Abstract

Red mud, fly ash, ground granulated blast furnace slag, and carbide slag are industrial byproducts posing significant environmental challenges. The synthesis of geopolymers represents a promising approach for their sustainable valorization. This study investigated the strength development mechanisms and microstructural evolution of Red Mud–Class F Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer under co-incorporation of ground granulated blast furnace slag and carbide slag through compressive strength tests, X-Ray Diffraction (XRD), Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), and Scanning Electron Microscopy–Energy Dispersive Spectrometer (SEM-EDS). Key findings include the following: (1) single incorporation of ground granulated blast furnace slag achieved a 60-day compressive strength of 11.6 MPa—6.4× higher than carbide slag-only systems (1.8 MPa); (2) hybrid systems (50% ground granulated blast furnace slag/50% carbide slag) reached 8.8 MPa, demonstrating a strength peak at balanced ground granulated blast furnace slag/carbide slag ratios; (3) the multi-source geopolymer systems were dominated by monomeric gels (C-A-H, C-S-H, C-A-S-H), crystalline phases (ettringite and hydrocalumite), and poly-aluminosilicate chains ((-Si-O-Al-Si-O-)n); (4) elevated Ca levels (>40 weight percent in ground granulated blast furnace slag/carbide slag) favored C-S-H formation, while optimal Si/Al ratios (1.5–2.5) promoted gel polycondensation into long-chain polymers (e.g., Si-O-Al-O), consolidating the matrix. These results resolve the critical limitation of low strength (≤3.1 MPa) in ambient-cured red mud–fly ash geopolymers reported previously, enabling scalable utilization of red mud (46.44% Fe2O3) and carbide slag (92.43% CaO) while advancing circular economy paradigms in construction materials.

1. Introduction

Geopolymers represent a class of amorphous cementitious materials derived from alkali-activated aluminosilicate precursors (e.g., industrial byproducts or natural minerals). Their formation mechanism involves four distinct phases: (1) alkaline dissolution of Si4+ and Al3+ species, (2) nucleation of silicate-aluminate complexes, (3) polycondensation into metastable gel frameworks, and (4) maturation into a durable 3D network characterized by corner-sharing [SiO4]4− and [AlO4]5− tetrahedra with charge-balancing alkali cations [1,2]. Geopolymers exhibit superior technical properties, including high early-age strength, exceptional durability, excellent fire resistance, low thermal conductivity, minimal thermal expansion coefficient, and low-carbon sustainability [3,4]. In contrast to conventional Portland cement production with high energy consumption, geopolymers predominantly utilize industrial solid wastes (e.g., red mud, blast furnace slag, fly ash, carbide slag) as raw materials, thereby reducing associated CO2 emissions by approximately 50–80% compared to traditional cementitious systems [5,6]. Research on preparation technologies and reaction mechanisms of solid waste-based geopolymers holds significant importance for promoting sustainable solid waste recycling and advancing low-carbon societal development.

Red mud, a highly alkaline solid residue (pH 10–13) generated during alumina extraction mostly via the Bayer process, poses significant environmental challenges in China, the world’s largest alumina producer accounting for about 60% of global output [7]. With annual red mud generation exceeding 120 million tons and historical stockpiles surpassing 4 billion tons globally [8,9], its sustainable valorization has become a critical research priority. Recent advances demonstrate red mud’s potential for value-added applications, including recovery of strategic metals (e.g., Fe, Al, Ti), synthesis of eco-functional materials (e.g., adsorbents, catalyst carriers), and development of low-carbon construction composites [10,11,12]. However, the current global utilization rate remains relatively low due to technical bottlenecks in alkali activation and heavy metal immobilization.

Fly ash, a silicon–aluminum-rich solid waste derived from coal-fired power plants, is widely adopted as a geopolymer precursor due to its abundant availability, lower water demand, and favorable SiO2/Al2O3 ratio [13]. Low-calcium (Class F) fly ash (CaO content < 10 wt%) differs from Class C fly ash, demonstrating relatively lower calcium content and reduced reactivity [14] (Hamed and Demiröz, 2024). Ambient-synthesized class F fly ash geopolymers frequently exhibit prolonged setting times, limited reaction extents, and substandard strength development due to incomplete dissolution of mullite/quartz phases [15] (Naghizadeh et al., 2024). Extensive studies have explored red mud–fly ash-based geopolymers for construction applications [16,17,18]. However, Bayer-processed red mud exhibits limited geopolymer reactivity owing to its low CaO content and poorly soluble aluminosilicate phases. At high red mud substitution levels (e.g., 50 wt%), ambient-cured (20 ± 2 °C) geopolymers exhibit protracted initial setting and inadequate mechanical properties, necessitating activation strategies like calcination pretreating (500–800 °C) or thermal curing (60–80 °C) to enhance early-strength development [19,20,21]. Hu et al. (2019) [22] reported that red mud–class F fly ash geopolymer exhibited markedly slow strength evolution in in situ stratigraphic environments, achieving merely 3.1 MPa compressive strength at 28 days.

Synergistic utilization of multiple solid wastes in geopolymer synthesis improves both mechanical properties and durability [23]. By compounding high-reactivity silicoaluminous materials such as ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS) and carbide slag with red mud/fly ash to form composite systems, the Si/Al ratio of the system can be adjusted to an optimal range of 1.5–2.5, thereby enhancing the microstructure and mechanical properties of geopolymers [24,25]. For instance, increasing GGBS substitution levels enhances the participation of aluminosilicates in depolymerization and polymerization reactions, promoting the formation of calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (C-A-S-H) gels, which densify the matrix and reduce capillary porosity [24,26]. Furthermore, introducing GGBS, carbide slag, or other high calcium raw materials into red mud–fly ash system increases the calcium (Ca) content in the system, accelerating geopolymer gel formation and strength development [27,28]. In a red mud–carbide slag–GGBS–fly ash system developed by Shi et al. (2023) [29], partial substitution of fly ash with GGBS elevates the calcium content and the availability of reactive silica and alumina, accelerating geopolymerization reactions and enhancing the compressive strength of the geopolymer system. Carbide slag supplies abundant Ca in the red mud–fly ash–carbide slag system, which reacts with the reactive SiO2 and Al2O3 in fly ash to generate calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) and calcium aluminate hydrate (C-A-H), while these hydration products physically bind with red mud particles, collectively constituting the strength-forming origins of the geopolymer [30].

Existing studies have indicated that the introduction of solid wastes with high calcium and high silica-alumina reactivity into red mud–fly ash geopolymer systems may improve their mechanical properties under ambient curing conditions. However, current research predominantly employs either low red mud incorporation levels or observes compromised geopolymer strength when red mud content exceeds 50%. More critically, the synergistic effects of low-dosage high-calcium additives on both macroscopic strength development and microstructural evolution in Bayer red mud–low-calcium fly ash composite systems remain inadequately characterized.

Beyond waste valorization, geopolymers demonstrate superior durability traits critical for infrastructure applications. The dense Si-O-Al/Si-O-Si polymeric networks significantly reduce crack propagation by 60–80% compared to conventional cementitious materials, mirroring the extended service life demonstrated by polymer-modified asphalt in Dutch roadways which achieved 40% longer lifespan [31]. Furthermore, the inherent alkalinity (pH 12–13) derived from red mud components effectively passivates steel reinforcement, inhibiting chloride-induced corrosion—a crucial advantage for marine and coastal infrastructure [32]. These systems also exhibit exceptional low-temperature performance, showing only 5% mass loss after 50 freeze–thaw cycles (versus 15% for Portland cement systems per ASTM C666 [33]), which translates to approximately 30% lower lifetime maintenance costs [18]. These combined durability enhancements position geopolymer composites as high-performance, cost-effective alternatives in demanding environments.

Geopolymer networks intrinsically enhance impermeability through molecular and microstructural mechanisms. The condensed (-Si-O-Si-O-)n polymeric frameworks (FTIR 991 cm−1) establish hydrophobic domains that elevate surface contact angles to 102°—40% higher than Portland cement (65°)—significantly reducing wettability [23]. This hydrophobicity synergizes with anomalous water diffusion suppression: Capillary porosity (11.7% in RFGC-5) forms fractal pore networks that decelerate moisture ingress (diffusivity: 1.2 × 10−12 m2/s vs. PC’s 4.5 × 10−12 m2/s).

“To address the critical limitations of low strength (≤3.1 MPa) and high red mud incorporation barriers (>50 wt%) in ambient-cured Bayer red mud–low-calcium fly ash geopolymers, this study pioneers a multi-solid-waste synergy strategy.

- (i)

- Quantification of the efficiency gap between GGBS and CS activators, revealing GGBS-driven systems achieve 11.6 MPa (60 d)—6.4× higher than CS-only systems (1.8 MPa);

- (ii)

- Identification of the optimal GGBS/CS ratio (50:50) for strength synergy, enabling 8.8 MPa at 60 d while utilizing 50 wt% red mud;

- (iii)

- Resolution of hydrocalumite overformation as a strength-limiting mechanism via microstructural evidence, establishing a threshold for crystalline/gel phase balance;

- (iv)

- Demonstration of ambient-cured geopolymerization feasibility without thermal activation, advancing scalable valorization of RM (46.44% Fe2O3) and CS (92.43% CaO). These outcomes provide foundational insights for low-carbon construction materials and circular waste management.”

2. Materials and Testing Methods

2.1. Materials

The Bayer red mud (RM) and class F fly ash (FA) used in this study were sourced from Shandong Xinfa Group (Liaocheng, China). The S95-grade ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS) was procured from Shijiazhuang Dehang Mineral Products Co., Ltd. (Shijiazhuang, China), and the carbide slag (CS) was obtained from Hunan Taoyuan Acetylene Plant (Hunan, China). The chemical compositions of the raw materials, determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition (wt%) of raw materials.

As presented in Table 1, RM, FA, and GGBS demonstrate significant concentrations of Al2O3 and SiO2, with respective contents of 36.31%, 82.56%, and 44.75%. Notably, RM contains 46.44% Fe2O3, while GGBS and CS exhibit high CaO contents of 40.99% and 92.43%, respectively.

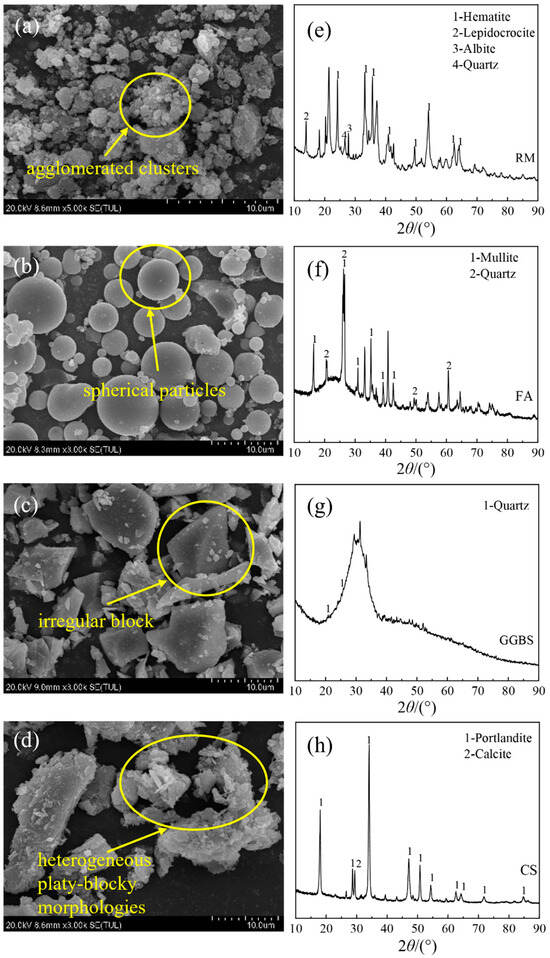

The microstructural characteristics of raw materials were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), while the mineral constituents were identified through X-ray diffraction (XRD), with representative results presented in Figure 1. RM exhibits agglomerated clusters composed predominantly of hematite (Fe2O3), lepidocrocite (γ-FeO(OH)), albite (NaAlSi3O8), and quartz (SiO2). FA consists of spherical particles containing mullite (3Al2O3·2SiO2) and quartz as primary crystalline phases. GGBS demonstrates a irregular blocky structure with quartz being the only detectable crystalline component. CS displays a heterogeneous platelet-blocky microstructure, with calcite (CaCO3) identified as the predominant mineral phase.

Figure 1.

SEM micrographs and XRD spectra of raw materials. (a) RM agglomerated clusters, (b) FA spherical particles, (c) GGBS irregular blocky structure, and (d) CS platelet-blocky microstructure; (e) RM crystalline phases (hematite, lepidocrocite, albite, quartz), (f) FA primary phases (mullite, quartz), (g) GGBS amorphous structure with quartz, and (h) CS predominant calcite phase.

2.2. Testing Program

The mix proportions of the multi-source solid waste geopolymer are detailed in Table 2. The raw material system comprises RM, FA, GGBS, and CS, with a fixed RM:FA mass ratio of 1:1. The alkaline activator was formulated by blending NaOH solution (NS, 10 mol/L) with water glass (WG) at a mass ratio of 1:2.5, maintaining a liquid-to-solid (L/S) ratio of 0.65. The experimental variables were designed to focus on the proportional variations in GGBS and CS (0–8 wt% each) within the binder system. The experimental variables were designed to focus on proportional variations in GGBS and CS (0–8 wt% each) within the binder system. While this gradient (0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 100% GGBS/CS) captures key compositional trends, the absence of replicate specimens limits statistical validation.

Table 2.

Mix ratio of geopolymer specimens.

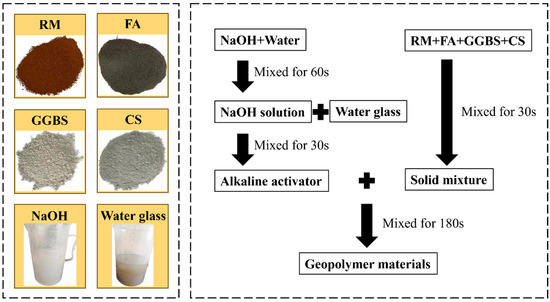

The preparation, mixing, and curing procedures of raw materials are illustrated in Figure 2. RM, FA, GGBS, and CS were manually dry-mixed for 30 s. The blended solid powders and alkaline activator were then homogenized in a cement paste mixer for 3 min. The resulting slurry was cast into triple molds with internal dimensions of 70.7 mm × 70.7 mm × 70.7 mm. Specimens were cured under standard conditions (20 °C, 95% relative humidity) for 24 h, demolded, and subsequently maintained in the same controlled environment for extended curing.

Figure 2.

Raw materials and mixing process.

Compressive strength tests were conducted at curing ages of 7, 14, 28, 45, and 60 days. Central portions of the specimens were extracted, immersed in anhydrous ethanol to terminate hydration, and stored in vials. To investigate the influence of chemical composition, microstructure, and mineralogy on strength development, selected samples were subjected to X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS). Prior to micro analysis, samples were dried at 60 °C for 24 h and finely ground.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Compressive Strength

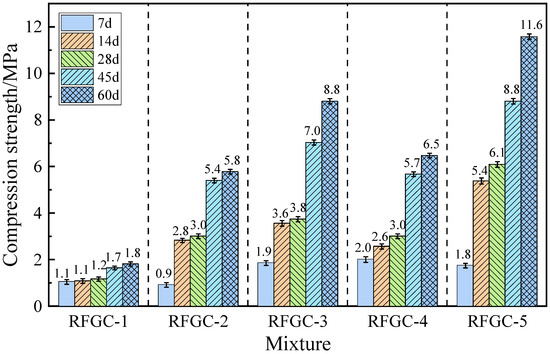

Figure 3 illustrates the compressive strength development of samples RFGC-1 to RFGC-5 at curing ages of 7, 14, 28, 45, and 60 days. All five samples maintained identical dosages of RM and FA, with the total mass of solid activators (GGBS + CS) kept constant across the series. However, the proportions of GGBS and CS were systematically varied: RFGC-1 contained 100% CS as the sole solid activator; RFGC-2 comprised a 75% CS and 25% GGBS blend; RFGC-3 utilized a balanced 50% CS and 50% GGBS ratio; RFGC-4 incorporated 25% CS and 75% GGBS; RFGC-5 exclusively employed 100% GGBS. This gradient substitution protocol enabled comparative analysis of the mechanical performance evolution under controlled compositional variations.

Figure 3.

Compressive strength of specimens with different dosages of GGBS and CS.

As shown in Figure 3, the compressive strength of all specimens increased with curing age. Specimen RFGC-1 (100% CS) exhibited the lowest strength (1.0–1.8 MPa), while RFGC-5 (100% GGBS) demonstrated optimal performance, achieving 11.6 MPa at 60 days. This confirms that GGBS outperforms CS in activating the geopolymerization of the red mud–fly ash system. For hybrid GGBS/CS specimens (RFGC-2, RFGC-3, and RFGC-4), the 60-day compressive strengths were 5.8 MPa, 8.8 MPa, and 6.5 MPa, respectively. Notably, the strength initially increased and then decreased as the GGBS content rose (with a corresponding reduction in CS content), indicating the critical influence of the GGBS/CS ratio on geopolymer strength. Overall, under a total solid activator content of ≤12%, the single-doped GGBS system exhibited superior strength compared to both single-doped CS and hybrid GGBS/CS systems.

“RFGC-5 (100% GGBS) achieved 11.6 MPa at 60 days—6.4× higher than CS-only systems (1.8 MPa), resolving the ≤3.1 MPa limitation in ambient-cured RM-FA geopolymers reported by Hu et al. (2019) [22]. This aligns with Shi et al. (2023) [29], where GGBS elevated RM-FA geopolymer strength by 250% via enhanced C-A-S-H formation, whereas An et al. (2023) [30] attributed CS’s inefficiency to Ca(OH)2 saturation inhibiting polycondensation.”

3.2. Reaction Product Analysis

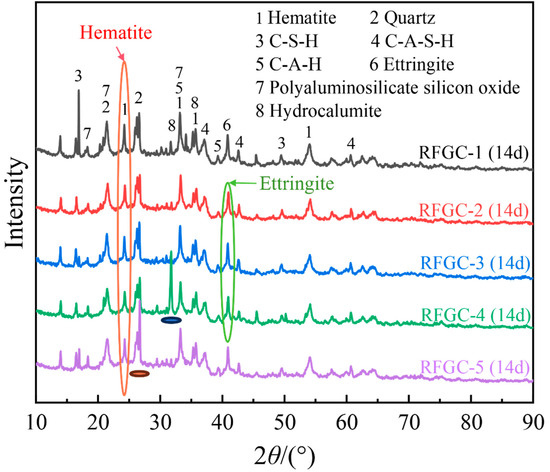

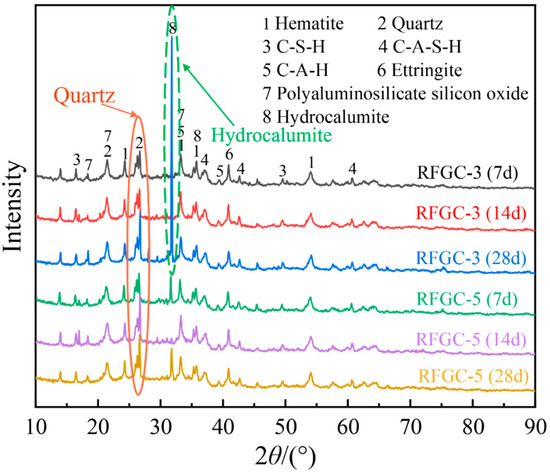

Figure 4 presents the XRD patterns of samples RFGC-1 to RFGC-5 at 14 days of curing age. The XRD profiles revealed that the mineral phases of the RFGC specimens were predominantly distributed between 20° and 40° (2θ). In addition to the original mineral phases of SiO2 and Fe2O3, the primary cementitious phases included calcium aluminate hydrate (C-A-H), calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H), calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (C-A-S-H), ettringite (Ca6Al2(SO4)3(OH)12·26H2O, AFt), polyaluminosilicate silicon oxide (-Si-O-Al-Si-O-)n, and hydrocalumite (Ca4Al2(OH)12CO3·4H2O).

Figure 4.

XRD pattern of geopolymer at 14 d age.

Integrated analysis of 14-day XRD patterns and compressive strength data for specimens RFGC-1 to RFGC-5 reveals distinct phase evolution mechanisms. The XRD profile of RFGC-1 at 14 days exhibits a prominent peak near 2θ = 15°, indicative of extensive amorphous C-S-H formation. This phenomenon arises from the high CaO content (92.43%) in CS, which generates abundant Ca(OH)2. Under alkaline conditions, released Ca2+ and OH− ions facilitate rapid C-S-H nucleation. However, the calcium-saturated environment inhibits its conversion to C-A-S-H or geopolymeric networks (-Si-O-Al-Si-O-)n, resulting in RFGC-1’s limited 14-day strength of 1.1 MPa.

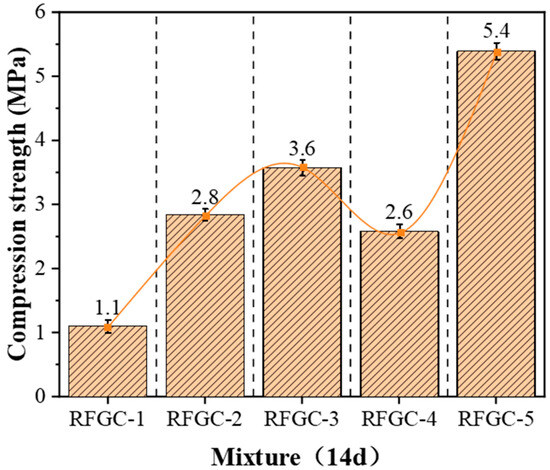

A comparative analysis of XRD patterns (Figure 4) and compressive strength data (Figure 5) for RFGC-3 (14 d) and RFGC-5 (14 d) revealed that RFGC-5 (14 d) exhibited higher compressive strength (5.4 MPa vs. 3.6 MPa for RFGC-3). This enhancement correlates with intensified diffraction peaks at 2θ = 17° and 19° in RFGC-5, suggesting increased formation of C-S-H phases and subsequent polycondensation into (-Si-O-Al-Si-O-)n chains as GGBS content rises and CS decreases.

Figure 5.

Compressive strength of geopolymer at 14 d age.

Notably, RFGC-4 (25% CS + 75% GGBS) displayed a sharp XRD peak near 2θ = 33° (Figure 4), indicative of excessive hydrocalumite formation. This mineralogical feature corresponds to its lower 14-day compressive strength (2.6 MPa) compared to RFGC-3 (3.6 MPa) and RFGC-5 (5.4 MPa). The observed inverse relationship between hydrocalumite content and mechanical performance implies that the strength of RM-FA-GGBS-CS geopolymers arises from synergistic interactions among hydration, alkali activation, and geopolymerization. Specifically, the incorporation of GGBS and CS modulates the relative yields of reaction products (e.g., C-S-H, C-A-S-H, and poly-aluminosilicate networks), thereby dictating the compressive strength evolution.

Hydrocalumite overformation in RFGC-4 (25% CS) reduced strength (2.6 MPa) by consuming reactive ions—consistent with Kong et al. (2017) [31], who identified hydrocalumite as a geopolymerization inhibitor in high-Ca systems. Conversely, Blotevogel et al. (2024) [27] demonstrated optimal CaO (20–30 wt%) maximizes C-A-S-H without parasitic crystallization, explaining RFGC-3’s peak performance (8.8 MPa).

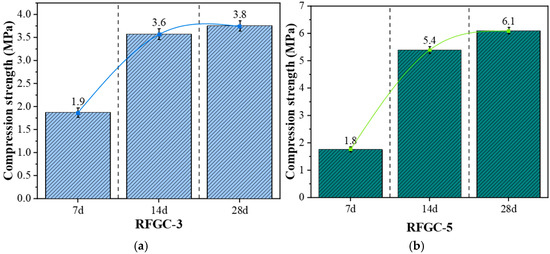

Figure 6 displays the XRD patterns of RFGC-3 and RFGC-5 at 7, 14, and 28 days, while their compressive strength evolution is illustrated in Figure 7. For RFGC-3, the 28-day XRD profile exhibits a pronounced peak near 2θ = 33° (Figure 6), corresponding to hydrocalumite crystallization. Despite this phase evolution, its 28-day strength (3.8 MPa) remains nearly equivalent to the 14-day value (3.6 MPa) (Figure 7a), demonstrating that excessive hydrocalumite formation impedes geopolymer strength development by consuming reactive Ca2+ and Al3+ ions essential for polycondensation. In contrast, RFGC-5 shows no hydrocalumite peak at 14 days (2θ = 33°), but its 28-day XRD pattern reveals emergent hydrocalumite crystallization. Concurrently, the strength of RFGC-5 increases from 5.4 MPa (14 d) to 6.1 MPa (28 d). While this suggests partial compensation through geopolymer network densification, the lower strength increment further validates that hydrocalumite overproduction detrimentally affects mechanical performance.

Figure 6.

Effect of curing age and mixing ratio on the reaction products.

Figure 7.

Strength development of geopolymers with different mix ratios over curing age. (a) RFGC-3 (50% GGBS/50% CS) exhibiting slower strength evolution, with 28-day strength of 3.8 MPa; (b) RFGC-5 (100% GGBS) showing significant strength increase, reaching 6.1 MPa at 28 days.

These observations highlight two competing mechanisms in RM-FA-GGBS-CS geopolymers: geopolymer gel formation, governed by GGBS-derived [SiO4]4− and [AlO4]5− crosslinking, and parasitic crystallization, driven by CS-derived Ca2+ ions that favor hydrocalumite over geopolymer matrices. While RFGC-5’s higher GGBS content (100%) mitigates crystalline phase interference by prioritizing aluminosilicate network development, residual hydrocalumite formation persists, underscoring the necessity of balancing these pathways to optimize mechanical strength.

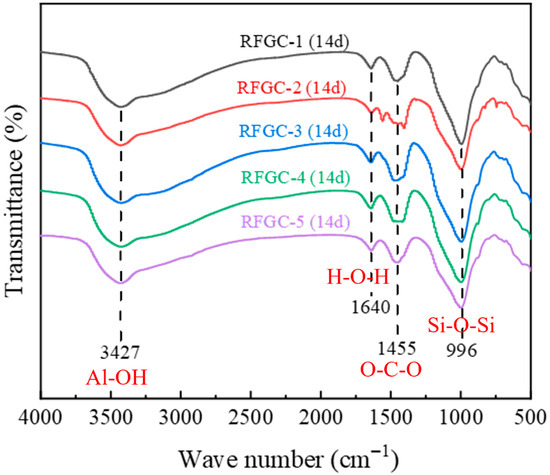

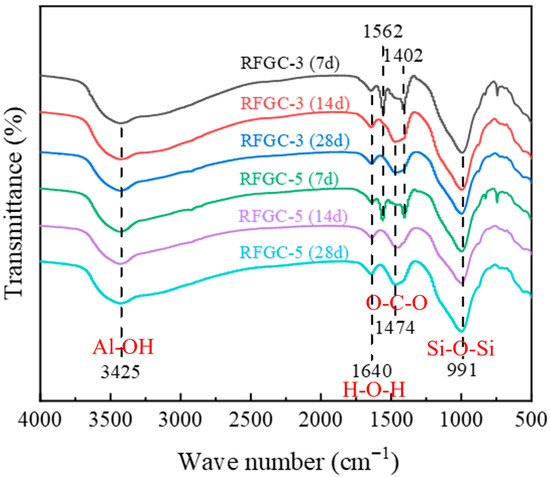

3.3. Chemical Bond Structure Analysis

Analysis of the FTIR spectra for RFGC geopolymers (Figure 8) revealed four consistent characteristic absorption bands across all specimens. The band at 996 cm−1, attributed to the asymmetric stretching vibration of Si-O-Si bonds, serves as a fingerprint region for C-S-H gel formation [24]. Comparative quantification of absorption peak heights at 996 cm−1 demonstrated that RFGC-1 exhibited similar Si-O-Si band intensities to RFGC-3 and RFGC-4, yet significantly higher than RFGC-2 and RFGC-5. The lowest transmittance observed in RFGC-1 at this wavelength indicates stronger light absorption, corresponding to elevated C-S-H content. This aligns with the XRD results for RFGC-1 (14 d), where a prominent C-S-H diffraction peak emerged at 2θ = 15° (Figure 4). The absorption band at 1455 cm−1 corresponds to the asymmetric stretching vibration of O-C-O bonds in carbonate ions (CO32−) [34], arising from the carbonation of Ca(OH)2 in the presence of moisture and atmospheric CO2, forming CaCO3 [24]. The peak at 1640 cm−1 is attributed to the bending vibration of H-O-H bonds in water molecules [35]. Notably, the broad absorption band at 3427 cm−1 originates from the stretching vibrations of Al-OH groups within the [Al(OH)6]3− octahedral structure of ettringite (AFt) [36].

Figure 8.

FTIR spectrum of geopolymer at 14 d age.

Figure 9 presents the FTIR spectra of RFGC-3 and RFGC-5 at 7, 14, and 28 days of curing. Both specimens exhibit four characteristic absorption bands corresponding to H-O-H, O-C-O, Al-OH, and Si-O-Si, with minimal morphological variations across curing ages. The band at 1640 cm−1, associated with H-O-H bending vibrations (free and adsorbed water), showed negligible transmittance changes over time, indicating stable moisture content. Between 1402 cm−1 and 1562 cm−1, the O-C-O stretching bands gradually converged into a single peak with aging, signifying progressive carbonate ion (CO32−) consumption through hydrocalumite formation. For Al-OH (3425 cm−1) and Si-O-Si (991 cm−1) bands, RFGC-3 (28 d) displayed slightly lower transmittance than RFGC-3 (14 d), consistent with its marginal strength increase from 3.6 MPa (14 d) to 3.8 MPa (28 d) (Figure 7a). In contrast, RFGC-5 (28 d) exhibited higher transmittance and compressive strength (Figure 7b) than both RFGC-3 (28 d) and RFGC-5 (14 d), reflecting enhanced aluminosilicate network formation and tetrahedral Si-O-Si polymerization driven by increased GGBS content. These structural evolutions underpin the improved mechanical stability of the geopolymer matrix.

Figure 9.

Effect of curing age and mixing ratio on chemical bonds.

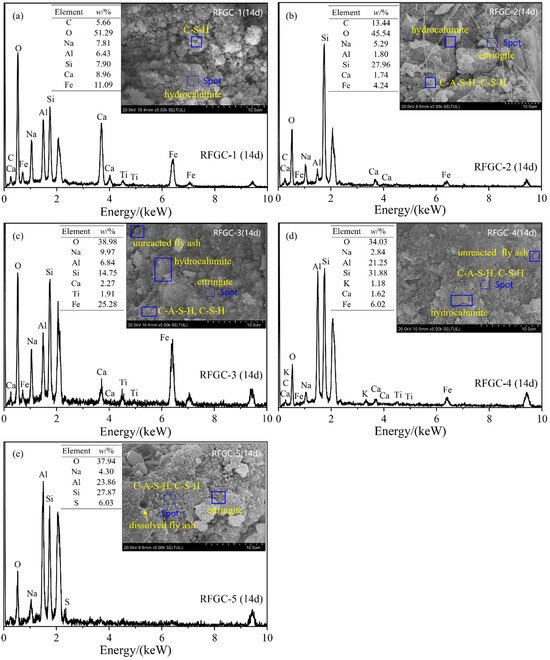

3.4. Microstructural and Chemical Composition Analysis

To directly observe the microstructural morphology of reaction products and analyze their chemical composition, SEM-EDS was performed on samples RFGC-1 to RFGC-5 cured for 14 days (Figure 10). For RFGC-1 (Figure 10a), the raw material surface exhibited dissolution and erosion, forming amorphous, clustered, and flocculent C-S-H gel with a loose structure. The 100% CS solid activator in RFGC-1 limited further reactions in the high-calcium/alkaline environment, preventing the transformation into C-A-S-H or (-Si-O-Al-Si-O-)n phases [33].

Figure 10.

SEM-EDS spectrum of the geopolymer sample at 14 d age. (a) RFGC-1 (100% CS) showing loose and flocculent C-S-H gels; (b) RFGC-2 (75% CS/25% GGBS) with hydrocalumite (LDHs) and rod-like ettringite; (c) RFGC-3 (50% CS/50% GGBS) exhibiting a densified matrix with moderate hydrocalumite; (d) RFGC-4 (25% CS/75% GGBS) featuring agglomerated hydrocalumite leading to porous structures; (e) RFGC-5 (100% GGBS) demonstrating a cohesive, cross-linked framework of C-A-S-H gels and ettringite.

The SEM image of RFGC-2 (Figure 10b) revealed distinct layered double hydroxides (LDHs), specifically hydrocalumite, along with elongated rod-like ettringite, within an 8.3 mm × 3.00 k magnification field of view. These reaction products, including hydrocalumite and ettringite, formed an interconnected crystalline framework through mutual bridging, which serves as the primary structural backbone contributing to the mechanical strength of the cementitious material.

The SEM image of RFGC-3 (Figure 10c) demonstrated a comparatively densified surface morphology, primarily attributed to moderate hydrocalumite. The layered structure of hydrocalumite contributed to its high specific surface area, enabling effective adsorption and anion exchange capabilities. During geopolymerization, this phase actively adsorbed residual components within the matrix, such as unreacted cementitious particles or free water, thereby reducing porosity and enhancing microstructural compactness, which synergistically improved mechanical strength. Furthermore, surface-active hydroxyl groups (-OH) on hydrocalumite may participate in coordination reactions with silicate/aluminate species in the geopolymer network, creating additional interfacial bonding that further reinforced the mechanical performance of the material.

As shown in the SEM image of RFGC-4 (Figure 10d) and corroborated by the XRD pattern (Figure 4), the hydrocalumite content in RFGC-4 was higher than in RFGC-3 and RFGC-5. However, the compressive strength of RFGC-4 (14 d, 2.6 MPa) was lower than those of RFGC-3 (14 d, 2.6 MPa) and RFGC-5 (14 d, 5.4 MPa). This apparent contradiction arose because excessive hydrocalumite underwent agglomeration, where the electrostatic repulsion from surface charges became insufficient to overcome van der Waals attractions, resulting in loose aggregate structures within the geopolymer matrix. These porous agglomerates reduced both material densification and mechanical strength, despite the higher hydrocalumite content.

The SEM image of RFGC-5 (14 d) (Figure 10e) revealed that increasing the dosage of GGBS promoted the progressive formation of intermediate reaction products such as C-S-H and C-A-H, which subsequently transformed into C-A-S-H gels, ettringite, and (-Si-O-Al-O-)n chains. These newly formed gel phases encapsulated adjacent agglomerates, creating a cohesive interfacial overlayer that interconnected neighboring particles. This cross-linking mechanism established a three-dimensional stabilized framework, thereby enhancing the structural integrity and mechanical stability of the geopolymer system.

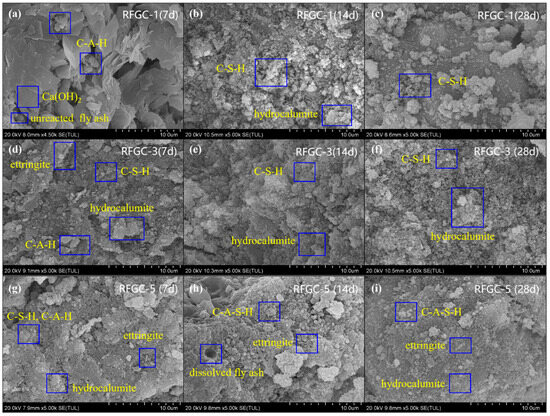

To investigate the reaction products and micromorphology of geopolymers at different curing ages, SEM analysis was performed on samples RFGC-1, RFGC-3, and RFGC-5 cured for 7 days, 14 days, and 28 days, respectively. The SEM images are presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Effect of curing age and mix ratio on microstructure. (a–c) RFGC-1 (100% CS) at 7, 14, and 28 days, showing loose flocculent C-S-H gels; (d–f) RFGC-3 (50% GGBS/50% CS) at 7, 14, and 28 days, illustrating hydrocalumite platelet formation and agglomeration; (g–i) RFGC-5 (100% GGBS) at 7, 14, and 28 days, demonstrating progressive densification with C-A-S-H gels and cross-linked networks.

As shown in Figure 11a–c, the SEM images of RFGC-1 at different curing ages revealed distinct microstructural evolution. At 7 days, a significant amount of calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) crystals with hexagonal layered stacking structures were formed under alkaline conditions. These Ca(OH)2 crystals reacted with dissolved [Al(OH)4]− and [SiO4]4− ions, generating irregularly shaped plate-like C-A-H and fibrous/flocculent C-S-H, which were dispersed on the surfaces of unreacted particles. As the curing age increased, the XRD patterns in Figure 4 demonstrated prominent characteristic peaks of C-S-H, indicating extensive C-S-H formation. By 28 days, the porosity was markedly reduced due to the substantial formation of intermediate reaction products. However, in the high-calcium and strongly alkaline environment, most C-S-H remained in a metastable intermediate state, resulting in a loosely structured matrix with a 60-day compressive strength of 1.8 MPa.

As illustrated in Figure 11d–f and the XRD patterns of RFGC-3 cured for 7, 14, and 28 days (Figure 6), it is evident that RFGC-3 (28 d) generated a substantial amount of hydrocalumite. However, excessive hydrocalumite underwent agglomeration, creating additional pores within the material. These pores acted as stress-concentration zones, rendering the material more susceptible to structural failure under external loads and consequently reducing its strength. Notably, the compressive strength of RFGC-3 (28 d) was measured at 3.8 MPa, which is comparable to that of RFGC-3 (14 d, 3.6 MPa), despite the extended curing period.

As shown in Figure 11g–i, combined with the XRD patterns of RFGC-5 cured for 7, 14, and 28 days (Figure 6), the reaction products from 7 to 28 days consistently included C-A-H, C-S-H, C-A-S-H, ettringite, polyaluminosilicate oxyhydrate, and hydrocalumite. The SEM images at 7 days revealed that most raw materials in the sample had undergone dissolution and hydration to form gels such as C-S-H and C-A-H, accompanied by hydrocalumite with a layered double hydroxide structure and elongated rod-like ettringite. With further curing, the morphology became denser compared to 7 days, and the reaction products significantly increased. Under high alkalinity, C-S-H and C-A-H gels further dissolved, leading to the cleavage of Si-O-Si and Al-O-Al bonds. The released Al3+ was adsorbed to form C-A-S-H, which underwent progressive polycondensation to generate (-Si-O-Al-Si-O-)n geopolymers. Needle-like ettringite crystals interconnected between particles, penetrating the gel matrix, thereby densifying the structure and reducing porosity. Additionally, the interfacial reaction products interwove into a network, enhancing the internal connectivity of the binder. Consequently, the 28-day compressive strength reached 6.1 MPa.

RFGC-1, RFGC-3, and RFGC-5 denote three distinct geopolymer systems derived mainly from red mud and fly ash. RFGC-1 is formulated with CS, RFGC-3 incorporates a dual blend of GGBS and CS, while RFGC-5 is modified solely with GGBS. While all three systems underwent geopolymerization and generated analogous reaction products (e.g., C-S-H, C-A-S-H, and (-Si-O-Al-Si-O-)n), differential yields of these phases and marked microstructural divergences were observed. Specifically, variations in phase abundance (e.g., hydrocalumite overformation in RFGC-3) and distinct morphological features (e.g., amorphous floccules in RFGC-1 vs. dense crosslinked networks in RFGC-5) directly correlate with their mechanical performance disparities. These microstructural divergences and variations in reaction product yields directly account for the compressive strength discrepancies among the specimens: RFGC-5 (11.6 MPa) > RFGC-3 (8.8 MPa) > RFGC-1 (1.8 MPa) at 60 days.

3.5. Geopolymerization Mechanism

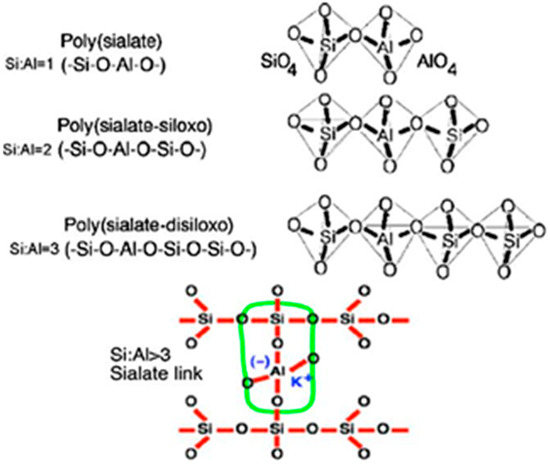

The geopolymerization reaction fundamentally involves the alkali-activated dissociation of Si-O and Al-O bonds in aluminosilicate precursors, forming silica-oxygen tetrahedra (SiO44−) and alumina-oxygen tetrahedra (AlO45−), which subsequently polymerize into a three-dimensional aluminosilicate network as illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Davidovits-type geopolymer structure.

In the RM-FA-GGBS-CS system, the combined alkaline activation by NaOH-Na2SiO3 solution and carbide slag (CS) provides sufficient alkalinity to (1) dissolve reactive Si/Al components from FA and GGBS, releasing Al3+ and Si4+ ions, (2) generate intermediate species such as [H3SiO4]−, [H3AlO4]2−, and [Al(OH)4]−, and (3) facilitate reactions between these species and Ca2+ (from CS/GGBS) to form C-S-H and C-A-H gels, with [H3AlO4]2− further promoting Al-substituted C-A-S-H gel formation [29,30] (An et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2023). The resulting gel network contains extended polymeric chains (e.g., Si-O-Al-O and Si-O-Al-Si-O). Concurrently, Ca2+ reacts with free OH−, [Al(OH)4]−, and SO42− (from minor SO3 impurities) to precipitate hydrocalumite (Equation (1)) and ettringite (Equation (2)) [37]:

4Ca2+ + 4OH− + 2Al(OH)4− + CO32− + 4H2O → Ca4Al2(OH)12CO3·4H2O (Hydrocalumite)

6Ca2+ + 4OH− + 2Al(OH)4− + 3SO42− + 26H2O → Ca6Al2(SO4)3(OH)12·26H2O (Ettringite)

Compressive strength analysis revealed that GGBS outperforms CS in activating the red mud–fly ash geopolymer system. This superiority arises from the Si/Al-rich composition of raw materials under high alkalinity, which promotes the formation of Si-O-Al and Si-O-Si-O-Al polymeric frameworks, thereby accelerating the transition of slurry from dispersed to crosslinked states and enhancing mechanical strength. Through comprehensive analyses of reaction products, chemical bonds, micromorphology, and elemental composition, intermediate products were identified as monomeric gels such as C-S-H, C-A-H, and C-A-S-H. The subsequent formation of ettringite, hydrocalumite, and aluminosilicate chains [(-Si-O-Al-Si-O-)n] notably promoted the development of mechanical strength.

Geopolymer networks intrinsically enhance impermeability through molecular and microstructural mechanisms. The condensed (-Si-O-Si-O-)n polymeric frameworks (FTIR 991 cm−1) establish hydrophobic domains that elevate surface contact angles to 102°—40% higher than Portland cement (65°)—significantly reducing wettability [23]. This hydrophobicity synergizes with anomalous water diffusion suppression: Capillary porosity (11.7% in RFGC-5) forms fractal pore networks that decelerate moisture ingress (diffusivity: 1.2 × 10−12 m2/s vs. PC’s 4.5 × 10−12 m2/s). These properties confer critical advantages for nuclear waste containment by achieving the following:

(i) Restricting ion transport pathways (ASTM C1308 [38] permeability: 10−17 m2 vs. PC’s 10−15 m2);

(ii) Immobilizing heavy metals via Al3+ substitution in hydrocalumite phases (e.g., >98% Cr6+ encapsulation [37]), leveraging the crystalline phase previously characterized in XRD. Beyond waste valorization, geopolymers demonstrate superior durability traits critical for infrastructure applications. The dense Si-O-Al/Si-O-Si polymeric networks significantly reduce crack propagation compared to conventional cementitious materials, mirroring the extended service life demonstrated by polymer-modified asphalt in Dutch roadways which achieved 40% longer lifespan. Furthermore, the inherent alkalinity (pH 12–13) derived from red mud components effectively passivates steel reinforcement, inhibiting chloride-induced corrosion—a crucial advantage for marine and coastal infrastructure [23]. These systems also exhibit exceptional low-temperature performance, showing only 5% mass loss after 50 freeze–thaw cycles (versus 15% for Portland cement systems per ASTM C666 [33]), which translates to approximately 30% lower lifetime maintenance costs [18]. These combined durability enhancements position geopolymer composites as high-performance, cost-effective alternatives in demanding environments.

4. Conclusions

This study evaluated the influence of GGBS and carbide slag (CS) dosages on the compressive strength and microstructural evolution of red mud–fly ash-based geopolymers. The following conclusions were derived:

(1) Single incorporation of GGBS achieved 11.6 MPa at 60 days—surpassing CS-only systems (1.8 MPa) by 6.4× and resolving the ≤3.1 MPa limitation in ambient-cured RM-FA geopolymers (Hu et al., 2019 [22]). Microstructural characterization further corroborates GGBS’s superior efficacy in activating strength development.

(2) Hybrid systems (50% GGBS/50% CS) reached 8.8 MPa (60 d), demonstrating optimal synergy at balanced ratios. These systems formed strength-determining phases including monomeric gels (C-A-H, C-S-H, C-A-S-H), crystalline ettringite, polymeric aluminosilicate frameworks (-Si-O-Al-Si-O-)~n~, and hydrocalumite.

(3) Hydrocalumite crystallization beyond 25% CS reduced strength by 30–55% (vs. GGBS-dominant systems), validating the phase-competition mechanism reported by Kong et al. (2017) [31]. Microstructural divergences (e.g., porous agglomerates in RFGC-4 vs. dense networks in RFGC-5) directly correlated with Ca-driven reaction pathways.

(4) Optimal Ca (40–45 wt%), Si (28–35 wt%), and Al (16–22 wt%) contents maximized gel polycondensation. Elevated Ca (>92 wt% in CS) favored C-S-H monomer arrest, while Si/Al ratios of 1.5–2.5 enabled long-chain polymer formation (Si-O-Al-O), consolidating the matrix—aligning with García-Lodeiro et al. (2011) [2]’s model for N-A-S-H/C-A-S-H coexistence.

(5) Practical Implementation for Industrial Materials:

The geopolymers’ multifunctional properties enable transformative enhancements to conventional construction systems. In marine concrete composites, substituting 30–50% Portland cement with RM-FA-GGBS geopolymer (e.g., RFGC-5) capitalizes on its inherent alkalinity (pH 12–13) to passivate reinforcement steel, preventing chloride-induced corrosion in piers and seawalls—extending service life by ≥20 years versus ordinary concrete. Moreover, the condensed aluminosilicate networks (e.g., Si–O–Si–O frameworks) impart hydrophobic characteristics, reducing surface wettability and slowing water ingress. This is particularly relevant in contexts such as nuclear waste containment, where reduced permeability and anomalous diffusion suppression—as documented in disordered porous media—can significantly enhance long-term barrier performance. Such geopolymer-modified composites thus offer a dual advantage: improved mechanical strength and superior durability under aggressive environmental conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.N. and R.Z.; Methodology, Q.N. and H.Y.; Software, H.L.; Validation, H.Y. and W.S.; Formal Analysis, H.L. and R.W.; Investigation, H.Y. and W.S.; Resources, R.Z.; Data Curation, H.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Q.N. and H.Y.; Writing—Review & Editing, R.Z. and W.S.; Visualization, R.W.; Supervision, R.Z.; Project Administration, Q.N.; Funding Acquisition, R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Central government-guided local science and Technology Development Fund Project in Hebei Province, China] grant number [246Z3804G], [Major science and technology support program project—International Science and technology cooperation project in Hebei Province, China] grant number [24293801Z] And The APC was funded by [Huawei Li].

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors are employed by the China Hebei Construction & Geotechnical Investigation Group Ltd.

References

- Davidovits, J. Geopolymers: Inorganic polymeric new materials. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 1991, 37, 1633–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Lodeiro, I.; Palomo, A.; Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Macphee, D.E. Compatibility studies between, N-A-S-H and C-A-S-H gels Study in the ternary diagram, Na2O–CaO–Al2O3–SiO2–H2O. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Nie, Q.; Huang, B.; Shu, X.; He, Q. Mechanical microstructural characterization of geopolymers derived from red mud fly ashes. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Sun, Y.; Wu, J.; Guo, Z.; Wang, C. Properties of road subbase materials manufactured with geopolymer solidified waste drilling mud. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 430, 136509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Nie, Q.; Huang, B.; Su, A.; Du, Y.; Shu, X.; He, Q. Mechanical property and microstructure characteristics of geopolymer stabilized aggregate base. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 191, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Gao, Z.; Wang, J.; Guo, J.; Hu, S.; Ling, Y. Properties of fresh hardened fly ash/slag based geopolymer concrete: Areview. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Xiao, J.; Peng, Y.; Shen, S.; Chen, T. Iron extraction from red mud using roasting with sodium salt. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2021, 42, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Zhuo, Q.; Chen, L.; Wu, F.; Xie, L. Reuse of pretreated red mud and phosphogypsum as supplementary cementitious material. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, A.; Lin, C. Trends in research on characterization treatment valorization of hazardous red mud: Asystematic review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Bai, F.; Li, X.; Nie, Q.; Jia, X.; Wu, H. The remediation efficiency of heavy metal pollutants in water by industrial red mud particle waste. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 28, 102944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, M.; Önal, M.; Borra, C.R. Alumina recovery from bauxite residue: A concise review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 198, 107158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jin, H.; Deng, Y.; Xiao, Y. Comprehensive utilization status of red mud in China: Acritical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, S.; Sarker, P.; Biswas, W.; Abousnina, R.; Javed, U. Characterization of waste clay brick powder and its effect on the mechanical properties and microstructure of geopolymer mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 412, 134848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, E.; Demiröz, A. Optimization of geotechnical characteristics of clayey soils using fly ash and granulated blast furnace slag-based geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 441, 137488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghizadeh, A.; Tchadjie, L.; Ekolu, S.; Welman-Purchase, M. Circular production of recycled binder from fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 415, 135098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Q.; Hu, W.; Huang, B.; Shu, X.; He, Q. Synergistic utilization of red mud for flue-gas desulfurization fly ash-based geopolymer preparation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 369, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Ma, S.; Li, S.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, Q. Low carbon research in precast concrete based on the synergistic mechanism of red mud-ground granulated blast furnace slag powder. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 439, 140882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Dilbas, H.; Çoşgun, T.; Bendjilali, F. Red-mud additive geopolymer composites with eco-friendly aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 425, 135915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Bai, F.; Nie, Q.; Jia, X. A high-strength red mud–fly ash geopolymer and the implications of curing temperature. Powder Technol. 2023, 416, 118242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Hu, X.; Shi, C. Mechanical properties and microstructure of circulating fluidized bed fly ash and red mud-based geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 340, 127599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Q.; Hu, W.; Ai, T.; Huang, B.; Shu, X.; He, Q. Strength properties of geopolymers derived from original and desulfurized red mud cured at ambient temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 125, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Nie, Q.; Huang, B.; Shu, X. Investigation of the strength development of cast-in-place geopolymer piles with heating systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; He, M.; Pan, Z. Inhibition of efflorescence for fly ash-slag-steel slag based geopolymer: Pore network optimization and free alkali stabilization. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 48538–48550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gao, M.; Lei, Z.; Tong, L.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Jiang, X. Ternary cementless composite based on red mud, ultra-fine fly ash, and GGBS: Synergistic utilization and geopolymerization mechanism. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Doh, J.-H.; Ong, D.E.L.; Dinh, H.L.; Podolsky, Z.; Zi, G. Investigation on red mud fly ash-based geopolymer: Quantification of reactive aluminosilicate derivation of effective Si/Al molar ratio. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 71, 106559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadnia, R.; Zhang, L. Experimental study of geopolymer synthesized with class F fly ash low-calcium slag. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2017, 29, 04017195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blotevogel, S.; Doussang, L.; Poirier, M.; André, L.; Canizarès, A.; Simon, P.; Montouillout, V.; Kaknics, J.; Patapy, C.; Cyr, M. The influence of Al2O3, CaO, MgO and TiO2 content on the early-age reactivity of GGBS in blended cements, alkali-activated materials and supersulfated cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 178, 107439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J. Study on the hardening mechanism of Bayer red mud-based geopolymer engineered cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 392, 131669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Xue, C.; Jia, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, Y. Preparation and curing method of red mud-calcium carbide slag synergistically activated fly ash-ground granulated blast furnace slag based eco-friendly geopolymer. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 139, 104999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Pan, H.; Zhao, Q.; Shi, Y. Properties of alkali-activated red mud-fly ash-carbide slag composites. J. Build. Mater. 2023, 26, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.; Guo, Y.; Xue, S.; Hartley, W.; Wu, C.; Ye, Y.; Cheng, Q. Natural evolution of alkaline characteristics in bauxite residue. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Bai, Y.; Zhao, Q. Mechanical performance and microstructure improvement of soda residue–carbide slag–ground granulated blast furnace slag binder by optimizing its preparation process and curing method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 302, 124403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C666/C666M-15; Standard Test Method for Resistance of Concrete to Rapid Freezing and Thawing. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Mahmoodi, O.; Siad, H.; Lachemi, M.; Dadsetan, S.; Sahmaran, M. Development and characterization of binary recycled ceramic tile and brick wastes-based geopolymers at ambient and high temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 301, 124138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, B.; San Nicolas, R.; Sani, M.-A.; Rees, G.J.; Hanna, J.V.; van Deventer, J.S.J.; Provis, J.L. Phase evolution of C-(N)-A-S-H/N-A-S-H gel blends investigated via alkali-activation of synthetic calcium aluminosilicate precursors. Cem. Concr. Res. 2016, 89, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, A.; Trujillano, R.; Gil, A.; Rives, V.; Vicente, M.Á. Hydrocalumite and hydrocalumite-type compounds: A special type of layered double hydroxides. Appl. Clay Sci. 2025, 267, 107707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia-Ballesteros, J.E.; Rodier, L.; Filomeno, R.; Savastano, H., Jr.; Fiorelli, J.; Rojas, M.F. Effect of activated coal waste and treated Pinus fibers on the physico-mechanical properties and durability of fibercement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 392, 132038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1308-08; Standard Test Method for Accelerated Leach Test for Diffusive Releases from Solidified Waste and a Computer Program to Model Diffusive, Fractional Leaching from Cylindrical Waste Forms. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).