Abstract

Wood is a renewable and sustainable environmentally friendly building material. With proper design, it can help buildings achieve lower carbon emissions. However, since wood is a flammable material, its combustion performance in fires has attracted attention. In modern timber structures, glulam is a widely used engineered wood product. Thus, in this paper, glulam specimens made of four kinds of commonly used soft-wood species were used to compare their combustion performance, and the cone calorimeter method was employed. The indicators including time to ignition, heat release rate per unit area, total heat release per unit area, specific extinction area per unit mass, mass of residue, yield of CO and yield of CO2 were evaluated and compared. The results showed that all the glulam specimens would experience cracking wood and adhesive layer. The time to ignition and peak mass loss rate of the four softwood species in the study was positively correlated with their density. Among these species, Spruce exhibited the highest peak heat release rate and the highest peak CO2 yield but lowest smoke production, while Douglas fir had a relatively late CO production time and the lowest mass loss percentage, Larch had the lowest heat release rate and total heat release. This study provides fundamental data for the selection of wood structural materials and for future research on wood flame-retardant treatments.

1. Introduction

Wood is a kind of green, renewable, and sustainable building material, whose carbon emission throughout the entire life cycle would be far less than that of conventional building materials such as steel and concrete, if they were under effective design [1]. Softwood species have advantages such as a high strength-to-weight ratio, ease of processing, and a short growth cycle, and have been widely used as a structural material for timber structures. The dimension softwood solid wood is usually employed as wall studs and joists in light timber structures, while also used to manufacture engineered wood products (EWPs) such as glulam and cross-laminated timber (CLT) in mass timber structures [2]. In building design, fire resistance of structures is of vital importance as it is directly related to life safety. However, the combustibility of wood is regarded as one of the primary safety challenges in architectural applications.

When wood is exposed to high temperatures (of approximately 100 °C), the evaporation of absorbed water within the wood is accelerated. Subsequently, within the temperature range of 180 to about 300 °C, it undergoes a process of dehydration and pyrolysis, and finally, the various components of the wood undergo thermal decomposition [3]. Thus, the combustion properties of wood have attracted increasing attention from scholars. For example, Baysal et al. [4] carried out an experimental study on the fire performance of Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menzieesi) rectangular specimens, which evaluated the fire resistance of Douglas fir treated with borates and natural extracts. Results demonstrated that a boric acid (BA) and borax (BX) mixture was superior, yielding the lowest combustion temperatures and mass loss. In contrast, treatments using natural powders such as pine bark or gall-nut did not enhance fire resistance. Martinka et al. [5] evaluated the influence of Norway Spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) form on the activation energy of spontaneous ignition. And they also investigated the relationship between the heat flux values of the specimens and the risk of fire. Zacher et al. [6] assessed the fire resistance of aged oak wood (Quercus robur L.) of 0, 10, 40, 80, and 120 years. The combustion properties, such as activation energies, ignition temperatures, and mass burning rates, were analyzed. Results showed that the oldest wood had the highest content of carbon and the lowest proportion of nitrogen, sulfur, and phosphorus, and the thermal resistance of the oldest specimens was the poorest because of the different chemical compositions. Similarly, Jing et al. [7] conducted an experimental and analytical study on the fire performance of old (200–300 years) cypress, pine, and fir wood, along with the new ones. Terzi et al. [8] investigated the fire performance, such as mass loss, heat release rate, time for sustained ignition, effective heat of combustion, and specific extinction area of untreated/fire retardants treated Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) through fire tube test and cone calorimeter test. Yue et al. [9] evaluate the combustion and mechanical performance of boric phenol formaldehyde resin-treated Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) specimens, while the results showed that the mechanical and combustion properties of treated specimens were improved at high temperature.

In mass timber structures, the EWPs are the main structural components that are responsible for transferring loads [10] and also constitute the primary building envelope and serve as internal partitions [11]. Therefore, the combustion performance of EWPs such as glulam was important for the overall safety of mass timber structures. For instance, Yang et al. [12] carried out a cone calorimeter test to investigate the combustion performance of glulam made of five softwood species. Results showed that the average heat release rate and the total heat release of Taiwania (Taiwania cryptomerioides) were the highest, while those of Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) were the lowest. Tsai et al. [13] studied the charring rates of single and double timber beams made of laminated veneer lumber (LVL) with different connecting methods (nailed, screwed, and glued joints). It found that the glue-connected beam had the best fire performance, which exhibited similar behavior to a solid timber beam. Kucikova et al. [14] conducted an experimental and numerical investigation on the fire performance of a glulam beam, and the results from the numerical simulation and the conventional heat transfer model were compared. Suzuki et al. [15] put CLT and LVL panels into standard fire exposure, and the charring characteristics and failure modes were investigated. The parameters of specimens were compared, and finally, a prediction method was proposed. Li et al. [16] examined the fire performance of glulam columns made of six wood species, including Poplar (Populus tomentosa), Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii), Hemlock (Tsuga chinensis), Larch (Larix gmelinii), and Spruce (Picea asperata). Results demonstrated that the higher density of wood could obtain lower charring and heat penetration rates.

In this paper, glulam made of four kinds of commonly used softwood species in timber structures: Spruce (Picea asperata), Larch (Larix gmelinii), Mongolian Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica), and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii) were processed into specimens, and the cone calorimeter method was employed to evaluate the combustion performance of such timber specimens. The main objective of this study was to evaluate and compare the combustion performance of several commonly used softwood species in glulam. By experimentally determining parameters such as ignition time, heat release rate, and so on, it aimed to provide direct and reliable experimental evidence for enhancing the fire safety level of timber structures and for the subsequent development of targeted fire-retardant treatment technologies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Four kinds of softwood glulam species used in this study were bought from Jiangsu Desong Wood Industry Co., Ltd., Zhangjiagang, Jiangsu province, China. The one-component polyurethane (PUR) liquid adhesive (moisture-curing at room temperature) was applied to manufacture the specimens, with an amount of 200 g/m2 and under the pressure of 1 MPa for 3 h. The grain direction of each lamination was consistent during the lay-up process. Since the PUR is a cold-curing adhesive, the specimens were placed at room temperature (23 °C) to allow the adhesive to cure. The detailed density and moisture content of each species are shown in Table 1. The test specimens in each group were processed into a cuboid with a size of 95 mm (length) × 95 mm (width) × 50 mm (thickness), with a lamination thickness of (30 ± 2) mm and 2 adhesive layers; each group had three replications.

Table 1.

Grouping of test specimens.

2.2. Methods

According to ISO5660-1 [17] the cone calorimeter method was used to conduct tests. The test machine is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Combustion test machine.

The radiation heat flux was set as 50 kW/m2, and each specimen was burned for around 70 min. The combustion properties including time to ignition (TTI, s), heat release rate per unit area (HRR, kW/m2), total heat release per unit area (THR, MJ/m2), specific extinction area per unit mass (SEA, m2/kg), mass of residue (MOR, g), yield of CO (YCO, g/s) and yield of CO2 (, g/s) were evaluated and compared.

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Failure Mode

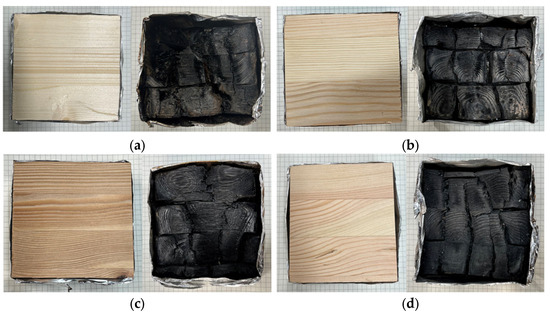

The images of four kinds of softwood species in each group are shown in Figure 2. As can be seen from the figure, each specimen exhibited charring. Due to prolonged exposure to flames, the thickness of each specimen decreased (the residual mass of the specimens was reduced). Cracking of varying degrees occurred in all groups of specimens, mainly manifested as cracking in the adhesive layers of the glulam and fractures within the same lamination. The latter is likely due to: (1) during the initial stage of combustion, the evaporation of moisture and some volatile organic compounds from the wood during thermal decomposition, which may have caused the wood to shrink and develop cracks, and (2) in the later stage of combustion, the breakdown of the cellulose and lignin network structure, replaced by a porous, loose carbon skeleton structure, making the wood brittle. The char layer started forming before the heat release rate suddenly decreased, which isolated the oxygen from the wood and led to the reduction in heat release rate. However, heat continued to transfer into the specimen during this period. At approximately 1000 s to 1500 s, noticeable cracking of the adhesive layer was observed, followed by a slight increase in the heat release rate, indicating that heat was penetrating the specimen interior through the cracks in the adhesive layer.

Figure 2.

Images of specimens before and after combustion: (a) Spruce; (b) Mongolian Scots pine; (c) Douglas fir; and (d) Larch.

In this study, as the bonding line was directly exposed to fire, the increase in surface temperature and formation of a charring layer occurred rapidly [12], which had a greater impact on the performance of the adhesive layer. During the initial stage of combustion, the adhesive layer deteriorated under heat but had not yet fully decomposed, and its bonding strength began to decline. As the combustion continues, the adhesive layer undergoes significant deterioration, and its mechanical strength decreases rapidly. Moreover, previous studies have found that the deterioration of the adhesive layer and the detachment of the char layer expose the intact interior wood to the flames, leading to the progression of the char layer deeper into the glulam [18]. As Muszynski et al. [19] found that the deflection of cross-laminated timber (CLT) using PUR adhesive in assembly would increase rapidly in the later stage of combustion, indicating that the performance of PUR degraded rapidly under high temperatures as the combustion progressed. Meanwhile, the cracking of the surface bonding line would cause the temperature inside the crack to continue rising, thereby leading to further cracking of the adhesive layer. Additionally, with the temperature continuing to increase, the charring layer would undergo separation (which results from material expansion or altered physical properties at elevated temperatures), leading to exposure to heat and oxygen for wood [20] a new cycle of charring layer formation and detachment is formed.

3.2. Combustion Properties

The main combustion properties of four softwood species are shown in Table 2. The time to ignition (TTI) reflects the ease with which a material can be ignited. The TTI of Spruce was the shortest (30.6 s), while that of Larch was the longest (47.6 s). In addition, Larch specimens had the highest peak mass loss rate, which indicated that their combustion rate was the fastest, and the mass of the residue decreased more rapidly. Douglas fir had the highest peak effective combustion heat, while Larch had the lowest, even though it had the highest mass loss rate. In terms of the peak heat release rate, Spruce and Douglas fir had the higher rate, while Larch exhibited the slowest.

Table 2.

Main indicators of specimens in the combustion test.

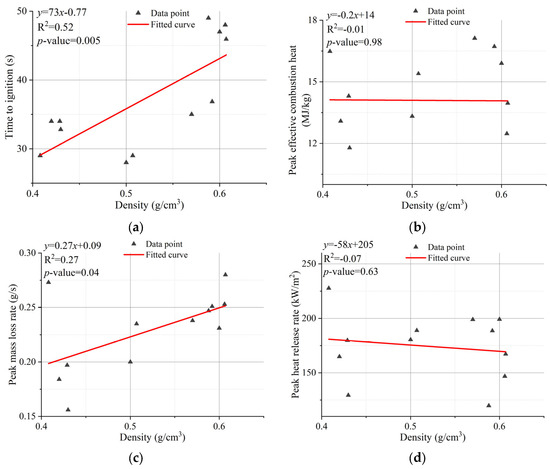

In order to investigate whether the main combustion properties were related to the density of these four softwood species, linear regression was conducted on the four performance indicators in Table 2 and the density; the results are shown in Figure 3. Among these four indicators, the relationship between density and TTI/peak mass loss rate (PMLR) appears to be stronger (Figure 3a,c). The R2 of TTI-density was 0.52, while the p-value was 0.005 (at 95% confidence level), indicating a significant correlation between TTI and density. Previous study showed that the TTI of hardwood was positively correlated with its density, while this correlation was not significant for softwood species [21], in this study, a positive correlation between TTI and density of these four kinds of softwood species has been found. Furthermore, the p-value of PMLR-density was 0.04, even though the R2 was only 0.27. This indicated that there was a positive correlation between the peak mass loss rate and density, as the density of softwood increased, a faster mass loss rate could be obtained. The other three properties seemed to show no obvious correlation between density and them. However, no significant correlation was found between the other indicators and density in this study.

Figure 3.

Linear correlation between density and: (a) time to ignition; (b) peak effective combustion heat; (c) peak mass loss rate; and (d) peak heat release rate.

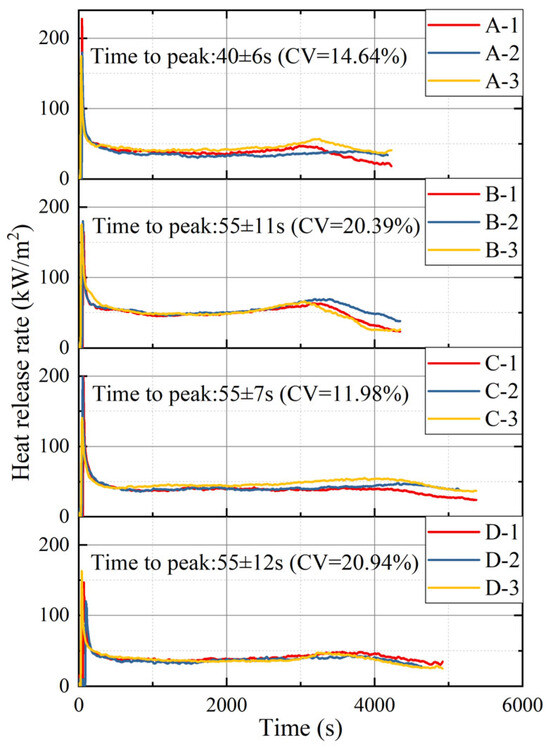

The heat release rate is an important indicator for characterizing the combustion performance of materials and a crucial basis for recording and analyzing. The heat release rate per unit area curve of each group is shown in Figure 4. The variation trends of curves of all specimens were the same, which all presented a bimodal shape. Specifically, the heat release rate rose rapidly in the initial stage of combustion, reaching its peak point (around 200 kW/m2), which was because the decomposition of the wood surface generated a large amount of combustible gas for flame combustion, releasing a lot of heat. When the pyrolysis moved from the outside to the inside, a protective charring layer formed and would isolate the internal wood from the flame; the curves dropped and remained stable subsequently. The time of the second peak of the curves in different groups appeared variably. From Figure 4, the peak heat release rate of Spruce (Group A) was the highest, with the maximum value over 200 kW/m2, while Larch (Group D) had the lowest release rate. The second peak points in the test curves of Spruce and Mongolian Scots (Group B) pine occurred at the same time, both occurring when the combustion had lasted for about 3200 s; while the second peak points of Douglas fir (Group C) and Larch occurred at a later time, which was after burning for about 4000 s. Among these four kinds of softwood glulam, the second peak point of the combustion curves of Mongolian Scots pine was higher (around 65 kW/m2). After the second peak, pyrolysis gradually decreased with the reduced combustible gas, the heat release rate dropped rapidly, and the char residue continued to smolder.

Figure 4.

Heat release rate (per unit area) curves of each group.

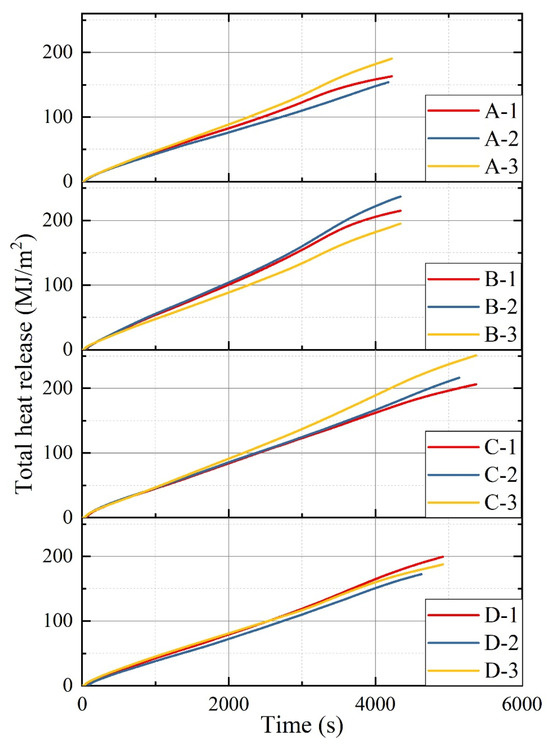

The total heat release is the cumulative energy released during the combustion, which indicates the ease with which the material burns and the hazard posed by the wood in a fire. The curves of the total heat release per unit area of each specimen are shown in Figure 5, and the mean value with ± SD and 95% confidence intervals of each group at fixed times are shown in Table 3. The curves of all the specimens kept rising with the ongoing combustion progress; in the later stage of combustion, the curve gradually became more stable, and the heat release rate decreased. Under the same size, the higher heat release would lead to a more dangerous situation. The curves for the three specimens of the same species were very similar. Combining Figure 4 and Table 3, when the combustion time is within 4200 s, it is found that among these four groups, Mongolian Scots pine released the highest heat under the same burning time compared to other species, while Larch had the lowest heat release. Spruce had a similar combustion behavior and close heat release with Larch at the same combustion time. From the curves in Figure 5, since Douglas fir specimens were burned for the longest time, the peak point in their curves was the highest. Furthermore, the initial slope of the test curve for the Mongolian Scots pine specimens was relatively large, indicating that the burning intensity was more intense in the initial stage.

Figure 5.

Total heat release (per unit area) curves of each group.

Table 3.

Total heat release of each group at fixed times.

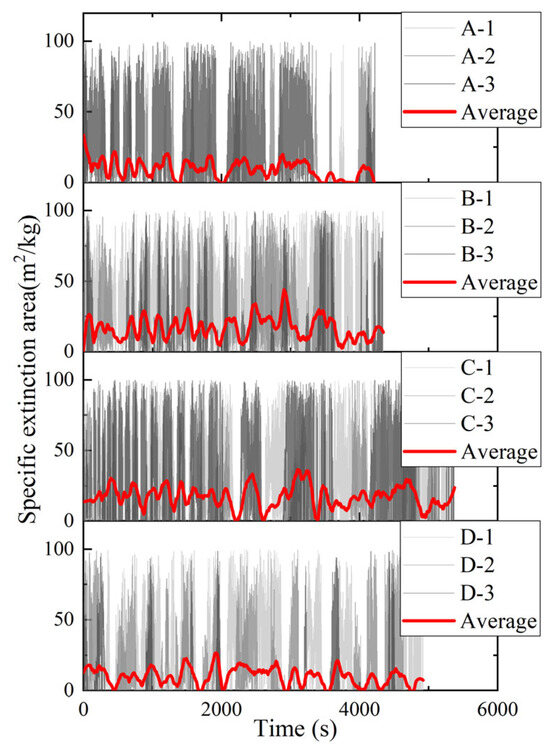

The specific extinction area is used to evaluate the contribution of gaseous volatiles produced during the pyrolysis of polymers to fire smoke. Wood is a natural polymer that generates a large amount of smoke when burned. A larger specific extinction area of wood often indicates a greater amount of volatiles. Figure 6 presents the specific extinction area data collected during the experiments for different groups of specimens, and the indicators of smoke production during the combustion process are shown in Table 4. The results showed that among these four species, Spruce had the lowest smoke production, as the specific smoke area, mean, and peak specific extinction area, and total smoke production of Spruce were the smallest. The specific smoke area of Mongolian Scots pine was 106% higher than that of Spruce. It is worth noting that apart from the specific smoke area, the mean and peak specific extinction area, and total smoke production of Douglas fir were the highest. For example, the mean specific extinction area of Douglas fir was, respectively, 242%, 94%, and 188% higher than that of Spruce, Mongolian Scots pine, and Larch. However, it should be noted that due to the uncertainties in the combustion process and the limitations of the number of repeated test specimens, the standard deviations of values in Table 4, except for the peak SEA, were relatively large. This indicated that the dispersion of the same set of data was relatively high. In future research, it is necessary to consider increasing the number of repeated specimens in the same group in order to reduce the variability of the data.

Figure 6.

Specific extinction area (per unit mass) curves of each specimen in each group.

Table 4.

Indicators of smoke production during the combustion process.

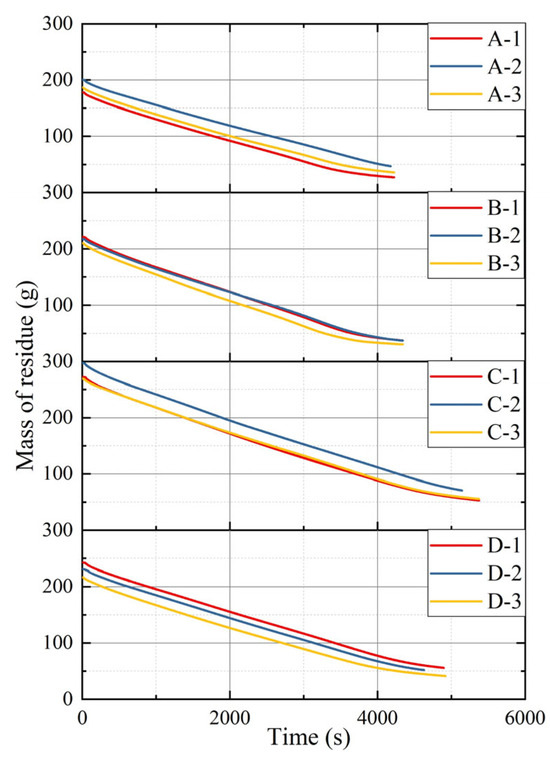

Figure 7 shows the mass of residue curves of each group, which is the mass that remains of the specimen as it undergoes combustion over time. In order to more intuitively compare the mass loss of each group during the 4200 s combustion process, the relevant indicators are summarized in Table 5. The variation trends of the mass of residual curves for each group of specimens were generally consistent, characterized by a gradual decrease in residual mass as combustion progressed. The slope of the curves remained stable, indicating that the mass of the residue decreased uniformly over time. From Table 5, it can be seen that even Douglas fir lost the most mass, it had the most residue mass and the lowest mass loss percentage (68%), which means that the Douglas fir was able to retain the greatest amount of weight after burning for the same period among these four species, which is of positive significance for the safety performance of the remaining structure. Mongolian Scots pine had the highest mass loss percentage (83%), which was 22% higher than that of Douglas fir. The mean mass loss rate of each species was close, which was 0.03–0.04 g/s during the burning process, while that of Spruce was slightly lower. When the mass loss rate is similar, a higher quality loss rate indicates a lower remaining mass of the specimen within the same period of burning time. In structural applications, this factor needs to be taken into consideration as the cross-sectional area of the component should be increased accordingly.

Figure 7.

Mass of residue curves of each group.

Table 5.

Mass loss of each group.

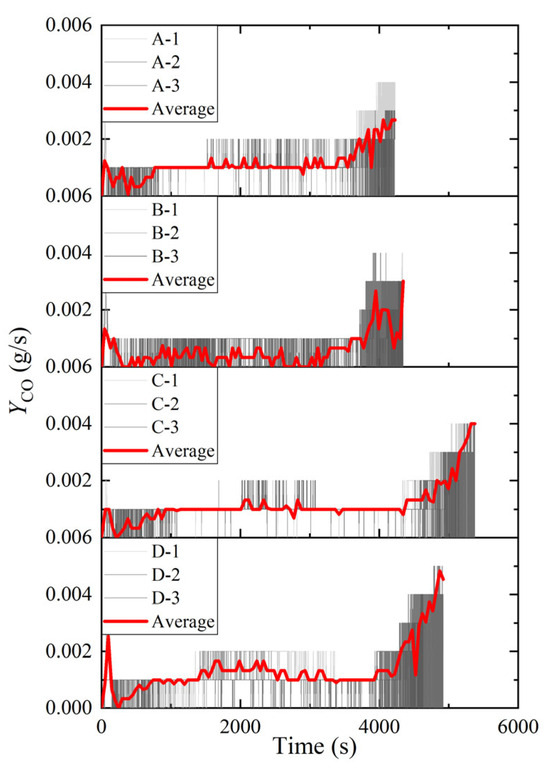

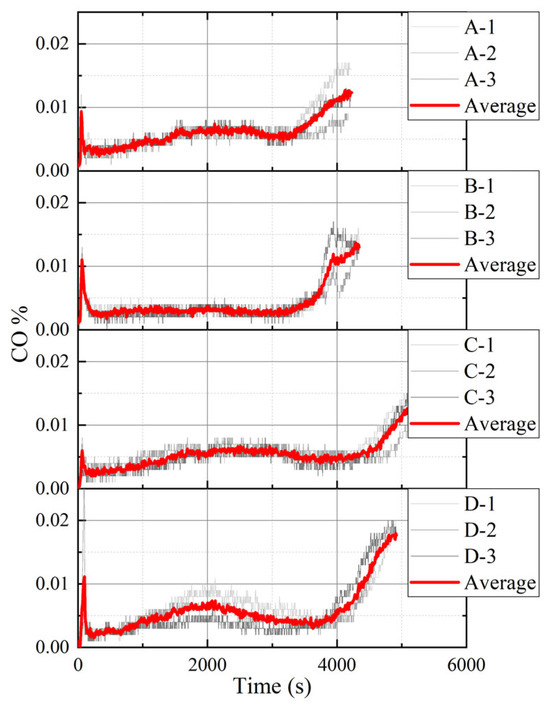

Figure 8 exhibits the yield of CO during the combustion process of each specimen group, and the content of CO (%) is shown in Figure 9. Table 6 shows the production volume of gas. It can be observed that the CO yield curves and CO content curves show a consistent trend of change. The CO yield and content of all groups were very low in the initial stage of combustion, close to zero. This was because during the flaming combustion stage, the low-molecular-weight organic compounds generated from wood pyrolysis mixed with air and underwent complete oxidation reactions to form CO2. In contrast, during the glowing combustion stage, the carbonaceous material produced by wood pyrolysis came into contact with oxygen in the air at high temperatures, leading to gas–solid thermochemical oxidation reactions that generate significant amounts of CO [22]. The yield of CO of each specimen group began to increase after 3500 s of combustion, while the content of CO was accordingly increasing. During this stage, the HRR begins to decay, marking the end of flaming combustion. This phenomenon was consistent with visual observations: at this stage, the open flames on the sample surface extinguished and transitioned into uniform smoldering combustion. Since smoldering combustion is a heterogeneous surface oxidation reaction occurring under oxygen-deficient conditions, its characteristic incomplete combustion leads to a significantly higher CO generation rate compared to the flaming stage. Among them, Spruce and Mongolian Scots pine exhibited lower CO yields, with a maximum of approximately 0.003 g/s, while Larch specimens showed the highest CO yield, peaking at around 0.005 g/s. However, when under the same combustion period (4200 s), the content of CO of Douglas fir and Larch was relatively lower. From Figure 9, at the time of 4200 s, the CO content of Spruce and Mongolian Scots pine was close (0.012%), which was 140% and 79% higher than that of Douglas fir and Larch. Since CO is the primary toxic product of wood combustion, the later the wood generates CO, the relatively safer it is in a fire. Therefore, it can be concluded that Douglas fir and Larch produced carbon monoxide later in a fire, making them relatively safer.

Figure 8.

Yield of CO.

Figure 9.

Content of CO.

Table 6.

Mass fractions of CO and CO2.

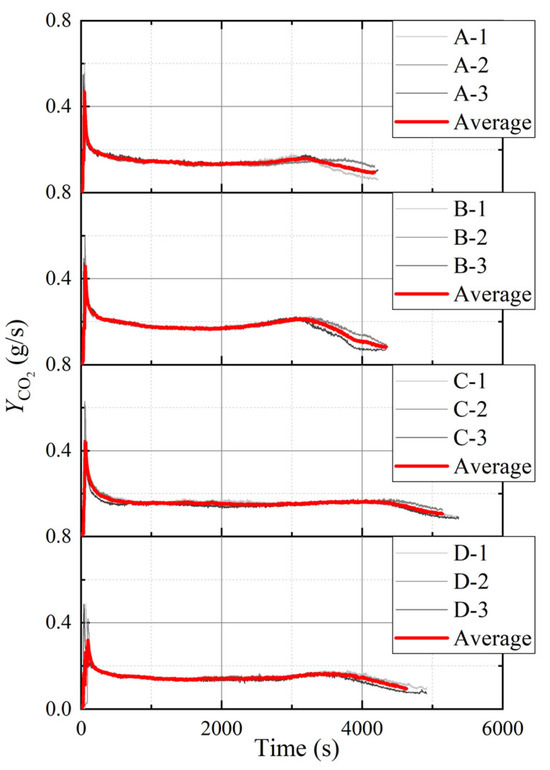

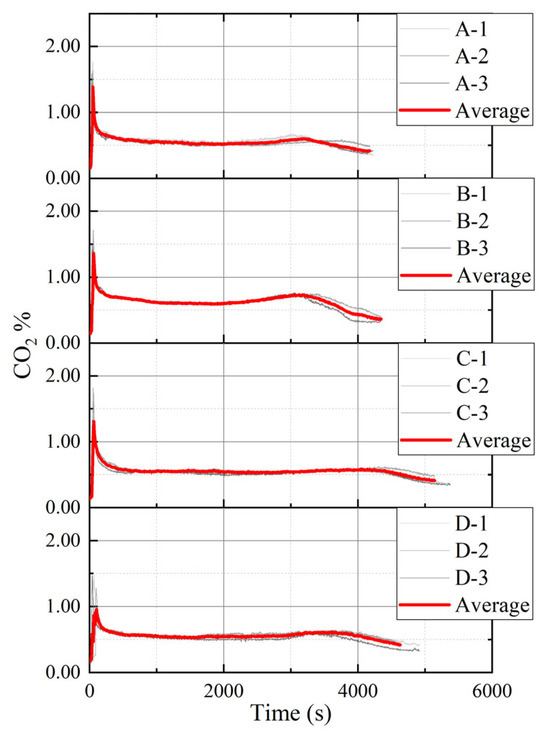

Figure 10 shows the CO2 yield curves of each group during the combustion process, and Figure 11 illustrates the content of CO2 during the burning process. Similarly, the trend of CO2 yield curves and CO2 content curves was consistent. The variation patterns of the curves are consistent across all groups, specifically manifested as a higher CO2 yield during the initial stage of combustion (flaming combustion stage). Apart from Larch specimens, the peak CO2 yield of the other species reached 0.6 g/s. As combustion progressed, the specimens transitioned from flaming combustion to glowing combustion, resulting in a decrease in carbon dioxide yield. The curves declined and gradually stabilized. Among all the specimen groups, Spruce specimens exhibited the highest peak CO2 yield (with an average value of 0.57 g/s), while Larch specimens showed the lowest (with an average of 0.46 g/s), which was nearly 20% lower than that of Spruce specimens. From Table 6, the Mongolian Scots pine generated the most CO2, while Douglas fir generated the least, which was 12% less than that of the Mongolian Scots pine. By comparing with Figure 4, it can be observed that the CO2 yield curves of each group correspond to their heat release rate curves. A second peak in the CO2 yield also appeared at the second peak of the heat release rate curve. In other words, during the combustion process, the CO2 yield varied with the heat release rate: when the heat release rate increased, the CO2 yield also rose.

Figure 10.

Yield of CO2.

Figure 11.

Content of CO2.

In general, of the four kinds of softwood glulam specimens, Spruce demonstrated the most aggressive initial fire behavior among the tested specimens. It exhibited the highest peak heat release rate and the highest peak CO2 yield, indicating it contributed intensely to early fire growth. However, it presented mitigating factors in other areas, showing low smoke production (specific extinction area) and moderate mass loss percentage. This suggested that while Spruce posed a high hazard in the initial stages of a fire due to its intense burning, it subsequently presented lower risks related to smoke obscuration and gas toxicity.

Mongolian Scots Pine had highly reactive and intense burning properties, which exhibited the largest total heat release. It displayed the steepest initial rise in total heat release and the highest second peak in the heat release rate curve, signifying sustained combustion intensity. This was coupled with the most complete consumption of fuel, as it had the highest mass loss percentage. Furthermore, it generated a large amount of smoke, as indicated by its high specific extinction area, but its CO yield was relatively low. Overall, this species presented a significant fire hazard due to its potential for rapid fire development, high energy release, and substantial smoke production.

Douglas fir posed the greatest total energy threat, releasing the relatively high cumulative amount of heat (total heat release) during the combustion process. It also produced the largest quantity of smoke. A key positive characteristic was its excellent resistance to consumption, showing the lowest mass loss percentage, which is beneficial for maintaining structural integrity in a fire. Additionally, its generation of toxic CO occurred later in the later stage. Therefore, Douglas fir represented a high-hazard material in terms of total fuel load and smoke, but with advantages in structural stability and delayed toxic gas production.

Larch showed the lowest combustion intensity, with the lowest overall heat release rate and the lowest peak CO2 yield. It also produced a low amount of smoke, similar to Spruce. Similarly to Douglas fir, Larch yielded the CO in the later combustion stage, and when under the same combustion period, it generated lower CO than Spruce and Mongolian Scots Pine. This combination of properties positions Larch as a material with lower fire intensity that was less likely to drive rapid fire spread.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, the cone calorimeter method was employed to evaluate the combustion properties of glulam specimens made of four kinds of softwood species. The indicators, such as heat release rate, total heat release, specific extinction area, mass of residue, yield of CO, and CO2, were evaluated and compared. The following conclusions can be drawn:

(1) After the test, a char layer was formed on the surface of all the specimens, and the thickness decreased. In addition, the lamination of each specimen was cracked, and there was cracking in the adhesive layer. The time to ignition and peak mass loss rate of the four softwood species used in the study were positively correlated with their density.

(2) All wood species exhibited a consistent bimodal heat release rate. Spruce presented the highest initial release rate with a peak over 200 kW/m2, while Larch showed the lowest. Mongolian Scots Pine demonstrated sustained burning with a distinct, high second peak. Mongolian Scots pine had the highest total heat release and showed high heat release in the initial stage, which significantly contributed to early fire development.

(3) Mongolian Scots pine had the highest mass loss percentage (83%) and generated substantial smoke than other species. Douglas fir was the most resistant in mass loss, with the lowest mass loss percentage (68%).

(4) Under the same combustion period (4200 s), Spruce and Mongolian Scots pine produced the most toxic CO, which was 140% and 79% higher than that of Douglas fir and Larch. Spruce produced the highest peak CO2 yield and low CO2 content during the combustion process.

(5) Glulam specimens made of these four softwood species have different combustion properties when considering their application in structural applications: if minimizing initial heat release rate and total heat release, choose Larch; if prioritizing residual mass and CO content, choose Douglas fir; if minimizing smoke, choose Spruce.

Author Contributions

Y.Z.: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, resources, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition; S.X.: conceptualization, software, data curation, writing—review and editing; T.Y.: validation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization; J.D.: investigation, data curation; Y.D.: resources, supervision; D.Z.: project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation General Project, grant (No. 2021M701490); National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant (No. 52508020).

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions: The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hawkins, W.; Cooper, S.; Allen, S.; Roynon, J.; Ibell, T. Embodied carbon assessment using a dynamic climate model: Case-study comparison of a concrete, steel and timber building structure. Structures 2021, 33, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yin, T. Cross-laminated timber: A review on its characteristics and an introduction to Chinese practices. In Engineered Wood Products for Construction; Gong, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, A.I.; Hadden, R.M.; Bisby, L.A. A review of factors affecting the burning behaviour of wood for application to tall timber construction. Fire Technol. 2019, 55, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, E.; Altinok, M.; Colak, M.; Ozaki, S.K.; Toker, H. Fire resistance of Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menzieesi) treated with borates and natural extractives. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 1101–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinka, J.; Mózer, V.; Hroncová, E.; Ladomerský, J. Influence of spruce wood form on ignition activation energy. Wood Res. 2015, 60, 815–822. [Google Scholar]

- Zachar, M.; Čabalová, I.; Kačíková, D.; Jurczyková, T. Effect of natural aging on oak wood fire resistance. Polymers 2021, 13, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, C.; Renner, J.S.; Xu, Q. Research on the Fire performance of aged and modern wood. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Wood & Fire Safety (WFS), Strbske Pleso, Slovakia, 12–15 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzi, E.; Kartal, S.N.; White, R.H.; Shinoda, K.; Imamura, Y. Fire performance and decay resistance of solid wood and plywood treated with quaternary ammonia compounds and common fire retardants. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2011, 69, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, K.; Wu, J.; Xu, L.; Tang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Liu, W.; Wang, L. Use impregnation and densification to improve mechanical properties and combustion performance of Chinese fir. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 214, 118101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezabeh, M.A.; Gairola, A.; Bitsuamlak, G.T.; Popovski, M.; Tesfamariam, S. Structural performance of multi-story mass-timber buildings under tornadolike wind field. Eng. Struct. 2018, 177, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Wang, Z.; Reynolds, T.P. Laterally loaded behaviour of connections in timber-timber composite (TTC) floor system: An experimental and analytical investigation. Eng. Struct. 2025, 342, 120937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Tsai, M.J.; Lin, C.Y. The charring depth and charring rate of glued laminated timber after a standard fire exposure test. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.; Carradine, D.; Moss, P.; Buchanan, A. Charring rates for double beams made from laminated veneer lumber (LVL). Fire Mater. 2013, 37, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucíková, L.; Janda, T.; Sýkora, J.; Šejnoha, M.; Marseglia, G. Experimental and numerical investigation of the response of GLT beams exposed to fire. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 299, 123846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, J.I.; Mizukami, T.; Naruse, T.; Araki, Y. Fire resistance of timber panel structures under standard fire exposure. Fire Technol. 2016, 52, 1015–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yue, K.; Zhu, L.; Lv, C.; Wu, J.; Wu, P.; Sun, K. Relationships between wood properties and fire performance of glulam columns made from six wood species commonly used in China. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 54, 104029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 5660-1:2015; Reaction-to-Fire Tests—Heat Release, Smoke Production and Mass Loss Rate; Part 1: Heat Release Rate (Cone Calorimeter Method) and Smoke Production Rate (Dynamic Measurement). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Dagenais, C. Investigation of fire performance of CLT manufactured with thin laminates. FPInnovations Proj. 2016, 301010618, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Muszyński, L.; Gupta, R.; Hong, S.h.; Osborn, N.; Pickett, B. Fire resistance of unprotected cross-laminated timber (CLT) floor assemblies produced in the USA. Fire Saf. J. 2019, 107, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machová, D.; Oberle, A.; Zárybnická, L.; Dohnal, J.; Šeda, V.; Dömény, J.; Čermák, P. Surface characteristics of one-sided charred beech wood. Polymers 2021, 13, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Qi, Y. Comparative study on combustion properties of species wood in timber construction. J. For. Eng. 2016, 1, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qi, H.Y.; Lu, Z.A.; You, C.F.; Xu, X.C. Investigation on releasing mechanism of CO2 and CO in bench-scale fire smoke. J. Eng. Thermophys. 2004, 25, 534–536. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).