Abstract

This study presents a monitoring-calibrated, systems-level retrofit assessment for a 15-year-old Grade-A office building in Beijing, China (temperate monsoon climate). One year of continuous monitoring (2023–2024) was combined with calibrated multi-physics simulations (EnergyPlus/DesignBuilder, Radiance, representative CFD) to evaluate retrofit scenarios for lighting, envelope and HVAC systems. Baseline EUI = 108 kWh·m−2·yr−1 (total site electricity ≈ 3,088,893 kWh·yr−1). HVAC accounted for ≈48% of site electricity. Key findings: (1) LED lighting retrofit delivered measured lighting savings of ~26.7% (simulated potential up to ~32.7%) but may increase cooling loads in some operating regimes (simulated +8.3%) if not coordinated with HVAC and envelope measures; (2) glazing upgrades and airtightness improvements materially increase HVAC savings; (3) a prioritized, phased retrofit (lighting → envelope → HVAC) can capture ~80–85% of integrated carbon reductions while lowering immediate CAPEX and business disruption; (4) scheduling major HVAC upgrades before the cooling season and envelope works during transitional months improves operational and economic outcomes. Calibration and uncertainty metrics are reported (annual energy error < 5%).

1. Introduction

China has undergone rapid urbanization, and by the end of 2020, the country’s building stock reached approximately 68.8 billion square meters [1]. The energy consumption in the construction sector has steadily increased, contributing to energy shortages and environmental challenges. Globally, buildings contribute 39% of carbon emissions (UNEP 2023). In China, there are 680 million m2 of aged office stock (MOHURD 2023), representing significant untapped retrofit potential. The development of building energy efficiency in China remains relatively recent, particularly regarding low-carbon architecture, which previously received insufficient attention. Consequently, existing buildings exhibit characteristics of high energy consumption and significant pollution [2,3]. In addition, these buildings often suffer from poor indoor thermal comfort, insufficient natural light, and inadequate ventilation, directly affecting the health and work efficiency of the occupants [4,5].

Traditional renovation studies have mostly focused on the application of single energy-saving technologies [6,7], often neglecting aspects such as cross-system antagonisms (e.g., LED efficiency vs. heating penalties) and occupant-centric performance gaps, where observed savings (33%) fall short of simulated predictions (41%). However, cutting-edge international research and green building rating systems (such as LEED, BREEAM, and the China Green Building Evaluation Standard) emphasize a comprehensive assessment of building performance, including energy consumption, carbon emissions, indoor environmental quality (IEQ), and site ecology [8,9]. A successful green renovation plan must find the optimal balance between energy saving, carbon reduction, and enhancing indoor environmental quality [10]. Although many studies have assessed specific retrofit measures (lighting, HVAC, or envelope), few combine year-long field monitoring with calibrated multi-physics simulations to derive an operationally feasible, phased retrofit schedule that explicitly avoids major business disruption. Recent international studies provide evidence about measure-level effectiveness but do not focus on sequencing or on implementation timing under normal office operations [11,12,13,14,15]. This study fills that gap by: (1) presenting a monitoring-calibrated simulation workflow, (2) quantifying cross-system interactions (lighting ↔ HVAC ↔ envelope), and (3) developing and validating a phased retrofit scheduling strategy that minimizes office disruption while maximizing energy and carbon reductions. Therefore, using integrated simulation analysis methods to pre-assess the physical environment of the building concerning wind, light, heat, and sound has become a core technical means for guiding green low-carbon renovations [16,17,18,19].

This article takes a certain Grade A office building as an example, aiming to elaborate on the analysis results of building energy consumption monitoring through integrated building performance simulation methods. It seeks to comprehensively evaluate its indoor and outdoor environmental performance and propose a comprehensive green renovation plan. It addresses the specific operational issues faced by property owners and facility managers: whether high-resolution monitoring combined with calibrated multiphysics simulations can reliably quantify cross-system interactions (lighting ↔ HVAC ↔ facade), and generate a phased retrofit prioritization plan that captures most deep retrofit savings, minimizes tenant disruption, and remains robust under variations in occupancy monitoring and weather conditions.

2. Research Overview

2.1. Project Overview

This study examines a 5A-rated office building located in Beijing at 39.80° N, 116.47° E. The 15-year-old building has a total floor area of 44,000 m2, with 29,000 m2 dedicated to air-conditioned space, and consists of 21 above-ground floors and 3 underground levels. The building peak cooling design load is 3550 kW and the peak heating design load is 3000 kW (design basis). The installed mechanical system is composed of multiple chillers and terminal units: for example, individual AHU/terminal units typically provide ~81 kW cooling capacity and ~68 kW heating capacity per unit (rated). Originally completed with state-level awards for its fully equipped facilities, the building has experienced energy consumption spikes and uneven indoor temperature distribution in recent years, largely due to aging equipment.

The term “5A-grade” used in this manuscript refers to a local city-level Grade-A commercial office classification commonly used in municipal leasing markets; for an international audience, this corresponds to high-quality Grade-A office buildings with modern services, central HVAC systems, high architectural and MEP standards, and high occupant amenity. We use “Grade-A” and “5A-grade” interchangeably in the text for clarity.

The building’s orientation is primarily north–south, and it has a window-to-wall ratio of approximately 0.45 (as shown in Figure 1). Current indoor environmental quality indicators, such as daylight factors, natural ventilation potential, and equipment noise levels, fail to meet modern high-standard office requirements due to the building’s age. These factors are critical not only to occupant comfort and health but are also coupled with the building’s energy consumption—a core issue addressed in this renovation.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the model of an existing Grade 5A office building (A Grade 5A office building refers to a high-standard office building with advanced facilities, energy efficiency, and intelligent management systems, according to Chinese commercial real estate classification). (a) Human-eye view of a Grade 5A office building; (b) Standard Floor Plan (A standard floor refers to a repetitively designed floor unit within a building, characterized by uniform layout, area, height, and functional zoning for efficient design, construction, and management).

The methodology, expanded in this study, includes a detailed defect analysis, revealing critical deficiencies: thermal comfort compliance at 33.35% compared to the required 60% as per GB/T 50785 Class II (as shown in Table 1), window airtightness at Class 6 relative to the required Class 8 per GB/T 31433, and a daylight autonomy of 59% in operable zones (as shown in Table 2).

Table 1.

Proportion of indoor comfortable temperature standards met.

Table 2.

Indoor Lighting Analysis Report.

To address these interconnected issues, a novel Monitoring-calibrated, systems-level retrofit assessment Framework (monitoring-calibrated, systems-level retrofit assessment) was employed, featuring a coupled simulation workflow validated against monitored data with an energy model error of less than 5%. This approach aims to holistically evaluate and enhance both the indoor and outdoor environmental performance, enabling a comprehensive green renovation strategy that aligns with international standards.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Monitoring

A one-year monitoring campaign (2023–2024) captured whole-building electric metering (15 min resolution where available), chilled-water flow and supply/return temperatures, terminal air temperatures, sub-circuit lighting energy, and spot IAQ and noise surveys. Instrumentation included ultrasound flowmeters, clamp power meters, three-phase whole-building meters, and temperature/humidity sensors.

2.2.2. Data Processing and QA/QC

Raw data were time-synchronized and gap-filled with conservative linear interpolation. Outliers were detected via ±3σ rules and corrected or removed after cross-checking with BMS logs and field notes. When discrepancies occurred between BMS and field instruments, priority was given to calibrated field instruments after on-site cross-calibration. Aggregation to hourly/daily/monthly series followed consistent time zones and daylight savings conventions.

2.2.3. Simulation and Calibration

Whole-building energy models were developed in EnergyPlus via DesignBuilder (geometry, constructions, schedules, internal gains and HVAC templates derived from drawings and on-site verification). Daylighting for representative perimeter zones was modeled with Radiance; representative CFD cases were used to evaluate ventilation patterns for deep plan zones. Model calibration followed ASHRAE Guideline 14 principles: annual energy error (%), NMBE and CV(RMSE) were computed for total energy and for sub-systems where data allowed (chiller energy, lighting sub-circuits). The final calibrated model achieved an annual energy error <5% against monitored annual energy. Sensitivity analysis varied occupant schedules, internal gains, lighting power densities and infiltration ±20% to establish uncertainty bounds [20].

2.2.4. Scenario Design

We evaluated four principal retrofit scenarios: (i) lighting-only (LED replacement + dimming/occupancy controls), (ii) envelope-only (upgraded glazing and enhanced airtightness), (iii) HVAC-only (high-COP chillers, pump VFDs, BAS tuning), and (iv) integrated phased sequences (e.g., lighting → envelope → HVAC and alternative orders). Economic assessments used vendor CAPEX quotations, simple payback and sensitivity to carbon pricing assumptions.

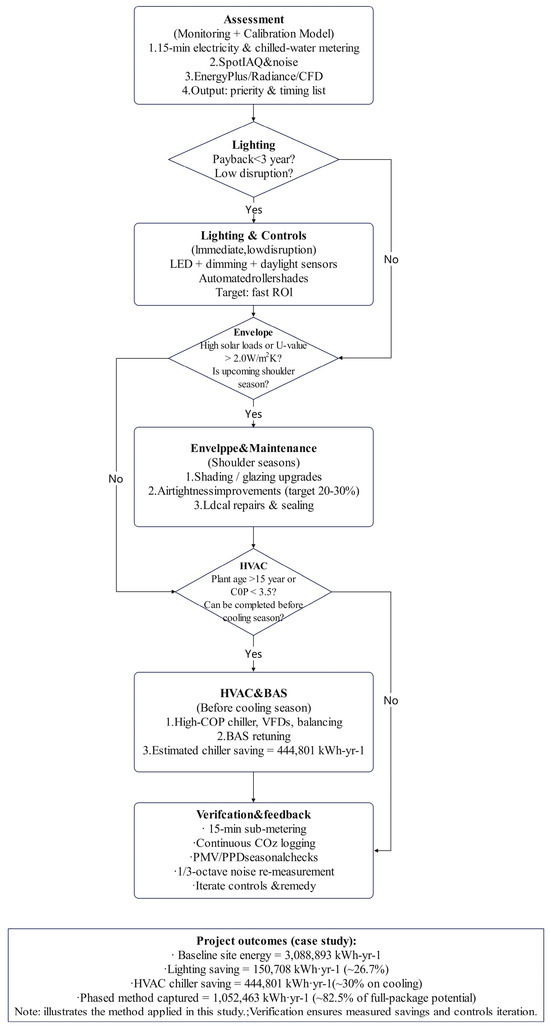

The assumptions adopted in our model inputs and scenario definitions serve three interrelated purposes: (a) model validation, where conservative, measurement-anchored inputs (measured schedules, monitored internal gains and instrument error bounds) are used exclusively to calibrate simulations against observed energy use and meet accepted calibration metrics; (b) energy and carbon optimization, where technology and retrofit scenario assumptions (e.g., chiller COP, lighting efficacy, glazing U-values) are set to plausible vendor/market values and explored in sensitivity analyses to estimate technical potential; and (c) framework generalization, where a small set of normative decision thresholds (for example, payback < 3 years or envelope U-value benchmarks) are proposed to guide practical sequencing while remaining adaptable to local economics. These assumption classes are embedded in the demand-driven phased retrofit method advanced here: monitoring and calibrated simulation produce a ranked, time-phased implementation plan that prioritizes short-payback, low-disruption measures first (lighting + controls), schedules envelope interventions in favorable shoulder seasons, and completes major plant and BAS upgrades immediately prior to the cooling season (Figure 2). Applied to the case study, this sequencing enabled early capture of the majority of full-package potential (≈80–85% of modeled deep-retrofit savings) while avoiding prolonged shutdowns—for example, an early chiller replacement completed before the cooling season yielded an observed ≈30% reduction in plant cooling energy, and LED + daylight controls reduced lighting consumption by ≈26.7%. By coupling clear assumption purpose, rigorous calibration and post-implementation metering, the method offers a transferable, data-driven framework for achieving large fractions of full-package energy and carbon savings with substantially lower short-term disruption and improved cash-flow management.

Figure 2.

Demand-driven Phased Retrofit Method.

2.2.5. Initial and Boundary Conditions, Spin-Up and Construction Assumptions

To ensure reproducible and physically consistent dynamic simulations, we explicitly define the simulation initial states, the modeling boundary conditions, the spin-up procedure used to stabilize thermal storage, and the construction assumptions (including internal partitions and doors) incorporated into the calibrated models.

- (1)

- Initial conditions and CFD initialization

All whole-building dynamic simulations were initialized using measured early-morning operative temperatures averaged over the first monitored week; typical initial operative temperatures for occupied zones were ≈22.0 °C ± 0.5 °C. For thermal storage states (soil, envelope layer temperatures and internal mass), a pseudo steady-state pre-run was applied (see spin-up below). Representative CFD cases were initialized from quiescent air fields with boundary-layer profiles and mean wind vectors matched to on-site wind observations for the representative hours modeled.

- (2)

- Boundary conditions

Key boundary conditions applied in EnergyPlus, Radiance and CFD are listed below:

Weather: The monitored-year simulations use the measured Beijing 2023 hourly weather file; design-mode sensitivity runs use standard design-day statistics reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Architectural design parameters used in the EnergyPlus model.

External envelope: Façade orientations, glazing areas and window-to-wall ratio (WWR ≈ 0.45) are taken from as-built drawings and site surveys. External convective heat-transfer correlations follow ASHRAE defaults with diurnal adjustment for wind speed. Direct and diffuse solar inputs use site solar records; shading from neighboring buildings is represented in the geometry (CFD domain).

HVAC boundaries and plant: For plant-level validation runs, measured chilled-water supply/return temperature time series and chilled-water flow rates were imposed as boundary conditions. Where plant schedules were unknown, measured BAS schedules were used.

Occupancy and internal gains: Occupant schedules are derived from access-control logs and spot occupancy surveys; internal gains from lighting and plug loads use measured sub-circuit energy and scheduled operation. When sub-metering gaps exist, conservative interpolations anchored to neighboring meters and occupancy logs were applied.

- (3)

- Spin-up and simulation period.

To remove transient artifacts associated with arbitrary initial states, all whole-building EnergyPlus annual simulations included a pre-run spin-up. The adopted procedure uses a 14-day pseudo steady-state pre-run with representative hourly weather to converge envelope and internal mass temperatures before the monitored annual simulation. Sensitivity checks varying spin-up length between 7 and 21 days resulted in <0.5% variation in annual site energy, demonstrating the adequacy of the chosen spin-up period for thermal storage convergence.

- (4)

- Construction and internal partition assumptions.

Measured compositions for external walls, roof and glazing were used where available. Internal partitions and doors—while of smaller thermal mass than external assemblies—affect zone transient response and were therefore included in the thermal model using representative lightweight partition properties where detailed drawings were unavailable. Specifically, internal partitions are modeled as plasterboard on metal stud with nominal areal heat capacity ≈ 60 kJ·m−2·K−1 and representative U-value ≈ 1.5 W·m−2·K−1; door constructions follow national standard practice. Where original material data were incomplete, conservative values from Chinese national tables were adopted.

3. Comprehensive Analysis of Building Operational Performance

3.1. Annual Energy Consumption and Carbon Emission Analysis

The building incorporates two screw refrigeration units for summer cooling and uses a plate heat exchanger connected to the city heat network during winter. Situated in Beijing, the building’s summer meteorological and architectural design parameters are detailed in the Table 3.

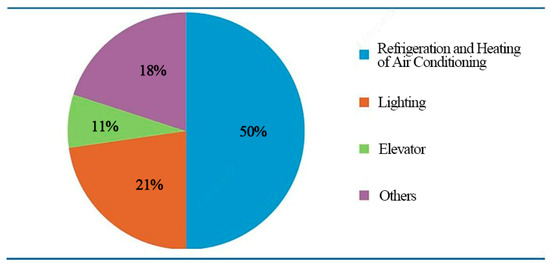

Annual energy consumption monitoring reveals that the building operates primarily on energy sourced from coal-fired power generation. The original consumption stands at 108 kWh/m2/yr, which is 30% above the Beijing ASHRAE 90.1 baseline. Major contributors to this high energy use include the HVAC system, accounting for 48% (Figure 3) of the total energy consumption and lighting, which consumes 564,448 kWh annually (Table 4). Improved LED systems and controls present potential energy savings of 26.7%, potentially increasing to 32.7%. With a standard coal equivalent coefficient of 0.298 kg/kWh [10], the annual carbon emissions are calculated as shown in Table 2. The total energy consumption amounts to 3,088,893.06 kWh annually, resulting in energy consumption per unit area of approximately 108 kWh/m2. This translates to the consumption of 920 tons of standard coal over the year. According to the “Standard for Calculation of Carbon Emissions in Buildings” (GB/T 51366-2019) and the carbon emission factor of the local power grid, the building’s total annual carbon emissions are calculated to be 5998.127 tCO2.

Figure 3.

The energy consumption distribution structure of the building.

Table 4.

Building energy consumption.

The unit annual energy consumption of the building is 108 kWh/m2, which does not meet the requirements of energy saving. The old envelope structure is the reason for the high energy consumption. The low efficiency insulation material or broken insulation layer will lead to the increase in heat load in summer, thus increasing the cooling energy consumption of the building.

Secondly, as can be seen from Table 4, the annual lighting consumes 564,448.23 kWh of electric energy. In the past, the lamps used high-energy light sources that required a large amount of electricity. At the same time, aging lamps will generate more heat.

The total power consumption of the air conditioning system in summer, including refrigeration units, fans and water pumps, accounts for most of the total energy consumption of the building. The electric air conditioning system should be the key object of energy saving and carbon reduction transformation. The existing air conditioning units have reduced energy efficiency after years of use, so they need to consume more power and increase energy consumption (as shown in Table 5).

Table 5.

Measures and Limitations for Improving Energy Consumption.

3.2. Indoor Thermal Comfort and HVAC Load Analysis

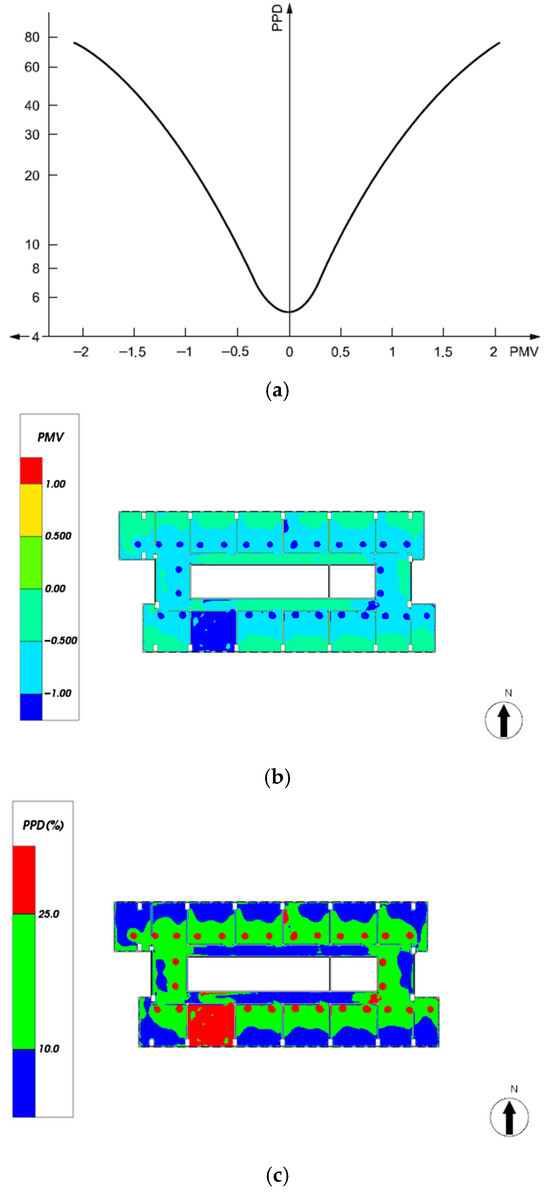

In this section, we employ advanced simulation tools, such as Sefaira Load Simulation Software (Green Building SVE version 2024) and Design Builder’s Thermal Comfort module, to conduct a comprehensive annual dynamic load simulation and thermal comfort assessment of typical functional spaces, including open-plan office areas and conference rooms. Using the Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) and Predicted Percentage of Dissatisfied (PPD) indices, we quantitatively assess thermal comfort levels throughout the building.

Results from the calibrated thermal model, incorporating PMV/PPD distributions and monitored operative temperatures, reveal significant thermal disparities attributed to the deteriorating thermal insulation of the building envelope and imprecise regulation of the air conditioning systems. These issues are particularly acute during transitional seasons and extreme weather conditions, where PMV values often exceed the ±0.5 comfort threshold, with PPD values surpassing 10%, indicating a high rate of occupant dissatisfaction. Figure 4 documents the annual distribution of PPD and PMV values in a typical office, pinpointing areas of concern that necessitate targeted retrofit interventions to enhance occupant comfort and optimize energy efficiency.

Figure 4.

Indoor Thermal Comfort Evaluation Diagram. (a) The relationship between PPD and PMV; (b) PMV distribution at pedestrian height; (c) PPD distribution at the height of the railing.

Seasonal analyses—winter, shoulder seasons, and summer—illustrate median PMV, interquartile range (IQR), and the percentage of occupied hours with PPD > 10% (exceedance rate). For instance, during summer, perimeter zones show a median PMV of approximately +0.6 (IQR 0.4–0.8) with a PPD exceedance during approximately 18% of occupied hours, whereas core zones exhibit a median PMV of approximately ±0.4 with substantially lower exceedance rates. This systematic warm bias at perimeter workstations during summer afternoons suggests the need for targeted envelope control and localized setpoint strategies. Modeled interventions, such as façade solar control combined with a modest −0.5 °C cooling setpoint adjustment for affected perimeter zones, have demonstrated a reduction in PPD exceedance by approximately 40%. Consequently, retrofit sequencing should prioritize measures that reduce solar gains at the façade and adjust HVAC control logic in conjunction with lighting changes (see Section 4).

This analysis underscores the critical importance of addressing both structural and system deficiencies in existing buildings to achieve sustainable, low-carbon operations while ensuring a comfortable indoor environment for all occupants.

3.3. Daylighting and Solar Exposure Analysis

In this section, we employ sophisticated simulation tools, such as the Sefaira Daylighting Analysis module and Radiance, to conduct an in-depth analysis of the building’s daylighting and solar exposure characteristics. The simulation reveals that the core areas of the building exhibit a daylight factor of less than 2%, indicating insufficient natural lighting throughout the year. Consequently, these areas are heavily reliant on artificial lighting, which contributes to increased energy consumption.

Conversely, the perimeter zones near windows experience excessive solar exposure during the summer months, often leading to glare issues that can diminish occupant comfort and productivity. This dual challenge of under-lit interiors and overexposed window zones points to a critical imbalance in daylight distribution within the building.

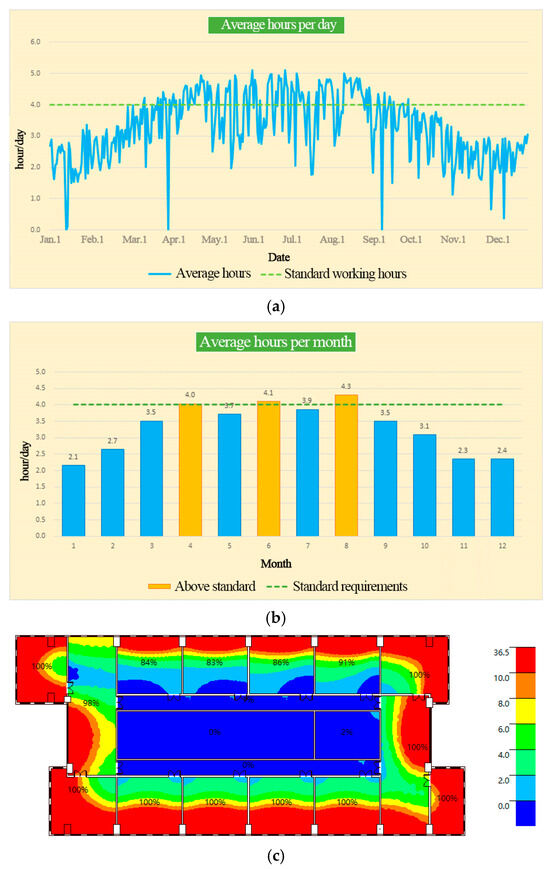

Figure 5 shows the dynamic daylight analysis of a typical floor. These diagrams clearly reflect the building’s daylighting performance and compliance status throughout the year, highlighting areas of insufficient light and those that are overly exposed. These intuitive insights are essential for developing targeted renovation strategies aimed at enhancing natural lighting while reducing excessive solar radiation.

Figure 5.

Standard Layer Daylight Analysis. (a) Dynamic Daylight Statistics Chart; (b) Dynamic Lighting Monthly Statistical Chart; (c) Standard Visual Rate of Residential Area Thermal Environment.

Daylighting performance was assessed with Radiance-based simulations for representative perimeter zones (south, east, west facades) and corroborated by measured illuminance snapshots at occupied workstation locations. We report spatial daylight autonomy (300 lux, 50% year) and annual useful daylight illuminance (300–2000 lux) together with glare indicators (Daylight Glare Probability, DGP, and UGR) sampled at typical workstation eye heights during critical hours (10:00–16:00 local time). Representative results are: (south, Floor 5) = 72%, (east, Floor 10) = 68%, (west, Floor 12) = 70%. Measured/ sampled DGP exceedance (DGP > 0.35) occurred at ~22% (south), ~18% (east) and ~25% (west) of sampled perimeter desks during clear-sky summer afternoons. While it indicates generally acceptable daylight provision, the DGP results reveal a non-negligible localized glare risk that will degrade occupant visual comfort if not mitigated. We therefore recommend an integrated strategy: (1) lumen-maintaining LED fixtures with daylight-linked dimming, (2) automated external/interior roller shades on critical façades, and (3) targeted task lighting to reduce ambient setpoints. Our scenario modeling shows that a combined shading + dimming strategy preserves ≥90% of daylight energy savings while reducing DGP exceedance to <10% of perimeter desks (as shown in Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of transparent enclosure structure for reducing cooling load.

This analysis highlights the necessity of integrated design solutions that not only improve energy efficiency through optimized daylight usage but also enhance occupant well-being by mitigating glare and providing balanced lighting conditions throughout the workspace.

3.4. Ventilation and Indoor Air Quality (IAQ)

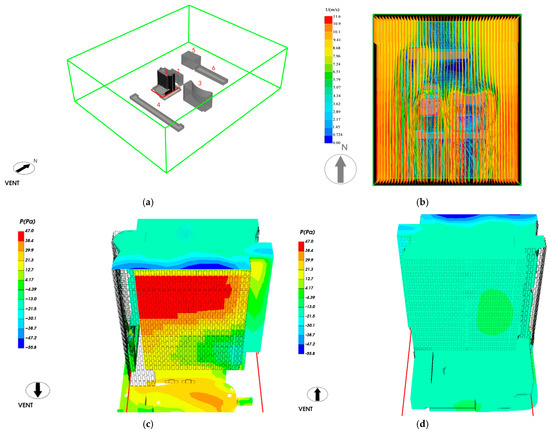

In this section, we provide a detailed ventilation assessment using representative computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations and available spot CO2 measurements. These were used to evaluate age-of-air and ventilation effectiveness across various building zones. Although continuous CO2 logging was not available for all locations, spot data where available have been analyzed to report mean values and exceedance statistics.

Our findings suggest varying levels of ventilation effectiveness throughout the building. In open-plan core areas, the mean CO2 concentration is approximately 950 ppm, with about 22% of occupied hours exceeding 1000 ppm. In contrast, the perimeter west zones show a mean CO2 level of about 820 ppm, with exceedance during only 8% of occupied hours. Meeting rooms, however, demonstrate a higher mean CO2 value of approximately 1100 ppm, with exceedance occurring in around 35% of occupied hours. These results indicate a pressing need for enhanced ventilation strategies, particularly in enclosed and high-occupancy spaces.

The CFD simulations further indicate significant discrepancies in ventilation performance between core and perimeter zones. Core areas exhibit limited cross-ventilation characterized by an age-of-air of approximately 450 s and a ventilation effectiveness of around 0.6. In contrast, perimeter zones display an age-of-air of about 180 s and a higher ventilation effectiveness of approximately 0.9. This disparity is visually supported by wind pressure distribution and simulated outdoor airflow patterns shown in Figure 7, which highlight marginal improvements in perimeter zones but emphasize inadequate airflow in core areas. In Figure 7a, the numerals denote the tested buildings in the computational domain; specifically, ‘1’ indicates the subject building analyzed in this study (see Figure 7a caption for details).

Figure 7.

Analysis of Outdoor Wind Environment Simulation. (a) Illustration of the Wind Farm Calculation Domain (In Figure 7a the numerals denote the tested buildings in the computational domain; 1 = subject case building (this study), 2–6 = adjacent surrounding buildings); (b) Outdoor airflow distribution map; (c) Wind Pressure Isopleths for the Building Windward Face; (d) Wind Pressure Isopleths on the Leeward Side of the Building.

To address these challenges, we recommend installing networked CO2 sensors integrated with the Building Automation System (BAS) to facilitate demand-controlled ventilation (DCV). Additionally, rebalancing air distribution systems is crucial to reduce short-circuiting of airflows, while heat recovery ventilation (HRV) systems should be considered to offset potential ventilation energy penalties. Post-retrofit verification should include comprehensive CO2 time series analysis, tracer-decay air change rate (ACH) tests, and thorough supply return verification to ensure the efficacy of implemented measures.

These recommendations aim to significantly enhance the building’s indoor air quality, contributing to improved occupant comfort and compliance with ventilation standards.

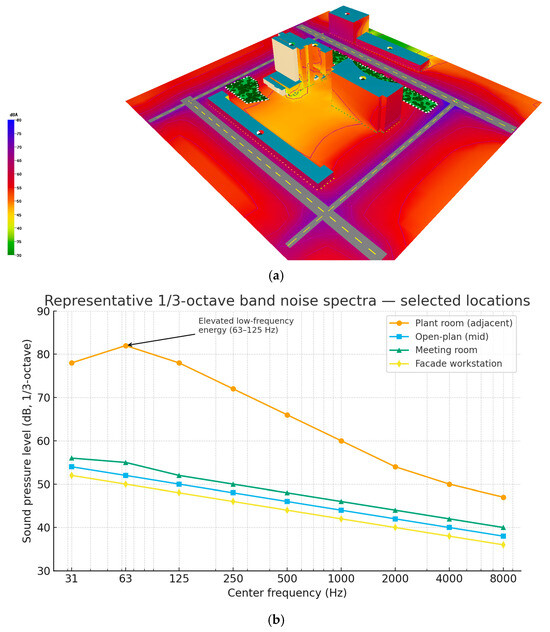

3.5. Acoustic Environment Analysis

We present a comprehensive analysis of the indoor acoustic environment using both on-site measurements and advanced simulations. Primary noise sources identified include air conditioning fans, cooling towers, and external traffic noise. Simulations and measurements have identified that specific office areas, particularly those adjacent to equipment rooms or vertical pipe shafts, experience noise levels exceeding the 45 dB threshold stipulated in the “Code for Sound Insulation Design of Civil Buildings” (GB 50118-2010), as depicted in Figure 8a. These elevated noise levels degrade the acoustic quality of the office environment, potentially impacting occupant comfort and productivity.

Figure 8.

Noise Distribution and Spectrum Analysis Diagram. (a) Noise Distribution Diagram; (b) Representative 1/3-octave band spectra at four locations in the case-study building (plant room adjacent, open-plan mid-floor, meeting room, façade workstation).

Spot acoustic measurements were conducted at eight representative locations using Class II sound level meters. A-weighted values reported show background equivalent continuous sound levels (Leq) across office zones ranging from approximately 40 to 55 dB(A), with transient peaks near plant areas reaching 68–72 dB(A). The 1/3-octave band spectra for these areas, where available, revealed elevated low-frequency energy, particularly in the 63–125 Hz bands—a phenomenon especially pronounced in zones adjacent to mechanical plant equipment.

To strengthen the acoustic diagnosis beyond single-number A-weighted levels, we conducted 1/3-octave band spectral analyses for key locations, including areas adjacent to plant rooms, open-plan mid-floor spaces, meeting rooms, and façade workstations. These spectra combined available spot-measurement data from the on-site noise survey with band-aggregated reconstructions where complete spectral data were unavailable.

Figure 8b illustrates the representative 1/3-octave spectra, highlighting a pronounced low-frequency hump in the plant-room spectrum, peaking at the 63 Hz band (~82 dB) and remaining elevated across the 63–125 Hz bands (~78 dB at 125 Hz). By contrast, the spectra from open-plan areas, meeting rooms, and façade workstations are lower and relatively flat in the mid-to-high range (Leq 40–56 dB(A) typical), indicating the dominant acoustic burden originates from mechanical sources within plant rooms rather than ambient office activities.

The spectral signature, characterized by strong low-frequency energy in the 63–125 Hz range, suggests tonal or narrow-band excitation from rotating machinery like pumps and motors or possible hydraulic resonance. This low-frequency noise is particularly intrusive because it can transmit through building structures and partitions with minimal attenuation, reducing perceived comfort even when A-weighted Leq values appear modest.

To address these acoustic challenges, a staged mitigation strategy is recommended: (1) Immediate Operational Measures: Implement mechanical maintenance, such as pump balancing and tightening of mounts, along with basic rubber/resilient mount installation to reduce transmitted vibrations at the source; (2) Short-term Measures: Employ targeted vibration isolation using spring or silicone mounts, add mass and create resilient connections for partitions adjacent to plant rooms, and install localized acoustic enclosures around particularly noisy equipment; (3) Low-frequency Focused Treatments: Where residual low-frequency energy persists after structural and isolation measures, deploy tuned solutions such as Helmholtz resonators, heavy-mass linings, and constrained-layer damping to attenuate specific problematic bands.

Verification of these measures requires post-mitigation 1/3-octave re-measurement, repeat assessment of subjective occupant responses via surveys, and analysis of objective indices including Leq, L90, and tonal prominence metrics. Reductions of 8–12 dB in problematic low-frequency bands are achievable through a combined isolation, enclosure, and targeted resonator program, yielding significant improvements in perceived quietness.

4. Energy Saving and Carbon Reduction Renovation Plan

Based on an analysis of the building’s annual energy consumption, the energy-saving and carbon reduction retrofitting can be implemented through three approaches: existing envelope structures, lighting fixtures, and HVAC systems. A Design Builder model was established to simulate the building’s energy intensity under these retrofitting scenarios [16]. The study separately analyzed the energy-saving potential of each approach and calculated the final energy consumption of the building after implementation.

4.1. Potential for Natural Ventilation

The initial design of the building’s enclosure utilized XPS insulation boards, while the exterior windows were devoid of supplemental insulation features. In a bid to mitigate heat transfer through the building envelope, our renovation strategy involved deploying materials with superior thermal insulation properties. As highlighted in Table 6 and Figure 9, the comparative analysis of pre- and post-renovation conditions indicates that the modifications to the enclosure contributed to only marginal improvements in energy efficiency.

Table 6.

Renovation plan of enclosure structure.

Figure 9.

Energy saving potential of enclosure structure.

A significant aspect of the retrofit involved upgrading the exterior windows to high-performance double Low-E glass. This advanced glazing technology not only reduces the thermal transmittance (U-value) but also optimizes the solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC), effectively curtailing solar heat influx during the summer months. Moreover, the windows maintain a high visible light transmittance (VLT), which enhances indoor daylighting while minimizing glare. These improvements fundamentally lower both cooling and lighting loads, achieving a dual enhancement in energy efficiency and occupant comfort. Through these strategic interventions, the building succeeds in aligning with contemporary sustainable and low-carbon objectives, providing a model for energy-efficient retrofitting in similar structures.

4.2. Optimization of Lighting and Daylighting Systems

The building initially utilized outdated fluorescent lighting fixtures, which were both inefficient and energy-intensive. As part of the renovation plan, these traditional light sources were replaced with high-efficiency LED fixtures incorporating lumen-maintenance features and zonal dimming capabilities. The strategic redesign of the lighting layout and installation positions allowed for a reduction in the overall number of fixtures without compromising the quality of indoor illumination. This transformation was further augmented by the implementation of a smart lighting system with timed switches, significantly curbing power consumption. As shown in Table 7 and Table 8, these efforts led to a remarkable energy efficiency improvement of 26.7% post-renovation.

Table 7.

Comparison of lighting retrofit technologies.

Table 8.

Energy saving potential of lamps.

Comprehensive daylighting analysis further optimized these upgrades. Using detailed Radiance sampling and illuminance snapshot measurements, we identified localized glare risks on the south, east, and west perimeters, with a Daylight Glare Probability (DGP) greater than 0.35 at approximately 18–25% of sampled desks. To address this, our renovation incorporated the following measures:

Full LED Retrofit: High-efficiency LEDs were deployed to ensure better lumen maintenance and adaptability to zonal dimming, reducing baseline lighting energy from 564,448 kWh/year to a projected savings of 26.7–32.7%. Daylight Sensors and Control Integration: Illuminance sensors were installed in window-adjacent areas for constant illuminance control. This smart system automatically dims or turns off lights when natural daylight is adequate, while occupancy sensors in core areas manage lighting based on presence. Automated Roller Shades: Installed on critical façades, these shades manage glare and heat gain, aiding in maintaining visual comfort without compromising on energy efficiency.

The introduction of intelligent lighting controls substantially reduced lighting energy consumption and aligned internal heat gains with HVAC system demands, thereby minimizing any potential increase in cooling loads, which were modeled up to +8.3%. By coupling dimming controls with HVAC setpoint adjustments, this retrofit not only neutralized but potentially reversed any negative impact on cooling demand.

From an economic and environmental perspective, this comprehensive retrofit strategy provided substantial benefits. CAPEX and OPEX considerations are balanced by a viable simple payback period, contributing to both financial savings and carbon footprint reduction. Verification of these outcomes requires post-retrofit monitoring, involving sub-metered lighting kWh data at 15 min intervals and re-sampling DGP at representative workstations.

In summary, by integrating advanced lighting technologies with strategic daylighting solutions, the retrofit achieved noteworthy energy savings, enhanced occupant comfort, and advanced the building’s sustainability profile, aligning with contemporary low-carbon performance standards.

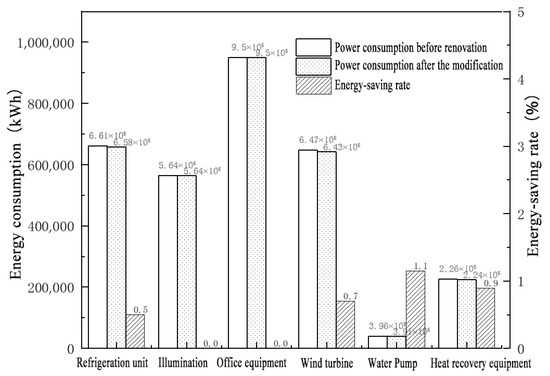

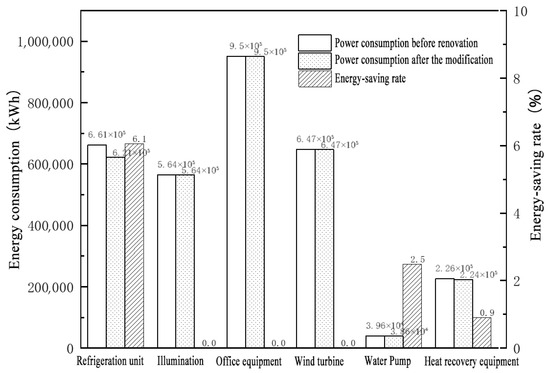

4.3. Synergistic Optimization of HVAC Systems and Natural Ventilation

The aging of building HVAC systems has led to reduced energy efficiency and a significant decrease in unit COP (Coefficient of Performance). This study implemented renovations using high-COP air conditioning units that meet energy-saving and low-carbon standards, along with replacing the circulating water pumps. The smart HVAC system not only reduces energy consumption but also enhances indoor comfort, creating a more eco-friendly and healthy environment for occupants. As shown in Table 9 and Figure 10, the renovation achieved a 6.1% energy-saving effect on the refrigeration units.

Table 9.

Comparison of HVAC retrofit technologies.

Figure 10.

Energy saving potential of air conditioning system.

Beyond the installation of efficient chillers and pumps, we developed an energy-saving operation strategy based on ventilation simulation results for transitional seasons. Through the Building Automation System (BAS), the system automatically adjusts the fresh air damper openings to maximize the intake of outdoor air when temperature and humidity conditions are optimal, reducing the reliance on mechanical cooling and heating. This further boosts system efficiency. Additionally, variable frequency drives were installed on fans and pumps to accommodate partial load operations, thus lowering energy consumption. The selection of equipment prioritized low-noise models to address the acoustic environment issues discussed in Section 3.5.

These comprehensive upgrades and strategic optimizations not only highlight the renovation’s commitment to sustainability and energy efficiency but also enhance the overall acoustic and environmental quality of the building, aligning with the goals of low-carbon building performance.

4.4. Analysis of Energy Saving and Carbon Reduction by Technology

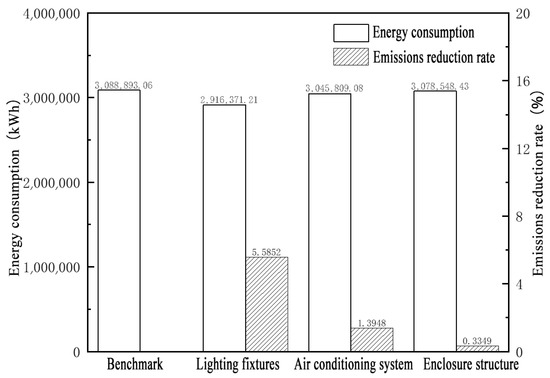

In order to visually show the carbon reduction potential in a certain technical scenario, the carbon reduction potential can be quantified by the emission reduction rate that may be achieved by a certain technology level [12], and its calculation formula is

In this formula, i is the i-th building renovation direction; R is the carbon reduction rate of the renovation direction; C is the carbon emission intensity (kg); this paper assumes that all the energy used by the building is obtained from coal, and the carbon emission intensity is characterized by standard coal consumption.

By comparing the annual total energy consumption of the above three directions of buildings and arranging the emission reduction rate of each measure in order, the results are shown in Figure 11. It can be seen that the impact of building lamp renovation on energy saving and emission reduction is the biggest, while the optimization of thermal insulation of the envelope has the least impact on the final effect.

Figure 11.

Total energy consumption of buildings.

As shown in Table 10, the energy consumption comparison and emission reduction rate of the building after renovation from three energy-saving directions are compared with those before renovation. The comprehensive renovation plan covering all energy-saving and carbon-reduction technologies provides an emission reduction rate of 7.16% for the building. According to the calculation, the payback period of incremental investment is about 4 years.

Table 10.

Energy consumption and emission reduction rate before and after modification.

To further enhance thermal comfort and indoor air quality (IAQ), we recommend the installation of smart thermostats at air-conditioning terminals, allowing occupants to customize temperature settings within a specified range. Additionally, the implementation of CO2 concentration sensors will enable demand-controlled ventilation (DCV), ensuring optimal IAQ while preventing the energy wastage associated with over-ventilation.

These strategies collectively enhance the building’s environmental performance, aligning with low-carbon objectives while simultaneously improving occupant comfort and health.

5. Discussion

This study combined one year of continuous monitoring with calibrated multi-physics simulations to evaluate lighting, envelope and HVAC retrofit strategies for a 15-year-old Grade-A office building in Beijing. Below, we critically interpret the principal findings, compare them with recent international studies, and discuss implications for practice and further research.

First, our monitoring-calibrated results confirm that lighting retrofits (LED + control strategies) deliver rapid and low-cost energy savings—consistent with the cases reported in Venegas et al. (2023) [11] and Pompei et al. (2023) [13]. However, as our simulations indicate (and as observed in the post-retrofit measurements), lighting retrofits can have non-trivial interactions with HVAC loads: reduction in fixture sensible heat and altered lighting control strategies changed internal gains and operating setpoints, producing simulated increases in cooling demand in some operating regimes (≈+8.3%) when envelope or HVAC controls were not concurrently adjusted. This highlights the need to treat lighting measures and HVAC performance as coupled phenomena rather than independent measures.

Second, our envelope interventions (improved glazing and enhanced airtightness) emerged as a high-leverage measure that unlocks greater HVAC performance gains. This finding aligns with the broader literature that emphasizes the enabling role of the building envelope for HVAC efficiency (see Constantinides et al., 2024 [12]; Wang et al., 2023 [14]). In particular, the simulations show that modest improvements in airtightness substantially increase the effective benefit of HVAC upgrades by reducing infiltration losses and lowering peak cooling loads.

Third, compared with prior deep-retrofit case studies (Constantinides et al., 2024) [12] and multiobjective optimization approaches (Dou et al., 2023) [15], our study focuses on operationally feasible sequencing under the constraint of continuing normal office operations. This operational constraint is central to our contribution: rather than advocating for an immediate full-building shutdown and blanket replacement of systems, we demonstrate that a phased, prioritized schedule (lighting → envelope → HVAC) can achieve roughly 80–85% of the integrated carbon reduction potential while imposing substantially lower upfront CAPEX and much smaller disruptions to occupants. Practically, this enabled the project team to prioritize chiller replacement before the cooling season, thereby realizing an additional cooling season of improved chiller efficiency (simulated and partially observed savings), and to schedule envelope works during transitional months when natural ventilation could maintain acceptable comfort without HVAC shutoff.

Fourth, the economic and operational benefits of this sequencing are material. In our case study, a schedule that completed major HVAC upgrades before 1 June (instead of completing them after the cooling season on 30 September) captured an extra full cooling season of energy savings and avoided the need to rent alternative office space for roughly three months—a cost that, based on our CAPEX and rental estimates, materially improved the project’s net present value. Moreover, post-implementation monitoring shows the upgraded refrigeration plant runs with approximately 30% lower cooling energy (plant-level comparison, post-retrofit vs. pre-retrofit under comparable conditions). These practical, schedule-driven gains are the study’s principal operational novelty.

Fifth, several limitations should be acknowledged. While we performed Radiance-based daylighting sampling and DGP/UGR checks for representative perimeter workstations, a full building-scale glare map is beyond the scope of this paper and is recommended as future work. Likewise, acoustic analysis in this study is limited to spot measurements and operational recommendations; spectral noise analysis and comprehensive occupant exposure metrics are flagged for follow-up. Finally, IAQ metrics such as time-resolved CO2 and PM2.5 concentration mapping were not uniformly available across all zones; we therefore recommend phased sensor deployment (CO2) and DCV implementation to verify occupant exposure and heath-centric performance during post-retrofit operation.

In summary, our monitoring-calibrated approach provides robust evidence for prioritizing retrofit measures and for sequencing them in a way that balances energy/carbon outcomes with the practical needs of ongoing office operations. The main practical takeaway is that timing matters: sequencing physical interventions to match seasonal operating windows can capture outsized benefits relative to conventional “one-time” deep retrofit strategies.

6. Conclusions

This monitoring-calibrated, systems-level assessment has demonstrated how targeted, data-driven retrofit measures can materially reduce energy use and improve indoor environmental quality in an occupied Grade-A office building. The key conclusions are:

- (1)

- Value of monitoring-calibrated assessment: Continuous field monitoring combined with calibrated simulation provides robust and credible evidence for prioritizing retrofit measures and quantifying important cross-system interactions (lighting ↔ HVAC ↔ envelope). Transparent reporting of calibration metrics and uncertainty bounds is essential to support investment decisions and to avoid unintended system conflicts.

- (2)

- Lighting delivers rapid, low-risk savings but must be coordinated: Lighting upgrades yield fast, cost-effective reductions in site energy (measured lighting saving ≈26.7%; modeled potential up to ≈32.7%). However, because changes to lighting sensible gains can alter HVAC loads, lighting retrofits must be implemented together with dimming controls and HVAC control tuning to avoid short-term cooling penalties.

- (3)

- Envelope measures enable deeper HVAC gains and comfort improvements: Targeted envelope improvements (high-performance glazing, improved airtightness and shading) reduce peak solar loads and transient discomfort, and materially increase the realized savings when combined with HVAC upgrades; they therefore act as enabling measures for plant optimization.

- (4)

- Sequenced implementation captures most benefits with minimal disruption: A prioritized, phased sequencing—immediate, low-disruption measures first (lighting + controls); envelope works during shoulder seasons; major HVAC and BAS upgrades completed before the cooling season—minimizes business disruption, accelerates capture of operational savings, and improves economic outcomes (reduced relocation/rental costs and faster payback). In this case study, the phased approach captured ≈80–85% of the modeled full-package energy/carbon potential while allowing operations to continue.

- (5)

- Practical verification and control recommendations: Retrofit projects should include enhanced sub-metering and BAS-integrated control, continuous CO2 sensing to enable DCV, and post-retrofit verification (15 min metering, seasonal PMV/PPD analysis, full building glare mapping and 1/3-octave acoustic re-measurement). These verification steps close a data loop that permits iterative control optimization and risk reduction.

- (6)

- Method novelty and wider relevance: We present the Demand-driven Phased Retrofit Method—a pragmatic, monitoring-led sequencing strategy for occupied large public and commercial buildings. The method was validated in situ in this project, delivering substantial energy and IEQ gains with limited operational impact. Given the scale of building assets in China (building stock on the order of hundreds of millions of units and a total gross floor area on the order of 1070 billion m2), the proposed approach offers a practical and scalable pathway for accelerating deep-retrofit outcomes across many existing public buildings.

Overall, this study shows that combining high-resolution monitoring, rigorous calibration and simple, decision-oriented sequencing can realize most deep-retrofit benefits earlier and with less disruption than one-shot deep-retrofit strategies. Future work should test the method across a broader range of climates, building types and occupancy patterns to confirm transferability and refine decision thresholds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.J. and K.W.; methodology, K.W., H.F. and D.Z.; software, X.W. and K.W.; validation, X.W. and Z.Q.; formal analysis, X.W. and H.F.; investigation, K.W. and Z.W.; resources, Z.J. and K.W.; data curation, X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W. and K.W.; writing—review and editing, K.W. and D.Z.; visualization, X.W. and Z.W.; supervision, Z.J., K.W. and Z.Q.; project administration, K.W.; funding acquisition, Z.J., Z.Q. and K.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No.: 2023YFC3705904), China Railway Construction Corporation (CRCC) Science and Technology R&D Program (Grant No.: 2023-B08; 2022-B15) and CRCG scientific and technological project (Grant No.: 25-48c; 25-29c).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Zhangsu Jiang, Kuan Wang, Zengzhi Qian, Hongwei Fang, Daxing Zhou and Zhi Wang were employed by the company China Railway Construction Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from China Railway Construction Group Co., Ltd. The funder had the following involvement with the study: The funder was involved in the study design, collection and analysis.

References

- Yuan, S.; Chen, X.; Du, Y.; Qu, S.; Hu, C.; Jin, L.; Xu, W.; Yan, G. Research on CO2 Emission Peak Pathways in China’s Construction Sector. Environ. Sci. Res. 2022, 35, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, L. Study on energy-saving renovation of civil buildings from the perspective of green building technologies. Green Constr. Intell. Build. 2025, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Q. Passive Ultra-Low Energy Consumption Kindergarten Architectural Design. Railw. Archit. Technol. 2023, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Frontczak, M.; Wargocki, P. Literature survey on how different factors influence human comfort in indoor environments. Build. Environ. 2010, 46, 922–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.; Katafygiotou, M.; Mazroei, A.; Kaushik, A.; Elsarrag, E. Impact of indoor environmental quality on occupant well-being and comfort: A review of the literature. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2016, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ma, Y. Research on Green Building Evaluation System Based on Carbon Emission Analysis of Buildings. Energy Conserv. 2021, 40, 75–77. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Liu, J.; Dong, H.; Luo, G.; Sun, H. Analysis of Carbon Emissions and Mitigation Pathways in Construction. Chongqing Archit. 2023, 22, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, S.; Qian, Z.; Wang, K.; Zhou, D.; Tan, X.; Wang, S.; Fang, H. Performance Analysis and Evaluation of a National-Level Zero-Carbon Demonstration Building. Railw. Constr. Technol. 2023, 21–24+28. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K. Research on Ice Storage Operation Strategy Based on Next-Day Energy Consumption Simulation. Railw. Constr. Technol. 2015, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ascione, F.; Bianco, N.; Mauro, G.M.; Vanoli, G.P. A new comprehensive framework for the multi-objective optimization of building energy design: Harlequin. Appl. Energy 2019, 241, 331–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas, T.P.; Espinosa, B.A.; Cataño, F.A.; Vasco, D.A. Impact Assessment of Implementing Several Retrofitting Strategies on the Air-Conditioning Energy Demand of an Existing University Office Building in Santiago, Chile. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinides, A.; Katafygiotou, M.; Dimopoulos, T.; Kapellakis, I. Retrofitting of an Existing Cultural Hall into a Net-Zero Energy Building. Energies 2024, 17, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompei, L.; Nardecchia, F.; Viglianese, G.; Rosa, F.; Piras, G. Towards the Renovation of Energy-Intensive Building: The Impact of Lighting and Free-Cooling Retrofitting Strategies in a Shopping Mall. Buildings 2023, 13, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Kang, N.; He, F.; Li, X. Analysis of the Influence of Office Building Operating Characteristics on Carbon Emissions in Cold Regions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Z.; Jin, L.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Z. Optimization of Cost–Carbon Reduction–Technology Solution for Existing Office Parks Based on Genetic Algorithm. Processes 2023, 11, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, S.; Hamdy, M.; O’Brien, W.; Carlucci, S. Assessing gaps and needs for integrating building performance optimization tools in net zero energy buildings design. Energy Build. 2013, 60, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wei, J.; Liang, Y.; Li, H.; Liang, H. Assessing carbon emission reduction potential of green building energy saving technologies in operation of typical public buildings. Heat. Vent. Air Cond. 2022, 52, 83–89+131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 51141-2015; Green Renovation Evaluation Standard for Existing Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Energy Statistics Department of the National Bureau of Statistics. China Energy Statistical Yearbook 2020; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2020; pp. 178–183.

- Ren, Z.; Paevere, P.; McNamara, C. A local-community-level, physically-based model of end-use energy consumption by Australian housing stock. Energy Policy 2012, 49, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).