Abstract

This article investigates the structural resistance of thin-walled steel sections classified as Classes 1 to 4 under Eurocode 3. The study focuses on flexural capacity, and takes into consideration the effects of local buckling and the bimoment. Although Class 1 and 2 sections can develop complete plastic resistance, Class 3 sections are limited to elastic behavior prior to local instability. For Class 4 sections, effective width methods are employed to account for the reduction in strength due to early local buckling. Based on Eurocode formulations, these approaches are extended to incorporate the influence of the bimoment, which is significant in thin-walled open sections under non-uniform torsion. A comparative analysis between analytical models and numerical simulations is presented, with an emphasis on how the bimoment alters stress distributions and reduces the effective widths of slender plates. The results underscore the necessity of including these effects in the structural design of thin-walled members, particularly for open profiles subjected to bending and warping.

1. Introduction

The classification of cross sections according to structural codes, such as Eurocode 3 [1] and equivalent standards, not only defines design criteria but is also an important factor in accurately estimating the safety, efficiency, and durability of steel structures. Beyond simple categorization (Classes 1 to 4), there has been an increase over recent years in research on analyzing the boundaries of these classes, the transitions between them, and the effects of real-world conditions such as elevated temperatures, thin geometries, and the presence of imperfections takes into account the influence of geometrical deviations from tolerances and residual stresses which are always present in real structures. It is clearly stated in the brand new “Eurocode EN 1993-1-14:2025 Eurocode 3—Design of steel structures—Part 1-14: Design assisted by finite element analysis” [2], which provides guidance on applying numerical methods in the elastic and plastic design of steel structures.

In this way, for example, Agüero et al. [3] present a comprehensive study investigating 18 steel and aluminum cross sections of various shapes, including I, T, and Z channels and asymmetric sections. For each shape, they calculate three types of section plastic moduli and the corresponding plastic strengths under arbitrary combinations of internal forces.

Furthermore, consideration of the bimoment has emerged as a critical factor in predicting the behavior of thin sections subjected to non-uniform torsion. It is well established that the interaction between torsion, bending, and bimoment significantly affects the load-bearing capacity of the metal (steel and aluminum) thin-walled sections, in both the elastic and plastic ranges. For further guidance, see, e.g., new “Eurocode EN 1993-1-1. Design of Steel Structures: General rules and rules for buildings” [1]. Glauz describes methods for determining the plastic bimoment in cold-formed open sections, with the aim of improving the prediction of load-bearing capacity under torsion and bending conditions.

The present work is situated within this context of technical and practical refinement, and seeks to present recommended design procedures for Classes 1 to 4 according to the codes, taking into account the effects of the bimoment, and to compare the results of these procedures with recent results in the literature.

The article is divided into two main parts, based on the classification of cross sections according to structural codes (such as Eurocode 3 [1] or equivalent standards). This division reflects the need to apply different design criteria depending on the plastic or elastic behavior of the sections, as well as the influence of local effects such as buckling.

- Part One: Resistance of Class 1, 2, and 3 sections

The first part focuses on sections of Classes 1 to 3, which, according to design standards, are capable of developing different degrees of stress redistribution:

- Class 1: Fully plastic sections with the capacity to form plastic hinges, allowing for moment redistribution.

- Class 2: Sections that can reach full plastic resistance but with limited redistribution capacity.

- Class 3: Sections that must be verified using elastic stress limits, as local buckling prevents plastic stress development.

This part of the article examines the design and verification criteria for these section classes under axial force, simple bending, and combined bending and axial force. Practical examples are presented to illustrate how to calculate the ultimate resistance and the interaction of internal forces according to design standards. These examples show how the class of a section affects its load-bearing capacity, and how this is influenced by the elastic or plastic behavior of the material and the section geometry.

- Part Two: Resistance of Class 4 Sections

The second part is devoted exclusively to Class 4 sections, which exhibit more complex behavior due to the slenderness of their plate elements. In these sections, local buckling occurs before the material reaches its yield strength, requiring the use of effective section properties. This part presents a methodology for determining the effective cross section, following the procedures established in design codes (e.g., EN 1993-1-5 [4]), by accounting for reductions due to local buckling in webs and flanges. A limited plastification and local stability analysis is also carried out.

Representative examples are provided to demonstrate the complete calculation process of the effective section and its design resistance under bending, compression, and combined loading. These cases typically involve thin-walled or cold-formed profiles, which are commonly used in lightweight steel structures.

This paper seeks to present recommended design procedures for Classes 1 to 4 according to existing codes (such as Eurocode 3 [1] and EN 1993-1-5 [4]), taking into consideration the effects of the bimoment, and to compare these procedures with recent results in the literature. This will enable identification of when standard methods may be conservative or insufficient, especially for Class 4 sections subjected to torsion, bending, and complex load combinations. The study also aims to offer applied examples that include these scenarios, so that engineers have more precise criteria for contemporary structural design.

2. Resistance of Class 1, 2 and 3 Sections

The structural behavior of thin-walled sections under warping torsion requires an understanding of both elastic and plastic responses. Elastic theory provides the foundation for analyzing thin-walled elements, thereby enabling the calculation of the warping coordinate and bimoment. These parameters are critical in assessing the torsional stresses arising from non-uniform twists and warping constraints. Engineers can evaluate stress distributions and deformations through the elastic formulation by solving equilibrium equations to ensure structural safety under elastic conditions.

As the applied load is increased, sections may undergo plastification, requiring more advanced methods to assess the plastic bimoment. The static (lower-bound) theorem becomes a key tool in this context. According to this theorem, if equilibrium and plastic admissibility conditions are met, the plastification factor ξ is less than or equal to the ultimate load multiplier. This factor is used to scale the internal forces, namely the axial force (NEd), bending moments (My,Ed, Mz,Ed), bimoment (BEd), shear forces (Vy,Ed, Vz,Ed), torsional moment (Tt,Ed), and warping torsion (Tw,Ed).

In torsion-dominated problems, a plasticity analysis primarily focuses on the components ξBEd, ξTt,Ed, and ξTw,Ed, and other forces are neglected to isolate the plastic contribution of the bimoment. This targeted formulation simplifies the analysis while capturing the key effects of plastification under torsional loading. By bridging the elastic and plastic regimes, these methods provide engineers with a comprehensive framework for analyzing the structural response of complex thin-walled sections.

This paper introduces two methods for determining the plastic bimoment of thin-walled sections, as follows:

- Method 1: This involves determining the plastic shear center. The procedure follows Glauz [3], wherein the sign of the normalized plastic warping coordinate ωnp corresponds to the sign of the stress. The position of the plastic shear center ensures axial and flexural equilibrium by balancing areas that are under compression and tension.

- Method 2: Based on the approach of Agüero [3], this method employs linear programming to maximize the plastic bimoment. The optimization process assumes a unit warping pattern about the elastic shear center, subject to constraints that ensure that N = My = Mz = 0 and that the stresses remain within the yield limits (−fy ≤ σ ≤ fy).

Numerical examples are given for different section types, including monosymmetric I-sections, channel sections, and asymmetric profiles, with strong agreement between both methods, thus validating their use in structural design.

2.1. Analytical Method

2.1.1. Elastic Theory

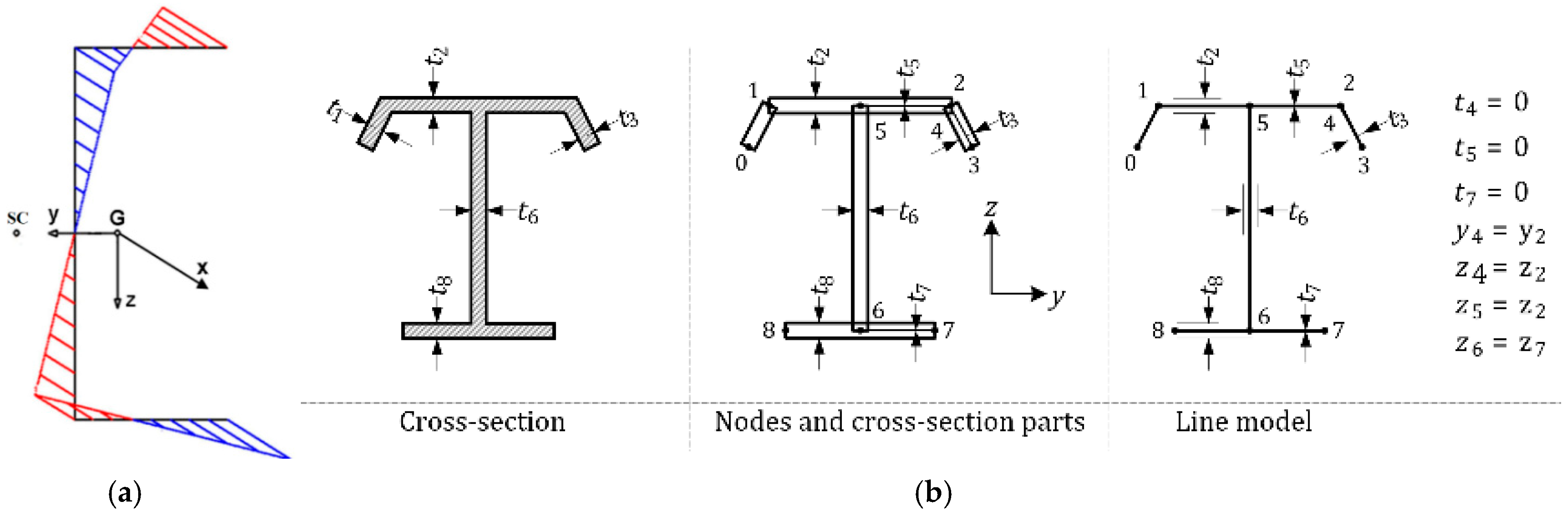

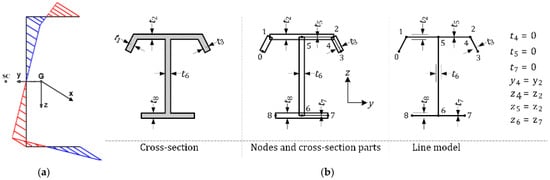

The classical approach to determining section properties is presented below, based on sectorial coordinates using centroidal coordinates yc and zc, as shown in Figure 1a,b.

Figure 1.

(a) Warping coordinates for the channel section, shear center and centroid position; (b) a general thin-walled section.

ωc,0 can be chosen arbitrarily, and is typically taken as zero, giving:

ωs,0 can also be chosen arbitrarily, and is typically taken as zero, giving:

From a computational perspective, it is convenient to use any arbitrary starting coordinate system (y, z, ω) and the parallel axis theorem to obtain the centroidal properties. For sectorial coordinates with respect to any pole, we have:

The normalized sectorial coordinates about the shear center (sc) can then be determined using

2.1.2. Plastic Theory

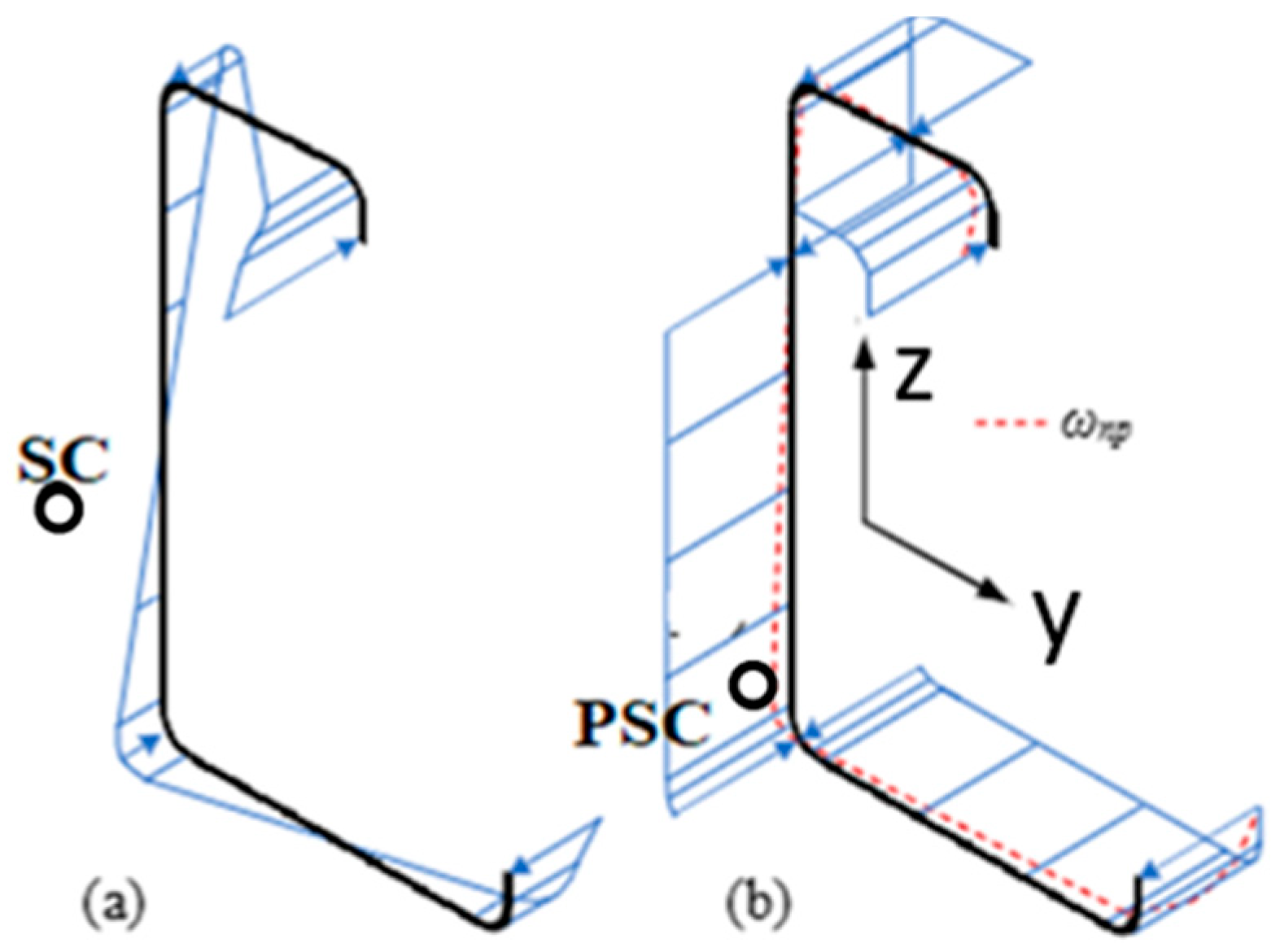

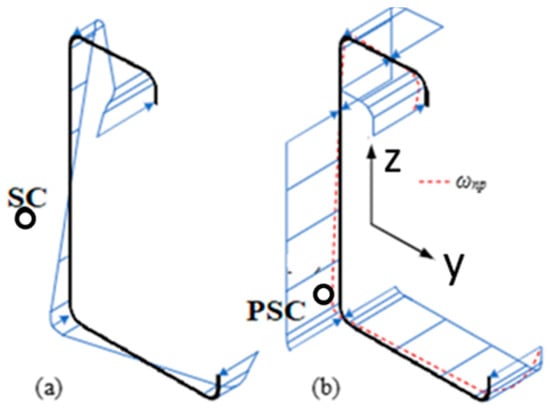

In Method 1, the classical approach by Glauz is used, where the sign of ωnp corresponds to the sign of σ, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(a) Elastic stress distribution and location of elastic shear center SC; (b) plastic bimoment stress distribution, location of plastic shear center PSC and ωnp distribution.

ωsp,median is determined such that there are equal areas of positive and negative stress (axial equilibrium). This case is similar to locating the plastic neutral axis for flexure resulting in equal areas of positive and negative stress.

The plastic shear center is positioned where the bimoment yield stresses associated with the sign of ωnp result in flexural equilibrium.

If the bimoment yield stresses are determined by other means, such that the net axial force and moments are zero, the location of the plastic shear center does not need to be determined.

Most of the terms above drop out, since ωsp,median is multiplied by (22), zpsc is multiplied by (24), and ypsc is multiplied by (23).

In the second method developed by Agüero [5], the bimoment can be obtained using linear programming, which involves maximizing the bimoment by using as a pole the elastic shear center that satisfies the constraints N = My = Mz = 0 and the stress at each point, constrained to −fy < σ < fy.

The plastic bimoment section modulus can then be obtained as:

2.2. Bimoment: Numerical Examples

The following numerical examples were checked with the software by Agüero [5].

2.2.1. Channel Section

The channel section has dimensions of b = 75 mm, h = 187 mm, tf = 13 mm and tw = 10 mm, specified along its middle line, as shown in Figure 3.

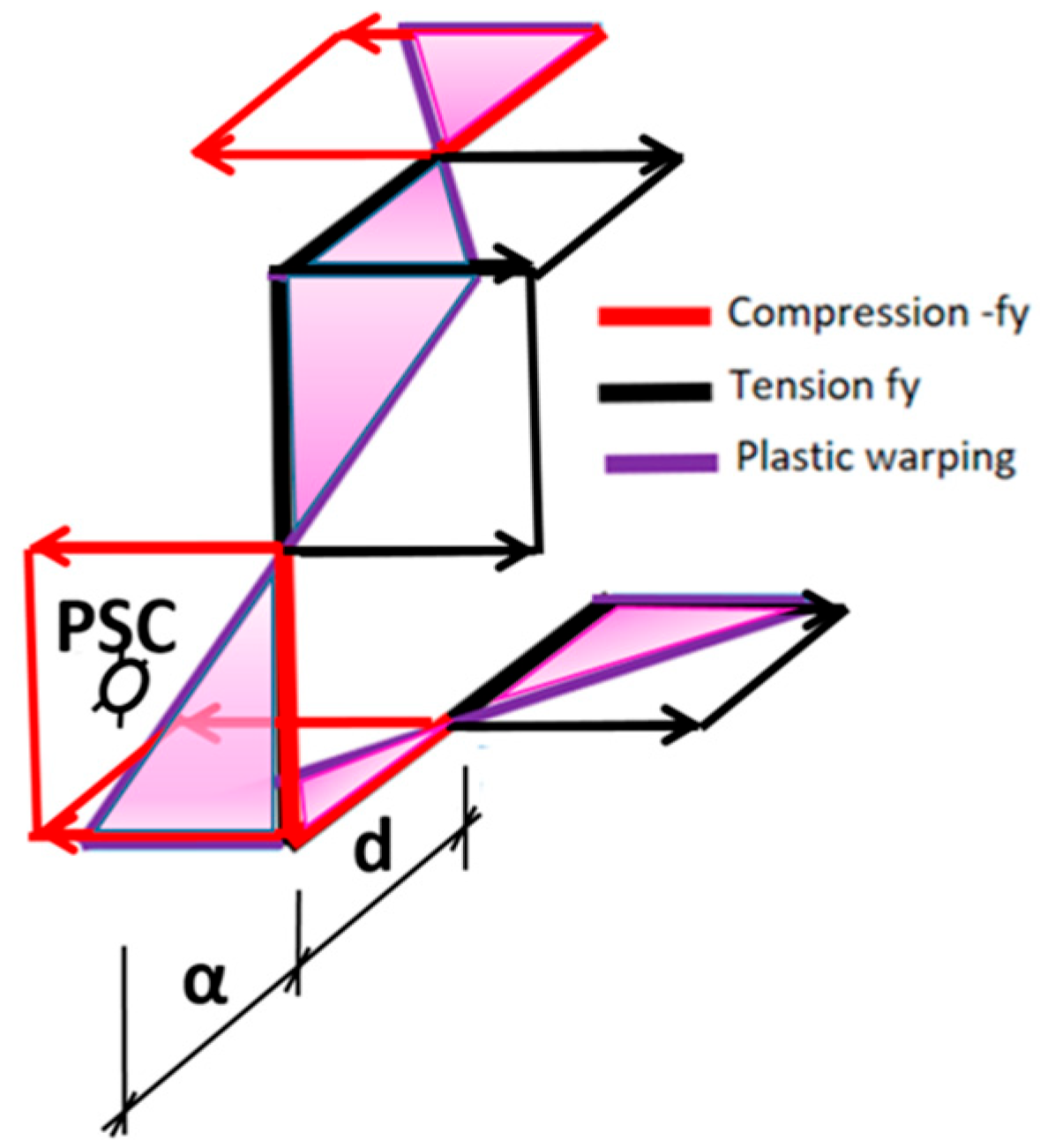

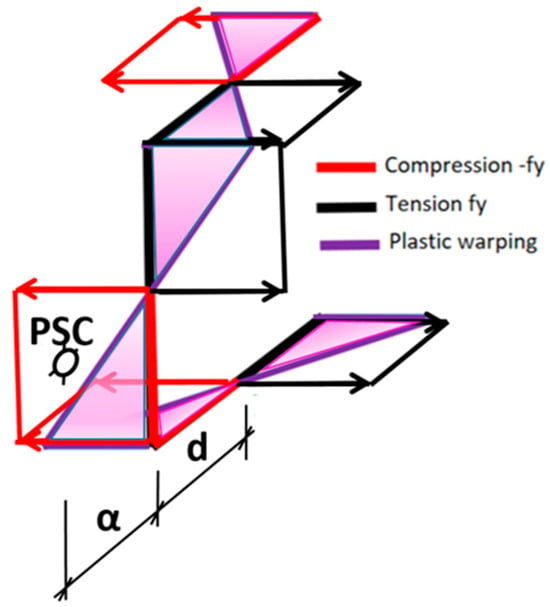

Figure 3.

Channel section showing plastic direct stress σ distribution, location of PSC and shape of distributions ωsp and σwp.

The traditional approach, Method 1, which is based on sectorial coordinates about the plastic shear center and precise location of the stress reversals, gives a value of Zw = 591.098 cm4, where ypsc = 38.642 mm and zpsc = 0 mm (representing the distance between the plastic shear center and the centroid).

To obtain the parts of the bottom flange under compression and the top flange under tension (marked as d in Figure 3), the condition My = 0 is used (31).

Taking into account the fact that a shift in the plastic normal stresses from compression to tension takes place where the warping is zero, Equation (32) gives the distance of the plastic shear center to the web:

For Method 2, with 10 fibers per element, we have values of Wpl,w = Zw = 594.874 cm4, and with 20 fibers per element, Zw = 591.517 cm4. The results tend to converge to a precise solution with more fibers. From the equation given by Agüero (Table 14 in [3]), we have values of Zw = 591.098 cm4, Ysc,el = 47.559 mm for the distance between the elastic shear center and the centroid. To benchmark these results, the calculated value of Wplw = 2878 cm4 was compared with those reported by Baláž [6] and Beyer [7] for a UPE360 section (Table 1), as well as with the experimental findings of Strelbickaja [8,9].

Table 1.

Comparison of results.

2.2.2. Mono-Symmetrical I-Shaped Section

Trahair [10] pointed out that the plastic bimoment did not depend on the pole position when computing the warping coordinate for this type of section.

The section has dimensions of bu = 100 mm, bl = 60 mm, h = 187 mm, tf = 13 mm and tw = 10 mm, specified along its middle line. The distance d from the plastic shear center to the lower part of the upper flange can be obtained by applying the condition Mz = 0, resulting in Equation (33):

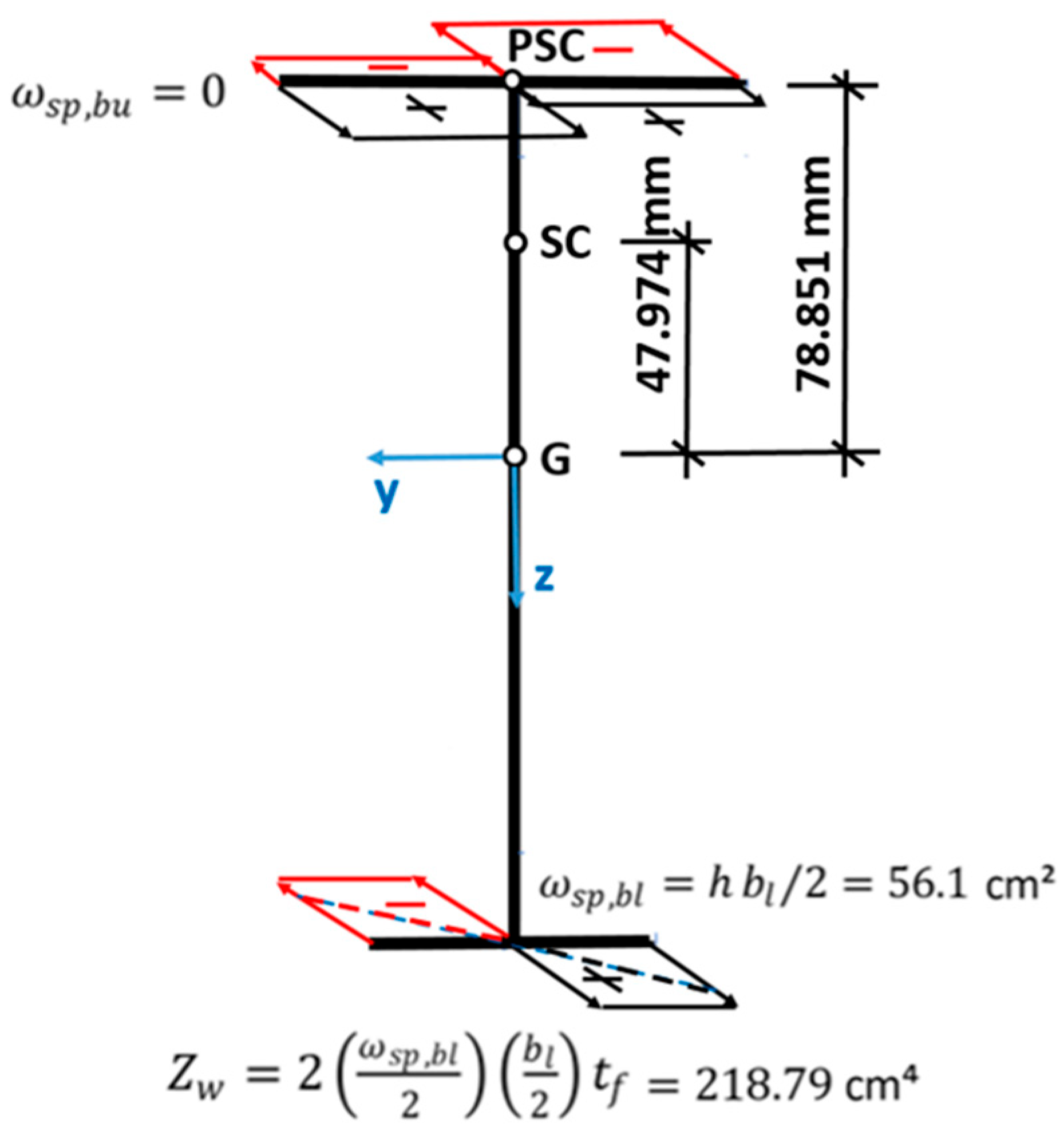

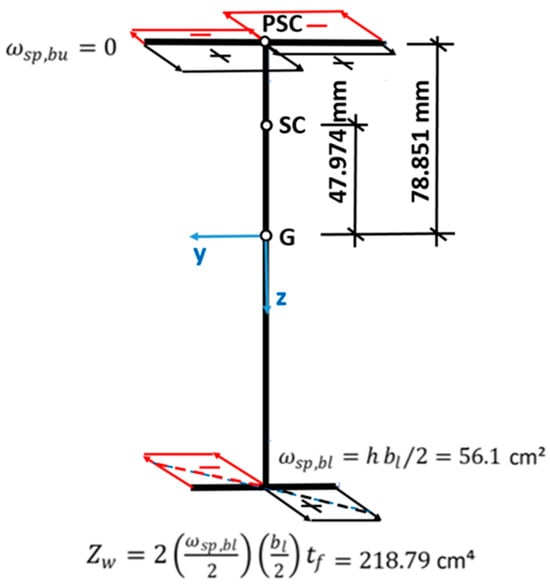

The plastic shear center lies within the thickness of the larger flange, zpsc = 78.851 mm. The tension and compression stresses are apportioned across the thickness of the larger flange to give equilibrium, but make a negligible contribution to the plastic bimoment. Due to symmetry, the normalized plastic sectorial coordinates and plastic bimoment section modulus can easily be determined as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Diagram of the mono-symmetrical I-shaped section.

Using Method 2, the same value is obtained from the equation given by Agüero (Table 13 in [3]) with 10 fibers per element (Wpl,w = Zw = 218.79 cm4). The distance between the elastic shear center and centroid is Zsc,el = 47.974 mm.

2.2.3. Non-Symmetrical Section

In this case, we analyze a channel section with different top and bottom flange widths. The section has dimensions of bu = 75 mm, bl = 50 mm, h = 187 mm, tf = 13 mm and tw = 10 mm, specified along its middle line. The traditional approach using sectorial coordinates about the plastic shear center and precisely locating the stress reversals gives Zw = 303.889 cm4, where ypsc = 15.118 mm and zpsc = 84.795 mm, as the distance between the plastic shear center and the centroid.

Using Method 2, with 10 fibers per element, we obtain Wpl,w = Zw = 303.875 cm4. Ysc,el = 35.102 mm, Zsc,el = 31.259 mm, as the distance between the elastic shear center and the centroid.

The plastic shear center approach can be applied to highly non-symmetric sections without fundamental limitations, as demonstrated by Glauz in previous studies. However, the computation may require additional iterations and slightly longer processing time for such sections to ensure accurate convergence. Careful implementation is recommended to maintain numerical reliability, particularly for complex geometries or slender elements.

3. Resistance of Class 4 Sections

Class 4 sections are structural elements characterized by thin-walled components that are prone to local buckling under compressive stresses. Unlike lower-class sections, their load-bearing capacity and stability depend significantly on their effective width, which accounts for their post-buckling behavior.

The effective width is critical when analyzing and designing these sections, as it reflects the usable portion of a plate after accounting for reductions due to buckling. The idea of effective width was initially explored in the works of Theodore von Kármán, a pioneer in aerodynamics and structural mechanics. His contributions laid the foundation for post-buckling analysis, as they offered insights into how plates behave under stress redistribution after buckling. Winter further developed this theory by proposing simplified methods to estimate the effective width in practical applications.

The current Eurocode standards, particularly Eurocode 3 [1,4] for design steel structures, incorporate these advancements and provide comprehensive guidelines for calculating the effective width of Class 4 sections, including factors such as slenderness ratios, buckling coefficients, and material properties. By leveraging these principles, engineers can ensure that Class 4 sections meet safety and performance criteria, thereby facilitating efficient and reliable structural designs for modern applications.

This paper fills a gap in existing research on how to deal with bimoments in Class 4 sections.

3.1. Analytical Method

In this approach, the elastic stresses are first computed:

Once the stresses have been obtained, the effective width of each plate is calculated. The effective width depends on the axial force N, bending moments My, Mz and bimoment B combination according to EN 1993-1-1:2022 [1], EN 1993-1-5:2006 [4] and Lee [11].

Two methods can be used to compute the stresses:

- Method 1: Consider each internal force independently and compute its stresses with the effective section.

- Method 2: Consider all the internal forces simultaneously and compute the stress distribution altogether, and the effective width related to those stresses.

Taking into account the effective width, the effective section properties can be computed, starting with:

- The centroid, second moment of area about the y and z axes and product of inertia (Iy,eff, Iz,eff, Iyz,eff).

- The shear center, warping coordinates (Iwy,eff, Iwz,eff) and warping constant (Iw,eff).

The warping in relation to any pole can be obtained as usual. The mean value wmean,eff takes into account the fact that only the effective areas are considered, and to compute the shear center position of the effective section, (Iyw,eff, Izw,eff) have to be computed for the effective section. Finally, the warping constant Iw,eff for the effective section is computed.

- 3.

- Due to a possible shift in the centroid, the bending moments will change (My,eff, Mz,eff).

Following the stresses in the effective section are computed:

The coordinates yeff and zeff are referred to the effective centroid, while the warping weff is referred to the new shear center.

3.2. Numerical Examples for Class 4

These examples were calculated using the software developed by Agüero [5]. In this software, 10 fibers are used per element, although this approach is more accurate if the number of fibers is increased. Convergence was tested by varying the number of fibers per element. Using 10 fibers provided accurate results for thin-walled sections, while additional layers offered negligible improvement with an increased computational cost. This selection, therefore, ensured both efficiency and sufficient precision for practical applications.

Following examples to compute section properties in Class 4 sections, it is possible to compare the gross and effective section results when a bimoment is applied. The material considered here is steel S355.

The approach adopted in this study to obtain the effective width follows Eurocode provisions. Since effective widths are defined as functions of stress distributions, boundary conditions, and slenderness ratios, the influence of the section slenderness and local instabilities is inherently incorporated into the formulation. Moreover, the reduction factors and rules for effective widths were calibrated against experimental results for slender members, where initial geometric imperfections are naturally present. As a result, both the slenderness effects and imperfections are consistently accounted for when evaluating the performance of Class 4 sections.

3.2.1. I-Shaped Section with Two Axes of Symmetry

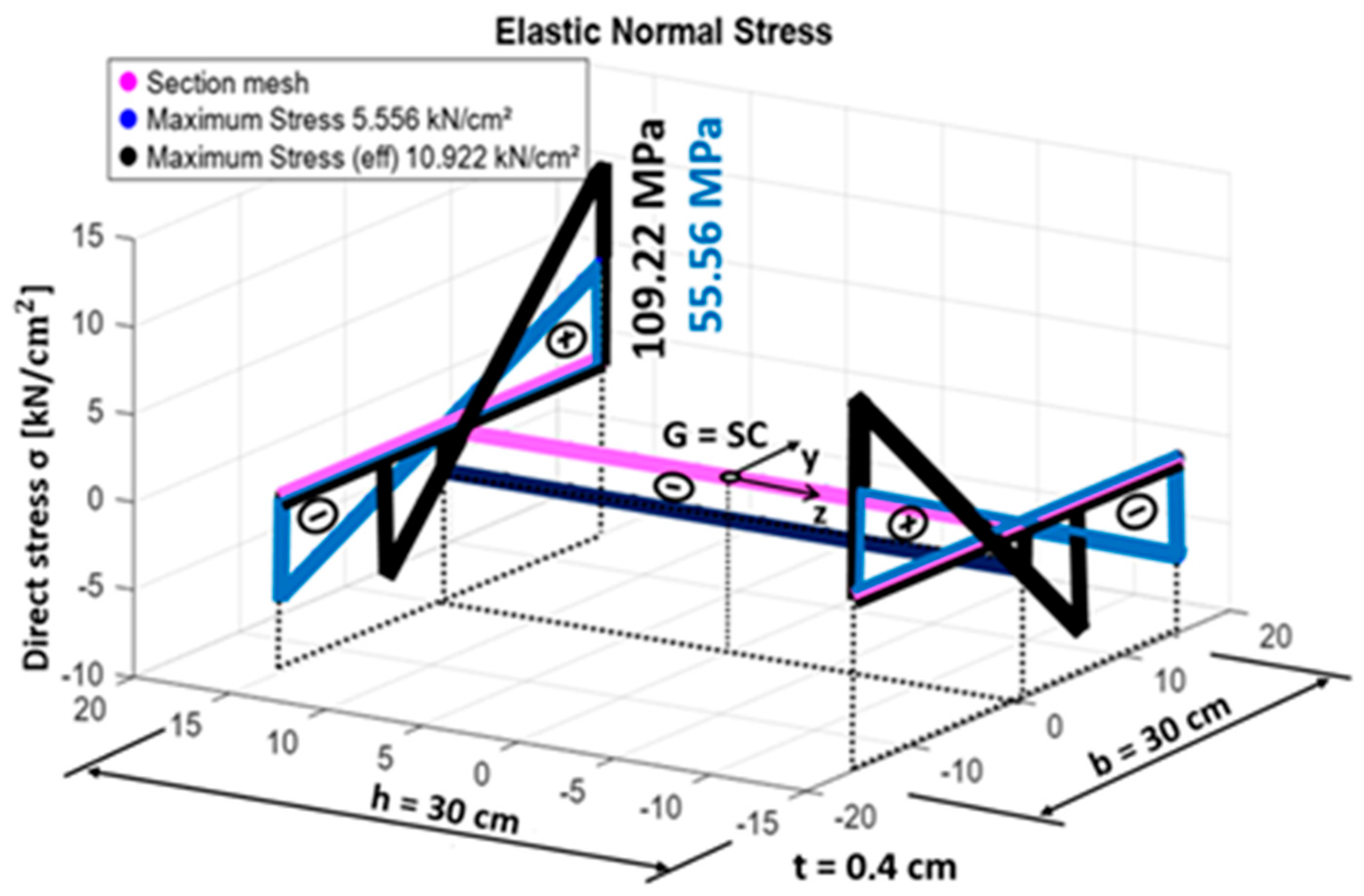

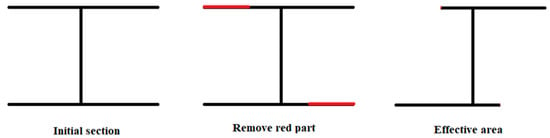

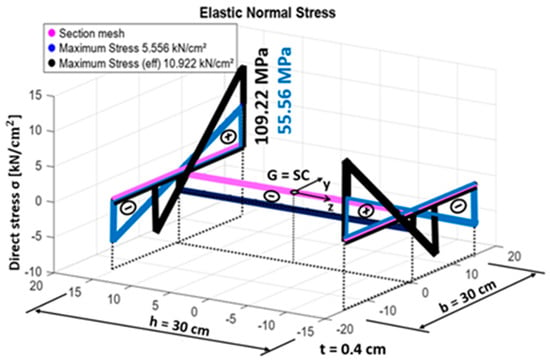

The section has dimensions of b = 30 cm, h = 30 cm, and t = 0.4 cm, and its properties and stresses are illustrated in Table 2 and Figure 5. Figure 6 shows the stresses in the sections, gross (blue) and effective (black), due to a bimoment B.

Table 2.

Properties of a Class 4 I-shaped section.

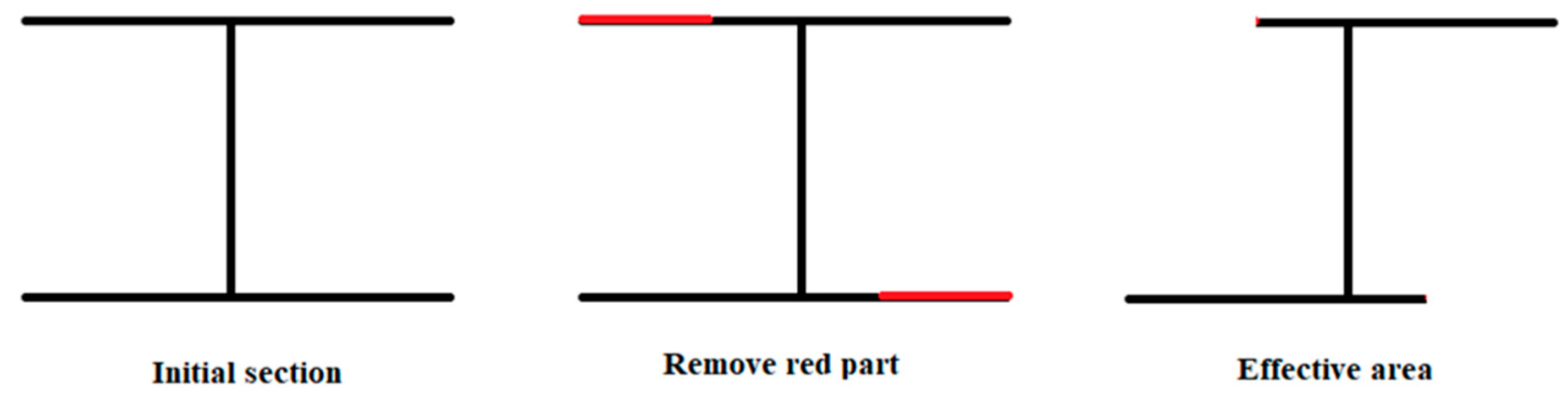

Figure 5.

Gross initial section and effective section in the case of bimoment for a Class 4 I-shaped section.

Figure 6.

I-Shaped Section. Stresses in the gross (blue) and effective (black) sections due to a bimoment B = 10,000 kN·cm2.

For the gross section, the warping constant is Iw = 405,000 cm6, with the centroid (G) and shear center (SC) located at the intersection of the two axes of symmetry. In the effective section, the warping constant is reduced to Iweff = 169,282 cm6, where the centroid and shear center remain point-symmetric. The method used to calculate the effective width follows that given in [4], using a stability coefficient of kσ = 0.57, resulting in λp = 2.1496 and ρ = 0.424. Consequently, the effective width of the compression flange is determined as 0.424 × 15 = 6.36 cm.

3.2.2. Monosymmetric Section

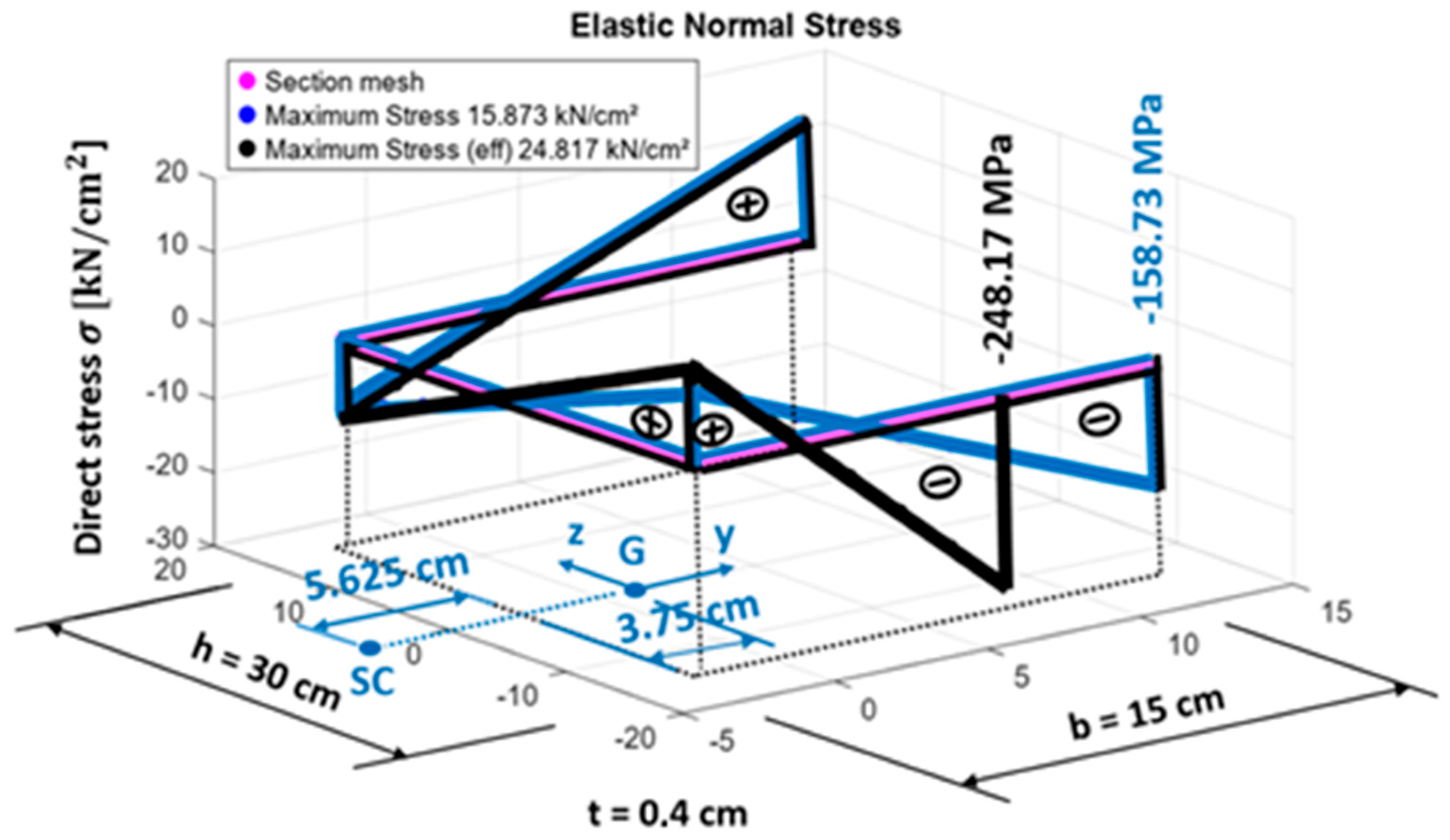

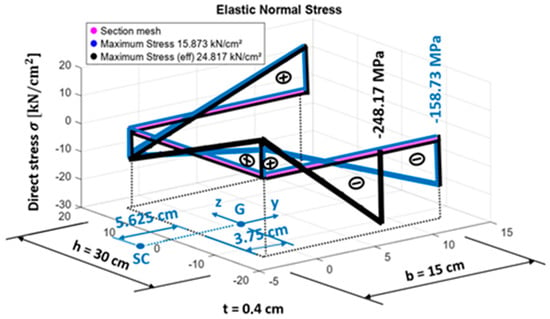

A monosymmetric channel section has dimensions of b = 15 cm, h = 30 cm, and t = 0.4 cm, with section properties (Table 3). The stresses due to a bimoment B applied are shown in Figure 7.

Table 3.

Properties of a Class 4 monosymmetric section.

Figure 7.

Monosymmetric Section. Stresses in the gross (blue) and effective (black) sections due to a bimoment B = 10,000 kN·cm2.

The warping constant for the gross section is Iw = 88,593 cm6, with the reference system originating at the bottom flange and web intersection. The centroid (G) position along the axis of symmetry is zg = 15 cm, yg = 3.75 cm, while the shear center (SC) is located at zsc = 15 cm, ysc = −5.625 cm. In the effective section, the effective width of the bottom flange is determined using values of ψ = −0.6, kσ = 0.72, λp = 1.91, and ρ = 0.47. The tensioned part of the flange measures 5.624 cm, while the effective compression width is ρ × bc = 4.4 cm, leaving a remaining portion of 4.96 cm to be removed. The effective warping constant is reduced to Iw,eff = 53,730 cm6, with the effective centroid positioned at yg,eff = 3.06 cm, zg,eff = 16.12 cm, and the effective shear center at Δzsc,eff = 5.3 cm, Δysc,eff = 1.3 cm.

3.2.3. Non-Symmetric Section

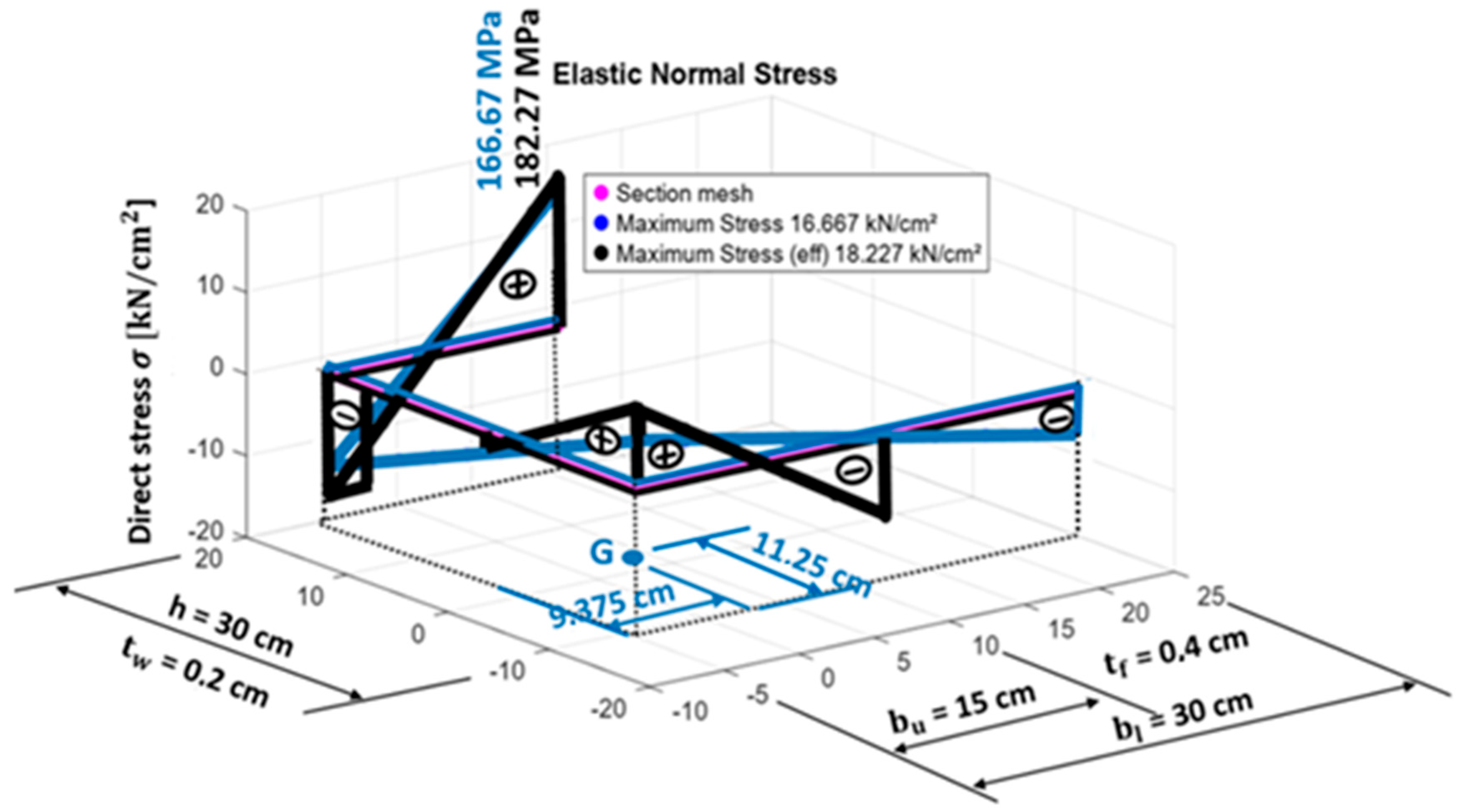

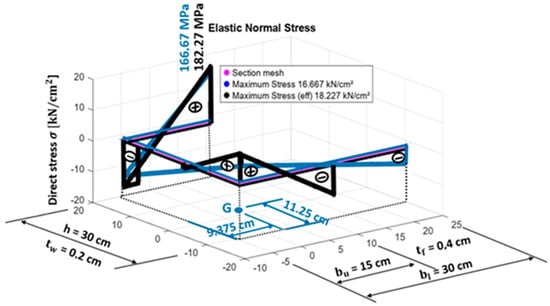

The non-symmetric channel section has dimensions as follows: top flange width bu = 15 cm, bottom flange width bl = 30 cm, flange thickness tf = 0.4 cm, height h = 30 cm, and web thickness tw = 0.2 cm, with section properties (Table 4). The stresses due to a bimoment B are shown in Figure 8.

Table 4.

Properties of a Class 4 non-symmetric section.

Figure 8.

Non-Symmetric Section. Stresses in the gross (blue) and effective (black) sections due to a bimoment B = 10,000 kN·cm2.

For the gross section, the warping constant is Iw = 135,000 cm6, with the reference system originating at the intersection between the bottom flange and web. The centroid (G) position is located at zg = 11.25 cm, yg = 9.375 cm, while the shear center (SC) is positioned at zsc = 5 cm, ysc = -7.5 cm. In the effective section, the warping constant is reduced to Iw,eff = 88,379 cm6, with the effective centroid shifting to zg,eff = 13.27 cm, yg,eff = 6.44 cm, and the effective shear center at Δysc,eff = 0.3 cm, Δzsc,eff = 5.6 cm.

4. Discussion

This study provides in-depth insights into the resistance of thin-walled steel sections (Classes 1 to 4) under the influence of bimoment effects, an essential aspect of the structural behavior of open profiles subjected to non-uniform torsion. The aim of this extended discussion is not only to present numerical results, but also to emphasize their practical significance and applicability in structural engineering.

For Class 1 and 2 sections, two methodologies were proposed and validated for the calculation of the plastic bimoment, as follows:

- Method 1, based on determining the plastic shear center;

- Method 2, in which linear programming is employed to maximize the plastic bimoment.

The results of both methods exhibit excellent agreement when applied to monosymmetric I-sections, channel sections, and asymmetric profiles, thus confirming their robustness and practical applicability. One important finding is that the results highlight the sensitivity of the bimoment to the computational approach adopted (i.e., plastic vs. elastic shear center). This observation has clear implications for design, as the methodology that is chosen can lead to significant variations in plastic interaction diagrams and hence affect structural safety and efficiency.

The study has also investigated the interaction of the plastic bimoment with other internal forces {ξNEd, ξMy,Ed, ξMz,Ed, ξBEd, ξVy,Ed, ξVz,Ed, ξTt,Ed, ξTw,Ed}. The results underline how these combinations alter the load-bearing capacity of thin-walled sections, and demonstrate that neglecting the bimoment may lead to non-conservative estimates of structural resistance. The difference between computation using the plastic shear center, as recommended by Osterrieder [12,13] and Trahair [10], and computation using the elastic shear center, as suggested by Kindmann [14,15], is particularly relevant to practitioners. These findings provide engineers with a clearer understanding of the consequences of their design choices, thereby bridging theoretical approaches with engineering practice.

For Class 4 sections, this research advances the state of the art by developing a detailed methodology to determine the effective section properties while accounting for bimoment effects. The proposed framework incorporates the calculation of the effective centroid, warping constant, and shear center based on effective widths derived from combined internal actions. Numerical examples confirm that significant reductions in warping constants and shifts in geometric properties occur between gross and effective sections. This evidence highlights the need to properly account for bimoment-induced stress redistribution and local instability phenomena in slender elements, which are particularly vulnerable to local buckling.

Overall, the findings presented in this work have direct practical implications: they provide engineers with validated tools for accurately assessing the resistance of thin-walled sections under non-uniform torsion, highlight the importance of the chosen computational methodology, and address the current limitations of design codes. The latest second-generation Eurocodes for metals (EN 1993-1-1 for steel structures and EN 1999-1-1 for aluminium structures) [1,16] include clauses that confirm the necessity of applying the proposed method in everyday engineering practice. By explicitly incorporating bimoment effects into the analysis of both stocky and slender profiles, this study contributes to safer, more efficient, and scientifically grounded structural design.

5. Conclusions

This study has addressed the complex behavior of thin-walled steel sections subjected to combined internal forces, with a particular focus on the influence of the bimoment. Both compact (Classes 1–3) and slender (Class 4) cross sections were considered, and validated methods were proposed for plastic bimoment evaluation and effective width determination. The key outcomes and implications for structural design can be summarized as follows:

- Two robust methodologies for computing the plastic bimoment in thin-walled sections were proposed and validated: one based on the plastic shear center (Method 1) and another using linear programming (Method 2). Both methods provided consistent plastic resistance values across different types of cross section (I-sections, channels, and asymmetric profiles), and the results were aligned with experimental findings available in the literature to confirm both their accuracy and their practical relevance for design.

- The interaction between the bimoment and other internal forces {ξNEd, ξMy,Ed, ξMz,Ed, ξBEd, ξVy,Ed, ξVz,Ed, ξTt,Ed, ξTw,Ed} was shown to modify the load-bearing capacity of thin-walled sections by altering the shape and limits of plastic interaction diagrams. For instance, adopting the elastic rather than the plastic shear center leads to noticeable differences in the diagrams, which in turn can influence the predicted resistance and the level of safety in design. The evidence demonstrates that this interaction significantly affects resistance, and should be systematically incorporated into engineering practice.

- For Class 4 sections, a comprehensive procedure was developed for evaluating effective section properties under the action of a bimoment. This framework includes the effective centroid, warping constant, and shear center, all of which are derived from combined internal actions. The methodology results in more accurate stress predictions than traditional approaches, as shown by the reductions in warping constants and shifts in geometric properties observed in the numerical examples.

The choice between the plastic shear center method and the linear programming approach depends on practical considerations. The linear programming method (Method 2) is particularly suitable for complex or highly non-symmetric sections, and can be efficiently implemented in software. In contrast, the plastic shear center method (Method 1) may be preferred when analytical insight into the location of plastic stresses is required or when computational resources are limited. This guidance can help practitioners to select the most appropriate method for their specific design scenario.

In summary, the study bridges critical gaps in existing structural codes and provides a solid theoretical and practical foundation for evaluating warping torsion and bimoment effects in complex cross sections. By explicitly including these effects, the proposed methods promote improved safety, performance, and optimization in structural engineering applications.

As a complementary direction, future research will also explore the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning to generate plastic interaction diagrams from cross section data, which is expected to offer promising opportunities for more efficient and advanced structural design tools.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G., A.A.-C., Y.K. and P.M.-C.; Formal analysis, A.A., R.G. and A.A.-C.; Investigation, A.A. and R.G.; Methodology, A.A., R.G., A.A.-C., Y.K. and P.M.-C.; Software, A.A. and R.G.; Supervision, A.A.; Validation, A.A., R.G., Y.K. and P.M.-C.; Writing—original draft, A.A. and R.G.; Writing—review and editing, A.A. and R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project was supported by the Slovak Grant Agency VEGA no. 1/0155/23.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Robert Glauz was employed by the company RSG Software, Inc. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- EN 1993-1-1:2022; Eurocode 3: Design of Steel Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- EN 1993-1-14:2025; Eurocode 3: Design of Steel Structures—Part 1-14: Design Assisted by Finite Element Analysis. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2025.

- Agüero, A.; Baláž, I.; Höglund, T.; Koleková, Y. Plastic design of metal thin-walled cross-sections of any shape under any combination of internal forces. Buildings 2024, 14, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1993-1-5:2006; Eurocode 3: Design of Steel Structures. Part 1.5: General Rules—Plated Structural Elements. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2006.

- Agüero, A. “Thin Wall Section Class 1, 2, 3 & 4” Software. Available online: https://labmatlab-was.upv.es/webapps/home/thinwallsectionmaterials_class4.html (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Baláž, I.; Koleková, Y. Resistances of I- and U-sections. Combined bending and torsion internal forces. In Proceedings of the 8th European Conference on Steel and Composite Structures (Eurosteel 2017), Copenhagen, Denmark, 13–15 September 2017; Volume 1, pp. 3791–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, A.; Khelil, A.; Boissonnade, N.; Bureau, A. Plastic resistance of U sections under major-axis bending, shear force and bi-moments. In Proceedings of the 8th European Conference on Steel and Composite Structures (Eurosteel 2017), Copenhagen, Denmark, 13–15 September 2017; Volume 1, pp. 3751–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streľbickaja, A.I. Limit State of Frames from Thin-Walled Beams Under Bending and Torsion; Naukova Dumka: Kiev, Ukraine, 1964. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Streľbickaja, A.I. Experimental Investigation of Elastic-Plastic Behaviour of Thinwalled Structures; Naukova Dumka: Kiev, Ukraine, 1968. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Trahair, N.S. Plastic torsion analysis of monosymmetric and point-symmetric beams. J. Struct. Eng. 1999, 125, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Chiew, S.P. A review of class 4 slender section properties calculation for thin-walled steel sections according to EC3. Adv. Steel Constr. 2019, 15, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterrieder, P.; Werner, F.; Kretzchmar, J. Plastic flexural-torsional buckling design of beams with open thin walled cross sections. In Proceedings of the 5th International Colloquium on Stability and Ductility of Steel Structures (SDSS97), Nagoya, Japan, 29–31 July 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Osterrieder, P.; Kretschmar, J. First-hinge analysis for lateral buckling design of open thin-walled steel members. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2006, 62, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindmann, R.; Frickel, J. Grenztragfähigkeit von häufig verwendeten stabquerschnitten für beliebige schnittgröβen. Stahlbau 1999, 68, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QST I-plastisch, 2014. RUBSteEl eEducation Tool, Ruhr-Universität Bochum; Lehrstuhl für Stahl-, Leicht- und Verbundbau. Version 10. Available online: https://www.stahlbau.ruhr-uni-bochum.de/sb/service/rubsteeltools.html.en (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- EN 1999-1-1:2023; Eurocode 9: Design of Aluminium Structures—Part 1-1: General Structural Rules. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).