1. Introduction

Incorporating the Collegiate Gothic style into the construction of university campuses has its historical roots in establishing medieval universities during the Middle Ages. This architectural style, marked by an enduring association with religion since its inception, is notably characterized by the architectural model of “introspective enclosed courts”, which has persisted within Oxford and Cambridge universities in England since the 14th century [

1]. Scholars attribute the origins of the Collegiate Gothic style to these universities, emphasizing its role in representing a venerable academic lineage [

2,

3].

By the late 19th century, significant transformations swept through the American educational landscape after the Civil War, marked by substantial large-scale construction initiatives [

4]. Between 1890 and 1915, educational institutions primarily focused on two stylistic paradigms in architectural and planning considerations: classical aesthetics, encompassing variants like Georgian, Art Nouveau, and Renaissance styles and Collegiate Gothic [

5], referencing the Gothic style within the broader Gothic Revival period.

The Collegiate Gothic style, which blended elements from the English Tudor Gothics with aspects of French Beaux-Arts traditions, emerged as a flexible and unstructured architectural language [

6]. Distinguished by vertical composition, towers, pointed arch windows, crenellations, large window bays, and oriel windows, this style more effectively accommodated the evolving educational needs and functionalities of the time, showcasing inherent flexibility in floor plans. It was referred to by various interchangeable names over different periods—Tudor Gothic, secular Gothic, late Gothic, or Collegiate Gothic style [

1].

Gradually, the Collegiate Gothic style became symbolic of the architectural tradition on American campuses, reflecting the values and practices of higher education in the United States [

7]. It can trace elements such as Tudor towers, oriels, and archways in Chicago’s and Yale’s buildings back to Oxford’s Magdalen College [

1].

In the late 19th to early 20th centuries, with the influx of British and American colonizers, the Western style was incorporated into modern Chinese university campus construction [

8]. Within the specific scope of this study, the term “Western style” is defined by its departure from traditional Chinese architectural aesthetics, encompassing both the aforementioned classical aesthetics and the Collegiate Gothic style, which is prevalent in American universities. Notable examples of these institutions include Saint John’s University (1879), Soochow University (1900), and the University of Shanghai (1906), among others. However, the collaboration between missionaries and colonizers during this period also led to anti-Christian movements in some areas of China [

9]. In this intricate context, some universities opted for an eclectic fusion of Chinese and Western styles to resonate better with the local population. In contrast, others directly embraced the Western style [

10].

In this dynamic context, Soochow University, founded in 1900, became a pivotal institution. Notably, missionaries from the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (M.E.C.S.) were not merely purveyors of religious doctrine [

11]. The university’s visionary founders conceived it not merely as a place of learning within walls but as a model and exemplar for higher education in China. Reverend Y.J. Allen, the founder of Soochow University, shared this vision during a General M.E.C.S. meeting in New Orleans in 1901:

“At Soochow University, we hope to have more than a mere school for the education of the pupils who come within its walls. We hope to have a model, an example of schools. That is a model of its kind, and I believe it is to be the progenitor of schools and the mother of pupils”

2. Review of Literature

In the Chinese context, the Collegiate Gothic style, as a product of modern Western cultural influence, consistently embodies a significant connection with the value of campus heritage. Feng Gang explores the influence of Collegiate Gothic style on Christian universities in modern China, focusing on critical elements like buttresses, towers, and battlements [

10]. Cai Ling, particularly examining the University of Shanghai, meticulously examines the campus development and the evolution of its Collegiate Gothic style, aiming to attract attention to the unique artistic value embedded in this Westernized campus [

13]. Yan Hong, adopting a transnational perspective, conducts a comparative analysis of the designs by Murphy at Yonsei University in Korea and the University of Shanghai in China. Hong emphasizes the obligation to reevaluate the value of cultural assets and advocates for suitable preservation methods that align with the contemporary era [

14].

While research on the Collegiate Gothic style within the context of these institutions has received significant attention [

13,

15,

16]. The focus on Soochow University has primarily centered on its founding histories and architectural lineages [

17], with less emphasis on comprehending the unique architectural styles embraced by Soochow University. Despite acknowledging the role of missionaries in introducing architectural styles, the intricate integration of these styles into broader missionary educational endeavors often receives insufficient attention.

This study addresses these gaps by exploring the unique status of Soochow University’s Anderson Hall within the broader context of modern Chinese Christian universities. The uniqueness of this study lies in connecting the dissemination of the Collegiate Gothic style with the missionary educational endeavors in Asia, intricately woven into the tumultuous historical context of China’s societal and cultural upheavals during the modern era. The exploration of the impact of colonialism on architectural choices and how these styles contributed to the modernization of educational institutions is central to our investigation. It is imperative to recognize that architectural style research extends beyond mere façade elements, encompassing the cultural and political backdrop that contributes to the value of the architecture. Through this research, we endeavor to provide an understanding of the Collegiate Gothic style, acknowledging its broader context and considering factors beyond surface aesthetics.

3. Material and Methods

This study centers on Soochow University’s Anderson Hall, a pivotal subject for investigating the Collegiate Gothic style. Our research methodology integrates historical and architectural analysis, examining historical documentation and archival resources.

We draw upon valuable primary sources, including records from the Asia Christian Higher Education Committee at Yale Divinity School (U.S.A.) and historical documents related to architecture and renovations from the Soochow University Archives and Suzhou Municipal Archives. Our literature review spanned the early 20th century to the present, retracing the origin of the American Collegiate Gothic style. This contextual exploration illuminated the symbiotic relationship between the Collegiate Gothic style and Christian educational pursuits. The insights from the literature review guided our analysis of the widespread impact of this architectural style in East Asian contexts, particularly China, Japan, and Korea. Systematically examining available source materials, we aim to explore the origins, influences, and distinctive architectural features of the Collegiate Gothic style within Anderson Hall.

Additionally, we employ on-site surveys, precise measurements, and modeling analysis specifically applied to Soochow University’s Anderson Hall. Our empirical foundation rests on on-site surveys conducted between 2019 and 2023, complemented by architectural drawings and photographic documentation from the same period. To enhance the accuracy and reliability of our data acquisition, we leverage advanced surveying technologies, including 3D scanning (FARO Focus Premium). Modeling software, including Recap (2020), SketchUp (2020), and CAD (2020), processes and integrates survey data. These facilitate the creation of detailed three-dimensional models, enabling an analysis of Collegiate Gothic elements into Anderson Hall’s layout, structural components, and facade.

4. Impact of Missionary-Driven Style

Against the backdrop of colonial history and the evolution of modern education, this research contributes to a nuanced understanding of how missionaries shaped the development of the Collegiate Gothic style within the context of colonial history and educational transformations. It is crucial to emphasize that this exploration does not purport to represent the entire East Asian region but rather provides a contextual linkage.

4.1. Religious Influence on Campus Design in China

The M.E.C.S. launched its mission in late 19th-century China, a period marked by the Qing Dynasty’s increasing exposure to foreign influences following the Opium Wars. Treaties with Western powers during this era, incorporating provisions for religious freedom and missionary activities, provided a strategic opening for the M.E.C.S. and other Christian denominations to establish a foothold in China.

In the 1850s and 1860s, influential American missionaries, such as J. W. Lambuth and W. Allen, arrived in Shanghai and established boarding schools, the Buffington Institute (1871–1899) and Anglo-Chinese College (1881–1911), actively promoting educational initiatives. Its influence gradually extended beyond Shanghai, impacting neighboring areas [

18]. W. R. Lambuth, J.W. Lambuth’s son, appointed an M.E.C.S. missionary in 1877, played a significant role. Upon arriving in Soochow, he rented a private building in Tianci Zhuang (the historical site of Soochow University), and in 1895, the M.E.C.S. founded the KongHang School (the predecessor of Soochow University) (1896–1901) in Soochow. The M.E.C.S. employed multifaceted approaches, including preaching, Bible distribution, evangelistic meetings, and establishing schools and colleges, forming a dual strategy for education and conversion in China’s evolving cultural landscape.

However, before 1900, the prevailing educational system in traditional Chinese society was Confucian education. The appreciation of Confucian values and the adherence to related ethical codes were illuminated by the educational institutions represented by the “Shuyuan” (or the Academy), with its spatial relationship of the memorial temple, the library, and the lecture hall [

19].

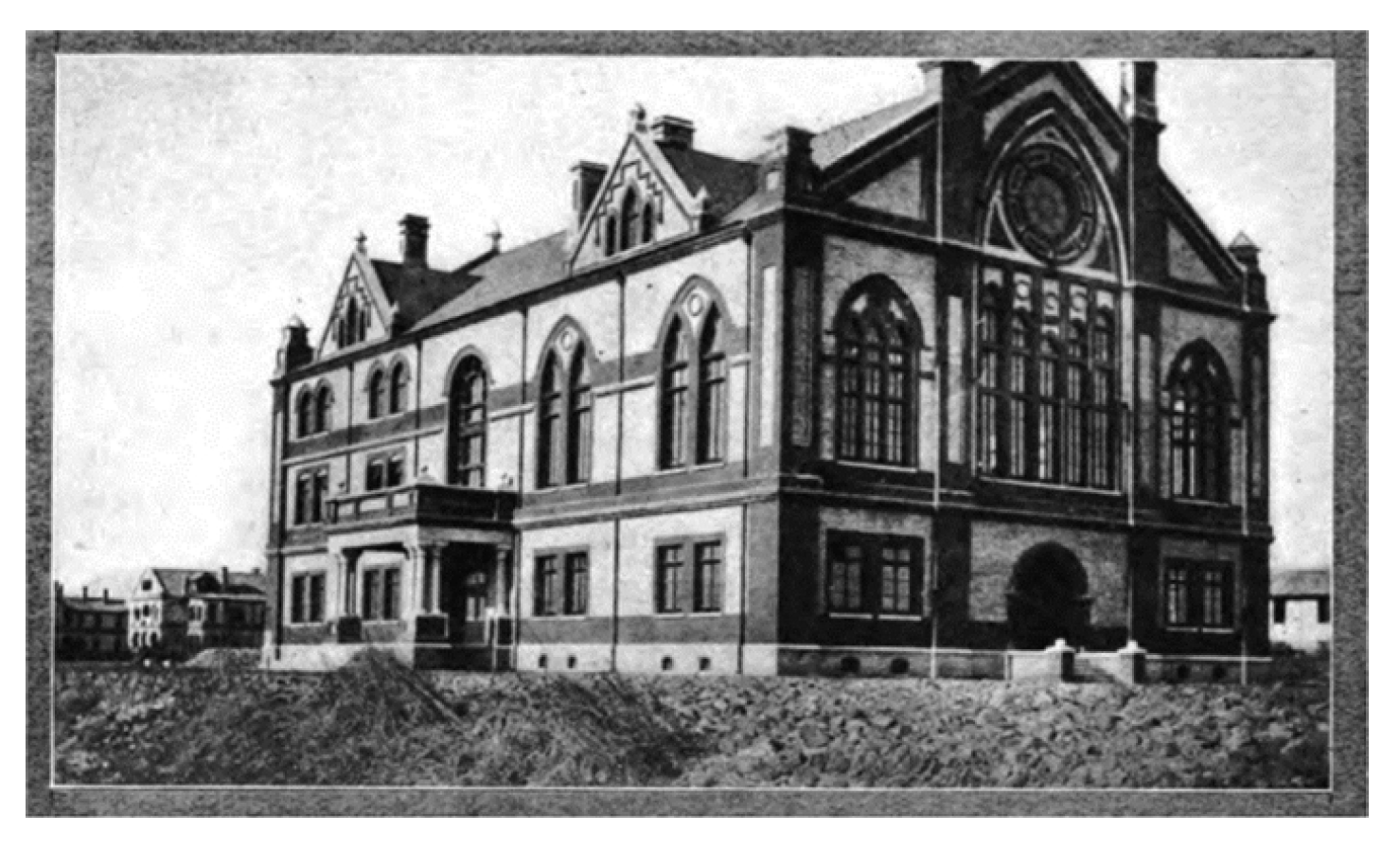

During this era, tensions between the scholar-gentry and missionaries motivated the missionaries to create schools that integrated Chinese traditional architectural styles. For instance, St. John’s University in Shanghai’s Schereschewsky Hall (

Figure 1) combined a distinctive Chinese overhanging roof with a Western-style verandah, opting for integrating Chinese and Western elements to bridge cultural divides [

20].

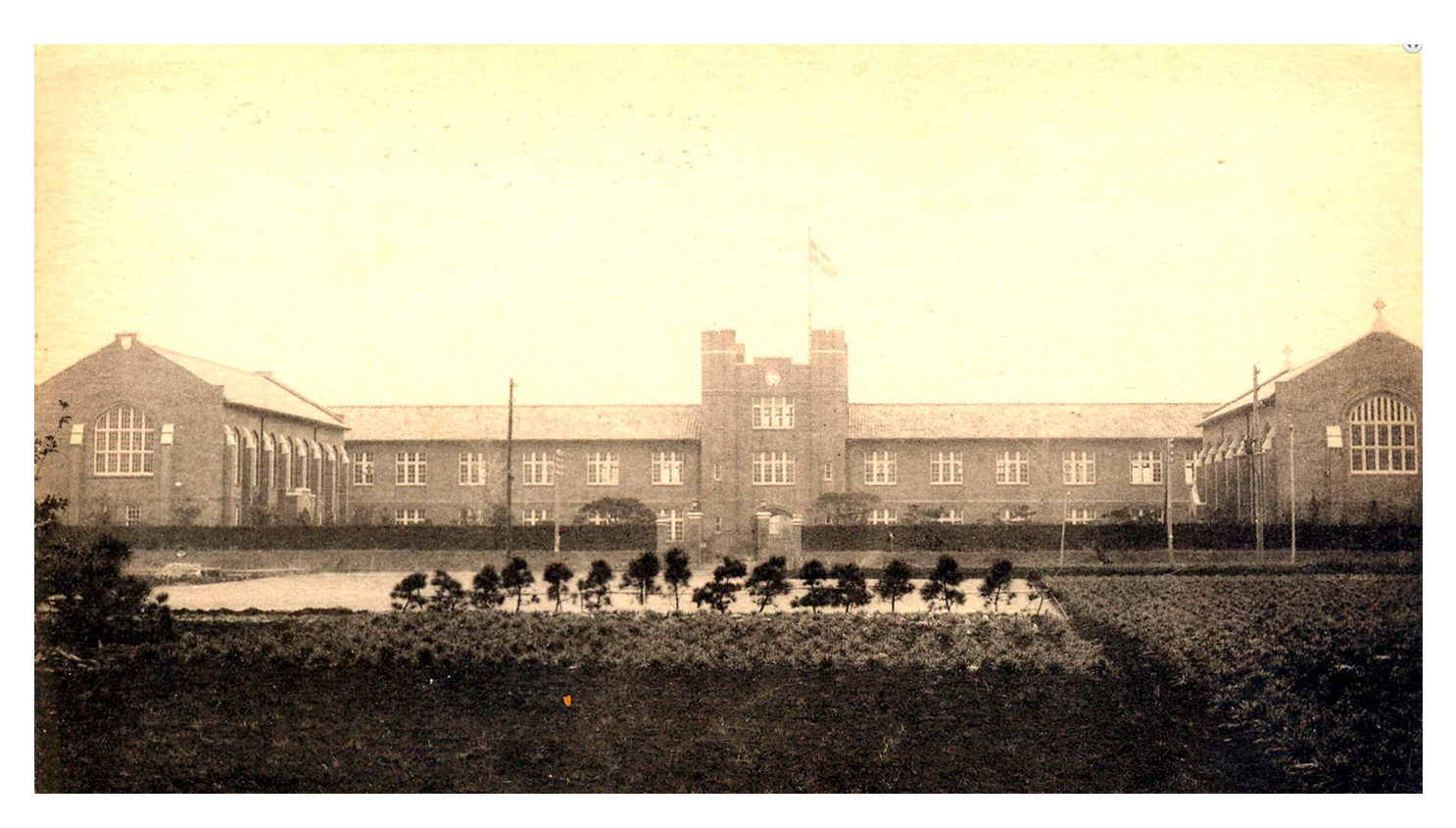

The early 20th-century trend of the Qing government emulating “foreign regulations” may have influenced the Board of Trustees in their choice of campus design. However, this decision was rooted in the Board’s belief in educational equality and their aspiration to establish a university on par with American institutions. Religion played an integral role in shaping campus functions and, by extension, architectural and spatial features. It is worth noting that Soochow University and the University of Shanghai (

Figure 2) exclusively adopted Collegiate Gothic styles for their campus buildings, highlighting a distinctive architectural preference [

10].

In this historical context, architectural styles lacked a defined paradigm, and the evolution of Collegiate Gothic style in modern Chinese university campuses primarily reflected an eclectic approach. Buildings seamlessly integrated classical, Gothic, and Chinese traditional architectural elements [

10]. It underscores the diverse stylistic choices among missionaries of that era.

4.2. Religious Influence on Campus Design in Japan

The reach of the M.E.C.S. mission extended to Japan, notably during the Meiji era (1868–1912), characterized by increased openness and economic development. After the 1873 lift of the Christian ban, missionary activities remained restricted to treaty ports. Until 1899, when granted travel freedom, authorities often prohibited missionaries from openly evangelizing, predominantly confining their activities to treaty ports. Despite the cautious environment for missionaries, they shifted their focus to education, creating lasting cultural ties between Christianity and Japanese higher education [

22]. In 1886, missionaries J. W. Lambuth and W. R. Lambuth, originally from the Chinese mission, arrived in Kobe, Japan. In 1889, W. R. Lambuth established Kwansei Gakuin University in Japan, representing a significant milestone in the M.E.C.S.’s educational achievements [

23].

Before the 1920s, the Collegiate Gothic style had limited adoption in Japanese Christian university buildings. Only the Anglican Church’s Rikkyo University in Tokyo used the Collegiate Gothic style [

24]. The Anglican Christians aimed to establish a permanent university, distinct from traditional wooden structures. The choice of building materials influenced the architectural style. [

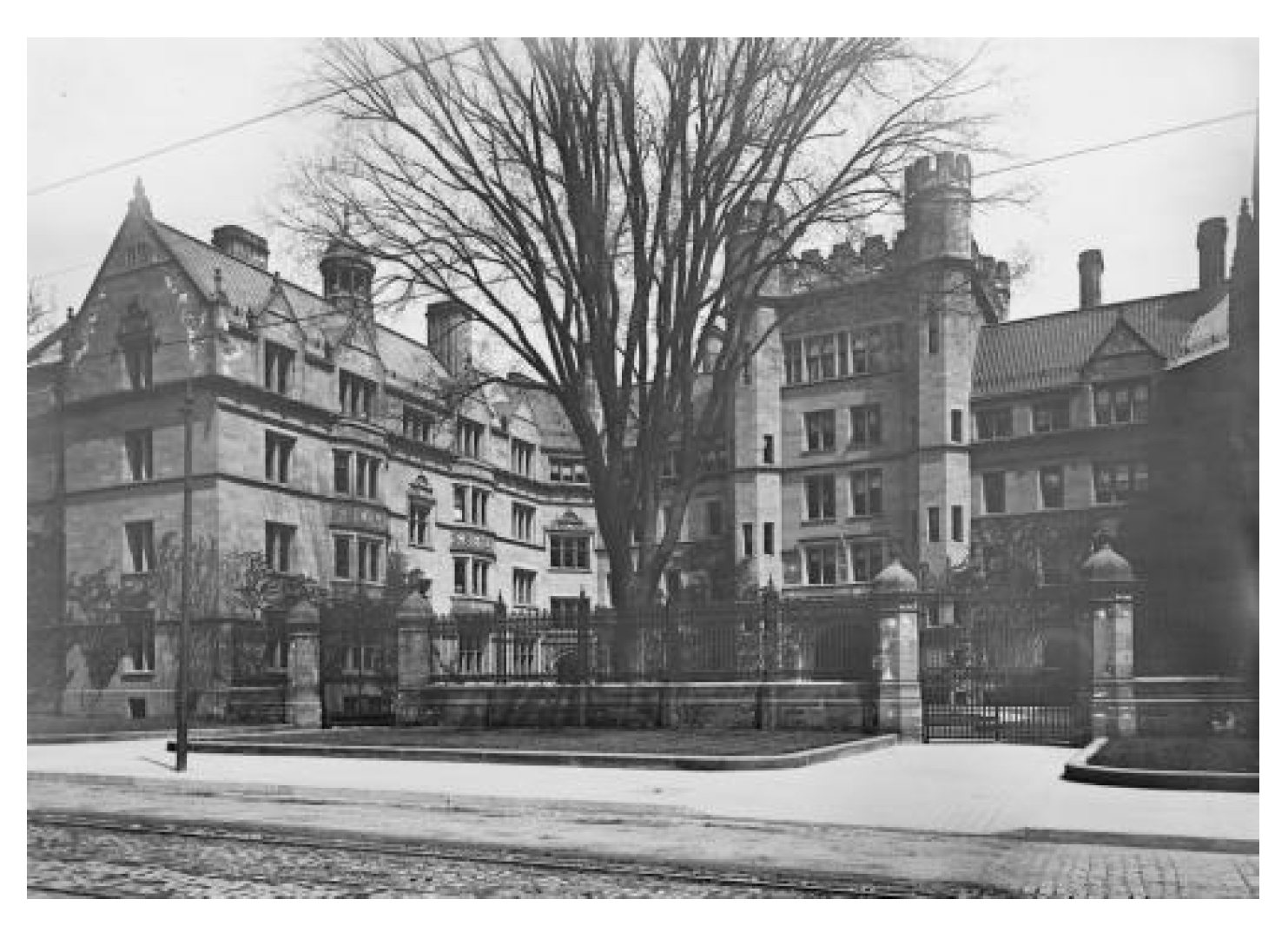

14] Particularly noteworthy is the influence of Murphy & Associates, the architectural design of Rikkyo University’s Main Hall (

Figure 3), which drew significant inspiration from the architect’s alma mater, Yale University Vanderbilt Hall (

Figure 4). This choice highlighted the direct emulation of Collegiate Gothic style by architects.

4.3. Religious Influence on Campus Design in Korea

Similarly, the expansion of the Korean M.E.C.S. was closely related to the M.E.C.S. in China. This connection traces back to 1884 when Yoon Chi-ho sought refuge in Shanghai after the Kabo Reforms in Korea. Yoon Chi-ho received a Christian education at the Anglo-Chinese College (1881–1911). Upon returning to Korea, he invited the M.E.C.S. to engage in missionary work [

27]. In response to Yoon Chi-ho’s invitation, the M.E.C.S. commenced official missionary activities in 1896. Yoon Chi-ho’s diary entries provide evidence of the decision-making process regarding the Chosen Christian College’s architectural style.

“The Board of Directors for the Chosen Christian College met at Dr. Avison’s to discuss the constitution yesterday morning, also had a lengthy discussion about the kind of architecture the College is to have―all Korean or Foreign―decided to have the College portion purely foreign.”

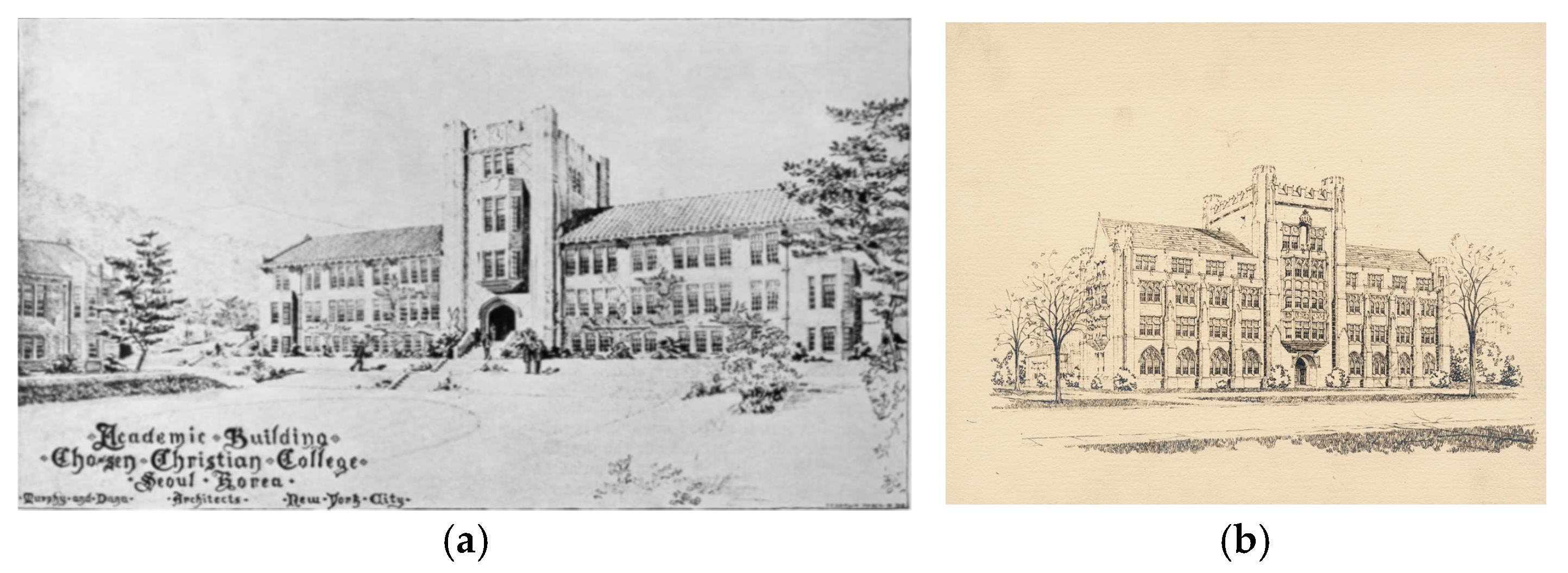

Chosen Christian College’s Underwood Hall in 1924 represents Korea’s earliest example of Collegiate Gothic architecture [

29,

30]. Notably, the architect responsible for the design, H. K. Murphy, has significant relevance. His architectural blueprints (

Figure 5) for the Chosen Christian College closely resembled those of the University of Chicago.

4.4. Result

This section uncovers that missionaries in China, Japan, and Korea incorporated the Collegiate Gothic style into their educational institutions, acting as conduits for introducing Western culture in the Asian region. The Collegiate Gothic style typically features a dignified and intricate exterior, aligning with the missionary’s educational mission. Beyond mere architectural aesthetics, Collegiate Gothic style became intricately interwoven with these countries’ broader cultural, educational, and religious dynamics, leaving a profound and enduring legacy on their built environment.

However, it is essential to recognize that the adoption of this architectural style was not static. For instance, between 1906 and 1924, Henry Murphy’s endeavors at the University of Shanghai, Rikkyo University, and the Chosen Christian College underscored a persistent inclination towards the Collegiate Gothic style. Intriguingly, during his visit to China to plan Yenching University in 1921, Murphy chose an architectural style that amalgamated Chinese and Western elements, reflecting the Chinese Revival style.

The historical context provided in this section is crucial for comprehending the architectural preferences and choices that shaped these missionary-driven educational institutions. These findings set the stage for understanding the factors influencing architectural style choices in Anderson Hall.

5. Factors Influencing Anderson Hall Style Choices

5.1. Funding for Campus Development

Architectural decisions closely tied to religious motivations actively associate the Collegiate Gothic style with respected academic traditions and religious institutions, visually representing the values and practices of the Christian faith. In the early years of Soochow University (1900–1927), the institution relied on funding sources such as educational grants, local community donations, and limited tuition fees. However, external contributions provided the primary financial support for campus development [

18]. In 1909, President Anderson secured

$20,000 in gold from the Lynchburg Court District Church during his visit to the United States [

18] (p. 112). These donations, typically from churches, were driven by specific missions and visions. Therefore, when selecting the architectural style for the campus, the university was inclined to consider the church’s religious beliefs and missions, resulting in Anderson Hall’s architectural style reflecting the church’s mission and vision.

5.2. Missionaries’ Stylistic Preferences

Adopting Collegiate Gothic style was not just an aesthetic choice but an intentional communication of educational values associated with American institutions. The research also discusses the architectural preferences and doctrinal regulations of the M.E.C.S. The book “The Architectural Expression of Methodism: The First Hundred Years”, which focuses on the architectural history of the Wesleyan tradition, provides clues about these aspects. By the 1830s, as the M.E.C.S. and its Sunday schools expanded, they focused more on architectural form. The growth of the denomination and the Gothic Revival movement, which emphasized medieval architectural styles, influenced this shift toward architectural distinctiveness. The M.E.C.S. conservative aesthetic tendencies led to adopting two distinct architectural approaches: in locations where professional architects were available, missionaries preferred Classical or Gothic architectural styles, while in places without professional architects, the architecture was described as indistinct [

32]. It’s also important to acknowledge that style choices were not uniform, indicating a nuanced and complex diversity in architectural preferences.

In 1906, the Education Ministry of the Qing Dynasty promulgated the edict on “Foreign Universities to be Exempt from Filing a Case by Provincial Governors”, which allowed Christian universities not to comply with any guidelines for the facility [

19]. During Soochow University’s construction, particularly in designing Anderson Hall, the influence of the M.E.C.S. and its architectural preferences and doctrinal regulations was evident. Such aligns with the university’s commitment to both aesthetics and religious values.

5.3. Influence of the Vanderbilt Connection

Collegiate Gothic style not only signifies the introduction of Western education but also reflects specific values rooted in the traditions of American universities, manifesting through the physical form of the campus. Nashville, Tennessee, housed the central headquarters of the M.E.C.S. The formal registration of Soochow University in this southern American city in 1901 signifies a profound institutional connection [

18]. However, this connection goes beyond the administrative record, extending to Vanderbilt University, also in Nashville, which holds paramount importance in the narrative [

33]. Vanderbilt University, established in 1873 by Bishop H.N. McTyeire of the M.E.C.S., was a pivotal institution for the training and development of missionaries. Distinguished Vanderbilt alums who assumed leadership positions at Soochow University include Y.J. Allen, a foreign board member, President Cline, and various faculty members, such as Qi Tianxi, R.D. Smart, and S.G. Brinkly [

34].

Owing to their shared educational background and pedagogical principles, the administrators and educators from Vanderbilt University, who joined the ranks of Soochow University, naturally sought to emulate their alma mater. This transference of educational philosophy and campus design served as the fulcrum for the Vanderbilt Connection, significantly impacting the architectural style and overall ambiance of Soochow University’s campus. The architectural influence of the Vanderbilt Connection is evident in Kirkland Hall and Furman Hall at Vanderbilt University and Allen Hall and Anderson Hall at Soochow University (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). These towers feature Collegiate Gothic elements like pointed arches and stained-glass windows. This architectural influence permeates the broader campus aesthetics, thus shaping Soochow University’s distinctive identity and architectural heritage. Furthermore, Collegiate Gothic architecture’s adaptability aligns with urban development’s spatial requirements. The architectural layout of Soochow University, reminiscent of the open campus design with expansive lawns in the United States, suggests a potential suitability for an “organic” plan similar to the early Vanderbilt campus [

19].

5.4. Role of Architects in Design Choices

In 1907, Shanghai witnessed an escalation in construction endeavors, prompting the active involvement of Chinese artisans due to a labor shortage. Under the guidance of foreign architects, these craftsmen played a pivotal role in executing essential brickwork projects [

35]. It marked a significant collaboration between Western architects and Chinese artisans, laying the foundation for understanding the construction practices in Suzhou.

Various architects and artisans from Western and Chinese backgrounds have left their imprint on the architectural landscape of Soochow University. Allen Hall, Soochow University’s main building, was widely attributed to Atkinson & Dallas, a British architectural firm based in Shanghai [

36]. Despite the 1905 “China Educational Directory” praising Allen Hall as “built in the best style”, it’s noteworthy that the popular trend at the time, characterized by blending Collegiate Gothic style and Colonial-style verandas, soon lost its appeal, as indicated by historical accounts. W. B. Nance observed that Colonial-style verandas fell out of favor with Americans [

19].

In tandem with the university’s expansion, the construction of Anderson Hall from 1910 to 1912 perpetuated the tradition of the Collegiate Gothic style. Subsequently, Cline Hall, erected between 1922 and 1924, marked a shift toward a simplified Gothic style. These structures symbolize the architectural evolution at Soochow University, reflecting the influence of architectural trends of their respective periods.

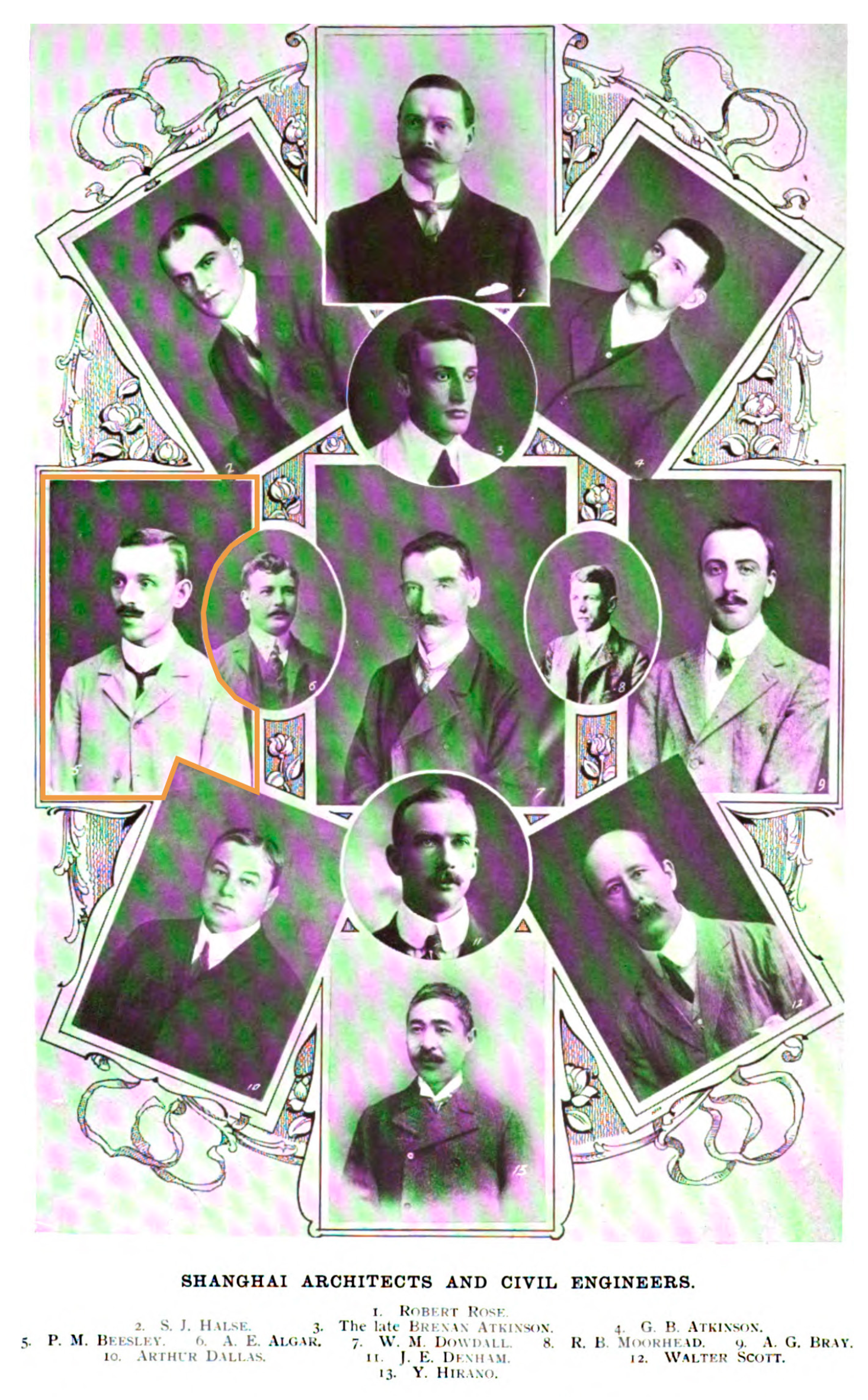

Historical records from the supervisory committee indicate the involvement of a British architect in the design of Anderson Hall, and the architect’s identity remains unconfirmed. Atkinson & Dallas’s construction of Allen Hall and The Laura Haygood Memorial School near Soochow University underscores its close connection. However, there is no recorded information regarding Anderson Hall in available sources. Interestingly, during the same period, an article about the construction of St. John’s Church (

Figure 8), located outside Soochow University (

Figure 9), revealed the involvement of P.M. Beesley, a British designer who had left Atkinson & Dallas by then [

37,

38] (p. 9, p. 261). The article also documented the self-disclosure of the same Chinese craftsman who built St. John’s Church and Anderson Hall [

38]. “…The Chinese constructor played a prominent part in making the edifice possible. He was converted while building Anderson Hall for the Soochow University. This church is largely his thank offering, for he undertook the contract, determined not only not to make a cent out of it, but even to contribute all that he could in addition.” [

38] (pp. 553–554).

Further investigation unveiled that Beesley was a member of the Shanghai Architects Association and the Young Men’s Christian Association (Y.M.C.A.) [

36] (

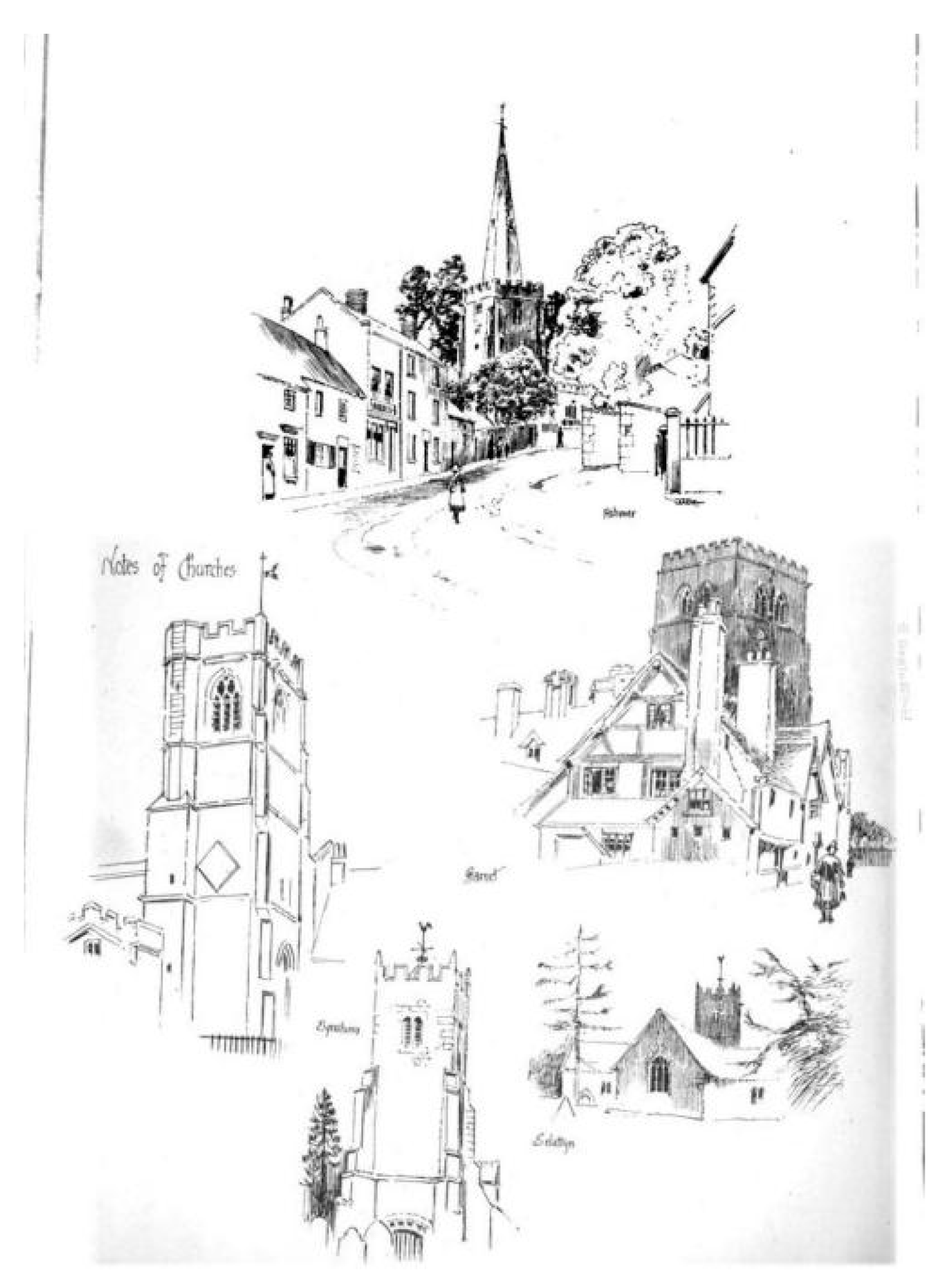

Figure 10). As a member of the British Architectural Society, Beesley had worked on Gothic-style projects in Canada. [

39]. Notably, illustrations in the book “The British Architects” that reference Beesley feature a Tudor-style tower strikingly similar to the one in Anderson Hall [

40] (

Figure 11).

Considering the intricate temporal and geographical exchanges involving British architects, Chinese artisans, and missionaries, there are substantial grounds to speculate that Beesley might have been the architect responsible for designing Anderson Hall. However, it is imperative to acknowledge the dynamic nature of architects’ decisions regarding style. For instance, the Mann Hall at St. John’s University, built in 1909 by Percy Montagu Beesley, epitomizes a blend of Chinese and Western styles. This choice exemplifies a spectrum of approaches to cultural adaptation and resistance, where some institutions opted for an eclectic fusion of architectural elements. This diversity underscores the dynamic nature of missionary strategies and architects’ decisions in navigating cultural nuances.

The 1915 China Continuation Committee Meeting records shed light on the architect selection process of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (M.E.C.S.). The meeting acknowledged the unlikelihood of establishing a dedicated architectural bureau for their missionary work. Instead, the committee concluded that a more practical solution would be to ensure the presence of reputable architectural firms with a strong interest in mission work by establishing branch offices in Shanghai [

41]. This fact aligns with the M.E.C.S.’s preference for architects with a deep commitment to missionary work and elevated status.

5.5. Result

In summary, the selection of the Collegiate Gothic style for Anderson Hall reflects a complex interplay of factors in a diverse societal context. Church funding aimed to convey values, with the Collegiate Gothic style interpreting Christian ideals on campus. As Soochow University’s second building, Anderson Hall continues the Collegiate Gothic style of Allen Hall. However, influenced by the preferences of American missionaries, it deviates from Allen Hall’s Colonial-style veranda. The collaboration of foreign architects and Chinese artisans signals the transformation of traditional craftsmanship in modern China. Foreign architects provided blueprints, and Chinese artisans became builders. The dynamic choices of foreign architects regarding campus architectural styles in different periods reflect the diversity of stylistic preferences.

As we delve into the subsequent discussion on the Collegiate Gothic style in Anderson Hall, it becomes evident that this architectural style served as a vehicle for expressing religious and educational values within the university landscape. The evolving dynamics of architectural decisions, cultural adaptations, and collaborations between foreign architects and local artisans underscore the complexity of this historical narrative, shedding light on the nuanced processes that shaped Anderson Hall and its significance within the broader context of Soochow University’s architectural evolution.

6. Collegiate Gothic Style Influence on Anderson Hall

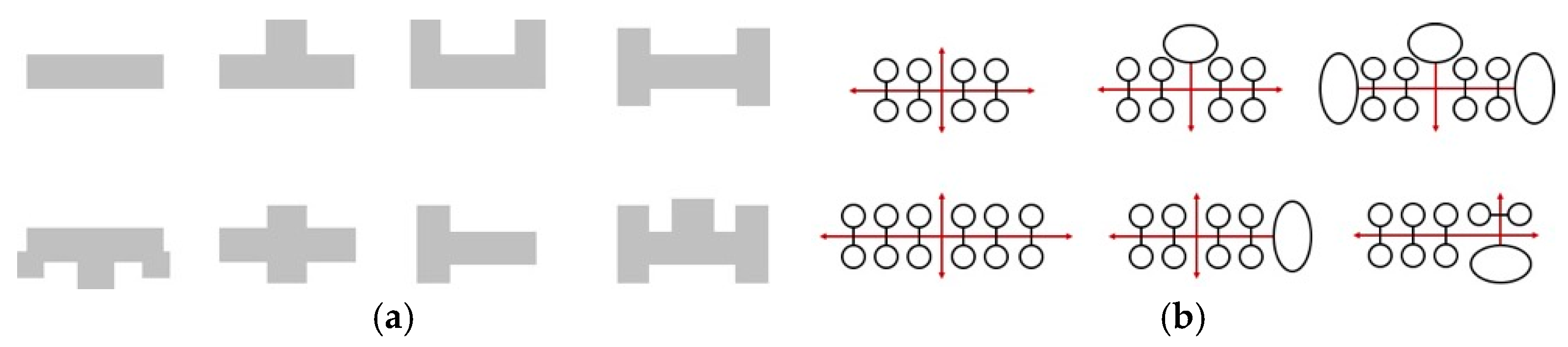

Soochow University pioneered educational architecture in China, notably by advancing the innovative I-shape basic spatial prototype (

Figure 12). The architectural design of Anderson Hall prominently reflects this visionary approach.

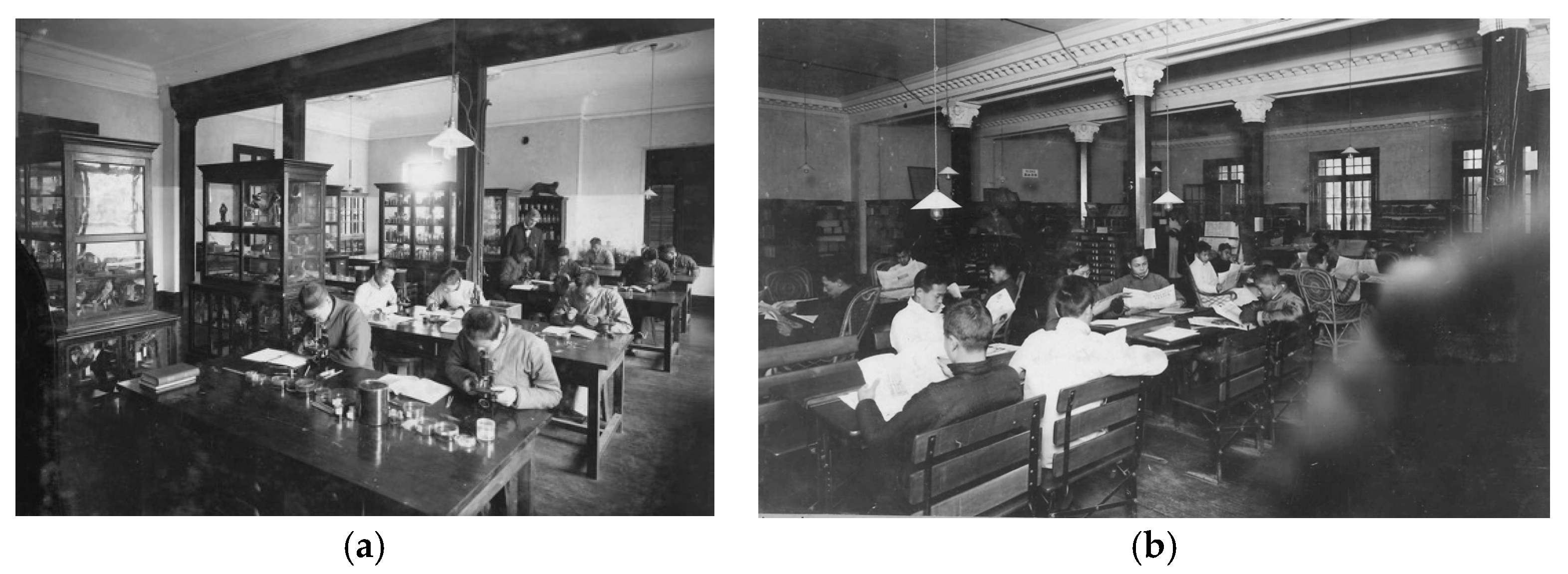

After the completion of Anderson Hall, the library gradually expanded into the northern section of the building; between 1921 and 1924, the library’s growth extended to encompass the entire second floor of Anderson Hall, resulting in a separation of spaces for reading and book storage (

Figure 13). In the case of Anderson Hall, this meant that its architectural type, functions, and style became tangible expressions of this innovative pedagogy. Additionally, special functions within Anderson Hall, such as administrative offices, study areas, and literary societies, contributed to the creation of distinctive spatial forms both internally and externally.

6.1. Architectural Plan Characteristics

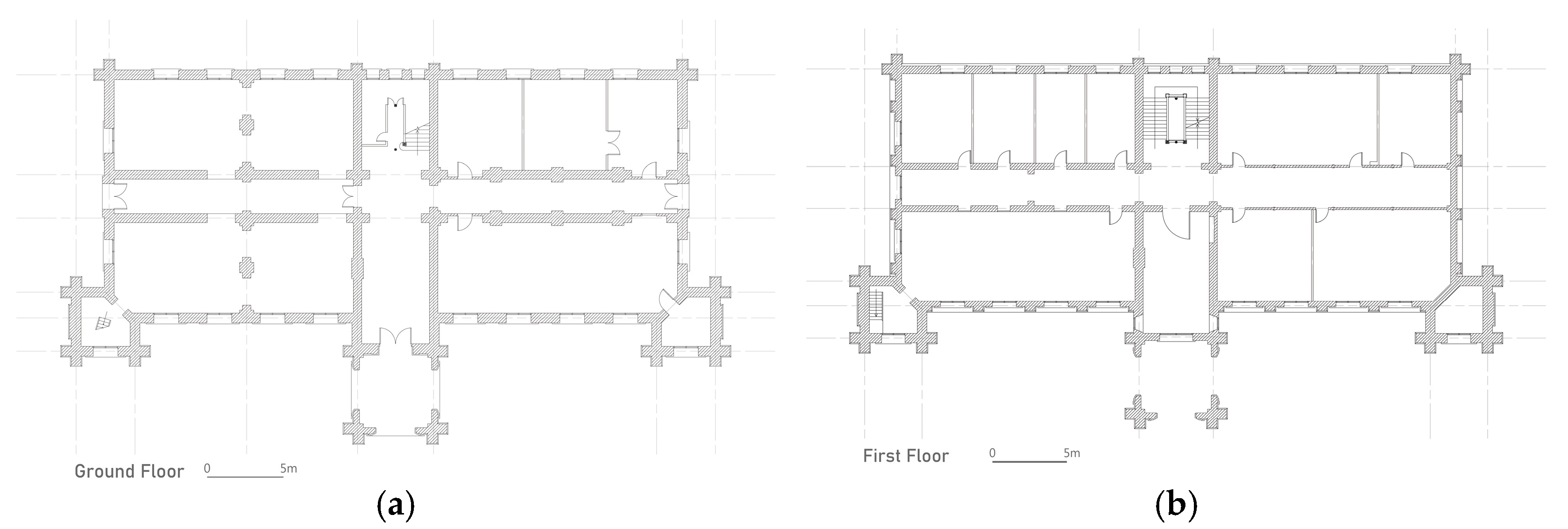

With a centrally positioned entrance symmetrically positioned along the longitudinal façade, Anderson Hall achieves an aesthetically balanced external appearance. The main entrance thoughtfully aligns with the central staircase, creating a harmonious and functional focal point.

Of particular significance is the internal arrangement of Anderson Hall. Each floor plan is segmented by intersecting corridors, establishing a continuous circulation system within the building (

Figure 14). These corridors serve a dual purpose: organizational hubs and circulation pathways. They occupy a substantial portion of each floor’s total area, typically 20–30%, optimizing functional space and enhancing natural light and ventilation [

19].

This architectural ingenuity within Anderson Hall exemplifies its innovative design. As the second building in Soochow University’s development, it closely aligns with its evolving pedagogical philosophies and spatial requirements. It has established itself as a central and pivotal structure in the institution’s architectural heritage by adopting a relatively purer Collegiate Gothic style.

6.2. Structural Features

The unique structural features and innovative use of building materials distinguish Anderson Hall. It primarily incorporates a blend of red and blue bricks, departing from the traditional use of blue bricks. In late Qing Shanghai, the establishment of mechanized brick and tile factories marked the onset of the modern era of red brick production [

42]. The collaboration of brick columns and arches is pivotal in sharing the load-bearing functions of the walls, resulting in a distinct cross-shaped structure at the building’s corners.

Furthermore, the dimensions of Anderson Hall’s red bricks closely resembled the prevalent measurements in Shanghai, which were 254 × 127 × 44 mm, deviating from the typical size of blue bricks at 254 × 127 × 50 mm (

Figure 15). Given the close cultural exchanges and railway connections between Suzhou and Shanghai [

43], one can plausibly infer that Shanghai transported the red bricks used in Anderson Hall to Suzhou [

19]. This transportation of materials reflects the process of localizing Western-style architectural materials in regions like Shanghai and Suzhou. Moreover, the application of English-style masonry distinguishes the structure of Anderson Hall, underscoring the profound influence of Western architectural culture on Suzhou’s building practices.

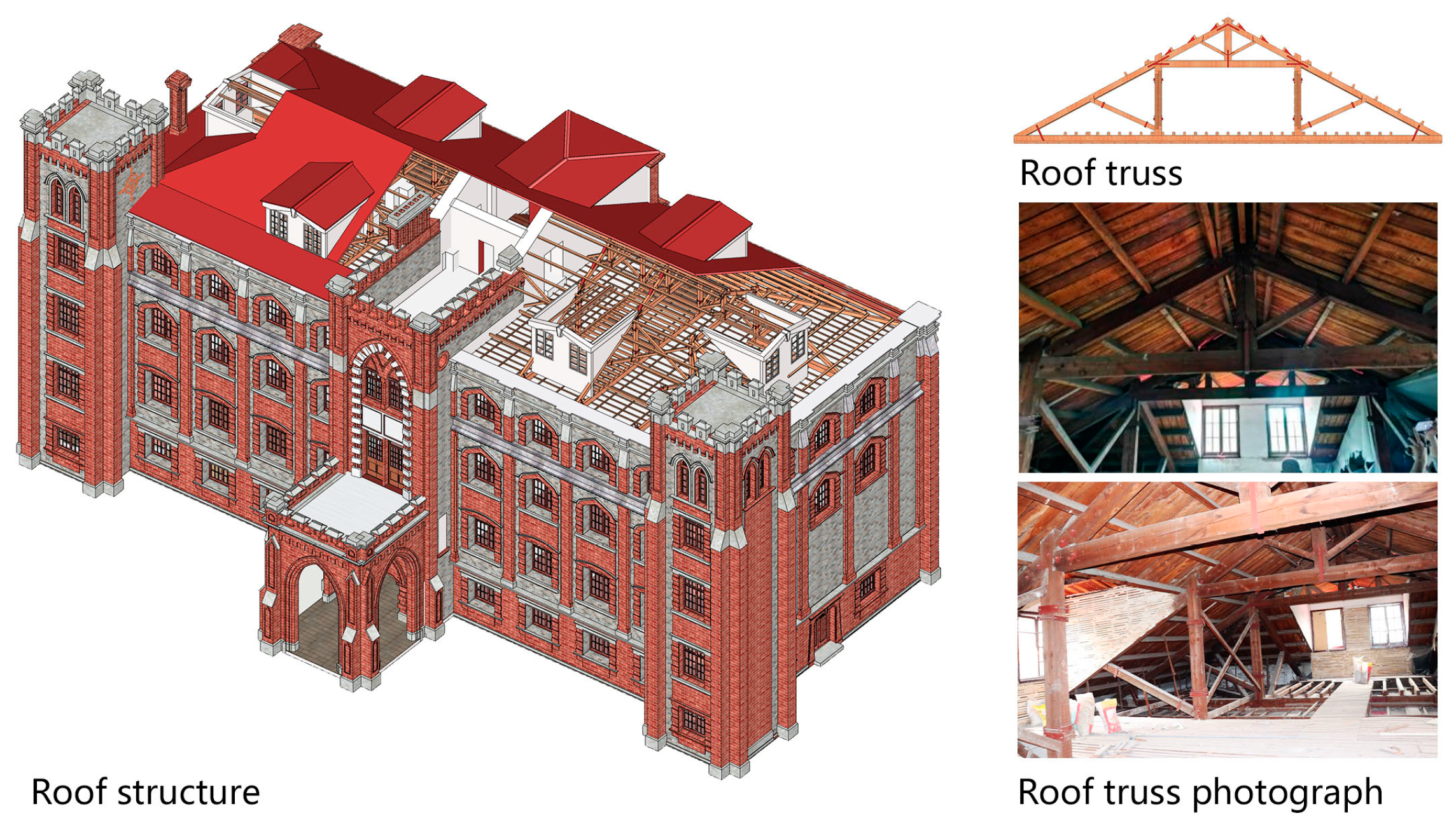

Adopting a Western-style roof structure in Anderson Hall provides the building with enhanced architectural freedom and spatial design flexibility, emphasizing the assimilation of Western architectural technology and construction (

Figure 16).

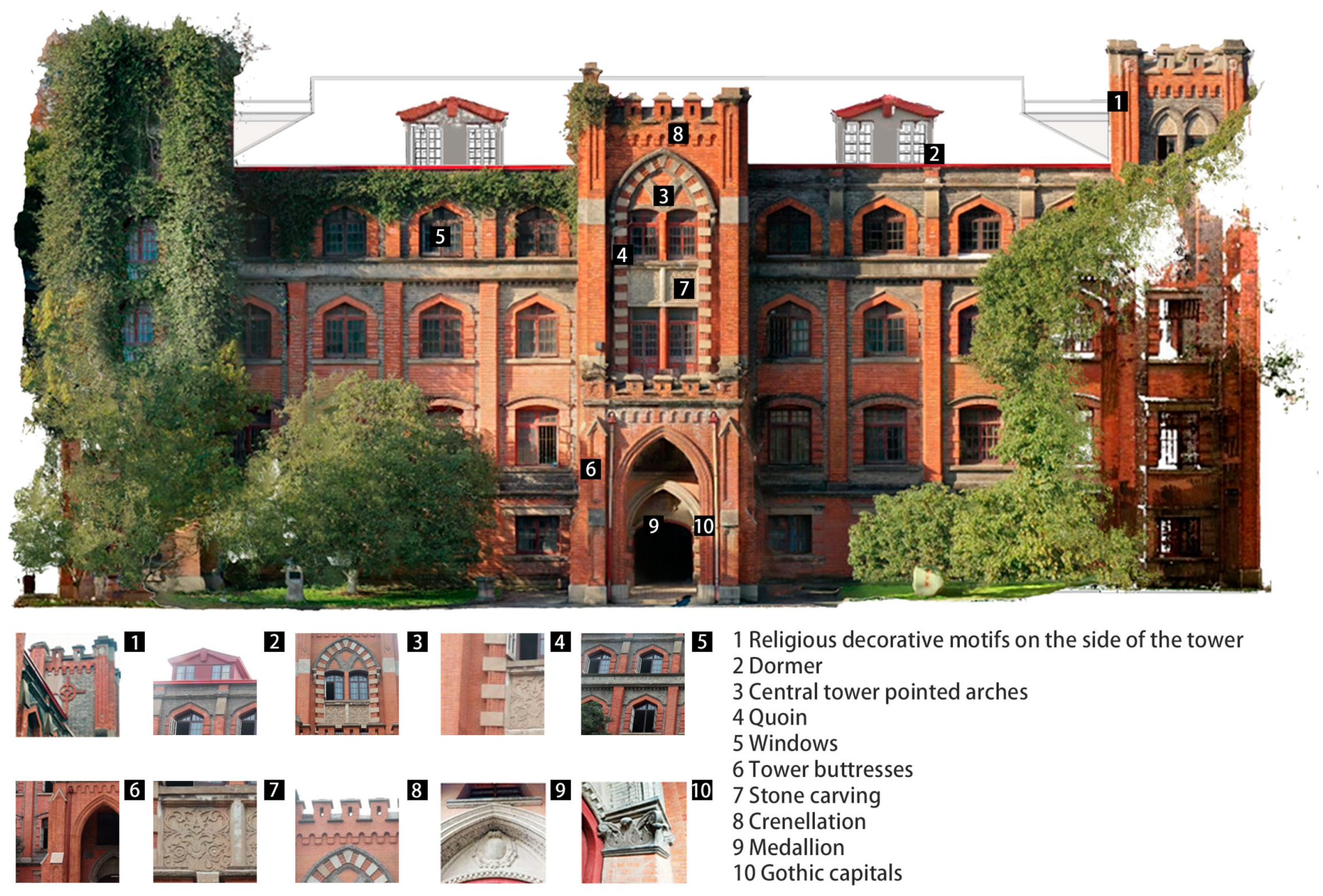

6.3. Facade Characteristics

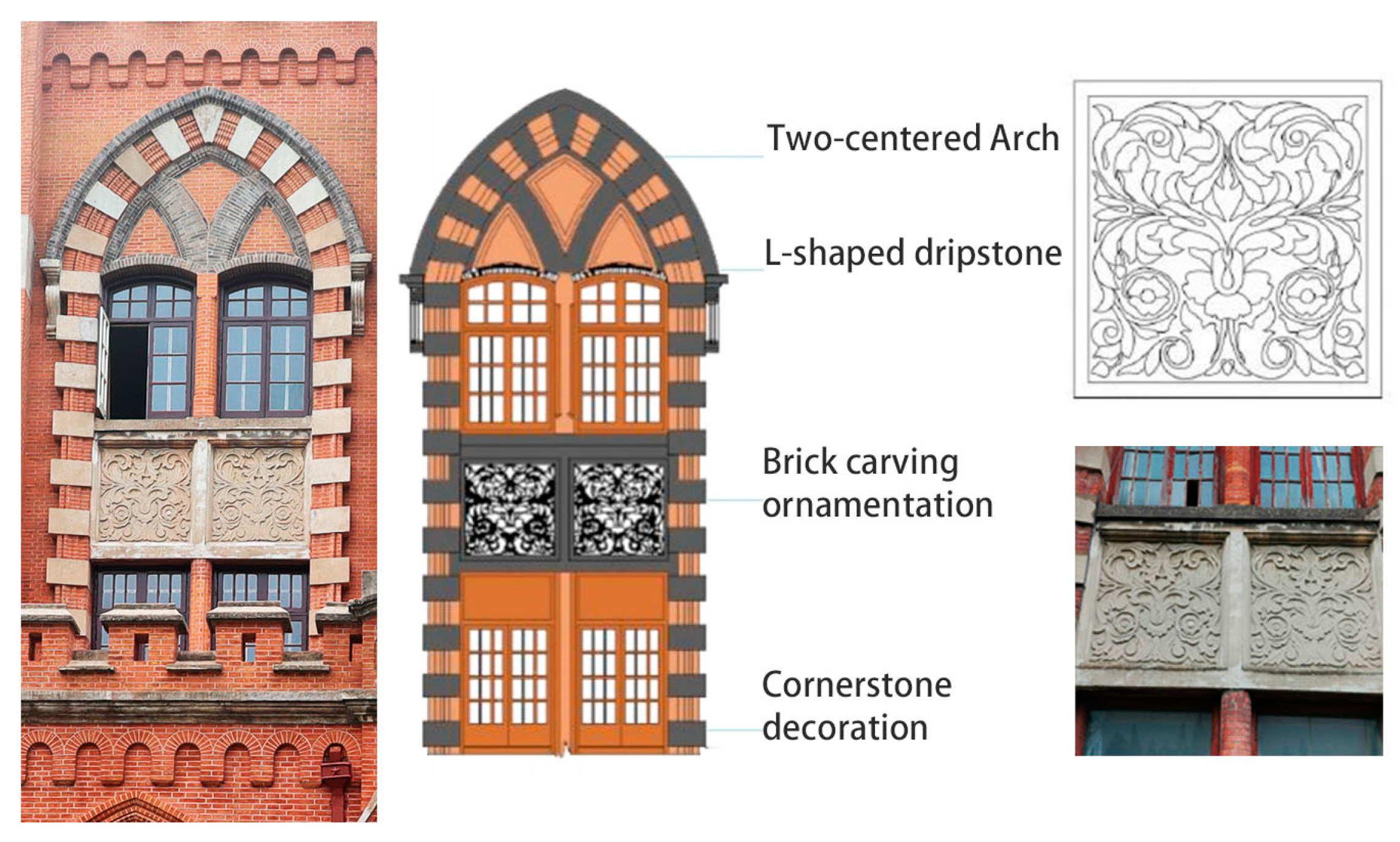

The eastern façade of Anderson Hall proudly exhibits a Collegiate Gothic architectural feature. Three towering structures, adorned with crenelated parapets, evoke the imagery of medieval European fortifications, infusing the tower with a palpable sense of grandeur. The central entrance commands immediate attention, serving as the focal point of the facade. It boasts a majestic porch featuring three twin-centered pointed arches, each towering to an impressive height of approximately 6 m and spanning a breadth of 2.5 m. Artisans adorned these arches with intricate stone carvings and intricate dentil molding, a testament to the exceptional craftsmanship invested in their creation (

Figure 17).

A commanding equilateral particularly distinguishes the central entryway pointed arch (

Figure 18). Nested within this imposing arch are two smaller pointed arches, contributing to the doorway’s overall architectural intricacy. The pointed arch windows on the summits of the towers flanking the building’s facade correspond with the tapered arch design of the central tower. The vertical progression of window designs on each level imparts a sense of ascension and visual grandeur characteristic of Gothic architecture, ultimately contributing to the overall harmony and unity of the facade.

Of profound significance, the northern and western facades of the tower structures prominently feature the symbolism of the Christian faith, displaying the “Celtic cross”. These faith-inspired elements underscore the deep spiritual and cultural connections interwoven with the architectural features of Anderson Hall (

Figure 19).

6.4. Result

As a cohesive entity, the influence of the Collegiate Gothic style transcends superficial facade expressions, leaving an indelible mark on the floor plan and structural composition of Anderson Hall. The adoption of the I-shape scheme plan by Anderson Hall is an innovative educational spatial model, symbolizing the assimilation of American university teaching principles during the founding of the Christian institution.

The infusion of Collegiate Gothic aesthetics introduces avant-garde materials and structural technologies, ensuring enhanced durability compared with conventional Chinese wooden structures, and seamlessly aligns with Christian values. Particularly noteworthy is the manifestation of Collegiate Gothic elements on the facade, including towers, which intensify the overall religious ambiance.

The transformative evolution in harmony with American educational ideals is represented by introducing a singular floor plan, incorporating sophisticated materials and structural techniques, and embodying Collegiate Gothic elements within Anderson Hall. This amalgamation significantly reinforces enduring Christian values within the architectural framework of Anderson Hall.

7. Discussion

The Collegiate Gothic style, more than a mere architectural aesthetic, symbolizes academic tradition and spirit, transcending the realm of architectural progress. Often, it finds itself at odds with the functional demands of educational buildings due to its tendency towards pure formalism, resulting in a separation of structure, function, and form. Consequently, with the rise of modernist architecture, Collegiate Gothic style has gradually receded from the historical stage. In this context, with its pronounced religious undertones, the Collegiate Gothic style emerges as a distinctive architectural form on campuses, reflecting the coexistence and integration of diverse cultures in a specific historical backdrop.

Centered on the Collegiate Gothic architectural style, this study aims to trace the dissemination background and origins. Its purpose is to draw attention within the architectural history community to the unique artistic value of this Westernized campus and simultaneously shed light on the roles played by political upheavals, missionary educational endeavors, architectural design intentions, and Chinese artisans in the transformative process of modern Chinese architecture.

This study explores the Collegiate Gothic style by tracing its origins to medieval universities, with Oxford and Cambridge serving as early prototypes in Britain. By the late 19th century, this style migrated to the United States, where it evolved and gained popularity, featuring characteristics like towers, pointed arches, battlements, and bay windows. The influence of Western colonization introduced political and social challenges to China, prompting American missionaries to establish Christian universities. Adopting the Collegiate Gothic style in these institutions symbolizes a material manifestation of their mission, aligning with prior research on its connection to Christian evangelism and educational orthodoxy objectives.

Our study integrates a cross-cultural perspective, tracing the paths of missionaries as a guiding thread. It intricately interweaves with the missionary routes of the M.E.C.S. in East Asia, exploring how the educational initiatives of missionaries have intricately shaped the underlying rationale and logic behind the adoption of this particular architectural style.

In contrast to prior research exploring Chinese Revival styles and Collegiate Gothic style in Christian university architecture, our study explores why Anderson Hall at Soochow University chose the Collegiate Gothic style. This stylistic choice aligns seamlessly with the church’s funding and the prevailing Christian atmosphere in church-affiliated universities. The key figures in establishing Soochow University had close ties to Vanderbilt University, establishing a connection between Vanderbilt University and Soochow University’s architectural and layout choices. Although direct evidence regarding the architects and builders of Anderson Hall is lacking, examining the collaborative relationships between Western architects and Chinese artisans, the temporal and geographical proximity of St. John’s Church and Anderson Hall, and the departure of Beesley from the Atkinson & Dallas, suggest that Beesley may have been the architect for Anderson Hall. This perspective distinguishes our research from previous studies, offering an understanding of the contextual and collaborative factors influencing the adoption of Collegiate Gothic architecture at Soochow University.

Moreover, this research transcends an examination of the façade elements within the Collegiate Gothic style of Anderson Hall. It explores the floor plan and structural elements. It is essential to underscore this architectural style’s pervasive influence on the visual aesthetics and the functional and structural aspects of the building. Through this research, we aim to enhance scholars’ understanding, providing an enriched vantage point for discerning the role and impact of Collegiate Gothic style in Chinese Christian universities.

8. Conclusions

As a fundamental component of Soochow University, Anderson Hall embodies the lasting influence of educational institutions on cultural identity, playing a pivotal role in nurturing talents. As a manifestation of Collegiate Gothic architecture in modern Christian universities, Anderson Hall was inspired by the symbolic use of red bricks in British universities and influenced by the educational philosophies, religious characteristics, and values of American universities and missionaries. Financed by American missionaries and designed by British architects, its construction involved a collaborative effort with Chinese artisans. It reflects the cultural exchange between East and West, contributing to the diversity of Chinese Christian university architecture. Anderson Hall’s construction also contributed to modern Chinese architectural technology, using blue and red bricks and British bricklaying techniques.

Over its century-long existence, Anderson Hall has experienced fires, damage, and subsequent restoration. This research on its architectural style serves as a valuable reference for the preservation and restoration endeavors of Anderson Hall and has included crucial aspects of China’s modern history, from the spread of Christianity to colonial influences. Anderson Hall holds significant historical, cultural, artistic, and scientific value, making it a multifaceted symbol of China’s modern history and architectural heritage. It intertwines with narratives of cultural exchange, institutional evolution, and the enduring impact of Chinese Christian university architecture throughout history. In 2013, the historical site of Soochow University was designated as an essential heritage site under state protection, categorized under “important historical sites and representative buildings of modern times”. No longer confined to its religious connotations, it transformed into a representative of national cultural preservation, encapsulating fragments of China’s modern history. This dynamic interpretation mirrors shifts in historical contexts and serves as a crucial testament to how the perception of the building’s role has evolved across different historical epochs.

This study, achieved through an in-depth exploration of the intricate connections between architectural styles, cultural influences, and the enduring legacy of missionary activities, lays the groundwork for future scholars. It encompasses a microcosmic perspective within this broader historical narrative, providing profound insights into the challenges and historical value assessments required to preserve such Christian university heritage. This study also suggests avenues for future research to delve deeper into the nuanced impacts on architectural development, considering both positive and negative aspects. The changes in Suzhou’s urban layout in modern times, closely tied to campus planning and building construction, provide an intriguing avenue for exploration. Additionally, investigating the lasting effects of colonial influences on Christian university architecture and urban development may be a productive area for further exploration. While recognizing the undeniable negative impacts of colonialism on modern Chinese history, it is crucial to address concerns about colonial influences, including those of missionaries. In response, it is essential to acknowledge that architectural development is inherently complex, drawing from various historical influences, both positive and negative. This enduring legacy serves as a testament to the nuanced nature of architectural development, where diverse historical influences converge to shape a distinctive and meaningful architectural identity.