Abstract

Although public service motivation (PSM) has been extensively studied for decades, its theoretical pathways to job satisfaction (JS)—a central determinant of public institution performance—remain insufficiently articulated. This study fills this theoretical gap by proposing a dual-path mediation model wherein person–organization fit (PO-fit) and perceived accountability jointly elucidate how PSM enhances JS. Drawing on survey data from 1098 employees of the Taiwan Railways Administration, a public utility undergoing institutional reform, the study employs partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to test our model. The results indicate that three dimensions of PSM—attraction to public service, commitment to public values, and compassion—positively affect JS through both direct and indirect pathways. PO-fit fosters value congruence between employees and organizations, while perceived accountability strengthens moral responsibility and intrinsic fulfillment. Theoretically, the study advances PSM research by integrating value alignment and accountability mechanisms into a unified motivational framework. Practically, it offers guidance for human resource strategies that cultivate a motivated, satisfied, and accountable workforce—an essential condition for achieving SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions).

1. Introduction

For decades, public service motivation (PSM) has stood at the heart of efforts to explain the values, attitudes, and behaviors that characterize public employees. Scholars consistently find that individuals with higher PSM levels report greater job satisfaction (JS) and more substantial affective commitment to public organizations [1,2,3]. Yet, despite decades of inquiry, the mechanisms through which PSM translates into job satisfaction remain ambiguous. Prior studies have suggested that PSM may shape job attitudes through psychological alignment, value congruence, or work environment conditions [4,5], but the causal pathways are far from settled [6]. This persistent uncertainty highlights an enduring theoretical gap in our understanding of how and why PSM enhances satisfaction in the complex institutional settings of public organizations.

One particularly overlooked mechanism concerns perceived accountability—the extent to which employees internalize standards of responsibility and feel answerable for their actions. As Brewer notes [7], accountability and performance are twin imperatives in public administration that often coexist in tension. Public employees, particularly in heavily scrutinized public utilities, operate under constant pressure to be both responsive and responsible. Yet lapses in accountability remain frequent, leading to declines in trust, morale, and retention [8,9]. Although institutional accountability has received considerable attention, individual-level perceived accountability remains theoretically underdeveloped [10,11]. Specifically, scholars have yet to explain how employees internalize accountability norms and experience them as intrinsic motivational forces [12], or how such perceptions interact with PSM to shape job satisfaction.

Building on this theoretical gap, this study positions perceived accountability as a key motivational linkage between PSM and JS. Accountability, when internalized, may reinforce employees’ sense of moral obligation and prosocial purpose, thereby amplifying the satisfaction derived from public service work [13]. Conversely, accountability experienced as external control may undermine intrinsic motivation. Understanding this dual nature is therefore essential for reconciling the accountability–performance paradox in public management theory.

Furthermore, we argue that context is crucial. The Taiwan Railways Administration (TRA), a major public utility undergoing prolonged reform and operational stress, provides an ideal empirical setting for this investigation. The TRA faces high employee turnover, wage disputes, and work overload [14], conditions that test the resilience of PSM and the salience of perceived accountability. By examining these dynamics within a utility context, this study contributes to ongoing debates about how public servants sustain motivation and satisfaction amid pressures for bureaucratic reform [15,16].

Accordingly, this research aims to clarify the mechanisms through which PSM influences job satisfaction in public organizations, to investigate the mediating role of perceived accountability in this relationship, and to generate empirical insights from the TRA case that extend theoretical understanding of motivation, accountability, and satisfaction within public utilities.

By addressing these aims, the study not only advances PSM theory by incorporating perceived accountability into the motivational framework but also offers actionable implications for managing, motivating, and retaining a high-performing public workforce. Ultimately, the findings contribute to the broader pursuit of sustainable and accountable public institutions consistent with SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions).

2. Literature Review

PSM is defined as “an individual’s predisposition to respond to motives grounded primarily or uniquely in public institutions and organisations” (p. 368, [17]) and has been positively correlated with job satisfaction [18,19,20]. Job satisfaction is a perceived behavior for organizations that makes a person want to come to work. Locke [21] defined job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction as “a function of the perceived relationship between what one wants from one’s job and what one perceives it as offering or entailing” (p. 316). JS is widely regarded as a key correlate of PSM, as public employees derive satisfaction from advancing public values and contributing to society [22].

Although the link between PSM and JS appears across both public and private organizations, studies indicate that public employees are uniquely driven by a sense of “special calling” inherent in serving the public interest [17]. JS is among the most extensively studied constructs in organizational behavior, owing to its critical role in shaping organizational performance. Taylor [20] realized that public workers who believe their work benefits the public are most content and inspired. The commitment to public values (CPV) component was more strongly connected with JS than self-sacrifice (SS) or attraction to public service (APS). CPV increases employees’ job satisfaction significantly [23]. Homberg, McCarthy, and Tabvuma [24] recommended that managers prioritize SS and CPV while using PSM to boost job satisfaction in their organizational components. Furthermore, Giauque, Ritz, Varone, and Anderfuhren-Biget [25] found that the compassion (COM) and SS aspects of PSM enhance public servant job anxiety and desertion. In addition, Anderfuhren-Biget, Varon, and Giauque [26] found elevated COM among welfare state policymakers. Based on the foregoing discussion, the following research hypotheses are proposed.

H1 (w):

Self-sacrifice (SS) has a positive relationship with Job satisfaction.

H1 (x):

Attraction to public service (APS) has a positive relationship with Job satisfaction.

H1 (y):

Commitment to public values (CPV) has a positive relationship with Job satisfaction.

H1 (z):

Compassion (COM) has a positive relationship with Job satisfaction.

2.1. Mediating Role of Person–Organization Fit

The Person–Organization Fit (PO-fit) is defined as the compatibility of people and organizations [27]. Inspired by the PO-fit literature, scholars have found that PSM has a beneficial impact on work attitudes indirectly via its effects on PO-fit [28,29]. To that end, it is necessary to delineate the linkages between PSM and JS when PO-fit appears concurrently. PO-fit theory defines complementing concordance as an organization’s resources and activities meeting workers’ significant unmet needs.

PSM and PO-fit increase JS. According to PO-fit theory, additional alignment is obtained when organizations hire people with comparable objectives and values [30]. Values constitute a critical aspect of person–organization fit (PO-fit), given that public values are foundational and relatively stable, serving as a core element of public service culture that influences employee behavior [31]. Public employees have significant needs and motivations, and public services/policies either meet or do not meet those needs and motivations. Public employees are likely to have values and motives oriented towards altruistic and pro-social behavior. Public utilities can offer employees a unique opportunity to meet their needs while also contributing to the improvement of public service. Taylor’s [32] results confirm PO-fit’s supplemental concordance that contented public workers regard their work as serving the public interest. In other words, PO-fit is a consistent predictor of an employee’s job satisfaction.

Studies conducted in the Netherlands [33], the United States [28,29], and South Korea [1,34] consistently show that the link between PSM and JS is indirect, operating through PO-fit. JS depends mainly on the alignment between employees’ personal values and their organizational context. Wright and Pandey [29] emphasized that such value congruence mediates the PSM–JS relationship, explaining why individuals with higher PSM levels tend to report greater satisfaction in their roles.

These arguments lead us to propose that dimensions of PSM have more opportunities to grow where they perceive high PO-fit in the work environment. The high level of PO-fit in the workplace also indicates the possibility of great job satisfaction. The dimensions of PSM heighten employees’ sensitivity to opportunities for meaningful contribution, making them more likely to experience JS as they pursue and achieve their goals. As such, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2 (w):

PO fit mediates the relationship between SS and job satisfaction.

H2 (x):

PO fit mediates the relationship between APS and job satisfaction.

H2 (y):

PO fit mediates the relationship between CPV and job satisfaction.

H2 (z):

PO fit mediates the relationship between COM and job satisfaction.

2.2. Mediating Role of Perceived Accountability

Accountability in the public sector is a multifaceted concept. As a foundational principle of public administration [35], accountability serves as the mechanism that sustains institutional functioning. Public employees are accountable to the public, employers, the government, and themselves [11,36]. Accountability has been suggested as the most fundamental factor influencing employees’ behavior, particularly their performance, in the public sector [37]. Accountability has an influence on employees’ behavior by affecting both what motivates employees and how they think [12]. It has been suggested that when employees feel obligated to explain their behavior, their perceived accountability increases.

According to Locke’s [21] goal-setting theory, public employees tend to work more when they are involved in decision-making and goal-setting processes. As a result, it is claimed that employee perceptions of accountability are a consequence of numerous complex external and internal factors, rather than occurring in isolation. These variables combine in unique ways to influence how employees experience accountability in their workplace. Using this reasoning, it can be argued that perceived accountability is influenced by the interaction between the employee and the organization. Therefore, changes in this interaction can lead to changes in perceived accountability and desired attitudes and work outcomes.

Perceived accountability is conceptually related to JS through their shared motivational underpinnings. Although several studies have reported a positive association between PSM and JS [1,28,29], other evidence suggests that PSM does not uniformly enhance work attitudes and behaviors across all public organizations [38]. A promising line of inquiry that may help explain this inconsistency concerns the role of perceived accountability [12]. Accountability affects organizational characteristics, including motivation and performance. The absence of accountability mechanisms further exacerbates unlawful conduct [39].

Unlike institutional accountability, which emphasizes compliance with external rules and formal sanctions, perceived accountability captures the individual’s internalized sense of answerability and moral obligation [11,40]. When employees view accountability as an intrinsic value rather than external control, it strengthens their psychological engagement and amplifies the satisfaction derived from public service [3,41].

Facing a more strict administrative structure, measured by the need to obtain public policy approval, may improve PSM and all other dimensions. Public interest, democracy, social equality, impartiality, and accountability are public ideals [10]. These public values may have significant implications for how accountability is perceived. In public utilities, a stricter administrative structure encourages public service. Decision-making and public service motivate workers. SS and perceived responsibility reduce the individuality of public utility workers.

Although perceived accountability may seem to be the same, it is more than just a set of external requirements that all employees view in the same manner. Several factors influence work outcomes, including a balance between employees and their surrounding environment, which encompasses individuals, resources, motivation, and feedback [42]. Perceived accountability can influence work outcomes in both positive and negative ways, depending on the characteristics of the work environment [13]. Perceived responsibility is the expectation that workers must inform, explain, and/or justify their performance to superiors. More to the point, perceived accountability impacts employees’ behaviors and decisions, especially in the context of administrative reforms in public utilities.

Perceived accountability as a sound control system and public scrutiny, a common approach in the public sector, may act as an information processing theory, shedding ample light on how employees gather vital information about attitudes, beliefs, and expectations from their environment and adjust their attitudes and behavior accordingly [43]. Public workers must have PSM and JS, as public utilities involve clients in the service product manufacturing process. Public personnel seeking accountability may be sorted throughout their job search. Public personnel connect their perceived accountability and workplace conditions to their inherent motivation [44]. The presence of perceived accountability for task accomplishment is likely to enhance JS. The perception of a high degree of accountability spurs PSM to enhance JS, as these employees consider it may put them in a positive situation. Academics should examine the role of accountability in PSM and its consequences, as it affects both positive and negative individual and organizational outcomes. However, research on individual accountability is still in its infancy. Although accountability has been praised for its benefits to employees and organizations, the outcomes are not always positive. According to research, accountability in public sectors has been linked to adverse individual outcomes [8]. These findings will help academics better understand the role of perceived responsibility in public utilities. The primary contribution of this study is considering perceived accountability as a mediator, a concept that researchers have not previously studied. Based on the foregoing discussion, the following hypothesis is advanced.

H3 (w):

Perceived accountability mediates the relationship between APS and job satisfaction.

H3 (x):

Perceived accountability mediates the relationship between CPV and job satisfaction.

H3 (y):

Perceived accountability mediates the relationship between COM and job satisfaction.

H3 (z):

Perceived accountability mediates the relationship between SS and job satisfaction.

3. Methodology

In January 2017, employees of the Taiwan Railway Administration (TRA) staged protests at major railway stations in Taipei and Kaohsiung to raise public awareness of their excessive workloads and deteriorating working conditions. The protesters alleged that TRA officials routinely compelled frontline staff to work overtime during critical holiday periods, such as the Lunar New Year, thereby intensifying burnout and dissatisfaction among employees. The accumulation of occupational stress and perceived managerial injustice not only eroded staff morale and performance but also jeopardized passenger and transportation safety. Moreover, the harsh working conditions constituted a violation of fundamental labor rights, according to a report in the Taipei Times on 28 January 2017.

Institutionally, the TRA operates as a government department rather than a state-owned enterprise with a board of directors, thereby subjecting it to a rigid bureaucratic hierarchy. Until 1998, the TRA was directly supervised by the Department of Transport under the Taiwan Provincial Government. After decades of persistent financial deficits, the government initiated a comprehensive reform aimed at complete privatization by June 2001. Consequently, the TRA was required to adhere to the same supervisory procedures as other government-owned enterprises (GOEs) while remaining under the administrative oversight of several central government agencies, which further constrained its managerial autonomy. Among the most formidable challenges to the privatization reform was resolving the TRA’s substantial debt burden. In addition, the TRA’s wage settlements tended to exceed those of comparable institutions, exacerbating fiscal pressures. Furthermore, trade unions representing public enterprises in Taiwan—bolstered by post-legislative empowerment—became increasingly well-organized and politically influential, adding another layer of complexity to institutional reform efforts.

Disillusioned by the structural and managerial constraints of public enterprises, burdened by expanding responsibilities, and deprived of adequate administrative and collaborative support, TRA employees increasingly express intentions to leave public service for alternative careers. Such disillusionment and job dissatisfaction inevitably erode employees’ intrinsic motivation, leading to a decline in overall job satisfaction (JS). Inherent factors—including personal perceptions of performance, meaningful interaction with the public, and fulfillment derived from serving the public interest—are critical determinants of both motivation and JS among public servants [45]. Conversely, extrinsic factors such as age, education level, gender, marital status, administrative workload, additional responsibilities, and perceived managerial support also shape the level of motivation and JS within government-owned enterprises [46].

Frequent employee turnover within the GOE sector undermines institutional continuity and teamwork, thereby weakening the organization’s capacity to achieve strategic objectives [47]. Persistent challenges in retaining qualified personnel further diminish public trust, weaken relational ties between citizens and public enterprises, and impair the overall performance of public service delivery. In the long run, inadequate retention not only lowers employee morale but also threatens the normative foundations of PSM and the pursuit of the public values [14].

Politicians and managers alike have put pressure on the Taiwan Railway Administration over the last three decades to remedy alleged management inefficiencies. Advocates of TRA reform argue that the most effective way to enhance conventional government procedures is to leverage the power of market-oriented mechanisms. Since conventional government service operations have historically been both privatized and corporatized, market-oriented initiatives have often followed this pattern. Furthermore, advocates argue that increased management control fosters legitimacy by enhancing responsibility to the public. The suggested solutions contributed to a rethinking of both the delivery of public services and the broader principles underpinning governance.

TRA workers whose motivations were inspired by the intention to promote the public welfare were likely to be fulfilled with their careers, as government service gives abundant potential to offer public goods and serve the public’s interests [20]. Data were collected from TRA employees using a random sampling method. All respondents were members of their respective organizational units. For authorization, researchers approached the HR offices of these units. The relevant departments received an official letter outlining the study’s purpose, assurances of confidentiality, and the voluntary nature of participation. The HR departments of the units allowed approval for investigators to have real interaction with their workers. They also announced the introduction of the study and promised all individuals their anonymity and willingness to participate. More significantly, they assured employees that their opinions would not be shared with their superiors or organizations. All employees participated in the study in the meeting room of each unit. In accordance with the procedures outlined by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff [48], the investigators clarified the intent of the survey, stating that there were no rights or wrongs. They also emphasized that participants should convey their responses as impartially as possible to minimize method biases.

Additionally, this study employed a two-wave data collection design to reduce potential common method variance, with a four-week interval between waves. At Time 1, participants completed measures of PSM and perceived accountability, and at Time 2, they completed measures of PO-fit and job satisfaction. A four-week interval was implemented between data collections to minimize potential common method bias [49]. ANOVA studies were used to determine whether there is internal heterogeneity among temporal groupings (i.e., time points 1 and 2). The findings revealed no significant variations in age or gender among respondents at time points 1 and 2, nor among respondents who responded to the investigation at time point 2 and workers who did the investigation at time point 1. Our study involved 1123 people at Time 1 (74.8% response rate) and 1098 people at Time 2 (73.2% response rate). During Time 1, participants responded to items assessing PSM and PA. At Time 2, approximately four months later, all participants reported on PO fit and JS.

3.1. Measures

3.1.1. Public Service Motivation (PSM)

PSM was measured using Kim et al.’s 16-item instrument [34], adapted to a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). Internal consistency was high, with Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.81 (APS), 0.82 (CPV), 0.80 (COM), 0.78 (SS), and 0.90 for the overall PSM scale. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) revealed a satisfactory model fit for the whole 16-item measure (χ2 = 480.2 (96), RMSEA = 0.074, CFI = 0.924, and SRMR = 0.037). Sample items are: “I admire people who initiate or are involved in activities to aid my community”, and “I am prepared to make sacrifices for the good of society”. Higher scores indicated stronger levels of PSM, suggesting that participants exhibited greater motivation toward JS.

3.1.2. Job Satisfaction (JS)

We measured JS using five items from the Bono and Judge’s [50] scale. It has been used in a past study [50]. Sample items for job satisfaction are: “Most days I am enthusiastic about my work” and “I consider my job rather unpleasant”. The last two items are reverse-scored. Participants provided their responses on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“completely disagree”) to 5 (“completely agree”). The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.86.

3.1.3. Perceived Accountability (PA)

Following the scale of Mero, Guidice, and Werner [51], we used a three-item scale to measure PA. Sample items include: “I am required to justify or explain my performance regarding achieving the task”, and “Others in my organisation can observe the outcome of my work performance in terms of helping and cooperating with colleagues.” Participants responded using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“completely disagree”) to 5 (“completely agree”). The scale demonstrated good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87.

3.1.4. Person–Organization Fit (PO-Fit)

PO-fit was assessed with a three-item scale adapted from Cable and DeRue [52]. Sample items are: “The things that I value in life are very close to the things that my organisation values”, “My personal values match my organisation’s values and culture”, and “My organisation’s values and culture provide a good fit with the things that I value in life”. Participants responded using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“completely disagree”) to 5 (“completely agree”). The scale demonstrated good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88.

The measurement items were translated into Mandarin using a back-translation procedure to ensure conceptual equivalence, and a pilot test with 50 TRA employees confirmed clarity and comprehension. The measurement items were translated into Mandarin using a back-translation procedure to ensure conceptual equivalence, and a pilot test with 50 TRA employees confirmed clarity and comprehension. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed to analyze the relationships between selected constructs, chosen for several methodological reasons [53].

Initially, it is worth noting that PLS-SEM demonstrates superior statistical power and exhibits greater resilience in terms of identification complications compared to CB-SEM. Furthermore, PLS-SEM is particularly suitable for this investigation, as the primary aim of the survey is to identify essential driver constructs [54].

Third, the research framework exhibits complexity in the relationships among hypotheses (multi-mediation effect), thus rendering PLS-SEM suitable for an intricate model [55]. Fourth, PLS-SEM proves to be the most advantageous analytical approach for this study, given its ability to generate latent variable scores for further analyses, as recommended by Hair, Hult, Ringle, and Sarstedt [56]. Finally, PLS-SEM is suitable when the measurement model has few indicators (i.e., <6); in this research, most of the constructs have fewer indicators (i.e., <6) [57].

4. Analysis

In line with Henseler, Hubona, and Ray [58], the analysis confirmed that the measurement model met all required standards of model fit. Reflective outer loadings were all above the acceptable level of 0.70, except for the self-sacrifice (SS) dimension (0.45). Therefore, we deleted the SS dimension of PSM. In line with [56] the structural model was examined using a five-step analytical process. The analytical procedure consisted of five phases: Phase 1 identified possible collinearity issues within the structural model; Phase 2 assessed the strength and significance of the hypothesized relationships; Phase 3 evaluated the explanatory power of the model (R2); Phase 4 measured the effect size (f2); and Phase 5 examined the model’s predictive relevance (Q2).

Descriptive statistics, reliability estimates, and intercorrelations among the study variables are displayed in Table 1. All correlations are positive and significant in the expected directions, indicating that higher levels of PSM are associated with greater person–organization fit, stronger perceived accountability, and higher job satisfaction.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations (N = 1098).

Firstly, the study assessed all predictor constructs in the structural model to detect multicollinearity. The tolerance (i.e., VIF) value for each predictor construct was less than 5, indicating that collinearity within the set of predictor constructs specified in the structural model is not a concern.

Secondly, using 5000 randomly chosen samples with replacement at the 0.05% level of significance, this study employed the bootstrapping technique [56]. Furthermore, the bootstrapping procedure computed not only standard errors but also bootstrapping confidence intervals for standardized regression coefficients [55]. The magnitude and sign of path coefficients were investigated in this research. Table 2 shows the path coefficient values alongside the 95% confidence interval bootstrap percentiles.

Table 2.

Effects on endogenous variables.

Thirdly, adhering to conventional guidelines, the R2 values for PO fit (0.537), PA (0.375), and JS (0.796) were classified as moderate, weak, and substantial, respectively [56].

Fourthly, to aid in interpreting R2, the f2 effect size was determined. Table 2 outlines the standard benchmarks for f2, where values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 indicate small, medium, and significant effects of an exogenous construct on an endogenous construct, respectively. It is crucial to acknowledge that a small f2 does not necessarily indicate a minimal impact.

Finally, a blindfolding process was used in the study to provide cross-validated duplication measures for each endogenous variable. As indicated in Table 2, Q2 values greater than zero confirm that the structural model possesses sufficient predictive relevance for the endogenous construct.

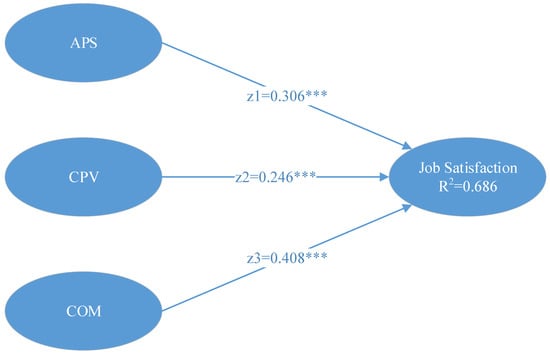

The hypothesis testing results confirmed a positive and significant association between PSM and JS, consistent with expectations. The combined effect (z1, z2, and z3) of APS, CPV, and COM on JS is illustrated in Figure 1 and summarized in Table 3. The findings confirm H1-x, H1-y, and H1-z, which illustrate a direct association amongst PSM (i.e., APS, CPV, and COM) and JS in this circumstance (z1 = 0.306; t = 8.768, z2 = 0.246; t = 6.444, and z3 = 0.408; t = 8.801, respectively).

Figure 1.

Total effect model. Note: *** p < 0.001 (two-tailed test).

Table 3.

Results of Mediation Analyses.

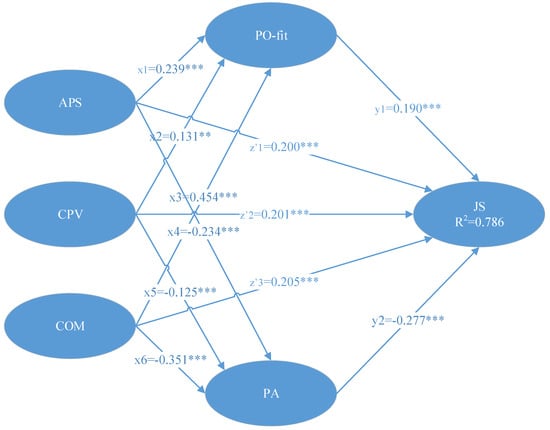

For the mediation analysis, this study followed the recent methodological approach to test the mediation hypotheses (H2-x, H2-y, H2-z and H3-x, H3-y, H3-z) [55]. First, as shown in Table 2, the study examined the direct consequences of independent factors on mediations and the impact of mediations on the dependent variable. The results show that x1, x2, x3, x4, x5, x6, y1, and y2 are significant as direct effects of PSM on PO fit, PSM on PA, PO fit on JS, and PA on JS. It meets the requirement for determining whether an indirect effect exists.

The survey’s second stage involved assessing the mediator’s significance using the non-parametric bootstrapping method [53,55,57]. For the mediators, 5000 resamples were used to produce 95 percent confidence intervals (percentile). APS, CPV, and COM all showed a significant total influence on JS, as shown in Table 3 and Figure 1 (z1 = 0.306, t = 8.768; z2 = 0.246, t = 6.444; and z3 = 0.408, t = 8.801, respectively).

Accordingly, by adding the mediators (Figure 2), APS, CPV, and COM decrease their influence, but maintain a significant direct effect on JS (H1-x: z’1 = 0.200; t = 4.801, H1-y: z’2 = 0.201; t = 4.667, and H3-z: z’3 = 0.205; t = 3.917, respectively). As shown in Table 3, the confidence interval for the mediation effect (product) does not yet have a zero value [57]. As a result, these findings support H2-x, H2-y, H2-z, H3-x, H3-y, and H3-z. According to these results, the indirect effects of APS, CPV, and COM on JS in the present research are significant. The entire impact of APS, CPV, and COM on JS is represented in Figure 2 as the aggregate of the direct (z′1, z′2, and z′3) and indirect effects (x1y1 + x4y2, x2y1 + x5y2, x3y1 + x6y2). The indirect effects were assessed by multiplying each path’s coefficients, while the third stage of the study evaluated the quality and intensity of mediation.

Figure 2.

A multiple mediation model. Note: ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001 (two-tailed test).

Within the framework of this investigation, both direct (z′1, z′2, z′3) and indirect (x1y1, x2y1, x3y1, x4y2, x5y2, and x6y2) influences are significant, and products of x1y1 z′1, x2y1 z′2, x3y1 z′3, x4y2 z′1, x5y2 z′2, and x6y2 z′. In this scenario, PO fit and PA act as complementary mediators between PSM and JS. A type of partial mediation is complementary mediation [55]. In other words, a fraction of PSM’s consequences (APS, CPV, and COM) are mediated through PO fit and PA, whereas all three dimensions still account for a segment of PSM that is independent of PO fit and PA. In addition, the research calculated variance accounted for (VAF) to assess the strength of a partial mediation [53]. The rule of thumb is that, if the VAF is less than 20%, greater than 20% but less than 80%, or greater than 80%, it implies that there was no mediation, partial mediation, or full mediation, as shown in Table 3.

To assess the relative strength of the mediating effects (i.e., whether PO-fit has a more substantial effect than PA), we calculate the differences between x1y1 and x4y2, between x2y1 and x5y2, and between x3y1 and x6y2, using the examination principle recommended by Cepeda-Carrión, Nitzl, and Roldán [59]. Statistical results are presented in Table 4, along with percentile and bias-corrected confidence intervals. As illustrated in Table 4, the effects between M1 and M4, M2 and M5, and M3 and M6 exhibit no significant differences (i.e., the confidence intervals across all three scenarios were zero). Consequently, we can infer that person–organization fit does not exert a more pronounced effect than PA.

Table 4.

Comparison of mediations.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study extends the literature on PSM within organizational research by providing a more in-depth analysis of JS. The study examines the association among PSM, PO-fit, PA, and JS. This relationship contributes to the person–organization fit theory by positioning PSM as a principal antecedent of job satisfaction, while PO-fit and perceived accountability serve as mediating roles between PSM and job satisfaction. The validated model offers a micro-foundational perspective on sustainable institutional performance, demonstrating how human resource dynamics underpin the resilience of critical infrastructure. The statistical results present ample support for key hypotheses—namely, that PSM leads to a higher level of JS. Moreover, PO-fit and PA mediate the linkage between PSM and JS.

Our empirical results on the direct effect of PSM on JS indicate a significant positive association between attraction to public service (APS) and JS, which is consistent with the finding of Liu, Tang, & Yang [60]. It can be argued that APS is rooted in Chinese culture because accessing public policymaking is an assertion of power and traditionalism that typifies Chinese culture [61]. The significant positive linkage between CPV and JS is consistent with the results from previous studies [20,62,63]. The study also investigates a significant positive association of COM with job satisfaction, which supports previous findings [20]. The results of the model with only the total effect (Figure 1) show that the greater the presence of PSM, the greater the organization’s experience of job satisfaction.

The self-sacrifice (SS) dimension of PSM was excluded from the model due to a low outer loading (0.45). This empirical decision followed the recommended cut-off criteria of Hair et al. [56] to preserve model validity. However, the low loading of SS may also carry cultural implications. In East Asian contexts, particularly Taiwan, self-sacrifice is often interpreted as a collective moral norm rather than an individual distinction [61]. Public employees may therefore perceive altruistic behavior as inherently integrated into commitment to public values or compassion, rather than as a separate motive. This contextual interpretation suggests that while self-sacrifice remains conceptually relevant to PSM, its salience as an independent factor may vary by cultural setting.

Second, as expected, our results support the first part of the mediation relationships, from PSM to PO-fit. This finding suggests that individuals with high levels of PSM perceive a stronger PO-fit within public utilities. This finding is consistent with previous studies [28,32], which predict that PO-fit plays an important part in PSM when employees’ unmet salient needs are satisfied by the resources and jobs offered by an organization. Similarly, the current study finds support for the direct link between PSM and PA. The negative significance indicates that PSM controls their dominant behavior when they perceive high accountability. This result aligns with the perspective of Kim and Vandenabeele [62], who argue that PSM fosters a high level of tolerance for public value when individuals perceive a high degree of accountability in public utilities. Public employees inherently operate in a ‘web of accountabilities’ [12,64], where employees must simultaneously fill numerous positions and be accountable to a variety of different stakeholders [65]. Consequently, employees may experience both role conflict and role overload [40]. Prioritizing accountabilities and balancing multiple responsibilities can be stressful when working with several stakeholders. Workers’ responsibility levels vary by the source of accountability [12]. For instance, a worker may wish to provide good public service yet feel more responsible to a supervisor, who controls organizational incentives and sanctions.

The second half of the mediating relationship from PO-fit to job satisfaction implies that higher PO-fit predicts more JS. These insights are consistent with Bright [20] and Taylor [32], who asserted that the theory of PO-fit explains the influence of PSM dimensions on JS. In the same way, the findings support the negative link between PA and JS. This result contrasts with prior research suggesting that elevated levels of PA diminish JS [66]. Performance issues, on the other hand, often create accountability concerns and may lead to the adoption of more stringent accountability standards [7]. The issue of “who is accountable to whom and for what” [10] becomes more complicated in these new relationships. The concept of public accountability has evolved from being confined to vertical, hierarchical relationships to encompassing horizontal forms of accountability, where market mechanisms and financial performance indicators play a central role [67,68]. Accountability scholars have yet to examine perceived accountability as a potential stressor, and some have suggested that it may impair decision quality [69]. Furthermore, perceived accountability has been associated with adverse work outcomes. These studies demonstrate that the ‘purpose justifies the means’ principle may lead public workers to engage in unethical or dangerous behavior. Accountability mechanisms, such as the accountability environment, appear to influence perceived accountability despite their dysfunctional effects.

The present study makes a meaningful contribution to the existing literature by responding to calls for empirical research that examines the roles of PO-fit and PA in the relationship between PSM and JS. As hypothesized, both PO-fit and perceived accountability were found to mediate the association between PSM and job satisfaction. Although PSM as a research topic is attracting tremendous attention in the literature of public management [34,70], the link between PSM and JS in public enterprises remains underexplored and theoretically immature. This maturation is crucial, as the findings demonstrate that nurturing motivated and satisfied employees through these mechanisms is fundamental to building the effective, accountable, and transparent institutions outlined in Sustainable Development Goal 16, while also supporting the development of resilient infrastructure as targeted by SDG 9. Regarding managerial implications, the results of PO-fit indicated that managers in public utilities should be very sensitive regarding the general PO-fit. The presence of a high level of PO-fit ignites the PSM to exhibit positive behavior. Open-ended interviews, job security, a valuable public service, the opportunity to support others, a job that benefits society, flexible working hours, and regular training for fostering public values in the workplace are some ways to promote beneficial behaviors [1]. These practices are not merely operational tools but strategic investments in human capital that align directly with the pursuit of sustainable development, ensuring that public utilities can attract and retain talent committed to long-term societal goals. As far as perceived accountability is concerned, appropriate job standards, accountability in achieving productivity goals, and efficient public management systems can create a high level of perceived accountability among PSM, which likely helps them exhibit job satisfaction [62]. Fostering such an accountability culture is instrumental in achieving Target 16.6 of SDG 16, as it builds transparency and trust from within the organization. These strategies may lead public utilities’ employees to engage in favorable behaviors and reduce the possibilities of the dark side of PSMs.

This study advances the understanding of how PSM fosters JS among public employees by identifying two essential mediating mechanisms: PO-Fit and PA. Using data from 1098 employees of the Taiwan Railways Administration, the findings reveal that PSM enhances JS both directly and indirectly by aligning personal motives with organizational values and by shaping a constructive sense of responsibility.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The results contribute to the refinement of PSM theory by unpacking the psychological and institutional processes that translate motivation into satisfaction. Previous studies have largely treated PSM as a direct antecedent of job attitudes [6]; however, this research demonstrates that its effects unfold through dual pathways that integrate value congruence and responsibility internalization. The identification of PO-Fit as a mediating mechanism reinforces insights from Person–Environment Fit theory, emphasizing that satisfaction arises when individuals perceive alignment between their prosocial motives and organizational missions [71,72,73].

During measurement model testing, all reflective outer loadings exceeded 0.70 except for the self-sacrifice (SS) dimension (0.45). Following established SEM guidelines [54,56], SS was excluded to ensure construct reliability. This exclusion does not undermine theoretical integrity, as prior studies have similarly found SS to load weakly in collectivist cultures [34,61].

Moreover, by positioning perceived accountability as a positive motivational mechanism, this research questions the conventional understanding of accountability as solely a control-oriented mechanism. Consistent with recent work [3,41], we demonstrate that when accountability is perceived as moral and empowering, it enhances the intrinsic rewards of public service. Thus, accountability can serve as an enabling condition that sustains motivation and job satisfaction rather than constraining it.

Contrary to the hypothesized positive mediation, perceived accountability demonstrated a negative indirect effect on job satisfaction. This finding suggests that accountability, while essential for transparency and ethical governance, can also become a psychological stressor when perceived as externally imposed control rather than self-directed responsibility [40]. In hierarchical bureaucracies like the Taiwan Railways Administration (TRA), accountability expectations often take the form of top-down monitoring and rigid compliance, leaving employees with limited discretion. Such ‘accountability overload’ [8] may evoke role tension, fear of blame, and diminished intrinsic satisfaction, even among employees with high public service motivation.

The negative mediation can also be understood through the lens of role stress theory [12,40]. When accountability expectations exceed employees’ perceived autonomy or available resources, accountability becomes a source of cognitive strain rather than motivational clarity. Employees must justify their actions to multiple hierarchical levels, often with ambiguous or competing performance standards, which amplifies stress and undermines job satisfaction.

5.2. Practical Implications

For public managers, results highlight the importance of cultivating both motivational alignment and empowered accountability. Recruitment and training systems should emphasize organizational values that resonate with employees’ PSM, while accountability frameworks should focus on transparency, learning, and ethical responsibility. Designing evaluation systems that recognize compassion, civic commitment, and integrity can strengthen satisfaction and retention within public organizations.

This study refines accountability theory by showing that perceived accountability does not uniformly enhance job satisfaction. Instead, its motivational valence depends on whether accountability is experienced as empowering self-regulation or as externally imposed surveillance. This insight extends the psychological accountability literature by introducing a stress-based interpretation relevant to high-control bureaucratic settings.

An intriguing and theoretically meaningful finding of this study is the negative association between perceived accountability and JS. This suggests that, in the TRA, high levels of perceived accountability may operate as a double-edged sword. While accountability is essential for ethical performance, excessive or externally imposed accountability can produce psychological strain, heightened surveillance, and diminished autonomy [40]. When employees feel constantly answerable to multiple hierarchical layers and public scrutiny, accountability becomes stress-inducing rather than motivational. This pattern resonates with the ‘accountability overload’ phenomenon observed in other bureaucratic systems [7,12]. In this context, employees’ satisfaction may decrease because accountability is perceived not as trust and responsibility, but as bureaucratic monitoring that restricts discretion and decision latitude.

Therefore, our findings refine the conventional view of accountability as purely beneficial, demonstrating that its motivational effect depends on whether employees perceive it as enabling self-regulation or enforcing bureaucratic compliance. In public enterprises undergoing reform, accountability systems should thus be designed to encourage learning, trust, and professional discretion rather than punitive oversight.

5.3. Toward Sustainable Public Institutions

The present findings advance PSM theory by revealing that motivation’s effect on JS depends on how employees internalize accountability and perceive organizational congruence. This dual-path framework bridges motivational and institutional perspectives, showing that sustainable satisfaction arises when accountability is experienced as moral responsibility rather than bureaucratic control. Thus, the study contributes to role theory and fit theory by positioning perceived accountability as a self-regulatory mechanism linking prosocial motives to well-being within public organizations.

A workforce that is motivated, value-aligned, and accountable is vital for institutional resilience and sustainability. The study highlights that nurturing public service-oriented human capital directly contributes to achieving SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) by promoting effective, transparent, and citizen-centered governance. Future research should build upon this framework through longitudinal and cross-cultural analyses to further validate the model and support the global agenda for sustainable public administration.

Culturally, in East Asian public organizations such as TRA, accountability tends to be externally defined and vertically enforced, emphasizing compliance over autonomy. Employees’ sense of responsibility may therefore be shaped by fear of sanctions or public criticism rather than intrinsic commitment to public values. This hierarchical accountability culture can erode the positive motivational benefits of PSM, transforming accountability into a stressor instead of a source of satisfaction.

By embedding PSM, PO-Fit, and perceived accountability within a unified model, this study offers a conceptual foundation for cultivating motivated, satisfied, and accountable public servants—an essential condition for achieving transparent and resilient governance systems aligned with SDG 16. Future research should build upon this framework to explore cross-cultural variations in accountability perceptions and their implications for sustainable public administration.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

There has yet to be a thorough study of perceived accountability in the public institutions. Such research is crucial for advancing academic understanding of the antecedents, moderators, and outcomes associated with PA. To date, accountability research has paid limited attention to informal accountability mechanisms [12]. These informal mechanisms influence how accountability is perceived. The overlap among existing definitions of PA allows researchers to employ role theory to gain a deeper understanding of accountability structures. Additionally, it is hypothesized under this theory that employees would utilize their perceived expectations to influence their attitudes and behavior.

The data are self-reported and, although collected at two time points to reduce common method bias, the study design remains largely cross-sectional. Therefore, the findings cannot establish strict causal relationships among PSM, PO-Fit, PA, and JS. Future research could employ longitudinal or experimental designs to more robustly test the causal mechanisms proposed in this model.

Moreover, the study was conducted within the Taiwan Railways Administration, a large public utility with strong hierarchical and collectivist features that may shape perceptions of accountability and JS differently from Western or private-sector settings. This cultural specificity may explain, in part, the distinctive patterns observed in the mediation effects. Future comparative research across countries or public service sectors could examine how institutional context, cultural norms, and administrative traditions moderate the relationships identified in this study.

Individuals’ perceptions, interpretations, and internalization shape perceived accountability. Environmental factors such as span of control, de/centralization, standards, and the legal system might affect PA. Accordingly, it is suggested that public employees form their PA based on organizational norms and rules concerning the presence, level, and nature of accountability.

Additional research should examine the effects of individual variations on PSM, performance, and perceived accountability. Likewise, this study overlooks variations in the composition of PA (e.g., its nature and elements) in examining the link between PSM and performance [73,74]. Whether a different composition of perceived accountability affects the efficacy of work outcomes is still unknown. The limitations identified in this study provide meaningful opportunities for further investigation. To begin with, the current study used a non-experimental research design; future research can be directed by employing other research designs, which may produce better estimates for the mediation effect. Next, the current study has investigated PO-fit and PA as proposed mediators in the linkage between PSM and JS. However, it should be noted that the results of the current research support the proposed model, but this does not mean that the model employed in the study is uniquely aligned with the obtained results. Future studies should investigate other potential mediating factors in the linkage between PSM and JS. Finally, the research focused only on one public utility (i.e., TRA); future investigation could be conducted in other organizational and cultural settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.-T.C.; Writing—Original Draft, K.-T.C. and H.-W.T.; Funding Acquisition, H.-W.T.; Writing—Review and Editing, K.-T.C., H.-W.T., C.-F.C. and K.C.; Supervision, C.-F.C.; Project Administration, K.-T.C.; Methodology, K.-T.C. and K.C.; Formal Analysis, K.-T.C. and H.-W.T.; Data Curation, K.C. and C.-F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kim, S. Does Person-Organization Fit Matter in the Public Sector? Testing the Mediating Effect of Person-Organization Fit in the Relationship between Public Service Motivation and Work Attitudes. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wen, B.; Song, Y. A Moderated Mediation Model on the Relationship Among Public Service Motivation (PSM), Self-Efficacy, Job Satisfaction, and Readiness for Change. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2024, 0, 0734371X241281750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Disclosing the relationship between public service motivation and job satisfaction in the Chinese public sector: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1073370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, P.; Lewis, G.B. Public service motivation and job performance: Evidence from the federal sector. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2001, 31, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, D.P.; Pandey, S.K. Finding workable levers over work motivation: Comparing job satisfaction, job involvement and organizational commitment. Adm. Soc. 2007, 39, 803–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, N.; Kim, G.J. Why Public Service Motivated Government Employees Experience Varying Job Satisfaction Levels Across Countries: A Meta-analysis Emphasizing Cultural Dimensions. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2024, 47, 1014–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G.A. Dueling banjos in American public administration: The enduring themes of accountability and performance. In Handbook of American Public Administration; Stazyk, E.C., Frederickson, G., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 119–1369. [Google Scholar]

- Hochwarter, W.A.; Ferris, G.R.; Gavin, M.B.; Perrewé, P.L.; Hall, A.T.; Frink, D.D. Political skill as neutralizer of felt accountability--job tension effects on job performance ratings: A longitudinal investigation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 2007, 102, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gan, K.-P.; Wei, H.-Y.; Sun, A.-Q.; Wang, Y.-C.; Zhou, X.-M. Public service motivation and public employees’ turnover intention: The role of job satisfaction and career growth opportunity. Pers. Rev. 2024, 53, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubnick, M.; Frederickson, G. Public Accountability: Performance Measurement, the Extended State, and the Search for Trust; National Academy of Public Administration & The Kettering Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Perry, J. Conceptual bases of employee accountability: A psychological approach. Perspect. Public Manag. Gov. 2020, 3, 288–304. [Google Scholar]

- Frink, D.D.; Klimoski, R.J. Toward a theory of accountability in organizations and human resource management. In Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management; Ferris, G.R., Ed.; JAI Press: Stamford, CT, USA, 1998; Volume 16, pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hochwarter, W.A.; Perrewé, P.L.; Hall, A.T.; Ferris, G.R. Negative affectivity as Management Decision Management Decision a moderator of the form and magnitude of the relationship between felt accountability and job tension. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.-T.; Chang, K. The efficacy of stress coping strategies in Taiwan’s public utilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Util. Policy 2002, 79, 101431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Na, C. Public Service Motivation and Job Satisfaction Amid COVID-19: Exploring the Effects of Work Environment Changes. Public Pers. Manag. 2024, 53, 281–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.B.; Kjeldsen, A.M. Public Service Motivation, User Orientation, and Job Satisfaction: A Question of Employment Sector? Int. Public Manag. J. 2013, 16, 252–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.; Wise, L. The motivational bases of public service. Public Adm. Rev. 1990, 50, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G.A.; Selden, S.C. Whistle Blowers in the Federal Civil Service: New Evidence of the Public Service Ethic. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 1998, 8, 413–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Individual-level factors and organizational performance in government organizations. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2005, 15, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. The impact of public service motives on work outcomes in Australia: A comparative multi-dimensional analysis. Public Adm. 2007, 85, 931–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. What is job satisfaction? Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1969, 4, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Chung, I.H. Effects of Public Service Motivation on Turnover and Job Satisfaction in the U.S. Teacher Labor Market. Int. J. Public Adm. 2017, 41, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, C.Y.; Moon, M.J.; Yang, S.B.; Jung, K. Linking Emotional Labor, Public Service Motivation, and Job Satisfaction: Social Workers in Health Care Settings. Soc. Work. Public Health 2016, 31, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homberg, F.; McCarthy, D.; Tabvuma, V. A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Public Service Motivation and Job Satisfaction. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giauque, D.; Ritz, A.; Varone, F.; Anderfuhren-Biget, S. Resigned but Satisfied: The Negative Impact of Public Service Motivation and Red Tape on Work Satisfaction. Public Adm. 2012, 90, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderfuhren-Biget, S.; Varone, F.; Giauque, D. Policy Environment and Public Service Motivation. Public Adm. 2014, 92, 807–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, L. Does public service motivation really make a difference on the job satisfaction and turnover intentions of public employees? Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2008, 38, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.E.; Pandey, S.K. Public Service Motivation and the Assumption of Person-Organization Fit: Testing the Mediating Effect of Value Congruence. Adm. Soc. 2008, 40, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, L. Does person-organization fit mediate the relationship between public service motivation and the job performance of public employees? Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2007, 27, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.H.; McDonald, B.; Park, J. Does Public Service Motivation Matter in Public Higher Education? Testing the Theories of Person–Organization Fit and Organizational Commitment Through a Serial Multiple Mediation Model. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2016, 48, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. Organizational influences, public service motivation and work outcomes: An Australian study. Int. Public Manag. J. 2008, 11, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steijn, B. Person-Environment Fit and Public Service Motivation. Int. Public Manag. J. 2008, 11, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Vandenabeele, W.; Wright, B.E.; Andersen, L.B.; Cerase, F.P.; Christensen, R.K.; Desmarais, C.; Koumenta, M.; Leisink, P.; Liu, B.; et al. Investigating the Structure and Meaning of Public Service Motivation across Populations: Developing an International Instrument and Addressing Issues of Measurement Invariance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2013, 23, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romzek, B.S.; Dubnick, M.J. Accountability in the Public-Sector: Lessons from the Challenger Tragedy. Public Adm. Rev. 1987, 47, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romzek, B.S. Accountable public services. In The Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability; Bovens, M., Goodin, R.E., Schillemans, T., Eds.; Oxford Univ Press: London, UK, 2014; pp. 307–323. [Google Scholar]

- Kettl, D.F.; Kelman, S. Reflections on 21st Century Government Management; IBM Center for the Business of Government: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan, D.P.; Pandey, S.K. The role of organizations in fostering public service motivation. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, S.; Madumo, O. Who should we pay more? Exploring the influence of pay for elected officials and bureaucrats on organizational performance in South African local government. Public Adm. 2022, 102, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.T.; Frink, D.D.; Buckley, M.R. An accountability account: A review and synthesis of the theoretical and empirical research on felt accountability. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Kim, Y. Revisiting public service motivation: A context-specific exploration of its linkages to job performance pre- and post-COVID-19. Chin. Public Adm. Rev. 2025, 16, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.Y.; Moom, K.-K.; Christensen, R.K. Does psychological empowerment condition the impact of public service motivation on perceived organizational performance? Evidence from the US federal government. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2021, 88, 682–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salancik, G.; Pfeffer, J. A Social Information Processing Approach to Job Attitudes and Task Design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1987, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J. Managing Organizations to Sustain Passion for Public Service; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, S.S.; Gupta, R.; Jena, L.K. Contrasting effects of leadership styles on public service motivation: The mediating role of basic psychological needs among Indian public sector officials. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2022, 35, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, N.; Hawaldar, A. Role of management education in adapting the Indian public sector to market-based economic reforms. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2023, 36, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarrow, G.; Jasinski, P. Privatization: Critical Perspectives on the World Economy; Routledge: London, UK, 1996; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinkin, T.R. A review of scale development practices. J. Manag. 1995, 21, 967–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.E.; Judge, T.A. Self-concordance at work: Toward understanding the motivational effects of transformational leaders. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mero, N.P.; Guidice, R.M.; Werner, S. A Field Study of the Antecedents and Performance Consequences of Perceived Accountability. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1627–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D.M.; DeRue, D.S. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H.; Vinzi, V.E.; Russolillo, G.; Saporta, G.; Trinchera, L. The Multiple Facets of Partial Least Squares and Related Methods PLS; Springer: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vinzi, V.E.; Chin, W.W.; Henseler, J.; Wang, H. Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications; Springer: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Latan, H.; Noonan, R. Partial Least Squares Path Modeling Basic Concepts, Methodological Issues and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, T.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Carrión, G.A.; Nitzl, C.; Roldán, J.L. Mediation Analyses in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Guidelines and Empirical Examples. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling Basic Concepts, Methodological Issues and Applications; Latan, H., Noonan, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 173–196. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.C.; Tang, T.L.-P.; Yang, K. When Does Public Service Motivation Fuel the Job Satisfaction Fire? The Joint Moderation of Person–Organization Fit and Needs–Supplies Fit. Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 17, 876–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.C. Evidence of public service motivation of social workers in China. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2019, 75, 349–366. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Vandenabeele, W. A Strategy for Building Public Service Motivation Research Internationally. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovits, Y.; Davis, A.J.; Fay, D.; van Dick, R. The Link Between Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: Differences Between Public and Private Sector Employees. Int. Public Manag. J. 2010, 13, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, S.I. Mapping accountability: Core concept and subtypes. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2013, 79, 202–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarais, C.; Gamassou, C.E. All motivated by public service? The links between hierarchical position and public service motivation. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2014, 80, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.M.; Kim, M.Y. Accountability and public service motivation in Korean government agencies. Public Money Manag. 2015, 35, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, G.; Thomasson, A. Bridging the accountability gap in hybrid organizations: The case of Copenhagen Malmö Port. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2015, 81, 604–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaoul, J.; Stafford, A.; Stapleton, P. Accountability and corporate governance of public–private partnerships. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2012, 23, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel-Jacobs, K.; Yates, J.F. Effects of procedural and outcome accountability on judgment quality. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1996, 65, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.; Hondeghem, A. Motivation in Public Management: The Call for Public Service; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jaškevičiūtė, V.; Zsigmond, T.; Berke, S.; Berber, N. Investigating the impact of person-organization fit on employee well-being in uncertain conditions: A study in three central European countries. Empl. Relat. 2023, 46, 188–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wightman, G.B.; Christensen, R.K. A systematic review of person-environment fit in the public sector: Theorizing a multidimensional model. Public Adm. Rev. 2025, 85, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisink, P.; Andersen, L.B.; Brewer, G.A.; Jacobsen, C.B.; Knies, E.; Vandenabeele, W. Managing for Public Service Performance: How People and Values Make a Difference; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, K.-T. Public service motivation and job performance in public utilities. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2015, 28, 352–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).