Abstract

As the global urbanization process accelerates, rural settlements in China are facing the challenges of rural hollowing and widening urban–rural disparities. The establishment of the national scenic area system has made scenic settlements a primary direction for tourism development. However, industrial transformation has led to significant restructuring of the human–land relationship and the spatial functions of these settlements, resulting in issues such as over-tourism, ecological degradation, and cultural loss. This paper focuses on the Mosuo settlements around Lugu Lake, selecting nine villages, including Gesha Village, Wuzhiluo Village, and Daluoshui Village, to explore the formation and expression of Mosuo spatial concepts. Through spatial measurement, area statistics, and the analysis of development paths, the core of the research is to propose that “there is consistency between conceptual order and spatial form,” revealing the multi-dimensional evolutionary mechanism of Mosuo settlement spatial morphology under the intertwining of traditional concepts, market logic, and institutional policies, providing a replicable Chinese reference for global cultural heritage rural areas.

1. Introduction

In recent years, with the acceleration of global urbanization, many regions are experiencing problems such as rural hollowing and widening urban–rural disparities [1]. In this context, China’s rural revitalization strategy, through differentiated policy experiments and land system innovations, is driving the restructuring of settlement spaces [2]. Since the establishment of the national scenic area system, more than 1000 scenic areas at various levels have been announced, of which over 70% contain rural settlements [3]. Tourism has become the main development direction for scenic settlements. Under drastic industrial transformation, the original human–land relationships and spatial functional patterns of settlements face significant transformation and restructuring. At the same time, due to their resource endowment and the particularity of management and construction, their restructuring and development processes differ significantly from ordinary rural areas [4]. It is worth noting that this restructuring is deeply embedded in the globalized tension field: on the one hand, international tourism standards, such as the European Landscape Convention, has reshaped local spatial aesthetics [5]; on the other hand, agricultural product trade competition under the WTO framework has forced rural areas to shift to the service industry [6], leading to an intensified contradiction between cultural commercialization and ecological protection.

Meanwhile, due to the comprehensive influence of various factors such as the natural environment and socio-culture, the scale, form, and spatial layout of rural settlements in China have been continuously evolving. In recent years, academic circles have paid increasing attention to research on the spatio-temporal evolution of rural settlements, driving factors, and how to optimize spatial layout, which has become a hot topic of widespread concern [7]. The core limitations of current research are as follows: the disconnection between spatial concepts and morphological evolution, as existing research often focuses on quantitative analysis of settlement spatio-temporal patterns or isolated discussions of cultural symbols, but fails to reveal how local residents’ spatial concepts dynamically drive morphological evolution; the absence of policy logic, as most studies overlook the shaping of settlement spatial concepts by China’s “central planning-local experimentation” mechanism; the dilemma of theoretical dependence, as spatial analysis often applies Western classical theories, failing to integrate the local experience of China’s small farmer transformation; and insufficient international dialogue, as experiences such as the outcome of the EU’s “Landscape Character Assessment” (LCA) system have not been effectively localized [8]. The core of these disconnections lies in the failure to reveal how spatial concepts drive and respond to the evolution of settlement spatial morphology. The recently proposed “new materialism” theory in geography emphasizes that spatial concepts need to be dynamically concretized through material practices [9], which provides a new perspective for this study to analyze the ritual expression of the “cohabitation of humans and gods” concept and the evolution of house forms.

Currently, many scenic area settlements face problems such as over-tourism, ecological degradation, and cultural loss due to improper transformational development. At this stage, the relevant research mainly focuses on the settlement system level, or emphasizes the spatio-temporal evolution of settlement patterns [10] and the analysis of influencing factors, but rarely approaches these from the perspective of “the generation and expression of spatial concepts,” leading to a lack of cultural adaptability in protection practices. Therefore, this study proposes a core question: how does the spatial morphology of the Mosuo settlements evolve in the context of tourism development? How do their traditional concepts of human–god cohabitation participate in this process and form dynamic interactions with spatial morphology?

This paper selects representative Mosuo settlements around Lugu Lake as research objects, including Gesha Village, Wuzhiluo Village, Daluoshui Village, and nine other villages. This study is based on the practical wisdom of China’s rural policies and integrates critical lessons learned from a cross-national perspective [11], incorporating theories of dwelling and corporeality into the formation and expression of Mosuo spatial concepts, analyzing the interactive mechanisms of settlement spatial composition elements, changes in living spaces, and the evolution of spatial concepts, and revealing the patterns of three types of evolutionary modes. This research will provide a “concept-form collaborative” sustainable development path for scenic area settlement protection and will contribute a Chinese reference to the theory of global cultural landscape evolution.

2. Research Objects and Methods

2.1. Research Objects

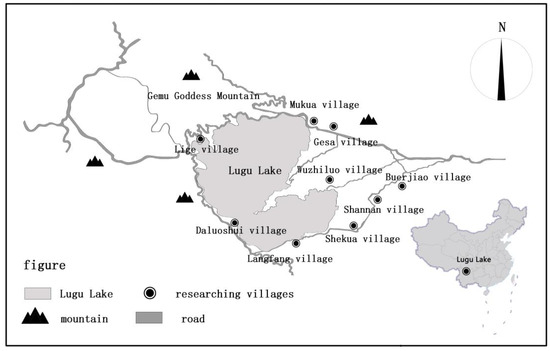

To better understand the research background, a map of the study area and sample villages is provided below, Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The distribution of the study area and sample villages.

The Mosuo people originated from the ancient Qiang people in Qinghai. During the Warring States period, the ancient Qiang people in eastern Qinghai Province continuously moved south to avoid the threat of the Qin State. Along the way, “descendants separated, each forming their own kind, going wherever they pleased.” [12]. They entered the Lugu Lake area, centered in Yongning, during the late Eastern Han Dynasty and the Shu Han period, and gradually settled down. “The Book of Later Han · Biography of the Southwestern Yi Minorities” records that the Mosuo people’s concentrated living areas were in Yanyuan County, Muli County, Yanbian County in Sichuan, and Ninglang County in Yunnan [13].

Today, the Mosuo people mainly reside in the Lugu Lake area at the border of Yanyuan County in Sichuan Province and Ninglang County in Yunnan Province. In the process of integrating with the new environment on the basis of Qiang culture, they have gradually formed unique cultural characteristics. These cultural characteristics interact with each other, jointly forming the Mosuo cultural complex and establishing a settlement structure where humans and gods coexist. However, since the 1990s, tourism in the Lijiang area has developed rapidly, and a large number of tourists have poured into the Lugu Lake area, leading to rapid changes in the Mosuo settlement space.

2.2. Research Methods

Unlike existing research that often remains at the level of static patterns or interviews, this paper constructs a “literature-physical object-sequential area” three-dimensional cross-validation framework: extracting functional areas such as homesteads, cultivated land, beliefs, public spaces, and commercial areas at two time points in nine villages, calculating the evolutionary gradient and the “embodied” spatial concepts of the Mosuo people, and conducting a dual-axis comparison, for the first time quantitatively depicting the continuous trajectory of concept–form coupling. The basic research data is based on the Mosuo cultural anthropology survey led by Yunnan University in 2002, with the participation of the Department of Architecture of Kunming University of Science and Technology, and relevant materials from the independently funded Mosuo human settlement environment research in 2023. It systematically integrates the historical literature and field survey data. At the level of literature research, it mainly studies historical documents, academic monographs, government documents, and oral historical materials, focusing on collating local gazetteers such as “Yongning Prefecture Annals” and Qing Dynasty maps collected by the Yunnan Provincial Library, combined with Mosuo residential image data since the 1980s, to analyze the original settlement space around 2000.

The research objects are 9 representative villages around Lugu Lake (including Gesa Village, Wuzhiluo Village, etc.), selected based on a stratified principle of geographical gradient, tourism intensity, and cultural preservation status: geographical stratification covers the lakeside type (distance from lake < 1 km, e.g., Daluoshui Village), the transitional type (1–3 km, e.g., Wuzhiluo Village), and the foothill type (>3 km, e.g., Bu’erjiao Village); tourism intensity stratification is based on the density of guesthouses; and cultural preservation stratification is based on the completeness rate of grandmother houses/hearths (traditional type > 90%, transitional type 50–90%, mutated type < 50%), ensuring the sample covers the entire evolutionary spectrum.

The research used drone imagery combined with on-site measurements to obtain data, precisely surveying the research objects, and establishing spatial data including the building age, structural type, and functional evolution. After calculating the geometric area of each functional area using ArcGIS 8.10, a “functional area time series matrix × conceptual indicator matrix” was constructed, and a principal component-hierarchical clustering (PCA-HCA) model was used to identify the concept–function collaborative paths of three generations of settlements, providing quantitative basis for subsequent mechanism analysis.

3. The Mechanism of the Formation of the Mosuo Spatial Concept

3.1. Formation of Spatial Concepts

The formation of spatial concepts needs to be traced back to philosophical epistemology. Kant, in “Critique of Pure Reason,” proposed the transcendental nature of space, believing that “space itself is the framework in which all persistence is possible.” Its persistence needs to be connected with “timelessness” through the concept of “simultaneity.” This process involves complex deductions: from simultaneity to timelessness, then to persistence, and finally forming the concept of “persistent space.” [14] Heidegger, on the other hand, subverted traditional cognition from an existential perspective, proposing in “Being and Time” that space “is subordinate to temporality,” emphasizing that space acquires “orientation” and “distancing” characteristics through the existential activities of Dasein. In his later “Contributions to Philosophy (From Enowning),” he placed space–time at the equal level of “enowning,” giving space a dynamic dwelling meaning [15]. Descartes’ view of space, inheriting the Aristotelian tradition, equated space with the extension of objects, denying the atomistic concept of “void,” which directly influenced the modern relativistic view of space–time [16].

For settlement spaces, various concepts within settlement culture influence their formation [17]. In Africa, the concentric circular settlements of the Maasai strengthen the hierarchical order of “herd-family-tribe” [18]; the terraced villages of the Dogon imitate the body of the creation god Nommo according to “gender + orientation” mathematics, achieving mythical concretization [19]; the courtyards of the Zulu are centered on ancestral spirit poles, with downhill entrances forming a binary space [20], though their concentric circle model is archaeologically controversial. In South America, the Kayapo ring village is centered on the men’s house [21], with radial longhouses facing the “world’s eye” plaza; the Quechua kancha quadrangle in the Andes symbolizes the “upper-middle-lower” three-realm cosmos with three-body houses [22]. In Asia, Bali practices “heaven-human-earth” harmony through the “mountain-sea” axis and Tri Mandala three-segment division [23]. Polynesian settlements in Oceania embrace ritual lawns with their residences [24], aligning the chief’s house orientation with navigational star charts. The Mosuo people’s lives in the Lugu Lake area, influenced by complex terrain and diverse climates, have also formed the unique Mosuo culture and shaped unique spatial concepts.As shown in Table 1, the three spatial components of Mosuo culture are clearly categorized.

Table 1.

Three elements of Mosuo space culture, source: ⟪Atlas of Mosuo Intangible Cultural Heritage in Lugu Lake⟫.

First, Mosuo villages are mostly built against mountains, located at the foot of mountains, not occupying flat cultivated land [25]. The Mosuo people have a strong natural awareness of restraining greed; they do not occupy natural resources but engage in farming, raising livestock, and hunting according to the terrain characteristics of mountains and valleys, forming a dispersed living pattern. This living style integrates each family with the natural environment, reflecting the Mosuo people’s adaptation to and respect for nature. Second, Mosuo religious beliefs play a key role in their concepts. They initially believed in Dabaism and later were influenced by Tibetan Buddhism, forming diverse and complex religious concepts. Nature is regarded as sacred, closely connected with deities and ancestors, and religious ceremonies are held in natural spaces, strengthening the Mosuo people’s spiritual connection with nature.

The marriage and family concepts of the Mosuo people have a profound impact on their beliefs. Mr. Ren Naiqiang believes that the enduring female-centered characteristic is the greatest feature of the ancient Qiang culture in China. “The Qiang people, originated from hunting, had maintained a female-centered social system until before the 8th century AD” [26]. Therefore, the Mosuo people, who have a close relationship with the Qiang people, inherited the characteristics of Qiang culture. The matrilineal family system and the practice of walking marriage have shaped the Mosuo people’s cognition and utilization of space. The grandmother’s house, as a unique spatial structure, and the practice of walking marriage give the Mosuo family space a certain distinctiveness, or in other words, the space conveyed by the Mosuo grandmother’s house reflects more of a gender-balanced space [27].

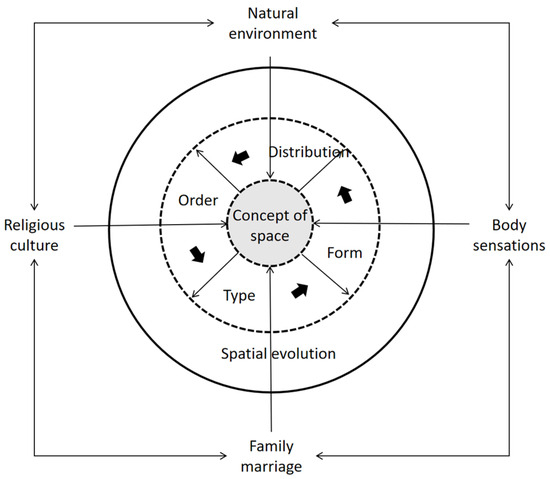

Starting from the unique cognitive position of the body, Polanyi further vividly describes auxiliary consciousness as “indwelling” or “internalization.” The mind indwells in the body, and in knowing external things, our body plays an instrumental role, and we only have auxiliary consciousness of our own body [28]. The Mosuo people have well integrated their bodies into their environment; their concepts are embodied through the configuration and material expression of space, and the organization and order of space further strengthen the impression of these concepts in people’s minds. In the Lugu Lake area, the unique natural environment, the influence of Qiang culture, and the integration of diverse cultures together shape the Mosuo people’s unique spatial conceptual system (Figure 2), forming a unique settlement space structure where humans and gods coexist.

Figure 2.

The mechanisms of the formation of spatial concepts among the Mosuo people.

3.2. Expression of Spatial Concepts

The Mosuo people’s spatial concepts construct emotions and cognitions related to specific spaces. They visit specific locations and hold traditional ritual activities, deepening their cognition and emotional connection with specific spaces through these bodily experiences. Every year on the 25th day of the seventh lunar month, the Mosuo people hold a grand mountain circumambulation activity, which the Mosuo call “Gemu Gu,” meaning touring Lion Mountain and sacrificing to the Goddess Gemu [29]. This is a solemn Gemu Goddess Celebration Day, or Mountain Festival. People burn incense, hang prayer flags, and kowtow to worship the mountain god and lake god during the mountain and lake circumambulation. The sacred mountain is a symbol of Mosuo nature worship. Mosuo villages are generally located near the foot of the mountain and develop linearly along the mountain foot, so as to protect the spatial pattern of the sacred mountain from being damaged.

The settlement pattern is “a form of dwelling coordinated by a group between the natural landscape and social environment in which they are located.” [30]. When Mosuo people walk in the village, the sound of their footsteps, the sound of wind blowing past their ears, the feeling of sunlight on their skin, etc., become part of their bodily experience within specific places. These sensations, accumulated and repeated over time, gradually form a perception and connection to specific places in the Mosuo people’s cognition and emotions. At the entrances and exits of the settlement and at the intersections of concentrated residential nodes with main roads, the Mosuo people have set up Mani piles. The Mani piles and the surrounding open spaces form a religious area parallel to the sacred mountain, and a settlement space structure where humans and gods coexist gradually takes shape.

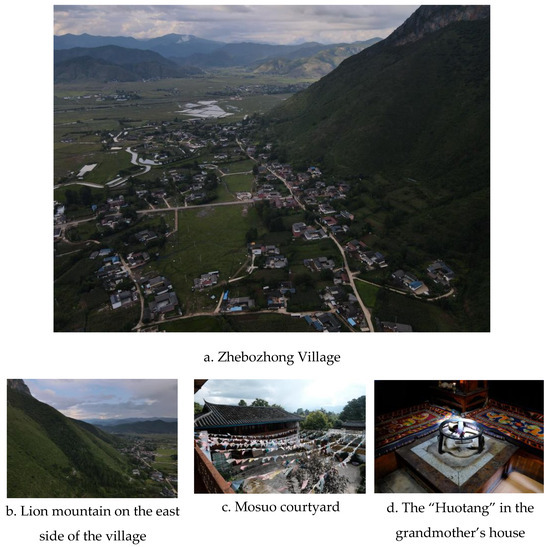

The spatial composition of Zhebozhong Village, located at the foot of the sacred mountain, perfectly fits the description above (Figure 3). Its spatial composition mainly includes the following: the sacred mountain to the east, the religious space formed by the Mani pile at the village entrance, the residential space extending linearly along the foot of the mountain, and the production spaces distributed around the settlement. The religious space is primary, and the living and production spaces are secondary, forming a settlement space structure where humans and gods coexist.

Figure 3.

A traditional Mosuo settlement.

“The ancestors of my family are the greatest gods in our village. Where the sun rises is the East, and there is a lion there, with a god riding on it. The god of the West is called ‘Duoba Kahabaru,’ riding a yak. There is a god riding a tiger in the South, and a god riding a green peacock in the North.” This is a section from the scripture recited by the Daba during the fire-lighting ceremony when a new house is built, reflecting the relationship between the orientation system and spatial order [31]. From the quoted Daba scripture, it can be seen that the Mosuo people’s spatial concepts also influence and determine the orientation and spatial pattern of Mosuo residential courtyards.

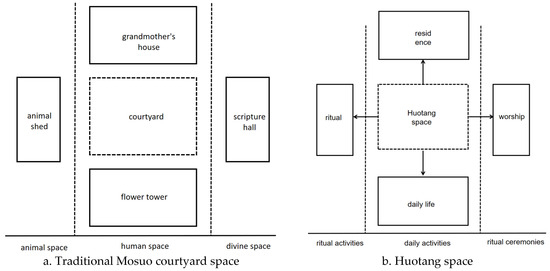

In addition, the grandmother’s house holds an important position in the matrilineal family (Figure 4). The hearth space in the grandmother’s house also holds an important position in the Mosuo people’s spiritual space. As Vitruvius described, “After the discovery of fire, primitive people first gathered around it, and then formed councils… In their first council, they proposed the idea of building huts…” [32]. As Vitruvius described, primitive people sat by the fire, and thus houses began to appear. In the beginning, houses were not only places for bodily dwelling but also places for spiritual solace.

Figure 4.

A traditional Mosuo courtyard space and Huotang space.

For the Mosuo people, fire not only provides a sense of safety and warmth but also serves as a medium for communication between the Mosuo people and deities. The space centered around the hearth in the main room of the main house is a realistic reflection of the Mosuo people’s concept of “cohabitation of humans and gods.” [33]. Mosuo matrilineal extended families live in one dwelling, no matter how large, and they are not allowed to leave the family or split up. This forms a highly independent space with the hearth as its core.

In summary, traditional Mosuo space is a manifestation of concepts under the comprehensive influence of its society, culture, and natural environment. The Mosuo people form close connections with specific places through physical activities such as dwelling, belief, and rituals. This cognitive and emotional connection is profoundly reflected from the settlement space to the living space. Understanding the generation and expression of Mosuo spatial concepts plays an important guiding role in understanding the Mosuo people’s unique “cohabitation of humans and gods” spatial composition.

4. Evolution of Mosuo Space

4.1. Spatial Changes in the Gesa Village

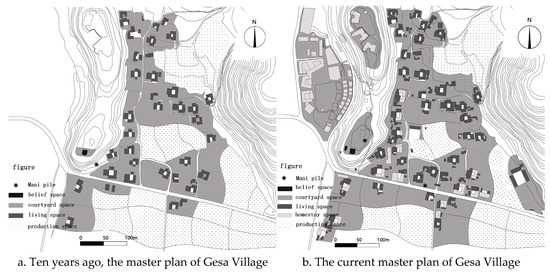

Gesha Village is located in Lugu Lake Town, Sichuan Province, and is a natural village under Mukua Village. In 2006, with the opportunity of the Winter Tourism Conference held in Liangshan Prefecture, Sichuan Province, the first government reception hotel in Sichuan Hucao Lake began to be built near the ancient village. As one of the most well-preserved ancient villages in the Hucao Lake area, Gesha Village was also developed as an auxiliary tourist facility for the hotel [34]. Taking Gesha Village as an example (Figure 5), by calibrating CAD data with the UTM Zone 47N projection system and converting it to a Shapefile to calculate the geometric area, between 2013 and 2023, the proportion of homesteads in Gesha Village increased from 33.75% to 52.71% (+18.96%), and cultivated land decreased from 29.96% to 21.64% (−8.32%); the building space expanded simultaneously, with Gesha Village adding a “guesthouse” category (accounting for 3.67% in 2023), and its building-related space (buildings + guesthouses) increasing from 2.20% to 7.41%; the area of religious space remained unchanged (193 m2), but due to the expansion of other spaces, its proportion stagnated, becoming a marginalized cultural symbol (Table 2). The spatial structure shifted from “homestead-cultivated land” binary dominance to a “homestead-building” composite type, reflecting a systemic shift in land use from agriculture to residential and economic functions.

Figure 5.

A spatial comparison of Gesa Village settlements (2013 vs. 2023).

Table 2.

Statistical table of settlement spatial changes in Gesa Village (2013–2023).

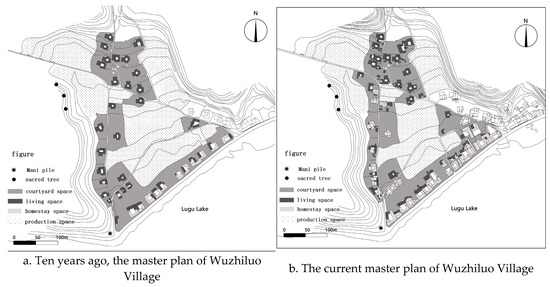

4.1.1. Changes in Settlement Spatial Composition

Ten years ago, the local government, in order to develop tourism, added public activity spaces into the core of the village. In traditional Mosuo settlements, public activity spaces like dance venues would not appear within the settlement. Today, the added public activity spaces have not thrived but instead have been abandoned. The settlement is still composed of belief, living, and production spaces, and basically maintains its original proportions. Due to changes in production and lifestyle, the area of belief space and living space has increased, while traditional production space has relatively decreased (Figure 6). Tourism development is directly reflected in the creation of “guesthouse” space in Gesha Village (+3.67%) and the growth of building space (+5.21%), coupled with a reduction in cultivated land and the expansion of homesteads, indicating the replacement of traditional agricultural space by tourism services and the commercialization of residential space. The Mosuo people’s spatial concepts show an “economic-oriented” evolution. Although belief space is preserved, its static proportion (<0.1%) reveals that traditional culture is in a subordinate position in spatial planning; the significant decrease in cultivated land proportion reflects the shift in livelihood patterns from agricultural dependence to tourism economy.

Figure 6.

A spatial composition and proportion comparison of Gesa Village settlements (2013 vs. 2023).

4.1.2. Changes in Courtyard Space

Ten years ago, villagers, in order to create a clean and sanitary environment, renovated their courtyards, dividing the courtyard into an inner and outer courtyard, and separating human and animal spaces. Within the homestead, the traditional grandmother’s house, scripture hall, flower house, and animal pens of the Mosuo extended family still revolved around the inner courtyard, forming a highly independent space (Figure 7). Nowadays, newly built residences are linearly arranged along the road, and indoor spaces are re-divided according to their functions: the part of the building along the road serves as a shop; the original animal sheds are removed, and a new two-story wooden house is built as a guesthouse space, while the original flower house and scripture hall spaces are merged. Within the homestead, the grandmother’s house, scripture hall, and flower house spaces still exist, the inner courtyard space has become a shared space for Mosuo people and tourists, and the original highly independent space has begun to become open.

Figure 7.

A comparison of the spatial composition of courtyards in Gesa Village (2013 vs. 2023).

4.1.3. Changes in Living Space

Ten years ago, in order to increase income, many Mosuo families chose to rebuild or even demolish their flower houses or gatehouses, while the grandmother’s house and scripture hall in the home were preserved in their original traditional style as much as possible, or slightly modified to meet the needs of modern life [35]. Today, the types of Mosuo living spaces have not changed, still maintaining the characteristics of traditional Mosuo extended family living spaces. Due to the changes of the times, the weakening of the “walking marriage” custom, and the development of tourism, the living spaces of Mosuo extended families tend to be concentrated, and the living area has shrunk.

4.1.4. Summary

Gesha Village’s ten-year development shows the characteristics of a second-generation settlement (Table 3): the homestead commercial conversion rate increased by 18.9%, and the proportion of belief space remained at 0.07%, confirming the restraining effect of the Mosuo’s “restraint of greed” concept on spatial commercialization. After ten years of development, Gesha Village presents two types of space that are different from traditional Mosuo settlements. The first type of settlement did not change the original settlement’s spatial composition during its development, only adjusting certain functions or building volumes in the living space to meet the needs of different groups. The second type of settlement generally maintained its original spatial composition during its development, and the settlement space continuously expanded, but it did not occupy the belief space or damage the natural environment. This is because the Mosuo people have a strong natural awareness of controlling greed, believing that “restraint of greed is a virtue and a custom, while indulgence in greed is an evil act.”. The courtyard space area became larger, and the quality of the living space within the homestead continuously improved. The remaining building space was converted into different types according to demand, such as guesthouses or shops. The village did not destroy the original belief space or the natural environment during its development, and the entire settlement still developed along the foot of the mountain and roads, maintaining the spatial characteristics of human–god cohabitation.

Table 3.

A statistical table of the settlement types around Lugu Lake.

4.2. Changes in the Wuzhiluo Villages

Wuzhiluo Village is a natural village located in Boshu Administrative Village on the east bank of Lugu Lake, Sichuan Province. It is favored by tourism due to its location at the beginning of Caohai Lake. Tourism in Wuzhiluo Village began in the late 1990s. With the completion of the Caohai Lake road in 2006, the number of tourism households here has grown to more than 20. Villagers spontaneously formulated rules and models for collective participation in tourism, which largely protected the spatial structure of human–god cohabitation (Figure 8). Through quantitative analysis, the proportion of homesteads in Wuzhiluo Village increased from 43.60% to 56.94% (+13.34%), and cultivated land decreased from 48.90% to 36.91% (−11.99%). The proportion of “buildings” increased from 7.41% to 13.24% (+5.83%). The religious space, as seen in Gesha Village, showed no significant change (259 m2), also becoming a marginalized cultural symbol.

Figure 8.

A comparison of the spatial composition of courtyards in Wuzhiluo Village (2013 vs. 2023).

4.2.1. Changes in Settlement Space Composition

Ten years ago, in order to develop tourism, villagers divided the village land into different attributes, forming a new spatial hierarchy in Wuzhiluo Village: front-end tourism development, middle-level farmland as a buffer, and back-end traditional life. Due to the construction of a series of guesthouses in front of Wuzhiluo, a single tourism public space was added to the composition of the settlement space.

Today, to meet tourist demands, multifunctional and multi-type public spaces continue to emerge, but they still maintain their original spatial planning. The settlement is still composed of belief, living, and production spaces, and basically maintains its original proportional composition. Due to changes in production and lifestyle, the area of the belief space and the living space has increased, while the traditional production space has relatively decreased (Figure 9). Wuzhiluo Village did not show a separate guesthouse category, but its high building growth suggests the hidden penetration of tourism influence. A comparison between the two places shows that tourism development has accelerated the transformation of settlement space from a “belief-agriculture” equilibrium to a “residential-commercial” entity, and traditional spatial concepts have been reshaped under the dominance of economic rationality.

Figure 9.

A comparison of the spatial composition of courtyards in Wuzhiluo Village (2013 vs. 2023).

4.2.2. Changes in Courtyard Space

Ten years ago, due to the earlier development of tourism in front of Wuzhiluo Village, its courtyard space had already evolved into the courtyard model currently seen in Gesha Village. Today, the homestead space in front of Wuzhiluo has new changes. To meet tourists’ demand for living space, the architectural spaces of the scripture hall and flower house were incorporated into the grandmother’s house, replaced by two- to three-story wooden houses as guesthouse spaces (Figure 10). This is due to the natural growth of the population and changes adapting to the development of tourism, leading to a trend of expanding living space volume; the development of living space often shows aggregation, the size of courtyard forms increases, and the spatial scale changes from the previous homogeneity to courtyard forms with small widths and large depths. At the same time, some newly added courtyard forms show weakened enclosure [36].

Figure 10.

A comparison of the spatial composition of the courtyards of Wuzhiluo Village (2013 vs. 2023).

4.2.3. Changes in Living Space

Ten years ago, the living spaces of Mosuo extended families already showed characteristics of concentration, and the living area accordingly shrank. After nearly ten years of tourism development, the number of guesthouses in Wuzhiluo Village has increased from more than 20 to more than 30 today. The development of tourism has continuously compressed the living space of villagers who originally lived in front of Wuzhiluo. However, tourism has driven the economic development of villagers, leading them to continuously return to the back of Wuzhiluo to expand their living space. The grandmother’s house, after continuous renovation, has expanded in area, and its internal structure and construction techniques have also continuously improved.

4.2.4. Summary

Wuzhiluo Village has advanced to a third-generation settlement (Table 3): the guesthouse density reached 34 households/km2, but through a “front-end development—back-end protection” strategy, the proportion of religious space was maintained at 0.10%, reflecting the synergistic mechanism of policy and concepts. After ten years of development, Wuzhiluo Village presents two types of space that are different from traditional Mosuo settlements. The first type of settlement maintained its original spatial composition during its development, and the settlement space continuously expanded, but it did not occupy religious space or damage the natural environment. The second type of settlement adopted a more comprehensive approach in its development, not only changing a single spatial function but also changing various spatial combinations, integrating multiple functional spaces. The settlement space continuously expanded, and the spatial composition underwent significant changes, but it did not occupy religious space or damage the natural environment. Through the transition of public spaces, the integrity of the sacred mountain and mother lake system was protected, and the settlement maintained the unique spatial composition of human–god cohabitation of the Mosuo people.

5. Types of Mosuo Space Evolution

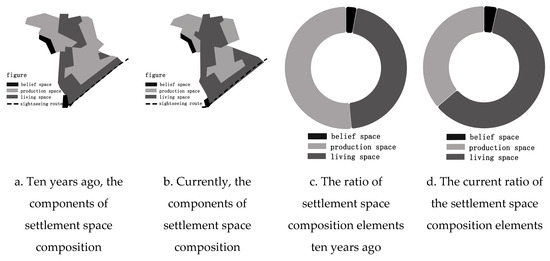

5.1. Discovery and Hypothesis of Types

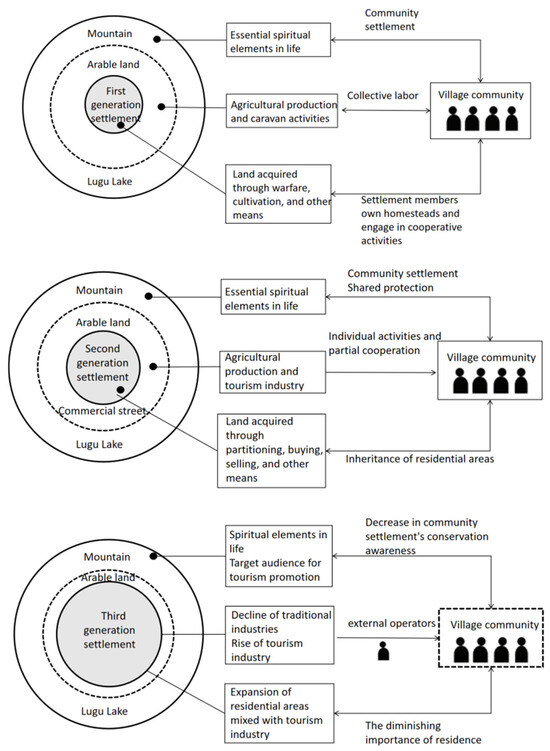

A comparison of Gesha Village and Wuzhiluo Village over the past ten years suggests three evolutionary types that differ from traditional Mosuo space: one type is common to both villages, and the other two types are unique to each village (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

An evolutionary diagram of Mosuo settlement spaces.

The spatial evolution of the two villages shows a long-term dislocation: early on, only Wuzhiluo Village initiated overall restructuring, while Gesha Village focused on residential adjustments; ten years later, Gesha Village followed the path of Wuzhiluo Village, while the latter produced new comprehensive spatial types. Based on this, it is hypothesized that the first, second, and third generations of types evolve progressively. This paper then verifies this hypothesis with the survey results of seven villages around Lugu Lake (Table 3).

According to Table 3, there is only one village, Bu’erjiao Village, with first-generation settlement space characteristics. Shan’nan Village and Shekua Village have second-generation settlement space characteristics, and Mukua Village, Daluoshui Village, Lige Village, and Langfang Village have third-generation settlement space characteristics.

Among the seven surveyed villages, the number of villages with first-generation settlement space types is the smallest, and the number of villages with third-generation settlement space types is the largest. In addition, the spatial type of a village is related to its distance from Lugu Lake. Villages with first-generation settlement space types are farther from Lugu Lake, while villages with second and third-generation settlement space types are closer to Lugu Lake. Furthermore, first and second-generation settlements mostly appear in the Sichuan area of Lugu Lake, while the Yunnan area of Lugu Lake is entirely composed of third-generation settlements.

5.2. Characteristics of Spatial Evolution

The development of a settlement is a long evolutionary process. Factors such as economic development are limiting and lead to unbalanced development [37]. Through field surveys of Mosuo settlements around Lugu Lake, three types of Mosuo settlements were found, confirming the hypothesis of the iterative evolution of these spatial types (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

The three stages of settlement evolution.

First-generation settlements: Small-scale expansion at the original site along the foot of the mountain, maintaining a “residential-production-belief” tripartite pattern, with only minor adjustments to residential volume.

Second-generation settlements: Near main roads or waterfronts, with expanded and improved homestead quality, and some remaining space converted into guesthouses or shops.

Third-generation settlements: Closely adjacent to the lake shore, with high functional complexity, mixed multi-functional spaces, and the introduction of public and shared spaces, with high participation from external operators.

6. Reasons for Mosuo Space Evolution

The evolution of Mosuo settlements is driven by both internal and external mechanisms: villages far from the lake shore show slow internal renewal due to agricultural dependence and policy restrictions; in contrast, those adjacent to the lake shore expand rapidly through tourism capital, forming an externally driven spatial restructuring.

6.1. Endogenous Evolution

The main characteristic of villages undergoing endogenous evolution is that, due to resource and policy disadvantages, they only make minor adjustments within the homestead, maintaining the traditional pattern. These villages are mostly located in the Sichuan area. In addition to lacking resources for tourism development, local policies also lead to slow village development. The main characteristics of these villages are concentrated in the changes in the spatial structure within the homestead, which is the inclusiveness of development concepts influenced by traditional concepts.

6.2. Exogenous Evolution

The main characteristic of villages undergoing exogenous evolution is the rapid embedding of tourism capital and obvious spatial compounding, but the core of belief is preserved. These villages are mostly located in the Yunnan area. In addition to having rich resources for tourism development, local policies also lead to the rapid development of villages. It can be seen that policies and land systems are “levers” for differentiation, and the level of governance and investment and financing models determine the starting speed. The Yunnan side is directly overseen by provincial and municipal levels, allocating funds, brands, and “precursors” such as airports; the Sichuan side has long remained at the county level, lacking inter-city and inter-provincial coordination. The land preparation mechanism also affects the implementation of large-scale cultural tourism projects. Yunnan achieves a contiguous land supply through “collective construction land acquisition and storage + secondary market,” providing opportunities for large capital to intervene; Sichuan’s land ownership is fragmented, and transfer procedures are complex, leading to high capital entry costs and long cycles.

7. Conclusions

This study, using nine Lugu Lake villages as samples, for the first time coupled time-series statistics of functional areas with “embodied” spatial concept indicators, demonstrating that the spatial morphological evolution from the first to the third generation is not simply economically driven but an organic continuation of endogenously evolving concepts; it then proposed a quantitative verification path where “conceptual order precedes spatial form,” elucidating the three-way interactive mechanism of traditional concepts, market logic, and policy intervention. The research results can be summarized at three levels, micro, meso, and macro:

(1) Micro-level: Family structure and functional restructuring, dominated by spatial concepts.

The spatial evolution of Mosuo settlements highly reflects the structural logic of “concept determines space.” From the first-generation closed cluster settlements (e.g., Bu’erjiao) to the third-generation composite tourism settlements (e.g., Daluoshui, Lige), the renewal trajectory of their spatial functions is not simply market-driven, but unfolds under the dominance of the Mosuo people’s deeply rooted matrilineal system and belief system in daily life—the spatial order of the flower house, the ancestral house, and the women’s house originates from this.

Although the strong embedding of commercial and lodging functions has appeared in some third-generation settlements, their spatial distribution and conversion rhythm still reveal the self-consistent regulation of cultural concepts. For example, even in highly developed tourism settlements, the ancestral house space is often not compressed or ceded, reflecting the strong dominance of intangible culture in spatial evolution. It particularly needs to be emphasized that the nine villages around Lugu Lake, due to their strong geographical isolation and continuous cultural inheritance, have presented a clearer natural evolution process of Mosuo traditional spatial concepts in the absence of direct external intervention. This “endogenous evolution model” differs from regions with strong external policy intervention, providing a unique perspective for ethnic settlement space research.

(2) Meso-level: Composite evolution of residential patterns and settlement morphology.

In terms of the overall village layout, the spatial morphology shows an evolutionary trend from cluster settlements to linear and axial-belt settlements. Villages on the Yunnan side, under the dual guidance of governance power and tourism policies, gradually expand along the lake shore and roads, with focal node spaces continuously strengthening; while villages on the Sichuan side, due to a lack of systematic planning and infrastructure support, have looser settlement spatial organization and insufficient structural elasticity.

Changes in the functional area show that the volume of mixed commercial–residential use increases year by year, while residential and religious spaces are compressed, but have not completely exited the core area, presenting a spatial strategy of “cultural core retention + functional boundary expansion.” Overall, Mosuo settlements have not been completely shaped by the market, but have self-organized their spatial order through “compatibility-adjustment-integration” guided by cultural concepts.

(3) Macro-level: Differentiation of policy mechanisms and spatial governance systems.

This study further points out that differences in institutional resources lead to significant differentiation in spatial evolutionary paths. Governance system: The Yunnan side is jointly promoted by provincial and municipal levels, forming a closed loop effect of resource allocation, planning guidance, and capital docking; Sichuan, on the other hand, has long been limited to county-level governance, with insufficient driving force. Land system: Yunnan, through collective land preparation and secondary market circulation, achieves a contiguous land supply, attracting capital to intervene; Sichuan’s land ownership is fragmented, and procedures are complex, leading to high capital entry barriers. Market coupling: Yunnan’s tourism policies are mature, forming an integrated “Lijiang-Lugu Lake” system, promoting tourist stay time and conversion rate; while Sichuan’s marketing system is weak, and spatial value release is insufficient. At the level of spatial justice and sense of place construction, the Yunnan side has better achieved the integration of traditional spatial concepts and market mechanisms, achieving a virtuous interaction among “culture-institutions-capital”, while the Sichuan side faces the dual challenges of governance fragmentation and cultural landscape commercialization, and spatial justice still requires institutional intervention to rebuild.

In summary, the spatial evolution of Mosuo settlements is a composite spatial generation process “dominated by cultural concepts, regulated by institutional resources, and supplemented by market mechanisms.” Based on empirical research on nine villages around Lugu Lake, this paper constructs a spatial evolution explanatory framework under the triple dimensions of “spatial concepts-family structure-institutional mechanisms,” clarifying the cultural resilience and spatial logic of ethnic settlements in responding to the pressures of modernity. Future research can combine the perspective of new materialism in geography to further explore the structure of ethnic settlements under the theoretical framework of spatial justice, the interactive mechanisms of concepts and forms in cross-cultural comparison, dynamic quantitative models driven by GIS remote sensing, and collaborative governance paths for tourism planning, land policies, and cultural protection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X. and J.Y.; methodology, Y.X.; validation, Y.X. and J.Y.; formal analysis, Y.X.; investigation, J.C.; resources, Z.W.; data curation, Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X.; writing—review and editing, Z.W.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, J.Y.; project administration, J.Y.; funding acquisition, J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [51968028] and [52268005].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings of this study are included in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to advisor JianYang, for his meticulous guidance and support throughout this research. The authors also acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, which has been instrumental in the completion of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, Y.S. Rural Revitalization Geography for the New Era. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 461–466. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.S. China’s New Era Urban-Rural Integration and Rural Revitalization. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.C.; Luo, X.L. Group Characteristics and Planning Implications of Scenic Villages under Multiple Factors: A Case Study of West Lake Scenic Area. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 27, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.C.; Zhao, M.F.; Ge, Q.S. Micro-Scale Analysis of Rural Settlement Land Use Patterns in Tourism Destinations: A Case Study of Gougezhuang Village in Yesanpo Tourism Area, Hebei. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2011, 66, 1707–1717. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, J.P.; Hu, Y.T. Actioner Network Perspective on Rural Industry Integration Process and Mechanism: A Case Study of Shicha Village in Haikou. Geogr. Res. 2023, 42, 2759–2778. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.K. Rural Revitalization: Rural Transformation, Structural Transformation and Government Functions. Issues Agric. Econ. 2020, 1, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Dai, L.L. Evolution and Influencing Factors of Rural Settlement Spatial Pattern in Wuhan Metropolitan Area. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 29, 383–390+398. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H. Land Use Transitions and Rural Restructuring in China; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua, A. Conceptualizing new materialism in geographical studies of the rural realm. Land 2023, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.L.; Yang, X.J.; Yang, T. Adaptation Patterns of Rural Households to Tourism Development and Mechanisms: A Case Study of Jinsixia Scenic Area in Qinling Mountains. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2013, 68, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Woods, M. Rural Restructuring Under Globalization in Eastern Coastal China: What Can Be Learned from Wales? J. Rural Community Dev. 2011, 6, 70–86. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J. A Study on Changes and Development of Mosuo Culture in Lugu Lake Area. Master’s Thesis, Yunnan University, Kunming, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.Y. Yunnan Ethnic Minority Dwellings; Tianjin University Press: Tianjin, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.Y. On the Concept of “Persistent Space” and Its Formation: A Kantian Critique and Reconstruction. J. Sun Yat-Sen Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2024, 64, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.M. Multiple Implications of Heidegger’s Concept of Space. Jianghan Trib. 2018, 8, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.Q. Descartes’ Space Concept and Its Modern Significance. J. Sichuan Norm. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2014, 41, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y. Expression of Traditional Concepts in Mosuo Settlement Space of Lugu Lake. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tarayia, G.N. The Legal Perspectives of the Maasai Culture, Customs, and Traditions. Ariz. J. Int. Comp. Law 2004, 21, 183–222. [Google Scholar]

- Wikle, T. Living and Spiritual Worlds of Mali’s Dogon People. Focus Geogr. 2016, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuper, A. The ‘House’ and Zulu Political Structure in the Nineteenth Century. J. Afr. Hist. 1993, 34, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, T.S. Kinship, Household, and Community Structure among the Kayapó. In Dialectical Societies: The Gê and Bororo of Central Brazil; Maybury-Lewis, D., Ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979; pp. 179–217. [Google Scholar]

- Knox-Seith, B. Being and Becoming Quechua: Social Relationships and Dynamics of Control in a Peruvian Andean Village. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wibawa, K.C.S.; Susanto, S.N. Establishing a Special Autonomy Model in Bali as a Means of Preserving Hindu Balinese Culture and Space. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 1609–1614. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, A.E.; O’Connor, J.T. Settlement Pattern Studies in Polynesia. In The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Oceania; Cochrane, E.E., Hunt, T.L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; p. 450. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, H.; Li, J.H. Mosuo Dwellings under the Influence of Mosuo Cultural Customs. Huazhong Archit. 2007, 1, 79+82. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.Y.; Bai, Y.S. Vernacular Architecture and Residential Culture of Mosuo People in Northwestern Yunnan Plateau. In Proceedings of the 15th Chinese National Conference on Vernacular Architecture; China National Architecture Society: Kunming, China, 2007; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.L.; Zhao, C.L.; Gao, Z.X. Multicultural Interaction and Convergence: Spatial Analysis of Mosuo Grandmother House—Case Study of Gesagu Village in Sichuan. Archit. J. 2020, S1, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. Formation Methods of Architectural Theory. Ph.D. Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.Y. Research on Vernacular Architecture in Mosuo Settlement Areas of Northwestern Yunnan Plateau. Ph.D. Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lamu, G.T.S. (Ed.) Mosuo Daba Culture; Yunnan People’s Publishing House: Kunming, China, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Harries, K. The Ethical Function of Architecture; Huaxia Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.Y.; Bai, Y.S.; Che, Z.Y. Spiritually Significant Living Space: Architectural Form and Culture of Mosuo Dwellings. Huazhong Archit. 2009, 27, 252–256. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. The Wall of “Shame”. Master’s Thesis, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.W. Genealogy of Log Construction Architecture in Northwestern Yunnan Based on Craft Surveys. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.Y. Spatial Planning of Mosuo Villages Along Lugu Lake (Yunnan Section) and Planning of Xiaoluoshui Village. Master’s Thesis, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.Y.; Li, D.F. Formation and Development of Hani Settlements: Case Study of Dayazhe Village in Yuanyang. Chin. Overseas Archit. 2021, 2, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).