Abstract

Platinum group metals (PGMs)—comprising platinum (Pt), palladium (Pd), rhodium (Rh), iridium (Ir), ruthenium (Ru), and osmium (Os)—are indispensable strategic materials for key industries, including automotive manufacturing, petrochemical engineering, and the new energy sector. Given the uneven global distribution of primary PGM reserves and the widening supply–demand gap, recovering PGMs from secondary sources—primarily metallurgical by-products and spent catalysts—has become a strategic priority. synergistic smelting, leveraging “multi-feedstock complementarity” and “multi-technology coupling,” offers an efficient approach to overcoming challenges associated with secondary resources, such as low grades, complex matrices, and refractory separation. This paper systematically reviews the technological evolution of synergistic smelting for PGMs recovery, focusing on three aspects: the characteristics and processing bottlenecks of PGMs-bearing secondary resources, the development trajectory of traditional metallurgical technologies, and innovative breakthroughs in microwave-assisted synergistic smelting. A comparative analysis between traditional and microwave-based technologies is conducted across four dimensions: resource adaptability, technical performance, environmental sustainability, and industrial maturity. Finally, the core challenges currently confronting microwave-assisted synergistic smelting and future directions for industrial demonstration are elaborated on. This study serves as a comprehensive reference for the efficient and sustainable recovery of PGMs, with significant implications for the circular economy and strategic resource security.

1. Introduction

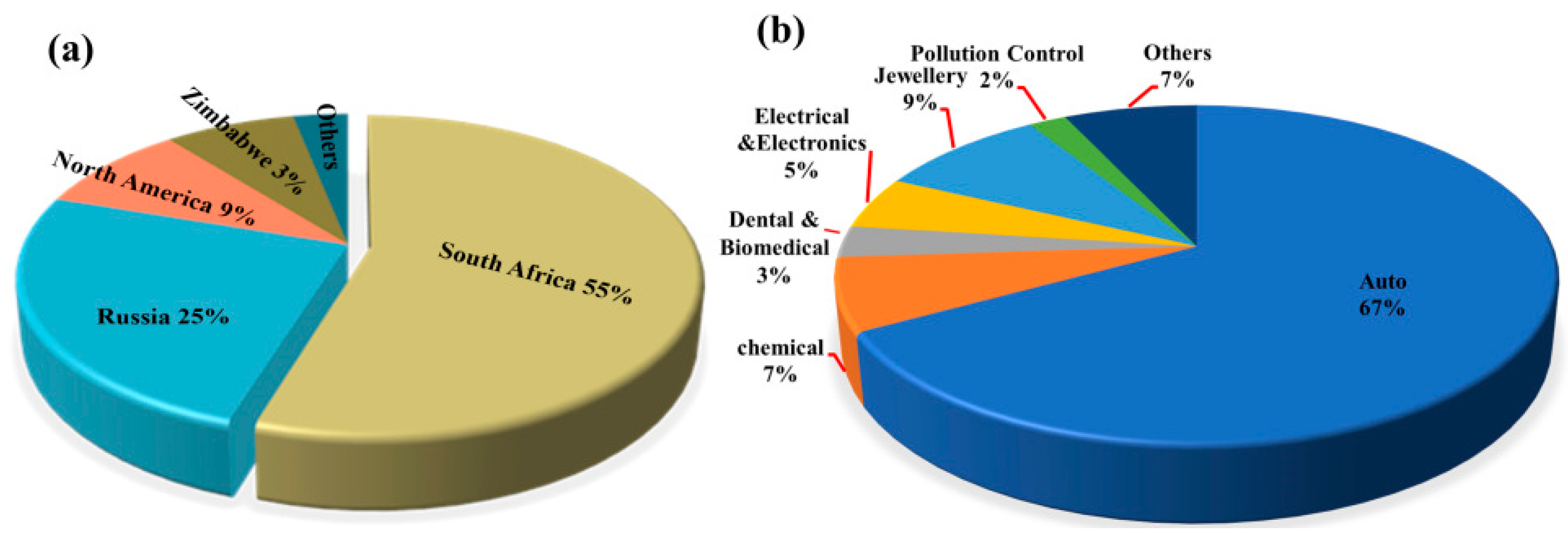

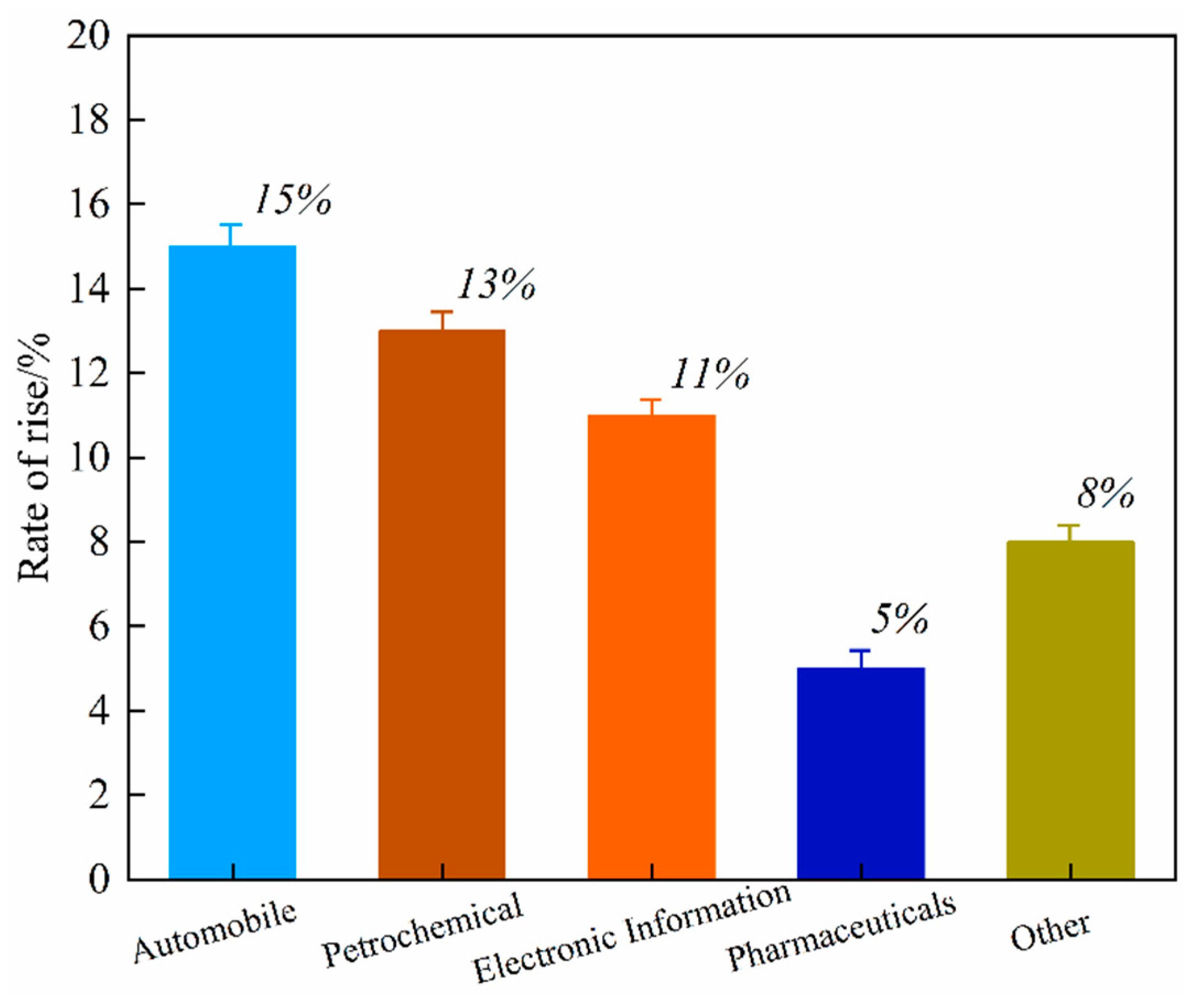

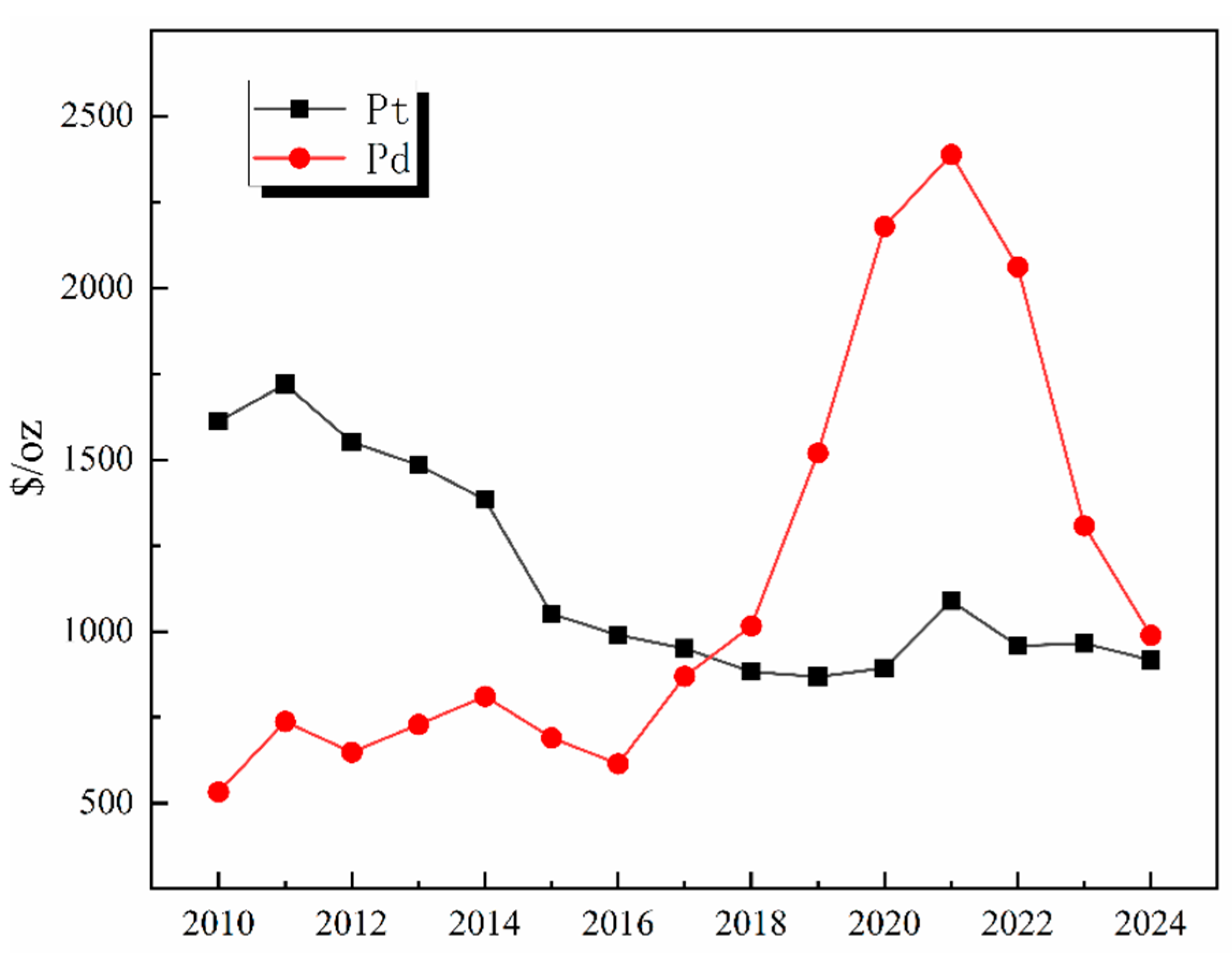

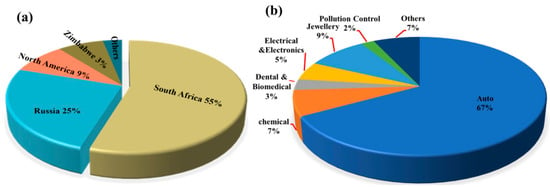

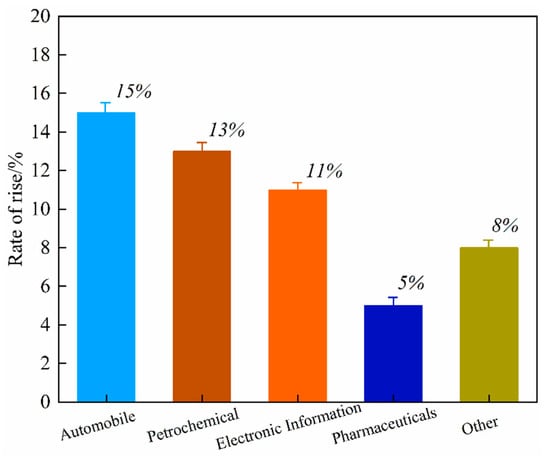

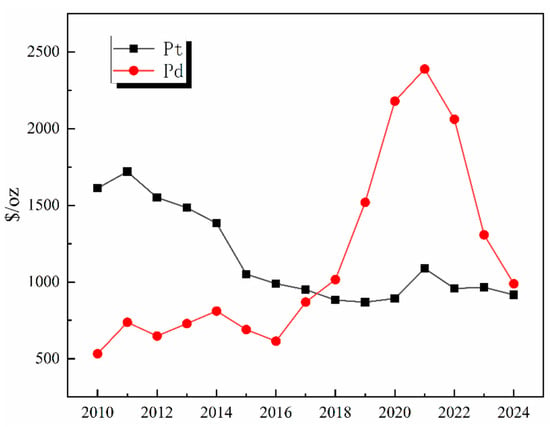

Global primary PGM resources are increasingly depleted, with approximately 70% of the reserves concentrated in countries such as South Africa and Russia. The distribution of global PGM reserves is shown in Figure 1. According to the 2024 report released by Anglo American, a South Africa-rooted global mining giant, the ore grade of its platinum mines has dropped from 4.5 g per ton in 2010 to 2.8 g per ton in 2024, while the mining costs have surged by 60% [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. As the world’s largest consumer of PGMs, China has relatively low primary reserves and an extremely high degree of external dependence. Demand for PGMs remains robust globally in the context of green energy transition and industrial sectors, with an estimated annual growth rate maintaining a high level of 10–15%, particularly in key industries such as new energy vehicles, petrochemicals, and electronic information [9]. The growth rate of global demand for PGMs by industry from 2020 to 2024 is shown in Figure 2. This growth is particularly prominent in the petrochemical sector. In 2024, the massive commissioning of global catalytic reforming units—with the estimated new capacity reaching around 12 million tons per year—has directly driven an annual increase of approximately 15 tons in the demand for palladium [10]. Currently, the global recycling level of PGMs is far from meeting the consumption scale of primary mineral resources, with the recovery rate remaining at a low level for a long time. The supply capacity of secondary resources is limited, which has exacerbated the structural shortage in the market. Among various secondary resources, spent automotive exhaust catalysts are the most important contributors in the recycling value chain, forming the absolute source of recycled PGMs. Driven by this supply–demand fundamental, the international spot prices and domestic recycling prices of metals such as platinum and palladium have both shown characteristics of operating at high levels with significant fluctuations in recent years [11,12,13]. The trend of international spot prices of Pt/Pd from 2010 to 2024 is shown in Figure 3. This profoundly reflects their irreplaceable scarcity and high economic value in key application fields.

Figure 1.

(a) Global distribution of PGMs reserves; (b) application of PGMs.

Figure 2.

Growth rate of global demand for PGMs by industry (2020–2024).

Figure 3.

Trend of international spot prices of Pt/Pd from 2010 to 2024.

Against the backdrop of increasingly tight primary mineral resources, secondary resources represented by metallurgical by-products (such as copper anode slime, stainless steel pickling sludge, and precious metal refining slag) and various spent catalysts (such as automotive three-way catalysts and petrochemical hydrogenation catalysts) have been widely recognized as the most valuable strategic resource reserve, due to their high enrichment of PGMs and large potential reserves [14,15]. Compared with low-grade primary ores, the grade of PGMs in these secondary resources is usually several orders of magnitude higher, demonstrating extremely high recycling economics. For instance, the contents of metals such as Pt and Re in spent petrochemical catalysts are quite considerable. Meanwhile, end-of-life automotive exhaust catalysts have become the most important urban mineral source of metals like Pt, Pd, and Rh in the circular economy. Among metallurgical by-products, copper anode slime is particularly significant—it is not only the main raw material for Ag and Au recovery but also contains a notable grade of PGMs, serving as a stable and reliable secondary supply source for these rare and precious metals [16,17].

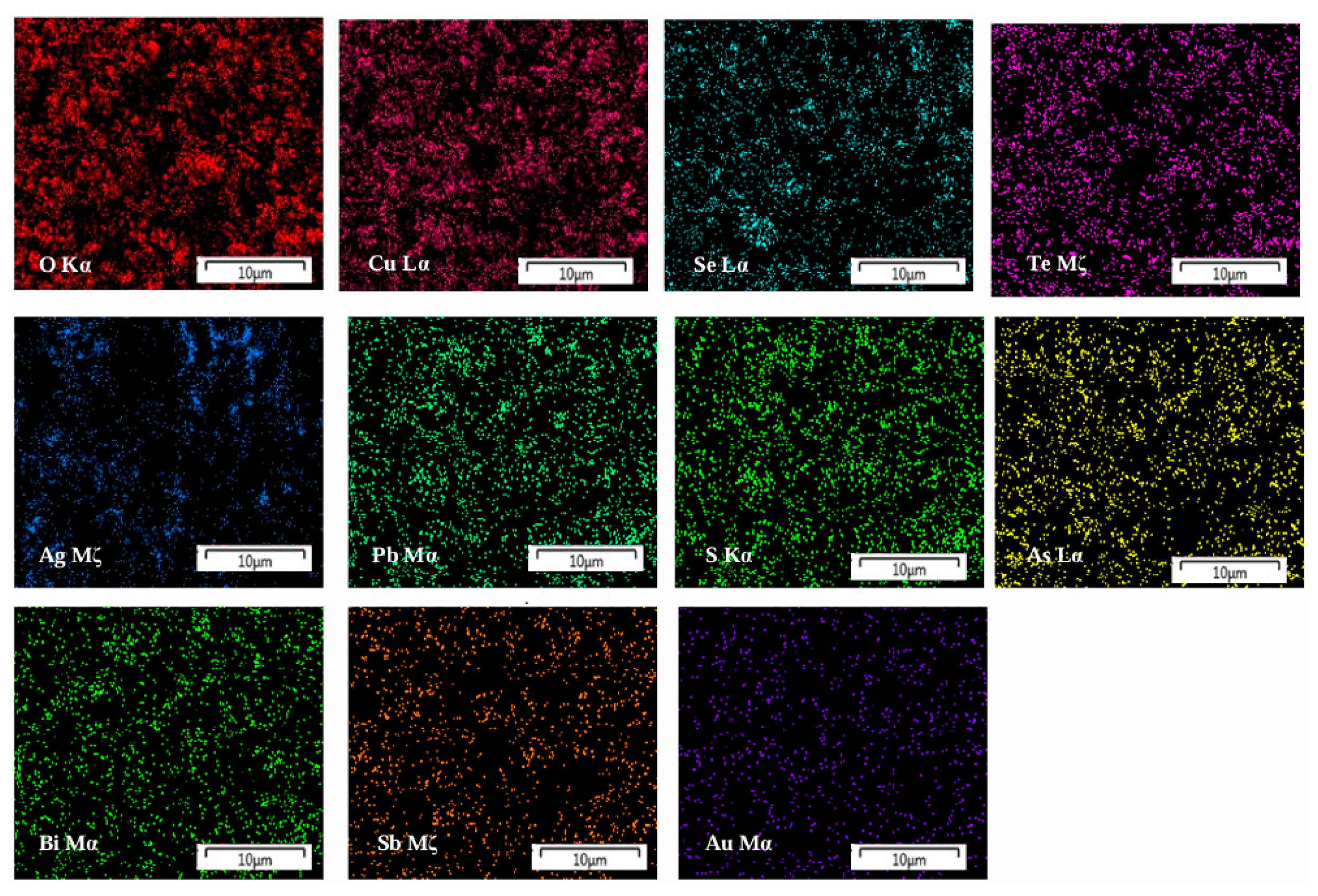

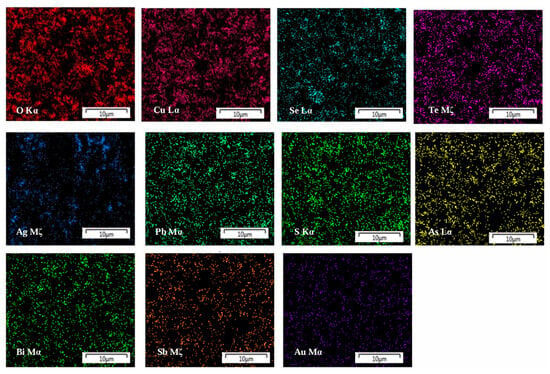

This study focuses on two core categories of secondary resources. The first category is metallurgical by-products, represented by copper/lead smelting anode slime, stainless steel pickling sludge, and precious metal refining slag. The typical composition of copper anode slime, expressed as a mass fraction, is as follows: Cu 5–15%, Pb 10–25%, Se 2–8%, Te 0.5–3%, Au 0.02–0.05%, Ag 0.5–0.8%, Pt 0.0005–0.002%, and Pd 0.001–0.003% [18,19,20,21,22]. Zhou et al. [23] systematically studied the leaching behavior of rare and precious metals such as Te, Au, Pt, and Pd and base metals such as Pb, Sn, Sb, and Ag in decoppered anode slime through electron probe microanalysis, thermodynamic analysis, and leaching experiments. The occurrence state and embedding characteristics of metals are revealed. Among them, metals Te, Au, Pt and Pd are mostly distributed on the surface of particles, high specific surface areas or metal alloy phases, while metals Sn, Sb, Ag, Ba and some Pb exist in sulfate blocks, oxide rod-like particles or stable shells, which are difficult to dissolve in the leaching process and thus remain in the slag. Figure 4 shows the distribution of main elements in copper anode slime. Copper and tellurium are evenly distributed in the raw materials. To further clarify the occurrence state and content of metals, the main mineral phases in the raw materials were determined by chemical phase analysis. The results show that Cu mainly exists in the form of CuO, CuSO4 and CuS. Te mainly exists in the form of elemental Te and AuTe2. Pb, Bi and Ag are dominated by PbSO3, Bi2O3 and Ag2S, respectively [24]. The carrier of automotive TWCs is cordierite, with γ-Al2O3 coated on its surface, and PGMs are supported on the γ-Al2O3 surface in the form of nanoparticles—there is a strong interaction between the active components and the carrier. In petrochemical hydrogenation catalysts, Pt is dispersed as single atoms in the pores of γ-Al2O3, while it reforms an alloy with Pt in the form of Re2O7 [25,26,27,28,29].

Figure 4.

Distribution maps of the main elements present in the coppered anode slime adapted from Ref. [24].

Synergistic smelting technology achieves efficient enrichment of platinum group metals and comprehensive utilization of all components by integrating multiple raw materials and processes, encompassing both raw material synergy and technological synergy. Raw material synergy optimizes the reaction system through the compatibility of different resources, thereby reducing the difficulty of processing single resources. For example, when high-nickel metallurgical slag is mixed with spent automotive catalysts at a specific mass ratio, Ni forms a Ni3Pt alloy during the pyrometallurgical process, increasing the Pt capture rate from 75% to 92% [30,31]. When copper anode slime is mixed with spent SCR catalysts, copper can reduce W6+ to W0; meanwhile, the presence of tungsten inhibits the formation of solid solutions between Cu and PGMs, thereby improving the recovery rate of PGMs [32,33,34]. The key parameters of raw material synergy include: optimization and regulation of slag type via thermodynamic calculations, particle size requirements to ensure sufficient contact between materials, and component complementarity.

Technical synergy integrates two or more complementary smelting and extraction technologies, which can effectively break through the inherent limitations of a single process in terms of reaction rate, selectivity, or final product purity. For example, the combination of microwave pretreatment and hydrometallurgical leaching leverages the selective heating effect of microwaves to alter the phase structure of carrier materials, thereby significantly enhancing the subsequent mass transfer and leaching processes. Similarly, the adoption of a synergistic strategy combining pyrometallurgical enrichment and ion exchange can first efficiently concentrate dispersed PGMs into intermediate products, and then achieve efficient separation and deep purification of the metals through a highly selective adsorption step [35,36,37].

The core recovery targets are strategic precious metals such as PGMs, Au, and Ag. Meanwhile, the high-value utilization of carriers and base metals is considered, aiming to achieve the circular economy goal of “comprehensive recovery of all components and zero waste discharge.”

2. Characteristics and Recovery Challenges of PGMs-Bearing Secondary Resources

2.1. Occurrence Characteristics of PGMs in Metallurgical By-Products

Copper anode slime is the primary carrier of PGMs in metallurgical by-products. Among them, Au and Ag exist in elemental or alloy forms, while Pt and Pd often form solid solutions with Se and Te, and are encapsulated by gangue minerals such as silica and lead silicate. Therefore, multi-stage separation processes are required to achieve their effective enrichment [38,39,40]. In stainless steel pickling sludge, Rh and Nb mostly exist as oxide solid solutions in the iron oxide matrix, making selective extraction difficult with traditional methods; due to the complex composition of precious metal refining slag, the dispersion of PGMs is further aggravated, and the difficulty of recovery is significantly increased [41,42].

2.2. Occurrence Characteristics of PGMs in Spent Catalysts

In spent petrochemical hydrogenation catalysts, vanadium and molybdenum are supported on the alumina carrier in the form of oxides: V exists as V2O5, while Mo exists as MoO3; nickel is present in a spinel structure and tightly bonded to the carrier; in contrast, platinum and palladium are embedded in the pores of the carrier as nanoparticles. Observations via high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) reveal that Pt particles exhibit an “isolated island-like” distribution within the pores. Additionally, some Pt particles form Pt-O-Al bonds with Al2O3. The strong interaction between the carrier and the active components hinders the diffusion of leaching agents—for instance, the leaching of Pt using traditional HNO3 requires more than 8 h [43,44,45].

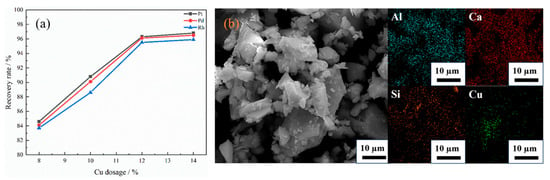

As shown in Figure 5a, when the addition amount of capture agent Cu is 8%, Cu cannot fully contact with platinum group metals (PGMs), resulting in extremely low recovery rates of Pt, Pd and Rh, all of which do not exceed 85%. When the addition amount of capture metal was increased to 10–12 wt %, the recovery rate was significantly higher than that of 8 wt %, indicating that increasing the amount of capture agent can effectively enhance the contact and capture probability of Cu with PGMs, thereby greatly improving the recovery efficiency of PGMs. The recovery rates of Pt, Pd and Rh were 96.3%, 96.12% and 95.52%, respectively, when the addition amount of capture metal was 12 wt %. However, when the addition amount of Cu was further increased to 14 wt %, the recovery rate did not change significantly, which may be due to the aggregation of the collector, caused by excessive Cu, which reduced the effective contact area. From the SEM images and EDS energy spectrum of the slag with 14 wt % Cu addition, as shown in Figure 5b, compared with the uniform distribution of Al, Ca and Si in the slag matrix, Cu shows a certain degree of aggregation. At the same time, the increase in the amount of Cu does not correspondingly increase the number of PGMs that can be captured [15,46,47,48,49].

Figure 5.

(a) Effect of Cu dosage on the recovery rates of PGMs; (b) SEM-EDS analysis of the slag with 14 wt % Cu addition adapted from Ref. [49].

In environmentally friendly selective catalytic reduction (SCR) catalysts, active components (such as oxides of tungsten and vanadium) and precious metals (such as palladium) are typically highly dispersed on the titanium dioxide carrier in specific chemical forms. Among them, PGMs tend to exist in an atomically dispersed state and form strong-interaction metal–oxygen–titanium chemical bonds with the carrier surface, thus achieving stable anchoring. However, during long-term catalytic reactions, the TiO2 carrier itself undergoes an unfavorable phase transformation—converting from the highly active anatase phase to the low-specific-surface-area rutile phase. This structural change directly leads to a significant decrease in the effective surface area of the carrier, which in turn results in a notable reduction in the number of active sites of PGMs. Therefore, when recovering PGMs from deactivated catalysts, the primary step is usually pretreatment to decompose or destroy the carrier structure that has undergone phase transformation and sintering, thereby exposing and releasing the encapsulated precious metal active sites [50,51,52].

2.3. Common Challenges in Recovery

The core process challenge in the efficient recovery of PGMs from complex secondary resources stems from the inherent characteristics of the material system [2,53,54,55,56]. The primary challenge lies in the bottleneck of selective separation: PGMs and associated base metals exhibit high similarity in redox potential, acid-base solubility, and surface physical properties. This makes it difficult for traditional chemical reagents to achieve precise targeted leaching; furthermore, undesirable alloying is prone to occur during pyrometallurgical smelting, leading to the dispersion and loss of target metals. Secondly, the severe constraints on reaction kinetics cannot be ignored: raw materials mostly have a heterogeneous composite structure, with precious metal active sites encapsulated within a dense carrier matrix. During hydrometallurgical leaching, reagents need to penetrate multiple mass transfer barriers composed of liquid films and carrier pores, and the slow intra-pore diffusion step often becomes the rate-limiting link; during pyrometallurgical smelting, the high-viscosity molten slag significantly hinders the aggregation and sedimentation separation of precious metal droplets. Both scenarios collectively result in long process cycles and limited efficiency. Finally, the current technical routes generally lack the concept of comprehensive component resource utilization. Most of them only focus on the extraction of PGMs, while the carrier matrices, rich in elements such as aluminum and silicon and valuable base metals, are disposed of as waste residues.

3. Development and Milestones of Traditional Synergistic Smelting Technology

Traditional synergistic smelting technology takes “pyrometallurgical enrichment–hydrometallurgical separation” as its core logic. It realizes the recovery of PGMs through the coupling of multiple processes and has undergone an evolutionary process from a single technology to the synergy of multiple technologies.

3.1. Pyrometallurgical Synergistic Smelting Technology

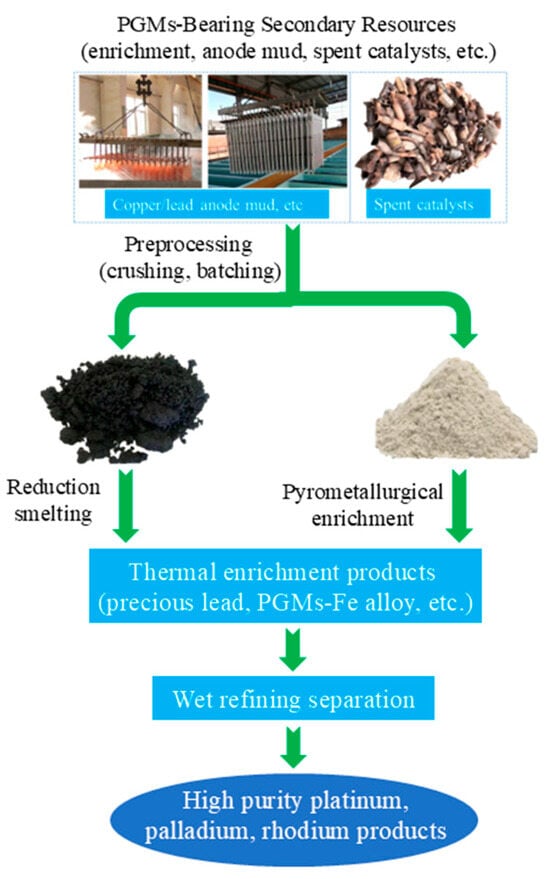

Figure 6 outlines the traditional pyrometallurgical process for recovering platinum group metals (PGMs) from secondary resources, including anode mud and spent catalysts. The process begins with preprocessing steps of crushing and batching the raw materials, which are then subjected to either reduction smelting or pyrometallurgical enrichment to generate thermal enrichment products such as precious lead and PGMs-Fe alloy. These enriched intermediates undergo subsequent wet refining separation, ultimately yielding high-purity platinum, palladium, and rhodium products. A landmark milestone in this field is the industrialization of the pyrometallurgical smelting process for copper anode slime [26,57,58,59]. In the mid-20th century, Outokumpu Oyj of Finland developed the “Kaldo furnace smelting—electrolytic refining” synergistic process. This process involves mixing copper anode slime with lead concentrate for smelting, using lead as a collector for PGMs. After smelting, a noble lead alloy containing PGMs is formed at the bottom; subsequently, lead and precious metals are separated through electrolysis, which improves the recovery rates of Au and Ag [60].

Figure 6.

Traditional pyrometallurgical process flow chart.

To address the challenge of resource utilization of spent petrochemical catalysts, pyrometallurgical synergistic smelting can effectively achieve oxidative removal of impurities and chemical activation of target metals (e.g., vanadium, molybdenum). The roasted product undergoes subsequent hydrometallurgical sequential separation steps, such as water leaching, precipitation, and ion exchange, enabling the sequential extraction of high-value components including V and Mo. The separated residue containing elements like nickel and aluminum is then further converted into economically valuable ferronickel alloy products through a reduction smelting process [61,62,63].

The advantages of pyrometallurgical synergy lie in its large processing capacity and strong adaptability. However, it faces bottlenecks such as high energy consumption, large carbon emissions, difficulty in significantly reducing CO2 emissions per unit product, and easy loss of low-content PGMs along with flue dust [64,65].

3.2. Hydrometallurgical Synergistic Smelting Technology

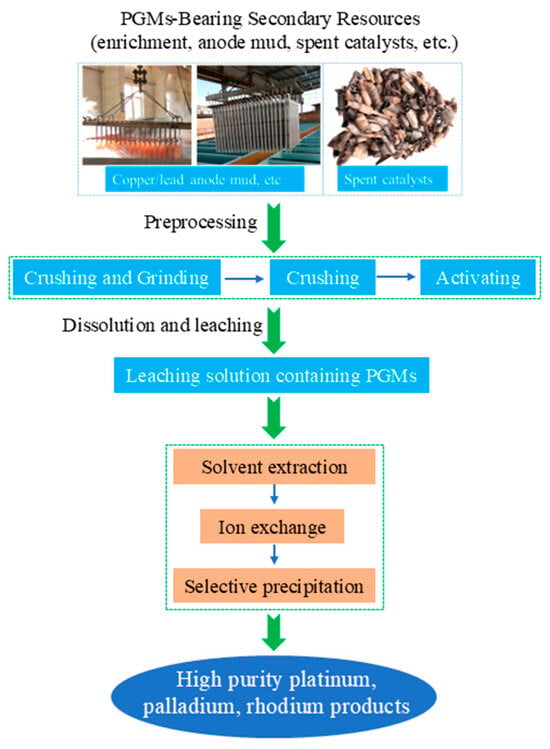

Hydrometallurgical synergy takes “selective leaching—solvent extraction separation” as its core, addressing the challenge that pyrometallurgy struggles to separate rare and precious metals [66,67,68]. Figure 7 depicts the traditional hydrometallurgical process for recovering platinum group metals (PGMs) from secondary resources, such as anode mud and spent catalysts. The process starts with preprocessing steps of crushing, grinding, and activating the raw materials, followed by dissolution and leaching to obtain a PGM-containing leachate. This leachate is then purified and separated via solvent extraction, ion exchange, or selective precipitation, ultimately yielding high-purity platinum, palladium, and rhodium products. For platinum–palladium concentrates with complex compositions, a synergistic treatment process integrating oxidative roasting, enhanced chlorination leaching, and sequential solvent extraction demonstrates promising application potential [69]. First, this process preprocesses the material through oxidative roasting. Under the action of additives, associated elements such as selenium and tellurium are converted into soluble salts, enabling preliminary separation and enrichment. Subsequently, enhanced leaching is conducted in a strongly oxidizing chlorine-containing medium, which can efficiently convert precious metals like platinum and palladium into stable chloro-complex acid forms, thereby obtaining a precious metal leachate with a high leaching rate. Finally, based on the significant differences in the chemical properties of different metal chloro-complexes, by precisely controlling the redox potential and selecting extractants with specific structures, the sequential separation and recovery of valuable metals such as Au, Pd, and Pt with high selectivity and high purity can be achieved. K. Hatzilyberis et al. [70]. proposed an intensified hydrometallurgical process for the efficient recovery of scandium from red mud. By employing a hybrid continuous-batch flow design and a non-conventional leaching-solution recirculation strategy, the study achieved both a reduction in acid consumption and an increase in scandium concentration. A systematic modeling approach was adopted, integrating mass, elemental, and energy balances, while incorporating an economic objective function that is based on profit maximization for synergistic optimization. This approach overcomes the limitations of traditional cost-minimization models. Under mild operating conditions—specifically, a solid-to-liquid ratio of 33.3%, an acid concentration of 0.31 M, and a temperature of 32 °C—the process simultaneously meets the requirements for subsequent ion-exchange steps and prevents silica-gel formation.

Figure 7.

The traditional hydrometallurgical process flow chart for recovering PGMs from secondary resources.

The advantages of hydrometallurgical synergy lie in its high selectivity and low energy consumption. However, it has issues such as high reagent consumption, great difficulty in wastewater treatment, and low recovery rates of insoluble metals [71,72,73].

3.3. Pyrometallurgical–Hydrometallurgical Combined Synergistic Technology

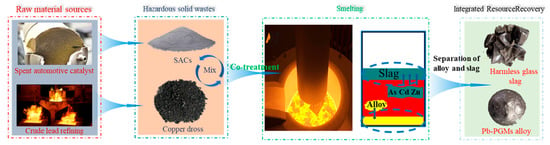

The coupling of pyrometallurgy and hydrometallurgy represents the most advanced form of traditional technologies. Figure 8 illustrates the pyrometallurgy–hydrometallurgy combined synergistic process for recovering metals from copper anode slime and spent automotive catalysts. The process starts with raw materials, including spent automotive catalysts and byproducts from crude lead refining, which are mixed with hazardous solid wastes such as spent automotive catalyst powder (SACs) and copper dross for co-treatment. The mixture is then subjected to smelting, where hazardous elements like As, Cd, and Zn are immobilized in the slag phase, while valuable metals are concentrated into a Pb-PGMs alloy. Following smelting, the slag and alloy are separated, yielding a harmless glassy slag and a Pb-PGMs alloy, thus achieving integrated resource recovery and hazardous waste reduction. Guided by the synergistic logic of “pyrometallurgical enrichment for dimensionality reduction–hydrometallurgical separation for purification,” it balances the processing scale and selectivity [74,75,76]. For the recovery of spent automotive exhaust catalysts, trace PGMs are first enriched in an alloy phase via pyrometallurgical collection, followed by hydrometallurgical dissolution and purification [77,78]. For the recovery of spent lithium-ion batteries, elements such as cobalt, nickel, and lithium are first enriched in alloys and flue dust, respectively, through pyrometallurgical reduction, followed by separate hydrometallurgical leaching and separation [79,80,81]. For the treatment of metallurgical flue dust, roasting and smelting are employed to volatilize and enrich zinc and lead, after which the enriched products undergo hydrometallurgical electrolysis or leaching [82,83]. Additionally, in the resource utilization of electronic waste, multi-metals are enriched in a crude metal phase through incineration and smelting, and then various rare and precious metals are refined, separated, and purified via hydrometallurgy [84,85,86]. These cases collectively confirm that this technical system utilizes pyrometallurgy to simplify material phases and enable large-scale processing, while leveraging hydrometallurgy to achieve highly selective separation. It represents the optimal industrial approach for balancing the processing capacity and recovery efficiency.

Figure 8.

Process flow chart of copper anode slime and waste catalyst recovery metal by pyrometallurgy–hydrometallurgy combined synergistic treatment.

The “converter blowing–pressure leaching” combined process is a typical technical paradigm of in-depth pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical coupling in the field of modern metallurgy [87,88,89]. Its core lies in using pyrometallurgical converter blowing to achieve phase reconstruction and preliminary enrichment of target metals in complex materials under high-temperature oxidation conditions, thereby creating stable and reactive precursors for subsequent hydrometallurgical treatment. Subsequently, pressure leaching is applied to efficiently and selectively dissolve target metals in an enhanced environment of high temperature and high pressure, while high-value or insoluble components are directionally enriched in the leaching residue. This process synergizes the dual advantages of pyrometallurgy (large processing scale and strong adaptability) and hydrometallurgy (accurate separation and relatively low energy consumption). It not only significantly improves the comprehensive recovery rate and selectivity of valuable metals but also effectively reduces the energy consumption and environmental load of the entire process. It represents a key technical path for the development of complex polymetallic resources, especially refractory secondary resources, towards green, efficient, and intensive recovery.

While this technical system is already mature, it has yet to overcome three inherent limitations: the long reaction cycle, the high reagent consumption, and the low processing efficiency for complex heterogeneous loads—such as “slag-metal–organic matter” mixtures and resin-containing spent catalysts, which are prone to coking during pyrometallurgical processing and emulsification during hydrometallurgical processing [90,91,92]. These intrinsic limitations—prolonged reaction cycles, high energy and reagent consumption, and inadequate adaptability to complex heterogeneous matrices—highlight the inherent challenges of conventional pyro-hydrometallurgical systems. Specifically, the reliance on external heat conduction results in significant energy losses and temperature gradients, while the limited selectivity of chemical reagents and slow intra-particle diffusion hinder the efficient liberation and recovery of finely dispersed PGMs from refractory carriers. These bottlenecks collectively underscore the pressing need for alternative energy-input methods that can enhance process efficiency, selectivity, and sustainability.

3.4. Summary of Limitations of Conventional Synergistic Smelting Technology

Despite the industrial maturity and widespread adoption of conventional pyro-hydrometallurgical synergistic smelting, several inherent limitations persist. The process cycle is often prolonged, typically requiring multiple unit operations from pretreatment to separation and purification, which can extend from several hours to days. In terms of energy consumption, the pyrometallurgical stage necessitates maintaining elevated temperatures (generally exceeding 1500 °C), accompanied by substantial CO2 emissions. Furthermore, conventional methods exhibit limited adaptability to complex heterogeneous feedstocks. For instance, composite systems such as “slag–metal–organic” mixtures are prone to coking during pyrometallurgical treatment and emulsification during hydrometallurgical processing. The efficiency of recovering low-grade and highly dispersed platinum group metals (PGMs) remains suboptimal, particularly within complex matrices where active components are often insufficiently liberated. These constraints have motivated the exploration of more efficient and environmentally benign alternative metallurgical routes.

4. Microwave-Assisted Synergistic Smelting Technology

4.1. Core Principles and Advantages of Microwave-Assisted Synergistic Smelting

In response to the limitations of conventional smelting, microwave-assisted synergistic technology emerges as a promising alternative that directly addresses several key bottlenecks. Unlike traditional heating that relies on conduction and convection, microwave energy delivers heat through direct interaction with materials, enabling rapid and volumetric heating. This fundamental difference in energy transfer provides a novel pathway to overcome the inefficiencies that are inherent in conventional processing, particularly for complex, low-grade secondary resources. Specifically, the selective and volumetric heating characteristics of microwaves, coupled with their non-thermal effects, offer targeted solutions to the problems of high energy consumption, slow kinetics, and poor selectivity encountered in traditional routes.

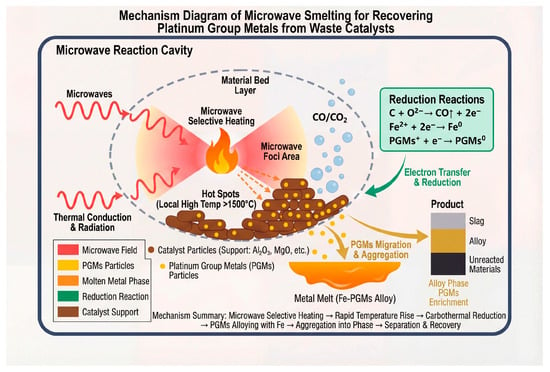

Figure 9 illustrates the mechanism of recovering platinum group metals (PGMs) from spent catalysts via microwave smelting. This schematic demonstrates the core mechanism of microwave-assisted smelting for PGMs recovery: within the microwave reaction cavity, microwaves selectively heat catalyst particles supported on carriers such as alumina and magnesia, generating localized “hot spots” with temperatures exceeding 1500 °C. Heat further propagates through conduction and radiation, triggering a carbothermal reduction reaction. Carbon acts as a reductant, undergoing oxidation and releasing electrons that subsequently reduce iron ions and PGM ions to their metallic states. The reduced PGMs then migrate into the molten iron phase, forming an iron–PGM alloy melt, thereby achieving enrichment and agglomeration. Ultimately, phase separation occurs within the system, resulting in a slag layer composed of oxidized carrier materials, a PGM-enriched alloy layer, and a layer of unreacted materials, thus accomplishing the separation and recovery of PGMs.

Figure 9.

Mechanism diagram of microwave smelting for recovering platinum group metals from spent catalysts.

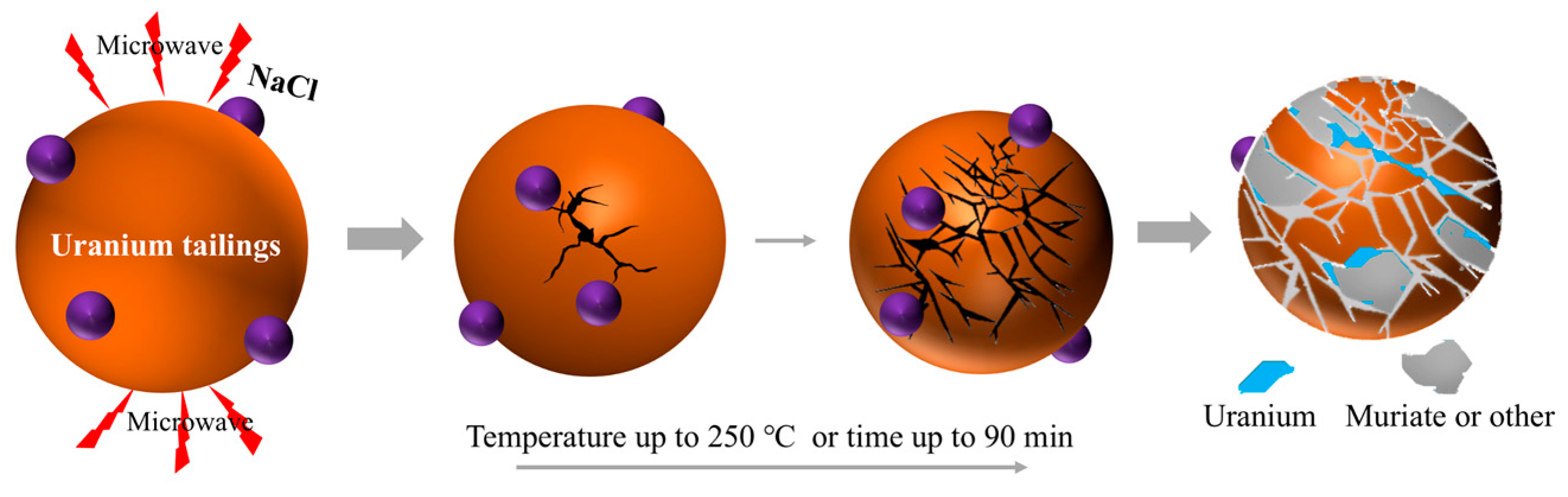

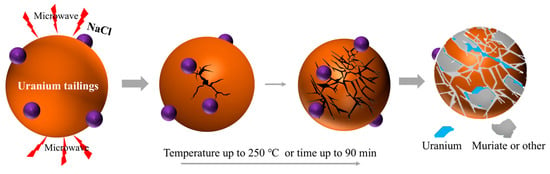

Microwave heating is characterized by selective heating and volumetric heating. Its coupling with traditional smelting processes provides a brand-new approach to addressing the bottlenecks in PGMs recovery, driving synergistic smelting technology into a new phase of “high efficiency and green development” [93,94,95]. Hu et al. [96] studied the microwave roasting of uranium-containing waste residue, and the roasting process is shown in Figure 10. At the initial stage of the microwave roasting experiment, the mixture is in a low-temperature state, the dielectric loss is low and the microwave penetration depth is large. Because microwave heating has the characteristics of in situ heating and selective heating, the high dielectric properties such as Fe2O3 and Al2O3 in the material are preferentially heated so that the internal temperature increases rapidly and exceeds the surface temperature. However, the absorption properties of gangue and other phases are weak, thus forming a temperature gradient and generating thermal stress, which destroys the uranium-encapsulated structure. At the same time, the chlorination reaction further destroyed the mineral structure and expanded the exposed area of uranium. Microwave heating generates heat by causing polar molecules or free electrons in materials to vibrate through an electromagnetic field, and this synergy offers three core advantages. Through selective heating, it can directionally heat PGM compounds or carriers with strong microwave absorption capacity, achieving “targeted activation”. With volumetric heating, it avoids the “cold center” problem of traditional heating, ensures uniform temperature inside and outside the material, and accelerates mass transfer reactions. Through the non-thermal effect, the microwave field can promote molecular diffusion and interfacial reactions, thereby reducing the activation energy of reactions [97,98,99].

Figure 10.

Mechanism diagram of microwave roasting uranium-containing waste residue adapted from Ref. [96].

4.1.1. Microwave Heating Mechanism

Microwaves are electromagnetic waves with a frequency range of 300 MHz to 300 GHz, and the commonly used frequency in industry is 2.45 GHz. The essence of microwave heating is that materials generate heat through “polarization relaxation” or “free electron vibration” in an electromagnetic field, and this method is applicable to polar molecules or polar compounds [100,101]. In a microwave field, dipoles rapidly flip with the direction of the electric field, and heat is generated through intermolecular friction. For example, the sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution has a dielectric constant of ε′ = 55 and a relaxation time of τ = 10−11 s, which matches the microwave period, resulting in a heating efficiency of 90% [102]. When metal particles are dispersed in an insulating matrix, free electrons accumulate on the surface of the particles, forming a “charge double layer”. Under the action of an electric field, charge migration generates an electric current, which produces heat through Joule heating. For example, for Pt particles in spent catalysts in a microwave field, the current density generated by interfacial polarization can reach 105 A/m2, leading to a significant acceleration in the heat generation rate [103]. The microwave absorption performance of materials can be quantified by two parameters: the dielectric constant (ε′), which measures the energy storage capacity, and the loss factor (ε″), which measures the heat dissipation capacity. Specifically, a larger ε″ indicates stronger microwave absorption [104,105].

4.1.2. Core Advantages of Microwave-Assisted Synergy

Microwave-assisted synergy technology demonstrates three core advantages in the field of resource recovery: selective heating enables “targeted activation” of specific components. For instance, when processing spent automotive catalysts, microwaves preferentially heat the γ-Al2O3 coating (a strong microwave absorber) to above 800 °C, while the cordierite carrier (with low dielectric loss) remains near 300 °C. This contrast directly counteracts the non-selective, bulk overheating that is typical of conventional furnaces, preventing carrier sintering and preserving the porous structure that is crucial for subsequent leaching [106,107]. The core advantage of microwave-assisted synergy technology lies in its unique energy transfer mechanism. The volumetric heating mode effectively overcomes the temperature gradient problem caused by heat conduction in traditional external heating methods, enabling more uniform heating of materials and thereby significantly improving the stability of subsequent leaching processes [108,109]. Non-thermal effects of the microwave field, such as enhanced molecular polarization and reduced activation energy, can significantly accelerate reaction kinetics and improve leaching selectivity. This addresses the slow diffusion and inadequate reagent target contact that often limit the efficiency of conventional hydrometallurgical processes [110,111]. Collectively, these characteristics indicate that microwave technology goes beyond the scope of merely providing thermal energy and has become an advanced technical means that is capable of regulating and enhancing metallurgical processes at the molecular level.

These advantages endow the synergy between microwave technology, pyrometallurgical processes, and hydrometallurgical processes with inherent feasibility, forming three major technical branches: “microwave-enhanced roasting”, “microwave-assisted leaching”, and “microwave–multifield coupling”.

4.2. Microwave–Hydrometallurgical Synergy Technology

4.2.1. Microwave-Assisted Alkali Fusion—Hydrometallurgical Separation Technology

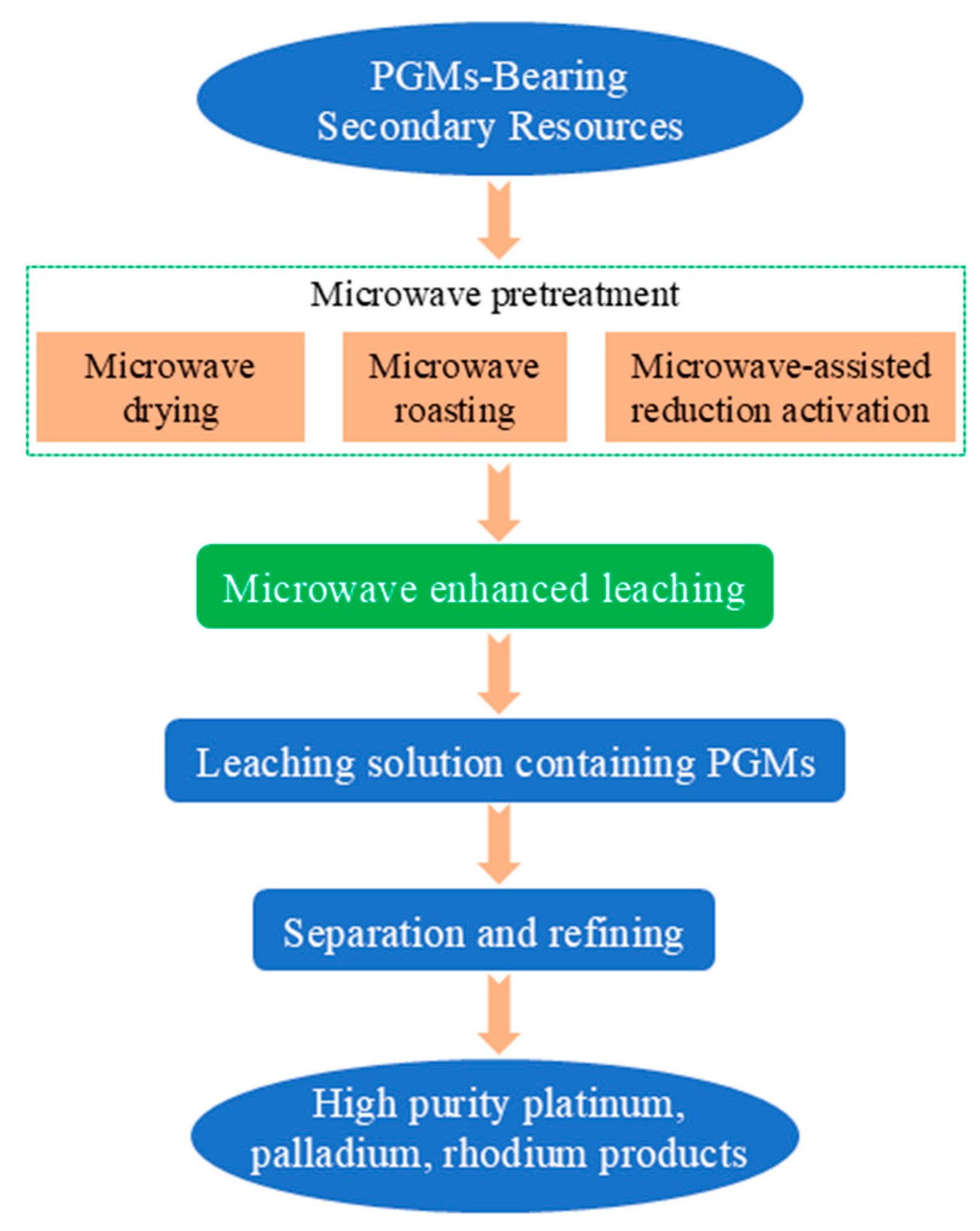

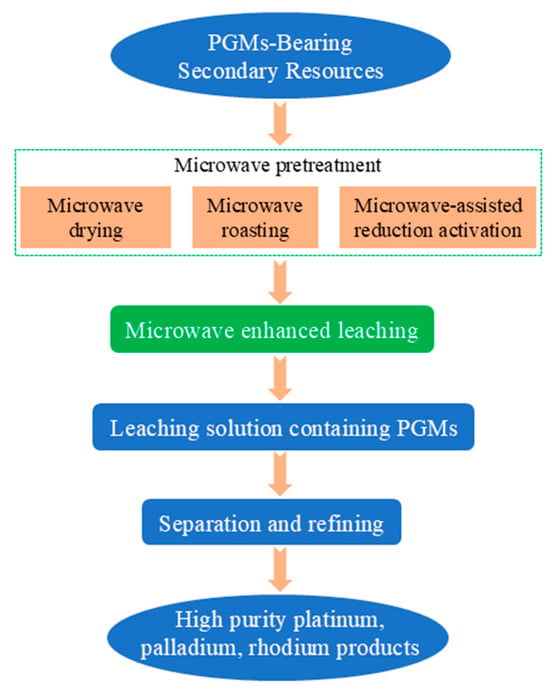

The coupling of microwave technology and hydrometallurgy is currently the most actively researched direction, with its core lying in enhancing the leaching process through microwave technology to overcome the bottleneck of mass transfer resistance. Figure 11 presents the microwave-assisted hydrometallurgical process for enhanced leaching of platinum group metals (PGMs) from PGM-bearing secondary resources. The process begins with microwave pretreatment, which includes microwave drying, roasting, and reduction activation, to modify the material structure and improve leachability. This is followed by microwave-enhanced leaching to obtain a PGM-containing leachate, which is then purified via separation and refining steps, ultimately yielding high-purity platinum, palladium, and rhodium products.

Figure 11.

Microwave-assisted hydrometallurgy strengthening PGMs leaching process flow chart.

This technology achieves a leap in efficiency through multi-scale synergistic effects: at the microscale, the electromagnetic perturbation and local superheating effect of the microwave field can significantly reduce the activation energy of chemical reactions and selectively weaken the chemical bonding between target metals and the carrier matrix, thereby essentially enhancing the interfacial reaction kinetics [112,113]. At the mesoscale, the thermal stress induced by selective heating (based on the dielectric properties of materials) can generate a microcrack network inside particles. This significantly increases the penetration channels for leaching agents and the specific surface area for reactions, directly breaking through the internal diffusion barrier. At the macroscale, the uniform volumetric heating mode eliminates the temperature gradient caused by traditional heat conduction. Combined with the micro-region convection effect induced by microwaves, it comprehensively enhances the mass transfer efficiency of the system [114,115]. Therefore, the introduction of microwaves goes beyond the mere function of heating and has become a multi-scale enhancement tool that is capable of simultaneously optimizing reaction kinetics and mass transfer processes. It provides a technically transformative pathway for processing low-grade and refractory resources, with its future development focusing on the design of continuous reactors and the engineering breakthroughs in multi-field coupling processes.

4.2.2. Microwave-Assisted Deep Eutectic Solvent Leaching Technology

Microwave-assisted deep eutectic solvent leaching technology is a novel recovery process that combines green solvents with high-efficiency energy fields. Its core lies in utilizing the designability, low toxicity, and biodegradability of deep eutectic solvents, coupled with the unique advantages of microwave heating (volumetric heating and selective heating) to achieve rapid and efficient leaching of valuable metals from spent lithium-ion batteries under mild conditions (typically 70–100 °C). This technology can shorten the traditional leaching process (which takes several hours) to just a few minutes. Moreover, it has demonstrated process evolution—from efficient co-leaching (e.g., the choline chloride–formic acid system achieves nearly 100% extraction of lithium and cobalt) to selective in situ separation (e.g., the choline chloride–oxalic acid system with high water content enables preferential leaching of lithium and direct precipitation of cobalt). It not only significantly reduces energy consumption and secondary pollution but also eliminates the need for additional precipitants, thereby simplifying the separation process [116,117,118,119]. Although challenges remain in solvent recycling, equipment scaling-up, and applicability to complex battery systems, this technology has demonstrated great potential as a key green, efficient, and low-cost technology for battery recycling. It provides an innovative solution for promoting resource circulation and sustainable development.

4.3. Microwave–Pyrometallurgical Synergy Technology

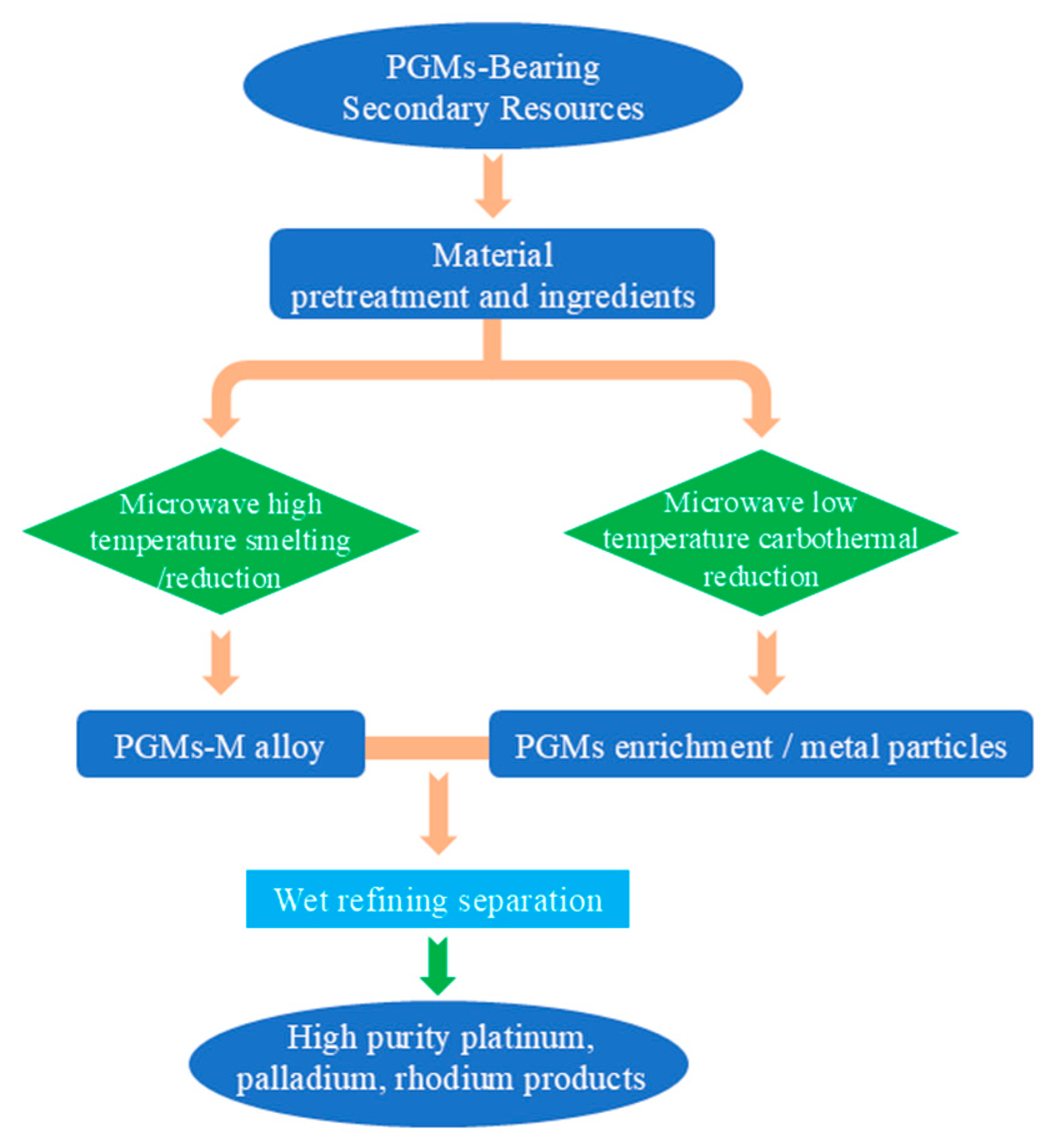

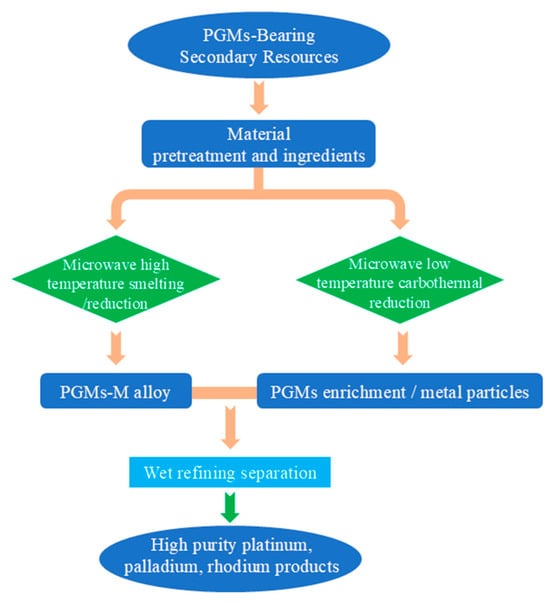

The coupling of microwave technology and pyrometallurgy focuses on reducing smelting energy consumption and shortening reaction time. A typical application is “microwave-assisted reductive roasting for platinum group metal enrichment,” which is suitable for low-grade materials such as metallurgical slags and spent catalysts. Figure 12 illustrates the microwave-based process for recovering platinum group metals (PGMs) from PGM-bearing secondary resources. The process starts with material pretreatment and batching of raw materials, which are then split into two parallel pathways: microwave high-temperature smelting/reduction to produce a PGMs-M alloy, and microwave low-temperature carbothermal reduction to generate PGMs-enriched metal particles. These enriched intermediates are combined and subjected to wet refining separation, ultimately yielding high-purity platinum, palladium, and rhodium products.

Figure 12.

Microwave smelting/reduction secondary resource recovery PGMs metal process flow chart.

4.3.1. Microwave–Pyrometallurgical Enrichment of Platinum Group Metals in Metallurgical Slags

As a core metallurgical technology, microwave–pyrometallurgical enrichment exhibits unique advantages in the efficient recovery of rare and precious metals from various complex, low-grade secondary resources. To gain a deeper understanding of this process, we will examine the recovery processes of silver and PGMs from three types of materials separately: copper anode slime smelting slags, alumina-based spent catalysts, and automotive exhaust spent catalysts.

To address the challenge of silver recovery from copper anode slime smelting slags produced by Kaldo furnaces, a two-step process of “reductive smelting–vacuum metallurgy” has been developed. First, reductive smelting is employed to leverage the trapping effect of lead, enabling the co-enrichment of dispersed Ag, Pb, and Bi into an alloy. Subsequently, vacuum distillation separation is carried out based on the differences in metal vapor pressures. Ultimately, this process achieves efficient and clean recovery and enrichment of silver [120]. To address the challenge of recovering PGMs from alumina-based spent catalysts, an “iron trapping” method based on a silica-free slag system design is proposed. By optimizing the slag composition to reduce its density and viscosity, iron powder is used as a trapping agent to enable the collision and fusion of PGM particles with iron microspheres, forming a solid solution. This method achieves an extremely high recovery rate, and its mechanism lies in the thermodynamic driving force that reduces the surface Gibbs free energy of the system [121,122]. Further, addressing the recovery of low-grade PGMs from the leaching residues of spent automotive catalysts, the “slag type design-iron trapping” process has been advanced. By systematically designing multi-component slag systems to optimize their physicochemical properties, efficient enrichment of PGMs and extremely low residual PGMs content in the slag can be achieved through short-duration smelting under optimal conditions. Additionally, the separation mechanism between the metallic phase and the slag phase has been revealed from the perspectives of chemical bonding and material property differences. Theoretical calculations confirm that PGMs spontaneously enter the iron matrix in the form of substitutional solid solutions to achieve enrichment, and the final smelting slag can be recycled for resource utilization [26]. In conclusion, these studies collectively demonstrate that pyrometallurgical enrichment technology, through sophisticated slag design, appropriate selection of trapping agents, and in-depth understanding of separation mechanisms, can efficiently and cleanly enrich and recover precious metals from complex secondary resources. This highlights the technology’s great potential and application value in the field of resource recycling.

4.3.2. Microwave–Pyrometallurgical Activation of Spent SCR Catalysts

As an efficient and green resource recovery strategy, microwave–pyrometallurgical activation technology has demonstrated significant potential in the field of resource utilization of spent catalysts. By coupling pretreatment activation driven by an energy field with a high-temperature pyrometallurgical process, this technology can significantly improve reaction efficiency and product purity.

Taking spent fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) catalysts as an example, researchers have developed an integrated process combining microwave-assisted acid activation pretreatment and microwave-heated crystallization synthesis. In this process, acid solutions are used in a microwave field to selectively remove metal impurities and activate aluminum sources, which significantly enhances the crystallinity of Y-type zeolite in the spent catalysts. Furthermore, under mild microwave heating conditions (100 °C, 2 h), high-purity Y-type zeolite products with small particle sizes are efficiently synthesized. This highlights the enhancing effect of the microwave field in both the activation and synthesis stages [123]. Another study, focusing on the treatment of spent selective catalytic reduction (SCR) catalysts, proposed a recovery route involving water leaching after activation by roasting with NaCl-NaOH composite salts. By optimizing the composite salt ratio and roasting parameters (750 °C, 2.5 h), this process leverages the molten mass transfer effect of NaOH and the oxidative catalytic effect of Cl2 generated from NaCl decomposition. It successfully converts vanadium and tungsten in the spent catalysts into soluble salts, achieving efficient simultaneous leaching of the two metals (vanadium: 93.25%, tungsten: 99.17%) [124]. Together, these two studies demonstrate a core strategy: modifying the physicochemical properties of materials through pretreatment (activation) steps driven by microwave or thermal energy fields, thereby creating favorable reaction conditions for subsequent pyrometallurgical synthesis or roasting extraction. This synergistic concept of microwave–pyrometallurgical activation provides key technical support for the green and efficient resource utilization of valuable components in spent catalysts.

4.4. Microwave–Multi-Field Coupling Synergy Technology

4.4.1. Microwave-Assisted Multi-Technology Coupling for Efficient and Comprehensive Treatment

The multi-field coupling of microwave technology with ultrasound, induction heating, and other technologies solves the problem of low efficiency of single microwave heating for conductive materials and enables the full-component treatment of heterogeneous loads.

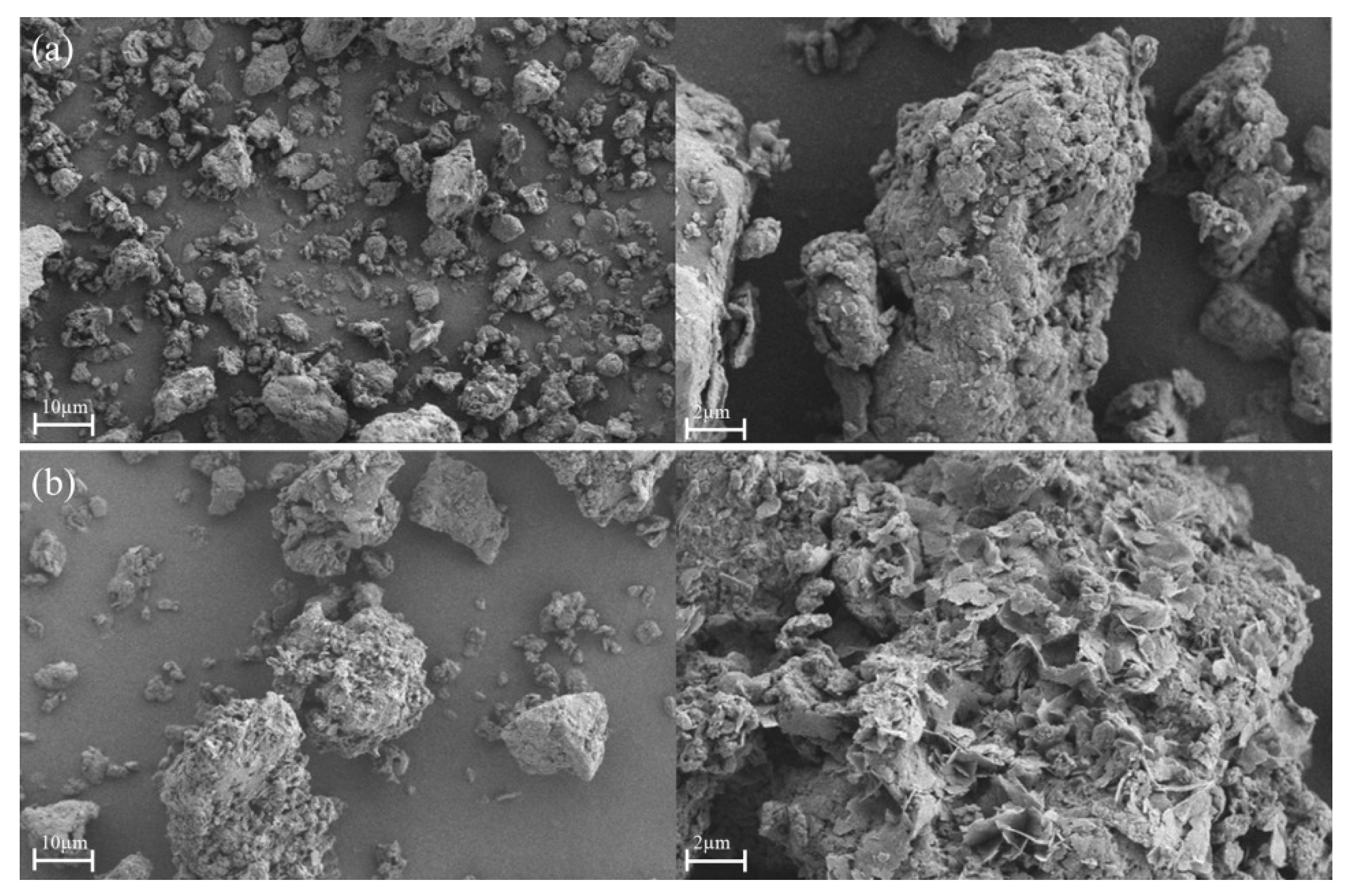

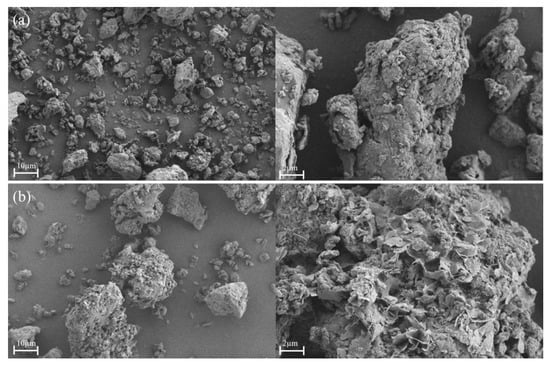

Taking the coupling of microwave and ultrasound as an example, the core advantage of this technology lies in the complementarity and enhancement between microwave’s overall/selective heating and molecular polarization effects, and ultrasound’s local cavitation, mechanical crushing, and mass transfer enhancement effects. The synergistic effect can more effectively destroy the material’s microstructures, increase active sites, and enhance reaction mass transfer and energy transfer. Studies have been conducted on improving the functional properties of corn bran insoluble dietary fiber (CBIDF), using ultrasound–microwave synergistic modification [125]. By comparing single ultrasound treatment, single microwave treatment, and ultrasound–microwave synergistic treatment, it was found that the synergistic treatment (U-M-CBIDF) achieved the best effect. Through the coupling of cavitation and thermal effects, the synergistic treatment destroyed the dense structure of CBIDF, reduced its particle size and crystallinity, and exposed more hydrophilic/lipophilic groups, thereby significantly improving its water-holding capacity, oil-holding capacity, and adsorption capacity for cholesterol and bile salts. This study also explored the synergistic enhancement effect of ultrasound and microwave pretreatment on the hydrogen production performance of palm oil mill effluent (POME) sludge. The results showed that all pretreatment methods could increase hydrogen production and COD (chemical oxygen demand) removal rate; among them, the ultrasound–microwave combined pretreatment had the most significant effect, with the highest cumulative hydrogen production (4080 mL H2/L-POME) and COD removal rate (75.56%), which were 12.14% and 21.42% higher than those of the untreated control group, respectively [126]. Ran et al. [127] used microwave and ultrasonic-assisted lignite leaching to remove ash. The microstructure changes in lignite before and after microwave–ultrasonic-assisted leaching are shown in Figure 13. Figure 13b shows that microwave-assisted treatment makes the surface of pulverized coal form a more layered structure, which may be related to the heating characteristics of microwave energy. Microwave heating is a non-uniform heating method that heats up the material by internal friction. In this process, the uneven distribution of energy leads to a temperature difference in different regions of pulverized coal. This temperature gradient causes thermal expansion and contraction on the surface of pulverized coal, which in turn causes structural changes. At the same time, the evaporation of water inside the pulverized coal during microwave heating will form steam pressure, and the rapid release of steam causes the formation and rupture of surface bubbles, thus forming a layered structure. In addition, microwave heating may cause chemical changes in the organic matter inside the pulverized coal to produce gaseous and solid products, and the covering layer formed by these products on the surface of the pulverized coal will also show a layered structure. The synergistic pretreatment destroys sludge flocs and releases organic matter through the cavitation effect of ultrasound. It further promotes the dissolution of organic matter and the availability of microorganisms by combining with the electromagnetic thermal effect of microwaves. This accelerates the hydrolysis and acidification process, optimizes the metabolic environment of hydrogen-producing microorganisms—mainly butyric acid-type fermentation—and ultimately achieves the dual goals of efficient wastewater treatment and clean energy recovery [128]. The synergy between the two overcomes the shortcomings of a single energy field in terms of action depth or reaction intensity, and realizes the effective connection between coal surface activation and in situ oxidation.

Figure 13.

The change in material microstructure: (a) before microwave–ultrasonic-assisted leaching of lignite and (b) after microwave–ultrasonic-assisted leaching of lignite adapted from Ref. [127].

4.4.2. Microwave-Assisted Fusion for Platinum Group Metal Recovery from Spent Catalysts

In the field of synergistic smelting for metal recovery, especially for PGMs, the advantages and innovations of microwave technology are particularly prominent. Its core advantages focus on low energy consumption and high efficiency. By virtue of the selective heating mechanism, nickel matte (Ni3S2), as a strong microwave-absorbing collector, achieves targeted heating, enabling the recovery rates of platinum (Pt), palladium (Pd), and rhodium (Rh) to reach 98.59%, 97.91%, and 97.16% respectively, which has successfully addressed the long-standing industry challenge of rhodium recovery [37,63,129,130,131]. The environmental protection characteristics of this technology are equally impressive: smelting under a nitrogen atmosphere can reduce harmful emissions by more than 80%, and the slag can be further processed to produce glass-ceramics for resource utilization. Meanwhile, it is suitable for low-grade and complex raw materials, and can simultaneously recover associated metals such as nickel (Ni) and copper (Cu) while recycling PGMs, significantly improving resource utilization efficiency.

The innovations focus on the synergistic design of collectors and fluxes: nickel matte is introduced into the microwave smelting system for the first time, combined with Na2B4O7-Na2CO3 composite sodium salts, reducing the melting point of the slag to 1075 °C; the eddy current loss and swirling sedimentation effect induced by microwaves enhance the mass transfer process, significantly improving the separation efficiency of metals and slag; the optimal process window is locked through precise regulation of multiple parameters, and cross-field integration of microwave metallurgy and pyrometallurgical collection technology provides a transferable solution for the recovery of various secondary resources [132,133,134].

The core process of this technology is clear and straightforward: first, the spent catalyst and nickel matte are crushed and ground to 42.22 μm and 59.84 μm, respectively, then mixed uniformly at a mass ratio of nickel matte to spent catalyst of 1.25:1, Na2B4O7 to spent catalyst of 0.575:1, and Na2CO3 to spent catalyst of 0.125:1. Subsequently, the mixture is placed in a corundum crucible and put into a 2.5 kW, 2.45 GHz industrial microwave oven for microwave smelting at 1250 °C for 2 h under the protection of a nitrogen atmosphere [135,136,137]. After cooling, the efficient separation of PGM-enriched nickel matte and glassy slag can be achieved by virtue of density differences—the nickel matte enters the subsequent refining process, while the slag is used for resource utilization. It should be noted that the particle fineness of raw materials must be strictly controlled to prevent uneven microwave heating; moreover, the cooled nickel matte is in the form of natural granules, eliminating the need for additional crushing and separation, which greatly simplifies the process steps.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

The recovery of PGMs from metallurgical by-products and spent catalysts is undergoing a pivotal transition from single-resource processing toward multi-matrix synergistic utilization. This review indicates that although the traditional pyrometallurgical enrichment combined with hydrometallurgical separation remains an industrially mature and widely applied approach, it still suffers from inherent drawbacks such as high energy consumption, long reaction cycles, and limited adaptability to complex heterogeneous materials such as slag–metal–organic mixtures. In contrast, microwave-assisted synergistic smelting demonstrates transformative potential. By leveraging selective heating and non-thermal effects, this technology effectively addresses key bottlenecks of conventional processes, lowering smelting temperature, reducing energy consumption, shortening reaction time, and enabling the recovery of platinum, palladium, and rhodium, thereby overcoming the long-standing challenge of rhodium recovery. The emergence of technical branches, including microwave-enhanced roasting, microwave-assisted leaching, and microwave multi-field coupling, further underscores its excellent applicability to low-grade, refractory, and compositionally complex secondary resources. Despite these promising achievements, further progress is required to fully realize industrialization, with future research and development focusing on four strategic directions: priority should be given to designing microwave–ultrasound–induction coupling systems, integrating ultrasound to enhance mass transfer and induction heating to complement the selective heating of conductive phases for improved uniformity and controllability in treating heterogeneous materials. It is essential to establish intelligent control modules based on real-time temperature field monitoring, developing precise algorithms to dynamically regulate microwave power and frequency for accurate matching with evolving material dielectric properties. Future work should transition from macroscopic observations to microscopic mechanisms, combining molecular dynamics simulations with in situ characterization to elucidate microwave non-thermal effects during PGM leaching and establishing quantitative correlations among dielectric behavior, reaction kinetics, and product purity to provide a theoretical foundation for process optimization; finally, moving from laboratory and pilot-scale experiments toward industrial demonstration is critical, with validation of long-term operational stability, energy efficiency, and economic feasibility under continuous production conditions to provide solid theoretical support for the optimization of process parameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W. and J.Y.; Methodology, L.Y. and X.Y.; Software, X.S. and M.H.; Validation, L.Y., X.Y. and S.G.; Formal analysis, Q.S., X.S., M.H. and L.G.; Investigation, L.G., Q.S. and X.S.; Resources, S.G.; Data curation, J.Y.; Writing—original draft preparation, L.W.; Writing—review and editing, L.W., L.Y., S.G. and X.Y.; Visualization, S.G.; Supervision, X.Y. and S.G.; Project administration, L.Y.; Funding acquisition, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Shandong Province Key Research and Development Plan Major Scientific and Technological Innovation Project (2023CXGC010903) and Yibin City’s project to attract high-level talents (2025YG02).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors (Shenghui Guo, Li Yang) would like to acknowledge the Xing Dian talent support program of Yunnan Province.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Leyi Wang and Qifei Sun were employed by the company Shandong Zhaojin Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Weng, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Muroya, Y.; Yamashita, S.; Cheng, S. Recovery of platinum group metal resources from high-level radioactive liquid wastes by non-contact photoreduction. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 458, 131852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinas, S.; Jermakowicz-Bartkowiak, D.; Pohl, P.; Dzimitrowicz, A.; Cyganowski, P. On the path of recovering platinum-group metals and rhenium: A review on the recent advances in secondary-source and waste materials processing. Hydrometallurgy 2024, 223, 106222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Chen, A.; Guo, X.; Li, D.; Lin, J. Recovery of Platinum Group Metals from Spent Automobile Exhaust Catalysts. JOM 2024, 76, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudd, G.M.; Jowitt, S.M.; Werner, T.T. Global platinum group element resources, reserves and mining—A critical assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 622–623, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Peng, Z.; Tian, R.; Ye, L.; Zhang, J.; Rao, M.; Li, G. Platinum-group metals: Demand; supply, applications and their recycling from spent automotive catalysts. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xv, B.; Li, Z.; Zha, G.; Liu, D.; Yang, B.; Jiang, W. Recovery of platinum group metals from spent automotive catalysts: Review of conventional techniques and vacuum metallurgy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 215, 108103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglo American. 2024 Sustainability Report; Anglo American PLC: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Iftekhar, S.; Heidari, G.; Amanat, N.; Zare, E.N.; Asif, M.B.; Hassanpour, M.; Lehto, V.P.; Sillanpaa, M. Porous materials for the recovery of rare earth elements, platinum group metals, and other valuable metals: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 3697–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.E.; Haque, N.; Northey, S.A.; Giddey, S. Platinum Group Metals: A Review of Resources, Production and Usage with a Focus on Catalysts. Resources 2021, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Li, D.; Feng, K.; Wang, H.; Wang, P.; Li, J. Assessing the supply risks of critical metals in China’s low-carbon energy transition. Glob. Environ. Change 2024, 86, 102825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhen, Z.; Zhao, R.; Yang, J.; Jia, H.; Wang, J. Biorecovery of platinum group metals to nanoparticles: Current status, prospects, and challenges. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Temirov, U.; Wang, J.; Chang, Z. Selective recovery of platinum group metals (PGMs) from aqueous solution: Advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 134947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, X.; Ding, Y.; Shi, Z.; Wu, B. Supply and demand of platinum group metals and strategies for sustainable management. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 204, 114821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Wang, X.; Yu, F.; Tian, M.; Wang, C.; Huang, G.; Xu, S. Recovery and value-added utilization of critical metals from spent catalysts for new energy industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 138295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, M.; Petersen, J. Recovery of Pt, Pd, and Rh from spent automotive catalysts through combined chloride leaching and ion exchange: A review. Hydrometallurgy 2024, 228, 106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, S.; Srivastava, R.R.; Kim, H.; Cheema, H.A. Hydrometallurgical recycling of palladium and platinum from exhausted diesel oxidation catalysts. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 248, 117029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.; Vinoba, M.; Kothari, R. Emerging role of organic acids in leaching of valuable metals from refinery-spent hydroprocessing catalysts, and potential techno-economic challenges: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 51, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Liu, F.; Chen, F.; Liao, C.; Zeng, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wan, X. Green Capture of Silver by Bismuth from Decoppered Anode Slime with Low Energy Consumption. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 2897–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Zha, G.; Zhang, X.; He, S.; Yang, B.; Jiang, W. One step to direct extracted gold and silver from industrial Cu-Ag-Sb-Au alloy by a convenient bimetallic electrolytic separation process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Vino, W.; Ordóñez, J.I.; Hernández, P. Alternatives for copper anode slime processing: A review. Miner. Eng. 2024, 215, 108789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, Z.; Shi, R.; Li, X.; Cui, Y. Issues Relevant to Recycling of Stainless-Steel Pickling Sludge. JOM 2018, 70, 2825–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Duan, F. Metal recovery and heavy metal migration characteristics of ferritic stainless steel pickling sludge reduced by municipal sludge. Waste Manag. 2022, 144, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liao, C.; Liu, F.; Zeng, Y. Leaching Behavior of the Main Metals of Decopperized Anode Slime. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 41, 2717–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Liu, F.; Zhou, S.; Liao, C.; Chen, F.; Zeng, Y. Leaching Behavior of the Main Metals from Copper Anode Slime during the Pretreatment Stage of the Kaldor Furnace Smelting Process. Processes 2022, 10, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Zhou, K.; Liang, C.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, F.; Li, C.; Sun, Z. Efficient leaching of precious metals from spent automotive three-way catalysts by TiO2 derived from Joule heating. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 523, 168415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Ding, Y.; Wen, Q.; Zhao, S.; He, X.; Zhang, S.; Dong, C. Slag design and iron capture mechanism for recovering low-grade Pt, Pd, and Rh from leaching residue of spent auto-exhaust catalysts. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañete, S.; Faba, L.; Ordóñez, S. Continuous hydrogenation of plastic wastes pyrolysis oil over used hydrotreatment catalysts. Catal. Today 2025, 454, 115308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Ma, X.; Gu, W.; Chen, S.; Hao, W.; Shih, K. A sustainable strategy for PGMs recovery from spent automotive catalysts and photocatalyst construction based on upcycled materials. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 134896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Guo, S.; Gao, L.; Yang, L.; Yan, H.; Zeng, H. Revolutionizing titanium production: A comprehensive review of thermochemical and molten salt electrolysis processes. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2026, 33, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Xie, Y.; Qi, T. Comprehensive recycling of slag from the smelting of spent automotive catalysts. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 350, 127661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Tang, J.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Y. A review of metallurgical processes and purification techniques for recovering Mo, V, Ni, Co, Al from spent catalysts. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, R.; Lv, Z.; Li, S.; He, J.; Song, J. Hydrogen-rich reduction coupled with wet leaching for the conversion of spent SCR catalysts into carbide solid solutions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, A.B.C.; Pasupuleti, K.S.; Jeon, J.H.; Thenepalli, T.; Bak, N.-H.; Sampath, S.; Jayababu, N.; Kim, M.-D.; Lee, J.-Y.; Jyothi, R.K. Sustainable solution to the recycling of spent SCR catalyst and its prospective gas sensor application. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 25, 100649. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W. Recovery of tungsten and titanium from spent SCR catalyst by sulfuric acid leaching process. Waste Manag. 2023, 155, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ou, X.; Sun, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Yang, S.; Chen, Z. Leaching of palladium from spent Pd/Al2O3 catalysts by coupled ultrasound-microwave technique. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 346, 127492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S.; Ting, Y.-P. Ultrasound-assisted nitric acid pretreatment for enhanced biorecovery of platinum group metals from spent automotive catalyst. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooren, J.; Atia, T.A. Combined microwave assisted roasting and leaching to recover platinum group metals from spent automotive catalysts. Miner. Eng. 2020, 146, 106153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xiong, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, F.; Yang, Y.; Hua, Z.; Tian, Y.; You, J.; Zhao, Z. Recycling of copper telluride from copper anode slime processing: Toward efficient recovery of tellurium and copper. Hydrometallurgy 2020, 196, 105436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wu, Y.; Tang, A.; Pan, D.A.; Li, B. Recovery of scattered and precious metals from copper anode slime by hydrometallurgy: A review. Hydrometallurgy 2020, 197, 105460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Dai, P.; Wang, J.; Guo, L.; Guo, Z. An environmentally-friendly method to recover silver, copper and lead from copper anode slime by carbothermal reduction and super-gravity. Miner. Eng. 2022, 180, 107515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-C.; Pan, J.; Zhu, D.-Q.; Guo, Z.-Q.; Li, X.-M. Pyrometallurgical recycling of stainless steel pickling sludge: A review. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2019, 26, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Liu, Z.; Chu, M.; Yan, R.; Li, F.; Tang, J.; Feng, J. Detoxification and comprehensive recovery of stainless steel dust and chromium containing slag: Synergistic reduction mechanism and process parameter optimization. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 164, 678–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-Z.; Du, H.; Olayiwola, A.; Liu, B.; Gao, F.; Jia, M.-L.; Wang, M.-H.; Gao, M.-L.; Wang, X.-D.; Wang, S.-N. Recent advances in the recovery of transition metals from spent hydrodesulfurization catalysts. Tungsten 2021, 3, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Li, J.; Xue, D.; Yang, T.; Wang, G.; Peng, C. Facile molybdenum and aluminum recovery from spent hydrogenation catalyst. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 69, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Gong, M.; Jiao, N.; Zhang, T.; Wang, H. Review on the poisoning behavior of typical metals on cracking catalysts for chemicals production from petroleum and anti-poisoning strategies. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2024, 685, 119897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, P.; Bao, F.; Xu, J.; Wang, D.; Lou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X. Double-stable Ce-based oxide: Capturing atomic precious metals via Ostwald ripening for multicomponent three-way catalysts construction. Mol. Catal. 2024, 554, 113808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Bae, W.B.; Byun, S.W.; Kim, Y.J.; Yoon, D.Y.; Jung, C.; Kim, C.H.; Kang, D.; Hazlett, M.J.; Kang, S.B. Pt substitution in Pd/Rh three-way catalyst for improved emission control. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 40, 1606–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, Y.; Li, F.; Chang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, D.; Yang, D.; Li, K.; Wang, H. Thermal deactivation mechanism of the commercial Pt/Pd/Rh/CeO2-ZrO2/Al2O3 catalysts aged under different conditions for the aftertreatment of CNG-fueled vehicle exhaust. Fuel 2023, 344, 128009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A, S.; Tu, G.; Sun, S.; Yan, Y.; Xiao, F.; Shi, R.; Sui, C.; Yu, K. Efficient Resource Utilization and Environmentally Safe Recovery of Platinum Group Metals from Spent Automotive Catalysts via Copper Smelting. Separations 2025, 12, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, A.B.C.; Parhi, P.K.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kang, H.N.; Jyothi, R.K. Environmentally friendly approach to recover vanadium and tungsten from spent SCR catalyst leach liquors using Aliquat 336. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 19736–19746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Ma, W.; Ren, Y.; Chen, Q.; Huan, Z. Environmentally friendly approach for sustainable recycling of spent SCR catalysts and Al alloy scrap to prepare TiAl3 and low-Fe Al alloys. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 6241–6254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Ma, W.; Lei, Y. Preparation of low-oxygen Ti–Al alloy by sustainable recovery of spent SCR catalyst. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 343, 127060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A, S.; Sun, S.; Tu, G.; Fu, Y.; Liu, R.; Guo, L.; Sui, C.; Yu, K.; Xiao, F. Efficient Recovery of Platinum Group Metals from Spent Automotive Catalysts Using Iron Smelting Method by Optimizing Slag Composition at Low Temperature. JOM 2024, 76, 5944–5957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocky, M.M.H.; Rahman, I.M.M.; Endo, M.; Hasegawa, H. Comprehensive insights into aqua regia-based hybrid methods for efficient recovery of precious metals from secondary raw materials. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukurugya, F.; Wouters, W.; Spooren, J. Microwave-assisted chloride leaching for efficient recovery of platinum group metals from spent automotive catalysts: An approach for chemical reagent reduction. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2025, 24, 100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liapun, V.; Motola, M. Current overview and future perspective in fungal biorecovery of metals from secondary sources. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 332, 117345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Song, Q.; Xu, Z. Mechanism of PGMs capture from spent automobile catalyst by copper from waste printed circuit boards with simultaneous pollutants transformation. Waste Manag. 2024, 186, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidunchi, I.; Kulikov, M.; Safarov, R.; Kopishev, E. Extraction of platinum group metals from catalytic converters. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Qu, Z. Insight into Pyrometallurgical Recovery of Platinum Group Metals from Spent Industrial Catalyst: Co-disposal of Industrial Wastes. ACS EST Eng. 2023, 3, 1532–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, T.; Yamaguchi, K. Effects of SiO2 and CaO on Distributions of Platinum Group Metals Between Cu–CuO0.5 and Pb–PbO-Based Slags at 1523 K. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2023, 54, 2360–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yang, K.; Liu, C.; Tu, G.; Xiao, F. Recovery of nickel and preparation of ferronickel alloy from spent petroleum catalyst via cooperative smelting–vitrification process with coal fly ash. Environ. Technol. 2024, 45, 2108–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Song, H.; Zheng, C.; Lin, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Gao, X. Highly efficient recovery of molybdenum from spent catalyst by an optimized process. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2020, 70, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Peng, Z.; Li, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ye, L.; Wang, L.; Rao, M.; Li, G.; Jiang, T. Recovery of platinum-group metals from spent catalysts by microwave smelting. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Shen, C.; Wei, L. Efficient recovery of tungsten from copper tailings using sodium carbonate synergistic pyrometallurgical smelting. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilankoon, I.M.S.K.; Dilshan, R.A.D.P.; Dushyantha, N. Co-processing of e-waste with natural resources and their products to diversify critical metal supply chains. Miner. Eng. 2024, 211, 108706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.-W.; Xi, X.-L.; Chen, J.-P.; Guo, F.; Yang, Z.-J.; Nie, Z.-R. Comprehensive recovery of W, V, and Ti from spent selective reduction catalysts. Rare Met. 2023, 42, 3518–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, D.; Rao, S.; Duan, L.; Shao, C.; Tu, X.; Ma, Z.; Cao, H.; Liu, Z. Selective leaching of lithium from spent lithium-ion batteries using sulfuric acid and oxalic acid. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2024, 31, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, C.; Shi, X.; Li, X.; Wei, C.; Li, M.; Deng, Z. Selective separation of zinc and iron/carbon from blast furnace dust via a hydrometallurgical cooperative leaching method. Waste Manag. 2022, 139, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, R.; Dinkar, O.S.; Kumari, A.; Gupta, R.; Jha, M.K.; Pathak, D.D. Hydrometallurgical processing of waste integrated circuits (ICs) to recover Ag and generate mix concentrate of Au, Pd and Pt. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 93, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzilyberis, K.; Tsakanika, L.-A.; Lymperopoulou, T.; Georgiou, P.; Kiskira, K.; Tsopelas, F.; Ochsenkühn, K.-M.; Ochsenkühn-Petropoulou, M. Design of an advanced hydrometallurgy process for the intensified and optimized industrial recovery of scandium from bauxite residue. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process Intensif. 2020, 155, 108015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Yang, Y.; He, L.; Li, H.; Meng, Z.; Zheng, G.; Li, F.; Su, X.; Xi, B.; Li, Z. Novel Synergistic Process of Impurities Extraction and Phophogypsum Crystallization Control in Wet-Process Phosphoric Acid. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 28122–28132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X.; He, C.; Yang, C.; He, J.; He, R.; Zhang, X.; He, H. Industrial-scale process design for hazardous waste valorization: Synergistic cadmium and zinc recovery via closed-loop hydrometallurgy. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2025, 223, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, A.; Borra, V.L.; Saida, S.; Venkatesan, P.; Önal, M.A.R.; Borra, C.R. Synergistic hydrometallurgical recycling of Li-ion battery cathode active material, anode copper and waste SmCo magnets. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 43, e01284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, J.; White, R.; Murphy, R.; Sadhukhan, J. Aligning platinum recycling with hydrogen economy growth: A comparative LCA of hydrometallurgical and pyrometallurgical methods. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 14577–14588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Gómez, D.C.; Pérez-Moreno, S.M.; Gázquez, M.J.; Guerrero, J.L.; Ruiz-Oria, I.; Ríos, G.; Bolívar, J.P. Arsenic removal procedure for the electrolyte from a hydro-pyrometallurgical complex. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.J.; Seo, S.; Lee, S.I.; Kim, D.W.; Kim, M.J. A study on pyro-hydrometallurgical process for selective recovery of Pb, Sn and Sb from lead dross. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 126071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, M.L.; Slobozeanu, A.E.; Larosa, C.; Paneva, D.; Yakoumis, I.; Cherkezova-Zheleva, Z. Platinum Group Metals: Green Recovery from Spent Auto-Catalysts and Reuse in New Catalysts—A Review. Crystals 2023, 13, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, F.; Tian, Y.; Hu, Y.; Ren, Y.; Cheng, Z. Efficient enrichment of platinum group metals from spent automotive catalyst via copper matte capture followed by roasting and leaching. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 377, 134424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanizadeh, A.; Rashchi, F.; Vahidi, E. Appraising the environmental footprints of spent Li-ion batteries recycling via a pyro/hydrometallurgy hybrid approach. Miner. Eng. 2025, 231, 109466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Haleem, N.; Jamal, Y.; Khan, S.J.; Yang, X. Recovery of lithium and cobalt from used lithium-ion cell phone batteries through a pyro-hydrometallurgical hybrid extraction process and chemical precipitation. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2025, 27, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Jin, X.; Zhang, X.; Duan, X.; Zhang, P.; Teng, L.; Liu, Q.; Liu, W. Combined pyro-hydrometallurgical technology for recovering valuable metal elements from spent lithium-ion batteries: A review of recent developments. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 6561–6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, F.; Qu, G.; Zhang, T.; He, M. Recycling and reutilization of smelting dust as a secondary resource: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 347, 119228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Xu, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, T. Valuable metals recovery and hazardous waste elimination from copper smelting dusts: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2026, 380, 135386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarsan, S.; Anandkumar, M.; Trofimov, E.A. Survey of diverse hydrometallurgy techniques for recovering and extracting valuable metals from PCB waste: An overview. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 1263–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.; Lin, C.S.K.; Hui, D.C.W.; McKay, G. Waste Printed Circuit Board (PCB) Recycling Techniques. Top. Curr. Chem. 2017, 375, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazari, J.; Hossain, M.Z.; Charpentier, P. A review on metal extraction from waste printed circuit boards (wPCBs). J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 12257–12284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Jin, C.; He, W.; Li, G.; Zhu, H.; Huang, J. A review on management of waste three-way catalysts and strategies for recovery of platinum group metals from them. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 305, 114383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Peng, Z.; Tian, R.; Ye, L.; Zhang, J.; Rao, M.; Li, G. Recycling of platinum-group metals from spent automotive catalysts by smelting. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaridi, O.; Platzer, S.; Nischkauer, W.; Betanzos, J.H.; Iturbe, A.U.; Del Rio Gaztelurrutia, C.; Sanchez-Cupido, L.; Siriwardana, A.; Schnürch, M.; Limbeck, A.; et al. Benign recovery of platinum group metals from spent automotive catalysts using choline-based deep eutectic solvents. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2022, 15, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]