Abstract

This research is focused on housing stock rehabilitation and construction in Urban Rehabilitation Areas located in diverse contexts in the Portuguese territory. The main objective of this research is to show how the local actors have managed the ARUs’ opportunities to restore and develop the housing in these areas in the Portuguese territory. An analytical national legal framework is made to show that the diffuse criteria at national and regional levels are reflected in the limited effectiveness of the ARUs’ flexible criteria in local implementation. A national legislative and regulatory framework in Portugal, focusing on urban rehabilitation and housing promotion themes, is discussed to emphasize the potential role of Urban Rehabilitation Area (ARU) particularities and housing provision and preservation in diverse contexts in Portugal. A comparative analysis is conducted of five ARUs—Belmonte, Soure, Penacova, Vila Real, and Devesas—located in Portugal, in the North and Center regions, to highlight the particularities/diversity of urban contexts, including towns, small to medium-sized cities, and historic centres. The analysis assesses the effectiveness of ARU urban rehabilitation strategy implementation over time. The analysis of five ARUs will discuss the following: (i) ARU physical characteristics; (ii) ARU population profile; (iii) ARU urban rehabilitation strategies progress (initial, intermediate, and final); and (iv) ARU alignment with PDM priorities in urban rehabilitation. The findings underscore the pivotal role that ARUs and their actors can have in housing rehabilitation provision and preservation on different scales and contexts within the territory. The outcomes show different strategies that each ARU has used to prioritize building rehabilitation.

1. Introduction

This study aims to debate the need to fix housing preservation and development inside the Urban Rehabilitation Areas (ARU). In this research, housing preservation refers to the set of public or private initiatives, planned or executed within ARUs, to increase the supply of adequate, affordable, and sustainable housing through construction, rehabilitation, or adaptive reuse of the existing building stock. This discussion is particularly relevant due to the multiple crises in housing in Portugal, following the end of the authoritarian regime and continuing to the present day (1974–1985: Post-Revolution and Urban Growth (Reforms often late, fragmented, or ineffective); 1986–1999: EU Integration and Urban Renewal (Increasing in urban areas); 2000–2008: Financialization and Real Estate Bubble Begins (Old, inefficient buildings with high energy bills); 2008–2014: Crisis and Austerity (Airbnb and short-lets displace locals); 2015–2020: Tourism Boom and Housing Market Explosion (Foreign investors drive up prices); 2020–2021: COVID-19 Pause and Inequality (Low supply of public and affordable housing); 2022–2025: Multi-crisis Intensifies (Incomes lag far behind rising housing costs).

Urban rehabilitation strategies and housing provision and preservation in Portugal are shaped by a planning regime typical of Mediterranean countries, which is marked by limited state intervention and a heavy reliance on familial support networks to address social and housing inequalities [1,2]. Although Portugal adopts a land-use zoning model like other European countries (e.g., Italy and Spain), urban planning decisions have historically favoured private interests, particularly those of developers and landowners, often at the expense of environmental sustainability and social equity [3]. In Lisbon, for instance, demographic decline combined with speculative investment has resulted in a housing market imbalance, where an oversupply of high-end units coexists with persistent affordability challenges [4]. Despite EU-funded regeneration programs such as URBAN I and II and the PRU, many rehabilitated properties remain vacant due to ongoing financial speculation, ultimately failing to meet their intended social objectives [2]. Present challenges include reactivating vacant and short-term rental units for long-term residential use and realigning housing policies with demographic realities rather than market-driven construction cycles [5]. Delivering decent and affordable housing across diverse contexts requires not only the physical rehabilitation of the built environment but also the implementation of regulatory frameworks that reaffirm housing as a fundamental space for living, particularly for vulnerable populations [6]. This imperative is further emphasized by the regional disparities and the varied dynamics of housing provision and preservation observed across Portuguese municipalities [7]. However, a theoretical European framework is needed to understand the broader debate on urban rehabilitation strategies, and housing provision and preservation in urban areas. Particular attention is given to the Italian and United Kingdom contexts, due to their significant contributions to the housing provision and preservation field.

The European debate on housing provision and preservation demonstrates a complex interplay of policy approaches and socio-economic realities, with studies in various countries offering distinct strategies, yet lacking in convergence or adaptability. In France and Spain, living labs have emerged as a participatory model involving diverse stakeholders in rehabilitation practices within historic urban areas. These living co-creative labs prioritize criteria such as operational energy, heritage preservation, quality of life, socio-economic development, and material logistics, grounded in local contexts [8]. In Italy, a highly structured preservation framework spans buildings to landscapes, with emphasis on seismic risk zones like L’Aquila, where detailed maps assess heritage building usability and damage [9]. Italy has further broadened its preservation discourse through the concept of “minor historic centres” in regions like Tuscany, focusing on vulnerabilities at structural, socio-economic, and institutional levels [10]. Italian metropolitan coastal cities, such as Genoa and Naples, have been evaluated through homogeneous cluster methodologies that address environmental and urban quality challenges [11], complemented by multi-criteria assessments of peri-urban sprawl aimed at mitigating expansion through strategic urban boundary interventions [12].

However, Italy’s strong conservationist tradition, influenced by historic charters like those of Gubbio and Bologna, has resulted in regulatory rigidity, which, along with economic stagnation, has increased vacant housing and undermined the social and economic vitality of historic centres [13]. The growing demand for second homes and the pressure of mass tourism—especially in Naples—have further strained the housing stock, a trend accelerated by the post-COVID-19 pandemic shift in mobility and short-term rentals [14]. Inland and rural areas face parallel challenges, where depopulation calls for integrated regeneration policies encompassing sustainability, social inclusion, and improved infrastructure [15]. Some Italian studies propose innovative compensation-based models to remove incompatible structures and encourage redevelopment aligned with heritage values, in order to curb urban decay and prevent unnecessary land consumption [16].

The impact of UNESCO World Heritage designation has also been scrutinized, with findings indicating that such recognition inflates property values, intensifying competition and displacing residents, particularly in urbanized areas with limited housing supply [17]. Further analyses, such as that in Turin, use regression techniques to link architectural features, like daylight, energy classification, and amenities, to post-pandemic housing market trends [18]. National-level diagnostics have attempted to evaluate Italian cities’ alignment with ONU sustainability goals (SDG 9 and SDG 11), yet persistent governance issues hinder the realization of comprehensive urban sustainability [19].

In the United Kingdom, the pandemic catalysed new pressures on rural housing markets, as seen in Wales’s Brecon Beacons National Park, where urban flight contributed to housing price surges under conditions of restricted development [20]. The UK’s emphasis on social housing as a solution for vulnerable populations is paired with environmental performance metrics that assess housing conditions in terms of affordability, thermal comfort, and energy use [21]. Nonetheless, the UK faces an acute housing crisis, prompting policy moves toward deregulation, notably through the expansion of permitted development rights (PDR) for office-to-residential conversions. These conversions often circumvent quality standards, raising concerns about habitability and exclusion [22]. Comparisons with Italy highlight structural differences in planning paradigms, with England’s discretionary model contrasting with Italy’s zoning-based approach. In Denmark, a more data-centric model has been implemented, relying on national building registers and public databases to guide renovation policies and sustainability assessments. These systems incorporate indicators on indoor climate, energy savings, material reuse, and affordability, positioning data transparency and circularity at the forefront of housing strategy [23].

Therefore, while the body of research across France, Spain, Italy, the UK, and Denmark offers rich and varied perspectives on housing provision and preservation, the lack of flexibility in diverse evaluative frameworks is evident. Each national context operates within distinct planning and regulatory paradigms, with localized challenges and methodologies. Despite valuable insights into participation, heritage risk, environmental stressors, and digital innovation, the studies do not provide adaptable criteria or integrative strategies that can be generalized or replicated across different urban contexts.

Moreover, as Portugal is an EU member state, housing policies are increasingly focused on expanding the supply of public and affordable housing, addressing the energy crisis, regulating the real estate market to control speculation, and encouraging environmental sustainability, especially in urban areas and historic city centres [24]. However, there is a lack of flexible analysis in diverse Portuguese regional and local contexts, with which to understand the implementation of the regulatory framework at different levels (national and regional) [2].

The literature review debate shows diverse methodologies that assess diverse contexts with the same criteria, yet they lack adaptation to the specificities of each context to obtain refined outcomes. A critique is also offered regarding national and local legal frameworks, which are addressed broadly without delving into detailed, case-specific considerations. However, this research seeks to highlight diverse contexts across a range of urban areas, and in small urban/historic centres located in central and inland regions of Portugal, many of which hold heritage value and are part of the Recovery program for Portugal’s historic villages [25]. This research aims to understand how spatial planning instruments are adapted at the municipal level and within these small historic centres. Accordingly, the study examines the broader legal and institutional framework, including supranational legislation, particularly that of UNESCO [26], ICOMOS [27], and the European Council [28], along with related provisions, Portuguese spatial planning legislation, and its application at the local and municipal levels. The research focuses on areas facing significant challenges, such as deteriorated building stock, limited financial capacity to construct affordable housing, and the need to improve the habitability of existing homes.

Thus, this study focuses on five ARU case studies selected in the Portuguese municipalities of Belmonte, Soure, Penacova, Vila Real, and Devesas, located in the Northern and Central regions. A comparative analysis is made of ARU rehabilitation strategies since their creation, especially related to housing conservation and development. The temporal analysis framework is recovered from public documents. The study is focused on (i) the physical and social characteristics of the ARUs; (ii) rehabilitation strategies focused on local housing management, and the relation with each Director Master Plan (PDM) strategy.

The research is structured into the following sections: legal framework and concepts, materials and methods, results, discussion, and conclusions. Section 2 provides a brief and chronological overview of the national legislative and regulatory instruments relevant to urban rehabilitation and their articulation at regional and municipal levels. It frames the ARUs’ strategic plans within the legal context of municipal management tools. Key concepts related to the ARU and housing discussion are explained in the scope of this study. Section 3, Materials and Methods, outlines the methodological approach adopted for the comparative analysis of five ARUs, considering the identification of their respective physical delimitations in territory over time, and their rehabilitation strategies. Section 4 presents the results of the comparative analysis of the five ARUs. Section 5, Discussion, presents the outcomes from the comparative analysis of the case studies (Section 4), considering the legal framework shown and discussed in Section 2. This section aims to validate the research hypothesis and provide substantive answers to the questions raised. The final Section 6 (Conclusions) summarizes the findings of the case studies, emphasizing the complexities surrounding housing in local management through ARU strategies. It also highlights the need for further research to reinforce the importance of monitoring the ARUs to promote territorial cohesion and enhance housing provision and preservation to dynamize these small historic centres.

2. Legal Framework

This section outlines the key supranational, national, and municipal regulations and frameworks related to urban rehabilitation and housing stock. It also presents the main urban rehabilitation strategies and instruments, emphasizing their role in supporting the development of “Urban Rehabilitation Areas” (ARUs). Additionally, several key concepts are defined to provide greater precision in the case studies’ analysis and interpretation.

2.1. National and Legal Framework

The housing crisis in Portugal was exacerbated during and after the dictatorship (1933–1974) due to rent freezes and a lack of property maintenance. The decapitalization and degradation of the building stock are justified by the generalized freezing of rents in Portugal until 1974, which was partially overcome from 1990 [29] and cancelled in 2006 [30]. These constraints led property owners to disregard their legal obligation to perform conservation and maintenance work every eight years [31]. Local authorities established teams of specialists within support offices to prioritize interventions in areas with unsafe and inadequate housing conditions. Within this context, Urban Rehabilitation Areas (ARUs) gained prominence at the municipal level in Portugal from the 2000s onwards, particularly following the introduction of the Legal Regime for Urban Rehabilitation (RJRU—Decree-Law No. 302/2012) [32]. Each ARU comprises rehabilitation strategies according to the PDM’s land use objectives. However, there is still limited debate on ARU monitoring during this time, and their efficient role in local housing management [33].

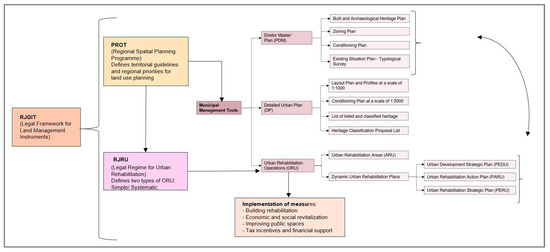

On the one hand, Decree-Law no. 117/2024, of 30 December [34], aims to guide land-use planning to promote housing at the national level. The amendments were approved as part of the Building Portugal Program, which aims to boost the construction of public and affordable housing in response to the decline in housing development over recent decades. Additionally, Decree-Law No. 117/2024 amends the RJIGT legal regime (Decree-Law No. 80/2015) [35] on an exceptional basis to facilitate the development of new housing within urban areas. These changes are in line with the General Basis Law for Public Land Policy, approved by Law no. 31/2014, of 30 May [36]. However, Law No. 31/2014 [36] requires uniform criteria coordinated with the Regional Land-Use Plan (PROT). This regional management land tool (PROT) is tailored to each region’s characteristics and priorities, lacking national legal flexible criteria between each PROT and the municipal level. Thus, legal changes in Decree-Law No. 117/2024 [34] should promote flexible assessment, binding criteria for land-use reclassification, at different levels. The urban rehabilitation strategies and housing provision and preservation need to be aligned with the objectives of RJRU, and the land-use regulations of the RJIGT, both at the national level, and the Director Master Plan (PDM) at the local level. Therefore, flexible analyses are needed to promote urban rehabilitation and territorial cohesion (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Territorial management instruments’ organization in Portugal (1st author’s scheme).

On the other hand, the ongoing urban planning regulatory changes come under the Simplex [37] platform, an initiative aiming to streamline municipal management in Portugal by simplifying regulations, digitizing urban planning processes, enhancing transparency, and automating tasks to improve efficiency and modernization in housing permits. Simplex has goals in the following areas: (i) introducing ARU procedures in digital platforms; (ii) integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) to dynamize urban planning in open source; and (iii) automating municipal tools and their interaction with territorial tools (regional and national). Thus, the ARU procedures will benefit from the Simplex procedure when integrated into the municipal system.

In the ARU analysis, it is essential to highlight the Local Ambulatory Support Service (SAAL), created under the leadership of Nuno Portas [38] to address the housing needs of vulnerable populations, emphasizing fieldwork and active residents’ participation in the urban regeneration projects. Unlike conventional approaches, public participation in architectural design is ensured throughout the process, tailored to the specific needs of each community rather than being developed solely in office settings. This participatory approach remains a key reference for municipal authorities and technical teams today. Consequently, it is a priority to understand the benefits of Local Housing Strategies (ELHs) [39] in advancing housing provision at the local level and incorporating them into the Recovery and Resilience Plan (PRR) funds for urban regeneration. The ELH framework seeks to mitigate the social and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic while aligning with the European Commission’s housing policy guidelines. Today, Municipal Urban Rehabilitation Societies (SRU) can support the implementation of ELH, although in a slow co-creation process with communities. Their efforts should prioritize affordable and decent housing, granting financial and tax incentives, and other means of providing houses to citizens [36,39].

Moreover, in the context of this analysis, it is essential to summarize the legislation referred to in this section at the supranational and national levels (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Contributions of national laws/regulations in improving ORU procedures (1st author’s table).

2.2. Municipal Plans and Local Management Strategies

National regulations and tools [34,35,36] complement municipal management instruments, which are shaped by various plans and operations within three main frameworks: the Director Master Plan (PDM), the Detailed Urban Plan (PP), and Operations of Urban Rehabilitation (ORUs). Thus, ORUs are compounded through Urban Rehabilitation Dynamics Plans: (i) PEDU—Strategic Urban Development Plans—with general guidelines and a macro strategic vision; (ii) PARU—Action Plan for Urban Rehabilitation—for specific areas with defined interventions; and (iii) PERU—Urban Rehabilitation Strategic Plan—executive projects with drawings and technical detailing for construction.

Nowadays, the PDMs have been revised across various municipalities, updating land-use plans, zoning regulations, heritage preservation, and urban planning strategies aligned with regional and national tools/rules (see Figure 1). The Detailed Plans (PPs), which are developed with urban requalification goals, focus on improving public spaces. While ORUs are being updated, progress has been slow, like the revisions made to the PDMs [40], supporting the ARUs’ urban rehabilitation strategies. Thus, the hierarchical municipal management tools ensure that urban interventions can be well-planned, coordinated, and feasible, from strategic vision to practical execution. The ARUs’ goals are linked with PDM objectives, and the municipal technicians play a key role in ARU implementation.

2.3. ARU Goals and Concepts

In Portugal, ARUs are designated zones inside inner cities, historical centres, rural areas, and villages, targeting urban regeneration and revitalization. Since 2009, Urban Rehabilitation legislation [32] has been strengthened to promote integrated interventions within the existing urban fabric. The delimitation of ARUs addresses the need to protect urban zones requiring special intervention and/or classification due to factors, such as the presence of buildings with heritage value that must be preserved [26,27,28]; degraded conditions and poor habitability of buildings; insufficient infrastructure to support housing and the local population; and the need for public space renewal and roadway improvements. These designated ARUs, aim to (i) support the local management; (ii) enhance urban consolidation through regeneration efforts, (iii) strengthen urban life by upgrading green spaces, public areas, and collective-use facilities, reinforcing the ecological structure; (iv) improve urban quality through functional integration and economic diversity; (v) offer fiscal incentives, including reductions in Value Added Tax (VAT) and Municipal Property Tax (IMI) to property owners who reside permanently in their buildings. Therefore, the ARUs include the following: (i) the Strategic Urban Development Plan (PEDU, whose principal aim is to create the conditions necessary to ensure the strategic execution defined for the ARUs’ territory, considering the investment priorities estimated/defined by the ARUs; (ii) the Urban Rehabilitation Action Plan (PARU) that integrates a set of public projects/actions promoted by the municipalities’ authorities, as well as a range of private interventions that will be embraced by the private sector, gathering the commitment of many property owners within the diverse ARUs. The PARU also includes objectives such as enhancing heritage and cultural identity, boosting tourism attractiveness, and fostering economic and socio-cultural dynamics; and (iii) the Strategic Urban Rehabilitation Plan (PERU) that develops urban regeneration strategies in central and peripheral consolidated urban areas. It also oversees the programs and allocation of financial and human resources required for implementing ORUs.

Additionally, to discuss the implementation of the ARUs, key concepts’ definition is essential to this research: (i) “Quality of life” refers to the balance of various factors, including physical, emotional, and social well-being, combined with health, work, safety, and housing, enabling individuals to live fulfilling lives. It can be assessed subjectively through personal perceptions of happiness and satisfaction or objectively through life expectancy, healthcare access, and housing affordability indicators; (ii) “Affordable housing” strikes a fair balance between quality and cost, offering a safe and suitable living space that does not exceed a household’s financial capacity. (iii) “Decent housing” refers to homes that uphold safety, comfort, and dignity, meeting adequate living standards. It should have proper infrastructure, structural integrity, sufficient space without overcrowding, and a cost aligned with its quality. (iv) “Heritage attributes” are characteristics of buildings or areas with historical, cultural, or architectural significance. (v) “Collective-use facilities” are public or shared infrastructure serving the community, such as parks, cultural centres, and transportation hubs. (vi) “Actors” are the stakeholders involved in shaping the urban environment; (vii) “Housing provision and preservation” refers to the maintenance, restoration, and protection of existing housing to ensure its continued habitability, cultural value, and affordability to the residents/citizens.

3. Materials and Methods

This section presents the ARU case studies, explaining the methodology used to examine them: (i) strategic plans used in the case studies and criteria; and (ii) how local authorities have leveraged urban rehabilitation, considering housing provision and preservation.

3.1. Materials

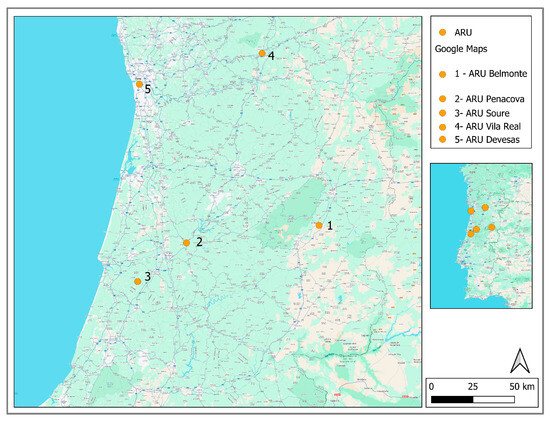

Five ARUs are selected considering their different characteristics (localization, area size, population, residential buildings): Belmonte (village in Castelo Branco district), Soure, and Penacova (villages in the Coimbra district); the historic centre of Vila Real city and district; and Devesas, Vila Nova de Gaia, Porto district (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Identification of the ARUs (1st author’s scheme).

The research will use the following materials to analyse the case studies: (i) Municipal ARU urban rehabilitation strategies, and ORU plans (e.g., PEDU, PARU, and PERU); (ii) Director Master Plans (PDMs) from each municipality in which the ARUs belong (see Table 2); (iii) local documentation, regarding heritage protection and preservation (it is verified that the case studies’ ARUs are classified as UNESCO sites and are included in the Recovery program for Portugal’s historic villages); (iv) measures to improve the quality of life of citizens (e.g., ELH).

Table 2.

ARUs’ Case studies and Urban Rehabilitation Plans (1st author’s table).

Moreover, the ARUs’ illustrative materials will consider: (i) the geometrical limitations of each ARU; (ii) building stock analyses; (iii) housing conditions; (iv) overall indicators from the state of conservation of buildings. The illustrative maps are oriented to the north for better clarity and a more effective comparative analysis of the territory. The analysis draws on publicly available online documents.

3.2. Methods

The outcomes of the academic literature review show that the diverse methodologies (e.g., those in Italy and the United Kingdom) apply homogeneous criteria to diverse contexts. Thus, the methodological process presented in this research aims to identify each ARU’s geographical context and the urban rehabilitation strategies adopted. Therefore, the methodological characterization of each ARU is compound by the following general indicators: (1) identify the physical characteristics of the ARUs: size of the area; total number of buildings; occupancy of residential buildings (occupied and vacant); (2) identify the social characteristics of the ARUs [population profile: total population; age distribution (adults and the elderly); active population (considering the number of economically active and inactive individuals)]. These criteria will also allow us to understand the dimension of each urban area and constraints related to the community’s effectiveness in the process, since the urban strategies depend mostly on private investment. In addition, the Portuguese legal framework shows that ARU’s urban rehabilitation strategies are linked to municipal plans and their amendments (e.g., PDM), which are also guided by the overarching directives of national spatial planning instruments and their amendments (e.g., RJGIT and RJRU). Thus, the ARUs’ methodological characterization will include the following: (3) urban rehabilitation strategies for the existing buildings, considering preservation actions and housing provision, with the ARUs’ strategies progressively adjusted over time (initial, intermediate, and final). Furthermore, the methodology characterization aims to identify: (4) the ARUs’ alignment with their PDM priorities in urban rehabilitation, for example: (i) classification of the ARUs as UNESCO site or classified buildings; (ii) inclusion in the Recovery program for Portugal’s historic villages; (iii) rehabilitation strategies for buildings and housing; (iv) introduction of digitalization procedures.

Furthermore, the five ARUs will be analysed in three steps, considering the four items presented above: (1) ARUs’ physical characteristics; (2) ARUs’ population profile; (3) progress in ARUs’ urban rehabilitation strategies (initial, intermediate, and final); (4) ARUs’ alignment with their PDM priorities in urban rehabilitation. Moreover, the literature review, the legal framework analysis, and the materials and methods used for ARU characterization aim to deal with the following central hypothesis: Urban Rehabilitation Areas can promote opportunities for local management in housing provision and preservation, followed by four key research questions:

- Q1: What strategies do local actors have for promoting housing within the ARUs?

- Q2: Which strategies are implemented in ARUs to promote social and affordable housing?

- Q3: How does the digitalization of municipal procedures and a shared database promote flexible criteria?

- Q4: How can the municipal legal approach be more flexible in ARU implementation, following the national regulations?

The first step consists of the analysis of each ARU; the second step includes a comparative framework (Table 3); the third step shows the particularities of each ARU, considering the geographical context (physical and social) and the local management strategies for housing provision and preservation in a SWOT analysis (Table 4).

Table 3.

ARU Characterization and Urban Rehabilitation Strategies aligned with PDM strategies (1st author’s table).

Table 4.

SWOT Analysis of the ARUs: underlines the particularities of each ARU’s urban rehabilitation strategies (1st author’s table).

Moreover, the discussion section aims to validate the hypotheses and address the research questions outlined.

4. Results

4.1. ARU from Belmonte

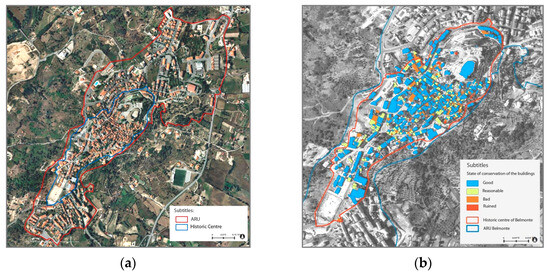

The ARU of Belmonte village belongs to the Castelo Branco district and is located in the central region of Portugal. The ARU’s first geometrical delimitation was in 2011 and related to the historic city area (Figure 3a). In the ARU’s physical analysis characteristics, it is verified that the area has 80 hectares. It is constituted by 1167 buildings, of which 893 are occupied and 274 are vacant and/or in ruin. In the ARU social analysis, it is verified that the ARU has 4121 inhabitants, of whom 1564 are adults and 532 are elders. The active population is 916 residents, and 186 are inactive.

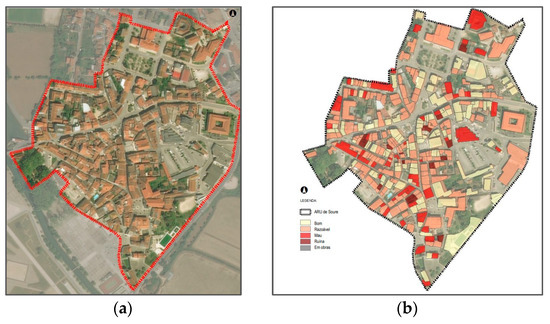

Figure 3.

Delimitation of the ARU and Historic Centre of Belmonte (pp. 35 and 134 [41]) as (a) Delimitation on the aerial Orto map; (b) ARU’s Buildings degradation levels, where buildings are good (in blue), reasonable (in yellow), bad (in orange), and ruined (in red).

During the analysis of the ARU strategies and the PERU and PARU documents from the ORU, differences can be identified in the urban rehabilitation approaches across the various stages of development (initial, intermediate, and final). The initial strategy (2011) aims to (i) ensure the rehabilitation of dilapidated or functionally inadequate buildings; (ii) rehabilitate degraded or deteriorating urban areas; (iii) improve the habitability and functionality of the urban stock; (iv) ensure the protection and promotion of cultural heritage; develop new solutions to give residents access to decent housing, although, since 2011, no local strategies have been developed to develop affordable and decent housing [41].

The intermediate strategy was formed in 2021, when, in addition to the 2011 objectives, the strategy of creating local tourist accommodation in the historic centre was added. Analysing the documentation associated with Belmonte’s 2021 ARU, the municipal technicians were committed to re-evaluating the existing buildings and classifying their state of conservation (Figure 3b).

In addition, the ARU’s rehabilitation strategy for housing provision, primarily targeted at property owners undertaking rehabilitation work on their buildings, offers incentives such as a three-year IMI exemption for urban properties used as permanent residences or rental units. In 2021, the ARU strategy aimed to promote private investment aimed at local tourist accommodation in the historic centre. In addition, the PARU Plan lacks a robust management strategy for housing preservation because the assessment of the safety and habitability conditions in the interior of the buildings is missing. Without these data-driven analyses, it cannot accurately prioritize interventions or allocate resources effectively. This gap undermines the ARU’s effectiveness in prioritizing rehabilitation efforts, limiting its overall impact on improving housing quality. The ARU urban rehabilitation strategies are currently in progress.

The PDM of Belmonte [42] focuses its strategies on sustainable development through circular economy strategies. A Detailed Safeguard Plan is proposed to manage the heritage-rich area of Belmonte’s historic centre (setting rules to protect and integrate traditional buildings, especially in tourism-related projects), while allowing creativity in new constructions that respect the area’s character. It also aligns with broader standards of the Recovery program for Portugal’s historic villages.

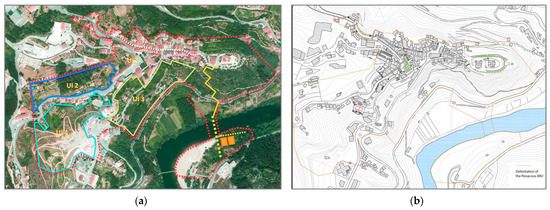

4.2. ARU from Penacova

Pencova village belongs to the Coimbra district and is in the central region of Portugal. The ARU’s first geometrical delimitation was in 2015, including two areas near the Mondego River and within the Intervention Unit (UI) limits (Figure 4a). The second delimitation was in 2024, adding further area to the initial delimitation (Figure 4a). The ARU’s physical analysis characteristics verify that the area has 21.20 hectares. It is constituted by 8376 buildings, of which 5284 are occupied and 3092 are vacant and/or in ruin. Social analysis shows that the ARU has 2824 inhabitants, of whom 1688 are adults and active residents, and 859 are elders and inactive residents.

Figure 4.

Delimitation of the ARU from the urban area of the Penacova settlement (pp. 18 and 30 [42]): (a) The UIs from the ORU in ARU; (b) ARU delimitation.

During the analysis of the ARU strategies and the PARU documents from the ORU, differences can be identified in the urban rehabilitation approaches across the various stages of development (initial, intermediate, and final). The initial strategy (2015) develops the program PintALinda, which aims to restore the façades of buildings built at least 30 years ago or included in settlements with recognized heritage value. The intermediate strategies (2024) are focused on monitoring work, aiming to preserve the rural villages along the Mondego River sides that are intended to be preserved. In addition, there was a Tax incentives update (e.g., VAT reduction to 6% on the value of architecture, engineering, and landscape design projects). The local authorities have implemented an 80% IMT reduction for properties intended for permanent housing in the UI1 area and a 50% reduction for those in UI2 and UI3 [43]. As of today, the Penacova ARU’s strategies have not been concluded. Furthermore, up to 2024, a total of 18 beneficiaries have received support through the ELH program, and 10 affordable housing units.

Therefore, the Penacova PDM [44] prioritizes sustainable development through circular economic strategies. Housing need strategies are being addressed through the combined support of the ELH Program and the Public Affordable Housing Program. Monitoring cultural heritage protection plans aims to strengthen the preservation of the rural villages along the Mondego River.

4.3. ARU from Soure

The ARU of Soure village belongs to the Coimbra district and is located in the central region of Portugal. The ARU’s first geometrical delimitation was in 2016, increasing the area by 218 (second delimitation, Figure 5a). The physical analysis shows that the ARU has 13.65 hectares; it is constituted by 329 buildings, of which 244 are occupied and 67 are vacant and/or in ruin. Social analysis shows that the ARU has 7917 inhabitants, of whom 101 are adults and 2375 are elderly. There are 3584 active people and 2384 inactive. The ARU strategies include the analysis of the PERU strategic plan [45] and focus on heritage and housing conservation assessment, using color-coded categorizations to indicate levels of building degradation (see Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

ARU of Soure, limitation in 2012 (pp. 22 and 28 [43]): (a) Delimitation of the ARU of Soure; (b) ARU’s Building degradation levels, where buildings are good (in yellow), reasonable (in pink), bad (in red), ruined (in brown), and in construction (grey).

The initial strategies of the ARU (Urban Rehabilitation Area) were implemented in 2016, focusing on the rehabilitation of urban areas, particularly buildings that were degraded or functionally inadequate. These efforts aimed to improve the habitability and functionality of the urban building stock, enhance public spaces, and promote accessibility for citizens with reduced mobility. The provision of houses has been supported by the ELH Program and the Public Affordable Housing Program to ensure access to adequate and affordable housing. In 2018, the ARU’s intermediate strategies introduced regulations on (i) acquisition of vacant buildings for rehabilitation and rental; (ii) promotion of façade conservation, (iii) revision of tax incentives, and (iv) implementation of energy efficiency standards in buildings. Up to today, the strategies outlined for the ARU have not yet been fully executed. The Municipal Master Plan (PDM) of Soure [46] places particular emphasis on the protection of buildings, ensembles of public or municipal interest, and designated heritage sites, as well as on establishing buffer zones around listed buildings [26,27,28]. It also reinforces a commitment to sustainable development, underpinned by circular economy strategies and compliance with energy efficiency standards.

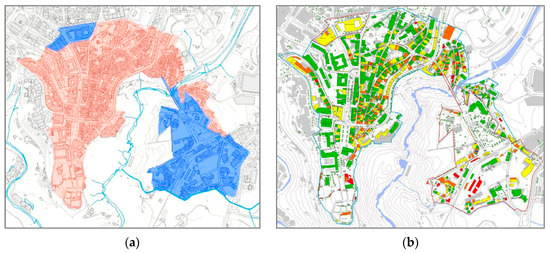

4.4. ARU from Historic Center of Vila Real

The ARU of Vila Real City’s historic centre belongs to Vila Real City and District and the Northern region of Portugal. The ARU delimitation has undergone three periods (2014, 2017, and 2021). The geometrical configuration of the ARU has changed from 36.4 ha in 2017 to 55.67 ha in 2021, adding two new areas (Figure 6a). The ARU’s physical characteristics are compounded by 1014 buildings, of which 542 are occupied and 472 are vacant and/or in ruin. Social analysis shows that ARU has 1981 inhabitants, of whom 1193 are adults and 556 are elderly. There are 1193 active people and 731 inactive. The ARU strategies [47] include the analysis of the PARU strategic plan, focusing on heritage and housing conservation assessment (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

ARU and PERU de Vila Real [25]: (a) ARU delimitation 2021 (p. 3 [44]; (b) Buildings’ state of conservation: excellent/very good (green); reasonable (yellow); bad (orange); very bad (red) (plan 05 [25]).

In the initial ARU strategies, the local authorities were focused on assessing the safety and housing conditions of the existing housing stock, and mainly the buildings’ façades (paper records). Despite these efforts, the absence of targeted measures for interior refurbishment of buildings was a gap, because many buildings in the historic centre are severely degraded, abandoned, or in ruins. The residents are economically and socially vulnerable, which supports the need for building rehabilitation expenses.

The intermediate ARU strategies were created in 2021. The local authorities have responded by launching the ELH program [39], which aims to foster community participation and provide essential social support to those needing housing. Therefore, new aims are pointed out from the previous version in 2017: (i) ensure preservation of the cultural heritage of the area, through heritage values identification; (ii) develop new solutions to ensure access to decent housing (ELH); (iii) implement energy efficiency standards in both public and private buildings; improve accessibility for citizens with reduced mobility; tax incentives updates. Up to today, the strategies outlined for the ARU have not yet been fully executed. In addition, the Vila Real PDM [48] is concerned with territorial cohesion by affirming the city as the main regional centre, focusing on environmental quality and the built heritage through its preservation.

4.5. ARU from Devesas

The Devesas ARU, located in the city of Vila Nova de Gaia within the Porto District and the Northern Region of Portugal, covered an area of 30.30 hectares as of 2022. The ARU includes a total of 310 buildings, of which 230 are occupied, while 80 are either vacant or in a state of ruin. According to social analysis, the ARU is home to approximately 5000 residents, including 3750 adults and 1250 elderly individuals. In terms of economic activity, the population includes 1754 active individuals and 528 classified as inactive.

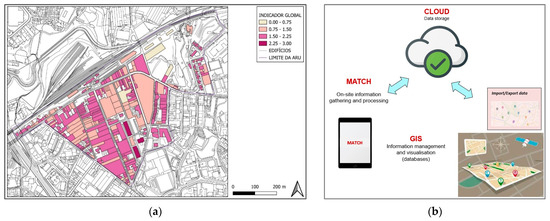

The initial ARU strategies implemented in 2019 focused on the rehabilitation of buildings and urban spaces, enhancing safety and housing conditions, and identifying heritage values for preservation. The intermediate ARU strategies were implemented in 2022 by introducing digital transition in administrative services and the SIMPLEX [37] procedures. In addition, the ARU’s strategies are focused on housing stock rehabilitation, implementing energy efficiency standards, and providing access to decent and affordable houses. The ARU of Devesas is aligned with Vila Nova de Gaia PDM [49], since one of the priorities is that of urban regeneration operations, restructuring the main connection routes from Vila Nova de Gaia to the larger territory.

Therefore, Vila Nova de Gaia is part of a pilot project developed in collaboration between GaiUrb (Municipal Office) and the Institute for Sustainable Construction (ICS) at FEUP (Faculty of Engineering, University of Porto). This initiative has resulted in two technical reports [50,51] and was supported by the ongoing research project MATCH (Monitoring and Assessment Tool for Cultural Heritage), which supported building assessment from 2022 until 2024, including the interior/exterior, and public spaces of the ARU Area (Figure 7a) in diverse dimensions, safety and housing conditions, and social and heritage values identification [52]. The statistical procedures can provide diverse levels of information on the indicators from these different dimensions (Figure 7a). In addition, the on-site digital data can provide actual information to the municipal database (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

The ARU of Devesas and MATCH Tool: (a) ARU Devesas Buildings’ Overall Indicator of the assessed five dimensions [51].; (b) Prototype of the MATCH tool procedure and its integration with municipal databases for real-time data generation on a Geographic Information System (GIS) geoportal (a, b, 1st author’s schemes).

Additionally, the digital procedures implemented in the Devesas ARU are crucial for streamlining administrative processes [37] and can serve as a model for other municipalities. The digital monitoring system, supported by a shared database, facilitates the exchange of strategies and best practices among local actors.

4.6. Outcomes from the ARU Analyses

A brief comparative analysis is presented, highlighting key outcomes from the ARU, including physical characteristics (area size, total number of buildings, and the number of occupied and vacant residential units), social profile (population size, age distribution, and activity status), and urban rehabilitation strategies aligned with the PDM objectives (see Table 3).

Therefore, the previous analysis (Table 3) highlights that the ARUs have different particularities (e.g., different contexts, physical characteristics, social profiles, urban strategies). Also, different PDM aims include European standards related to the circular economy, energy efficiency, and affordable houses across the Portuguese territory. A SWOT analysis aims to highlight the particularities between the ARUs (see Table 4).

A transition to more comprehensive analyses of buildings is essential, going beyond the “one size fits all” methodology evident in case studies such as the ARUs of Belmonte, Penacova, and Soure. While Vila Real’s Historic City Centre ARU has made progress by ensuring fair and affordable rents for a specified period, mitigating real estate speculation, and fostering balanced urban regeneration, its efforts remain limited in scale. Additionally, integrating local housing strategies (ELHs) that promote new housing construction represents a step forward, but is not yet widespread across national municipalities.

A notable example of innovation is the Devesas ARU in Vila Nova de Gaia, where local authorities have significantly advanced urban planning through the standardization and digitalization of data via a comprehensive geoportal inserted in the SIMPLEX program. This initiative integrates multiple data layers, such as building stock and public spaces, to provide a holistic perspective. Furthermore, digital assessment tools and data enhance the real-time monitoring and management of cultural heritage assets.

5. Discussion

The analysis demonstrates that Urban Rehabilitation Areas (ARUs) serve as essential tools for promoting territorial cohesion, social inclusion, and cultural preservation. Despite variations in scale, demographic profiles, and implementation timelines, the five ARUs analysed reveal a common focus on building rehabilitation, social revitalization, and heritage conservation. These priorities are pursued through phased, data-informed, and context-sensitive strategies, reflecting a growing emphasis on locally tailored urban renewal approaches.

The comparative findings highlight both shared objectives and distinct strategies shaped by each city’s physical and historical characteristics. This differentiated yet aligned approach is critical for ensuring an adequate and appropriate housing supply that responds to local needs. In this context, the study supports the research hypothesis that ARUs can create significant opportunities for local management in both housing provision and preservation.

Moving forward, the impact of ARUs can be further amplified through integrated platforms, digital tools, and inter-municipal cooperation. While the full benefits of these initiatives will depend on long-term commitment, sustained funding, and inclusive governance, the findings affirm that ARUs possess strong potential to shape resilient, equitable, and culturally rich urban environments.

5.1. ARUs in Housing Provision and Preservation

Local actors within the Urban Rehabilitation Areas (ARUs) implement phased, multifaceted strategies tailored to each area’s specific needs, primarily focusing on improving building conditions and habitability before addressing broader social and economic goals. All ARUs emphasize rehabilitating deteriorated buildings to enhance living conditions, with examples like Belmonte’s early restoration efforts and Vila Real’s diagnostic mapping guiding targeted interventions. Heritage preservation is also key, as seen in Penacova’s façade restoration program, which improves housing quality while maintaining cultural identity. To combat vacancy/abandonment, Soure ARU has introduced acquisition and rental programs that support affordable housing and social revitalization. Energy efficiency upgrades and updated tax incentives, employed by ARUs like Vila Real and Devesas, make rehabilitation more sustainable and financially viable. Additionally, Devesas integrates digital tools for real-time monitoring, improving urban management, and indirectly supporting housing quality. All these strategies are aligned with broader municipal master plans, ensuring a balanced approach that promotes sustainable housing provision alongside cultural preservation and territorial cohesion, answering research question Q1. Moreover, the actors need a more targeted and flexible approach to regulation, which could address spatial inequalities, prioritize rehabilitation in the most at-risk areas, and adapt to economic challenges to ensure sustainable housing development.

Furthermore, the broad and ambiguous land-use reclassification criteria outlined in Decree-Law No. 117/2024 [34], in its current form, raise concerns about the capacity of municipal and intermunicipal authorities to effectively and appropriately reclassify land for new housing provision and preservation actions in existing examples in urban areas.

5.2. ARUs and ELH Strategies

When effectively oriented, ARU strategies can be integrated with local housing strategies to balance urban rehabilitation and develop adequate housing solutions. For instance, the outputs of the ARUs in Soure and Vila Real illustrate the challenges in intervening in historic city centres, which include high maintenance costs and the need for specialized interventions. However, with support from European programs like the ELH, these areas can be revitalized and reintegrated as viable residential spaces. In the case of Vila Real’s City Centre ARU, despite its decline, there is significant potential for revitalization through building rehabilitation and development of affordable housing. This is because housing accessibility has been a growing issue, exacerbated by the pandemic and the economic fallout from the war in Ukraine. Rising inflation and interest rates have disproportionately impacted vulnerable families, intensifying the need for housing support and improvement.

Addressing a broad range of housing solutions—from smaller units to larger multifamily homes—is required. The Local Housing Strategy (ELH) [39] plays a central role in shaping housing provision and preservation policies, focusing on rehabilitation and rental housing. The ELH, aligned with national policies such as the Strategic Urban Development Plan and the New Generation of Housing Policies (NGHP), can prioritize the following: (i) the rehabilitation of social housing; (ii) the expansion of the public housing supply; and (iii) assistance to those under the 1° Right Housing Access Support Program.

Moreover, municipalities are not fully connecting the potential of ARU plans, particularly in housing promotion. While these tools are critical to urban regeneration, their integration into Local Housing Strategies (ELH) is often delayed due to concerns over effectiveness, which can deter investment in social and low-cost housing projects.

To address these challenges, alternative models should be explored: (i) Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) to encourage collaboration between the public and private sectors; (ii) Housing cooperatives, which give residents more control over the rehabilitation and maintenance of their homes; and (iii) Local associations, such as Just a Change, that foster community involvement and social inclusion in urban regeneration. By incorporating these models into ARU strategies, municipalities can better balance the rehabilitation of existing housing stock with new housing provision, and answer question Q2. This approach will help ensure that ARUs become more inclusive, sustainable, and effective tools for housing promotion, addressing both immediate and long-term local and regional needs.

5.3. The ARUs’ Role in Local Management

While the strategic potential of ARUs is recognized, it is often overshadowed by large-scale construction proposals that fail to consider the residential potential within ARUs. Despite some ARUs being classified for over a decade, their housing potential remains largely untapped. Moreover, urban rehabilitation guidelines for ARUs, such as those developed for Devesas in Vila Nova de Gaia, are still evolving. These guidelines, which draw on technical expertise, are essential for promoting sustainable urban interventions that balance economic, social, and environmental objectives at the municipal and regional levels.

A significant challenge remains the ineffective valorisation of ARU strategies across municipal, regional, and national levels. Municipal management is slowly shifting towards digital platforms [37]. Devesas in Vila Nova de Gaia can integrate ARUs outputs in the geoportal, for technicians and citizens’ consultation. Consequently, digital tools help create adaptable management frameworks that respond effectively to evolving social, economic, and environmental needs within ARUs. Moreover, answering question Q3, a robust regional cross-referencing data is essential to meet national standards in the housing crisis. Addressing these issues requires a systematic, coordinated approach to rehabilitation, guided by clear top-down criteria, while tailoring ARU strategic plans to the regions’ specific characteristics and needs. By recognizing and fully harnessing the potential of ARUs, municipalities can better integrate urban rehabilitation with housing promotion, fostering more sustainable and inclusive urban growth and dynamization.

Moreover, municipal legal frameworks could enhance flexibility in ARU implementation by adopting adaptive policies that balance national regulatory requirements with local realities, achieved through diverse mechanisms, such as localized zoning adjustments, streamlined processes for permitting rehabilitation projects, and targeted tax incentives that encourage private investment while safeguarding heritage preservation. Flexibility also involves collaborative governance models that engage stakeholders, including all actors in the decision-making process. Aligning these flexible municipal measures with the broader PDMs ensures coherence with national goals while addressing unique local challenges. This approach enables municipal technicians to tailor interventions that maximize social inclusion, housing provision, and built heritage preservation within the legally defined framework.

Therefore, answering question Q4, the ARUs, when strategically designed, could play a critical role in aligning local housing strategies with broader regional and national objectives, addressing housing shortages, and promoting long-term urban regeneration.

6. Conclusions

While extensive research from countries such as Italy and the UK highlights diverse perspectives on housing provision and preservation, it also reveals a notable limitation: a lack of flexible, integrative frameworks that can be easily adapted or replicated across different urban contexts due to distinct national planning paradigms and localized challenges. These studies often focus on participation, heritage risk, environmental pressures, and digital innovations but fall short in offering generalized or scalable strategies. In contrast, the comparative analysis of Portugal’s five Urban Rehabilitation Areas (ARUs) demonstrates that, despite varying scales, demographic profiles, and phased timelines, local initiatives can effectively integrate housing provision, urban revitalization, and heritage preservation. The ARUs embody a pragmatic, context-sensitive approach that balances sustainable community development with cultural conservation, aligned with Portugal’s broader policy emphasis on expanding affordable housing, energy efficiency, and real estate regulation.

The findings underscore the need for a paradigm shift in public policy and urban planning, one that prioritizes reducing bureaucratic obstacles and fostering more adaptive, locally tailored ARUs. Aligning ARUs with the particularities of their realities is crucial to promoting a sustainable, equitable, and inclusive urban environment. The alignment of the ARU strategies with Municipal Master Plans (PDMs) reflects a coherent vision for long-term development, while targeted programs—ranging from façade restoration to digital heritage monitoring—illustrate the adaptability of ARUs to local needs. However, the persistent challenges of building vacancy, aging populations, and uneven program completion highlight the need for stronger inter-municipal collaboration, stable funding, and community engagement. Ultimately, the success of ARUs will rely on their ability to evolve into collaborative, data-informed, and socially responsive frameworks, ensuring that urban rehabilitation not only preserves the past but actively shapes a more resilient and liveable future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.O. and C.F.; methodology, C.O.; EHL investigation, A.M.; ARU resources, C.O. and C.F.; data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review, editing, and funding acquisition by C.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work carried out by the author Cilísia Ornelas is funded by FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology, Portugal, co-financed by the European Social Fund, through the Scientific Employment Stimulus Program, with reference: 2021.01733.CEECIND/CP1679/CT0015 (https://doi.org/10.54499/2021.01733.CEECIND/CP1679/CT0015); and financially supported by UID/04708 of the CONSTRUCT—Instituto de I&D em Estruturas e Construções—funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P./MCTES through national funds.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vila Nova de Gaia Municipality Administration for allowing the use of the graphic material in the manuscript, as well as all the contributions made by local technicians. Special credits go to the Institute for Sustainable Construction (ICS-FEUP), which collaborated with the main author of this paper on the work carried out in the Devesas ARU in Vila Nova de Gaia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations (descriptive in Portuguese) are used in this manuscript:

| ARU | Urban Rehabilitation Areas |

| ELH | Local Housing Strategies |

| IMI | Municipal Property Tax |

| ICOMOS | International Council on Monuments and Sites |

| IMT | Municipal Transaction Tax |

| MATCH | Monitoring and Assessment Tool for Cultural Heritage |

| NGHP | New Generation of Housing Policies |

| ORU | Urban Rehabilitation Operations |

| PAICD | Action Plan for Disadvantaged Communities |

| PARU | Urban Rehabilitation Action Plan |

| PEDU | Urban Development Strategic Plan |

| PERU | Urban Rehabilitation Strategic Plan |

| PDM | Director Master Plan |

| PROT | Regional Land-Use Plan |

| PRR | Recovery and Resilience Plan |

| RJIGT | Legal Regime for Land Management Instruments |

| SRU | Urban Rehabilitation Societies |

| UI | Intervention Units |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. |

| VAT | Value Added Tax |

References

- Varady, D.P.; Matos, F. Comparing public housing revitalization in a liberal and a Mediterranean society (US vs. Portugal). Cities 2017, 64, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas, C.; Miranda Guedes, J.; Vázquez, I. Cultural built heritage and intervention criteria: A systematic analysis of building codes and legislation of Southern European countries. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 20, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S. Divergence in planning for affordable housing: A comparative analysis of England and Portugal. Prog. Plan. 2022, 156, 100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garha, N.S.; Azevedo, A.B. Demography and Housing: Challenges and opportunities for Lisbon’s housing prospects from 2022 to 2051. Cities 2025, 158, 105665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, B.; de Castro Neto, M.; Magalhães de Sousa, N.; Barriguinha, A.; Sarmento, P. An indicator for integrated regional planning: A case study of Portugal’s west region. Cities 2025, 159, 105762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarsi, E. A critical perspective on policies for informal settlements in Portugal. Cities 2020, 107, 102949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, M.; Carreiras, M.; Alves, S. Decoding the spatial dynamics of sales and rental prices in a high-pressure Portuguese housing market: A random forest approach for the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. Cities 2025, 158, 105631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egusquiza, A.; Ginestet, S.; Espada, J.C.; Flores-Abascal, I.; García-Gáfaro, C.; Soto, C.G.; Claude, S.; Escadeillas, G. Co-creation of local eco-rehabilitation strategies for energy improvement of historic urban areas. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Porto, F.; Munari, M.; Prota, A.; Modena, C. Analysis and repair of clustered buildings: Case study of a block in the historic city centre of L’Aquila (Central Italy). Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 1221–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, F.; De Falco, A.; Cutini, V. Rethinking earthquake-related vulnerabilities of historic centres in Italy: Insights from the Tuscan area. J. Cult. Herit. 2022, 54, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardella, L.; Sebastiani, A.; Stafoggia, M.; Buonocore, E.; Paolo Franzese, P.; Manes, F. Modeling regulating ecosystem services along the urban–rural gradient: A comprehensive analysis in seven Italian coastal cities. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 165, 112161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaffarelli, G.; Vagge, I. Cities vs. countryside: An example of a science-based peri-urban landscape features rehabilitation in Milan (Italy). Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 86, 128002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micelli, E.; Pellegrini, P. Wasting heritage. The slow abandonment of the Italian Historic Centers. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 31, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, A. Tourism-driven displacement in Naples, Italy. Land Use Policy 2023, 134, 106919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, E.; Turati, F.; Colombo, B.; Schito, E. Heritage-driven urban regeneration: The example of casa Macchi in Morazzone (Italy). Cities 2025, 165, 106070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anelli, D.; Tajani, F. Valorization of cultural heritage and land take reduction: An urban compensation model for the replacement of unsuitable buildings in an Italian UNESCO site. J. Cult. Herit. 2022, 57, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertacchini, E.; Revelli, F.; Zotti, R. The economic impact of UNESCO World Heritage: Evidence from Italy. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2024, 105, 103996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loro, S.; Lo Verso, V.R.M.; Fregonara, E.; Barreca, A. Influence of daylight on real estate housing prices. A multiple regression model application in Turin. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, R.; Coluccia, B.; Natale, F. How are smart city policies progressing in Italy? Insights from SDG indicators. Land Use Policy 2025, 148, 107386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallent, N.; Stirling, P.; Hamiduddin, I. Pandemic mobility, second homes and housing market change in a rural amenity area during COVID-19—The Brecon Beacons National Park, Wales. Prog. Plan. 2023, 172, 100731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, H.X.; Sadick, A.-M.; Noguchi, M. A systematic review of key issues influencing the environmental performance of social housing. Energy Build. 2024, 319, 114566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeddu, M.; Clifford, B. The conversion of buildings to housing use: England’s permitted development rights in comparative perspective. Prog. Plan. 2023, 171, 100730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R.; Jensen, L.B.; Ryberg, M. Using digitized public accessible building data to assess the renovation potential of existing building stock in a sustainable urban perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESPON. House for All: Access to Affordable and Quality Housing for All People. Co-Funded by the European Union, Interreg. 2024. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/projects/access-affordable-and-quality-housing-all-people-house4all (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Ministry of Planning and Territorial Administration. Programme for the Recovery of Historic Villages in Portugal: Pilot Action to Promote Regional Development Potential/Ministry of Planning and Territorial Administration, Ministry of Trade and Tourism; Ministry of Trade and Tourism: Lisbon, Portugal, 1994; 16p, ISBN 9729604509.

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; The General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 1972; Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/convention-concerning-protection-world-cultural-and-natural-heritage (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- ICOMOS. Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas; International Council on Monuments and Sites: Washington, DC, USA, 1987; Available online: http://jikimi.cha.go.kr/english/img/sub06/multi/icomos02.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- European Council. Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe; European Council: Brussels, Belgium, 1975. Available online: http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/EN/Treaties/Html/121.htm (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Ministry of Public Works, Transportation and Communications. Decree-Law 321-B: Urban Lease Regime; Series I (238): 4286-(1-23); Official Gazette: Lisbon, Portugal, 1990. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/321-b-1990-667147 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Assembly of the Republic. Law 6: New Urban Lease Regime (NRAU); I Série A 41; Diário da República: Lisbon, Portugal, 2006; pp. 1558–1587. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/6-2006-693853 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Ministry of Ambiente, Ordenamento do Território e Energia. Decree-Law 555: Legal Regime for Urbanization and Edification (and Respective Updates); I Série 173; Diário da República: Lisbon, Portugal, 1999; pp. 4809–4860. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/555-1999-655682 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Assembly of the Republic. Law No. 32/2012, 14th August, Makes the First Amendment to Decree-Law 307/2009 of 23 October, Which Establishes the Legal Framework for Urban Rehabilitation, and the 54th Amendment to the Civil Code, Approving Measures to Speed Up and Boost Urban Rehabilitation. 2012. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/32-2012-175306 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Almeida, C.P.; Ramos, A.F.; Silva, J.M. Sustainability assessment of building rehabilitation actions in old urban centres. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 36, 78–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidency of the Council of Ministers. Decree-Law No. 117/2024, 30 December, Amends Legal Framework for Territorial Management Instruments, Approved by Decree-Law No. 80/2015, 14 May; Series I (252); Diário da República: Lisbon, Portugal, 2024; pp. 1–8. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/117-2024-901535572 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment, Spatial Planning and Energy. Decree-Law No. 80/2015: Legal Framework for Territorial Management Instruments—RJIGT; Series I (93); Diário da República: Lisbon, Portugal, 2015; pp. 2459–2512. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/80-2015-67212743 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Assembly of the Republic. Law No. 31/2014, 30 May, Law on the General Bases of Public Policy on Soil, Spatial Planning, and Urbanism; Series I (104); Diário da República: Lisbon, Portugal, 2014; pp. 2988–3003. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/31-2014-25345938 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Measures for Urban Planning, Spatial Planning, and Industry. Available online: https://www.simplex.gov.pt/medidas (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Portas, N. O Processo SAAL entre o Estado e o Poder Local. Rev. Crítica Ciências Sociais 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ordinance 230. 1.º Right-Support Programme for Access to Housing (ELH). Decree-Law 37/2018; Series I (158); Diário da República: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018; pp. 4216–4223. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/analise-juridica/decreto-lei/37-2018-115440317 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- CCDRC/DSOT. Guia Orientador da Revisão do PDM. (Coord. Bento, Maria & Santos, Carla). 2019. Available online: https://www.ccdrc.pt/pt/ (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Belmonte Municipality. Delimitation of the Belmonte ARU and Belmonte ORU—Strategic Urban Rehabilitation Programme, Território XXI. 2021. Available online: https://www.cm-belmonte.pt (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Belmonte City Council. Director Master Plan (PDM). Plan Regulations, 1st Revision, Final Version; Belmonte City Council: Belmonte, Portugal, December 2023. Available online: https://cm-belmonte.pt/pdmbelmonte/ (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Penacova Municipality and Parish. Proposal for the Delimitation of the Urban Rehabilitation Area (ARU), Descriptive and Justifying Memorandum. 2015. Available online: http://www.cm-penacova.pt/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Penacova City Council. Director Master Plan (PDM). Plan Regulations, 1st Revision; Penacova City Council: Penacova, Portugal, August 2015; Available online: http://www.cm-penacova.pt/pt/pages/primeirarevisaopdm (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Soure Municipality. Strategic Urban Rehabilitation Programme. 2018. Available online: https://www.cm-soure.pt/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Soure Council. Director Master Plan (PDM). Plan Regulations, 5th Revision, Final Version; Soure Council: Soure, Portugal, 2018; Available online: https://cm-soure.pt/plano-diretor-municipal-pdm-de-soure/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Vila Real Municipality. Operation of Urban Rehabilitation (ORU) of the Historic Centre of Vila Real. 2021. Available online: https://ru.cm-vilareal.pt/images/ORUS/centro_historico/1_Relatorio_PERU/RELATORIO_PERU_ORU_CH_VFinal.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Vila Real Council. Director Master Plan (PDM). Plan Regulations, Final Version; Vila Real Council: Vila Real, Portugal, 2024. Available online: https://www.cm-vilareal.pt/index.php/plano-diretor-municipal (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Vila Nova de Gaia Council. Director Master Plan (PDM). Plan Regulations, 4th Revision, Final Version; Vila Nova de Gaia Council: Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal, 2024. Available online: https://www.gaiurb.pt/pages/751 (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Ornelas, C.; Miranda Guedes, J.; Varum, H. Application of the MATCH Tool to the Devesas Quarter; Phase 1—Technical Report (Not Available for Public Consultation); ICS-FEUP: Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ornelas, C.; Miranda Guedes, J.; Varum, H. Application of the MATCH Tool to the Devesas Quarter; Phase 2—Technical Report (Not Available for Public Consultation); ICS-FEUP: Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ornelas, C.; Sousa, F.; Miranda-Guedes, J.; Breda-Vázquez, I. Monitoring and Assessment Heritage Tool: Quantify and classify urban heritage buildings. Cities 2023, 137, 104274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).