Retrofitting for Sustainable Building Performance: A Scientometric–PESTEL Analysis and Critical Content Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

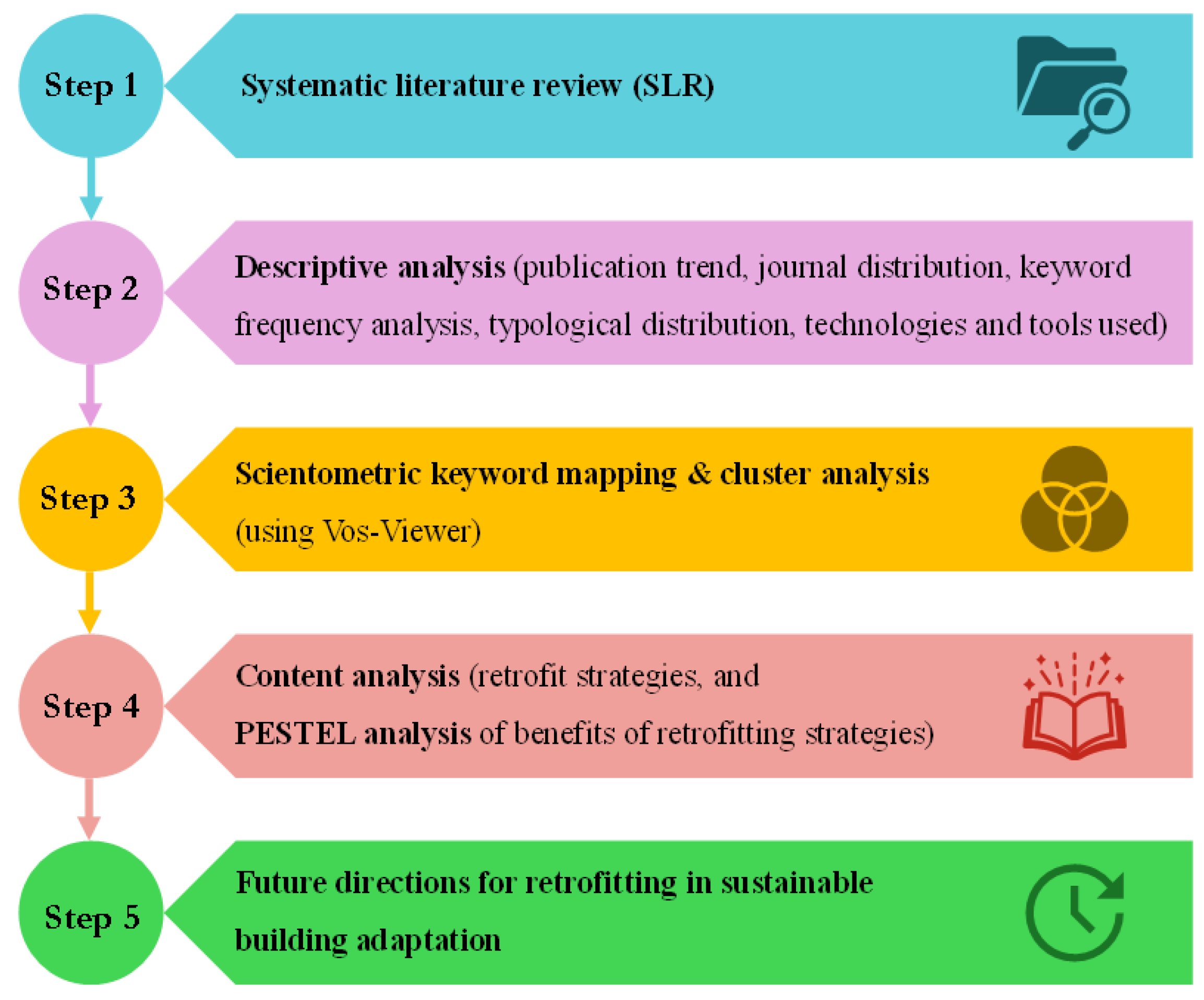

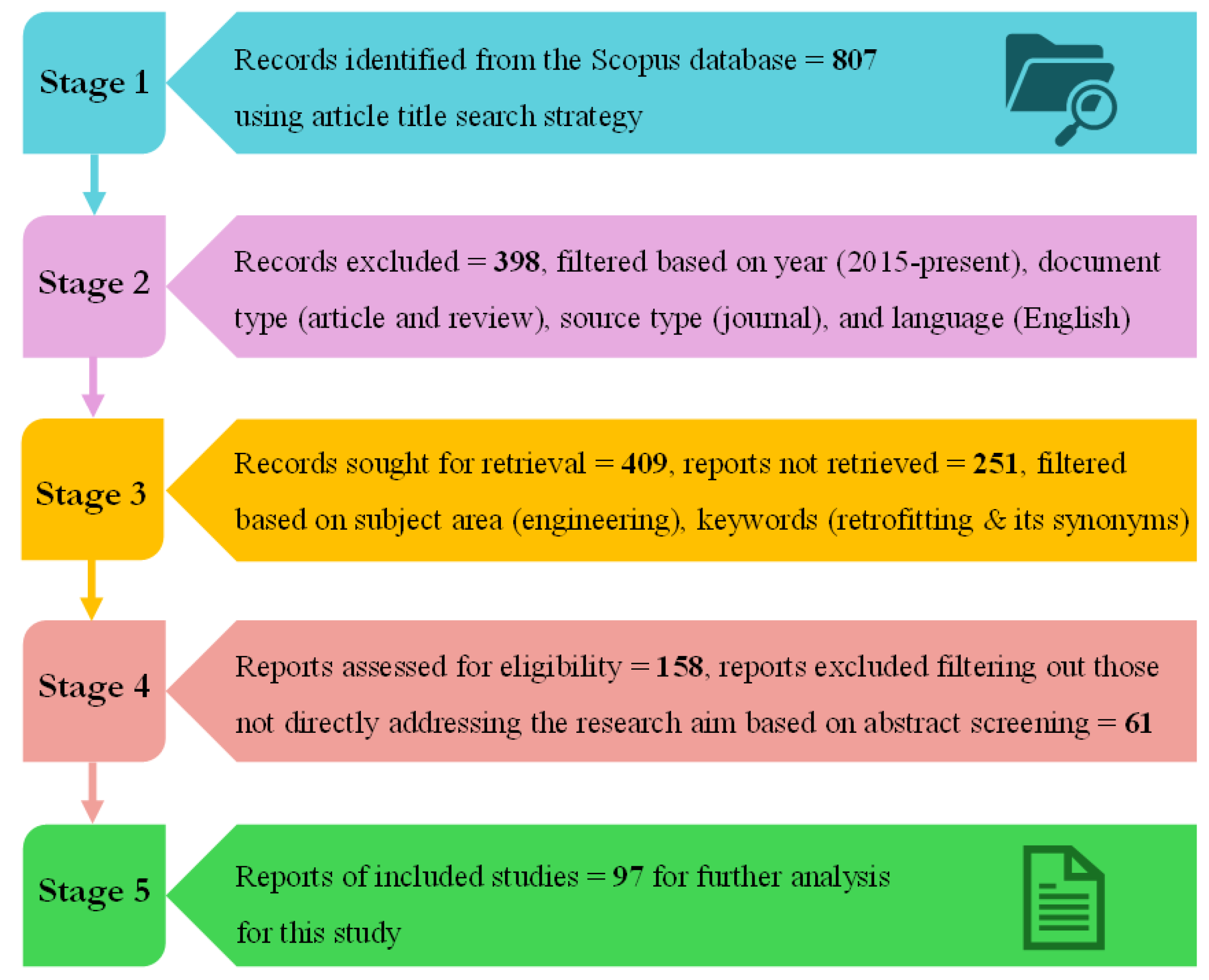

2. Research Method

Systematic Literature Review

3. Results

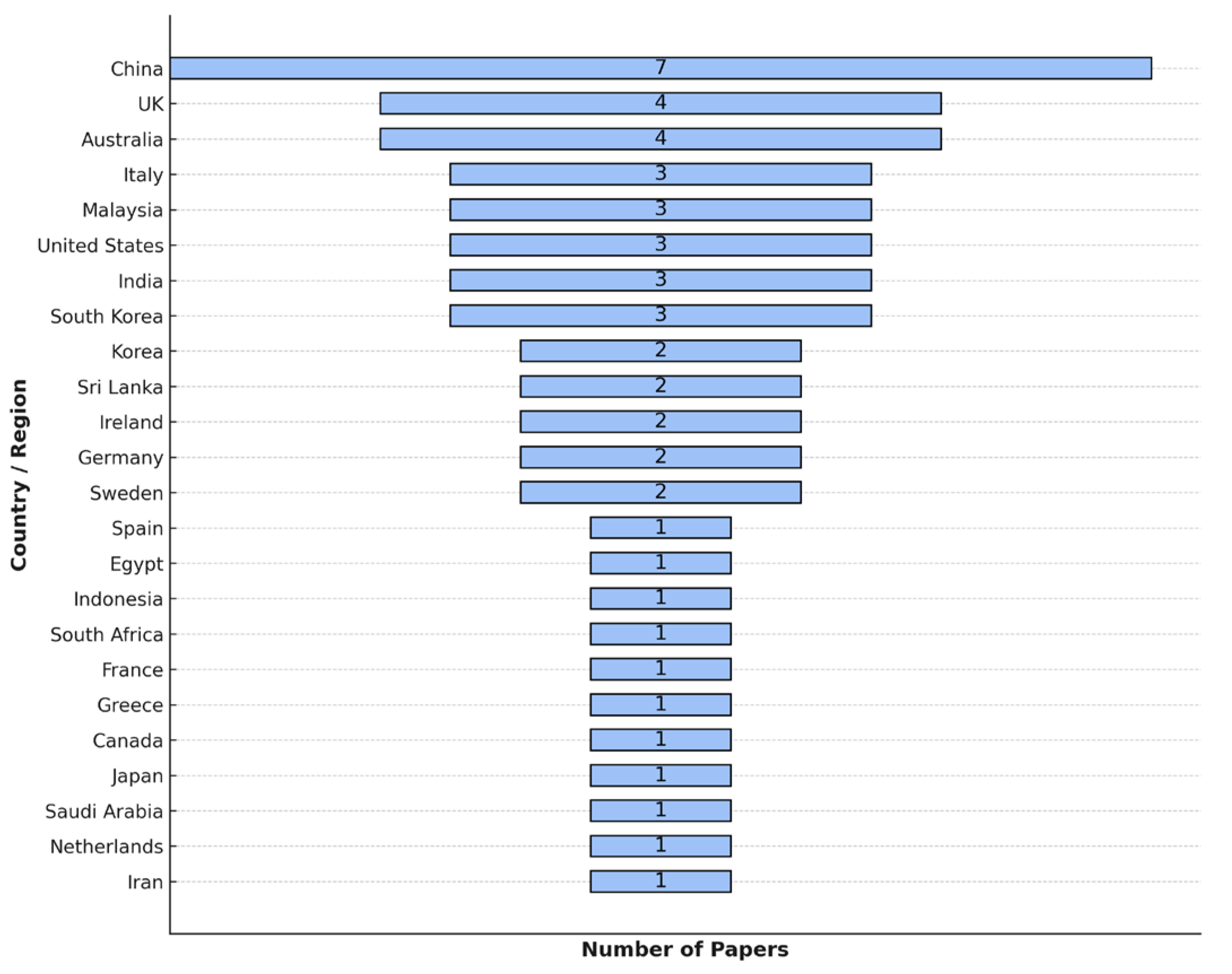

3.1. Descriptive Results

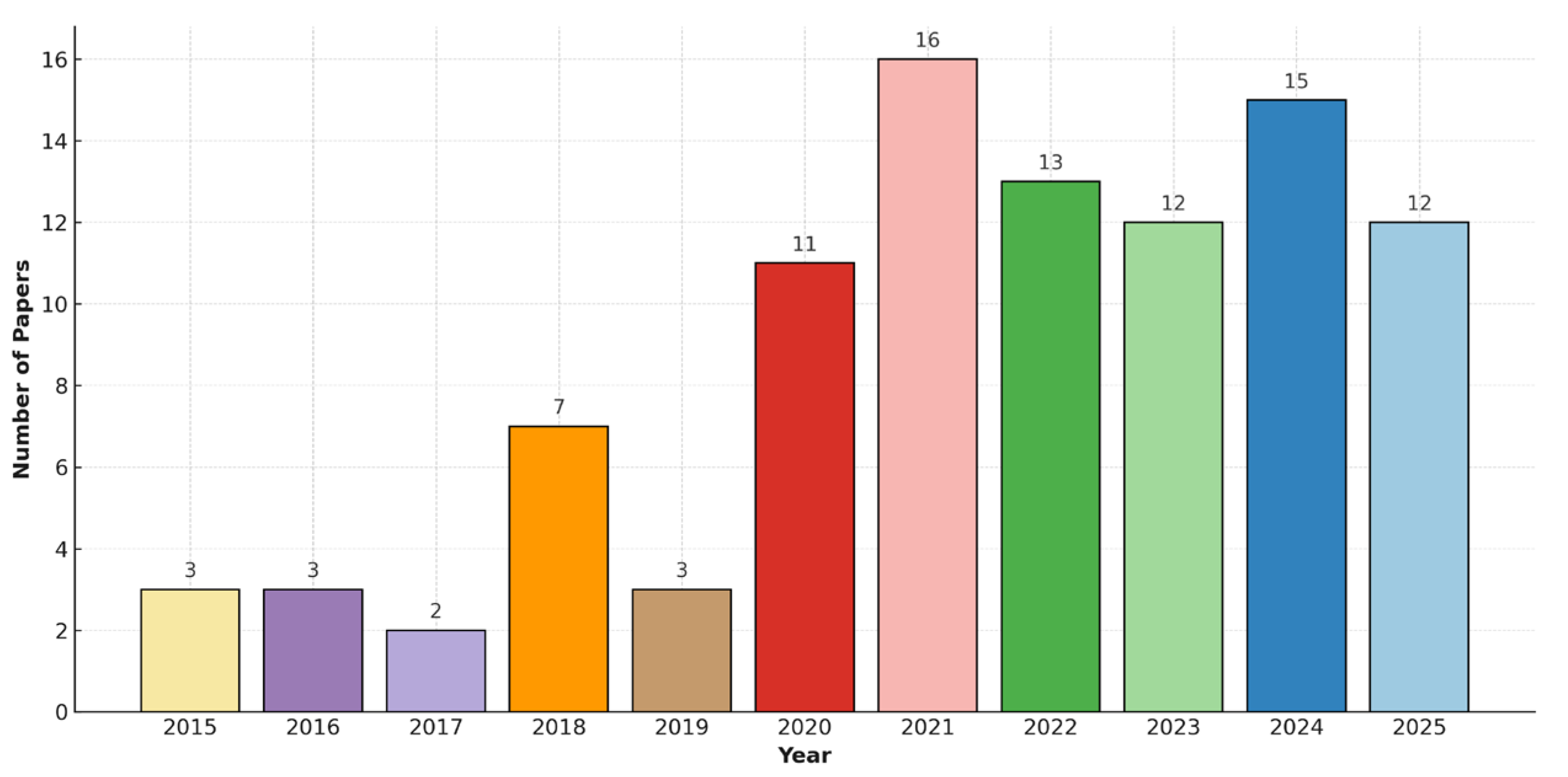

3.1.1. Year-Wise Publication Trends in Building Retrofit Literature

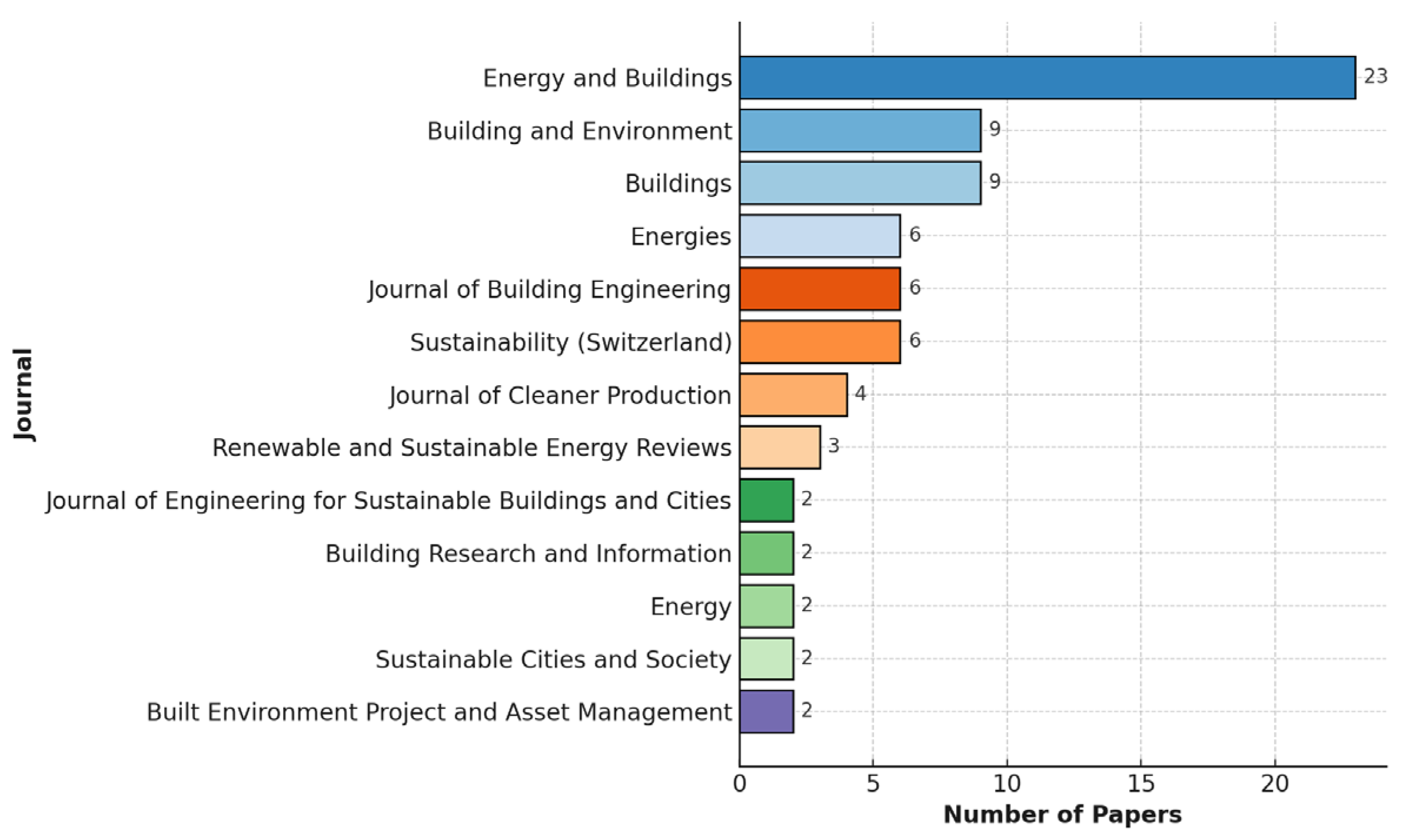

3.1.2. Distribution of Retrofitting Studies by Journal

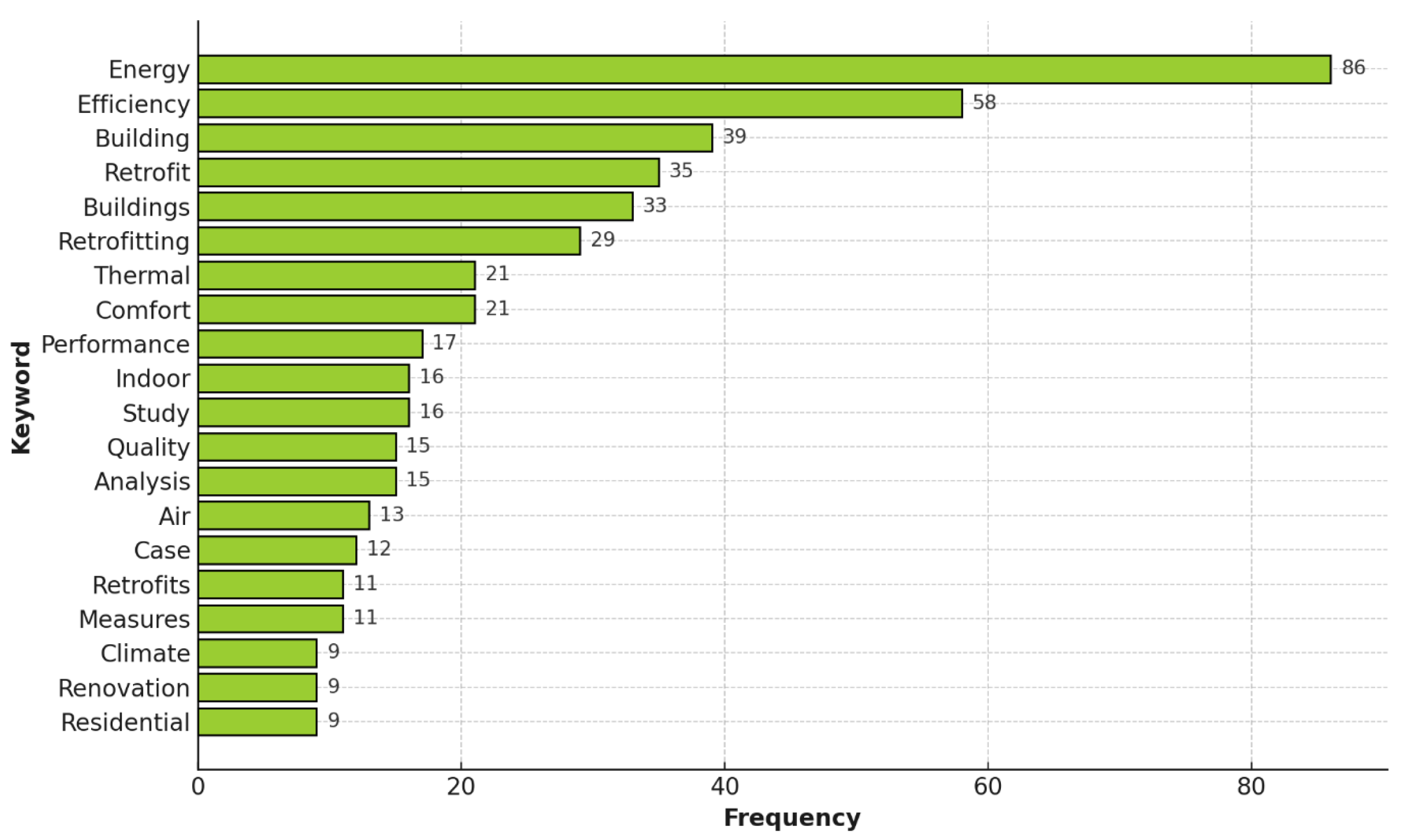

3.1.3. Keyword Frequency Analysis in Retrofitting Literature

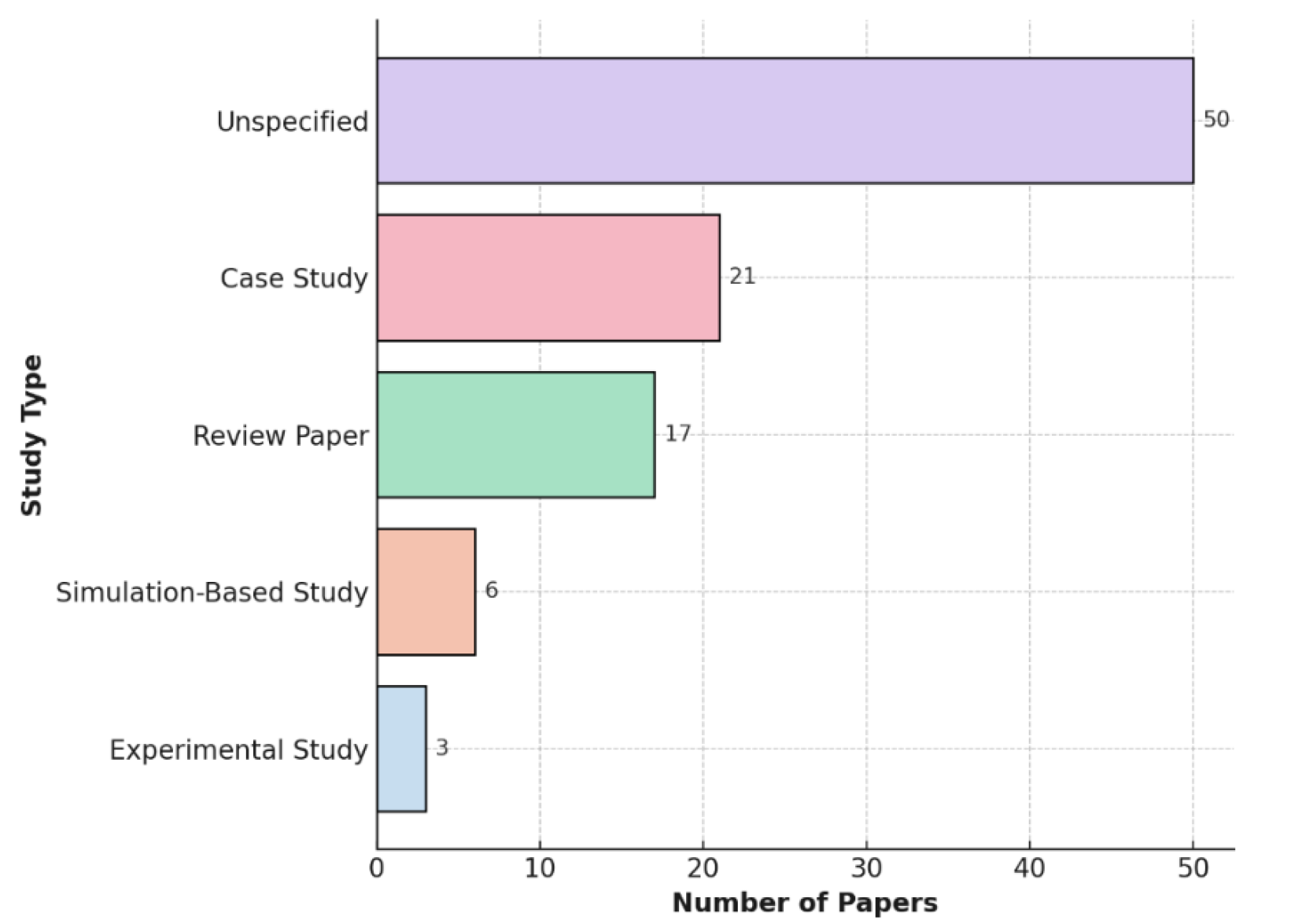

3.1.4. Typological Distribution of Retrofitting Studies

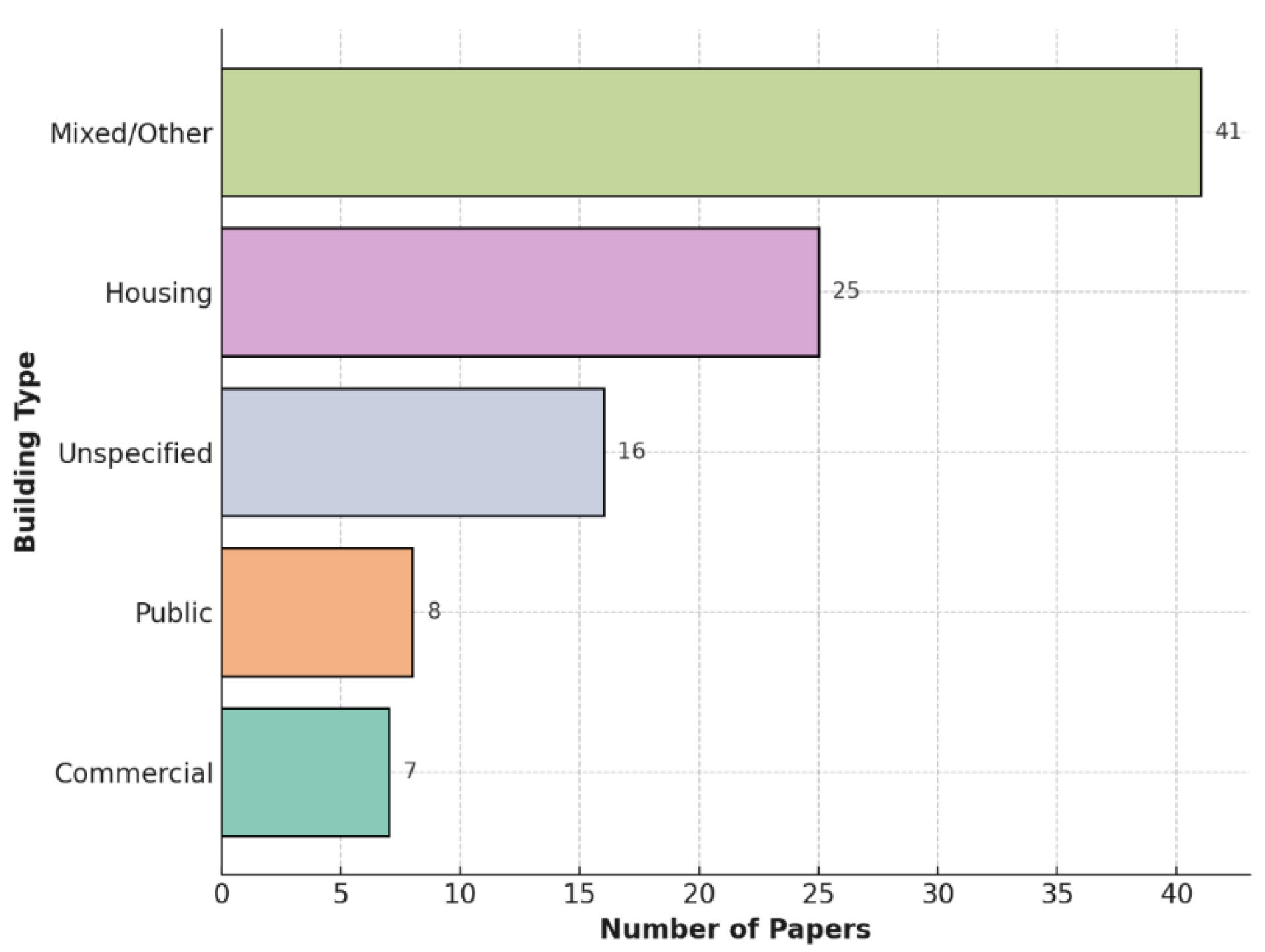

3.1.5. Building Typologies in Retrofit-Focused Literature

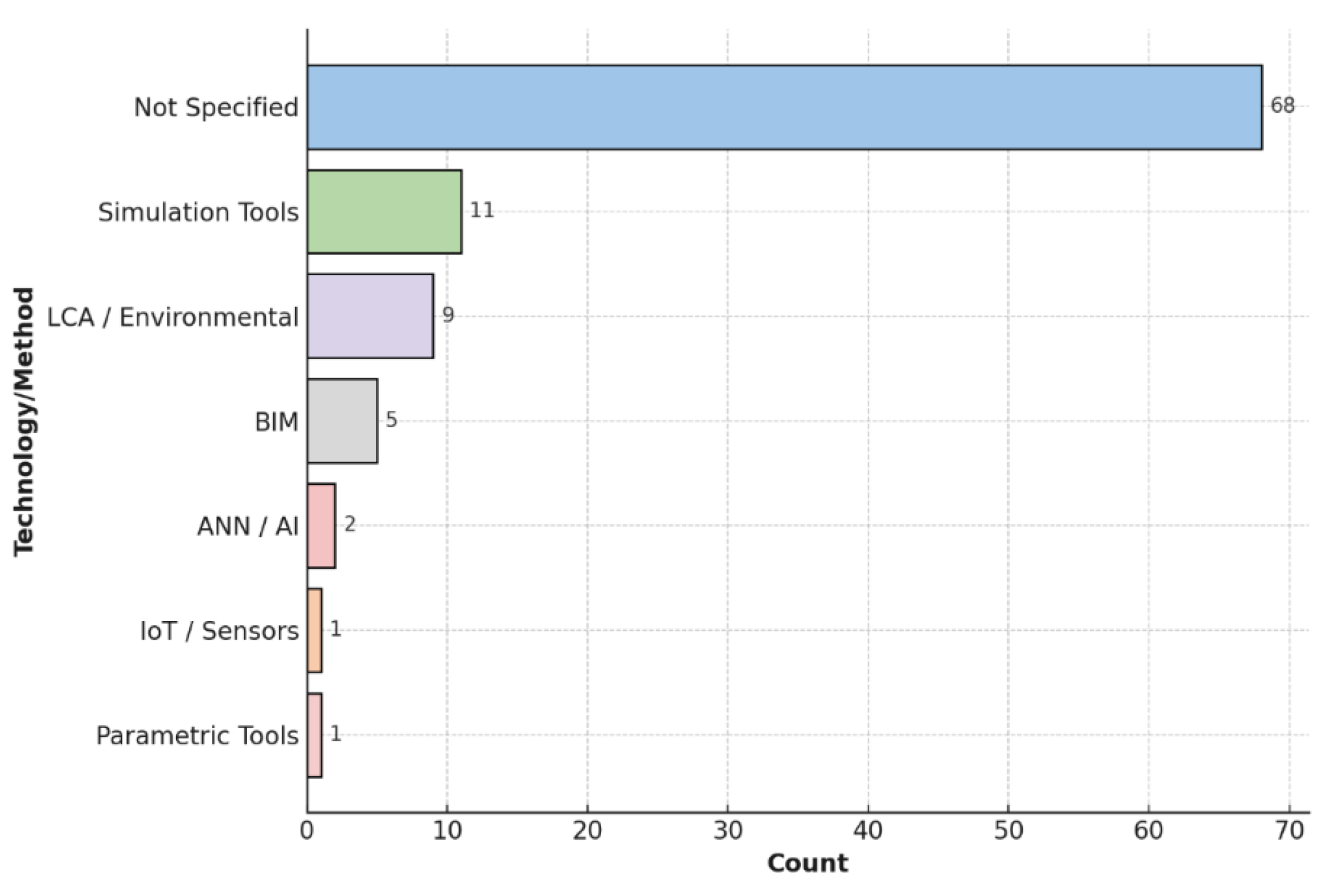

3.1.6. Technological Tools and Analytical Approaches in Retrofit Research

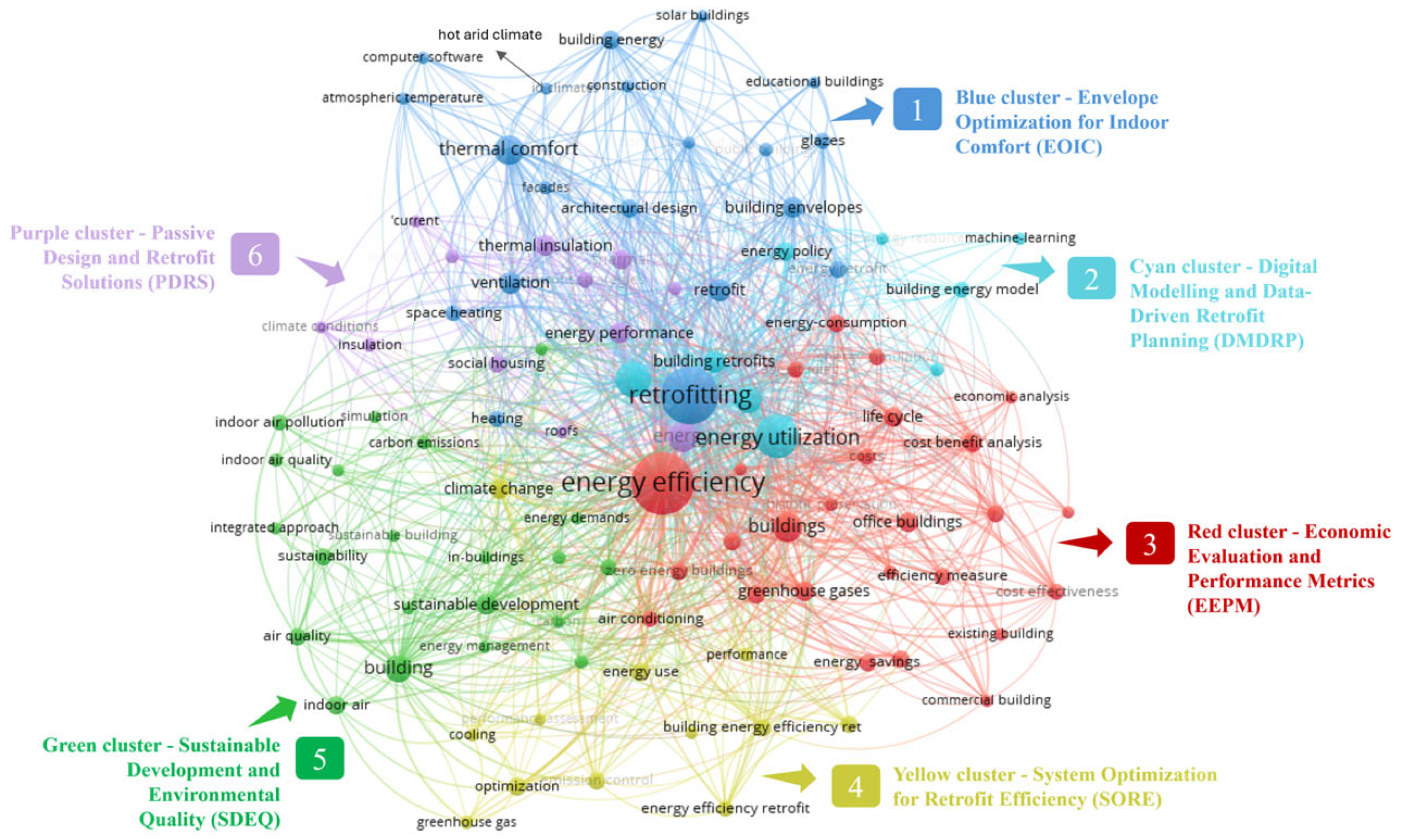

3.2. Scientometric Keyword Mapping and Cluster Analysis

3.2.1. Clusters in Retrofitting Research

Blue Cluster—Envelope Optimisation for Indoor Comfort

- Critical appraisal of this cluster

Cyan Cluster—Digital Modelling and Data-Driven Retrofit Planning

- Critical appraisal of this cluster

Red Cluster—Economic Evaluation and Performance Metrics

- Critical appraisal of this cluster

Yellow Cluster—System Optimisation for Retrofit Efficiency

- Critical appraisal of this cluster

Green Cluster—Sustainable Development and Environmental Quality

- Critical appraisal of this cluster

Purple Cluster—Passive Design and Retrofit Solutions

- Critical appraisal of this cluster

Interrelationships Among Clusters

3.2.2. Methodological Approaches and Technological Strategies

Digital and Simulation-Based Approaches

Integrating Renewables and Structural Upgrades in Retrofitting Strategies

Advanced Materials and Insulation Techniques

3.3. Content Analysis

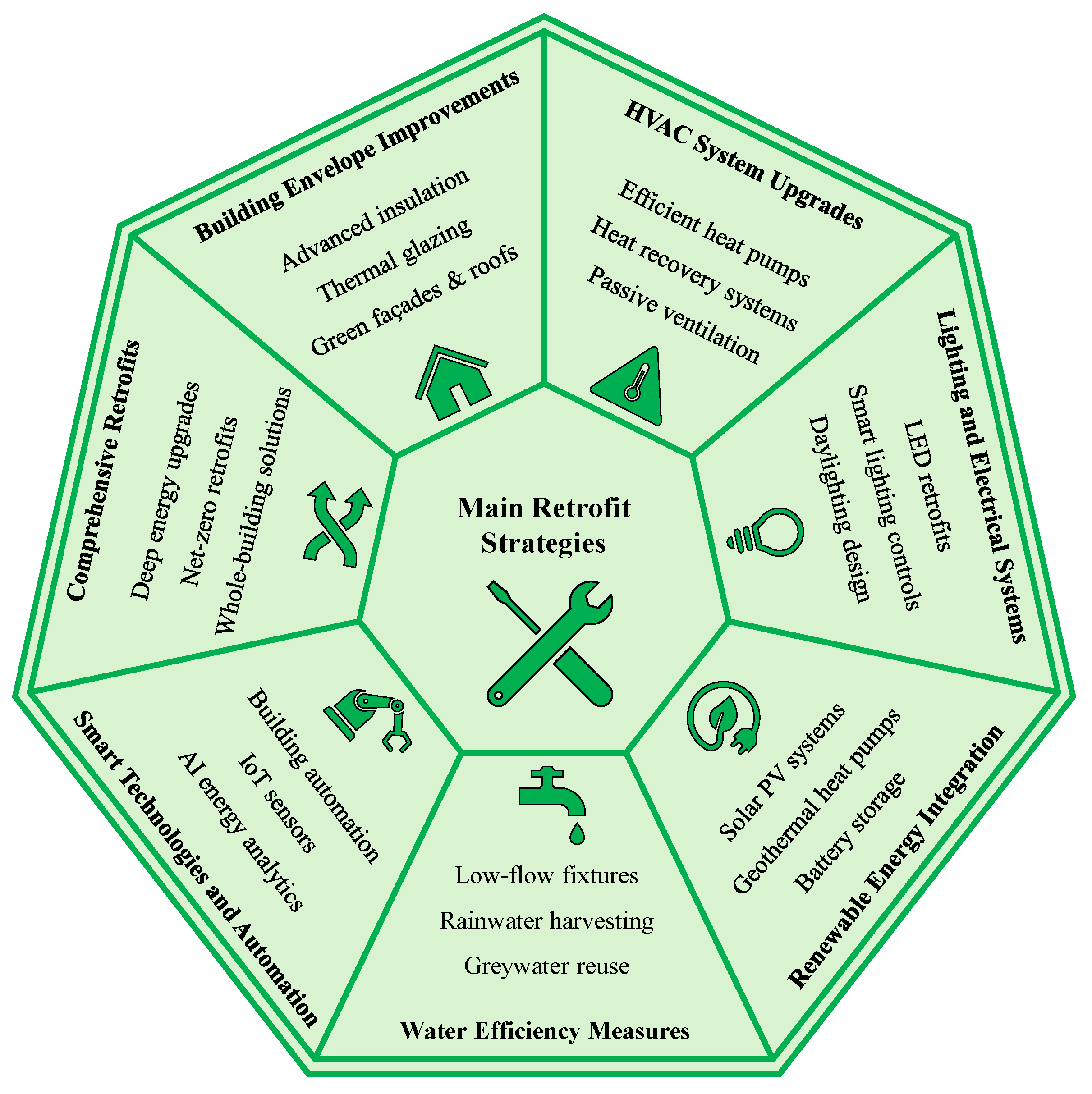

3.3.1. Key Building Retrofit Strategies

Building Envelope Improvements

HVAC System Upgrades

Lighting and Electrical Systems

Renewable Energy Integration

Water Efficiency Measures

Smart Technologies and Automation

Comprehensive Retrofits

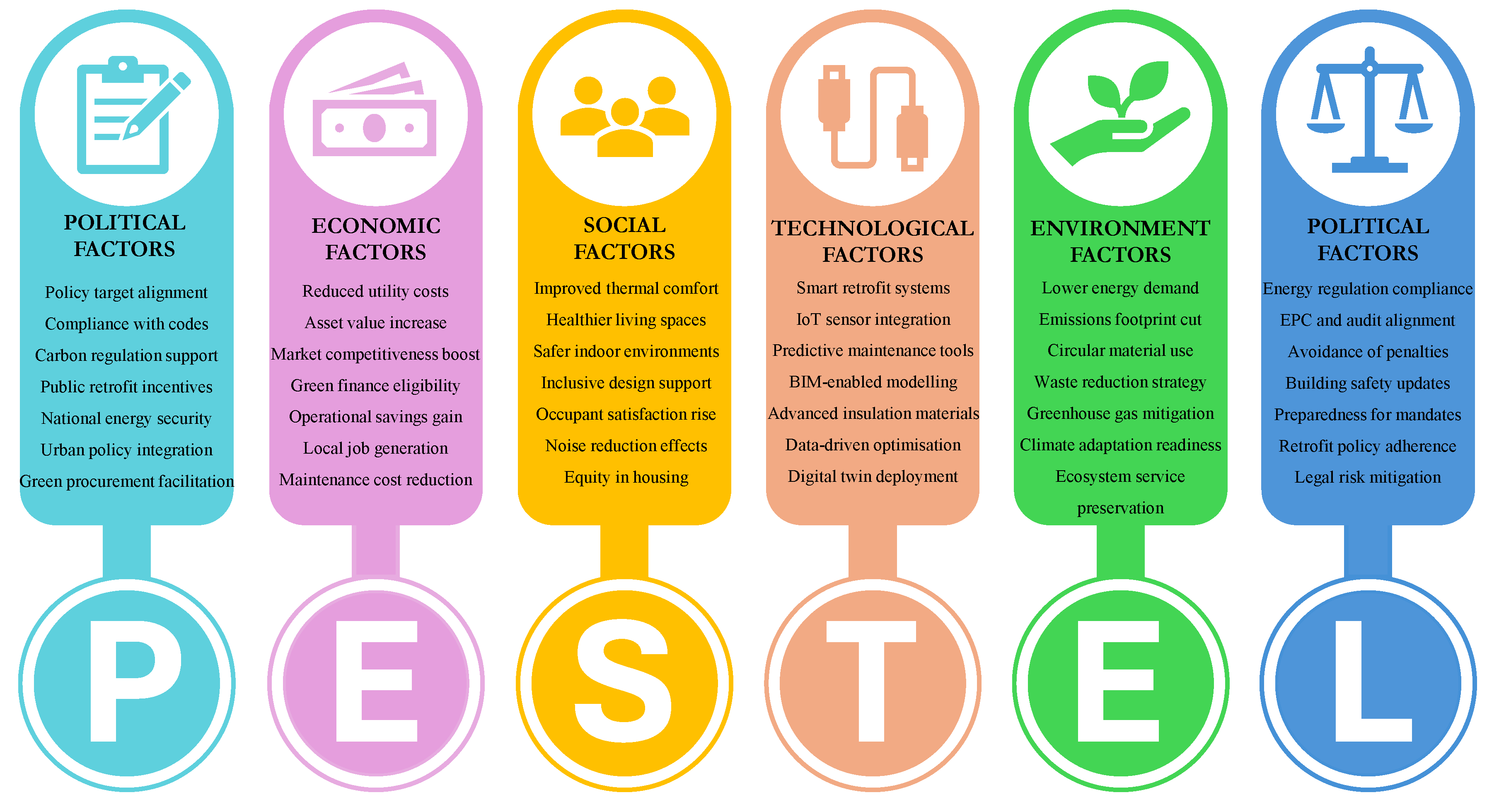

3.3.2. Benefits of Retrofit Strategies

Political Benefits

Economic Benefits

Social Benefits

Technological Benefits

Environmental Benefits

Legal Benefits

4. Discussions

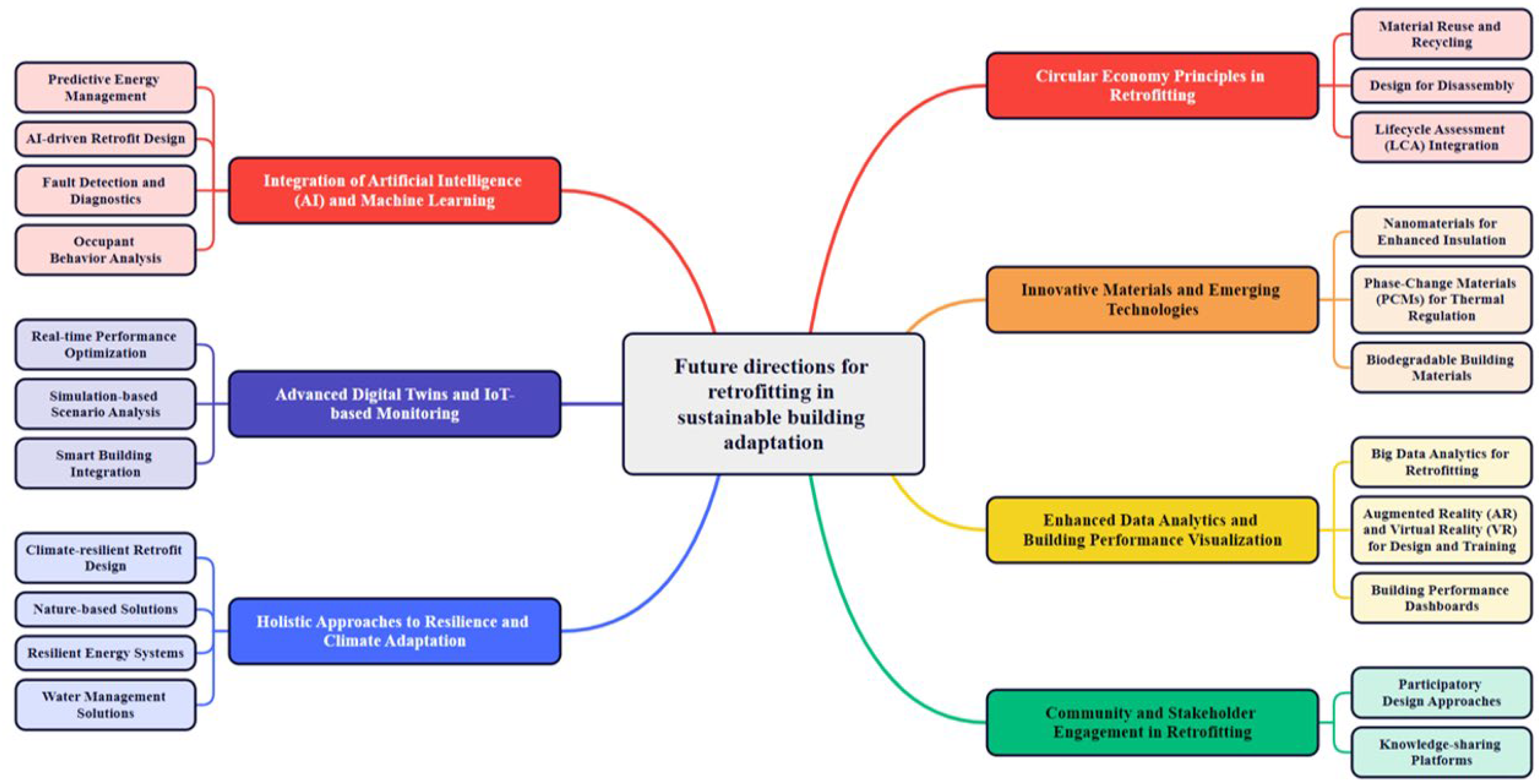

4.1. Future Directions for Retrofitting in Sustainable Building Adaptation

4.1.1. Integration of AI and ML

4.1.2. CE Principles in Retrofitting

4.1.3. Advanced DTs and IoT-Based Monitoring

4.1.4. Innovative Materials and Emerging Technologies

4.1.5. Holistic Approaches to Resilience and Climate Adaptation

4.1.6. Enhanced Data Analytics and Building Performance Visualisation

4.1.7. Community and Stakeholder Engagement in Retrofitting

5. Conclusions

- Research momentum: A marked rise in retrofit publications occurred after 2020, driven by climate targets, energy crises, and stricter decarbonisation policies.

- Focus areas: A majority of studies examined energy efficiency, building envelope upgrades, and digital tools, evidencing a shift from conventional retrofits to integrated, data-informed strategies.

- Mapped interventions: Content analysis identified key interventions, including envelope retrofits, HVAC optimisation, renewable energy integration, water-saving solutions, smart systems, and lifecycle performance enhancements.

- Thematic structure: VOSviewer revealed six clusters, such as envelope performance, economic assessment, environmental sustainability, system efficiency, passive design, and digital/data-driven planning, each confirming the field’s multidisciplinary character and alignment with sustainability goals.

- Broader implications (PESTEL analysis): Retrofitting supports policy compliance, economic resilience, social measures, technological adoption, environmental factors and legal adaptation, underscoring its systemic value.

- Future directions: Seven forward-looking pathways were identified, namely AI/ML, CE strategies, DTs and IoT, novel/advanced materials, climate resilience, user and community engagement, and advanced data visualisation/analytics.

- Contribution and audience: The review consolidates scattered knowledge and sets out a clear research agenda, informing academics, policymakers, and practitioners pursuing environmentally conscious, technologically advanced, and socially inclusive retrofit pathways.

- Overall significance: In the context of accelerating climate change and urban growth, retrofitting remains a cost-efficient and forward-looking solution for transforming cities into sustainable and resilient urban systems.

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs 68% of the World Population Projected to Live in Urban Areas by 2050, Says UN|United Nations. 2018. Available online: https://www.un.org/uk/desa/68-world-population-projected-live-urban-areas-2050-says-un (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- James, N. Urbanization and Its Impact on Environmental Sustainability. J. Appl. Geogr. Stud. 2024, 3, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Han, M.Y.; Liu, S.Y.; Chen, G.Q. Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Buildings: A Multi-Scale Perspective. Build. Environ. 2019, 151, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum Buildings Are the Foundation of Our Energy-Efficient Future|World Economic Forum. 2021. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2021/02/why-the-buildings-of-the-future-are-key-to-an-efficient-energy-ecosystem/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Cabeza, L.F.; Barreneche, C.; Miró, L.; Martínez, M.; Fernández, A.I.; Urge-Vorsatz, D. Affordable Construction Towards Sustainable Buildings: Review on Embodied Energy in Building Materials. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Soto, F.J.; Zarco-Soto, I.M.; Ali, S.S.S.; Zarco-Periñán, P.J. Energy Consumption in Buildings: A Compilation of Current Studies. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 1293–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, F.S.; Sa’di, B.; Safa-Gamal, M.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Alrifaey, M.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Stojcevski, A.; Horan, B.; Mekhilef, S. Energy Efficiency in Sustainable Buildings: A Systematic Review with Taxonomy, Challenges, Motivations, Methodological Aspects, Recommendations, and Pathways for Future Research. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2023, 45, 101013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citadini de Oliveira, C.; Catão Martins Vaz, I.; Ghisi, E. Retrofit Strategies to Improve Energy Efficiency in Buildings: An Integrative Review. Energy Build. 2024, 321, 114624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.; Santos, M.C.; Castro, R. Introductory Review of Energy Efficiency in Buildings Retrofits. Energies 2021, 14, 8100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Villegas, R.; Eriksson, O.; Olofsson, T. Assessment of Renovation Measures for a Dwelling Area—Impacts on Energy Efficiency and Building Certification. Build. Environ. 2016, 97, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, R.; Ana, F.; Luís, A.; Rui, C.N.; Laura, A.; and Silva, C. Retrofit Measures Evaluation Considering Thermal Comfort Using Building Energy Simulation: Two Lisbon Households. Adv. Build. Energy Res. 2021, 15, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduta, C.; Melica, G.; D’Agostino, D.; Bertoldi, P. Towards a Decarbonised Building Stock by 2050: The Meaning and the Role of Zero Emission Buildings (ZEBs) in Europe. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2022, 44, 101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. New Rules for Greener and Smarter Buildings Will Increase Quality of Life for All Europeans 2019. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/news-and-media/news/new-rules-greener-and-smarter-buildings-will-increase-quality-life-all-europeans-2019-04-15_en (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- European Commission. Questions and Answers on the Renovation Wave 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_20_1836 (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- United Nations Environment Programme. Here’s How Buildings Contribute to Climate Change—And What Can Be Done About It 2023. Available online: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/heres-how-buildings-contribute-climate-change-and-what-can-be-done-about-it (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- City of Melbourne Retrofit Case Studies—1200 Buildings Program|City of Melbourne 2021. Available online: https://www.c40.org/case-studies/city-of-melbourne-targets-building-sector-decarbonisation-through-1200-buildings-programme/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Duran, Ö.; Lomas, K.J. Retrofitting Post-War Office Buildings: Interventions for Energy Efficiency, Improved Comfort, Productivity and Cost Reduction. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 42, 102746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakalis, D.; Diaz Lozano Patino, E.; Opher, T.; Touchie, M.F.; Burrows, K.; MacLean, H.L.; Siegel, J.A. Quantifying Thermal Comfort and Carbon Savings from Energy-Retrofits in Social Housing. Energy Build. 2021, 241, 110950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauletbek, A.; Zhou, P. BIM-Based LCA as a Comprehensive Method for the Refurbishment of Existing Dwellings Considering Environmental Compatibility, Energy Efficiency, and Profitability: A Case Study in China. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 46, 103852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motalebi, M.; Rashidi, A.; Nasiri, M.M. Optimization and BIM-Based Lifecycle Assessment Integration for Energy Efficiency Retrofit of Buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 49, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Mo, Y.; Zhao, D. Energy Retrofits for Smart and Connected Communities: Scopes and Technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, S.; Lai, J.H.K.; Kumaraswamy, M.M.; Hou, H.C. Smart Retrofitting for Existing Buildings: State of the Art and Future Research Directions. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini Toosi, H.; Lavagna, M.; Leonforte, F.; Del Pero, C.; Aste, N. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment in Building Energy Retrofitting; A Review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 60, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature Review as a Research Methodology: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Sepasgozar, S.; Liu, T.; Yu, R. Integration of Bim and Immersive Technologies for Aec: A Scientometric-swot Analysis and Critical Content Review. Buildings 2021, 11, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, J.F. Scopus Database: A Review. Biomed. Digit. Libr. 2006, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I.; Čater, T. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lombard, L.; Ortiz, J.; Pout, C. A Review on Buildings Energy Consumption Information. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Amirkhani, M.; Martek, I. Overcoming Deterrents to Modular Construction in Affordable Housing: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholampour, M.; Taghipour, M.; Tahavvor, A.; Jafari, S. Retrofitting of Building with Double Skin Façade to Improve Indoor Air Quality, Thermal Comfort, and Infection Control in Inpatient Wards of a Hospital in a Semi-Hot-Arid Climate. Energy Build. 2025, 332, 115365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomrukcu, G.; Ashrafian, T. Climate-Resilient Building Energy Efficiency Retrofit: Evaluating Climate Change Impacts on Residential Buildings. Energy Build. 2024, 316, 114315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Lane, R.; Zhao, K.; Tham, S.; Woolfe, K.; Raven, R. Systematic Review: Landlords’ Willingness to Retrofit Energy Efficiency Improvements. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 303, 127041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afa, R.; Sobhy, I.; Brakez, A. Application of BIM-Driven BEM Methodologies for Enhancing Energy Efficiency in Retrofitting Projects in Morocco: A Socio-Technical Perspective. Buildings 2025, 15, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Utaberta, N.; Kiet, A.L.K.; Yanfang, X.; Xiyao, H. Effects of Green Façade Retrofitting on Thermal Performance and Energy Efficiency of Existing Buildings in Northern China: An Experimental Study. Energy Build. 2025, 335, 115550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, A.; Salvalai, G.; Imperadori, M.; Sesana, M.M. Nearly Zero Energy Building Renovation: From Energy Efficiency to Environmental Efficiency, a Pilot Case Study. Energy Build. 2018, 166, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pungercar, V.; Zhan, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Musso, F.; Dinkel, A.; Pflug, T. A New Retrofitting Strategy for the Improvement of Indoor Environment Quality and Energy Efficiency in Residential Buildings in Temperate Climate Using Prefabricated Elements. Energy Build. 2021, 241, 110951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevim, Y.E.; Taki, A.; Abuzeinab, A. Examining Energy Efficiency and Retrofit in Historic Buildings in the UK. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shen, H.; Deng, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, D. Measured Performance of Energy Efficiency Measures for Zero-Energy Retrofitting in Residential Buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91, 109545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coggins, A.M.; Wemken, N.; Mishra, A.K.; Sharkey, M.; Horgan, L.; Cowie, H.; Bourdin, E.; McIntyre, B. Indoor Air Quality, Thermal Comfort and Ventilation in Deep Energy Retrofitted Irish Dwellings. Build. Environ. 2022, 219, 109236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krarti, M. Evaluation of Large Scale Building Energy Efficiency Retrofit Program in Kuwait. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapfumo, E.T.; Emuze, F.; Smallwood, J.; Ebekozien, A. Appraising Challenges Facing Zimbabwe’s Building Retrofitting for Energy Efficiency Using Structural Equation Model Approach. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2024, 42, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Goel, S.; Lenka, S.R.; Satpathy, P.R. Energy Efficiency Retrofitting Measures of an Institutional Building: A Case Study in Eastern India. Clean. Energy Syst. 2024, 7, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, P.H.; Shaikh, F.; Sahito, A.A.; Uqaili, M.A.; Umrani, Z. Chapter 9—An Overview of the Challenges for Cost-Effective and Energy-Efficient Retrofits of the Existing Building Stock. In Cost-Effective Energy Efficient Building Retrofitting; Pacheco-Torgal, F., Granqvist, C.-G., Jelle, B.P., Vanoli, G.P., Bianco, N., Kurnitski, J., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 257–278. ISBN 978-0-08-101128-7. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, X.; Shen, Z.; Tutuko, D.C.S. Evaluating the Impact of Insulation Materials on Energy Efficiency Using BIM-Based Simulation for Existing Building Retrofits: Case Study of an Apartment Building in Kanazawa, Japan. Buildings 2025, 15, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, I.; Sridarran, P.; Abeynayake, M.; Jayakodi, S. Enhancing Building Performance of Post-Fire Refurbished Apparel Manufacturing Buildings in Sri Lanka. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2023, 13, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, N.W.; Zaki, S.A.; Hagishima, A.; Rijal, H.B.; Yakub, F. Affordable Retrofitting Methods to Achieve Thermal Comfort for a Terrace House in Malaysia with a Hot–Humid Climate. Energy Build. 2020, 223, 110072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Yun, B.Y.; Chang, S.J.; Wi, S.; Jeon, J.; Kim, S. Impact of a Passive Retrofit Shading System on Educational Building to Improve Thermal Comfort and Energy Consumption. Energy Build. 2020, 216, 109930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Darwish, I.; Gomaa, M. Retrofitting Strategy for Building Envelopes to Achieve Energy Efficiency. Alex. Eng. J. 2017, 56, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Jin, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, Q.; Li, D. Passive Nearly Zero Energy Retrofits of Rammed Earth Rural Residential Buildings Based on Energy Efficiency and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 180, 113300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandilya, A.; Hauer, M.; Streicher, W. Optimization of Thermal Behavior and Energy Efficiency of a Residential House Using Energy Retrofitting in Different Climates. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2020, 8, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alla, S.A.; Bianco, V.; Scarpa, F.; Tagliafico, L.A. Retrofitting for Improving Energy Efficiency: The Embodied Energy Relevance for Buildings’ Thermal Insulation. J. Eng. Sustain. Build. Cities 2021, 2, 24501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, M.; Shen, P.; Cui, X.; Bu, L.; Wei, R.; Zhang, L.; Wu, C. Energy Saving and Thermal Comfort Performance of Passive Retrofitting Measures for Traditional Rammed Earth House in Lingnan, China. Buildings 2022, 12, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherzadeh, H.; Malekghasemi, A.; McArthur, J.J. Retrofitting for the Future: Analysing the Sensitivity of Various Retrofits to Future Climate Scenarios While Maintaining Thermal Comfort. Energy Build. 2025, 327, 115004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoruso, F.M.; Dietrich, U.; Schuetze, T. Indoor Thermal Comfort Improvement through the Integrated BIM-Parametricworkflow-Based Sustainable Renovation of an Exemplary Apartment in Seoul, Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excell, L.E.; Nutkiewicz, A.; Jain, R.K. Multi-Scale Retrofit Pathways for Improving Building Performance and Energy Equity across Cities: A UBEM Framework. Energy Build. 2024, 324, 114931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves-Silva, R.; Camarinha-Matos, L.M. Simulation-Based Decision Support System for Energy Efficiency in Buildings Retrofitting. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillone, B.; Danov, S.; Sumper, A.; Cipriano, J.; Mor, G. A Review of Deterministic and Data-Driven Methods to Quantify Energy Efficiency Savings and to Predict Retrofitting Scenarios in Buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 110027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, D.; Cooper, P.; Ma, Z. Qualitative Analysis of the Use of Building Performance Simulation for Retrofitting Lower Quality Office Buildings in Australia. Energy Build. 2018, 181, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Feng, H.; Hewage, K.; Arashpour, M. Artificial Neural Network for Predicting Building Energy Performance: A Surrogate Energy Retrofits Decision Support Framework. Buildings 2022, 12, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; Ye, S.; Liu, Y. Cost-Benefit Analysis for Energy Efficiency Retrofit of Existing Buildings: A Case Study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M. An Evaluation of the Retrofit Net Zero Building Performances: Life Cycle Energy, Emissions and Cost. Build. Res. Inf. 2023, 51, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushar, Q.; Zhang, G.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Giustozzi, F.; Navaratnam, S.; Hou, L. An Optimized Solution for Retrofitting Building Façades: Energy Efficiency and Cost-Benefit Analysis from a Life Cycle Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeley, C.C.; Dhakal, S. Energy Efficiency Retrofits in Commercial Buildings: An Environmental, Financial, and Technical Analysis of Case Studies in Thailand. Energies 2021, 14, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, R.Y.J. Financing Options for Energy Efficiency Retrofit Projects—A Malaysian Perception. Malays. Constr. Res. J. 2018, 24, 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Ma, J.; Song, K. Homeowners’ Willingness to Make Investment in Energy Efficiency Retrofit of Residential Buildings in China and Its Influencing Factors. Energies 2021, 14, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Xia, X. Energy-Efficiency Building Retrofit Planning for Green Building Compliance. Build. Environ. 2018, 136, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviste, M.; Musakka, S.; Ruus, A.; Vinha, J. A Review of Non-Residential Building Renovation and Improvement of Energy Efficiency: Office Buildings in Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Germany. Energies 2023, 16, 4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liao, N.; Bi, J.; Guo, L. Investment Decision-Making Optimization of Energy Efficiency Retrofit Measures in Multiple Buildings Under Financing Budgetary Restraint. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1078–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, F.; Porras Amores, C. Simulation-Based Multi-Objective Optimization for Building Retrofits in Iran: Addressing Energy Consumption, Emissions, Comfort, and Indoor Air Quality Considering Climate Change. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Wang, C.; Li, B.; Li, B.; Du, C. Professional Barriers in Energy Efficiency Retrofits—A Solution Based on Information Flow Modeling. Buildings 2025, 15, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, W.; Tso, C.Y.; Sun, L.; Ip, D.; Lee, H.; Chao, C.; Lau, A. Energy Consumption, Indoor Thermal Comfort and Air Quality in a Commercial Office with Retrofitted Heat, Ventilation and Air Conditioning (HVAC) System. Energy Build. 2019, 201, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, W.; Mainka, A.; Brągoszewska, E. Impact of Ventilation System Retrofitting on Indoor Air Quality in a Single-Family Building. Build. Environ. 2024, 262, 111830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, B.; Xia, X. Large-Scale Building Energy Efficiency Retrofit: Concept, Model and Control. Energy 2016, 109, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, R.; Chen, P. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Approach for Energy-Efficient Renovation Strategies in Hospital Wards: Balancing Energy, Economic, and Thermal Comfort. Energy Build. 2023, 298, 113575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, F.; Palaniappan, K.; Pillay, M.; Ershadi, M. A Scoping Review of Indoor Air Quality Assessment in Refurbished Buildings. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2025, 14, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarsini, R.; Jin, W.; Myla, A.M. An Investigation of an Affordable Ventilation Retrofit to Improve the Indoor Air Quality in Australian Aged Care Homes. J. Archit. Eng. 2024, 30, 4024019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Ruchansky, L.; Pérez-Fargallo, A. Integrated Analysis of Energy Saving and Thermal Comfort of Retrofits in Social Housing Under Climate Change Influence in Uruguay. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, H. Analysis of Building Retrofit, Ventilation, and Filtration Measures for Indoor Air Quality in a Real School Context: A Case Study in Korea. Buildings 2023, 13, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, J.; Ahmed, V.; Saboor, S. An Investigation of Barriers and Enablers to Energy Efficiency Retrofitting of Social Housing in London. Constr. Econ. Build. 2020, 20, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rababa, W.; Asfour, O.S. Façade Retrofit Strategies for Energy Efficiency Improvement Considering the Hot Climatic Conditions of Saudi Arabia. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung-Camargo, K.; González, J.; Chen Austin, M.; Carpino, C.; Mora, D.; Arcuri, N. Advances in Retrofitting Strategies for Energy Efficiency in Tropical Climates: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Buildings 2024, 14, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, G.; Pereira, I.; Leitão, A.; Correia Guedes, M. Conflicts in Passive Building Performance: Retrofit and Regulation of Informal Neighbourhoods. Front. Archit. Res. 2021, 10, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaly, L.G.; Hashemi, A.; Elsharkawy, H.; Newport, D.; Badawy, N.M. Effects of Retrofit Strategies on Thermal Comfort and Energy Performance in Social Housing for Current and Future Weather Scenarios. Buildings 2025, 15, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunoro, S. Passive Envelope Measures for Improving Energy Efficiency in the Energy Retrofit of Buildings in Italy. Buildings 2024, 14, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, P.; O’Connell, J.; Goggins, J. Sustainable Energy Efficiency Retrofits as Residenial Buildings Move towards Nearly Zero Energy Building (NZEB) Standards. Energy Build. 2020, 211, 109816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranđelović, D.; Jovanović, V.; Ignjatović, M.; Marchwiński, J.; Kopyłow, O.; Milošević, V. Improving Energy Efficiency of School Buildings: A Case Study of Thermal Insulation and Window Replacement Using Cost-Benefit Analysis and Energy Simulations. Energies 2024, 17, 6176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.; McLaren, S.J.; Dowdell, D.; Phipps, R. Environmental Assessment of Deep Energy Refurbishment for Energy Efficiency-Case Study of an Office Building in New Zealand. Build. Environ. 2017, 117, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Absi, Z.A.; Hafizal, M.I.M.; Ismail, M.; Ghazali, A. Towards Sustainable Development: Building’s Retrofitting with Pcms to Enhance the Indoor Thermal Comfort in Tropical Climate, Malaysia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama Radha, C. Retrofitting for Improving Indoor Air Quality and Energy Efficiency in the Hospital Building. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Nam, S.H. IEQ and Energy Effect Analysis According to Empirical Full Energy Efficiency Retrofit in South Korea. Energy Build. 2021, 235, 110629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, U.K.; Senthil, R. Enhancing Sustainable Urban Planning to Mitigate Urban Heat Island Effects Through Residential Greening. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 129, 106512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.B.; Warsinger, D.M. Energy Savings of Retrofitting Residential Buildings with Variable Air Volume Systems Across Different Climates. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 30, 101223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, D.R.; Pruckner, M. Data-Driven Heat Pump Retrofit Analysis in Residential Buildings: Carbon Emission Reductions and Economic Viability. Appl. Energy 2024, 373, 123823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikola, A.; Hamburg, A.; Kuusk, K.; Kalamees, T.; Voll, H.; Kurnitski, J. The Impact of the Technical Requirements of the Renovation Grant on the Ventilation and Indoor Air Quality in Apartment Buildings. Build. Environ. 2022, 210, 108698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajiga, O.; Ani, E.; Sikhakane, Z.; Olatunde, T. A Comprehensive Review of Energy-Efficient Lighting Technologies and Trends. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 1097–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booysen, M.J.; Samuels, J.A.; Grobbelaar, S.S. LED There Be Light: The Impact of Replacing Lights at Schools in South Africa. Energy Build. 2021, 235, 110736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedolhosseini, A.; Masoumi, N.; Modarressi, M.; Karimian, N. Daylight Adaptive Smart Indoor Lighting Control Method Using Artificial Neural Networks. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 29, 101141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scartezzini, J.-L. Advances in Daylighting and Artificial Lighting. In Research in Building Physics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 11–18. ISBN 9781003078852. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.S.; Matusiak, B.S.; Geisler-Moroder, D.; Selkowitz, S.E.; Heschong, L. Advocating for View and Daylight in Buildings: Next Steps. Energy Build. 2022, 265, 112079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwame, A.B.O.; Troy, N.V.; Hamidreza, N. A Multi-Facet Retrofit Approach to Improve Energy Efficiency of Existing Class of Single-Family Residential Buildings in Hot-Humid Climate Zones. Energies 2020, 13, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, R.S.; Fung, A.S.; Dash, P.R.H. Solar Systems and Their Integration with Heat Pumps: A Review. Energy Build. 2015, 87, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, T.; Wu, W.; Yang, H.; Liu, J.; Li, X. Hybrid Photovoltaic/Thermal and Ground Source Heat Pump: Review and Perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasinghe, L.N.K.; Darko, A.; Chan, A.P.C.; Blay, K.B.; Edwards, D.J. Measures, Benefits, and Challenges to Retrofitting Existing Buildings to Net Zero Carbon: A Comprehensive Review. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 94, 109998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Zavala, M.Á.; Castillo Vega, R.; López Miranda, R.A. Potential of Rainwater Harvesting and Greywater Reuse for Water Consumption Reduction and Wastewater Minimization. Water 2016, 8, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.; Curtis, J. An Examination of Energy Efficiency Retrofit Depth in Ireland. Energy Build. 2016, 127, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccardo, C.; Gustavsson, L. Deep Energy Retrofits Using Different Retrofit Materials Under Different Scenarios: Life Cycle Cost and Primary Energy Implications. Energy 2023, 281, 128131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsatti, F.; Cuzzocrea, C.M.; De Poli, A.; Locatelli, G. Towards Net-Zero: Success Factors of Tertiary Building Energy Efficiency Retrofitting Projects. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 103, 112087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Le, C.; Wenting, Z. PESTEL Analysis of Construction Productivity Enhancement Strategies: A Case Study of Three Economies. J. Manag. Eng. 2019, 35, 5018013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Zhao, K.; Lane, R.; Raven, R. Pro-Social Concerns Characterise Landlords’ Energy Efficiency Retrofit Behaviour: Evidence and Implications for Energy Efficiency Policy in Victoria, Australia. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2025, 25, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olasolo-Alonso, P.; López-Ochoa, L.M.; Las-Heras-Casas, J.; López-González, L.M. Energy Performance of Buildings Directive Implementation in Southern European Countries: A Review. Energy Build. 2023, 281, 112751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Kumar, A.; Pipralia, S.; Garg, P. Initiatives to Achieve Energy Efficiency for Residential Buildings in India: A Review. Indoor Built Environ. 2018, 28, 1420326X1879738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkos, P.; van de Ven, D.-J.; Horowitz, R.; Zisarou, E. Analysing the Transformative Changes of Nationally Determined Contributions and Long-Term Targets. Climate 2024, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, A.; Romano, R.; Gallo, P. Building Performance Assessment of a Retrofitted Case Study in Florence. Lessons Learned from Current Practices. Int. J. Sustain. Build. Technol. Urban Dev. 2022, 13, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, V.; Ruggiero, S.; Riccardi, S.; Assimakopoulos, M.-N.; Papadaki, D. Incidence of Circular Refurbishment Measures on Indoor Air Quality and Comfort Conditions in Two Real Buildings: Experimental and Numerical Analysis. Energy Built Environ. 2024, 6, 809–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, F.; Carpino, C.; Barbosa, G.; Domenico, A.; Arcuri, N.; Almeida, M. Building Renovation Passport: A New Methodology for Scheduling and Addressing Financial Challenges for Low-Income Households. Energy Build. 2025, 331, 115353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, G.; Almeida, M. Strategies for Implementing and Scaling Renovation Passports: A Systematic Review of EU Energy Renovation Policies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S. Hybrid Predictive Maintenance for Building Systems: Integrating Rule-Based and Machine Learning Models for Fault Detection Using a High-Resolution Danish Dataset. Buildings 2025, 15, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, S.; Samarakoon, S.M.S.M.K.; Haq, M.A.A. Use of Circular Economy Practices During the Renovation of Old Buildings in Developing Countries. Sustain. Futur. 2023, 6, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetteh, M.O.; Boateng, E.B.; Darko, A.; Chan, A.P.C. What Are the General Public’s Needs, Concerns and Views about Energy Efficiency Retrofitting of Existing Building Stock? A Sentiment Analysis of Social Media Data. Energy Build. 2023, 301, 113721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewagoda, K.; Ng, S.; Kumaraswamy, M.; Chen, J. Design for Circular Manufacturing and Assembly (DfCMA): Synergising Circularity and Modularity in the Building Construction Industry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minerva, R.; Lee, G.M.; Crespi, N. Digital Twin in the IoT Context: A Survey on Technical Features, Scenarios, and Architectural Models. Proc. IEEE 2020, 108, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzón, M.; López-Mesa, B. Buildings Performance Indicators to Prioritise Multi-Family Housing Renovations. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozi, A.A.; Firoozi, A.A.; Oyejobi, D.O.; Avudaiappan, S.; Flores, E.S. Emerging Trends in Sustainable Building Materials: Technological Innovations, Enhanced Performance, and Future Directions. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. Chapter 14—Thermal Insulating Lightweight Aerogels Based on Nanocellulose. In Advances in Bio-Based Materials for Construction and Energy Efficiency; Pacheco-Torgal, F., Tsang, D.C.W., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2025; pp. 367–394. ISBN 978-0-443-32800-8. [Google Scholar]

- Berardi, U. Aerogel-Enhanced Systems for Building Energy Retrofits: Insights from a Case Study. Energy Build. 2018, 159, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q. Utilizing Mycelium-Based Materials for Sustainable Construction. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2024, 63, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamy, A.; Abu Bakar, A.H. Developing a Building-Performance Evaluation Framework for Post-Disaster Reconstruction: The Case of Hospital Buildings in Aceh, Indonesia. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2021, 21, 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, U.; Bano, S.; Shamsi, M.H.; Sood, D.; Hoare, C.; Zuo, W.; Hewitt, N.; O’Donnell, J. Urban Building Energy Performance Prediction and Retrofit Analysis Using Data-Driven Machine Learning Approach. Energy Build. 2024, 303, 113768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, M.; Ruschel, R. Augmented Reality Supporting Building Assesment in Terms of Retrofit Detection. In Proceedings of the CIB W078 International Conference, Beijing, China, 9–12 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bhonde, D.; Zadeh, P.; Staub-French, S. Evaluating the Use of Virtual Reality for Maintainability-Focused Design Reviews. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2022, 27, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubachukwu, E.; Pick, J.; Riebesel, L.; Lieberenz, P.; Althaus, P.; Xhonneux, A.; Müller, D. User Engagement for Thermal Energy-Efficient Behavior in Office Buildings Using Dashboards and Gamification. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 266, 125598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudi Nia, E.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J. Analysis of Occupant Behaviours in Energy Efficiency Retrofitting Projects. Land 2022, 11, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subsection | Focus Area | Key Tools/Technologies | Example Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital and simulation-based approaches | Performance simulation, digital modelling, pre-retrofit assessment | BIM, DTs, EnergyPlus, DesignBuilder, AI, Decision support system | [19,34,39,45,69,86] |

| Renewable energy integration | Clean energy integration to reduce grid dependence | Solar PV, Heat pumps, Solar thermal, Hybrid systems | [36,48,49,63,79,87] |

| Advanced materials and insulation | High-efficiency insulation and thermal comfort materials | Aerogels, PCMs, VIPs, Smart Glazing | [32,35,47,50,71,81] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martek, I.; Amirkhani, M.; Khan, A.A. Retrofitting for Sustainable Building Performance: A Scientometric–PESTEL Analysis and Critical Content Review. Buildings 2025, 15, 4106. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224106

Martek I, Amirkhani M, Khan AA. Retrofitting for Sustainable Building Performance: A Scientometric–PESTEL Analysis and Critical Content Review. Buildings. 2025; 15(22):4106. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224106

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartek, Igor, Mehdi Amirkhani, and Ayaz Ahmad Khan. 2025. "Retrofitting for Sustainable Building Performance: A Scientometric–PESTEL Analysis and Critical Content Review" Buildings 15, no. 22: 4106. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224106

APA StyleMartek, I., Amirkhani, M., & Khan, A. A. (2025). Retrofitting for Sustainable Building Performance: A Scientometric–PESTEL Analysis and Critical Content Review. Buildings, 15(22), 4106. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224106