Abstract

Architectural discourse is a specialised language whose key terms shift with context, which complicates empirical claims about meaning. This study addresses this problem by testing whether a rigorously audited, reproducible NLP framework can recover a core theoretical distinction in architectural language, specifically the conceptual versus physical split, using Japanese terms as a focused case. The objective is to evaluate contextual embeddings against static baselines under controlled conditions and to release an end-to-end pipeline that others can rerun exactly. We assemble a ~1.98-million-word corpus spanning architecture, history, philosophy, and theology; train Word2Vec (CBOW, Skip-gram) and a fine-tuned BERT on the same sentences; derive embeddings; and cluster terms with k-means and Agglomerative methods. Internal validity is assessed using the Adjusted Rand Index against a phenomenological gold standard split; external validity is correlated with WordSim-353; robustness is examined through a negative-control relabelling and a definitional audit comparing FULL and CLEAN corpora; seeds, versions, and artefacts are pinned for exact reruns in the archived environment; and identity across different hardware is not claimed. The study finds that BERT cleanly recovers the split with ARI 0.852 (FULL) and 0.718 (CLEAN). BERT and CBOW show no seed variation. Both Word2Vec models hover near chance, but Skip-gram shows instability across seeds. We provide a transparent, reusable methodology, with released assets, that enables falsifiable and scalable claims about architectural semantics.

1. Introduction

Architectural discourse forms a distinct linguistic domain where technical vocabulary, abstract reasoning, metaphor, and interpretations coexist to define how the built environment is conceived and described. The meaning of architectural terms is rarely fixed, often depending on context, philosophy, and cultural lineage. Words such as the Japanese “Ma” (間) or “Yohaku” (余白) are good examples of how simple definitions cannot illustrate how spatial or aesthetic notions are, since their significance lies in relational and interpretative structures.

Architectural history does not focus solely on buildings; a substantial body of writing shapes the field by arguing with and defining itself, from ancient treatises to modern critiques [1,2]. For a long time, scholars have employed interpretive methods, such as hermeneutics and semiotics, to uncover meaning in these texts, as well as in buildings themselves [3,4,5,6]. Some approaches, drawing on phenomenology, discuss architecture in terms of lived experience, employing a language of “dwelling” that technical descriptions cannot adequately represent [5,6]. Interpretive approaches to architectural meaning have followed different paths; some treat buildings as a language, using semiotics to decipher them as a system of signs communicating through cultural codes [3]. Drawing on phenomenology, others have instead explored architecture’s poetic and psychological meaning, analysing intimate spaces as vessels for memory, imagination, and lived experience [7]. Thinkers such as Venturi, who examined the communicative power of buildings, and Rossi, who linked city forms to collective memory, have treated architecture as something to be read [8,9]. This linguistic richness has long challenged systematic study, leading architectural theory to traditionally rely on interpretative frameworks, such as close reading, hermeneutics, and phenomenology, to make sense of how architecture speaks about itself [10,11,12].

The field supports this approach as a fundamental practice. It provides a method for designers to interpret the “layered and complex” meanings of place and to “read” the semiotic meaning of a design as a “virtual building” before it is ever constructed [10,11]. Conversely, other researchers see this as a critical weakness. Cash, for example, argues that the field’s reliance on such non-systematic, interpretative approaches has led to a “scarcity” of robust theory and a lack of “scientific, theoretical, and methodological rigour”, ultimately weakening design research and limiting its impact when compared to more theory-driven disciplines [12]. These methods have produced deep insights, emphasising context, intention, and experience, but they are not easily scalable. They rely on individual judgement and are difficult to verify or reproduce. As a result, architectural scholarship remains rich in interpretation but poor in formal, transparent methods for examining how its own language operates [13].

Recent developments in computational research have changed how disciplines analyse text. The rise of Natural Language Processing (NLP) and large-scale text modelling has made it possible to trace conceptual structures and semantic shifts across extensive corpora [14,15]. Often described as part of a broader computational turn, these methods have started to influence the humanities, including art history and architectural studies. In architecture, they have been used to examine how computation is discussed in design discourse, to reveal thematic constellations in journals, and to analyse shifts in terminology linked to design technologies [16,17,18,19]. These studies demonstrate that computational models can extract empirical regularities across vast writing bodies, suggesting patterns that complement close reading and analysis. Yet they also raise significant methodological and philosophical concerns. The difficulty in verifying computational results often stems not from the models themselves being opaque, but from the method used to validate their outputs. Many human evaluation studies in NLP are effectively non-repeatable, with an estimated ~5% reporting enough publicly available design detail for accurate reruns, rising to ~20% with author assistance [20].

Furthermore, the field lacks standardised methods for quantified reproducibility assessment, meaning that comparisons between original and repeated experiments often rely on subjective judgments, leading to contradictory conclusions about a system’s performance [20,21]. Reproducibility is a known problem in NLP; models depend on changing environments, unshared code, and unlogged parameters, making replication almost impossible [22,23]. In the humanities, this problem becomes more acute because evidence often takes the form of interpretive arguments, rather than numerical performance. Without transparency and validation, computational approaches risk replacing interpretation with unexamined automation rather than extending critical understanding [24].

Architectural writing adds another layer of complexity. Its key terms, ma, engawa, tokonoma, or aware, carry multiple, context-dependent meanings. They often fuse spatial, temporal, and moral dimensions that resist literal translation [25]. A computational approach must therefore be capable of representing polysemy, the coexistence of multiple related senses within a single word. Static word embeddings, such as word2vec, assign each word type a single learned vector in a shared embedding space [26,27]. This approach assumes that a word’s meaning is stable, which is unsuitable for theoretical language where terms shift according to context or philosophical orientation [28,29].

On the other hand, contextual models, such as Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT), produce token representations that depend on surrounding context, so the same word’s vector changes with its usage [30,31]. A sentence about ma in a discussion of emptiness produces a different embedding from one where ma describes rhythm or pause. This dynamic quality aligns with hermeneutic principles; meaning is not stored, but made through relation and use [10,11,12]. Choosing such a model is not merely a technical decision but a methodological alignment with architecture’s interpretative logic.

To make computational analysis credible for architectural theory, we must adhere to two key principles: reproducibility and validation. Reproducibility means that others can reconstruct the dataset, pipeline, and environment exactly as they were used, allowing for the verification of results [20,21,22,23]. Validation ensures that model behaviour can be tested and justified. This study introduces a reproducible computational framework that meets both standards while respecting the specific nature of architectural language. The framework operates on three validation layers. Firstly, internal validation: comparing clustering outputs against a theory-driven “gold standard” derived from established phenomenological classifications, using a metric such as the Adjusted Rand Index [32]. Secondly, to verify that the models learn coherent relationships beyond the corpus, as an external validation, the results are tested using a general semantic benchmark (WordSim353) [33,34]. Thirdly, as recent research demonstrates, “Large Language Models” may learn to exploit superficial patterns or dataset biases as “shortcuts” to make predictions, rather than engaging in deep semantic reasoning [35]. Thus, applying a robustness test diagnosis mitigates the risk of shortcut learning.

To test for this vulnerability, our framework includes a definitional audit that filters out dictionary-like sentences. The rationale is that a model could learn to associate a term with its explicit definition as a simple shortcut, bypassing the more complex task of inferring meaning from implicit contextual use. By evaluating the model on a corpus stripped of these explicit definitions, we can confirm that it has developed a robust, generalisable understanding. These procedures make the framework transparent and reproducible, providing an empirical ground for theoretical interpretation.

This paper tests this framework by comparing a fine-tuned multilingual BERT model and conventional Word2Vec baselines. The corpus includes theoretical and historical architectural writings across multiple languages, curated to reflect diverse interpretative traditions. Logging all code, parameters, and random seeds ensures exact replication for the entire process [20,21,22,23]. The process has three steps to evaluate the results: alignment with phenomenological categories, general semantic coherence, and sensitivity to definitional filtering. The expectation is that BERT, with its contextual embeddings, will more accurately capture the nuanced semantics of architectural concepts than static models. Thus, the framework serves as a methodological tool and a philosophical experiment, testing whether computational models embody the contextual reasoning central to architectural thought. The ambition is not to mechanise interpretation but to build a reproducible bridge between quantitative analysis and humanistic reading.

The research aim and scope of this paper is to test whether a contextual language model, in an audited and fully reproducible pipeline, recovers theoretically grounded distinctions in architectural discourse more reliably than static baselines. The focus is on Japanese architectural terms. Evaluation uses three validation layers: (i) internal clustering against a phenomenological gold split with the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI); (ii) an external semantic similarity benchmark, WordSim-353; and (iii) a definitional audit comparing a FULL corpus with a CLEAN version that removes glossary-like sentences. The target is methodological, not ethnographic. The contribution is a validated, reusable framework for architectural semantics.

The central question of this study is whether contextual embeddings, under audited reproducible conditions, better capture the conceptual structure of architectural language than static embeddings.

The study aims to achieve the following objectives: (i) test whether contextual embeddings outperform static embeddings on the conceptual–physical split, measured by ARI; (ii) assess alignment between ARI and WordSim-353 to check whether a general benchmark predicts domain success; (iii) probe sensitivity via a negative-control relabelling of one class; (iv) audit definitional bias by comparing FULL and CLEAN corpora; (v) release an end-to-end reproducible pipeline.

The research gaps are as follows:

- Lack of audited, fully reproducible NLP pipelines in architectural semantics; most prior work uses ad hoc code with limited validation.

- Assumption that general similarity benchmarks stand in for domain adequacy without checking task alignment in this setting.

- Little auditing of definitional sentences that may inflate results; negative-control tests are typically absent.

- Limited reuse due to missing end-to-end assets and incomplete reporting.

The contributions of this work are outlined as follows:

- An audited, fully reproducible pipeline with released assets.

- Three validation layers: internal clustering against a phenomenological gold split using ARI; external semantic similarity via WordSim-353; a definitional audit comparing FULL and CLEAN corpora.

- An explicit negative control relabelling to test sensitivity to theoretical inconsistency.

- Evidence on task alignment between ARI and WordSim-353, clarifying when general benchmarks fail as proxies.

This study addresses the following research questions:

- RQ1: Do contextual embeddings (BERT) outperform static embeddings (Word2Vec) in distinguishing conceptual from physical terms?

- RQ2: Does performance on the general similarity benchmark, WordSim-353, predict performance on the theory-driven clustering objective, ARI, in this domain?

- RQ3: Can the framework detect a deliberate theoretical inconsistency introduced as a negative control?

- RQ4: How does removing definitional sentences, comparing FULL with CLEAN, affect model behaviour and stability?

These questions are associated with the following hypotheses:

- H1: BERT aligns more closely with the phenomenological taxonomy than Word2Vec on ARI.

- H2: The model rank ordering on ARI will not match the ordering on WordSim-353; the contextual model will lead on ARI, while a static baseline may appear competitive on WordSim-353.

- H3: After removing definitional sentences, performance remains within a pre-specified tolerance, ∆ARI ≤ 0.20, indicating reliance on contextual rather than definitional cues.Note: H1 is confirmatory; we treat RQ2 and H2 as theory-motivated and treat them as exploratory analyses of task alignment.

This paper is presented in five sections. Section 2 outlines the corpus, preprocessing, and models, and defines the three validation layers, including negative control relabelling and the definitional audit. Section 3 reports clustering alignment, benchmark results, and robustness checks. Section 4 interprets findings and outlines limitations and implications for architectural theory. Section 5 concludes and outlines extensions to broader corpora.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Corpus Creation and Composition

A corpus of ~1.98 million words in the English language was compiled from 845 websites to provide diverse interpretative contexts for polysemous architectural terms, drawing on architecture, history, philosophy, and theology.

The process of data mining began with the search term “architecture” in major online encyclopaedias (Britannica and Wikipedia). From each entry, the text collection continued by following hyperlinks recursively to related topics, including philosophy, religion, aesthetics, and history. The hyperlink chase excluded proper nouns (for example, cities and countries) and off-topic technical subfields (for example, naval or computational architecture). For each page, we kept only the main body prose and any technical figure captions, discarding navigation text, tables, and purely illustrative captions. For every page, we logged the URL, title, site, access date (July 2025), and a content checksum.

This crawl-and-expand strategy was designed to create a general corpus spanning architecture, history, philosophy, and theology, aiming to create a rich, multi-layered “interpretative context” that mimics the hermeneutic interplay in architectural discourse. This approach allows polysemous Japanese terms (such as “Mu” or “Ma”) to emerge relationally, testing whether models like BERT can dynamically infer conceptual versus physical nuances from surrounding themes (e.g., phenomenology in theology or spatial philosophy in history), rather than relying on rote domain-specific training.

The corpus was chosen by design to establish a temporal benchmark that captures representations of Japanese architectural terms as of July 2025. These prioritising, dynamic online encyclopaedias evolve through ongoing editorial updates and community contributions. This approach intentionally introduces variability in the exact corpus content across reproductions, as web sources are subject to change over time. However, reproducibility is preserved through the method detailed in the public repository, which includes scripted crawls, seed queries, recursion depth, and the logging of timestamps, checksums, and configurations. Future studies can leverage this snapshot to track longitudinal shifts in linguistic and informational portrayals of these terms, assessing how cultural interpretations adapt in digital discourse.

Ten peer-reviewed papers were manually added to introduce technical vocabulary and formal prose, broadening stylistic and disciplinary coverage. The search for the paper was run in J-STAGE and ProQuest (Scholarly Journals) using the query “Japanese/space/Engawa”. Inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed journal articles containing at least one target term (for example, engawa, ma, mu, shakkei) in the title, abstract, or main text. From the eligible set, we drew a complete random sample of ten articles to minimise selection bias while diversifying venues and registers. These papers were used solely as corpus text and did not influence the determination of labels or evaluation metrics.

The resulting corpus encompasses a range of registers, including descriptive, theoretical, and functional registers, such as encyclopaedic exposition, historical narrative, philosophical commentary, and architectural description. Deliberately retaining this variety ensures that the models have enough diverse materials to capture the dual nature of the Japanese architectural lexicon, encompassing both physical and aesthetic aspects, through emergent semantic relations within the general corpus. The study focuses on 28 traditional Japanese architectural terms: ma (間), mu (無), wabi (侘), sabi (寂), wabi_sabi (わびさび/侘寂), en (縁), engawa (縁側), shōji (障子), fusuma (襖), tokonoma (床の間), chigaidana (違い棚), doma (土間), genkan (玄関), tomeishi (止石), ikezuishi (いけず石/行けず石), shakkei (借景), roji (路地), torii (鳥居), shimenawa (注連縄), tsuboniwa (坪庭), byōbu (屏風), hisashi (庇/廂), haiden (拝殿), sandō (参道), aware (哀れ), honden (本殿), chashitsu (茶室), and karesansui (枯山水). A complete glossary of all 28 terms, with definitions, is provided in Appendix A.

The full corpus manifest and analysis scripts are available in the public repository referenced in the Data Availability Statement. Each execution logs corpus checksums and configuration hashes to guarantee reproducibility.

2.2. Two-Corpus Design: FULL vs. CLEAN

We created two parallel corpora that serve as an explicit experimental variable. Each corpus has tailored preprocessing based on the model’s specific computational needs. The FULL corpus comprised 1,975,868 words for BERT processing and 1,890,739 words for Word2Vec CBOW training; after definitional cleaning, the CLEAN corpus was reduced to 1,968,370 words for BERT (a 0.38% decrease) and 1,887,234 words for CBOW (a 0.19% decrease). FULL retains all sentences after basic normalisation (e.g., tokenisation and lower-casing). CLEAN was produced by a dedicated cleaning script that implemented the full pipeline described in the earlier version of this study: sentence segmentation, tokenisation, lower-casing and punctuation removal (for distributional training), lemmatisation and part-of-speech tagging, hybrid stop-word removal, and retention of Japanese tokens. Crucially, the script detects and removes definitional and glossary-like sentences using regular expressions over copular and appositive frames (e.g., “X is a Y,” “X refers to Y,” “X is defined as …,” “X means …,” “X, a Y”).

The optional patterns were stored in filters.yaml functions only as a safety layer, a secondary pass that catches residual definitional sentences missed by the cleaning script. They do not generate the CLEAN corpus themselves. Both corpora were used to train each model under identical hyperparameters, allowing for a direct paired comparison (Δ = CLEAN − FULL).

2.3. Model-Specific Preprocessing

BERT (bert-base-multilingual-cased): Preprocessing was conservative to preserve grammatical structure and long-range dependencies. While retaining case and punctuation, Japanese and English terminology were standardised via a normalisation map (e.g., “縁側” → “engawa”; “障子” → “shōji”). The Hugging Face model revision was explicitly pinned through the hf_revision argument; runs terminate if this tag is missing or set to main/latest. These procedures generated the BERT_FULL and BERT_CLEAN datasets.

Word2Vec (CBOW and Skip-gram): Distributional models receive more aggressive filtering to enhance local lexical density. The pipeline applies sentence segmentation, lower-casing, punctuation removal, lemmatisation, and part-of-speech tagging to retain {NOUN, PROPN, ADJ, VERB, ADV} while passing through Japanese tokens unaltered. Stop words combine spaCy defaults with a custom list (e.g./i.e.). These filtered texts form W2V_FULL and W2V_CLEAN.

2.4. Model Training and Configuration

2.4.1. Final Model Configurations

Word2Vec Models: We trained two models, Continuous Bag-of-Words (CBOW) and Skip-gram, from scratch using the gensim library. All runs employ deterministic, single-thread execution. Key parameters are drawn from config.yaml: vector size = 100; window = 9; epochs = 50; min_count = 3; learning rate decays linearly (0.01 → 0.0001); hierarchical softmax enabled, negative sampling disabled (hs = 1, negative = 0).

BERT Fine-Tuning: The bert-base-multilingual-cased model is fine-tuned for masked language modelling (MLM) using LoRA adapters applied to query, key, value, and output projections. Training hyperparameters are as follows: learning rate = 3 × 10−5; batch size = 32; epochs = 3; maximum sequence length = 128; warm-up ratio = 0.06; weight decay = 0.01; gradient accumulation = 2. The optimal checkpoint is selected automatically based on the lowest validation loss. All training is deterministic, and the exact model revision is pinned for full reproducibility.

2.4.2. Hyperparameter Selection and Justification

The final hyperparameters were not chosen arbitrarily. They were selected following a systematic grid search, which was combined with a qualitative validation to ensure model stability and analytic utility. The full search logs are documented in the project repository.

For BERT: The fine-tuning grid search included learning_rate (tested values: 5 × 10−5, 4 × 10−5, 3 × 10−5, 2 × 10−5, 1 × 10−5), per_device_train_batch_size (tested values: 16, 32), num_train_epochs (tested values: 1–3), and gradient_accumulation_steps (tested values: 1, 2). The search identified that the configuration with (‘learning_rate’: 3 × 10−5, ‘per_device_train_batch_size’: 32, ‘num_train_epochs’: 3, ‘warmup_ratio’: 0.06, ‘weight_decay’: 0.01, ‘max_length’: 128, ‘mlm_probability’: 0.15, ‘gradient_accumulation_steps’: 1) achieved the lowest validation loss (1.6598). However, a manual inspection of the training logs revealed that this model began to overfit after the second epoch. We therefore selected the gradient_accumulation_steps = 2 configuration. Under this setting, the model did not exhibit overfitting, resulting in a more stable and generalisable final model.

For Word2Vec: The grid search included vector_size (tested values: 75, 100, 125, 150), window (tested values: 3–20), alpha (tested values: 0.01, 0.015), and sg (tested values: 0, 1). The search for the lowest training loss identified vector_size = 75 as optimal, but with two very different windows: CBOW (‘vector_size’: 75, ‘window’: 20, ‘alpha’: 0.01, ‘epochs’: 50, ‘sg’: 0, ‘min_count’: 5, ‘hs’: 1, Training loss: 59,588,864), and Skip-gram (‘vector_size’: 75, ‘window’: 3, ‘alpha’: 0.01, ‘epochs’: 50, ‘sg’: 1, ‘min_count’: 5, ‘hs’: 1, Training loss: 67,559,304). However, a qualitative inspection of the top-performing CBOW model revealed a potential critical flaw; nearest-neighbour checks surfaced a single token, “kami”, as the top neighbour for all the target words except the target word “Mu”. In this corpus, that pattern could be meaningful, reflecting a broad cultural regularity, yet it could also be a hubness artefact amplified by large context windows and token frequency. Because the goal here is a robust, reproducible baseline rather than an investigation of that phenomenon, for the final models, we standardised on a moderate (‘min_count’: 3, ‘vector_size’: 100, ‘window’: 9) for both CBOW and Skip-gram. This decision, more importantly, suppresses the “kami” concentration and ensures a consistent and fair comparison between the CBOW and Skip-gram architectures.

2.5. Embedding Derivation and Clustering

BERT representations: For each target term, the script collects all sentences containing the token and computes the mean of non-special-token embeddings for each sentence. These sentence-level means are averaged across 100 randomly sampled contexts, producing one contextual vector per term.

Word2Vec representations: Static embeddings correspond to the type of vector learned during training.

Clustering: Embeddings are grouped into clusters (K = 2) using k-means and Agglomerative clustering. K-means runs with n_init = 50 and max_iter = 1000; Agglomerative clustering operates on cosine distance (pre-computed) with average linkage. Optional z-score scaling and L2 normalisation are enabled by default. Because ARI is label-invariant, no manual label alignment is required.

2.6. Evaluation Metrics and Analysis Plan

Primary metric: Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) between model clusters and the gold conceptual/physical classification.

Secondary metric: Spearman rank correlation ρ (rho) between model cosine similarities and human ratings on the WordSim-353 benchmark.

Paired analysis: Each metric is computed for FULL and CLEAN, and paired differences are reported as Δ = CLEAN − FULL.

Uncertainty and significance: For ARI, bootstrap confidence intervals utilise 2000 resamples, and permutation tests employ 5000 label shuffles. For WordSim-353, bootstrap confidence intervals are based on 10,000 resamples, and permutation tests utilise 1000 label shuffles.

2.7. Reproducibility and Artefact Management

Determinism is enforced throughout. The framework sets the seeds for Python 3.11.9, NumPy 1.26.4, and PyTorch 2.5.1 + cu121; forces single-threaded BLAS and single-threaded PyTorch CPU operations while leaving GPU execution enabled; trains Word2Vec with a single worker for determinism; disables TF32 fast paths; and logs all package versions, including CUDA driver metadata. Each run writes a machine snapshot, including the following:

- Code, configuration, and corpus SHA-256 hashes;

- Model and dataset manifests;

- Run-time environment details.

Artefacts are cached and reused when their hashes match, ensuring byte-identical results on identical hardware and software stacks. Cross-hardware numerical equivalence is not guaranteed due to differences in low-level floating-point operations.

Independent cross-environment check: In addition to deterministic settings and artefact logging, we verified output stability across three archived runs under two distinct Python stacks. The archived machine snapshots document materially different libraries, for example, Torch 2.5.1 with Transformers 4.56.0 versus Torch 2.2.2 with Transformers 4.51.3; yet, the pipeline reproduced the same ARI values and cluster assignments for BERT and CBOW on both FULL and CLEAN. Skip-gram likewise produced identical outputs across environments for any fixed seed; its variability arises only across seeds. The snapshots include configuration and code hashes, permitting a byte-level audit of all differences. This constitutes an environment-level reproducibility check beyond a single software setup. Byte-identical results across heterogeneous hardware are not claimed.

All code, corpora, YAML configuration files, and multi-seed run outputs used in this study are available in the public repository referenced in the Data Availability Statement.

2.8. Use of Generative AI

During the preparation of this study, the author used generative AI tools, including Google’s Gemini 2.5 Pro, OpenAI’s GPT-5, and Grok 4.0, to develop the Python script for the computational analysis pipeline described in this methodology. The author reviewed and edited all AI-generated output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

3. Results

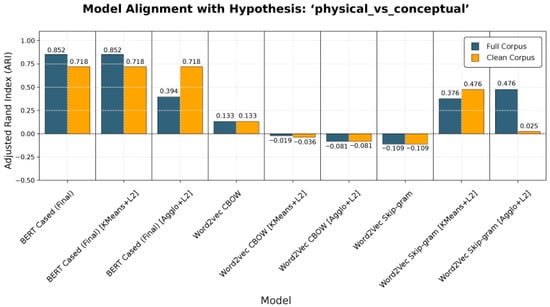

We report paired contrasts for each model under the two corpus conditions (Δ = CLEAN − FULL). Fine-tuned BERT aligns closely with FULL’s conceptual vs. physical gold split and remains strong on CLEAN. Removing definitional sentences reduces BERT’s separability by a modest margin while slightly improving Skip-gram on physical terms. External similarity shows corpus-dependent parity between BERT and Skip-gram. On CLEAN, WordSim-353 marginally favours Skip-gram; on FULL, fine-tuned BERT is slightly higher.

3.1. Pipeline Diagnostics and Validation

Before evaluating the primary hypotheses, we performed a series of diagnostic checks to validate the technical integrity of the experimental pipeline. These checks confirmed that the corpora were well-formed and that the training of all models was successful.

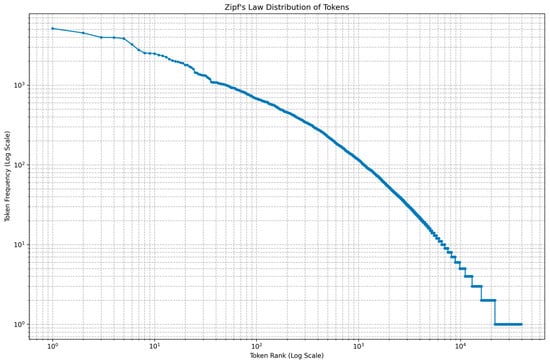

First, we examined the statistical properties of the corpora. The FULL and CLEAN corpora display normal Zipf-like frequency distributions (α ≈ 1.36; R2 ≈ 0.97), confirming that the text reflects natural language patterns and that no over-filtering occurred. These results verify that lexical frequency scaling remains intact after cleaning and that the corpora are statistically comparable in form (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Zipf’s law for token frequencies in the FULL and CLEAN corpora plotted on log–log axes. Curves overlap closely, α ≈ 1.36 and R2 ≈ 0.97, indicating no preprocessing artefacts.

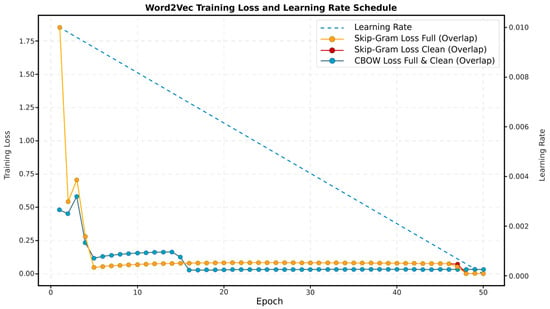

During training, both Word2Vec variants (CBOW and Skip-gram) showed stable optimisation curves with monotonic decreases in loss across all 50 epochs. The curves display no divergence or plateauing, indicating efficient convergence and balanced sampling. For instance, Skip-gram loss dropped dramatically from 18.51 M to 37.3 K on the FULL data, indicating successful learning (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Word2Vec training loss across 50 epochs for CBOW and Skip-gram on FULL and CLEAN. Loss decreases monotonically without divergence, e.g., Skip-gram drops from ~18.51 M to ~37.3 K on FULL, confirming stable convergence (curves overlap).

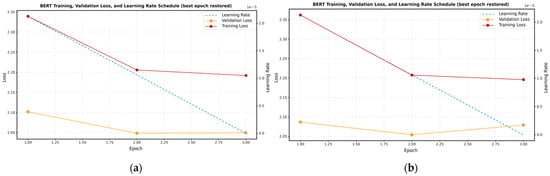

The BERT fine-tuning model also demonstrated successful learning. The fine-tuning process reached its minimum validation loss at epoch 3 in both corpora. For instance, in the CLEAN corpus, the validation loss reached its minimum of 2.06 in the third epoch, showing that the model effectively adapted to the domain-specific data. The validation loss curve shows that the model generalised well without overfitting (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

BERT fine-tuning validation loss curve for (a) FULL and (b) CLEAN corpus.

These diagnostics confirm that both corpora and all models behaved as expected during training. The data preserved natural lexical structure, and the models converged stably, ensuring that subsequent evaluation results are based on well-formed and properly trained embeddings.

3.2. Model Stability and Seed Control

3.2.1. Model Stability

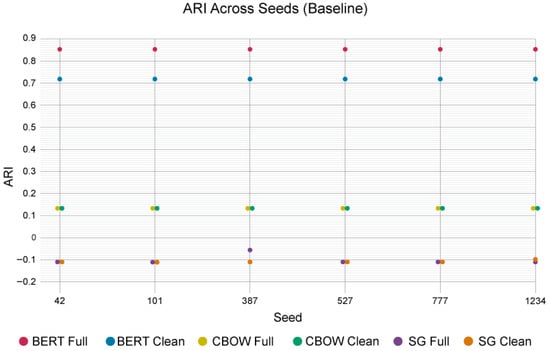

All experiments were conducted with fixed random seeds (42, 101, 387, 527, 777, 1234) to ensure reproducibility. These seeds govern model training (e.g., Word2Vec epochs, BERT fine-tuning), clustering (k-means/Agglomerative with n_init = 50, max_iter = 1000), and resampling (2000 bootstraps for ARI CIs; optional permutation tests). Evaluation emphasises the confirmatory physical versus conceptual hypothesis (active in config; binary split: conceptual = 0, physical = 1, for terms like ma = 0 vs. engawa = 1), as it benchmarks the recovery of grounded versus abstract distinctions. Figure 4 depicts ARI variability across seeds for baseline (plain) model k-means on the FULL and CLEAN corpora. Agglomerative and L2-scaled variants are not shown.

Figure 4.

ARI variation across six random seeds for the physical_vs_conceptual hypothesis, using baseline k-means, illustrates seed invariance for BERT and CBOW and instability for Skip-gram.

We quantify cross-seed stability using the mean across seeds, the sample standard deviation (SD), the 95% t-interval for the mean, and the observed range (minimum–maximum), with n = 6 seeds and df = 5. BERT was seed-invariant on both corpora: FULL ARI = 0.8520998174 (SD 0.0000; 95% CI [0.8520998174, 0.8520998174]; min–max: 0.8520998174 to 0.8520998174); CLEAN ARI = 0.7182341510 (SD 0.0000; 95% CI [0.7182341510, 0.7182341510]; min–max: 0.7182341510 to 0.7182341510). Under an independently versioned Torch and Transformers stack, BERT and CBOW reproduced the same ARI values and cluster assignments on both FULL and CLEAN. Skip-gram was identical across environments for a fixed seed, with variability confined to cross-seed differences (permutation p-values may differ slightly due to resampling).

CBOW was likewise seed-invariant and low: FULL ARI = 0.1325854156 and CLEAN ARI = 0.1325854156 for every seed (SD = 0.0000, min–max equal to the mean).

Skip-gram was materially seed-sensitive: FULL mean ARI = −0.1002356276 (SD 0.0225555476; 95% CI [−0.1239062232, −0.0765650321]; min–max: −0.10964219 to −0.0541947541); CLEAN mean ARI = −0.1078751940 (SD 0.0039660823; 95% CI [−0.1120367446, −0.1037136434]; min–max: −0.10964219 to −0.0997830566).

Cross-seed stability is summarised in Table 1 in Section 3.2.2. Complete per-seed results for all models and variants are in Appendix B.

Implementation note: BERT uses CLS-pooled last-hidden-layer embeddings from the multilingual-cased base model, selecting the model by validation loss. Differences for BERT and CBOW, therefore, reflect corpus filtering, not stochasticity.

3.2.2. Aggregates and Model Comparisons

Table 1 reports cross-seed aggregates for the baseline models on the physical vs. conceptual hypothesis. Formal model comparisons use paired tests across seeds, with one paired observation per seed. Because BERT and CBOW are seed-invariant, the paired differences are constant and strictly positive in every seed. Exact paired sign tests give p = 0.031 (two-sided, n = 6) for BERT > CBOW on both corpora. For BERT > Skip-gram, the per-seed differences are positive for every seed on both corpora, with a sign test p-value of 0.031. The probability of superiority is maximal in all three contrasts, with Cliff’s δ = 1.00. Mean paired differences are large: BERT–CBOW = 0.7195 (FULL) and 0.5856 (CLEAN); BERT–Skip-gram = 0.9523 (FULL) and 0.8261 (CLEAN). For completeness, CBOW > Skip-gram in every seed on both corpora (sign test p = 0.031, δ = 1.00). Repeated-measures ANOVA is inappropriate here because two groups have zero within-group variance. Non-parametric paired tests answer the reviewer’s request with the available per-seed replicates.

Table 1.

Baseline plain aggregates (n = 6).

Table 1.

Baseline plain aggregates (n = 6).

| Model | Corpus | Mean ARI | SD ARI | 95% CI | Min–Max | CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BERT | Full | 0.8521 | 0.000 | [0.8521, 0.8521] | 0.8521, 0.8521 | 0.000 |

| BERT | Clean | 0.7182 | 0.000 | [0.7182, 0.7182] | 0.7182, 0.7182 | 0.000 |

| CBOW | Full | 0.1326 | 0.000 | [0.1326, 0.1326] | 0.1326, 0.1326 | 0.000 |

| CBOW | Clean | 0.1326 | 0.000 | [0.1326, 0.1326] | 0.1326, 0.1326 | 0.000 |

| SG | Full | −0.1002 | 0.023 | [−0.1239, −0.0766] | −0.1096, −0.0542 | 0.225 |

| SG | Clean | −0.1079 | 0.004 | [−0.1120, −0.1037] | −0.1096, −0.099 | 0.037 |

SD = sample standard deviation across seeds; CI = 95% t-interval; Min–Max = observed range across seeds; CV = SD/|mean|.

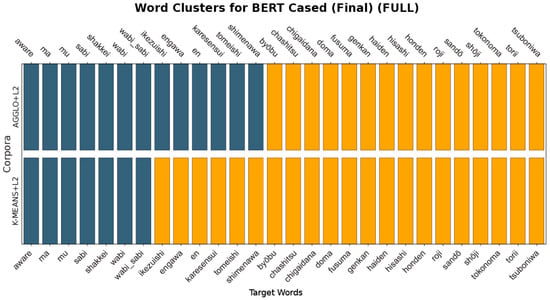

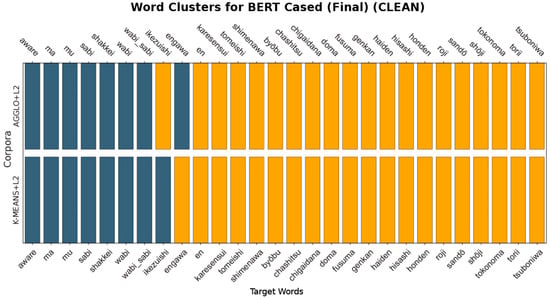

3.3. Corpus Effect: FULL vs. CLEAN, a Definitional Audit (Physical vs. Conceptual)

This subsection uses a single pre-specified seed (777) for the figures only. Cross-seed stability is reported in Section 3.2. For BERT and CBOW, the ARI is identical across the six seeds within each corpus (per-corpus seed invariance), so the choice of seed does not affect the reported FULL values or the reported CLEAN values. The difference between corpora for BERT (0.8521 on FULL vs. 0.7182 on CLEAN) is a corpus effect, not a seed effect. Skip-gram is not seed-invariant; therefore, we include seed 777 for comparability and provide cross-seed statistics in Section 3.2.

BERT: On FULL, k-means and k-means + L2 both reach ARI = 0.8521 (bootstrap 95% CI [0.5723, 1.0000], permutation p < 0.001, N = 2000). On CLEAN, the corresponding value is 0.7182 (bootstrap 95% CI [0.3701, 1.0000], p < 0.001). Agglomerative + L2 behaves differently at k = 2; it yields ARI ≈ 0.3945 on FULL, but rises to ≈ 0.7182 on CLEAN, matching k-means. All three BERT rows are invariant across the six seeds; on FULL, k-means = k-means + L2 = 0.8521 for every seed and Agglo + L2 = 0.3945 for every seed, while on CLEAN, k-means = k-means + L2 = Agglo + L2 = 0.7182 for every seed.

Why does the FULL gap close on CLEAN? K-means partitions by proximity to two centroids, which align closely with the gold classes in these embeddings, hence 0.8521. Agglomerative linkage merges by pairwise structure; with definitional sentences present, within-class sub-modes are merged before the class boundary at k = 2, depressing ARI to ≈ 0.3945. Removing definitional sentences reduces that within-class structure, so the first split aligns with the class boundary and Agglo + L2 converges to ≈ 0.7182, the same level as k-means. This jump in score is a clustering criterion effect, not seed noise.

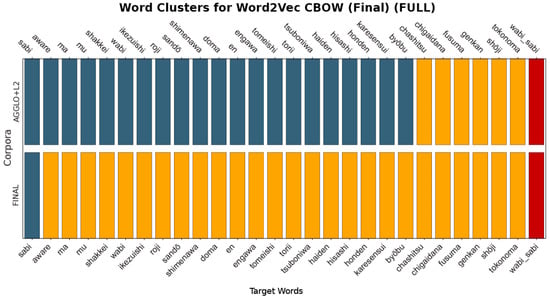

For the static baselines, CBOW maintains an ARI of approximately 0.133 on both corpora, showing minimal response to corpus cleaning. Skip-gram (base) remains below zero (−0.109 on FULL, −0.109 on CLEAN). Its normalised configuration (k-means + L2) notably improves to 0.476 on CLEAN, matching the Agglomerative + L2 variant. These behaviours reflect the interaction between metric normalisation and cluster structure, rather than changes in the underlying embeddings. The relative ordering between models remains unchanged (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Definitional Audit: Bar plots of ARI scores for static baselines (CBOW, Skip-gram base/normalised) on FULL corpus (blue) and CLEAN corpus (orange), showing corpus cleaning effects while preserving model ordering.

Interpretation: The definitional audit lowers contextual scores relative to FULL yet preserves model ordering. FULL inflates alignment because of definitional redundancy; CLEAN provides a more conservative, still positive, estimate of the same separation. The paired bars in Figure 5 summarise these corpus-level adjustments.

Definitional-bias check (same hypothesis, corpus filtering): Under the valid physical vs. conceptual hypothesis, BERT with Agglomerative + L2 rises from ARI ≈ 0.3945 on FULL to ≈0.7182 on CLEAN, an absolute +0.3240 and a +82.07% relative increase, identical across all six seeds. This shows that cleaning removes definitional noise and that performance moves in the expected direction independently of any label tampering.

3.4. Seed Comparison (Normal ARI Only)

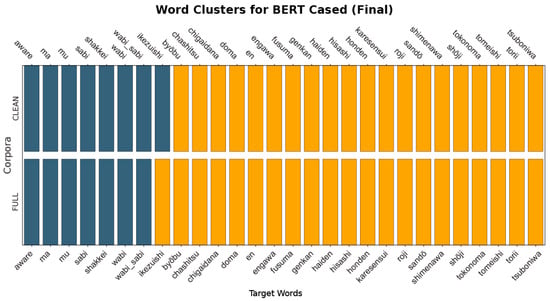

A qualitative inspection of the cluster assignments reveals the practical impact of the corpus audit and highlights the differing sensitivities of the clustering algorithms. With BERT under k-means, assignments on the FULL corpus align closely with the gold partition across all terms. On the CLEAN corpus, the same configuration yields only one “error”, with ikezuishi assigned to the conceptual cluster (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

BERT word-cluster assignments for FULL and CLEAN. FULL matches the gold split; on CLEAN, there is one mismatch, with ikezuishi assigned to the conceptual cluster.

In contrast, BERT paired with Agglomerative clustering demonstrated a dramatic improvement following the corpus audit. On the FULL corpus, the algorithm misclassified six physical terms as conceptual—engawa, shakkei, tomeishi, ikezuishi, shimenawa, and karesansui—resulting in a visibly poorer match to the gold labels (Figure 7), which explains the low ARI score of 0.3945.

Figure 7.

BERT clustering on the FULL corpus: k-means versus Agglomerative. K-means aligns closely with the gold labels; Agglomerative misclassifies engawa, shakkei, tomeishi, ikezuishi, shimenawa, and karesansui, explaining the lower ARI for that variant.

However, after cleaning, assignments converge on the k-means solution, with only minor residual disagreement (Figure 8). This marked improvement confirms the audit’s effectiveness, demonstrating that removing definitional sentences enabled the model to distinguish between categories more effectively based on contextual usage. This improvement is consistent with the rise in ARI (0.3945 → 0.7182) for this variant on the CLEAN dataset.

Figure 8.

BERT with Agglomerative clustering before and after the definitional audit. On CLEAN, assignments converge to the k-means solution and ARI rises from ~0.395 to ~0.718, confirming the audit’s effect.

In contrast, the static Word2Vec models do not recover a stable conceptual–physical split. They were largely unable to produce meaningful clusters. On FULL, the CBOW model, for example, failed to distinguish between the categories and collapsed toward a single dominant group under both clustering methods (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Word2Vec CBOW clustering on the FULL corpus. Both base and Agglomerative configurations collapse towards a single group, failing to separate conceptual from physical terms.

Skip-gram, on the other hand, shows partial structure only under normalised variants: Agglomerative + L2 on FULL and k-means + L2 on CLEAN display visible two-way partitions (Figure 10). Still, these remain weaker than the contextual model and are configuration-dependent. In these specific conditions, each of the clustering models achieved a degree of separation that, while significantly inferior to BERT, was better than chance.

Figure 10.

Word2Vec Skip-gram with normalisation. Partial two-way separation is observed in Agglomerative + L2 on FULL and in k-means + L2 on CLEAN, yet its performance remains weaker and configuration-dependent compared to BERT.

These figures document the cluster memberships used in the quantitative results: BERT reproduces the reference partition with near-perfect accuracy under k-means and improved agreement under Agglomerative after cleaning. Static baselines fail on the full corpus and only show limited, variant-specific separation on the clean corpus. Something to note is that “wabi_sabi” was not included in any of the clustering. This exclusion occurred in both corpora. The immediate cause was a preprocessing mismatch; the script expects a normalization_mapping in filters.yaml, but the filters file defines normalisation, so no rule ever collapsed “wabi-sabi” or “wabi sabi” to “wabi_sabi”. In addition, the whitelist allows hyphens but not underscores, so underscores are stripped during token cleaning. This behaviour in tokenisation means that Word2Vec never saw a single token “wabi_sabi”, and the clustering step had nothing to place for that key. By contrast, the BERT pathway still produced a vector because it gathers any sentence that literally contains the target string, encodes those sentences with WordPiece, and averages final-layer token vectors across contexts, which survives out-of-vocabulary surface forms and brittle normalisation, a small, telling case where the contextual model carries the analysis.

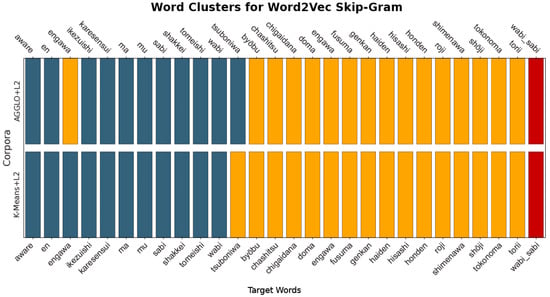

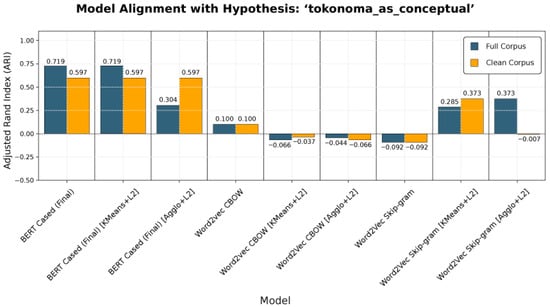

3.5. Hypothesis Sensitivity: A Negative Control Test (Tokonoma as Conceptual)

We conducted a negative control test to confirm that the models were not simply fitting noise or overfitting to corpus regularities. In this test, tokonoma, a clearly physical architectural feature, was intentionally reclassified as conceptual, introducing a controlled contradiction in the gold labels. The objective was to evaluate whether the models’ internal representations would respond appropriately to this falsified hypothesis. Across the full corpus, the BERT configurations consistently declined in performance compared to the valid hypothesis. The base and k-means variants dropped from 0.852 to 0.719, while the Agglomerative variant decreased to 0.304. The same trend was visible on the CLEAN corpus, where scores fell from 0.718 to 0.597 across BERT variants

In contrast, static models, such as Word2Vec, showed no coherent reaction to the relabelling. CBOW maintained a low ARI of 0.100, while Skip-gram fluctuated modestly but remained far below the contextual model’s sensitivity range. These results confirm that only the contextual embeddings respond predictably to conceptual mislabelling, while static embeddings lack such semantic discrimination.

The controlled drop across BERT variants demonstrates that their strong performance in earlier tasks was not a statistical artefact but reflected a learned semantic organisation aligned with the valid physical–conceptual distinction (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Negative control: relabelling tokonoma as conceptual. ARI decreases for BERT on both FULL and CLEAN relative to the valid hypothesis, demonstrating sensitivity to theoretical inconsistency; static models show no coherent response.

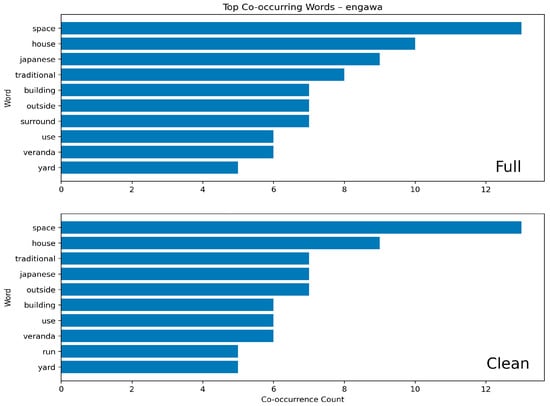

3.6. Baseline Context: Co-Occurrence Analysis

Due to the large amount of data, this section presents a sample of the results of this analysis. The full dataset is available in the online repository. All reporting is from the seed 777 pipeline and the 10-token window. Across targets, CLEAN retains the same high-frequency neighbours as FULL but with altered weights once definitional strings are removed. For ma, the top neighbours on FULL are “space” (26), “ishi” (12), “experience” (12), “ai” (11), “mean” (10), “concept” (10), “japanese” (9), “room” (8), “moment” (8), and “dance” (8). On CLEAN, “space” rises to 29, “japanese” and “concept” both register 15, followed by “ishi” (12), “ai” (12), and “experience” (12), with the tail comprising “literally” (11), “room” (10), “mean” (9), and “design” (8).

For wabi, FULL shows “aesthetic” (44), “japanese” (35), “beauty” (20), “design” (18), “tea” (16), and “style” (15), then “world” (12), “art” (12), “ideal” (11), and “sense” (11). CLEAN increases the lead terms “aesthetic” (46) and “japanese” (36), then “design” (20), “beauty” (18), “tea” (17), and “style” (15), with the same four items at 12–11 counts in the tail. Sabi shows the same pairwise pattern: FULL lists “aesthetic” (44), “japanese” (35), “beauty” (20), and “design” (18), then “style/world/ideal” (10–11). CLEAN retains those items but admits “imperfection” (12) and “object” (10) into the top ten.

Physical terms remain materially anchored. sandō on FULL surfaces “rear” (11), “entrance” (11), “omote” (9), “main” (9), “approach” (8), “shrine” (8), “ura” (8), “road” (5), and “komainu” (5); CLEAN reproduces the same set with near-identical counts. Engawa keeps “space” (13) and “house” (9) at the top on FULL, followed by “outside/japanese/traditional” (7) and “veranda” (6); CLEAN shifts weight toward use and setting with “use”, “building” and “yard” appearing in the top ten at 5–6 counts. For byōbu, FULL lists “panel” (8), “screen” (6), “painting” (5), “produce” (5), and “period” (5); CLEAN keeps these and changes only lower-rank items by one or two counts.

Physical terms remain materially anchored. sandō on FULL surfaces “rear” (11), “entrance” (11), “omote” (9), “main” (9), “approach” (8), “shrine” (8), “ura” (8), “road” (5), and “komainu” (5); CLEAN reproduces the same set with near-identical counts. Engawa keeps “space” (13) and “house” (9) at the top on FULL, followed by “outside/japanese/traditional” (7) and “veranda” (6); CLEAN shifts weight toward use and setting with “use”, “building”, and “yard” appearing in the top ten at 5–6 counts. For byōbu, FULL lists “panel” (8), “screen” (6), “painting” (5), “produce” (5), and “period” (5); CLEAN keeps these and changes only lower-rank items by one or two counts.

Tokonoma remains consistent across corpora, with the top items being “room” (14), “alcove” (13), “display” (7), “recess” (7), and “tea” (7). CLEAN retains that order and adds construction and furnishing terms among the lower ranks (“build”, “tatami”, and “scroll”, each 4–5). shōji is strongly material in both corpora: FULL shows “paper” (43), “slide” (40), “use” (33), “door” (29), “glass” (22), and “screen/panel” (18/18), with CLEAN preserving the same sequence and small count adjustments. roji is sparse but stable; the CLEAN file records “yard” (4), “tea” (3), “development” (3), “house” (2), and a small set of alternants at 2, while FULL presents the same items with the same or adjacent counts.

The CLEAN outputs preserve each target’s nearest lexical neighbourhood while modestly reweighting items typical of definitional prose. Figure 12 below visualises the FULL and CLEAN distribution bar plots. The rest of the per-seed plots, together with extended visualisations and summary statistics, are available in the public repository referenced in the Data Availability Statement.

Figure 12.

Comparison of top 10 lexical neighbours for representative terms in FULL versus CLEAN. Conceptual items (e.g., ma, wabi, sabi) show stable neighbourhoods with reweighted counts after removing definitional sentences; physical items (e.g., sandō, engawa, byōbu) remain materially anchored.

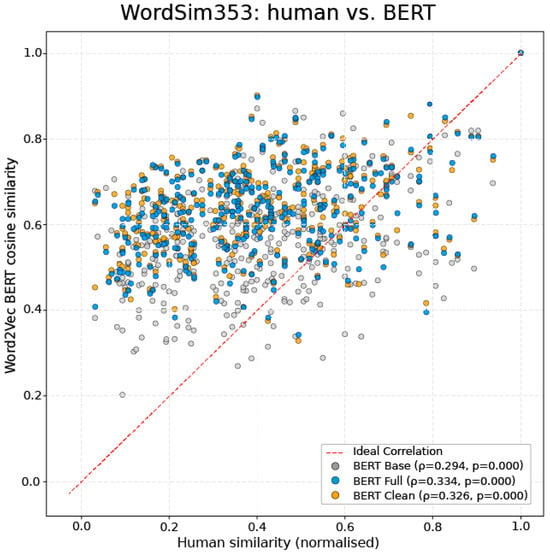

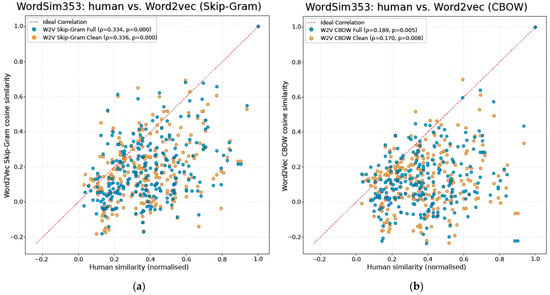

3.7. External Validation on WordSim353

The WordSim353 benchmark evaluated each model to test whether the observed structural behaviour extended to general semantic understanding. This dataset comprises 353 English word pairs, each rated by human participants for semantic similarity. For every model, we compared cosine similarities between the embeddings of each word pair with the human scores using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ).

Across all runs, contextual models aligned better with human judgements than static ones. BERT (base) achieved ρ = 0.294 (p < 0.001), while BERT (fine-tuned) improved to ρ = 0.326 on the CLEAN corpus and ρ = 0.343 on the FULL corpus. These gains confirm that fine-tuning contributed to slightly stronger human-model agreement (Figure 13). It also suggests the possibility of training these models for improved alignment.

Figure 13.

WordSim-353 external validation for BERT. Spearman correlations for base versus fine-tuned BERT, with fine-tuning improving results to ρ ≈ 0.326 on CLEAN and ρ ≈ 0.343 on FULL.

Among the static models, Word2Vec Skip-gram reached the highest correlation (ρ ≈ 0.336 FULL, ρ ≈ 0.334 CLEAN), meanwhile Word2Vec CBOW produced weaker results (ρ ≈ 0.170 FULL, ρ ≈ 0.189 CLEAN). This ordering mirrors the earlier clustering outcomes. In other words, Skip-gram outperforms CBOW but remains generally inferior to contextual embeddings in semantic discrimination (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

WordSim-353 human similarity (normalised) versus Word2Vec Skip-Gram cosine similarity for the FULL and CLEAN corpora. Each point is a word pair and the dashed diagonal line marks ideal agreement: (a) Skip-Gram; (b) CBOW.

On WordSim-353, BERT (base) achieves ρ = 0.294 (p < 0.001); BERT (fine-tuned) reaches ρ = 0.326 on CLEAN and ρ = 0.343 on FULL. Skip-gram is comparable at ρ ≈ 0.334 on CLEAN and ρ ≈ 0.336 on FULL, while CBOW is weaker at ρ ≈ 0.170 on CLEAN and ρ ≈ 0.189 on FULL. These results indicate moderate agreement for contextual models and only weak agreement for CBOW on this benchmark. On the primary clustering endpoint, BERT remains more accurate and seed-invariant, while CBOW is invariant but low, and Skip-gram is seed-sensitive.

4. Discussion

This study set out to evaluate the efficacy and reproducibility of a computational framework designed to analyse architectural semantics, using Japanese architectural concepts as a test case. By comparing contextual language models (BERT) against static baselines (Word2Vec) under different corpus conditions (FULL vs. CLEAN), the research assessed how well these models could recover a known theoretical distinction between conceptual and physical terms. Ultimately, the findings validate the framework’s utility for humanistic inquiry, underscore the necessity of contextual models for nuanced semantic tasks, and, perhaps most critically, highlight the critical impact of data preprocessing through a ‘definitional audit’.

4.1. Contextual Embeddings Surpass Static Models in Capturing Architectural Semantics

The results make it clear that contextual embeddings are superior for this specific task, supporting Hypothesis 1. Pipeline diagnostics confirmed that both corpora exhibited natural language properties, including Zipf-like distributions (α ≈ 1.36, R2 ≈ 0.97), and that all models achieved stable convergence during training. These diagnoses ensure that any performance differences seen later on truly originated from model architecture and data, rather than mere training artefacts. Across six fixed random seeds, the fine-tuned BERT model produced statistically significant Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) scores of 0.8521 on FULL (95% CI [0.5723, 1.0000]; permutation p ≈ 6.53 × 10−14) and 0.7182 on CLEAN (95% CI [0.3701, 1.0000]; permutation p ≈ 6.98 × 10−6). Using ARI, a chance-corrected metric, provides a robust measure of clustering quality; scores well above zero indicate genuine alignment with the theoretical classes, not incidental overlap. Crucially, there was zero variation across seeds (BERT ΔARI = 0), confirming the reproducibility of BERT’s advantage.

We ran paired sign tests across six seeds, treating each seed as a paired replicate; BERT > CBOW and BERT > Skip-gram were positive for every seed on both corpora (exact sign test p = 0.031; Cliff’s δ = 1.00). We report these as post hoc tests that confirm the descriptive results. Using the six seeds as paired replicates and restricting all models to the same clustering setup (KMeans + L2), BERT’s ARIs exceeded CBOW and Skip-gram in six of six seedwise comparisons on both corpora, as read directly from the per-seed ARI tables in the CAL.xlsx master sheet, which aggregates the complete ARI scores from all six seed runs, as the main pipeline log did not compute these cross-seed comparisons. The “BERT–Skip-gram = 0.95 on FULL” figure is the mean of the six seedwise differences. These statistics were computed explicitly from the six seedwise differences and should be presented plainly as post hoc confirmatory checks, not as ‘derived equivalents’. This pattern aligns with the view that contextual models better capture polysemy in specialised discourse. Models shared the exact source text and evaluation labels (Word2Vec pipeline: 52,661 sentences, 623,058 tokens, BERT consumed the same sentence corpus), so the observed gaps are unlikely to reflect corpus or labelling artefacts. The BERT versus Word2Vec ranking is unchanged from FULL to CLEAN and persists under the negative control.

In stark contrast, the static Word2Vec models proved utterly inadequate. CBOW, for instance, achieved near-chance levels with non-significant results on both corpora: ARI = 0.133 on FULL (95% CI [0.0000, 0.5088]; permutation p-value: 0.2598) and CLEAN (95% CI [0.0000, 0.5088], p-value: 0.2598). Skip-gram performed worse still, yielding negative ARIs on average (−0.100 on FULL, −0.108 on CLEAN; 95% CI on FULL [−0.1254, 0.0321]; permutation p-value: 0.2796), suggesting that its clustering was functionally random with occasional inversions relative to the gold standard. These models assign a single, fixed vector to each word, a severe limitation on their ability to distinguish context-dependent meanings. While specific configurations involving normalisation and alternative clustering algorithms slightly improved Skip-gram’s performance on the CLEAN corpus (ARI ≈ 0.4761), these gains were wildly inconsistent and never truly challenged BERT’s apparent superiority. Our findings highlight the task-dependent limitations of static embeddings, a finding that diverges from the approach seen in Hengchen et al. (2021) [36]. While Hengchen et al. successfully employed static Word2Vec models to explore broad diachronic shifts in vocabulary associated with the concept of ‘nation’ across large, general historical newspaper corpora, evaluating plausibility through historical interpretation, our study demanded fine-grained synchronic classification within a specialised architectural domain, evaluated quantitatively against a theoretical gold standard. In our context, which demanded high semantic precision, static models (CBOW and Skip-gram) decisively failed, performing near or below chance. This failure strongly suggests that while static embeddings may be pragmatically sufficient for identifying large-scale associative trends in general historical texts, they lack the necessary sensitivity to accurately replicate nuanced, theoretically defined conceptual distinctions within specialised discourse. Put simply, the failure of CBOW and Skip-gram here reinforces the absolute need for context-sensitive models like BERT when the analytical task demands precise semantic differentiation.

However, digging into the granular, seed-level analysis reveals a crucial finding regarding both algorithmic and seed-level stability, further reinforcing BERT’s suitability. While BERT, on the one hand, exhibited remarkable consistency across all six random seeds (primary ARI: 0.7182, negative control: 0.5973 on CLEAN), this stability was also reflected in the clustering algorithms after cleaning. For instance, the log’s ‘Definitional Bias Check’ highlights this; an alternative BERT [Agglo + L2] variant scored a low 0.3945 on the FULL corpus, but after cleaning, its score rose by 82.07% to 0.7182 on the CLEAN corpus, matching the primary model. This confirms that removing definitional sentences was critical for algorithmic robustness. This overall stability contrasts sharply with the static models; the normalised static Skip-gram variants, on the other hand, despite their poor average, produced two baffling, high-scoring seed-level outliers. Specifically, with Skip-gram [Agglo + L2] (seed 387), an exceptional ARI of 0.8477 was achieved on the primary task and 0.7099 on the negative control, outperforming BERT. With Skip-gram [KMeans + L2] (seed 1234), an ARI of 0.7106 (primary) and 0.5855 (negative control) was achieved, closely matching BERT’s performance. This wild, erratic behaviour highlights Skip-gram’s fundamental lack of stability; these spikes are not reproducible across seeds or variants and do not overturn the paired comparison with BERT. These “successes” are best understood as stochastic artefacts tied to initialisation and clustering choice, rather than the result of reliable semantic modelling. These results from different seeds powerfully underscore the methodological importance of multi-seed evaluations emphasised in Section 2.5. It is easy to imagine how a researcher encountering only a high-performing seed might erroneously conclude that static models are viable. Our multi-seed protocol correctly identifies these as unrepresentative outliers, affirming that consistent, reproducible performance, not just occasional peaks, is the critical metric for a scientifically sound validation framework. Nevertheless, we do not dismiss the need for further investigation into these spikes. However, BERT’s rock-solid stability solidifies its position as the more trustworthy tool for this analysis.

4.2. The Definitional Audit: Mitigating Shortcut Learning and Revealing Latent Structure

One of our central methodological investigations involved the ‘definitional audit’, comparing models trained on the FULL corpus versus the CLEAN corpus (with dictionary-like sentences removed). This comparison revealed that while enhancing performance metrics, explicit definitions, although seeming to help, can actually lead to brittle models that rely on superficial cues, a phenomenon aptly known as ‘shortcut learning’. Removing definitions caused a modest drop in BERT’s ARI (from 0.8521 to 0.718), but the fundamental conceptual–physical distinction persisted, satisfying Hypothesis 3 (H3) (ΔARI ≤ 0.20). This drop in ARI score is a clear indicator that BERT was learning latent semantic relationships from contextual usage, not just explicit definitions.

On the FULL corpus, Agglomerative clustering underperforms (ARI 0.394), while k-means achieves a high ARI (0.852). On the CLEAN corpus, both methods converge at a value of 0.718. This pattern suggests linkage-based fragility under the FULL distribution, likely due to densification from definitional sentences that benefits centroid-based k-means but hampers hierarchical linkage, rather than to a wholesale distortion of the BERT embedding space. This behaviour aligns with concerns that Rogers et al. (2021) noted regarding BERT’s reliance on such patterns and potential brittleness [37]. However, upon removing these definitional anchors, the model’s performance on the CLEAN corpus, while slightly lower (ARI 0.718), became robust across both k-means and Agglomerative clustering. This crucial stability indicates that BERT successfully learned the latent conceptual distinction from the remaining contextual patterns in the CLEAN discourse. While confirming a reliance on surface patterns (as performance dropped when removing definitions), the results demonstrate that BERT’s powerful pattern-learning capabilities can, in fact, capture genuine, stable semantic structures when strong, misleading cues are absent, reinforcing the CLEAN corpus as a more trustworthy baseline. Although cleaning also slightly improved the normalised Skip-gram variant (ARI ≈ 0.476), confirming noise reduction benefits static models, it did not come close to overcoming their fundamental inadequacy for this task.

4.3. Framework Validation: Sensitivity, Reproducibility, and External Benchmarking

We then further validated the framework’s ability to serve as a tool for humanistic inquiry through sensitivity testing and external benchmarking. The negative control test, which intentionally mislabelled ‘tokonoma’ as ‘conceptual’, demonstrated BERT’s semantic sensitivity. ARI predictably declined (e.g., from 0.718 to 0.597 on CLEAN) when ‘tokonoma’ was misclassified as conceptual, which is theoretically positive and indicates that the model recognised the inconsistency. Static models, predictably, exhibited no coherent response, confirming their inability to discriminate semantics. This very capacity to computationally probe and react to theoretical manipulations is crucial for utilising embeddings in fields such as digital conceptual history [38]. Furthermore, the study’s adherence to reporting ARI, a chance-corrected metric recommended by Hubert and Arabie (1985), alongside confidence intervals and permutation tests, strengthens the statistical validity and reproducibility of the findings [32].

External validation on WordSim-353 placed the model’s performance in a broader semantic context. Fine-tuned BERT is moderately correlated with human judgments (ρ (rho) ≈ 0.343 on FULL), suggesting that its learned space generalises to some extent beyond the architectural domain. However, interpreting this result requires a healthy dose of caution. As Hill et al. (2015) [39] argue, WordSim-353 conflates actual similarity with mere association. Skip-gram’s surprisingly competitive performance on this benchmark (ρ ≈ 0.336), despite its poor performance on the primary clustering task, almost certainly reflects WordSim-353′s tendency to reward co-occurrence-based associations, which static models capture relatively well [39]. The results of WordSim do not contradict the main in-domain finding; contextual models are more effective at handling conceptual distinctions. Because WordSim-353 mixes association with similarity, it is only a partial probe of the semantic competence we evaluate. Future work may prefer similarity-focused datasets, for example, SimLex-999.

Finally, the co-occurrence analysis provided qualitative support, showing that cleaning definitions reweighted local lexical neighbourhoods but preserved the core semantic associations for conceptual (ma, wabi) and physical (sandō, engawa) terms. The analysis provided clear and distinct contexts for the key aesthetic principles. For instance, the term “Ma” (間), for example, showed a strong co-occurrence with words like “space (29 times)”, “concept (10)”, and “experience (12)”, confirming its role as a fundamental Japanese concept of spatiality, often discussed in both physical and experiential terms.

Likewise, the concept of wabi (侘) was strongly associated with “aesthetic (46 times)”, “Japanese (37)”, “beauty (20)”, and “design (20)”. Sabi (寂) displays similar results—“aesthetic (45)”, “Japanese (36)”, “design (20)”, and “beauty (18)”—in the CLEAN corpus. However, the analysis also highlighted their distinct nuances. Wabi co-occurred with “tea (17)” and “sense (11)”, linking it to the rustic simplicity of the Japanese tea ceremony. At the same time, sabi was uniquely associated with “imperfection (12)” and “object (10)”, pointing to the beauty found in age and the passage of time.

In sharp contrast, the top co-occurring words for physical terms relate to concrete objects and spatial arrangements. The term sandō (a formal path) most frequently appears with “rear (11 times)”, “entrance (11)”, “omote (main facade, 9)”, and “main (9)”. These distinct lexical associations are consistently observed across the terms in each category.

Furthermore, the analysis clarified the meanings of more concrete architectural terms. The term engawa (縁側), for its part, was linked to “space (13)” and “house (9)”, identifying it as a transitional space. At the same time, byōbu (屏風) was associated with “panel (8)” and “screen (6)”, defining its function as a room divider. These results reinforce the idea that the CLEAN corpus retains the essential contextual information necessary for semantic differentiation, consistent with theories of context-driven search emphasising meaning derived from usage patterns. This baseline analysis provides a data-grounded foundation for more in-depth explorations in future studies.

4.4. Validating the Framework: Reproducibility, Sensitivity, and External Coherence

From the beginning, the framework’s design emphasised reproducibility and validation. Across seeds, BERT and CBOW show zero variance in ARI; Skip-gram varies slightly (SD ≈ 0.023 on FULL, ≈0.004 on CLEAN). This is described as zero for BERT/CBOW and small but non-zero for Skip-gram, not as a uniform ‘±0.02’.

The negative control test (reclassifying tokonoma as conceptual) further validated the framework’s utility for probing theoretical claims. BERT responded sensitively and predictably to this controlled contradiction, with ARI scores decreasing but remaining significantly above chance. Static models, in stark contrast, showed no coherent reaction whatsoever. This differential response is a powerful confirmation that BERT’s strong performance truly reflects a learned semantic organisation aligned with the valid conceptual distinction, rather than just some statistical artefact. This ability to computationally test and potentially falsify hypotheses aligns perfectly with the goals in digital conceptual history (Begriffsgeschichte) and cultural analytics, where embeddings are used to trace and compare conceptual structures.

External validation on WordSim-353 is only weakly consistent with H2: correlations are modest (BERT ρ ≈ 0.34 on FULL and ≈0.33 on CLEAN; Skip-gram ≈ 0.34 on both), and because WordSim-353 conflates similarity with association, this should be treated as a limited external check rather than a decisive test of conceptual understanding. As before, however, this result must be interpreted cautiously. WordSim-353, after all, has been widely criticised for conflating genuine similarity (like car/automobile) with mere association or relatedness. SimLex-999 was explicitly designed to address this, focusing solely on similarity. Given this distinction, BERT’s moderate correlation with WordSim-353 might reflect the benchmark’s mixed nature rather than a limitation of BERT itself. Indeed, studies using SimLex-999 show that models often struggle precisely with highly associated but dissimilar pairs. The fact that Skip-gram’s strong performance on WordSim-353 (ρ ≈ 0.336) compared to its failure on the domain-specific clustering task only further highlights that success on general benchmarks guarantees nothing about suitability for specialised theoretical inquiries. The co-occurrence analysis confirmed that the core lexical neighbourhoods remained stable after cleaning, providing a qualitative baseline and indicating that the CLEAN model operates on relevant contextual information.

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

While this study establishes a robust methodology, several limitations should be noted. The 1.98 million-word corpus, although carefully curated, is relatively small compared to corpora typically used for pre-training, which may limit the richness of the learned embeddings. The study also did not explore other forms of robustness, such as sensitivity to paraphrasing or minor variations in the prompt. Finally, although extensive measures were taken to ensure reproducibility within the same hardware-software stack, achieving truly byte-identical results across different machines remains a notorious challenge.

Future work will apply this validated CLEAN model framework to its intended purpose. The next immediate step is to use the framework on larger, multilingual architectural corpora, moving beyond the validation of known concepts. The goal is to discover novel, emergent semantic structures and conceptual shifts within architectural discourse over time, thereby contributing to a computationally informed Begriffsgeschichte for architecture.

5. Conclusions

This study designed, implemented, and rigorously validated a reproducible computational framework for analysing architectural semantics using Japanese architectural concepts. The research yielded several findings tied to the revised research questions and hypotheses, comparing contextual and static language models under controlled corpus conditions.

Regarding model differences (RQ1), the results demonstrated a stark contrast; fine-tuned BERT consistently and accurately captured the theoretical distinction between conceptual and physical terms. In contrast, static Word2Vec models (CBOW and Skip-gram) failed to produce meaningful or stable classifications.

Regarding task alignment (RQ2), performance on the general similarity benchmark (WordSim-353) did not reliably predict success on the theory-driven clustering objective (ARI). Fine-tuned BERT achieved a strong ARI against the gold standard (mean ARI ≈ 0.718 on the audited CLEAN corpus) but only a modest WordSim-353 correlation (ρ ≈ 0.343), while Skip-gram reached a similar WordSim-353 value (ρ ≈ 0.336) yet failed the primary ARI task. General lexical similarity appears to be a weak proxy for the domain objective in this setting.

The framework proved effective in testing a pre-existing theoretical claim (RQ3). BERT responded sensitively and predictably to a controlled mislabelling (conceptual as tokonoma), with performance decreasing but remaining statistically significant. At the same time, static models showed no coherent reaction, confirming the framework’s ability to probe theoretical validity.

Regarding data hygiene (RQ4), explicit definitional sentences distorted metrics and increased instability. On the full corpus, they inflated centroid-based scores (BERT k-means ≈ 0.852) but deflated hierarchical ones (Agglomerative + L2 ≈ 0.394). After removal, all BERT clustering variants converged near ≈ 0.718 on the CLEAN corpus, indicating that the dispersion across algorithms was an artefact of definitional leakage rather than model semantics.

These findings strongly support the study’s hypotheses:

- H1 was supported: BERT’s contextual logic aligned significantly better with the phenomenological classification than static Word2Vec models.

- H2 mixed: Fine-tuned BERT led on the primary ARI objective, but WordSim-353 correlations were modest and not consistently higher than Word2Vec, indicating weak alignment between the benchmark and the domain task.

- H3 qualified: After removing definitional sentences, BERT k-means and k-means + L2 dropped slightly (≈0.852 → ≈0.718), while Agglomerative + L2 rose sharply (≈0.394 → ≈0.718). Stability holds in the sense of post-clean convergence across algorithms, not in per-algorithm deltas.

This paper presents a transparent, reproducible, and validated methodology showing how carefully audited contextual embeddings can model nuanced semantic distinctions in specialised discourse. It provides a groundwork for integrating computational methods into architectural theory and history, and offers tools that augment, rather than replace, humanistic interpretation by enabling the quantitative analysis of conceptual structure in texts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, G.G. and S.Y.; methodology, G.G.; software, G.G.; validation, G.G. and S.Y.; formal analysis, G.G.; investigation, G.G.; resources, G.G.; data curation, G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.; writing—review and editing, G.G.; visualisation, G.G.; supervision, S.Y.; project administration, G.G.; funding acquisition, S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP23K04201 (“Co-Creation Between Deep Learning-Based Generative AI and Humans”) and the Institute of Disaster Mitigation for Urban Cultural Heritage, Ritsumeikan University. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Data Availability Statement

All materials necessary for replication, including the corpora (FULL and CLEAN), model configurations, YAML files, and complete results from multi-seed runs, are publicly available in the project’s repository, linked here https://github.com/ArchiScrub/Reproducibility-and-Validation-of-a-Computational-Framework-for-Architectural-Semantics “URL (accessed on 23 October 2025)”. The repository also includes scripts, logs, and documentation supporting the analyses and figures presented in this paper. Three machine-snapshot JSONs (S1–S3) documenting cross-environment runs are deposited with the paper and support independent verification of the claims above.

Acknowledgments

The computational analysis in this study was facilitated by the use of generative AI. Tools such as Google’s Gemini Pro, OpenAI’s GPT-4, and Grok were used in developing the Python pipeline and also served as an essential resource for understanding the underlying code. The authors reviewed and edited all outputs and take full responsibility for the published content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Adj | Adjective |

| adv | Adverb |

| Agglo | Agglomerative clustering |

| Ag + L2 | Agglomerative clustering with L2 regularisation |

| α (alpha) | Exponent parameter in Zipf’s law |

| ARI | Adjusted Rand Index |

| BERT | Bidirectional encoder representations from transformers |

| BLAS | Basic linear algebra subprograms. |

| CBOW | Continuous bag of words |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CLEAN | Filtered corpus version with definitional or glossary-like sentences removed |

| CPU | Central processing unit |

| CUDA | Compute unified device architecture |

| cv | Cross-validation folds |

| Δ (delta) | Difference or change between values (e.g., ΔARI) |

| FULL | Unfiltered corpus version including definitional sentences |

| GPU | Graphics processing unit (appears in methods and hardware setup) |

| H | Hypothesis |

| hs | Hierarchical softmax (Word2Vec training parameter) |

| K | Number of clusters (in k-means) |

| KM + L2 | K-means with L2 regularisation |

| LLM | Large language model |

| log-log | Logarithmic–logarithmic (used in Zipf distribution plotting) |

| max_iter | Maximum number of iterations (algorithm parameter) |

| min_count | Minimum frequency threshold for word inclusion |

| negative | Number of negative samples (Word2Vec parameter) |

| NLP | Natural language processing |

| p_perm | Permutation test probability |

| p-value | Probability value |

| propn | Proper noun (part-of-speech tag) |

| ρ (rho) | Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient |

| R2 | Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (coefficient of determination) |

| RQ | Research question |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SG | Skip-gram |

| SHA-256 | Secure hash algorithm 256-bit (used for artefact hashing) |

| TF32 | TensorFloat-32 (reduced-precision floating-point format used in NVIDIA GPUs) |

| W2V | Word2Vec |

| Word2Vec | Full name Word2Vec (stands for word to vector) |

| WordSim | WordSim-353 (semantic similarity benchmark dataset) |

| YAML | It is a human-readable data serialisation language. |

| Zipf | Zipf’s law (used when describing corpus distributions) Exponent parameter in Zipf’s law |

Appendix A

Appendix A provides a complete glossary of the 28 target terms examined in this study. Each entry offers a concise dictionary definition to support conceptual clarity and precision. No standard dictionary definitions were available for ‘ikezuishi’ and ‘tomeishi’.

- Aware (哀れ): (n) pity; sorrow; grief; misery; compassion; pathos; (adj-na) pitiable; pitiful; pathetic; miserable [40].

- Byōbu (屏風): Folding screen [40].

- Chashitsu (茶室): Tea arbour; tea arbour; tearoom [40].

- Chigaidana (違い棚): Set of staggered shelves [40].