1. Introduction

With the continuous development of lightweight construction materials and the increasing emphasis on the esthetic design of buildings, the design of pedestrian overpasses has also changed accordingly. Nowadays, pedestrian overpasses have larger spans and stronger load-bearing capacities, but their own natural frequencies are lower. It is worth noting that these reduced fundamental frequencies are often very close to the frequency of people walking. This resonance situation often leads to excessive vibrations in the bridge’s structure when pedestrians pass through. This not only greatly affects the walking comfort of pedestrians, but in severe cases, it may even hinder the normal passage of pedestrians. In addition, for lightweight bridges, the load exerted by pedestrians cannot be simply regarded as a static or vibrating moving force. The bridge responses caused by pedestrians walking, running, jumping, and swaying at different speeds are different [

1,

2].

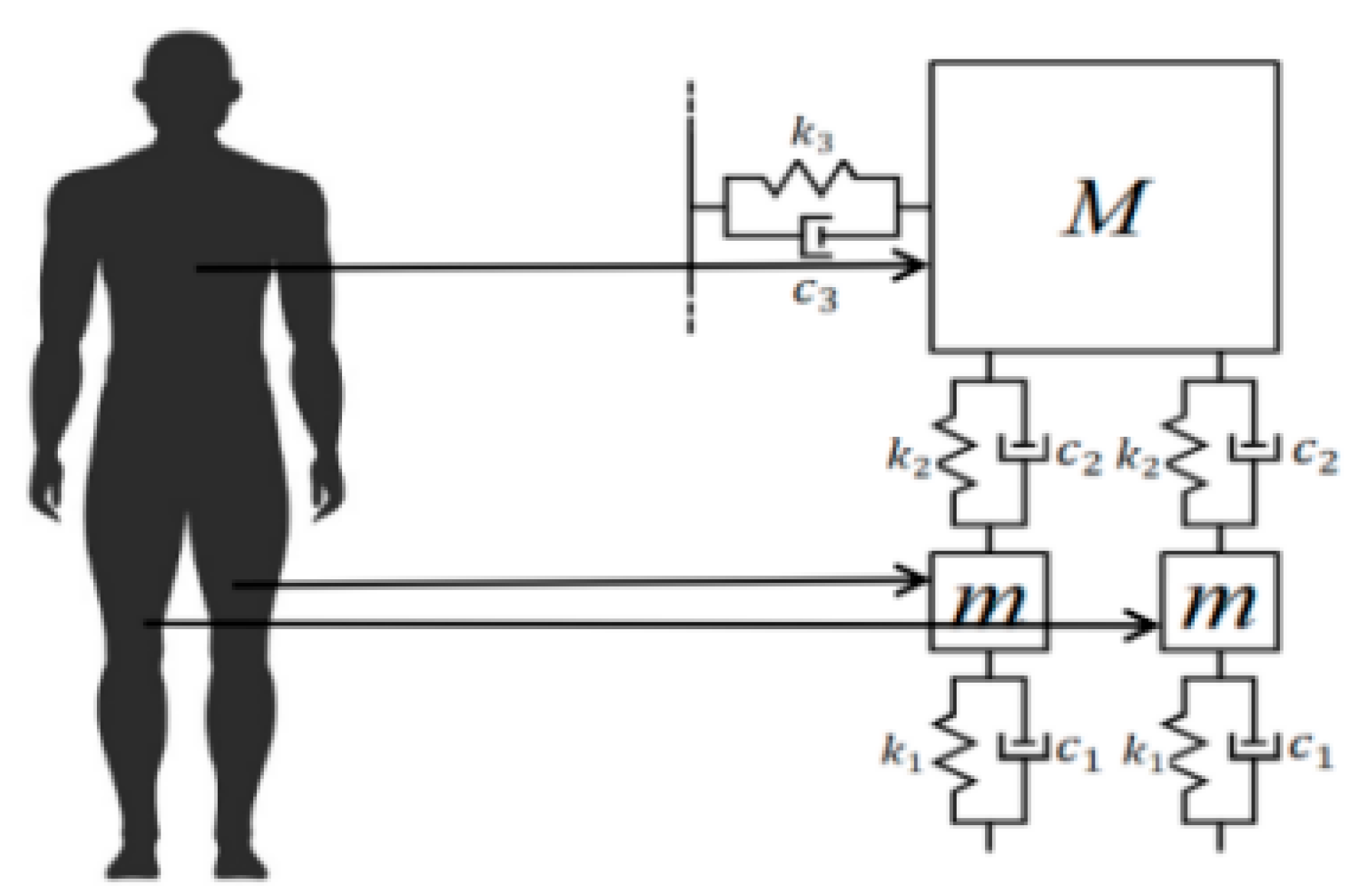

In fact, pedestrians themselves are like a coupled system composed of mass, spring, and damping. The dynamic interaction between pedestrians and the bridge structure, including the specific position where the load is applied, will fundamentally change the vibration characteristics of the bridge.

Wheeler [

3] established the relationship between step frequency and dynamic loading characteristics, while Pancaldi et al. [

4] developed statistical methods to quantify walking force variability. Advances in biodynamic models of pedestrians included Kuo’s [

5] inverted pendulum model for lateral balance, Geyer’s [

6] bipedal walking model for 3D loading effects, and Zhu’s [

7] improved version incorporating foot–ground interactions.

Pedestrian bridge traffic dynamics are complex. In the current urbanization process, the importance of crowd evacuation in urban planning and security management has become increasingly prominent. In the event of emergencies such as fires, earthquakes, and terrorist attacks, effective evacuation can quickly move people from dangerous areas to safe areas, thus minimizing casualties and property losses. As intelligent entities, pedestrians respond to both the movement of the structure and the presence of other pedestrians. Consequently, pedestrian traffic flow models are categorized into macroscopic and microscopic models.

Some studies about pedestrian behavior can be found as follows. Macroscopic models analyzed density–flow relationships but lack granularity [

8,

9]. Muraleetharan et al. [

10] identified limitations in simulating pedestrian movement due to insufficient level-of-service data, a gap addressed by Shen et al. [

11] through cluster analysis and meta-regression. While macro models offer a holistic view of pedestrian behavior and interactions, their precision is limited. Microscopic models now supplement macro models, improving pedestrian behavior analysis. Microscopic models, like the social force model [

12,

13] and its extensions [

14,

15], enable finer-scale simulations of crowd behavior and vibration mitigation strategies.

The theory of cellular automata (CA), first proposed by Neumann and Burks in 1954, has become a powerful tool for simulating crowd dynamics, particularly in evacuation scenarios. CA models excel at capturing emergent behaviors in pedestrian flows through simple local interaction rules operating on discrete grid systems. Blue et al. [

16] were the first to use the CA model to study the movement mode of pedestrian flow. By dividing space into grids of the same scale and then evolving and updating according to the evolution rules of characteristics, Wolf [

17] further advanced CA as a versatile computational tool across multiple disciplines. Subsequent studies addressed CA’s limitations: Yamamoto et al. [

18] introduced real-coded CA (RCA), enabling multidirectional and continuous pedestrian movement beyond discrete grids, while Bandini et al. [

19] incorporated stochasticity to better replicate realistic crowd distributions. Recent work emphasizes dynamic adaptability—Padovani et al. [

20] developed an adaptive CA model that adjusts rules in real-time for complex environments and Mao et al. [

21] extended this by integrating psychological and physiological heterogeneity to refine multi-behavior interactions during emergency evacuations.

Pedestrian behavior depends on preferences, which affect movement and decisions. Recent studies demonstrate their importance in urban design and walkability assessments. Kim et al. [

22] employed multilevel modeling to analyze the impact of built environment factors on pedestrian satisfaction. Their findings revealed that both meso-scale factors and micro-scale factors significantly influence pedestrian satisfaction. Furthermore, they found that pedestrians’ perceptions of the environment vary depending on their trip purposes. Liang et al. [

23] enhanced pedestrian accessibility analysis by integrating street-level infrastructure with individual preferences. Facchini et al. [

24] advanced preference measurement through comparative VR studies, establishing immersive technology’s superiority in capturing authentic behaviors. Naseri et al. [

25] identified key psychological factors and demographic variables as primary determinants of pedestrian behavior in urban environments. These findings collectively highlight behavioral preferences as essential for optimizing pedestrian spaces and urban mobility systems.

While these models offer insights into pedestrian behavior to some extent, they do not fully capture the intricate dynamics of pedestrian–structure interactions. To achieve more accurate simulations, a comprehensive understanding of pedestrian behavioral nuances is imperative. Similarly, there are challenges in studying crowd load trajectories. Existing models, whether macroscopic or microscopic, have their limitations in reflecting the intricacies of pedestrian movements and their social attributes. Advancements in loading methods for random crowd loads can further enhance the accuracy of pedestrian bridge vibration analyses.

In this paper,

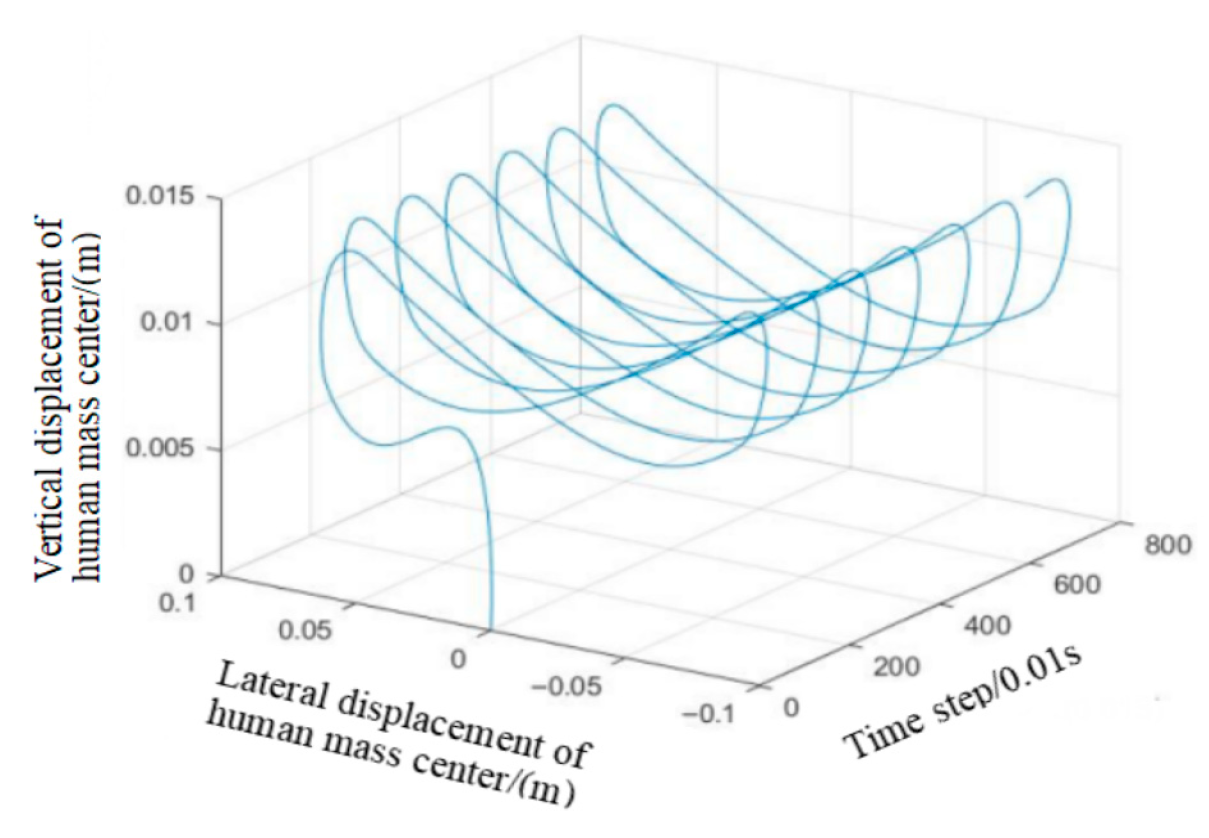

Section 2 establishes a bidirectional multi-degree-of-freedom bipedal walking model.

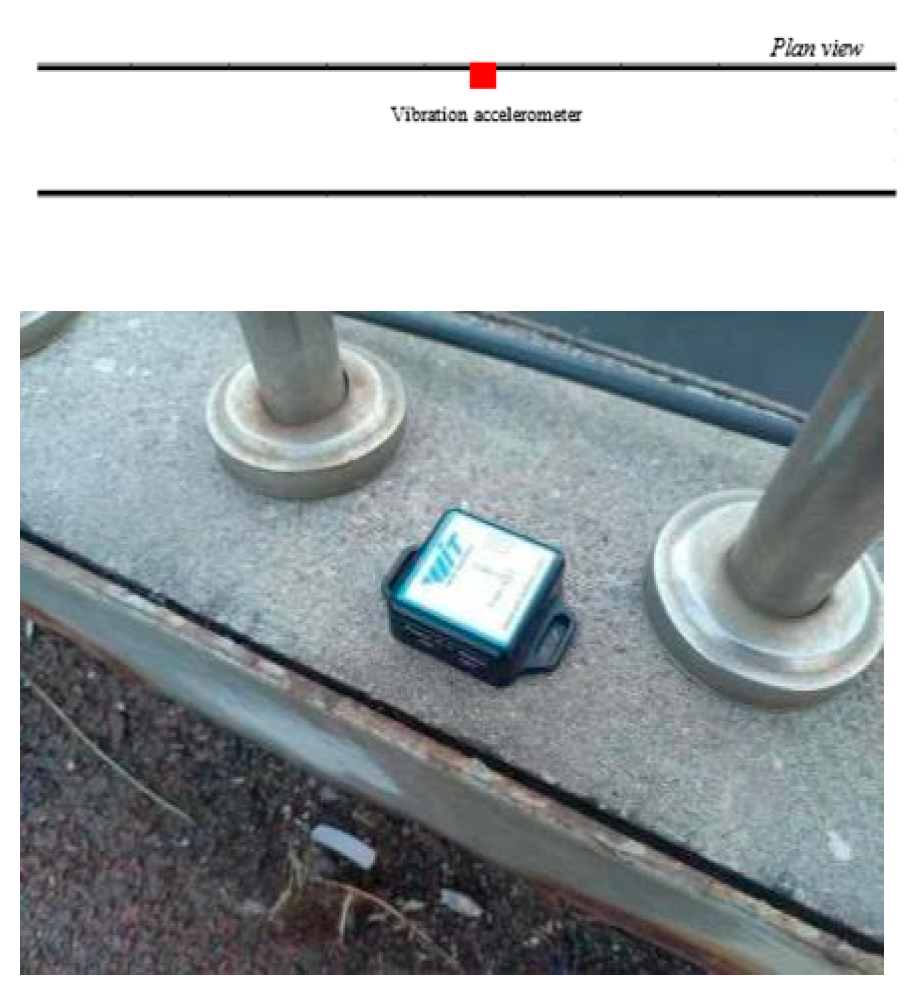

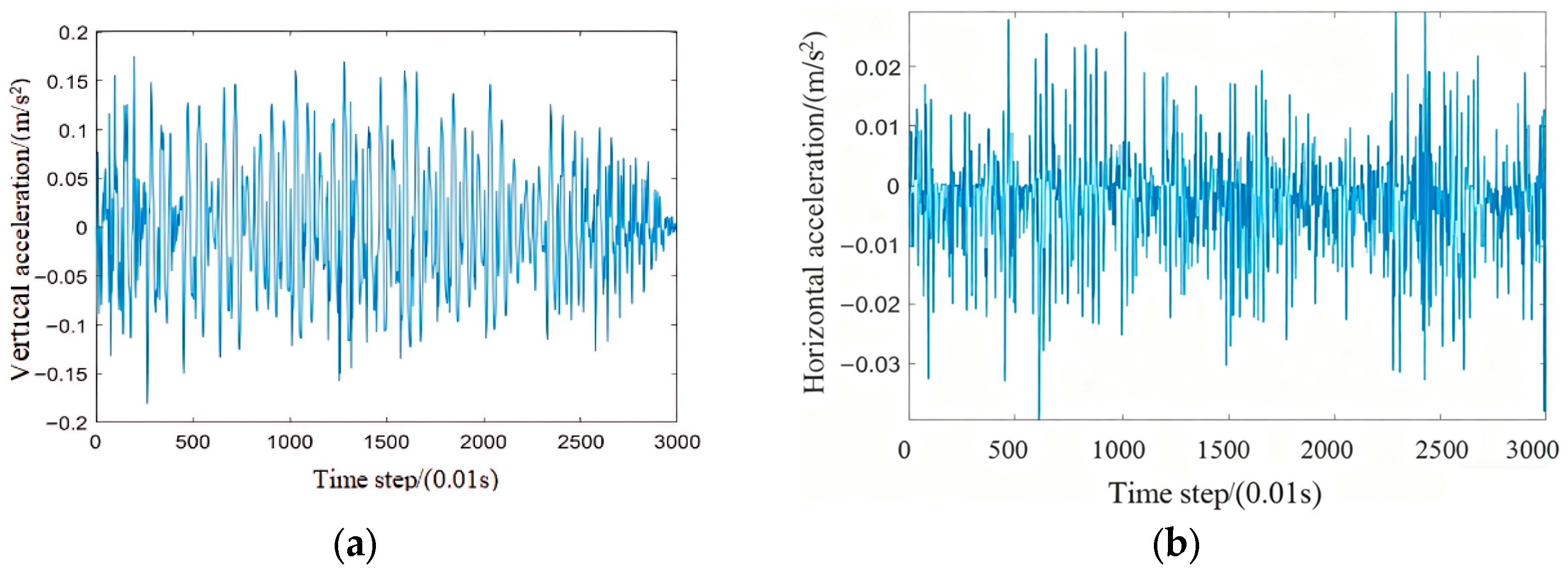

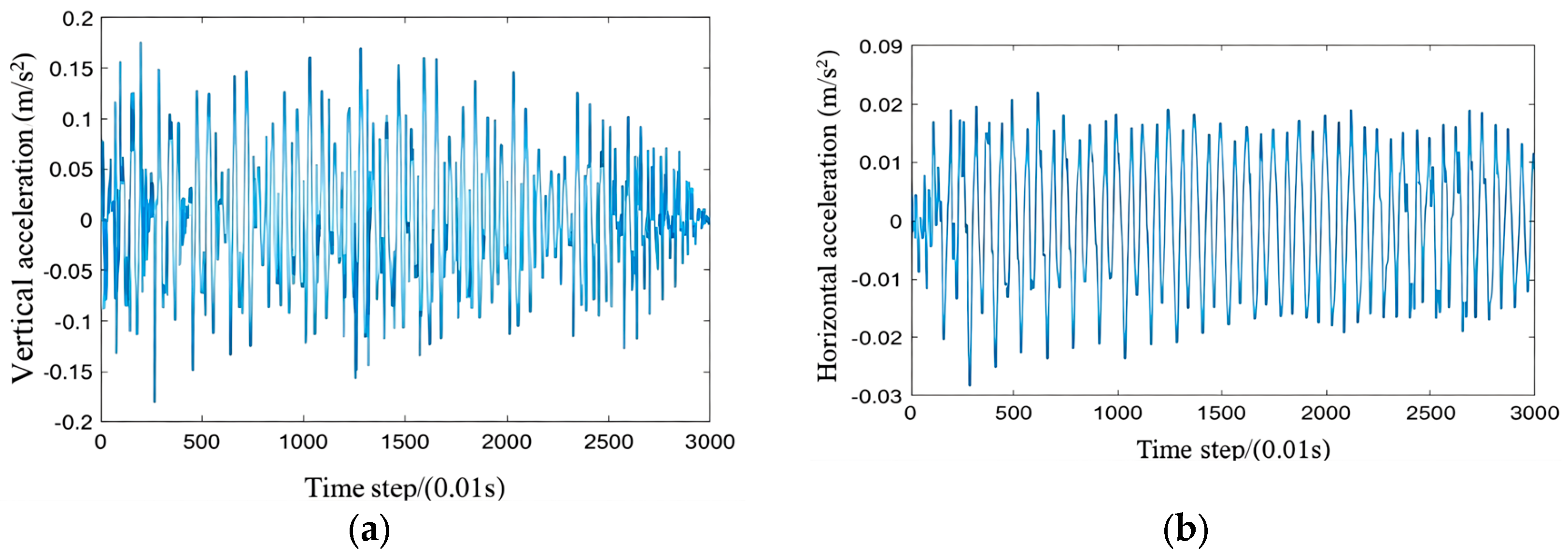

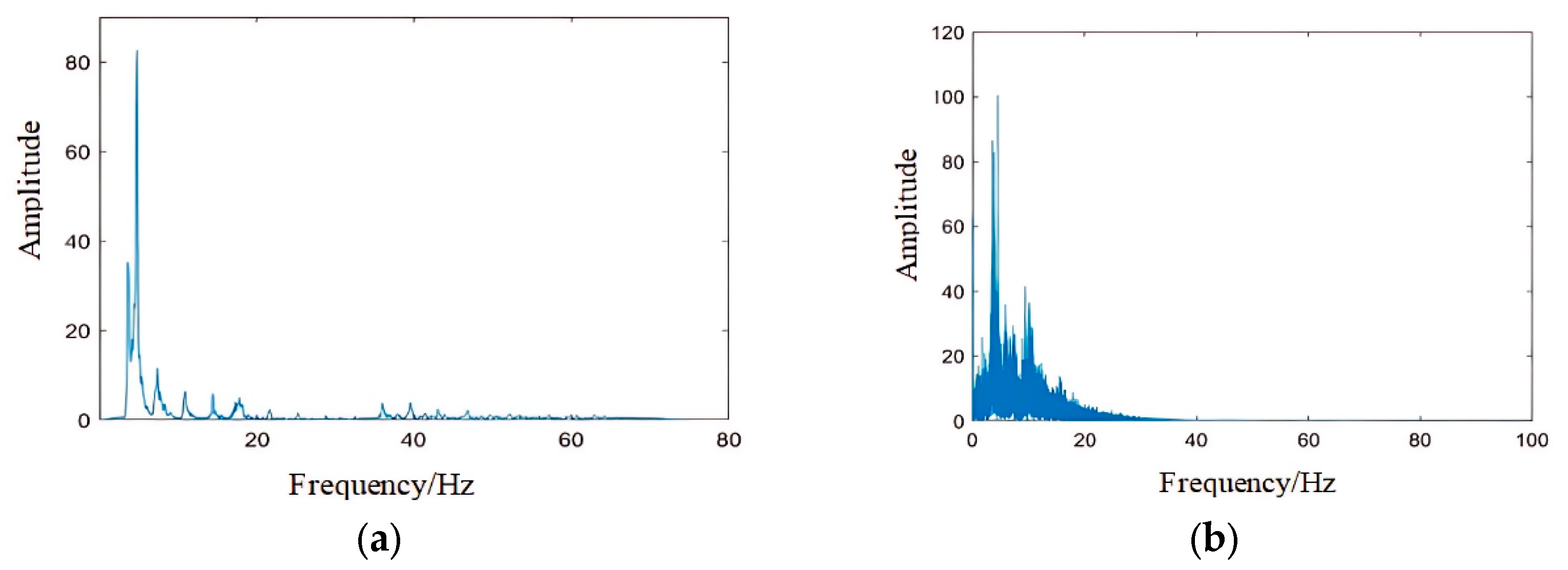

Section 3 introduces the field test of the pedestrian bridge to verify the proposed human–structure interaction model.

Section 4 establishes a cellular automaton crowd model including static field, dynamic field, and repulsive field to simulate the movement of pedestrians in different scenarios.

Section 5 combines the crowd model with the finite element bridge model to analyze the vibration response under different pedestrian parameters and densities.

Section 6 lists the limitations of this article. Finally,

Section 7 summarizes the main conclusions of the vibrations caused by pedestrians driven by behavioral preferences, highlighting the contribution of this comprehensive approach.

4. Crowd Load Simulation Under the Cellular Automata Model

4.1. Pedestrian Flow Model

The pedestrian flow model includes three different types of path field models: static field, dynamic field, and repulsion field. The static field describes the behavior where pedestrians choose the shortest path to move to the exit in a cellular automaton model. For a deterministic cellular automaton model, the static field remains fixed and does not change over time or due to the presence or movement of pedestrians. Assuming that

Γ is the set of units available for human walking space, the static field can be calculated according to the following Formula (25):

where

is the shortest distance from the cell at (

,

) to the

k-th exit;

and

are the horizontal and vertical coordinates of the k exit, respectively.

The dynamic field can be considered a mechanism that simulates human behavior. When a pedestrian moves, they leave behind their path or trajectory in space. These trajectories change over time. The dynamic field represents these virtual pedestrian trajectories and can be modeled to simulate the mutual attraction between particles. Dynamic field D in the process of pedestrian movement will appear in the following three stages:

- (1)

When t = 0, all pedestrians do not move, and the dynamic field value D of all points (, ) is zero, that is,

- (2)

Unit cell (, ), once people walk on the dynamic field 1,

- (3)

With the change in time, the dynamic field will be diffused or decayed, which can be calculated by the following formula:

where

represents the dynamic field of the neighbor of the cell (

,

) in the previous time step. The diffusion probability of cellular dynamic field strength is expressed by

γ. The attenuation probability of cellular dynamic field intensity is expressed by

δ. According to experience, we take

γ =

δ = 0.2.

The repulsion field considers the mutual repulsion between pedestrians. In high-density traffic conditions, individuals tend to maintain a certain distance from each other to avoid contact, minimizing their interactions. This approach addresses the limitations of previous studies on cellular automaton models, which typically only considered the effects of static and dynamic fields on pedestrian movement paths.

The distance for the mutual repulsion interaction between pedestrians is set within 1.5 m. Assuming that within a 1.5 m radius around the

k-th pedestrian, there are a total of

N pedestrians, the final value of the repulsion field

E for the

k-th pedestrian can be obtained from Equation (27):

where

refers to the repulsion field value of the

k-th pedestrian at the grid point (

i,

j).

indicates the

x-coordinate of the

k-th pedestrian, and

indicates the

y-coordinate of the

k-th pedestrian.

refers to the x-coordinate of the

l-th pedestrian and

refers to the

y-coordinate of the

l-th pedestrian.

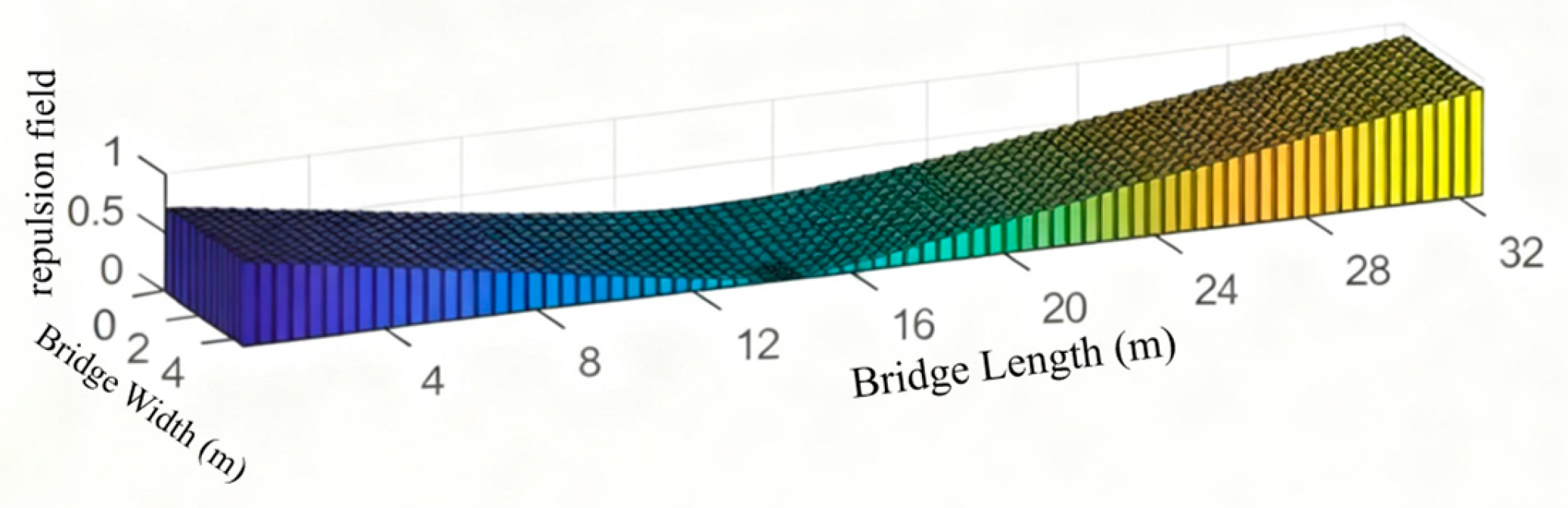

Figure 12 shows the repulsion field of the pedestrian at the moment when

x = 3.6 and

y = 14.

4.2. Model Evolution Rules

In the cellular automaton model, each cell evolves based on predetermined operational rules. The pedestrian movement rules for the pedestrian overpass cellular automaton model established in this paper are as follows:

① The adjustment and modification basis for the dynamic floor field value D is based on diffusion and decay rules. The diffusion and decay parameters for the dynamic field are α and β.

② Each pedestrian has an individual repulsion field determined based on their relative position with respect to surrounding pedestrians.

③ The transition probability

, as in Equation (28) for each pedestrian to move to an unoccupied neighboring cell (

i,

j), is calculated using the static field

∈ [0, +∞], dynamic field

∈ [0, +∞], and repulsion field

∈ [0, +∞]. This probability determines the direction of the pedestrian’s next movement. It is normalized using these three sensitivity parameters, as shown in Equation (29).

where

N is the normalization factor and

and

are parameters describing the cell state, and they can be calculated according to Equations (30) and (31):

④ Each cell representing a pedestrian selects a target cell for transition based on the calculated transition probability from the previous step.

⑤ When multiple pedestrians attempt to move to the same target cell, conflicts arise. This paper resolves such conflicts using a probabilistic method. Pedestrians with a higher transition probability, , are allowed to move and those permitted to move will continue with their steps.

⑥ The dynamic field value D increases with cell movement and the repulsion field value E continuously changes.

4.3. Simulation and Modeling

4.3.1. Bridge Model

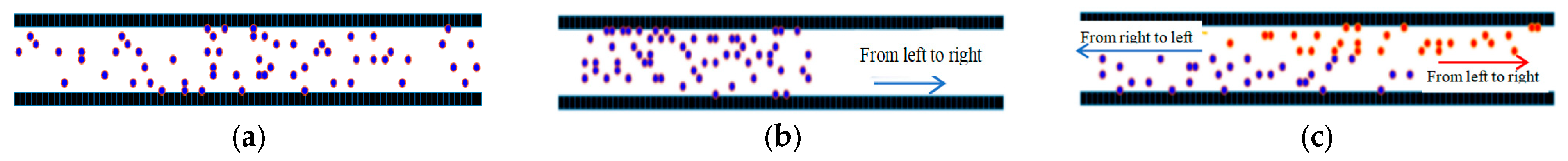

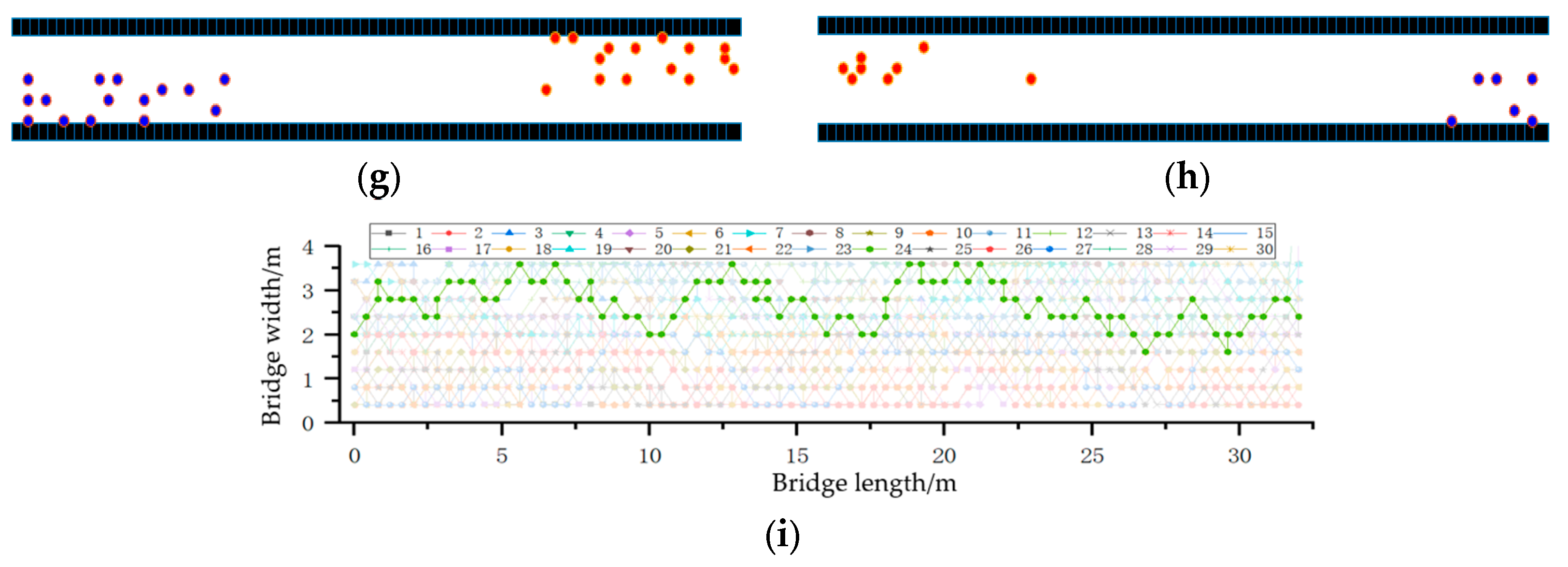

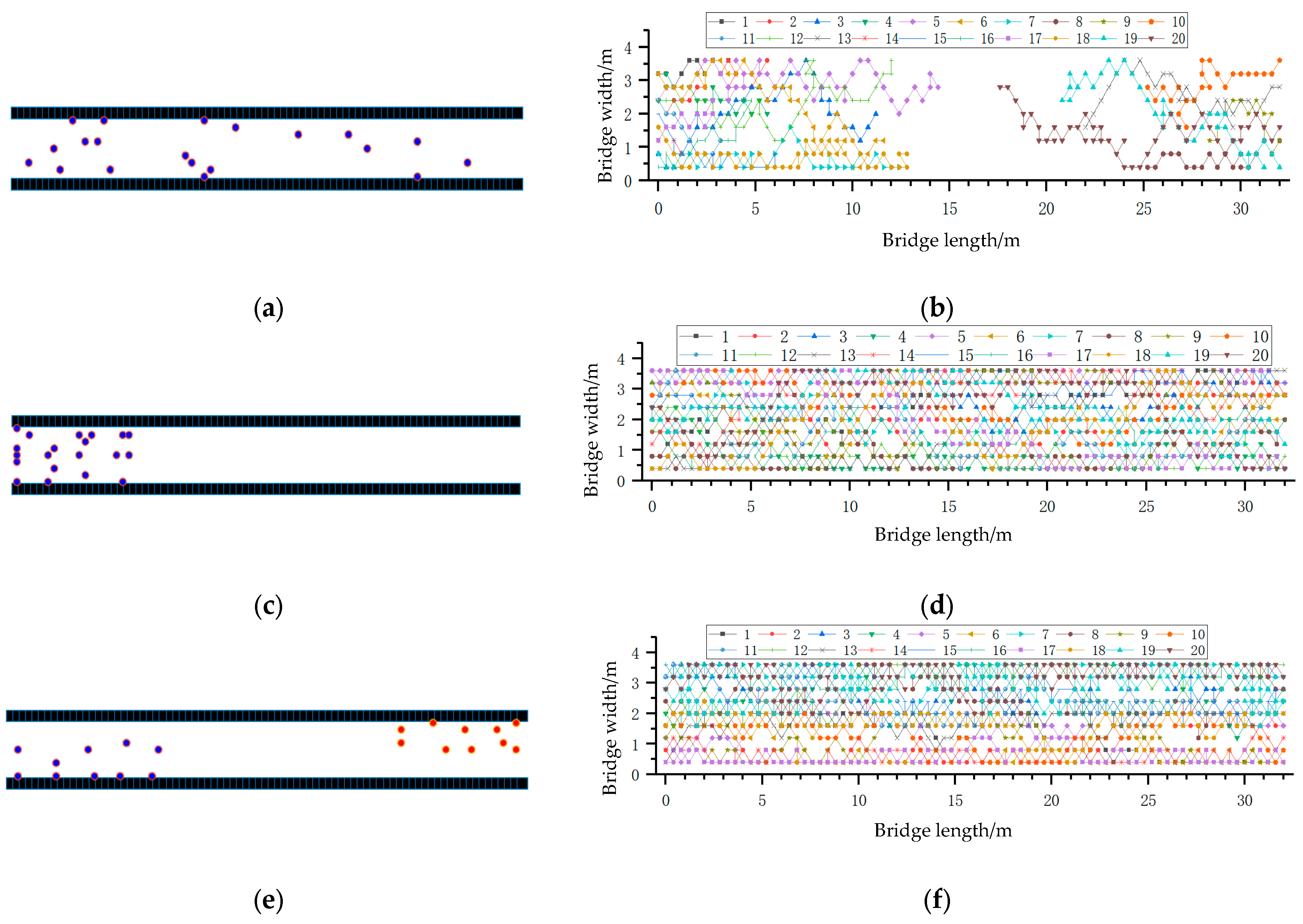

The dimensions of the bridge are 4 × 32 m, divided into a grid of 10 × 65 cellular automaton units. Each pedestrian is represented by a single cell in the cellular automaton. The walking speed of the pedestrians is 1.440 m/s and the time step is 0.2778 s. The parameters for the static field are set to 3.0, the dynamic field parameter is 0.3, and the repulsion field parameter is 0.2. The diffusion and decay parameters for the dynamic field, α and β, are both set to 0.2. The simulation distinguishes between three types of pedestrian movement states: unidirectional, bidirectional, and emergency evacuation, as illustrated in

Figure 13.

4.3.2. Parameter Dynamic Characteristics Analysis

The operational conditions are described as follows:

Static field parameter is 3.0 and dynamic field parameter is 0.3.

When the distance between pedestrians is less than 1.5 m, the repulsion field parameter is set to 1.0. If the distance between pedestrians exceeds 1.5 m, is 0.

The diffusion and decay parameters for the dynamic field are α = β = 0.2.

The number of pedestrians varies as N = 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60.

The scenarios tested include unidirectional flow, bidirectional flow, and emergency evacuation.

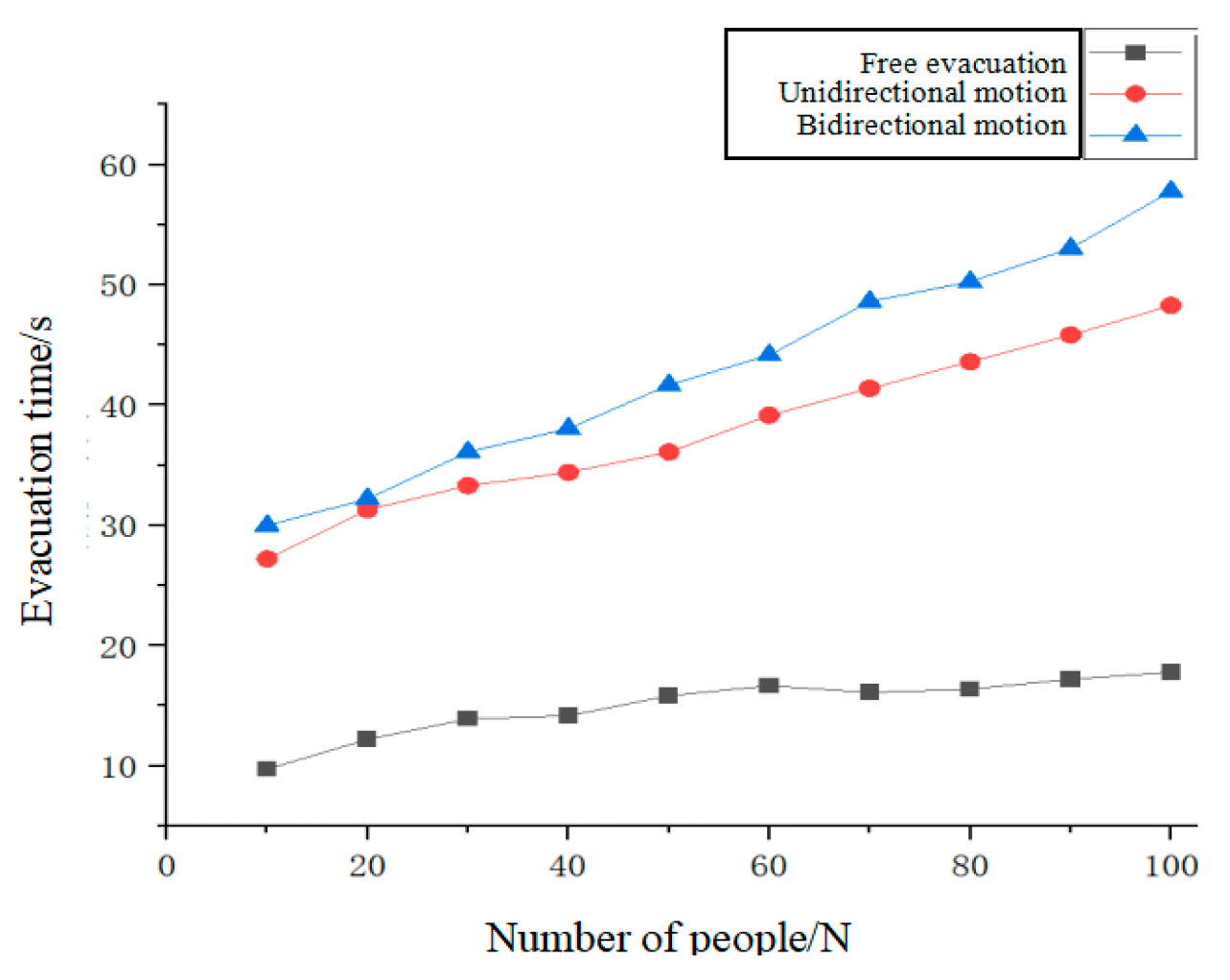

Figure 14 illustrates the pedestrian flow model for

N = 30.

Similarly, the shortest evacuation times for pedestrian numbers

N = 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, and 80 are shown in

Table 4 and

Figure 15.

From

Table 4 and

Figure 15, it can be observed that there is a close relationship between the initial number of pedestrians and the evacuation time. Especially in unidirectional or bidirectional movement scenarios, as the number of people on the bridge increases, the evacuation time also significantly increases. For instance, as the number of pedestrians increases from 10 to 40, the evacuation time under these conditions rises from 9.72 to 14.16 s, indicating a substantial change in pedestrian movement time. However, as the initial number of people continues to increase, the rate at which the movement time grows noticeably slows down.

From

Table 4 and

Figure 15, it is evident that in both unidirectional and bidirectional movement scenarios, the movement time of pedestrians depends on the time they enter the cellular automaton map. When there are fewer pedestrians, the bidirectional walking time is shorter than the unidirectional walking time. As the number of pedestrians increases, the bidirectional walking time significantly increases. This is due to the bridge becoming more congested and pedestrians walking in opposite directions might collide with each other, leading to longer bidirectional walking times. The duration of pedestrian activities is proportional to the number of participants and the starting and ending points of pedestrians also significantly influence the overall duration and efficiency of their movement.

- 2.

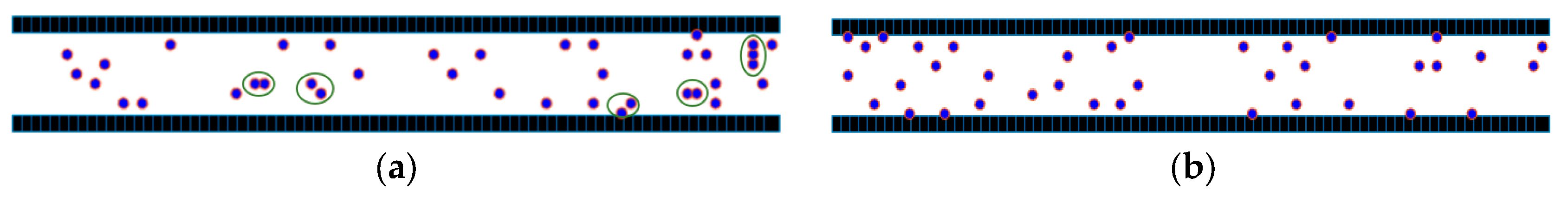

Impact of Social Force Optimization on Pedestrian Flow Models

According to research by Helbing [

13], pedestrians always attempt to maintain a certain distance from one another. In this study, a dynamically changing floor field unique to each pedestrian was introduced. When the distance between pedestrians becomes too large, the interactions weaken due to obstructed lines of sight and the excessive distance. For distances where pedestrians are less than 1.5 m apart, a repulsive force arises between them, forming a repulsion floor field, as illustrated in

Figure 16. After optimizing the repulsion field, the positions of pedestrians during their movement align more closely with real-world pedestrian movement scenarios. In

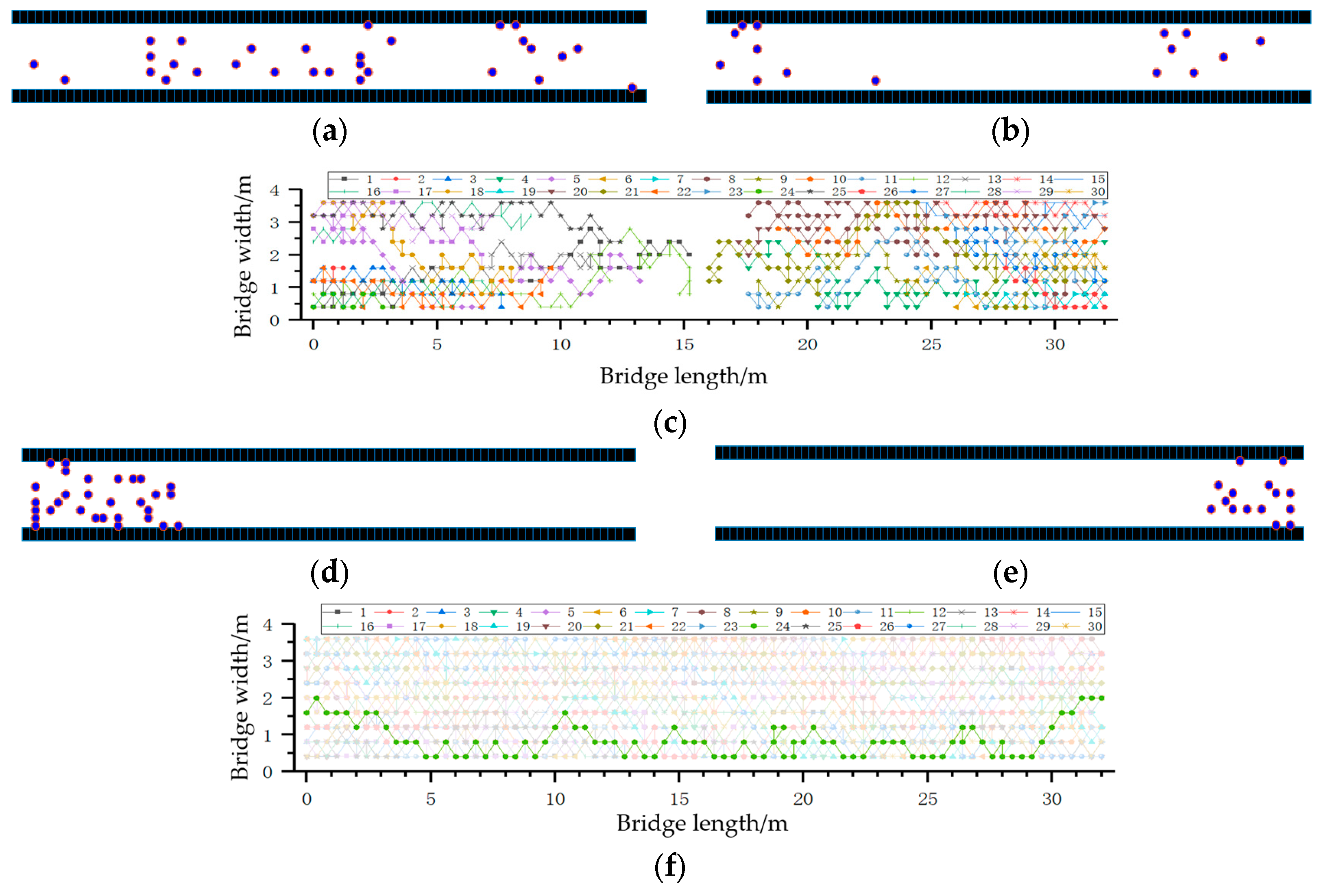

Figure 16a, there are five groups of pedestrians that are closely adjacent (circled in green in the figure). After the repulsive force is added, it is shown in

Figure 16b.

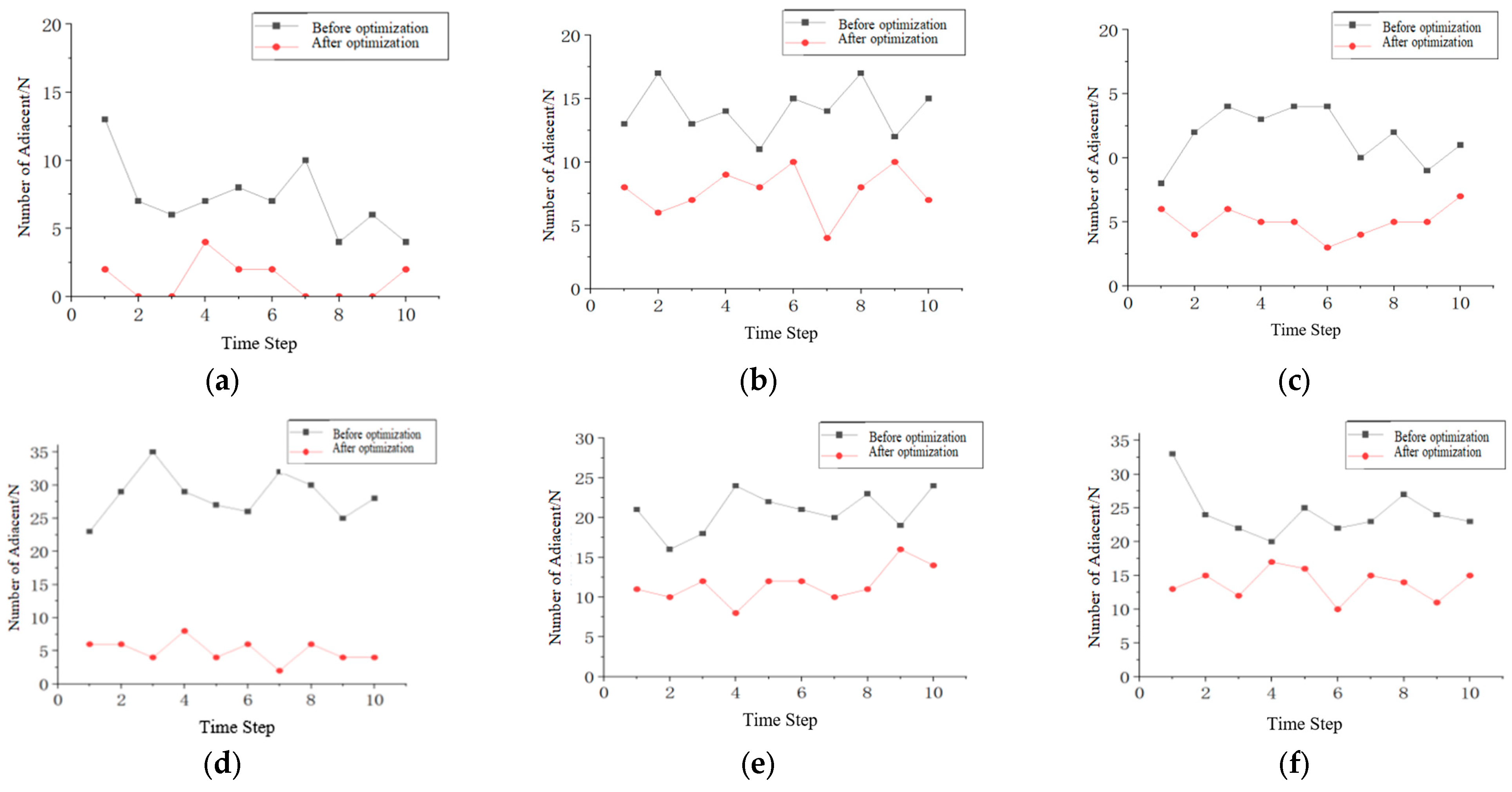

For pedestrian numbers

N = 30 and

N = 60, under three operational conditions, evacuation state, unidirectional movement state, and bidirectional movement state, the number of clustered pedestrians in the model was statistically analyzed before and after optimization for a certain time frame. The fixed parameters are as follows: static field parameter

= 3.0, dynamic field parameter

= 0.3, and dynamic field diffusion and decay parameters α = β = 0.2. The sensitivity parameters for the repulsion field

are set to 0 and 1.0, with the simulation results illustrated in

Figure 17.

As can be seen from

Figure 17, under the conditions of free evacuation, unidirectional movement, and bidirectional movement, the number of clustered pedestrians after optimization with the addition of the exclusion field is significantly reduced. This observation is more in line with the real-world pedestrian traffic scenarios that avoid random collisions.

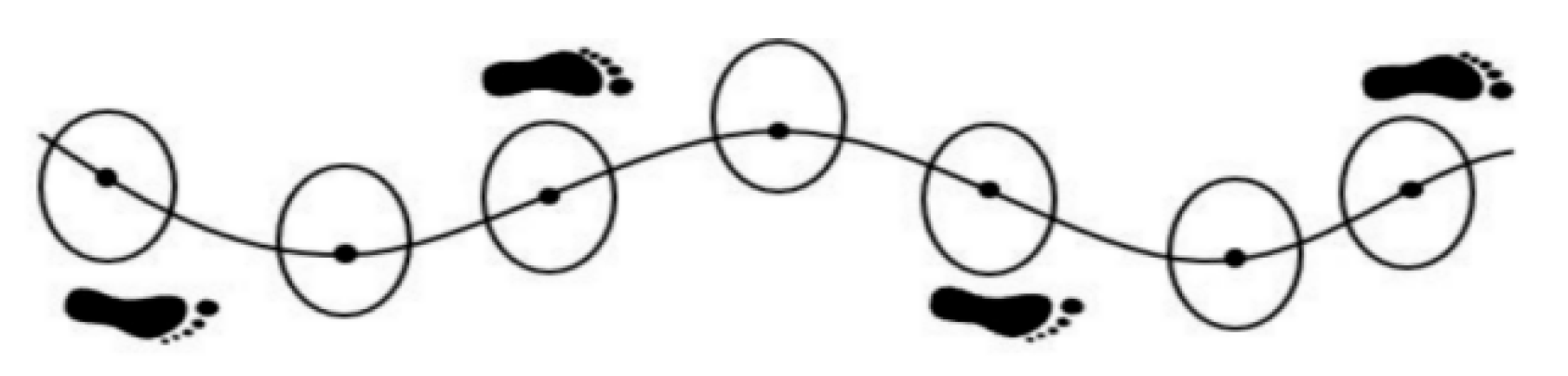

4.3.3. Pedestrian Movement Trajectories

Utilizing the pedestrian flow model, the spatial coordinates of pedestrians on the overpass are recorded for each time step. Connecting these coordinates provides the trajectory of pedestrian movement.

Taking the trajectory of the pedestrian flow model on the overpass with an initial number of

N = 20 as an example, where the static field parameter

is 3.0, the dynamic field parameter

is fixed at 0.3, and the dynamic field diffusion and decay parameters are α = β = 0.2. The sensitivity parameter for the repulsion field is set to one.

Figure 18 displays the trajectories of pedestrians under free evacuation, unidirectional movement, and bidirectional movement for an initial number of

N = 20. The left side of the figure shows the initial distribution positions of pedestrians, while the right side illustrates the trajectory map of pedestrians.

Figure 18 depicts the simulated optimal egress routes for pedestrians. These paths are derived by integrating the influences of the surrounding environment with interpersonal interactions, thereby more authentically and accurately capturing the movement trajectories and socio-behavioral mechanisms.

5. Analysis of Vibration Response of Pedestrian Overpass Under the Action of Crowd Loads

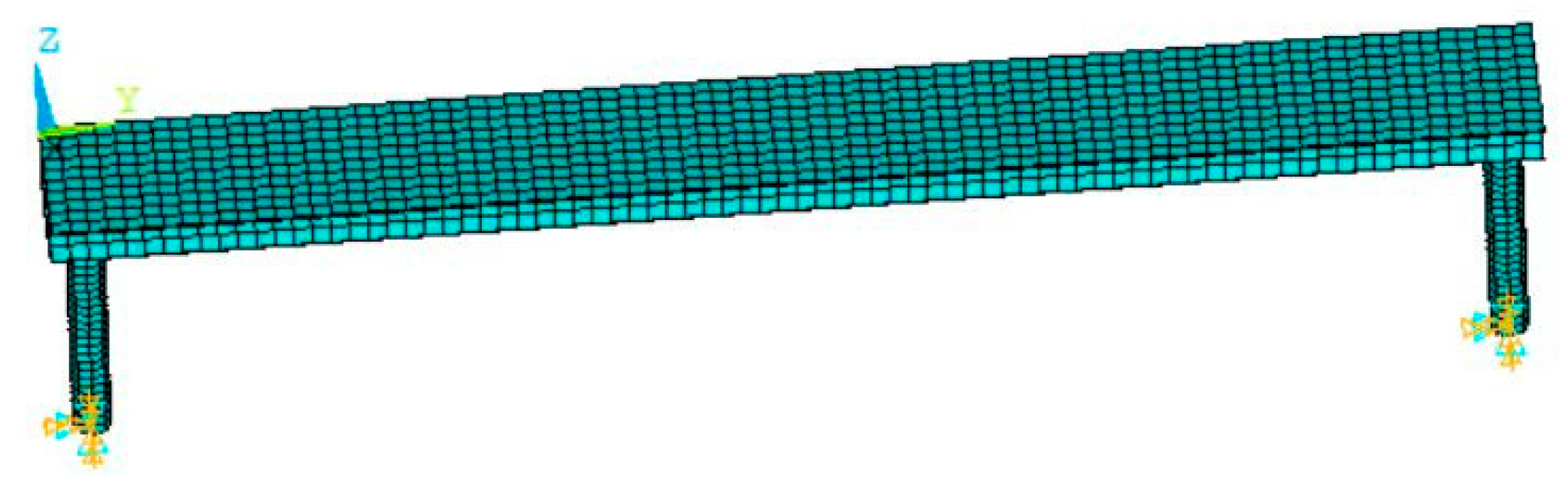

5.1. Model Analysis

An ANSYS 2022R1 finite element model for the pedestrian bridge is established. The main beam dimensions of the pedestrian bridge are the same as those in the experiment.

The pier parameters are as follows: pier height is 5 m of C30 concrete. Circular cross-section for the bridge pier with a radius of 0.4 m. The main beam uses Q235 steel with an elastic modulus of 210 GPa, unit mass ρ = 7800 kg/m

3, shear modulus G = 80 GPa, and Poisson’s ratio of 0.33. For C30 reinforced concrete, unit mass is 2700 kg/m

3 and Poisson’s ratio is 0.2. The finite element model of the pedestrian bridge is shown in

Figure 19.

Cell and element property division: In the ANSYS model, the main beam has a grid size of 0.4 m and uses a shell181 element to simulate the box beam element. The pier has a grid size of 0.2 m and uses beam188 element for simulation.

Boundary conditions: The bottom of the pier is fully fixed. The pier is simply supported and connected to the main beam, with shared nodes at the junction of the box beam plate elements.

Rayleigh damping can be calculated using Equation (14).

For the mass damping coefficient

and the stiffness damping coefficient

, both are constants and can be obtained through Equation (32).

The damping ratio

of the structure can be represented using the Rayleigh damping constants.

Through modal analysis with a damping ratio of 0.02, the first-order frequency ω1 for the pedestrian bridge structure is calculated to be 0.68 Hz and the second-order frequency ω2 is 1.12 Hz. By substituting these values into Equations (14), (32) and (33), damping matrices of the pedestrian bridge are determined. These matrices are then incorporated into the human–bridge interaction equation. Coupled with the pedestrians’ walking load and the trajectory of pedestrians on the bridge, a step-by-step solution using the Newmark-β method is employed, resulting in the vibration response of the pedestrian bridge structure.

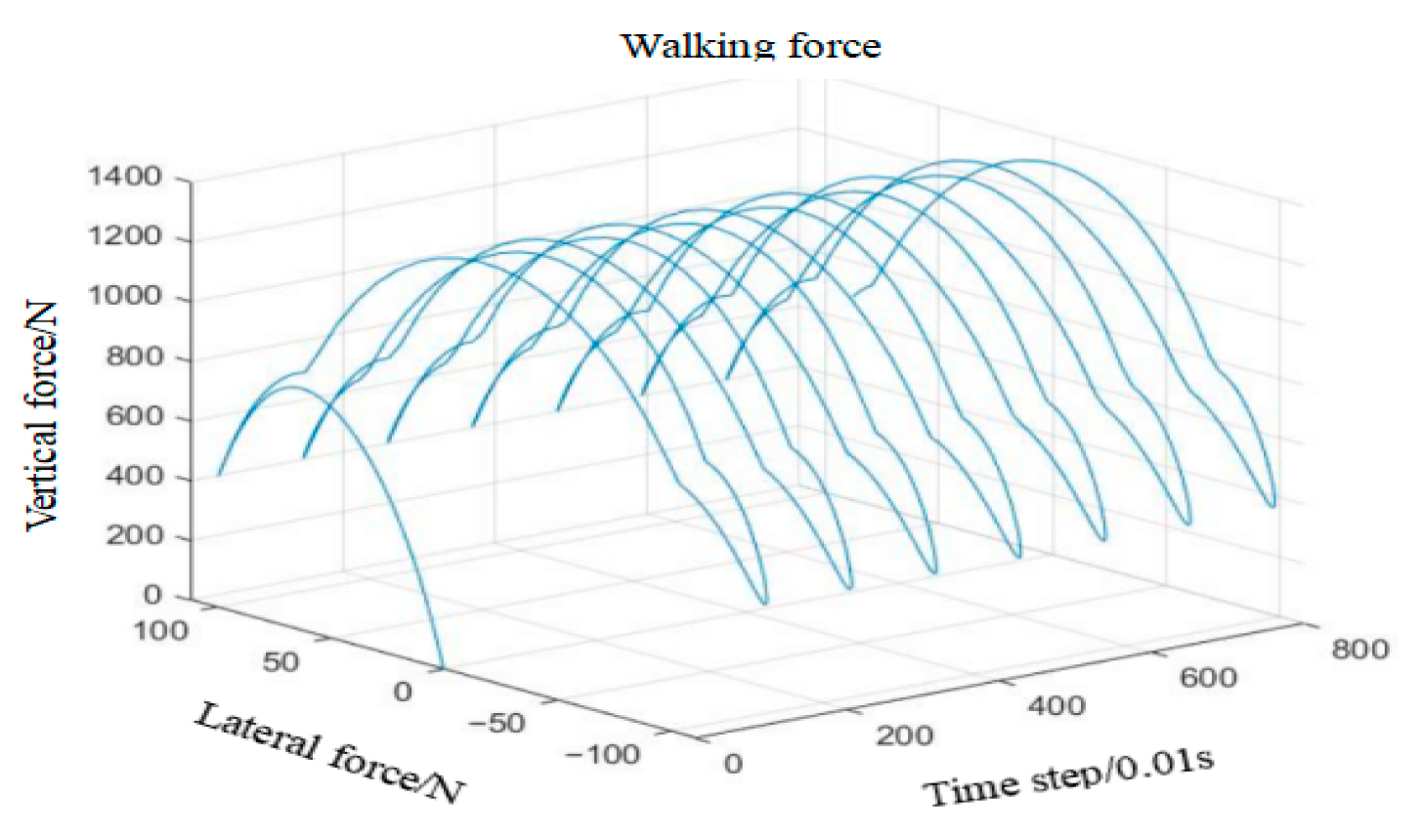

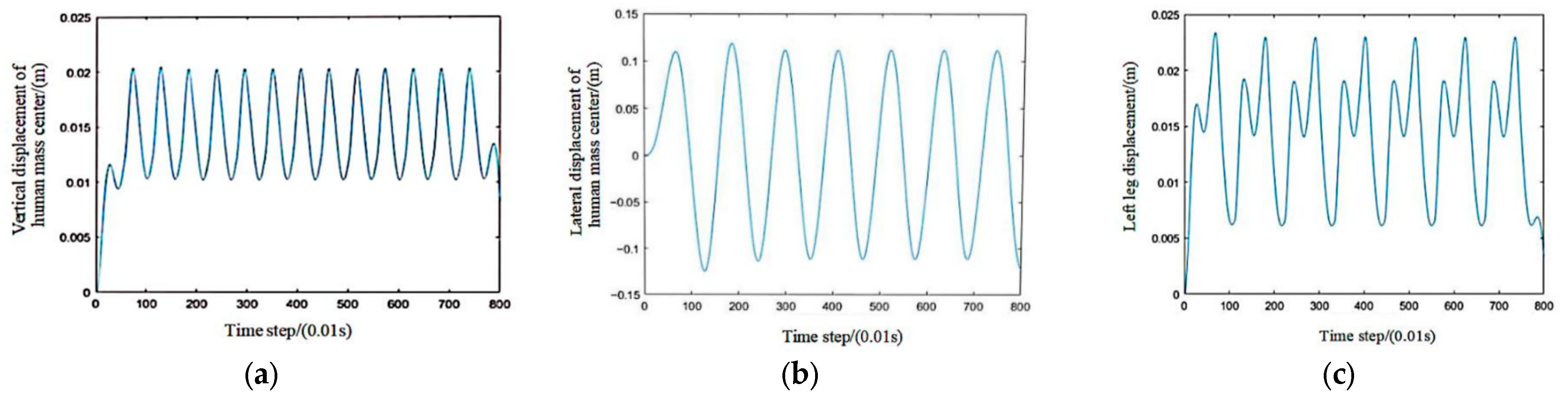

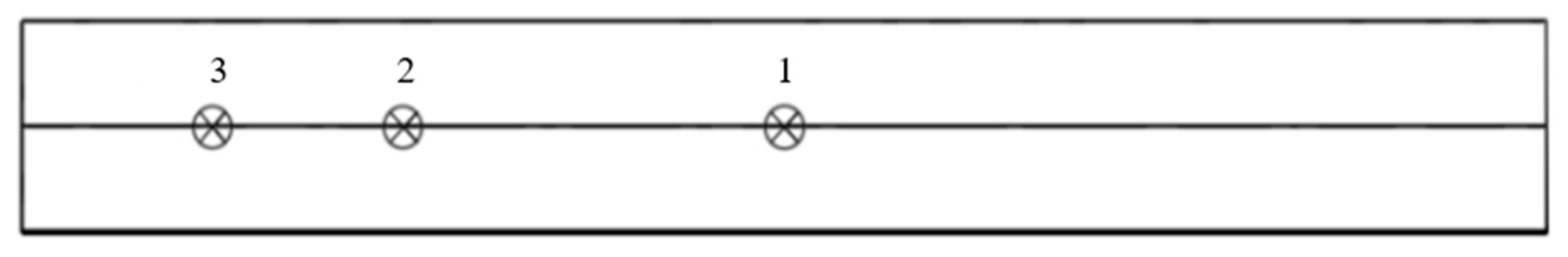

By establishing a numerical model of the pedestrian overpass, the acceleration response of the pedestrian overpass is selected as the output. The influence of different parameters such as pedestrian step frequency, step length, pedestrian density, and walking path on the bridge’s vibration response is analyzed.

With 40 pedestrians moving unidirectionally, the pedestrian weight follows a normal distribution N (700, 145) (N). Since the step size follows a normal distribution N (0.71 and 0.0071), we set the step size at 0.8 m in this chapter and the step speed is

,

= 40,000 N/m,

= 31,000 N/m,

= 1500 N/m,

= 500 N·s/m, and

= 7500 N·s/m,

= 260 N·s/m. The step frequencies are taken as 1.6 Hz, 2.0 Hz, and 2.4 Hz, respectively, as shown in

Table 5. The vibration measurement points are selected at the midpoints of the 1/2, 1/4, and 1/8 spans of the pedestrian overpass, labeled as Measurement Point 1, Measurement Point 2, and Measurement Point 3, respectively, as shown in

Figure 20.

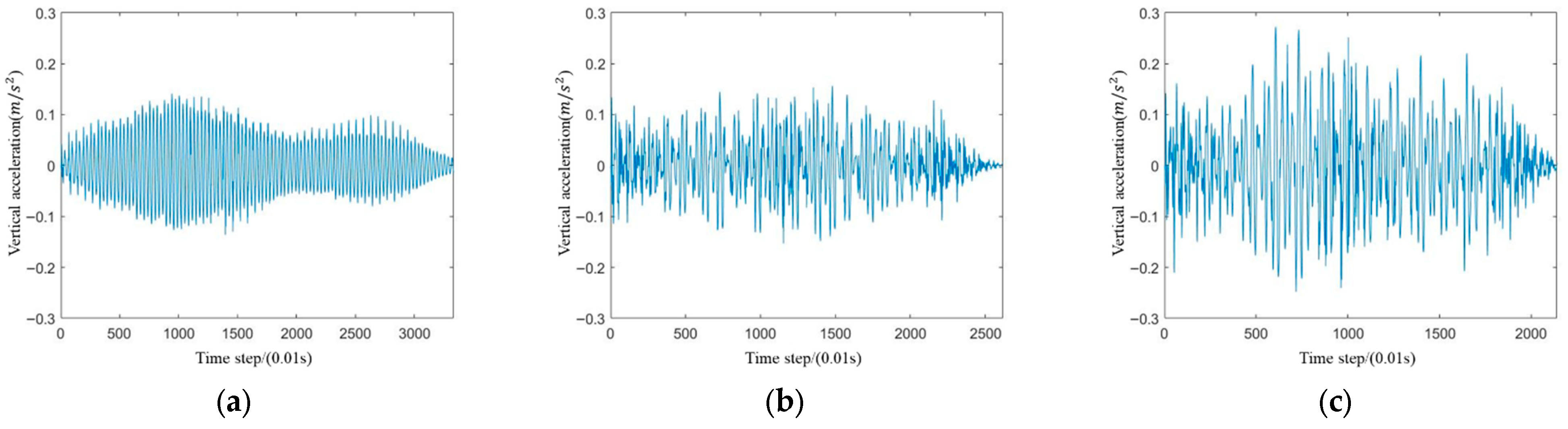

5.2. Impact of Pedestrian Step Frequency

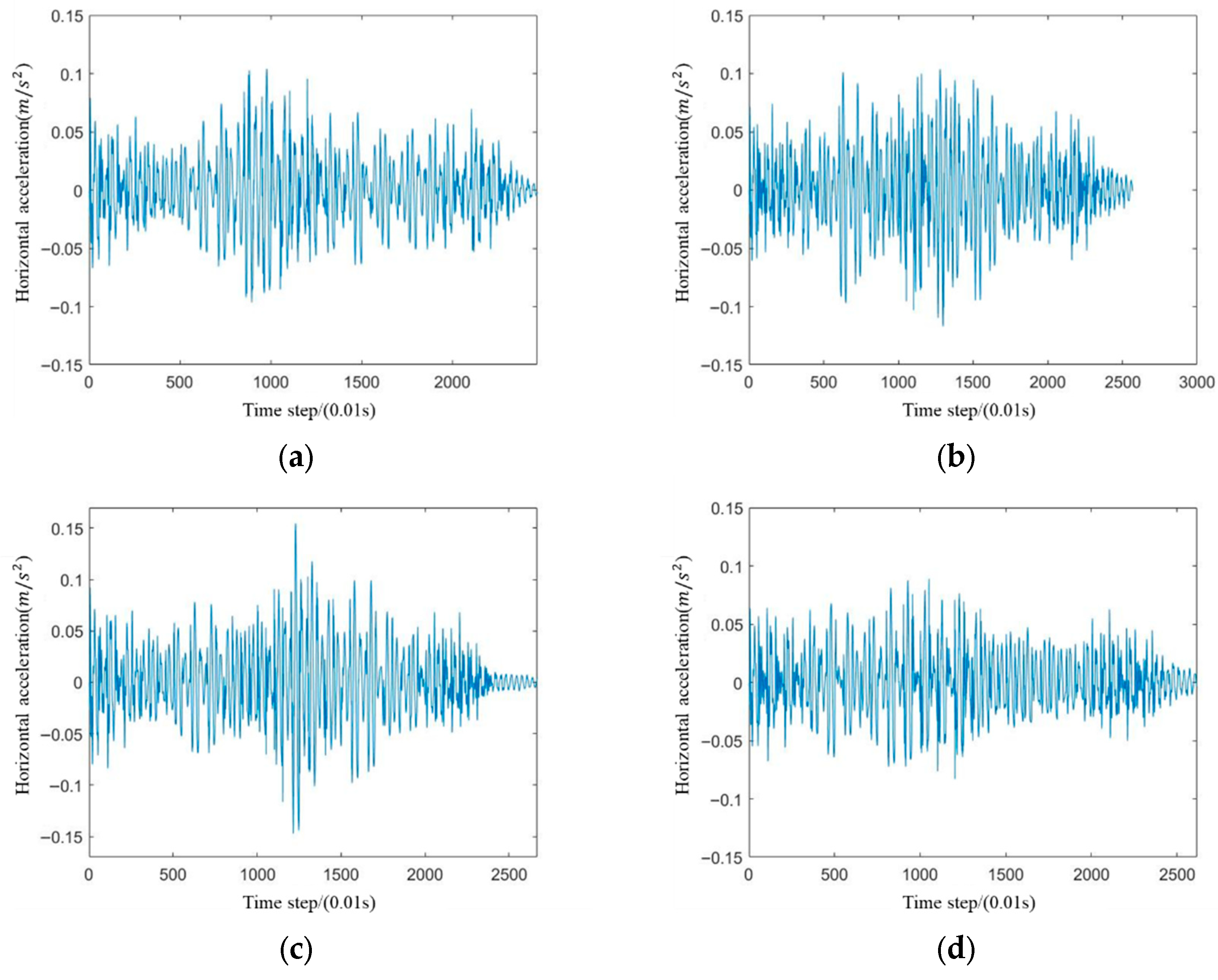

With other conditions remaining unchanged, step frequencies of 1.6 Hz, 2.0 Hz, and 2.4 Hz are selected. The vertical acceleration response at Measurement Point 1 is analyzed.

Figure 21 shows the acceleration time history curves at Measurement Point 1 for the three step frequencies.

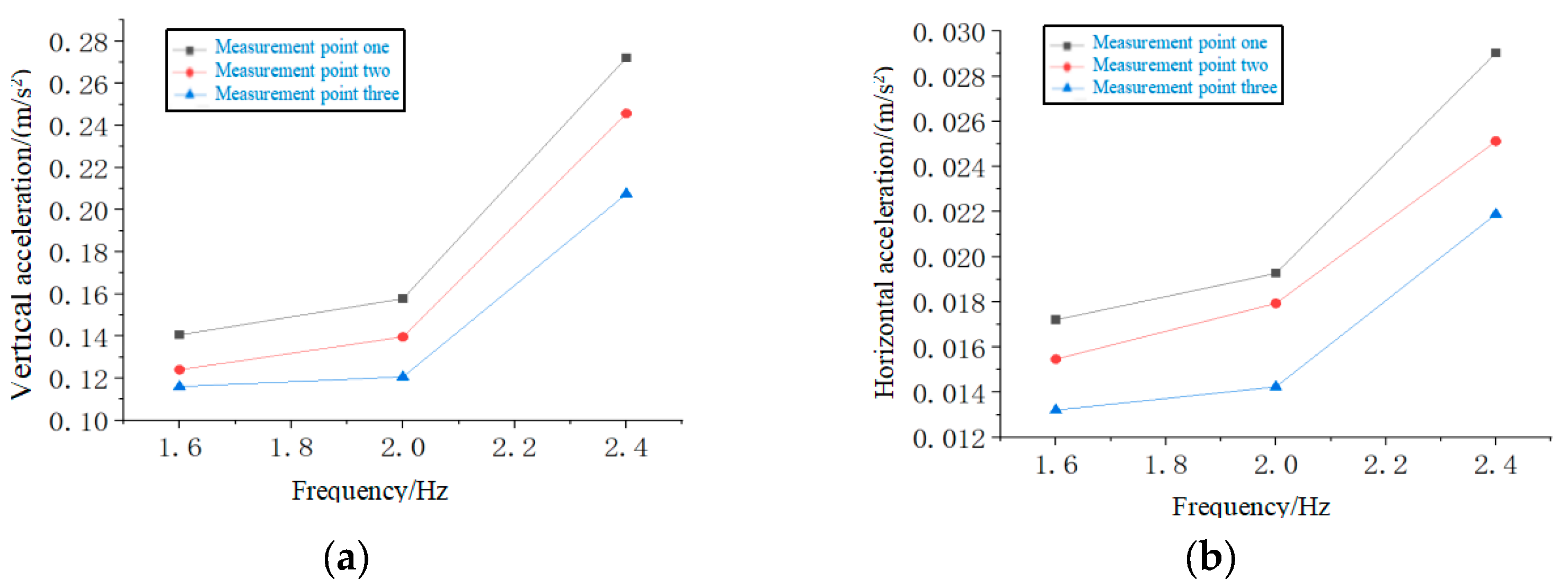

Table 6 and

Table 7 present the maximum vertical and horizontal acceleration values, respectively, at each measurement point for different step frequencies.

Table 6 shows that at all measurement points, the maximum vertical acceleration significantly increases when the accompanying frequency increases from 1.6 Hz to 2.4 Hz. At the mid-span position, the acceleration jumped from 0.141 m/s

2 to 0.272 m/s

2, showing an increase of nearly two times more. This indicates that a higher frequency of pedestrian steps will cause more intense vertical vibrations of the pedestrian bridge.

Similarly to the vertical acceleration, the maximum horizontal acceleration at all measurement points increases with the increase in the person’s frequency. At the mid-span position, the horizontal acceleration rises from 0.017 m/s2 to 0.029 m/s2, reflecting that the horizontal vibration excitation significantly intensifies with the increase in the step frequency.

During the walking process, the vibration responses at different measurement points vary for pedestrians. Across different frequencies, the vertical and horizontal acceleration responses at Measurement Point 1 are the highest. This is attributed to the fact that Measurement Point 1 corresponds to the midpoint of the bridge deck. Conversely, the vibration response at Measurement Point 3, which corresponds to the 1/8 span, is the least pronounced.

Figure 22 displays the variations in vertical and horizontal acceleration peak values at different measurement points for the three different step frequencies.

As can be seen from

Figure 22, under the condition that other factors remain unchanged, the vertical and horizontal accelerations at each point on the bridge deck increase with the increase in the frequency of the pedestrian steps. This is because when pedestrians cross a pedestrian bridge at a higher step frequency, their speed will also increase, which will cause the vibration of the pedestrian bridge to be amplified.

5.3. Impact of Pedestrian Density

With a selected pedestrian step frequency of 1.8 Hz and keeping other conditions constant, the number of pedestrians is chosen to be 26, 39, 51, and 64 individuals. The corresponding crowd densities are 0.2 person/m

2, 0.3 person/m

2, 0.4 person/m

2, and 0.5 person/m

2, respectively. The conditions are presented in

Table 8.

Selecting the most unfavorable position, the vertical acceleration response at Measurement Point 1 is analyzed.

Figure 23 presents the vertical acceleration time history curves at Measurement Point 1 for the four different pedestrian densities.

Table 9 provides the peak values of vertical and horizontal accelerations under varying numbers of pedestrians.

Figure 23 and

Table 9 show that as the number of pedestrians increases from 26 to 51, the peak of mid-span vertical acceleration increases from 0.1016 m/s

2 to 0.1544 m/s

2 and the peak of mid-span horizontal acceleration increases from 0.01422 m/s

2 to 0.01668 m/s

2. This indicates that within a certain range, an increase in pedestrians enhances the vertical and horizontal vibration excitation of the pedestrian bridge.

When the number of pedestrians further increased to 64, the peaks of vertical and horizontal acceleration dropped to 0.1068 m/s2 and 0.01458 m/s2, respectively. This indicates the existence of a critical pedestrian density; beyond this density, the mutual repulsion and motion adjustment of pedestrians reduce the synchrony of pedestrian loads, thereby alleviating the vibration response.

The data show that pedestrian density has a significant impact on both the vertical and horizontal vibrations in the mid-span of pedestrian bridges. There is a critical density threshold. Below this threshold, an increase in the number of pedestrians will intensify the vibration. Beyond this threshold, due to the adjustment of pedestrian behavior, the vibration will decrease.

6. Discussion

While the integrated model presented in this study demonstrates a credible ability to simulate pedestrian-induced bridge vibrations and offers valuable insights into the role of behavioral preferences, it is imperative to acknowledge its limitations to properly contextualize the findings and guide future research.

A primary limitation of this study is the absence of systematic sensitivity analysis. The model’s predictions rely on a set of predetermined parameters, including a structural damping ratio and the sensitivity parameters within the cellular automata model. The extent to which variations in these parameters influence the key results remains unquantified. Future work must include a comprehensive sensitivity analysis to evaluate the model’s robustness, identify the most influential parameters, and provide a margin of uncertainty for the predictions.

The interpretation of the results would be strengthened by a formal assessment against established vibration serviceability criteria. Although the natural frequencies of the bridge (0.68 Hz and 1.12 Hz) were identified, a detailed evaluation of the potential resonance risk with the harmonic components of pedestrian walking forces was not fully conducted.

As the number of pedestrians on the bridge increases, the changes in horizontal acceleration of the bridge are not as pronounced as those in vertical acceleration. This is because, even though the number of pedestrians increases on the bridge, they do not walk in perfect synchronization. The random nature of pedestrians’ steps tends to counteract the lateral vibrations of the bridge. Pedestrian walking has different characteristics; this work will be studied later.

7. Conclusions

The paper establishes a multi-degree-of-freedom bipedal dynamic model of the human body that considers both lateral and vertical movements. Furthermore, a pedestrian flow trajectory model is developed using the principle of cellular automata. This model is applied to a pedestrian overpass to derive the vibration response patterns of the overpass during crowd evacuation. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Through comparison and validation with existing research results and empirical data, the accuracy of the single-person bidirectional multi-degree-of-freedom biomechanical model established in this study and the pedestrian movement path derived using the cellular automaton principle, which considers static fields, dynamic fields, and repulsion fields to simulate interactions between pedestrians, is confirmed.

(2) In this paper, cellular automata model is applied, combined with social attributes of pedestrians, and the influence of environmental factors on pedestrian crossing path is considered. The algorithm can accurately predict key time nodes and pedestrian routes in the evacuation process and can effectively solve complex crowd evacuation scenarios.

(3) During pedestrian movement, significant clustering of two or more people can occur. Different pedestrian paths also affect the loading on the bridge structure. After incorporating a repulsion field into the cellular automaton model for optimization, this clustering phenomenon is notably improved, making it more consistent with real-world scenarios.

(4) Numerical results indicate that when pedestrian density is low, there is a strong positive correlation between pedestrian movement time and the number of pedestrians. However, when the pedestrian density exceeds a certain threshold, due to crowding and interactions between pedestrians, the correlation between movement time and the initial number of pedestrians weakens, and the vibration response at the midpoint of the bridge decreases.

(5) With an increase in pedestrian walking frequency, the acceleration responses in both the vertical and horizontal directions at the midpoint of the pedestrian overpass increase. Moreover, the rate of increase is faster when the pedestrian frequency is higher.