Abstract

Studies show that BIM has compelling benefits for work health and safety performance. Its capabilities for visualisation, information management, collaboration and simulation make it a powerful enabler for enhancing training, hazard identification, risk management and site monitoring. However, BIM adoption is inconsistent, even in advanced countries such as the United Kingdom, Finland and Singapore. While significant work has been conducted on technical, organisational and cultural features of BIM solutions, there is a lack of literature on conceptual and empirical studies on government policy that could strengthen BIM adoption. Our study investigated the Australian policy landscape to encourage widespread BIM adoption for improved work health and safety performance. This study had two research questions: (1) To what extent does the Australian policy landscape support the adoption of BIM for work health and safety? (2) What changes can be made to the policy landscape to better support the adoption of BIM for work health and safety? This study employed interpretivism and in-depth qualitative methods. We addressed the first research question with an explanatory model comprising 19 interrelated barriers, and the second with another explanatory model showing diverse strategies across six interrelated types of policy instruments, leading to outcomes that strengthen BIM adoption.

1. Introduction

Construction is one of the most dangerous sectors in the world [1]. A leading cause of death and injury is falls from heights (FFHs), a complex and persistent problem [2,3] underpinned by various factors. One factor is poor information management, which leads to a lack of risk identification during project planning and design, inadequate training, minimal monitoring during construction and poor communication and coordination amongst all stakeholders [4,5].

Building Information Modelling (BIM) has the potential to promote information management and to support collaboration throughout the procurement and management of the project [6], potentially leading to stronger WHS management performance [7,8]. BIM has compelling benefits, as its capabilities for visualisation and simulation make it a powerful tool for strengthening training; designing for safety [9]; facilitating improved communication of safety information among the workers [10]; monitoring based on wireless and computer vision technologies [11] and strengthening compliance with safety standard and through improved digital storage and views of various clauses of safety standards [12]. The range of BIM’s applications is captured in one review that maps 35 studies showing how BIM can be mobilised for WHS management across a broad swathe of activities [13]. These studies have been helpful in highlighting novel adoption of BIM to strengthen safety performance. Notably, however, none of these studies focus on the role of public policy and how it can make such adoption widespread and systematic across the industry.

The lack of policy guidance explains, at least in part, why BIM uptake, in general, remains low and uneven; thus, its benefits, safety-wise and beyond, have not been optimised. Barriers to widespread adoption, for example, in Canada [14], Nigeria [15] and Brazil [16], have been investigated, but these studies do not focus on barriers to the adoption of BIM specifically for WHS management. Within this safety-focused domain, an emerging body of work has shown that even in countries like Finland, the United Kingdom and Singapore, which are often considered as leaders in the BIM space [7,8,17], do not reflect widespread, consistent BIM adoption to strengthen WHS performance, with one study reporting that adoption of BIM was limited mainly to large companies [18].

Understanding the barriers that impede widespread, systematic BIM adoption across the construction industry for WHS management is, thus, the first objective of this study. Unlike other research that lists potential barriers, we specifically develop a model that identifies 19 key barriers and proposes emerging interrelationships between barriers, which helps practitioners and policymakers in framing priority recommendations. A second contribution we make is understanding how these barriers can be addressed, specifically through the government strategically using a range of policy instruments. In this research, we propose an expanded toolkit of public policy instruments and systematically identify strategies under each.

2. The Policy Landscape

Public policy has been defined as a network of decisions by political actor(s) in a specific context, leading to the selection of specific goals and the means to achieve such goals [19]; as anything a government chooses to do or not to do [20] and as an activity specifically oriented towards a given ideology, underpinning the decision-making of a group to achieve certain objective [21]. Policy is enacted through policy instruments, and the literature suggests there are at least seven types [22,23,24]:

- Regulatory instruments are used by policymakers and regulators to enforce compliance, taking the form of laws, regulations, standards or even codes of practice with legal standing.

- Economic instruments take the form of incentives, often financial in nature, to influence the behaviour of producers or consumers. Examples are tax incentives, subsidies and tradable permits.

- Informational instruments are resources with rules, examples, cases or guidelines disseminated to guide public behaviour and decision-making.

- Voluntary instruments are mechanisms that facilitate self-regulation or agreements between government and private entities to achieve policy goals.

- Public ownership instruments involve the government’s direct provision of goods and services, as a reflection of its priorities.

- Right-based and customary instruments include contents of international norms, for example, those upholding human rights.

- Social and cultural instruments include tools that strengthen “ways of being” within specific communities.

Questions have arisen as to whether these categories are mutually exclusive or if they could be better defined. One might argue, for example, that all the instruments are arguably “regulatory” as they seek to shape/regulate behaviour (we are indebted to a focus group participant who pointed this out). It is beyond the scope of this study to fully reconceptualise categories of instruments; however, a key contribution of this study is to show how, in the domain of construction safety, the different types of instruments can be better nuanced and their interrelationships clarified to reflect the dynamics of the sector.

Our literature shows that to date, there is very limited work on explanatory models that analyse why BIM uptake for WHS management is low, and how different policy instruments can be mobilised to strengthen adoption. Two studies lay promising groundwork but stop short of a systematic, comprehensive approach. First, a detailed summary of enablers and barriers specific to BIM and WHS management integration was provided across seven categories, including culture, value proposition, client role, systems and processes, data, technology and regulation and policy [8]. This analysis led the researchers to articulate responses under the “client role” policy instrument. More recently, in 2023, the book “BIM and Construction Health and Safety Uncovering, Adoption and Implementation” provided a discussion of critical success factors for BIM adoption for WHS management, mobilised an innovation diffusion model and provided an empirical study [25]. The authors argued that mandating BIM for WHS management integration by governments was one of the critical success factors for widespread adoption. However, this study only made a cursory mention of the role of government and lacked detailed analysis from a policy perspective and did not seek further depth of understanding of the policy landscape and context.

In short, the work of London et al. [7,8,17] focuses on client leadership and, to a certain extent, on the need for a better value proposition for BIM but does not focus on the potentially central role played by government within this landscape. The work of Golzad et al. [25] also deals with this topic in a brief manner, referencing the role of government but without identifying specific policy levers. Noting this gap, this study seeks to address two research questions through two explanatory models:

RQ 1: To what extent does the current Australian policy landscape support the adoption of BIM for WHS?

RQ 2: What changes can be made to the policy landscape to better support the adoption of BIM for WHS?

To address RQ 1, we develop a novel explanatory model that explains key barriers to adoption for BIM for WHS management, with links between barriers. To address RQ 2, we present a second novel explanatory model that lays out strategies that can be mobilised under various policy instruments to strengthen BIM adoption.

3. Methodology

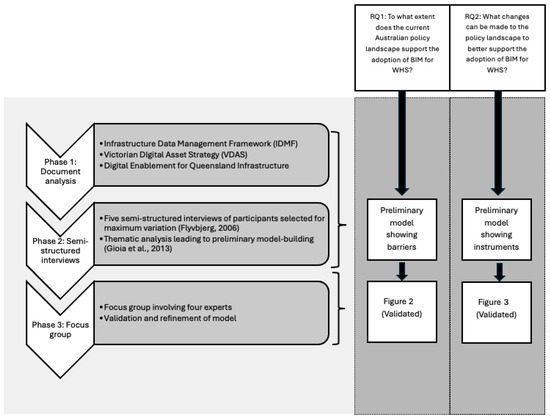

The epistemological approach of this study is interpretivism, a stance that is premised that social reality emerges from shared meanings and interpretations of people and groups [26]. The research design involves three phases:

- Phase 1: Content analysis of three key state government policies;

- Phase 2: Semi-structured interviews with thematic analysis to develop a model;

- Phase 3: Model validation through an expert panel group of key stakeholders.

A diagram showing an overview of the methodology is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of methodology [27,28].

3.1. Data Collection

Data was gathered from three sources: three policy documents (Phase 1), five semi-structured interviews (Phase 2) and one focus group discussion (Phase 3).

3.1.1. Phase 1: Policy Documents

We examined three policy documents from three Australian states. Australia is a federated nation with 6 states and two territories. The documents we analysed included the Infrastructure Data Management Framework (IDMF—New South Wales), the Victoria Digital Asset Strategy (VDAS-Victoria) and Digital Enablement for Queensland Infrastructure. Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland, the eastern seaboard states, are consistently the states where the greatest volume of construction occurs [29,30]. These documents were, thus, selected because they have the strongest potential to significantly shape the landscape for the potential use of digital technologies, BIM included.

3.1.2. Phase 2: Semi-Structured Interviews

Once we had completed analysis of the policies, we then used this information as a basis for conducting semi-structured interviews, which we analysed, leading to the development of a conceptual model. Semi-structured interviews align with interpretivism, providing rich qualitative data and in-depth descriptions of the phenomena under study. Researchers argue that semi-structured interviews are well-suited for exploring emerging research areas and qualitative trends that are little understood [31,32]. Open-ended questions were, thus, designed to elicit detailed responses to the research questions [27].

We adhered to researcher guidelines suggesting a minimum sample size of five participants [33,34]. To mitigate the risks of a small sample size, we mobilised three strategies: First, we used theoretical sampling [35] to achieve maximum variation [28], ensuring that different sectors (regulatory, education and business) were represented. Participants from different sectors were selected based on their qualifications, experience and contributions to their respective professions. Two participants were selected from academia; they were at the level of Associate Professor who had supervised PhD projects on BIM. The private sector construction expert utilised BIM in their projects, and that company was known to be a forerunner in the way they used BIM in infrastructure projects. A fourth expert was from the government and the policy sector, a leader in policy formulation and implementation. Finally, a fifth expert, a civil engineer by training, was a leader in the development of the IDMF who had also championed the digitalisation of the transport sector and the broader digital economy in NSW. This individual had worked extensively on BIM and digital transformation in the economy and is now managing their own company.

As a second strategy for mitigating the risks of small sample size, we later validated the interview findings with a focus group, discussed shortly. Finally, in addition to these five interviews, we also analysed two online recordings of Interviewee 5 delivering presentations on the importance of digital data and tools in the sector, including his views on the affordances and limitations of BIM.

Each participant was interviewed individually, and both video and audio recordings were made. The recordings and transcripts underwent thorough scrutiny, with necessary corrections made to ensure accuracy. The transcripts were carefully compared with the recorded interviews to detect and correct any potential errors.

The questions were developed based on the two research aims (see items 1–6). Items 1–3 are contextual; they focus on the participant’s specific context and their experiences with BIM. These details include whether the person was working for a certain sector, in what capacity and in what specific way they engaged with BIM. As noted previously, some had taught BIM, others had managed it from a regulatory capacity and others had used it in business. Item 4 is directly aligned to RQ 1’s focus on barriers. Items 5 and 6 are aligned to RQ2. While Item 5 focuses specifically on government and its policies, Item 6 acknowledges that there are policy instruments that can only be implemented effectively in collaboration with other sectors. Item 6, therefore, paves the way for input on the role of other sectors. Some questions were, of course, customised depending on the participants’ roles and backgrounds. An interview with a regulator, for example, would lead to discussions on the absence of regulations in BIM for WHS; an interview with educators would understandably focus on educational initiatives. The interviews lasted between 45 and 60 min, were recorded and then transcribed. The main questions are provided below. Follow-up questions were formulated based on interviewee responses, a practice consistent with good semi-structured interviews. For example, if a respondent spoke about the role of regulations as a response to Question 4, the interviewers probed more deeply into that as the interview unfolded.

- What is your role in your organisation?

- What are your experiences with BIM?

- How do you think BIM can be used for WHS management?

- Why do you think BIM adoption for WHS management is not more widespread?

- What can government do to lead to more widespread BIM adoption for WHS?

- What can [different sectors: business, education, professional associations, builders, clients, etc] do to lead more widespread BIM adoption for BIM for WHS?

3.1.3. Phase 3: Focus Group

After completing the interview analysis, we built two preliminary models to address RQ 1 and RQ 2. We then validated these findings through a focus group. In contrast to the semi-structured interviews, which were meant to create a flexible environment to support wide-ranging discussions, the focus group was much more directed. The findings from the interviews had already been distilled into models. We invited four participants. Again, selection was driven by theoretical sampling. Each participant came from a different sector: a social enterprise involved in construction, an integrated digital delivery software solutions company, a regulator and an academic. Two of the interviewees had been involved as interviewees in Phase 2. The approach achieved a balance in terms of prior knowledge of this research project. Two participants, previously interviewed, could now see how the interview findings had been translated into explanatory models, allowing them to validate for rigour from a perspective of analytical continuity. The other two participants could also validate the models, but from a “fresh” perspective. The tandem of views was thus balanced. Again, all four participants were experts in the domain of technological innovations in construction.

The focus group was designed to have two segments: a 15 min presentation where we shared the findings for research questions 1 and 2, specifically showing two diagrams, one for RQ1 and the second for RQ2, and a 1.5 h discussion where the participants were asked two directed questions: what can you add to [Diagram for RQ 1] and what can you add to [Diagram for RQ 2]? The goal of the focus group participants, who had their own expertise and interpretations, was to enrich and finetune the existing models.

The entire session was conducted using Teams software 25290.302.4044.3989. Video and audio were recorded and transcribed using Teams software.

3.2. Data Analysis

Data analysis consisted of three parts: policy document analysis, semi-structured interview analysis and analysis of feedback from the focus group.

3.2.1. Phase 1: Analysis of Policy Documents

We used content analysis on one type of policy instrument: regulatory instruments. Across three state-level policies, we looked for words such as “health”, “accidents”, “digital tools”, “information technology” and “safety”. This approach is known as content analysis [36]. We examined the extent to which these terms were used in relation to terms like “digital data” (e.g., “IT for safety”). As a result of this analysis, we were able to analyse the extent to which work health and safety was explicitly or implicitly discussed in the policy, and the extent to which such terms were meaningfully linked. This approach allowed us to identify specific areas of strength along with gaps in the policy.

3.2.2. Phase 2: Analysis of Semi-Structured Interviews

Interview data were then transcribed and analysed using a two-level approach:

- First-order, participant-driven themes;

- Researcher-driven themes [30].

Thematic analysis is critical to interpretivist studies such as these. Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data [27]. The video and audio recordings of the interviews were reviewed, transcribed and analysed. Codes were generated, which eventually formed the themes, and were later clustered into categories. The process we used for analysis is also similar to Braun and Clarke’s six-phase thematic analysis framework [37,38]. The theme categories then became the basis for developing explanatory models addressing the two research questions.

3.2.3. Phase 3: Analysis of Feedback from Focus Group

The two models that emerged from the interviews captured emerging conceptual models about BIM for WHS management. These diagrams were validated in a focus group. As mentioned earlier, four focus group participants were asked what can you add to [Diagram for RQ1] and what can you add to [Diagram for RQ2]?

The line of questioning in the focus group was one that followed direct elicitation. The participants were directed to comment on specific elements of two diagrams; they were not asked open-ended questions as in the interviews. For the RQ1 diagram, for example, the participants were asked, are there any other boxes or lines that you wish to add to this diagram? This meant that through the focus group, some diagram elements were enriched to include more dimensions. A box on “champions”, for example, was previously interpreted to mean “industry leaders.” But during the focus group, a discussion ensued, and the notion of “champions” was broadened to include unions and union leaders. Other elements were also refined, and others were added. “Analysis” in this case did not require distilling themes, but rather consolidating suggestions and changes into the previous diagrams. Details of these changes are also presented in Section 4.

4. Results

4.1. Research Question 1

The first research question that we sought to address was the following: To what extent does the current Australian policy landscape support the adoption of BIM for WHS?

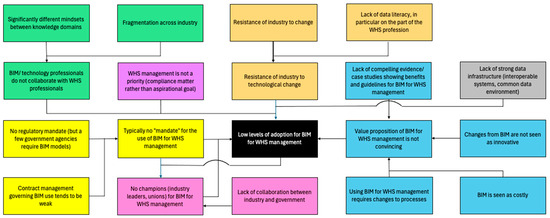

The findings that address this question are shown in Figure 2. A table showing the data structure is provided in Appendix A. The findings, shown in 19 interlinked boxes, reflect the barriers that explain low adoption rates. These barriers are categorised into seven clusters; each is explained shortly. Importantly, they are arranged in the beginnings of a diagram showing relationships of influence; that is, the boxes are linked to reflect relationships of influence. This is a departure from and a development of the table developed by London et al. [7].

Readers should note that we intentionally built on the extensive work performed by London et al. [7,8,17], which found that BIM adoption for WHS management was low and inconsistent across the construction industry. The interview questions were thus framed around this premise of low adoption. One of the key questions that was discussed, then, was “Why do you think BIM adoption for WHS management is not more widespread?” Narratives explaining the figure, along with empirical data to support the figure, are provided below.

Figure 2.

Explanatory model showing barriers leading to low levels of adoption for BIM for WHS management, with relationships of influence.

4.1.1. Typically No Mandate for the Use of BIM for WHS Management

The first set of barriers to BIM adoption for WHS management is linked to the finding that there is no strong national, state- or industry-wide regulatory mandate for the use of BIM for WHS management, a finding from previous work [7] that continues to be a challenge today. One interviewee thus noted the following:

[We must] mandate BIM, it is apparently [the] way to directly affect the industry, to adopt BIM for work health and safety, in regulations reference BIM and the digital technologies in the Act or in the regulations. I think the easy way for the government, that they can do is to mandate the BIM for work health and safety in public projects, in large scale infrastructure projects because they are often the major clients in the infrastructure, in the large public projects. They can lead by example for the government drive the industry transformation.—Interviewee 3

There are some government agencies, such as Transport for New South Wales and Health Infrastructure NSW, that mandate a model or the use of digital data in some form, but this is far from the norm.

Our content analysis provides additional insights into the weakness of the existing regulatory mandates. Regulatory instruments exist for the use of digital data, and others exist for WHS (the Work Health and Safety Act), but there is no mandate that covers both as related. As discussed in Section 3, we conducted a content analysis of three state-level policies (IDMF, VDAS and the Digital Enablement for Queensland Infrastructure). Space does not allow us to provide detailed findings on this contact analysis; what is noted here is that health and safety are mentioned, but they are not discussed in detailed operational terms and are meaningfully linked to statements mentioning technology, for example, WHS as goals of digitisation. Beyond general statements such as “Safety is a major concern of Victorian Digital Asset Strategy” and “Safety is the outcome of BIM integration with schedule data”, the policies do not reflect a strong link that explicates, in detailed terms, how digital data and digital tools can be mobilised specifically in support of WHS management.

We, thus, pursued this as a line of questioning during the interviews. In Section 3, for example, we described how one of the questions asked was what existing policies are you aware of that support BIM adoption for WHS management?

This question led to a discussion on why the WHS Act did not make specific provisions for technologies such as BIM. Interviewee 1, who is affiliated with the safety regulator, believed that the non-inclusion of specific technologies in the Act was intentional and allowed for the legislation to be “future-proofed” against rapid changes:

I think one of the ways is to adopt that principles-based outcomes-based approach. That’s what been working well in the past for work health and safety. You don’t necessarily specify BIM because… you know AI has come along. There might be new technologies coming very, very quickly at the moment because the way that innovation is happening, it’s bringing new technologies faster than any time before in history. And so, we want to make sure that any regulations we put in place are future proofed so that it is inclusive and covers any covers any new technology come along. So, there would be opportunity to… draft codes or regulations around how to use technology.—Interviewee 1

While future-proofing has its merits, Interviewee 1 did acknowledge that the lack of explicit engagement with technology left an important gap in the policy that had to be addressed.

In summary, regulations exist for WHS and for the mobilisation of digital data for sound decision-making across the life of government infrastructural assets; however, there is no meaningful legislation that fuses both. An alternative to a regulatory mandate would be the use of contracts. Recommendations included setting expectations on the use of BIM for WHS early and optimising flexibility/prescriptiveness in relation to BIM for WHS management provisions.

4.1.2. WHS Management Is Not a Priority, but a Matter of Compliance

Apart from the lack of a strong regulatory mandate, a second group of barriers is related to the perception of the relative importance of work health and safety as a strategic goal across the industry. For the most part, WHS management is seen as a compliance matter or a regulatory requirement; this makes people not pay particular attention to it, at least in terms of foregrounding it as a high-level goal. One interviewee noted that the safety function was merely a matter of filling out paperwork. The same interviewee also noted that this barrier had deep, entrenched cultural roots. State governments have sought to address this challenge by prioritising BIM and/or digital tools in some form, as indicated by the three policies analysed. However, as we have noted, these policies have limited input and direction on the adoption of BIM specifically for WHS management. Stronger leadership was needed to create a stronger safety culture. Leadership (“champions”) is a point we return to shortly, but the need for such cultural change was raised.

4.1.3. BIM/Technology Professions Do Not Collaborate with WHS Professionals

The lack of appreciation for WHS management may be related to a third group of barriers. The interviewees noted that there was a distinct lack of meaningful collaboration between technology professions, including BIM experts, and WHS professionals. In part, this could be traced to the fact that the WHS domain had become very difficult to understand, given its convoluted and overly complex processes, thus requiring more specialisation:

[Requirements] just become impossible to understand. I think the risk for work, health and safety is similar where it could just become amendment to amendment to amendment of the requirement that they become cluttered and convoluted and very difficult to follow.—Interview 2

Another point was that WHS as a domain was seen as traditional, and thus very different from the more “high-tech” professional roles that were directly engaged with technology and digital innovations. This would manifest in different mindsets, attitudes and practices. The inability of most WHS professionals to adapt to new technologies was also seen as a disadvantage, given the potential of emerging technologies in the WHS space. BIM adoption, then, is hampered because technology and WHS remain “siloed” within narrow domains. Resistance to technology is taken up in the next group of factors.

4.1.4. Industry Is Resistant to Technological Change

The interviewees were also quick to point out what is already a widely accepted observation about the construction industry: it is very resistant to change in general.

People doesn’t [sic] want to change. I think that’s easy to understand. You know, people are used to the traditional approach to manage work health and safety. They don’t want to change.—Interviewee 3

This emphasis on WHS professionals using traditional approaches is reflective of the broader trend of sluggish technology adoption across the sector, with Interviewee 2 claiming that it was “the biggest” challenge of the industry:

…the biggest issue is the construction industry is just so slow on the uptake of technology… it’s so far behind other industries.

Digital technologies were seen to be difficult to adopt because, across the sector, people were described as lacking in a critical skill: data literacy. Interviewee 5, in fact, pointed this out as a central barrier to BIM and technology adoption in general. Given that the government is positioned to incentivise the development of specific skill sets, the development of data literacy is seen as something that the government should be taking note of:

…I think there is a lack of data literacy in our sector, I think. Like there’s a few observations that I found...The business identifies, I have a problem and then they go straight to what are the software vendors you know?... What they don’t do is start more first principles of what are the processes that we have? How do we design the data that we’re going to need and then coming up with better requirements to then going to the software vendors or even building out, you know, sort of a collective solution that relies on BIM and other software as well. But that’s because there’s Just this lack of it’s either you know data literacy or even just enterprise architecture.—Interviewee 5

4.1.5. Value Proposition of BIM for WHS Management Is Not Convincing

Amidst all the barriers discussed so far, a central concern has emerged. This fifth group of barriers is related to the fact that the value proposition of BIM for WHS management has not been fully appreciated across the industry.

Why it is not being used? So when we look at health and safety in Australian construction industry, every year we’ve got around 30 fatal cases and many of them are fall from high accidents?... I think if companies realise that to reduce fall from height accident or struck by object that BIM actually can bring in a new perspective how to prevent these accidents or remove the causes of these accidents. Then they would be more motivated to use it in the design phase as well as in the construction phase.—Interviewee 2

Another point that was raised was that some people did use BIM, but not primarily for WHS management purposes. BIM capabilities are, thus, mobilised to support the more “typical” business goals: design, construction or project management. These mindsets underpin “narrow” purposes for BIM require broadening, since the objectives of safety and economic objectives do not have to be mutually exclusive, a point alluded to by Interviewee 4:

So, I know most companies they use BIM for number of purposes and safety is not their top priority. They use it for construction planning. They use it for cost planning. So health and safety can also be one of the benefits that come with it, but probably not the main reason why they use BIM for their project.—Interviewee 4 emphasis ours

One way to change people’s mindsets and to elevate the industry’s appreciation of BIM’s potential to improve WHS performance is by systematically accumulating a body of evidence of its benefits in the form of case studies, which, to date, is sorely lacking. A systematic body of evidence showing BIM’s benefits in the WHS domain must be built up. Interviewee 3 claimed that

That’s the perception and there are, you know, lack of well documented case studies. and best practices that could show that BIM has directly improved work health and safety managing because if I was the top management in a company, I need to be convinced of the value proposition of using BIM for work health and safety otherwise they could be additional requirement or additional burden or cost.

One challenge about building this evidence base is that there may not (yet) be a large body of data that clearly demonstrates that BIM significantly reduces, prevents, or manages health and safety incidents. There are ways around this: one could instead show evidence that the status quo is untenable. This could help justify investment in BIM, which can be quite substantial.

4.1.6. No Champions for the Use of BIM for WHS Management

Because of the lack of a compelling mandate (Section 4.1.1) and the lack of a convincing value proposition for BIM for WHS management (Section 4.1.5), it is unsurprising that the interviewees claimed that there is a lack of champions for using BIM specifically for WHS. One of our interviewees was a champion for digital tools and common data environments in a specific sector (transport), but their experience was the exception, not the norm. According to interviewee 3,

…the top management, the senior management of the company, they must recognise the value of using BIM to improve work health and safety and then the top management can create culture of the organisation. What are the values that sit on top of the evidence when you have the value proposition.

Other champions were also identified, for example, union leaders who could advocate for BIM use to achieve better, safer working conditions. Champions could come from across sectors. Clearly, potentially influential leaders capable of pushing for more widespread BIM adoption have not been convinced.

4.1.7. Lack of Strong Data Infrastructure, Data and System Interoperability and a Common Data Environment

A final barrier has to do with the lack of integration of systems and data. In a video recording we analysed for this study, one speaker, who was also one of the interviewees, made a cogent argument: as important as BIM is, common data environments (CDEs) are also critical and can, in fact, transcend BIM as a foundational solution for increased technology uptake in construction (RISSB 2022).

BIM is one of the deliverables in construction, but it is underpinned by a common data environment. BIM is not central; but there is a limitation of BIM in that BIM requires that you manage metadata inside a 3D model and I’d sort of put out the concept that may be 3D models aren’t the best vehicle for managing metadata, every other sector just uses data bases, every other sector built expertise in this space from data governance, data management, data analytics and business intelligence, but if we continue to insist on using BIM as a solution being a metadata stored inside a 3D model then we are locking away the capability of accessing metadata on a broad scale, a CDE is central instead of BIM being the core I’d say is a component.—Interviewee 5

Having explored the landscape showing barriers that explain low, inconsistent BIM adoption for WHS management, we now turn to solutions as we address RQ 2.

4.2. Research Question 2

The second research question that we sought to address was the following: What changes can be made to the policy landscape to better support the adoption of BIM for work health and safety?

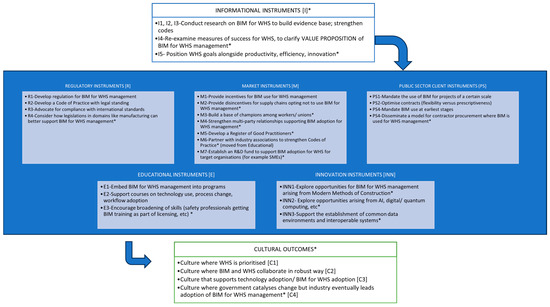

Our findings are summarised in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Explanatory model showing relationships between policy instruments. (*) shows changes from interviews to focus group.

Moving from top to bottom, the figure shows informational instruments, which influence five other instruments. Regulatory, market/economic and public sector instruments were all discussed in the literature. Two new types of instruments, education and innovation instruments, were also identified. All these then influence what we refer to as cultural outcomes. A key finding, then, is that cultural instruments are not actually “instruments”, at least in this context, even if the literature suggests they are. The interview and focus group findings on culture, for example, include insights like the need to “Elevate the value of WHS” in the sector or the need to embrace technology and change. Such statements express an ideal (outcome), not instruments to achieve the ideal. Therefore, the box that was previously named “cultural instruments” has now been renamed “cultural outcomes” and appears at the bottom of the figure to emphasise that it is an end result.

We now discuss the details of each policy instrument. Due to space limitations, narratives that follow will focus only on selected examples. In the narratives, examples are also indexed [“R1”, “I4”] for easy cross reference to the diagram.

4.2.1. Informational Instruments

“Informational instruments” are the primary lever of influence. They are seen to lay the groundwork for change; once mobilised, other instruments (regulatory, educational, etc.) could then be implemented with less resistance. For this reason, informational instruments are discussed first.

One important theme that emerged from the interviews was the need for clear information and evidence about the benefits of BIM for WHS management to strengthen its value proposition (as noted in the discussion in Section 4.1.5). One recommendation was for the government to partner with industry associations to conduct research on BIM for WHS management [I1]:

Industry associations [could] co-develop some research projects based or focused on BIM for work health and safety. Like we have done in a few years ago, it’s very successful projects and delivered a number of tangible contents that could be directly adopted or used by the companies.—Interviewee 3

An outcome of this research would be case studies showcasing best practice, roadmaps, standards and guides on the use of BIM, led or co-developed by government [I2].

Apart from the clients, the industry associations in the industry body or they have the members of the private companies, they are all members of the Industry Association. So, the industry association could play a big role in the transformation process. Let’s see, for example, they can publish or we can develop the best practise guide on how to use BIM to manage facilities and they can provide the members with key studies. They can provide trainings, webinars, or they can change the standards. They can change the standards and provide direct guidance for the companies to change their internal processes and to guide them to provide them a road map to progress in the adopting BIM for work health and safety.—Interviewee 3

Case study evidence was seen to be particularly important:

I would love to see successful case studies in Australia and make it, I mean, why companies would like to use BIM and what would be the motivation? It’s always about the return on investment and if there are successful cases in Australia to share and promote to professional bodies... some successful adoption of BIM and what is the return on investment or reduction in incidents or fatal accidents. So, some solid evidence to convince the industry this is the way to go. If you don’t join this journey, you left behind and kind of give them opportunity to see there are benefits… So the solid evidence to demonstrate the benefits, the return on investment either leading indicator or lagging indicator. Yes, she had a successful story around.—Interviewee 4

Based on evidence and emerging best practices, the government can then partner with industry associations to change codes of practice to better reflect BIM for WHS management [I3]. These are industry/professional codes of practice, not codes with legal standing as discussed previously. Both have a role in influencing technology adoption in the sector. Notably, though, mechanisms for implementing this strategy require further exploration.

Industry associations is something that we need to engage with to change the code of practises. I’m not quite clear about the pathway to change those codes of practise but I think that’s from my understanding the industry associations, the industry body.—Interviewee 3

Participants then noted the need for the government to re-examine measures of success for WHS, to clarify in more vivid ways the value proposition of BIM for WHS management [I4]. WHS management targets had to be compelling, even alongside the seemingly more urgent commercial objectives:

Well, because if you put up a whiteboard around one of the key issues because with construction and delivery, there’s probably a handful of really key issues right around there, and so the question then is, how does this, you know, you want to put this up on that whiteboard as well, so that there’s a spotlight on. And so somehow this also is this solving some of the other problems. Then you know that’s a benefit.—Focus Group participant 1

There was also a need for the government to position WHS goals alongside productivity, efficiency, innovation [I5], to demonstrate that they were not necessarily mutually exclusive, and that BIM could address these simultaneously. The value proposition of BIM for WHS management must be very clear for greater adoption in the industry:

And then it comes to that key question. So what’s the benefit to industry ultimately?And we know it’s saving lives. It’s gonna be productivity. It’s gonna be in a cost control, et cetera, but if they can, if they can find that and they can see that, then they’re gonna be the driver.—Focus Group participant 1

4.2.2. Regulatory Instruments

The interviewees were generally in agreement that it was important for the government to develop fit-for-purpose regulatory instruments that mandate the use of BIM for WHS management [R1].“Fit-for-purpose” meant, for one, that these regulations had to be streamlined and relatively simple:

I think regulation and standardisation [will promote BIM adoption for WHS management]. But I have a disdain for the cluttered policy and regulatory systems out there at the moment, like an example that I’ve just been working through with one of the project managers. Here is like the awards for the pay of our employees. So cluttered they’re so complicated. There are entire legal bodies devoted to interpreting these awards to try and provide information to businesses like ours on how to pay their guys, you shouldn’t need that If they were written correctly in the first place, you shouldn’t need a lawyer to help you understand a bit of information that is intended to simplify the pay process for your employees.—Interviewee 2

Mandating BIM for WHS management through regulation also meant being clear about operationalising how BIM was to be used for safety on site:

I think government already take the lead to at least in Queensland and I think in Victoria now, and I think also NSW, so government projects mandate requirement to have BIM model and I think is important not just put on paper that’s such a requirement but how to implement it and follow through and how that BIM model is being used on site.—Interviewee 4, emphasis added

Succinctness and clarity of regulatory requirements were also seen to be important attributes of regulation, as this would support implementability and enforceability. Underpinning “fit for purpose” BIM for WHS regulation is the need for a set of significantly consistent WHS standards, preferably at a national level.

In the absence of any such regulations or in the face of difficulties in crafting these, an alternative that was suggested was the development of a Code of Practice with legal standing, outlining pathways to the adoption of BIM for WHS [R2].

“International standards” were seen to play a critical role in the regulatory landscape. There is therefore a need for the government to actively advocate for compliance with international standards [R3]. New international standards on the use of BIM for WHS management, if implemented strategically, are likely to strengthen BIM adoption for WHS management.

Finally, one point discussed was that the current legislations on safety presupposed that activities were taking place within a traditional construction site. However, modern methods of construction, including prefabrication, now involve the manufacture of building components, pods or systems within a controlled environment, outside of construction sites. Therefore, pertinent regulations in the domain of manufacturing must, thus, be assessed to see how much they facilitate BIM adoption. The government must now consider how legislations in domains like manufacturing can better support BIM for WHS management [R4].

4.2.3. Market/Economic Instruments

During the interviews, one participant noted that the government can provide incentives for companies to use BIM for WHS management [M1]. The example included giving incentives for adopting BIM and for updating the model. During the focus group, another example of incentives emerged:

[It’s] possible to link the BIM for work health and safety to insurance premium ‘cause, that would be the cost to the company. But if the government or whatever can encourage or collaborate with insurers if that company have [sic] a good plan for work being for worker, or if they have shown some record in BIM for work health safety, [maybe] that could be reflected in the reduction of the insurance premium.”—Focus Group Participant 4

Alongside incentives, another participant suggested that the government could also mobilise dis-incentives for not utilising BIM for WHS management, for example, by making things more complicated for stakeholders who choose not to comply.

Discussions also touched on other critical stakeholders beyond industry and business leaders, who could also be champions for BIM adoption for WHS management.

So you know the question is, have we got all the right people that we’re engaging with? I still think that one of those are the unions, which are and then many. Invariably the construction industry, as you know. So it’s not just the CFMEU. It could be the local trades union. It could be the plumber’s union et cetera. And they’re all also focused one of their core pillars is safety”—Focus Group Participant 1

Following this point, the government can build a base of champions among workers/unions, who can advocate for the more widespread use of BIM for WHS management [M3]. The championing of BIM for WHS management by government, industry leaders and workers has been described as an ongoing tripartite collaboration by one participant. One action that can be undertaken, then, is for the government to strengthen such multi-party relationships, to further strengthen advocacy efforts for BIM for WHS management [M4]. This addresses, among other things, the perceived lack of collaboration between industry and government.

As networks of support for BIM adoption for WHS management grow, it becomes important to keep track of entities that are committed to good practice. A suggestion was thus made for the government to develop a Register of Good Practitioners, making use of BIM for WHS management [M5]. Finally, one participant noted that supporting smaller players in this network was also seen as important. Government partnering with industry associations to redevelop industry/professional codes of practice [M6] is also critical as an effort to strengthen BIM adoption capacity among market-driven firms. As a final suggestion under Market/Economic Instruments, one participant suggested that the government set up a Research and Development fund to support adoption of BIM for WHS for target organisations (like SMEs) [M7].

4.2.4. Public Sector Client Instruments

“Policy” is often equated with regulatory instruments, so it is important to highlight that the government has another type of toolkit available at its disposal for influencing the construction industry: its role as a public sector client. This area of policy was discussed extensively [7,8,17]. In this study, different public sector client strategies emerged from the interviews and focus group.

First, it was noted that as a public sector client, the government can mandate the use of BIM for WHS management for projects of a specific size or scale [PS1]. As one interviewee noted,

…if [a] client or developer makes it, this is my requirement, listen to me, I’m willing to put resources, I’m willing to put priority to use BIM for various purposes, including health and safety. Then it will happen.—Interviewee 4

This practice has been called “client leadership” [7,8,17] and is seen to be a significant driver for BIM adoption for WHS management across the industry:

…client leadership is the number one driver for promoting the BIM for work health and safety. So, because they have money, they have the power, they can have a big influence on their supply chains. The decision whether to adopt BIM for work health and safety is often start or driven from the top management.—Interviewee 3

Given the current absence of regulations mandating BIM, public sector clients could mobilise contracts strategically to incorporate provisions and requirements for BIM adoption specifically for WHS management goals and metrics. As a public sector client, the government can ensure that contracts of clients with supply chain actors specify BIM for WHS management [PS2]. An interviewee argued that the government can be explicit about its requirements, saying

I want the BIM model to be part of the contract tender document and it may even protect the precedence over drawings. So even there’s a BIM model, sometimes people will work back to 2D drawing when dispute happened...that should be a contract hold binding BIM model and everyone, this is the true source of information and we use it for all the things, planning, for sequencing, for planning cost, cost saving whatever and health and safety, hazard identification, site monitoring. So, it is in the contract and the client requires the contractor to put a percentage of money in the tender for utilising the BIM model, for updating the BIM model—Interviewee 4

Contracts are thus critical, as they might be the sole instrument that compels the supply chain to take up the rather difficult process of changing its entrenched practices to accommodate BIM:

So, in that project we highlighted client leadership because subcontractors, contractors, they only care about what’s in the contract. And so if you as a client think about what you want and will need and can clarify that specifically in a contract, then you will achieve performance, or at least you still have to monitor and enforce performance through the contract. But that is a big part of setting the expectations and the communication clear.—Interviewee 1

Crafting contract provisions for BIM adoption for WHS management is not an easy task, as the industry is still struggling to discern the so-called sweet spot between too many and too few specifications (see Section 4.1.1). One might easily lapse into one extreme, as noted by the earlier quote on “command and control” from Interviewee 1.

Apart from the prescriptiveness of contract provisions, specifications on the timing of BIM adoption are also critical. As a public sector client, the government can mandate the use of BIM during early project stages, definitely before tendering and ideally across all project stages [PS 3]. In the contract, WHS goals should also be translated into clear, measurable indicators and targets:

They can also set clear WHS performance targets, performance indicators that are linked to BIM adoption, so they are not just there to reduce how many percent of incident but how many percent of incidents rate and how the reduction is linked to the adoption. For example, the contractors can be required to demonstrate how BIM will be used to reduce safety incidents or how BIM will be used for the safety planning, reporting, they can provide a plan in the tendering. But anyway, I think the tendering and procurement is from my point of view the number one priority, that the private companies can think of have impact.—Interviewee 3

Realistically, however, it should be important to note that strong work health and safety performance, while an important goal, will always be juxtaposed with other economic and social goals, and decision-makers will often have to make choices of how much to prioritise each.

There are some other areas they consider [in the tender process], the cost… the social impact, the sustainability environment or nature. They can do all those things there in Aboriginal participants’ how this could work together and make it integrate. We’re not just developing some particular tender evaluation approach for the health and safety itself. We are actually balancing all of those options. All those options, sustainability, health and safety, social value and all of those things and the cost and all of that approach, I think that would be an opportunity.—Interviewee 3

Still, there are benefits to “spotlighting” WHS goals more than the current practice does. One suggestion that emerged was that, as a public sector client, the government can develop and disseminate (as a guide) a model for contractor procurement that involves the use of BIM for WHS management [PS4].

4.2.5. Educational Instruments

Participants proposed recommendations under Educational Instruments. In terms of government supporting courses on technology change, data literacy and workflow [E2], one participant suggested that taking a pilot study approach would be effective:

I guess for me, education is like just so important… maybe having a pilot around something, you know, so you know, the things that the safety managers were maybe get them involved in something that shows them this is how you can use the technology and can get a benefit and educate them on that.—Focus Group Participant 2

New examples were also discussed in relation to the government intentionally broadening the skill set of the work force [E3]:

Coming from a safe work perspective as well to educate our inspectors in how to read a model, it’s not just the work, health and safety people in industry that struggle with digital literacy. It’s also us on the other side, we have an engineering team that’s kind of a specialist team that has, you know, slightly higher skills. But we have a whole construction team focused inspectorates that I don’t know what their literacy skills are in terms of data, digital, how to read a model like that if that, which should be shared with us.—Focus Group Participant 3

This broadening of skills could be extended and formalised further, for example, into the realm of broadening safety professionals’ licensing requirements:

…it has been identified that there is a separation between BIM professionals and WHS professionals. So when we certify the WHS professional…Is it possible that to require or in the licensing process require them? The big competencies to be integrated into like the training as part of the licensing or CPD (continuing professional development)?—Focus Group Participant 4

4.2.6. Innovation Instruments

Focus group discussions led to the identification of a new type of instrument, referred to here as innovation instruments. This group of instruments refers to the government engaging with new trends, for example, new construction methodologies and technologies, and in doing so, finding new ways to intentionally steer the construction sector so that these developments can be embraced. As new changes are embraced, new opportunities can be created to adopt BIM for WHS management. An observation about the discussion here is that suggestions were more nebulous, and specific steps were not formulated, which was understandable given the dynamic and largely undefined contexts. Nevertheless, three directions were identified.

First, given the imminent expansion of the industry into modern methods of construction, including prefabricated construction, the government must explore opportunities for incorporating BIM for WHS management in controlled environments away from traditional construction sites [INN1].

…things like modern manufacturing, you know, sort of. You know modular et cetera. Where does that fit in here? So going from construction to assembly is, so we’re now heading into with the housing price that we have, there’s going to be a larger focus on assembling, not just construction. And so and the other thing we’re seeing in the market is that productivity is down tremendously.—Focus Group participant 1

Second, given the increasing ubiquity of trends like digital technology, quantum technology and artificial intelligence, the government must explore opportunities for expanding the capabilities and reach of BIM for WHS management, for example, through pilot studies involving the use of AI-powered tools and apps, as well as other technologies that can be linked to BIM like sensors [INN2]:

And then also just on to my, like my AI comments, there’s also other technologies as well that we’re using. Which you might wanna touch on is in particular IoT. So we’re using a lot of sensors. Sensor data to inform us about things like, you know, somebody’s moving too close to, a no-go zone. Someone you know, the cranes falling over?... But you know what I mean that we’ve got sensors that are tracking, tracking the plant, tracking the resources to give us potential safety insight.—Focus Group Participant 2

Finally, given the increase in the use of digital data, the government must advocate for the systematic establishment of common data environments that support expanding project domains and prioritise the interoperability of data [INN3], leading to a more seamless digital environment, a barrier noted in Figure 2.

You know, using tools that are interoperable, that can easily share to produce the model because that’s something I think is not captured here. To ensure the interoperability of the data. Because you’ve got multiple stakeholders that will build this BIM for work, health and safety.—Focus Group Participant 2

In the UK, a systematic pathway to increasing data integration has been proposed by weaving together the affordances of BIM with Internet of Things (IoT), Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and the API formats for Open Building and Big Data exchange [39].

4.2.7. Cultural Outcomes

The final element of Figure 3 is the cultural outcomes element. The participants pointed out that there was a need for an industry culture that prioritised WHS [C1], supported collaboration [C2] and supported the adoption of BIM for WHS management [C3].

A valuable insight that emerged was about this culture’s most significant feature. A focus group participant pointed out that the government would not always be the main driver for BIM adoption for WHS management. Government, it was noted, would catalyse change, but industry would eventually lead adoption of BIM for WHS management [C4].

As a conclusion to this discussion on empirical findings, an overarching insight thus emerges: Government policy instruments, discussed here, allow the government to collaborate and work with stakeholders, including industry. Such policy mobilisation can begin to change mindsets, attitudes, practices and eventually formal and informal work structures. They catalyse change. But change can reach a critical mass and can become sustained by forces other than government. Those “other forces” are seen to be fuelled primarily by industry. If performed effectively, the government can pass the baton, as changes result in the industry being “enabled to lead” in the effort to adopt BIM for WHS management.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

As an exploratory study, the research has a key limitation—there were only five interview participants, which might raise questions about the comprehensiveness or transferability of the findings. We have explained three mitigating strategies: theoretical sampling for maximum variation, validation through a focus group and enrichment of the findings through content analysis and analysis of recordings. We also note research that argues five interviews are acceptable for interpretivist studies. Although this study has limitations, it provides a sound methodology that has been designed and tested for replication.

This study makes contributions to conceptual development and has clear implications for practice. In terms of conceptual development, this study contributes to our knowledge base through confirmation of previous understandings of BIM and WHS management integration adoption. But it also now sheds light on the complex, interacting barriers impeding broad BIM adoption for WHS management. While earlier work [7] shows systematic empirical work leading to a list of factors, this study provides an emerging foundation where interrelationships between the barriers have been identified. For practice, our explanatory model paves the way for prioritising specific barriers because they cause, or at least exacerbate, others.

With the BIM and WHS management integration policy instruments framework, we now have an expanded language with theoretical constructs beyond the simplistic descriptions of ‘policy’ or ‘government’ that have been used previously. Figure 3 provides a richer conceptualisation that leads to a more finely grained and broader understanding of policy, policy instruments and relationships between and among them. Our findings introduce two new types of instruments: educational and innovation, which did not emerge from the literature. Our findings also show how instruments interact, which has important implications for practice: it suggests that informational instruments are critical, and instruments like market/economic tools, education tools and public sector client tools will have limited efficacy and will have little traction unless informational instruments conveying clear value propositions for BIM for WHS management are deployed.

The two explanatory models pave the way for many avenues for future work. Future research could expand the sites to include more states in Australia, where different jurisdictions’ stakeholders could have alternative views on policy instruments. This study could be repeated in different countries to evidence cross-country comparisons of successful government interventions. More empirical studies would likely identify new barriers and interrelationships (Figure 2) and an enriched suite of policy instruments and examples (Figure 3). Richer models can lead to validation studies, where industry practitioners and researchers come together to add “weights” to barriers and policies to convey each one’s relative urgency. Tools like Bayesian networks can be deployed to identify pathways for the most potent recommendations. Importantly, there is the possibility of integrating both figures, for example, mapping specific instruments to specific barriers, thus creating a new explanatory model that overarches both problems and solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Z.P., K.L. and J.E.O.; methodology, Z.P., K.L. and J.E.O.; formal analysis, J.E.O. and Z.P.; investigation, J.E.O., K.L. and Z.P.; writing— J.E.O., Z.P. and project administration, J.E.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The research team thanks the Centre for Healthy Sustainably Development and the Research and Innovation Office (Office of the Vice Chancellor) of Torrens University Australia, interview participants and focus group participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Table Showing a Sample Data Structure in Response to RQ 1

| Component of Figure 2 | Sample Quote (Evidence) | |

|---|---|---|

| Section 4.1.1. Typically no mandate for the use of BIM for WHS management | No industry-wide regulatory mandate; selected government agencies require BIM models through tendering/project management | I think the easy way for the government, that they can do is to mandate the BIM for work health and safety in public projects, in large scale infrastructure projects because they are often the major clients in the infra-structure, in the large public projects.—Interviewee 3 |

| Contract management governing BIM use tends to be weak | So, in that project we highlighted client leadership because subcontractors, contractors, they only care about what’s in the contract. And so if you as a client think about what you want and will need and can clarify that specifically in a contract, then you will achieve performance, or at least you still have to monitor and enforce performance through the contract. But that is a big part of setting the expectations and the communication clear.—Interviewee 1 | |

| Section 4.1.2. WHS management is not a priority, but a matter of compliance | --- | Back to what I said earlier, I think that work health and safety doesn’t have a very high profile. It’s seen as something that’s just a regulatory requirement. You need to keep the paperwork of it. You need to have your forms filled out and things like that, but it’s not necessarily something that you talk about, think about, I think maybe the people who are doing the work, like the workers you have, toolbox talks and things like that.—Interviewee 1 |

| Section 4.1.3. BIM/technology professions do not collaborate with WHS professionals | Significantly different mindsets between domains on health and safety vs. digital construction | …something that we found in our project was that the engineers and very high-tech people don’t necessarily think about work, health and safety and the work health and safety people which sits in another office in the same building are not very high-tech people. They like their handwritten forms, so they don’t speak to each other…—Interviewee 1 |

| Fragmentation across the industry | They like their handwritten forms, so they don’t speak to each other, they don’t collaborate much.—Interviewee 1 | |

| Section 4.1.4. Industry is resistant to technological change | Resistance of industry to change in general | People doesn’t [sic] want to change. I think that’s easy to understand. You know, people are used to the traditional approach to manage work health and safety. They don’t want to change.—Interviewee 3 |

| Opportunities afforded by technological innovations are not embraced | …things like modern manufacturing, you know, sort of. You know modular et cetera. Where does that fit in here? So going from construction to assembly is, so we’re now heading into with the housing price that we have, there’s going to be a larger focus on assembling, not just construction.—Focus Group participant 1 | |

| Lack of data literacy, in particular on the part of the WHS profession | …I think there is a lack of data literacy in our sector, I think. Like there’s a few observations that I found. There’s, it might be. I see when there’s a problem in especially in PMO type stuff, for us it could be workplace health and safety. The business identifies, I have a problem and then they go straight to what are the software vendors you know? Like they’ll come up with some basic requirements. Here’s what type of challenges we have, we want to manage safety better. We want to manage, you know, could be sustainability better or something and then they go straight so well, what are the software vendors have? And then they go get into that. What they don’t do is start more first principles of what are the processes that we have? How do we design the data that we’re going to need and then coming up with better requirements to then going to the software vendors or even building out, you know, sort of a collective solution that relies on BIM and other software as well. But that’s because there’s Just this lack of it’s either you know data literacy or even just enterprise architecture.—Interviewee 5 | |

| Section 4.1.5. Value proposition of BIM for WHS management is not convincing | Changes from BIM not seen as innovative | …a lot of the systems that have been developed have been like electronic conversions of former systems rather than like a revolution of the industry and coming up with new and innovative ways to do things they’ve been like just turning paper systems into electronic systems.—Interviewee 2 |

| Using BIM for WHS requires changes to processes | They’re trying to just electronically implement a system that is very similar to the former paper-based system and that may be because of familiarity or it might just be because of lack of creativity. That is leading to a lot of different products out there that are trying to solve these problem’, but they’re not, they’re not creative solutions and they’re just cluttered and difficult. And you know, I’ve worked on five or six projects that all had different electronic systems to try and manage their EHS and they’re not well refined. They’re not standardised, so maybe that is a key point. Like the lack of standardisation of EHS requirements might be a reason it’s not that more widespread.”—Interviewee 2 | |

| Lack of compelling evidence/case studies | I would love to see successful case studies in Australia and make it, I mean, why companies would like to use BIM and what would be the motivation? It’s always about the return on investment and if there are successful cases in Australia to share and promote to professional bodies. Some successful adoption of BIM and what is the return on investment or reduction in incidents or fatal accidents. So, some solid evidence to convince the industry this is the way to go. If you don’t join this journey, you left behind and kind of give them opportunity to see there are benefits. There are return on investment. Now we’re talking about health and safety then what is the number of reduction of incidents or improve in safety performance or it can be something like the leading indicators like culture. So the solid evidence to demonstrate the benefits, the return on investment either leading indicator or lagging indicator. Yes, she had a successful story around.—Interviewee 4 | |

| BIM is seen as costly; burden of costs needs to be shared | For the company, I need to know whether BIM could directly affect, improved work health and safety, and there is lack of evidence here. Lack of very well documented case studies. Up front cost and it’s the up-front cost is high, low standards and those that are all the possible barriers. I think financial constraints.—Interviewee 4 | |

| Section 4.1.6. No champions for the use of BIM for WHS management | Lack of collaboration between industry and government | …the top management, the senior management of the company, they must recognise the value of using BIM to improve work health and safety and then the top management can create culture of the organisation. What are the values that sit on top of the evidence when you have the value proposition.—Interviewee 1 We need to have a culture where people collaborate with each other and something that we highlight in our project, which is why I was really championing it was the role of leadership.—Interviewee 1 |

| Section 4.1.7. Lack of strong data infrastructure, data and system interoperability and a common data environment | --- | You know, using tools that are interoperable, that can easily share to produce the model because that’s something I think is not captured here. To ensure the interoperability of the data. Because you’ve got multiple stakeholders that will build this BIM for work, health and safety.—Focus Group Participant 2 |

References

- SafeWork Australia. Preliminary Work-Related Fatalities. 2022. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/data-and-research/work-related-fatalities/preliminary-work-related-fatalities (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Rafindadi, A.D.; Napiah, M.; Othman, I.; Mikik, M.; Haruna, A.; Alarifi, H.; Al-Ashmori, Y.Y. Analysis of the Causes and Preventive Measures of Fatal Fall-Related Accidents in the Construction Industry. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, B.; Hu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Chen, S.; He, W. Fatal Accident Patterns of Building Construction Activities in China. Saf. Sci. 2019, 111, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K. Integrating Building Information Modelling and Health and Safety Procurement. BIMSAFE NZ Report. 2023. Available online: https://safetycharter.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/BIMSafe-Report_procurement_V2.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Xu, S.; Ni, Q.; Du, Q. The Effectiveness of Virtual Reality in Safety Training: Measurement of Emotional Arousal with Electromyography. In Proceedings of the 36th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction (ISARC 2019), Banff, AB, Canada, 21–24 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Durdyev, S.; Ashour, M.; Connelly, S.; Mhdiyar, A. Barriers to the Implementation of Building Information Modelling (BIM) for Facility Management. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 46, 103736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, K.; Pablo, Z.; Kaur, G.; Vårhammar, A.; Zhang, P.; Feng, Y. Health and Safety Management Using Building Information Modelling: Phase One Report; NSW Government: Sydney, Australia, 2021. Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/309518 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- London, K.; Pablo, Z.; Feng, Y.; Rahnamayiezekavat, P.; Vårhammar, A.; Zhang, P. Health and Safety Management Using Building Information Modelling: Phase Two Report; NSW Government: Sydney, Australia, 2021. Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/312963 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Schulte, P.A.; Rinehart, R.; Okun, A.; Geraci, C.; Heidel, D. National Prevention through Design (PtD) Initiative. J. Saf. Res. 2008, 39, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, M.; Shafique, M.T. Evaluating 4D BIM and VR for Effective Safety Communication and Training: A Case Study of Multilingual Construction Job Site Crew Building. Buildings 2021, 11, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.; González García, M.; Martins, J. BIM for Safety: Applying Real-Time Monitoring Technologies to Prevent Falls from Height in Construction. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Ali, B.; Ullah, F.; Algabtani, F.K. Reducing Falls from Heights through BIM: A Dedicated System for Visualizing Safety Standards. Buildings 2023, 13, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, K.; Kaur, G.; Feng, Y.; Vårhammar, A.; Wallace, G.; Zhang, P.; Saha, S.; Rahnamayiezekavat, P. Construction Work Health and Safety Management Using Building Information Modelling. In Handbook of Research on Driving Transformational Change in the Digital Built Environment; Underwood, J., Shelbourn, M., Eds.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 91–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, L.H.; McCabe, B.; Shahi, A. The Benefits of and Barriers to BIM Adoption in Canada. In Proceedings of the 36th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction (ISARC 2019), Banff, AB, Canada, 21–24 May 2019; IAARC Publications: Oulu, Finland, 2019; pp. 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Babatunde, S.O.; Udeaja, C.; Adekunle, A.O. Barriers to BIM Implementation and Ways Forward to Improve Its Adoption in the Nigerian AEC Firms. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2021, 39, 48–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arotéia, A.V.; Freitas, R.C.; Melhado, S.B. Barriers to BIM Adoption in Brazil. Front. Built Environ. 2021, 7, 520154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, K.; Pablo, Z.; Feng, Y.; Rahnamayiezekavat, P.; Vårhammar, A.; Zhang, P. Health and Safety Management Using Building Information Modelling: Phase Three Report; NSW Government: Sydney, Australia, 2022. Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/316219 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Awwad, K.A.; Shibani, A.; Ghostin, M. Exploring the Critical Success Factors Influencing BIM Level 2 Implementation in the UK Construction Industry: The Case of SMEs. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2020, 22, 1894–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, W.I. Policy Analysis: A Political and Organizational Perspective; Martin Robertson: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Dye, T.R. Understanding Public Policy; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- José, G.V.H. Organic Production and Consumption Policies and Strategies. In Handbook of Research on Reinventing Economies and Organizations Following a Global Health Crisis; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 14–28. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342401446_Organic_Food_Production_and_Consumption_Policies_and_Strategies (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Bengtsson, M.; Hotta, Y.; Hayashi, S.; Akenji, L. Policy Tools for Sustainable Material Management Application in Asia. Institute for Global Environmental Strategies Report. 2010. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep00758.4 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Howlett, M. Designing Public Policies: Principles and Instruments, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IPBES. Policy Instruments. Available online: https://www.ipbes.net/policy-instruments (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Golzad, H.; Banihashemi, S.; Hon, C.; Drogemuller, R. BIM and Construction Health and Safety: Uncovering, Adoption and Implementation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Orlikowski, W.; Baroudi, J. Studying Information Technology in Organizations: Research Approaches and Assumptions. Inf. Syst. Res. 1991, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2012, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five Misunderstandings About Case Study Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doody, O.; Noonan, M. Preparing and Conducting Interviews to Collect Data. Nurse Res. 2013, 20, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Construction Work Done, Australia, Preliminary—September 2024. Reference Period September 2024. Released 27 November 2024. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/building-and-construction/construction-work-done-australia-preliminary/sep-2024 (accessed on 9 October 2025).