Abstract

As immovable cultural heritage, cave temples have characteristics such as fragile structural systems, significant cumulative historical damage, and irreplaceability. Earthquakes represent a primary cause of damage, cracking, and even the collapse of cave temples and their structures in China. And earthquakes pose a serious threat to the preservation and continuity of cultural heritage resources and may result in irreparable losses on an incalculable scale. Currently, the construction of a cave-earthquake-monitoring and early-warning system is incomplete, leaving cave temples at a high risk of earthquake damage. Consequently, conducting research on the seismic protection of cave cultural heritage is of urgent practical and academic significance. In this study, we use the seismic monitoring array installed at the Yungang Grottoes to conduct research on seismic motion prediction. This provides fundamental data to support seismic risk assessments, the development of seismic resistance standards, and the creation of an emergency response plan for the Yungang Grottoes. This study involved designing the TLSA-SO prediction network model and using the Datong Yungang Grottoes as an empirical research subject to validate the model’s effectiveness and accuracy. The results of the experiments show that the model achieves a prediction fit of 0.99 for environmental vibrations, enabling highly precise predictions. This provides critical technical support for the monitoring of environmental vibrations at cave-type cultural heritage sites and demonstrates the feasibility of implementing seismic preventive conservation measures at such sites.

1. Introduction

Cave temple cultural heritage sites are characterized as immovable cultural resources due to their fragile structural systems, significant cumulative historical damage, and irreplaceability [1,2]. Cave temples have generally suffered from a variety of problems under the combined influence of long-term natural forces and human activities, including decreased slope stability, rock collapse, the expansion and penetration of fissures, the peeling and collapse of cave structures, and the cracking, salt erosion, and surface weathering of murals and sculptures [3,4,5]. Since 1949, researchers in China have made significant progress in their efforts to protect cave temples. Some of these projects have been pioneering and influential, marking important milestones in the history of cultural heritage protection. These conservation practices have kept pace with social and economic development and technological progress throughout this time, evolving from simple support to engineering reinforcement and from scientific research applications to multidisciplinary collaboration. Ultimately, this has resulted in the formation of a scientifically sound and technologically advanced system of scientific and preventive conservation [6]. As the focus of conservation shifts from rescue to prevention, the monitoring and protection system for grotto temples continues to evolve. In addition to traditional risk factors such as the microenvironment of caves, damage to cultural relics, and structural stability, the system now covers the real-time monitoring and comprehensive prevention and control of sudden threats such as extreme weather, floods, sandstorms, and seismic activity [7,8,9,10,11].

Environmental seismology studies natural seismic vibrations triggered by external processes (such as the cryosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere, and more distant areas) or their propagation in the solid Earth, which are affected by changes in external environmental parameters (temperature, hydrology, etc.) or human activities [12,13]. The emergence of environmental seismology has provided a new paradigm for geological disaster monitoring [14]. This discipline analyzes seismic signals generated by surface processes (such as landslides, rockfalls, and debris flows) to enable the quantitative assessment and real-time early warning of disasters. Its technical approach involves the real-time capture of seismic waves generated by the release of energy from geological disasters, followed by rapid localization, dynamic tracking, and the inversion of dynamic characteristics [15,16,17,18]. Nie et al. (2025) [19] discovered that landslides caused by rainfall can be seen by monitoring several things at once (like how much the land moves, how much it rains, and the pressure in the soil). They also suggested a way to check the risk by checking many things at once. Xu et al. (2025) conducted a study on spatiotemporal seismic response analysis in complex geological environments, which demonstrated the necessity of considering the geological background in environmental vibration impact analysis and further improving the systematic framework of the research [20]. Xu et al. (2025) [21] studied how the goal of warning about all kinds of hazards could be expanded from just warning about damage to buildings to warning about the protection of people and the environment. This would make the research more useful. The research above gives a practical basis for the integration of multi-disaster warning systems.

Yang Yunpeng deepened the understanding of the formation, migration, and disaster-causing processes of collapse-type debris flows by analyzing the fluid dynamic characteristics and internal dynamic mechanisms contained in seismic motion signals [22]. This has promoted an improvement in the debris flow early-warning and forecasting technology system and provides effective technical means for early warning and risk prevention and control. Yang Jipeng applied seismic monitoring techniques to the monitoring of regional bridges during major earthquakes, as well as to the rapid, quantitative assessment of their condition after seismic activity [23]. Wang Haonan used microseismic monitoring technology and source location algorithms based on seismic wave inversion theory to analyze microseismic signals triggered by rock mass disturbances or fracturing. By analyzing waveform characteristics, spectral properties, and amplitude parameters, he was able to precisely locate sources and estimate energy, thereby constructing regional energy field distribution models [24]. Wang Zhangyu applied novel vibration-monitoring techniques to various scenarios, including vehicular traffic and airport surveillance [25,26]. The Gansu Earthquake Agency deployed seismic motion monitoring at the Maijishan Grottoes. A dense monitoring network enables the real-time tracking of vibrations around the grottoes and provides foundational data for their preventive conservation [26].

The signals recorded by seismometers typically include seismic signals and seismic background noise. Seismic background noise refers to the continuous vibration signals recorded by seismometers in the absence of obvious seismic sources (such as natural earthquakes or explosions) [27,28]. Existing research has shown that seismic background noise reflects changes in the structure of the Earth’s crust, changes in the surface environment, the intensity of human activity, and seismic precursor signals. For example, previous studies [29,30,31] have used background noise to investigate the dynamic response of the Opéra Tower in France, finding that changes in seismic background noise can reflect fluctuations in the building’s fundamental frequency due to external environmental conditions, thereby indicating changes in the building’s stiffness. Mainsant et al. (2012a, 2012b) utilized background noise to study the Les Diablerets landslide in Switzerland, finding that changes in seismic background noise can reflect a significant decrease in relative wave velocity five days prior to the landslide, with this change serving as a precursor to landslide activity [32,33].

Earthquake background noise is a type of time-series data that often contains complex relationships and long-term dependencies. Traditional time-series models, such as ARIMA and VAR, are based on linear assumptions. This makes them difficult to use effectively to capture complex nonlinear dynamics in the real world [34]. Therefore, research on how computers process data over time has now turned to deep learning models. In deep learning models, backpropagation (BP) neural networks, as a typical feedforward network, lack connections between neurons within their layers. This makes it difficult to effectively model how information is dependent on what came before it in data that is in a sequence [35]. On the other hand, normal recurrent neural networks (RNNs) add connections between layers based on BP neural networks. This allows information to be sent in sequences, combining past information with the current time [36,37]. However, the gradient multiplication of RNN causes problems when processing long sequence data, which limits how long it can predict. To solve the problem of predicting time series-data that depends on previous values, we can use a type of neural network called GRU [38,39]. This network has special units called ‘hidden units’ that can remember previous data. GRU is used to construct deep neural networks to learn how seismic waves change when they travel through the ground [40].

Most scholars are also studying Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), which can effectively capture local features in time-series data. Zhang and his team used special computer programs (called CNNs) to quickly identify and label different types of earthquake waves (like P-waves and S-waves). This helps to improve earthquake warning systems [41]. CNN is used to study and predict the relationships between features in a time series. To make the most of each method, Wu et al. (2021) [42] suggested a special type of computer program called a CNN-LSTM hybrid model. The results showed that this hybrid model worked better than the single CNN and single LSTM models. However, all features in the model are treated equally, which may mean that some important features are overlooked. Babak Alizadeh and his team suggested using an LSTM model that uses both an attention mechanism and Bayesian optimization [43]. This LSTM Attention model is better at processing complicated time-series data by focusing on important time points. We suggested using a special type of computer program (called an SA-LSTM deep learning model) to predict how things might move or change shape in the future [44]. The results showed that the SA-LSTM model is good at predicting long-term sequence data and is better at this than a single LSTM network. However, this model cannot handle sudden unusual data. We are still in the early stages of using earthquake background noise monitoring to protect cultural heritage like grotto temples. So far, no researchers have suggested a time-series prediction network model that can effectively apply earthquake background noise.

In summary, environmental seismology has found widespread application across various fields based on seismic monitoring, while research on environmental background noise can reflect changes in the crustal structure and surface environmental conditions. Therefore, this paper will adopt the research approach of environmental seismology, leveraging the seismic monitoring array deployed at the Yungang Grottoes, utilize its observational data to conduct seismic-motion-prediction studies for the grottoes, and predict the seismic background noise of the Yungang Grottoes. Design a TLSA-SO prediction network model, validate the model’s effectiveness and accuracy, and provide a new method for the environmental seismic monitoring of cave-type cultural heritage sites by monitoring changes in the seismic background signals of the caves.

2. Design of a Seismic Prediction Network for Stone Cave Temple Cultural Heritage Sites

2.1. Model Network Design

Seismograph recordings of seismic signals and surface displacement data of architectural heritage components share characteristics such as non-linearity, non-stationarity, and complexity. Therefore, traditional analysis methods struggle to effectively capture their dynamic changes and multi-frequency characteristics. In designing the predictive network, this study comprehensively applied multiple deep learning techniques, integrating time convolutional networks (TCNs) and long short-term memory networks (LSTMs). Among them, TCNs can effectively capture dependencies over long-term intervals [45,46,47], while LSTM can handle long-term dependencies and capture sudden fluctuations and local nonlinear features in the time series [42,48,49,50,51]. The combination of the two can better handle the complex relationships in long time-series data.

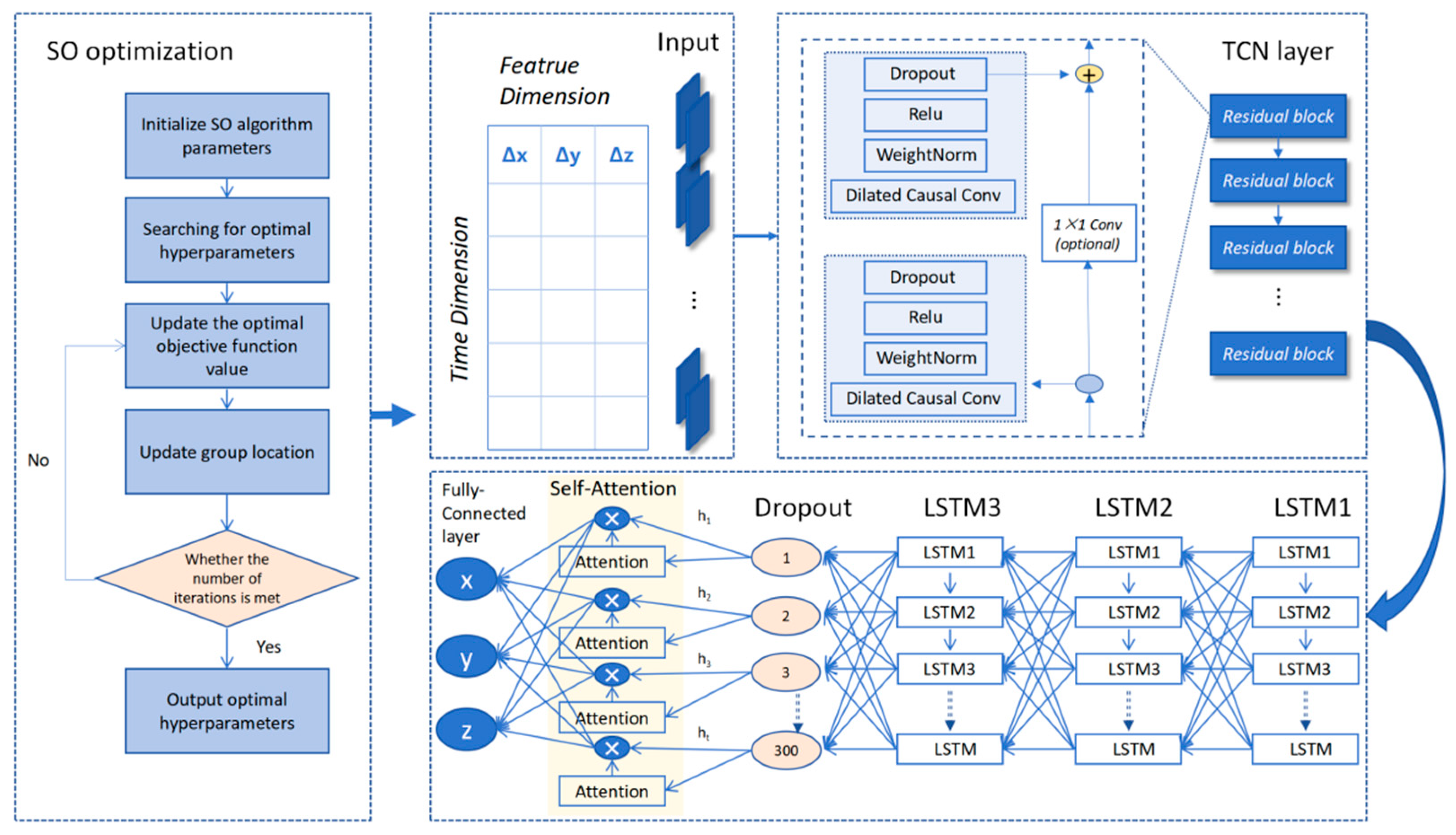

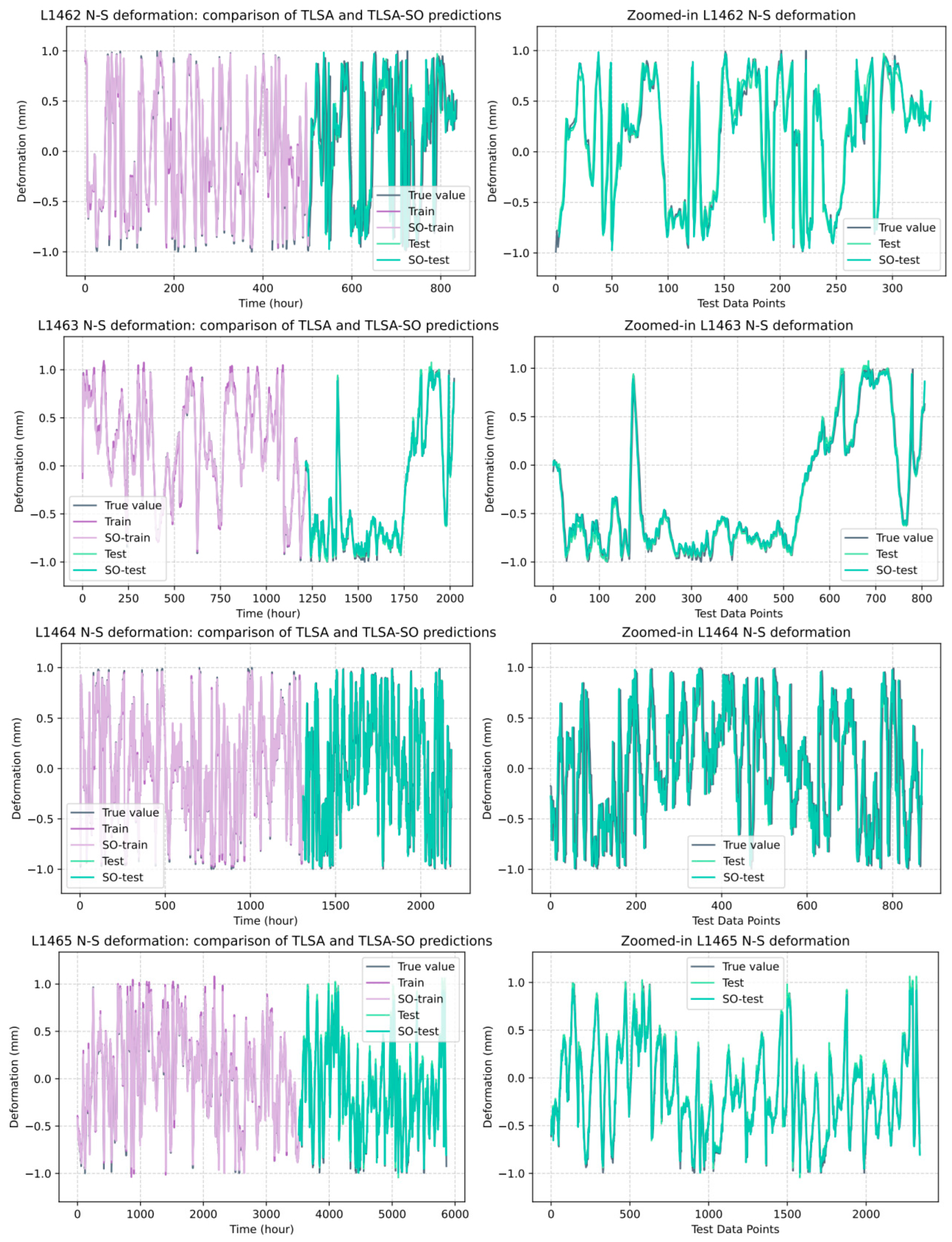

Additionally, this paper introduces a self-attention mechanism where each element in the input sequence not only considers its correlation with other elements but also its relationship with itself [52,53,54,55,56]. This allows the network to assign different weights to various features within the input sequence, enabling it to focus more on aspects relevant to the current task. The snake optimization (SO) algorithm is a global optimization method that can help to find better model parameters and reduce local optimum problems [57]. It is well-suited to solving complex optimization problems and offers the advantages of fast convergence, stable performance, high robustness, and accurate results [58,59]. The TLSA-SO deep learning neural network designed in this study focuses on constructing a background noise behavior model for grotto temples, providing a reference for monitoring changes in seismic background noise in grotto temples and offering key technical support for environmental vibration monitoring of grotto-type cultural heritage sites. This lays a feasible foundation for the seismic preventive protection of grotto-type heritage sites. The structure of the TLSA-SO model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

TLSA-SO network model architecture diagram.

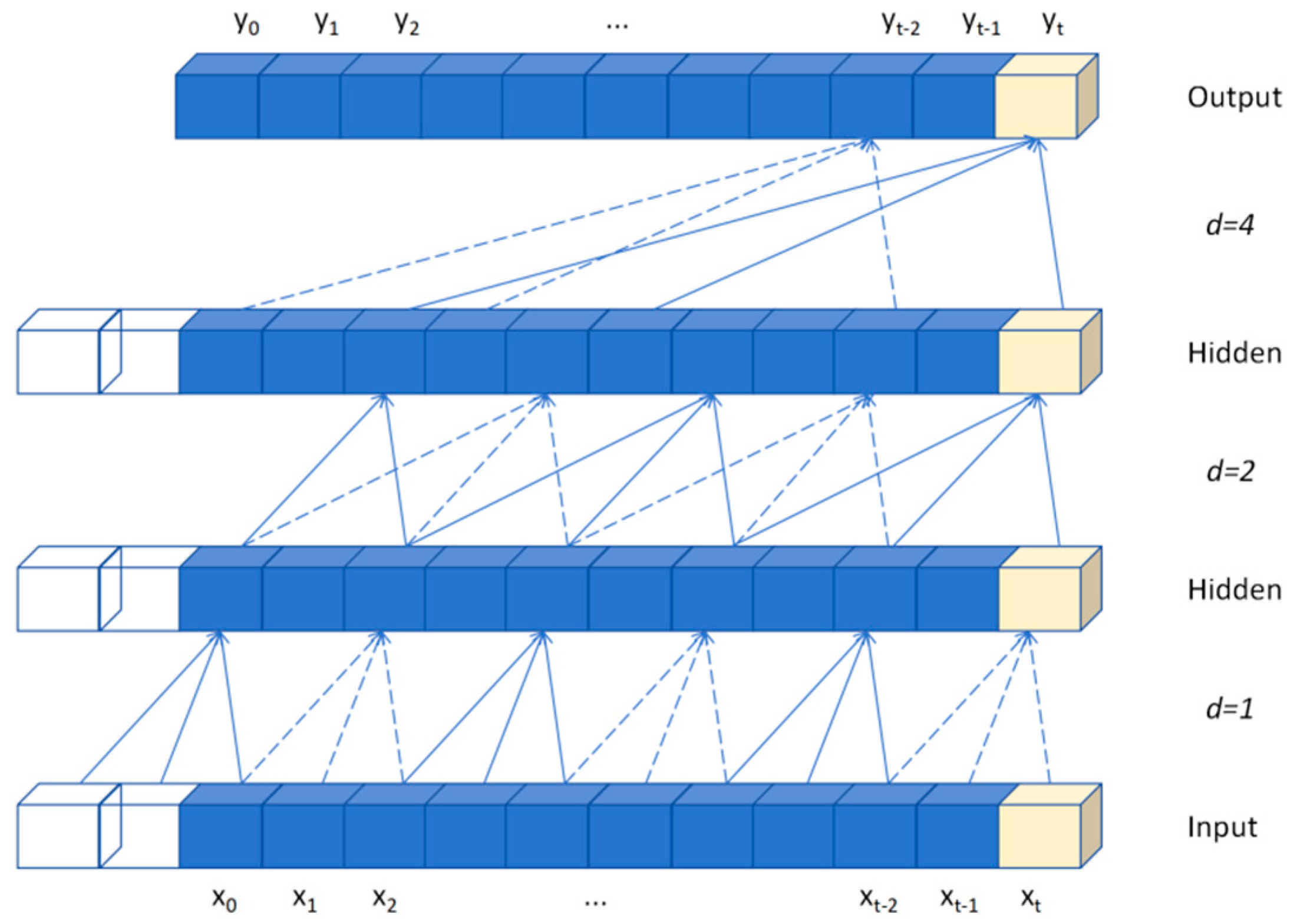

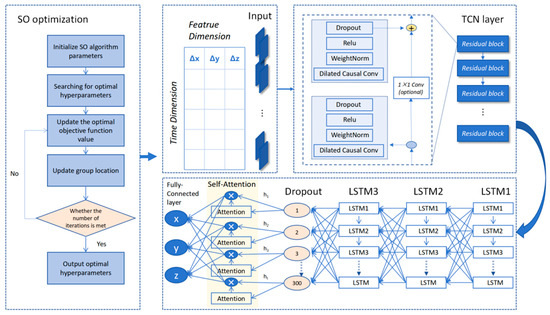

The model consists of an input layer, a TCN layer, a stacked LSTM module, an attention layer, and an output layer. The input layer receives a 3D tensor with the dimensions (batch_size, look_back, input_features), and the output layer maps this to a 2D tensor with the dimensions (batch_size, output_features) via a fully connected layer. The total number of samples is represented by batch_size, and the dataset is divided into training and testing sets in a ratio of 8:2. The TCN module comprises stacked residual cells, each of which contains two 1D dilated causal convolutional layers with integrated weight normalization, an activation function, and a dropout layer. As a CNN variant designed for temporal data, the TCN module expands the receptive field synergistically through causal convolution (to ensure temporality) and dilation convolution (to control the interval d), thereby capturing long-term dependencies. Unlike ordinary causal convolution, which only expands the receptive field linearly, dilation convolution achieves exponential growth through the base b (satisfying b ≤ kernel size). The increment of the receptive field per layer is calculated as (k − 1) × d, where d = bi (i is the number of layers), as shown in Figure 2 (b = 2, kernel size = 3). The expression for computing the receptive field size s is shown in Equation (1).

where n denotes the number of layers in the extended convolution, k denotes the size of the convolution kernel, and b denotes the expansion base. The formula shows that the sensory field of the TCN grows exponentially with the number of layers and that different lengths of temporal data can be accommodated by adjusting this number. The causal convolution strictly adheres to temporal unidirectionality (the output at time t depends only on t and historical inputs) in order to prevent interference from future information. The residual unit optimizes the 1D causal convolution to create a (k, d)-parameterized residual block containing a double convolutional layer structure, accelerating convergence and achieving multiscale feature extraction by expanding the convolution at d-controlled intervals.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the dilated causal convolution structure.

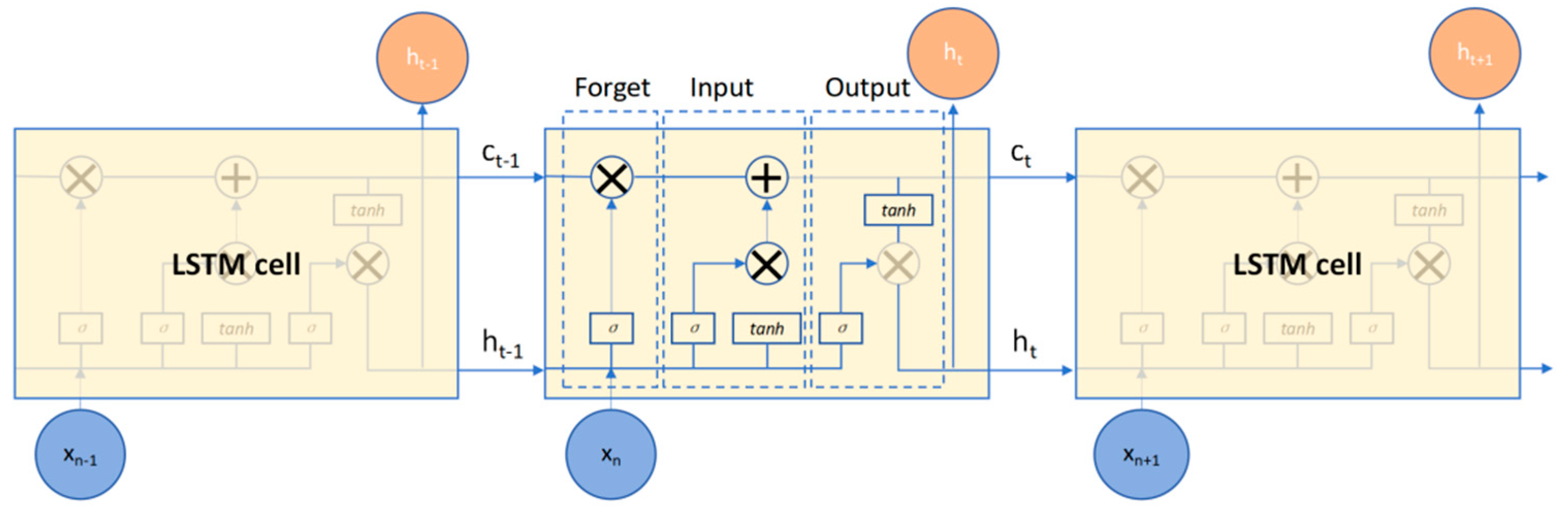

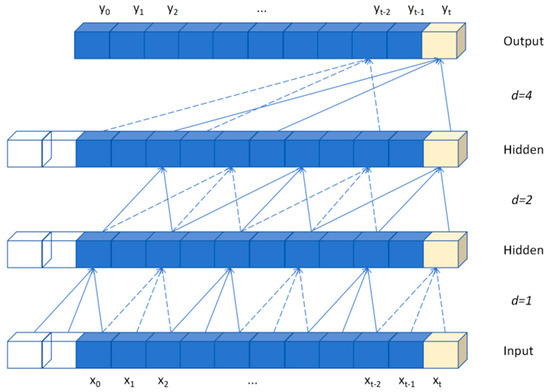

The LSTM layer receives the temporal features extracted by the TCN and uses a gating mechanism (input gate, oblivion gate, and output gate) to dynamically regulate the flow of information and enhance the modeling capability of long-term dependencies. As illustrated in Figure 3, the cell structure takes the hidden state h_(t − 1) and the current input x_t at time t − 1 as inputs and produces the updated cell state c_t and the hidden state h_t. The forgetting gate filters historical information, the input gate combines new features, and the output gate generates a valid representation at the current time. This nonlinear gating design solves the gradient problem of traditional RNNs and is well-suited to long-interval time series event analysis.

Figure 3.

LSTM cell structure and working mechanism.

The LSTM network processes the current input x_t and the hidden state ht−1 from the previous moment. The forgetting gate filters historical information, and the input gate updates the cell state Ct. These two gates then collaborate to generate the current memory state. Finally, the output gate generates the hidden state ht to be passed to the next moment. SO optimization has verified that the optimal structure is a three-layer stacked LSTM: the first layer (100 neurons) processes the original input; the second layer (200 neurons) strengthens feature extraction; and the third layer (300 neurons) outputs the prediction results. This configuration significantly improves the prediction accuracy and stability.

The Dropout layer randomly sets the output of neurons to zero during training to stop overfitting, with a dropout rate of 0.2, which means that the probability of discarding a portion of the attention values is 0.2. However, TCN/LSTM is prone to failure when predicting long sequences due to information decay at each layer. The self-attention mechanism introduces a direct correlation between inputs and outputs across steps, thereby avoiding information loss through multi-layer transmission. By dynamically weighting the LSTM output and focusing on key timing features, the mechanism can significantly improve prediction accuracy and efficiency.

The performance of a model is significantly affected by its hyperparameters (e.g., convolutional kernel size, network depth, and learning rate), which require experimental tuning to determine the optimal combination. The SO algorithm is used to generate these combinations by searching a multidimensional hyperparameter space and simulating the fighting and mating behaviors of snakes, with the goal of minimizing the loss function.

The snake optimization algorithm first generates a uniformly distributed random population, then classifies and selects each solution based on its fitness. Inefficient solutions are then eliminated through competitive behavior.

The initial population can be obtained using the following equation:

The position of the first individual is given by r, which is a random number between 0 and 1. The lower and upper bounds of the problem are given by and , respectively. The positions of the male and female individuals in the exploration phase are given by and , respectively. The position of the snake individuals in the exploitation phase is given by . In the SO algorithm, the population is divided into two groups: males and females. The individuals (solutions) in each group then interact with each other according to their fitness or the efficiency of problem solving. If Q < 0.25, the snake searches for a solution by selecting a random position and updating the optimal solution space region. The male snake solution space region is updated.

Update on the optimal solution space region for female snakes:

If Q is greater than 0.25 and the temperature is greater than 0.6, the snake will only move towards the potential solution.

The snake optimization (SO) algorithm dynamically updates the population position by simulating snake foraging behavior. It iterates until the convergence condition is satisfied and outputs the most adapted individual as the optimal solution. This model uses SO to optimize four key hyperparameters: the learning rate; the number of long short-term memory (LSTM) neurons; the attention key value; and the regularization parameter. Its position-updating mechanism is divided into two phases: exploration (random searching when there is insufficient food) and exploitation (directional movement or mating struggle when there is sufficient food). The specific process is detailed in the literature [19].

2.2. Evaluation Indicators

To measure the deviation between the evaluation model’s predicted values and the actual observed values, this study uses three statistical indicators, the mean absolute error (MAE), mean square error (MSE) and root mean square error (RMSE), as well as goodness of fit (R2), to reflect the model’s performance and the level of prediction accuracy.

MAE is the average absolute error between the predicted and actual values of the model and characterizes the average level of all prediction errors; the smaller the value, the better the prediction effect. MSE assesses the discrepancy between the model’s predicted values and the actual values; the smaller the MSE, the closer the predicted values are to the actual values and the higher the model’s accuracy.

RMSE is the standard deviation of the prediction error and is more sensitive to larger samples with larger prediction errors. RMSE is more sensitive to larger samples; the smaller its value, the better the model’s prediction performance. R2 measures the degree of fitting between the predicted and real values in the prediction model. The closer its value is to 1, the more perfect the model. The specific calculation is shown in Equation (6):

where n is the number of samples, and the residual sum of squares and the total sum of squares, y, denotes the average of all actual values.

3. Overview and Data of the Study Area

3.1. Tectonic Background of the Study Area

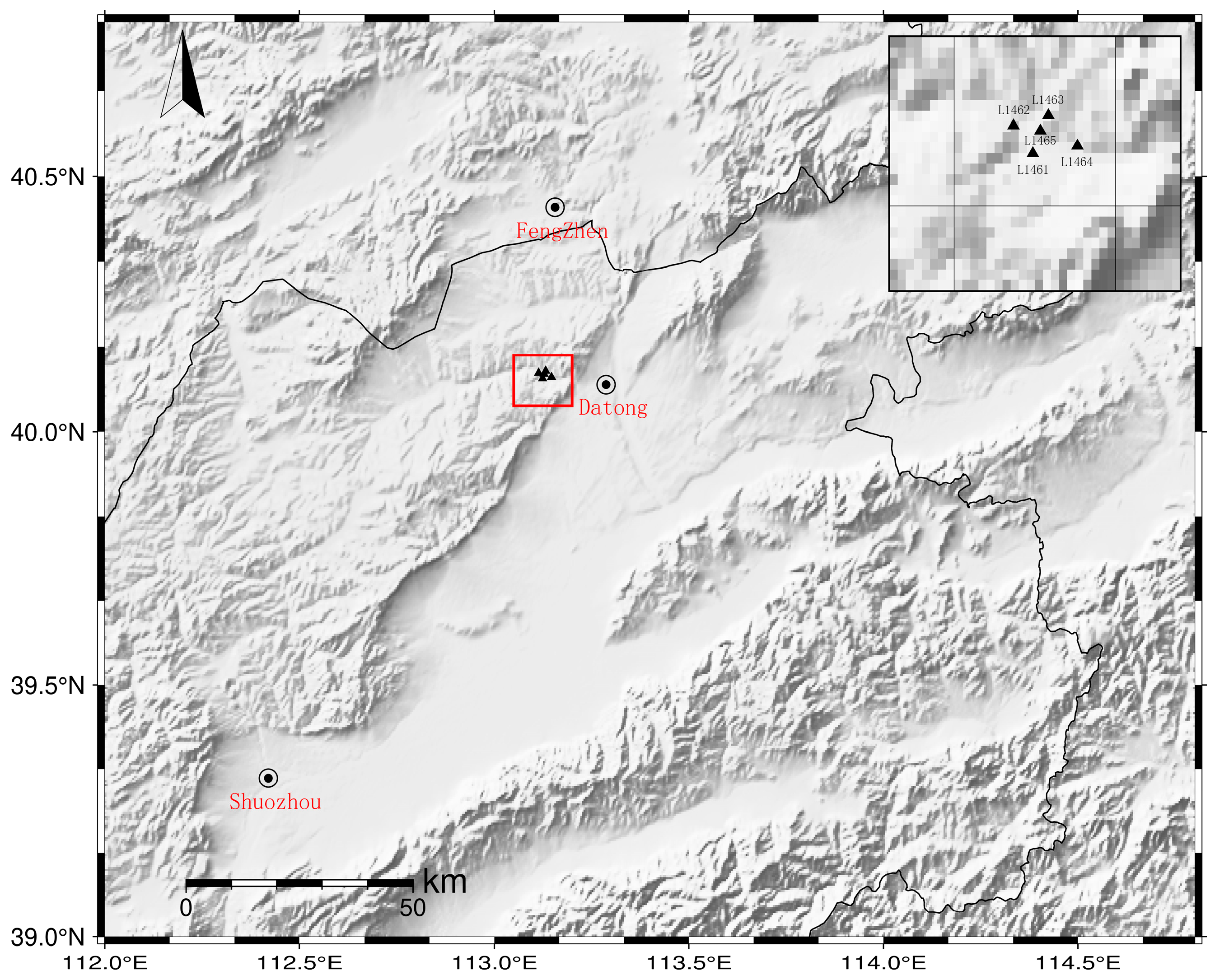

The Yungang Grottoes are located on the southern slope of Wuzhou Mountain, 16 km west of Datong City, in Shanxi Province. Stretching 1 km from east to west, they were carved during the Northern Wei Dynasty in the 5th century AD. They are a treasure trove of Chinese sculptural art and hold significant cultural, artistic, religious, and historical value. The Datong region, situated at the junction of Shanxi, Hebei, and Inner Mongolia provinces, is one of the most seismically active areas in North China. It features active faults at shallow depths, major faults at deeper levels, undulations in the low-velocity zone of the middle to lower crust, and persistent, low-velocity anomalies from the lower crust to the upper mantle. The Curie isotherm exhibits uplift phenomena, indicating a deep–shallow structural environment and background conducive to the generation of strong earthquakes [60].The basin-controlling faults in the Datong Basin include the Hengshan North Slope Fault, the Liulingshan Foothill Fault, the Kouquan Fault, and the Yanggao–Tianzhen Fault [61]. The Datong Basin and its adjacent areas are controlled by a regional stress field, characterized by northeastward compression and northwestward extension [62,63]. Historically, the region has experienced multiple moderate to strong earthquakes, including six earthquakes of magnitude 6.0–6.9 and one earthquake of magnitude 7.0–7.9. The largest earthquake was the 7.0-magnitude earthquake in Lingqiu, Shanxi Province, in 1626 AD. The seismic activity along the Liulingshan Mountain Front Fault has been relatively weak since the Quaternary period, with the largest earthquake being the 5.9-magnitude earthquake in Datong–Yanggao in 1989.

3.2. Processing and Analysis of Seismic Monitoring Data for Cave Temple Cultural Heritage Sites

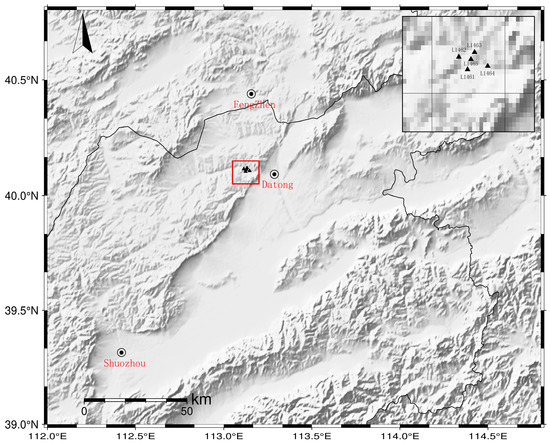

The data used in this study were obtained from a dense array of observation stations erected by the Seismological Bureau of Shanxi Province in the Yungang Grottoes study area. Observation of the station array began in May 2024 with four stations. The array was observed using an CMG-3ESPC-60 seismometer (Güralp Systems Limited, Aldermaston, UK.) with a sampling rate of 100 Hz and a bandwidth of 60 s-50 Hz (Figure 4). We selected the three-component continuous waveform data recorded by the station array for preprocessing. Firstly, we combined the hourly data for a whole day. We merged the data based on the absolute time recorded per hour and automatically added zeros if the data is interrupted; if the data overlaps, one can compare whether the overlapping data is the same or average the overlapping waveforms. Then, we converted the seismic data into east–west, north–south, and vertical component displacements (mm) by measuring the instrument response. This conversion process eliminates the interference of the instrument’s own characteristics on the original signal, allowing the data to truly reflect the actual motion state of the underground medium. Due to the high sampling rate of our data, we down-sampled the data for prediction to improve the efficiency of the model.

Figure 4.

Distribution of stations within the study area.

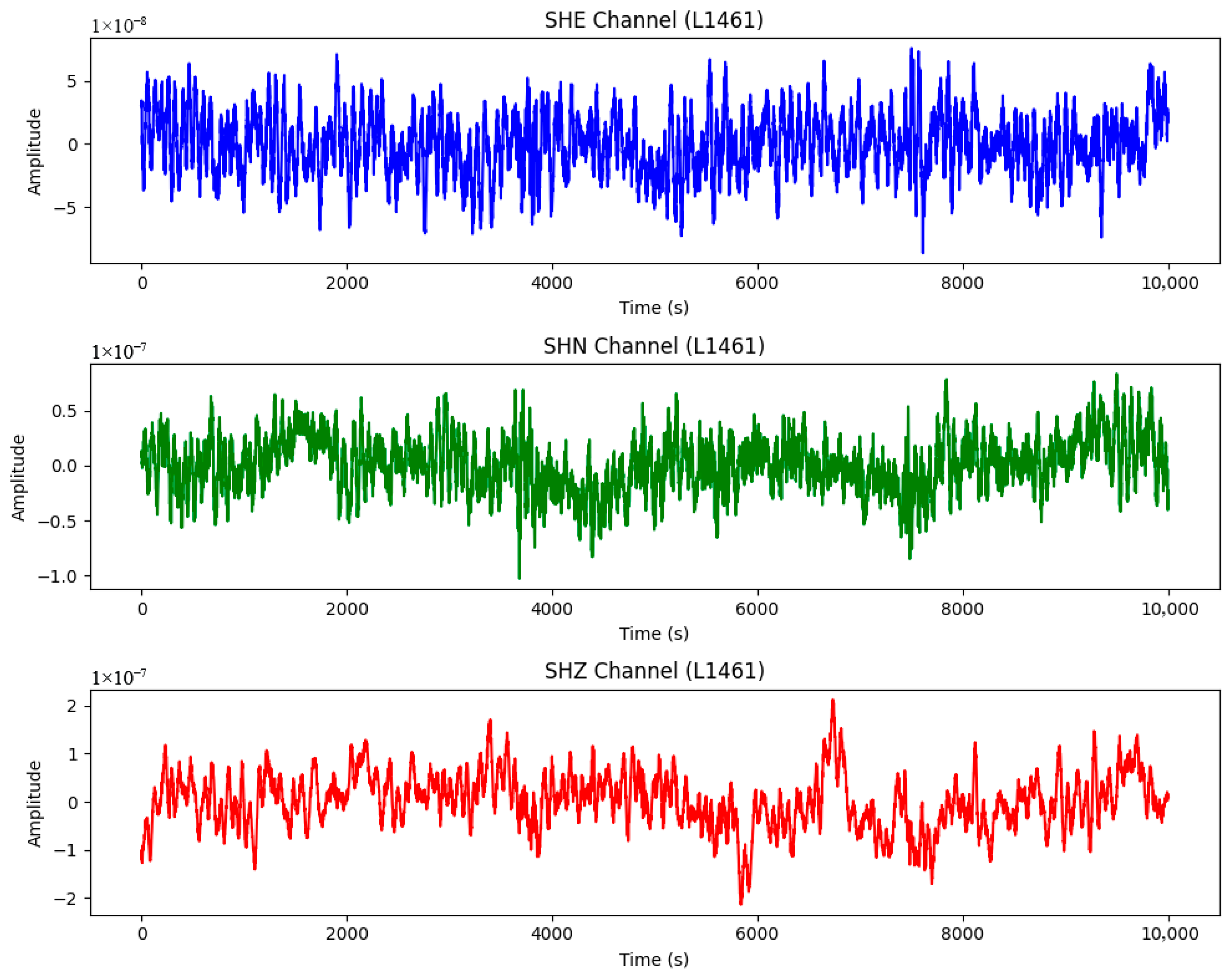

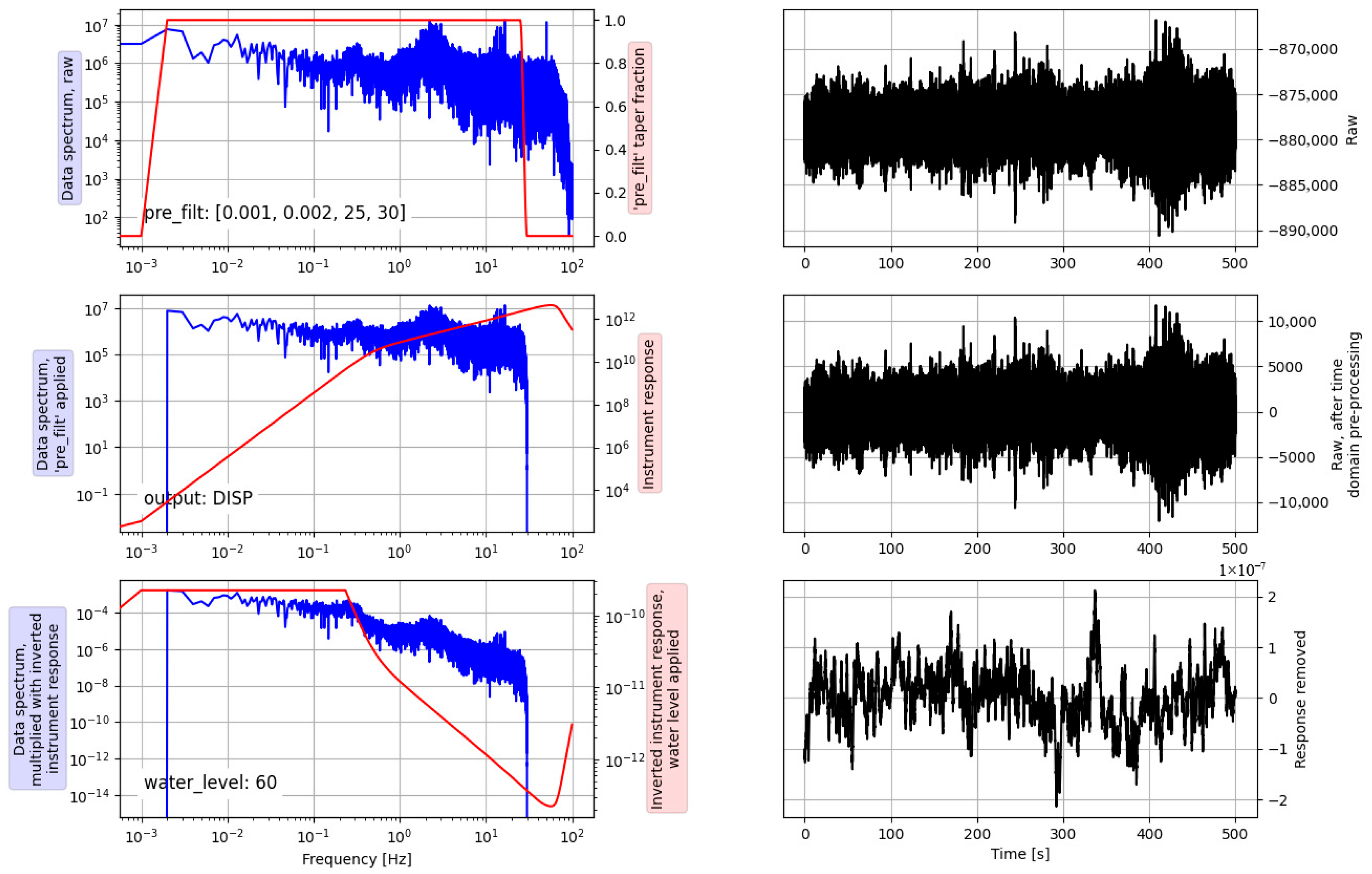

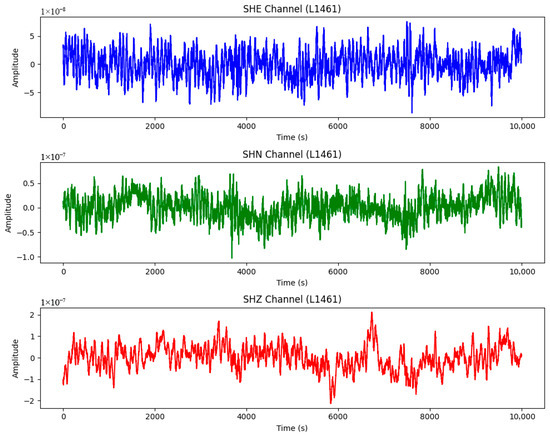

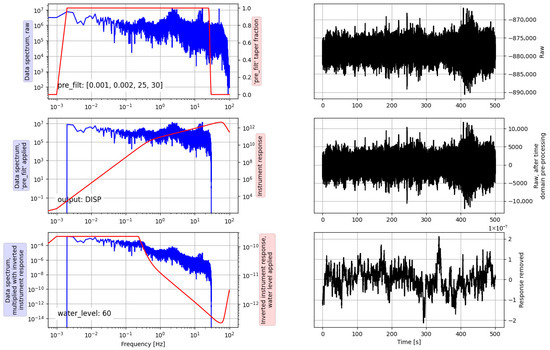

As shown in Figure 5, the east–west, north–south, and vertical components of the seismic background noise recorded by the preprocessed stations are displayed. Background noise may include changes brought about by crustal structural changes, surface environmental changes, and the intensity of anthropogenic activity in the grotto study area. We converted the seismic data into displacement (in millimeters) for the east-west, north-south, and vertical components by measuring the instrument response, with the specific process shown in Figure 6. After down-sampling, we finally selected the three-component monitoring data from station L1461 for the predicted behavioral map of background noise changes in the grotto area.

Figure 5.

Recorded three-component waveform at the station L1461.

Figure 6.

The data-processing process for vertical data recorded by L1461 on 11 September 2024.

4. Earthquake Motion Prediction for Cave Temples: Cultural Heritage Based on the TLSA-SO Model

4.1. Analysis of Model Prediction Results

This study applies the proposed network model to real Yungang Grottoes seismic monitoring data to test its performance. The selected dataset was derived from seismic monitoring data collected at the Yungang Grottoes between May and September 2025. Coordinates were collected for fixed monitoring points in the study area to cover vertical, north–south, and east–west directions. The coordinates and displacements (in mm) of the fixed monitoring points in the Yungang Grottoes study area were collected in the aforementioned directions. With a frequency of data acquisition of 100 Hz, the continuous observation data collected by seismometers can monitor background noise changes in the Yungang Grottoes study area at different scales and for different reasons. This provides a solid foundation for monitoring background-noise changes in the study area.

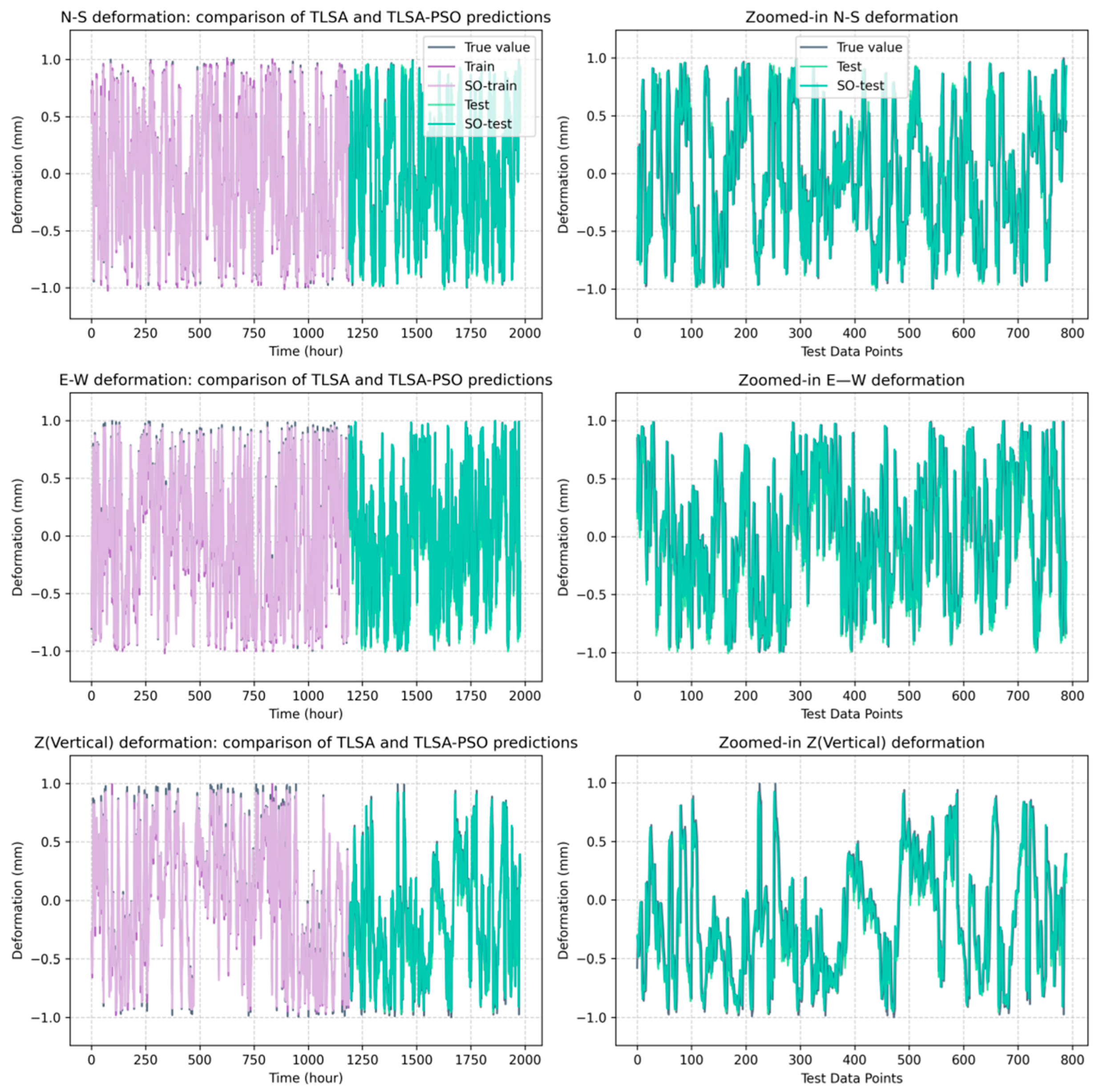

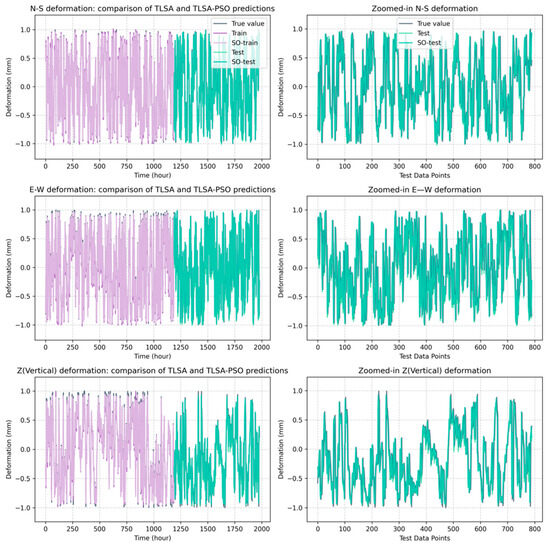

Figure 7 compares the performance of the displacement-prediction models based on TLSA-SO and TLSA for the data recorded on 11 September 2024 at monitoring station L1461 in the Yungang Grottoes, China, in the training and test sets. The true value represents the real monitoring data, train represents the prediction result of the TLSA network training set, test represents the prediction data of the TLSA model test set, so-train represents the prediction result of the TLSA network training set, and so-test represents the prediction data of the TLSA model test set. So-train shows the optimized TLSA-SO training set prediction results and so-test shows the TLSA-SO network test set prediction data. As can be seen in Figure 7, the prediction results of both TLSA and TLSA-SO roughly follow the trend of the true values. However, the so-test results predicted using the TLSA-SO network are clearly closer to the true values. These results demonstrate that the TLSA-SO network generally achieves a higher prediction accuracy than the TLSA network.

Figure 7.

The comparison of TLSA and TLSA-SO prediction results for the different L1461 components.

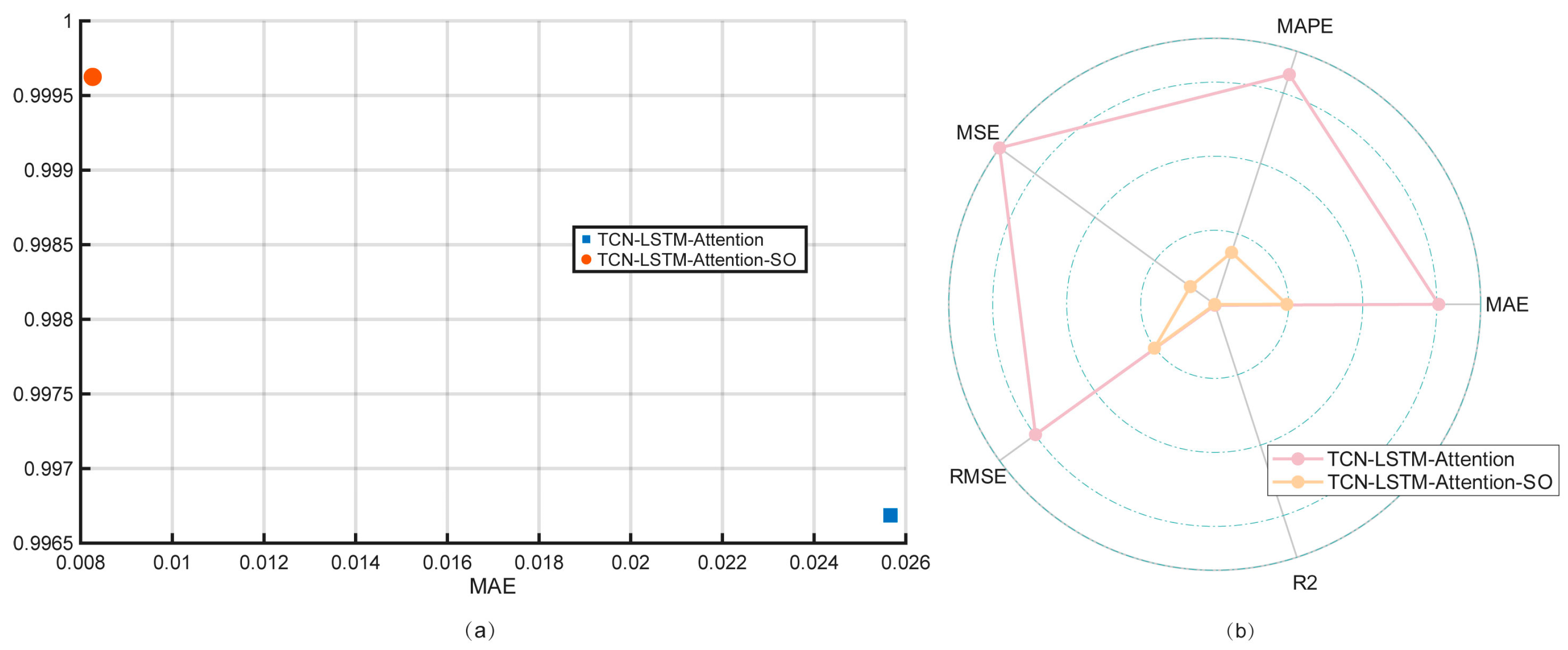

4.2. Model Prediction Accuracy Analysis

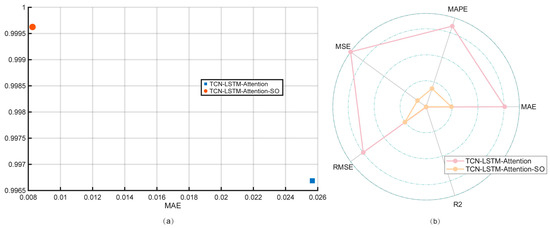

A prediction analysis is made for station L1461 in the Yungangshi study area based on the proposed TLSA-SO behavioral prediction model. The prediction accuracy of the TLSA-SO model is compared with that of the TLSA model. The TLSA-SO model predicts changes in background noise with a goodness of fit of 0.99, as shown in Figure 8a. The comparison results are shown in Radar Figure 8b. The MAE of the TLSA-SO model is reduced by a maximum of 00.0174, 0.0613, and 0.0274. The RMSE is reduced by a maximum of 0.0206, 0.0664, and 0.0319 in the three directions, respectively, indicating that the model’s predicted values are closer to the actual values. The maximum decrease in the R2 value is 0.00396, 0.00113, and 0.0018, respectively, which indicates that the TLS A model optimized by the SO algorithm has enhanced its ability to fit the data, enabling it to better capture patterns and trends in the time series.

Figure 8.

Analysis of model prediction accuracy of TLSA and TLSA-SO model. (a) Comparison of TLSA and TLSA-SO model fit. (b) Comparison of TLSA and TLSA-SO prediction accuracy.

4.3. Validation of Model Generalization Capability

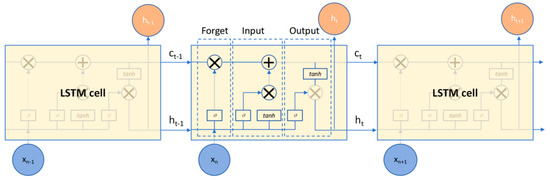

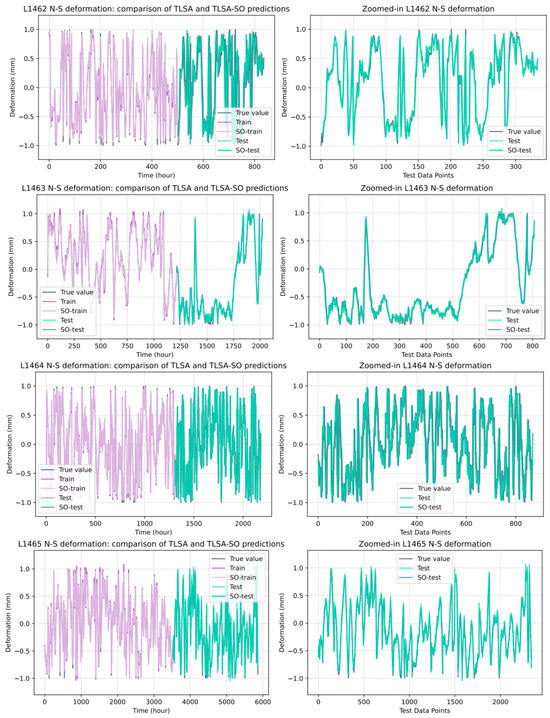

To assess the generalization ability of the TLSA-SO model based on data from different monitoring sites, this study conducted validation experiments at different stations simultaneously and at the same station at different times. These experiments aimed to test the model’s applicability and accuracy at different locations, as well as its ability to predict changes in background noise over time, thus validating its reliability and usefulness. The validation experiment mainly compares the prediction results of the TLSA and TLSA-SO models, using the N-S direction component as an example of data recorded on the same day. The performance of stations L1462–L1465 in the training and test sets is compared in Figure 9. In the figure, the true value is the real monitoring data, train is the prediction result of the TLSA network training set, test is the TLSA model test set prediction data, so-train is the optimized TLSA-SO training set prediction result, and so-test is the TLSA-SO network test set prediction data. Observing the graphs of the prediction results shows that both TLSA and TLSA-SO are consistent with the long-term trend of the monitoring data. This verifies the model’s ability to capture the long-term trend of complex time-series data. Notably, the so-test curve is much closer to the real monitoring data curve, indicating the model’s accuracy and sensitivity in predicting transient fluctuations in real values. Even in regions of significant data fluctuation, the predicted values of TLSA-SO remain in close agreement with real values, demonstrating the accuracy of the un-optimized TLSA model.

Figure 9.

Different model predictions for L1462–L1465 at the same time.

4.4. Analysis of the Strengths of the Model and Room for Improvement

The TLSA-SO deep learning model, which is the focus of this study, offers clear benefits over traditional single-network prediction methods for vibration prediction at cave temple cultural heritage sites. Firstly, the model’s key hyperparameters are optimized using the snake optimization (SO) algorithm, improving its prediction efficiency and accuracy. Compared with traditional methods, the TLSA-SO model can better capture complex ground vibration signals and long-term background noise trends, thus achieving higher prediction accuracy. Additionally, the model’s deep learning architecture incorporates time convolution networks (TCNs), long short-term memory networks (LSTMs), and self-attention mechanisms. This makes full use of multidimensional time-series data, further enhancing the model’s ability to monitor environmental vibrations at cultural heritage sites such as cave temples. The advantages of this model extend beyond ground vibration monitoring and have strong potential for cross-domain applications. It excels in capturing long-term dependencies, sudden fluctuations, and complex data patterns and can be extended to other seismic-monitoring and prediction domains (e.g., deformation and ground shaking). Zhang et al. (2025) [64] studied how earthquake stress affects underground system structures. They found that grotto temples in similar geological environments have special characteristics and protection needs. Wang et al. (2025) suggested a new way of predicting how land will deform using InSAR IPIM and explained how it can be used in different situations to show how the prediction model can be used in more places [65]. We believe that this model has shown very good performance in detecting long-term changes, sudden jumps, and complicated data patterns and can be used in other earthquake-monitoring (deformation, seismic motion) and prediction areas.

Despite the fact that this model performs well in terms of prediction accuracy, its current primary focus is on predicting seismic background noise in grotto temples, with the fusion of accidental earthquake events and other accidental vibration data not yet being given full consideration. Consequently, future research endeavors should integrate a more extensive array of seismic waveform data for analysis and model design, thereby enhancing the stability and comprehensiveness of prediction models. In the context of ongoing technological development, there is a necessity to enhance the capabilities of models in data fusion and multi-dimensional feature extraction. Furthermore, the model should be integrated into the earthquake-monitoring system with all possible expediency, with alerts to be issued through real-time waveform comparison in order to enhance the comprehensiveness of rock damage risk assessment and the scientificity of protection decisions.

5. Conclusions

This paper uses the background noise recorded by seismometers in the Grotto Temple study area as its research subject. It proposes the TLSA-SO deep learning model and verifies the validity and accuracy of the prediction network model. It does this by taking the background noise data recorded by seismometers in the Grotto Temple study area as an example. The model accurately simulates and predicts the long-term behavioral changes in the background noise in the study area. The conclusions are as follows: (1) screening, down-sampling and other cleaning processes applied to the original dataset can effectively simplify the computation process, shorten the computation time, and ensure that the constructed model successfully discovers underlying data trends. (2) The TLSA-SO time-series prediction network is innovatively applied to the study of seismic background noise changes in the Grotto Temple study area to reflect environmental changes. After being compared with LSTM and TLSA network models, it was found that the prediction accuracy of the TLSA-SO network was significantly improved, with accuracy levels reaching 0.99. This fully demonstrates the excellent performance of the TLSA-SO model in predicting background noise behavior and also proves that the PSO algorithm significantly improves the performance of the prediction network. (3) This study looks at the Yungang Grottoes to come up with a new way to check the environment and protect the grottoes. This method can be used for similar cultural heritage sites, based on how similar they are to each other.

Author Contributions

Y.L.: Directed the research and revised the manuscript critically. N.Z.: Conceived the methodology, wrote the manuscript, and performed experimental validation. W.Y.: Prepared the datasets. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Research Program of Taiyuan Continental Rift Dynamics National Field Scientific Observation and Research Station (grant number NORSTY2023-07), the Spark Program of Earthquake Technology of CEA (XH23007YA) and was supported by the Basic Research Program of Shanxi Province (grant number 202403021221339), the Spark Program of Earthquake Technology of CEA (XH23008YA).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Information Center of Shanxi Earthquake Agency for their robust platform support, which greatly facilitated the data processing and analysis presented in this study. We also extend our deep appreciation to the Shanxi Mine Seismology Monitoring and Research Center for providing critical data resources and technical assistance, which were indispensable for the success of this research. Their expertise and collaboration significantly enhanced the quality and reliability of our findings. Furthermore, we acknowledge the dedication of all colleagues and partners who contributed to this work through insightful discussions and constructive feedback. This research would not have been possible without their unwavering support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pei, Q.; Liu, H.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, J.; Li, W.; Wang, Y. Research on Earthquake Risk Assessment Methods and Prevention-Control Countermeasures for Complex Disaster-Bearing Structures in Cave Temples—A Case Study of the Maijishan Grottoes. Res. Conserv. Cave Temples Earthen Sites 2024, 3, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Wang, X.; Meng, J.; Ma, X.; Jiang, X.; Wan, L.; Yan, H.; Fan, Y. Infiltration Assessments on Top of Yungang Grottoes by Time-Lapse Electrical Resistivity Tomography. Hydrology 2022, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wu, R.; Li, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhang, Z.; Hokoi, S.; Su, B. Impact of Opening the Entrance on Cave Temple Murals in Different Climate Zones for Preventive Conservation. Npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, Q.; Lin, W.; Gao, W. Rainfall Influence and Risk Analysis on the Mural Deterioration of Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes, China. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Silk Road Ancient Site Protection. Chin. Cult. Herit. 2004, 3, 118–122. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Chen, J. Current Situation and Development Analysis of Chinese Grotto Temple Protection. Cult. Southeast 2018, 6–14, 127–128. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, S. Study on the ground motion characteristics of the Mogao grottoes in Dunhuang. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou Institute of Seismology, China Earthquake Administration, Lanzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Huang, Z.; Gong, A.; Ba, W. Seismic hazard risk assessment for the immovable cultural relics: The national key cultural relics protection units of cave temples and stone. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 59, 449–455. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Shi, Z.; Lu, J.; Zhu, R. Research on earthquake disaster risk assessment methods for grotto temples: A case study of Yungang Grottoes. Ind. Archit. 2024, 54, 230–239. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B. Emergency response measures for stone grottoes affected by earthquakes. Chin. Cult. Herit. 2021, 4, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, C.; Zhang, L. Seismic risk evaluation method for Buddhist stone cave temples. Build. Cult. 2013, 104–107. [Google Scholar]

- Larose, E.; Carrière, S.; Voisin, C.; Bottelin, P.; Baillet, L.; Guéguen, P.; Walter, F.; Jongmans, D.; Guillier, B.; Garambois, S.; et al. Environmental Seismology: What Can We Learn on Earth Surface Processes with Ambient Noise? J. Appl. Geophys. 2015, 116, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmandt, B.; Gaeuman, D.; Stewart, R.; Hansen, S.M.; Tsai, V.C.; Smith, J. Seismic Array Constraints on Reach-Scale Bedload Transport. Geology 2017, 45, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.L.; Dietze, M. Seismic Advances in Process Geomorphology. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2022, 50, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtin, A.; Hovius, N.; Turowski, J.M. Seismic Monitoring of Torrential and Fluvial Processes. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2016, 4, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allstadt, K.E.; Matoza, R.S.; Lockhart, A.B.; Moran, S.C.; Caplan-Auerbach, J.; Haney, M.M.; Thelen, W.A.; Malone, S.D. Seismic and Acoustic Signatures of Surficial Mass Movements at Volcanoes. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2018, 364, 76–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, V.H.; Tsai, V.C.; Lamb, M.P.; Ulizio, T.P.; Beer, A.R. The Seismic Signature of Debris Flows: Flow Mechanics and Early Warning at Montecito, California. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 5528–5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, M.; Walter, F.; Wenner, M.; Zhang, Z.; McArdell, B.W.; Hibert, C. Machine Learning Improves Debris Flow Warning. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL090874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Tian, C.; Song, D.; Liu, X.; Wang, E. Disaster Process and Multisource Information Monitoring and Warning Method for Rainfall-Triggered Landslide: A Case Study in the Southeastern Coastal Area of China. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 2535–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Song, S.; Wu, F.; Cao, C.; Ma, M.; Wang, S. Research on the Spatiotemporal Evolution of Deformation and Seismic Dynamic Response Characteristics of High-Steep Loess Slope on the Northeast Edge of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Fan, J.; Zhou, Q.; Gu, D.; Tian, Y. A Spatiotemporal Casualty Assessment Method Caused by Earthquake Falling Debris of Building Clusters Considering Human Emergency Behaviors. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 117, 105206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Mechanism and Early Warning of Debris Flows Triggered by Seismic Motion: A Case Study of the Bailong River Basin. Ph.D. Thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. Parameter Identification and Rapid Damage Assessment of Bridge Clusters Under Strong Seismic Actions Based on Monitoring Data. Ph.D. Thesis, Tongji University, Shanghai, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. Research on the Inversion Method of Source Energy Field of Microseismic Monitoring in Mines and Its Application. Master’s Thesis, Zhongyuan University of Technology, Zhengzhou, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. Micro-vibration and Microseismic Signal Monitoring. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M. Wang Meiyong in Gansu: How Technology Assists the Protection of Grottoes. China Daily, 16 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Denolle, M.A.; He, B. A Multitask Encoder–Decoder to Separate Earthquake and Ambient Noise Signal in Seismograms. Geophys. J. Int. 2022, 231, 1806–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havskov, J.; Alguacil, G. Seismic Noise. Instrum. Earthq. Seismol. 2004, 22, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, S.; Guo, Z. S-wave velocity of the crust in Three Gorges Reservoir and the adjacent region inverted from seismic ambient noise tomography. Chin. J. Geophys. 2013, 56, 4113–4124. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herak, M.; Herak, D. Continuous Monitoring of Dynamic Parameters of the DGFSM Building (Zagreb, Croatia). Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2010, 8, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton, J.F. The Observed Wander of the Natural Frequencies in a Structure. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2006, 96, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainsant, G.; Larose, E.; Brönnimann, C.; Jongmans, D.; Michoud, C.; Jaboyedoff, M. Ambient Seismic Noise Monitoring of a Clay Landslide: Toward Failure Prediction. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2012, 117, 2011JF002159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainsant, G.; Jongmans, D.; Chambon, G.; Larose, E.; Baillet, L. Shear-wave Velocity as an Indicator for Rheological Changes in Clay Materials: Lessons from Laboratory Experiments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, 2012GL053159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G.E.P.; Jenkins, G.M.; Reinsel, G.C. Time Series Analysis Forecasting and Control, Revised ed.; Holden Day: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1976; Volume 31, pp. 238–242. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, N.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y. Wind Speed Forecasting Based on the Hybrid Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition and GA-BP Neural Network Method. Renew. Energy 2016, 94, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, S.; Fujiwara, Y.; Iwamura, S. Preventing Gradient Explosions in Gated Recurrent Units. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Zhou, R.; Geng, Z.; Chen, K.; Wei, Q. Production Prediction Modeling of Industrial Processes Based on Bi-LSTM. In Proceedings of the 2019 34rd Youth Academic Annual Conference of Chinese Association of Automation (YAC), Jinzhou, China, 6–8 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jaidee, S.; Pora, W. Very Short-Term Solar Power Forecasting Using Genetic Algorithm Based Deep Neural Network. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology, Saratov, Russia, 7–8 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, M.; Zheng, X.; Imran, M.; Shoaib, M. Data-Driven Prognosis Method Using Hybrid Deep Recurrent Neural Network. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 93, 106351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Gao, J.; Chen, H.; Gao, Z.; Huang, Y.; Chen, J.; Cao, Y.; Wang, J. Semi-supervised seismic attenuation compensation method based on GRU dominated deep netural network. Chin. J. Geophys. 2023, 66, 2997–3010. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Melgar, D.; Sahakian, V.; Searcy, J.; Lin, J.-T. Learning Source, Path and Site Effects: CNN-Based on-Site Intensity Prediction for Earthquake Early Warning. Geophys. J. Int. 2022, 231, 2186–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Guan, F.; Lv, C.; Huang, Y. Ultra-Short-Term Multi-Step Wind Power Forecasting Based on CNN-LSTM. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2021, 15, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, B.; Bafti, A.G.; Kamangir, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wright, D.B.; Franz, K.J. A Novel Attention-Based LSTM Cell Post-Processor Coupled with Bayesian Optimization for Streamow Prediction. J. Hydrol. 2021, 601, 126526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Tian, H.; Zeng, X.; Xia, X.; Hu, X.; Pang, B. Landslide Deformation Analysis and Prediction with a VMD-SA-LSTM Combined Model. Water 2024, 16, 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, D.; Lin, G.; Tian, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Prediction of Mechanical Characteristics of Shearer Intelligent Cables under Bending Conditions. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. Trellis Networks for Sequence Modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.06682. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Shu, Q.; Ding, F.; Liu, F.; Jiang, S.; Wu, W. Incorporated Flexible Load Forecasting Based on Non-Intrusive Load Monitoring: A TCN-Based Meta Learning Approach. Front. Energy Res. 2025, 13, 1519053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsel, O.E.; Yamada, S.S. Comparative Study of Machine Learning Models for Stock Price Prediction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.03156v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Jun, Y.; Yulei, R.; Boris, P. A Deep Learning Framework for Financial Time Series Using Stacked Autoencoders and Long-Short Term Memory. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180944. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, T.; Krauss, C. Deep Learning with Long Short-Term Memory Networks for Financial Market Predictions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 270, 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Girshick, R.; Gupta, A.; He, K. Non-Local Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Bao, Y.; Fang, Z.; Lu, H. Dual Attention Network for Scene Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Goodfellow, I.; Metaxas, D.; Odena, A. Self-Attention Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Huang, L.; Guo, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. OCNet: Object Context for Semantic Segmentation. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 2375–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, I.; Zoph, B.; Le, Q.; Vaswani, A.; Shlens, J. Attention Augmented Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1904.09925v5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, F.A.; Hussien, A.G. Snake Optimizer: A Novel Meta-Heuristic Optimization Algorithm. Knowledge-Based Syst. 2022, 242, 108320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, R.; He, Y.; Zhang, C.; Geng, J. VMD and SO-optimized SVM for Fault Diagnosis of Fiber-Optic Composite Submarine Cable. Electron. Meas. Technol. 2023, 46, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J. A SO-CNN-based Visible Light Indoor Positioning Optimization Method. Electron. Technol. 2024, 64, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Zhang, H.; Kang, M.; He, R.; Gao, L.; Gao, J. High-Resolution Lithospheric Velocity Structure of Continental China by Double-Difference Seismic Travel-Time Tomography. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2019, 90, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zhan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Peng, S. Fault Extension Characteristics of the Middle Section of Shanxi Graben System and the Seismogenic Environments of the Hongdong and Linfen Earthquakes. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, R.; Ji, L.; Zhao, C. Ground Deformation and Fissure Activity in Datong Basin, China 2007–2010 Revealed by Multi-Track InSAR. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2019, 10, 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assie, K.R.; Wang, Y.; Tranos, M.D.; Ma, H.; Kouamelan, K.S.; Brantson, E.T.; Zhou, L.; Ketchaya, Y.B. Late Cenozoic Faulting Deformation of the Fanshi Basin (Northern Shanxi Rift, China), Inferred from Palaeostress Analysis of Mesoscale Fault-Slip Data. Geol. Mag. 2022, 159, 2306–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, Z.; Dai, L.; Wang, S.; Shi, C. The Incompatible Deformation Mechanism of Underground Tunnels Crossing Fault Conditions in the Southwest Edge Strong Seismic Zone of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: A Study of Shaking Table Test. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 197, 109482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Fang, Z.; Li, X.; Kang, J.; Wei, Y.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T. Research on the Prediction Method of 3D Surface Deformation in Filling Mining Based on InSAR-IPIM. Energy Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2401–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).