CracksGPT: Exploring the Potential and Limitations of Multimodal AI for Building Crack Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

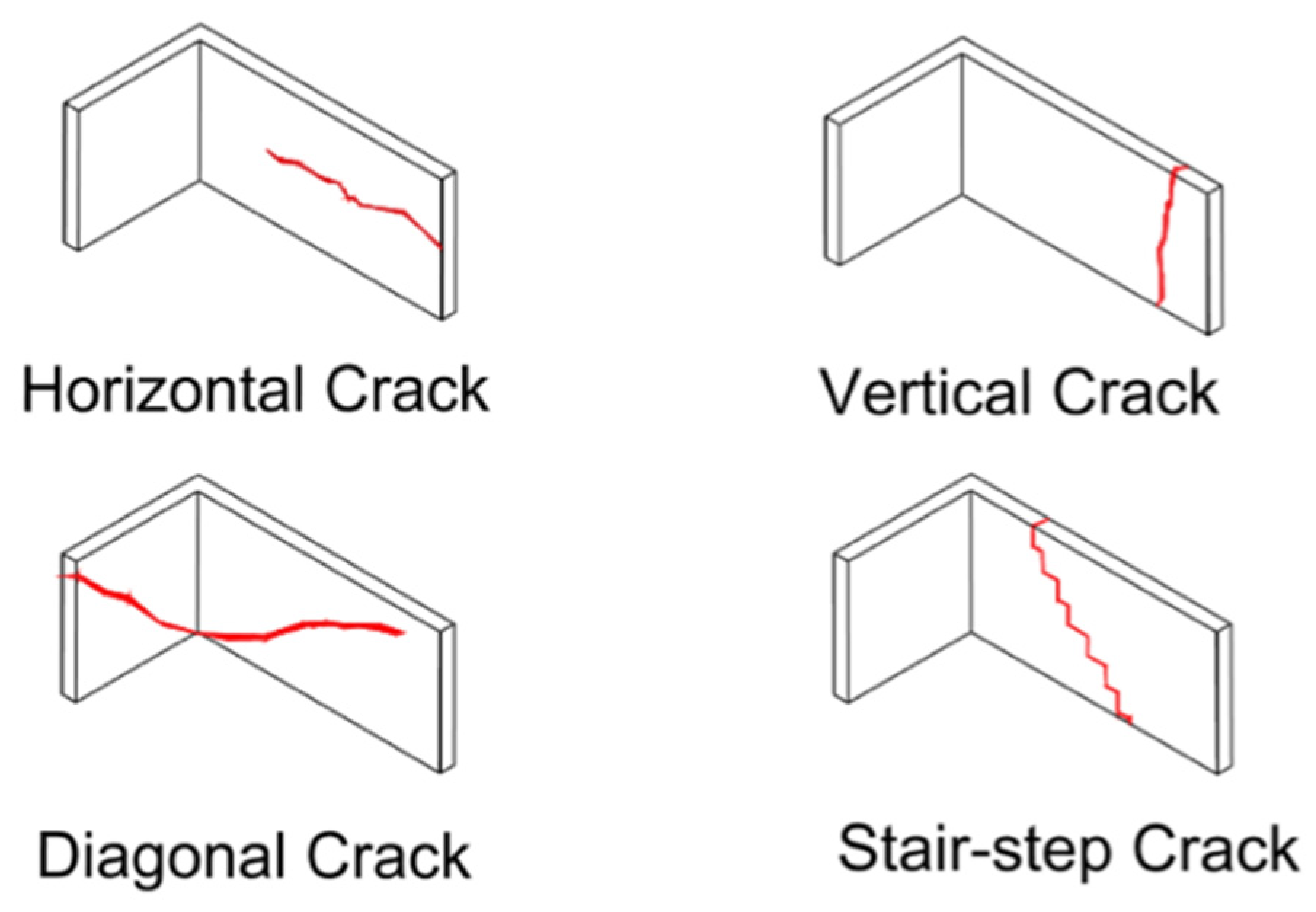

2.1. Building Cracks

2.2. Role of Computer Vision in Image-Based Crack Detection

2.3. Multimodal AI Models and Vision–Language Models

2.4. Research Gaps

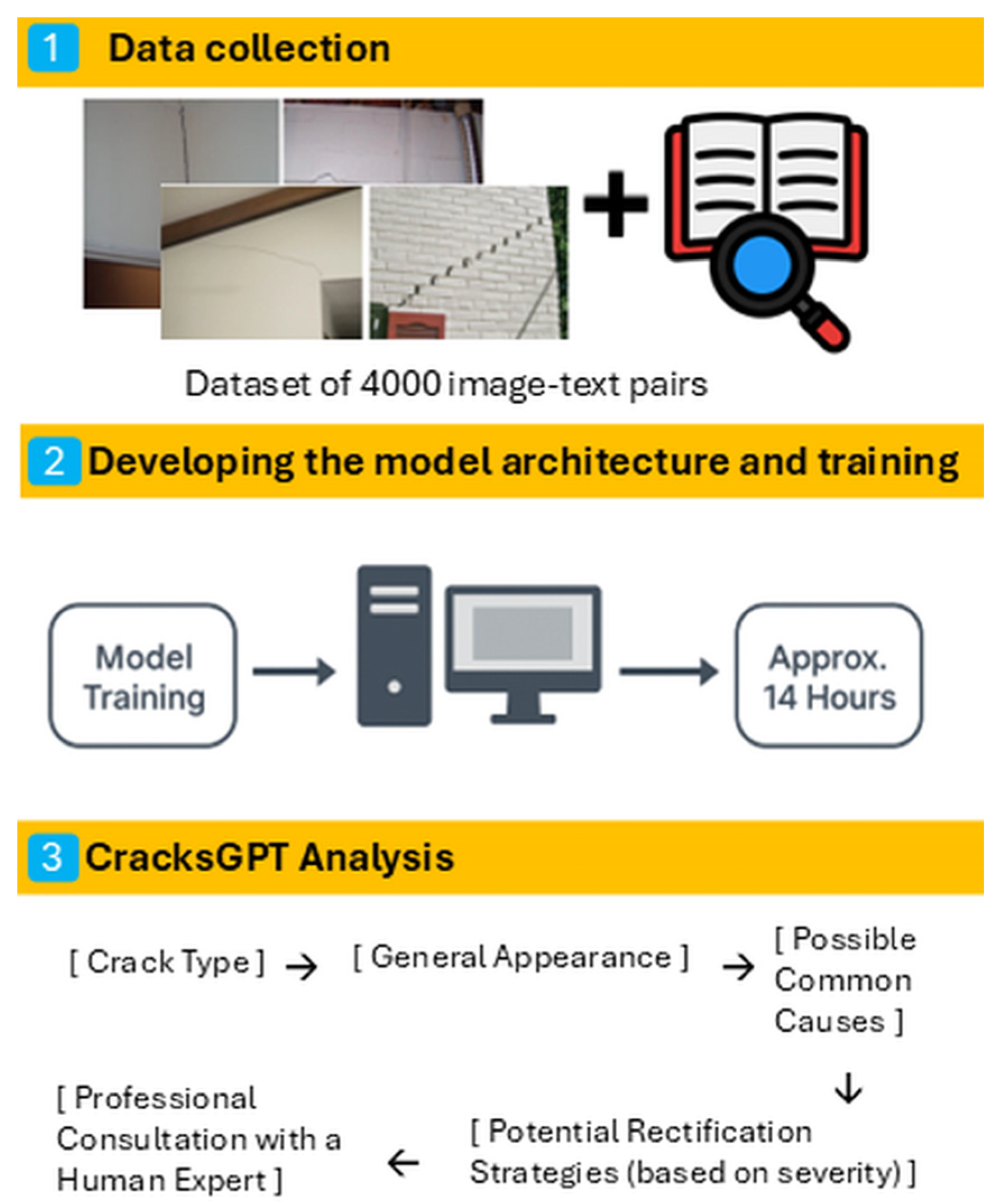

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

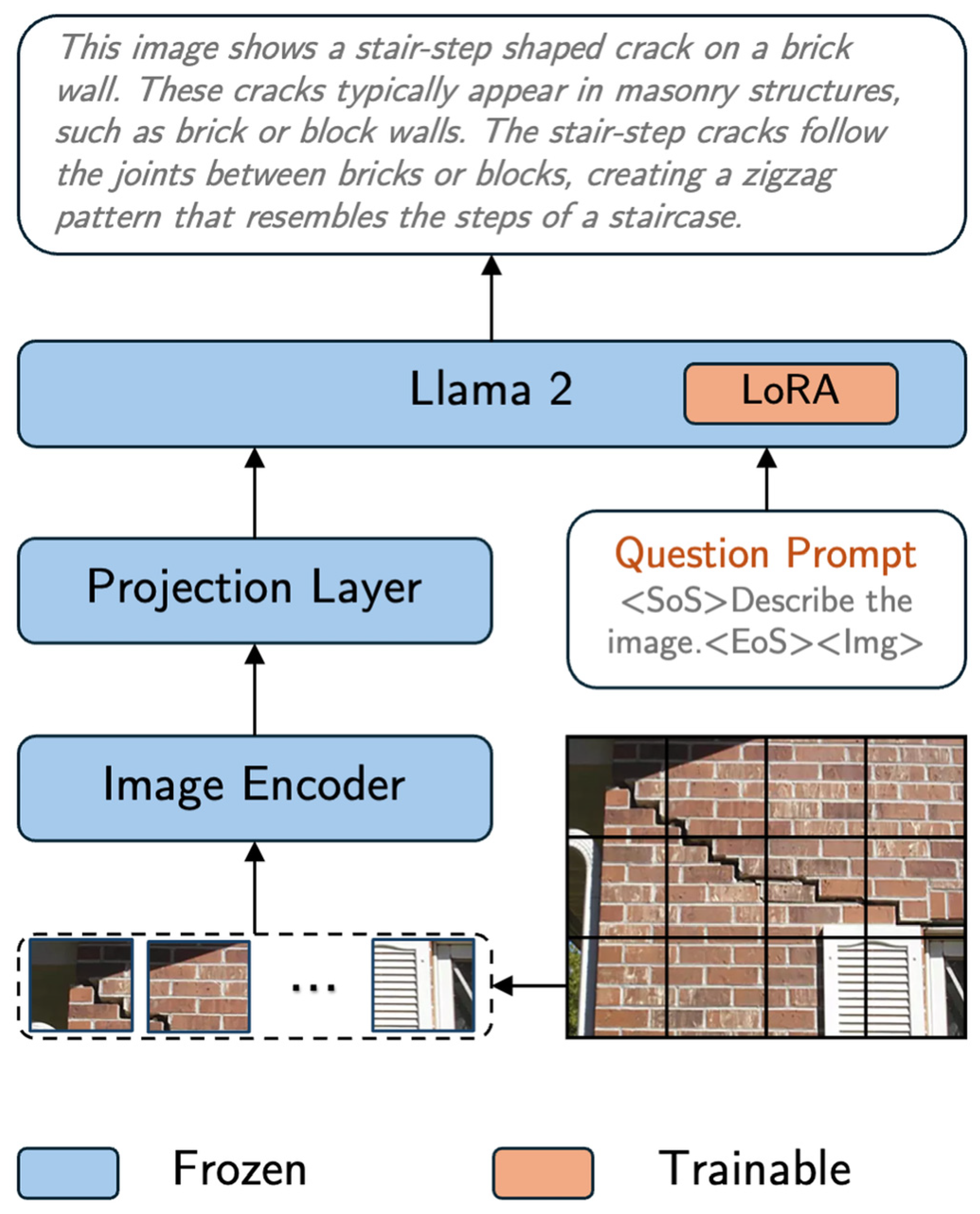

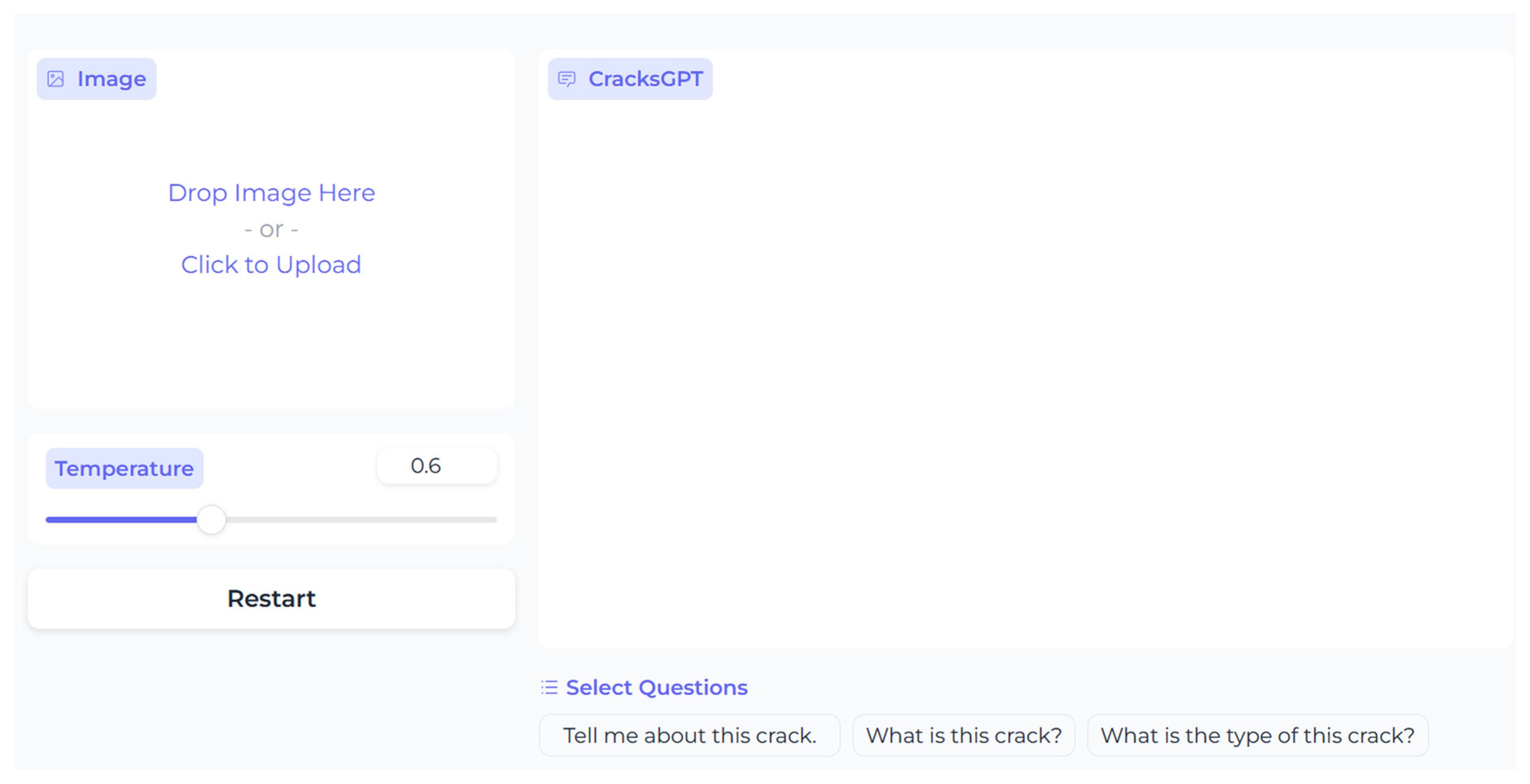

3.2. Model Development and Evaluation

- Type of the crack based on the visual appearance and the appearance and location of the crack in general.

- Potential causes behind the occurrence based on the type of crack.

- Potential solutions and contacting a human expert based on the recommendations

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Internal Trials and Evaluation

4.2. Expert Evaluation Results Analysis

- (1)

- User interface

- (2)

- Detection accuracy

- (3)

- Reasoning and logic

- (4)

- Real-world applicability

4.3. Potential and the Limitations

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, M.; Ma, Z.; Xie, J.; Li, Q. Specific defect detection for efficient building maintenance. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 112, 113710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.; Mishra, S.S. A review of image-based deep learning methods for crack detection. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 35469–35511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Lourenço, P.B.; Ramana, G.V. Structural health monitoring of civil engineering structures by using the internet of things: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 48, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauashdh, A.; Jailani, J.; Abdul Rahman, I.; Al-Fadhali, N. Factors affecting the number of building defects and the approaches to reduce their negative impacts in Malaysian public universities’ buildings. J. Facil. Manag. 2022, 20, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Kwon, N.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Ahn, Y. Probabilistic maintenance cost analysis for aged multi-family housing. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J.; Ransom, B. Understanding Building Failures; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, B. Investigation of self-healing ability of hydroxyapatite blended cement paste modified with graphene oxide and silver nanoparticles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 320, 126250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Allen, R.M.; Kohler, M.D.; Heaton, T.H.; Bunn, J. Structural health monitoring of buildings using smartphone sensors. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2018, 89, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, B. A deep learning-based building defects detection tool for sustainability monitoring. In Proceedings of the 10th World Construction Symposium 2022, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 24–26 June 2022; Ceylon Institute of Builders: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2022; pp. 1–8. Available online: https://ciobwcs.com/downloads/WCS2022_Full_Proceedings.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Kung, R.Y.; Pan, N.H.; Wang, C.C.; Lee, P.C. Application of deep learning and unmanned aerial vehicle on building maintenance. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 8836451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizaji, M.S.; Harris, D.K. 3D InspectionNet: A deep 3D convolutional neural networks-based approach for 3D defect detection on concrete columns. In Proceedings of the Nondestructive Characterization and Monitoring of Advanced Materials, Aerospace, Civil Infrastructure, and Transportation XIII, Denver, CO, USA, 4–7 March 2019; Volume 10971, p. 109710E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, H.S.; Ullah, F.; Heravi, A.; Thaheem, M.J.; Maqsoom, A. Inspecting buildings using drones and computer vision: A machine learning approach to detect cracks and damages. Drones 2022, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cheng, N.; Hu, Y. Comprehensive environmental monitoring system for industrial and mining enterprises using multimodal deep learning and CLIP model. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 19964–19978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuanfan, N.; Piji, L. A systematic evaluation of large language models for natural. In Proceedings of the 22nd Chinese National Conference on Computational Linguistics, Harbin, China, 3–5 August 2023; Volume 2, pp. 40–56. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/2023.ccl-2.4/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Hevner, A.R. A three-cycle view of design science research. Scand. J. Inf. Syst. 2007, 19, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Olurotimi, O.J.; Yetunde, O.H.; Akah, U. Assessment of the determinants of wall cracks in buildings: Investigating the consequences and remedial measures for resilience and sustainable development. Int. J. Adv. Educ. Manag. Sci. Technol. 2023, 6, 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kacker, R.; Singh, S.K.; Kasar, A.A. Understanding and addressing multi-faceted failures in building structures. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2024, 24, 1542–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajagbe, W.O.; Ojedele, O.S. Structural investigation into the causes of cracks in building and solutions: A case study. Am. J. Eng. Res. 2018, 7, 152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. Improvement of the defect inspection process of deteriorated buildings with scan to BIM and image-based automatic defect classification. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 99, 111601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahmalny, T.A.; Evtushenko, S.I. Typical defects and damage to the industrial buildings’ facades. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 775, 012135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Report on Sydney’s Opal Tower Blames Structural Design, Construction Flaws for Cracks. Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Available online: https://www.ctbuh.org/news/report-on-sydneys-opal-tower-blames-structural-design-construction-flaws-for-cracks (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Engineering Institute of Technology. Australia’s Apartment Building Cracks Show Corner-Cutting in Civil Engineering; Engineering Institute of Technology: Lund, Sweden, 2019; Available online: https://www.eit.edu.au/australias-apartment-building-cracks-show-corner-cutting-in-civil-engineering/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- NSW Government. Strata Defects Survey Report—November 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/noindex/2023-12/strata-defects-survey-report.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Abdel-Qader, I.; Abudayyeh, O.; Kelly, M.E. Analysis of edge-detection techniques for crack identification in bridges. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2003, 17, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Yang, H.; Yu, K.; Shu, J. Crack detection and quantification for concrete structures using UAV and transformer. Autom. Constr. 2023, 152, 104929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, E.; Forster, A.; Bosché, F.; Hyslop, E.; Wilson, L.; Turmel, A. Automated defect detection and classification in ashlar masonry walls using machine learning. Autom. Constr. 2019, 106, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, B.F.; Hoskere, V.; Narazaki, Y. Advances in computer vision-based civil infrastructure inspection and monitoring. Engineering 2019, 5, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, S.; Nagarajaiah, S.; Veeraraghavan, A. Vision and deep learning-based algorithms to detect and quantify cracks on concrete surfaces from UAV videos. Sensors 2020, 20, 6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.L.W. Type of Cracks on Buildings. IPM. 24 March 2020. Available online: https://ipm.my/type-of-cracks-on-buildings/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Ai, D.; Jiang, G.; Lam, S.K.; He, P.; Li, C. Computer vision framework for crack detection of civil infrastructure—A review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 117, 105478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, Y. Building surface crack detection using deep learning technology. Buildings 2023, 13, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Chen, K. Autonomous detection and assessment of indoor building defects using multimodal learning and GPT. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2024, Des Moines, IA, USA, 20–23 March 2024; American Society of Civil Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrusaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; Morency, L. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thawakar, O.C.; Shaker, A.M.; Mullappilly, S.S.; Cholakkal, H.; Anwer, R.M.; Khan, S.; Laaksonen, J.; Khan, F.S. XrayGPT: Chest radiographs summarization using large medical vision-language models. In Proceedings of the 23rd Workshop on Biomedical Natural Language Processing, Bangkok, Thailand, 16 August 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 440–448. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/2024.bionlp-1.35/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Xu, P.; Zhu, X.; Clifton, D.A. Multimodal learning with transformers: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 12113–12132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training. 2018. Available online: https://cdn.openai.com/research-covers/language-unsupervised/language_understanding_paper.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, C. Vision-enhanced multi-modal learning framework for non-destructive pavement damage detection. Autom. Constr. 2025, 177, 106389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, D.; Han, M.; Chen, X.; Shi, J.; Xu, S.; Xu, B. VLP: A survey on vision-language pre-training. Mach. Intell. Res. 2023, 20, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Chen, J.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Elhoseiny, M. MiniGPT-4: Enhancing Vision-Language Understanding with Advanced Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.10592. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.10592 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/N19-1423/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Lee, Y.J. Improved baselines with visual instruction tuning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (26296-26306), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Yang, S.; Wang, S.; Tan, S.; Wang, P.; Lin, J.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, J. Qwen-VL: A versatile vision-language model for understanding, localization, text reading, and beyond. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.12966. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, D.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Krishnamoorthi, R.; Chandra, V.; Xiong, Y.; Elhoseiny, M. MiniGPT-v2: Large language model as a unified interface for vision-language multi-task learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.09478. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.09478 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Alsabbagh, A.R.; Mansour, T.; Al-Kharabsheh, M.; Ebdah, A.S.; Al-Emaryeen, R.A.; Al-Nahhas, S.; Al-Kadi, O. MiniMedGPT: Efficient large vision–language model for medical visual question answering. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2025, 189, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, E.; Ayache, S.; Favre, B. Towards an exhaustive evaluation of vision-language foundation models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (339–352), Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Areerob, K.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Li, X.; Inadomi, S.; Shimada, T.; Kanasaki, H.; Okatani, T. Multimodal artificial intelligence approaches using large language models for expert-level landslide image analysis. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2025, 40, 2900–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhariri, E.; El-Bendary, N.; Taie, S.A. Historical-crack18-19: A dataset of annotated images for non-invasive surface crack detection in historical buildings. Data Brief 2022, 41, 107865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özgenel, Ç.F. Concrete Crack Images for Classification [Data Set]; Mendeley Data: Online, 2019; V2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransom, W.H. Building Failures: Diagnosis and Avoidance; Longman: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, D.S. Building Pathology: Principles and Practice, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Building Research Establishment (BRE). Assessing Cracks in Houses, Digest 251. 2014. Available online: https://bregroup.com/insights/assessing-cracks-in-houses (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Online, 25–29 April 2022; Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=nZeVKeeFYf9 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Gardner, N.; Khan, H.; Hung, C.-C. Definition modeling: Literature review and dataset analysis. Appl. Comput. Intell. 2022, 2, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attribute | Text Description Example Used for Training |

|---|---|

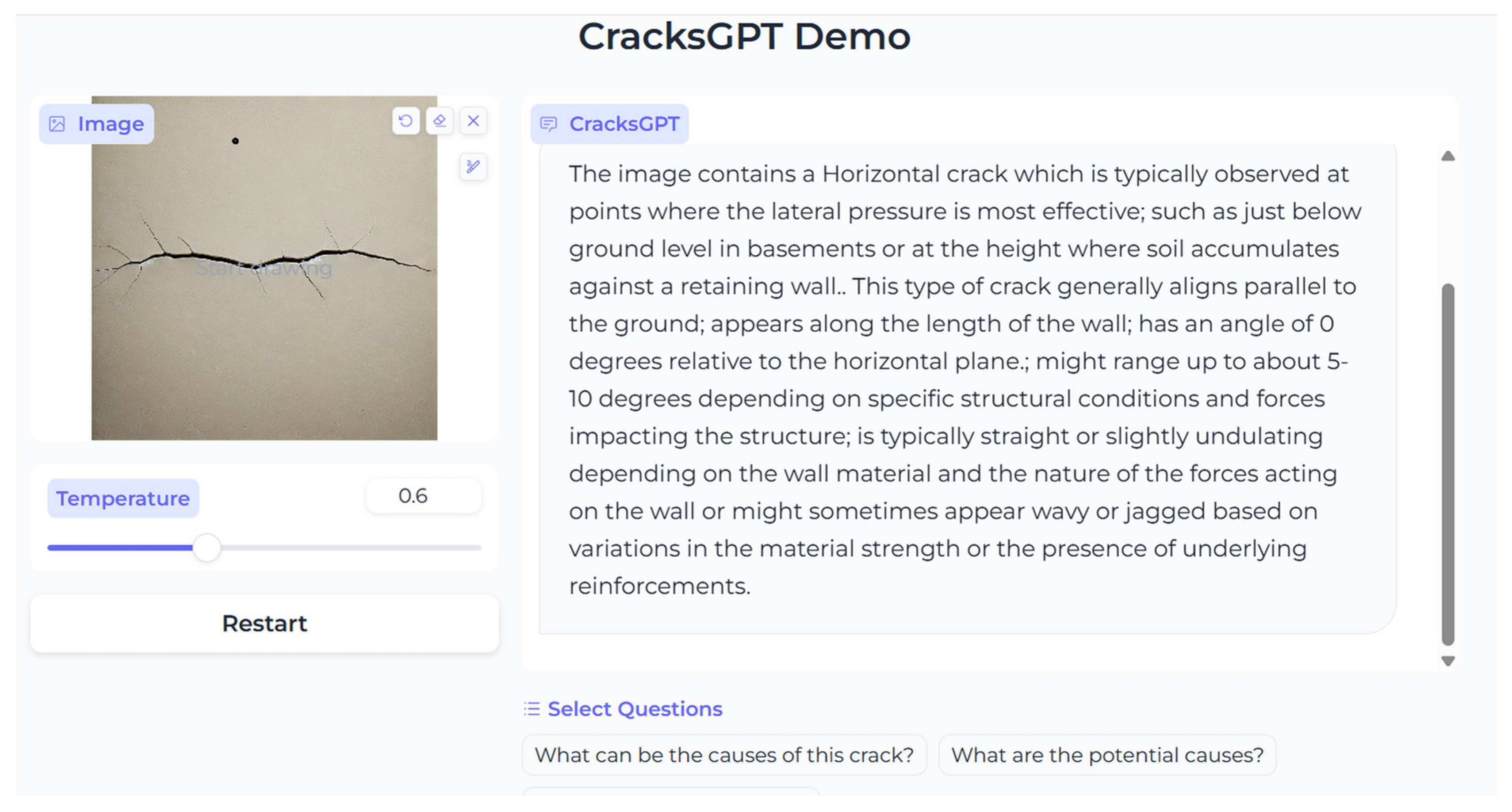

| Crack type |  Horizontal crack |

| General appearance | Horizontal cracks in walls are generally aligned parallel to the ground and appear along the length of the wall. They might range up to about 5–10 degrees. These cracks are typically observed at points where the lateral pressure is most effective. |

| Possible common causes | Check whether the wall is a foundation wall, a basement wall, an internal partition wall or a structural wall. Horizontal cracks are often caused by lateral pressure exerted by the surrounding soil, particularly due to changes in soil moisture content. As the soil expands and contracts, it can exert lateral pressure on the walls, leading to cracking. Another reason would be hydrostatic pressure. Water accumulating in the soil around a building’s foundation can create hydrostatic pressure, pushing against the walls and leading to cracking. Inadequate reinforcement, poor material quality, or improper curing during construction can lead to horizontal cracks. If upper levels are added or modified without adequately reinforcing the lower structures, it can exceed the design capacity of the walls or foundation and cause horizontal cracks. Uneven settling or heaving of the soil, often caused by frost or expansive soil in cold climate regions, can lead to horizontal cracking. |

| Potential rectification strategies based on severity | To determine the strategies for rectifying the cracks, the severity of the crack needs to be identified. To define the severity of cracks, refer to the guidelines provided by the Building Research Establishment (BRE) Digest 251 (2014) [51]. 0—Hairline cracks: Less than 0.1 mm in width. 1—Fine cracks: Up to 1 mm in width. 2—Cracks easily filled: Up to 5 mm in width. 3—Cracks that require opening: Widths of 5–15 mm. 4—Extensive damage: Widths of 15–25 mm. 5—Structural damage: Widths greater than 25 mm. In general, categories 0, 1, and 2 with crack widths up to 5 mm can be regarded as minor cracks and ‘aesthetic’ issues that require only redecoration. Categories 3 and 4 can generally be regarded as moderate cracks causing ‘serviceability’ issues, which affect the tightness of the building and the operation of doors and windows. Category 5 presents serious cracks with ‘stability’ issues and is likely to require structural intervention. For minor cracks, epoxy injections can be used to fill the cracks, sealing them and preventing water intrusion. Monitor the cracks for changes and further development over time. For moderate to serious cracks, professional consultation is needed for rectification purposes. |

| Professional consultation with a human expert | CracksGPT is an AI tool and cannot provide context specific advice. Consulting with a professional (building inspector, building surveyor, general contractor, specialised crack rectification contractor, structural engineer), is crucial to diagnose the exact causes of cracks and select the most appropriate rectification techniques. |

| ROUGE Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Model | Metrics | Rouge | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

| 1 | MiniGPT-v2 | ROUGE per response | Rouge-1 | 0.1786 | 0.5381 | 0.2351 |

| 2 | Rouge-2 | 0.0350 | 0.1163 | 0.0486 | ||

| 3 | Rouge-L | 0.0978 | 0.2852 | 0.1235 | ||

| 4 | CracksGPT | ROUGE per response | Rouge-1 | 0.4347 | 0.7081 | 0.5315 |

| 5 | Rouge-2 | 0.2922 | 0.4743 | 0.3570 | ||

| 6 | Rouge-L | 0.3448 | 0.5606 | 0.4216 | ||

| 7 | MiniGPT-v2 | ROUGE per conversation | Rouge-1 | 0.1877 | 0.7075 | 0.2967 |

| 8 | Rouge-2 | 0.0549 | 0.2069 | 0.0868 | ||

| 9 | Rouge-L | 0.0822 | 0.3099 | 0.1299 | ||

| 10 | CracksGPT | ROUGE per conversation | Rouge-1 | 0.4709 | 0.7999 | 0.5928 |

| 11 | Rouge-2 | 0.3257 | 0.5532 | 0.4100 | ||

| 12 | Rouge-L | 0.3294 | 0.5595 | 0.4146 | ||

| Expert ID | Designation | Experience |

|---|---|---|

| E1 | Managing Director and a licensed Building Inspector of a Sydney based home inspection company | Over 30 years |

| E2 | Lead Building Inspector of a Sydney based property inspection company | Over 23 years |

| E3 | Lead Building Inspector Sydney based home inspection company | Over 20 years |

| E4 | Licensed Building Inspector of a Sydney based property inspection company | Over 17 years |

| E5 | Licensed Property Inspection Specialist of a Sydney based property inspection company | Over 15 years |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ekanayake, B.; Thengane, V.; Wong, J.K.-W.; Wilkinson, S.; Ling, S.H. CracksGPT: Exploring the Potential and Limitations of Multimodal AI for Building Crack Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 4327. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234327

Ekanayake B, Thengane V, Wong JK-W, Wilkinson S, Ling SH. CracksGPT: Exploring the Potential and Limitations of Multimodal AI for Building Crack Analysis. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4327. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234327

Chicago/Turabian StyleEkanayake, Biyanka, Vishal Thengane, Johnny Kwok-Wai Wong, Sara Wilkinson, and Sai Ho Ling. 2025. "CracksGPT: Exploring the Potential and Limitations of Multimodal AI for Building Crack Analysis" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4327. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234327

APA StyleEkanayake, B., Thengane, V., Wong, J. K.-W., Wilkinson, S., & Ling, S. H. (2025). CracksGPT: Exploring the Potential and Limitations of Multimodal AI for Building Crack Analysis. Buildings, 15(23), 4327. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234327