Abstract

The design of fallout shelters is located at the intersection of many disciplines, so this is a multifaceted challenge with a high level of engineering complexity. Nonetheless, it should be considered as part of sustainable development in a broader sense—as an investment in the resilience of the urban infrastructure, the safety of the population and the continuity of the city functioning in crisis situations. One can identify the research gap indicating a lack of contemporary model solutions for shelters and this article aims to fill this gap. A comparative analytical method with an interdisciplinary approach based on a comparison of 10 existing shelter infrastructure solutions in different parts of the world was proposed. Supporting research aspects were formulated and synthetically represented in table: (A) functional integration into the city; (B) minimisation of impact on the urban fabric; (C) self-sufficiency and renewability of resources; (D) inclusiveness vs. exclusiveness. The analysis show that the existing model of the shelter as a segregated exclusive military facility does not fit the contemporary world. The result is a set of practical design recommendations based on case studies that could provide a starting point for the development of the New Fallout Shelter Standard (NFSS) for urban shelters as a sustainable civil resilience infrastructure in the 21st century.

1. Introduction

The design of fallout shelters is located at the intersection of many disciplines: architecture, urban planning, civil defence, urban policy, land use, geology and even sociology, perceptual psychology, and interior design. This is a multifaceted challenge with a high level of complexity, which, in the conditions of the modern city, cannot be treated solely as an engineering or military issue, but, on the contrary, should reach out to issues as non-obvious in this case as biophilia, salutogenesis, resilience and, ultimately, sustainable development. And while the idea of sustainability itself is primarily associated with environmentally friendly, energy-saving and other welfare-enhancing measures, its use in the context of civil defence shelters requires a redefinition of the model of the nuclear shelter that is present in the minds of the design community and administrative bodies.

The term ‘civilian shelter’ covers a wide variety of facilities, among which those described as fallout (anti-nuclear) shelters deserve special attention. The authors acknowledge that each country maintains its own legal and technical classification distinguishing between a shelter, a hiding place, and a temporary refuge. Therefore, for the purpose of this paper, all of the above terms are used interchangeably, with attention to context, to ensure both terminological clarity and compatibility with international discourse. In this article, the terms “fallout shelter” and “anti-nuclear shelter” are used interchangeably, as both refer to the protective function of such facilities. The term “civil defence shelter” is employed in reference to the user group, i.e., civilians, while the word “bunker” appears in selected passages due to its widespread presence in the existing literature and its cultural recognition. They are characterised by four essential features: they are located underground, hermetically sealed, designed to withstand shocks and geological shifts and, above all, provide conditions for the long-term stay of people in them. These are, of course, only general principles derived from the concept of air raid shelters, which are defined differently from country to country, where specialists develop their own categorisations of facilities. The design of fallout (nuclear) shelters is based on considerations remote from ‘ordinary’ architectural practice, such as, for example, the blast of an overpressure shock wave, the vacuum phase (suction phase), thermal and penetrating radiation, electromagnetic pulse and radioactive contamination. It is equally important to take the aspect of self-sufficiency into account by equipping these structures with the appropriate technical infrastructure and storage facilities with supplies, which determines the staying of people in an enclosed interior for an extended period of time. Thus, while the existing guidelines (few and very general) refer primarily to construction technology and spatial-functional relationships, i.e., to what is hidden many metres below the surface of the ground and, therefore, invisible, there are virtually no comprehensive instructions describing the design of fallout shelters in relation to the living urban fabric. What are the reasons for this? To put this into perspective, it is necessary to look at the history of the issue.

In Europe, the origins of shelters can be traced back to the First World War, when the first air raids of cities took place. However, these were sporadic cases, and the real impetus for the development of this typology on a massive scale came in the second half of the 1930s, with the spectre of approaching global armed conflict. On the basis of these trends, the Germans were the first to start building them, and the idea was followed by other countries recognising the real threat posed by air attacks that could terrorise entire cities. The experience of the Second World War was the starting point for the development of fallout shelters, which took their final form in the Cold War era. At that time, however, the topic of sustainability received virtually no attention in the discourse and had not yet penetrated into the design areas. And while it is widely acknowledged that the idea of sustainable development emerged in the 1960s, the concept itself did not gain popularity until 1987, when the UN World Commission on Environment and Development published a report that, for the first time, drew systemic attention to the need to link economic goals to economic and social objectives [1]. As history shows, this was also the dawn of a new world order backing away from the dangers of military conflict between the East and the West. This resulted in the slow degradation of the resources available at that time, which accelerated as the democratic transition in the former Warsaw Pact countries progressed.

Given the time distance separating modern times from the first completed shelters, and the fact that these were objects of strategic military importance, and were often military secrets, we cannot say much about their designers today. However, upon completion of the query of the sources, which reveals the austere nature of the interiors, the lack of humanising aspects, or the ‘hyper-functionality’ of the studied typology of facilities, it can be assumed with a high degree of probability that the presence of motifs associated with sustainable development was reduced to a minimum, if it was present at all. Unfortunately, by virtue of their purpose and technical requirements, shelters are extremely material-intensive, costly, and difficult to maintain. Their construction involves a great deal of interference with the natural and urban environment—both in the construction and operational phase. Nonetheless, they should be considered as part of sustainable development in a broader, systemic sense—as an investment in the resilience of the urban infrastructure, the safety of the population and the continuity of functioning of the city in crisis situations. This is in line with the principle of a profoundly holistic approach to sustainability, which is no longer based only on minimising environmental costs here and now, but, above all, ensuring the survival of social and spatial structures in the long and wider term of the entire generation.

Despite the relevance of the issue of sustainable development, virtually no country has associated it with civil defence issues. It was not until Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 that policymakers turned their attention to the above issue; it showed that the best-equipped shelters are in European countries outside NATO structures, which take care of their own security without the benefit of the protection umbrella provided by the US. This small group included Sweden (65,000 shelters for 7 million people, or 66% of the population [2]), Finland (50,000 shelters for 4.8 million people, or 86% of the population [3]), or Switzerland, which provided places for 100% of the [4] population (sic!); Norway and Denmark can also be added here. These countries managed to avoid the mistakes of other countries where an illusory sense of security prevailed after the end of the Cold War. A particularly vivid example of this is provided by Germany, which, at the beginning of the 21st century, dismantled virtually all air raid shelters, leaving intact a few relics dating back to the Second World War that can accommodate only 0.5% of the population today. It was no different in the former Warsaw Pact countries, where there was room for a few percent of citizens in shelters only a few years ago. In recent months, however, real steps have been taken to restore the readiness of the shelters in question. An example of this is an act adopted by the Polish Parliament (the so-called Shelters Law valid since 1 January 2025 [5]), according to which the underground storeys of new buildings must be designed in such a way that they could be used as shelters, or an analogous Law in Lithuania (Law on Crisis Management and Civil Protection [6]). These documents oblige public institutions, local governments and investors to provide protective infrastructure and to integrate disaster management activities with land-use and building planning. However, this is a drop in the ocean of needs.

The neglect during the three decades of the post-Cold War peaceful interlude has not only led to material losses, when most shelters changed their purpose and the rest deteriorated, but has also resulted in an erosion of know-how among designers, most of whom have now ceased to practise their profession, and the professional bodies in question do not raise the issue. This lack of action, or perhaps abandonment that can be seen in the architectural and urban planning community, is incompatible with the idea espoused by the European Union, which refers to harmonious, permanent or sustainable socio-economic development leading to its inhabitants’ attainment of a higher standard of living. All these issues were already included, twenty-five years ago, as a major objective of the Lisbon Strategy [7] that undoubtedly had to take into account the resilience and security aspects of civil defence infrastructure. The idea that architecture can become the primary tool for solving social problems is reflected in the current agenda known as the ‘New European Bauhaus’ [8], which is an elaboration of the ideas of the New Leipzig Charter [9] with the telling title ‘Transformative Power of the City for the Common Good’, which is deeply rooted in the concept of the Bauhaus. The concept embodied in the NEB, on the one hand, reflects visions of beautiful, sustainable and socially inclusive places and their associated ways of living and, on the other hand, warns that architecture has too often focused on itself in recent decades, forgetting its primary purpose—to address the needs of all. This points to the need to go beyond existing models and to move towards innovative thinking, towards the harmonisation of social and environmental needs. The research on guidelines for the NFSS model undertaken in this dissertation meets the intention expressed in the NEB, which is based on three key terms: Beauty—understood as a quality of experience that goes beyond pure functionality; Sustainability—the pursuit of climate goals and the preservation of biodiversity; and Community—inclusivity and social accessibility. Taken together, these issues would lead to the creation of resilient urban ecosystems, where civil defence shelters should become an important element in today’s context.

The idea and thoughts quoted in the paragraph above are for an ideal world. In fact, despite their clear presence in the collective imagination of the Europeans, whether through literary works or cinematic manifestations of a culture that might seem socially and culturally attractive, fallout shelters remain absent from both architectural and planning theory and practice. There is also little academic interest in the subject; with a few exceptions, there are no academic conferences devoted to the architectural or urban aspects of designing any shelters, let alone such ‘nuances’ as the context of sustainability. Therefore, it becomes necessary to undertake reliable research in this field—a sort of design and research niche into which this article fits.

2. Materials and Methods

In view of the increasing risk of military conflict on the European continent, it becomes necessary to revise the approach to the design of fallout shelters, particularly in the context of highly urbanised environments. This is particularly the case in the former communist Eastern bloc countries, which do not have an extensive and efficient shelter infrastructure similar to the Scandinavian model. In contrast, the one that exists is characterised by poor technical condition and lack of integration into the modern and vibrant urban fabric. This state of affairs generates a research gap indicating a lack of contemporary model solutions for Central European shelters. This is followed by the thesis of this paper, which states that the contemporary situation requires the creation of a new systemic approach to the design of fallout shelters integrated into the city centre fabric and able to function as part of sustainable urban development. This thesis meets the current empirical observation that the design community has still not developed standards for responding to military threats in an urban structure. This applies both to spatial solutions themselves and to procedures for implementation, location and integration with urban infrastructure. The aim of this thesis is, therefore, to develop a set of practical design recommendations based on case studies that could provide a starting point for the development of the New Fallout Shelter Standard (NFSS) for urban shelters as a sustainable civil resilience infrastructure in the 21st century.

An analytical research method based on a comparison of existing shelter infrastructure solutions in different parts of the world was proposed for the thesis outlined above. To outline the framework for the above analysis, four supporting research questions relating to the urbanised environment were formulated. (1) How to effectively integrate the city with the new shelter? (2) How to take care of the city’s civil resilience without damaging its fabric? (3) Should we include issues of self-sufficiency and resource renewability in the shelter discourse? (4) Should we build for all or for the chosen few?

An attempt to answer these questions was made through an interdisciplinary approach involving the analysis of four main aspects that define sustainable development in the context of the shelter-city relationship. The aspects are as follows: (A) functional integration into the city; (B) minimisation of impact on the urban fabric; (C) self-sufficiency and renewability of resources; (D) inclusiveness vs. exclusiveness. Each of these aspects directly derives from the four research questions posed above: aspect (A) corresponds to question (1), (B) to (2), (C) to (3), and (D) to (4). Their inclusion in the analytical process and thus understanding them leads to the elaboration of the NFSS—a set of design guidelines for sustainable conservation solutions in the urbanised environment, which results in filling the research gap identified.

The proposed set of analytical principles [A–D] is entirely original and developed by the authors; there is no equivalent framework found in the existing literature. Its theoretical foundation was informed by contemporary policy and strategic documents, including governmental and NATO guidelines, expert analyses, and consultations with representatives of the Lviv Polytechnic National University in Ukraine, presented as the state of the art. Moreover, the framework draws on the theoretical understanding of sustainability, particularly its key pillars—environmental, social, economic, and institutional—which together define a holistic approach to sustainable development in architecture and urban planning. By combining these sources, the model integrates current civil protection strategies with the broader agenda of sustainable and resilient urban design.

3. State of the Art

The research was based on a detailed and extensive search of specialist literature, and includes architectural, military, sociological, and last but not least, government and local authority sources, without which it would have been impossible to establish guidelines for the NFSS. As already mentioned, the research area is located at the intersection of several disciplines, whose literature is quite diverse and most often thematically distant. At the outset, it is important to make a basic time caesura that determines any further research. According to this caesura, we can distinguish two main groups: literature created during or relating to the Cold War period and literature describing the situation after the fall of the Iron Curtain. The state of research is structured according to this division.

3.1. The Cold War Situation

In the context of Cold War shelters, there are many studies, government and military reports, popular science books and papers, mainly of American origin. It can be successfully assumed that analogous studies were also produced in the Warsaw Pact, above all in the USSR, but access to them is difficult due to state secrets and the historical ‘turmoil’ of the time. Consequently, the most important studies from the perspective of this paper are handbooks published in the US, including, among others, the 1961 Fallout Shelter Program [10] published by the US Department of Defense, which informed citizens about the dangers of a thermonuclear attack and how to protect themselves against it. It included information on the general dangers resulting from the use of nuclear weapons, radiation and radioactive fallout, as well as guidance on shelter construction, the provision of necessary supplies and the rules of conduct during a stay in a shelter. In addition, it described survival issues such as food and water preservation, first aid and site cleaning procedure after radioactive fallout. Another interesting study is a report on shelters located under large-scale facilities such as shopping malls and factories [11]. The publication issued by the US Office of Civil Defense in December 1967 contained recommendations on location, construction and building materials to improve the effectiveness of shelters in this type of facility. Despite the important content covered in the above handbooks, none of them locates the content in an urban context, particularly dense metropolitan areas.

Analogous deficits are present in numerous popular science studies on Cold War shelters. Most of them are contemporary US and UK publications such as Fallout Shelter: Designing for Civil Defense in the Cold War by David Monteneye [12], which examines the collaboration between architects and civil defence authorities in the USA in the context of the design of Cold War shelters. The author shows how this collaboration influenced design practices and perceptions of urban and suburban spaces, leading to the formation of ‘bunker architecture’ that reflected the social anxieties of the time, but also class divisions, which ultimately led to the ultimate failure of many shelter initiatives undertaken at that time. Another book that introduced designers to the topic of shelters is Safe Rooms and Shelters [13] published by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). It is a richly illustrated handbook for engineers, architects, building officials and property owners, offering guidance on the design of shelters and safe rooms in residential, commercial and public buildings. There are also a number of analogous items published today that relate to that era, such as Underground Structures of the Cold War [14] and Cold War Secret Nuclear Bunkers: The Passive Defence of the Western World During the Cold War [15], which discusses examples and interesting facts about the subject of shelters.

Among many publications with a popularising function, it is worth devoting even more attention to few research papers in which architectural or urban planning topics appear. One could mention, for example, Was There a Real ‘Mineshaft Gap’? Bomb Shelters in the USSR, 1945–1962 by Edward Geist, where the development and significance of the Soviet fallout shelter programme is analysed in the context of the existence of the ‘shelter gap’ in cities. The author shows that the Soviet shelter programme was fraught with logistical problems, financial shortfalls and bureaucratic hurdles, and should be seen more as a propaganda tool than a viable mechanism for protecting the population, which undermined its effectiveness in the event of nuclear war [16]. In contrast, the topic in the Scandinavian context is addressed by Adam Andersson [17]. His research sheds light on Sweden’s defence preparations in the 1960s. While the text shows how shelters were integrated into housing infrastructure, the emphasis is put here on seeing shelters as material historical testimony and the text should be read in this perspective. It is particularly worth looking at the text Becoming Atomic: The Bunker, Modernity and the City, where authors Boyd and Linehan point to the role of shelters as an integral part of urban visions of Cold War cities. According to them, shelters not only fulfilled a protective function, but also became an important social and cultural element shaping ideas of security and annihilation [18]. Polish examples can still be cited here, taking up the theme of the systemic integration of primary schools with shelter and hospital functions, which took place in the 1960s–1970s [19].

3.2. The Contemporary Situation

In this respect, three types of studies can be distinguished. The first are reports and documents produced by government agencies or other organisations related to defence issues, none of which is scientific in nature, but provides a comprehensive and detailed description of the current situation prevailing in a given EU ‘frontline’ country. The general rule of thumb observed during the material query indicates that only states directly threatened by military activities generate contents about shelters. Among the more extensive studies, it is necessary to refer to the Supreme Audit Office’s 2024 Report in Poland [20] and the Norwegian Government’s White Paper, Total Preparedness: Prepared for crises and war published in January 2025 [21]. Legal acts, such as the ‘Shelter Act’ in Poland [5], which regulates such issues as the planning and use of collective protection facilities, as well as their financing, deserve separate attention in this group. It should also be noted that the basis for all of these documents is the Geneva Convention for the Protection of Victims of War of 1949.

The second group are publications created on the fly and often on an ad hoc basis, which does not diminish their popularising value. They are not scientific either, but, being firmly rooted in the present situation, they address the issue in the context of current crisis situations. Among these, we can distinguish those that compare the situation in Ukraine with the Baltic States in the context of shelters and evacuations, highlighting the role of the voluntary sector in civil defence, or those analysing the situation in Northern and Central Europe [22]. Within this group, we can also distinguish studies that take a closer look at the state and location of shelter infrastructure in individual historical metropolises, such as Vilnius [23], Vienna [24], Bucharest [25] and many other European cities. A distinguishing feature of all the above studies is that they are not written in the accepted scientific language of English, but are by definition available in national languages (Lithuanian, Latvian, Polish, Romanian, Norwegian, etc.), which obviously makes them difficult to access for scientific bodies from other countries.

Finally, the third group is made up of a small number of English-language scientific publications, among which it is possible to distinguish barely single items that deal with architectural-planning topics, their functioning within defence systems, as well as their socio-cultural significance. An example of such comprehensive research is the Finnish approach to the planning of underground spaces, analysed by Ilkka Vähäaho [26,27,28], which provide a model solution for modern agglomerations. According to Vähäaho’s publications, Helsinki has become a leader in the integration of civil defence shelters into the city infrastructure, having a network of underground spaces that serve functions such as car parks, swimming pools, sports halls and, if necessary, shelters. What emerges from this reading, is the state of knowledge indicating the growing need for the integration of shelters into cities and their infrastructure, served primarily by a model of designing shelters as dual function facilities—acting as ‘living’ public spaces on a day-to-day basis and transforming into shelters in crisis situations. Vähäaho emphasises that the key to the success of the Finnish system is precisely this flexibility and versatility of the underground space network, which indirectly supports the sustainability of the city. In order for such a vision to succeed, appropriate planning regulations and recognition of the social context are needed on the one hand, and adequate technical expertise on the other hand. Undeniably, the technical aspects of shelter construction are an extremely important part of the research on their functionality and effectiveness, as discussed in detail by Barilla and Szota in their paper, Material and Construction Solutions in the Construction of Civil Defence Shelters [29,30]. Szczęsniak and Doll, on the other hand, explore the possibility of using various urban facilities as temporary shelters on an ad hoc basis, which can provide a quick supplement to infrastructure in emergency situations [31]. Deville Guggenheim and Hrdličková take a different, humanistic approach, emphasising that shelters are not only engineering structures, but can be a tool of state policy for fear management [32]. They propose the concept of concrete governmentality, according to which protective infrastructure fits into a broad crisis management strategy, influencing the psychology of society. The aspect of the psychological and even cultural significance of the shelter is detailed by Richard Ross in his book Waiting for the End of the World [33]. Because the author spent a few years documenting the lives of people preparing for a nuclear apocalypse, the research is set in a very specific preppers’ environment. The author does not go into technical details such as materials or engineering aspects of shelter construction, but his goal is to capture the psychology of the people who decide to build this type of facility and to show how the overall process reflects their fears and worldview. According to the view presented there, shelters become more than just physical spaces—they become symbols of protection and survival as well as expressions of fears about the future. This apocalyptic overtone is identifiable also in Garett Bradley’s monograph Bunker: Building for the End Times [34]. It describes how the concept of shelters has evolved—from Cold War defence structures for governments and elites to contemporary luxury shelters for the rich and mass public shelters in Scandinavian countries or Russia. On the wave of contemporary fears, the topic of the commercialisation of shelters is presented in two publications: DIY Bomb Shelter: How to Build an Underground Shelter in Your Home and Protect Your Family [35] by John Becker and The Ultimate Guide to Underground Bunker Living [36] by J. L. North. Both are practical guides for people who want to build their own underground shelter to ensure safety in the event of an emergency. The authors discuss all aspects of the process, from planning to execution, focusing on ensuring maximum protection for the family. These studies provide detailed instructions and guidance in an accessible way about every stage of shelter construction, from planning to provision of supplies.

The main conclusion from the above query is that, despite the numerous historical sites, the large-scale construction of shelters continues, from specialised underground military complexes to private ‘panic rooms’ in the houses of the elite. Unfortunately, cities, with few exceptions, do not have their own development strategies that would systemically incorporate thinking about shelters as a public good that is appropriate for modern times. It is no secret that it was the war between Russia and Ukraine that gave new impetus to the discussion about civilian shelters. Among the multitude of studies is The Russia-Ukraine War [37], in which the author, Fedorchak, discusses the role of shelters in Ukraine’s adaptation to the ongoing conflict, covering the renovation of Soviet-era shelters and the adaptation of basements and garages to this function. However, the book does not provide detailed information on the spatial layouts of civil defence shelters or the specific details of their construction. Instead, it focuses on more general aspects related to war, such as military operations, combat tactics, soldiers’ morale and the effectiveness of civil defence in the context of the current conflict. Research by Shpiliarevych, Kosmider and Jagusiak [38] has shown that in a situation of real danger the civil protection system requires dynamic modification, modernisation and support from state and international structures. Juurvee [39] points out that the key challenge is to modernise shelters in the context of new threats such as missile attacks or the use of drones. The social and cultural dimension of shelters, which, in addition to their protective function, can play important integrative and symbolic roles, should not be overlooked, either. Howlett et al. [40] demonstrated that shelters in Ukraine have become not only places of protection from military threats, but also spaces for community building, organisation of social life and resistance to the aggressor. The text New Ideas for Total Defence: Comprehensive Security in Finland and Estonia by Piotr Szymański [41], which presents the concept of ‘total defence’ in the Nordic and Baltic countries, is set in an analogous context. This approach encompasses not only traditional military defence measures, but also extensive co-operation between the civilian and military sectors during crises such as war or other dangers. Anna Wierzbicka [42] and her team, in their paper The Conceptualisation of a Modular Residential Settlement, seek to identify practices that meet the criteria of sustainability and promote the health of residents, including mental health in the context of the reconstruction of post-war Ukraine. They conclude that this is facilitated by the creation of spaces that evoke a sense of security and support social relationships in a world increasingly vulnerable to crises. They propose adding the ‘safety’ axis to the set of NEB thematic axes. They point out that the function of ‘panic rooms’ can be fulfilled by suitably reinforced washrooms, equipped with an individual and customised escape route. The authors emphasise that modularity provides benefits that cover the speed of construction, cost effectiveness and durability. They mention that this method increases productivity by up to 40% and that the pro-environmental benefits include reduced emissions, waste control, optimised processes (quality, external conditions, delivery and scheduling) and better storage of construction materials. The same topic is taken up by Pawel Trębacz [43], who describes an attempt to implement the ideas of the New European Bauhaus on the example of the ProModSe modular housing project in Lviv for the population of refugees from war zones. As a result of the survey, he concludes that the development complex under consideration fits into the slogans defining the four NEB thematic axes: ‘a return to nature’; ‘reclaiming a sense of community and belonging’; ‘prioritising places and people who need it most’; and ‘the need for a long-term life-cycle and integrated approach in the industrial ecosystem’ in all three scales: the whole housing estate, the urban block and the individual residential segment.

There is a growing number of scientific studies addressing the topic of shelters and protective architecture, combining technical, urban, and social perspectives. The three publications most closely related to the authors’ approach in this paper were all published after 2020. The first, Design of Shelters for Civilians in the Event of Armed Conflict: State of the Art and Contemporary Design Guidelines [44], analyses the current state of protective infrastructure in Poland and Europe, proposing contemporary design guidelines for civilian shelters within urban and legal contexts. The second, Innovative Construction Techniques in Bomb Shelters as Architectural Response to Nuclear Threat [45], focuses on innovative technologies and materials in shelter design, emphasising sustainability, self-sufficiency, and psychological comfort for users. The third, Integrating Sustainable and Energy-Resilient Strategies into Emergency Shelter Design [46], discusses the incorporation of sustainability principles and energy efficiency strategies into protective facility design, directly relating to the NFSS concept and its environmental, economic, and social pillars. These studies highlight the increasing academic interest in the topic of shelters and confirm the relevance of developing an integrated approach to protective architecture within European cities.

In addition, apart from scientific studies, we can point out at most single scientific conferences devoted to the topics addressed in the paper, such as the International Scientific and Technical Conference EKOMILITARIS 2012 [47], during which the principles of maintenance and financing of shelter structures were proposed [48], or the Conference on Planning and Development of Underground Space, indirectly addressing the issue of air raid shelters in Helsinki [49], or the Schrontech Workshop on Shelter Technology organised in 2024 by the Institute of Protective Construction in co-operation with the Military Academy of Technology and the International Association of Protective Structures [50]. However, given the small number of conference presentations addressing the topic, the analysis of Helsinki resources linked to the Underground Master Plan [49] should be regarded as particularly valuable. After the survey of the literature, we are inclined to agree with the opinion that the issue is not underestimated by professional bodies and researchers. In the field of contemporary theory and architectural and urban design, particularly in the context of today’s important issue of sustainable urban development, the subject matter of this analysis is terra incognita.

In order to better understand this “terra incognita”, it is necessary to refer to the theoretical foundations of sustainable development—a concept that defines the contemporary framework for responsible spatial and architectural design, including protective and defensive structures. Sustainable development is understood as a commitment to meeting the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs [51].

In the literature, three main pillars of sustainability are commonly identified:

- The environmental pillar refers to the protection of natural resources, the reduction in negative environmental impacts, lower energy consumption, and the promotion of renewable technologies [52,53].

- The social pillar encompasses justice, inclusivity, equal access, social well-being, participation, and the overall quality of life [54].

- The economic pillar focuses on cost efficiency, financial durability, economic growth, the optimal use of resources, and the full life cycle of an investment [55].

Some interpretations expand this classic triad by adding an institutional or human dimension, emphasising the role of organisational structures, institutions, and governance processes in achieving sustainability.

In the context of protective structures, the principle of sustainability should ensure that defensive and everyday functions can coexist without prioritising one over the other, making such facilities both effective in emergencies and useful in daily life. The environmental dimension highlights the need to reduce material consumption, apply energy-efficient and renewable solutions such as photovoltaic systems or heat pumps, and promote material recycling and responsible water management. The social dimension stresses the importance of accessibility for diverse user groups, including people with disabilities, as well as integration with the urban fabric and the assurance of user comfort and psychological safety. The economic dimension underlines the necessity for financial balance—ensuring that the construction and maintenance of shelters remain affordable, cost-efficient, and sustainable throughout their life cycle. Finally, the institutional and managerial dimension concerns the allocation of responsibilities for facility management, the legal and regulatory frameworks in force, and the coordination between safety services, public administration, and users.

In summary, the review of the available literature and sources highlights that research on protective architecture, though extensive in historical, technical, and sociological terms, remains fragmented and rarely connected to the contemporary discourse on sustainable urban development. This observation directly informs the rationale for selecting the case studies discussed in the following section. The identified gaps—particularly the lack of integrative, cross-disciplinary approaches combining architectural, social, and environmental dimensions—guided the choice of examples that best illustrate emerging directions in the design and adaptation of protective structures. Consequently, the case study analysis aims to verify how the principles derived from the literature, especially those related to resilience, inclusivity, and sustainability, can be translated into practical architectural and urban solutions, ultimately contributing to the formulation of the proposed New Fallout Shelter Standard (NFSS).

4. Research—Analysis of Existing Shelters

In the search for the New Fallout Shelter Standard (NFSS), the decision was made to analyse existing shelters, obviously within the scope of the data that could be obtained. These facilities, often built in different geopolitical and technological contexts, present diverse typological approaches, different (civilian, military, government) functions and a degree of integration into the urban fabric.

A total of ten facilities were selected for analysis, divided into two main categories: Cold War–era shelters and contemporary shelters. Before 1989 the most extensive investments in protective infrastructure were undertaken in the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective satellite states. In contrast, in the present day, the largest and most innovative projects are concentrated in neutral countries and those directly affected by ongoing military conflicts. Well-documented American examples from the Cold War period were included because they offer a clear methodological and architectural reference point for understanding large-scale civil defence strategies of that time. The Israeli cases, on the other hand, represent a unique and continuously tested system, as the country remains in a state of permanent security tension. Civil defence is embedded in everyday urban and architectural practice, and the population as a whole participates actively in maintaining readiness and personal safety. It should also be acknowledged that noteworthy solutions can be found in other regions, such as Taiwan or the Korean Peninsula; however, the Israeli examples were prioritised because they are subject to constant verification through real military conditions, providing a valuable empirical basis for assessing the effectiveness and adaptability of protective infrastructure. Overall, the selected cases were chosen not only for their geographic diversity but also for the quality and accessibility of available documentation, which allowed for a reliable and comparative analysis relevant to the development of the New Fallout Shelter Standard (NFSS) in the European context.

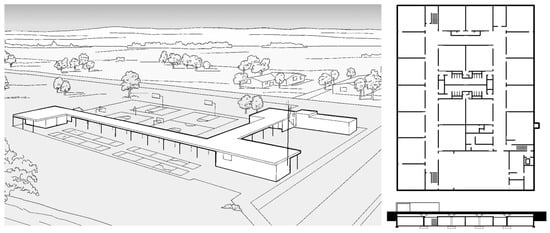

4.1. Abo Elementary School in Artesia, USA [56] (Figure 1)

- Location: Artesia, NM, USA;

- Intended use: Primary school that if necessary can serve as a bomb shelter;

- Construction period: 1961–1962;

- Capacity: 540 pupils and no more than 200 additional persons in the event of an evacuation.

The Abo School was the first primary school in the USA built entirely underground to serve a dual purpose as a full-fledged fallout shelter. It was designed not only as an educational facility, but also as a place in which people from the local community could take shelter in the event of a nuclear attack. The building, with a total area of 2100 m2, consisted of concrete rooms sheltered by a 15-inch reinforced concrete ceiling and earth, and had three entrances with heavy explosion-proof doors. Inside there were standard classrooms, but also elements typical of a shelter: food storage for a fortnight, deep wells, an air filtration system, power generators, a decontamination system; it also has a chapel and a mortuary. The school operated until 1995, and today the building is a testament to the Cold War era and is sometimes used in educational programmes.

Figure 1.

Abo Elementary School in Artesia, USA. Axonometry and plan. Source: compiled by the authors.

Figure 1.

Abo Elementary School in Artesia, USA. Axonometry and plan. Source: compiled by the authors.

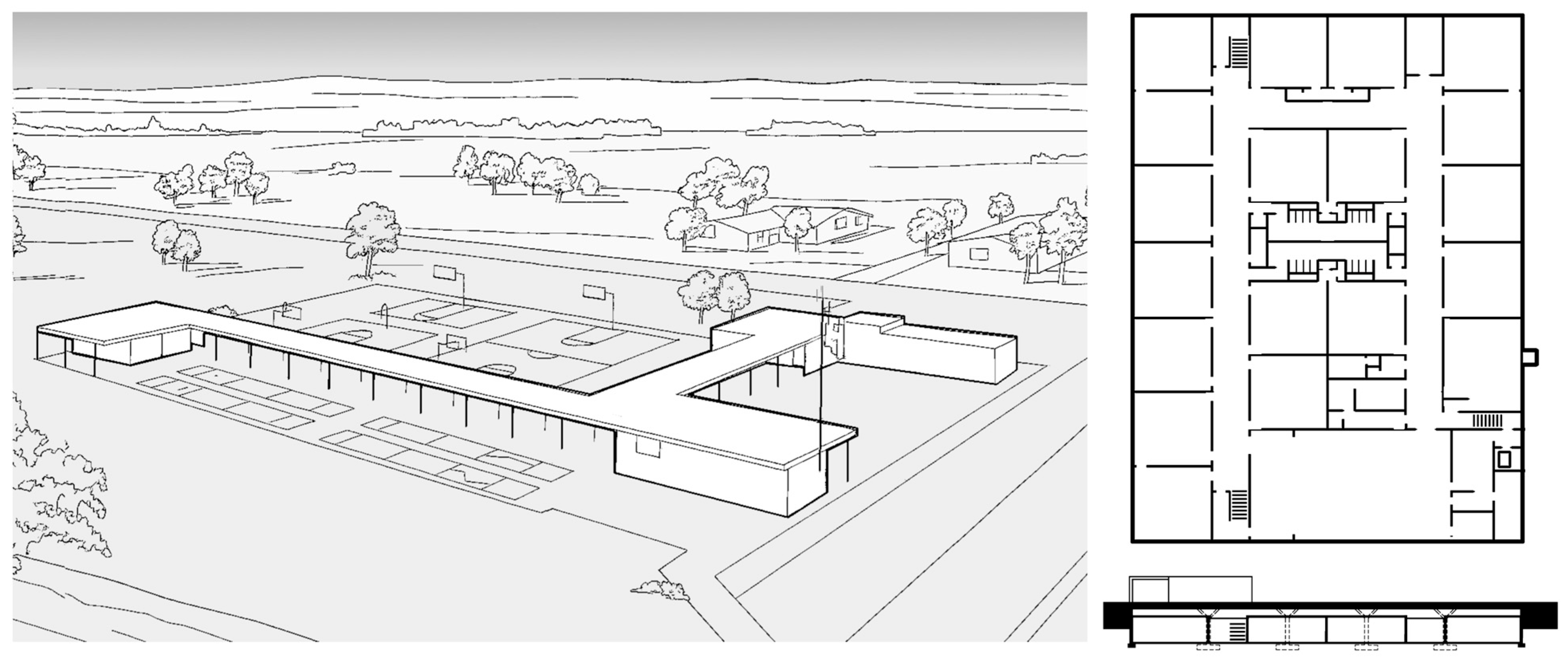

4.2. Greenbrier in White Sulphur Springs, USA [57] (Figure 2)

- Location: White Sulphur Springs, WV, USA;

- Intended use: Secret shelter for the US Congress;

- Construction period: 1958–1962;

- Capacity: More than 1000 people.

Hidden beneath the luxurious Greenbrier Hotel is one of the most advanced Cold War shelters, now no longer used for its original purpose—a secret complex known as Project Greek Island, whose main function was to ensure the continuity of the US Congress [58] in the event of a nuclear attack. The shelter is completely self-contained: it is equipped with bedrooms, meeting rooms, sanitary facilities, kitchens, medical facilities, a press centre and life support and communication systems. For three decades it remained in full readiness, masked as the hotel’s conference centre. After the function of the complex was revealed in 1992 [59], it was decommissioned and the site is now available for guided tours, serving as a tourist attraction and a symbol of the Cold War in the USA [60].

Figure 2.

Greenbrier in White Sulphur Springs, USA. Axonometry, floor plans and site plan. Source: compiled by the authors.

Figure 2.

Greenbrier in White Sulphur Springs, USA. Axonometry, floor plans and site plan. Source: compiled by the authors.

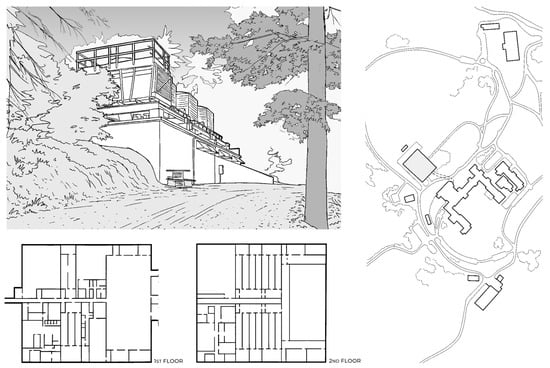

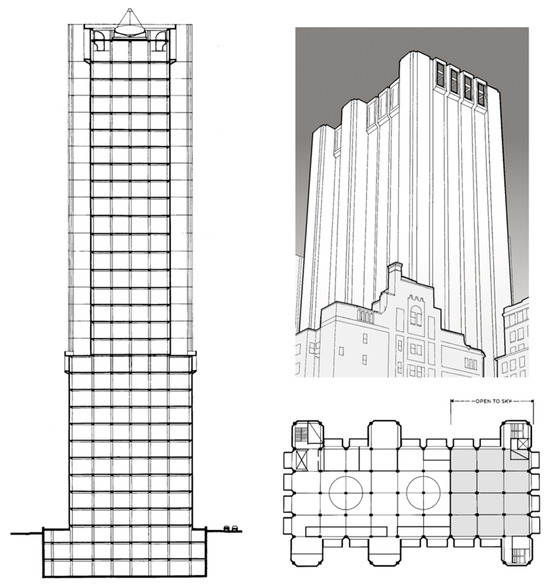

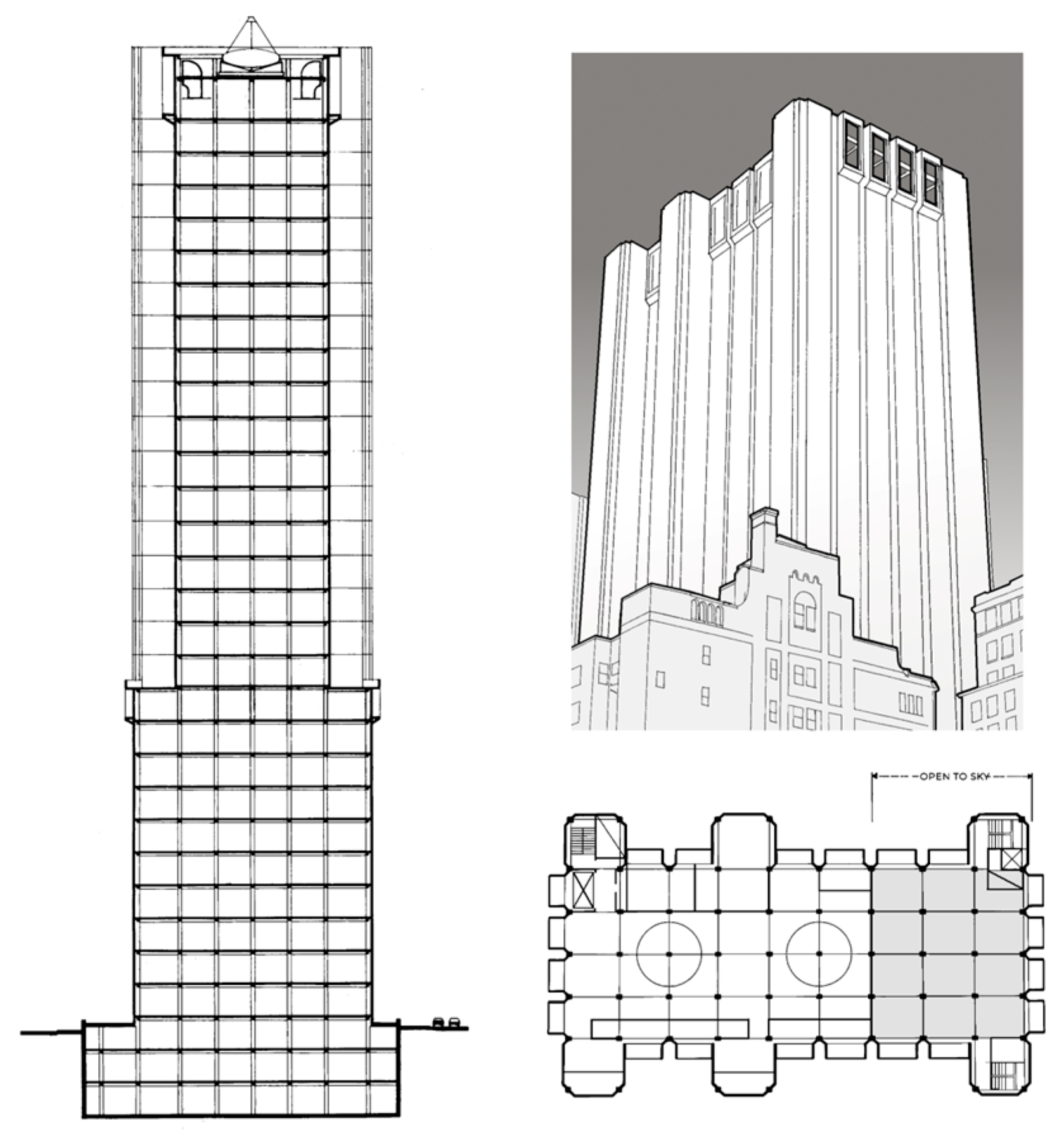

4.3. AT&T Long Lines Building in New York, USA [61,62] (Figure 3)

- Location: Lower Manhattan, New York, NY, USA;

- Intended use: Telecommunications centre resistant to nuclear attack;

- Construction period: 1974;

- Capacity: Up to 1500 persons.

The 29-storey skyscraper in Lower Manhattan, known as the AT&T (American Telephone and Telegraph Company, New York, NY, USA) Long Lines Building, was designed to be one of the city’s sturdiest buildings, resistant to nuclear attack and to any other disasters. It has no windows, and its granite façade and extremely strong steel structure were intended to withstand even a direct hit from, missiles or bombs. Its basement contains survival systems: shelters with supplies of food and water, air filtration systems and dedicated generators [63]. Although officially designed to support telecommunications infrastructure, there is speculation that it also had functions related to covert intelligence operations, e.g., as a wiretap node for the NSA’s ‘Titanpointe’ programme [64]. Today, the building still operates as a data transmission centre and is not open to the public, but it attracts the attention of Brutalist architecture enthusiasts and Cold War historians.

Figure 3.

AT&T Long Lines Building in New York, USA. Section, axonometry, floor plan. Source: compiled by the authors.

Figure 3.

AT&T Long Lines Building in New York, USA. Section, axonometry, floor plan. Source: compiled by the authors.

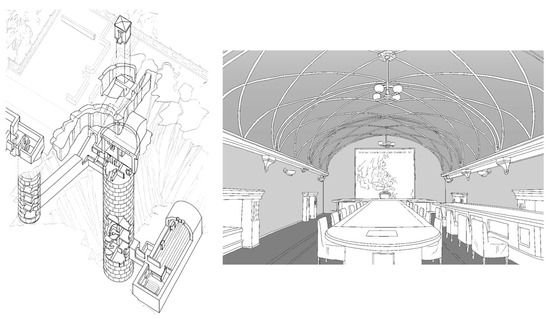

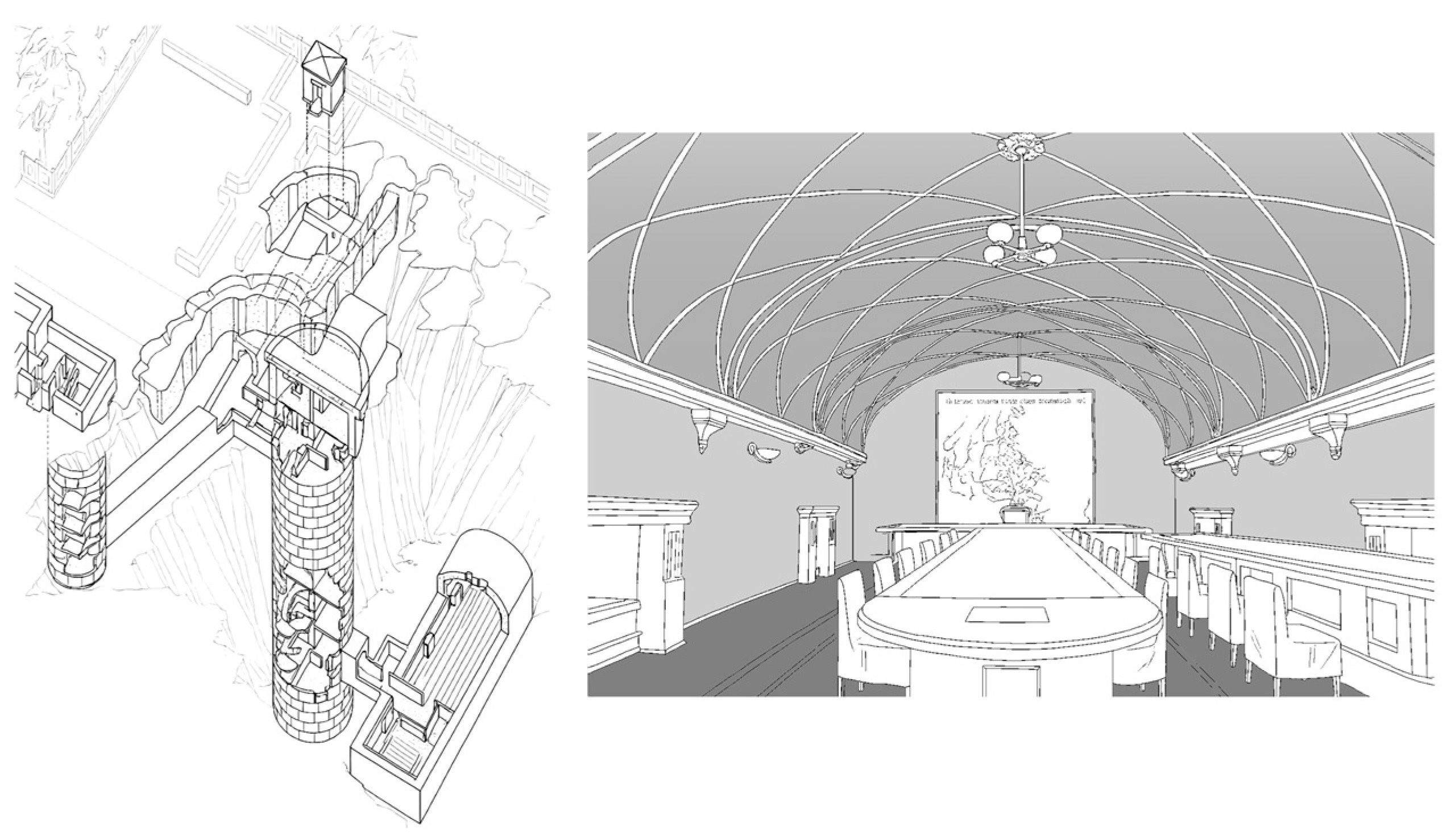

4.4. Fallout Shelter in Samara, Russia [65] (Figure 4)

- Location: Samara (formerly Kuibyshev, USSR);

- Intended use: Nuclear-bomb-proof shelter for the highest authorities of the USSR;

- Construction period: 1942;

- Capacity: Up to 600 people.

During the Second World War, faced with the threat of a German attack on Moscow, the Soviet authorities decided to build an alternative capital in Kuibyshev. As part of this effort, an anti-atomic shelter intended for the highest authorities of the USSR, including Joseph Stalin, was completed there in 1942. The shelter was built 37 m below ground level, which is equivalent to the height of a 12-storey building [66]. The facility consists of several levels, including a conference room, an office, and technical rooms. It is equipped with air filtration systems, independent power sources and food and water supplies to ensure that people can stay there in isolation for a long time. After the war, the shelter was kept secret and remained in readiness in the case of a nuclear conflict. The site now serves as a museum open to tourists who are interested in Cold War history and defence architecture [67,68].

Figure 4.

Fallout shelter in Samara, Russia. Axonometry and visualization of interior. Source: compiled by the authors.

Figure 4.

Fallout shelter in Samara, Russia. Axonometry and visualization of interior. Source: compiled by the authors.

4.5. Civilian Shelter System in Israel (Figure 5)

- Location: The entire territory of Israel;

- Intended use: Protection of civilians against missile attacks and weapons of mass destruction;

- Development period: Since 1951, intensification after 1991;

- Capacity: More than 1 million shelters of various types.

Israel has one of the most advanced civilian shelter systems in the world, which are an integral part of public spaces; they are linked not only to buildings but also to public spaces such as bus stops, playgrounds, and city squares, which perform their primary social and recreational functions on a daily basis [69]. Since 1991, the law has required every newly constructed residential building to be equipped with a ‘Merkhav Mugan’—a reinforced room protecting against explosions, shrapnel, and chemical and biological attack [70,71]. In older buildings, there are public shelters (Miklat) often adapted for the needs of local communities, such as clubs, gyms or places of worship [72]. According to current information, in northern Israel, the government plans to build some 10,000 new shelters and 1700 reinforced ‘panic-rooms’ in private houses in response to threats from Hezbollah [73].

Figure 5.

Civilian shelter system in Israel. Vizualisation. Source: compiled by the authors.

Figure 5.

Civilian shelter system in Israel. Vizualisation. Source: compiled by the authors.

4.6. Katarinabergetsskyddsrum in Stockholm, Sweden (Figure 6)

- Location: Stockholm, Sweden;

- Intended use: Dual-purpose car park and civilian shelter;

- Construction period: 1952–1957;

- Capacity: 20,000 people, including 5000 sleeping places; currently 8000 places.

The Katarinabergetsskyddsrum is the largest rock-cut civil defence shelter in Stockholm, located in the Södermalm district, with the area of 15,900 m2. At the time of its completion, it was the world’s largest civilian fallout shelter and, at the same time, Europe’s largest car park. The facility consisted of three levels with a total length of around 400 m serving as a car park for around 550 cars on a daily basis. In an emergency, the six gates, each weighing 51 tonnes, can be closed with the help of electric motors, providing shelter for around 20,000 people, 5000 of whom have access to sleeping accommodation. A single space in the shelter was calculated at 0.75 m2/person plus space for common functions, which in effect meant a large crowd and low comfort, so the facility was not intended for stays longer than a few days [74]. There were no food stores in the facility, drinking water was obtained from wells and municipal sources, and washing water from the cooling system. The facility had a ventilation and air-conditioning system based on a powerful refrigeration plant supplied from pools holding 200 tonnes of ice, accompanied by an extensive air purification plant. In addition, the facility had decontamination facilities for the removal of radioactive fallout and the cleaning of 250 toilets. Electric energy generation was provided by an in-house power plant powered by seven diesel engines. After the Cold War years, the shelter served only as a large-scale garage for a long time. It is currently under renovation to provide protection for 8000 people [75].

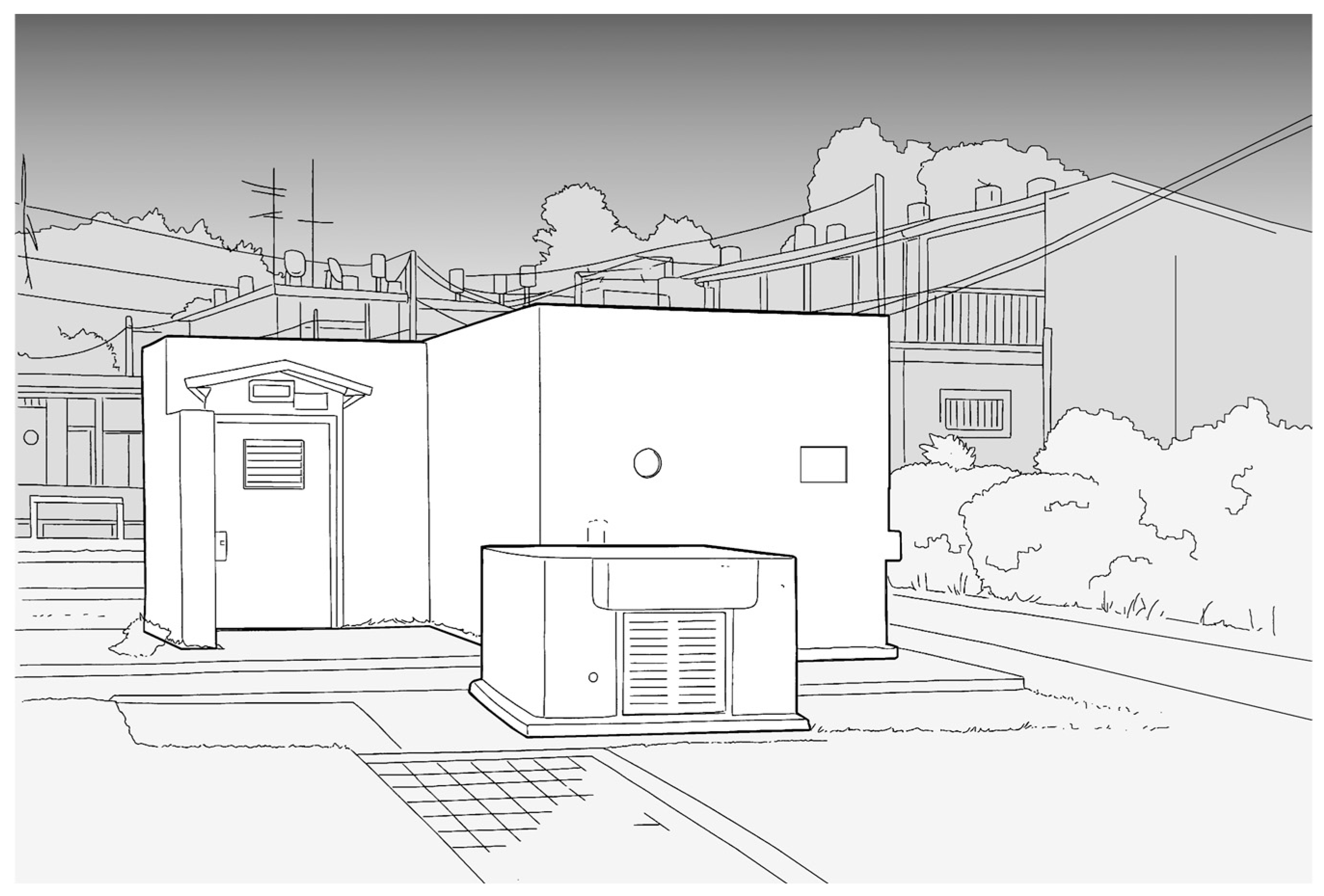

Figure 6.

Katarinabergetsskyddsrum in Stockholm, Sweden. Visualisation, axonometry, section. Source: compiled by the authors.

Figure 6.

Katarinabergetsskyddsrum in Stockholm, Sweden. Visualisation, axonometry, section. Source: compiled by the authors.

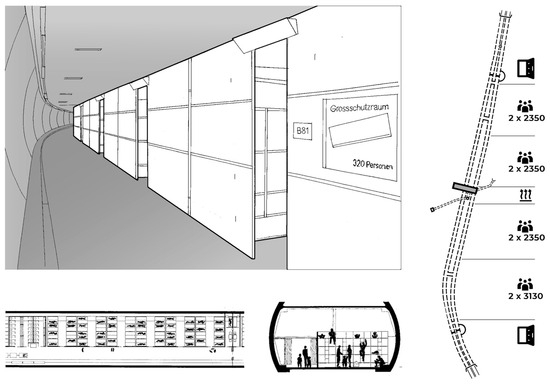

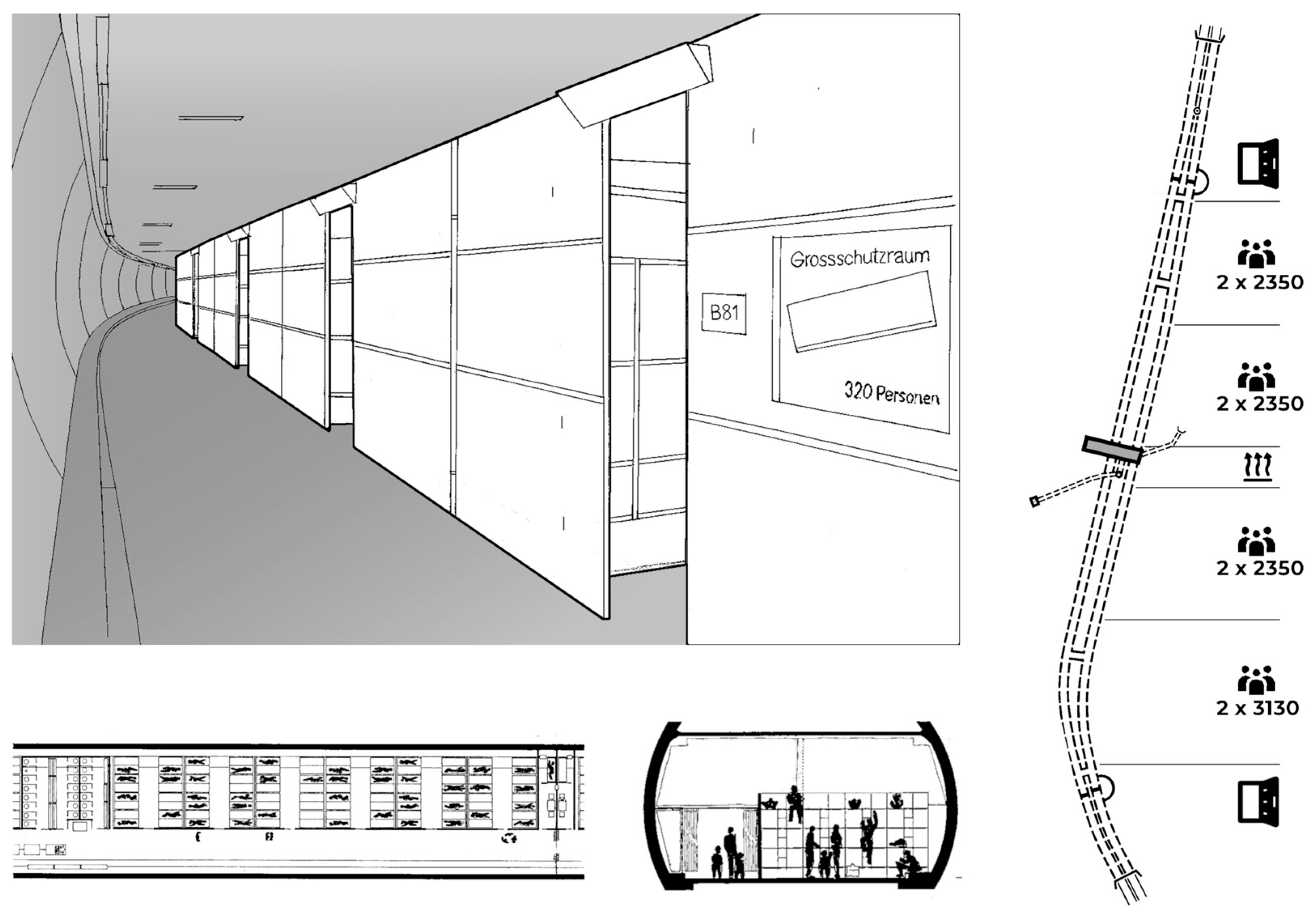

4.7. Sonnenberg Tunnel Shelter, Lucerne, Switzerland (Figure 7)

- Location: Lucerne, Switzerland;

- Intended use: Dual-purpose road tunnel and fallout shelters for civilians;

- Construction period: 1970–1976;

- Capacity: Originally 20,000 people, now around 2000 [76].

The Sonnenberg shelter is the largest civilian fallout shelter ever built. It is located in two parallel tubes of the motorway tunnel under the Sonnenberg hill in Lucerne. In the event of a nuclear emergency, it could be transformed from a road engineering object into a fully functional shelter: it was equipped with four huge gates, air filtration systems, medical facilities (with operating theatres and a 336-bed hospital), power generators, water tanks and living spaces for tens of thousands of people [77]. After the end of the Cold War, its protective function was reduced due to the high costs and logistic problems of mobilisation. Since 2008, the tunnel has only been used as a roadway, and a separate part of the shelter is preserved as a reserve civil protection facility and open to the public. Today, Sonnenberg remains a unique example of the integration of civil defence into urban infrastructure and a symbol of Cold War defence architecture [77,78]. The bunker section was designed with 1.5 m thick blast doors weighing up to 350 tonnes to seal off the road tubes from external shock, and the internal “cavern” contains multiple levels of reinforced concrete galleries outfitted with air handling systems, backup generators, water storage, medical zones, and living quarters rated for prolonged use [78,79].

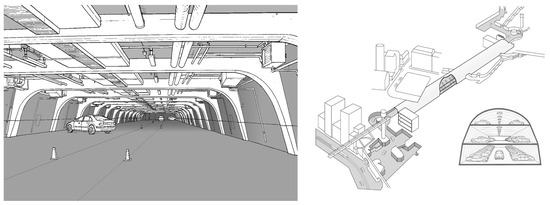

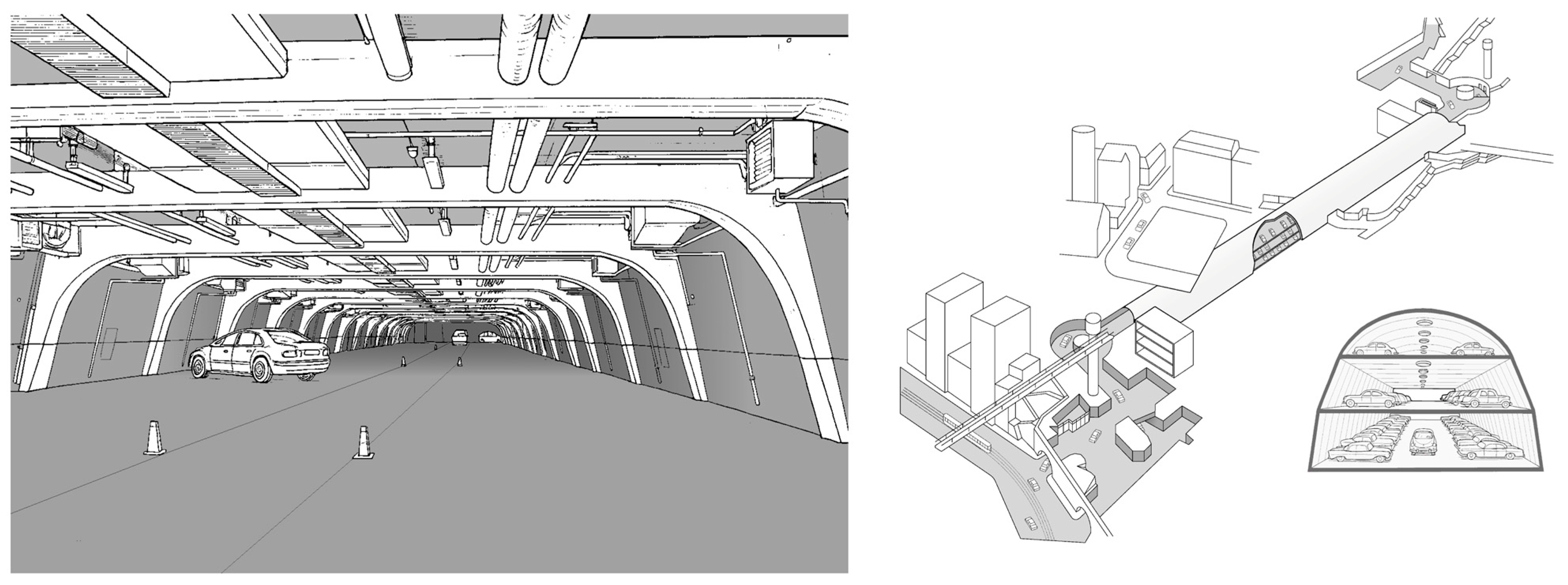

Figure 7.

Sonnenberg tunnel shelter, Lucerne, Switzerland. Visualisation of interior, plan, section and general scheme. Source: compiled by the authors.

Figure 7.

Sonnenberg tunnel shelter, Lucerne, Switzerland. Visualisation of interior, plan, section and general scheme. Source: compiled by the authors.

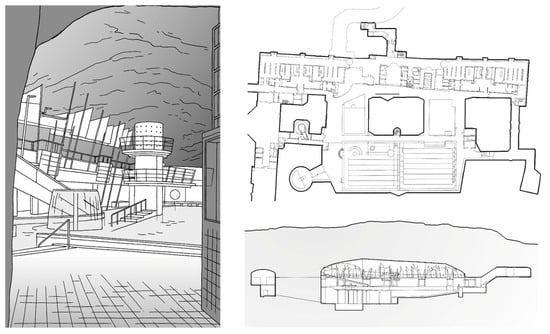

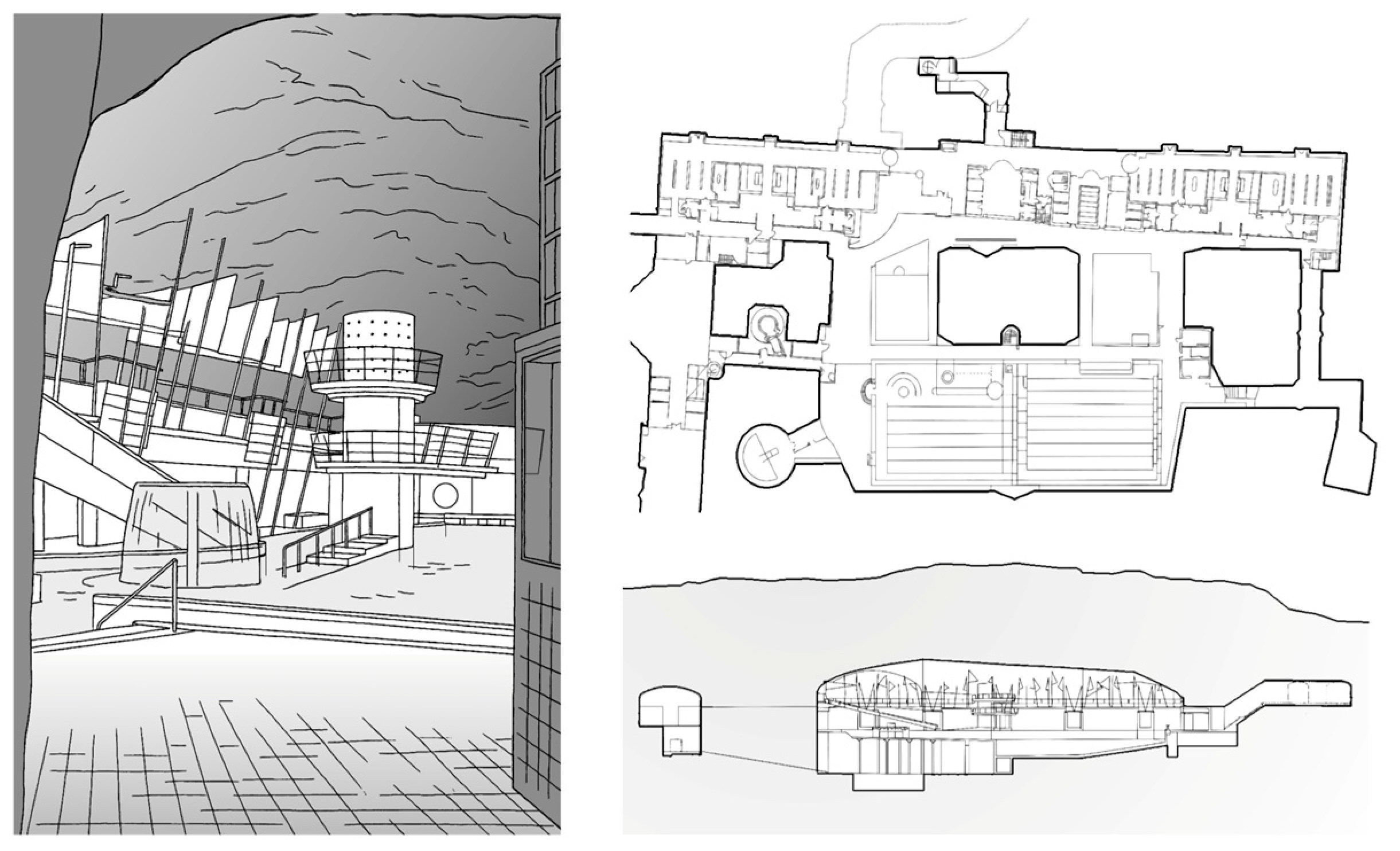

4.8. Shelter in Itäkeskus, Helsinki, Finland (Figure 8)

- Location: Itäkeskus, Helsinki, Finland;

- Intended use: Multipurpose facility—public swimming pool and civil defence shelter;

- Construction period: 1993;

- Capacity: 3800 persons.

Helsinki began building an extensive network of underground facilities in the 1980s, so that it now has about 400 facilities and 295 km of tunnels, the deepest of which is about 100 m below sea level. Today, 90 of these spaces are dual-purpose facilities, designed to meet every day needs with the possibility of reinforcement for ‘crisis times’, as exemplified by the Itäkeskus swimming pool in Helsinki. It is a perfect example of the integration of recreational infrastructure with a civil defence function [80]. Located 15 m deep in the granite rock, it serves as a popular swimming pool complex on a daily basis, which can be transformed into a fallout shelter for 3800 people within 72 h. In this situation, the pools are emptied, the showers are fitted with a decontamination function and the individual rooms are adapted to meet protective needs. It is equipped with a massive explosion-proof door, an air filtration system and pressure valves. Although the components are regularly tested, the shelter has never been used in an emergency. According to Helsinki’s civil defence structural guidelines, rock-cut shelters like this are dimensioned to withstand overpressure and collapse loads by virtue of the surrounding granite rock and reinforced concrete linings; ventilation is supported by mechanical air filters with redundancy, while ingress and egress are controlled via blast-rated doors and pressure valves [81].

Figure 8.

Shelter in Itäkeskus, Helsinki, Finland. Vizualization of interior, plan and section. Source: compiled by the authors.

Figure 8.

Shelter in Itäkeskus, Helsinki, Finland. Vizualization of interior, plan and section. Source: compiled by the authors.

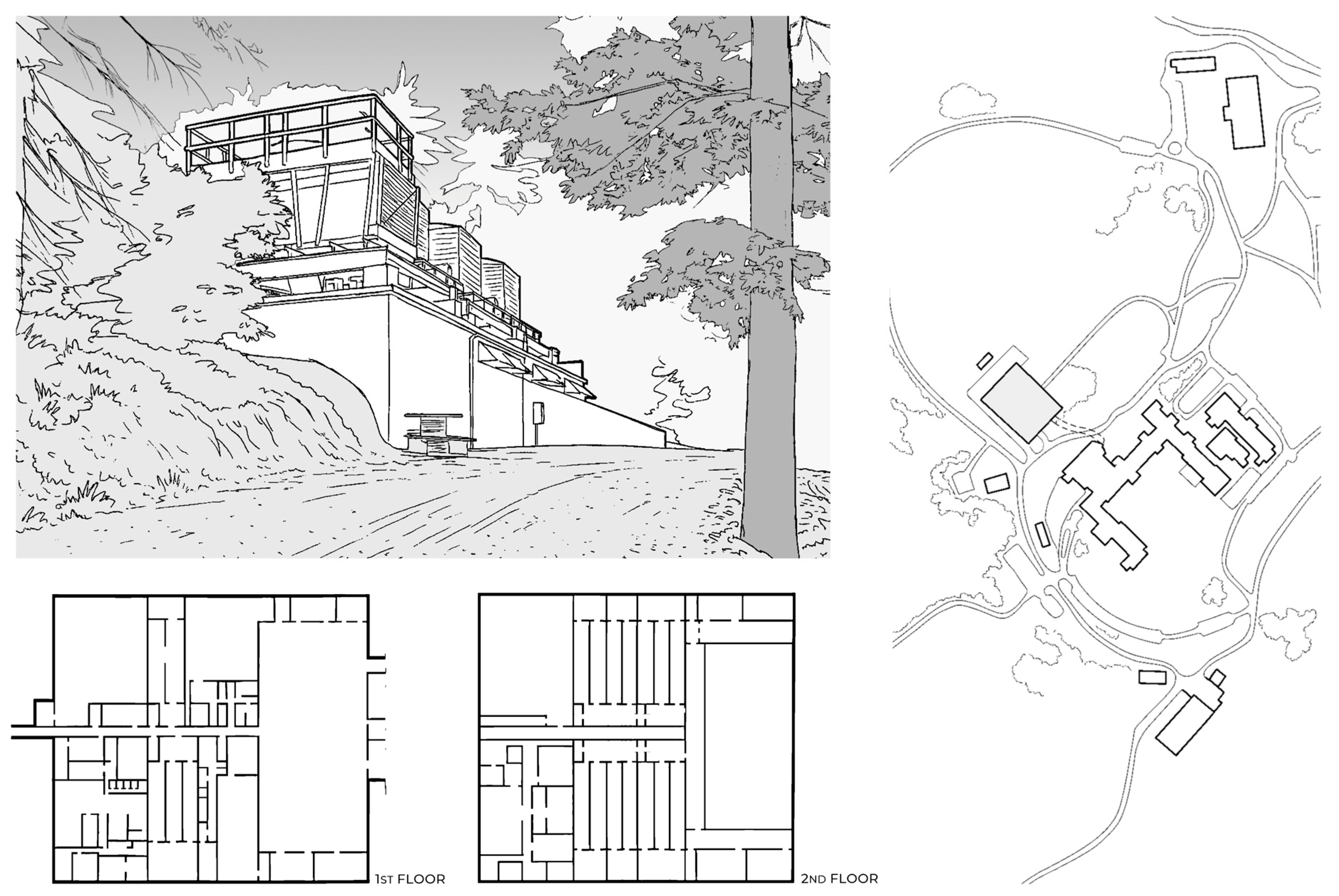

4.9. Civil Defence Management Shelter Under a Primary School, Przemyśl, Poland [82] (Figure 9)

- Location: Przemyśl, Poland;

- Intended use: Civil defence management post for local authorities;

- Construction period: 1966;

- Capacity: Around 70 people.

The shelter, located in the basement of a primary school in Przemyśl, is a typical example of Cold War defence infrastructure integrated with an educational facility [83]. It was established in 1966 as a clandestine facility, designed to manage civil defence in the event of a military threat. It was not intended for the civilian population, but for select personnel—civil servants, liaison officers and civil defence specialists, around 70 people in total [84,85]. Because of its critical function, it was intended as a fully autonomous facility capable of long-term operation. It had a living area, a command centre, a communication hub and sanitary and technical facilities. The facility had its own generator, ventilation systems with chemical and biological filtration, water tanks, and contamination detection equipment. During the Cold War, the facility was top secret and accessible only to trained officers approved by the Security Service. After 1990, it lost its operational significance and the complex was handed over to the school. Today it has been restored and turned into a civil defence museum, while retaining its unique authenticity as one of the best-preserved shelters in Poland.

Figure 9.

Civil Defence Management Shelter under a primary school, Przemyśl, Poland. Vizualisation of interior. Source: compiled by the authors.

Figure 9.

Civil Defence Management Shelter under a primary school, Przemyśl, Poland. Vizualisation of interior. Source: compiled by the authors.

4.10. Underground School-Shelter in Molodizhne, Ukraine (Figure 10)

- Location: Molodizhne, Odesa Oblast;

- Intended use: Civilian bomb shelter (anti-radiation/fallout shelter) serving as a below-ground school and a local cultural and youth centre [86];

- Construction period: 2024–2025;

- Capacity: approx. 700 persons;

The anti-radiation/fallout shelter in Molodizhne is the first of its kind to be completed in the Odesa Oblast as part of the ‘New bomb shelters for Ukrainian schools’ programme [87,88]. It officially opened on the secondary school premises in April 2025, giving 700 pupils of this school the opportunity to return safely to traditional learning despite the ongoing war. The investment was funded by the European Union and the Lithuanian and Irish governments, with a budget of EUR 2.4 million [89]. The shelter was constructed as a separate embedded building on the school premises [90], designed in accordance with the latest civil protection standards and requirements for underground facilities of this type. The entire area of 667 m2 fulfils a dual function, serving as a shelter in times of danger, while in peacetime it can be used as an educational and social space. It houses full-fledged classrooms, two gymnasiums, a psychological support room and a rehabilitation exercise room. The facility is equipped with a special lift for wheelchair users, making it fully accessible to people with disabilities. In line with the dual-purpose concept, the shelter’s infrastructure also allows it to be used for after-school activities and recreation: there is a dedicated space for chess, table tennis, basketball, and even a mini football pitch. In addition, a mini-cinema and a multimedia room have been created at the site, and the local community started creating a small local history museum inside the shelter. To ensure energy independence, equipping the building with solar panels is planned, while all life-support systems, from ventilation to emergency power supply, meet current standards to ensure the long-term safety of users even in the event of prolonged emergencies [87].

Figure 10.

Underground school-shelter in Molodizhne, Ukraine. Vizualisation of interior. Source: compiled by the authors.

Figure 10.

Underground school-shelter in Molodizhne, Ukraine. Vizualisation of interior. Source: compiled by the authors.

5. Results

Table 1 shows a comparative assessment of the shelters analysed here, according to four main criteria (A–D) corresponding to key aspects of the integration of the shelter with the city. These criteria include:

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of shelters in terms of sustainability criteria.

- (A) functional integration with the city—the extent to which the shelter integrates into the daily functioning of the city;

- (B) minimisation of interference with the urban fabric—assessing to what extent the completion of the shelter requires changes in existing buildings or infrastructure;

- (C) self-sufficiency and renewability of resources—the ability of a shelter to function independently (e.g., through its own sources of energy, water, food) and the use of renewable resources;

- (D) inclusiveness vs. exclusiveness—the social character of access to the shelter, i.e., whether it is universally accessible or intended for a narrow, privileged group.

Each shelter has been analysed in terms of the feasibility of implementing the solution in contemporary European urban settings, with a particular focus on the constraints imposed by the dense urban fabric. This means that in addition to the theoretical advantages, urban realities were taken into account—e.g., does the construction or adaptation of the shelter require deep interference with the existing city structure, does it infringe on existing buildings? If so, they have been identified as difficult to apply in contemporary realities, as reflected in the table. The evaluation methodology was a qualitative comparative analysis. For each criterion, it was checked whether the given example of the shelter complies with the established guidelines. The structure of the table includes rows corresponding to the individual shelters under analysis and columns for criteria A, B, C and D. The table cells use a simplified symbol system to allow a quick comparison of the different solutions. An ‘X’ indicates that the criterion has been met by the shelter in question. The ‘-’ (pause) symbol indicates that the given criterion has not been met. If a criterion is considered not to be applicable to a specific case (for example, because of the specific context in which the shelter operates, or due to insufficient data), the symbol ‘NA’ (not applicable) is entered in the table. This is the case when a certain aspect could not be reasonably assessed (e.g., when a shelter is located outside a densely built-up area, the issue of interference with the urban fabric may be irrelevant). For criterion [D] on social inclusivity, separate letter designations were used instead of a binary pass/fail assessment: ‘I’ indicates an inclusive nature (shelter available to the general population, promoting equality of access), while ‘E’ indicates an exclusive nature (intended for a limited group of people, e.g., only government or military personnel).

The assessment presented in the form of a table illustrates a hypothesis: do the existing shelters (sometimes historical) fit into the modern concept of urban sustainability, and to what extent? Comparing specific cases according to uniform criteria [A–D] makes it easy to see both good practices and shortcomings—e.g., which solutions have achieved successful integration into city life or have minimal spatial impact, and which are based on approaches that are difficult to reconcile with the constraints of European metropolises. This compilation of results forms the basis for formulation of design recommendations for the New Fallout Shelter Standard (NFSS).

6. Discussion

The study indicates that the best relationship with the city is provided by shelters adapted inside existing buildings or in infrastructure, such as in the basements of sports halls, in shopping centres or in traffic tunnels. They integrate civil defence services with the maintenance of public order. The shelter at Itäkeskus combines recreation with protection, the Sonnenberg tunnel fulfils both a road function and a shelter function in a crisis situation. As a result, the maintenance of these facilities is guaranteed by daily use: as users note, ‘The shelters are very well-maintained because people are using them in normal times’ [91]. Classic shelters built from scratch outside urban centres require significant financial and infrastructural investment, making them difficult to replicate on a large scale in European conditions. In addition, the ratio of costs to potential benefits resulting from population levels is unfavourable. In the assumed NFSS model, high functionality (criterion A) should go hand in hand with minimal disruption to the urban fabric (criterion B), especially when shelters are planned already at the urban design phase or are adapted to existing basements or car parks.

The self-sufficiency and renewability of resources (criterion C) of the sites analysed have different profiles. Military facilities like the Sonnenberg and the AT&T skyscraper were designed to be completely autonomous, and were equipped with electricity generators, air filtration plants, water and food supplies for long periods. They exemplify the highest level of technical resilience, but at the cost of gigantic expenditures. The modern approach to sustainability instead suggests hybrid solutions: urban shelters can draw energy from local renewable sources and use the municipal water network, while maintaining a self-sufficiency mode for times of crisis. For example, with its current supply of water and electricity, the Itäkeskus swimming pool could maintain essential functions in an emergency mode thanks to back-up generators. The NFSS model should include solutions involving energy-saving and renewable technologies, such as solar panels on the surface or rainwater harvesting tanks, as equipment for the new shelter, in accordance with the spirit of sustainability.

From a historical perspective, the social function of shelters (criterion D) has evolved from an exclusive to an inclusive model. The best-equipped Cold War shelters were often intended for the elite, i.e., politicians and military personnel, and were inaccessible to the general public [12]. Examples include the secret shelter under a school in Przemyśl and the elegant apartments for congressmen in Greenbrier—these are restricted access solutions. In contrast, the concepts currently being explored aspire to universality: in Finland, concrete shelters under the city are available to the entire population, and the law mandates that they be built in spaces beneath large public buildings. This paradigm shift is met with EU recommendations, e.g., the Sauli Niinistö report recommending that the expansion and modernisation of general shelters should take into account the needs of the community, such as protection from cuts in the supply of power and heating, etc., which would increase survivability and build social trust [92]. In addition, as Shpiliarevych, Kosmider and Jagusiak write, it would not only fulfil a protective function, but also become places to build community and resistance to the aggressor [38]. To address this, the NFSS should promote inclusivity—shelters designed ‘for all, not the select few’.

The evolving dual-use concept of shelters raises the question of how new civic and recreational functions align with the original life-saving purpose of such structures. While daily use improves maintenance and public acceptance, it must not compromise readiness in emergencies. Within the NFSS framework, the conversion from normal to protective mode should take no longer than seven days, during which non-defensive elements are removed and the facility is inspected, sealed, and prepared for use. In wartime, all non-protective activities would be suspended, and trained management staff would oversee mobilisation and operation.

Maintaining this balance requires regular system testing, personnel training, and public awareness to ensure that everyday accessibility does not weaken emergency performance. The NFSS promotes a staged preparedness model that allows flexible adaptation depending on the threat level.

Implementation of these strategies is limited by high costs, restricted financing, and legal or political barriers. Successful adoption will depend on coordinated funding mechanisms that combine national, municipal, and EU resources, as well as a clear division of responsibilities between central and local authorities. NFSS principles should align with existing civil protection and spatial planning frameworks, such as the EU Civil Protection Mechanism and national crisis management acts, and be integrated into urban adaptation, revitalisation, and security programs.

Such institutional transformation is already visible in Poland, where legislation on civil protection is being revised and professional training for architects and engineers in protective design has begun. These initiatives, driven by the rising perception of military threat in Eastern Europe, illustrate a broader shift toward reconciling everyday functionality with readiness for crisis.

Finally, effective NFSS implementation requires cross-sectoral collaboration between architects, planners, engineers, emergency services, and authorities to ensure that protective architecture becomes a practical and socially accepted component of sustainable urban development.

Practical recommendations: Designers and urban planners should learn from the best examples. The core idea of the NFSS is to treat the shelter as part of the city’s natural and social ecosystem. In other words, the shelter is to be not a ‘black box’ blocking the city, but a ‘milieu’—a shared resource serving the whole society [93]. As the researchers postulate, defence structures can be reinterpreted as a ‘landscape heritage’ combining climatic and social aspects (the so-called common good). Hence, the NFSS should promote solutions that will provide environmental resilience, e.g., a biologically active surface above the shelter, infrastructure supplement, rainwater collection, ventilation systems using renewable energy, and biophilic elements improving the psychological wellbeing of users. It is also important to introduce design guidelines that take into account emergency evacuation and medical care in shelter conditions and to ensure accessibility for all groups, e.g., platforms and lifts for people with disabilities. Regardless of the environmental guidelines, it is clear that the construction of shelters requires the use of extremely durable materials, making them extremely material-intensive and costly—their construction involves a great deal of intrusion into the natural and urban environment [29]. Conditions in contemporary Central Europe impose significant implementation constraints. The density of development makes it difficult to build new large-scale bunkers, and political and economic costs are high. The application of the multi-use shelter concept, which involves the creation of dual functions for objects, seems to be the most promising. The Finnish examples show that a shelter integrated into the daily infrastructure is efficient—it is ready within 72 h—and the facilities are continuously serviced thanks to daily use.

The NFSS—Operational Outline

The New Fallout Shelter Standard (NFSS) is not a single technical solution, but a structured approach to planning protective infrastructure in dense urban environments. Its purpose is to shift the design logic from the bunker as an isolated defensive object toward the shelter as an integrated urban facility.

Architectural dimension—NFSS assumes that the shelter should be rooted in a primary everyday function, with the protective role activated only when needed. This means combining defence with other public or municipal uses instead of creating monofunctional facilities that remain dormant. The preferred locations are spaces already embedded in the city’s circulation—beneath sports halls, transport nodes, schools or car parks—so that maintenance is guaranteed by daily use. Accessibility for all user groups is treated as a baseline requirement.

Technical dimension—NFSS introduces the principle of “hybrid autonomy”: the facility normally relies on the urban network but must be capable of temporary disconnection and independent operation during a crisis. Instead of the Cold War model of months-long isolation, a graduated operational capacity is recommended—for sudden attacks (hours), extended outages (days), and, only in selected cases, prolonged emergencies. Renewable technologies and low-resource systems are treated not as symbolic additions, but as a practical means of reducing the cost of readiness.

Regulatory dimension—Because a shelter is useless if no one is formally responsible for it, the NFSS requires that each facility has a clear operator and rules for activation. Someone specific must manage the site, keep it maintained, and decide on its day-to-day functioning. The formal decision to switch the facility from its civilian role to its protective role should be regulated at the level of national law, so that mobilisation is not left to ad hoc local interpretation. In most cases, everyday operation and emergency operation can be handled by the same institution, which ensures continuity and reduces costs. In central urban areas this activation must be fast, because there is no space for alternative protective infrastructure—the shelter is the only feasible form of protection available.

Under these conditions, NFSS treats the shelter as part of the public realm—a civic utility designed for continuity of use rather than a closed, stand-by structure.

7. Conclusions

Today many modern European metropolises face the need to redefine their civil security policies in the context of real military threats. The results of the analysis clearly show that the existing model of the shelter as a segregated exclusive military facility does not fit the requirements of the 21st century. Instead, it is necessary to develop a new approach—an open, integrated and socially inclusive one—that takes into account both dense urban development and the goals of sustainable development, which will ultimately lead to greater social resilience. This direction is consistent with recent studies, such as Li [46], which emphasise the integration of renewable energy, resource efficiency, and adaptive modular design into protective infrastructure. Together with the findings of this research, these perspectives confirm that the future of shelter architecture lies in combining technical resilience with environmental and social sustainability, aligning protection systems with the long-term objectives of urban development. As a result of the research, a number of key postulates for the creation of the New Fallout Shelter Standard (NFSS) emerge:

- Functional integration: Shelters with the dual function of daily use and emergency protection show the greatest potential. Their presence in sports halls, car parks or swimming pools indicates that protective functions can coexist with urban life without alienating the space. The dual-use concept of shelters requires maintaining a careful balance between everyday functionality and emergency readiness. Within the NFSS framework, facilities should be capable of conversion to protective mode within seven days, supported by regular testing, staff training, and clear institutional responsibility across national and local levels. Emerging initiatives in countries such as Poland—including new civil protection legislation and training for architects and engineers—demonstrate that integrating protective architecture into sustainable urban systems is both feasible and increasingly necessary.

- Minimal interference with the urban fabric: Facilities adapted to the existing infrastructure or envisaged in the planning phase minimise environmental and social costs, as opposed to separate, single-purpose bunkers that require major interventions in the city structure. In this context, underused or abandoned urban spaces—such as disused basements, service tunnels, or underground car parks—can be reactivated as part of a broader protective network. The spaces located beneath city roads can also be utilised as structural components of this system, linking dispersed shelter facilities into an integrated urban safety grid.

- Self-sufficiency and resilience: Models based on full autonomy are costly and difficult to replicate. Therefore, the NFSS should promote hybrid solutions that remain partly connected to urban infrastructure yet are capable of operating independently for a limited period. In this context, the incorporation of renewable technologies and efficient resource management systems becomes particularly important. The authors propose the “6–6–6 principle”, which defines three levels of operational autonomy: 6 h—short-term emergency sheltering during sudden air raids; 6 days—protection during prolonged or intense shelling; 6 months—extended occupation in the case of nuclear incident.

- Social inclusivity: The shelters of the future must be designed as shared infrastructure accessible to all, regardless of social status, age, or physical ability. This approach not only increases the overall effectiveness of protection systems but also strengthens social cohesion and citizens’ trust in public institutions. It is widely recognised that every country has its own legal regulations concerning accessibility for people with disabilities. Within the NFSS framework, the authors can only emphasise the necessity of strictly adhering to these regulations and of consistently applying universal design principles—particularly those that facilitate efficient evacuation and safe movement under panic conditions.

Looking at the above issues most broadly, yet synthetically, it can be said that the modern urban fallout shelter should be considered as an element supporting infrastructural resilience—as a component of the long-term resilience of the city that proves useful not only in extreme situations but also as a space for everyday activity, education and social integration. The key to the success of such a systemic approach is the flexibility, multi-functionality and planning and legal facilities that support the implementation of such facilities throughout the city. The model proposed in the research, denoted NFSS, must reflect the requirement for an interdisciplinary approach that combines architecture, urban planning, protective engineering, sociology and environmental psychology. Only in this way will it be able to adapt to local urban, legal and cultural circumstances. Only such a comprehensive model has the potential to become a real European standard enabling the safety of the population to be increased without sacrificing the quality of urban life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., R.A. and P.K.; methodology, A.C., R.A. and P.K.; software, A.C., R.A. and P.K.; validation, A.C., R.A. and P.K.; formal analysis, A.C., R.A. and P.K.; investigation, A.C., R.A. and P.K.; resources, A.C., R.A. and P.K.; data curation A.C., R.A. and P.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C., R.A. and P.K.; writing—review and editing, R.A.; visualization, P.K.; supervision, R.A.; project administration, A.C.; funding acquisition, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Warsaw University of Technology under the Excellence Initiative: Research University (IDUB) programme, grant ARCHIURB IDUB, project number 504/04496/1010/45.010016.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 4. for searching and translating non-English sources. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EU | European Union |

| US | United States |

| NFSS | New Fallout Shelters Standard |

| FOCP | Finnish National Rescue Association |

References

- Płachciak, A. Geneza Idei Rozwoju Zrównoważonego. Ekon. Econ. 2011, 5, 231–248. Available online: http://cejsh.icm.edu.pl (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- MSB—The Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency. Available online: https://www.msb.se/en/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Frontpage—SPEK, Frontpage—SPEK. Available online: https://www.spek.fi/en/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Federal Office for Civil Protection FOCP. Federal Office for Civil Protection FOCP. Available online: https://www.babs.admin.ch/en/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).