Abstract

As urban boundaries continue to expand and core city areas undergo optimization, megacities such as New York, London, Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou exert a siphon effect on surrounding regions, intensifying population concentration and land demand. However, the imperative for coordinated production-living-ecological space development has placed limits on uncontrolled urban sprawl, highlighting the need for connotative, high-quality urban growth. Recent initiatives in urban village renewal and regeneration aim to enhance land-use efficiency but face persistent challenges—including preserving indigenous settlements and cultural heritage, while creating livable and friendly communities within high-density contexts. Utilizing a mixed-methods approach—combining bibliometrics analysis, questionnaire surveys, and enterprise interviews—this research investigates core challenges to urban renewal. Results indicate that multi-party collaborative governance integrating policy innovation, cultural preservation, human-centered planning, smart technologies, and sustainable development is essential for advancing “people-industry-city integration” in renewal models.

1. Introduction

Amid the ongoing global wave of urbanization, hyper-dense development in megacities has become an irreversible trend. Back in the 1950s, New York City had already faced challenges between urban development and land constraints. After World War II, the U.S. government launched an unprecedented slum clearance program, aiming to revitalize urban development through the demolition and reconstruction of dilapidated areas in city centers [1,2,3,4]. Since the early 20th century, the United Kingdom has explored the nationalization of development rights and designed interest distribution mechanisms using planning management as a tool [5,6]. King’s Cross Station, located on the edge of central London, serves as a transportation gateway to London and the UK. Its regeneration represents one of the largest and most successful urban renewal practices in the UK over the past two decades. The British government established a collaborative model involving multiple stakeholders, including local governments, public sectors, communities, community volunteer organizations, and private enterprises, to achieve a balance of interests among various parties [7].

Similar to the development process of internationally developed cities. By 2024, China’s urbanization rate reached 67%, with Guangzhou—serving as a national central city—hosting a permanent population exceeding 18 million and an urbanization rate of 83% [8,9]. This rapid expansion has brought about a range of urban challenges, including spatial resource constraints, fragmented urban functions, and deteriorating residential environments [10,11]. Urban villages are distinctive features in the evolution of major southern Chinese cities such as Guangzhou. In the early stages of urban land development, the pragmatic approach adopted by southern regions avoided wholesale demolition, instead retaining traditional village settlements [12]. As urbanization progressed, these villages became embedded within metropolitan areas, forming unique spatial textures that blend traditional and modern elements. For example, Yuancun Village exemplifies the dichotomy of “interior modernity versus exterior disorder” while Shipai Village presents fire risks and the infamous “handshake buildings” characterized by dangerously narrow gaps between buildings [13,14,15,16,17]. Globally, the United Nations’ New Urban Agenda emphasizes the development of inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable communities [18]. Similarly, China’s 14th Five-Year Plan highlights the importance of urban renewal initiatives aimed at building livable cities [19,20]. The urbanization speed of Chinese cities has far exceeded that of major international cities in recent years. At this point in time, exploring livable renewal strategies in hyper-dense urban contexts like Guangzhou is critical—not only for the city’s own sustainable development but also as a reference for megacities worldwide.

International urban renewal theory has shifted from large-scale demolition to progressive, context-sensitive regeneration. Notably, the concept of “urban acupuncture,” which advocates for targeted interventions that catalyze systemic urban improvements, has gained traction in micro-regeneration practices, such as public space revitalization projects in Barcelona, Spain [21]. American scholar Jenny Roe proposed the Restorative Environments theory, establishing a framework for “restorative cities” that emphasizes promoting daily interaction between people and nature through urban design. For instance, embedding pocket parks and green corridors in dense urban areas, and ensuring residents have access to natural spaces within a 5-min walk [22,23]. Professor Timothy Beatley introduced the concept of “biophilic cities”, advocating for the deep integration of natural systems into urban structures, going beyond traditional greening approaches. By creating transitions between indoor and outdoor spaces, and applying vertical greening in high-rise buildings to simulate natural environments, the aim is to enhance the living experience in urban centers [24,25]. Internationally, interdisciplinary research on urban renewal and livable communities has primarily focused on areas such as policy discussions, community sustainable development, and neighborhood environmental planning. Over the years, research in this field has increasingly focused on smaller-scale spatial planning and has placed greater emphasis on addressing the specific needs of residents [26,27,28].

In China, scholars such as Zou Bing and Zhang Jingxiang have introduced the “inventory planning” theory, emphasizing functional enhancement over spatial expansion [29]. Local researchers in Guangzhou, by integrating site-specific practices, have proposed renewal strategies that integrate preservation, selective demolition, and renovation with micro-scale upgrades—a framework validated through culturally sensitive revitalization projects such as Yongqing Fang [30]. Despite these advancements, several critical gaps remain in the existing literature and practice. First, the lack of theoretical localization has limited the applicability of international models in the Guangzhou context. For instance, ancestral halls in Gangbei Village, which function as pivotal nodes of community identity, remain underexplored in systematic theoretical refinement [31]. Second, current research tends to isolate dimensions—focusing on ecological restoration or industrial upgrading—without addressing the integrated design of livable and inclusive communities, such as the spatial distribution of gender-sensitive amenities or intergenerational needs [32,33,34,35]. Third, innovation in governance mechanisms remains constrained. While models like Tangxia Village’s “public supervision” improve participation, they often still rely heavily on administrative oversight, limiting long-term governance sustainability [36]. Professor Guiwen Liu’s analysis of Shenzhen’s urban renewal policy illustrates the city’s adoption of tools such as “rule-based control” and “target-oriented planning” to regulate renewal practices [37]. Smart city pilot policies have likewise elevated renewal quality, spurring industrial upgrading, consumption growth, and comprehensive development by enhancing infrastructure, ecological assets, and cultural vitality [38].

In light of these dynamics, this study aims to develop a theoretical and practical model for livable and inclusive community renewal based on the data integrated from Guangzhou City. It addresses the following research questions: (1) What are the primary research hotspots in urban renewal and livable community development in highly urbanized cities? (2) How do local residents in a highly urbanized city like Guangzhou perceive and define the characteristics of a “livable community”? (3) How do policy mechanisms shape stakeholder roles during renewal, and what governance frameworks are necessary to balance competing interests? The search for answers to these questions is, in essence, a process of exploring the livable communities that people prefer. The development of such communities through urban renewal provides the spatial carrier for industrial growth and population aggregation, ultimately achieving the goal of “people-industry-city integration”.

2. Materials and Methods

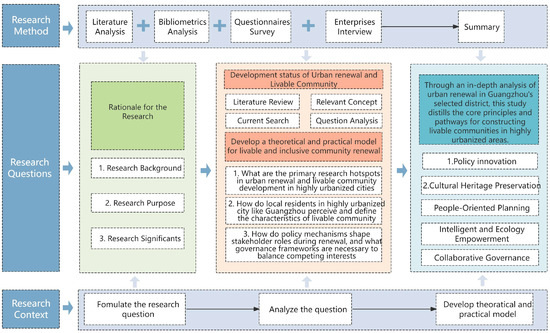

This study adopts a mixed-methods approach that integrates bibliometric analysis, questionnaire surveys, and interviews with urban renewal implementation enterprises to explore the primary challenges in implementing livable community renewal, as shown in Figure 1. “Research Questions and Methodology Alignment Flowchart”.

Figure 1.

Research Questions and Methodology Alignment Flowchart.

The research process comprised three key stages. Initially, the research scope was defined, and specific questions were formulated through a comprehensive review of the literature and a bibliometric analysis of the field. Subsequently, guided by the findings from the bibliometric analysis, a detailed survey questionnaire, including tailored questions for corporate participants, was developed. Finally, the collected data were systematically organized and analyzed to derive conclusions pertaining to the research questions.

2.1. Theoretical Research (Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis)

The bibliometric component utilizes data sourced from Web of Science and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) respectively, focusing on academic journal publications [39,40]. Multidimensional statistical and visualization processing of WOS and CNKI literature data was conducted by using the bibliometric analysis tool CiteSpace. Cross-analysis was performed on the “urban renewal” research theme under high urbanization and the “livable community” construction research field to identify hotspot research directions in China. The search strategy employed “Topic = Urban Renewal” AND “Topic = Livable”, with a time span of all years and source category of “All Journals”, retrieving data on 20 August 2025. To establish strict inclusion/exclusion screening criteria for the literature search, aiming to include high-quality core journal articles relevant to the topic and exclude repetitive, non-core, or low-quality literature. This process is crucial for ensuring the review is built upon a foundation of robust and relevant evidence.

Using the Web of Science Core Collection—a comprehensive database encompassing indices such as the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-Expanded)and the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), etc.—as the primary data source, a total of 50 relevant articles were retrieved.

Through searching the CNKI database, 880 articles were initially retrieved. After removing low-relevance publications such as conference information and review reports, a final set of 246 effective CNKI articles was identified as the analysis sample. Among these, 29 articles are high-quality publications, with source categories including Peking University Core Journals, Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI), Chinese Science Citation Database (CSCD) and World Journal of Citations Index (WJCI).

The article employs CiteSpace to summarize and organize the literature retrieved from the search. It is a widely used quantitative scientific analysis tool applied across multiple disciplines in recent years and is recognized as the most distinctive and influential knowledge mapping analysis instrument. It constructs multidimensional literature association networks [41]. The fundamental principle of knowledge mapping analysis involves measuring similarity and metrics among analytical units (e.g., scientific literature, keywords). By visualizing different types of scientific knowledge maps, this approach enables intuitive analysis of cross-correlations between literature and keywords, thereby identifying interdisciplinary content and critical research directions within relevant fields [42].

2.2. Field Research (Questionnaire Survey and Enterprise Interviews)

Extract appropriate content from the hotspots and keywords of bibliometric analysis to refine the design of the survey questionnaire and enterprise interview.

The rationale for adopting a questionnaire survey format is as follows [43]: (a) Breadth of Data Coverage and Efficiency. Questionnaire surveys rapidly acquire large-scale sample data through standardized tools, particularly in research contexts requiring quantitative statistics. Closed-ended questions precisely measure variable relationships (e.g., regression analysis of satisfaction and behavioral tendencies), while open-ended questions offer qualitative supplementation for exploratory research. (b) Standardized Procedures Ensure Objectivity. Questionnaires are designed to be purposeful, logically structured, and linguistically neutral. Pretesting eliminates ambiguous wording and reduces respondent bias. Structured data facilitates cross-database comparisons, enhancing conclusion generalizability. (c) Support for Theoretical Validation and Model Construction. Quantitative responses can be used for model validation using methods such as path analysis and factor analysis. Visualization tools assist in mapping the distribution of key variables. The survey sampled residents in Guangzhou’s urban villages. A total of 130 valid responses were collected via stratified random sampling across multiple villages to ensure demographic representativeness across gender, age, occupation, and household income. Fieldwork was conducted from 14 April to 20 April 2025, with data collection focused on high-traffic areas to enhance response rates and data completeness. Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were employed to interpret villagers’ expectations and demands for livable communities in urban renewal practices.

The enterprise symposium segment selected three representative urban village regeneration projects currently underway, inviting corporate executives, project leaders, and local villagers involved in the regeneration initiatives as ees. Centered on the theme “Urban Renewal and Livable Community Construction,” the symposium adopted a semi-structured format. Discussions addressed preset topics—including policy awareness, residential preferences and design priorities —but also allowed for dynamic questioning based on real-time participant responses. All discussions were transcribed verbatim. Key demands and recurring issues were identified and coded, forming the basis for thematic analysis. By triangulating the qualitative findings from the symposiums with the quantitative results from the surveys, the study provides a multidimensional understanding of the mechanisms shaping community-building efforts in urban village contexts.

The integration of questionnaire and symposium methods enables the study to capture both macro-level patterns and micro-level mechanisms. While quantitative analysis reveals generalizable trends, qualitative insights illuminate the nuanced dynamics of implementation. This mixed-methods design enhances the academic rigor of the study while simultaneously increasing its policy relevance and practical applicability.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of CNKI Literature Clustering Results

3.1.1. Data Source Analysis

- Temporal Distribution Analysis

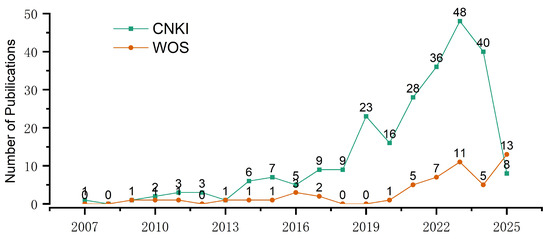

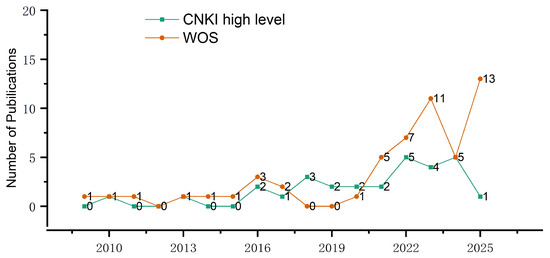

In academic research, the quantity and temporal distribution of publications serve as key indicators for assessing research interest in a specific field. The set of 50 high-quality papers from the Web of Science core collection includes 38 papers on “Urban Renewal” that contain the phrase “Livable Community” and 12 papers on the same topic that contain the phrase “Livability”. Based on 246 journal articles retrieved from the CNKI database under the combined topics of “urban renewal” and “livable community” (Figure 2), the emergence of livability-related urban renewal studies in China can be traced back to 2007. Prior to 2018, the publication volume remained relatively low. However, a significant increase occurred after 2019, with sustained growth through 2022. The period 2019–2022 saw accelerated growth, peaking at 48 articles in 2023, indicating rising scholarly interest. As of the current study (mid-2025), 8 relevant articles have been published this year. High-quality publications (29 high-quality papers derived from CNKI, Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index, Peking University Core, Chinese Science Citation Database and World Journal of Citations Index) emerged in 2013, reaching a peak in 2022 (5 articles), aligning with overall publication trends (Figure 3). In terms of quantity, the total number of documents in WOS is lower than that in CNKI, but in terms of quality, papers in the WOS are generally considered better than those in the CNKI.

Figure 2.

Number of publications (50 papers from WOS and 246 papers from CNKI) from 2007 to 2025.

Figure 3.

Number of publications (50 papers from WOS and 29 high-level papers from CNKI) from 2007 to 2025.

After an overlapping check of the relevant literature in WOS and CNKI, no duplicate articles were identified among the valid publications.

- 2.

- Distribution of Scientific Fields and Research Topics

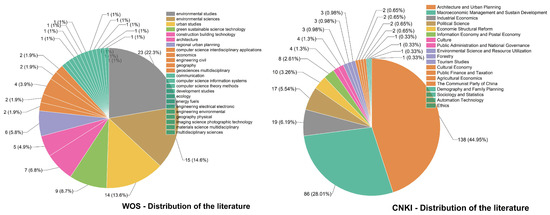

The distribution of scientific fields and research topics can be identified through statistical analysis of the literature’s disciplinary distribution. In the Web of Science, Environmental Studies and Environmental Science account for 22.3% and 14.6% respectively, with the combined total of environment-related research reaching 36.9%. This is followed by Urban Studies at 13%. The fourth and fifth areas are Construction Sustainable Science Technology and Construction Building Technology, primarily focusing on research on construction techniques. The 246 articles obtained from CNKI demonstrate a broad disciplinary distribution for research on “urban renewal” and “livable communities” (Figure 4). Among these, papers in the field of Architectural and Urban Planning were the most numerous, accounting for 44.95% of the total, which is directly related to the nature of urban renewal. This was followed by Macroeconomic Management and Sustainable Development (28.01%). Together, these two disciplines accounted for over 70% of the papers. The distribution of the top two disciplines among the 29 high-quality CNKI papers remains the same, accounting for 46.34% and 14.63% respectively.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the literature in subject areas involved in “Urban Renewal” and “Livable Communities” (WOS and CNKI database).

3.1.2. Analysis of Research Hotspots and Frontiers

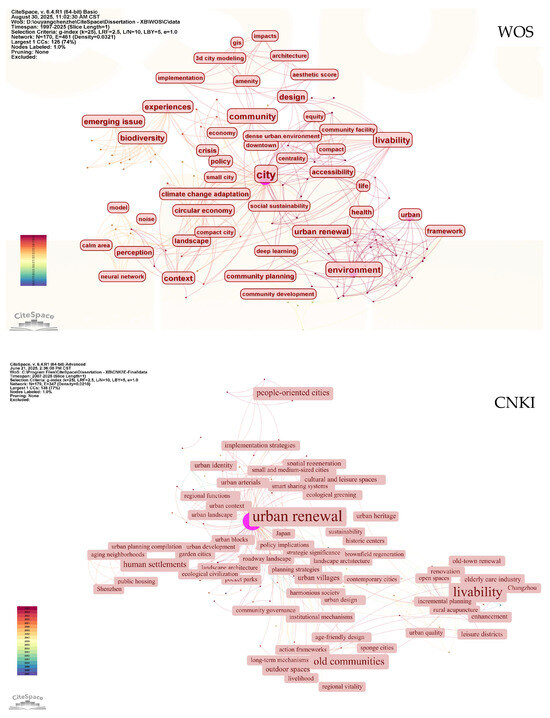

Using CiteSpace, we conducted a quantitative analysis of the 50 sample articles from WOS and 246 sample articles from CNKI, including network visualization and high-frequency keyword analysis, overlay visualization, and research focus identification. Research hotspots were identified through keyword co-occurrence, timeline clustering, and keyword burst detection.

- Network Visualization

In the Web of Science database, the terms “City” and “Urban Renewal” occupy the largest nodes, with 9 literature samples each focusing on these two fields. The topic of “Environment” has 5 research papers, followed by key keywords such as “Design,” “deep learning,” “livability,” and “accessibility.” Keyword analysis indicates that international literature similarly prioritizes the optimization of living environments, with cutting-edge research integrating modern deep learning techniques alongside traditional studies

In the CNKI database, “urban renewal” and “livability” occupy the largest nodes, while themes such as “old communities,” “human settlements,” and “people-oriented cities” also represent research hotspots. Among the 246 articles, 54 involve the “urban renewal” keyword, and 15 involve the “livability” keyword. Keywords closely associated with “urban renewal” include “urban villages,” “urban heritage,” “landscape architecture,” “sustainability,” “historic centers,” “contemporary cities,” and “brownfield regeneration.” Keywords linking “livability” and “old communities” include “outdoor spaces,” “renovation,” and “enhancement.” Distinct research directions under the “livability” domain include “old-town renewal,” “leisure districts,” “elderly care industry,” and “rural acupuncture,” as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Network visualization of keywords for “Urban Renewal” and “Livable Communities” from 2007 to 2025, created by CiteSpace (WOS and CNKI database).

- 2.

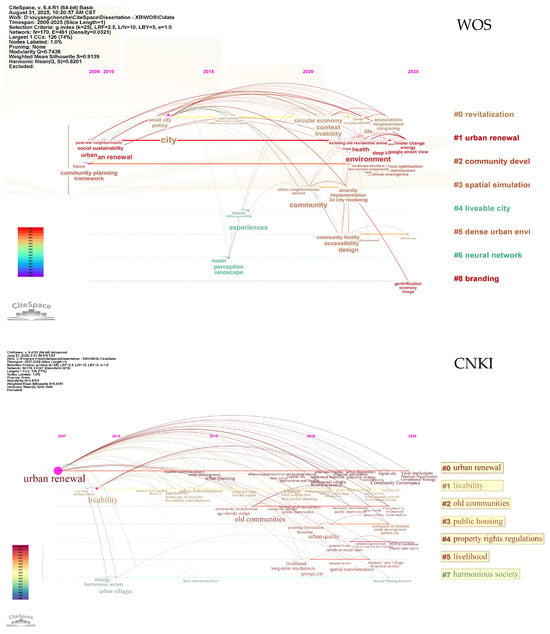

- Thematic Clustering Analysis

Through Citespace, a thematic clustering analysis of keywords related to “urban renewal” and “livable” communities identified 8 primary research domains in WOS and 12 in CNKI. The international research hotspots, ranked in descending order of intensity, are as follows: “Politics,” “Sustainable community development,” “Neighborhood planning,” “Residential history,” “Vegetated roof,” “Community facility,” “Waterfront,” and “Helsinki.” In China, the order of research priorities shifts to: “urban renewal,” “livability,” “old residential communities,” “urban quality,” “public housing,” “livelihood,” “life circle,” “property rights regulations,” “harmonious society,” “pocket parks,” “urban context,” and “urban landscape”. The analysis reveals that in the renewal of old residential communities and urban villages, factors influencing community livability primarily comprise two key dimensions: physical infrastructure (e.g., public housing, urban landscape, pocket parks) and socio-cultural policies (e.g., property rights regulations for resettlement housing, community life circles, and urban quality enhancement). These dimensions constitute major research areas affecting the livability of urban renewal communities, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Keyword Clustering Visualization of “Urban Renewal” and “Livable Communities” from 2007 to 2025, created by CiteSpace (WOS and CNKI database).

- 3.

- Timeline Clustering and Keyword Burst Analysis

Thematic clustering and chronological sorting of the literature are presented in Figure 7. Internationally, in 2009 William M. Rohe traced the history of neighborhood planning in the United States to draw lessons from past experiences and identify its contributions to the planning profession. The study indicates that neighborhood planning programs have made several important contributions to the planning profession, including focusing attention on how neighborhood design influences urban livability and social behaviors, institutionalizing citizen participation in plan making, and addressing issues beyond physical development to encompass social, economic, political, and environmental dimensions [44]. Since 2025, the concept of “community” has gradually been emphasized by scholars, and from 2022 to the present, research in the field of “urban renewal” has increasingly shifted its focus toward “Environment” and “Health”.

Figure 7.

Timeline Clustering and Burst Detection of “Urban Renewal” and “Livable Communities” Keywords from 2007 to 2025, created by CiteSpace (WOS and CNKI database).

In China, research on “urban renewal” was initiated in 2007 with Gera, Germany, as a case study. This pioneering work introduced the concept of “innovative urban vitality-centered renewal planning for central urban areas” to address challenges such as population decline, sustained economic recession, and rising unemployment during the city’s post-industrial transition [45]. Consequently, strategies including “building livable cities,” “developing mixed-use spaces,” and “improving transportation systems” were implemented locally to revitalize the inner city. Subsequently, between 2009 and 2010, research focus on “livability” in urban communities expanded. Specifically, Chongqing, China, drew upon post-World War II urban renewal experiences in the United States to analyze the strategic significance of its “Livable Chongqing” initiative for tackling challenges associated with rapid urbanization [46]. Studies on “urban villages” emerged in 2010. By 2015, however, the academic focus had shifted from “urban village redevelopment” towards “old-town renewal” and “old residential community renovation”. This shift prioritized residents’ lived experiences, leading to interventions such as public space renovation, landscape enhancement, and sponge city development to enhance livability [47,48,49]. Currently (since 2024), research hotspots concentrate on digital cities, community governance, ecological civilization, and planning coordination [50,51].

3.2. Analysis of Questionnaire Conclusion

3.2.1. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

Based on the analysis of the research fields on “urban renewal” and “livability”, indicated in Section 3.1.2, neighborhood environment and community supporting facilities are a hot area of research. This study meticulously designed a survey questionnaire to comprehensively and quantitatively understand villagers’ demands regarding relocation housing, especially the environment and supporting facilities of the re-settled communities, thereby enabling the accurate acquisition of information on villagers’ demands.

- 1.

- Survey Procedure

- (1)

- Pre-survey Preparation

By interviewing community workers and village representatives, the core demand dimensions (including housing security, community facilities, and living convenience) were identified. Based on this, an accessible questionnaire was designed, consisting of 18 specific questions covering four key dimensions: basic information, intentions and demands regarding relocation housing, specific demands for supporting facilities in resettlement communities, and traditional buildings. The overall design of the questionnaire questions is based on the core topics extracted from the literature review, combined with policy regulations and regional data, to fully ensure the scientificity and pertinence of the questionnaire. The questionnaire mainly adopts multiple-choice questions, supplemented by open-ended questions. The research team trained volunteers proficient in the local dialect to serve as investigators and prepared paper questionnaires. The four key dimensions are as follows:

① Basic Information (Q1–Q4): Questions are designed with reference to the norms of demographic surveys and the characteristics of residents in Huangpu District, providing variables for the analysis of group differences.

② Intentions Regarding Relocation Housing (Q5–Q10): Based on the conclusion that “livability evaluation should cover housing area, density, and delivery standards” from relevant studies in An Introduction to the Science of Human Settlements, and combined with the standard of relocation housing units in Huangpu District, it is ensured that the questions are in line with the core dimensions of residential needs.

③ Community Supporting Facilities (Q11–Q17): According to the relevant policies in the “Opinions on Further Promoting the Construction of Smart Communities” issued by the state, the conclusions that “education/medical care/transportation are the most concerned supporting facilities of resettled residents” and “the demand for security-related intelligent services is prominent” are summarized. With reference to relevant national construction standards, questions are designed targeting the shortcomings of supporting facilities in Huangpu District.

④ Traditional Buildings (Q18): Based on the conclusion from the literature review that “the on-site preservation of ancestral halls is likely to enhance community belonging” (e.g., Study on the Protection of Ancestral Halls in Guangzhou’s Urban Villages), and combined with the guidelines for the protection of traditional buildings, three options for reconstruction models are set to connect the research objectives of cultural inheritance and livability.

- (2)

- Data Collection

A combination of “centralized offline questionnaire completion (conducted at community activity centers to cover most villagers)” and “home-based assistance (for the elderly and people with mobility impairments)” was adopted. The survey was carried out on weekends during villagers’ free time. The completeness of questionnaires was checked on-site, and invalid samples (e.g., those with identical answers for all questions or incorrect information) were excluded.

- (3)

- Data Analysis

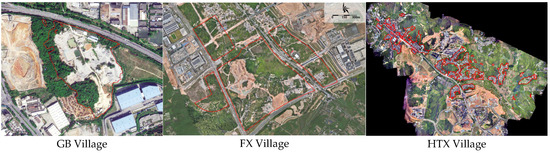

Data were entered into Excel and stratified by “age, annual household income, and occupation”. Quantitative statistics were conducted on the frequency of villagers’ demands. The boundaries of the surveyed village are illustrated in Figure 8 below.

Figure 8.

Aerial photograph of investigated village (Red zone represents the original village area).

- 2.

- Selection of Participants

- (1)

- Sampling Method

The method of “stratified random sampling + supplementary sampling for special groups” was adopted, with the list of resettled villagers in the community as the sampling frame. A total of 500 households were selected as samples, accounting for 6.74% of the total number of households. All participants voluntarily signed the consent form after fully understanding the research purpose, data usage, and privacy protection measures. They retain the right to withdraw from the survey at any time without any impact. Additionally, an informed consent statement page has been added at the beginning of the questionnaire to ensure that every respondent confirms their understanding before proceeding.

- (2)

- Stratification Dimensions

Stratification was conducted by “gender, age, and occupation”, and the number of samples for each stratum was allocated according to the proportion of the stratum in the total population. The total number of households in GB Village, FX Village, and HTX Village was 7415, with a total population of 17,244 as shown in Table 1. In this survey, 500 questionnaires were distributed, and 452 valid questionnaires were recovered, with an effective recovery rate of 90.4%. The sample selection fully considered the characteristics of different groups, ensuring broad representativeness. Specifically, males accounted for 51.33% and females for 48.67%; villagers aged 56 and above accounted for 24.78%, while middle-aged and young villagers (26–55 years old) accounted for 64.16%; private business owners accounted for 25.66%, corporate white-collar workers for 24.78%, and freelancers for 18.81%; households with an annual income of 100,000–250,000 RMB accounted for 45.13%, and those with an annual income of 250,000–400,000 RMB accounted for 32.30%. This diverse sample structure provides a solid data foundation for subsequent analysis and can effectively reflect the real needs of different groups. The data is summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Registered Population of investigated villages.

Table 2.

Population Statistics of investigated villages. Quantity Distribution of Samples Across Various Characteristic Dimensions.

- (3)

- Special Treatments

If the number of samples for “elderly people living alone” or “people with mobility impairments” was insufficient in random sampling, supplementary samples were selected directly from the community’s special list to ensure the representativeness of these groups. Only one “family member knowledgeable about the household’s housing-related matters” was selected per household to participate in the survey, and non-resettled villagers were excluded.

The samples are distributed across key dimensions such as gender, age, occupation, and income, and the proportion of each group is basically consistent with the actual composition characteristics of rural relocated villagers (for example, the high proportion of middle-aged and elderly people, and the diversity of occupation types), which reflects the coverage of villagers with different characteristics.

The high-proportion groups (such as villagers over 56 years old and families with an income of 100,000–250,000 yuan) reflect the main groups concerned about relocation demands, while the inclusion of low-proportion groups (such as those under 25 years old and with an income of over 400,000 yuan) avoids the simplification of samples and further enhances representativeness.

It can be intuitively seen from the table that the sample structure takes into account the characteristic differences of different groups, can relatively comprehensively reflect the overall demands of villagers, and provides support for the reliability of the research conclusions.

3.2.2. Analysis of Survey Results

- 1.

- Analysis of Intentions and Demand Preferences for Relocation Housing

- (1)

- House Type Selection Tendency

Survey data shows that house type selection exhibits a clear trend toward larger sizes. 43.81% of villagers prefer larger-sized apartments of 120–150 square meters, and 18.81% favor large-sized apartments of over 150 square meters as shown in Figure 9. Combined with data, it can be seen that villagers’ preference for large-sized apartments mainly stems from practical needs such as “dual balconies in large apartments” and “separate living spaces”. As family structures evolve, multi-generational cohabitation remains common, and large-sized apartments better accommodate the need for independent living spaces for family members. The dual-balcony design aligns with villagers’ expectations for functional zoning (e.g., laundry drying and leisure areas). Further cross-analysis reveals a significant correlation between annual household income and house type selection. The proportion of groups with an annual household income of over 250,000 RMB choosing large-sized apartments reaches 86.99%, significantly higher than 37.24% of low-income groups. This indicates that economic capability is a key factor influencing house type selection: high-income families prioritize living quality and spatial experience, while low-income families tend to favor practical and cost-effective house types due to economic pressures.

Figure 9.

Data Table on Selection Tendency of preferred Housing Unit Sizes & Correlation Analysis between Housing Size Preferences and Annual Household Income.

To quantify the intensity of the aforementioned influencing factors, a multiple linear regression model was constructed with “house type preference” as the dependent variable (1 = 50–80 m2, 2 = 81–120 m2, 3 = 121–150 m2, 4 = >150 m2) and “annual household income (X1)”, “family structure (X2)”, “age (X3)”, and “gender (X4)” as independent variables. The results show that the model is overall significant (F = 28.63, p < 0.001), with key influencing factors as follows:

The regression coefficient of annual household income (X1) is β = 0.82 (p < 0.001), meaning that for each level increase in annual income (e.g., from 100,000–250,000 RMB to 250,000–400,000 RMB), villagers’ tendency to choose large-sized apartments increases by 0.82 units, making it the most critical influencing factor.

The regression coefficient for multi-generational families (X2 = 2) is β = 0.56 (p < 0.001), indicating that their probability of choosing large-sized apartments is 0.56 units higher than that of nuclear families, verifying the rationality of “family structure affecting spatial needs”.

Age (X3) has a weak impact (β = 0.19, p = 0.032), while gender (X4) has no significant effect (β = 0.08, p = 0.358).

This result, supported by statistical tests, explicitly rules out the possibility that the “correlation between income and house type” is a random phenomenon, further confirming that economic capability and family structure are the core mechanisms driving the preference for large-sized apartments.

- (2)

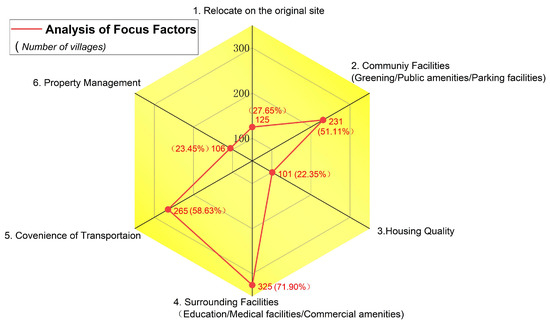

- Analysis of Focus Factors

Regarding the factors of concern for relocation housing, surrounding facilities (educational/medical/commercial) topped the list with a concern rate of 71.90%, followed by convenience of transportation at 58.63%, and community facilities (greening/public amenities/parking) at 51.11% as shown in Figure 10. The highest concern for surrounding facilities reflects villagers’ strong emphasis on life convenience and public resources. High-quality educational resources ensure children’s learning and growth, comprehensive medical facilities meet healthcare needs, and convenient commercial supporting facilities enhance daily living satisfaction. The high attention to community facilities demonstrates villagers’ pursuit of living environment quality. Good greening and public facilities provide villagers with comfortable leisure spaces, while sufficient parking spaces solve the problem of vehicle parking. Traffic convenience is also highly valued: convenient transportation can shorten villagers’ commuting time, improve travel efficiency, and strengthen connections with the outside world.

Figure 10.

Factors Influencing Preferences for Relocation Housing.

- (3)

- Parking Space Demand

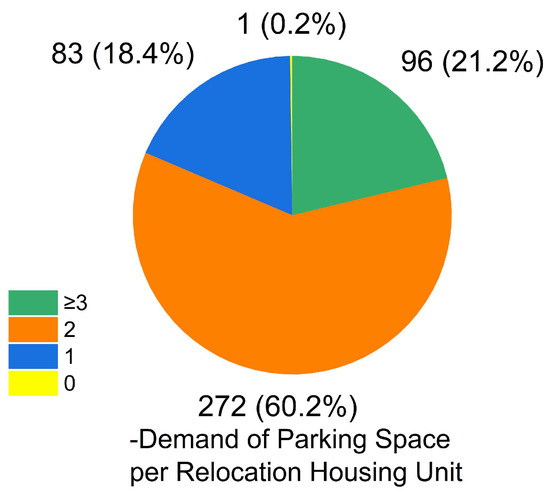

The data on parking space demand for each relocation housing unit shows that 60.18% of villagers prefer allocating two parking spaces as shown in Figure 11. This aligns with the trend of increasing household car ownership. As living standards improve, many families own more than one vehicle. Providing two parking spaces better accommodates household parking needs, avoiding problems such as a lack of parking spaces, random parking, and ensuring orderly community parking management and residents’ daily convenience.

Figure 11.

Parking Space Demand per Relocation Housing Unit.

To verify the predictive role of “household car ownership, income, and house type” on parking space demand, a binary logistic regression model was constructed with “demand for 2 parking spaces” as the dependent variable (1 = yes, 0 = no). The model exhibits good goodness-of-fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow test χ2 = 6.28, p = 0.61) and strong explanatory power (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.58). The results show:

When household car ownership is 2 or more, the odds ratio (OR) for demanding 2 parking spaces is 5.83 (p < 0.001), meaning that such families are 5.83 times more likely to demand 2 parking spaces than families with no cars.

Groups with an annual income of over 250,000 RMB (OR = 2.31, p < 0.001) and villagers choosing large-sized apartments (OR = 1.79, p = 0.001) are also significantly more likely to demand 2 parking spaces.

This result quantifies the conclusion that “car ownership is the core driving factor for parking space demand” and provides a statistical basis for planning “120–150 parking spaces per 100 households” in resettlement communities.

- 2.

- Priority of Supporting Facilities Demand in Relocation Communities

- (1)

- Analysis of Public Facilities Demand

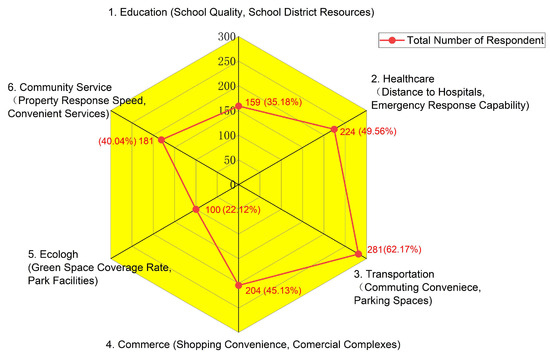

Survey data on the degree of concern for supporting facilities shows that villagers’ demand priorities are sequentially transportation (commuting convenience, parking spaces) (62.17%), medical care (distance to hospitals, emergency response capability) (49.56%), commerce (shopping convenience, commercial complexes) (45.13%), and community services (property response speed, convenient services) (40.04%), which is consistent with the conclusion from s that “improvement of public facilities is the primary demand of villagers.” See Figure 12 for details. Transportation demand ranks first, highlighting its importance for villagers’ daily lives, regional economic development, and access to employment opportunities; medical care demand follows closely, reflecting villagers’ urgent need for health protection for themselves and their families; high commercial demand reflects villagers’ expectations to meet diversified consumption needs and improve quality of life; although community service has relatively lower concern, it is still valued by nearly half of the villagers, indicating that efficient community services are important factors for enhancing residents’ life happiness.

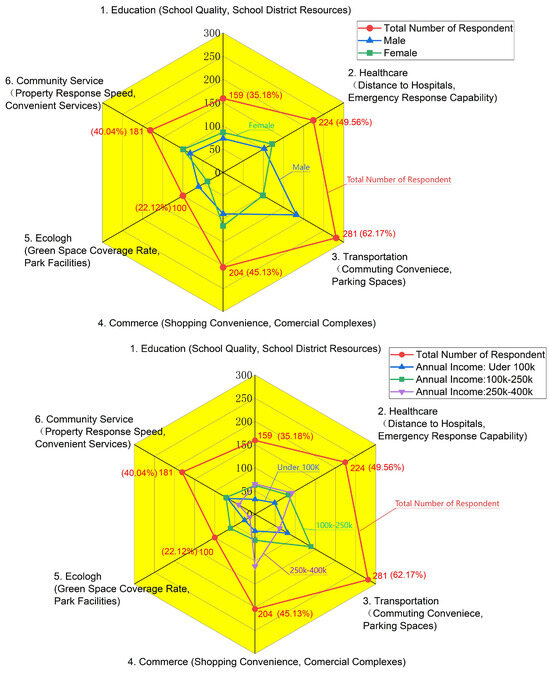

Figure 12.

Priority of Public Facility Demands for Relocation Housing.

Cross-analysis reveals that facility preferences are influenced by gender and annual household income. In terms of gender differences, males show greater concern for transportation (commuting convenience, parking spaces) and medical care (distance to hospitals, emergency response capability), while females have higher demands for medical care (distance to hospitals, emergency response capability)and commerce (shopping convenience, commercial complexes). This divergence may stem from variations in social role division and living habits: males may assume more responsibilities for family travel and work commuting, hence a greater focus on transportation; females, undertaking more tasks such as family health care and daily shopping, show stronger demands for medical care and commerce. In terms of annual household income differences, groups with an annual income of 250,000 RMB and below pay more attention to transportation (commuting convenience, parking spaces), while those with an income of 250,000–400,000 RMB prioritize commerce (shopping convenience, commercial complexes), followed by medical care (distance to hospitals, emergency response capability). Due to economic constraints, low-income groups expect convenient transportation to reduce travel costs and access more employment opportunities; middle-to-high-income groups, after meeting basic living needs, pursue quality of life improvement through commercial consumption while also emphasizing medical security. A detail comparison is presented in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Correlation Analysis Between Public Facility Demands for Relocation Housing and Gender, Household Annual Income.

The current analysis lists demand for public facilities, intelligent services, and age-specific facilities separately. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and one-way ANOVA) can extract latent “demand dimensions” from scattered facility demands, clarifying the core demand structure.

① Exploratory Factor Analysis (Extracting Latent Demand Dimensions)

To clarify the internal structure of villagers’ supporting facility demands, exploratory factor analysis was conducted on 12 specific demands (e.g., transportation, medical care, commerce, visitor systems, barrier-free facilities, high-quality schools). The results show that KMO = 0.82 (>0.7) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity χ2 = 1256.37 (p < 0.001), indicating the data is suitable for factor analysis. Using the criterion of eigenvalue > 1, 3 latent factors were extracted, explaining 76.8% of the total variance:

Factor 1: Basic Life Support (variance explanation rate: 38.2%): Loads transportation, medical care, and commerce demands with factor loadings of 0.85–0.92, indicating these three types of demands are the core of villagers’ supporting facility needs and confirming the descriptive conclusion that “transportation and medical care are the top priorities”;

Factor 2: Safety and Intelligence (variance explanation rate: 22.5%): Loads visitor systems, parking management, and access control demands with factor loadings of 0.79–0.88, reflecting villagers’ emphasis on community safety and convenient management;

Factor 3: Demographic-Specific Care (variance explanation rate: 16.1%): Loads barrier-free facilities and high-quality school demands with factor loadings of 0.76–0.83, embodying attention to the needs of specific groups (the elderly, children).

② One-Way ANOVA (Verifying Significance of Differences Between Income Groups)

A one-way ANOVA was conducted with “demand for high-end leisure facilities (swimming pools/gyms)” as the dependent variable and “income group” as the independent variable. The results show significant differences between groups (F = 42.89, p < 0.001): the average demand score of the group with an annual income of over 250,000 RMB is 4.07 (on a 1–5 Likert scale), significantly higher than the 2.13 of the group with an annual income of 250,000 RMB or below (LSD post hoc test p < 0.001). This result rules out the possibility that the “correlation between income and demand for high-end facilities” is a random proportional difference, clearly confirming the restrictive effect of economic capability on demands for quality-of-life facilities.

- (2)

- Analysis of Community Management Demand

Villagers’ demand for community management is ranked as property services (75.66%), community sanitation environment (51.99%), and community greening environment (51.33%) as shown in Figure 14 below. The high concern for property services reflects villagers’ urgent need for good community management services, while greening and sanitation environments directly affect living comfort and health.

Figure 14.

Priority of Community Management Demands for Relocation Housing.

- (3)

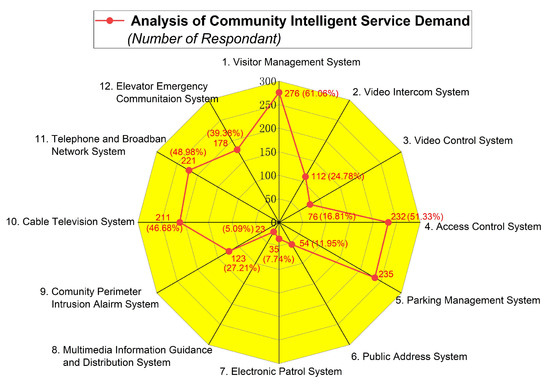

- Analysis of Community Intelligent Service Demand

In the ranking of community intelligent service demands, visitor management systems (61.06%) are tied for first place, followed by parking management systems (51.99%) in second place, and entrance management systems (access control) (51.33%) in third place as shown in Figure 15. With the development of technology, villagers’ demand for intelligent services has gradually increased, reflecting their emphasis on convenient communication, safety management, and community order, as well as the impact of technological development on villagers’ living needs.

Figure 15.

Priority of Intelligentization Demands for Relocation Housing Communities.

- (4)

- Analysis of Future Supporting Facilities Demand

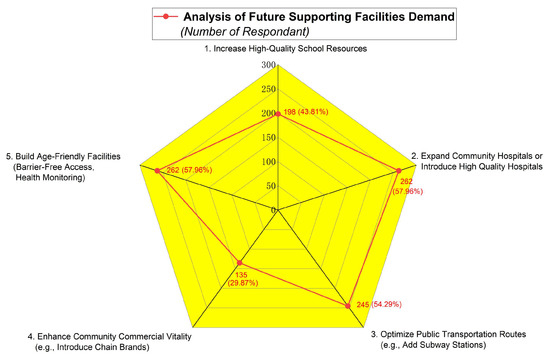

With regard to future supporting facilities demand, aging-friendly facilities (barrier-free access, health monitoring) (57.96%), expansion of community hospitals or introduction of Class-A tertiary hospitals (57.96%), and optimization of public transportation routes (such as adding subway stations) (54.20%) rank among the top as shown in Figure 16. This indicates that villagers have a strong desire to improve their living environment and enhance the level of public services. The high demand for aging-friendly facilities is related to the trend of population aging, reflecting villagers’ emphasis on the living convenience and health protection of the elderly. Expanding community hospitals or introducing Class-A tertiary hospitals can effectively solve the problem of difficult access to medical care, while optimizing public transportation further enhances commuting convenience.

Figure 16.

Priority of Future Supporting Facilities Requirements for Relocation Housing.

In terms of occupational differences, private business owners and freelancers prioritize aging-friendly facilities (barrier-free access, health monitoring) (76.19%), while corporate white-collar workers focus primarily on enhancing commercial vitality (e.g., introducing chain brands) (70.59%). Civil servants, however, place the highest emphasis on expanding high-quality educational resources and community hospitals or introducing internationally certified hospitals (100%). Based on their own work and life characteristics, different occupational groups have different focuses on future supporting facilities construction.

- (5)

- Analysis of Age-Specific Facility Demand

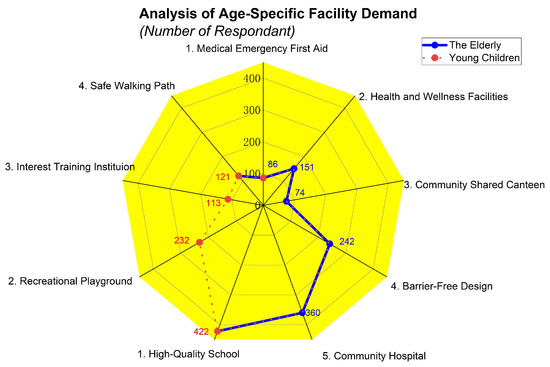

The demands of the elderly population focus on community hospitals (family doctors, health consultation, health care) (79.65%), barrier-free design (53.54%), and health care facilities (33.41%). This indicates that the elderly have extremely high demands for medical care and living convenience. Community hospitals and barrier-free design can provide convenient medical services and a safe living environment for the elderly, while health care facilities help improve their quality of life.

The demands of children mainly include high-quality schools (93.36%), playgrounds (51.33%), safe walking paths (26.77%), and interest training institutions (25.00%). This shows that parents attach great importance to their children’s education, with high-quality schools being the primary need. Safe walking paths and playgrounds ensure children’s travel safety and entertainment needs, while interest training institutions meet their diversified development requirements. The detailed data is shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Priority of Supporting Facilities Demands for Aging and Child Population.

To quantify the correlation intensity between age and facility demands, Pearson correlation coefficients between “age” and core facility demands were calculated:

The correlation coefficient between age and demand for medical facilities is r = 0.68 (p < 0.001), and between age and demand for barrier-free facilities is r = 0.72 (p < 0.001), both indicating a strong positive correlation. The correlation coefficient between age and demand for intelligent services is r = −0.53 (p < 0.001), indicating a strong negative correlation.

This result statistically confirms the regularity of “demand differences caused by age” rather than random phenomena, providing a precise basis for “demographic-specific facility configuration” in resettlement communities (e.g., adding barrier-free access in elderly areas and optimizing walking safety in children’s areas).

- (6)

- Villagers’ Daily Community Cultural Activities

52.88% of villagers reported no regular community cultural activities, while 34.96% participated in sports activities (e.g., square dancing, ball games), indicating that villagers’ cultural life is relatively scarce and targeted activities are needed to enrich their spiritual lives.

- 3.

- Renovation Approaches for Traditional Architecture (e.g., Ancestral Halls)

Ancestral Halls, also known as lineage temples, are an iconic architectural carrier in traditional Chinese culture. It serves as the core venue for clan members to worship ancestors and consolidate family ties, bearing the important mission of “remembering ancestors and honoring traditions” as well as inheriting clan culture. From the Eastern Han stone shrine at Xiaotang Mountain to the Lingnan ancestral hall complex of the Ming and Qing dynasties, these buildings typically feature an axisymmetric layout and exquisite craftsmanship like “three carvings and two sculptures”, embodying regional cultural characteristics. Refer to Figure 18 for the on-site phots of modern Chinese ancestral hall.

Figure 18.

On-site photos of Ancestral Hall.

94.03% of villagers support preserving ancestral halls and other traditional buildings at their original sites, while only 4.87% endorse reconstruction on-site. This reflects villagers’ deep emotional attachment to traditional culture and strong commitment to its continuity. Urban renewal initiatives must prioritize community consensus to ensure effective protection and transmission of cultural heritage.

To verify whether villagers’ preference for “on-site preservation” is statistically significant, a binomial test was conducted with “support for on-site preservation = 1, others = 0”. The null hypothesis H0 is “support rate p = 0.5 (random preference)”, and the alternative hypothesis H1 is “p > 0.5”. The results show z = 29.76 (p < 0.001), rejecting the null hypothesis, indicating that the 94.03% support rate is not a random result but a high-level consensus among villagers. This conclusion provides rigorous statistical support for the “on-site preservation of ancestral halls” policy in urban renewal, avoiding decision-making based on subjective judgment.

- 4.

- Cross-Analysis of Demand Influencing Factors

Combined with the results of the aforementioned multiple regression, ANOVA, and correlation analysis, the mechanism of action of demand-influencing factors can be further clarified:

- (1)

- Income (economic constraints) and family structure (spatial needs) are the core driving factors for “hard needs” such as house type and parking space, and their influence intensity can be quantified through regression coefficients (e.g., β = 0.82 for the impact of income on house type preference);

- (2)

- Age (physiological conditions and living habits) is a key variable for “differentiated needs” such as medical care, barrier-free facilities, and intelligent services, and strong correlations (r = 0.68–0.72) confirm its regularity;

- (3)

- Gender and occupation affect the focus of needs through the division of social roles, but their influence intensity is weaker than that of income and age (e.g., gender has no significant impact.

3.3. Analysis of Enterprise Symposium Conclusions

To ensure the scientificity and reliability of the symposium conclusions, a systematic coding process and multi-dimensional validation methods were adopted for the collected opinions, with details supplemented as follows:

The symposiums primarily targeted urban renewal staff from our company’s internal colleagues and some villagers from FX Village, HTX Village, and GB Village, aiming to deeply explore the real demands of villagers during urban renewal processes.

- (1)

- Open Coding: Independently labeled raw data with initial codes (e.g., “covered walkway demand,” “ancestral hall retention”) based on semantic meaning.

- (2)

- Axial Coding: By integrating initial codes around “demand types” and “spatial attributes,” several sub-categories were summarized (e.g., “physical space optimization,” “cultural heritage preservation”).

- (3)

- Selective Coding: Core categories such as “physical space adaptability,” “cultural gene continuity,” and “psychological need satisfaction” were extracted to form a logical framework of villagers’ demands.

- To verify the coding results, two validation methods were implemented.

- (1)

- Triangulation Validation: Comparing symposium data with questionnaire results (e.g., 96.15% of villagers supporting ancestral hall retention in surveys vs. 94.3% in symposiums) to confirm consistency;

- (2)

- Member Checking: Feeding back coded conclusions to 15 participating villagers for verification, with 86.7% confirming the conclusions matched their actual demands.

The systematically organized and validated data were further analyzed to provide references for livable community development under urban renewal models.

3.3.1. Analysis of Urban Project Symposium in a District of Guangzhou

- FX Village Project

The demands of FX Village villagers focus on the functional optimization of physical space, among which the demands for covered walkways, elevator configuration standards, and dual-balcony designs for large-sized apartments are particularly prominent. From the perspective of resident behavior, these demands highly coincide with the pain points of modern high-rise residences.

Building on the data analysis of “demographic supporting facilities demand” from the questionnaire survey, during the meeting with senior executives of the implementing entity, the executives proposed the idea of an “all-age friendly community” and provided a case analysis by suggesting the installation of covered walkways. This demand for covered walkways is closely related to Guangzhou’s climatic conditions. Guangzhou has a subtropical monsoon climate, with an average annual rainfall of more than 150 days, significantly reducing the traffic efficiency of traditional community pedestrian systems in inclement weather. Covered walkways constitute a triple value system from the perspective of livability. On the practical function level, the rational planning of the orientation and layout of covered walkways, with effective connection to the entrances/exits of each building and public activity areas, forms an all-weather three-dimensional pedestrian network, providing shelter for villagers moving between buildings. In terms of safety protection, detailed designs such as non-slip floor materials and handrail devices, especially tailored for elderly and child villagers, can effectively reduce the risk of falls in heavy rain. For spatial value addition, the vertical greening design on the facade of the corridor roof enhances the landscape beautification value of functional facilities. Through scientific planning, innovative design, and effective maintenance, covered walkways can become highlights of livability in reconstructed areas, fostering convenient, comfortable, and harmonious living environments.

Villagers proposed setting up more than 3 elevators in each tower, a demand that fully considers future living convenience. With the acceleration of high urbanization, high-rise residences are increasingly popular, and elevators have become a key tool for residents’ daily travel. In urban renewal projects, considering the future population density and the actual needs of residents’ daily life and goods handling, equipping each tower with more than 3 elevators can effectively reduce residents’ waiting time and avoid congestion during peak hours. From the perspective of architectural design and construction, although increasing the number of elevators requires reasonable planning of elevator shaft positions and optimized layout, occupying a certain building space, it can be achieved through scientific design while ensuring the comfort of the living space. The construction entity of urban renewal projects should select appropriate elevator brands and models to ensure the stability and safety of elevator operation.

The dual-balcony design for large-sized apartments is another core demand of villagers. From the perspective of functional zoning, this design enables clear separation between a utility balcony (for laundry, storage of cleaning supplies, and other household tasks) and a functional balcony (which can be transformed into a study, children’s activity area, small gym, or small garden, etc.). This spatial separation can accurately respond to the diverse needs of modern families for living flexibility, avoiding the problem of mixed housework and leisure functions in traditional single balconies. Additionally, dual balconies positioned in different orientations maximize natural light intake and establish efficient air convection channels, accelerating airflow and significantly improving indoor air quality.

- 2.

- HTX Village project

If the FX Village’s demands focus on the functional optimization of physical spaces, then the opinions from HTX Village reflect the villagers’ profound concern for the cultural DNA of their community. This shift from pursuing “functional convenience” to seeking “cultural identity” represents the fundamental proposition in building livable communities through urban renewal.

Based on survey data showing that 96.15% of villagers favored retaining ancestral halls and other traditional structures on their original sites, exploring the intersection of “urban renewal” and “cultural heritage” revealed that HTX Village villagers particularly proposed adding local characteristic phoenix elements to the design scheme and the demand for “separate living” in large-sized housing. Historically known as “Phoenix Cave” during the Qin Dynasty and later referred to as “Phoenix Township” by older generations, HTX Village lies within LH Street—an area where the “phoenix” symbolizes profound regional cultural memory. Villagers proposed adding “phoenix” elements to the facade design of the architectural scheme, an opinion that not only demonstrates the value of local culture but also helps enhance the cultural recognition and sense of belonging of the community. Discussions further uncovered a “material-spiritual synergy needs” in cultural preservation. The ancestral halls serve as physical cultural anchor points, while phoenix motifs act as visual symbols reactivating collective memory. Together, they constitute a community cultural identity that is “perceivable, narratable, and inheritable”. The situation further supplements the spiritual connotation of the quantitative conclusion of “retaining ancestral halls” in the questionnaire.

Villagers proposed the demand for “separate living” in large-sized housing to match the differentiated living habits of villagers of all ages, an opinion that fully considers the diversity of family structures and the differences in intergenerational lifestyles. According to the seventh population census data, 45% of families in this village have three generations living together. Separate living can provide relatively independent living spaces for members of all ages to meet their personalized needs. For example, a villager reported that after separate living, the improvement rate of his parents’ insomnia symptoms reached 82%. At the same time, for families with children, separate living can provide more suitable independent learning and entertainment spaces for children’s growth, promoting their physical and mental health.

- 3.

- GB Village Project

The demands of GB Village residents reflect comprehensive concerns for cultural inheritance, public services, and leisure quality. Villagers are most concerned about the retention of ancestral halls, medical facilities, and the setting of leisure facilities such as swimming pools. Consistent with the questionnaire data conclusion, the dialogue in GB Village also emphasizes the strong demand of villagers for retaining ancestral halls in the reconstructed area, highlighting the key position of cultural inheritance in the construction of livable communities. The ancestral hall is not only a physical building but also a spiritual symbol carrying family memories and folk traditions. Villagers proposed retaining the ancestral hall in the reconstructed area, an opinion with profound cultural value and emotional significance. From the perspective of cultural inheritance, the ancestral hall is an important place for clan sacrifices and family discussions. Retaining the ancestral hall helps maintain family ties, inherit traditional etiquette and customs, and let future generations remember family history and cultural roots. From the perspective of community cohesion, the ancestral hall can become a center for villagers to communicate and hold cultural activities, enhancing villagers’ sense of belonging and identity. In urban renewal, retaining and repairing these buildings with historical and cultural value allows villagers to still feel the cultural roots in a modern living environment. This cultural identity can enhance community cohesion, make villagers feel a sense of belonging to the community, and make the community more warm and uniquely charming. Based on the quantitative data of “public supporting facilities demand” in the questionnaire survey, combined with the qualitative feedback from enterprise symposiums, in practical operations, retaining ancestral halls requires fully considering their coordination with surrounding buildings in the planning and design stage, reasonably planning traffic flow lines, ensuring accessibility and use convenience, and carrying out necessary repairs and maintenance.

Villagers have concerns about the setting of medical facilities in public construction supporting facilities, an opinion derived from multiple factors. From the perspective of villagers’ psychology, some villagers may have traditional opinions (resistance) regarding medical facilities, worrying about the risk of pathogen transmission caused by the facilities or thinking that they may affect the Feng Shui of the surrounding living environment. From the perspective of actual use needs, if there are perfect medical resources around, villagers may think that there is no need to repeat the construction in the community, so as to avoid resource waste and space occupation. The group demand ranking in the questionnaire survey (such as medical needs ranking second) provides quantitative support for the necessity of facilities, while the specific concerns of villagers in the symposium (such as Feng Shui concepts and resource waste) provide qualitative targets for solutions. The organic combination of the two constitutes the methodological basis for urban renewal and livable community construction. Reasonably setting up community public supporting facilities such as medical facilities is of great significance for improving the living convenience and health protection of villagers in the community. The construction party of urban renewal projects can take measures such as strengthening communication, optimizing site selection and design, and clarifying functional positioning to eliminate villagers’ concerns and ensure the perfection and practicability of public construction supporting facilities.

In terms of leisure facilities, GB Village villagers proposed the suggestion of setting up swimming pools, reflecting the pursuit of a high-quality leisure life. Swimming pools can not only be used as daily fitness and entertainment places for residents but also enhance the overall quality and image of the community. A well-designed leisure environment allows residents to relax physically and mentally while fostering a sense of joy, thereby strengthening their affection for the community.

3.3.2. Extraction of Common Demands

It is found that villagers’ demands mainly focus on three aspects based on the project discussion. First, physical space adaptability focuses on traffic flow, vertical transportation, and housing type functions. Second, cultural gene continuity is reflected in the preservation of ancestral halls and the spatial translation of regional symbols. Third, psychological need satisfaction includes emotional demands such as resolving the NIMBY effect of medical facilities and improving the quality of leisure facilities.

4. Discussion

4.1. Concept and Characteristics of High Urbanization

Research and analysis across key relevant fields indicate that the international community typically employs urbanization rates to gauge urbanization levels. According to the established four-stage theory of urbanization development, an urbanization level below 30% constitutes the initial stage, 30–60% represents the acceleration/intermediate stage, 60–80% denotes the deceleration/late stage, and exceeding 80% signifies the mature/terminal stage [52]. Examining the development trajectories of advanced economies, urbanization rates of 50%, 70%, and 80% constitute critical milestones in urban development. Globally, achieving a 50% urbanization rate is recognized as a significant turning point. Below this threshold, urbanization primarily relies on labor-intensive industries and construction, focusing on light industrial goods and basic manufacturing, characterizing preliminary urbanization. Upon reaching a 50% urbanization rate, societal industrial structures undergo a significant transformation, shifting from handicrafts, light industry, and basic service sectors towards high-end finance, trade, services, and high-tech industries [53]. When the urbanization rate surpasses 70%, urban structures tend to stabilize, marking the onset of the late phase. Many developed nations, with urbanization rates exceeding 80%, achieve high urbanization levels. For example, the United Kingdom, as the world’s earliest industrialized and urbanized nation, achieved a 50% urbanization rate around 1850, reached 70% by approximately 1890 (prompting Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City concept), and surpassed 80% by 1980, attaining high urbanization [54]. In China, the current urbanization rate stands at approximately 67%, indicating the nation is approaching the late urbanization stage. Notably, Guangzhou, with an urbanization rate of 83%, has already attained levels comparable to those of developed countries. Guangzhou’s urban renewal has undergone five stages: the post-war reconstruction phase from 1949 to 1977 in the early years of the nation’s establishment; the phase of new-city expansion and old-city renewal after the reform and opening-up from 1978 to 2009; the phase of practical exploration and gradual establishment of the renewal system in the post-Asian Games period from 2010 to 2019; and the current phase of stock-based development since 2019, entering a high-quality development phase.

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC)’s Key Tasks for Building a New Type of Urbanization in 2019 explicitly mandates optimizing the urbanization spatial pattern and constructing a new spatial framework centered on “city clusters–metropolitan areas–small/medium cities–characteristic towns”. Within Chinese academia, a broad consensus recognizes that China is currently experiencing secondary urbanization (re-urbanization), transitioning from conventional urbanization toward high urbanization levels marked by urban-to-metropolitan transformation. Compared to the primary urbanization phase, secondary urbanization exhibits a multi-nodal diffusion pattern. Moreover, the primary drivers of population migration have evolved from solely employment demands to include higher aspirations for quality living environments and enhanced well-being. Spatially, this transformation manifests in two distinct trends: local urbanization (near-residence urbanization) and convergence towards regional central cities. Consequently, amid substantial industrial restructuring during this secondary urbanization phase, public expectations have shifted from “having a place to live” to “having access to quality housing” [55].

4.2. Characteristics of Livable and Friendly Communities in High-Urbanization Context

The development of livable and friendly communities within Guangzhou’s urban renewal initiatives extends far beyond mere demolition and reconstruction. Our analysis, based on survey data and stakeholder discussions with enterprises, identifies three core dimensions characterizing communities that fulfill residents’ demand for quality living in high-density urban environments: human-centered design principles, optimized architectural functionality, and integrated urban planning strategies.

- Human-Centered Design Principles:

The symbiosis of cultural heritage preservation and emotional belonging is evidenced by 96.15% of HTX villagers demanding in situ preservation of ancestral halls and other traditional structures, which they perceive as spiritual symbols crucial for maintaining familial bonds and transmitting folk rituals. Furthermore, villagers proposed integrating “Phoenix” motifs into building facades to commemorate the historical toponym “Phoenix Village,” demonstrating their commitment to constructing a tangible and narratable community cultural identity. Concurrently, universal accessibility and age-friendly service inclusivity must be prioritized. This encompasses elderly-focused facilities (e.g., community clinics, barrier-free infrastructure, health monitoring systems) alongside family-oriented amenities (e.g., educational resources for children and walkable recreational spaces).

- 2.

- Optimized Architectural Functionality:

Balancing practicality and quality necessitates designing residential units exceeding 120 m2 with dual or more balconies. To accommodate rising car ownership rates, allocating more than two parking spaces per household is essential to address future demand growth. Additionally, 64.62% of villagers requested visitor management systems and smart access control. Notably, higher-income segments expressed a preference for premium upgrades such as fresh air ventilation systems and whole-house water purification.

- 3.

- Integrated Urban Planning Strategies:

Achieving synergy between resource equity and ecological resilience requires prioritizing key amenities within the “15-min life circle” framework, specifically education (85.38%), healthcare (60%), and commercial services (54.62%). Establishing an all-weather pedestrian network via covered walkways to connect buildings and public areas is critical, while optimizing public transport intermodal connections (e.g., bus and metro interchanges) enhances overall accessibility.

In contemporary society, a fundamental tension persists between the public’s growing aspirations for a better life and persistent disparities in regional development. As the fundamental spatial unit for daily living, communities logically serve as the primary locus for addressing these evolving demands. Within the context of high urbanization, livable and friendly communities are defined by their successful integration of cultural heritage conservation, functional diversity, and coordinated spatial planning within the residential environment.

4.3. Challenges in Developing Livable Communities Under High Urbanization

Empirical consultations with urban village residents and renewal enterprises reveal that divergent stakeholder demands generate significant implementation barriers. Three primary challenges emerge: (1) Significant communication barriers and intense interest conflicts between governments and villagers. Due to distrust and information asymmetry, villagers often resist renewal projects because of historical grievances or insufficient policy transparency. Additionally, disputes over property rights and compensation standards frequently arise. Complex property ownership structures in old communities and varying demands for compensation standards and resettlement housing allocation easily trigger collective conflicts. (2) Lack of scientific district-specific regulatory planning adjustments and land approval policies, which fail to align with building demolition progress. This disconnection increases temporary relocation costs for social capital during implementation. (3) Under previous urban renewal policies, social capital bore full responsibility for project investment balance, relying mainly on sales revenue from residential and commercial properties. During real estate market downturns, social capital’s operational income becomes unsustainable, prolonging renewal cycles, escalating temporary relocation costs, and trapping projects in a vicious cycle.

4.4. Approaches to Addressing Challenges

4.4.1. Policy-Level Interventions

Urban renewal engages multiple stakeholders—governments, residents, private developers, and commercial banks—with fundamentally divergent priorities. While commercial banks prioritize economic returns and repayment schedules, their capacity to address community livability remains limited. The basic models for urban renewal and transformation in Guangzhou include comprehensive redevelopment, micro-regeneration, and hybrid redevelopment. 1. Comprehensive redevelopment refers to the redevelopment of old villages through demolition and new construction, or the implementation of ecological restoration and land reclamation for old villages. 2. Micro-regeneration involves improving old villages while maintaining the current built pattern, using methods such as partial demolition/rebuilding, functional repurposing, facade refurbishment, and upgrading public facilities and fire safety systems. 3. Hybrid redevelopment combines both comprehensive redevelopment and micro-regeneration techniques. Under Guangzhou’s traditional urban renewal model, market-driven enterprises primarily led renewal efforts, financing resettlement and reconstruction costs by leveraging excess profits from land development. Policy innovation can resolve this impasse, as demonstrated by Guangzhou’s new institutional model: Government-introduced policy banks and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) serve as implementation entities, decoupling resident demands from developer interests while mediating stakeholder conflicts. Building livable communities in highly urbanized contexts requires overcoming the cyclical dilemma of “interest conflicts–planning delays–capital risks.” Essentially representing a fiscal paradigm shift, central government backing stabilizes local debt structures to enable sustainable renewal. Under the new policy, the government designates an implementation entity (typically a local SOE) to oversee resettlement housing construction, with resettlement costs capped at 80% of the assessed land value in financing zones; land sales revenue from financing zones repays policy bank loans, ensuring funding for resettlement projects and positioning the government as the primary investor. Crucially, SOEs assume public welfare responsibilities beyond profit-seeking motives. With secured financing and absent sales pressure, these entities optimize architectural designs, integrate resident feedback, and enhance livability features. Decoupling financing-zone development from resettlement reduces risks for potential investors, attracting broader social capital participation. This tripartite mediation framework establishes a sustainable pathway for urban renewal. In Guangzhou, the number of projects adopting the SOE redevelopment model with policy bank financing, along with their advancement speed, is significantly higher than that of projects following the traditional model. However, the policy’s efficacy hinges on execution and local development stages, representing an exploratory approach for megacities in advanced urbanization.

Through local legislation, Guangzhou enacted China’s first Urban Village Regeneration Ordinance, establishing legal frameworks for collective land expropriation and storage, compensation standards, and resettlement plans—safeguarding public interest. As China’s real estate market remains in a prolonged downturn, other high-density cities engaged in stock redevelopment can adapt Guangzhou’s approach: reorienting the government’s role from ‘guiding market operations’ to ‘structurally controlling market operations,’ fortifying oversight of primary land markets, fund management, and industrial implementation.

4.4.2. Urban Planning Interventions

Under high urbanization constraints where land resources grow increasingly scarce, survey data from Guangzhou’s urban villages (Chapter 3) reveal that livable communities fundamentally center on residents’ daily amenity requirements. This necessitates strategically planned public service facilities. Planning interventions should therefore establish neighborhood-scaled, block-based public service centers aligned with urban renewal project boundaries, comprehensively covering essential needs: community clinics, public transit hubs, educational institutions, and local commercial centers. Inspired by Singapore’s hierarchical community service model, renewal projects can implement a three-tier spatial structure (“new town center—neighborhood center—cluster center”). This framework systematically calculates service radii and population density thresholds to spatially organize livable communities, ensuring equitable access to amenities while optimizing land utilization efficiency.