Abstract

The incorporation of agricultural waste into construction materials represents a promising pathway toward achieving carbon neutrality in the building sector. This study investigates the flexural performance of a novel prefabricated external wall panel composed of corn straw concrete (CSC), an eco-friendly composite material that utilizes waste corn straws. While prior studies have explored rice straw and hemp fiber concrete, they primarily focused on the mechanical properties of these materials rather than the design of prefabricated panels. This study fills the gap by optimizing reinforcement ratio and window opening layout for CSC panels, and validating their structural viability for prefabricated enclosures. An optimal mix proportion was identified, which meets the mechanical requirements for non-load-bearing applications. Four prototype panel specimens were subjected to out-of-plane monotonic loading, considering variables including reinforcement ratio (0.18% vs. 0.24%) and the presence of a window opening (25% area ratio). Results indicated that increasing the reinforcement ratio significantly enhanced the ultimate load capacity by up to 33.3% (from 45 kN to 60 kN)—an enhancement effect that was 12–15% higher than that of reported rice straw concrete. In contrast, the introduction of an opening reduced the ultimate load capacity by 11.1–16.7%. A detailed nonlinear finite element model (FEM) was developed and validated against experimental results. The validation results indicated deflection error of 7.7–12.8% (mean: 9.33%; SD: 2.05), ultimate load error of 7.7–11.1% (mean: 9.48%; SD: 1.32), and a correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.96 between simulated and experimental values. Furthermore, analytical methods for predicting the cracking moment (with an average error of 5.97%) and ultimate flexural capacity, based on yield line theory (with an average error of 8.43%), were proposed and verified. This study demonstrates the structural viability of CSC panels and provides a sustainable solution for waste reduction in prefabricated building enclosures, contributing to greener construction practices.

1. Introduction

As an agricultural by-product, straw exhibits an exceedingly high annual yield, with corn straw being one of the most abundantly produced types [1]. Current methods for straw disposal include its use as fuel, soil fertilizer, and animal feed, which are associated with relatively high CO2 emissions [2,3]. However, due to constraints such as high labor costs, a significant proportion of crop straw is burned in situ annually, causing severe environmental pollution.

To reduce CO2 emissions and promote sustainable development in the construction engineering sector, the development of green building materials has become a key area of research worldwide [4]. Straw fiber, a common agricultural waste, has been extensively investigated in building materials research in recent years due to its advantages of being lightweight, low-cost, and eco-friendly [5]. Some scholars have heated straw in an oxygen-limited environment to produce biochar [6]. Replacing part of the cement with straw biochar on an equal-mass basis can not only reduce cement consumption to some extent but also sequester carbon from the straw and absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, thereby contributing to energy savings and carbon reduction [7,8,9]. Incorporating straw fiber into concrete not only reduces the density of concrete but also significantly enhances its mechanical properties, particularly in terms of toughness and crack resistance [10]. Some researchers have already introduced straw ash into concrete as a mineral admixture, but its effect on enhancing concrete performance remains controversial. Some studies have found that the strength of straw ash concrete is higher than that of ordinary concrete [11,12], while others have reported a decrease in concrete strength with the addition of straw ash [13]. Liu et al. reported that rice straw fiber can be pretreated with an alkaline solution before being mixed with concrete [14,15]. The modified rice straw fiber-reinforced concrete (RSFRC) they developed also promoted the application of plant straw fiber in civil engineering [16]. However, some scholars have demonstrated that plant fibers can be decomposed and mineralized in the highly alkaline environment (pH > 13) of Portland cement-based materials, which may cause the plant fibers to lose their reinforcing effectiveness [17,18]. Strength differences may arise from fiber pretreatment—alkaline treatment (NaOH solution) can remove lignin and improve interfacial bonding, while untreated straw leads to strength reduction due to poor dispersion. Natural fibers are prone to mineralization in Portland cement (pH > 13), which reduces long-term durability. Recent studies have used silane coating to improve alkali resistance, increasing fiber service life by 50% [19]. Based on existing research results [10,12,14], the comparison of mechanical properties of straw-based concrete is detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison table of mechanical properties of straw-based concrete.

Due to global warming, researchers are increasingly interested in studying and developing sustainable building technologies [20]. Prefabricated buildings offer significant advantages in carbon emission reduction and environmental protection [21], while also being more material-efficient compared to traditional construction methods [22,23,24,25,26]. Worldwide efforts are actively promoting prefabricated buildings, which will considerably contribute to achieving carbon emission reduction and carbon neutrality goals. Prestressed concrete composite panels are critical and primary components in prefabricated building projects [27], often used as external and internal partition walls [28]. In line with sustainability requirements, the use of environmentally friendly materials is essential when developing building components. Straw fiber exhibits low thermal conductivity and high sound insulation properties, with numerous engineering examples of its direct use in building construction [29]. To further reduce carbon emissions, future studies may replace steel reinforcement with natural fiber composite bars (hemp/flax), which have 60–70% lower CO2 emissions than steel.

The scientific gap is that existing studies lack systematic design for corn straw concrete (CSC) prefabricated panels, including reinforcement optimization and opening layout, which are critical for practical application. International studies on bio-based concrete have focused on hemp fiber panels and flax fiber composites [21,30], but few have investigated corn straw for prefabricated external walls. This study addresses this by integrating corn straw into prefabricated panels, a material with higher annual yield (280 million tons/year in China) than hemp (15 million tons/year globally).

In this study, standard specimens of straw concrete were prepared by mixing dried corn straws—after being crushed—with cement, fly ash, and aggregates in specific proportions. The mechanical properties of the straw concrete were investigated without the addition of any chemical admixtures. The experimental procedure is simple, and the raw materials are widely available. Subsequently, non-load-bearing straw concrete wall panels were produced, reinforced with double-layer bidirectional steel meshes to enhance both the load-bearing capacity and deformation resistance of the panels.

This study is structured as follows: Standard specimens of CSC were fabricated and subjected to loading to investigate the stress-strain constitutive relationship of the straw concrete. The optimal mix proportion was selected based on control indicators, including axial compressive strength, apparent density, elastic modulus, and Poisson’s ratio, while meeting the basic requirements for non-load-bearing external wall structures. Ordinary wall panels and window-opening wall panels with steel meshes were produced and subjected to static loading applied perpendicular to the test plane. Additionally, finite element modeling was employed to perform numerical simulations of the panels’ structural performance. By studying the failure conditions, deformation characteristics, and load-carrying capacity of the panels, their behavior and failure characteristics under static loading applied perpendicular to the plane were observed. Calculation methods for the cracking moment and ultimate flexural capacity of such panels were proposed. The aim is to provide a reference for the engineering application of prefabricated corn straw concrete external wall panels. Three research gaps are addressed: (a) Lack of design methodology for CSC prefabricated panels; (b) Few studies on yield line theory application in CSC panels; (c) No validated FEMs for CSC panels considering reinforcement and openings.

The framework diagram of this research is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework of this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mix Proportion Design of Corn Straw Concrete

The optimal mix proportion for corn straw concrete (CSC) was determined through experimental research. Corn straw was dried at 80 °C for 24 h to reduce moisture content to 8 ± 2%, then crushed into 5–10 mm lengths using a hammer mill. To improve alkali resistance, straw was soaked in a 5% NaOH solution for 2 h, then rinsed with distilled water until the pH reached 7. Crushed corn straws were incorporated into a mixture of cement, sand, and fly ash. During mixing, the moisture content of sand and fly ash was monitored (≤0.5%), and additional water was adjusted to maintain the designed water-binder ratio (0.40). This mixture was used to fabricate standard prismatic specimens measuring 150 mm × 150 mm × 300 mm. Mechanical property tests were conducted to obtain the mechanical performance parameters of this composite material. The specimens and their loading setup are illustrated in Figure 2. In this experimental program, the water-to-binder ratio was maintained as a constant, whereas the proportions of fly ash, sand, cement, and corn straw were varied. The detailed content parameter design is provided in Table 2. Six replicate specimens were fabricated for each mix proportion to ensure test repeatability. Straw content was set to 1.5–3.5% based on prior studies—≤2% ensures good workability and no fiber balling, while >3% leads to significant strength loss. Using a single-factor experimental approach, the researchers examined the effects of these four variable design parameters on the axial compressive strength and density of corn straw concrete. The test results are detailed in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Specimens and loading device: (a) CSC prism specimens (150 mm × 150 mm × 300 mm); (b) Universal testing machine (capacity: 2000kN).

Table 2.

Design of mix proportion parameters for corn straw concrete.

Table 3.

Mechanical performance parameters of corn straw concrete.

In this study, in accordance with the industry standard Plant Fiber Cement Wall Panels for Buildings (JC/T 2672-2022) [31], C15 grade concrete meets the basic mechanical performance requirements for non-load-bearing external wall panels. According to the Code for Design of Concrete Structures (GB 50010-2010, China National Standard) [32], the characteristic value of axial compressive strength for C15 concrete is 10.0 MPa, and the design value is 7.2 MPa. Wind load is the primary lateral load borne by building envelopes. High-rise buildings are susceptible to wind load responses. Inadequate design may lead to structural collapse, resulting in significant casualties and substantial economic losses [33,34,35]. Typically, wind load on enclosures is calculated according to the Load Code for the Design of Building Structures (GB 50009-2012) [36]. For the three northeastern provinces of China, considering a 50-year return period, the maximum characteristic wind pressure is 0.65 kN/m2. Considering a local shape coefficient of 1.40 and a ground roughness category of C, the design wind load reaches 2.307 kN/m2 at a height of 100 m. Integrating the test results and the factors above, the optimal mix proportion for corn straw concrete was selected as No. 2 from Table 2, i.e., a water-to-binder ratio of 0.40, corn straw content of 2%, and mass ratio (fly ash:sand:cement) of 1:2:7. The experimentally measured axial compressive strength of this straw concrete was 8.59 MPa.

2.2. Flexural Performance Test of Precast Corn Straw Concrete External Wall Panels

Out-of-plane static tests were conducted on straw concrete exterior wall panels to assess the impact of variations in reinforcement ratios and window opening configurations on crack initiation, propagation, deformation behavior, and ultimate load capacity. The experimental outcomes provide valuable insights for the practical application of corn straw concrete external wall panels in engineering.

2.2.1. Design and Manufacture of Specimens

Taking into account influencing variables such as varying steel reinforcement ratios, the presence and arrangement of window openings, four groups of specimens were designed for static loading tests under out-of-plane load.

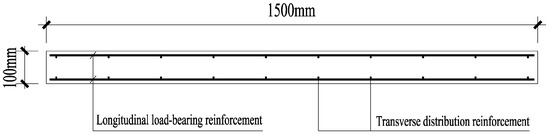

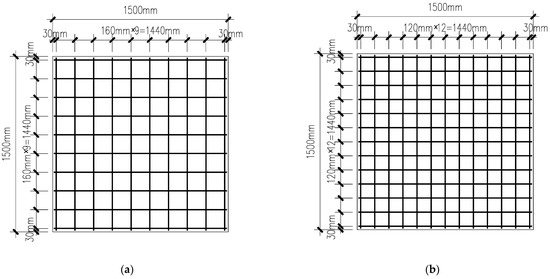

Straw concrete wall panels are intended for use as enclosure structures in prefabricated buildings. Their dimensions should be modular, based on the story height and column spacing of the building structure. Typically, the height of the wall panel equals the story height, and the length equals the column spacing. Generally, one straw concrete wall panel is used between every two columns. If the column spacing is relatively long, it is recommended to use two wall panels between every two columns, connected by special components. Due to the limitations of the testing site and equipment, the specimens were fabricated at a 1:2 scale. Scale effects (1:2) were considered—smaller specimens may overestimate compressive strength by 8–10% due to reduced voids. However, the relative trend of reinforcement and opening effects remains consistent with full-scale panels, as verified by FEM simulations. Each of the four test panels measured 1500 mm × 1500 mm in plan dimensions, with a consistent thickness of 100 mm. Among them, two panels had window openings measuring 750 mm × 750 mm. The basic parameters of the test panels are listed in Table 4. Bidirectional orthogonal steel meshes were symmetrically arranged along the thickness direction of the panels. The steel bars were HPB300 grade with a diameter of 6 mm. The vertical bars, placed on the outer side, served as the primary reinforcement, while the horizontal bars, placed on the inner side, served as distribution reinforcement. The intersections of the steel bars were connected by tying them together. The concrete cover thickness was 10 mm. Figure 3 illustrates the through-thickness structural configuration of the test panel, and Figure 4 presents the in-plane structural arrangement.

Table 4.

Basic parameters of the test panel.

Figure 3.

Cross-sectional layout of bidirectional orthogonal reinforcement mesh in test wall panels.

Figure 4.

In-plane bidirectional orthogonal reinforcement mesh structural configuration of test panel: (a) Panel 1; (b) Panel 2; (c) Panel 3; (d) Panel 4.

The test wall panels were made from corn straw concrete using the No. 2 design parameters from Table 2 (water-to-binder ratio 0.40, corn straw content 2%, mass ratio fly ash:sand:cement = 1:2:7). The experimentally measured axial compressive strength of the straw concrete was 8.59 MPa, the elastic modulus E was 3895 MPa, and the Poisson’s ratio was 0.235. The slump of the optimal mix proportion (No. 2) is 55 mm, and its compactness is 96.2%. The measured elastic modulus (E) of the steel reinforcement was 212.1 GPa, the ultimate tensile strength (fu) was 410.078 MPa, and the yield strength (fy) was 264.325 MPa. In accordance with GB/T 50080-2016 (Standard for Test Methods of Performance on Fresh Concrete of China) [37], the specimens were cured for 28 days under conditions of 20 ± 2 °C and 95 ± 2% relative humidity (RH).

2.2.2. Test Loading Equipment and Procedure

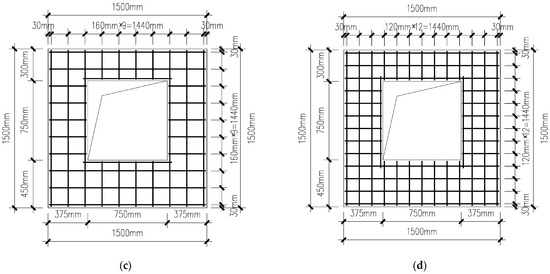

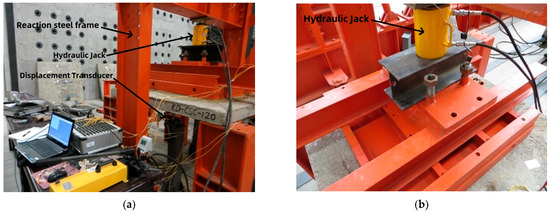

The four edges of the precast wall panels were flexibly connected to frame beams and columns. Under out-of-plane loading, the frame beams and columns could only be considered as supports for the wall panels. For loading convenience, the specimen was placed horizontally, and the lateral load was converted into a vertical load for application, by utilizing a reaction rigid frame to provide the loading reaction. Precast panels are subjected to uniformly distributed loads, such as stacking loads during transportation and installation, as well as wind loads in service. In this experiment, a concentrated load was converted into a distributed load to simulate a uniform load through a system comprising a thick steel plate, a profiled steel plate, three H-beams, and a fine sand cushion layer arranged on top of each wall panel. A schematic diagram of the loading setup is shown in Figure 5. During the test, the four corners of the wall panel were supported on bearings, and monotonic loading was adopted. The loading device used a ZY-50 rock bolt tension meter to apply a uniform load to the wall panel via the reaction frame, with shaped steel and steel plates placed on the panel surface. The loading test equipment is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of the test loading setup: (a) Cross-section view; (b) Plan view.

Figure 6.

On-site image of test loading device: (a) Overall loading system; (b) Local view of sand cushion and steel plate.

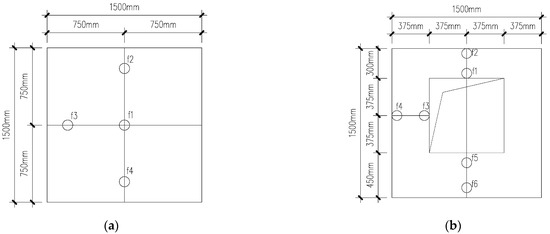

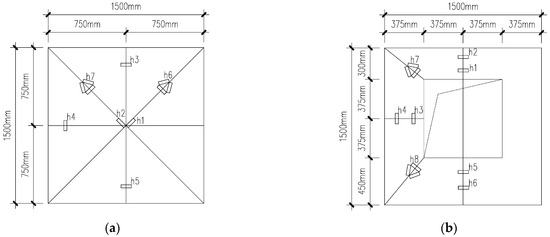

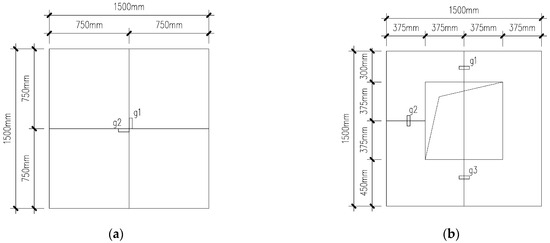

The test primarily measured the cracking load, ultimate load, crack characteristics, and deformation of the wall panels. Crack propagation was monitored mainly using a digital crack width microscope. Displacement transducers were arranged at the mid-span of each bottom edge and at the center of the bottom surface of each panel to measure deformations at different loading stages. The layout of measuring points is shown in Figure 7. Strain gauges were attached to the straw concrete on the panel surface and to the steel bars within the panel at corresponding locations to measure strains at the key loading stages (e.g., at cracking, yielding, and ultimate loads). Strain values were collected by a DH3816 static strain testing system. The layout of strain measurement points on the panel surface of the straw concrete is shown in Figure 8, and the layout on the internal steel bars is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 7.

Layout of displacement gauges, f1 to f6 are the arrangement positions of displacement gauges for the test wall panel: (a) Ordinary plate; (b) Perforated plate.

Figure 8.

Layout of strain gauges for straw concrete, h1 to h8 are the arrangement positions of straw concrete strain gauges for the test wall panel: (a) Ordinary plate; (b) Perforated plate.

Figure 9.

Layout of strain gauges on internal reinforcement of plates, g1 to g3 are the arrangement positions of in-panel reinforcement strain gauges for the test wall panel: (a) Ordinary plate; (b) Perforated plate.

According to the Standard for Test Method of Concrete Structures GB/T 50152-2012 [38], this test adopted monotonic loading with a graded loading system. Each load increment was 5 kN. After each increment, the load was held constant for 10 min before proceeding to the next increment, continuing until the wall panel component reached its ultimate bearing capacity.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Phenomena and Failure Modes

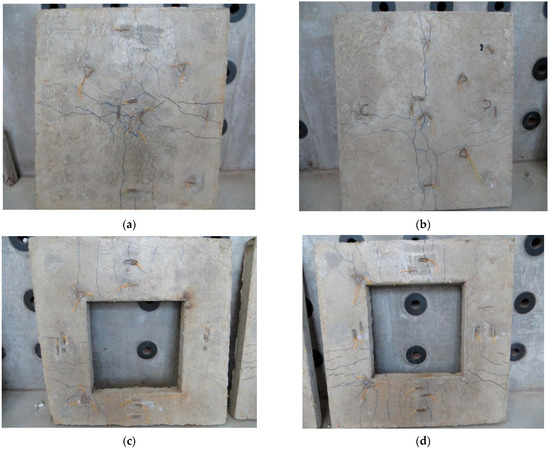

Under monotonic loading conditions, the stress progression of the specimens exhibited three distinct phases: the cracking stage, the yielding stage, and the ultimate stage. The final crack patterns at the bottom surfaces of wall panels Panel 1 through Panel 4 are presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Crack development at the bottom of Panel 1-Panel 4, blue lines represent main cracks: (a) Panel 1; (b) Panel 2; (c) Panel 3; (d) Panel 4.

Since straw concrete is a relatively new material, standards for reinforced concrete structure tests may not be fully applicable for determining the cracking load, yield load, and ultimate load of the wall panels. During the experiment, the following criteria were adopted to determine the cracking load, serviceability limit load, and ultimate bearing capacity of the panels:

- Cracking load was determined by two methods: The load at which the first crack was visually detected in the panel was defined as the cracking load. According to the Load-Deflection Curve Method, the cracking load was identified as the point corresponding to the first abrupt change in slope of the plotted load-deflection curve.

- The yield load was determined by two criteria: the load at which the maximum crack width in the concrete at the tensile reinforcement location reached 0.2 mm; and the load at which the mid-span deflection of the panel reached 1/200 of its span.

- Ultimate Bearing Capacity Load was determined by four methods: Crushing of concrete in the compressive zone; attainment of a compressive strain of 0.0033 in the concrete; and development of a maximum crack width of 2 mm in the tensile zone at the bottom of the panel. Readings from the strain acquisition instrument began to decrease, or the load on the panel could not be increased further.

3.1.1. Cracking Stage

During the initial loading phase, the first crack appeared at the mid-span of each bottom edge of the wall panel; however, the overall stiffness remained good. The incorporation of an internal steel mesh contributed to an increase in the cracking load of the wall panels. Before cracking, all specimens exhibited comparable deformation behavior.

3.1.2. Yielding Stage

As the load increased, the length and width of some initial cracks gradually increased, and new cracks continued to develop, accompanied by slight audible sounds. Cracks continued to develop, accompanied by slight, audible sounds. A marked reduction in the integrity and a rapid decline in stiffness were observed in the test panels during loading. Wall panels with openings exhibited crack propagation earlier than solid panels. Panels with a higher reinforcement ratio exhibited delayed crack propagation. This indicates that openings reduce the flexural stiffness of the wall panel, whereas increased reinforcement can delay crack propagation.

3.1.3. Ultimate Stage

With increasing load, the straw concrete in the compression zone was crushed, and the bottom cracks fully developed. Two sets of mutually perpendicular, “+”-shaped penetrating diagonal cracks appeared at the center of the bottom surface, indicating that the wall panel had reached its ultimate state. Crack initiation occurs at the mid-span (tensile zone) due to bending moment concentration. Higher reinforcement ratio (0.24%) delays crack propagation by transferring stress to steel, reducing crack width by approximately 30% compared to panels with a 0.18% reinforcement ratio. In panels with openings, several transverse cracks penetrated the wall around the window opening; all cracks penetrating the window opening wall occurred on the bottom surface of the panel. Window openings cause stress concentration at corners, leading to diagonal cracks. This is consistent with RC panels, but corn straw concrete (CSC) panels exhibit a lower crack propagation rate due to the straw fiber bridging effect.

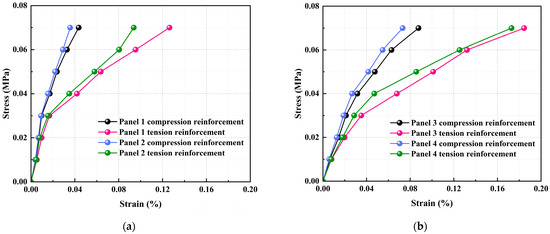

3.2. Load-Deflection Curves

Characteristic deflection values obtained from the test panels are summarized in Table 5, while the corresponding load-deformation relationships are illustrated in Figure 11.

Table 5.

Characteristic Deflection Values of Specimens.

Figure 11.

Out-of-plane load-deflection curves of CSC panels: (a) Central position of the ordinary panel; (b) Mid-span position of the side span of the panel with openings.

As indicated in Table 5 and Figure 11, the load-displacement responses of all panels before yielding displayed similar profiles, characterized by linear elastic behavior. Openings in the wall panel reduce its stiffness. Upon reaching the yield load, the stiffness of the wall panels decreased. With a slow increase in load, the rate of increase in wall panel deformation exceeded the rate of load increase. After reaching the yield load, the wall panels could still withstand slowly increasing loads, indicating that the steel mesh effectively improved the mechanical performance of the panels. Upon reaching the ultimate load, the curve’s slope experienced a gradual reduction.

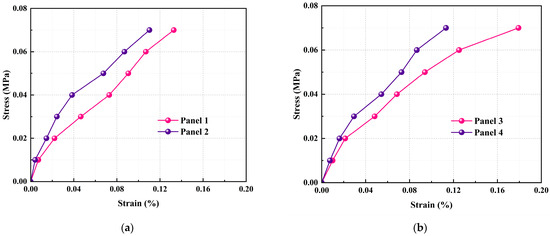

3.3. Load-Strain Curves

Figure 12 shows the load-strain responses of the straw concrete material within the panels.

Figure 12.

Load-strain curves of straw concrete for Panels 1–4: (a) Central position of the ordinary panel; (b) Mid-span position of the side span of the panel with openings.

As shown in Figure 12, the load-strain relationship was essentially linear at low load levels. This indicates that the wall panels behaved elastically under initial loading. With further increase in load, the growth rate of strain accelerated compared to before cracking, indicating entry into the elastoplastic stage, marked by a noticeable inflection point in the load-strain curve. With a further increase in load, panels exhibiting higher strain reached the ultimate state earlier, whereas those with lower strain sustained greater loads.

The load-strain curves for the steel reinforcement in the wall panels are shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Load-strain curves of reinforcement for Panels 1–4: (a) Central position of the ordinary panel; (b) Mid-span position of the side span of the panel with openings.

Figure 13 shows that in the initial loading stage, the load-strain curves of the upper and lower steel layers in the same wall panel were essentially consistent, indicating that the relative position of the two layers of steel mesh in the precast wall panel remained unchanged, with consistent deformation. A linear correlation was observed between load and strain within the elastic range. At low load levels, the reinforcement ratio exerted minimal influence on strain variation. With increasing load, a noticeable divergence emerged between the strain values in the upper and lower reinforcement layers in Panels 1 and 2. This is because during bending, the upper steel bars were constrained by the loading steel plate, leading to slower strain development and a notable difference between upper and lower steel strain values. For Panels 3 and 4, which had central window openings, the constraining effect of the loading steel plate was significantly reduced. After cracking occurred in the wall panels with increasing load, the steel reinforcement gradually took on a dominant role in the load-bearing capacity. Panels with a smaller reinforcement ratio reached the ultimate state first, while panels with a larger reinforcement ratio could withstand greater loads.

3.4. Characteristic Bearing Capacity Values

Based on the criteria for determining characteristic load values of the test panels’ bearing capacity outlined in Section 3.1 of this paper, and through comprehensive analysis of the test results, characteristic values corresponding to the bearing capacity are provided in Table 6.

Table 6.

Characteristic bearing capacity values of test panels.

- Cracking Load: Panel 2, with a reinforcement ratio 0.06% (12.5%) higher than that of Panel 1, exhibited a 12.5% increase in cracking load, reaching 22.5 kN. Panel 4, with a reinforcement ratio 0.06% higher than Panel 3, exhibited a 14.3% increase in cracking load, reaching 20.0 kN. Designing an opening in the center of the wall panel, occupying 25% of the total panel area, reduced the cracking load by 12.5% for a reinforcement ratio of 0.18% and by 11.1% for a reinforcement ratio of 0.24%.

- Yield Load: Panel 2, with a reinforcement ratio 0.06% higher than that of Panel 1, exhibited a 14.3% increase in yield load, reaching 40 kN. Panel 4, with a reinforcement ratio 0.06% higher than Panel 3, exhibited a 16.7% increase in yield load, reaching 35 kN. The opening reduced the yield load by 14.3% for a reinforcement ratio of 0.18%, and by 12.5% for a reinforcement ratio of 0.24%.

- Ultimate Load: Panel 2, with a reinforcement ratio 0.06% higher than that of Panel 1, exhibited a 33.3% increase in ultimate load, reaching 60 kN. Panel 4, with a reinforcement ratio 0.06% higher than Panel 3, exhibited a 25% increase in ultimate load, reaching 50 kN. The opening reduced the ultimate load by 11.1% for a reinforcement ratio of 0.18%, and by 16.7% for a reinforcement ratio of 0.24%.

The experimental results indicate a linear load-deformation relationship under service load levels, indicating that the wall panel remained in the elastic stage. As cracks successively appeared and propagated on the wall panel, the rate of deformation increase accelerated compared to before cracking, and the bottom layer of the wall panel entered the elastoplastic stage. Failure was characterized by large deformations and widespread cracking, which indicates obvious ductile failure behavior. Increasing the reinforcement ratio did not significantly improve the cracking load of the wall panel; however, it delayed the development of cracks and significantly enhanced the ultimate flexural bearing capacity of the wall panel. As the load increased, punching shear failure was likely to occur easily at the four corners of the wall panel. Therefore, in structural design, simply increasing the reinforcement ratio cannot solely be used to enhance the bearing capacity of the wall panel; attention must also be paid to the design of the connections between the wall panel and the structure.

4. Numerical Simulation

Due to constraints in experimental capabilities, a numerical investigation was conducted to simulate the flexural behavior of precast straw concrete wall panels. This approach aimed to establish a dependable numerical framework for subsequent parametric studies and structural optimization, while further offering a theoretical basis for the rational development and utilization of this type of wall panel. Recent studies on FEM of bio-based concrete composites have highlighted the importance of material nonlinearity and interface behavior [39]. Consistent with this framework, the present study establishes a SOLID65-based FEM model to simulate the out-of-plane flexural behavior of corn straw concrete (CSC) panels.

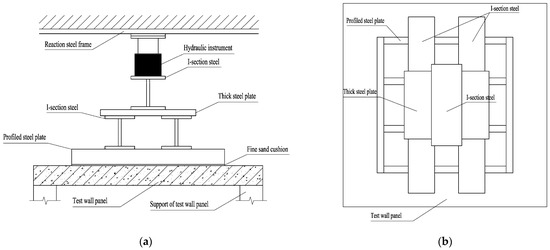

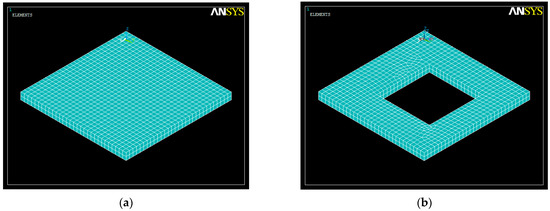

4.1. Establishment of the Finite Element Model

The widely utilized ANSYS 16.0 finite element software was employed to analyze the stress distribution and deformation characteristics of composite wall panels subjected to out-of-plane loading. The model of the straw concrete composite panel, depicted in Figure 14, was developed under the assumption of uniformly distributed reinforcement throughout the panel. To streamline the finite element analysis, the bond-slip interaction between the straw concrete and steel reinforcement was disregarded. A smeared model (SOLID65 element with rebar) was deemed more applicable. The SOLID65 element is commonly used to simulate reinforced concrete structures, as it can represent properties such as concrete cracking and crushing, thereby enhancing the nonlinear analysis of the material. When defining the element material properties, the steel reinforcement was simulated by defining the reinforcement material within the SOLID65 element, modeling the bidirectional orthogonal distribution of steel bars within the panel. The four ends of the composite panel were supported. Constraints were applied to the bottom surface of the supports to prevent movement in the x, y, and z directions, which is consistent with engineering practice. A uniformly distributed load was applied out-of-plane, and a nonlinear analysis was performed using a method of gradually increasing the load until failure of the finite element model occurred.

Figure 14.

Finite element models of straw concrete wall panels: (a) Ordinary panel; (b) Panel with openings.

To ensure model reproducibility, the key parameters and assumptions are summarized as follows:

- Mesh Design: A structured mesh was adopted for the concrete volume. After a convergence study, an element size of 25 mm was selected, which provided a balance between computational accuracy and efficiency.

- Boundary Conditions (BCs): The four edges of the panel were modeled as simply supported. This was implemented by constraining the out-of-plane displacement (UZ) and the in-plane rotations (ROTX, ROTY) at the bottom surface of the support lines, while allowing in-plane translations to simulate flexible connections.

- Loading Application: A uniformly distributed load was applied perpendicular to the plane of the panel, simulating the experimental loading condition.

- Modeling Assumptions: The model incorporated two primary assumptions: (1) a perfect bond (no slip) was assumed between the corn straw concrete and the steel reinforcement; (2) the double-layer bidirectional steel mesh was modeled as a smeared reinforcement layer within the SOLID65 elements, defined by the volumetric reinforcement ratio and material properties obtained from tensile tests.

- Validation Approach: The model was validated by comparing its predictions for ultimate load and mid-span deflection against the experimental results from the four tested panels, as detailed in Section 4.2.

4.2. Finite Element Model Validation

Figure 15 presents the displacement contour plot of the composite wall panel model obtained from finite element computation. Stress distribution at the top surface of the panel exhibited a “+”-shaped pattern aligned with the span direction, with the maximum stress occurring at the center of the panel. The stress at the bottom of the panel radiated from the center towards the edges, with the maximum stress at the center. Stress concentration phenomena occurred at the four support locations. The strain in the wall panel corresponded to the stress, with the maximum strain at both the top and bottom located at the center of the panel.

Figure 15.

Development diagrams of the wall panel bottom: (a) Panel 1; (b) Panel 2; (c) Panel 3; (d) Panel 4.

From Figure 15a,b, it can be observed that when the wall panel was subjected to load, the displacement and stress were greatest at the center, and the failure pattern was distributed in a “+” shape. The deflection values and characteristic load values calculated by the numerical model were slightly higher than the measured values. This is because the experimental wall panels could not distribute the load over their entire surface as uniformly as the numerical model. FEM assumes uniform load distribution, while experimental load has local concentration (due to sand cushion unevenness), leading to a partial reduction in the simulated load. Therefore, the measured value is slightly smaller. The discrepancy between theory and practice is not significant and remains within a controllable range.

A comparative analysis was conducted between the experimentally measured values and the simulated values from the finite element model. For wall panels with window openings, the deflection value at the mid-span of the wider strip beside the opening was selected for comparison. The deflection values and ultimate loads obtained through experimentation and finite element analysis are shown in Table 7 and Table 8, respectively.

Table 7.

Comparison between simulated and experimental deflection values.

Table 8.

Comparison between simulated and experimental values of ultimate load.

From Table 7 and Table 8, it can be observed that the simulated values for both deflection and load are slightly higher than the experimental values; however, the trends of change for both values are the same. Panel 4 showed the largest error in deflection value, with the experimental value being 87.2% of the simulated value. Panel 3 showed the smallest error in deflection value, with the experimental load being 93.1% of the simulated load. The maximum discrepancy in load value was observed in Panel 3, where the experimental result reached 88.9% of the simulated value. In contrast, Panel 2 exhibited the smallest deviation, with an experimental load equivalent to 91.7% of the simulated load. These findings confirm that the ANSYS finite element model is capable of replicating the bearing capacity and deformation behavior of the composite panels with satisfactory accuracy, demonstrating its reliability for practical design applications. However, the finite element method also has certain limitations. The limitations mainly include: (1) The degradation of the fiber-concrete interface was not taken into account; (2) Only perform monotonic loading without fatigue simulation; Future models will solve these problems. In the future, the finite element model can also be extended to simulate other working conditions of composite wall panels, thereby laying the foundation for the shape optimization design of composite wall panels.

5. Theoretical Analysis

5.1. Cracking Moment of Composite Wall Panel

The cracking moment refers to the moment that a flexural member can sustain just before cracks appear on its tension face. In this study, the cracking moment was calculated based on elastic theory and the concept of the transformed section, following established design code methodologies. The detailed formulation and equivalent transformation procedures are provided in Appendix A.1.

Before the composite wall panel reaches the cracking moment, the stress-strain relationship of corn straw concrete (CSC) follows a linear law, allowing it to be treated as an elastic material.

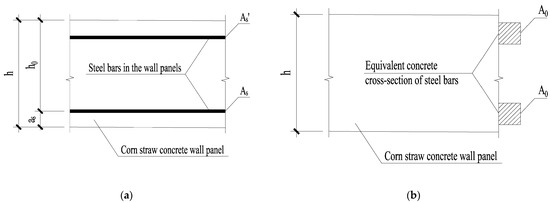

When calculating the cracking moment of a homogeneous composite wall panel, the reinforcement area (As) is converted to an equivalent concrete area (A0 = αE × As) using the elastic modulus ratio (αE = Es/Ec), forming a transformed section. The reinforcement in the panel is circular. After transformation, imaginary circular concrete sections are added to the top and bottom of the CSC panel (Figure 16). The geometric properties of this transformed section (centroid position y0, moment of inertia I0) are calculated using classic mechanics-of-materials formulas (see Appendix A.1).

Figure 16.

Schematic diagram of the typical cross-section of a two-way panel: (a) Before equivalent transformation; (b) After equivalent transformation.

A comparison between theoretical and experimental cracking loads is presented in Table 9. The results indicate that the theoretically derived cracking loads are in good agreement with the measured values, showing an average error of 5.97%. Thus, the theoretical values can be adopted as reliable references for experimental evaluations.

Table 9.

Comparison between theoretical and experimental values of cracking load.

5.2. Ultimate Flexural Bearing Capacity of Composite Wall Panel

For calculating the ultimate flexural bearing capacity of two-way panels, the yield line theory was applied. The theory assumes that at the ultimate load, a series of plastic hinge lines form within the panel, dividing it into several rigid segments. The external work done by the applied load is equated to the internal work dissipated along the yield lines. The complete derivation, including the virtual work equation and the enhancement factor for plant fiber reinforcement, is detailed in Appendix A.2.

A comparison of ultimate loads between theoretical predictions and experimental measurements is provided in Table 10. The data show that the computed ultimate bearing capacities correlate well with the test results, exhibiting an average error of 8.43%. This validates the theoretical values as reliable references for experimental studies.

Table 10.

Comparison between theoretical and experimental values of ultimate load.

In summary, it can be seen from Table 9 and Table 10 that the theoretical calculated values for cracking load and ultimate load are both slightly larger than the test measured values. This is because the yield line theory assumes an ideal plastic behavior without material degradation, while the experimental panel has microcracks, which reduce the load-bearing capacity and lead to a partial increase in the theoretical load. However, all the errors were within the acceptable range of civil engineering (≤15%), which verified its reliability.

6. Conclusions

Sustainable Material Solution: A viable mix proportion for non-load-bearing corn straw concrete was developed, successfully incorporating 2% agricultural waste by mass. The resulting material (Compressive strength: 8.59 MPa, Density: 1756 kg/m3) fulfills the mechanical criteria for prefabricated envelope applications and aligns with the principles of resource efficiency and circular economy in construction.

Structural Performance Enhancement: Increasing the reinforcement ratio from 0.18% (Φ6@160) to 0.24% (Φ6@120) markedly improved the flexural performance, elevating the ultimate load capacity by 25.0% to 33.3%. This finding underscores the effectiveness of conventional steel reinforcement in enhancing the structural reliability of this novel composite.

Quantified Impact of Openings: The presence of a window opening (with a 25% area ratio) was identified as a critical design factor, resulting in an 11.1–16.7% reduction in both cracking load and ultimate load. Stress concentration around the opening corners was the primary failure initiator, necessitating localized reinforcement in practical design.

Validated Numerical and Analytical Tools: The established finite element model accurately simulated the structural behavior of CSC panels, with maximum errors of 12.8% (deflection) and 11.1% (load capacity), providing a reliable tool for future parametric studies. The proposed analytical methods, derived from elastic theory and yield line theory (with a bending enhancement factor of 1.15 for CSC), enabled the accurate prediction of cracking moment (average error of 5.97%) and ultimate capacity (average error of 8.43%), thereby bridging the gap between experimental validation and design application.

For engineering applications, the optimal reinforcement ratio is 0.24% (Φ6@120) for solid panels, and window opening ratio should be ≤20% to avoid excessive load reduction. The limitations of this study include a small sample size (n = 3 for each panel type) and the absence of long-term field test data under actual service conditions (e.g., cyclic wind loads, temperature variations). Therefore, further full-scale panel tests are needed to validate practical performance. Future research will focus on long-term durability (e.g., freeze-thaw resistance, creep behavior) and large-scale manufacturing (e.g., prefabrication efficiency optimization). In addition, exploring hemp/flax composite bars as reinforcement for CSC panels will be a key direction to enhance the sustainability of prefabricated structures.

Contribution to Green Construction: This study demonstrates the feasibility of utilizing corn straw—an abundant agricultural waste—in prefabricated components, a practice that can reduce carbon emissions and agricultural waste pollution, thereby enhancing sustainability in the building industry. The findings provide valuable insights for engineers and architects seeking to incorporate innovative, eco-friendly materials into modern construction practices. Future work will propose design guidelines for CSC panels, aiming to integrate them into the updated Standard for Prefabricated Concrete Buildings of China (GB/T 21086-2019) [40].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.X.; methodology, W.X. and W.-N.W.; software, W.X. and W.-N.W.; validation, W.X.; formal analysis, W.X.; investigation, W.X. and W.-N.W.; resources, W.X.; data curation, W.X. and T.-Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, W.X.; writing—review and editing, W.X., W.-N.W. and Y.W.; funding acquisition, W.X. and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was jointly supported by the Basic Scientific Research Project of Department of Education of Liaoning Province (Grant No. LJ212410148051), Doctoral Research Start-up Project of the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (Grant No. 2025-BS-0420) and the Liaoning Petrochemical University Doctoral Teachers Research Project (Grant No. 2023XJJL-022).

Data Availability Statement

Some or all of the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Formulas for Cracking Moment and Ultimate Flexural Capacity

Appendix A.1. Cracking Moment Calculation

The cracking moment itself is computed using the formula from the Code for Design of Concrete Structures (GB 50010-2010) [32], as follows:

where:

- γ is the plastic influence coefficient of the section modulus (taken as 1.55 for rectangular sections);

- ftk is the characteristic axial tensile strength of concrete;

- W0 is the elastic section modulus of the transformed section relative to the tensile edge, calculated as W0 = I0/y0, with y0 = h/2.

The moment of inertia of the transformed section I0 is given by:

where:

- n is the number of reinforcing bars within the calculated section range;

- Is is the moment of inertia of the transformed section;

- Ic is the moment of inertia of the original concrete section;

- D is the diameter of the equivalent circular concrete section converted from the steel bar based on equal area;

- d is the distance between the centroidal axis of the equivalent circular section and the centroidal axis of the calculated section of the composite panel;

- b is the width of the rectangular section of the composite panel;

- h is the height of the rectangular section of the composite panel.

For a panel with a rectangular opening, engineering practice often employs the global moment reduction method for simplified calculations: first, calculate the moment as if for a solid panel, then multiply by a reduction factor β. The formula for β is as follows:

where:

- Ah is the area of the opening;

- Aw is the total area of the panel;

- k is a coefficient (taken as 0.6 for two-way panels).

These formulations are standard and are adopted from the Code for Design of Concrete Structures (GB 50010-2010) [32] and the Plant Fiber Cement Wall Panels for Buildings (JC/T 2672-2022) [31].

Appendix A.2. Calculation of Ultimate Flexural Capacity Using Yield Line Theory

The ultimate flexural capacity of two-way panels reinforced with plant fiber was calculated using the yield line theory. The ultimate moments for ordinary reinforced concrete in the x- and y-directions are:

For plant fiber-reinforced concrete (PFRC), the plastic moments are enhanced by a factor km. Since the straw fibers in this study were not optimized, taking km as 1.15 is reasonable, as follows:

The virtual work equation is:

Setting We = Wi, the ultimate load pu is:

These equations are based on the yield line theory and enhanced with a fiber influence coefficient [19,41].

References

- Yan, B.J.; Yan, J.J.; Li, Y.X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L. Spatial distribution of biogas potential, utilization ratio and development potential of biogas from agricultural waste in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 126077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seglah, P.A.; Wang, Y.J.; Wang, H.Y.; Bi, Y.; Zhou, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Feng, X. Crop straw utilization and field burning in Northern region of Ghana. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Sankaran, R.; Chew, K.W.; Tan, C.H.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Chu, D.-T.; Show, P.-L. Waste to bioenergy: A review on the recent conversion technologies. BMC Energy 2019, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.Q.; Wang, H.M.; Chang, C.K.; Zeng, W.H.; Luo, Y.; Jiao, Y.F.; Zhang, W.T. Engineering Properties of Peat Soil with Different Fiber Contents in the Western Sichuan Plateau. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 50, 5709–5710. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Liu, B.H.; Zhang, F.; Cao, C.; Zhang, S.L.; Liao, X.L. Experimental Study on Frost Resistance of Rapeseed Straw Fiber Reinforced Concrete. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 49, 1003–1008. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, N.L.; Pawar, A.; Salvi, B.L. Comprehensive review on production and utilization of biochar. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, A.E.; Gao, B.; Zhang, M. Carbon dioxide capture using biochar produced from sugarcane bagasse and hickory wood. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 249, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Xiao, H.G.; Guan, S.; Zhang, J.; Yao, D. Technology and method for applying biochar in building materials to evidently improve the carbon capture ability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 123154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praneeth, S.; Guo, R.; Wang, T.; Dubey, B.K.; Sarmah, A.K. Accelerated carbonation of biochar reinforced cement-fly ash composites: Enhancing and sequestering CO2 in building materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 244, 118363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.Y.; Yang, J.L.; Gao, L.Z.; Kou, Y.; Su, S.; Yang, H.; Li, Z.; Gao, R.Z. Experimental Study on the Properties of Lightweight Rice Straw Fiber Cement-Based Solid Bricks. Build. Mater. Technol. Appl. 2020, 38, 5–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaggaf, R.; Maslehuddin, M.; Al-Osta, M.A. Properties and sustainability of treated crumb rubber concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 51, 104250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bheel, N.; Ali, M.; Kirgiz, M.S. Fresh and mechanical properties of concrete made of binary substitution of millet husk ash and wheat straw ash for cement and fine aggregate. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 13, 872–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, Z.J.; Wei, L.A.; Gong, Y. Experimental study on frost resistance of corn straw ash ecological porous concrete. J. Hydraul. Sci. Cold Reg. Eng. 2018, 1, 6–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xie, X.; Li, L. Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties and Durability of Graded Nano-SiO2 Modified Rice Straw Fiber Reinforced Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347, 128575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.S.U.; Umer, M.A.; Rashid, N.; Kim, I.; Han, J.-I. Sono-Assisted Sulfuric Acid Process for Economical Recovery of Fermentable Sugars and Mesoporous Pure Silica from Rice Straw. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 49, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosello, J.; Soriano, L.; Santamarina, M.P.; Akasaki, J.L.; Monzo, J.; Paya, J. Rice Straw Ash: A Potential Pozzolanic Supplementary Material for Cementing Systems. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 103, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazerian, M.; Sadeghiipanah, V. Cement-Bonded Particleboard with a Mixture of Wheat Straw and Poplar Wood. J. For. Res. 2013, 24, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canovas, M.F.; Selva, N.H.; Kawiche, G.M. New economical solutions for improvement of durability of Portland cement mortars reinforced with sisal fibers. Mater. Struct. 1992, 25, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonoli, G.H.D.; Rodrigues Filho, U.P.; Savastano, H., Jr.; Bras, J.; Belgacem, M.N.; Rocco Lahr, F.A. Cellulose modified fibres in cement-based composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2009, 40, 2046–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Bi, K.; Chen, W.; Pham, T.M.; Li, J. Towards next generation design of sustainable, durable, multi-hazard resistant, resilient, and smart civil engineering structures. Eng. Struct. 2023, 277, 115477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Garrido, A.J.; Navarro, I.J.; Garcia, J.; Yepes, V. A systematic literature review on modern methods of construction in building: An integrated approach using machine learning. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 73, 106725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaratnam, S.; Ngo, T.; Gunawardena, T.; Henderson, D. Performance review of prefabricated building systems and future research in Australia. Buildings 2019, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Giriunas, K.; Sezen, H.; Wu, G.; Feng, D.-C. State-of-the-art review and investigation of structural stability in multi-story modular buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 33, 101844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, H.-T.; Ngo, T.; Uy, B. A review on modular construction for high-rise buildings. Structures 2020, 28, 1265–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, R.M.; Ogden, R.G.; Bergin, R. Application of modular construction in high-rise buildings. J. Archit. Eng. 2012, 18, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajanayagam, H.; Poologanathan, K.; Gatheeshgar, P.; Varelis, G.E.; Sherlock, P.; Nagaratnam, B.; Hackney, P. A State-of-the-Art Review on Modular Building Connections. Structures 2021, 34, 1903–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, R.Y.M.; Jotikasthira, N.; Li, K.; Zeng, L. Experimental study on lightweight precast composite slab of high-titanium heavy-slag concrete. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6665388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaillon, L.; Poon, C.S. The evolution of prefabricated residential building systems in Hong Kong: A review of the public and the private sector. Autom. Constr. 2009, 18, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bories, C.; Borredon, M.-E.; Vedrenne, E.; Vilarem, G. Development of Eco-Friendly Porous Fired Clay Bricks Using Pore-Forming Agents: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 143, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.W.; Li, H.N.; Gardoni, P. Hybrid Bayesian-Copula-based risk assessment for tall buildings subject to wind loads considering various uncertainties. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 233, 109100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JC/T 2672-2022; Plant Fiber Cement Wall Panels for Buildings. China Building Materials Press: Beijing, China, 2022.

- GB 50010-2010; Code for Design of Concrete Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Zheng, X.W.; Hou, Y.Z.; Cheng, J.; Xu, S.; Wang, W.M. Rapid Damage Assessment and Bayesian-Based Debris Prediction for Building Clusters Against Earthquakes. Buildings 2025, 15, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.W.; Lv, H.L.; Fan, H.; Zhou, Y.B. Physics-Based Shear-Strength Degradation Model of Stud Connector with the Fatigue Cumulative Damage. Buildings 2022, 12, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.W.; Li, H.N.; Gardoni, P. Reliability-based design approach for high-rise buildings subject to earthquakes and strong winds. Buildings 2021, 244, 112771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50009-2012; Load Code for the Design of Building Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- GB/T 50080-2016; Standard for Test Methods of Performance on Fresh Concrete of China. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB/T 50152-2012; Standard for Test Method of Concrete Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- John, S.K.; Cascardi, A.; Verre, S.; Nadir, Y. RC-Columns Subjected to Lateral Cyclic Force with Different FRCM-Strengthening Schemes: Experimental and Numerical Investigation. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 23, 1561–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 21086-2019; Standard for Prefabricated Concrete Buildings of China. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Jones, L.L. Yield Line Theory for Slab Design; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).