Alignment Between Standards and Job Market Demand for BIM Careers

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To what extent are the BIM roles defined by standards (e.g., UNI 11337-7) actually used in the titles and content of job advertisements in the Italian market?

- Is there an overlap between employers’ expectations and the role descriptions provided by the relevant standards?

- Which quantitative methodology could be implemented for analyzing this phenomenon?

2. Background

2.1. Role Clarity in BIM

2.2. Competency Frameworks

2.3. Educational Alignment and Job Advertisement Analysis

2.4. Focus on Italian Standard

- CDE Manager: data collaboration environment manager is responsible for the data collaboration environment implemented by the organization they belong to, or contractually required for a specific project by another party.

- BIM Manager: manager of digitalized processes, primarily deals with the organizational level regarding the digitalization of the processes carried out by the organization. They may have the supervision or overall coordination of the ongoing project portfolio. Appointed by the organization’s leadership, they define the BIM instructions and the way the digitalization process impacts the organization and its tools.

- BIM Coordinator: coordinator of project information flows works at the level of a single project in collaboration with the organization’s leadership and under the direction of the Manager of Digitalized Processes.

- BIM Specialist: advanced operator of information management and modeling, typically works within individual projects, collaborating either regularly or occasionally with a specific organization.

3. Methodology

- the collection of the dataset;

- the analysis of the UNI 11337-7 standard to define benchmarks for evaluating the potential misalignment;

- the dataset process according to the benchmarks;

- the analysis of results.

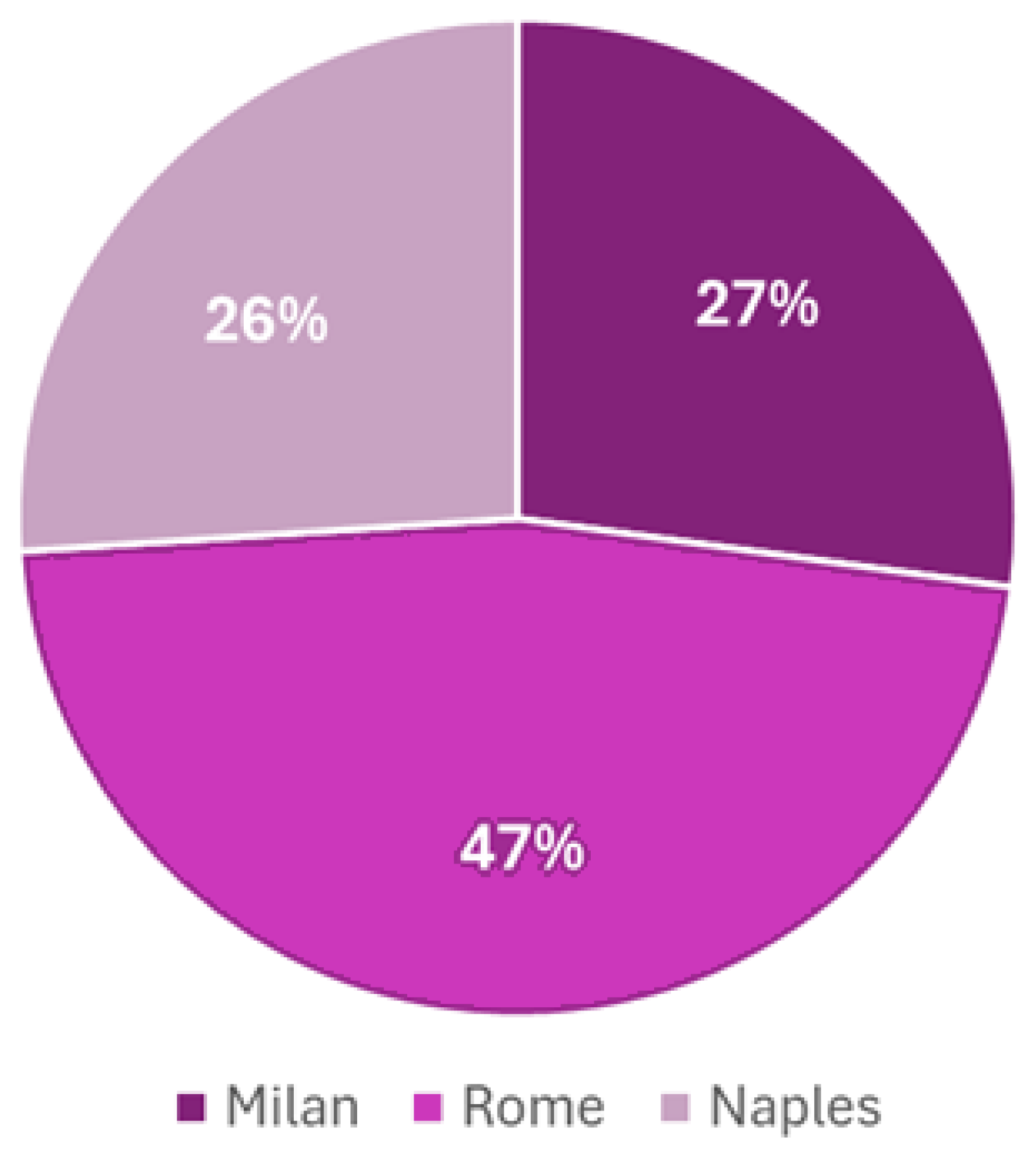

3.1. Retrieving Job Advertisement Dataset

3.2. Definition of Benchmarks

- BIM specialist: focused on modeling activities, use of BIM software, and production of technical documentation;

- BIM Coordinator: emphasizes coordination across different disciplines, management of models, and verification of data integrity;

- BIM Manager: concerns the strategic management of the BIM process, including implementation, supervision, and overall coordination of projects.

- CDE Manager: relates to the management of the Common Data Environment, including data exchange, collaboration processes, and ensuring data security.

3.3. Processing the Dataset

4. Results

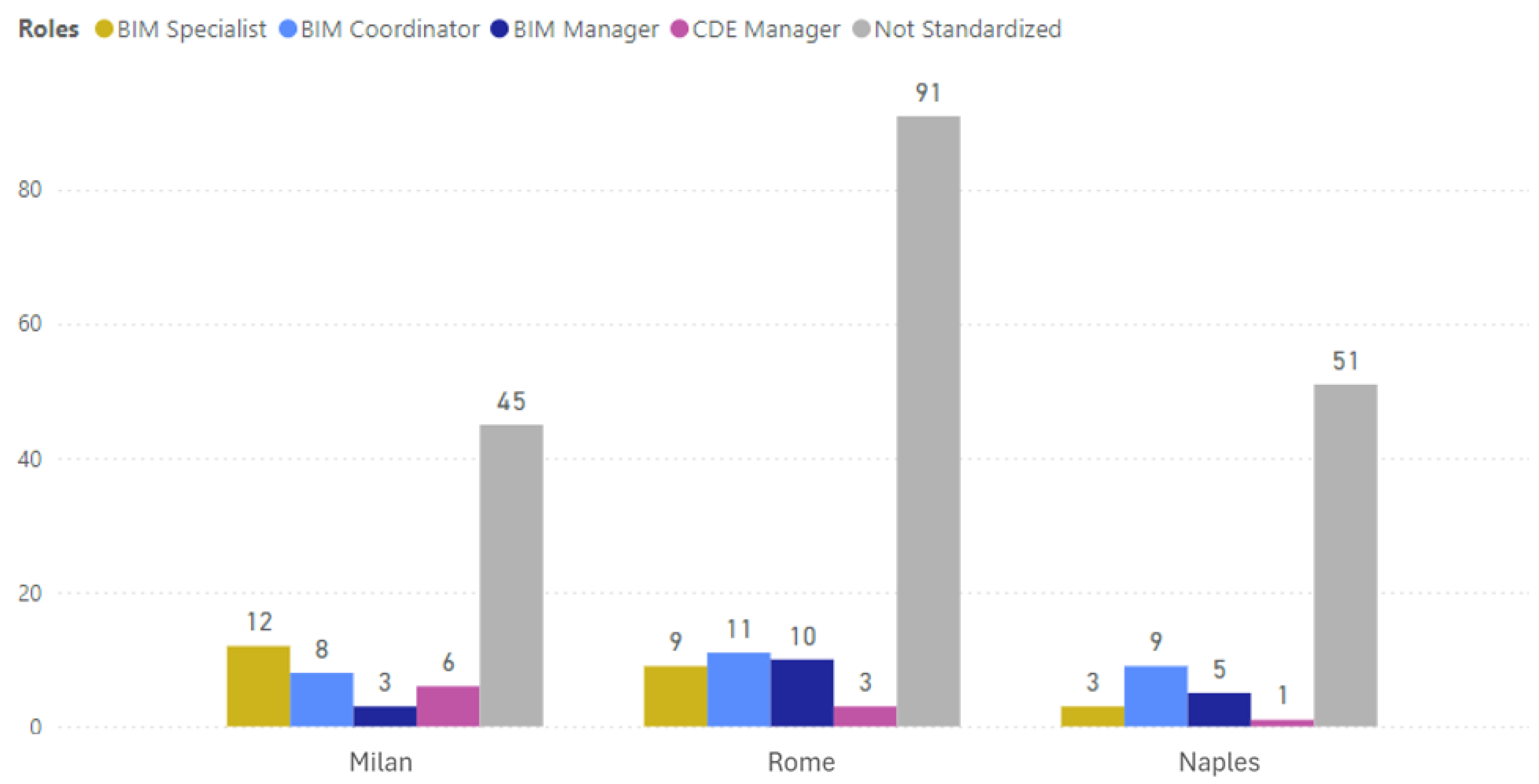

4.1. Job Advertisement Title Analysis

4.2. Job Advertisement Content Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings

5.2. Limitations and Generalizability of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borrmann, A.; König, M.; Koch, C.; Beetz, J. Building Information Modeling: Technology Foundations and Industry Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; 584p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, M.; Liu, C.; Li, A.; Guo, B. Listen to the Companies: Exploring BIM Job Competency Requirements by Text Mining of Recruitment Information in China. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 04023076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiamma, P.; Biagi, S. Critical Approaches on the Changes Taking Place after 24/2014/EU in BIM Adoption Process. Buildings 2023, 13, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitera-Kiełbasa, E.; Zima, K. BIM Policy Trends in Europe: Insights from a Multi-Stage Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.M.; Khanzode, A.R. Examples of How Building Information Modeling Can Enhance Career Paths in Construction. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2014, 19, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Sijtsema, P.M.; Gluch, P.; Sezer, A.A. Professional development of the BIM actor role. Autom. Constr. 2019, 97, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 19650-1:2018; Organization and Digitization of Information About Buildings and Civil Engineering Works, Including Building Information Modelling (BIM)—Information Management Using Building Information Modelling—Part 1: Concepts and Principles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Kaya, U.; Önder Özener, O. A strategic evaluation of BIM-driven information management in the context of ISO 19650-2 standard. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.; Wilkinson, S.; McMeel, D. A review of specialist role definitions in BIM guides and standards. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2017, 22, 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- Succar, B. Building information modelling framework: A research and delivery foundation for industry stakeholders. Autom. Constr. 2009, 18, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, M.; Succar, B. Macro BIM adoption: Comparative market analysis. Autom. Constr. 2017, 81, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VDI-Gesellschaft Bauen und Gebäudetechnik. VDI 2552 Blatt 1—Building Information Modeling—Grundlagen; Düsseldorf, Germany. 2020. Available online: https://www.vdi.de/en/home/vdi-standards/details/vdi-2552-blatt-1-building-information-modeling-fundamentals (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- UNI 11337-7:2018; Edilizia e Ingegneria Civile—Gestione Digitale dei Processi Informativi delle Costruzioni—Parte 7: Requisiti di Conoscenza, Abilità e Competenze dei Ruoli Involti Nella Gestione e Modellazione Informativa. UNI: Milan, Italy, 2018.

- Wu, W.; Issa, R.R. BIM education and recruiting: Survey-based comparative analysis of issues, perceptions, and collaboration opportunities. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2014, 140, 04013014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolpagni, M.; Bosché, F.; de Boissieu, A.; Akbarieh, A.; Shaw, C.; Mêda, P.; Puust, R.; Seržantė, M.; Popov, V.; Sacks, R. An explorative analysis of European standards on building information modelling. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computing in Construction, Rhodes, Greece, 24–26 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, M.; Lee, G.; Jeon, B. An analysis of BIM jobs and competencies based on the use of terms in the industry. Autom. Constr. 2017, 81, 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, K.; Taiebat, M. BIM Experiences and Expectations: The Constructors’ Perspective. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2011, 7, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, E.A.; Pavard, A.; de Paula, N. Determining Factors Influencing BIM Adoption: A Competency-Driven Approach. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelseth, E. BIM understanding and activities. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2017, 169, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olowa, T.; Witt, E.; Lill, I.; Rasheed, A.; Abdulmumin, A.; Adebiyi, R. Critical Factors for Effective BIM-Enabled Education: An Adaptive Structuration Theory Perspective. Buildings 2023, 13, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolpagni, M.; Gavina, R.; Ribeiro, D.; Arnal, I.P. Shaping the Future of Construction Professionals. In Industry 4.0 for the Built Environment; Bolpagni, M., Gavina, R., Ribeiro, D., Eds.; Structural Integrity; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 20, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.K.S.; Suresh, S.; Heesom, D.; Suresh, R. BIM Education Framework for Clients and Professionals of the Construction Industry. Int. J. 3-D Inf. Model. 2017, 6, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbarkouky, M.M.G.; Fayek, A.R. Fuzzy Similarity Consensus Model for Early Alignment of Construction Project Teams on the Extent of Their Roles and Responsibilities. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2011, 137, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Thangasamy, V.K.; Hou, Z.; Tiong, R.L.; Zhang, L. Collaborative relationship discovery in BIM project delivery: A social network analysis approach. Autom. Constr. 2020, 114, 103147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantatmula, V.S. Project manager leadership role in improving project performance. Eng. Manag. J. 2010, 22, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Anantatmula, V.S. Empirical Study of Project Managers Leadership Competence and Project Performance. Eng. Manag. J. 2017, 29, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, M.A.; Chahrour, R.; Vukovic, V.; Dawood, N.; Kassem, M. Investigating the potential of delivering employer information requirements in BIM enabled construction projects in Qatar. IFIP Adv. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2016, 467, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PAS 1192-2:2013; Specification for Information Management for the Capital/Delivery Phase of Construction Projects Using Building Information Modelling. BSI: London, UK, 2013.

- Mathews, M. Defining Job Titles and Career Paths in BIM. In Proceedings of the CITA BIM Gathering 2015, Dublin, Ireland, 12–13 November 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, U.E.; Nasir, A.R.; Ullah, F.; Qayyum, S.; Thaheem, M.J. BIM Roles and Responsibilities in Developing Countries: A Dedicated Matrix for Design-Bid-Build Projects. Buildings 2022, 12, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draganidis, F.; Chamopoulou, P.; Mentzas, G. An Ontology Based Tool for Competency Management and Learning Paths. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Knowledge Management (I-KNOW 06), Vienna, Austria, 6–8 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, M.; Weigel, T.; Collins, K. The concept of competence in the development of vocational education and training in selected EU member states: A critical analysis. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2007, 59, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succar, B.; Sher, W.; Williams, A. An integrated approach to BIM competency assessment, acquisition and application. Autom. Constr. 2013, 35, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, G.; McCuen, T.; Hannon, J.; Smith, D. Development of the BIM Body of Knowledge (BOK) Task Definitions and KSAs for Academic Practice. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual International Conference, Liverpool, UK, 14–18 April 2020; Volume 1, pp. 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiza, M.T. The Impact of Building Information Modelling (BIM) in the Construction Industry. Brill. Eng. 2024, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Lu, W.; Rowlinson, S.; Zhang, X. Development of a Multifunctional BIM Maturity Model. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 06016003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, F.Y.Y.; Hartmann, A.; Kumaraswamy, M.; Dulaimi, M. Influences on Innovation Benefits during Implementation: Client’s Perspective. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2007, 133, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjoub, A.; Kruyen, P.M. Efficient recruitment with effective job advertisement: An exploratory literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 2021, 24, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, G.; Gubern, M.; Rodriguez, I. Recruitment advertising: The marketing-human resource interface. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 2000, 6, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, S.A.; Aigbavboa, C.O.; Ejohwomu, O.A. Understanding the BIM actor role: A study of employer and employee preference and availability in the construction industry. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 31, 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, M.; Raoff, N.L.A.; Ouahrani, D. Identifying and analyzing BIM specialist roles using a competency-based approach. In Proceedings of the Creative Construction Conference 2018, CCC 2018, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 30 June–3 July 2018; pp. 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.R.; Martek, I.; Papadonikolaki, E.; Sheikhkhoshkar, M.; Banihashemi, S.; Arashpour, M. Viability of the BIM Manager Enduring as a Distinct Role: Association Rule Mining of Job Advertisements. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godager, B.; Mohn, K.; Merschbrock, C.; Klakegg, O.J.; Huang, L. Towards an improved framework for enterprise BIM: The role of ISO 19650. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2022, 27, 1075–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, A.; Mirarchi, C.; Giani, M. BIM: Metodi e Strumenti. Progettare, Costruire e Gestire Nell’era Digitale; Tecniche Nuove: Milan, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M.; Manovskii, I.; Qiu, X. The Geography of Job Creation and Job Destruction; NBER Working Paper No. 29399; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Framework for Managing Multiple Common Data Environments. In Construction Research Congress 2024; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2024; Volume 1, pp. 1117–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthei, J.; Gölzhäuser, P.; Klemt-Albert, K.; Schulze, C.; Moharekpour, M.; Plattenteich, A. A common data environment for value-driven data management in German road construction. ce/papers 2023, 6, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Role | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) |

| CDE Manager | ‘ACDat’, ‘Modell.* ’, ‘Fluss.*’, ‘Protezion.*’, ‘analytics’, ‘interoperabil.*’, ‘CDE’, ‘Archivi.*’, ‘IFC’, ‘Coordinam.*’, ‘Gestione’, ‘Relazionare’, ‘Contenuti’, ‘Commessa’, ‘Correttezza’, ‘Tempestività’, ‘Tecniche’, ‘Difesa’, ‘Dati’, ‘Applicare’ | ‘Model.*’, ‘Flow.*’, ‘Protection.*’, ‘analytics’, ‘IFC’,’ACDat’, ‘interoperability’, ‘CDE’, ‘Archive.*’, ‘Coordination’, ‘Management’, ‘Reporting’, ‘Contents’, ‘Project’, ‘Accuracy’, ‘Timeliness’, ‘Technical’, ‘Defense’, ‘Data’, ‘Apply’ |

| BIM Coordinator | ‘Modell.*’, ‘Capitolat.*’, ‘gestione inform.*’, ‘Verific.*’, ‘IFC’, ‘interferenz.*’, ‘Conflitt.*’, ‘Clash’, ‘Check.*’, ‘commess*’, ‘Digitalizzat.*’, ‘Processo’, ‘Redigere’, ‘Piano’, ‘Offerta’, ‘Requisiti’, ‘Soggetti’, ‘Strumenti’, ‘Relazioni’, ‘Contrattuali’, | ‘Model.*’, ‘Specification.*’, ‘information management.*’, ‘Verification’, ‘IFC’, ‘interference.*’, ‘Conflict.*’, ‘Clash detection’, ‘Check.*’, ‘project.*’, ‘Digitization’, ‘Process’, ‘Draft’, ‘Plan’, ‘Offer’, ‘Requirements’, ‘Stakeholders’, ‘Tools’, ‘Relations’, ‘Contractual’ |

| BIM Manager | ‘IFC’, ‘Capitolat.*’, ‘gestione inform.*’, ‘Line.*’, ‘audit.*’, ‘contratt.*’, ‘Verific.*’, ‘svilupp.*’, ‘Report.*’, ‘Aziend.*’, ‘Coordinare’, ‘Supervisionare’, ‘Commesse’, ‘Stesura’, ‘Organizzazione’, ‘Promuovere’, ‘Programma’, ‘Formativo’, ‘Ricerca’, ‘Collaborare’ | ‘IFC’, ‘Specification.*’, ‘information management.*’, ‘Guidelines’, ‘audit.*’, ‘contract.*’, ‘Verification’, ‘development.*’, ‘Report.*’, ‘Company.*’, ‘Coordinate’, ‘Supervise’, ‘Projects’, ‘Drafting’, ‘Organization’, ‘Promote’, ‘Program’, ‘Training’, ‘Research’, ‘Collaborat.*’ |

| BIM Specialist | ‘Modell.*’, ‘Revit’, ‘Allplan’, ‘Tekla’, ‘IFC’, ‘Tavol.*’, ‘Elaborat.*’, ‘Progett.*’, ‘Model.*’, ‘Disegn.*’, ‘Oggetti’, ‘Applicativi’, ‘Analizzare’, ‘Capitolato’, ‘Conformarsi’, ‘Disciplinari’, ‘Tradurre’, ‘Verifica’, ‘Preliminare’, ‘Validare’ | ‘Model.*’, ‘Revit’, ‘Allplan’, ‘Tekla’, ‘IFC’, ‘Drawing.*’, ‘Drafting’, ‘Design.*’, ‘Model.*’, ‘Sketch.*’, ‘Objects’, ‘Software’, ‘Analyse’, ‘Specification’, ‘Compliance’, ‘Disciplinary’, ‘Translate’, ‘Verification’, ‘Preliminary’, ‘Validate’ |

| Role | Job Title Analysis | Processed Dataset Analysis | Double Role Addressed | Match Between Raw and Processed Dataset Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| BIM Specialist | 14 | 24 | 4 | 6 |

| BIM Coordinator | 2 | 28 | 5 | 0 |

| BIM Manager | 3 | 18 | 1 | 0 |

| CDE Manager | 0 | 10 | - | 0 |

| Not standardized | 242 | 187 | - | - |

| Total | 261 | 267 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gatto, C.; Barberio, G.; Cassandro, J.; Mirarchi, C.; Cavallo, D.; Pavan, A. Alignment Between Standards and Job Market Demand for BIM Careers. Buildings 2025, 15, 2323. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132323

Gatto C, Barberio G, Cassandro J, Mirarchi C, Cavallo D, Pavan A. Alignment Between Standards and Job Market Demand for BIM Careers. Buildings. 2025; 15(13):2323. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132323

Chicago/Turabian StyleGatto, Chiara, Giuseppe Barberio, Jacopo Cassandro, Claudio Mirarchi, Dalila Cavallo, and Alberto Pavan. 2025. "Alignment Between Standards and Job Market Demand for BIM Careers" Buildings 15, no. 13: 2323. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132323

APA StyleGatto, C., Barberio, G., Cassandro, J., Mirarchi, C., Cavallo, D., & Pavan, A. (2025). Alignment Between Standards and Job Market Demand for BIM Careers. Buildings, 15(13), 2323. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132323