Abstract

This paper contains an overview of the human colonisation of Australasia and Oceania over the last 65,000 years, and highlights the resultant diversity of settlement types, place and cultural landscape formations, and architectural solutions, but simultaneously gives attention to the long-term retention of particular traditions throughout the study region. The time, geographic and multi-cultural scales are thus vast, implying this is a study in the category of ‘deep history’. However, the author has drawn from his editing of the regional volume of ‘Australasia and Oceania,’ for the 2nd edition of the Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, or EVAW 2, containing some 200 contributions on this region. Two migratory events are explored. The first is that of Aboriginal people into Australia some 65,000 years ago. The second is the Austronesian migrations into the Pacific Ocean from 5000 to 1500 BP. Despite millennia of cultural, environmental, climatic, economic and warfare disruptions, a series of continuities of tradition are identified and analysed in a limited manner due to the brevity of the paper. However, the paper provides a significant contribution in making such a broad-scale holistic overview of the pattern languages of building traditions that link communities in Oceania and Australasia arising from past migrations and drawing on multi-disciplinary sources.

1. Introduction

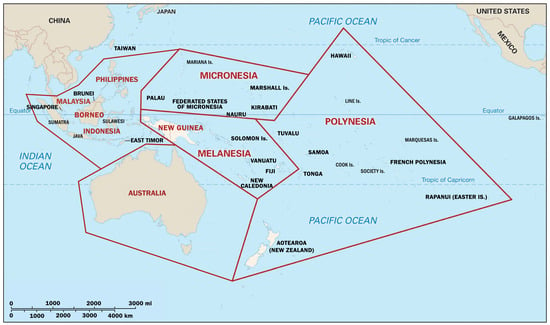

This overview of the human colonisation of Australasia and Oceania over the last 65,000 years highlights the resultant diversity of settlement types, place and cultural landscape formations, and architectural solutions, but simultaneously gives attention to the long-term retention of particular traditions throughout the study region. The time, geographic and multi-cultural scales are thus vast, implying this is a study in the category of ‘deep history’. However, I have been inspired by my editing of the regional volume of ‘Australasia and Oceania,’ for the 2nd edition of the Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, or EVAW 2 [1], containing some 200 contributions covering Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of the study region divided into sub-regions based on the chapter divisions in EVAW 2 (Adapted from Encyclopaedia Britannica).

Despite millennia of cultural, environment, climatic, economic and warfare disruptions, a series of continuities of tradition will be identified and analysed in a limited manner due to the brevity of the paper. However, the paper will provide a significant contribution in making such a broad-scale holistic overview of the pattern languages of traditions, drawing on multi-disciplinary sources.

The immense diversification of house types and building technologies in this vast region represents material culture sub-sets of a broad cultural diversity of behavioural characteristics which can be theorised in the scale of deep time, and to be the outcome of three migratory colonising populations adapting to the many different environments and climates in the region [2].

The first wave of migration occurred after 65,000 BP, perhaps closer to 50,000 BP, when the ocean levels were much lower due to large volumes of seawater being locked up at the north and south poles during the Ice Age. Some of the colonising peoples adapted their economies to incorporate agriculture and fishing, whilst others moved to inland forests to maintain a hunter–gatherer–forager lifestyle, particularly in Australia and parts of what are now Indonesia, Malaya, and the Philippines [2].

The second wave or set of colonising populations migrated from Taiwan into various parts of the Pacific Ocean (now termed the ‘Polynesian Triangle’) during the period 5000 BP to 1500 BP, and were made up of what are now termed Austronesian peoples. This occurred during the rising of sea levels during the late Holocene period, and with the technological aid of, at first, single-hull then double-hull outrigger canoes.

A third set of influences was then overlaid on these first two migratory waves during the most recent millennia. At first this involved Buddhist, Muslim and Hindu colonisers from as early as the 10th century, and then from the 1400s and spanning over several centuries, the Europeans arrived: the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, British, French, and even Germans, who brought with them their architectural influences, impacting on the local vernacular forms [2].

This exploratory paper examines various continuities of tradition from those migratory origins including lightweight rainforest shelters, boat references in architecture, Austronesian dwelling characteristics and Polynesian malae (or marae) spaces. The paper also asks what cultural continuities can still be identified in the architectural traditions of the founding immigrants to Australasia and Oceania, who colonised over 65,000 years in the case of the former, and 5000 years in the case of the latter.

2. Methods

The study draws on a number of data sets and methods. As mentioned, one method is to draw data from the 200 entries to the ‘Australia and Oceania’ volume of the second edition of the Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World or EVAW2 [1]. The second using the reference work of Bellwood et al. [3] to date the various stages of the Austronesian migratory pulses. The third method is the use of visual anthropology to review the photographic evidence of the last 200 years, with the potential for comparison between earlier records and post-2000 images, some visual exemplars of houses being extant [4,5]. Another source of data is drawn from the existing literature on the topic of Austronesian houses including the seminal work by Fox [6].

3. Results

3.1. Contextualising the Architectural Traditions of Australasia and Oceania

The island cultures of Southeast Asia, Australia and the Pacific are the focus of this paper. The Pacific islands of Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia are scattered across some 11,000 km (7000 mi) from east to west, and over 8000 km (5000 mi) from north to south. To the west of the region, however, the islands are closer together and, though they number many thousands, they include some of the largest islands in the world, namely New Guinea, Borneo, and those in the Philippines and Indonesia [1].

The current climates vary from tropical around the equator, with monsoons and cyclones towards the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, ranging to temperate in the south of Australia and New Zealand where winter snow-covered alps occur. The populations of the region have been the subject of considerable archaeological and linguistic analysis and debate, and various hypotheses as to their origins. Occupation sites as old as the mid-Pleistocene (before 50,000 BP) have been located in Australia [1].

The immense variety of house designs and construction technologies across this vast region represents material culture sub-sets of a broad cultural diversity of behavioural characteristics which can be theorised through research into deep history to be the result of three migratory colonising populations adapting to a wide range of ecosystems and resources. It is instructive to consider and examine this historical process of migration and cultural adaptation, because a challenge for the study of contemporary vernacular architecture is understanding how particular architectural features commonly persist across the settlements of many widespread island communities, and further, whether they will continue to persist in the face of globalisation.

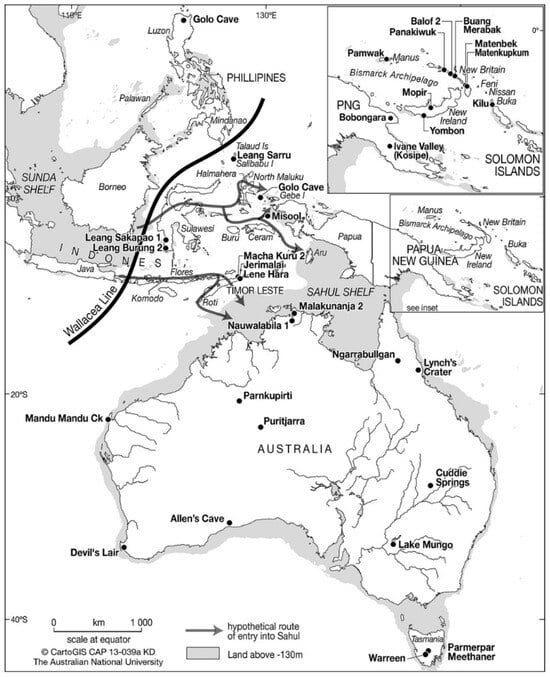

Understanding the processes of colonisation continues as a research subject for multi-disciplinary scholars, but the consecutive waves of migration across Pasifika also continue to be examined and refined in their nature, temporally. The first wave is the movement of peoples during the Ice Age when ocean levels were lower during c. 65,000 to 50,000 BP. During this period, the region was divided between the landmass of the southeastern Eurasian continent which incorporated the (now) islands of Sumatra, Java, Bali and Borneo (this land being now termed ‘Sunda’), and the separate continent (now termed ‘Sahul’) that incorporated New Guinea, Australia and Tasmania. Crossing the Wallace line strait was facilitated by being able to see the island from where one was coming and the next island to where one was going. This ease of safe travelling in basic watercrafts (rafts) allowed crossing during the Ice Age when sea levels were much lower, and resulted in the immigration of fisher–hunter–gatherer peoples from Sunda to Sahul [3,7,8] (pp. 26, 34). Two possible migratory routes have been identified: one into the Birdshead Peninsula of New Guinea and the other into the continental shelf of Australia approximately where Bathurst Island now is [7,9] (pp. 260, 263) (Figure 2). The methodology of Kealy et al. took into account seismic uplift as well as the land heights of the viewer and the viewed, which included some mountainous islands along the migratory routes [7].

Figure 2.

Map of the ancient landmasses of Sunda and Sahul, showing two alternate migration routes across Wallacea, and ancient dated archaeological sites of significance [8] (p. 27). Map reproduced with permission from CartoGIS Services, Scholarly Information Services, The Australian National University.

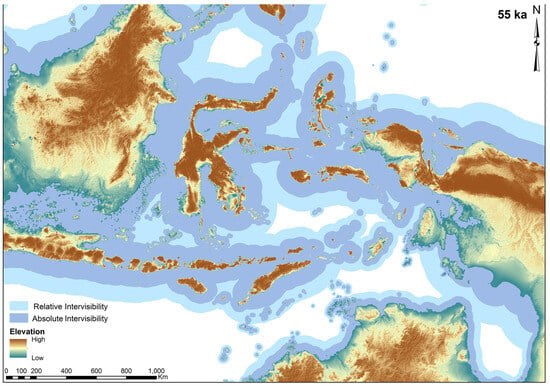

In a test of the extent of visibility of the land from the sea, carried out for an Australian Native Title sea claim (Wellesley Islands), the author took a group of marine hunters in a fast boat out to sea at right angles to the land, a low sand-based island, on a relatively calm, fine day (Figure 3). They asserted they lost visual contact with the land at approximately 22 kms.

Figure 3.

Map showing the intervisibility of landmasses 55 ka ago, “Showing reconstructed topography and visibility buffers. The light blue buffer indicates regions of relative intervisibility [seeing land both backwards and forwards at mid-voyage] while the dark blue shows the estimates of absolute intervisibility [seeing the destination land from the departure land]” [7] (p. 266).

A number of insightful deep history analyses of the migration of humans into Sahul have occurred in recent years. The main early colonising migration routes or ‘superhighways’ were first impressively mapped by Crabtree et al. [10,11], taking into account “(i) topography; (ii) the visibility of tall landscape features; (iii) the presence of freshwater; and (iv) demographics of the travellers” [11] (p. 3). Their analysis also demonstrated some congruency of these routes with certain Aboriginal trade routes much later identified by ethnologists in the colonial period [12].

A recent advanced quantitative analysis of the time period for the populating of Sahul, sometime in the period between 65,000 and 50,000 years before present, has been undertaken by Bradshaw et al. [13]. It employs, on the one hand, understandings of the rates of the population increase for small groups of humans due to reproduction, as well as ongoing in-migration (sociospatial units called ‘cells’) before they saturate local resources, bringing about group fission and emigration, and on the other hand, environmental constraints on the rates of expansion, including a limited extent of resources, as well as climatic extremes [14], which in turn lead to the derivation of characteristic local material culture patterns still detectable today [15]. This mathematical analysis is combined with a Late Pleistocene ‘superhighway’ route analysis taking into account the oldest archaeological sites and involving directional selection choices, as well as the identification of the two most likely entry points to Sahul [16]. The result (from what the authors methodologically call ‘path models’ and ‘cellular automata’) is an estimate of the peopling of New Guinea over a span of 5000 to 6000 years, but a span of 10,000 years before the far southeast of Sahul, including what is now Tasmania, was peopled. Interestingly, the authors acknowledge in their conclusion that there is a qualitative gap in their analysis comprising the influences of “the broader human psyche (such as social and religious behaviour)” [13] (p. 11).

Turning to this aspect of human psyche, Oppenheimer remarked existentially that these “ancient ‘boat people’ took their legends and concepts of religion, astronomy, magic, and social hierarchy with them wherever they went” [17] (p. 556). In an exploratory analysis of the mass migration and settlement of Aotearoa (New Zealand) by eastern Polynesians, Walter et al. provide a useful processual model that could well be applicable to other island-hopping colonisations in our study region [18]. They argue that there would be a preliminary discovery phase by a skilful navigator, involving the initial location of an island or archipelago, then some exploration and knowledge acquisition of its resources. And then, at a substantial time later, an efficiently planned and executed return would be made by a substantial founder group made of different families (not all the same kin, but rather a gene pool), and led by one or several extraordinary charismatic men of authority (men of mana or power).

‘Boat people’ is a recurring demographic theme in the prehistory of the study region and still manifesting and relevant today in the vernacular architectures which may contain nautical symbolism.

3.2. Economic Diversification and Hybrid Economies

The resources of strand environments were sufficiently similar to allow ready migration of peoples easterly through the greater region starting from at least 60 k BP; however, economic diversification occurred within the inland terrestrial parts of Sunda, Sahul, Wallacea, Near Oceania and the Pacific. Every type of environment in Australia, New Guinea, the Solomons and the Philippines was eventually colonised by the end of the Pleistocene (about 12,000 BP) [19] (p. 48). As populations expanded into new environments, economic systems were adapted and evolved to exploit new habitats, particularly hunting, gathering, fishing, swidden, horticulture and agriculture.

Diversification of behavioural characteristics between different environments, as human groups reshaped economic and social practices in response to regional/local resources, was a common pattern, and may have initially been facilitated by the relative isolation of colonizing groups. This diversification may underpin the differing culture-historical trajectories that are evident at later times across the Sunda, Sahul and Near Oceanic regions.[8] (p. 42)

Another core economy, analytically separate from hunter–gatherer and agriculturalist, is that of arboreal-based subsistence economies, forms of forest and plant management that may include biodiversity encouragement, modifications to species compositions and the introduction of new or expansion of existing species, in order to maximise useful resource repertoires. Managed areas were multi-cropped spatially and temporally [19] (pp. 43–44). Part of the emergent arboreal-based economies was the exploitation of particular plant species for building materials. The materials in turn influenced the tectonics, forms and technologies of architectural traditions.

In Aboriginal Australia, arboriculture techniques included ‘fire farming’ to restrict the spread of certain species, and to allow habitat expansion for preferred species, the replanting of small tubers during harvesting of larger ones, the gifting of seeds of valued species, and the transportation of staple species to new habitats (e.g., offshore islands) [20,21].

Many of the new settler groups on land developed hybrid economies, combining semi-sedentary lifestyles utilising villages or hamlets (starting as base camps), carrying out swidden or paddy cultivation, but still supplementing these foods by deploying an outer hunter–gatherer range for forest foods as well as forms of arboriculture, supported by temporary foraging camps [19]. Their dwellings are more substantial with high platform floors and several rooms. In some cases, their villages were moved between several sites for shifting cultivation.

Subsistence system diversification is a process by which a population expands into a new environment that contains unexploited ecological opportunities (roughly synonymous with niche), and in which at least part of the population develops a new subsistence system to exploit the opportunity and increase fitness.[19] (p. 43)

A significant economic divergence towards the end of the Pleistocene was that of Highland root-cropping economies in New Guinea [19] (p. 50). A form of yam cropping or tuber conservation was also practised in certain parts of Australia as mentioned earlier [20] (pp. 27, 28), [21] (pp. 79, 82). One aspect of the Neolithic migrations was the transportation of pigs into various parts of the region, but mtDNA analyses remain ongoing concerning species distribution details [3] (p. 337).

A sociospatial feature of larger hunter–gatherer camps and villages was gendered divisions, especially for diurnal activities. For example in Aboriginal Australia, separate men’s activity groups and women’s activity groups were commonplace, whether for food collection or social and artisan-focused activities (e.g., stone tool manufacturing by men, or weaving and string manufacturing by women). These gendered divisions could be further subdivided by classificatory divisions such as moieties or sub-sections [22].

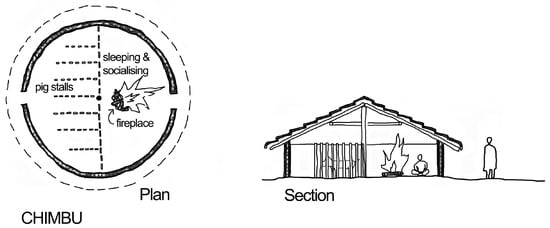

Much change has occurred in the New Guinea Central Highlands after some 9000 years of agricultural tradition, where missionaries eventually discouraged gendered houses in the mid-twentieth century. However, an exception is the Chimbu people in the east of the Highlands, who managed to retain the practice of building gendered houses. For example, Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the circular women’s round house which also accommodated the socially valued pigs, with interior partitioned and separate doors for animals and humans.

Figure 4.

Circular house in a Chimbu village, eastern highlands of Papua New Guinea, 2007 (photo by David Bacon).

Figure 5.

Plan and cross-section of a typical women’s house of the Chimbu (Simbu). Redrawn from Loupis [23] (p. 29).

There is one remarkable and ancient Australian Aboriginal architectural exemplar that remains: the rock-shaped art gallery, ritual theatre and living area of Nawarla Gabarnmang. Located in Arnhem Land, in the territory of the Jawoyn people, it is a combined residential site, ceremonial centre and art gallery. Occupied for 50,000 years, over some 200 generations, it comprises two rock strata, one on top of the other and separated by several metres with thick stone columns created through ancient geological processes (Figure 6 and Figure 7). The occupants started removing some of the stone columns between 35 and 23 BP so as to render more roof space available for the accumulating artworks. Some of the removed stone was shaped into blocks, 40 cm long and used as seat furniture, and referred to in contemporary Aboriginal English as ‘pillows’ [24] (pp. 336–339).

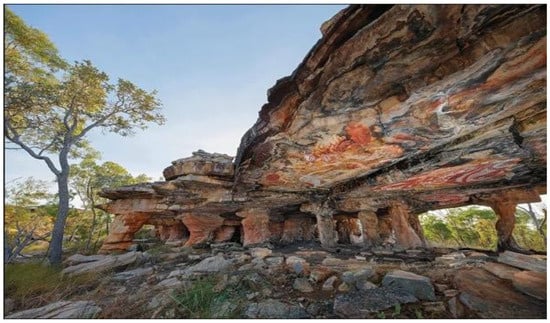

Figure 6.

The pillar structure of Nawarla Gabarnmang was initially shaped by a natural geological weathering process and then by Aboriginal stonemasons, who selectively removed columns and ceiling rock to create art surfaces, some 30,000 years ago (photo by John Gollings).

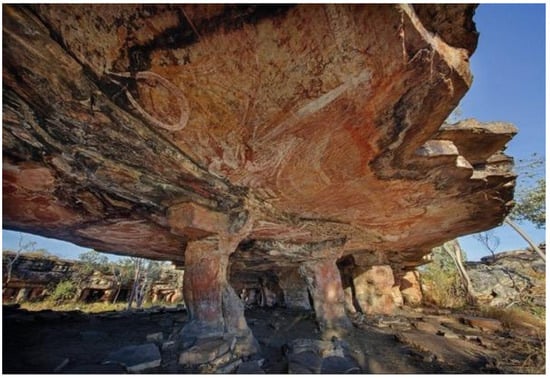

Figure 7.

A portion of the extensive artwork painted on the stone ceiling of Nawarla Gabarnmang, which overlays centuries of earlier artwork (photo by John Gollings).

Although many of the descendant groups of this original migratory wave adapted their economies to become agriculturalists, fishers, etc., a good proportion, especially those who travelled up rivers into upland forested habitats, maintained their hunter–gatherer economies, especially in the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Australia, West Indonesia and the Philippines. The dwellings of these groups were relatively quickly made with lightweight frames, leaf thatching and on-ground or low-set platforms. The Semang and other Orang Asli groups in the Archipelago (e.g., Anak Dalam/Kubu of Sumatra, Dumagat in the Philippines, Mabri in northern Thailand), as well as Australian Aboriginal groups, utilised basic lean-to forms allowing domiciliary groups to be externally oriented, in close visual and auditory communication, and sharing resources. These structures were still recorded in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

One such widespread shelter type, still found in the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, and the Philippines, as well as elsewhere in Southeast Asia, is the lean-to ‘leaf-shield’ combined with a sitting/sleeping platform. The leaf-shield is a rectangular frame within which there is interwoven thatching. Once manufactured, the shield is leant against a ridge pole which is supported on two forked posts. At about 30 cm above ground level, a sitting and sleeping platform of saplings is supported on a substructure (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Leaf shield and sitting platforms of the Semang of Peninsular Malaysia, 2006. (Photo by Niclas Burenhult).

To achieve insect repellence as well as warmth, fires were kept burning on several sides of the platform. When wet weather worsened, a roof was added by fixing a ridge pole in place and then leaning leaf shields on both sides. This triangulated form was used by hunting–gathering–foraging bands ranging from a base camp who required only temporary shelter for one or two nights. The shelters were built close together, enabling visibility and ease of communication between adjacent groups, reflecting the norm of sociality (rather than privacy), and facilitating the sharing of food and other resources, another norm of hunter–gatherers [25].

In Aboriginal Australia, leaf shields made of palm leaves were commonplace in the rainforest regions of the north (Figure 9 and Figure 10). However in the temperate forested regions of eastern Australia, a protection device for wind and rain was manufactured from the rigid bark of mostly Eucalyptus trees, which could be cut from the tree trunk in a 2 m × 1 m sheet, then heat-treated to flatten. Bark cladding began to be replaced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by sheets of galvanised iron. This material is still used in remote parts to facilitate outdoor living styles, even when conventional houses are available (see Figure 11 and Figure 12) [26].

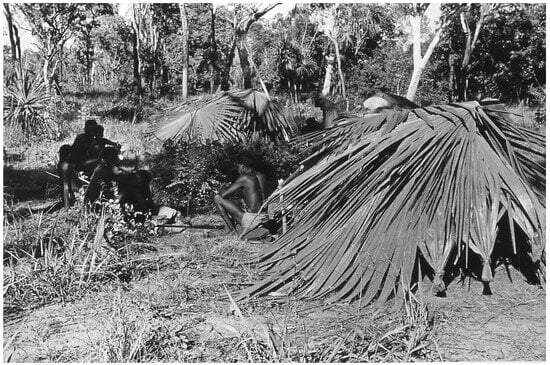

Figure 9.

A temporary shelter constructed using the leaf of the fan palm (Corpha utan) draped over six short posts. Constructed by the Ritharrngu language group, Birtingal clan of Arnhem Land, Australia, in 1967. (Photo by Nicolas Peterson).

Figure 10.

Palm leaf rain cover for cooking fire, Kowanyama, Cape York, Australia, 2017. (Photo by Viv Sinnamon).

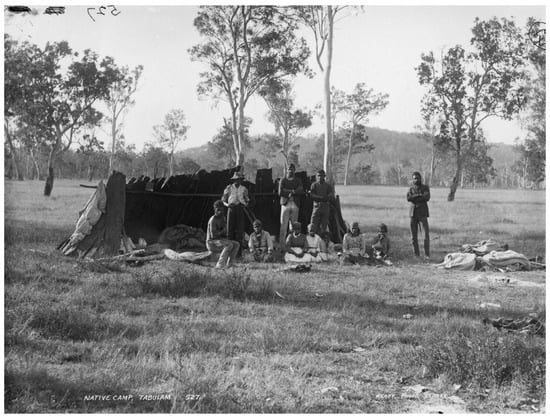

Figure 11.

A high bark lean-to sheltering from wind and light rain, at Tabulam, Upper Clarence River, New South Wales, Australia, 1890s. (Photo by Charles Kerry).

Figure 12.

Irene Clark in front of a corrugated steel windbreak constructed by the Jimberella Housing Cooperative for her home in Dajarra, Australia, 2013. (Photograph by Tim O’Rourke).

Such cultures in which shelter is minimal are essentially those of nomadic forest peoples who live by foraging, such as the Semang groups of the Malay Peninsula and the Punan of Borneo. Those who lead a foraging life-style must maintain an ideological commitment to non-materialism; they could have no use for elaborate houses since they are often on the move. Nor are houses necessary as a means of displaying rank or wealth, since these societies almost invariably are among the most egalitarian known to us.[27] (p. 91)

The coastal and in-shore hunter–gatherers were largely impacted by Austronesian immigrations and acculturation from c5000 years ago, so much so that they were reduced to a minority and their languages were replaced. However hunter–gatherer camps still persist in more remote inland parts of many larger islands, including in the Philippines [28], as well as Australia.

3.3. The Austronesian Migrations

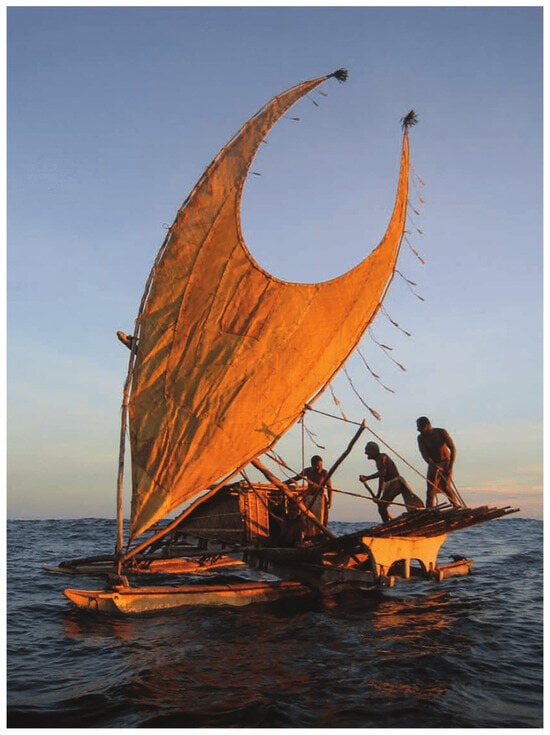

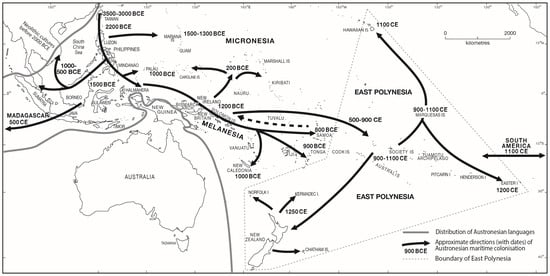

When the sea levels rose at the end of the Holocene period, from 5000 BP to 1500 BP, the second migration occurred from Taiwan, commonly referred to as the ‘Austronesian migration’. Closer islands were reached using single-hull outrigger canoes. Then, with the technological creation of an effective double outrigger canoe, an outward migratory pulse occurred eastward into the Pacific Ocean, and into what scholars have termed the Polynesian triangle with Rapanui (Easter Island) and Hawaii at its extremities [29] (Figure 13 and Figure 14).

Figure 13.

A double-hulled outrigger canoe, or Te Alo Lili, sailing in Solomon Islands, 2017, where the ancient sailing navigation skills have been maintained. (Photo by Mimi George.) Mimi George’s research has involved the documentation and revitalisation of voyaging canoe travel amongst particular cultural groups [30].

Figure 14.

The dispersal of Austronesian-speaking peoples according to linguistic directionality and archaeological chronology. (Courtesy of Peter Bellwood.) CE refers to the ‘common era’, indicating the number of years since its beginning (2025 years ago); BCE refers to ‘before common era’, indicating the number of years before the beginning of the ‘common era’.

Marine knowledge was developed of ocean currents, climatology, and astronomy, and compiled into shell maps to facilitate navigation over the vast distances. It is not accidental then that Austronesian houses and villages throughout Pasifika contain recurring design references to boat form and technology, as well as to wider aspects of seafaring culture.

Evidence for competing hypotheses (including genetic) on the origin of the Austronesian peoples has come to favour the ‘Out of Taiwan’ model [3] (p. 346), [29] (p. 417).

There is now a near-universal agreement among both linguists and archaeologists that the Austronesian expansion began from Taiwan, somewhat more than a millennium after it was settled by Neolithic rice and millet farmers from Southeast China.[29] (p. 417)

This initial migration into Taiwan came from China at 6000 BP, whilst the eastward migration from Taiwan commenced at 5000 BP The researchers Bellwood et al. found that the migrations expedited in later millennia:

The linguistic findings match the archaeological record with regard to dispersal speed. The archaeology… indicates that Neolithic cultural complexes dispersed at some speed, between c.2000 and 1350 BC, from the northern Philippines southwards into the Indo-Malaysian archipelago, and eastwards beyond New Guinea into the Bismarck Archipelago.[3] (p. 346)

The final pulse of travel beyond the Fiji–Tongan–Samoan region occurred during 700–1200 AD into the northern, eastern and southern parts of Polynesia including the extremities of Hawai’i, Easter Island and New Zealand [29] (p. 429).

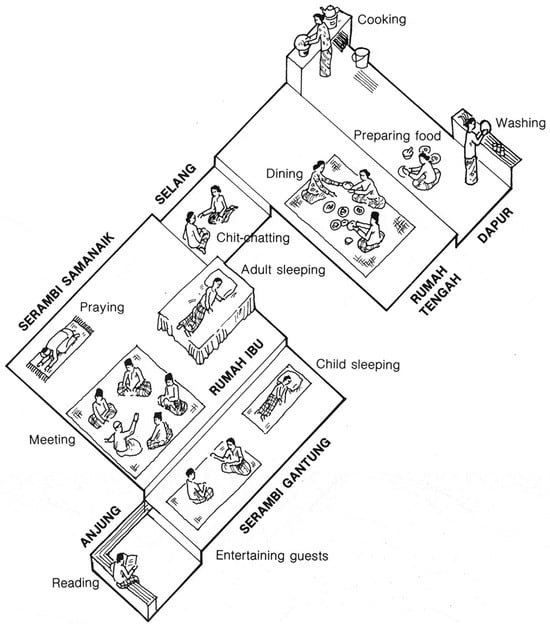

3.4. The Classical Austronesian House Elements

It is in the western part of the Oceania and Australasian region where the architectural components of the Austronesian house have been best analysed to date, especially in Malaysia and the Indonesian archipelago. These components or elements can be listed as follows. First, the house is divided into three vertical zones or levels. The central level is that of human habitation. The under-the-house zone is the habitation area of farm animals. The upper zone of this tripartite division is the attic of the house which is believed to be inhabited by sacred inanimate entities. The second architectural house component is platform floors on timber posts to generate a multi-levelled house (Figure 15). The erection of internal posts maintains their original vertical alignment with the bottom positioned to the root end and the top to the branch-and-leaf end. Some internal posts are believed to be ‘ritual attractors’ to bring benevolent spirits into the house. Other signature architectural elements are that both the end-gables and side walls are outward-sloping, whereas the roof is saddle-backed. The roof is typically decorated with finials at the extremities of the curving ridge. The orientation of the house is such as to conform to cosmological beliefs about the positioning in the cultural landscape [6,27] (pp. 14, 15), [31] (p. 23). However there are many combinations and permutations of these elements and they seldom all occur together in a single local style of vernacular architecture.

Figure 15.

The different gendered uses and floor heights of spaces within a traditional Malay house. Female activities to the rear (top of diagram) and male activities to the front [32] (p. 36).

The anthropologist James Fox has assembled and comparatively examined ethnographies of Austronesian houses drawn from Malaysia and Sumatra in the west, New Zealand and Goodenough Island in the east, and Southeast Asia to Melanesia and the Pacific [6]. Nevertheless, Fox notes that most Austronesian homes possessed what he called a ‘ritual attractor’, which from the time of a house’s construction is a piece of the house’s architecture which is identified as a ritual focal element. James Fox identified recurring ritual attractors in Austronesian houses, particularly the hearth, the ridge beam, the entry ladder and particular posts, and stated that such elements symbolised the house as a whole for the occupants. This finding also holds for northern groups of Australian Aboriginal people in Cape York Peninsula and Arnhem Land; in particular, the forked post and ridge pole were considered to be ‘ritual attractors’ in these regions [33] (pp. 249, 256).

3.5. The Austronesian Houses of the Malay Peninsula

The Orang Asli are the descendants of the earliest hunter–gatherer peoples of the Malay Peninsula and comprise a range of linguistic and tribal groups (Senoi, Jakun, Temuan, Semelai, Semang, Temiar, and Orang Laut). Pressure from later immigrating groups has resulted in them being reduced to a relatively small territorial domain in densely forested inland parts of the northern Peninsula. One group, glossed as the Proto-Malays who adopted an agricultural economy due to Malay influence, developed more sedentary houses of bamboo frames and palm leaf thatch on platforms supported by bamboo poles [34].

The Malay people are descendants of Austronesian groups who immigrated from largely Sumatra and Borneo from c. 4000 BP and who developed a distinct Malay identity with cultural protocols of conformity to customs of “dress, manners, language, literature, governmental systems, … architecture and kampong [suburban] settlements, and Islam” [34].

Despite the adoption of Islam, many pantheistic practices from the Austronesian ancestors persist, involving the spirits of both animate and inanimate things. The traditional Malay house with steeply pitched roofs on platforms and with timber poles founded on base stones has the classical cosmological tripartite division into the upper spirit world (roof), middle human habitation world and undercroft livestock world (Figure 16 and Figure 17) [34].

Figure 16.

House with shallow saddle-backed roof built according to Adat Perpatih (local customary law), Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia, 1991. (Photo by Paul Oliver).

Figure 17.

Example of a Malay-style house. The Bugis Seri Salewangeng at Pontian, Johor, Malaysia, 2014. Different roof heights reflect changes in floor levels. (Photo by Tang Sou Teng [35]).

3.6. Austronesian Exemplars from Eastern Indonesia and the Philippines

To illustrate some recently recorded exemplars of traditional architecture with Austronesian elements, case studies from some five diverse groups will be briefly summarised based on EVAW2 entries.

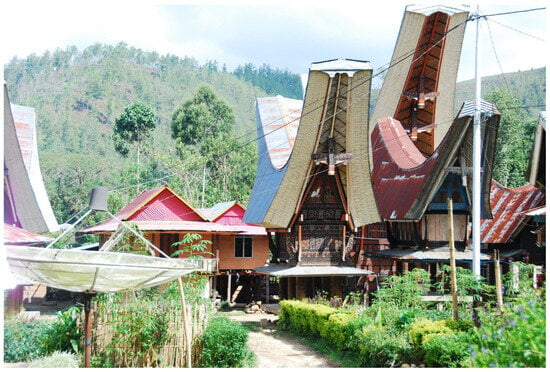

A definitive exemplar of the Austronesian ‘saddle-backed roof’ style is that of the Toraja people of Sulawesi whose economy combines rice, buffalo, pigs, tourism and coffee cloves. The roof features concave cantilevered structures protecting sloping gables that are highly ornamented, invoking nautical symbolism, a ship’s prow, but “…this association might represent…a secondary elaboration of the more fundamental connection of the pole dwelling’s floor with the deck of a boat, both being regarded as microcosmic equivalents to the Middle World, the world of humans, in a tripartite cosmos” (Figure 18) [36]. The term tongkonan refers to an ornamented ancestral seat in the Toraja houses which forms a ritual centre symbolising a higher-ranked person in the family’s bilateral kin group. A front porch of the house is for meeting and ceremony, whilst the back porch is for food production processes. If raised sufficiently, the underneath-the-house area is used for the nocturnal securing of buffaloes [37].

Figure 18.

Tongkonan houses of Toraja, Sulawesi, 2009. The pronounced saddle-backed roof is a semantic reference to boat architecture. (Photo by Fridus Steijlen, KITLV, Leiden University, Item 827955).

In her definitive book, ‘The Living House’, Roxanne Waterson wrote

Wherever we look in the archipelago, we find societies in which the word ‘house’ designates not only a physical structure, but the group kin who are living in it or who claim membership in it.[27] (p. 142)

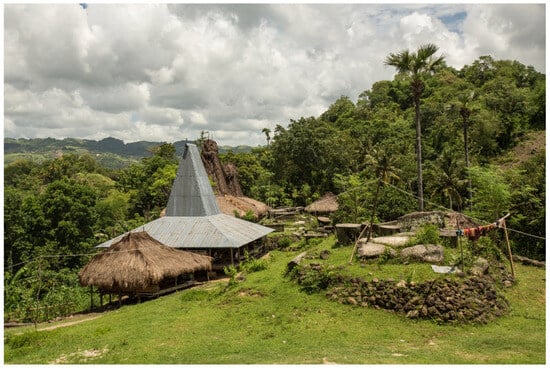

The early 21st-century houses of the Wanokakan people from south-western Sumba also contain semiotic references to ‘natural order, social status and family organisation’. A dominant feature is a tall, truncated gable tower that supplants a low-pitched pyramid roof. The base of the tower rests on four symbolic carved posts. One is the men’s post to contact the gods with offerings and prayers; the second is a men’s post for ‘shade’ while they await answers to the prayers for house and clan health; the third is a women’s post to oversee the clan’s wealth; and the fourth, a women’s post again to oversee the fire. Used together, they activate a household quadripartite order, but the posts must have root ends down and branch ends up in the typically Austronesian manner. Buffaloes’ horns may be on the tower ridge ends (male/female). Each part of the house has further anthropomorphic symbolism [38].

Nautical symbolism also remains woven into the villages of the Tanimbarese in the southeast Moluccas. For example, Figure 19 shows a Wanokakan village which contains a boat-shaped stone platform for communal meetings.

Figure 19.

Small Wanokakan village with a boat-shaped stone platform. The house is supported by four ritual columns, two for male and two for female residents, Sumba, Lesser Sunda Island, Indonesia, 2017. (Photo by Elliot Laloi).

Employing a fishing, swidden agriculture and trading economy, the Tanimbarese of Yamdena (Indonesia) viewed their houses as ships with prows pointing seawards. Villages contained a central boat-shaped stone platform (natar), used for ritual dancing. Decorative prow boards were stylised as horn-shaped finials on roof ridges. Houses had kinship names reflecting lineage generational status [39] (Figure 20 and Figure 21).

Figure 20.

Boat-shaped platform in the Tanimbarese village of Sangliat Dol, Yamdena, Indonesia. One of the houses displays horn-shaped finials. (Photographer unknown, Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, Amsterdam, TM-10000872).

Figure 21.

Contemporary use of the ship-shaped platform in the Tanimbarese village of Sangliat Dol, Yamdena, Indonesia (photographers Hendri Kaharudin and Herman Koisine) [40].

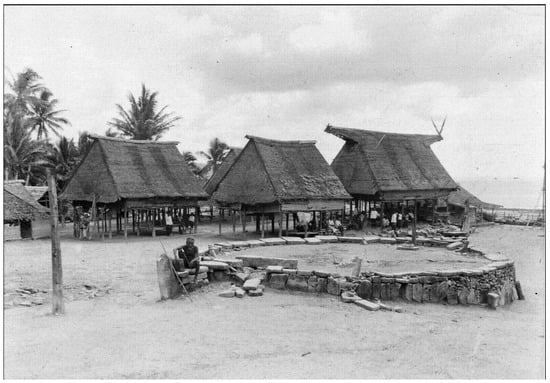

The Manggarai people of western Flores decorated the high roof peaks of their two types of communal houses with a variety of finial sculptures such as carved buffalo horns, bird heads or snake motifs. The larger type (mbaru lempang) was on an elliptical plan, accommodating up to 200 people, whilst the smaller with a conical roof (mbaru niang) was on a circular plan (Figure 22 and Figure 23). The use of a ritually significant central house post was another Austronesian feature. The Manggarai thatched roofs raked down to a low-set timber floor (no walls). Separated family sleeping compartments extended around the perimeter, each with a hearth. The smoky interiors led to the Dutch colonisers enforcing their widespread destruction, but since the late 20th century, at least several of the conical roof types have been rebuilt, as well as one elliptical type [41].

Figure 22.

Mbaru lempang communal house with elliptical plan and symbolic finial sculpture in West Manggarai, Flores, Less Sunda Island, Indonesia, c. 1915. (Photographer Charles Le Roux, Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, Amsterdam, TM-10017620).

Figure 23.

Mbaru niang with circular plan and low-set timber floor reconstructed between 2007 and 2011 in the Village of Wae Rebo, Manggarai, Flores, Lesser Sunda Islands, Indonesia. (Photo by Fiona Fleurette, 2014).

Similar Austronesian elements are to be found in exemplars from the Philippines. For example, the Torogan houses of the senior title holders of the descent groups of the Maranao people of Mindanao (Philippines) are ornately embellished with projecting carved floor beam ends, upward-flared to resemble butterfly wings (panolong), ornate roof beams (rampatan or ‘intestine of the house’), and carved buffalo horns on the front gable roof ridge (diungal). Status is further conferred with a prestigious prescriptive name for each house [42].

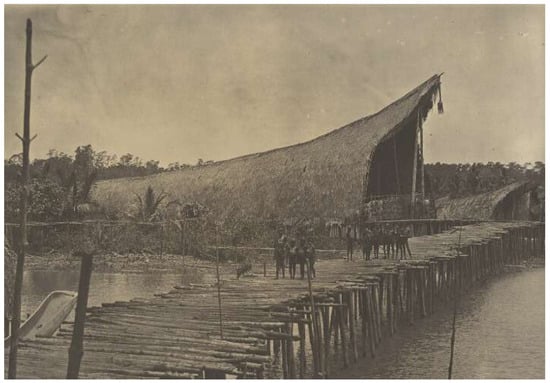

3.7. Emergence of the Longhouse Tradition

Austronesian immigrants with their metal tools, coming into contact with local groups of hunter–gatherer–fishers, seem to have catalysed the architectural innovation of the longhouse, which gradually diffused throughout Borneo, being readily adopted by the Iban, and then elsewhere throughout the eastern islands of what is now the Indonesian archipelago from Sarawak to New Guinea.

The inland spread of Austronesian peoples throughout Borneo, practising swidden cultivation, hill paddy and fishing, acculturated the longhouse as the best defensive settlement architecture. These groups such as the Iban and Dayaks usually sited themselves on river banks, and became known as upriver peoples. The longhouse design template consisted of a set of contiguous rooms, from 3 to 50, even 100, 1 for each family unit, arranged linearly as apartments, with a shared socialising and circulating corridor space adjacent, all on a post-supported timber platform (Figure 24). Guerriero, drawing on Blust, sources the longhouse institution back to the Mon Khmer speakers of highland Vietnam and southern Lao [43,44].

Figure 24.

Iban longhouse, Rejang River, Sarawak, 2008. (Photo by John Ting).

By contrast, the hunter–gatherers of Borneo, glossed collectively as Punan (and including Penan; although the Punan and Penan are often glossed together, these are two distinctly separate groups [45]), maintained a base camp and a range of temporary camps from which they targeted seasonal resources within their forest range [45] (Figure 25). In the late 1900s, government officials eventually encouraged the Punan to take up the longhouse tradition (Figure 26). This adaptive settlement pattern of base camps and temporary hunting camps had also been common among the many Aboriginal peoples of the Australian continent [22], but since colonisation, they have also undergone sedentarisation in government-provided settlements.

Figure 25.

Penan dwellings, Kelabit Highlands, Sarawak 2009: (a) temporary dwellings; (b) settlement (photos by Ben Beiske).

Figure 26.

Government-provided longhouse for the resettled Penan from Mulu National Park on the Melinau River, Sarawak, 2015. (Photo by John Mason).

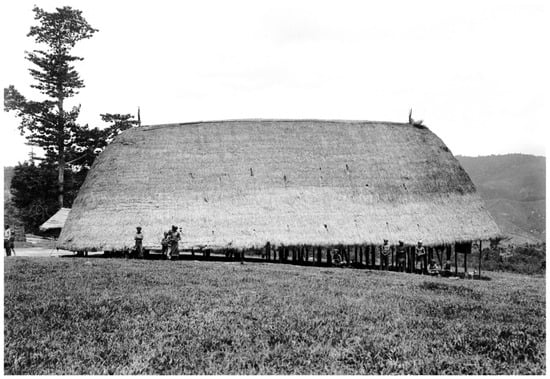

3.8. New Guinea Longhouses

The longhouse tradition diffused and also came to prevail in parts of New Guinea with a concentration on the Papuan coastal region from the Fly River to the Vailala River. An extensive diversity of construction types and ritual uses reflected different cultural and environmental circumstances. The most elaborate were the ravi or men’s ceremonial houses which housed ceremonial and artistic activities. For example, the Purari River delta region was dominated by the “very tall and long, steeply pitched, bow-roofed, tilted-ridged, tapering longhouses…”, reflecting the Austronesian tradition which spread around the coastal areas (Figure 27). Apart from continuing examples at Mount Bosavi, this architectural tradition ceased in this region during the mid-20th century due to colonial influences [46].

Figure 27.

Kau Ravi, Kaimare Village, Gulf Province, Papua New Guinea, 1922 (photo by Frank Hurley, NLA Call Number PIC Drawer H42 P590 #P590/29).

However on the southern coast of Indonesian Papua, the riverine Asmat communities have maintained their ceremonial men’s longhouse traditions. The jeu “is the centre of Asmat social life, being at once a meeting house, the abode of young bachelors, the ceremonial centre and the religious assembly building which houses ancestral carvings” (Figure 28). The Atsj jeu contains carved posts of ancestors who are believed to protect the residents from malevolent spirits [47].

Figure 28.

Asmat ceremonial house (jeu), Syuru village, Agats, West Papua, 2009. (Photo by David Stanley).

The Iatmul of the Sepik River in the north also continue their men’s longhouse (ngeko) tradition [48], as do the Sawos of the Sepik, who employed upward-curving gable ends on which bird sculptures are mounted (Figure 29 and Figure 30) [49].

Figure 29.

Iatmul men’s house with bird sculpture finial, Tambunum village, Sepik River, Papua New Guinea, 2014. (Photo by Eksilverman).

Figure 30.

Saddle-shaped Austronesian type roof with finial on Sawos Men’s House, Sepik Region, Papua New Guinea. (Photo by Christian Coiffier).

3.9. The Austronesian Progression into the Pacific

The divergence of Austronesian groups into new environments was marked by significant changes that are evident from archaeological and linguistic evidence [19] (p. 57). The Austronesian house elements were also subject to change, and as the migrations progressed eastwards, not all of the above Austronesian house elements are so clearly evident in recurring patterns:

In the eastern, Polynesian parts of the Austronesian world there are so many conspicuous contrasts with the house types of the Indonesian archipelago that it is difficult to find convincing indications for more than a very general common architectural tradition. This refers not only to matters of design but also to basic disparities in construction details—intricate mortise and tenon techniques in the west, binding in the east, for instance.[37] (p. 19)

Local diffusion of cultural traits and influences arising from the Austronesian migrations included agricultural practices, the linguistic absorption of Austronesian lexicon, the maritime technologies of the outrigger canoes, and the distinctive ‘Lapita style’ pottery characterised by incised and dentate stamped decorative features, but most importantly, sedentary coastal settlements with houses on piles, together with inland fortified villages and hamlets [19] (p. 57).

3.10. Examples of Economic and Political Adaptation and Diversification

It should be noted at this point in the analysis that this model of three dominant migrations into the region is exceedingly coarse-grained, and that any local or sub-regional study of migration, intermixing and cultural influence and change can be very complex (and beyond detailed treatment in this brief summary). For example, in the deep forests of southern Sumatra, small bands of the Kubu hunting and gathering people have survived right into the early 21st century, whereas the original hunter–gatherers would have first occupied the coastal areas and incorporated fishing and sea animal hunting into their hybrid economy. Western Sumatra was much later occupied by Austronesian speakers three to four thousand years ago, arriving from Borneo and the Philippines. From the 7th century AD, a Buddhist kingdom was established centring on Palembang, and by the 13th century, Islam had become well established in north Sumatra and then diffused eastwards eventually into Java during the 15th century. The Orang Laut or ‘sea people’ became dominant along the Sumatran east coast, but this area was further transformed by the Dutch from the late 19th century who imported Javanese, Indian and Chinese plantation labourers. Modern Indonesian nationalism was to follow, which also impacted architectural traditions [50].

In terms of understanding the differential evolution of cultural types since the early Austronesian occupations, Gibson has produced a useful comparative analysis of two contrasting types: a self-isolated, highly egalitarian, highland-forest group practising shifting cultivation (the Buid of Mindoro in the Philippines), and a lowland rice-farming and outwardly trading group with a hierarchical polity, kingship and a world religion (the Makassar of South Sulawesi, Indonesia) [51]. Despite the contrast in political systems and values of acquiring material wealth and status, both groups maintain a cultural system embracing core Austronesian elements including the belief in “a gendered cosmos inhabited by a series of parallel societies composed of animal, human and spirit subjects” distributed within the vertical spaces of the house categorised into Upper World (roof space), Middle World (normal floor level) and Under World (below floor) and between which certain agents could communicate “by means of specialised training, spirit familiars, vehicles and portals.” [51] (pp. 235, 237, 243).

They represented in a heightened form a contrast found throughout Southeast Asia between the hierarchical polities of the lowlands that were based on irrigated rice, kingship, and a world religion, and the egalitarian societies of the highlands that were based on shifting cultivation, kinship and an indigenous religion.[51] (p. 236)

3.11. The Cultures of Oceania

Most of the Polynesian communities generally experience a benign tropical climate, influencing externally oriented living patterns. As a result, an architectural feature that evolved throughout Polynesian cultures was the design and accompanying cognate behavioural practice of ritual oratory exchanges when visitors arrived, in a designated space known as the marae or malae (or similar), a ceremonial approach and greeting place (see Figure 31). This space, articulated by surrounding architectural elements, was considered “as important and tapu (sacred) as the elements themselves” [52] (p. 414). The outdoor meeting space predominates and indoor activities occur in separate buildings, a deconstructed architectural pattern.

Figure 31.

Taputapuatea marae, an ancient marae (stone platform) on the island of Raiatea, French Polynesia. A place of communal rituals and political meetings. (Photo by Michel-Georges Bernard, c. 2000).

In eastern Polynesia and Aotearoa, the outdoor meeting, ritual and decision-making space, known as the malae or marae, and sometimes situated on a platform, has significant longevity (e.g., Figure 31). In Aotearoa (New Zealand), which experiences a temperate climate, an associated building evolved adjacent to the marae in the 1840s as a traditional response to colonisation: the wharanui or meeting house for discussion of tribal issues of political importance as well as ritual greetings, for use particularly in inclement weather. In the classical type that emerged, the genealogy of the iwi (local tribe) is sculpted as faces on timber columns and other structural and decorative carved components symbolise the ancestor(s) who colonised the locale during the first canoe immigrations [53,54].

The Austronesian colonisers of the Pacific brought expertise in nautical architecture (timber components connected with fibre string or rope bindings) which they technologically and symbolically adapted to the land to maintain diverse hybrid economies based on hunting, gathering, fishing, agriculture and animal husbandry. The emergent timber architecture, all bound together, was mostly derived from plant products.

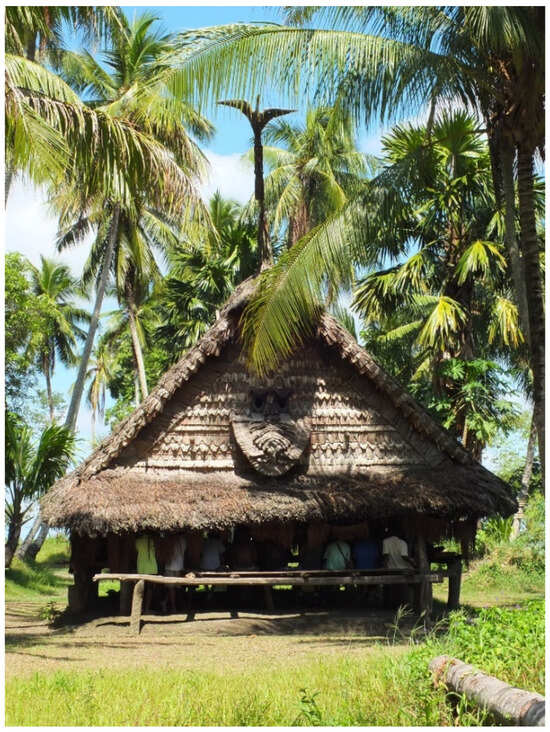

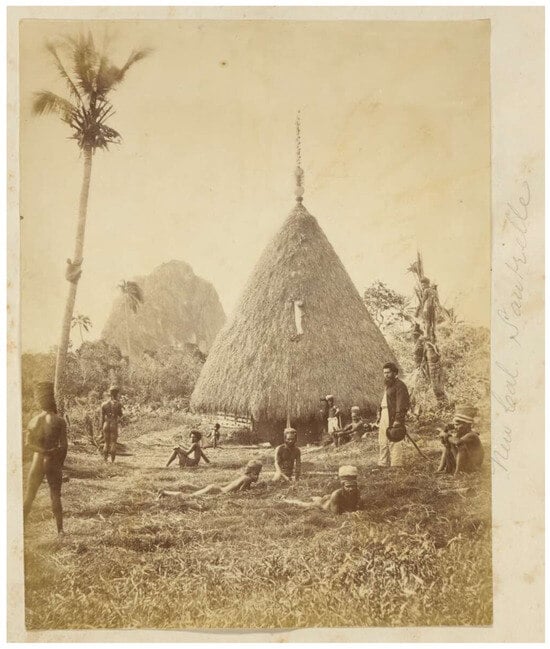

One surviving Melanesian exemplar is the Kanak conical chief’s house in New Caledonia which, after a colonial suppression followed by a revival, is the inspiration for the famous Tjibao Cultural Centre (architect Renzo Piano) in Noumea (Figure 32). This exemplar of the chief’s house (grande case) also replicated the Austronesian principle of linking the local descent group or clan via the senior persons (the chiefs) to the spirits of clan ancestors embodied in the conical roof apex and expressed in the apex finial (Figure 33) [52] (p. 414).

Figure 32.

A pavilion at the Tjibaou Cultural Centre, whose design was inspired by the Kanak grande case (Photograph by author, 2019).

Figure 33.

A ‘grande case’, New Caledonia, c. 1870; the roof apex and its finial represent clan ancestors. (Photo by Allan Hughan, NLA Call Number PIC/8057/6 LOC Album 474).

To spiritually activate the symbolic architectural elements of the Kanak chief’s house (door jambs, central post—the chief, peripheral posts—male elders council and finial), an awakening of life from the land was performed on the named earth foundation platform (tertre) which had an associated genealogy, and which was ritually achieved, amongst the northern groups for example, by masters of land tenure, magic, and women’s wisdom who collectively buried energised magical objects in the platform [55] (p. 282).

An analogy can be discerned between the Polynesian marae and the central oratory space of the Kanak village or hamlet on New Caledonia. The house at one end of the space is that of the next bloodline chief/s, whilst the current chief’s conical house is at the opposite end, with the sociopolitical space in between defined by parallel peripheral rows of sacred Araucaria columnaris pines. Visitors to the chief were housed at the next bloodline chief’s house who brought them along the corridor with appropriate oratory protocols. The alley space symbolised the realm of the forest beyond [55] (pp. 285, 294) [56].

A number of Austronesian case studies also illustrate the bringing of lithic technology and stone architecture and engineering, as documented by Miksic et al. [52], e.g., the Micronesian settlement Nan Madol, located on the coast of Pohnpei Island (Figure 34). Megalithic stone construction from c. 1400 to 1500 is arranged to form 90 artificial islands, supporting “basalt-built houses and tombs, and connected by a series of channels.” Rafts were used to transport these basalt blocks which were then manipulated into place with the aid of pulleys and ropes [52] (pp. 413–414). European technologies were increasingly acculturated from the 1500s to develop the Micronesian and Polynesian megalithic stone construction methods and achievements [52] (p. 414).

Figure 34.

Ancient Nan Madoll site, Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia, 2014. (Photo by Patrick Nunn).

Brown, writing about the elevated roof forms of the Pacific Austronesian populations, states the following:

The elaborately lashed and painted rafters, purlins and tie structures that supported these thatched roofs were associated with ancestors and deities, probably following the same principles employed in megalithic structures, namely that height was associated with social and spiritual leadership. Closer to the floor, columns were often associated with recent or present-day leaders and indicated their internal seating positions.[52] (p. 416)

The last point indicates the significance of sociospatial structures in the organisation of Pasifika settlements.

The house, as a physical entity and as a cultural category, has the capacity to provide social continuity. The memory of a succession of houses, or of a succession within one house, can be an index of important events in the past. Equally important is the role of the house as a repository of ancestral objects that provide physical evidence of a specific continuity with the past. It is these objects stored within the house that are a particular focus in asserting continuity with the past.[6] (p. 14)

To support the maintenance of these traditions, Māori cultural renaissance during the 20th and 21st centuries has brought a strengthening of marae significance and wharanui maintenance as well as the advent of urban marae as venues for urban identity and resistance for those away from homelands (Figure 35) [53,54].

Figure 35.

The knighting of Māori Elder Sir Hec Busby at the meeting house Te Whare Rūnanga in Waitangi, 2009. Te Whare Rūnanga was built in 1940 to commemorate the centenary of the signing of the Waitangi treaty and contains carvings representing iwi from across New Zealand. It is used regularly for important political and cultural events of national significance. (Photo by New Zealand Government, Office of the Governor-General).

A recent example of modernised urban Maori marae architecture is the Taumata o Kupe building on the Te Mahurehure Marae in Auckland, named after and celebrating Kupe, “the legendary Polynesian navigator and explorer acknowledged by some iwi [tribes] as the discoverer of Aotearoa” and who catalysed the migratory canoe voyages. Its sweeping organic form and glass panel walls symbolise sails, stays and a rudder [57] (pp. 2, 3).

3.12. The Sea Gypsies and Maritime Peoples

The Sea Gypsies of Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines are often glossed as Bajau Laut or simply Bajau. In the Sulu Archipelago of the Philippines, local groups (Tausug, Samal) are Muslim but simultaneously maintain their ‘old nativistic “pagan” religion’. The nuclear families either live exclusively on a house boat, or have both a house boat and a coastal house built on a timber platform supported on piles in protected waters (Figure 36 and Figure 37). However, during storms, safety is preferentially sought in the boat rather than the house. Seasonal marine boat movement patterns are dictated by local fish school behaviours. Houses are believed to be occupied by ancestral spirits, so much so that nails cannot be used for fear of injuring the spirits [58].

Figure 36.

Bajau Laut house boat, 2009. (Photo by Torben Venning).

Figure 37.

Bajau Laut stilt houses off the coast of Borneo, 2010. (Photo by Torben Venning).

A larger type of settlement, the water village on platforms supported by piles, that evolved on parts of the Borneo coast was established by maritime-oriented groups, e.g., the Bajau Laut off the Sabah coast. The largest such settlement is that of Kampong Ayer in Borneo, developed over 1300 years (Figure 38). Each water village is made up of a set of inter-married clans, arranged sociospatially but also according to occupation types, e.g., traders, fishermen, craftsmen, and headmen. In the late 20th century, Kampong Ayer had grown to 5000 houses with 80,000 inhabitants, incorporating schools, mosques, clinics and even fire brigades, but much material acculturation is evident [59,60].

Figure 38.

Part of Kampung Ayer, Brunei, said to be the largest water village in the world, 2009. (Photo by Bernard Spragg).

There is also relatively recent evidence that the Austronesian peoples also built such water villages as they settled through parts of Oceania. Felgath showed from an in-depth archaeological study in the Solomon Islands (at Roviana Lagoon, New Georgia), as well as from other studies in the archaeological literature, that the distribution of Austronesian settlements along coastlines in Near Oceania (encompassing the Solomon Islands, New Britain, Santa Cruz Islands, Bismark Archipelago) was probably far denser than the recorded exemplars indicated [61] (pp. 313, 503). He argued that such settlements were platform villages and associated fishing platforms on piles in the inter-tidal zone whose archaeological remains, including Lapita pottery shards, were masked in marine sediments, hence their failure to be readily detected by archaeologists to date. Falling sea levels in the late Holocene were a complicating factor in his analysis, contributing to this gap in the archaeological record.

3.13. The Coming of the Third Wave of Colonisers

A third set of influences was then introduced and overlaid on these first two migratory waves over mainly the last millennia. Parts of modern-day Indonesia came into contact with Hindu, Muslim and Buddhist cultures from at least the 10th century. Stabilisation occurred during the period of the Majapahit Empire (1293–c1527), an Indianized kingdom centred in eastern Java, and dominating the Malay Peninsula and the Philippines. The cash economy was introduced based on rice cultivation and trade. The Majapahit architects mastered the use of brick in temples where Buddhism, Shaivism and Vaishnavism were practised.

Starting in the 1400s, but intensifying in the 1700s and 1800s, European colonisers arrived from Portugal, Holland, Spain, England, and Germany, together with their various influences on local forms of vernacular architecture. Entry negotiations had to occur with another set of preceding colonisers from China, India and Arabia. The influx of cultural ideas and syncretic influences from these cultural groups arrived through port cities, resulting in fusions with local construction traditions of palaces, forts, shops, temples and gardens [52] (pp. 407–408). The Micronesians also employed European technologies for their megalithic stone engineering and architectural developments [52] (p. 414).

Despite the carving up of Oceania into European colonies during the 19th century and the imperial control of colonised populations, the movement of Polynesian people resumed in the late 20th century with the advent of jet aeroplane travel and foreign seasonal labour schemes. A process of transnational migration has accelerated into the early 21st century with Polynesian people taking on a collective identity as ‘Pasifika’ and settling in selected cities in Australia, New Zealand, New Caledonia and the USA, in what has been termed the ‘New Polynesian Triangle’ [62]. Kinship connections and social capital are maintained in a pattern of circular mobility. The new settlers take aspects of their culture (including material culture) into their new houses and send obligatory remittances back to home communities, including in the form of western building components (e.g., [63]). Similar but not identical mobility patterns are occurring in Micronesia (e.g., [64]) and Melanesia (e.g., [65]).

The European colonists also imposed policies of cultural and political change on their Indigenous populations. Not the least of these changes were those brought by Christian missionaries. This resulted in sedentarised villages for Indigenous populations in many cases, facilitating the conversion of such people into regular church attendants and devotees. However, in certain nations, suppressive policies were lifted in the mid or late 20th century, catalysing cultural revitalisation movements and the revival or re-invention of architectural traditions, some of which are still ongoing. Contemporary researchers address the architectural results of these various determinants and processes of cultural change and their hybrid results.

An example of an urban house heavily influenced from the 1500s by colonial occupations is the Balayage na tabla (‘house of wood’) of the people of Visayan Islands of the Philippines, in which Austronesian traditions have been overlain with Spanish, Chinese, American and then Japanese influences (see Figure 39). Key architectural features are hipped gable roofs whose cladding transformed from traditional thatch to clay tiles (Chinese), to galvanised iron (USA), sliding windows made up of timber louvres and panes of capos shell (Placuna placenta) or glass, decorative fretwork (Art Deco and Art Nouveau), and many local floral and planetary references. However, the installation, composition, site orientation and numbers of architectural elements remain strongly controlled by animistic and Catholic beliefs and rules related to numerology, good and bad fortune, and the warding off of evil spirits [66]. Bedrooms may contain sacra and images for Catholic processions.

Figure 39.

The Clarin House, an exemplar of Bahay na bato at kahoy (house of stone and wood) with thatched nipa roof, sliding timber louvre panels and shell panes, Bohol, Visayan Islands, Philippines, built c. 1840. (Photo by Erik Akpedonu, 2009).

4. Discussion

It should be noted that this diffusion model of three dominant migratory waves into the region is exceedingly coarse-grained, and that any local or sub-regional study of migration, intermixing and cultural influence and change can be very complex. For example, there are many combinations and permutations of the Austronesian house elements throughout the study region. They seldom all occur in one exemplar and the number of identifiable elements generally decreases further to the east of the study region [31] (p. 19). The diversity indicates differences in styles of cultural adaptation to particular habitats and socioeconomic transformations. This has resulted in a diversity of settlement types which encompass: water settlements (coastal), terraced settlements, agriculturalists’ villages, either permanent in wet fields (paddy) or moving every few generations (swidden), riverbank settlements, longhouse/multi-familial dwellings, dispersed detached dwellings, and the temporarily occupied campsites of hunter–gatherers.

An earlier passage in this manuscript dealt with the possible leadership processes of how founder groups established navigational knowledge, solidarity and motivation to persuade their group to migrate and colonise new island habitats. However there is a need to consider possible further understandings of other relevant matters, such as what did people bring with them (e.g., technologies, shelter types), how did they engage in place-making when they arrived drawing on particular selective cultural elements from their former habitat context, how did they create a stable social structure upon their arrival sufficient to overcome the many unexpected adversities, and were the original charismatic leadership capacities of the founders which bound people together able to be sustained beyond one generation. There are many global sources of ideas on these critical questions in multiple halls of many libraries, not to mention social media (for example ‘The Vikings’ television series). However here I would like to direct attention to the many excellent research case studies being produced for our study region by researchers of contemporary or recent diasporic groups, particularly those moving from the Pacific to New Zealand, Australia and the USA. This is because it is not unreasonable to hypothesise that these same human processes have continued to recur in probably more or less similar ways to what they always have, in past millennia.

5. Conclusions and Significances

What can be concluded is that extant examples of traditional houses and shelters are still identifiable throughout the study region, including for hunter–gatherers, but have largely disappeared in many parts as well, due to the imposed changes of the colonisers and global change influences in more recent decades. However even with a limited number of examples, it can be demonstrated that there is an ongoing resilience amongst many contemporary groups (noting the selection herein of the many post-2000 case study images) to retain particular aspects of their architectural traditions, albeit in certain cases necessarily adapted due to cultural disrupters, environmental transformations (e.g., deforestation), and technological and material changes brought about by modernisation processes from the industrial through to the globalisation eras.

Rapid socioeconomic and political changes can bring major house changes, for example, in Indonesia, where post-Suharto regional autonomy triggered the revitalisation of regional styles in public buildings to emphasise local identity and cultural heritage. However contemporary events can also catalyse the resurgence of architectural traditions. Such events include communal reconstruction projects after natural disasters, official conservation projects with changing government heritage policies, villages and house exemplars built to attract tourism economy, and the referencing of tradition into iconic architectural projects by architects.

There are various examples of revivals of vernacular structural technologies in response to the earthquake-proofing of buildings following major seismic events. One example is a recent Maori project that responded to the 2011 Christchurch earthquakes. The subsequent government changes to national building by-laws prompted an independent trans-disciplinary team to conduct a survey of the most significant Maori building type, the wharanui or community building. A database has been prepared of some 800 case studies across New Zealand on marae or community meeting places. This massive cultural heritage survey aims to develop protective engineering renovations and/or strategies for these culturally significant buildings [67].

It is possible to focus on those architectural elements of high value to cultural groups, which they consider worthy of retention, adaption and maintenance. These architectural elements may be either material and/or non-material. From my editing analysis of the EVAW2 volume, it can also be concluded that recurring semiotic references can be categorised as follows. First, there are often gendered spaces within a building, and also the symbolism of gendered architectural elements. Kinship symbolism can also be significant. The house is often considered an animate entity linked to ancestral power and affecting residents’ well-being despite the fusions arising from the acculturation and diffusions of world religions (Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Christianity).

Other types of recurring symbolism are anthropomorphic, animal symbolism and nautical references. Hierarchical symbolisms may occur at different heights in the house, including the Austronesian tripartite symbolism.

The survival rate of indigenous structures is strongest on isolated islands or where migrant wealth has been channelled into the renewal of original houses. In the case of the latter, in eastern Indonesia, the clan or lineage house (rumah adat) and sometimes origin villages (Kampong Lama), which have ritual significance, are preserved, but other houses have been replaced with modern construction. Here people regularly trace descent from houses and their kinship allegiances. Lineage symbolism in houses may be patrilineal or matrilineal depending on the local cultural practices of land tenure, governance, property inheritance and religious beliefs. The ‘senior house’ may be characterised as a ‘wife-giver’ house whereas outer ‘junior houses’ may be ‘wife takers’.

There is in the indigenous religions of the Archipelago a widely shared concept of a vital force which suffuses and animates the universe. This force has been variously labelled in the literature as ‘spirit’, ‘soul-stuff’, ‘essence’, ‘vital force’, ‘cosmic energy’, and so on, while in Malay and Indonesian languages it is widely known by the word semangat or its cognates. It is this view of the universe which has been called ‘animism’ by Western writers, some of whom have drawn comparisons between semangat and the Polynesian concept of mana.[27] (p. 115)

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Memmott, P.; Kane, J. Australasia and Oceania. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Memmott, P.; Ting, J.; O’Rourke, T.; Vellinga, M. (Eds.) Design and the Vernacular: Interpretations for Contemporary Architectural Practice and Theory; Bloombury: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bellwood, P.; Chambers, G.; Ross, M.; Hung, H. Are ‘Cultures’ Inherited? Multidisciplinary Perspectives on the Origins and Migrations of Austronesian-Speaking Peoples Prior to 1000 BC. In Investigating Archaeological Cultures: Material Culture, Variability, and Transmission; Roberts, B.W., Linden, M.V., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 321–354. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, J. Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Chio, J. Visual anthropology. In The Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology; Stein, F., Ed.; (2021) 2023. Available online: https://www.anthroencyclopedia.com/entry/visual-anthropology (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Fox, J.J. (Ed.) Inside Austronesian Houses: Perspectives on Domestic Designs for Living; Australian National University Press: Canberra, Australia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kealy, S.; Lous, J.; O’Connor, S. Reconstructing Palaeography and Inter-island Visibility in the Wallacean Archipelago During the Likely Period of Sahul Colonization, 65–45,000 Years Ago. Archaeol. Prospect. 2017, 24, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, S.; Hiscock, P. The Peopling of Sahul and Near Oceania. In The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Oceania; Hunt, T.L., Cochrane, E.E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 26–47. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsell, J.B. The Recalibration of a Paradigm for the First Peopling of Greater Australia. In Sunda and Sahul: Prehistoric Studies in Southeast Asia, Melanesia, and Australia; Allen, J., Golson, J., Jones, R., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1977; pp. 113–167. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, S.A.; White, D.A.; Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Saltré, F.; Williams, A.N.; Beaman, R.J.; Bird, M.I.; Ulm, S. Landscape rules predict optimal super-highways for the first peopling of Sahul. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabtree, S.A.; Williams, A.; Bradshaw, C.; White, D.; Saltré, F.; Ulm, S. We mapped the ‘super-highways’ the First Australians used to cross the ancient land. The Conversation, 30 April 2021. Available online: https://theconversation.com/we-mapped-the-super-highways-the-first-australians-used-to-cross-the-ancient-land-154263 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- McCarthy, F.D. “Trade” in Aboriginal Australia, and “Trade” relationships with Torres Strait, New Guinea and Malaya. Oceania 1939, 10, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Crabtree, S.A.; White, D.A.; Ulm, S.; Bird, M.I.; Williams, A.N.; Saltré, F. Directionally supervised cellular automaton for the initial peopling of Sahul. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2023, 303, 107971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.N.; Ulm, S.; Cook, A.R.; Langley, M.C.; Collard, M. Human refugia in Australia during the Last glacial maximum and Terminal Pleistocene: A geospatial analysis of the 25–12 ka Australian archaeological record. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 4612–4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frachetti, M.; Smith, C.; Traub, C.M.; Williams, T. Nomadic ecology shaped the highland geography of Asia’s Silk Roads. Nature 2017, 543, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Norman, K.; Ulm, S.; Williams, A.N.; Clarkson, C.; Chadœuf, J.; Lin, S.C.; Jacobs, Z.; Roberts, R.G.; Bird, M.I.; et al. Stochastic models support rapid peopling of Late Pleistocene Sahul. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrell, J.E. Think Globally, Act Locally [Review of the book Eden in the East: The Drowned Continent of Southeast Asia, by S. Oppenheimer]. Curr. Anthropol. 1999, 40, 556. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, R.; Buckly, H.; Jacomb, C.; Matisoo-Smith, E. Mass Migration and the Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand. J. World Prehist. 2017, 30, 351–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latinis, D.K. The Development of subsistence system models for Island Southeast Asia and Near Oceania: The nature and role of arboriculture and arboreal-based economies. World Archaeol. 2000, 32, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, B. Dark Emu Seeds: Agriculture or Accident? Magabala Books: Broome, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, P.; Walshe, K. Farmers or Hunter-Gatherers? The Dark Emu Debate; Melbourne University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Memmott, P. Gunyah, Goondie and Wurley, 2nd ed.; Thames and Hudson: Port Melbourne, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Loupis, G. Architecture of the Central Highlands of Papau New Guinea, Traditional Technology Series No. 3; LikLik Buk Information Centre: Lae, Papua New Guinea, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- David, B.; Delannoy, J.-J. The remarkable Nawarla Gabarnmang. In Gunyah, Goondie and Wurley, 2nd ed.; Memmott, P., Ed.; Thames and Hudson: Port Melbourne, Australia, 2022; pp. 336–339. [Google Scholar]

- Porath, N. Semang: Hunter-gatherer lean-to. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- O’Rourke, T. Adaptive uses of traditional windbreaks and bough sheds for Indigenous housing in Australia. In Design and the Vernacular: Interpretations for Contemporary Architectural Practice and Theory; Memmott, P., Ting, J., O’Rourke, T., Vellinga, M., Eds.; Bloombury: London, UK, 2024; pp. 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Waterson, R. The Living House: An Anthropology of Architecture in South-East Asia, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Singapore, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Encarnacion-Tan, R.; Zialcita, F.N. Philippines. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Blust, R. The Austronesian Homeland and Dispersal. Annu. Rev. of Linguist. 2019, 5, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.; Wyeth, H.M. We the Voyagers. Part One: Our Vaka (Lata’s Children); Part Two: Our Moana; George, M., H.M. Wyeth, Dirs.; Vaka Taumako Project, Prod., 2020 [film].

- Schefold, R. The Southeast Asian-type house: Common features and local transformations of an ancient architectural tradition. In Indonesian Houses: Tradition and Transformation in Vernacular Architecture; Schefold, R., Domenig, G., Nas, P., Eds.; Singapore University Press: Singapore, 2004; pp. 19–60. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.J. The Malay House: Rediscovering Malaysia’s Indigenous Shelter System; Institut Masyarakat: Kuala Lampur, Malaysia, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Memmott, P. Gunyah, Goondie + Wurley: The Aboriginal Architecture of Australia, 1st ed.; University of Queensland Press: St Lucia, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, G.; Ting, J. Malay Peninsula. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Tang, S.T. The Million-Ringgit Rumah Bugis @ Pontian, Johor. ImEmily 4 October 2014. Available online: https://www.imemily.com/2014/10/the-million-ringgit-rumah-bugis-pontian.html (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Schefold, R. Sa’dan Toraja: Saddle Roof. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Schefold, R. Sa’dan Toraja. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Mross, J.; Doubrawa, I. Wanokakan. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Waterson, R.; De Jong, N. Tanimbarese. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Kaharudin, H.A.F.; Wicaksono, G.; Azis, F.; Kealy, S.; Sari, D.M.; Ririmasse, M.N.R.; O’Connor, S. Living Seaward: Maritime Cosmology and the Contemporary Significance of Natar Fampompar, a Stone Boat Ceremonial Structure in the Village of Sangliat Dol, Tanimbar Islands. Ethnoarchaeology 2024, 16, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterson, R.; Doubrawa, I. Manggarai. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Peralta, J. Maranao. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Guerriero, A. Borneo. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Blust, R. Longhouses and nomadism: Is there a connection? Borneo Res. Bull. 2016, 46, 194–220. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, P.; Memmott, P.; Guerreiro, A.; Kane, J. Penan/Punan. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Fowler, M.; Craig, B. Papuan Gulf: Longhouses. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Boylan, C. Asmat: Jeu. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Coiffier, C. Iatmul. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Coiffier, C. Sawos. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Waterson, R.; Achmadi, A. Indonesia, West. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Gibson, T. From Tribal Hut to Royal Palace: The Dialectic of Equality and Hierarchy in Austronesian Southeast Asia. Anthropol. Forum 2019, 29, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miksic, J.N.; Memmott, P.; Brown, D. Southeast Asia, Australia and Oceania, 1400–1780. In Sir Banister Fletcher’s Global History of Architecture; Fraser, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 406–422. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, M.; Brown, D. Maori. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Brown, D. Maori: Architecture Revitalisation. In Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, 2nd ed.; Vellinga, M., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in press.

- Lagarde, L.; Gony, Y. From cultural symbol to societal sign: The question of the Kanak traditional house in present-day New Caledonia. In Design and the Vernacular: Interpretations for Contemporary Architectural Practice and Theory; Memmott, P., Ting, J., O’Rourke, T., Vellinga, M., Eds.; Bloombury: London, UK, 2024; pp. 281–294. [Google Scholar]