Aerodynamic Performance of Buildings with Balconies and HAWT Mounted on the Roof

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Wind Turbines and Buildings Models

2.2. Numerical Scheme

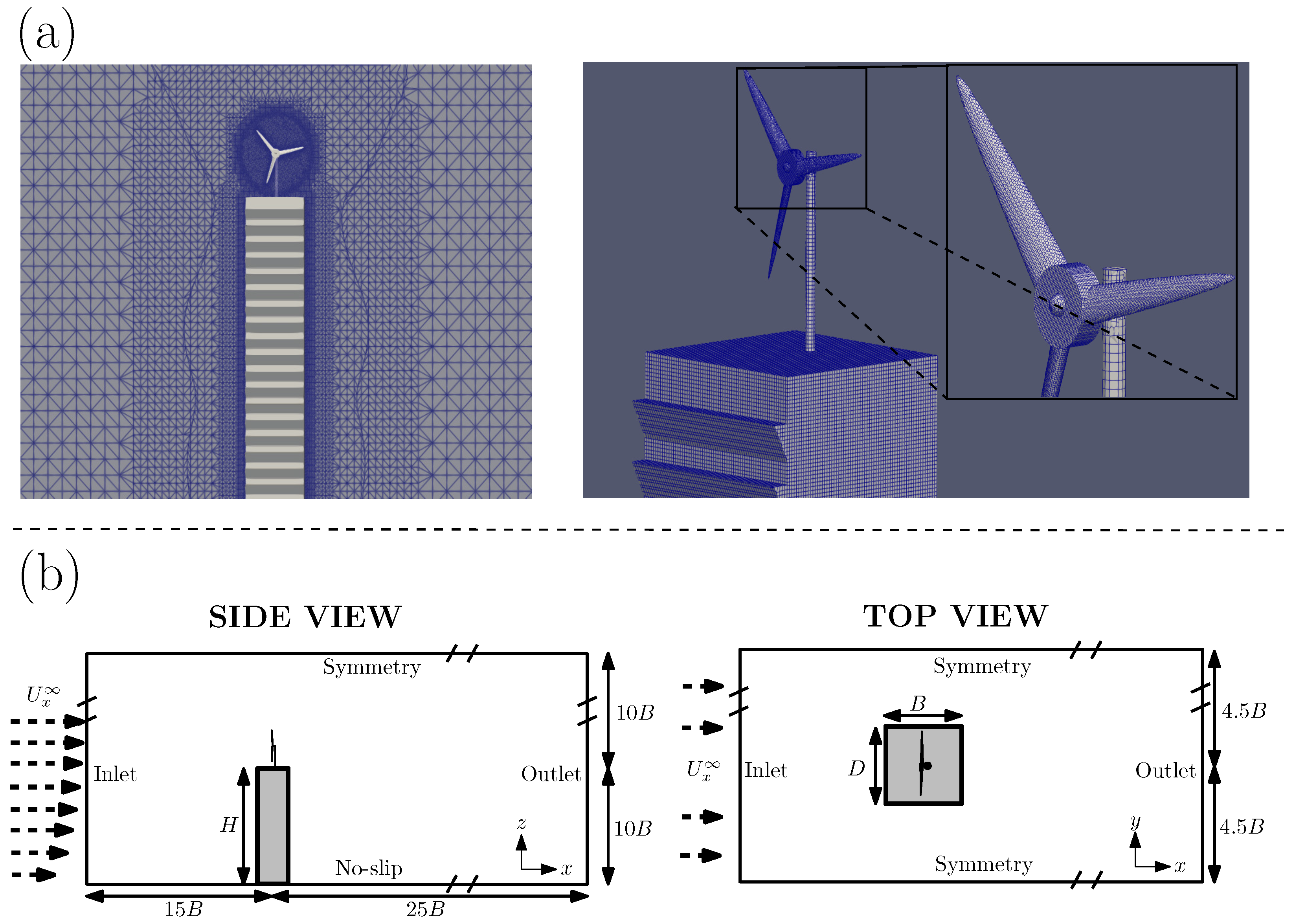

2.3. Meshing Details, Initial and Boundary Conditions

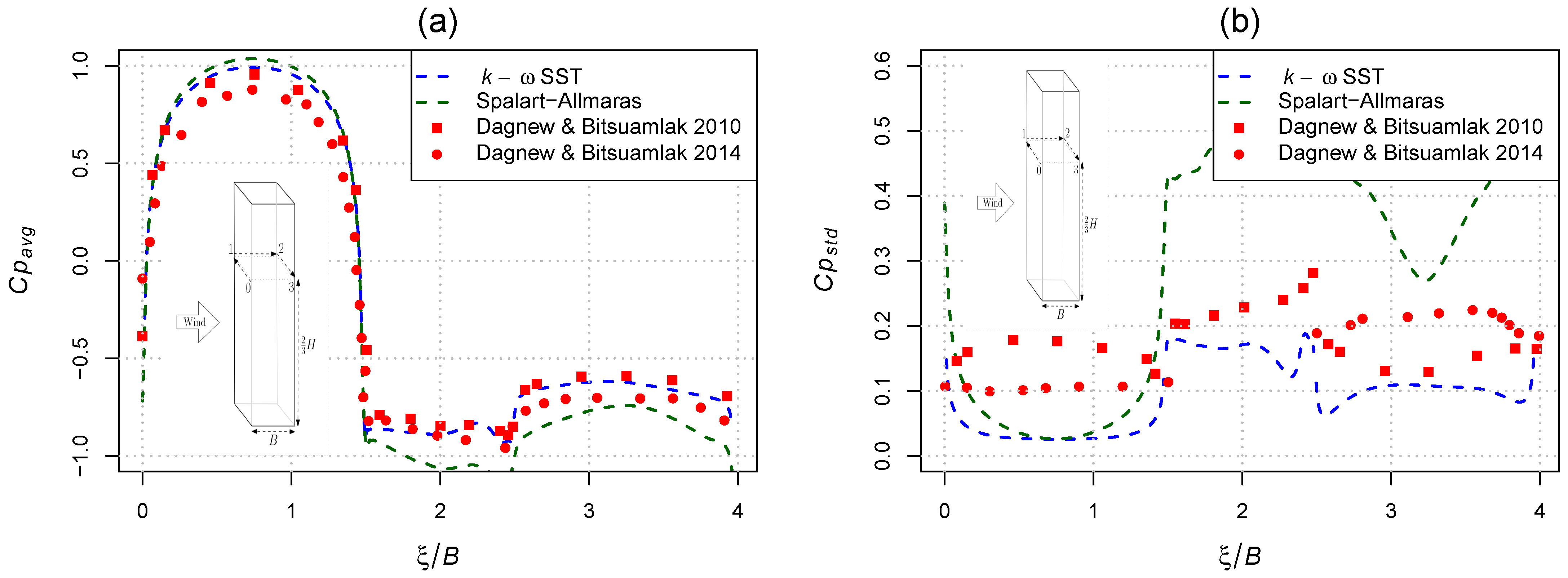

2.4. Model Validation

3. Results

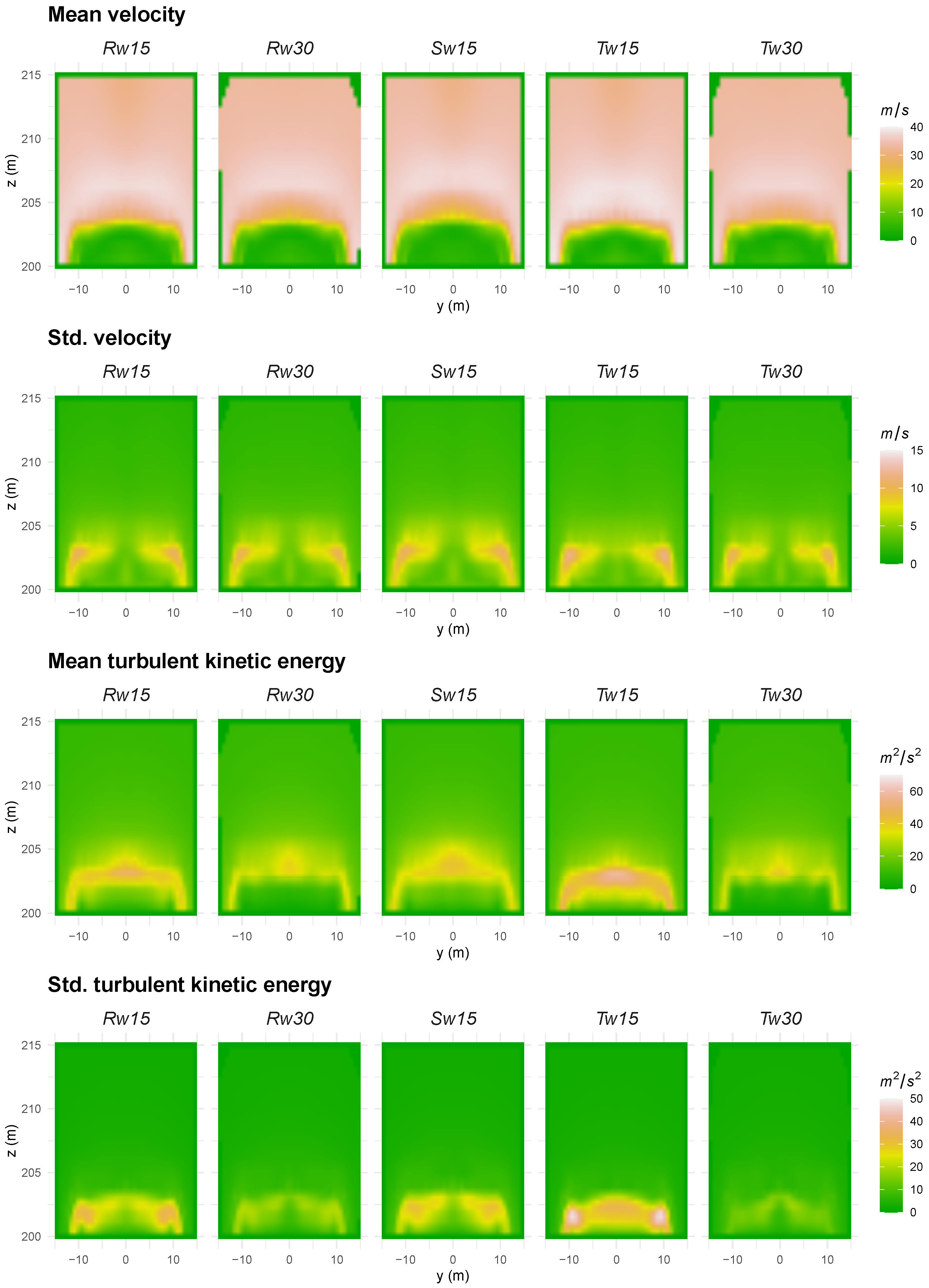

3.1. Inflow at the Turbine

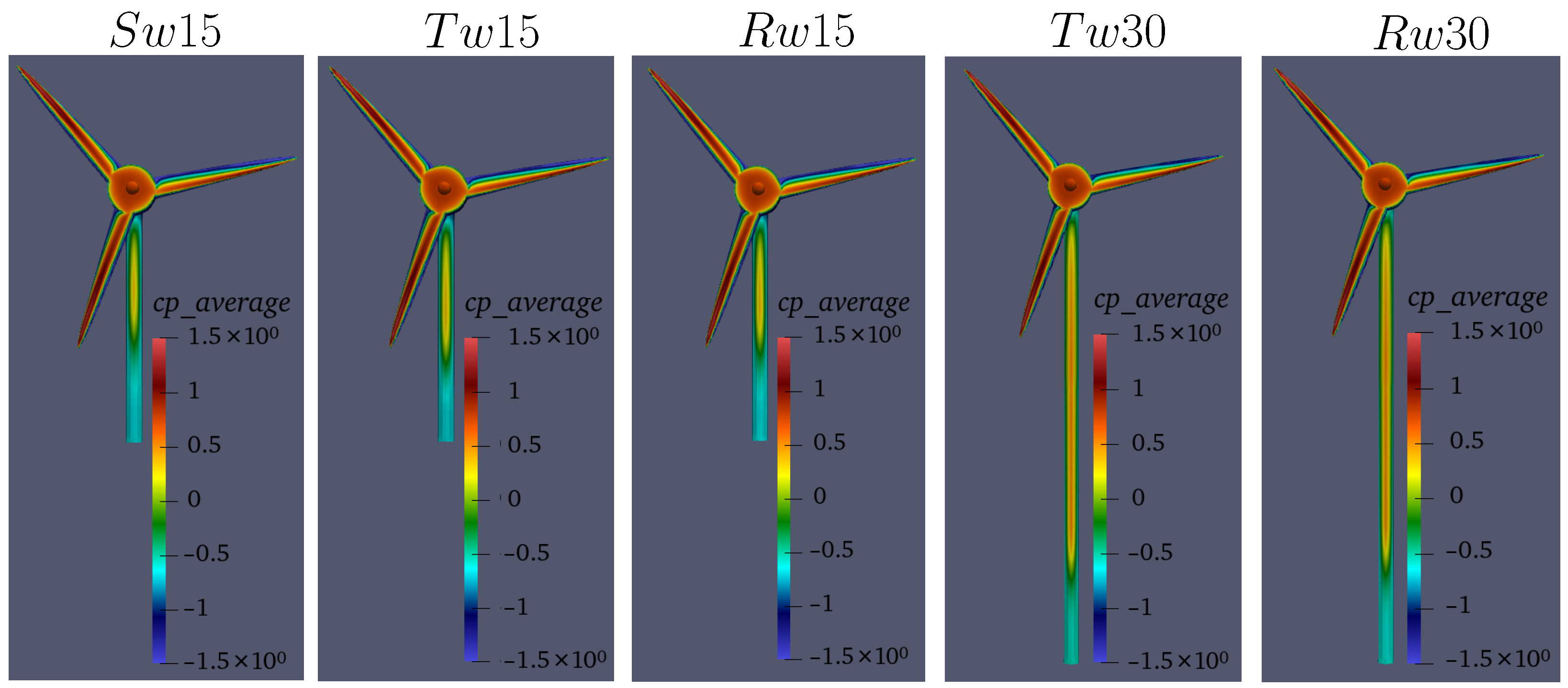

3.2. Pressure and Power Generation on the Turbine

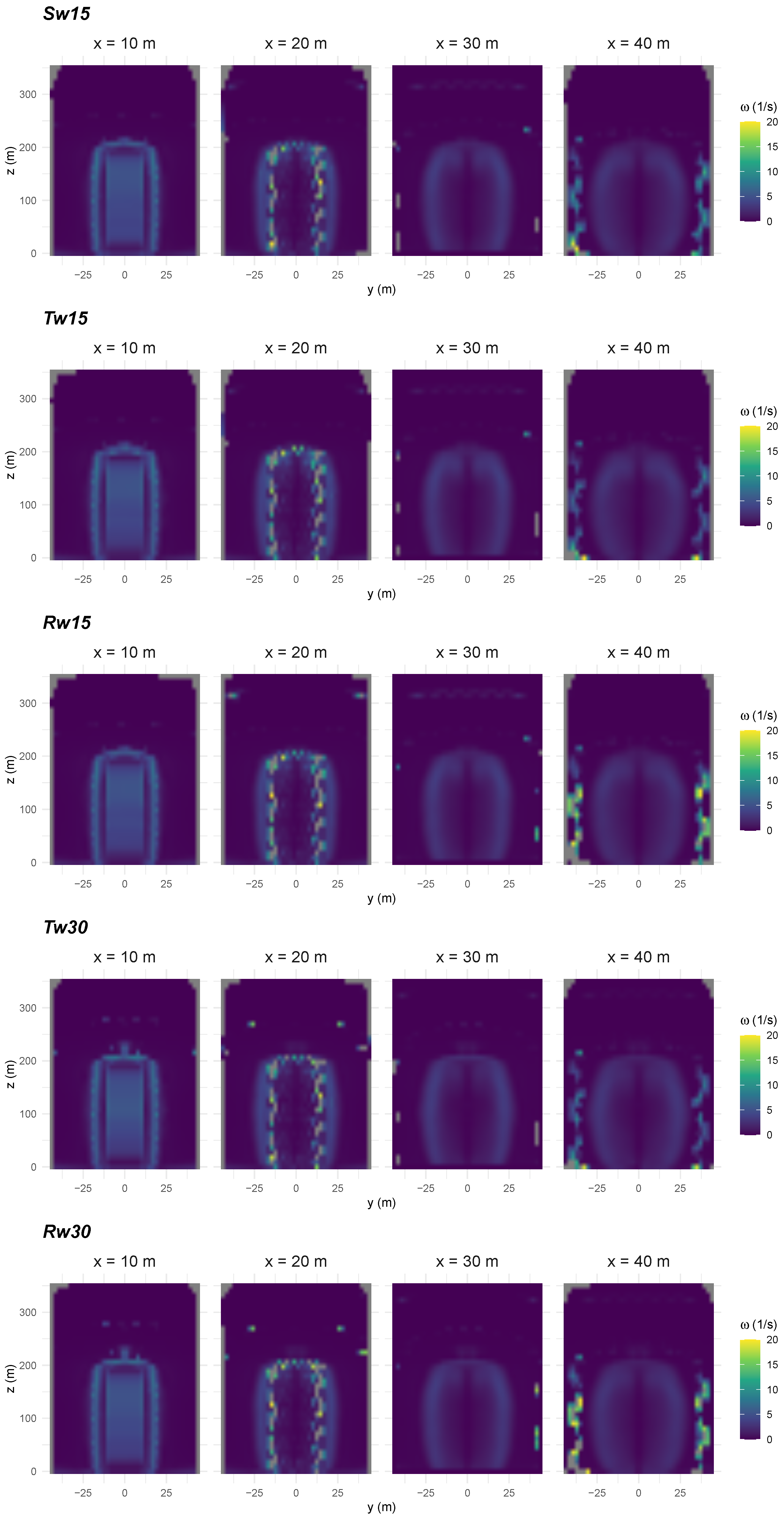

3.3. Wake Effects

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Abbreviations | Description | |

| CAARC | Commonwealth Advisory Aeronautical Research Council | |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics | |

| HAWT | Horizontal-Axis Wind Turbine | |

| LES | Large Eddy Simulation | |

| PIMPLE | Pressure-Implicit with Splitting of Operators + SIMPLE | |

| PISO | Pressure-Implicit with Splitting of Operators | |

| RAS | Reynolds-Averaged Simulations | |

| RMS | Root Mean Square | |

| R-balconies | Rectangular balconies | |

| R15 | Building model with R-balconies, and a HAWT | |

| at 15 m over the roof | ||

| R30 | Building model with R-balconies, and a HAWT | |

| at 30 m over the roof | ||

| SIMPLE | Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure-Linked Equations | |

| SST | Shear Stress Transport | |

| SWTs | Small Wind turbines | |

| S15 | Building model without balconies, and a HAWT | |

| at 15 m over the roof | ||

| TSR | Tip-Speed Ratio | |

| T-balconies | Triangular balconies | |

| T15 | Building model with T-balconies, and a HAWT | |

| at 15 m over the roof | ||

| T30 | Building model with T-balconies, and a HAWT | |

| at 30 m over the roof | ||

| VAWTs | Vertical-Axis Wind Turbines | |

| WTs | Wind Turbines | |

| Symbol | Description | Units |

| B | Width of the building | [m] |

| D | Depth of the building | [m] |

| H | Height of the building | [m] |

| w | Height to the turbine axis from the roof | [m] |

| k | Turbulent kinetic energy | [m2/s2] |

| Specific turbulent dissipation rate | [1/s] | |

| Dissipation rate of turbulent kinetic energy | [m2/s3] | |

| Stream-wise velocity at the inlet | [m/s] | |

| at height | [m/s] | |

| at the turbine | [m/s] | |

| Fluid density | [kg/m−3] | |

| Friction velocity | [m/s] | |

| Empirical model constant | (Dimensionless) | |

| Curve fitting coefficients | (Dimensionless) | |

| von Kármán constant | (Dimensionless) | |

| Length of aerodynamic roughness | [m] | |

| d | Height of the normal ground displacement | [m] |

| Reference height | [m] | |

| Stream-wise velocity at | [m/s] | |

| Reynolds number at | (Dimensionless) | |

| Auxiliary variable of distance | [m] | |

| Free-stream pressure | [Pa] | |

| p | Local pressure | [Pa] |

| Relative-pressure coefficient | (Dimensionless) | |

| l | Length of the blades | [m] |

| coordinates | [m] | |

| Angular velocity | [rpm] | |

| Power coefficient | (Dimensionless) | |

| U | Velocity | [m/s] |

| Power available | [kW] | |

| Power generated | [kW] | |

| T | Averaged thrust | [N] |

| Effective torque | [N m] | |

| Effective blade length | [m] | |

| Tangential ratio to the main-stream | (Dimensionless) | |

| Coefficient of an effective level arm | (Dimensionless) |

References

- Davenport, A.G. Gust Loading Factors. J. Struct. Div. 1967, 93, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Kareem, A. Gust Loading Factor: New Model. J. Struct. Eng. 2001, 127, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccardo, G.; Solari, G. 3D Wind-Excited Response of Slender Structures: Closed-Form Solution. J. Struct. Eng. 2000, 126, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. Effective static load distributions in wind engineering. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2002, 90, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kareem, A. Equivalent Static Wind Loads on Buildings: New Model. J. Struct. Eng. 2004, 130, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patruno, L.; Ricci, M.; de Miranda, S.; Ubertini, F. Equivalent Static Wind Loads: Recent developments and analysis of a suspended roof. Eng. Struct. 2017, 148, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathopoulos, T.; Baniotopoulos, C. Wind Effects on Buildings and Design of Wind-Sensitive Structures; CISM International Centre for Mechanical Sciences; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Baniotopoulos, C.; Borri, C.; Stathopoulos, T. Environmental Wind Engineering and Design of Wind Energy Structures; CISM International Centre for Mechanical Sciences; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Simões, T.; Estanqueiro, A. A new methodology for urban wind resource assessment. Renew. Energy 2016, 89, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RenSMART. The NOABL Model. 2025. Available online: https://rensmart.com/Information/NOABLModel (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Drew, D.; Barlow, J.; Cockerill, T. Estimating the potential yield of small wind turbines in urban areas: A case study for Greater London, UK. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2013, 115, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škvorc, P.; Kozmar, H. Wind energy harnessing on tall buildings in urban environments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, S.; Moro, A.; Reis, V.; Baniotopoulos, C.; Barth, S.; Bartoli, G.; Bauer, F.; Boelman, E.; Bosse, D.; Cherubini, A.; et al. Future emerging technologies in the wind power sector: A European perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 113, 109270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishugah, T.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Kiplagat, J. Advances in wind energy resource exploitation in urban environment: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 37, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, G.; Šarkić Glumac, A.; Hemida, H.; Salvadori, S.; Baniotopoulos, C. On the Wind Energy Resource above High-Rise Buildings. Energies 2020, 13, 3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, J.L.; Combe, K.; Djokic, S.Z.; Hernando-Gil, I. Performance Assessment of Micro and Small-Scale Wind Turbines in Urban Areas. IEEE Syst. J. 2012, 6, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, H.; Montazeri, F. CFD simulation of cross-ventilation in buildings using rooftop wind-catchers: Impact of outlet openings. Renew. Energy 2018, 118, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroozesh, J.; Hosseini, S.; Ahmadian Hosseini, A.; Parvaz, F.; Elsayed, K.; Uygur Babaoğlu, N.; Hooman, K.; Ahmadi, G. CFD modeling of the building integrated with a novel design of a one-sided wind-catcher with water spray: Focus on thermal comfort. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 53, 102736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorani, M.M.; Karimi, B.; Mirghavami, S.M.; Saboohi, Z. A numerical study on the feasibility of electricity production using an optimized wind delivery system (Invelox) integrated with a Horizontal axis wind turbine (HAWT). Energy 2023, 268, 126643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathopoulos, T.; Alrawashdeh, H.; Al-Quraan, A.; Blocken, B.; Dilimulati, A.; Paraschivoiu, M.; Pilay, P. Urban wind energy: Some views on potential and challenges. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2018, 179, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkantou, M.; Rebelo, C.; Baniotopoulos, C. Life Cycle Assessment of Tall Onshore Hybrid Steel Wind Turbine Towers. Energies 2020, 13, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, S. Wind energy in urban areas: Concentrator effects for wind turbines lose to buildings. Refocus 2002, 3, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tablada, A.; Kosorić, V. 11—Vertical farming on facades: Transforming building skins for urban food security. In Rethinking Building Skins; Gasparri, E., Brambilla, A., Lobaccaro, G., Goia, F., Andaloro, A., Sangiorgio, A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Civil and Structural Engineering; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2022; pp. 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahda, M.M.; Megahed, N.A. Post-pandemic architecture: A critical review of the expected feasibility of skyscraper-integrated vertical farming (SIVF). Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2023, 19, 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Martinez-Vazquez, P.; Baniotopoulos, C. Wind Flow Characteristics on a Vertical Farm with Potential Use of Energy Harvesting. Buildings 2024, 14, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Martinez-Vazquez, P.; Baniotopoulos, C. Experimental Measurements of Wind Flow Characteristics on an Ellipsoidal Vertical Farm. Buildings 2024, 14, 3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Raahemifar, K.; Fung, A.S. A critical review of vertical axis wind turbines for urban applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 89, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-López, M.A.; Hueyotl-Zahuantitla, F.; Martínez-Vázquez, P. Passive Control Measures of Wind Flow around Tall Buildings. Buildings 2024, 14, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratasys Inc. Free CAD Designs. Files & 3D Models: The Grabcad Community Library. 2025. Available online: https://grabcad.com/library/small-wind-turbine-blades-1 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- OpenFOAM. OpenCFD Release OpenFOAM v2012; OpenCFD Ltd.: Bracknell, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OpenFOAM: API Guide v2012—The Open Source CFD Toolbox. OpenFOAM: API Guide: kOmegaSST. 2018. Available online: https://www.openfoam.com/documentation/guides/v2012/api/classFoam_1_1RASModels_1_1kOmegaSST.html (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Langley Research Center—Turbulence Modeling Resource. Menter Shear Stress Transport Model. 2024. Available online: https://turbmodels.larc.nasa.gov/sst.html (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- OpenFOAM v2112. pimpleFOAM Solver. 2018. Available online: https://www.openfoam.com/documentation/guides/latest/doc/guide-applications-solvers-incompressible-pimpleFoam.html (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Thordal, M.S.; Bennetsen, J.C.; Koss, H.H.H. Review for practical application of CFD for the determination of wind load on high-rise buildings. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2019, 186, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenFOAM v2112. ATM Boundary Layer. 2018. Available online: https://www.openfoam.com/documentation/guides/latest/doc/guide-bcs-inlet-atm-atmBoundaryLayer.html (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Huang, S.; Li, Q.; Xu, S. Numerical evaluation of wind effects on a tall steel building by CFD. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2007, 63, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalart, P.; Allmaras, S. A one-equation turbulence model for aerodynamic flows. In Proceedings of the 30th Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, NV, USA, 6–9 January 1992; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 1992; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnew, A.K.; Bitsuamlakb, G.T. LES evaluation of wind pressures on a standard tall building with and without a neighboring building. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on Computational Wind Engineering, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 23–27 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dagnew, A.K.; Bitsuamlakb, G.T. Computational evaluation of wind loads on a standard tall building using LES. Wind. Struct. 2014, 18, 567–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PlotDigitizer: Version 3.1.6. 2025. Available online: https://plotdigitizer.com (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Knopper, L.D.; Ollson, C.A.; McCallum, L.C.; Whitfield Aslund, M.L.; Berger, R.G.; Souweine, K.; McDaniel, M. Wind Turbines and Human Health. Front. Public Health 2014, 2, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuglseth, G. Mythbusting: “Wind Power Is Unreliable, Inefficient and Harmful to Nature”. 2024. Available online: https://www.statkraft.com/newsroom/explained/mythbusting-wind-power-is-unreliable-inefficient-and-harmful-to-nature/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Burton, T.; Jenkins, N.; Sharpe, D.; Bossanyi, E. Aerodynamics of Horizontal Axis Wind Turbines. In Wind Energy Handbook; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; Chapter 3; pp. 39–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, J.; Li, Y.; Buccolieri, R.; Sandberg, M.; Di Sabatino, S. On the contribution of mean flow and turbulence to city breathability: The case of long streets with tall buildings. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 416, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| 20 m/s | |

| 10 m | |

| 0.4 (dimensionless) | |

| 0.03 m | |

| d | 0.03 m |

| 0.01 (dimensionless) | |

| −0.05 (dimensionless) | |

| 1 (dimensionless) |

| Model | # Cells |

|---|---|

| S15 | 1,419,330 |

| T15 | 1,489,959 |

| R15 | 1,482,585 |

| T30 | 1,509,883 |

| R30 | 1,502,467 |

| Measures | Inflow | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

| B | 30.80 m | 14.5 m/s | |

| D | 45.72 m | 7 m | |

| H | 183.88 m | 0.4 (dimensionless) | |

| 0.013 m | |||

| d | 0.013 m | ||

| 0.01 (dimensionless) | |||

| −0.05 (dimensionless) | |||

| 1 (dimensionless) | |||

| Case | Std. Values | Max. Values |

|---|---|---|

| 0.75–1.27 | 27–31 | |

| 0.75–1.27 | 27–31 | |

| 0.75–1.26 | 27–31 | |

| 0.75–1.22 | 26–31 | |

| 0.75–1.27 | 27–31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aguirre-López, M.A.; Hueyotl-Zahuantitla, F.; Martinez-Vazquez, P.; Baniotopoulos, C.; Díaz-Hernández, O. Aerodynamic Performance of Buildings with Balconies and HAWT Mounted on the Roof. Buildings 2025, 15, 4325. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234325

Aguirre-López MA, Hueyotl-Zahuantitla F, Martinez-Vazquez P, Baniotopoulos C, Díaz-Hernández O. Aerodynamic Performance of Buildings with Balconies and HAWT Mounted on the Roof. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4325. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234325

Chicago/Turabian StyleAguirre-López, Mario A., Filiberto Hueyotl-Zahuantitla, Pedro Martinez-Vazquez, Charalampos Baniotopoulos, and Orlando Díaz-Hernández. 2025. "Aerodynamic Performance of Buildings with Balconies and HAWT Mounted on the Roof" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4325. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234325

APA StyleAguirre-López, M. A., Hueyotl-Zahuantitla, F., Martinez-Vazquez, P., Baniotopoulos, C., & Díaz-Hernández, O. (2025). Aerodynamic Performance of Buildings with Balconies and HAWT Mounted on the Roof. Buildings, 15(23), 4325. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234325