A Spatial Spectrum Framework for Age-Friendly Environments: Integrating Docility and Life Space Concepts

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

1.2. Research Objectives and Distinctiveness

1.3. Research Questions & Methodological Approach

- How should the design of spatial environments be linked to functional decline in older adults?

- How can the Docility Hypothesis and Life Space Theory be jointly applied across diverse spatial scales?

- From the perspective of AIC, how can a comprehensive and adaptable design framework for age-friendly environments—spanning home, community, and urban spaces—be conceptualized?

1.4. Definitions of Key Terms

- Environmental GerontologyA multidisciplinary field that examines the interactions between older adults and their environments, aiming to enhance quality of life in later life. It integrates physical and social environmental factors with the psychological and functional characteristics of aging [6].

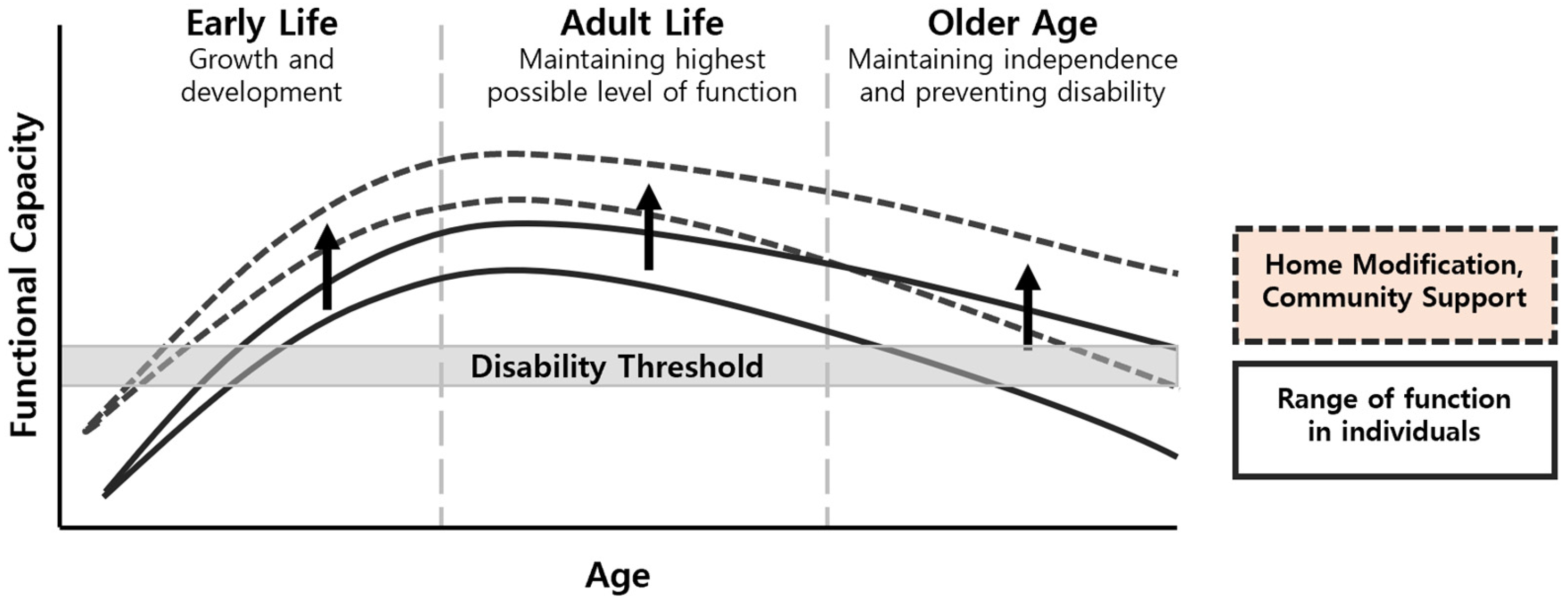

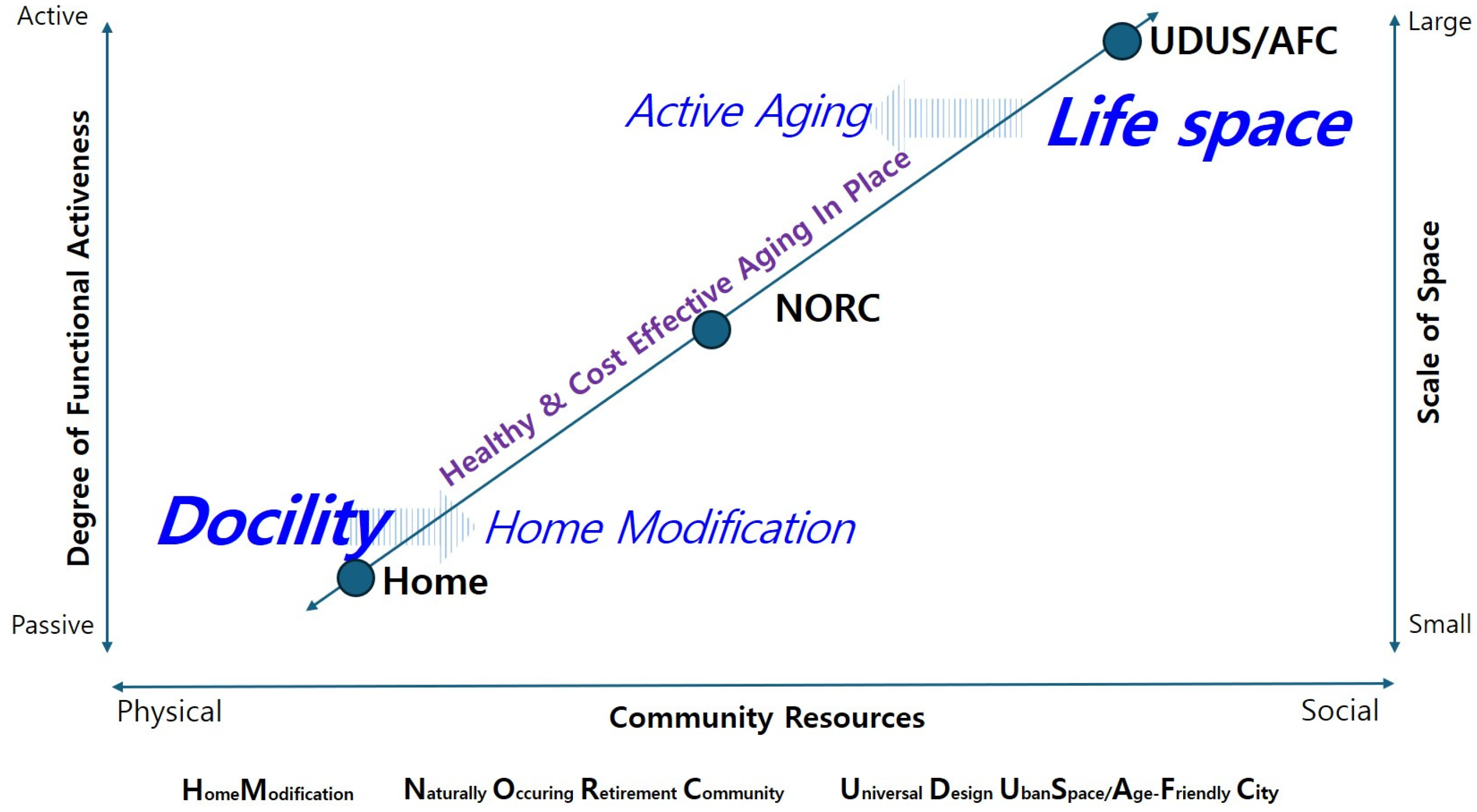

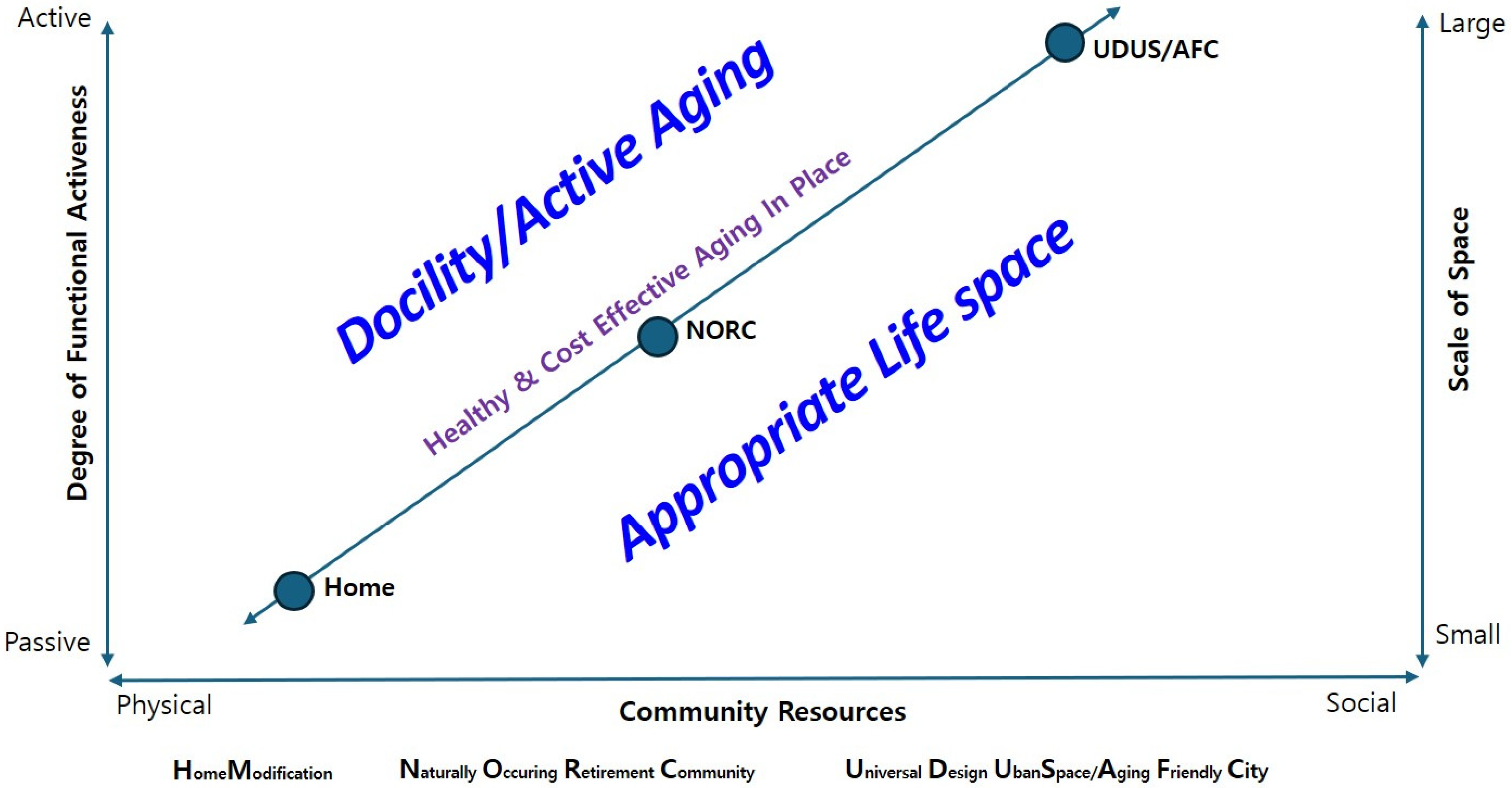

- Docility HypothesisProposed by Lawton [7], this hypothesis argues that individuals with lower functional competence are more sensitive to environmental conditions. It underscores the importance of environmental adaptation in maintaining autonomy and independence among older adults.

- Life Space Theory

- SPOT Framework (Space, Place, Opportunity, Time)Developed by Wahl and Lang [8], this framework interprets the life spaces of older adults by integrating physical locations with opportunities and temporal dimensions, thereby linking spatial context to lived experiences.

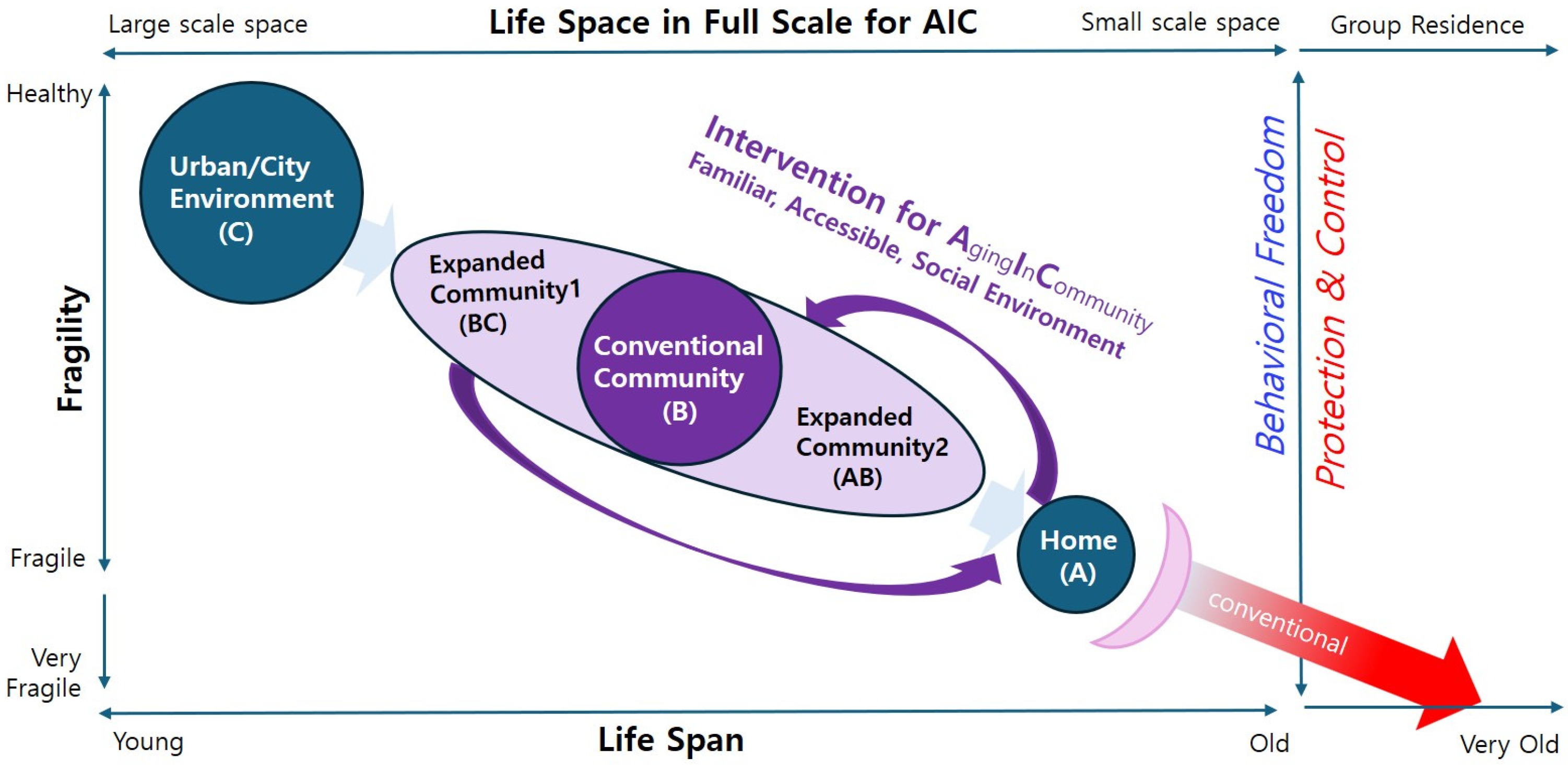

- Aging in Community (AIC)A concept that extends beyond Aging in Place by emphasizing dignity, vitality, and social participation through community-based support systems [9].

- Contextual GerontologyAn integrative approach that situates older adults within temporal, spatial, and social contexts. It provides a framework for analyzing autonomy, functional abilities, and the fit between individuals and their environments [5].

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Conceptual Overview

2.2. Life Space Theory

2.3. Integrative Theories (CODA, SPOT, Contextual Gerontology, AIC)

2.4. Theoretical Gap

2.5. Korean Contextual Background

3. Research Framework and Method

3.1. Methodological Overview

- Aging in Place (AIP): Housing modification strategies that enable older adults to remain in their homes despite functional decline.

- Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities (NORC): Residential clusters where older adults live independently but benefit from shared services and social ties.

- Age-Friendly Cities (AFC): Urban-level initiatives coordinated by the World Health Organization to enhance accessibility, participation, and safety for all generations.

- (1)

- Spatial Strategies Based on Housing Modification

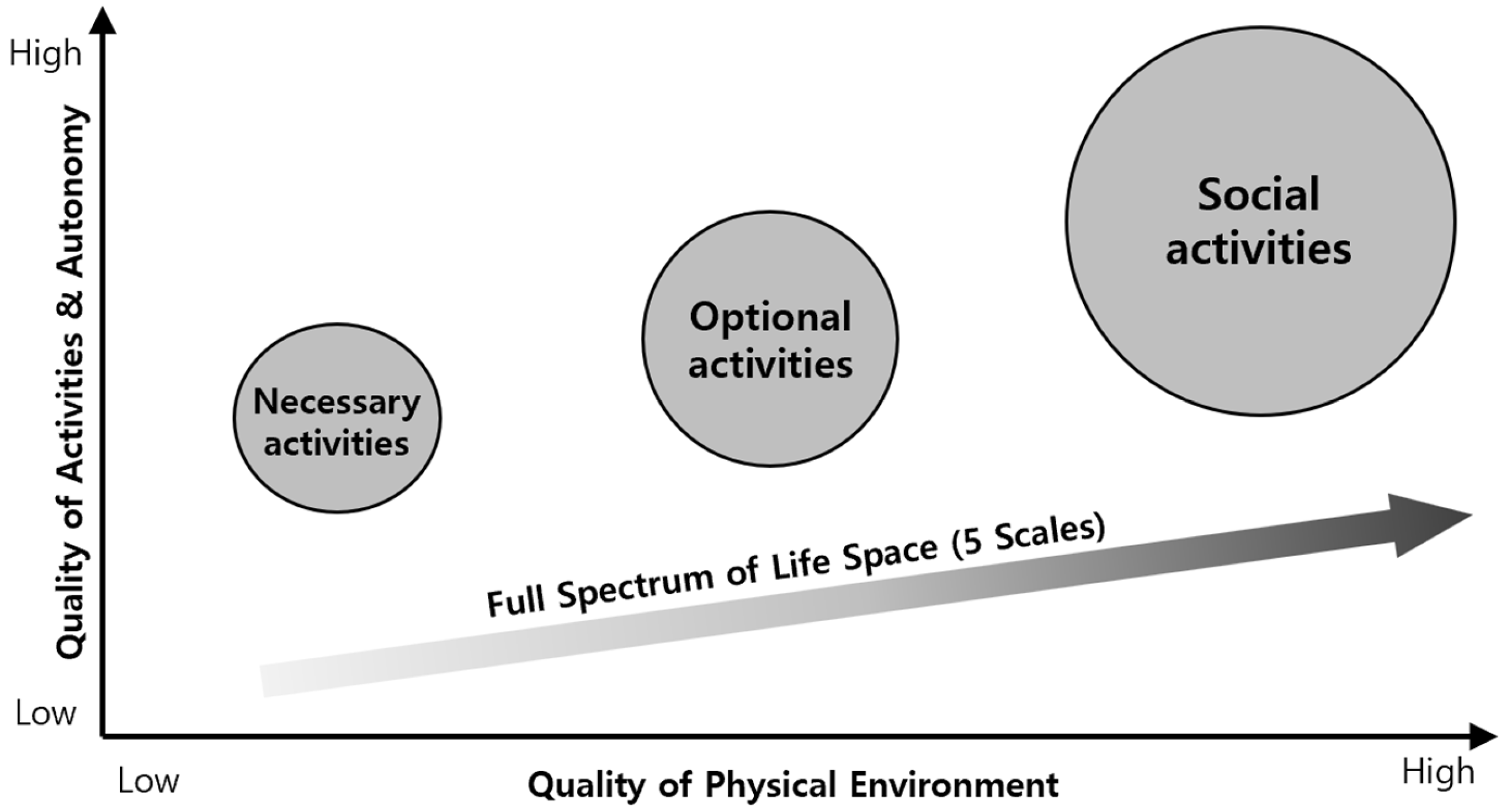

- Necessary activities are essential routines such as errands and grocery shopping, performed regardless of environmental conditions.

- Optional activities: leisure activities, which are highly dependent on the quality of physical space.

- Social activities: interpersonal interactions, which increase significantly when environments are designed to actively support participation.

- (2)

- Community Formation Based on NORC.

- (3)

- Urban Environment Formation Based on AFC

- Walkable and accessible public spaces;

- Age-friendly transportation systems;

- Inclusive public services;

- Mechanisms for civic participation.

3.2. Conceptual Composition

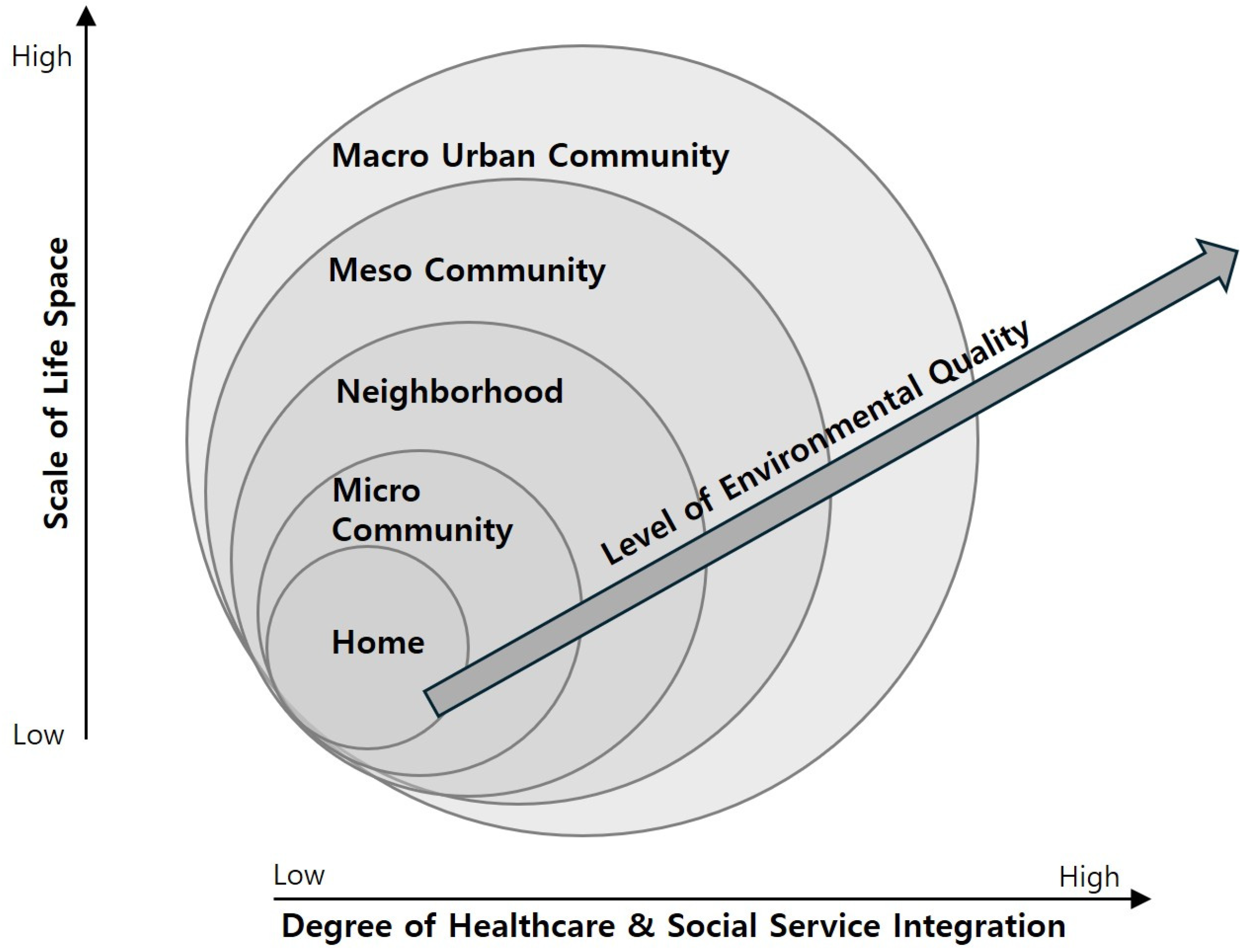

- Mobility ranges, which capture older adults’ spatial movements and activity patterns in daily life.

- Social connectivity, which reflects opportunities for participation, intergenerational exchange, and community building.

3.3. Spatial Strategies and Analytical Lens

- (1)

- Typological Spectrum of Strategies

- (2)

- Analytical Lens for Integration

- Docility Hypothesis: vulnerability and adaptation to environmental press.

- Life Space Theory: mobility and spatial range as predictors of autonomy.

- CODA and SPOT frameworks: cumulative opportunities and spatiotemporal adaptation.

- (3)

- Toward Integration

3.4. Case Illustration Method

- (1)

- Selection Criteria

- Relevance to the Spatial Spectrum: Each case aligns with one or more stages of the AIC spectrum, spanning home, community, and urban levels.

- Representative Diversity: The set includes small-scale home modifications, mid-scale community housing initiatives, and large-scale urban regeneration projects.

- Illustrative Potential: Cases were chosen for their clarity in demonstrating design principles and social implications, rather than for statistical generalization.

- (2)

- Sources of Case Material

- Documented precedents: architectural and planning projects with relevance to aging and community design.

- Visual illustrations: diagrams and conceptual renderings created to demonstrate extended environments and possible future scenarios.

- Hybrid references: instances where empirical examples were lacking, supplemented with adapted or newly generated images to simulate feasible applications.

- (3)

- Role of Visual Representation

- (4)

- Contribution of Case Illustrations

- Exemplify scalability: showing how strategies extend from the home to the community and the city.

- Provide visual evidence: clarifying the feasibility of translating theoretical constructs into extended community design.

- Highlight opportunities for innovation: especially in urban contexts where demographic change and social integration are most pressing.

4. Results

4.1. Extended Community Space: The Intervention Role of AIC

4.2. Spatial Spectrum

- Stage 1: Home-Based AdaptationThe first stage emphasizes housing modifications that enable older adults to remain in familiar domestic settings despite functional decline. Typical strategies include barrier-free design, assistive technologies, and safety improvements. This stage corresponds directly with Lawton’s Docility Hypothesis, focusing on minimizing vulnerability by reducing environmental press at the household level.

- Stage 2: Micro-Community SupportThe second stage introduces micro-urban clusters, such as co-housing complexes, senior apartments, or localized community centers. These spaces extend beyond individual housing by integrating shared facilities, social ties, and everyday services. At this stage, the Life Space Theory becomes evident, as mobility expands from the home to nearby communal areas, enabling optional and social activities to flourish.

- Stage 3: Community IntegrationThe third stage scales up to community-level integration, represented by NORC-type environments. Services such as healthcare access, transportation, welfare support, and cultural programs are provided within the neighborhood context. This stage represents the general-level community of the spectrum, bridging the gap between domestic adaptation and urban infrastructures.

- Stage 4: Extended Community and Inter-Generational NetworksThe final stage extends beyond the immediate city to embrace broader community networks. This includes regional linkages, digital infrastructures, and intergenerational participation platforms. By embedding older adults within wider social and spatial systems, this stage transcends conventional “aging in place” and reframes aging as a community-integrated, future-oriented process. It can be considered as meso-community.

- Stage 5: Urban ConnectivityThe fourth stage highlights city-level strategies derived from the Age-Friendly Cities (AFC) framework. Public transportation, walkable streets, inclusive public services, and mechanisms for civic participation ensure that older adults can remain active and engaged in urban life. At this stage, both Docility (reducing barriers) and Life Space (expanding mobility) converge to sustain autonomy within large-scale infrastructures. It can be considered as macro-community.

4.3. Case Applications

- Case 1: Home-Based Modification (Stage 1)Residential adaptations—such as barrier-free bathrooms, widened doorways, and assistive technologies—illustrate how older adults can maintain autonomy despite functional decline. As illustrated earlier in Figure 5, such modifications reduce environmental press in accordance with the Docility Hypothesis, thereby supporting independent living at the domestic scale.

- Case 2: Community Housing Model (Stages 2–3)Community housing clusters demonstrate how micro-urban environments (e.g., co-housing, senior apartments) evolve into community-integrated systems resembling NORCs. As illustrated earlier in Figure 6, shared facilities, healthcare services, and cultural programs transform residential clusters into socially structured foundations, reinforcing participation and collective well-being.

- Case 3: Urban Regeneration and Connectivity (Stage 4)Urban regeneration projects show how AFC principles can be embedded into large-scale city design, enhancing accessibility, public transit, and walkability. As illustrated earlier in Figure 6, AI-generated visuals complement precedent projects, projecting how age-friendly infrastructures can expand older adults’ life space into broader urban contexts.

- Case 4: Apartment Complex as Extended Community (Stages 2–5)In the Korean context, large-scale apartment complexes have increasingly evolved into extended communities that embody the principles of Aging in Community (AIC). These developments integrate residential, commercial, and welfare functions within a single urban fabric, enabling social participation, intergenerational interaction, and neighborhood-based care. The study identifies these complexes as intermediate-scale environments corresponding to Stages 2–5 of the AIC spectrum, bridging individual housing adaptation with community-level integration. The empirical photographs presented in Figure 9 demonstrate how universal design principles and mixed-use infrastructures are embedded in contemporary Korean apartment complexes, transforming everyday living environments into inclusive and sustainable communities. The distinctive features are depicted in Figure 10.

- Case 5: Urban-Level Integration and Policy Framework (Stage 5)This case exemplifies how AIC principles can be embedded in long-term urban policy and planning strategies, thereby ensuring both sustainability and inclusivity. Collectively, the cases presented across the micro, meso, and macro levels illustrate the progressive translation of theoretical constructs into practical implementation. By aligning these cases with the five-stage AIC spectrum, the study demonstrates the framework’s scalability and adaptability across spatial and policy domains. Through this integrative perspective, the research highlights how the concept of Aging in Community can evolve into a transferable model for designing inclusive, age-friendly environments that respond dynamically to demographic and social change.These applied stages reinforce the theoretical continuum proposed in the methodology, validating the AIC framework as a scalable and context-responsive model for age-friendly community design.

5. General Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Differentiation from Previous Studies

5.3. International and Policy Relevance

- Infrastructural integration (housing, transportation, digital networks);

- Welfare and healthcare coordination (community-based services, preventive health, and social care);

- Intergenerational engagement (participation platforms, civic inclusion, and cultural programs).

5.4. Limitations and Future Work

- Comparative international research to examine how AIC principles operate in diverse cultural and policy contexts, identifying both universal patterns and local adaptations.

- Integration with emerging technologies—including smart mobility, digital health monitoring, and AI-assisted community planning—to operationalize extended community strategies in scalable and cost-effective ways.

5.5. Concluding Remarks

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Recommendations

- First, design and planning practice should structure environments to support both autonomy and social participation.

- At the home level, universal design and barrier-free retrofits remain crucial.

- At the micro-community level, clustered housing models and shared facilities can transform residential spaces into active community hubs.

- At the neighborhood and city levels, transit-oriented development, walkable infrastructures, and inclusive public spaces should be prioritized to expand older adults’ life spaces and reduce risks of isolation.

- Second, policy development must move beyond single-program interventions to adopt integrated strategies.

- Bundled funding streams that align housing, transportation, welfare, and healthcare can institutionalize AIC principles.

- Interdepartmental governance structures should be created to synchronize planning across agencies.

- Embedding AIC targets into building codes, urban development standards, and welfare programs would ensure sustainability and equity—particularly for vulnerable populations.

- Third, future research and innovation should focus on empirical validation across diverse cultural and policy contexts.

- Comparative international studies can identify both universal patterns and context-specific adaptations of extended community formation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Stage | Spatial Focus | Representative Strategies | Theoretical Linkages | Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1—Home-Based Modification and Improved Unit Plan(A) | Individual household | Barrier-free design, assistive technologies, safety enhancements | Docility Hypothesis, Aging in Place (AIP) | Environmental press reduction, autonomy, functional support |

| Stage 2—Home-Based Improvement and Micro-Community Formation (AB) | Co-housing, small-scale collective housing clusters | Shared facilities, neighbor-based services, social ties | Life Space expansion (home → nearby), AIC | Optional and social activity support, proximity-based participation |

| Stage 3—Community Vitalization and Improvement (B) | Neighborhood/NORC-type environment | Healthcare access, local welfare, cultural and mobility services | NORC framework, meso-level AIC | Community integration, service clustering, participation |

| Stage 4—Macro-Community Based on Urban Connectivity and Age-Friendly Infrastructure (BC) | City-level and inter-neighborhood infrastructure | Public transportation, walkable streets, inclusive public spaces | AFC concept, convergence of Docility and Life Space | Autonomy, mobility expansion, inclusive urbanism |

| Stage 5—Extended Community and Intergenerational Networks (C) | Regional and cross-scale linkages | Digital infrastructure, intergenerational participation platforms, policy integration | AIC, Active Aging, CODA/SPOT integration | Intergenerational solidarity, structural embedding, sustainable aging |

References

- Greenfield, E.A.; Black, K.; Buffel, T.; Yeh, J. Community gerontology: A framework for research, policy, and practice on communities and aging. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, D.; Nayak, U.S.L.; Isaacs, B. The life-space diary: A measure of mobility in old people at home. Int. Rehabil. Med. 1985, 7, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peel, C.; Baker, P.S.; Roth, D.L.; Brown, C.J.; Bodner, E.V.; Allman, R.M. Assessing mobility in older adults: The UAB Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment. Phys. Ther. 2005, 85, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, M.; Baker, P.S.; Allman, R.M. A life-space approach to functional assessment of mobility in older adults. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 2002, 35, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, H.W.; Gerstorf, D. Person–environment resources for aging well: Environmental docility and life space as conceptual pillars for future contextual gerontology. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahl, H.W.; Weisman, G.D. Environmental gerontology at the beginning of the new millennium: Reflections on its historical, empirical, and theoretical development. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, M.P. Social ecology and the health of older people. Am. J. Public Health 1974, 64, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahl, H.W.; Lang, F.R. Aging in context across the adult life course: Integrating physical and social environmental research perspectives. Annu. Rev. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2003, 23, 1–33. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285009160 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Lecovich, E. Aging in place: From theory to practice. Anthropol. Noteb. 2014, 20, 21–33. Available online: https://anthropological-notebooks.zrc-sazu.si/Notebooks/issue/view/23 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Wahl, H.W.; Iwarsson, S.; Oswald, F. Aging well and the environment: Toward an integrative model and research agenda for the future. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimmer, M.; Riener, R.; Walsh, C.J.; Seyfarth, A. Mobility related physical and functional losses due to aging and disease—A motivation for lower limb exoskeletons. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2019, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelézeau, V. Ap’at’ŭ Konghwaguk: On the Republic of Apartments. East Asia Int. Q. 2009, 26, 121–145. [Google Scholar]

- National Geographic Information Institute. The National Atlas of Korea I. 2022. Available online: http://nationalatlas.ngii.go.kr/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Statistics Korea. Population Projections for Korea (2022–2072); Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements. Urbanization and Urban Policies in Korea; KRIHS Technical Report No. 11-02; Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements: Sejong-Si, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 1–208. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, M.P. The Impact of the environment on aging and behavior. In Handbook of the Psychology of Aging; Birren, J.E., Schaie, K.W., Eds.; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 276–301. [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos, J.; Steinman, B.A.; Nguyen, A.Q.D.; Bressette, M. Assessing and Adapting the Home Environment to Reduce Falls and Meet the Changing Capacity of Older Adults. J. Hous. Elder. 2012, 26, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vladeck, F. A Good Place to Grow Old: New York’s Model for NORC Supportive Service Programs; United Hospital Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; pp. 1–76. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547307 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Lim, Y.J.; Lee, Y.S.; Cho, S.Y. Analysis of user benefits in socially integrative community housing based on resident needs. J. Korean Inst. Inter. Des. 2019, 28, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C.; Scharf, T. Ageing in Urban Environments: Place, Mobility and Social Participation; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The Global Network for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: Looking Back Over the Last Decade, Looking Forward to The Next; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Green Paper on Ageing: Fostering Solidarity and Responsibility Between Generations; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, M.E.; Ross, L.E. Naturally occurring retirement communities: A multiattribute examination of desirability factors. Gerontologist 1990, 30, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oswald, F.; Wahl, H.W. Dimensions of the meaning of home. In Home and Identity in Late Life: International Perspectives; Rowles, G.D., Chaudhury, H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Scharf, T.; Phillipson, C. Ageing and Urban Change: New Perspectives on the Place of Ageing; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Theoretical Framework | Spatial Scale | Representative Applications | Expansion/ Convergence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docility (Passive/Physical Adaptation) | AIP (Home-based) | Barrier-free home modification and physical adaptation for older adults | Expanded from individual home modifications to community housing within AIC, linking aging-in-place with sustainable living |

| AIC (Social–Relational Environment) | NORC (Community-based) | Socially embedded, age-integrated community building | Scaled bidirectionally, from traditional villages to small-scale shared housing and large-scale apartment complexes |

| Active Aging (Autonomous, Engaged Use of Environment) | Life Space (City-based) | Ensuring access to mobility, urban walkability, transportation, and activity spaces | Expanded to infrastructure-centered large housing complexes and urban environments, ensuring accessibility, comfort, and participation |

| Conceptual Axis | Initial Spatial Scale | Current Application | Expansion Flow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docility | Detached Housing (Home) | Home | Expanded to diverse housing types, including varied unit sizes and small-scale multi-unit dwellings → enabling more flexible AIP environments |

| AIC | Village/Neighborhood (Community) | Neighborhood | Expanded bidirectionally, from small-scale community housing → to large-scale apartment complexes |

| Active Aging | Urban Scale | Urban Environment | Expanded daily life territories from large complexes and surrounding urban areas → into extended life spaces grounded in Active Aging |

| Type of Spatial Spectrum | Spatial Characteristics & Representative Examples | Theoretical Connections | Explanation & Keywords | Practical Stage (AIC Code) & Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home | Physical living space of an individual household. Elderly single-household renovation; barrier-free design; age-friendly unit layout. | ① Docility ② AIP (home) | Physical adaptation, independence, and safety improvements. | Stage 1—Home-Based Adaptation (Plan A) Life-Space Theory: Minimum range; home-based implementation. (Figure 5) |

| Small Community Housing | Small-scale shared housing with neighborly relations. Co-housing; community-based small units with shared lounges or gardens. | ① Expansion of Docility ② Expansion of AIP ③ Expansion of AIC (social relations) ④ Expansion of NORC | Home improvement and micro- community formation. | Stage 2—Home-Based Improvement and Micro-Community Formation (AB) Life-Space Theory: Home-extension stage. Expanded Community Type 1. (Figure 9) |

| Regenerated Neighborhood Villages | Community revitalization through shared spaces, local services, and intergenerational engagement. Neighborhood-scale environments supporting daily interaction. | ① AIC (social participation) ② NORC (neighborhood) | Community restoration and participatory engagement. | Stage 3—Community Vitalization and Improvement (B) Restoration of community networks through local participation. (Figure 6) |

| Meso- Community/ Integrated Urban Cluster | Neighborhood clusters linked by public facilities and mobility infrastructure. Walkable areas, civic centers, and inclusive public spaces. | ① AFC (Active Aging) ② Life Space (urban level) | Mobility expansion and inclusive urban participation. | Stage 4—Meso-Community Integration (BC) Life-Space Theory: City-extension stage. Expanded Community Type 2. (Figure 10) |

| Macro- Community/Regional Urban Network | Regional and inter-city connections integrating digital, transportation, and welfare infrastructure. Cross-scale connectivity promoting intergenerational solidarity. | ① AIC ② Active Aging ③ CODA/ SPOT Integration | Structural embedding, sustainable aging, and intergenerational networks. | Stage 5—Macro-Community Based on Urban Connectivity and Regional Integration (C) Life-Space Theory: Maximum range; macro-level implementation. (Figure 7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, Y.S.; Lee, D.Y.; Jun, E.J. A Spatial Spectrum Framework for Age-Friendly Environments: Integrating Docility and Life Space Concepts. Buildings 2025, 15, 4164. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224164

Lee YS, Lee DY, Jun EJ. A Spatial Spectrum Framework for Age-Friendly Environments: Integrating Docility and Life Space Concepts. Buildings. 2025; 15(22):4164. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224164

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Yeun Sook, Da Young Lee, and Eun Jung Jun. 2025. "A Spatial Spectrum Framework for Age-Friendly Environments: Integrating Docility and Life Space Concepts" Buildings 15, no. 22: 4164. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224164

APA StyleLee, Y. S., Lee, D. Y., & Jun, E. J. (2025). A Spatial Spectrum Framework for Age-Friendly Environments: Integrating Docility and Life Space Concepts. Buildings, 15(22), 4164. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224164