Abstract

Large-scale concrete box girders are prone to early-age cracking because of the hydration reaction. To expedite the winter construction of large-scale precast box girders while mitigating the risk of thermal cracking induced by hydration heat, this study performs in situ temperature field monitoring and investigates the strength development of concrete under various curing conditions. The temperature field is numerically simulated using finite element analysis software ABAQUS and the secondary development of the subroutine. A parametric analysis is conducted to evaluate the influence of insulation rooms, insulation temperatures, and concrete placing temperatures. The results indicate that thermal insulation during winter construction effectively accelerates the development of concrete strength and enhances production efficiency. Compared to natural curing conditions, elevated insulation temperatures increase the temperature difference between the web core and inner surface, while reducing the early-stage temperature differences between the web core and outer surface. To minimize excessive temperature differences in large-scale box girders caused by hydration heat and thermal insulation during winter construction, it is recommended to maintain the concrete placing temperature below 19 °C and the insulation temperature within the range of 15–20 °C.

1. Introduction

The temperature variation induced by hydration heat is prone to cause early-age cracking in large-scale concrete bridges, particularly during the early-age stage after the pouring of large-scale box girders. At this stage, the concrete strength of the girders is generally relatively low, and excessive temperature differences within the concrete will significantly increase the risk of early cracking [1,2]. Therefore, how to effectively mitigate such early-age cracking has long been a critical issue demanding urgent solutions in practical engineering applications. Some researchers have conducted numerous studies to investigate the early-age hydration heat temperature fields in various types of concrete bridge structures. Do et al. [3] conducted a finite element analysis (FEA) to examine the early-age thermal characteristics of concrete segmental box girders. A detailed FEA model of the segmental box girder is created to evaluate the influence of its flanges, webs, volume-to-surface area ratio, and hydration heat of cement on the temperature development of the segment box girder at an early age. Zhang et al. [4] employed ANSYS-based numerical simulations to characterize both the casting-induced temperature field and the associated thermal stress distribution in zero blocks of large-span high-strength concrete box girders; the characteristic thermal response patterns induced by hydration heat in such structures were obtained. Wang et al. [5] conducted comprehensive field measurements of hydration heat evolution in the root segment of cast-in-place box girder bridges, complemented by numerical simulations using Midas FEA. Their research demonstrated that the optimal formwork removal time for long-span prestressed concrete box girders depends on their hydration heat dissipation characteristics. Under normal meteorological conditions, a minimum duration of four days is recommended. However, existing research on temperature fields in concrete bridges has predominantly focused on normal curing conditions [6,7,8,9,10].

In recent years, with increasing difficulties in construction land acquisition, improving the quality and production efficiency of precast concrete components has become an inevitable trend. Among various techniques, thermal insulation curing has emerged as the most widely adopted method for accelerated girder curing. Current research on thermal insulation curing focuses on concrete test specimens or structural components such as T-beams and small box girders. He et al. [11] systematically investigated the mechanical property differences between steam-cured and standard-cured concrete at equivalent hydration degrees. Their experimental findings revealed that during the isothermal curing stage, an 8 h steam curing treatment significantly accelerated the development of concrete strength, with the resultant compressive strength achieving over 60% of the 28-day reference strength. Zeyad et al. [12] systematically investigated the influence of steam-curing regimes on the performance characteristics of concrete. The experimental results demonstrated that adding pozzolanic or complementary cement materials contributes to reducing the damage resulting from the application of steam-curing regimes on concrete at later ages. Zou et al. [13] conducted an experimental and numerical investigation into the effects of steam-curing parameters on the early-age thermal behavior of concrete T-beams. The results demonstrated that when maintaining an isothermal curing duration of 5 h at temperatures exceeding 60 °C, the temperature difference between the T-beam surface and the ambient environment surpassed 25 °C, consequently inducing surface cracking in the concrete. Cai et al. [14] investigated the optimization of steam-curing regimes for precast concrete T-beams. The experimental results demonstrated that a three-stage curing protocol comprising a 2 h heating phase to 50 °C, followed by a 7 h isothermal maintenance period and subsequent 1-h cooling stage, represented the most cost-effective solution while satisfying the initial prestressing tensioning requirements. Current research on early-age thermal fields focuses on the effects of concrete formulations [15,16], cement types [17,18], mix proportions [19,20], and admixtures [21,22,23,24], while studies investigating optimal insulation protocols remain limited. Furthermore, existing standards lack comprehensive provisions in this regard.

Large-scale box girders exhibit significant advantages such as high structural stiffness, excellent load-bearing capacity, rapid construction speed, and superior durability [25,26], which have led to their extensive application in China’s high-grade highway bridges and railway bridges. The standard spans of Chinese railway bridges are predominantly 24 m and 32 m, with a progressive trend toward adopting 40 m and even longer spans. To minimize the number of piers in deep-water areas, the approach bridge of the under-construction Xiangshan bay sea-crossing bridge, part of the Ningbo-Xiangshan intercity railway, adopts 60 m large-scale box girders for its superstructure. The 60 m precast box girders are the first application in China’s intercity railway. Large-scale box girders are prefabricated in a centralized factory and subsequently transported by ship for offshore installation. Due to limited prefabrication space and high formwork costs, only two casting beds and formworks are established. However, the slow strength development of concrete in winter conditions extends the occupation time of each casting bed to over 144 h per box girder, severely constraining construction progress. To address this, heated insulation rooms are proposed to accelerate production efficiency in winter. Compared to concrete members with smaller cross-sectional dimensions (e.g., T-beams and small box girders), large-scale box girders are more susceptible to early-age cracking induced by hydration heat, which significantly compromises the durability of concrete bridges. The decrease in durability of concrete is fatal for sea-crossing bridges. However, current research on thermal curing methods for large-scale box girders, particularly during winter construction, remains insufficient in both engineering practice and theoretical studies. Consequently, it is imperative to develop scientifically validated thermal heating strategies to address this technical challenge.

This study, grounded in practical engineering, acquired temperature field data and environmental monitoring measurements of a 60 m railway box girder during winter construction through field monitoring. Simultaneously, the strength development of concrete under different curing conditions is systematically investigated. Utilizing finite element analysis software ABAQUS 2021 and the secondary development of the subroutine, the temperature field of the large-scale box girder is simulated and validated against field-measured data. Based on the verified finite element model, the influence mechanisms of insulation rooms, insulation temperature, and concrete placing temperature on the temperature field of the large-scale box girder are further analyzed. The research findings provide both theoretical foundations and practical references for the rapid construction of large-scale box girders in the winter.

2. Materials and Experimental Work

2.1. Mixture Design of the Concrete

The concrete used for the 60 m box girder is C50 marine concrete with a density of 2400 kg/m3, and its mixture design is shown in Table 1. The C50 concrete used PII52.5 cement produced by Ningbo Conch Group Co., Ltd. in Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, China.

Table 1.

Mixture design of the concrete (kg/m3).

2.2. Experimental Programs

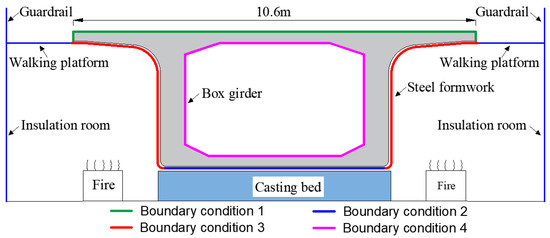

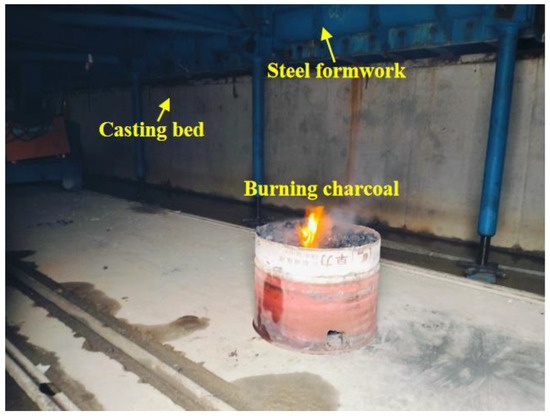

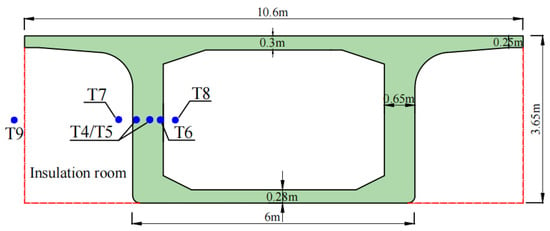

To enhance the production efficiency of large-scale box girders in the winter, the insulation rooms are installed exterior to the formwork system, and temperature heating is achieved by burning charcoal. The schematic diagram of the insulation room is illustrated in Figure 1, while the implementation of in situ heating is demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the insulation room.

Figure 2.

The implementation of in situ heating.

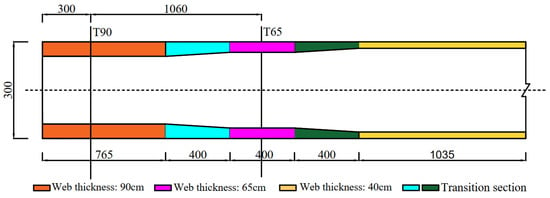

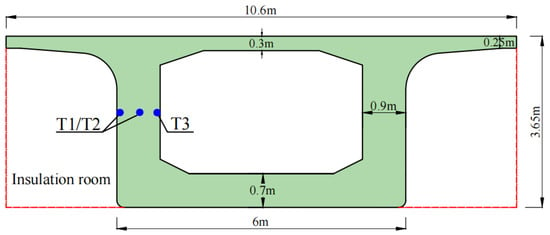

The 60 m box girder has an identical outer contour. Their webs primarily consist of three standard thicknesses of 90 cm, 65 cm, and 40 cm, complemented by progressively transitioning web segments. Temperature sensors are installed on the T90 and T65 sections of the 60 m box girder. These sections have thicker webs. The sensors can continuously monitor the early temperature field during prefabrication. The monitoring section diagram is illustrated in Figure 3. Temperature measurements are conducted using JMT-36B sensors (Changsha Jinma Co., Ltd., Changsha, China), with a measurement range of −30 to 120 °C and a sensitivity of ±0.1 °C. The measuring points arrangement of the T90 and T65 sections is shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5. Specifically, measurement points T1, T2, and T3 are installed at section T90, while T4, T5, and T6 are positioned at section T65. Points T7 and T8 are primarily used to monitor the ambient temperature inside and outside the box girder, respectively. Measurement point T9 is used to record atmospheric temperature. For temperature analysis, the time zero is set as the completion of concrete pouring for the box girder. Temperature data are acquired continuously at a frequency of once per hour until 95 h after pouring.

Figure 3.

Monitoring section diagram (Unit: cm).

Figure 4.

Measuring points arrangement of T90 section.

Figure 5.

Measuring points arrangement of T65 section.

The in situ prefabrication and testing of the 60 m railway box girder are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The in-situ prefabrication and testing of the 60 m box girder.

2.3. Strength Development of Concrete Under Various Curing Conditions

The axial compression tests on concrete were conducted in accordance with the Chinese standard GB/T 50081-2019 (“Standard for test methods of concrete physical and mechanical properties”) [27]. Prismatic specimens measuring 150 mm × 150 mm × 300 mm were employed, with three specimens tested per group. The average value of the test results from these three specimens was taken as the final axial compressive strength.

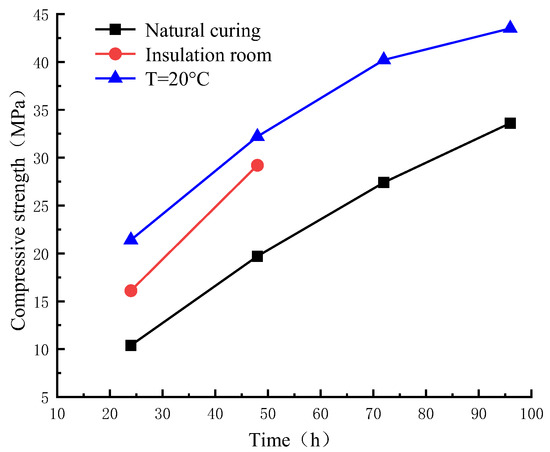

Figure 7 presents the axial compressive strength of concrete cube specimens under different curing conditions at the ages of 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 96 h. As illustrated in Figure 7, the ambient temperature has a significant influence on the cement hydration reaction, with higher temperatures generally accelerating the strength development of concrete. Under natural curing conditions, the lower ambient temperature decelerates the hydration reactions, consequently leading to a slower rate of concrete strength development. In the absence of proper construction interventions, this would inevitably constrain the production efficiency of precast box girders. Moreover, at 72 h, the concrete strength reaches only 27.4 MPa, which remains insufficient to satisfy the initial prestressing tensioning requirements. Consequently, it is challenging to mitigate cracking in box girders at this stage using pre-tensioning techniques. In contrast, under a constant 20 °C curing condition, the concrete exhibits the most rapid strength development, achieving 32.2 MPa at 48 h, which exceeds 60% of the design strength for C50-grade concrete. Under insulation room conditions, the concrete strength reaches 29.2 MPa at 48 h, approximately meeting 60% of the design strength for C50-grade concrete and thereby satisfying the prestressing tensioning criteria. In actual box girder construction, prestressing tensioning is completed at 53 h, followed by the removal of the insulation room and steel formwork at approximately 54 h. Thus, only 24 h and 48 h strength data are recorded for the insulation room condition. The rate of strength development under insulation room conditions lies between that of natural curing and 20 °C constant-temperature curing conditions. This is primarily attributable to the thermal environment in the insulation room, where temperatures fluctuated between 6.1 and 23.0 °C. Thermal insulation moderately enhances concrete strength but remains less effective than a constant-temperature condition of 20 °C. Therefore, in winter conditions, implementing heating and insulation measures can effectively promote concrete strength development in box girders and improve production efficiency.

Figure 7.

The axial compressive strength of concrete under different curing conditions.

3. Comparative Analysis of Measured Results and Numerical Simulation

3.1. Heat Transfer Modeling

- (1)

- Model parameters

According to Zhu’s research [28], the early self-heating process of concrete under adiabatic conditions follows a compound exponential trend, which could be mathematically expressed in Equation (1).

where Qt denotes the hydration heat at age t (J/kg), Q0 represents the total hydration heat generated by complete cement hydration (J/kg), and its value can be assumed as 3.64 × 106 J/kg. a and b are coefficients with the values of 0.36 and 0.74, respectively.

The heat diffusion equation governing the internal temperature distribution in the concrete box girder is expressed as Equation (2) [29].

where λ is the thermal conductivity (J/(m·h·°C)), T refers to temperature (°C), ρ denotes the density of concrete (kg/m3), Cp represents the specific heat capacity (J/(kg·°C)), and Qh stands for the rate of heat generation per unit volume (J/(h·m3)).

The exothermic heat generated during cement hydration significantly influences the reaction rate, necessitating the introduction of equivalent age as a critical parameter to account for temperature-dependent effects. To address this problem, Hansen et al. [30] derived a new formulation for equivalent age, incorporating the concrete’s temperature history, as shown in Equation (3). This formulation, grounded in the Arrhenius equation, quantitatively captures the coupled influence of thermal activation and maturation time on the hydration process.

The hydration degree α, defined as the mass fraction of cement consumed in the hydration reaction relative to the initial cement content, serves as a fundamental metric for reaction progress. This dimensionless parameter, bounded between 0 and 1, exhibits a direct correlation with adiabatic temperature rise under thermally insulated conditions. The quantitative relationship is shown in Equation (4).

where a(te) is the hydration degree of the concrete at the equivalent age te, Q(te) is the hydration heat released at equivalent age te, and Q0 represents the final hydration heat.

During the curing process of concrete, the thermal conductivity varies as a function of the degree of hydration. The evolution of early-age thermal conductivity can be described by the linear relationship proposed by Schutter [31]. As indicated in Equation (5), the thermal conductivity exhibits a gradual decrease with an increasing hydration degree.

where λ(α) denotes the thermal conductivity at a specific hydration degree α, and λu represents the final thermal conductivity upon complete hardening, with values assigned as 8830 J/(m·h·°C).

The early-age specific heat of concrete is influenced by temperature, water–cement ratio, and degree of hydration. To account for these dependencies, the empirical relationship established by Van Breugel [32], as shown in Equation (6).

where c denotes the specific heat. W is the mass, with subscripts c, a, and w corresponding to the cement, concrete aggregate, and water, respectively. The density of concrete is represented by ρ (kg/m3), and ccef is an assumed specific heat defined by the linear relation ccef = 0.0084 × Tc + 0.339, in which Tc is the current temperature (°C). The specific heat of the cement, concrete aggregate, and water is assigned as follows: cc = 930 J/(kg·°C), ca = 678 J/(kg·°C), and cw = 4187 J/(kg·°C).

- (2)

- Heat-transfer coefficient

The heat-transfer coefficient β of a solid surface exhibits significant dependence on both the surface roughness and ambient wind speed. Zhu [33] proposed a theoretical equation to calculate the heat-transfer coefficient of a rough surface.

Under conditions where formwork or other thermal insulation layers are present at the concrete surface, the temperature distribution can be effectively characterized using the third-type boundary conditions. In this case, the equivalent heat-transfer coefficient βe quantitatively describes the composite thermal resistance governing heat flux dissipation from the concrete substrate to the air through the layered system, as mathematically represented in Equation (8).

where β0 represents the heat-transfer coefficient of concrete in the air, hi denotes the thickness of the thermal insulating layer, and λi is the thermal conductivity of the insulating material. In cases where steel formwork is present on the concrete surface, an equivalent heat-transfer coefficient that incorporates the influence of the steel formwork should be employed for the air-concrete interface.

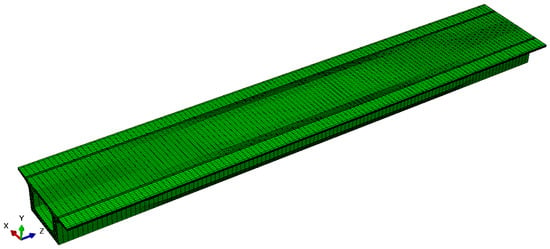

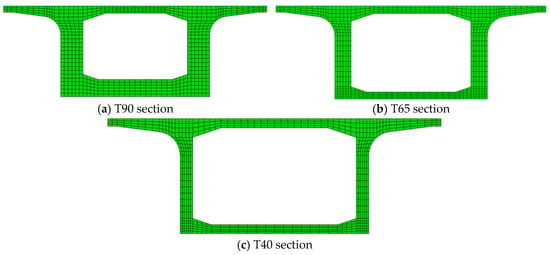

3.2. Finite Element Model

Finite element analysis software ABAQUS and the secondary development of the subroutine are used to simulate the transient temperature field of a 60 m precast box girder during early hydration. The analysis employed DC3D8 elements (eight-node linear hexahedral heat transfer elements) to discretize the thermal field model. The computational domain, following mesh refinement, comprised 75,208 elements and 90,720 nodes, with element sizes ranging from 60 mm to 400 mm. Figure 8 illustrates the finite element model of the 60 m precast concrete box girder, and Figure 9 presents the localized mesh distributions at the T90 section, T65 section, and T40 section.

Figure 8.

Finite element model of 60 m precast concrete box girder.

Figure 9.

The localized mesh distributions of three typical sections.

The temperature boundary conditions for the large-scale box girder are categorized into four types, as detailed in Figure 1. Boundary Condition 1: The top and side surfaces of the top slab are exposed to ambient air, accounting for the influence of natural wind speed. Boundary Condition 2: The bottom surface of the bottom slab is set in contact with the steel formwork, with no wind speed effect considered. Boundary Condition 3: The outer surfaces are defined to be in contact with steel formwork for the initial 54 h, during which no wind speed is considered when the insulation room is deployed. The time-dependent temperature in the insulation room is applied as a Boundary Condition to the external surfaces of the box girder, and an equivalent heat dissipation coefficient is employed in the numerical model. After the steel formwork removal at 54 h, these surfaces are exposed to ambient air, and the natural wind speed effect is incorporated. Boundary Condition 4: The interior surfaces of the box girder are exposed to the internal air. However, due to the coverage by geotextiles at both ends, the wind speed effect inside is neglected. In the numerical model, the thicknesses of the bottom and side formworks were specified as 10 mm and 8 mm, respectively. The thermal conductivity of steel formwork is 163.3 kJ/(m·h·°C). A transient analysis is performed, in which the initial temperature of the box-girder concrete is set to its placing temperature. The adopted time step is specified as 1 h, with a total analysis duration of 95 h.

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Measured Results and Numerical Simulation

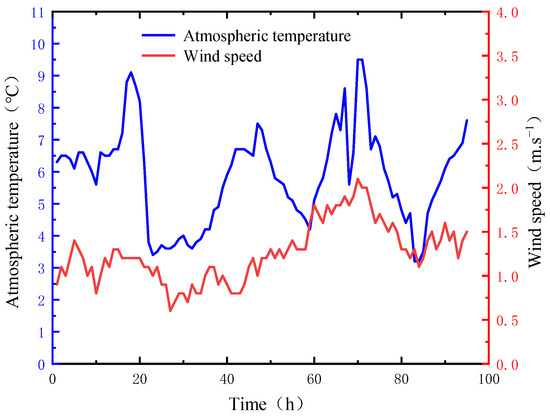

Figure 10 presents the field-measured atmospheric temperature and wind speed data recorded during the first 95 h after box girder casting. The monitored winter ambient temperature ranges from 3.2 to 9.5 °C, with wind speeds varying between 0.6 and 2.1 m/s.

Figure 10.

Actual measured atmospheric temperature and wind speed.

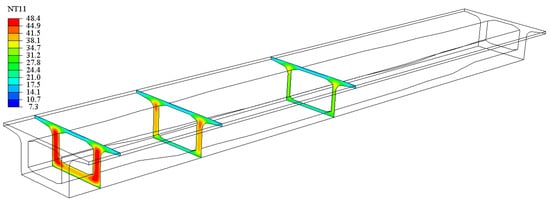

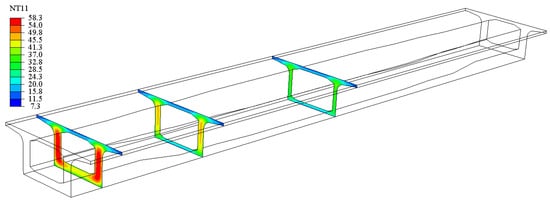

The hydration heat temperature field during the first 95 h of precast concrete box girders is simulated. Figure 11 and Figure 12 present the simulated temperature distributions at three representative sections at 30 h and 54 h. The top and bottom slabs, characterized by their relatively smaller thickness, exhibit lower temperatures due to the small heat production of the concrete and favorable heat dissipation conditions at the boundaries. High-temperature regions in the end segments are primarily concentrated in the webs of the box girder; while in the T65 and midspan segments, these regions are predominantly located at the web and top-web junction. These results demonstrate that the temperature field in the web region requires particular attention during the early-age hydration stage. Consistent with previous engineering experience, early-age cracks in large box girders mainly occur at the web and top-web junction, with vertical cracks being the most prevalent type. Therefore, the theoretical analysis of the temperature field is consistent with common crack disease.

Figure 11.

Temperature field of 60 m box girder test sections at 30 h.

Figure 12.

Temperature field of 60 m box girder test sections at 54 h.

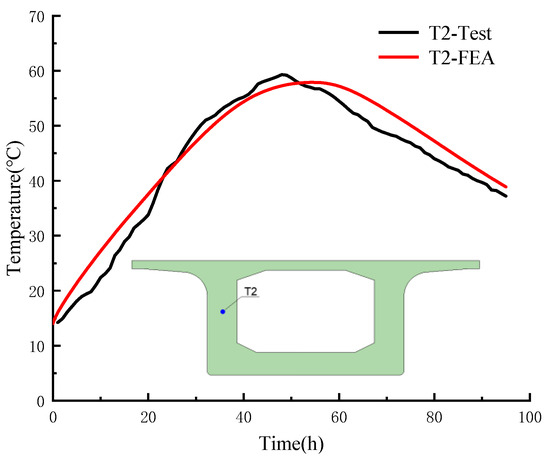

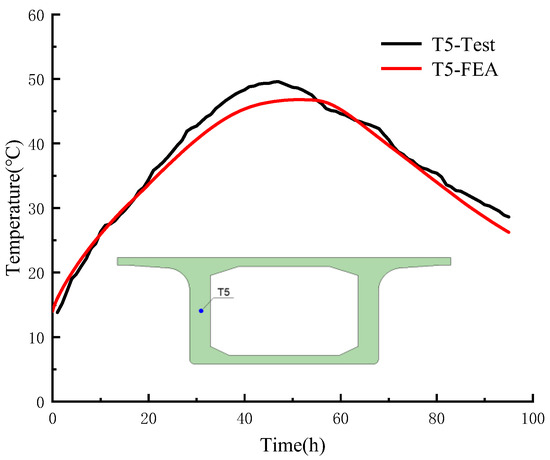

Figure 13 and Figure 14 present the comparison between the test and numerical results in two sections. The results demonstrate that during the early-age prefabrication stage, the temperature evolution in the box girder webs follows a characteristic “heating-up, high-temperature maintenance, and cooling-down” trend. The simulation results show good agreement with the measured temperature development patterns. The peak temperature exhibits a positive correlation with the local geometric dimensions of box girder sections. The T90 section with thicker webs has higher peak temperatures than the T65 section. The reason is that the peak hydration temperature is principally governed by sectional size effects, wherein larger concrete volumes experience greater heat accumulation due to the greater heat production of the concrete. For the T90 section, the measured and simulated peak temperatures are 59.3 °C and 57.9 °C, respectively, showing a minor deviation of 2.4%. The measured and simulated peak temperatures of the T65 section are 49.6 °C and 47.0 °C, corresponding to a 5.2% deviation. Considering the complexity of temperature field development in large-scale box girders under winter construction conditions, it can be considered that the numerical simulations demonstrate satisfactory agreement with field measurements. The finite element model effectively simulates the essential characteristics of hydration heat-induced temperature fields in precast concrete box girders.

Figure 13.

Comparison between the test and numerical results in the T90 section.

Figure 14.

Comparison between the test and numerical results in the T65 section.

4. Test Results and Discussions

4.1. Influence of Insulation Room

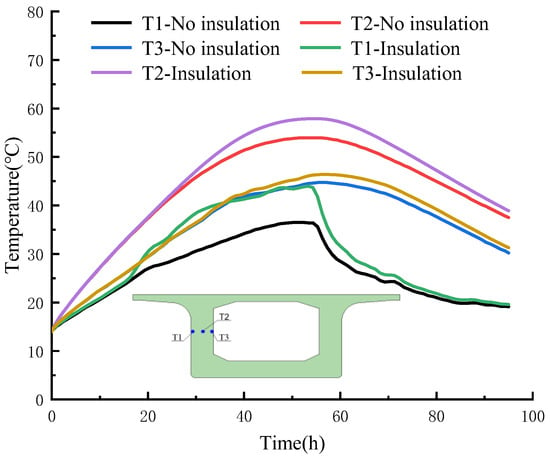

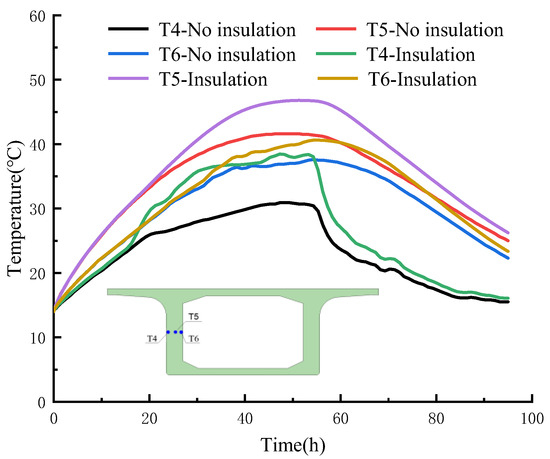

To investigate the influence of the insulation room on the temperature field of box girders, a validated finite element model, as demonstrated in previous experiments, is employed. By altering the heat dissipation conditions of the box girder, the development of hydration heat under natural curing conditions (without an insulation room) is simulated and compared with the results obtained under insulation room conditions. Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17 present the temperature comparisons at key measuring points on the web of three representative sections. The results indicate that before 54 h, the temperature variation in the girder remains relatively stable. However, after 54 h, the temperature on the outer surface of the box girder web exhibits a sharp decline. This phenomenon can be attributed to the removal of the external formwork after 54 h, which significantly alters the heat dissipation conditions on the outer surface of the box girder. The exposed concrete experiences a significantly enhanced heat exchange rate with the ambient air, leading to a pronounced temperature drop on the outer web.

Figure 15.

The temperature comparisons on the web of the T90 section.

Figure 16.

The temperature comparisons on the web of the T65 section.

Figure 17.

The temperature comparisons on the web of the T40 section.

As illustrated in Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17, compared to natural curing conditions, the temperatures at the web of three sections under the insulation room exhibit notable increases. Specifically, for the T90 section, the peak temperatures at the core, outer surface, and inner surface of the web increase by 4.0 °C, 8.1 °C, and 1.8 °C, respectively, with the maximum temperature differences occurring at 55 h, 32 h, and 59 h. For the T65 section, the corresponding temperature increments are 5.3 °C, 8.0 °C, and 3.1 °C, with maximum differences observed at 55 h, 33 h, and 55 h. For the T40 section, the increases in peak temperatures reach 6.9 °C, 8.0 °C, and 5.1 °C, with maximum differences manifesting at 53 h, 33 h, and 48 h. The results demonstrate that the insulation room exerts the most pronounced influence on the outer web temperature, followed by the core region, while the inner surface is the least affected. Furthermore, a comparative analysis of the three sections reveals that the thinner web exhibits more significant temperature increases in both the core and inner regions. Notably, the outer web temperature consistently increases by approximately 8.0 °C across all sections. This uniformity can be attributed to the fact that, before formwork removal, the outer surface temperature is primarily governed by the air temperature in the insulation room, whereas after formwork removal, it is predominantly influenced by the ambient environment. Notwithstanding variations in local sectional dimensions, the lateral surfaces of the box girder maintain identical heat dissipation conditions, consequently yielding comparable temperature increments in the outer web.

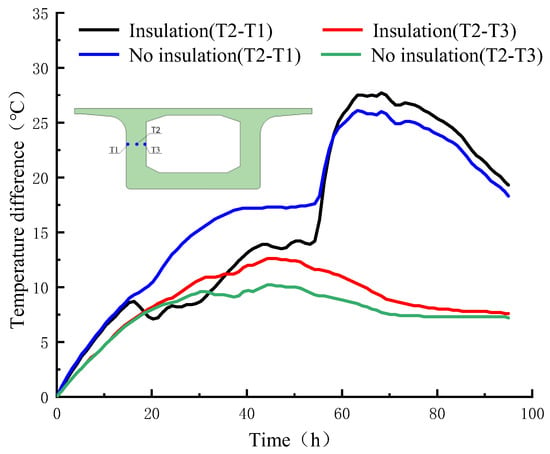

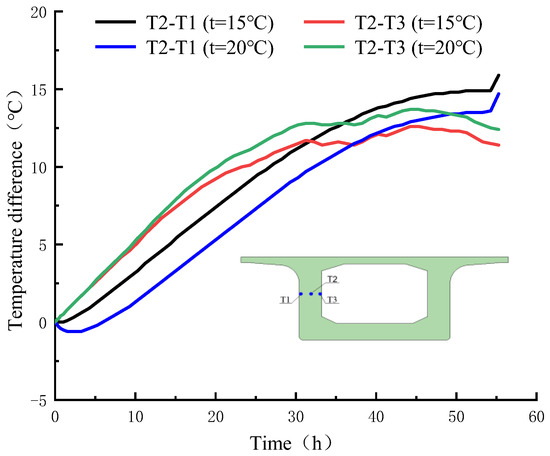

Figure 18 and Figure 19 present the temperature variation in key measurement points of the T90 and T65 sections with relatively large web thicknesses. As can be seen from the figures, compared with natural curing conditions, the temperature difference between the core and inner surface of the web increases under insulation room conditions. For the T90 section, the maximum increase in temperature difference between the core and inner surface of the web is 2.5 °C, with the peak increase occurring at the 46th hour. For the T65 section, the maximum increase in temperature difference is also 2.5 °C, with the peak increase occurring at the 39th hour. The temperature differences between the core and inner surface of the web remain relatively small under both curing conditions. Under natural curing and insulation room conditions, the web temperature differences for the T90 section are within 10.2 °C and 12.6 °C, respectively, while those for the T65 section are within 7.4 °C and 5.3 °C, respectively.

Figure 18.

Variation in temperature differences in the T90 section.

Figure 19.

Variation in temperature differences in the T65 section.

Regarding the temperature difference between the web core and outer surface, during the initial 57 h, the temperature difference in the box girder under natural curing conditions exceeds that observed under the insulation room condition. However, after the 57th hour, the temperature difference under natural curing conditions became smaller than that in the insulation room. Table 2 presents the statistical analysis of temperature differences during the first 48 h and 63 h. Under natural curing, the maximum temperature differences are 26.1 °C for the T90 section and 17.0 °C for the T65 section in the first 63 h. Under the insulation room condition, these differences increase to 27.5 °C and 19.0 °C, respectively. This means the temperature difference in the webs rises by 1.4 °C for the T90 section and 2.0 °C for the T65 section. In both curing conditions, the peak temperature difference occurred around 63 h. Evidently, the temperature gradients in the web regions of both sections are significantly higher at this stage, posing a substantial risk of cracking in the box girder webs if no construction mitigation measures are implemented. It is worth noting that before the first 48 h, the maximum temperature differences in the T90 and T65 sections under the natural curing condition are 17.3 °C and 11.2 °C, respectively, while under the insulation room condition, the differences are 13.9 °C and 12.5 °C, reflecting a reduction of 3.4 °C and 1.3 °C in the web temperature difference for the T90 and T65 sections, respectively. This demonstrates that the application of the insulation room effectively mitigates the temperature gradient between the core and outer surface of the box girder webs during the early age stages.

Table 2.

Temperature differences in the web under different curing conditions.

Based on the aforementioned strength development patterns of concrete under different curing conditions, under natural curing, the concrete strength at 72 h reaches only 27.4 MPa, which still fails to satisfy the initial prestressing tensioning requirements. Consequently, it is difficult to mitigate cracking in the box girder through early prestressing tension at this stage. In comparison with the implementation of thermal insulation measures, the concrete strength in the insulation room reaches 29.2 MPa at 48 h, achieving approximately 60% of the design strength for C50 concrete. This allows for early prestressing tension, significantly improving crack resistance. For the insulation room curing condition, during the first 48 h, the temperature differences in the T90 section are confined within 13.9 °C (core and outer surface) and 9.0 °C (core and inner surface), while those in the T65 section remain within 12.5 °C (core and outer surface) and 7.4 °C (core and inner surface). These results indicate that the temperature differences in the webs are well controlled. By applying timely prestressing tension and ensuring sufficient compressive stress reserves in the box girder, the risk of early-age cracking in the box girder webs can be effectively mitigated. Therefore, during construction in the winter, the adoption of the insulation room not only accelerates the prefabrication process of large-scale box girders but also effectively addresses early cracking induced by excessive temperature differences in the concrete. This approach ensures both construction efficiency and structural durability.

4.2. Influence of Insulation Temperature

Field measurements indicate that the ambient temperature during winter ranges from 3.2 to 9.5 °C. Considering that the measured air temperature inside the insulation room after heating varies between 6.1 and 23 °C, this study investigates the early-age thermal field of box-girder concrete under five insulation temperatures (10 °C, 15 °C, 20 °C, 25 °C, and 30 °C) to determine the optimal thermal insulation strategies based on practical constructability.

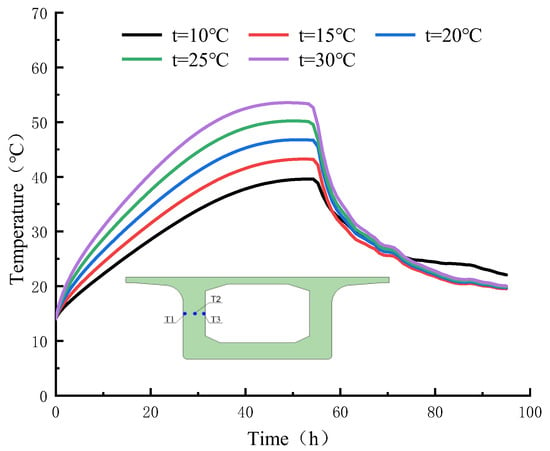

4.2.1. Influence of Insulation Temperature on Box Girder’s Peak Temperature

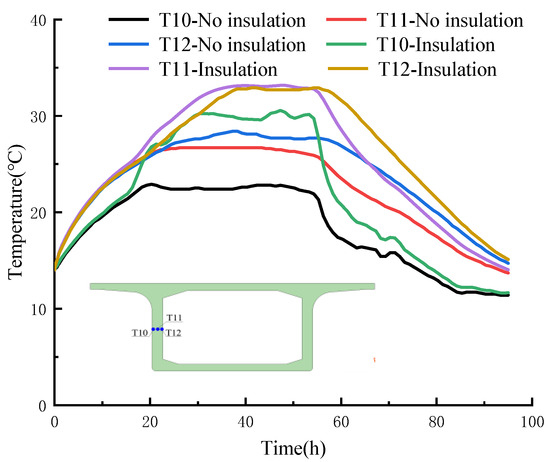

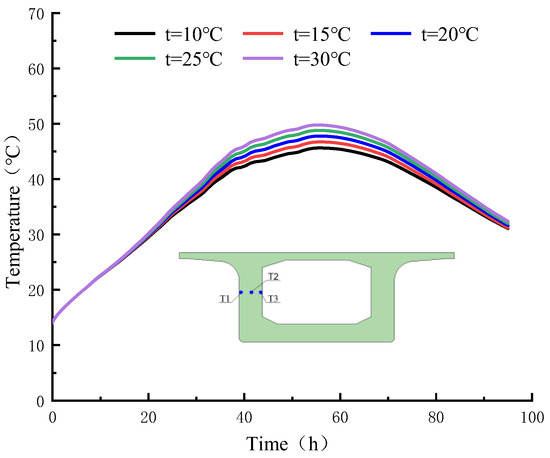

Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24 and Figure 25 present a comparison of the web temperatures in the box girder under five insulation temperatures. The maximum temperature on the web consistently occurs at the core. As the temperature in the insulation room increases, the maximum temperature of the box girder also rises. Under the five insulation temperature conditions, the peak temperatures observed in the web vary significantly among different sections. The T90 section exhibits the highest temperatures, ranging from 55.9 to 64.2 °C, the T65 section shows a moderate range of 44.2 to 55.3 °C, and the T40 section remains comparatively cooler, with peak temperatures between 29.9 and 43.5 °C. When the insulation temperature rises from 10 °C to 30 °C, for every 5 °C increase, the peak temperature in the T90 section increases by 1.9–2.2 °C, the peak temperature in the T65 section rises by 2.7–2.9 °C, and the peak temperature in the T40 section increases by approximately 3.4 °C. This indicates that increasing the insulation temperature has a more pronounced effect on thinner sections.

Figure 20.

Temperature variation of measuring point T1 in the outer web of the T90 section.

Figure 21.

Temperature variation of measuring point T2 in the web core of the T90 section.

Figure 22.

Temperature variation of measuring point T3 in the inner web of the T90 section.

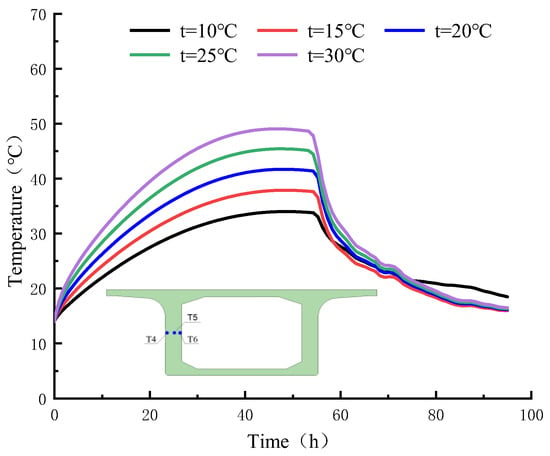

Figure 23.

Temperature variation of measuring point T4 in the outer web of the T65 section.

Figure 24.

Temperature variation of measuring point T5 in the web core of the T65 section.

Figure 25.

Temperature variation of measuring point T6 in the inner web of the T65 section.

The insulation temperature has essentially no significant effect on the timing of the peak temperature in the box girder. The peak temperatures in the webs of the T90, T65, and T40 sections occur at approximately 53 h, 48 h, and 41 h, respectively, indicating that the timing of peak temperatures varies significantly across different sections. The reason is that thicker webs generate more hydration heat. Under identical boundary heat dissipation conditions, this leads to progressive heat accumulation within the box girder, consequently delaying the occurrence of the peak temperature. It is noted that the peak temperature in the T90 section with thicker webs occurs at 53 h, primarily due to the assumption that the external formwork is removed for thermal dissipation calculations commencing at the 54th hour. Subsequently, the exposed web concrete rapidly dissipates heat, resulting in a pronounced cooling trend on the exterior surfaces of the box girder.

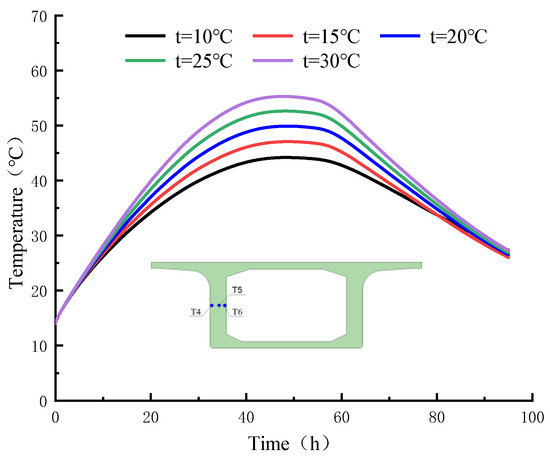

4.2.2. Influence of Insulation Temperature on Box Girder’s Temperature Difference

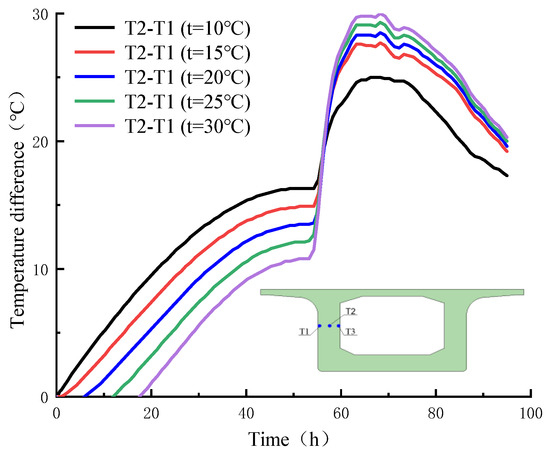

The temperature difference between the core and outer surface of the web is significantly greater than that between the core and inner surface. Figure 26 and Figure 27 present comparative data on temperature differences between the web core and outer surface under five different insulation temperatures. The results demonstrate that the maximum temperature difference in the T90 section substantially exceeds that in the T65 and T40 sections. Furthermore, before 58 h, higher curing temperatures result in smaller temperature differences between the web core and outer surface. However, after exceeding 58 h, higher curing temperatures lead to greater temperature differences, demonstrating an opposite influence pattern in the early and late stages. The observed phenomenon primarily results from the formwork removal at 54 h. Before removing the external formwork in the early stage, a higher insulation temperature is beneficial for increasing the temperature on the outer surface of the box girder, thereby reducing the temperature difference between the web core and the outer surface. However, after formwork removal at 54 h, the outer surfaces lost their thermal insulation protection and became directly exposed to ambient conditions. Since a higher insulation temperature leads to a higher temperature on the outer surface of the web, after the formwork is removed, the outer surface exhibits rapid cooling, whereas the core temperature declines at a significantly slower rate. This thermal behavior explains why the temperature difference between the web core and the outer surface exhibits an opposite influence trend before and after the 58 h. Notably, both T90 and T65 sections exhibit identical patterns of thermal response.

Figure 26.

Temperature differences between the web core and outer surface of T90 section.

Figure 27.

Temperature differences between the web core and outer surface of T65 section.

From Figure 26 and Figure 27, it can also be observed that the increase in insulation temperature has little influence on the timing of the maximum temperature difference between the core and outer surface of the web. For the T90 section, the maximum temperature difference occurs around 68 h, while for the T65 and T40 sections, it appears at approximately 63 h and 58 h, respectively. This indicates that as the web thickness increases, the occurrence of the maximum temperature difference is delayed. The peak temperatures of the web in the T90, T65, and T40 sections are reached around 53 h, 48 h, and 41 h, respectively, demonstrating that the maximum temperature difference between the core and outer surface occurs after the temperature peaks. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the removal of the outer formwork at 54 h.

The uniaxial compression test results of concrete under different curing conditions indicate that after implementing insulation measures, the box girder meets the prerequisites for prestressing tension at 54 h. At this stage, endowing the box girder with a certain reserve of compressive stress can effectively inhibit the formation of concrete cracks. Therefore, the analysis focuses on the temperature differences before 54 h. During the initial 54 h period, the maximum temperature difference between the web core and outer surface under five curing temperatures exhibits a gradual increase, peaking at the 54 h mark. This suggests that as time progresses after the completion of box girder pouring, the risk of web cracking steadily rises. However, as the insulation temperature increases, the maximum temperature difference shows a gradual declining trend. A 5 °C increase in insulation temperature reduces the maximum temperature difference by 0.9–1.4 °C in the T90 section, 0.5–1.0 °C in the T65 section, and 0.1–0.5 °C in the T40 section. These findings demonstrate that raising the insulation temperature helps reduce the temperature difference between the web core and outer surface, with a more pronounced effect observed in thicker web sections.

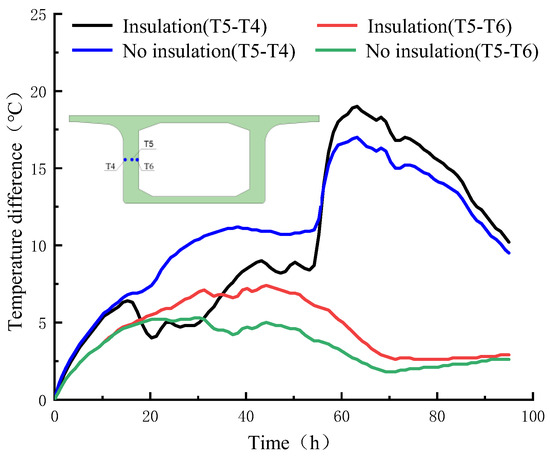

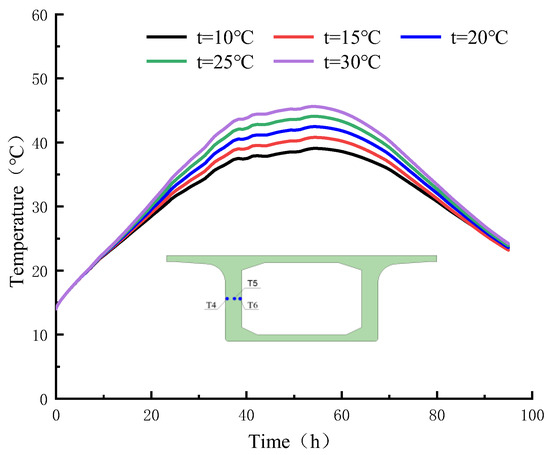

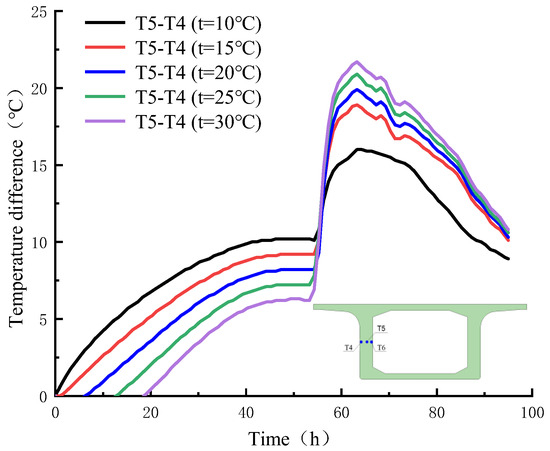

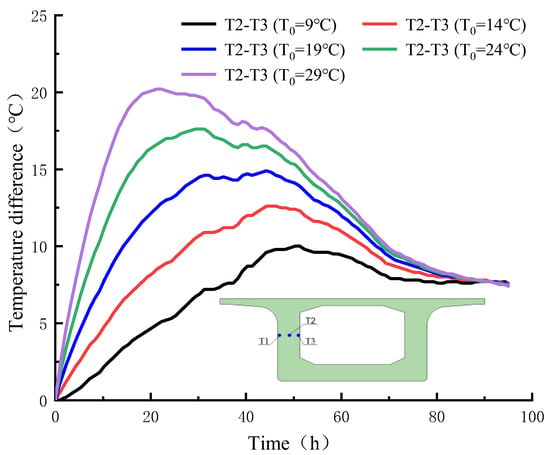

Figure 28 and Figure 29 present the temperature differences between the web core and inner surface under five different insulation temperatures. As the insulation temperature increases, the maximum temperature difference between the web core and inner surface shows an increasing trend, indicating that higher insulation temperatures elevate the risk of concrete cracking on the inner web surface. For the five insulation temperatures, the maximum temperature difference in the T90 section ranges from 11.3 °C to 15.9 °C, and the maximum temperature difference in the T65 section ranges from 5.0 °C to 10.6 °C. In all cases, the peak temperature difference occurs at approximately 44 h, indicating that web thickness variations do not affect the timing of this peak between the web core and inner surface.

Figure 28.

Temperature differences between the web core and inner surface of T90 section.

Figure 29.

Temperature differences between the web core and inner surface of T65 section.

Table 3 presents a comparison of temperature differences in the T90 and T65 sections during the first 95 h. Compared to the maximum temperature difference between the web core and outer surface, the maximum temperature difference between the core and inner surface of the same section is relatively smaller. For the T90 section, the latter ranges from 45.2% to 53.0% of the former, while for the T65 section, it ranges from 29.4% to 48.8%. This is primarily because removing the external formwork after 54 h significantly alters the heat dissipation conditions at the web’s outer surface, leading to a drastic increase in the temperature difference between the core and the outer surface. Therefore, particular attention should be paid to controlling the temperature difference between the core and outer surface during winter construction.

Table 3.

Comparison of temperature differences in T90 and T65 sections.

The study on temperature differences between the web core and outer surface reveals that before 58 h, higher insulation temperatures result in smaller temperature differences between the core and outer surface. Conversely, research on the core and inner surface demonstrates that maximum temperature differences increase with rising insulation temperatures. These findings indicate opposing trends in how insulation temperature affects these two types of thermal differences. Further analysis shows distinct patterns under different curing conditions. At an insulation temperature of 10 °C, the temperature differences between the core and outer surface consistently exceed those between the core and inner surface. At an insulation temperature of 25 °C and 30 °C, the temperature differences between the core and outer surface remain consistently smaller than those between the core and inner surface. Figure 30 illustrates the temperature variation patterns in the section under insulation temperatures of 15 °C and 20 °C. At an insulation temperature of 15 °C, the temperature difference between the core and outer surface is smaller than that between the core and inner surface during the initial 32 h, but this relationship reverses from 33 to 55 h when the difference between the web core and outer surface becomes greater. Similarly, at an insulation temperature of 20 °C, the temperature difference between the core and outer surface remains smaller than that between the web core and inner surface for the first 49 h, then exceeds it from 50 to 55 h. These findings demonstrate that insulation temperatures between 15 °C and 20 °C achieve a balanced state between the core-to-exterior and core-to-interior temperature differentials. Therefore, to prevent concrete cracking on both the outer and inner surfaces of the web, it is recommended to maintain the insulation temperature within the range of 15 °C to 20 °C.

Figure 30.

Comparison of temperature differences in the first 55 h.

4.3. Influence of Placing Temperature

In actual construction, controlling the placing temperature of the box-girder concrete is relatively straightforward. To identify a suitable placing temperature, this study investigates the effects of concrete placing temperatures of 9 °C, 14 °C, 19 °C, 24 °C, and 29 °C on the temperature field distribution in a 60 m box girder.

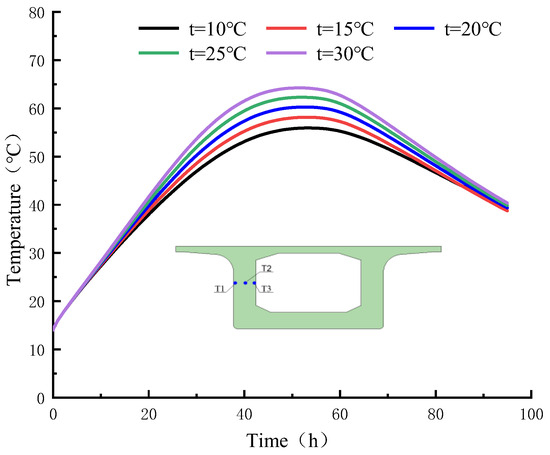

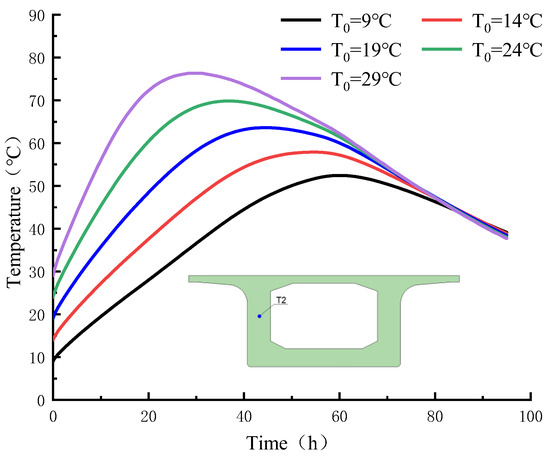

4.3.1. Influence of Pouring Temperature on Box Girder’s Peak Temperature

Table 4 presents the temperature distribution in the web of the box girder under different placing temperatures. For the five placing temperatures investigated, the peak temperatures in the web core range from 52.5 to 76.3 °C at the T90 section, 43.1 to 63.6 °C at the T65 section, and 31.9 to 44.3 °C at the T40 section. A 5 °C increase in placing temperature results in a peak temperature rise of 5.4–6.5 °C for the T90 section, 3.7–6.4 °C for the T65 section, and 1.3–4.8 °C for the T40 section. The influence of placing temperature on web temperature is more pronounced in the T90 section than in the T65 and T40 sections, primarily due to faster heat accumulation in the thicker web region, leading to higher thermal variations in the web core of the T90 section. Furthermore, the peak web temperature exhibits an accelerating growth trend with increasing placing temperatures.

Table 4.

Peak temperature of the web induced by different placing temperatures.

Figure 31 presents the influence of placing temperatures on the core temperature of the T90 section. With increasing placing temperature, the occurrence time of peak temperature advances significantly, and this temporal advancement becomes more pronounced at higher placing temperatures. However, although the placing temperature markedly affects both the peak temperature and its occurrence time in the web, the temperature curves ultimately converge to comparable amplitudes, indicating that the placing temperature has a negligible influence on the box girder’s final temperature during the cooling phase.

Figure 31.

The influence of placing temperatures on the core temperature of the T90 section.

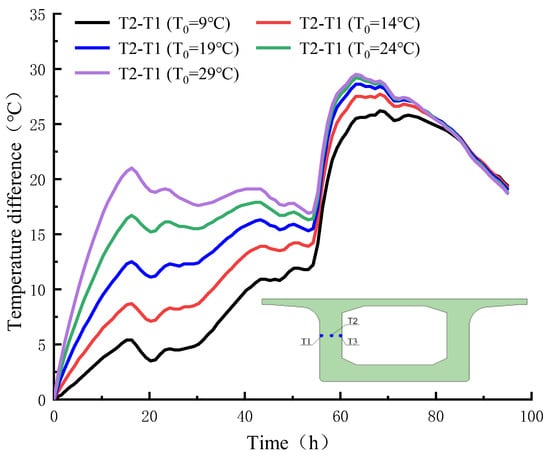

4.3.2. Influence of Pouring Temperature on Box Girder’s Temperature Difference

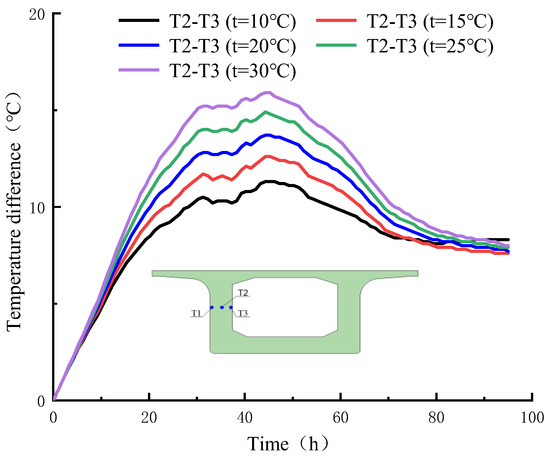

Figure 32 presents the influence of placing temperatures on the temperature differences between the web core and outer surface of the T90 section. Figure 33 presents the corresponding data for the T65 section. The maximum temperature differences between the core and outer surfaces of the web show a monotonic increase with the rising concrete placing temperature, while the rate of increase exhibits progressive attenuation under higher placing temperature conditions. For the five placing temperatures, the maximum temperature difference between the web core and outer surface of the T90 section varies from 25.8 to 29.5 °C, while that of the T65 section ranges from 18.0 to 19.9 °C. For every 5 °C increase in concrete placing temperature, the maximum temperature differences in the T90 section increase within a range of 0.3 to 1.9 °C, while the T65 section exhibits a smaller incremental range of 0.1 to 1.0 °C. Notably, the peak temperature difference consistently occurs at approximately 63 h for the five placing temperatures investigated, demonstrating that the placing temperature has minimal influence on the occurrence time of maximum temperature differences. During the critical initial 54 h period, higher concrete placing temperatures consistently generated greater temperature differences between the core and outer surface, with particularly accelerated development observed within the first 17 h. Considering the low tensile strength of early-age concrete and poor crack resistance in box girders, controlling the concrete placing temperature at appropriately lower levels is recommended as an essential measure to mitigate the surface cracking risks of box girders.

Figure 32.

The influence of placing temperature on the temperature differences between the web core and outer surface of the T90 section.

Figure 33.

The influence of placing temperature on the temperature differences between the web core and outer surface of the T65 section.

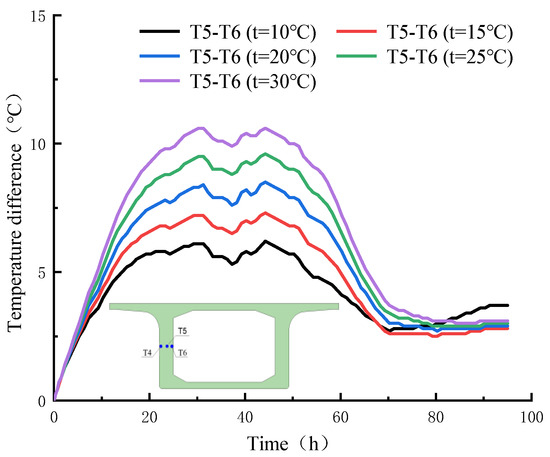

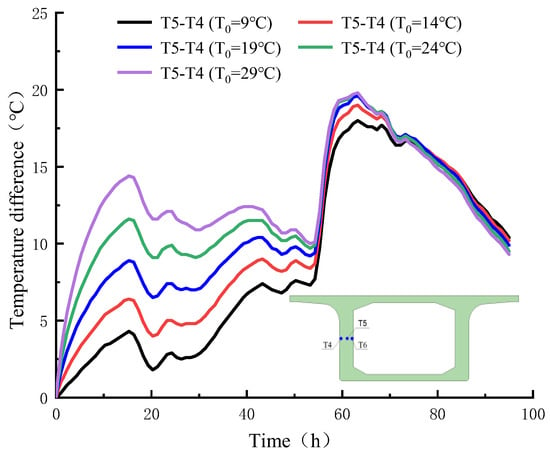

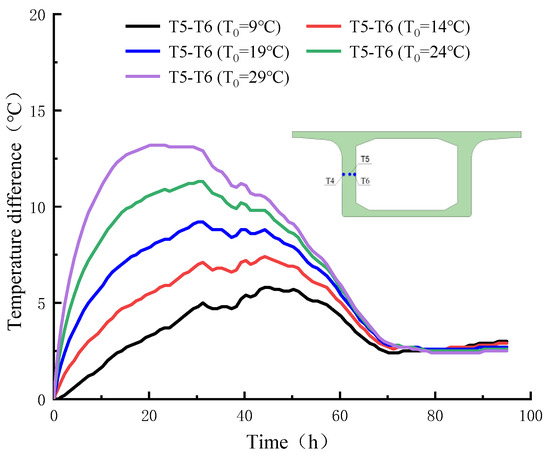

Figure 34 illustrates the temperature differences between the web core and inner surface in T90 sections, with corresponding data for T65 sections presented in Figure 35. For five placing temperatures, the web temperature difference exhibits consistent variation trends, demonstrating an initial increase followed by a subsequent decrease, with the peak differentials consistently occurring before 50 h. Notably, higher placing temperatures significantly enhance the temperature differences, ranging from 10.0 to 20.2 °C for the T90 section and 5.8 to 13.2 °C for the T65 section. A 5 °C increase in placement temperature elevates the temperature differences by 2.3–2.7 °C in the T90 section and 1.4–2.5 °C in the T65 section. Furthermore, as the placing temperature increases, the occurrence time of the maximum temperature difference exhibits a significant advancing trend. The temperature difference between the core and the inner surface rises at a notably faster rate before reaching its peak value, which is highly detrimental to crack suppression when the concrete strength of the box girder is relatively low. Particularly when the placing temperature exceeds 24 °C, the occurrence time of the maximum temperature difference advances to 30 h. At a placing temperature of 29 °C, this time further advances to 21 h. According to the prefabrication process of railway large-scale box girders, in situ prestressing tension construction typically cannot be performed until after 35 h. Consequently, to prevent excessive placing temperatures from inducing significant temperature differences in the box girder web before in situ prestressing tension, it is recommended that the placing temperature be controlled below 19 ℃.

Figure 34.

The influence of placing temperatures on the temperature differences between the web core and the inner surface of the T90 section.

Figure 35.

The influence of placing temperatures on the temperature differences between the web core and the inner surface of the T65 section.

Based on the aforementioned research findings, for the first construction of 60 m concrete box girders in China’s intercity railway, the following measures were implemented in the winter: thermal curing using insulation rooms, controlling the placing temperature below 19 °C, maintaining curing temperatures between 15 and 20 °C, and applying compressive stress reserves through prestressing pre-tensioning before approximately 54 h. A post-fabrication inspection reveals no visible thermal cracks in the prefabricated box girders. The implementation of these insulation measures reduces the winter occupation time of the casting bed from approximately 144 h to 96 h, thereby not only successfully improving girder production efficiency but also effectively preventing early-age cracking in the box girders.

5. Conclusions

Based on the thermal insulation construction of 60 m large-scale railway box girders in the winter, this paper conducts in situ temperature field monitoring and investigates the strength development patterns of concrete under various curing conditions. Building upon these experimental results, numerical simulations are carried out to analyze the influence of thermal insulation parameters, leading to the proposal of efficient thermal insulation strategies. The principal findings and conclusions are summarized as follows:

- (1).

- The peak hydration temperature is positively correlated with the local geometric dimensions of the box girder sections. High-temperature zones in the end sections are primarily concentrated in the webs, whereas in the T65 and midspan sections, these regions are predominantly located at the web and top-web junctions.

- (2).

- Thermal insulation with heating significantly accelerates concrete strength development and improves production efficiency of large-scale box girders in winter. Compared to natural curing conditions, insulated curing increases the temperature difference between the web core and inner surface while decreasing the temperature difference between the web core and outer surface during the early-age stage.

- (3).

- Increasing the insulation temperature elevates the peak temperature of box girders, and the section with thinner local dimensions exhibits greater thermal sensitivity. Before 54 h, higher insulation temperatures reduce the maximum temperature differences between the web core and outer surface, while conversely increasing the maximum temperature differences between the core and inner surface. To prevent concrete cracking on both the outer and inner surfaces of large-scale box girders, the recommended insulation temperature range during winter construction is 15–20 °C.

- (4).

- An elevated concrete placing temperature not only increases the peak temperature and maximum temperature differences in large-scale box girders but also induces an earlier occurrence and a more rapid growth of the maximum temperature difference between the web core and inner surface, thereby exacerbating the risk of early-age cracking when the concrete strength is low. To control the maximum temperature difference, it is recommended to maintain the concrete placing temperature below 19 °C during winter construction.

- (5).

- During the winter construction of the 60 m railway box girder, the concrete placing temperature and the curing temperature inside the insulation room are controlled according to the above recommended values. Furthermore, by applying preliminary prestressing tension before the 54 h mark to develop an adequate reserve of compressive stress in the large-scale box girder, production efficiency is successfully improved while effectively preventing the formation of early-age cracks.

Although the research conclusions are valuable and the accuracy of the numerical model has been verified, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the conclusions of this study are primarily derived from a specific large-scale railway box girder; special attention should be exercised when extrapolating these findings to scenarios with significant differences. Second, although variations in thermal parameters are considered in the numerical simulations, some key parameters, such as the hydration heat of cementitious materials and the heat-transfer coefficient, are obtained from empirical data in the literature. Direct testing of the relevant material properties would help further enhance the numerical model’s precision. Additionally, the removal of the insulation room and the steel formwork is uniformly assumed to occur at 54 h; in practice, this timing may be optimized according to specific thermal insulation strategies. Addressing these aspects could represent an important focus for future research, thereby improving the comprehensiveness of this investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Y., Z.Z., and L.W.; methodology, W.Y., T.Z., and L.W.; investigation, T.Z., X.F., L.W., and Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Y., Z.Z., and L.W.; project administration, W.Y., and F.W.; and funding acquisition, W.Y. and F.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of the Major Project of “Science and Technology Innovation 2025” in Ningbo (2019B10076). This financial support is gratefully acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Wei Yang, Tao Zhang, Zuqing Zhao, Xuebin Feng were employed by China Railway Construction Bridge Engineering Bureau Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zhu, J.S.; Wang, Z.Y. Experimental modeling and quantitative evaluation of mitigating cracks in early-age mass concrete by regulating heat transfer. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Zeng, Y.T.; Jiang, D.; Liu, S.H.; Tan, H.M.; Zhou, J.T. Curing parameters’ influences of early-age temperature field in concrete continuous rigid frame bridge. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.A.; Verdugo, D.; Tia, M.; Hoang, T.T. Effect of volume-to-surface area ratio and heat of hydration on early-age thermal behavior of precast concrete segmental box girders. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 28, 101448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Xiong, H.T.; Wang, R.M. Measurements and numerical simulations for cast temperature field and early-age thermal stress in zero blocks of high-strength concrete box girders. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2022, 14, 16878132221091514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Zhi, F.; Liu, J. Measurement and analysis of hydration heat of long span PC box girders. Bridge Constr. 2016, 46, 29–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, J.Y. Study on temperature distribution of three-cell box girder during the hydration process. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2023, 148, 2629–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taysi, N.; Abid, S. Temperature distributions and variations in concrete box-girder bridges: Experimental and finite element parametric studies. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2015, 18, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Liu, Y.J.; Lyu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, N. Numerical simulation investigation on hydration heat temperature and early cracking risk of concrete box girder in cold regions. J. Traffic Transp. Eng.-Engl. Ed. 2023, 10, 697–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.J.; Liu, J. In-situ test on hydration heat temperature of box girder based on array measurement. China Civ. Eng. J. 2019, 52, 76–86. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, S.R.; Xue, J.Q.; Liu, J.; Taysi, N.; Liu, Y.J.; Ozakça, M.; Briseghella, B. Temperatures and gradients in concrete bridges: Experimental, finite element analysis and design. Structures 2022, 37, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.H.; Ma, K.L.; Long, G.C.; Xie, Y.J. Mechanical properties evolution of concrete in steam-curing process. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 46, 1584–1592. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyad, A.M.; Tayeh, B.A.; Adesina, A.; Azevedo, A.R.G.; Amin, M.; Hadzima-Nyarko, M.; Agwa, I.S. Review on effect of steam curing on behavior of concrete. Clean. Mater. 2022, 3, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.; Chang, H.J.; Wang, F.; Cai, Y.L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Lv, Z.D. Effect of steam curing scheme on the early-age temperature field of a prefabricated concrete T-beam. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.L.; Gao, S.B.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, B.H. Early hydration heat temperature field of precast concrete T-beam under steam curing: Experiment and simulation. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, A.S.; Kearsley, E.P.; Kolomatskiy, A.S.; Mostert, H.F. Heat evolution due to cement hydration in foamed concrete. Mag. Concr. Res. 2010, 62, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbia, L.A.; Peyvandi, A.; Harsini, I.; Lu, J.; Ul Abideen, S.; Weerasiri, R.R.; Balachandra, A.M.; Soroushian, P. Study on field thermal curing of ultra-high-performance concrete employing heat of hydration. ACI Mater. J. 2018, 114, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Bautista, E.; Bentz, D.P.; Sandoval-Torres, S.; Cano-Barrita, J. Numerical simulation of heat and mass transport during hydration of Portland cement mortar in semi-adiabatic and steam curing conditions. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 69, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, A.I. Thermal properties of sand modified resins used for bonding CFRP to concrete substrates. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2016, 5, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhi, G.; Wang, K.J. Influence of cement fineness and water-to-cement ratio on mortar early-age heat of hydration and set times. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 50, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shi, M.X.; Wang, D.Q. Contributions of fly ash and ground granulated blast-furnace slag to the early hydration heat of composite binder at different curing temperatures. Adv. Cem. Res. 2016, 28, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.K.; Lu, X.C.; Xiong, B.B.; Chen, B.F.; Tian, B.; Chen, H.J.; Li, Y.Q. Study on the influence of temperature rise inhibitor on the early-age temperature field of moderate heat Portland cement (MHC) concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.M.; Kim, C.Y.; Yeon, J.H. Heat of hydration and mechanical properties of mass concrete with high-volume GGBFS replacements. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018, 132, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.; Noruzman, A.H.; Bhutta, M.A.R.; Yusuf, T.O.; Ogiri, I.H. Effect of vinyl acetate effluent in reducing heat of hydration of concrete. Ksce. J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.H.; Moon, G.D.; Jeon, Y.S. Implementing ternary supplementary cementing binder for reduction of the heat of hydration of concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassr, A.; Abd-el-Rahim, H.H.A.; Kaiser, F.; El-sokkary, A. Topology optimization of horizontally curved box girder diaphragms. Eng. Struct. 2022, 256, 113959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.Y.; Cai, J.B.; Feng, Q.; Jia, W.Z.; He, Y.C. Experimental study and numerical analysis of hydration heat effect on precast prestressed concrete box girder. Building 2025, 15, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- Zhu, B.F. Thermal Stresses and Temperature Control of Mass Concrete, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, T.L.; Incropera, F.P. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 7th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, P.F.; Pedersen, E.J. Maturity computer for controlled curing and hardening of concrete. Nordisk Betong. 1977, 1, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Schindler, A.K. Concrete Hydration, Temperature Development, and Setting at Early Ages; The University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Van Breugel, K. Simulation of Hydration and Formation of Structure in Hardening Cement-Based Materials; Delft University Press: Delft, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, B.F. Temperature Stresses and Temperature Control in Mass Concrete, 2nd ed.; China Water Conservancy and Hydropower Press: Beijing, China, 2012. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).