Abstract

Thermochromic windows can dynamically modulate solar radiation to optimize indoor thermal and visual comfort. However, their performance is strongly influenced by window geometry parameters, while the optimal geometrical conditions for evaluating their performance remain unclear. This study aims to investigate how window geometry parameters, namely orientation, window-to-wall ratio (WWR), and sill height, influence thermochromic windows’ performance, as well as to identify the proper geometry parameters for performance evaluation. The improved HNU Solar model and EnergyPlus were employed for the simulation of an office building located in Changsha in south China, to assess indoor thermal and visual comfort with thermochromic windows under different conditions of window orientations, WWRs (30–60%), and sill heights (0–1.5 m). The results reveal that on a typical summer day, with thermochromic windows, the solar-induced thermal discomfort duration was lowered by 60.9%, 82.4%, 63.7%, and 96.4% for east, south, west, and north windows, respectively; visual discomfort duration is also mitigated by 28.6%, 37.4%, and 45.4% with east, south, and west windows. As the WWR increases from 30% to 60%, with thermochromic windows, indoor thermal comfort decreases, whereas indoor visual comfort increases; as the sill height increases from 0 to 1.5 m, both thermal and visual discomfort time ratios first increase and then decrease, while the reduction in the thermal or visual discomfort duration by thermochromic windows gradually diminishes. In addition, the proper WWR range for evaluating the performance of thermochromic windows is from 40% to 50%, and the corresponding sill height range is from 0.5 to 1 m. These findings provide practical guidance for identifying the feasibility of thermochromic windows under different window geometries, as well as the selection of window geometry parameters for the performance evaluation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Windows, as an integral element of the building envelope, play a pivotal role in facilitating daylight penetration and natural ventilation [1]. However, owing to their characteristics of high thermal transmittance and solar heat gain, windows serve as primary conduits for thermal exchange between the interior and exterior environments [2]. This dual function significantly contributes to increased building energy consumption [3,4], and exerts a profound influence on the thermal comfort [5,6,7] and visual quality experienced [8] by indoor occupants. To address this challenge, researchers have extensively investigated window geometry design across diverse building types and climatic conditions [9,10]. By optimizing parameters like window-to-wall ratio (WWR) [11,12], shape [13], and orientation [14], they aim to improve indoor thermal comfort and daylight conditions. Meanwhile, window material technology has also evolved [15], from early low-emissivity (low-e) glass [16,17] to advanced low-e coating materials [18] and smart variable-tint windows [19,20], all aimed at regulating solar radiation to lower building energy consumption and improve indoor thermal and visual environments. For example, Teixeira et al. [21] evaluated the thermal, visual, and energy performance of glazing systems with various solar control films (SCFs) in office rooms in Lisbon, finding that the highly reflective SCF achieved thermal and visual comfort for about 41–43% of the occupied time. Qiu et al. [22] investigated the retrofitting of existing high-rise buildings by integrating vacuum insulating glazing (VIG) as secondary glazing. Field measurements and simulations in a Hong Kong office showed that the VIG retrofit reduced heat gain by up to 85.3% and improved thermal satisfaction by 9.2%. Es-sakali et al. [23] investigated the integration of static glazing with dynamic coatings in a semi-arid lightweight building, showing that electrochromic films can significantly improve energy efficiency as well as thermal and visual comfort.

Smart windows can be categorized into active [24] and passive types [25]. Active smart windows require external energy input set or controlled by humans, such as electrical voltage or current, to modulate their optical or thermal properties, and they do not automatically respond to the ambient environment. A good example is electrochromic windows [26]. In contrast, passive smart windows operate without needing external artificial energy input and they respond to environmental conditions such as temperature or solar radiation, and adjust their optical transmittance automatically when the ambient environment changes, with examples being thermochromic [27] and photochromic [28] windows. As a representative passive smart window technology, thermochromic windows exhibit significant potential in energy savings and enhancing indoor comfort due to their ability to adaptively regulate optical properties [29]. These advantages have drawn significant attention in both academic research and the commercialization of energy-efficient window solutions [30,31,32].

Many researchers have conducted extensive research on how windows with different geometry parameters affect indoor environments [33]. For example, Xiang et al. [34] proposed a new indicator to evaluate the effect of solar radiation on occupants’ thermal comfort under different window parameters. The results indicated that the areas within 2.0 m of a window are prone to daylight discomfort; meanwhile, every 0.1 decrease in the WWR value decreases the discomfort time ratio by 3–4 percentiles, while every 0.1 decrease in solar transmittance reduces the ratio by 4–6 percentiles. Ashrafian et al. [35] investigated the impact of different window transmittance ratios and window configurations on indoor visual and thermal environments. They found that the window transmittance ratio at 50% forms an indoor environment with sufficient comfort. Song et al. [36] conducted seasonal field experiments in an office room to assess the thermal comfort of occupants near windows. They found that transmitted solar radiation strongly affected comfort by creating non-uniform thermal environments with uneven mean radiant temperatures. The acceptable operative temperature range was 22.5–25.5 °C without direct sunlight, and 22.0–24.5 °C with direct sunlight. Song al. [37] established a new method to evaluate the effect of indoor solar radiation. The results showed that keeping the solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) at 0.3 across all climate zones can decrease discomfort time by more than 86%. Xie et al. [38] investigated indoor thermal environments with different WWRs, and they found that selecting a low WWR may help improve indoor thermal comfort.

In addition, many researchers have extensively studied indoor thermal and visual comfort with thermochromic windows. Zhang et al. [39] developed five color-varied thermochromic coatings and evaluated their performance using an office building model in south China. Their simulations showed that the thermochromic coatings lowered the building surface temperature by 5.9–7.8 °C in summer but raised it by 1.3–4.6 °C in winter, which helps make buildings cooler in summer and warmer in winter. Liu et al. [40] developed three types of VO2-based thermochromic windows and evaluated their performance in Changsha, Ankara, and New York under WWRs at 30%, 60%, and 90%. The results indicate that thermochromic windows enhance daylight availability by 5–15% compared with double-glazing windows, while consistently increasing hours within the acceptable glare range, particularly at higher WWRs (60% and 90%). Costanzo et al. [41] investigated the energy-saving, daylighting, and thermal environment of buildings with thermochromic windows. The results demonstrated that thermochromic windows reduce the duration when indoor temperature is higher than 26 °C under free-running conditions, while maintaining acceptable daylight illuminance indoors. Liu et al. [42] developed a chalcogenide-based thermochromic window responsive to near-infrared radiation, which achieved energy savings and reduced indoor temperature by 8.0 °C compared with normal windows. Yang et al. [43] proposed a novel method for the evaluation and optimization of thermochromic window performance. Their simulation results showed that the optimized thermochromic windows could maintain the discomfort time less than 10%. Jiao et al. [44] developed a novel thermochromic window, which has a switchable three-state function and is able to lower indoor temperatures by 9.3 °C in warm season.

1.2. Research Gaps

Despite the remarkable progress made in the current research, the following research gaps still exist:

- (1)

- The current studies on the effects of window geometry parameters (like orientation, WWR, and sill height) on indoor environments seldom incorporate solar-induced thermal comfort while considering the seasonal comfort thresholds of solar radiation intensity on indoor occupants. The previous work by the researchers [34] partly explored this topic, but the seasonal thresholds of indoor solar intensity for thermal comfort were not involved. The ignorance of the above-stated issue may result in an inaccurate evaluation of window performance.

- (2)

- Although many studies have explored thermochromic windows’ effectiveness, no studies clearly answer how solar-induced thermal comfort and daylight change under different thermochromic window geometry parameters, compared with normal windows. For example, a question remains as to how the ability of thermochromic windows to eliminate solar-causing thermal and visual discomfort changes when the WWR decreases. Further work on the above-stated issue can help to determine the real effects and the application feasibility of thermochromic windows under different window designs.

- (3)

- In addition to the second research gap, although many studies have investigated the performance of thermochromic windows, few provide a clear conclusion regarding the window geometry parameters that are proper for evaluating thermochromic windows’ indoor environmental performance. For example, a small thermochromic window may have negligible thermal and visual discomfort, but it may result from the small window area rather than the regulation ability of thermochromic windows. However, the existing studies have no clear answer to the above-stated issue.

1.3. The Work of This Study

To fill the above-stated gaps, this study investigates the solar-induced thermal and visual comfort performance of thermochromic windows in an office building with various window geometry parameters, based on the meteorological data of Changsha, a representative city in southern China. The main objectives of this research are as follows:

- (1)

- To incorporate the intensity calculation and seasonal comfort thresholds of solar radiation falling on indoor occupants into building environment simulation with thermochromic windows under different window geometry parameters;

- (2)

- To investigate the effects of WWR and sill height on the thermal and visual comfort performance of thermochromic windows, which are ignored in the existing studies;

- (3)

- To identify the range of window geometry parameters for thermochromic windows’ accurate performance evaluation.

2. Methods

2.1. Workflow

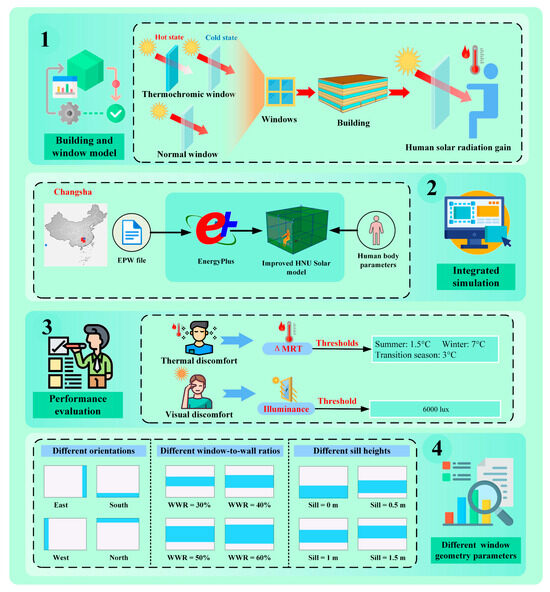

The workflow for evaluating the impact of window geometry parameters on indoor thermal and visual comfort of thermochromic windows in office buildings is depicted in Figure 1. First, two window models, namely normal window and thermochromic window, were developed using Window 7.8 [45] to obtain the detailed optical and thermal properties, including the U-value and solar transmittance (Section 2.2). These models were then entered into an EnergyPlus-based building model [46] (Section 2.3), with the meteorological data of Changsha. The improved HNU Solar model [47] was also adopted to calculate the increase in mean radiant temperature of indoor occupants caused by solar radiation (ΔMRT), which is then used to calculate the solar-induced thermal discomfort period using the seasonal solar intensity thresholds for maintaining human comfort [48] (Section 2.4). Simultaneously, the indoor daylight illuminance was also simulated and obtained via EnergyPlus [46] to quantify the over-illumination time period caused by solar radiation (Section 2.5). Moreover, a series of simulation cases was set up to explore the impact of window geometry parameters on thermochromic windows’ solar-induced thermal and visual comfort. Specifically, four window orientations (east, south, west, and north), four WWRs (30%, 40%, 50%, and 60%), and four sill heights (0, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 m) were investigated through comparative analyses (Section 2.6), to quantify the effects of window geometry parameters. Finally, the ranges of window geometry parameters for properly evaluating thermochromic window performance were identified.

Figure 1.

The workflow of the present study.

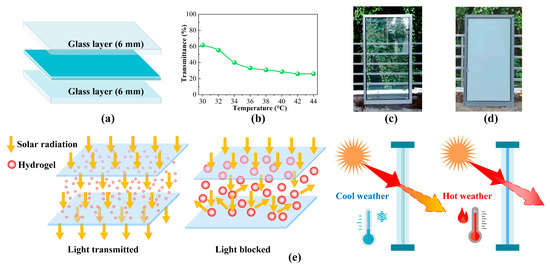

2.2. Thermochromic Window

The thermochromic window employed in this study consists of two layers of 6 mm glass with a 2 mm cement adhesive layer sandwiched inside, and its structure is illustrated in Figure 2a. Its transmittance increases from 26.2% to 61.7% as its temperature falls from 44 to 30 °C (see Figure 2b). The visual appearance of the thermochromic window in both cold and hot states is shown in Figure 2c,d. The color-changing material utilized in this thermochromic window is thermochromic polyacrylamide. Its color-changing mechanism is shown in Figure 2e, with the detailed descriptions available in Ref. [43].

Figure 2.

The characteristics of the investigated thermochromic window: (a) the structure, (b) the transmittance at different temperatures, (c) the high-transmittance state, (d) the low-transmittance state, and (e) the transmittance-regulation mechanism.

In addition, this study selected a normal double-layer tempered glass window as the comparative reference. This normal window has the same structural parameters as the thermochromic window, with the sole difference being that its intermediate layer is filled with air (instead of the thermochromic material). The thermochromic and normal window models were developed using the WINDOW 7.8 software [45] to calculate their overall heat transfer coefficients (U-values). The U-value of normal windows is 4.008 W/m2·K, the solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) is 0.695, the visible light transmittance (VT) is 78.6%, and the total solar transmittance is 74.9%. Relevant parameters of the above-stated two types of windows are represented in the Supplementary Section S1. In addition, these two window models were then imported into EnergyPlus [46] to integrate them into the building model, as stated in Section 2.3.

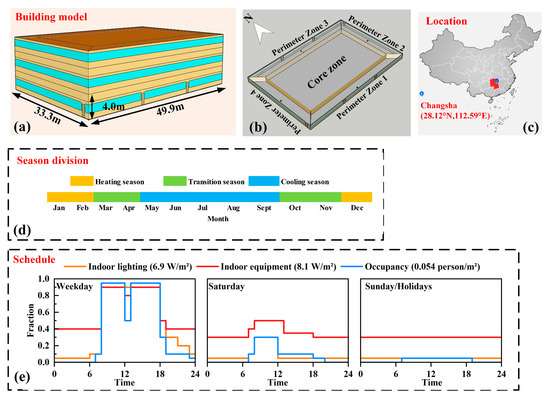

2.3. Building Model

An EnergyPlus model simulating an office building was employed in this study, with each floor measuring 4.0 m × 49.9 m × 33.3 m (height × length × width), as shown in Figure 3a. Each floor comprises five zones, with each perimeter zone having a depth of 4.6 m, as shown in Figure 3b. The building is assumed as being in Changsha, China (see Figure 3c), and has heating, cooling, and transition seasons throughout the year (see Figure 3d). The lighting power density, indoor equipment power, and occupant density of the building are shown in Figure 3e, and their detailed operating times are given in Supplementary Section S2 with references to [43,46,47,49,50]. The detailed simulation settings are given in Supplementary Section S3.

Figure 3.

The overview of the model setup: (a) the building dimension, (b) the zoning of the building, (c) the building location, (d) the season division, and (e) the indoor lighting, equipment, and occupancy schedules.

2.4. Solar-Related Thermal Comfort Evaluation

The comfort evaluation of the thermochromic windows will be biased if the solar radiation of the human body indoors is ignored [51]. In this study, the window-through solar heat gain of human body indoors was calculated using the improved HNU Solar model [47] and represented using ΔMRT, and the detailed calculation process is included in Supplementary Section S4 with references to [46,47,51,52,53]. The improved HNU Solar model used in this study has been validated in previous work [37,38], showing good agreement with the results of the commercial simulation software Radiance (Version 7.0) in terms of predicting solar radiation intensity of the human body whilst indoors (the difference is lower than 15%), which confirms the reliability and accuracy of the improved HNU Solar model.

According to our previous experimental studies, when ΔMRT is greater than the thresholds (upper limits), namely 1.5 °C [54] in summer, 3 °C [54] in the transition season, and 7 °C [48] in winter, indoor occupants will feel obvious discomfort [5].

Herein, the thermal discomfort time ratio caused by solar radiation (Pthermal_discomfort) [34] was employed to evaluate window performance with respect to solar-causing thermal comfort (since the indoor air temperature, humidity, and air velocity are within comfortable ranges with air conditioning systems), which represents the proportion of working hours experiencing the thermal discomfort caused by solar radiation (tthermal_discomfort) to the total occupied hours (toccupied). Specifically, tthermal_discomfort refers to the cumulative working hours during which the ΔMRT is greater than the solar intensity threshold for indoor thermal comfort. toccupied includes weekdays’ working periods, starting at 8:00 and ending at 17:00, totaling 9 h per day. Pthermal_discomfort is calculated as follows:

where ΔtΔMRT>threshold is the time step during which ΔMRT is higher than the threshold for thermal comfort (unit in 10 min).

Then, the reduction ratio of thermal discomfort duration by thermochromic windows (Pthermal_reduction) is calculated as follows:

where tthermal_discomfort_Normal is the thermal discomfort duration caused by solar radiation with normal windows and tthermal_discomfort_TC is the thermal discomfort duration caused by solar radiation with thermochromic windows, both units in hours.

2.5. Indoor Daylight Performance Evaluation

To assess the indoor daylight performance, the artificial lighting was turned off when only conducting daylight simulation, and a reference point was established at a position 2.0 m away from the window, and its height was set at 0.8 m. The daylighting control module in EnergyPlus [46] was employed to perform dynamic simulations of daylight illuminance at this reference point, producing temporal profiles of indoor daylight levels to quantitatively assess the window’s daylight performance.

When indoor daylight illuminance is higher than 6000 lux [55,56], it will cause significant discomfort for human vision. Therefore, in this study, the visual discomfort time ratio caused by solar radiation (Pvisual_discomfort) is quantified, which represents the ratio of working periods experiencing the visual discomfort caused by solar radiation (tvisual_discomfort) to the total occupied hours. Specifically, tvisual_discomfort refers to the cumulative working hours during which the daylight level is greater than 6000 lux. Pvisual_discomfort is calculated as follows:

where t>6000 lux is the total hours (during the total occupancy hours) when the daylight illuminance is beyond 6000 lux, (unit in 10 min).

The reduction ratio of visual discomfort duration by thermochromic windows (Pvisual_reduction) is calculated as follows:

where tvisuall_discomfort_Normal is the visual discomfort duration caused by solar radiation with normal windows and tvisuall_discomfort_TC is the visual discomfort duration caused by solar radiation with thermochromic windows, with both units in hours.

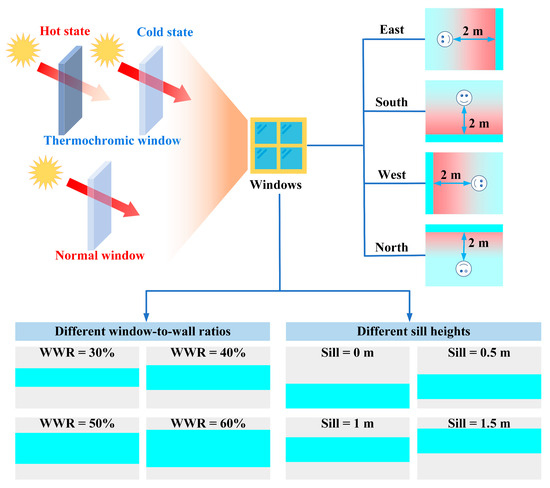

2.6. Window Geometry Parameters

The simulations assumed that the occupant was positioned 2 m away from the window. The effect of different reference points has been discussed in our previous work [43]. In this study, the reference point located 2 m from the window was adopted, balancing the solar exposure experienced by occupants. A 10 min simulation time step provided sufficient temporal resolution to capture rapid variations in solar radiation, while avoiding excessive computational cost. Furthermore, the optical properties of the thermochromic window were measured at different temperatures, ensuring an accurate representation of its transmittance transition behavior for simulations. As shown in Figure 4, simulations and analyses were conducted on thermochromic windows with various window orientations, WWRs, and sill heights, and the detailed case information is represented in Table 1. To be specific, first, four window orientations (east, south, west, and north) were included in every case. In Cases 1–8, both thermochromic and normal windows were examined with WWRs of 30%, 40%, 50%, and 60%, while the window centerline height was fixed at 1.37 m above the floor. The effect of sill height was examined in Cases 9–16, with the WWR being fixed at 40% and the sill heights at 0, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 m, respectively.

Figure 4.

The setup of window geometry parameters.

Table 1.

Simulation conditions.

3. Results

3.1. Example of Calculating Thermochromic Windows’ Comfort Performance

This section aims to present the detailed procedure of calculating the thermal comfort and daylight performance of thermochromic windows with different window geometry parameters, with the working hours (from 8:00 to 17:00) of a typical day (26 August) and the whole year as an example. The window has four orientations, while the WWR is set at 30%, and the sill height is 0.77 m.

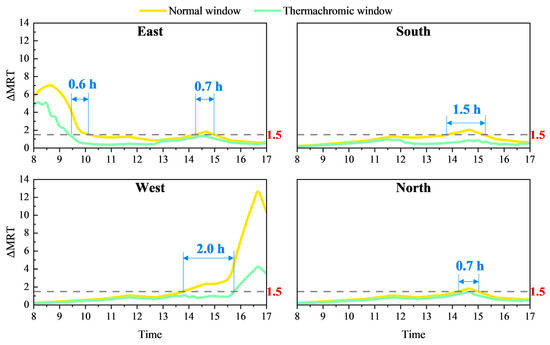

Figure 5 illustrates the ΔMRT values with normal windows and thermochromic windows on the typical day. According to the previous study of the researcher, the comfort threshold of ΔMRT in summer is 1.5 °C [54]. It is evident that thermochromic windows effectively lower the duration of thermal discomfort under different window orientations. Specifically, for the east window, thermal discomfort occurs between 8:00 and 10:00 when ΔMRT exceeds 1.5 °C, and thermochromic windows can reduce the duration by 47.1% (about 1.3 h reduced). Similarly, under the south, west, and north orientations, the periods of thermal discomfort occur from about 12:00 to 14:00, 14:00 to 17:00, and 14:00 to 15:00, respectively. The above-stated thermal discomfort durations are reduced by 100% (1.5 h), 60% (2.0 h), and 100% (0.7 h), respectively. On the whole, with normal and thermochromic windows, on a typical day, the average time ratios with thermal discomfort under four window orientations are 22.7% and 7.7%, respectively, and thermochromic windows decrease the thermal discomfort duration by 66.0% on average.

Figure 5.

The reduction in thermal discomfort duration by thermochromic windows on a typical day.

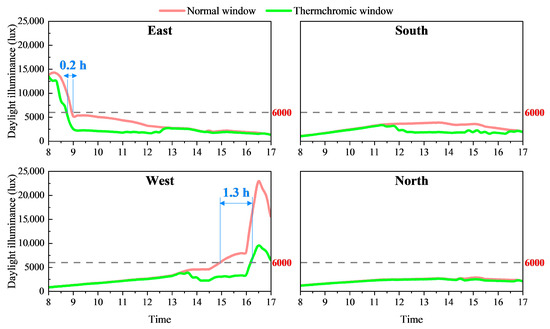

Figure 6 shows the daylight illuminance with two types of windows on a typical day. It is evident that visual discomfort periods primarily occur under the east and west window orientations, and thermochromic windows can reduce the duration of visual discomfort. To be specific, for the east window, visual discomfort occurs between 8:00 and 10:00 when the daylight illuminance exceeds 6000 lux, and thermochromic windows can shorten the time duration by 16.7% (about 0.2 h reduced). Similarly, for the west windows, the periods of visual discomfort occur from about 15:00 to 17:00, and the duration is correspondingly shortened by 61.5% (about 1.3 h reduced). While no visual discomfort occurs with the south or north windows. On the whole, with normal and thermochromic windows, on a typical day, the average visual discomfort time ratios under four window orientations are 1.4% and 0.8%, respectively, and thermochromic windows decrease the visual discomfort duration by 47.4% on average.

Figure 6.

The reduction in visual discomfort duration by thermochromic windows.

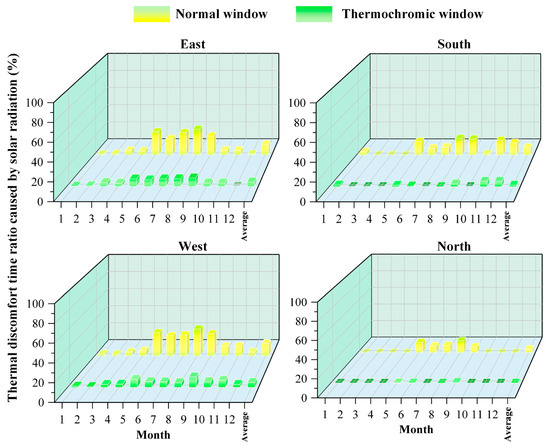

Figure 7 illustrates the monthly solar-induced thermal discomfort time ratios with two types of windows. Distinct seasonal variations are observed, with thermochromic windows providing significant mitigation in summer. Specifically, for the east window, the average monthly thermal discomfort time ratio is 11.8%, while thermochromic windows reduce it to 4.6%, with the duration of thermal discomfort being reduced by 60.9%. When the windows are in the south, west, and north orientations, the average monthly thermal discomfort time ratios are 8.7%, 13.9%, and 4.0%, respectively; with thermochromic windows, these values decrease to below 1.5%, 5.0%, and 0.1%, with the durations of thermal discomfort being reduced by 82.4%, 63.7%, and 96.4%, respectively. Overall, compared to normal windows, thermochromic windows can reduce the thermal discomfort time ratio to below 5% annually.

Figure 7.

The thermal discomfort time ratios with two types of windows in different months.

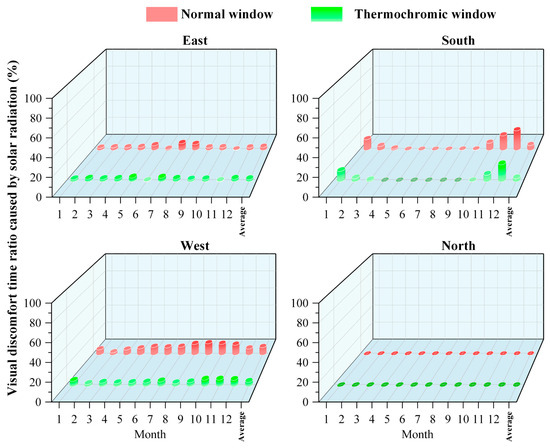

Figure 8 represents the monthly solar-induced visual discomfort time ratios with two types of windows. The results reveal clear seasonal variations across orientations, with thermochromic windows effectively reducing visual discomfort. Specifically, in the east orientation, the average monthly thermal discomfort time ratio is 3.4%, while thermochromic windows reduce it to 2.4%, with the visual discomfort duration being reduced by 28.6%. When the windows are in the south and west orientations, the average visual discomfort time ratios are 5.4% and 8.5%, while thermochromic windows reduce them to 3.4% and 4.7%, respectively, with the visual discomfort duration being reduced by 37.4% and 45.4%, respectively. In addition, no significant visual discomfort is observed for the north window. Overall, compared to normal windows, thermochromic windows can reduce the annual visual discomfort time ratio to below 4.7%.

Figure 8.

The visual discomfort time ratios with two types of windows in different months.

3.2. Thermal Comfort and Daylight Performance of Thermochromic Windows Under Different Window-to-Wall Ratios

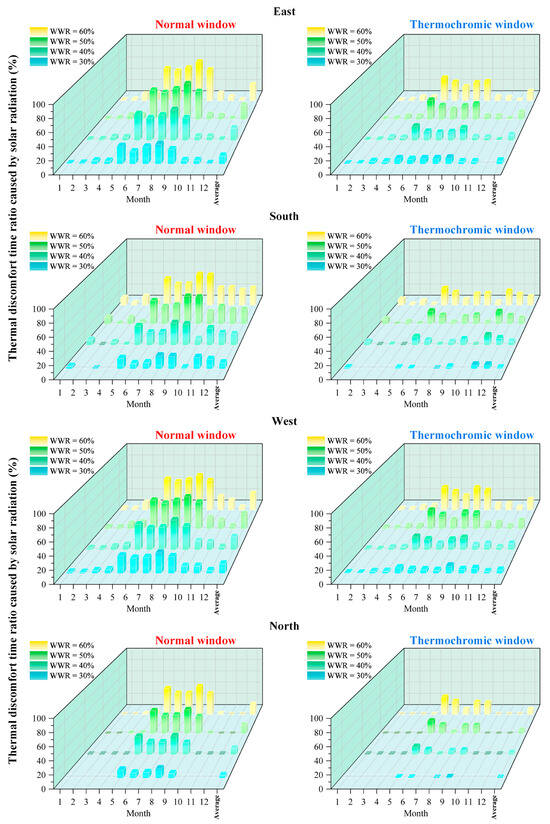

Figure 9 illustrates the solar-induced thermal discomfort time ratios with two types of windows under different WWRs. It can be seen that with the increase in WWR, the annual thermal discomfort time ratios under all window orientations increase significantly, while the ability of thermochromic windows to improve thermal comfort decreases. To be specific, for normal windows in the east orientation, when WWR increases from 30% to 40%, 50%, and 60%, the annual thermal discomfort time ratios rise from 11.8% to 18.8%, 23.6%, and 28.0%, respectively, while those with thermochromic windows increase from 4.6% to 8.6%, 12.1%, and 15.9%, respectively, and the corresponding reductions in thermal discomfort duration by thermochromic windows are 60.9%, 54.4%, 48.9%, and 43.3%, respectively. For the south window, the annual thermal discomfort time ratios with normal windows are 8.7%, 17.1%, 23.8%, and 29.4%, respectively, while those with thermochromic windows are 1.5%, 5.6%, 9.5%, and 14.3%, respectively, and the corresponding reductions in thermal discomfort duration by thermochromic windows are 82.4%, 67.4%, 60.1%, and 51.2%, respectively. For the west window, the annual thermal discomfort time ratios with normal windows are 13.9%, 20.2%, 24.7%, and 28.8%, respectively, while those with thermochromic windows are 5.0%, 9.6%, 13.4%, and 17.9%, respectively, and the corresponding reductions in thermal discomfort duration by thermochromic windows are 63.7%, 52.5%, 45.5%, and 37.8%, respectively. For normal windows in the north orientation, the annual thermal discomfort time ratios are 4.0%, 9.5%, 13.7%, and 17.7%, respectively, while those with thermochromic windows are 0.1%, 2.7%, 5.3%, and 8.7%, respectively, and the corresponding reductions in thermal discomfort duration by thermochromic windows are 96.4%, 71.8%, 61.7%, and 50.6%, respectively.

Figure 9.

The thermal discomfort time ratios caused by solar radiation with normal windows and thermochromic windows under different WWRs.

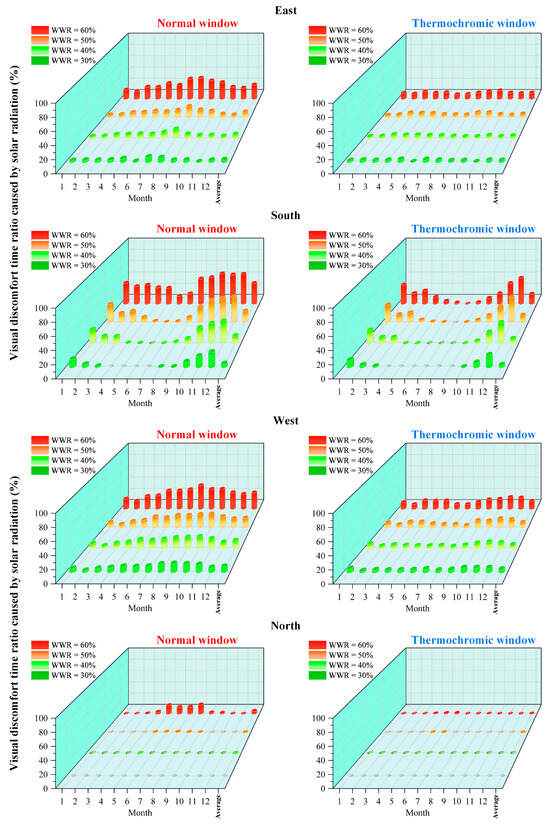

Figure 10 depicts the visual discomfort time ratios with two types of windows under different WWRs. It is obvious that with the increase in WWR, the annual visual discomfort time ratios in all orientations increase significantly, and the ability of thermochromic windows to improve visual comfort also increases. Specifically, for the east window, when WWR increases from 30% to 40%, 50%, and 60%, the annual visual discomfort time ratios with normal windows rise from 3.4% to 7.0%, 9.8%, and 24.7%, respectively, while those with thermochromic windows increase from 2.4% to 4.5%, 6.4%, and 10.9%, respectively, and the corresponding reductions in visual discomfort duration by thermochromic windows are 28.6%, 35.6%, 34.6%, and 55.8%, respectively. For the south window, the annual visual comfort time ratios with normal windows are 5.4%, 12.4%, 19.3%, and 36.1%, respectively, while those with thermochromic windows are 3.4%, 8.0%, 12.5%, and 17.2%, respectively, and the corresponding reductions in visual discomfort duration by thermochromic windows are 37.4%, 35.6%, 35.1%, and 52.4%, respectively. For the west window, the annual visual discomfort time ratios with normal windows are 8.5%, 13.0%, 16.2%, and 28.4%, respectively, while those with thermochromic windows are 4.7%, 6.6%, 9.4%, and 14.0%, respectively, and the corresponding reductions in visual discomfort duration by thermochromic windows are 45.4%, 48.7%, 42.1%, and 50.5%, respectively. For the north window, visual discomfort will only occur when WWR is 60%, and the annual visual discomfort time ratio with normal windows is 5.2%, while that with thermochromic windows is 0.3%, and the corresponding reduction in visual discomfort duration by thermochromic windows is 94.3%.

Figure 10.

The visual discomfort time ratios caused by solar radiation with normal windows and thermochromic windows under different WWRs.

3.3. Thermal Comfort and Daylight Performance of Thermochromic Windows Under Different Sill Heights

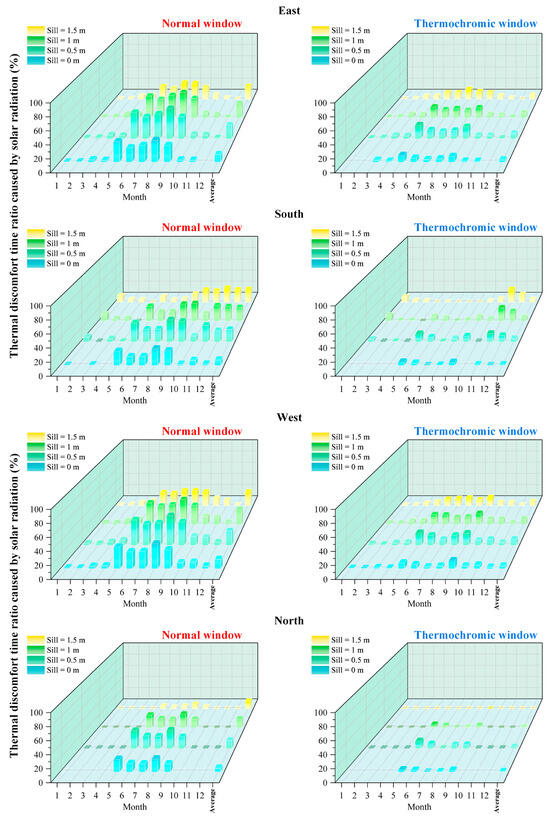

Figure 11 shows the solar-induced thermal discomfort time ratios with two types of windows under different sill heights when the WWR is fixed at 40%. It can be seen that as the sill height increases, the annual thermal discomfort time ratio caused by solar radiation under all window orientations first increases and then decreases, while the ability of thermochromic windows to improve thermal comfort decreases. Specifically, for normal windows in the east orientation, as the sill heights are 0, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 m, the annual thermal discomfort time ratios are 11.2%, 20.9%, 23.6%, and 22.5%, respectively, while those with thermochromic windows are 3.4%, 8.2%, 8.3%, and 7.2%, respectively, and the corresponding reductions in thermal discomfort duration by thermochromic windows are 70.0%, 60.9%, 64.7%, and 68.1%, respectively. For normal windows in the south orientation, the annual thermal discomfort time ratios are 8.0%, 19.2%, 22.3%, and 22.5%, respectively, while those with thermochromic windows are 1.2%, 5.1%, 5.9%, and 5.0%, respectively, and the corresponding reductions in thermal discomfort duration by thermochromic windows are 84.8%, 73.3%, 73.4%, and 77.8%, respectively. For the normal windows in the west orientation, the annual thermal discomfort time ratios are 13.8%, 22.3%, 24.5%, and 24.0%, respectively, while those with thermochromic windows are 4.0%, 9.2%, 8.9%, and 7.3%, respectively, and the corresponding reductions in thermal discomfort duration by thermochromic windows are 70.7%, 58.6%, 63.7%, and 69.6%, respectively. For the normal windows in the north orientation, the annual thermal discomfort time ratios are 5.7%, 12.6%, 14.3%, and 13.3%, respectively, while those with thermochromic windows are 0.7%, 2.6%, 1.1% and 0.0%, respectively, and the corresponding reductions in thermal discomfort duration by thermochromic windows are 87.5%, 79.1%, 92.2%, and 100.0%, respectively.

Figure 11.

The thermal discomfort time ratios caused by solar radiation with normal windows and thermochromic windows under different sill heights.

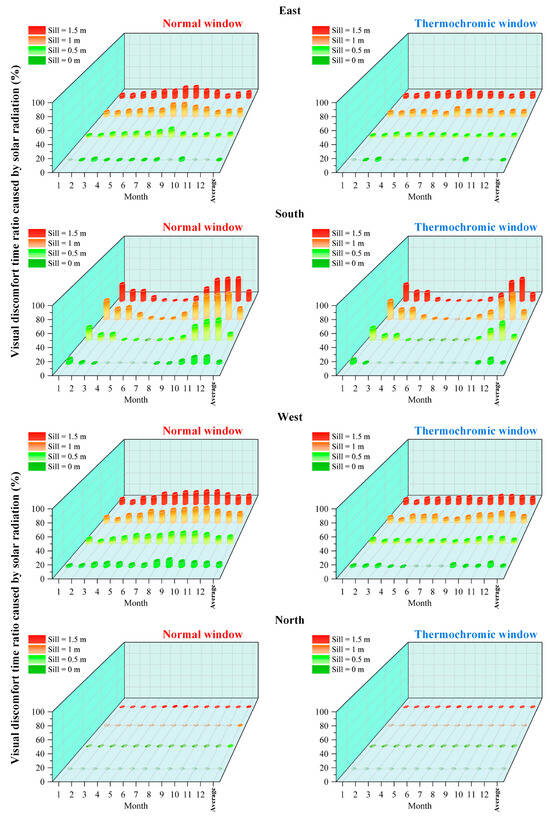

Figure 12 shows the visual discomfort time ratios with two types of windows under different sill heights when the WWR is fixed at 40%. It can be seen that as the sill height increases, the annual visual discomfort time ratio caused by solar radiation under all window orientations first increases and then decreases, while the ability of thermochromic windows to improve visual comfort decreases. Specifically, for normal windows in the east orientation, as the sill heights are 0, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 m, the annual thermal discomfort time ratios are 0.7%, 5.9%, 12.0%, and 11.0%, respectively, while those with thermochromic windows are 0.4%, 4.2%, 9.6%, and 9.2%, respectively, and the corresponding reductions in visual discomfort duration by thermochromic windows are 42.5%, 29.7%, 19.9%, and 15.9%, respectively. For normal windows in the south orientation, the annual thermal discomfort time ratios are 2.5%, 10.3%, 19.2%, and 17.4%, respectively, while those with thermochromic windows are 1.2%, 7.0%, 14.3%, and 13.2%, respectively, and the corresponding reductions in visual discomfort duration by thermochromic windows are 49.9%, 32.6%, 25.6%, and 24.2%, respectively. For normal windows in the west orientation, the annual thermal discomfort time ratios are 5.0%, 11.3%, 16.8%, and 15.7%, respectively, while those with thermochromic windows are 1.5%, 6.2%, 11.9%, and 12.0%, respectively, and the corresponding reductions in visual discomfort duration by thermochromic windows are 70.1%, 45.1%, 29.3%, and 23.4%, respectively. Meanwhile, no significant visual discomfort is observed for the north window.

Figure 12.

The visual discomfort time ratios caused by solar radiation with normal windows and thermochromic windows under different window-to-wall ratios.

3.4. Performance Comparison of Thermochromic Windows Under Different Window Geometry Parameters

Table 2 summarizes the reductions in annual thermal and visual discomfort time by thermochromic under different WWRs. The results indicate that solar-induced thermal discomfort is generally more pronounced than visual discomfort, and both types of discomfort increase with the increased WWR. As WWR increases, the thermal comfort performance of thermochromic windows (reduction percentage in thermal discomfort duration) decreases, whereas the visual comfort performance (reduction percentage in visual discomfort duration) improves. The above-stated results indicate that the performance of thermochromic windows should be evaluated with an appropriate WWR value. To be specific, if the WWR is too small, the window receives insufficient solar radiation, leading to an overestimation of the performance of thermochromic windows (a very low ratio of thermal or visual discomfort can be easily achieved with a low WWR, whether with thermochromic windows or not). Conversely, an excessively large WWR results in an underestimation of the performance of thermochromic windows (the thermal or visual discomfort time ratio may not be easy to maintain at a low level due to the overlarge window size). In this study, the proper WWR range is from 40% to 50%, where the thermal or visual discomfort is significant with normal windows, and meanwhile, the reduction in discomfort by thermochromic windows is significant, and the annual discomfort time ratio can be maintained below 15% or even 10%. Due to the low solar radiation received in the north direction, even with normal windows, north windows only cause little thermal or visual discomfort for indoor occupants, which cannot effectively reflect the solar modulation capability of thermochromic windows. Therefore, the north orientation is unsuitable for a performance evaluation of thermochromic windows.

Table 2.

The reductions in thermal discomfort and visual discomfort time by thermochromic windows under different WWRs.

Table 3 summarizes the reductions in annual thermal discomfort and visual discomfort time by thermochromic windows under different sill heights. As the sill height increases from 0 to 1.5 m, both thermal and visual discomfort time ratios first increase and then decrease, while the reduction in the thermal or visual discomfort duration by thermochromic windows gradually diminishes. The above-stated results also indicate that the performance of thermochromic windows should be evaluated with an appropriate sill height. In this study, the proper sill height range is from 0.5 to 1.0 m, where the thermal or visual discomfort is significant with normal windows, and meanwhile, the reduction in discomfort by thermochromic windows is significant, and the annual discomfort time ratio can be maintained below 15% or even 10%.

Table 3.

The reductions in thermal discomfort and visual discomfort time by thermochromic windows under different sill heights.

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages of This Work

- (1)

- This study comprehensively investigates thermal and visual discomfort induced by solar radiation with seasonal comfort thresholds and illuminance limits, thereby enabling more accurate performance assessments of the impact of window geometry parameters on thermal and daylight environments indoors.

- (2)

- This study investigates the changes in the solar thermal discomfort and excessive daylight durations of thermochromic windows under different window geometry parameters. This study aids the determination of the ability of thermochromic windows to improve indoor environments and the evaluation of their applicability across various window designs.

- (3)

- This study recommends the window geometry parameters for evaluating the thermal and visual comfort performance of thermochromic windows, reducing the evaluation deviations caused by improperly selected window geometry parameters.

4.2. Limitations

- (1)

- Herein, only the discomfort caused to indoor occupants when solar radiation intensity and daylight illuminance exceed threshold levels was examined, without consideration of the cumulative harm of prolonged exposure to solar radiation.

- (2)

- This study was conducted with one climate type, without further systematic investigation into other climate zones (such as cold, arid, or extreme environments). Future research should be conducted under diverse climatic conditions to ensure broader applicability.

- (3)

- This study primarily focuses on indoor environments, without systematically assessing building energy consumption, which is another large topic and may be investigated in the future.

- (4)

- While thermochromic windows demonstrate clear benefits in enhancing indoor thermal and visual comfort, currently, their relatively high manufacturing costs [57,58] may constrain large-scale applications, especially when compared to the existing low-e or spectrally selective coatings with lower costs. Therefore, future studies should aim to reduce the manufacturing cost of thermochromic windows and further lower the life-cycle cost by including the energy saving benefits, to support their practical implementation.

5. Conclusions

The following conclusions are drawn in this study:

- (1)

- Thermochromic windows exhibit varying reductions in the durations of solar-induced thermal and visual discomfort under different orientations. For the east, south, west, and north orientations, thermochromic windows lower the annual thermal discomfort durations by 60.9%, 82.4%, 63.7%, and 96.4%, respectively. In the east, south, and west orientations, thermochromic windows can reduce the annual visual discomfort durations by 28.6%, 37.4%, and 45.4%, respectively, while in the north orientation, no significant visual discomfort is observed, whether with normal or thermochromic windows.

- (2)

- Increasing WWR weakens the ability of thermochromic windows to improve thermal comfort but enhances the ability to improve visual comfort. When thermochromic windows are in the east, south, west, and north orientations, as WWR increases from 30% to 60%, the reductions in thermal discomfort duration decrease from 60.9%, 82.4%, and 63.7% to 43.3%, 51.2%, and 37.8%, respectively, while the reductions in visual discomfort duration by thermochromic windows increase from 28.6%, 35.6%, and 42.1% to 55.8%, 52.4%, and 50.5%, respectively.

- (3)

- Sill height also exerts significant effects on thermochromic windows. When thermochromic windows are in the east, south, west, and north orientations, as the sill height increases from 0 to 1.5 m, the reductions in thermal discomfort duration increase from 60.9%, 73.4%, and 63.7% to 70.0%, 91.6%, and 90.7%, respectively, and the reductions in visual discomfort duration decrease from 42.5%, 49.9%, and 70.1% to 15.9%, 24.2%, and 23.4%, respectively.

- (4)

- To ensure the accurate evaluation of thermochromic windows’ comfort performance, the window geometry parameters should be maintained within proper ranges. In this study, the proper WWR range is from 40% to 50%, and the sill height range is from 0.5 to 1 m, when the thermal and visual discomfort is obvious without thermochromic windows, and meanwhile, the discomfort elimination by thermochromic windows is significant and thermochromic windows can keep the annual discomfort time below 15% or even 10%. In addition, the north orientation should be avoided.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings15213963/s1, Table S1. The summary of properties of thermochromic windows and normal windows. Table S2. The internal loads of the building, including indoor lighting, equipment, and occupants. Table S3. The input parameters of the improved HNU Solar model. Figure S1. Auxiliary points: (a) human body auxiliary points and (b) window auxiliary points. Figure S2. The parameters of the virtual body shadow algorithm for calculating direct solar radiation on human bodies indoors. Figure S3. The virtual body shadow algorithm: (a) When the virtual body shadow is entirely in the reflected area, (b) When the virtual body shadow is partly within the reflected area, (c) When the top of the virtual body shadow is in the reflected area; (d) When the top of the virtual body shadow is beyond the reflected area, (e) When the top of the virtual body shadow does not reach the reflected area, and (f) When the window-toward body side is not in the reflected area and far away from the window. Figure S4. The improved HNU Solar model’s diffuse and reflected diffuse solar radiation calculation (originally from reference [56]): (a) the vertical view, (b) the horizontal view, (c) the non-uniform sky (originally from reference [58]), (d,e) the angles for calculating transmitted diffuse radiation intensity, and (f) the sky view factor of the feet of human body. Figure S5. The parameters of the equivalent window algorithm for calculating reflected direct solar radiation on indoor human bodies. Figure S6. The parameters for calculating reflected diffuse solar radiation on indoor human bodies; [43,46,47,49,50,51,52,53].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y. and Y.H.; methodology, C.Y. and Y.H.; investigation, C.Y., Y.H., Y.C. and N.L.; data curation, C.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.H.; visualization, C.Y. and Y.C.; funding acquisition, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52308092, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China, grant number 531118010826.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WWR | Window-to-wall ratio |

| ΔMRT | The increase in mean radiant temperature of indoor occupants caused by solar radiation |

| U-values | The heat transfer coefficients |

| SHGC | The solar heat gain coefficient |

| VT | The visible light transmittance |

| Pthermal_discomfort | The thermal discomfort time ratio caused by solar radiation |

| tthermal_discomfort | The thermal discomfort caused by solar radiation |

| toccupied | The total occupied hours |

| Pthermal_reduction | The reduction ratio of thermal discomfort duration by thermochromic window |

| tthermal_discomfort_Normal | The thermal discomfort duration caused by solar radiation with normal windows |

| tthermal_discomfort_TC | The thermal discomfort duration caused by solar radiation with thermochromic windows |

| Pvisual_discomfort | The visual discomfort time ratio caused by solar radiation |

| tvisual_discomfort | The visual discomfort caused by solar radiation |

| Pvisual_reduction | The reduction ratio of visual discomfort duration by thermochromic windows |

| tvisuall_discomfort_Normal | The visual discomfort duration caused by solar radiation with normal windows |

| tvisuall_discomfort_TC | The visual discomfort duration caused by solar radiation with thermochromic windows |

References

- Wang, L.; Greenberg, S. Window operation and impacts on building energy consumption. Energy Build. 2015, 92, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A. Diffuse transmission dominant smart and advanced windows for less energy-hungry building: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 64, 105604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghoul, S.K.; Rijabo, H.G.; Mashena, M.E. Energy consumption in buildings: A correlation for the influence of window to wall ratio and window orientation in Tripoli, Libya. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 11, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Torres, M.; Pérez-Lombard, L.; Coronel, J.F.; Maestre, I.R.; Yan, D. A review on buildings energy information: Trends, end-uses, fuels and drivers. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, N.; He, Y.; Pan, J.; Chen, Y. Quantifying the effects of indoor non-uniform solar radiation on human thermal comfort and work performance in warm season. Energy Build. 2024, 306, 113962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, J. A spectrally-resolved method for evaluating the solar effect on user thermal comfort in the near-window zone. Build. Environ. 2021, 202, 108044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamporn, N.; Chaiyapinunt, S. An Investigation on the Human Thermal Comfort from a Glass Window. Eng. J. 2014, 18, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Wei, S.; Meng, L.; Cao, G. Illumination distribution and daylight glare evaluation within different windows for comfortable lighting. Results Opt. 2021, 3, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Kunwar, N.; Cetin, K.; O’Neill, Z. A critical review of fenestration/window system design methods for high performance buildings. Energy Build. 2021, 248, 111184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goia, F. Search for the optimal window-to-wall ratio in office buildings in different European climates and the implications on total energy saving potential. Sol. Energy 2016, 132, 467–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Li, Q.; Xie, J.; Zhao, M.; Liu, J. Optimization of window-to-wall ratio with sunshades in China low latitude region considering daylighting and energy saving requirements. Appl. Energy 2019, 233, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwetaishi, M. Investigation of the use of external insulation materials in domestic buildings in hot regions considering various window-to-wall ratios (WWR). Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 74, 106900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahtafti, R.; Mahdavinejad, M. Window geometry impact on a room’s wind comfort. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 2381–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangkuto, R.A.; Rohmah, M.; Asri, A.D. Design optimisation for window size, orientation, and wall reflectance with regard to various daylight metrics and lighting energy demand: A case study of buildings in the tropics. Appl. Energy 2016, 164, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuce, E.; Riffat, S.B. A state-of-the-art review on innovative glazing technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorooshnia, E.; Rashidi, M.; Rahnamayiezekavat, P.; Mahmoudkelayeh, S.; Pourvaziri, M.; Kamranfar, S.; Gheibi, M.; Samali, B.; Moezzi, R. A novel approach for optimized design of low-E windows and visual comfort for residential spaces. Energy Built Environ. 2025, 6, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur-E-Alam, M.; Vasiliev, M.; Yap, B.K.; Islam, M.A.; Fouad, Y.; Kiong, T.S. Design, fabrication, and physical properties analysis of laminated Low-E coated glass for retrofit window solutions. Energy Build. 2024, 318, 114427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, L.M. Evaluating UV-Protective Low-Emissivity Window Films: Implications for Thermal and Visual Comfort in Luminous Office Buildings. AUIQ Complement. Biol. Syst. 2024, 1, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Xiang, C. Smart solar windows for an adaptive future: A comprehensive review of performance, methods and applications. Energy Build. 2025, 346, 116227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.N.; Mohd Abdah, M.A.A.; Numan, A.; Moreno-Rangel, A.; Radwan, A.; Khalid, M. Smart window technology and its potential for net-zero buildings: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 181, 113355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, H.; Gomes, M.G.; Moret Rodrigues, A.; Pereira, J. Thermal and visual comfort, energy use and environmental performance of glazing systems with solar control films. Build. Environ. 2020, 168, 106474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Yang, H.; Dong, K. Energy and Thermal Comfort Performance of Vacuum Glazing-Based Building Envelope Retrofit in Subtropical Climate: A Case Study. Buildings 2025, 15, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Es-sakali, N.; Idrissi Kaitouni, S.; Ait Laasri, I.; Oualid Mghazli, M.; Cherkaoui, M.; Pfafferott, J. Static and dynamic glazing integration for enhanced building efficiency and indoor comfort with thermochromic and electrochromic windows. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 52, 102681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, M. Active dynamic windows for buildings: A review. Renew. Energy 2018, 119, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Sun, H.; Duan, M.; Mao, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Lin, B. Applications of thermochromic and electrochromic smart windows: Materials to buildings. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Li, W.; Fu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, K.; Wang, H. Dual-band electrochromic smart windows towards building energy conservation. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2023, 256, 112320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Long, Y.; Gao, Y. Thermochromic Energy Efficient Windows: Fundamentals, Recent Advances, and Perspectives. Chem. Rev 2023, 123, 7025–7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Wang, J.; Jiang, L. Recent advances in photochromic smart windows based on inorganic materials. Responsive Mater. 2024, 2, e20240001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburas, M.; Soebarto, V.; Williamson, T.; Liang, R.; Ebendorff-Heidepriem, H.; Wu, Y. Thermochromic smart window technologies for building application: A review. Appl. Energy 2019, 255, 113522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijewardane, S.; Santamouris, M. Smart glazing systems: An industrial outlook. Sol. Compass 2025, 14, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Araujo, A.C.; Salomão, R.; Berardi, U.; Dornelles, K.A. Thermochromic materials for building Applications: Overview through a bibliometric analysis. Sol. Energy 2025, 293, 113491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Chen, S.; Huang, R.; Huang, J.; Li, J.; Shi, R.; Niu, S.; Amini, A.; Cheng, C. Vanadium dioxide for thermochromic smart windows in ambient conditions. Mater. Today Energy 2021, 21, 100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, I.; Campano, M.Á.; Molina, J.F. Window design in architecture: Analysis of energy savings for lighting and visual comfort in residential spaces. Appl. Energy 2016, 168, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; He, Y.; Li, N. Evaluating annual thermal discomfort time ratio of indoor occupants caused by solar radiation using a novel model. Archit. Intell. 2024, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafian, T.; Moazzen, N. The impact of glazing ratio and window configuration on occupants’ comfort and energy demand: The case study of a school building in Eskisehir, Turkey. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 47, 101483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Yang, L.; Bai, L. Field experimental study of the impact of solar radiation on the thermal comfort of occupants near the glazing area in an office building. Energy Build. 2025, 332, 115422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Bai, L.; Yang, L. Analysis of the long-term effects of solar radiation on the indoor thermal comfort in office buildings. Energy 2022, 247, 123499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Chen, X.-N.; Xu, B.; Pei, G. Investigation of occupied/unoccupied period on thermal comfort in Guangzhou: Challenges and opportunities of public buildings with high window-wall ratio. Energy 2022, 244, 123186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhai, X. Energy saving performance of thermochromic coatings with different colors for buildings. Energy Build. 2020, 215, 109920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wu, Y. Evaluating coloured thermochromic windows for energy efficiency and visual comfort in buildings. Adv. Appl. Energy 2025, 18, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, V.; Evola, G.; Marletta, L. Thermal and visual performance of real and theoretical thermochromic glazing solutions for office buildings. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 149, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, K.M.; Huang, B.; Tso, C.Y. Near-Infrared-Activated Thermochromic Perovskite Smart Windows. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2106090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; He, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, N.; Na, E.; Jia, Y. Daylight and energy performance optimization of thermochromic windows based on solar-related thermal comfort. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 112, 113655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Cao, C.; Huang, A.; He, P.; Cao, X. Flexible tri-state-regulated thermochromic smart window based on WxV1-xO2/paraffin/PVA composite film. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curcija, D.C.; Zhu, L.; Czarnecki, S.; Mitchell, R.D.; Kohler, C.; Vidanovic, S.V.; Huizenga, C. Berkeley Lab Window; Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (LBNL): Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015.

- EnergyPlus 22.1.0. 2022. Available online: https://energyplus.net/ (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Xiang, X.; He, Y.; Li, N.; Chen, W.; Zhang, W. A novel method for calculating solar radiation on indoor human body under different weather conditions. Build. Environ. 2024, 254, 111397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Jiang, Y.; He, Y.; Li, N.; Shen, X.; Han, Y.; Han, X.; Lu, N. An experimental study on the threshold of indoor solar radiation intensity for thermal comfort and work performance in warm season. Build. Environ. 2025, 272, 112703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prototype Building Models. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/buildings/new-construction-commercial-reference-buildings (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Steven, M.D.; Unsworth, M. Standard distributions of clear sky radiance. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1977, 103, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, S.; Tso, C.Y. A novel solar-based human-centered framework to evaluate comfort-energy performance of thermochromic smart windows with advanced optical regulation. Energy Build. 2023, 278, 112638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-2017; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineering: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017.

- Nabavi-Pelesaraei, A.; Rafiee, S.; Hosseini-Fashami, F.; Chau, K.-w. Artificial neural networks and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system in energy modeling of agricultural products. In Predictive Modelling for Energy Management and Power Systems Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 299–334. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y. Study on Indoor Human Thermal Comfort and Work Performance with the Effect of Solar Radiation Heat. Master′s Thesis, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan, China, 2025. (In Chinese, Expected to Be Published in 2026). [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Y.; Luo, T. Investigation of visual comfort metrics from subjective responses in China: A study in offices with daylight. Build. Environ. 2017, 123, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, J.Y. Luminance and vertical eye illuminance thresholds for occupants’ visual comfort in daylit office environments. Build. Environ. 2019, 148, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K.; Xue, C.; Wu, J.; Wen, W. Assessment of Gel-Based Thermochromic Glazing for Energy Efficiency in Architectural Applications. Materials 2024, 17, 4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smart Windows Market Size & Outlook, 2024–2032. Available online: https://straitsresearch.com/report/smart-windows-market (accessed on 17 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).