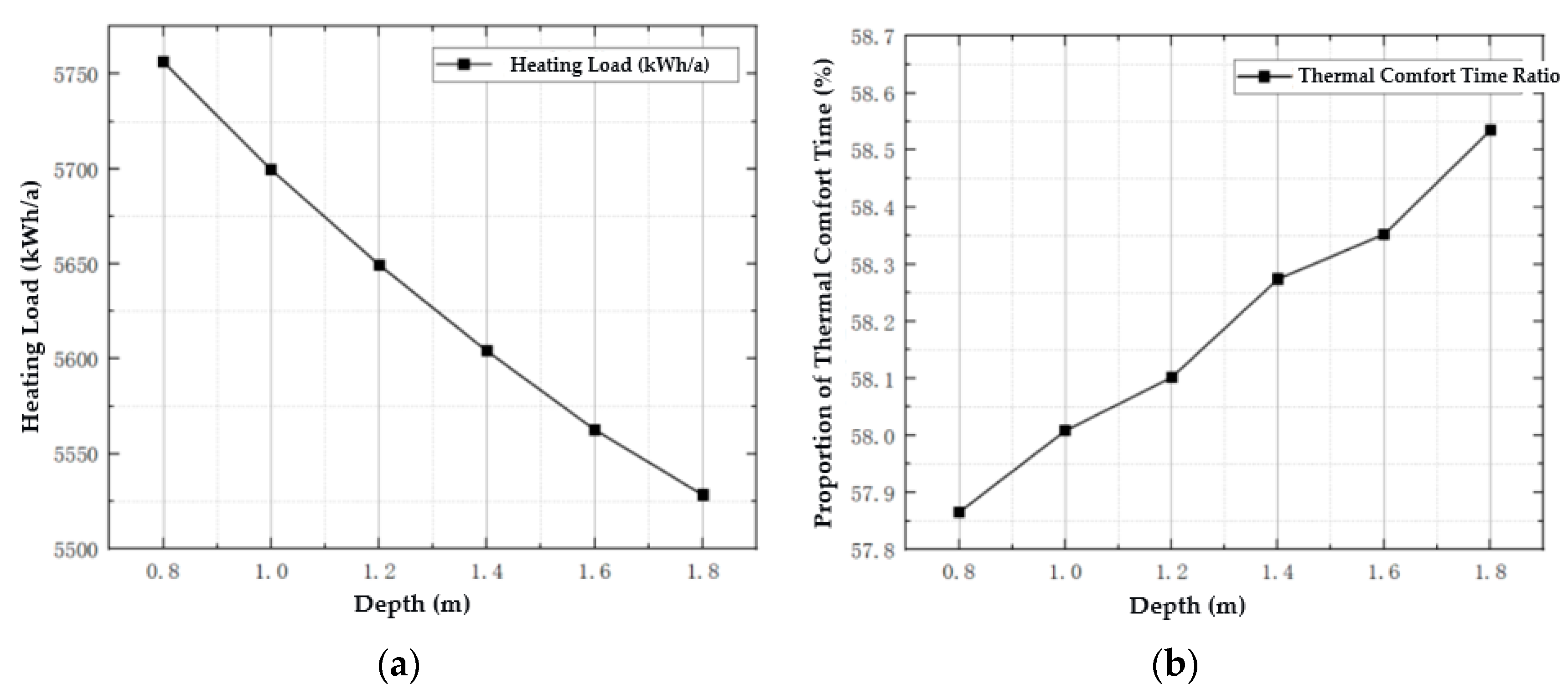

3.3.2. North-Facing Enclosed Corridor

3.3.3. Attic Roof Cavity

3.3.4. Sensitivity Ranking and Design Thresholds

3.4. Multi-Objective Optimization Results

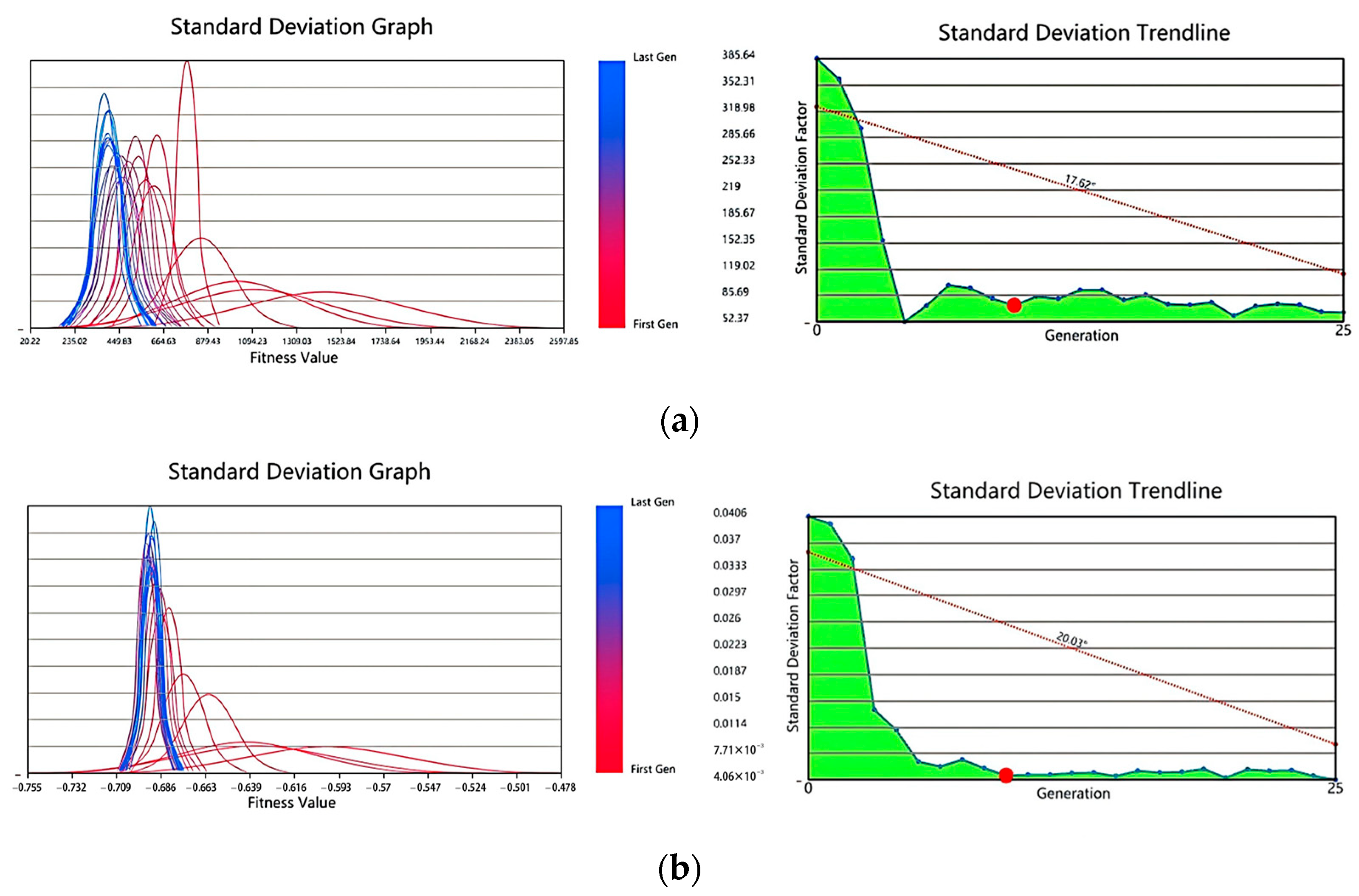

3.4.1. Convergence Behavior and Search Quality

3.4.2. Pareto Fronts and Comparative Potential

3.4.3. Compromise Solutions and Optimization Outcomes

3.4.4. Decision Patterns in the Compromise Set

3.5. Optimized Schemes and Performance Improvements

3.5.1. Energy and Comfort Gains

3.5.2. Thermal Distribution and Spatial Improvement

3.5.3. Validation and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsinghua University Building Energy Research Center. Annual Report on China Building Energy Efficiency 2025; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2025. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. New Countryside, New Plateau: A Review of the “11th Five-Year Plan” Settlement Project in Tibet Autonomous Region. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/gzdt/2010-12/07/content_1760686.htm (accessed on 31 October 2025). (In Chinese)

- People’s Government of Tibet Autonomous Region. Conference on the Construction of Settlements for Farmers and Herders in the Entire Region Convened. Available online: https://www.xizang.gov.cn/xwzx_406/bmkx/201812/t20181216_17779.html (accessed on 31 October 2025). (In Chinese)

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Notice on Issuing the “13th Five-Year Plan Period Poverty Alleviation and Relocation Work Plan”. Available online: https://www.waizi.org.cn/law/13276.html (accessed on 31 October 2025). (In Chinese).

- State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. White Paper on Peaceful Liberation and Prosperous Development of Tibet; State Council Information Office: Beijing, China, 2021. (In Chinese)

- Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J. Analysis of Factors Influencing Indoor Thermal Environment in Lhasa’s New Vernacular Dwellings in Winter. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 51, 109–115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Gao, H.; Liu, D.; Zhu, X. Study on Energy-Saving Optimization of Traditional Dwellings in Lhasa. Archit. Cult. 2019, 15, 241–243. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Deng, C.; Lan, B. Comparative Analysis of Indoor Thermal Environment in Traditional and New Vernacular Dwellings in Lhasa Rural Areas in Winter. Build. Sci. 2012, 28, 61–66. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020.

- ISO 7730:2005; Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Analytical Determination and Interpretation of Thermal Comfort Using Calculation of the PMV and PPD Indices and Local Thermal Comfort Criteria. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- Zhao, Q.; Xie, Y.; Li, Z. Thermal Performance Requirements for Wall Structures of Vernacular Dwellings in Lhasa Area. Hous. Sci. 2021, 41, 51–57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. The Optimization of the Insulation and Heat Storage of Rural Residential Building Envelope in Lhasa Region. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2017. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Q. Performance-Oriented Extraction and Reconstruction of Residential Forms in Lhesa. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, D.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Hao, A. Optimizing Building Envelope Dimensions for Passive Solar Houses in the Qinghai-Tibetan Region: Window-to-Wall Ratio and Depth of Sunspace. J. Therm. Sci. 2019, 28, 1115–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Editorial Board of Master Series. The Works and Ideas of Thomas Herzog; China Electric Power Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Han, P.; Mei, H. Ecological Design on Buffer Cavity of Buildings in Cold Region. Architect 2015, 56–65. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=BVV9sVd_tjEWcE6Cq6L4SyovLYPyiu_Q5-Nucr6wbLUSz2nlaWGEVeZSQ-4F1TjewgQP-1Jmy0uYZ-e3qokdEwHJ5ANa8wW28Frfv-1G1_bgl0WJ3K4l3fDumBl-5-UgSAiwszSBfmCoDVzhj4M1asLHpIeqcDjAhLtXGr_aSSw=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 22 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Song, C.; Wang, D. Heating Load Reduction Characteristics of Passive Solar Buildings in Tibet, China. Build. Simul. 2022, 15, 975–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Kang, J. Thermal Comfort in Winter Incorporating Solar Radiation Effects at High Altitudes—Case of Lhasa. Build. Simul. 2021, 14, 1633–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Mahapatra, S.; Atreya, S.K. Thermal Comfort Study of Himalayas in India: A Comparative Analysis of Traditional and Modern Houses. Build. Environ. 2019, 151, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzaglia, N.; Ochoa, C.E.; Caicedo, D.; Leiva, C.; Figueroa, R. On the Passive Cooling and Thermal Comfort in Buildings in the Andean Highlands of Ecuador. Energy Build. 2021, 231, 110597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albatayneh, A. Optimising the Parameters of a Building Envelope in the East Mediterranean Saharan, Cool Climate Zone. Buildings 2021, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Xin, Q.; Kou, X.; Song, J. Energy-Efficient Design of Immigrant Resettlement Housing in Qinghai: Solar Energy Utilization, Sunspace Temperature Control, and Envelope Optimization. Buildings 2025, 15, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Xu, F.; Lu, W.; Yang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Wen, B. Green Renovation and Multi-Objective Optimization of Tibetan Courtyard Dwellings. Build. Environ. 2025, 279, 113071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50176-2016; Code for Thermal Design of Civil Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2016. (In Chinese)

- Chen, L. Energy-Saving Design Methods for Rural Residential Buildings in the U-Tsang Region Based on Architectural Form. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, H. Research on the Architectural Evolution of Tibetan Vernacular Dwellings in Lhasa after the Founding of the People’s Republic of China. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Hamza, N.; Lan, B.; Zuo, J. Climate-Responsive Design of Traditional Dwellings in the Cold-Arid Regions of Tibet and a Field Investigation of Indoor Environments in Winter. Energy Build. 2016, 128, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50736-2012; Design Code for Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning of Civil Buildings. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012. (In Chinese)

- Chen, L. Research on the Design of Courtyard-Style Dwellings in Lhasa Based on Solar Radiation Heat Utilization. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, J. Experimental Study on the Design Application Prioritizing Solar Radiation Heat Utilization in Courtyard-Style Dwellings in Lhasa. Archit. Technol. 2022, 28, 80–83. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K. Integration of Green Building Design Concepts in Architectural Engineering Design. Policy Res. Explor. 2020, 27. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=BVV9sVd_tjHR-KF46yrtj747aiCeaNJyEI7mQa0kH7nyINn1RldIpJXfqB5aIVlJoztCGGrHTKwIOUS1FL4KeZjt5EHR6VPbpiHCUD9a1zS_YQxlwhko6MY5jVYNLdwzSlLlumXGoM4504I3w19gNF9YtJzF1CKeiZW8CvKo8qA=&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 22 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Liu, J.; Wu, L. New Energy utilization in Architectural Energy Conservation and Design. Energy Eng. 2001, 2, 12–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W. Research on Design Strategies for Building Composite Interfaces Based on Spatial Thermal Buffer Effects. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Analysis of Architectural Spatial Hierarchy and Its Constructive Expression. Master’s Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2017. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Gao, Y. Analysis of Thermal Performance and Energy-Saving Strategies for Rural Residential Buildings in Northwest China. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 47, 427–432. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, G.; Han, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, J. Influence of Spatial Zoning on Differentiated Indoor Temperatures in Solar Buildings. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2016, 37, 2902–2908. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y. Study on the Influence of Sunspace on Indoor Thermal Environment Comfort in Rural Dwellings in Cold Regions. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Jianzhu University, Jinan, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Ulpiani, G.; Giuliani, D.; Romagnoli, A.; Cataldo, M.D. Experimental Monitoring of a Sunspace Applied to a NZEB Mock-Up: Assessing and Comparing the Energy Benefits of Different Configurations. Energy Build. 2017, 152, 194–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, D.; Athienitis, A.K. Analysis of the Solar Radiation Distribution and Passive Thermal Response of an Attached Solarium/Greenhouse; Concordia University: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Lan, B. Analysis of Heating Energy Consumption and Indoor Thermal Environment of Traditional Dwellings in the Old City of Lhasa. Build. Energy Effic. 2014, 42, 1–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Q. Research on Climate-Adaptive Design Strategies for Vernacular Buildings in the Valley Plain Area of Lhasa City. Master’s Thesis, Tibet University, Lhasa, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 55038-2025; Residential Building Code. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2025. (In Chinese)

- Mao, Z.; Xuan, H. A Study on the Spatial Layout of Buildings Based on Thermal Buffer: Taking the New-Style Residential Houses in Lhasa as an Example. Intell. Build. Smart City 2025, 88–91. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A Fast and Elitist Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, W. Co-Optimization of Passive Building and Active Solar Heating Systems Based on the Objective of Minimum Carbon Emissions. Energy 2023, 275, 127401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Fang, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J. Multi-Objective Optimization of Passive Design Parameters for Rural Residences Based on GA-BP-NSGA-II: A Case Study of Cold Regions in China. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 112, 113624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, Y. Research on Design Guidelines for Solar Radiation Utilization in Urban Residential Buildings: A Case Study of Five Cities in Solar-Rich Regions; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2022. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Item | Setting |

|---|---|

| Weather and timestep | CSWD (TMY), Lhasa station (29.67° N latitude and 91.13° E longitude); hourly |

| Simulation periods | Heating season: Nov 15–Mar 15; Coldest day: Jan 3 |

| HVAC | Pattern identification: heating OFF; Optimization stage: heating ON per setpoints |

| Cooling | OFF |

| Infiltration/Ventilation | 0.3 h−1/0.5 h−1 |

| Internal gains | 0 (occupants, lighting, equipment) |

| Heating setpoints | 18 °C (primary), 15 °C (secondary), 14 °C (auxiliary) |

| Constructions | Self-built: stone–masonry walls, reinforced-concrete roofs. Government-designed: composite insulated walls with hollow concrete blocks. (Detailed assemblies and U-values are provided in Section 2.5.) |

| Window-to-wall ratios | South: 0.45–0.50; North: ≤ 0.10; East/West: 0.00–0.05. (Specific values by prototype are detailed in Section 2.5.) |

| External obstructions | Not modeled (open-sky condition) |

| Solar model | Ladybug–EnergyPlus coupling using CSWD solar and radiation data |

| Comfort model and criterion | APMV per GB 50736-2012; Class II (−1 ≤ APMV ≤ 1) |

| Outputs | Heating load (kWh/a, kWh/m2·a); thermal comfort (HSP); temperature and surface flux data |

| Category | Variable | Value/Range Description | Purpose/Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal Layout | Room Depth-to-Width Ratio | Typical Range: Depth 4–8 m, Width 3–6 m | To analyze the influence of horizontal dimensions on temperature distribution. |

| Vertical Layout | Number of Functional Floors | One Story, Two Stories, Three Stories | To verify the thermal environmental advantages of intermediate floors. |

| Functional Zoning | Space Tier | Primary, Secondary, Auxiliary | To hierarchically adapt to differentiated thermal comfort requirements. |

| Category | Variable | Value/Range Description | Purpose/Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunspace | Form | Projecting, Recessed, Semi-projecting | To compare daylighting and heat gain effects of different spatial forms. |

| Window-to-Wall Ratio | 0.4–1.0 | To balance heat gain and heat loss. | |

| Depth | 1.0–3.0 m | To control solar radiation utilization and energy consumption. | |

| Glazing Type | Single-pane, Double-pane Low-E | To compare differences in heat gain and insulation performance. | |

| Roof Slope | 25–65° | To optimize heat collection efficiency in regions with low solar altitude. | |

| Skylight Area Ratio | 0–20% | To analyze the impact of additional daylighting and heat dissipation. | |

| North-facing Corridor | Depth | 1.0–2.5 m | To evaluate the heat loss buffering effect. |

| Attic Space | Cavity Height | 0–2.3 m | To regulate the stability of the top-floor thermal environment. |

| Insulation Thickness | 0–200 mm | To reduce heating load and improve overall insulation performance. |

| Envelope Component | Layer Description and Thickness | Thickness (m) | Thermal Conductivity (W/(m·K)) | Density (kg/m3) | Specific Heat Capacity (J/(kg·K)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Wall | Cement plaster | 0.020 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 |

| Stone brick | 0.580 | 1.160 | 2000 | 920 | |

| Cement plaster | 0.020 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 | |

| Internal Wall | Stone brick | 0.560 | 1.160 | 2000 | 920 |

| Cement plaster | 0.020 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 | |

| Roof | Cement plaster | 0.020 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 |

| Reinforced concrete | 0.120 | 1.740 | 2500 | 920 | |

| Cement plaster | 0.020 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 | |

| Roofing felt | 0.003 | 0.170 | 600 | 1470 | |

| Floor Slab | Cement plaster | 0.020 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 |

| Reinforced concrete | 0.120 | 1.740 | 2500 | 920 | |

| Cement plaster | 0.020 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 |

| Envelope Assembly | Material Description | U-Value (W/m2·K) | Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exterior Window | Single-pane glazing with aluminum alloy frame | 6.5 | 0.73 |

| Envelope Assembly | Material Layer | Thickness (m) | Thermal Conductivity (W/(m·K)) | Density (kg/m3) | Specific Heat Capacity (J/(kg·K)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Wall | Cement plaster | 0.020 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 |

| Inorganic insulation mortar | 0.030 | 0.180 | 600 | 1050 | |

| Concrete hollow block | 0.300 | 0.750 | 1500 | 920 | |

| Inorganic insulation mortar | 0.030 | 0.180 | 600 | 1050 | |

| Cement plaster | 0.020 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 | |

| Cement plaster | 0.020 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 | |

| Internal Wall | Concrete hollow block | 0.200 | 0.750 | 1500 | 920 |

| Cement plaster | 0.020 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 | |

| Cement plaster | 0.050 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 | |

| Roof | XPS (Extruded Polystyrene) | 0.150 | 0.028 | 32 | 1380 |

| Reinforced concrete | 0.100 | 1.740 | 2500 | 920 | |

| Cement plaster | 0.020 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 | |

| Cement plaster | 0.020 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 | |

| Floor Slab | Reinforced concrete | 0.120 | 1.740 | 2500 | 920 |

| Cement plaster | 0.020 | 0.930 | 1800 | 1050 |

| Envelope Assembly | Material Description | U-Value (W/m2·K) | Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exterior Window | Aluminum alloy frame, double-glazed window (4 mm + 12 A Argon + 4 mm, medium-transmittance glass) | 2.67 | 0.49 |

| Orientation | South Facade | East and West Facades (Gable Walls) | North Facade |

|---|---|---|---|

| WWR | 0.45–0.50 | 0.00–0.05 | ≤0.10 |

| Unit | Variable | Value Range | Data Type | Step Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Heat Gain Space | Depth | 4.6–6.3 m | Continuous | 0.3 |

| Width | 0.0–4.5 m | Continuous | 1.5 | |

| Clear Height | 2.8–3.3 m | Continuous | 0.1 | |

| Heat Loss Buffer Space | Depth | 3.6–4.5 m | Continuous | 0.3 |

| Clear Height | 2.8–3.3 m | Continuous | 0.1 |

| Grade | Spatial Combination and Shading/Buffer Characteristics | Typical Spatial Attributes (DHS/LBS) | Temperature Performance During Heating Period (Key Results) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Unshaded, south-facing DHS, with buffer spaces on east, west, and north sides | DHS (multi-sided buffer) | Highest average temperature, smallest diurnal variation |

| II | Unshaded DHS, with buffer spaces on two sides | DHS (double-sided buffer) | High average temperature, relatively small variation |

| III | Unshaded DHS, with only one-sided buffer or central space | DHS/Central | Moderate average temperature, moderate variation |

| IV | Obvious shading, buffer spaces on both sides | DHS/LBS (shaded) | Relatively low average temperature, relatively large variation |

| V | Shaded, only one-sided buffer (mostly north-facing LBS) | LBS (single-side buffer) | Lowest average temperature, significant night drop |

| ID | Make-Up | Thermal Transmittance [W/(m2·K)] | SHGC |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 6 clear + 12 air + 6 clear | 2.8 | 0.75 |

| G2 | 6 HT Low-E + 12 air + 6 clear | 1.9 | 0.47 |

| G3 | 6 MT Low-E + 12 air + 6 clear | 1.8 | 0.37 |

| Category | Parameter | Trend (Load) | Key Threshold (This Study) | HSP Effect (Qual.) | Design Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunspace | Depth | ↑ (Assembly 1); ↓ (Assembly 2 rooftop case) | 2.0–2.5 m | slight ↓ at extremes | High |

| South-facing WWR | ↓ (until loss penalty) | ≤0.8 (use high-transmittance glazing where needed) | ↑ to ~+1%/10% step, then taper | High | |

| SRR (skylight-to-roof) | ↓ (to a point) | ≤0.10 | ↑ then ↓ beyond ~0.10 | High | |

| Roof slope (tilt) | ↓ when tilted toward winter altitude; ↑ if too flat | Moderate tilt near winter solar altitude (~36.6°) | stable if not over-steep | Medium | |

| Glazing type | depends on U vs. SHGC | High-transmittance Low-E or clear double (solar-gain priority) | stability ↑ with Low-E | High | |

| Wall material | ↓ with lower λ | Low-λ wall (e.g., aerated concrete) | capacity can aid HSP | Medium | |

| Floor material | ↓ with lower λ | Low-λ floor (e.g., fly-ash ceramsite) | high capacity improves HSP | Medium | |

| Corridor | Depth | ↓ with diminishing returns | 1.5–2.0 m | slight ↑ | Medium |

| Attic | Insulation thickness | ↓ (monotonic) | ≈ 150 mm (knee) | slight ↑ | Medium |

| Cavity height | slight ↑ if too tall | Moderate (avoid excessive height) | slight ↓ if too tall | Low–Medium |

| Prototype Type | Optimal Solution ID (Gen, Idv) | Heating Load (kWh/a) | HSP (%) | Selection Basis (Euclidean Distance) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-built | Gen19, Idv3 | 2541.22 | 62.17 | Compromise (Euclidean distance) |

| Gen14, Idv1 | 3102.54 | 64.55 | Comfort optimum | |

| Gen12, Idv24 | 3049.68 | 64.54 | Near-comfort optimum | |

| Government | Gen19, Idv0 | 304.48 | 68.27 | Compromise (Euclidean distance) |

| Gen19, Idv1 | 561.78 | 69.96 | Comfort optimum |

| Prototype | Scheme Stage | Heating Load (kWh/a) | Energy-Saving Rate (vs. Baseline) | HSP (%) | Improvement Rate (vs. Baseline) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-built | Baseline | 12,465.81 | – | 30.95 | – |

| Layout-optimized | 7611.70 | 38.93% | 35.70 | 15.35% | |

| Final optimized | 2541.22 | 79.61% | 62.17 | 50.20% | |

| Government | Baseline | 6631.39 | – | 32.00 | – |

| Layout-optimized | 6152.62 | 7.22% | 37.73 | 17.90% | |

| Final optimized | 815.53 * | 87.70% | 69.65 | 54.06% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, X.; Mao, Z.; Xuan, H. Spatial Performance Optimization of High-Altitude Residential Buildings Based on the Thermal Buffer Effect: A Case Study of New-Type Vernacular Housing in Lhasa. Buildings 2025, 15, 4337. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234337

Ma X, Mao Z, Xuan H. Spatial Performance Optimization of High-Altitude Residential Buildings Based on the Thermal Buffer Effect: A Case Study of New-Type Vernacular Housing in Lhasa. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4337. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234337

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Ximeng, Zhen Mao, and Huang Xuan. 2025. "Spatial Performance Optimization of High-Altitude Residential Buildings Based on the Thermal Buffer Effect: A Case Study of New-Type Vernacular Housing in Lhasa" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4337. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234337

APA StyleMa, X., Mao, Z., & Xuan, H. (2025). Spatial Performance Optimization of High-Altitude Residential Buildings Based on the Thermal Buffer Effect: A Case Study of New-Type Vernacular Housing in Lhasa. Buildings, 15(23), 4337. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234337