Abstract

In recent decades, with the urgent need to move toward more low-carbon and sustainable development, green infrastructure (GI) has gained increased attention. Due to the complexity and uniqueness of GI, and involvement of numerous organizations, it is imperative to address it via inter-organization collaborative innovation effectively. However, few studies have explored the dynamic evolution of collaborative innovation in GI and how proximity mechanisms drive collaborative innovation (CI). To explore CI in GI, this study is based on 610 patents in the field of GI in China from 2010 to 2024 and uses social network analysis (SNA) to construct CI networks, applying the Exponential Random Graph Model (ERGM) to explore the driving factors of CI in GI, with a specific focus on the driving effect of multidimensional proximity on CI. The results show that the network density decreases from 0.153 to 0.033, and the average path length remains below 3.4, presenting typical small-world characteristics. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that multidimensional proximity drives the evolution of CI in GI. Among them, the positive driving effect of social proximity is the most significant, while the coefficient of geographical proximity decreased from 2.83 in the budding stage to 0.003 in the mature stage. Similarly, the coefficient of technical proximity decreased from 2.528 to 1.735, indicating that its driving effect gradually weakened. These results contribute to the theory implications regarding dynamic perspectives for complex CI relationships in GI, and provide useful guidance for effectively allocating resources and talent training.

1. Introduction

Currently, overcrowding, urban sprawl, and polluted air and water have led to a growing need for green infrastructure (GI), including highways, railways, bridges, airports, and so on [1]. GI provides a service for humanity and benefits the environment, society, and the economy [2]. Internationally, the European Union has integrated GI into its “Green Deal” and “Biodiversity Strategy 2030”, mandating that member states incorporate ecological engineering into the expansion of the TEN-T core network to mitigate urban heat island effects and flood risks [3]. Similarly, in the United States, the Federal Highway Administration has advanced the use of low-carbon materials through its “Green Highway Initiative”, underscoring GI’s potential to reduce lifecycle maintenance costs and strengthen climate resilience [4]. However, GI demands new technology, materials, and construction processes to improve urban life and sustainability and minimize climate change [4]. Therefore, due to the complexity and uniqueness of GI, the innovation and development of new technologies have become an inevitable trend [5].

In the view of the participants, innovation factors in the process of GI, when driven by a solitary organization, are considered insufficient in addressing technological hurdles [6]. Therefore, fostering collaborative innovation (CI) among organizations becomes imperative for unlocking technological advancements [7,8]. CI in GI involves the integration of innovation factors cross organization stakeholders [9]. Hence, CI among stakeholders is crucial for the success of GI. Significantly, CI among organizations can be conceptualized as a network. Close and stable networks are conducive to the innovation factors, dissemination and diffusion. Patents are considered an effective measure of the relationships among stakeholders and reflect CI [10]. Currently, a CI network structured on patents is a hot topic of research in various fields [11]. On the one hand, many studies have focused on the external structural characteristics of the collaborative network [10], lacking research on the driving factors of internal evolution. On the other hand, research has paid attention to specific projects, such as green building projects [11], but few have committed to studying the evolutionary underpinnings and driving factors of the CI network in GI [12]. For example, Ning and Tang [13] have established the green building technologies CI network via patents. Li et al. [14] conducted a study based on patents to explore the structural characteristics of global green technological collaboration networks. However, most literature chooses to explore the structural characteristics of CI networks from a static perspective, and few scholars analyze the intrinsic motivations behind the dynamic evolution of CI networks.

In addition, CI networks are affected by various factors. Mining these driving factors can help identify CI among organizations’ priorities and achieve efficient and sustainable technological innovation [11]. Currently, an emerging body of literature indicates that network structures and organization itself are attributed to driving the formation of CI relationships [15]. Remarkable, inter-organizational CI networks are always strongly related to the multidimensional proximity [16], which provides an important impetus for technological innovation and diffusion. Meanwhile, stakeholders with similar attributes are often more likely to participate in the process of CI [12]. Numerous studies have leveraged multidimensional proximity to explore its impact on CI. Ma et al. [16] investigated the multidimensional proximity effect on CI. In fact, the influence of proximity changes over time. However, scholars primarily analyze the impact of proximity from a static perspective, and few studies explore the dynamic impact of multidimensional proximity on CI in GI.

To address these gaps, this study aims to reveal the potential mechanisms of CI in GI and explore how multi-dimensional proximity affects the dynamic evolution of CI. Specifically, this study firstly uses GI patents in China to characterize the evolution features of CI networks in GI. Secondly, this paper identifies the roles and functional positioning of each organization in CI networks, and determines the innovation areas where these organizations are located during the process of CI. Finally, the dynamic impact of multi-dimensional proximity on CI was analyzed using the Exponential Random Graph Model (ERGM), and the changes in the intensity of the effect of each proximity dimension in the three stages were explored. The realization of the above research objectives will provide a new perspective for understanding the network evolution of CI in GI and offer empirical evidence for resource allocation and talent cultivation.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Green Infrastructure Projects

Given the growing contradiction between social development and environmental preservation [17], concepts like sustainable development and the green economy have emerged as central solutions to contemporary ecological challenges [18]. Green Infrastructure (GI) has gained prominence as a holistic approach that synergizes environmental protection, social progress, and economic growth [19]. GI is an innovative initiative to achieve low-carbon, green, and sustainable development [2], which refers to large-scale public works that have profound impacts on the environment, society, and the economy [20]. These projects encompass renewable energy, environmentally friendly transportation, green structures, and other forms of infrastructure [2]. The development of GI therefore represents a critical pathway for achieving long-term sustainability goals while addressing the urgent need for environmental stewardship.

GI is involved in all aspects of human life and has a profound impact on society [2]. But due to the rapid development of society and growing environmental problems, the current technology is insufficient to achieve the construction of GI [21]. Hence, innovation in GI is important in dealing with rapidly evolving societal and environmental challenges [19]. GI is characterized by complicated decision-making, huge complexity, and long implementation [22]. With the rapid development of GI, the scale of projects and the span of professional categories involved are increasing [23]. There is an intrinsic complexity in GI, which often induces alarming rates of failure [24]. Technological innovation has become an important method for dealing with complexity and improving performance in GI.

2.2. Technological Innovation in Green Infrastructure Projects

Compared with manufacturing, technological innovation in GI is oriented by construction demand [24]. The benefits of the technological innovation of GI can not only enhance project performance, but also create huge economic and social benefits. Therefore, technological innovation is essential to the completion of GI [25]. Given the importance of technological innovation in GI, it has recently received increasing attention. Due to technological innovation in GI relating to all innovation activities [12], Davies et al. [26] proposed four channels to promote innovation. Of noteworthy importance is that technological innovation is becoming an important determinant of GI’s sustainable development and project performance improvement.

A major source of technological innovation is interorganizational collaboration, which provides access to new knowledge and resources to solve technical difficulties [27]. Collaborative innovation among organizations can reduce innovation costs and share risks to improve innovation rates. Therefore, collaborative innovation has the characteristic of stimulating innovative development [28]. At the same time, without a high level of resources and ability, a desired level of innovation performance cannot be guaranteed only by participating in collaborative innovation activities [29]. Currently, collaborative innovation in GI has become an essential strategy for solving technical problems, particularly in enhancing innovation efficiency [30]. Collaborative innovation among stakeholders involved in the construction of GI promotes the aggregation of resources, knowledge, and professional skills, and stimulates common creativity, thereby achieving more efficient innovation.

2.3. Network Perspective on Collaborative Innovation

Network analysis can visualize interactions and communication patterns among organizations and has been applied to understand collaboration between stakeholders in infrastructure projects [31]. Similarly, Freeman suggested that networking is the most effective approach for characterizing inter-organizational collaborative relationships in the innovation process [32]. Collaborative innovation networks lead to an increasing interaction between different organizations, while achieving the optimal allocation of resources and promoting knowledge transfer performance [33]. Scholars indicate that collaborative innovation networks are important for the exchange of resources and information, which can provide complementary resources and lead to resource sharing [34]. Subsequently, most studies have examined collaborative innovation from a network perspective. For example, Zhang et al. [35] analyzed the structure of the project network in the process of innovation for sustainable construction based on an industry construction project in China. However, while most research has emphasized collaborative innovation networks at the firm and project level, few studies focused on the nature of collaborative innovation networks at the organizational level. Thus, it is necessary to analyze inter-organizational collaborative innovation from a network perspective.

At present, there are various methods to construct a collaborative innovation network, including award-winning and patents [2]. In particular, patents, as intellectual property rights for technology R&D, can not only analyze the history of industry technology, development models, characteristics, and trends [36], but also describe the collaborative innovation relationships among different organizations. Recently, a growing body of research has identified the collaborative innovation network in order to explore the collaborative innovation patterns among different organizations. Wang et al. [37] have depicted the temporal evolution of collaborative innovation networks, based on 223 projects receiving the Green Building Innovation Award in China. Zhang et al. [35] selected an industrial construction project in China as an example to explore the structural characteristics of collaborative innovation networks. These studies have provided a paradigm for the characterization and analysis of inter-organizational collaborative innovation [11]. Hence, we reveal the temporal evolution paths of collaborative innovation networks in GI through patents, and further explore the driving factors of collaborative innovation relationships in the field of GI.

2.4. Multidimensional Proximity and Collaborative Innovation

Multidimensional proximity plays an important driving role in CI [11]. Organizations with similar attributes are often more generally willing to participate in the process of CI [12]. As conceptualized by Boschma, proximity encompasses multiple dimensions—including geographical, organizational, social, and technological—each playing a distinct role in facilitating inter-organizational collaboration [38]. Firstly, geographical proximity promotes face-to-face transportation by reducing transportation and communication costs, thereby facilitating knowledge transfer and accelerating innovation efficiency [38]. Secondly, organizational proximity reduces institutional differences and coordination costs, making it easier for the two cooperating parties to align in terms of goals, processes, and cultures, thereby enhancing the stability and sustainability of collaborative innovation [39]. Secondly, stable social relationships can effectively reduce uncertainty and opportunism in cooperation, providing a crucial informal governance mechanism for high-risk and high-investment collaborative innovation. Finally, technical similarities among organizations are conducive to knowledge absorption and understanding, lowering the threshold for understanding and learning as well as the learning cost in the early stage of cooperation. At the same time, technological proximity promotes the exchange and integration of technical knowledge, thereby driving technological progress and the generation of innovative achievements.

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Framework

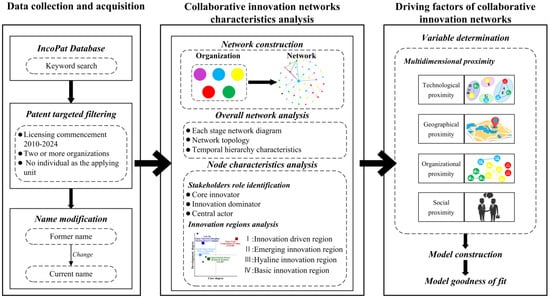

This paper discusses the characteristics of collaborative innovation in GI and its driving factors. Therefore, Figure 1 shows our research framework, which is divided into three parts, including: (1) Data collection and acquisition; (2) Collaborative innovation networks in GI characteristics analysis; and (3) Analysis of driving factors of collaborative innovation in GI.

Figure 1.

Research flowchart.

3.2. Research Data Depiction

Collaborative patents can characterize CI [40,41]. The patent data used in this paper is from the IncoPat database, which is a Chinese database that directly obtains patent data from the Patent Office [40]. GI involves construction, transportation, energy, agriculture, post and telecommunications, and other fields [20]. Given the broad scope of GI, and to focus on engineering construction and core technologies, this study primarily concentrates on GI innovations related to engineering construction technologies. This paper mainly studies engineering construction technology, and at the same time, the two-level keyword assembly structure of adjectives nouns was adopted in the query. The first-level keywords contain “bridge construction”, “railway construction”, “water conservation”, “electric power”, “civil construction”, “intelligent construction”, and “tunnel construction”; the second-level keywords are “sustainable”, “green”, and “low carbon”.

Due to the huge amount of data, it is necessary to clean and filter the data. First of all, this study takes China’s GI as its context; therefore, the patent number was set as “CN*” to focus on CI activities within China’s domestic GI sector. Secondly, in order to explore the CI relationship, this paper retained the patents with two or more applicants to obtain collaborative patents. Since the research object was CI between organizations, patents with individuals as the patentees were excluded to ensure the network nodes represent organizational entities. Considering the sparse data prior to 2010 and the noticeable acceleration of policy promotion and technological development in China’s GI field after 2010, the timeframe for this article is set from 2010 to 2024 to capture a more complete and relevant innovation cycle. Finally, the artificial search method was applied to screen out the collaborative patent data, totaling 610. Through the systematic keyword construction and multi-step filtering process described above, we aimed to ensure that the obtained patent data accurately and effectively reflect inter-organizational CI relationships in the field of GI in China.

3.3. Antecedent Variables

Multidimensional proximity is widely recognized as a major driver of innovation [42,43]. This study selects geographical proximity, technological proximity, social proximity, and organizational proximity to analyze the driving effect of CI in GI.

- (1)

- Geographical proximity (GP)

GP describes the similarity in geographical distance between stakeholders. It is specifically measured by obtaining the latitude and longitude coordinates of each organization’s registered address and calculating the pairwise Euclidean distance between organizations. The smaller the value, the closer the geographical location between the organizations.

- (2)

- Technology proximity (TP)

TP describes the degree of similarity among stakeholders on the basis of knowledge. The cost of communication and learning between organizations with similar technologies is relatively low, which is conducive to the circulation and transformation of resources between organizations [44].

- (3)

- Social proximity (SP)

SP reflects the closeness and distance of social relations between subjects, and there is a trust relationship between organizations with historical cooperation [44], which will have a lower fault tolerance rate and facilitate CI.

- (4)

- Organizational proximity (OP)

OP reflects the type similarity of stakeholders. Stakeholders of the same type often have similar social relations, organizational structure, and organizational culture, which helps to create a stable environment for both partners, promote coordination and communication, accelerate the spread of knowledge, and improve the efficiency of CI [45]. Table 1 shows the specific calculation methods for each variable.

Table 1.

Variables Selection.

4. Research Result

4.1. Development Stage of Collaborative Patents

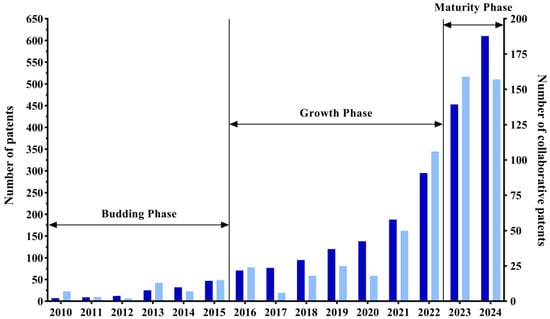

Technology life cycle analysis is a theory that can explain the historical development of technology and estimate the future trends or prospects, believing that the development of technology should go through the budding, growth, maturity, and decline phases [38]. S-curve analysis is a traditional methodology for technology life cycle analysis that helps us to estimate the level of development of a technology in each lifecycle phase. The software LogletLab 5.0 can fit the S-curve of technology development well [46,47]. Therefore, we analyzed the GI patent data, and the results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Phase division of CI in GI.

The evolution of CI in GI is divided into three phases: the budding phase (2010–2014), growth phase (2015–2022), and maturity phase (2023–2024). Overall, from 2010 to 2024, the total number of collaborative patents has shown an upward trend, indicating that the level of CI is strengthening. Specifically, in the budding phase, the number of collaborative patents was small, with an average of 6 patents applied for each year. Collaborative patents in the growth stage show an increasing trend on the whole. At the mature stage, the number of collaborative patents began to show an explosive growth, with a growth rate of 38.7%.

GI’s patents cover a wide range of technical fields, so this article analyzes the fields of collaborative patents for three phases. As can be seen from Figure 3, the technical fields of GI mostly exist in the fields of electricity, physics, and fixed buildings, and exhibit phased characteristics accordingly. During the growth phase, GI has carried out CI in the fields of electricity and physics, showing a gradual upward trend. GI occupies an important position for CI in the field of physics.

Figure 3.

Trend of technical domains in GI in 2010 to 2024.

4.2. CI Networks Evolution in GI

4.2.1. CI Networks Construction in GI

Social network analysis (SNA) is a comprehensive method that integrates graph theory and mathematical modeling to study complex networks [48], focusing on the interaction between actors and the evolution of their relationships. SNA is widely used to analyze network characteristics and structures. A network is a collection of nodes based on a certain relationship, and a social network is a collection of all relationships and their nodes in a society [49]. This paper uses SNA to build CI networks in GI. Through the visual modeling of the connections between nodes in the CI network, CI network data can be displayed graphically, which can not only efficiently understand the macro structure of the network, but also further explore the micro information of the network [49].

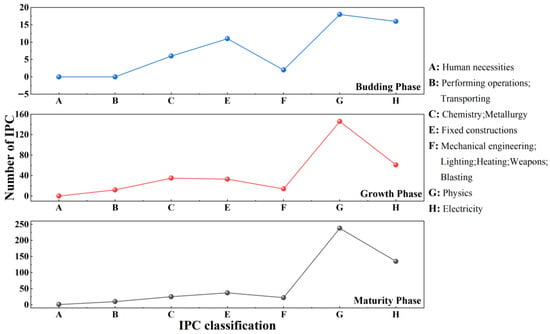

To intuitively demonstrate the evolution trajectories of the network, applications are regarded as nodes, and their collaboration relationships are represented as edges. Consequently, a three-phase CI network in GI is visualized, as shown in Figure 4. In addition, each subject is classified according to the number of patent applications. Subjects with more than 70 patent applications are indicated in red, those with 30 to 70 patents in blue, those with 20 to 30 patents in green, and those with less than 10 patents in purple.

Figure 4.

CI networks in three development phases.

In the budding phase, there were fewer organizations, mainly led by the State Grid Corporation of China. Entering the growth phase, more and more organizations joined. The scale of the network expanded significantly, and the scale of innovation activities and cooperation groups led by the State Grid Corporation continued to expand. At the maturity stage, the network scale continued to expand, showing a rapid development trend. The State Grid Corporation has always occupied a key position, the number of patented inventions at North China Electric Power University has increased significantly, and the diversity of cooperative organizations has further increased.

4.2.2. CI Network Topological Structure in GI

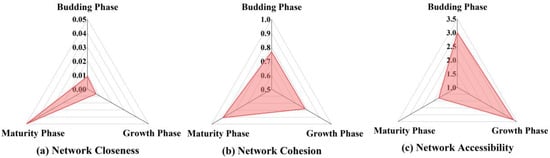

To analyze the topological structure of collaborative innovation networks in GI in three phases, we calculated network density, average clustering coefficient, and average path length.

Network closeness: network density. Network density can reflect the closeness of each node in the network. The higher the network density, the closer the connections between nodes. Network density is calculated as shown in Formula (1):

where and represent the actual number of relationships and nodes in the network, respectively.

Network cohesion: average clustering coefficient. The degree of aggregation of the network can be characterized by the average clustering coefficient, which reflects the degree of aggregation of the network. The higher the average clustering coefficient is, the easier it is for clusters to form between nodes. The formula for the average clustering coefficient is as follows:

where represents the actual number of edges connected between node and its adjacent nodes, and indicates the degree of the node.

Network accessibility: average path length. The average path length reflects the network’s overall efficiency. The smaller the average path length, the better the accessibility of the network. The formula is as follows:

where represents the shortest distance between node and node .

The results of the CI networks’ topology in GI are shown in Figure 4. The network density has shown a downward trend, and the closeness between nodes is less. This reduces the speed of transmission of innovative resources and the efficiency of collaboration, forming an island effect. The average clustering coefficient and average path length of the CI network show a trend of change in the opposite direction (Figure 5b,c), and there is a large difference between them, indicating that the network has a typical small-world characteristic. The average clustering coefficient decreased first and then increased, indicating that the network gradually gathered and its stability was enhanced. The average path length as a whole is between 1.781 and 3.366, which is equivalent to connecting any subject through less than 4 intermediate subjects, in line with the “six degrees of separation theory” [50], and showing a steady trend of improvement.

Figure 5.

Topological structure in three development phases.

4.2.3. CI Network Stakeholders Role Identification in GI

Node characteristics in the network are often characterized by centrality, which can identify their importance and influence [51]. Therefore, we identify stakeholders who play key roles in the CI networks in GI through the degree centrality, closeness centrality, and betweenness centrality [52].

Core innovator: degree centrality. The core role of nodes in the network can be reflected through their degree centrality. The higher the centrality of a node is, the more core it is in the network.

Innovation dominator: betweenness centrality. The betweenness centrality indicates the mediation ability of nodes in the network; that is, the innovation connections among other nodes must be established through this node, reflecting the dominant role of nodes in CI.

Central actor: closeness centrality. The driving role of nodes on a network is characterized by close centrality. The higher the closeness centrality, the more it means that the innovation subject can quickly cooperate with other subjects and play the role of a central actor in the network.

The stakeholders who play a key role in the CI networks in GI (the top three) are shown in Table 2a–c. In the budding phase (Table 2a), the “State Grid Corporation of China” and provincial power companies have a high core, intermediary, and leadership role in the network, and play the role of core innovators, innovation dominators, and central actors. At the same time, as a bridge of knowledge, information and other resources flow; “China Electric Power Research Institute” plays the role of innovation dominator in the procress of CI.

Table 2.

(a) Important nodes of CI network in the Budding phase. (b) Important nodes of CI network in the Growth phase. (c) Important nodes of CI network in the Maturity phase.

In the growth phase (Table 2b), the “State Grid Corporation of China” and provincial power companies also play the role of core innovators, innovation dominators, and central actors, and their influence is significantly increased. “China Electric Power Research Institute” plays a more significant intermediary role in the process of CI, indicating that it can quickly acquire and transfer various resources to facilitate the smooth completion of technological innovation.

In the maturity phase (Table 2c), the “State Grid Corporation of China” continues to maintain its core, intermediary, and leading role. The importance of universities and research institutions has gradually emerged, among which “North China Electric Power University”, because of its rich resources, has become the intermediary and bridge of technological innovation and information exchange, and plays the role of innovation dominator and central actor in CI, promoting technological innovation.

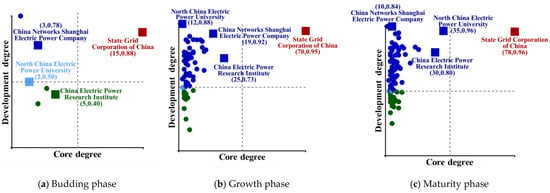

4.2.4. CI Networks Innovation Regions Evolution in GI

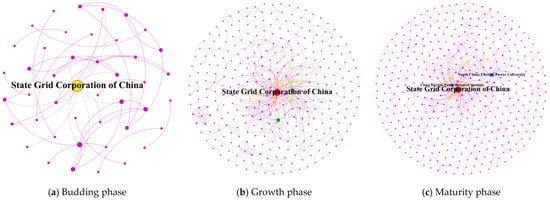

This study analyzes the regions where each organization is located in the process of CI in GI, as shown in Figure 6. Degree centrality is used to represent the core degree of the organizations, and structural holes are used to represent the development degree of the organizations [53]. Two vertical gray dashed lines represent the average values for degree centrality and structural hole.

Figure 6.

Three-phase innovation regions evolution.

In addition, organizations situated in the upper-right area are marked by their high degree centrality and structural hole, signifying an “Innovation driven region”. The organizations in this area are highlighted in red. “Emerging innovation region” has greater degree centrality and a lower structural hole, denoting stakeholders that have strong development potential and may show future trends. Organizations located in this zone are highlighted in blue. “Transparent innovation region” is situated in the third quadrant that has a lower structural hole and degree centrality. Organizations in this area are highlighted in green. The last quadrant is the “Basic innovation region”, which is situated in the bottom right corner, that has greater degree centrality and a lower structural hole. Meanwhile, in this study, representative organizations are highlighted with enlarged squares.

The State Grid Corporation of China has always been located in the “Innovation driven innovation region”, playing the role of the core innovator, central actor, and innovation dominator, and driving the innovation process and guiding stakeholders to the innovation goal. Its high degree centrality ensures widespread connectivity and efficient access to shared resources to accelerate innovation; the high structural hole gives it the ability to see market and technology trends, provide strategic insights, and control resource allocation to ensure the precise flow of innovation resources.

China Electric Power Research Institute (CEPRI) and North China Electric Power University (NCEPU) are located in the “Transparent innovation region” in the budding phase, and move to the “Emerging innovation region” in the growth phase, gradually moving to the upper right. This change is due to their continuous technological innovation and breakthroughs in the field of GI. CEPRI has made important achievements in power system analysis and smart grid technology, while NCEPU has continued to deepen research in the field of new energy technology and power engineering. These innovations have boosted their industry presence and placed them in a better position in the network. CEPRI becomes the core innovator and central actor, while NCEPU acts as the central actor, which allows them to better collaborate and share resources with other stakeholders.

State Grid Shanghai Electric Power Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) has always been located in the “Emerging innovation region”, but its development has slowed down in the maturity phase and its importance has declined. This is mainly reflected in its movement from the core position of the network to the periphery, and from the innovation dominator to the ordinary stakeholder. In the budding phase, State Grid Shanghai Electric Power Co., Ltd., with its strong technical strength and innovation strategy, became a core subject in the network, cooperating with other stakeholders and becoming a bridge for resource allocation. However, with the maturity of technology and the intensification of market competition, it faces a slowdown of technological innovation and the pressure of market share competition in the maturity phase, which leads to the decrease in its importance in the network.

4.3. Driving Factors of CI in GI

4.3.1. ERGM Construction

The Exponential Random Graph Model (ERGM) is a principled statistical model for analyzing social networks that describes complex network structures by capturing the interdependence among nodes and network topology [54,55]. At the same time, due to the interaction between the connecting edges of the CI network, the network structure outside the edge will be innovated on in the process of CI, which then exerts a structural effect to drive CI. This means the network evolution results observed are not all caused by the exogenous variables considered. Therefore, the gravity model and negative binomial regression are not applicable [52]. In addition, ERGM takes into account network self-organizing effects and exogenous network effects and through a general exponential form similar to logistic regression to observed network structures [55,56]. Therefore, we use ERGM to analyze the driving factors in CI networks. There are many variables in ERGM; we select multidimensional proximity as the variable to establish the model.

where is the normalization coefficient , and is the coefficient corresponding to different types of statistics. indicates the network endogenous structural effect, and indicates multidimensional proximity.

4.3.2. ERGM Regression Analysis

Utilizing the Statnet software package, which is implemented in R4.0, we applied the Exponential Random Graph Model (ERGM) and employed Markov Chain Monte Carlo Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MCMC MLE) to estimate the model parameters across each of the three distinct phases.

The detailed results of these estimations are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Three-phase parameter estimation results.

In Table 3, the dynamic effects of edges on CI were analyzed in Model 1. On the whole, the variable of edges has a significant negative effect in the process of CI. In addition, we added multidimensional proximity to the basis of Model 1 for the investigation. Due to the lack of cooperation history before 2010, SP is not considered in the budding phase. In Model 2, TP, GP, and SP have significant promoting effects on CI. However, the influence of OP on the development of GI shows volatility.

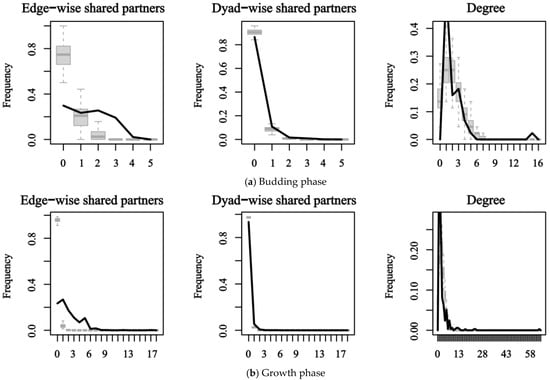

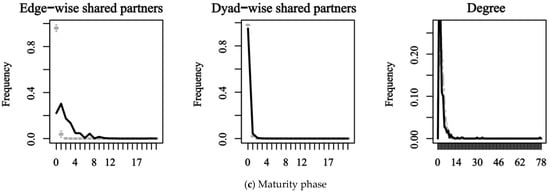

4.3.3. ERGM Goodness of Fit Test

Following parameter estimation, it is essential to assess the validity of the obtained results by conducting a goodness-of-fit evaluation. In this study, three representative statistics—Edge-wise, Dyad-wise, and Degree distribution—were selected to diagnose the model’s fitting performance. The goodness-of-fit plots for the three phases are summarized in Figure 7. The solid black line represents the distribution of network statistics derived from the observed network, while the gray area denotes the corresponding confidence interval from the fitted network. As illustrated in Figure 6, the black line falls within the confidence interval of the fitted network, indicating that our model exhibits relatively strong robustness.

Figure 7.

Goodness of fit diagnostics.

5. Discussion

This paper uses SNA to analyze the temporal evolution paths and microscopic characteristics of collaborative innovation in GI. Based on this, the ERGM is introduced to determine the driving effect of multidimensional proximity on collaborative innovation in GI. The rapid development of GI relies on technological innovation, necessitating collaboration among stakeholders [8]. For the temporal evolution of collaborative innovation in GI, State Grid Corporation of China occupies the core position. Meanwhile, the scale of collaborative innovation networks in GI continues to expand, while network closeness decreases. Innovation groups show clustering, causing island effects. Secondly, smart-world characteristics become apparent, and innovation subjects tend to collaborate with closely connected innovation groups to facilitate the rapid transmission of resources and information.

Regarding the microscopic characteristics of collaborative innovation networks in GI, the State Grid Corporation of China plays the role of core innovator, innovation dominator, and central actor, and has always been located in the “Innovation driven region”. Therefore, the State Grid Corporation of China should continue to play an important role in GI in the future. China Electric Power Research Institute and North China Electric Power University have moved from the “Transparent innovation region” to the “Emerging innovation region”, and have the phenomenon of moving to the “Innovation driven region”. Although the Chinese network Shanghai Electric Power Company has always been located in the “Emerging innovation region”, the importance of it in collaborative innovation has decreased with the maturity of technology and the saturation of the market.

Furthermore, we reveal the driving factors of collaborative innovation in GI through the ERGM. Most studies have confirmed that the development of collaborative innovation in GI is influenced by multidimensional proximity [9]. The findings of this paper reveal that geographical, social, and technological proximity promotes collaborative innovation relationships. Specifically, the impact of geographical proximity decreases, which contradicts the results reported by Ding and Tang [11]. Due to the development of technology, the communication methods among stakeholders are more diversified, breaking the limitation of geographical distance. However, for traditional infrastructure with large investment and long construction periods (such as bridges and railways), geographical proximity may still maintain a strong impact by reducing logistics and coordination costs. The influence of organizational proximity shows a fluctuating characteristic, but on the whole, it is still negatively insignificant. In addition, we prove social proximity becomes important [57]. Cooperation is more likely to occur between stakeholders who are already familiar with each other [31]. For regions with fragmented systems or political instability, organizational proximity is of greater significance for CI in GI. Meanwhile, aligning with Gao and Yu [58], technological proximity diminishes over time. Technological similarities among stakeholders can accelerate industry development in the early stages. Conversely, excessive proximity is detrimental to innovation.

This research has certain limitations that point to future research avenues. This research relies on collaborative patent data from China. Although this provides a focused research context, it may limit the universality of research conclusions to other institutional or geographical contexts. Future work can incorporate data from other regions for comparative analysis. Furthermore, while ERGM is powerful for cross-sectional analysis, it does not inherently account for time dependence. Consequently, future research could employ the temporal exponential random graph model (TERGM) to better explore the evolutionary mechanisms of CI in GI over time.

6. Conclusions

The primary objective of this study is to shed light on the underlying mechanisms of CI in GI. We first developed the CI networks in GI using longitudinal patent data from 2010 to 2024 and analyzed the near-characteristics of the CI networks through the SNA method. Secondly, we not only explored the role and functions played by the organization in CI networks, but also analyzed the innovation area in which the organization is located. Finally, we employed the ERGM to further reveal the dynamic effects of multidimensional proximity on CI in GI.

Our findings reveal several key insights. First, the density of collaborative innovation networks in GI decreased from 0.153 to 0.033, and the average path length remained within 3.4, presenting typical small-world characteristics, which is conducive to the rapid transmission of resources and information. However, the expansion of the network scale is accompanied by a decrease in network density, leading to the formation of clustered innovation groups and resulting in “island effects.” Third, multidimensional proximity is a significant determinant to CI in GI. Specifically, the positive driving effect of social proximity is the most significant, while the coefficient of geographical proximity has decreased from 2.83 in the budding stage to 0.003 in the mature stage. Similarly, the coefficient of technical proximity decreased from 2.528 to 1.735, indicating that its driving effect gradually weakened.

This study offers significant implications for both theory and practice. Theoretically, it provides a dynamic perspective for understanding complex CI relationships and enriches the theoretical study of network evolution in the context of GI. It also offers a more comprehensive explanation by integrating the ERGM framework to elucidate how multidimensional proximity dynamically shapes cooperative innovation. Practically, the findings suggest that the effective allocation of resources and talent training within organizations are crucial for fostering innovation performance. The corresponding recommendations, such as leveraging social ties and managing technological portfolios, are proposed for relevant practitioners to achieve technological innovation and advance green low-carbon goals in infrastructure development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Z. and X.L.; methodology, R.Z.; software, X.L.; validation, X.L.; formal analysis, R.Z.; investigation, R.Z. and X.L.; data curation, X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, R.Z.; visualization, X.L.; supervision, R.Z.; project administration, R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (NO. 24YJC630298), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (NO. 71801119), and the Basic Research Project of the Education Department of Liaoning Province (NO. LJ112510147006).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lu, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, Y. Collaboration networks and bidding competitiveness in megaprojects. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Solangi, Y.A. Assessing impact investing for green infrastructure development in low-carbon transition and sustainable development in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 25257–25280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.; Zanders, J.; Lieberknecht, K.; Fassman-Beck, E. A comprehensive typology for mainstreaming urban green infrastructure. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 2571–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatari, S.; Yu, Z.; Montalto, F.A. Life cycle implications of urban green infrastructure. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 2174–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmann, C.; Brezinski, H.; Erbe, A. Innovation in construction megaprojects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 04016059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, J. A meta-analysis of the relationship between collaborative innovation and innovation performance: The role of formal and informal institutions. Technovation 2023, 124, 102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Nie, P.Y. Analysis of cooperative technological innovation strategy. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraz. 2021, 34, 1520–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauter, R.; Globocnik, D.; Perl-Vorbach, E.; Baumgartner, R.J. Open innovation and its effects on economic and sustainability innovation performance. J. Innov. Knoml. 2019, 4, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutten, M.E.; Dorée, A.G.; Halman, J.I. Innovation and interorganizational cooperation: A synthesis of literature. Construct. Innovat. 2009, 9, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponds, R.; Van Oort, F.; Frenken, K. The geographical and institutional proximity of research collaboration. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2007, 86, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yao, J.; Bi, K. Drifting towards collaborative innovation: Patent collaboration network of China’s nuclear power industry from multidimensional proximity perspective. Prog. Nucl. Energ. 2023, 164, 104851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Collaborative relationship discovery in green building technology innovation: Evidence from patents in China’s construction industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 391, 136041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Tang, Y. Evolution of collaborative relationships in green building technology innovation: A multidimensional proximity perspective. IEEE T. Eng. Manag. 2025, 72, 1454–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, W.; Bi, K. Exploring and visualizing spatial-temporal evolution of patent collaboration networks: A case of China’s intelligent manufacturing equipment industry. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wan, Y.; Gao, Z.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, R. Sustainable network analysis and coordinated development simulation of urban agglomerations from multiple perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 413, 137378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoben, J.; Oerlemans, L.A. Proximity and inter-organizational collaboration: A literature review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2006, 8, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.T.; Ren, L.C.; Zhang, C.; Liang, M.S.; Stasiulis, N.; Streimikis, J. Impacts of Feminist Ethics and Gender on the Implementation of CSR Initiatives. Filos.-Sociol. 2020, 31, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbesgaard, M. Blue growth: Savior or ocean grabbing? J. Peasant. Stud. 2017, 45, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, J. From fail-safe to safe-to-fail: Sustainability and resilience in the new urban world. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2011, 100, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, J.; Zhang, X.J.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Bilan, S. Green infrastructure: Systematic literature review. Econ. Res.-Ekon Istraz. 2021, 35, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, T.B.; Visscher, K.; Volker, L. A systemic perspective on transition barriers to a circular infrastructure sector. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2022, 41, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. What you should know about megaprojects and why: An overview. Proj. Manag. J. 2014, 45, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Fan, D.J.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.L. Impact of innovation organization network on the synergy of cross-organizational technological innovation: Evidence from megaproject practices in China. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2023, 29, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Locatelli, G.; Zhang, X.Y.; Gong, Y.H.; He, Q.H. Firm and project innovation outcome measures in infrastructure megaprojects: An interpretive structural modelling approach. Technovation 2022, 109, 102349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.H.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, G.; Zhu, J.; Yang, D.L.; Liu, X.X.; Li, Y. Managing social responsibility for sustainability in megaprojects: An innovation transitions perspective on success. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Macaulay, S.; Debarro, T.; Thurston, M. Making innovation happen in a megaproject: London’s crossrail suburban railway system. Proj. Manag. J. 2014, 45, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuitert, L.; Volker, L.; Hermans, M.H. Definitely not a walk in the park: Coping with competing values in complex project networks. Proj. Manag. J. 2023, 54, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Zuo, Z.L.; Cheng, J.H.; Xu, D.Y. Evolutionary characteristics and structural dependence determinants of global lithium trade network: An industry chain perspective. Resour. Policy 2024, 99, 105381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.F.; Hu, Q.Y. Knowledge sharing in supply chain networks: Effects of collaborative innovation activities and capability on innovation performance. Technovation 2020, 94, 102010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.Q.; Xie, Y.J. Assessing the potential of collaborative innovation strategies to drive green development: Threshold effect of market competition. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.X.; Xue, X.L.; Zhang, Y.X. The Cascade effect of collaborative innovation in infrastructure project networks. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2021, 27, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, C. Networks of innovators: A synthesis of research issues. Res. Policy 1991, 20, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anne, L.J.; Wal, T. The dynamics of the inventor network in German biotechnology: Geographic proximity versus triadic closure. J. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 4, 589–620. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Location, competition, and economic development: Local clusters in a global economy. Econ. Dev. Q. 2000, 14, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.X.; Wang, Z.Y.; Tang, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.X. Collaborative innovation for sustainable construction: The case of an industrial construction project network. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 41403–41417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.M.; Kang, J.N.; Yu, B.Y.; Liao, H.; Du, Y.F. A dynamic forward-citation full path model for technology monitoring: An empirical study from shale gas industry. Appl. Energy 2017, 205, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Zuo, J. Who drives green innovations? Characteristics and policy implications for green building collaborative innovation networks in China. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2021, 143, 110875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R. Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitze, T.; Strotebeck, F. Determining factors of interregional research collaboration in Germany’s biotech network: Capacity, proximity, policy? Technovation 2019, 80, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Li, Y.; Zhu, K.; Huang, H.; Cai, Z. Who innovates with whom and why? A comparative analysis of the global research networks supporting climate change mitigation. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 88, 102523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Pan, X.; Ai, B.; Guo, S. Structural heterogeneity and proximity mechanism of China’s inter-regional innovation cooperation network. Technol. Anal. Strateg. 2020, 32, 1066–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavitt, K. Patent statistics as indicators of innovative activities: Possibilities and problems. Scientometrics 1985, 7, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.L.; Falagán, N.; Hardman, C.A. Ecosystem service delivery by urban agriculture and green infrastructure—A systematic review. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 54, 101405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Q.; Liu, C.; Du, D. Globalization of science and international scientific collaboration: A network perspective. Geoforum 2019, 105, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montobbio, F.; Sterzi, V. The globalization of technology in emerging markets: A gravity model on the determinants of international patent collaborations. World Dev. 2013, 44, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooteboom, B. Innovation, learning and industrial organisation. Camb. J. Econ. 1999, 23, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeSage, J.P.; Fischer, M.M.; Scherngell, T. Knowledge spillovers across Europe: Evidence from a Poisson spatial interaction model with spatial effects. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2007, 86, 393–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.; Kwon, Y.; Kim, Z. Technology life cycle and commercialization readiness of hydrogen production technology using patent analysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 12139–12154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, G.; Wang, S.; Teng, Q.; Zuo, J.; Tan, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z. The sustainable future of hydropower: A critical analysis of cooling units via the Theory of Inventive Problem Solving and Life Cycle Assessment methods. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2446–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Chen, C.Y.; Lee, S.C. Technology forecasting and patent strategy of hydrogen energy and fuel cell technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 6957–6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakiche, N.; Tayeb, F.B.S.; Slimani, Y.; Benatchba, K. Tracking community evolution in social networks: A survey. Inform. Process. Manag. 2019, 56, 1084–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, G.; Zhu, X.; Dai, J.; Chen, X. Understand technological innovation investment performance: Evolution of industry-university-research cooperation for technological innovation of lithium-ion storage battery in China. J. Energy Storage. 2022, 46, 103607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoylenko, I.; Aleja, D.; Primo, E.; Alfaro-Bittner, K.; Vasilyeva, E.; Kovalenko, K.; Musatov, D.; Raigorodskii, A.M.; Criado, R.; Romance, M.; et al. Why are there six degrees of separation in a social network? Phys. Rev. X 2023, 13, 021032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, T. Analysis on the theory and practice of industrial symbiosis based on bibliometrics and social network analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 956–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1978, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudi, M.; Shokouhyar, S.; Ataei, A.; Ahmadi, S.; Shokoohyar, S. Co-authorship network analysis of AI applications in sustainable supply chains: Key players and themes. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 422, 138472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Niu, C.; Han, J. Spatial dynamics of intercity technology transfer networks in China’s three urban agglomerations: A patent transaction perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yu, X. Factors affecting the evolution of technical cooperation among “belt and road initiative” countries based on TERGMs and ERGMs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).