Abstract

Weathering steel (WS), a class of low-alloy steel, which often outperforms traditional carbon steels in bridge applications, develops a stable and adherent patina that enhances resistance to atmospheric corrosion. The patinas develop through complex electrochemical and physicochemical reactions between steel alloying elements and environmental constituents such as pollutants, oxygen, moisture, chlorides, and sulfur compounds. However, real-life field exposure tests to evaluate the performance of weathering steel in rural, urban, industrial, and marine environments are costly, time-consuming, and inconsistent, prompting the need for accelerated laboratory-based corrosion tests. This paper compiles and thoroughly examines the effectiveness of widely used accelerated corrosion testing techniques, such as ISO 16539 (Synthetic Ocean Water), Cebelcor, Prohesion (ASTM G85), Salt Spray (ISO 9227), Kesternich, and others, in simulating the weathering behavior of weathering steel. Findings show that some accelerated cyclic tests can partially replicate protective patina formation in polluted or sulfate-rich environments, whereas others, such as continuous salt spray, tend to overestimate corrosion due to the absence of key environmental factors such as wet/dry cycles, microbial activity, UV radiation, and wind-driven rain. Existing tests do not adequately replicate real-world steel–environment interactions. This review proposes a multidisciplinary approach combining localized wet/dry cycles, advanced environmental chambers, and microstructural and oxide layer analysis with AI (artificial intelligence)/ML (machine learning) for predictive models to improve test relevance and long-term performance forecasting of weathering steels.

1. Introduction

Weathering steel, also known as atmospheric corrosion-resistant steel or Corten steel, is characterized by its carefully balanced chemical composition, containing a low percentage of carbon (0.12–0.19%) and a higher concentration of other alloying elements including copper (0.25–0.55%), chromium (0.30–1.25%), nickel (up to 0.65%), phosphorous (0.07–0.15%), and silicon (0.25–0.75%) [1]. Upon atmospheric exposure, the alloying elements promote the formation of a dense, stable, and adherent oxide layer on the surface of steel, commonly known as patina [2,3]. The protective patina layer blocks the penetration of moisture, oxygen, and airborne pollutants, thereby increasing the resistance of weathering steel to atmospheric corrosion and eliminating the need of painting and surface coatings [4,5,6]. In contrast, the conventional carbon steel used in civil engineering structures not only needs anti-corrosion coatings but also maintenance throughout the structure’s entire life cycle. Weathering steel contributes to improved sustainability by reducing maintenance requirements. Due to its self-healing properties, it minimizes the environmental impact (carbon footprint) associated with the conventional surface protection systems, thus making weathering steel a cost-efficient (eliminates the need of maintenance), time-efficient (speeds up the construction), and more environmentally friendly alternative for bridge construction. In addition, the aesthetically appealing appearance and unique coloration of a well-developed patina layer has also led to incorporation of weathering steel in civil engineering applications such as buildings, bridges, non-structural elements (facades, decorative elements), and installations at archaeological sites (sculptures) [7,8,9,10].

The successful application of weathering steel depends on the proper formation and stabilization of its protective patina. Patina development is highly sensitive to environmental conditions including the ratio and frequency of wet/dry cycles, ambient humidity, temperature variations, and the concentration of atmospheric pollutants such as chlorides, sulfates, nitrates, ozone, and particulate matter. In addition, other factors such as surface orientation, exposure or sheltering, and the presence of surrounding vegetation further influence the kinetics and quality of patina formation. Atmospheric corrosivity is classified in the EN ISO 9223 standard into five grades: C1 (very low) to C5 (very high), with CX denoting exceptionally corrosive conditions [11]. Weathering steels perform effectively in low–moderate corrosivity environments (C1–C3) due to stable patina formation. On the other hand, in aggressive environments (C4–CX), elevated pollutant levels and increased chloride deposition due to marine exposure or the excessive use of de-icing salts hinders patina stability, thereby limiting the suitability of weathering steel in such conditions. As a result, coastal or marine regions and areas with high de-icing in Europe may exhibit higher atmospheric corrosivity, while most inland areas of Europe generally fall within the lower to moderate corrosivity range (C2–C3). The Swedish Road Administration, Trafikverket, allows the use of weathering steel under EN ISO 9223 and other specific conditions [12,13]. In C4 and C5, frequent de-icing and salt spray accelerate chloride deposition and destabilize the patina layer, thereby limiting the usage of weathering steel for bridge applications [14,15].

Evaluating the performance of weathering steel in various environments is essential to ensure structural integrity, durability, and sustainability. The performance evaluation of protective patina in weathering steel is carried out by field exposure tests or accelerated tests. Protective patina, a key to corrosion resistance, depends on environmental and exposure conditions. During the initial years of exposure, weathering steel corrodes at a rate similar to that of conventional carbon steel. The corrosion rate drops drastically once the patina stabilizes, which usually occurs within 2 to 6/8 years, depending on the severity of the environment [16,17,18,19]. After patina formation, weathering steel corrodes 4 to 8 times slower than conventional steel with a steady-state corrosion rate, to as low as 0.005 mm/year in medium-corrosivity (C3) conditions [13]. However, micro and macro environmental factors might hinder patina formation, leading to higher corrosion rates similar to those of conventional carbon steel. To evaluate the environmental factors affecting protective patina formation under different atmospheric conditions, field exposures tests are usually conducted. However, these tests are time-consuming and have limitations in reproducibility and accuracy. Therefore, accelerated corrosion tests are sometimes employed, as they provide a controlled, reproducible, and cost- and time-effective means of evaluating weathering steel performance. The accelerated corrosion test simulates multiple environmental stressors within a controlled chamber, enabling quick evaluation and ranking of steel grades, assessment of potential environments, and determination of effective corrosion control strategies.

This paper presents a state-of-the art review of the application of the accelerated corrosion tests for evaluating the long-term performance of weathering steel. This study critically evaluates the currently employed accelerated corrosion tests, emphasizing their predictive accuracy of long-term corrosion behavior across diverse atmospheric conditions and identifying key limitations in reproducing field-exposed goethite-rich patinas. This paper also focuses on the future recommendations needed for establishing more efficient and reliable accelerated tests. The key research questions discussed in this paper are the following: (1) How do different accelerated corrosion tests perform, and what are their advantages and shortcomings? (2) What environmental factors play the most critical role for accurate patina formation, and thus need to be included in accelerated environmental testing? (3) How well do accelerated tests replicate natural corrosion mechanisms in different environments? (4) What are the challenges in developing an efficient accelerated corrosion test? (5) Finally, what recommendations can be made to improve the correlation between the highly complex real-world environments and accelerated corrosion tests, and thus provide a more reliable and accurate basis for accelerated weathering tests? The primary objective of this paper is to establish a thorough foundation for future research focused on developing an effective accelerated corrosion testing method for weathering steel. By improving the correlation between laboratory simulation and actual field conditions, this review can help narrow the gap, allow more accurate service life predictions, and aid the design of durable, low-maintenance steel structures.

2. Development of Weathering Steel

The aim of weathering steel, which was developed in 1920, was to improve corrosion resistance of steel without having to resort to protective coating or maintenance. Initially, copper-containing steels with varying concentrations of Cu demonstrated better corrosion resistance than ordinary carbon steels, leading to their early application in railway vehicle components [18]. The evolution of the material culminated in 1932 with the development of Cor-Ten steel, which incorporated several alloying elements to enhance both mechanical properties and atmospheric corrosion resistance [20,21]. Cor-Ten steel soon emerged as a better alternative, offering improved weldability, formability, and high ductility while providing an atmospheric service life twice that of copper steel (containing a higher concentration of Cu element ≥ 0.20) and five times that of plain carbon steel [22]. Table 1 compares the elemental composition of all steels including weathering steel. Copper steel offers better corrosion resistance than carbon steel; however, the blend of different alloys in weathering steel not only enhances its performance but also significantly decreases the corrosion rate with exposure time. During the 1940s–1950s, the adoption of weathering steel expanded across various industries due to its excellent corrosion resistance, minimal maintenance requirements, and weight reduction benefits, particularly in railway applications such as freight wagon bodies, locomotives, and structural components including panels, frames, and body members [22,23].

Table 1.

Chemical composition.

During the 1950s, a paradigm shifts towards scientific understanding paved the way for more systematic investigations of corrosion mechanisms, enabling the development of high-strength, low-alloy steels optimized for strength, ductility, and weldability [22]. The 1960s largely established the fundamental knowledge of protective patina formation through detailed investigations into the development of the oxide layer, with more focus being paid to the role of different alloying elements such as chromium, silicon, and copper in improving the resistance of the material to atmospheric corrosion. In the 1970s, composition optimization was undertaken, with systematic studies demonstrating that the strategic addition of Cu, Cr, silicon, and molybdenum significantly reduced the atmospheric corrosion rate, while manganese increased the pitting susceptibility [22,24,25,26]. In the 1980s–1990s, the construction of steel bridges increased worldwide, and advanced analytical techniques such as infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and electron microscopy were employed to identify multi-layered patina structures comprised of goethite, lepidocrocite, and magnetite phases [27,28,29,30]. The 2000s introduced comprehensive design, construction, and maintenance protocols specifically for using weathering steel bridges along with identification of the environmental constraints such as the marine exposure or contamination with road salt [31,32,33]. From the 2010s to 2025, research has focused on quantitative patina evaluation using the Protective Ability Index (PAI) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), developing probabilistic corrosion-fatigue models, and incorporating XRD, SEM, and XPS techniques for understanding oxide layer evolution and corrosion–fatigue interactions under the most severe environments.

3. Chemical Composition of Weathering Steel

US Cor-Ten steels are produced in two major specifications, which differ mainly by phosphorus content and application uses. Cor-Ten A has higher phosphorus levels, from 0.07 to 0.15 wt.%, making it more resistant to atmospheric corrosion through stabilization of the protective patina layer. On the other hand, Cor-Ten B contains lower levels of phosphorus, around 0.035 wt.%, and is intended for structural uses where toughness and weldability matter more than efficiency in forming a patina. Chemical compositions for both Cor-Ten A and Cor-Ten B are given in Table 1.

High-performance weathering steel is made from low-carbon steel (less than 0.2 wt.%) and total alloying elements (Cu, Cr, Ni, P, Si, and Mn) amounting to no more than 3–5% by weight [16,17,18,19,21,23]. The most likely composition for early weathering steels was based on a Fe-Cu-Cr-P system, which later was improved with the addition of nickel to enhance corrosion resistance, particularly in the marine environment. Each alloying element serves a specific function: copper promotes the formation of a protective oxide film, chromium enhances the scaling resistance at high temperatures, nickel reduces hot embrittlement, and phosphorus acts as both a strengthening agent and patina stabilizer [16,17]. Recent advancements in weathering steel have focused on improving corrosion resistance, accelerating protective patina formation, and extending the potential use of weathering steel, especially in marine environments, with the addition of new alloying elements. In Europe, weathering steel has evolved from traditional Cor-Ten grade to more advanced weathering steel under EN 10025-5 [34], offering higher strength, improved corrosion resistance, and better weldability. Steel makers like SSAB and ArcelorMittal have revolutionized weathering steel production by developing grades capable of withstanding high temperatures, sulfur-rich atmospheres, and saline conditions (marine and offshore environments).

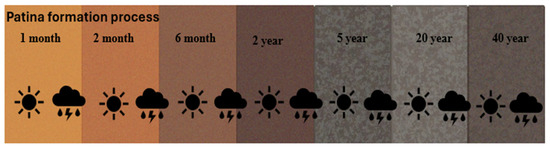

4. Mechanism of Patina Formation

During the early weathering period, usually in the first year, weathering steel corrosion is equivalent to that of carbon steel, with a comparable corrosion rate. But under prolonged airborne (atmospheric) exposure, weathering steel becomes coated with a stable, adherent patina composed mostly of iron oxyhydroxides, which decreases the corrosion rate to as low as 0.005 mm/year in medium-corrosivity (C3) conditions [13]. The formation of the protective patina is slow and needs long-term exposure to atmospheric environment with many cycles of wetting and drying. The whole process of developing a patina normally takes 2–6 years under favorable atmospheric conditions. The transformation goes through several stages of color from fresh orange, brown, to light-brown, and eventually dark brown coloring. Initially, the rust layer appears as a light-brown or pale-yellow film, primarily composed of γ-FeOOH (lepidocrocite), which is indicative of an early-stage, less protective corrosion product. As exposure progresses, the patina transforms through intermediate stages characterized by a bright yellow to reddish-brown coloration, eventually stabilizing into a more uniform reddish-brown or brownish-red hue as shown in Figure 1 [13]. This mature coloration is more related to the prevalence of α-FeOOH (goethite), a denser, compact, and adherent phase, which confers higher corrosion resistance. The evolution of color typically shows a transition from bright orange (early corrosion) to brownish rust (transition phases), and finally to dark brown (stable protective layer), which is correlated with the change in oxide composition, microstructure, and compactness. The color transitions are affected by environmental factors like atmospheric aggressiveness, exposure time, the position of the sample, and the microclimate, which can modify the kinetic rate and nature of patina development. The patina layer in weathering steel serves as a passive shield, slowing additional oxidation and increasing the longevity of the material. The patina layer consists of a mixture of various crystalline and amorphous phases, consisting mainly of iron oxide phases: hematite (α-Fe2O3), maghemite (γ-Fe2O3), magnetite (Fe3O4), ferrihydrite (5 Fe2O3-9H2O), and the critical oxyhydroxide phases [13,16,17,18]. Goethite (α-FeOOH) is the anhydrous iron oxide corrosion product having the highest stability, and it is the dominant protective constituent in fully developed patinas. Lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH) serves as an electrochemically active phase which is converted to the stable goethite upon wet/dry cycling, and it develops during the initial stage. Akaganeite (β-FeOOH) occurs in the chloride-rich environment and is able to destroy the barrier effect of the patina in high-content phases [18].

Figure 1.

Patina color formation with consistent wetting and drying.

The ability of a patina to effectively protect is dependent on a number of inter-related factors, including its composition, the environmental conditions (e.g., humidity, pollutant, wet/dry cycling), and design features including orientation (w.r.t solar exposure, wind, and rainfall), drainage efficiency, and avoidance of local crevices or moisture reservoir geometries. Under unsuitable circumstances like permanent moisture, insufficient drainage, or high chloride deposit rates over 0.05 mg/100 cm2/day, e.g., in a marine environment, the stabilization of the patina may be delayed and localized and/or pitting corrosion may occur. The high-performance weathering steels alloyed with 3 wt.% nickel have shown significantly improved corrosion resistance and are expected to exhibit an average material thickness loss of about 0.17 mm over a design life of 100 years [35]. Apart from this, numerous high-performance weathering steels were designed to meet specific environmental challenges and different structural requirements by combining traditional alloying knowledge with advanced metallurgical techniques. To date, though, predicting the long-term behavior of weathering steel is still difficult due to the lack of a deep comprehension of the kinetics of patina evolution and site-specific meteorological parameters. Current research is actively exploring the use of predictive models that encompass multi-factorial environmental exposure data, regional variations in climate, and seasonal effects to improve predictions of service life [36]. Such models would be extremely beneficial in risk-based assessments, optimization of the use of material, and reliable application of weathering steel in vital infrastructure, especially in service environments in which little or no maintenance can be provided and design lives of 100–120 years can be assumed.

To facilitate the good performance of weathering steel in various civil engineering applications, it is important to study the effects of individual environmental- and material-related parameters on the formation, composition, and protective nature of the protective patina. Some factors, such as wet/dry cycles, exposure to atmospheric pollutants, alloy composition, and microclimatic complement each other and are found to be the main factors controlling the long-term corrosion behavior of WS in various realistic environments. Secondary but important factors that also affect the development of protective patina on weathering steel include wind-driven rains, acid rains, nitrogen oxides, UV radiation, and particulate matter. Research on the influence of these factors on patina development and corrosion rates is very limited. However, these factors are important as they demonstrate complex synergistic interactions that significantly affect the formation and protective capacity of the corrosion product layer. Various studies indicate that these factors operate through distinct, yet inter-related mechanisms that collectively determine patina quality and the long-term performance of steel [16,17,18,19]. The main and secondary factors are described as follows.

4.1. Material Composition and Microstructural Factors (Alloying Element Composition)

The development and strengthening of a protective patina layer on weathering steel is primarily dependent on the synergistic effect of alloying elements copper (Cu), chromium (Cr), nickel (Ni), phosphorus (P), silicon (Si), and molybdenum (Mo). These elements in conjugation with iron oxides develop an adherent and protective layer mainly composed of goethite (α-FeOOH) that acts as a barrier against corrosion. Copper (0.25–0.55 wt.%) and chromium (0.4–1.25 wt.%) are pivotal for patina formation and stabilization. During the drying phase, copper ions catalyze the reduction of lepidocrocite(γ-FeOOH) to goethite (α-FeOOH), enhancing patina adhesion and stabilization. Chromium ions reduce defect density by substituting iron, contributing to grain refinement and phase stability, and accelerating the transformation of lepidocrocite to goethite. Nickel (0.25–0.65%) enhances corrosion resistance in industrial and marine environments. In industrial environments Ni also improves the resistance to acid rain by complexing with sulfate compounds and in marine environments it helps to suppress the formation of non-protective phase akageneite (β-FeOOH). Phosphorous (0.07–0.15 wt.%) strengthens the steel matrix. Especially when combined with Cu, it enhances the compact phosphate containing rust layers which are denser and with better adhesion. The excess phosphate promotes hydrogen embrittlement whereas an insufficient level reduces the nucleation sites of goethite. The presence of silicon (0.25–0.75%) aids patina formation and enhances the adherence of the oxide layer. In environments with harsher exposure to chloride levels or de-icing salt or salt splashes, molybdenum (up to 0.30%) improves resistance against localized corrosion and pitting corrosion. Manganese (0.20–1.25%) is added to improve structural integrity and toughness. Together, the alloying elements affect the microstructure of the patina, the composition of the phases present, and the kinetics of its transformation, all of which are important to long-term corrosion resistance in service in various exposed environments. As a result, it is critical to optimize the composition of the material in order to apply WS successfully to infrastructure with life expectancy and maintenance requirements [18,34,37,38,39].

4.2. Wet/Dry Cycles

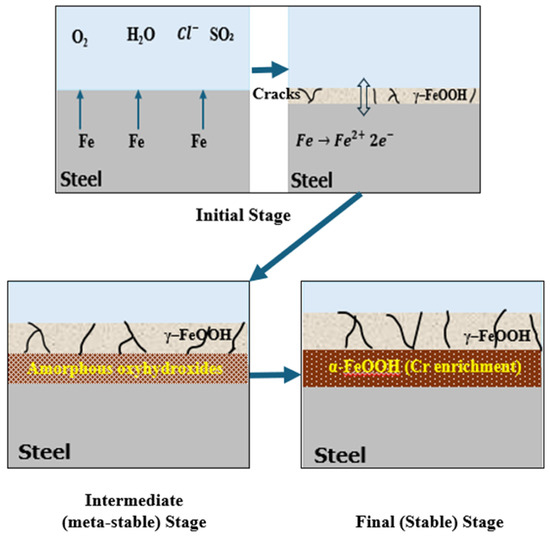

The primary mechanism governing the formation of protective patina on weathering steel is attributed to environmental cyclic exposure, especially the wet/dry cycles. These cycles are necessary to initiate and regulate the electrochemical and physiochemical processes responsible for the development of a compact and adherent rust layer with corrosion-inhibitive features. During the wet phase, rain or precipitation serves as a rinsing agent due to its capacity to flush away loosely adherent corrosion products and environmental contaminants from the steel surface. Simultaneously it dissolves the soluble ions (such as chlorides, sulfates, and nitrates) from atmospheric deposits in conjugation with the alloying elements (as Fe2+, Cu2+, and Cr3+) from the steel matrix, resulting in the formation of an acidic electrolyte film that induces corrosion [16,40,41]. As the surface evolves toward the “dry” phase, the concentration of the dissolved ions at the surface increases locally and offers favorable conditions for the nucleation and growth of thermodynamic stable corrosion products, the greater proportion of which consists of goethite (α-FeOOH) and secondarily akageneite (β-FeOOH) in case of chloride environment. Of these, goethite is the most favorable product because it is highly nonporous, adherent, and has very low ionic diffusivity, all of which promotes the formation of protective patina, as shown in Figure 2. Thus, the formation of the goethite-rich layer is critical for long-term corrosion protection. In natural atmospheric exposure, stabilization of the patina and preferred formation of goethite generally occurs after 2 to 6 years, depending on the regional climate and site-specific environmental conditions [42,43]. In contrast, laboratory-controlled experiments have shown that this timeline can be much shorter depending on the imposed wet/dry cycling protocols, test atmosphere composition, and the existence of catalytic ions. As shown in Figure 2, the formation timeline of the patina consists of different stages. In the initial stage (days to weeks), γ-FeOOH and ferrihydrite begin forming on the steel surface. During the intermediate stage (months) wet/dry cycles promote the transformation of γ-FeOOH into α-FeOOH, while magnetite may appear under oxygen-limited conditions. In the final stage (1–3 years), shows development of a mature patina, dominated by fine-grained α-FeOOH with minor amounts of hematite and maghemite.

Figure 2.

Stable and protective patina formation on weathering steel.

Seasonal variation in regions that cause well-defined changes in wet and dry periods lead to faster, more homogeneous development of patina. However dry or continuously (RH > 80%) humid conditions inhibit the natural drying between wetting periods. This long period of a wet surface may prevent the transformation of intermediate stages of rust, such as lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH), into stable goethite. In subtropical and moist climates, these prolonged wet periods inhibit the ion concentration during drying and led to growth of porous, weakly adherent lepidocrocite layers that are less protective and may corrode further. Thus, the frequency, duration, and level of wet/dry cycles have pronounced effects on the morphology, mineralogy, and functional efficiency of the patina. Optimizing environmental exposure conditions to induce regular drying cycles is of great importance when it comes to improving the applicability of weathering steel in actual infrastructure.

4.3. Atmospheric Pollutants (Chloride and Sulfur Compound Exposure)

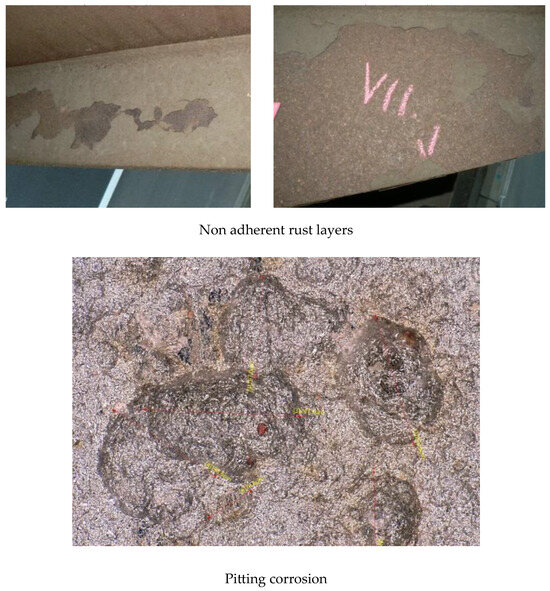

The formation, composition, and stability of patina on weathering steel is strongly affected by atmospheric pollutants, especially chloride and sulfur compounds. At deposition rates as low as 5–10 mg/m2/day, chloride ions are found to interfere with the formation of the protective oxide film. Chlorides encourage the generation of very soluble and unstable substances such as , which make it difficult to form a uniform and adherent patina. In environments, especially in marine and coastal regions, the major product is akaganeite (β-FeOOH). During this stage tunnel-like structures are formed, effectively trapping chloride ions to create a self-maintaining corrosion process and resulting in the formation of porous, loosely adhering rust products, as shown in Figure 3 [44,45].

Figure 3.

Chloride deposition effects (Reprinted from Ref. [46]).

Structures located within distances of 1 km from the coast are especially vulnerable, with corrosion rates up to five to ten times those inland. The high corrosion was reported to be associated mainly to pitting attack induced by breakdown of the passive film due to chloride induction [46,47,48]. In addition, chloride ions are hygroscopic, leading to persistence of moisture on the steel surface (longer time of wetness), thereby promoting further corrosion [49]. In addition to marine exposure, also land structures in Europe are exposed to chloride deposition from anthropogenic sources like de-icing salts during winter [26,42]. Salt spray, minimal natural rinse by rain, and poor drying also aggravate local attack, especially in sheltered or poorly ventilated structural shapes [42,46].

On the other hand, sulfur dioxide (SO2) and its oxidation products (e.g., sulfates) have a bimodal effect. At low to moderate atmospheric concentrations, SO2 may actually promote patina formation due to a decrease in electrolyte pH and oxidation. This results in the generation of sulfate–goethite complex constituents which promote higher patina density, lower porosity, and greater adhesion to the steel support. However, at high concentrations, sulfur dioxide results in acidic corrosion (acid rain effect), leading to increased metal loss, accumulating surface moisture, and inhibiting the development of the protective patina layer [50].

Sulfur dioxide concentrations in Sweden are generally low in comparison to central Europe and some areas of Asia. Thus, SO2-induced corrosion is not considered a major problem in the Swedish atmosphere. However, even low levels combined with other adverse factors like high humidity and low temperatures can retard the formation of the patina and decrease its protective qualities with passage of time. In addition, the extended time of wetness (TOW) typical in Nordic climates, especially within sheltered geometrical details like box girders, stiffener pockets, and overlapping joints, significantly disrupts the electrochemical gradient necessary for the maturation of the initial corrosion products. As a result, lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH) often persists, rather than being transformed into protective goethite (α-FeOOH), thereby compromising the compactness, adhesion, and ionic barrier of the patina, and results in the steel being continuously oxidized at rates similar to those of unprotected carbon steel. Beyond these moisture-related challenges, the fundamental durability problem is chloride-induced pitting corrosion owing to the very high deposition of winter road de-icing salts and coastal salt spray. Such chloride deposits inhibit patina stabilization, and often necessitate the use of protective coatings, enhanced drainage design, or increased corrosion allowances in structural elements to achieve service-life objectives. Swedish transport administration allows the use of natural weathered unpainted weathering steel only for traffic classes 3–4 (non-fatigue loaded structures), provided that the environment is well specified, with a minimum of chlorides, optimized drainage, reduced frequency of wetting, and sufficient drying intervals to enable patina maturation within the critical years of exposure. These strict criteria reflect the limited research on fatigue damage in naturally weathered steel [12]. Given these limitations, the authors conclude that more research work is needed to allow the wider use of weathering steel in Sweden, beyond what is currently accepted. More research is required to evaluate the long-term performance and develop design rules for weathering steel specifically for the Swedish climate and environment.

4.4. Geometric and Microclimatic Factors

4.4.1. Drainage Design

The drainage design and geometrical configuration of structures made of weathering steel are two key factors affecting the appearance and uniformity of the rust patina. Inadequate drainage and retention of water in structural features, as shown in Figure 4, such as joints, bolts, crevices, and horizontal surfaces, may obstruct the accumulation and redistribution of corrosion-inhibiting elements that are essential for the formation of a dense, adherent, and goethite-rich patina. On the contrary, such sites promote the development of loosely consolidated and non-protective corrosion products, such as lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH) and akageneite (β-FeOOH), leading to degradation of the patina. Poor drainage leads to longer periods of wetness (time of wetness-TOW), a critical parameter affecting corrosion kinetics as it enables moisture, chlorides, and other contaminants in the atmosphere to accumulate at the critical sites, as shown in Figure 4 [49]. The drainage failure issue is troublesome specifically in colder climates where salt for de-icing is applied. Regional deposition of salt and long-term wetness can result in initiation and progression of pitting corrosion and would eventually cause considerable loss of structural integrity.

Figure 4.

Drainage leakage effects (Reprinted from Ref. [42]).

Engineering practices, such as incorporating inclined surfaces, avoiding details like pockets, cervices, fraying surfaces, and expansion joints, ensuring wide flanges do not extend beyond the box section, removal of vegetation around the bridge, and maintaining wider drainage gaps, have been shown to reduce the variability in corrosion penetration rate by up to 40%, as these measures prevent the accumulation of stagnant moisture films. Also to be avoided are closed box girder designs without proper ventilation and the possibility of inspection and maintenance to avoid salt, moisture, and contaminants built up within, which can create microclimatic conditions unfavorable to the development of the protective patina [42,43,51]. Hence, in terms of both design and maintenance, efficient drainage systems are essential to enable stable patina formation and prolong the lifetime of weathering steel constructions.

4.4.2. Surface Orientation and Inclination

The organization and inclination of weathering steel surfaces have a marked impact on how the patina develops because these factors interact with moisture absorption as well as drainage behaviors. Horizontal or flat surfaces hold water too long, resulting in over wetness, and less than ideal concentrations of alloying elements after drying. The prolonged wetting encourages the development of porous and unstable corrosion products, mainly lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH), which are 40–60% more porous than the stable and protective goethite (α-FeOOH) [16].

Field studies on different bridge structures throughout the world have consistently shown higher mass losses on horizontal surfaces (girder flanges) compared to vertical elements (girders) caused by water retention. It was reported that the thickness of corrosion on horizontal girder surfaces was three times the thickness of the corrosion layer observed on vertically oriented surfaces. The deterioration undermines the long-term serviceability of the structure and diminishes the self-protective characteristics of weathering steel [16,42,46].

The possible susceptible horizontal locations where debris or chlorides may accumulate and water ponding may occur include the top surface of lower flanges, gusset plates for horizontal bracing, bearing and intermediate stiffeners, and interiors of box-type girders. To avoid accumulation of chloride, debris, and water ponding, the steel surfaces should be tilted or sloped to allow efficient water runoff, prevent the accumulation of stagnant moisture, and promote wet/dry cycles. These conditions contribute to the repeated dissolution and reprecipitation of anti-corrosive alloying elements, which promotes the conversion of lepidocrocite to the goethite, which is stable. Consequently, the stabilization of patina on the sloped areas is found to be 30–40% faster than on the horizontal areas and the corrosion kinetics decrease considerably to approximately 0.002–0.004 mm/year after 2–4 years of atmospheric exposure [16,46]. As such, optimizing surface inclination in design enables not only better uniformity and protective efficacy of a patina, but also is a key factor to extend the useful life of weathering steel and enhance the structural safety of infrastructure made using weathering steel.

4.4.3. UV Radiation

Atmospheric corrosion of metals is an electrochemical process in which metals react with surrounding environments to form oxides and oxyhydroxides. During corrosion, iron dissolves anodically, producing Fe2+ ions which undergo hydrolysis and from FeOH+. Under UV illumination, rapid oxidation and precipitation of FeOH+ are promoted by dissolved oxygen and other strong oxidizing species, leading to the formation of early-stage rust phases such as γ-FeOOH.

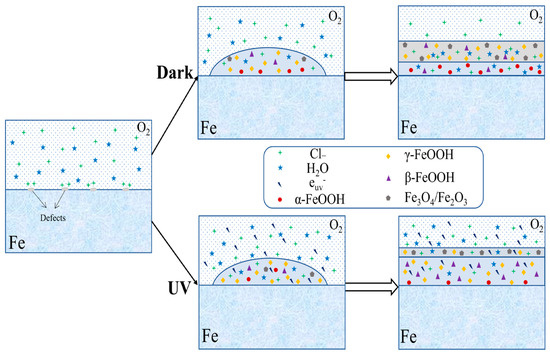

UV radiation induces corrosion via photocatalytic processes, which are attributed to the semiconductor properties of iron oxide corrosion products. UV light is absorbed by iron oxides like Fe2O3, electron–hole pairs (Fe2O3 + hν → e− + h+) are generated, and the photo-generated electrons drive reduction reactions, whereas the holes would enhance anodic dissolution and oxidative processes at the metal–rust interface. Laboratory tests under UV illumination show an increase in corrosion current density of up to approximately 24% as compared with dark conditions, with the effect being more significant during the early stages of patina development [52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. However, changes in corrosion density primarily reflect short-term electrochemical activity and do not directly represent long-term corrosion rates or cumulative material loss. Corrosion products formed in dark and illuminated environments differ in conductivity, which affect their phase composition. The phase variation not only influences the distribution of corrosion-resistant elements but also disturbs the denseness of the rust layer, as shown in Figure 5. The 3%Ni weathering steel exposed to marine environment under UV exposure showed increased conductivity of corrosion products, which in turn improved the compactness of the rust layer [55].

Figure 5.

UV radiation effects (Reprinted from Ref. [55]).

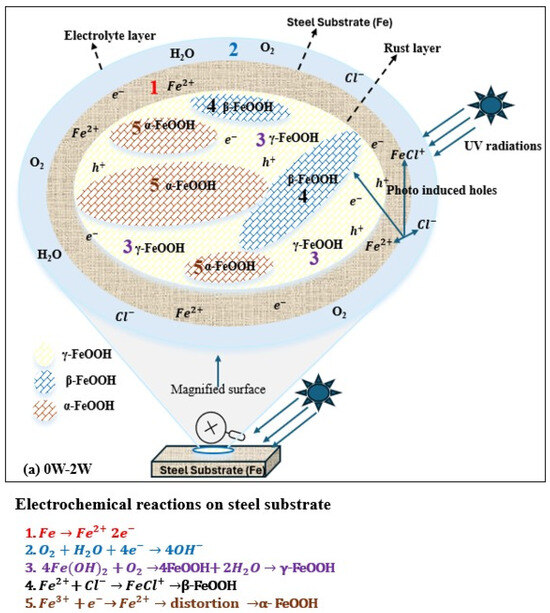

As shown in Figure 6a, during the first week under UV exposure, the corrosion product layer formed on the steel surface is thin. The FeOOH products (both γ-FeOOH and β-FeOOH) formed at this stage behave as an n-type semiconductor when exposed to visible light. Upon light exposure FeOOH generates photo-induced holes with strong oxidizing ability that capture electrons released from iron dissolution, thereby accelerating the anodic dissolution of weathering steel. Under UV illumination, the photo-induced holes also attract chloride ions (Cl−) and promote the adsorption on the FeOOH surface. The adsorbed Cl− reacts with Fe2+ to form FeCl+, promoting the formation of β-FeOOH during 1–2 weeks of UV exposure. Since γ-FeOOH and β-FeOOH are metastable phases, lattice distortions caused by the reduction reactions facilitate their transformation into a more metastable product, α-FeOOH, resulting in a thicker rust layer. As α-FeOOH is an electrically insulating phase, it hinders the movement of photo-induced holes and electrons and reduces the ability of photo-induced holes to capture the electrons from iron dissolution, leading to a decrease in corrosion rate under UV illumination [59].

Figure 6.

Role of UV in atmospheric corrosion. (a) 0W→2W ( from iron dissolution; photo-generated holes from corrosion products). (b). 2W→4W ( from iron dissolution; photo-generated holes from corrosion products.

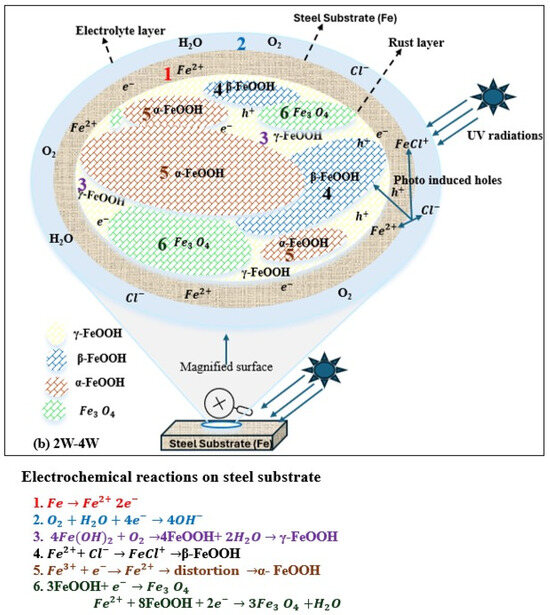

From 2 to 4 weeks of exposure, as shown in Figure 6b, the corrosion layer becomes much thicker, creating a low oxygen environment at the steel–rust interface. Under these conditions, FeOOH acts as an oxidizing agent and participates in cathodic reactions, mainly involving γ-FeOOH and β-FeOOH, leading to the formation of Fe3O4 near the steel surface. Fe3O4 has good electrical conductivity and provides efficient electron transport pathways, shortens the electron transfer distance from the dissolution anodic sites, and significantly increases the corrosion rate under UV illumination [59].

Research has confirmed that introducing UV radiation in combination with wet/dry cycling (UVWD) can increase corrosion significantly, with bridge steels Q345q and Q500q experiencing weight loss rates nearly ten times higher under UVWD than under wet/dry cycling alone (9.55 mg·cm−2 vs. 0.34 mg·cm−2 after 14 days). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) confirms that UVWD exposure results in extremely low impedance values (16–32 Ω·cm2), indicating a complete lack of protective properties, compared to over 1600 Ω·cm2 for well-formed patina. The photocatalytic reactions partially degrade the crystal structure of the protective oxide layer, resulting in a rust layer that is thicker but contains more pores, voids, and cracks, thereby reducing its barrier performance [56]. Qiu et al. studied steel corrosion in a simulated marine environment under visible light. They found that photo-induced electron–holes triggered anodic dissolution, chloride ion adsorption, and the conversion of hematite to magnetite at the corrosion layer interface [54]. On weathering steels, magnetite (Fe3O4) typically forms under relatively low oxygen conditions, while hematite(α-Fe3O4) develops in well-aerated conditions and is generally less protective than magnetite and goethite. Song et al. reported that UV illumination influences NaCl-induced atmospheric corrosion of weathering steel by affecting the atmospheric corrosion rate, corrosion surface morphology, corrosion product formation, and the properties of the resulting rust layer [59].

Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that UV irradiation alone produces negligible corrosion in the absence of moisture cycling, indicating that UV acts primarily as a catalytic or secondary factor rather than a direct driving force for atmospheric corrosion. Moreover, under natural exposure conditions, UV radiation may indirectly reduce corrosion by inhibiting the growth of mass, algae, or biofilms on steel surfaces. Such effects are not captured in accelerated laboratory tests, and are therefore not considered in most corrosion studies, highlighting the need for further investigation, particularly for weathering steels. In addition, studies conducted under real environment conditions that investigate the effect of UV radiation on long-term corrosion behavior of weathering steel remain limited and should be addressed in future research. In marine environments, UV-induced damage is greatest during the initial stages of patina formation and decreases over time as corrosion layers become denser. This is significant because UV light has its strongest influence during the critical early stages when the protective properties of the patina are established [54,55,56,57].

4.4.4. Rain-Driven Winds, Acid Rain, Nitrogen Oxides (NOx), and Particulates

Rain-driven winds, acid rain, nitrogen oxides (NOx), and particulates are all highly influential on the corrosion of weathering steel via a series of complex and inter-related mechanisms that diminish the protective properties of their patina. Wind-driven rain intensifies wetness and ionic salt deposition, especially at the time when wind speed is larger than 5 m/s, due to the actions of breaking waves that create chloride-rich aerosols by mechanisms derived from bubble-bursting mainly in marine environments. Unlike vertical surfaces that are exposed to high salinity for shorter exposure, horizontal surfaces receive five times greater chloride and can develop corrosion layers three times thicker with reduced barrier performance. Patina formation is influenced by the presence of acid rain (low pH spray): sulfuric acid enters through SO2 oxidation (SO2 + H2O + ½O2 → H2SO4), which creates acidified surface electrolytes at the surface interface and hinders precipitation of protective oxides. Under 20 mg/m2·day, weathering steel corrodes at ≤6 µm/year; above that threshold, the corrosion rate increases sharply [40]. In industrial atmospheres, loose non-protective rust layers develop at SO2 levels ≥ 90 mg/m2 day as per European regulations. However, due to stricter environmental regulations, SO2 concentrations have been reduced to 45 μg/m3 [12].

NOx compounds mostly contribute by making acids (NO2 + H2O → HNO3 + H+ + e−) and speeding up the oxidation of SO2. The catalytic effect is strongest when the humidity is low, which makes NOx reactions happen faster. When NO2 and SO2 are together in different amounts of moisture, they have synergistic effects. Dust and other small particles hold moisture and salt on steel surfaces, which keeps the surface wet for longer. This stops the formation of protective oxide layers. Horizontal surfaces in dusty areas often have high levels of aluminum and silicon from aerosol deposition and airborne impurities, which are linked to poor patina development. In industrial areas with a lot of pollution (pollution category P3, SO2 > 200 mg/m2·day), unpainted weathering steel often does not make compact, adherent patina layers. Integration of these environmental factors creates complex multi-pollutant scenarios, where decreasing SO2 and increasing NOx from urbanization has led to new atmospheric chemistry in which pollutant interactions are critically important, with weathering steel requiring alternating wet/dry cycles in relatively clean atmospheres to develop the appropriate protective characteristics [60].

4.4.5. Freeze/Thaw Cycles

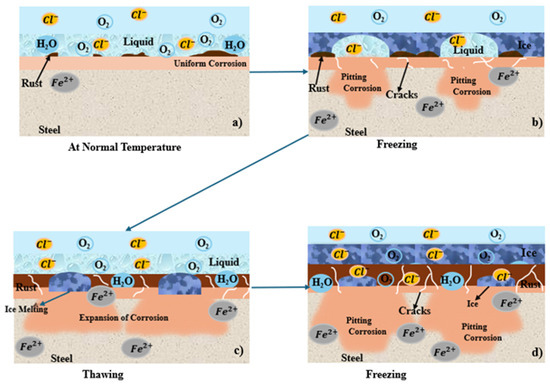

The influence of freeze/thaw cycles on patina formation and corrosion rates of low-alloy weathering steels is an essential but not well-investigated parameter in atmospheric corrosion research. The scientific literature has shown that the increased freeze/thaw cycles caused by climate change will disrupt critical wet/dry cycling mechanisms in weathering steel, thereby preventing the development of protective patina and driving corrosion through a variety of accelerated deterioration mechanisms. Daukšys et al. [61] investigated thermal cycling experiments from +20 °C to −20 °C for 100 cycles on Cor-Ten weathering steel, finding that freeze/thaw exposure along with a 3% NaCl solution produced the highest degree of oxidation product development relative to water or 3% Na2SO4 salt solution. XRD analysis revealed significant changes in phase composition, including lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH), goethite (α-FeOOH), and magnetite. The findings also suggested that "thin films with high concentration of Cl− and SO42− ions are developed on metal surface upon dew droplet condensation under cycling temperature fluctuation conditions”. These results suggested that moisture in the rust layer can serve as a pathway for chloride infiltration during freeze/thaw cycling and alter the critical α/γ oxide ratio responsible for protective function [61]. Figure 7 illustrates the corrosion mechanism of sea water under freeze/thaw cycles. The infiltration of chloride under freeze/thaw cycles and temperature changes make the corrosion layer expand or contract repeatedly, which breaks or peels off the rust layer and exposes the steel surface, leading to localized corrosion [58,62]. Figure 7a shows that, at ambient temperature, uniform corrosion initiates due to active electrochemical reactions. Figure 7b, c shows that, during freezing, the sea water on the steel surface begins to freeze, while the remining unfrozen liquid with highly concentrated chloride ions (Cl-) beneath the ice promote the initiation and growth of corrosion pits. During the subsequent thawing stage, melting restores ion mobility, thereby accelerating corrosion, and corrosion products accumulate to form a rust layer on the steel surface. Figure 7d shows that repeated freeze/thaw cycles induce cracking of the rust layer, resulting in a loose and porous rust layer that no longer acts as an effective barrier against the inflow of chloride ions, ultimately leading to severe localized corrosion.

Figure 7.

(a–d) Freeze/thaw-cycles process.

Zhang et al. studied the impact of freeze/thaw cycles on atmospheric corrosion of low-alloy weathering steels; during freezing, water expands within the pores, which leads to development of cracks in the rust layer during thawing. Rust layers formed under high temperatures and humid environments contain more liquid water and are therefore more susceptible to freeze/thaw cracking, whereas dense rust layers formed under low temperatures and low-humidity environments do not retain any water, thus being more immune to freeze/thaw cycles [63]. Field studies on Q460 and Q690 low-alloy steels in Antarctica revealed that rust layer fractures were increased by thermal cycling to thawing/freezing of ice and snow; freeze/thaw cycles led to mechanical damage pathways, which degrade patina protectiveness [64]. The underlying mechanisms are related to ice build-up stresses in the patina micropores, differential thermal expansion coefficients between oxide layers and steel substrates and increased electrochemical activity during freeze/thaw cycles that promote the conversion from protective dense inner layers into less protective outer ones. Investigations show that freeze/thaw cycles create “superimposed damage effects” on corrosion processes, implying that the natural rust layer formation process, which normally requires 2–6 years of controlled wet/dry cycling, becomes seriously compromised under thermal cycling conditions. This results in enhanced corrosion rates and delays or incomplete patina stabilization compared to continuous atmospheric exposure conditions. The Nordic climate, where freeze/thaw conditions frequently hover around 0 °C rather than maintaining sustained cold periods, imposes more severe durability challenges. Comprehensive research studies focused on Nordic conditions are needed to clarify the causes and effects of freeze/thaw-induced degradation, quantify their influence on patina properties, and determine their long-term impact on the corrosion performance of weathering steel.

5. Purpose of Accelerated Corrosion Tests for Weathering Steel

Traditionally, the corrosion behavior of weathering steel was evaluated through long-term exposure tests in real-world atmospheric environments: rural, urban, industrial, and marine. While such natural exposure tests offer high reliability due to their ability to capture actual environmental interaction, these exposure tests are subject to several limitations, such as extended testing durations, high costs, variability in atmospheric conditions, and constraints related to specimen orientation. Moreover, corrosion results from natural exposure can vary significantly due to local pollution gradients and differences in environmental aggressivity, making direct comparisons challenging. To address these limitations, accelerated corrosion tests were developed. These tests are designed to simulate the long-term corrosion behavior of weathering steel within a significantly shorter timeframe by subjecting specimens to controlled, extreme environmental conditions. The primary aim is to replicate, intensify, and condense the natural weathering process to assess material degradation behavior, predict patina formation and stabilization, and estimate service life. By accelerating the corrosion process, these tests enable researchers to evaluate the durability of materials under specific environmental scenarios more efficiently. Since the introduction of weathering steel, researchers have developed various accelerated test methods to study the influence of alloying elements on corrosion resistance, the evolution of patina layers, and the degradation mechanisms under controlled environmental cycles. These methods have also been extended to investigate differences in protective characteristics between natural and artificially formed patinas, contributing to the development of artificial patination techniques.

The Cebelcor test, Kesternich test, Prohesion test, and Accelerated Corrosion test using Synthetic Ocean Water (ISO-16539) are among the most commonly used accelerated corrosion tests for weathering steel [65]. A key feature of these tests is wet/dry cycling, which closely imitates environmental fluctuations crucial for the formation and stabilization of a patina on weathering steels. Nonetheless, accelerated tests have their inherent limitations. No single test can fully simulate the complex conditions of genuine atmospheric exposures, including the influence of driving wind, infiltration of rain, varying levels of pollution, microbial impact, and changes in specimen orientation. Moreover, none of the tests incorporate solar radiation, particularly UV radiation, which is a critical factor in field exposure tests due to its effects on surface temperature, drying dynamics, and photochemical reactions that accelerate patina development and influence corrosion behavior. As a result, the performance of weathering steel in one chemically active environment may not accurately reflect its behavior in another environment. The lack of a clear and consistent correlation between accelerated tests and actual atmospheric conditions complicates the interpretation of results. Furthermore, the lack of standardized, commercially available equipment that is specially designed to meet the needs of varied environments is a limitation when designing appropriate accelerated protocols. Nevertheless, accelerated corrosion tests continue to be valuable tools for preliminary-stage material identification, comparative assessment, and pattern recognition. The accelerated test findings should be cautiously interpreted and ideally verified using natural environmental exposure data. When combined with field exposure studies, these two approaches offer a comprehensive understanding of corrosion mechanisms, which could lead to the improvement of weathering steel resistance to extreme and common atmospheric conditions. The critical factors essential for accurately simulating patina formation and corrosion kinetics are given in Table 2. The test is not valid without them; the red triangles represent the most important factors, and green ones represent secondarily important factors. Recommended factors enhance realism and improve correlation with specific outdoor atmospheric conditions. Optional factors represent specialized phenomena and may be included for targeted studies.

Table 2.

Key environmental factors important for developing an efficient accelerated test.

The most common accelerated corrosion test methods used for weathering steel by researchers are the salt spray test, the damp heat corrosion test, the Cebelcor test, the Prohesion test, and the Kesternich test. These are briefly reviewed in the following sections.

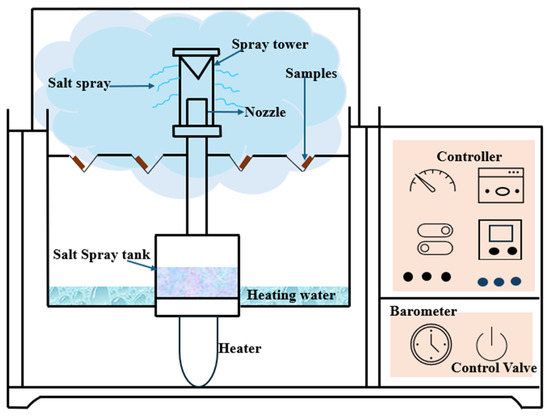

5.1. Salt Spray Test (ASTM B117-19 [66]/ISO 9227 [67])

Salt spray (fog) testing is still one of the most used accelerated corrosion testing procedures to test the corrosion resistance of metals and coatings, especially under marine-like conditions, such as standardized under ASTM B117. In this test, specimens are exposed to an atomized 5 percent NaCl solution with a pH of 6.5 to 7.2 in a sealed container at 35 C (95 F), as shown in Figure 8. The mist, carrying its salt load, is introduced under regulated pressure, producing an evenly moist, salt-rich environment, similar to coast exposure. The test, because of its ease of use, good reproducibility, and standardized nature, is useful for comparative ranking of materials, particularly for carbon steels and coated systems, but has much less application when dealing with weathering steels [66,67,68]. The test does not take into account important environmental factors, including cyclic wetting and drying, variable humidity, and atmospheric contaminants (i.e., , , , and PM) necessary for producing and stabilizing the protective patina typical of weathering steels. Therefore, the method is prone to overestimating corrosion rates and does not simulate the development of an oxide layer. Numerous articles have stressed the weak association between B117-19 findings and actual exposure data, and have cast doubt on its predictability, especially for atmospheric corrosion-related applications [49,69,70,71,72]. Furthermore, the material remains constantly wet and so precludes the formation of a protective passivating film, thus producing incorrect material durability underestimation. Notwithstanding these limitations, the salt spray test is a useful tool for comparing material systems on a preliminary basis, but it is not applicable for predicting the long-term performance or behavior of the patina on weathering steel in an atmospheric environment.

Figure 8.

Salt spray conditions are rarely observed in real environments.

5.2. Cyclic Corrosion Tests (Cebelcor Test)

The Cebelcor test (developed by the Belgian Centre for Corrosion Studies in 1966) is a cyclic electrochemical testing method that simulates the wet/dry alternation environmentally experienced by weathering steel in rural and urban environments with low sulfur dioxide concentration. The technique consists of a number of cycles of immersion of steel specimens in dilute sodium sulfate solution (10−4 M Na2SO4) followed by cycles of air-drying. The test successfully simulates the cyclic environmental conditions that enhance patina layer formation on weathering steels. Contrary to the continuous immersion test or salt spray exposures, the Cebelcor method enhances oxide layer growth by repeated electrochemical cycling, promoting the growth of corrosion products that are protective under certain atmospheric conditions; however, different researchers use varying wetting and drying cycling times [73,74,75,76,77].

However, the test has its limitations as it does not include environmental complexity like UV light, wind driven rain, bio-effects, and the combination of different atmospheric pollutants, such as , , or chloride ions, that play important roles in many real-world scenarios. In addition, the lack of standardization of the solution chemistry, cycle time, and drying conditions results in inter-lab variability and hampers better reproducibility. Montoya et al. demonstrated that although the test can accelerate the growth of patina, it tends to produce rust layers that are rich in lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH) and contain relatively little or no goethite (α-FeOOH)—a key phase in stable, protective patina formation in the atmosphere [73]. Thus, while the Cebelcor test provides a valid means of comparing and ranking weathering steels subjected to cyclic exposure under controlled conditions, it does not fully simulate the complex processes of degradation occurring in the atmosphere.

5.3. Cyclic Corrosion Tests (e.g., Prohesion, ASTM G85 A5 [68])

Cycle tests for corrosion (e.g., ASTM G85 Annex A5, also known as the Prohesion test) have been developed to mimic atmospheric exposure to a greater extent than continuous exposure methods such as ASTM B117. Developed in the 1970s by F.D. Timmins and Mebon Paints to test protective coatings on steel structures (e.g., British Rail), the Prohesion test uses a repetitive cycle of wet and dry, which is more representative of natural weathering processes. Specimens are periodically subjected to a fine, atomized mist of a dilute, acidified electrolyte consisting of 0.05% NaCl and 0.35–0.40% (NH4)2SO4 (pH ~3) at ambient temperature for one hour, followed by a forced-air drying cycle at 35 °C for 1 h. This provides the opportunity for oxygen replenishment during the drying phase, which combined with the acidic nature of the electrolyte promotes electrochemical conditions similar to those of urban or rural industrial atmospheres.

However, for weathering steels the test was used to mimic marine atmospheric conditions. The repeated cycle of exposure enhances the initial patina development, its transition to multi-layered rust, and the readily perceived formation of a dual-layer rust structure: a firmly attached layer (inner) and a non-firmly attached layer (outer) that will fall off, delaminating [73,78,79,80]. Despite its improved simulation of field-relevant processes, the Prohesion test still has its limitations. It does not account for actual marine environmental factors including UV radiation, cyclic changes in humidity, wind-driven rain, and various loads of pollutants (e.g., nitrates, O3, and particulates), all of which contribute significantly to the long-term atmospheric corrosion response. Furthermore, experimental evidence suggests that stabilization of patina is not always complete in the period of testing and the rates of corrosion might be artificially high because of the short durations of wet/dry cycles [73]. It is also significant to observe that, under Prohesion, akaganeite (β -FeOOH)-type corrosion products commonly formed in the presence of chlorides at marine exposures are not present, thereby restricting its applicability to marine exposure evaluation. Thus, although the Prohesion test represents a more dynamic and mechanistically constructive criterion for the comparative assessment of coatings and alloy performance, it still lacks sufficient predictive power for evaluating the long-term service life and for simulating the complex environmental exposures, especially for weathering steels.

5.4. SO2-Enhanced Tests (Kesternich Test)

-accelerated corrosion tests, in particular the Kesternich test (DIN 50018 [81] /ISO 22479 [82]), are standardized cyclic exposure tests intended to simulate highly polluted urban or industrial atmospheres with a high content. The protocol consists of exposing the samples in a sealed chamber with a 100% relative humidity at 40 ± 3 °C to gas (1.0–2.0 L per 300 L chamber, which is equivalent to 0.07–0.14% vol in the units of measurement gas-volume/volume air) for a defined period of time. Each cycle consists of 8 h exposure to the above conditions (simulating acid condensation similar to acid rain) followed by a 16 h period of aeration at room temperature and low humidity (~18–28 °C, ≤75% RH). The cyclic mode enables the rapid establishment of acidic surface films and promotes sulfation reactions that affect the rust stratigraphy of the metals [73,81,82,83].

In the case of weathering steels, the Kesternich test gives valuable information about the corrosion behavior in very aggressive -rich atmospheres, especially regarding the stability and adherence of the patina layer [73]. The occurrence of an inner goethite (α-FeOOH)-enriched dense layer and an outward lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH)-rich loose layer is observed experimentally with overall high corrosion rates and short stabilization times. It is, however, a very strong exaggeration of corrosivity compared to modern urban atmospheres in which the levels of have dropped significantly (especially in Europe) and where pollutants such as , , and PM have increased. In addition, ignoring decisive environmental factors such as UV, wind-driven wetting, and the deposition of mixed pollutants further undermines the eco-validity of this approach. Therefore, although the Kesternich test continues to serve as a valuable tool for evaluating material resistance in the context of worst-case acidification scenarios, its results need to be considered carefully, especially when used for the prediction of field performance in the case of weathering steels.

5.5. Accelerated Corrosion Test Using Synthetic Ocean Water (ISO-16539, 2013 [65])

ISO 16539 describes a procedure (Method A and Method B) for accelerated cyclic corrosion test using synthetic sea water as a testing medium to reproduce exposure conditions for metallic and non-organic coatings in marine environments dominated by chloride-inducing corrosion. This standard is essential for evaluating the performance of metallic substrates and protective coating systems. The process involves controlled stages of salt deposition, humidity and drying in which a synthetic seawater solution with ionic species (Na+, Cl−, Mg2+, Na2+, SO42−, etc.) that mimics the physical and chemical characteristics of natural seawater is used.

In ISO 16539 Method A, the test includes dry conditions (49 ± 1 °C and relative humidity 32 ± 5%) and wet conditions (30 ± 1 °C and relative humidity 95 ± 5%), with salt deposition on the surface of 250 g/m2 ±50 g/m2 per cycle. Method B consists of spraying the specimens with 3.5% NaCl artificial seawater until a salt deposition of about 28 g/m2 is reached on the surface of specimens, followed by cyclic exposure of 8 h, composed of 3 h drying at 60 °C and 35% RH, and 3 h humidification at 40 °C and 95% RH, together with transitions between these stages [65,84,85].

Jiang et al. used ISO 16539 Method B to evaluate the corrosion characteristics of weathering steel [85]. This controlled environment approximates the alternating exposure to salt-laden air and moisture that towns and cities located close to the seacoast experience in service. For weathering steel, this test is especially relevant, since chlorides have been reported to destabilize the formation of a compact, adherent patina causing localized corrosion, pitting, and shifting from protective α-FeOOH phases to more soluble and less adherent β-FeOOH (akaganeite). Using partial wetting immersion of weathering steel under ISO 16539 conditions showed either improved rust stratification or faster kinetics of the corrosion. Although this approach gives important comparative perspectives of chloride-induced degradation mechanisms, it is inherently simplistic in terms of ecological realism. It fails to provide environmental variables, like UV exposure, biological colonization, wind-driven saline-aerosols, diurnal thermal fluctuations, and the presence of situ-specific contaminants, which also have a great impact on the corrosion of weathering steels in real marine environments. Further, the harsh and constant nature of laboratory conditions often overestimate material degradation. Therefore, although ISO 16539 is a rigorous and repeatable test that can be used to assess material performance relative to one another in chloride rich environments, due to overestimation of the results, the data obtained from this test should be applied judiciously with regards to long-term field performance and real-world service-life prediction. Moreover, it is important to evaluate the patina profile, composition, and protective capability. Understanding how continuous washing and salt deposition affect the patina is essential to determine whether corrosion occurs uniformly or if localized pitting develops due to uneven salt deposition.

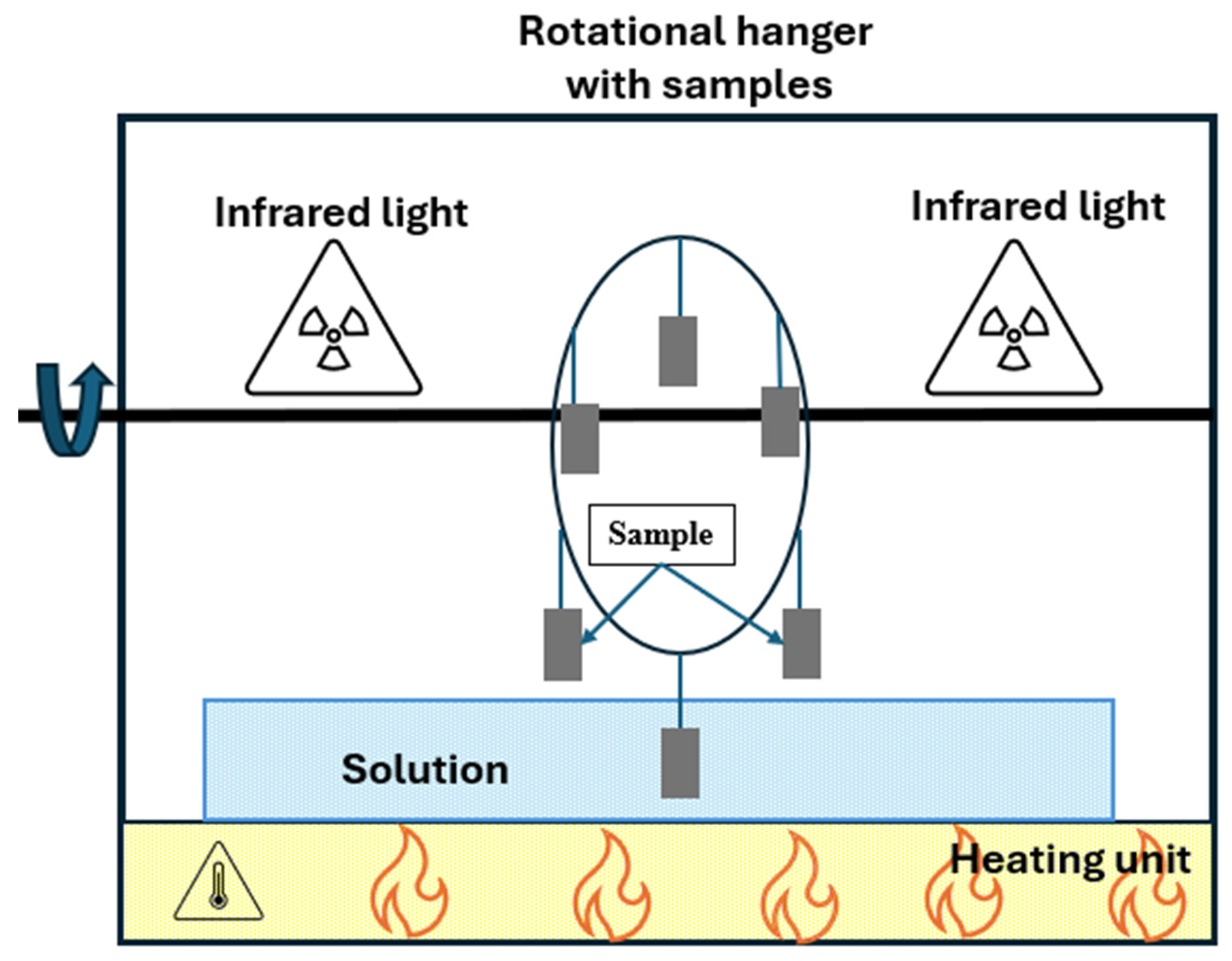

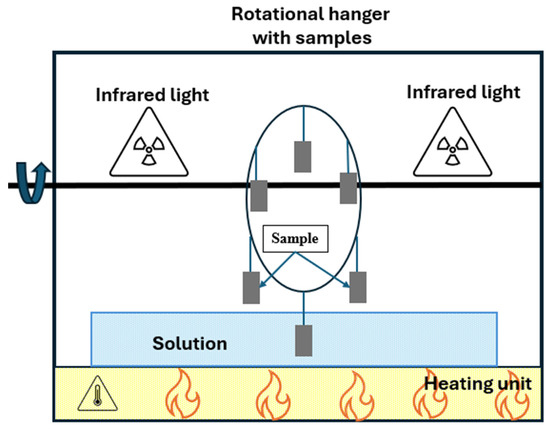

Despite the use of standardized protocols, several other accelerated corrosion test methods developed by researchers in Japan, Europe, or North America have sought to provide a better simulation of region-specific environmental conditions, as shown in Figure 9 [84,85,86]. Although these methods have provided valuable information on corrosion mechanisms in local atmosphere, most of them are still constrained by the dependence on one-variable environmental conditions (such as constant humidity, a single pollutant gas, e.g., SO2, or a constant temperature exposure).

Figure 9.

Experimental chambers developed by different researchers.

Such simplified test designs are inadequate representations of the synergistic and time-dependent interactions that control corrosion and patina formation in uncontrolled, natural atmospheres. Therefore, although such tests show a good repeatability in the laboratory, they have poor external validity and are not representative of the multi-factorial nature of atmospheric corrosion environments, especially when UV radiation, variable moisture, freeze/thaw effects, kinetic effects, and biological activity are taken into account.

In addition, lack of standardized parameters among these methods, for example, dosage of pollutants, pollutant exposure times, or preconditioning treatments, still contributes to preventing cross-comparisons and reproducibility. Additionally, with no validation using long-term weathering test data, the predictive ability of accelerated corrosion tests for long-term performance of weathering steel is still unknown. Therefore, despite their novelty, many of the single-variable approaches independently highlight the need for multi-dimensional or harmonized, field-correlated accelerated corrosion testing protocols.

The key environmental aspects present in the above corrosion accelerated tests important for simulation of real environmental conditions are given in Table 3. Some factors are present as shown by a red tick (√) and some environmental factors that need to be modified are represented by a green tick (√).

Table 3.

Accelerated corrosion tests with different environmental aspects.

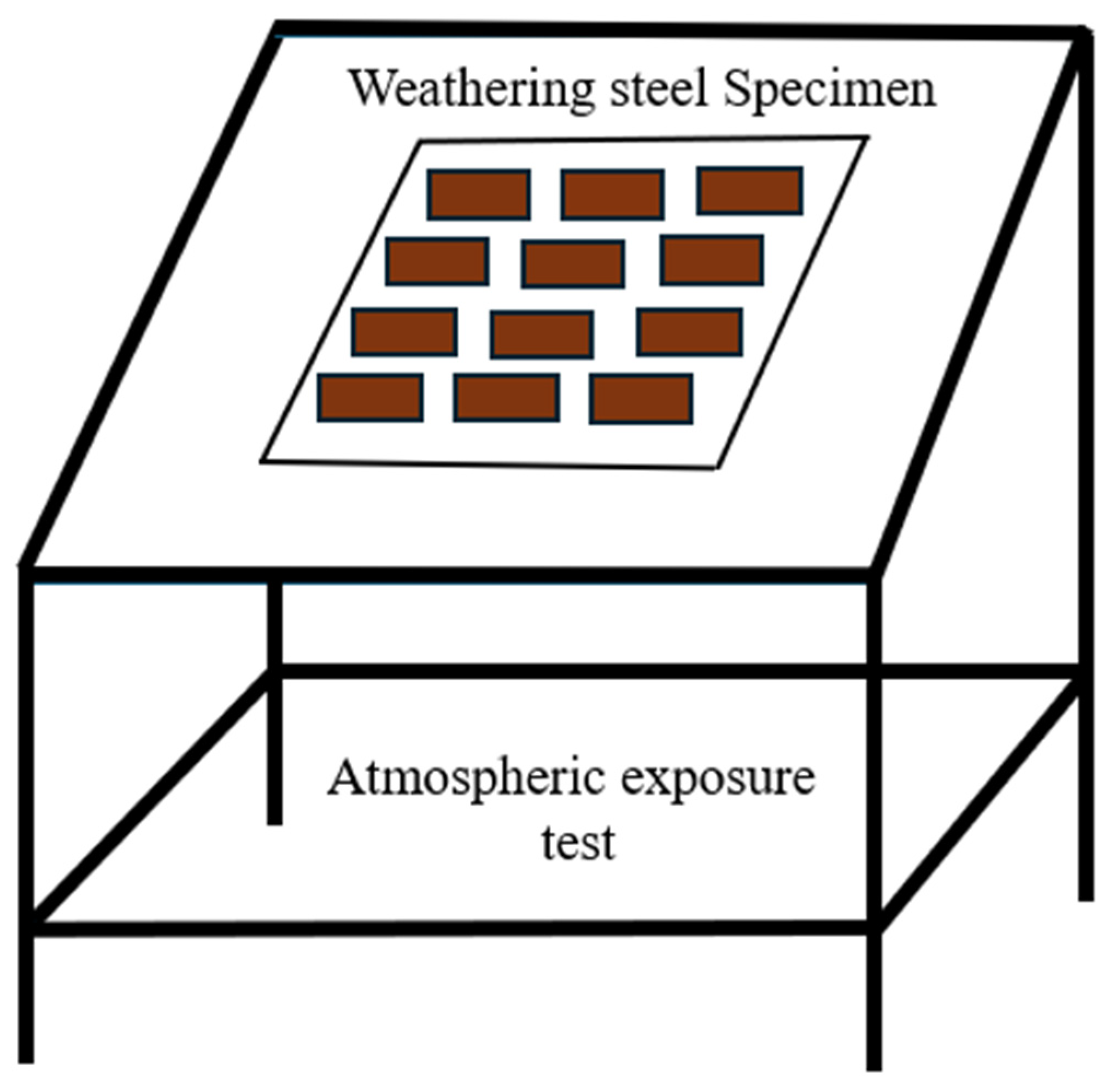

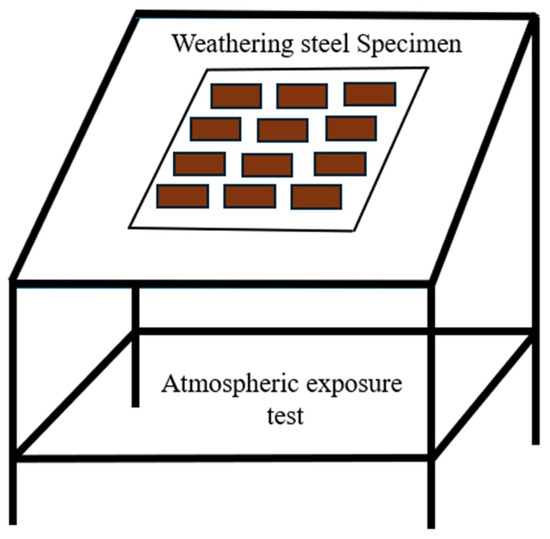

5.6. Field Exposure vs. Lab Tests

The assessment of corrosion resistance, durability, and performance of weathering steels is typically conducted through natural field exposure and laboratory-based accelerated testing. Field exposure is the most reliable way to evaluate patina formation and long-term stability under real atmospheric conditions. These tests encapsulate the comprehensive range of environmental parameters including wet/dry cycling, temperature/humidity changes, pollutant deposition, and exposure to ultraviolet radiation, all of which play key roles in the development of protective iron oxyhydroxides (such as goethite; α-FeOOH). The presence of the alloying elements chromium (Cr), copper (Cu), and nickel in weathering steel enhances the transformation and densification of the patina, contributing to improved corrosion resistance. Long-term field exposure tests, as shown in Figure 10, typically lasting between 2 to 10 years, have reported corrosion rates ranging from 0.002 to 0.01 mm/year under natural atmospheric conditions. Although field tests generate high-quality data under highly varying climates, the main drawbacks are that the tests are lengthy in time, environmental conditions are uncontrollable, labor costs are high, and using the resources is complex.

Figure 10.

Appearance of atmospheric exposure test chamber.

On the other hand, laboratory accelerated corrosion tests are meant to mimic decades of atmospheric exposure in weeks or a few months. These techniques allow accelerated testing of alloy performance and corrosion mechanisms using controlled variables, such as humidity, temperature, and pollutant concentration. These accelerated tests are highly efficient and cost-effective, and provide mechanistic insights, and are therefore suitable for comparative studies and for screening of materials at early stages. Yet, they generally fail to reproduce the complete set of conditions that are typical of outdoor environments and, consequently, may lead to poor correlation with the performance in the field. A few of the more common tests, such as salt spray (fog) or Kesternich, actually exaggerate certain environmental parameters (e.g., extended wetness or high SO2 exposure), which can change corrosion mechanisms and prevent formation of a stable protective patina. The comparison between the two approaches is summarized in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Comparison between field exposure test and laboratory tests.

6. Challenges

Standard accelerated corrosion assessment techniques used to evaluate weathering steel often prove to be less capable of predicting long-term atmospheric performance. The inconsistency arises from the dynamic and complicated interactions occurring in ambient environments leading to formation of stable and protective rust layers, in particular the goethite-rich rust phase, which is vital to corrosion-resistance properties. Laboratory-based tests generally do not reproduce real-world issues such as fluctuating humidity, thermal cycles, the fall out of pollutants, and periods of wetting/drying, all of which exert a striking effect on the kinetics and morphology of patina development. A number of studies have revealed a poor correlation between accelerated test results and field performance and, hence, the difficulty in selecting materials suitable for different real-world applications in different environments like marine, industrial, rural, and urban exposures [52,86]. The intrinsic diversity of the atmospheric conditions in which these tests must take place combined with the inherent variability of the material properties have led to the complete lack of a “one-size-fits-all” test protocol. As a result, the development of an accelerated corrosion technique that can accurately replicate the natural weathering processes continues to be a critical scientific and technical challenge and requires further understanding of the mechanism of patina evolution and interaction with the environment. The key challenges or obstacles for developing a good, accelerated test are discussed below.

6.1. Environmental Challenges

6.1.1. Multi-Environmental Challenge

The wide variation in environmental conditions makes the development of a universally applicable accelerated corrosion testing methodology for weathering steel extremely difficult. Marine atmospheres are high in chlorides, industrial atmospheres are high in acidic pollutants (SO2, NOx), and urban environments are saturated with complex stress conditions such as traffic fumes, thermal changes, and humidity changes. In contrast, rural environments have lower pollutant loads but exhibit variable moisture conditions like dew or frost. These differences greatly influence the microstructure, morphology, and rate of stabilization of the patina layer that develops on the surface of weathering steels [16,17,18,19].

Empirical studies show that diverse atmospheres, from tropical and marine to semi-arid, polar, and light industrial, produce distinct corrosion modes and patina characteristics. Such environmental variability cannot be reproduced by any single accelerated corrosion test. Penetration rates, corrosion modes, and protective film evolution are significantly different under different atmospheres, highlighting the limitations of a “one-type-for-all” concept. Real environments contain multiple corrosive agents, such as SO2, NOx, CO2, sea salts, and organic materials, that interact synergistically or antagonistically. Introducing a multi-pollutant mixture may generate unpredictable reactions not representative of field conditions. Biological and particulate matter, e.g., microbial colonization, moss growth, plants, and airborne dust, also influences patina formation but is largely absent in laboratory-based accelerated tests. These factors complicate the development of reliable accelerated protocols, especially for weathering steel dependent on stable patina formation.

6.1.2. Challenges of Seasonal and Diurnal Cycles (Wet/Dry, Temperature, UV)

Simulating complex seasonal and diurnal environmental fluctuations (e.g., wet/dry cycling, temperature variation, humidity variation, and UV exposure) in the development of accelerated corrosion testing of weathering steel is a significant challenge. In the natural environment, steel experiences extremely dynamic patterns of cycles of rain, dew formation, drying, freeze/thaw, and sunlight. These environmental variables are not only random but may interact non-linearly with each other, and thus their exact reproduction or accurate simulation under laboratory conditions is highly challenging and, in many instances, impossible.

Patina formation, composition, and crystallinity of the rust, as well as corrosion rates, have been reported to be strongly affected by both the frequency and duration of wet/dry cycles, as well as by temperature and relative humidity variation. Long wet periods can lead to localized corrosion, enhancing pitting and changing the oxide morphology, whereas long dry periods or low-temperature conditions may hinder the kinetics of corrosion and prolong time to patina stabilization. Finding the right combination of cycle time and conditions in order to simulate natural patina evolution, while not adding any unwanted or artificial corrosion behavior to the patina, is very challenging [24,53,87,88,89,90].

Adding to this complexity are the differences in corrosion performance exhibited by different alloys and grades of weathering steel, which may necessitate customized environmental exposure scenarios for realistic patina formation. There are currently no established standards or widely accepted guidelines for universally applicable conditions (wet/dry cycles) in accelerated corrosion tests; hence, further research and development in this domain is much needed.

6.1.3. Correlation Challenges Across Environments

A persistent challenge in weathering steel research is the weak correlation between laboratory-accelerated test results and long-term field exposures. Significant discrepancies in corrosion behavior are consistently reported between accelerated environments and natural atmospheres. Even replicated field exposures, conducted under relatively similar or identical conditions, show variability, highlighting the role of subtle, frequently uncontrollable, environmental conditions.

The complexity is further evidenced in materials that perform well in one atmosphere that may corrode severely in another, further complicating accelerated testing. Such variability makes global, one-protocol accelerated test schemes scientifically unreliable. The wide spectrum of mechanical and corrosion properties prevents the development of a universally accelerated laboratory test. These inconsistencies highlight the difficulty of establishing a standardized test capable of producing reproducible, field-relevant results across all environments. Consequently, site-specific accelerated test protocols have emerged as a more viable and technically sound approach. They allow simulation of dominant corrosive parameters characteristic of each atmospheric category. This enhances predictive accuracy, improves material ranking, and supports more reliable selection of weathering steel for specific service conditions.

6.2. Scientific Challenges in Oxide Formation

6.2.1. Rust Chemistry and Kinetics

The multi-layer patina formed on weathering steel during field exposure consists of various oxides and oxyhydroxides such as γ-FeOOH (lepidocrocite—initial stage), β-FeOOH (akaganeite, associated with , α-FeOOH (goethite—stable and protective phase), and (magnetite). However, accelerated tests often result in higher concentrations of lepidocrocite or akaganeite rather than the stable goethite phase. The formation of stable goethite (α-FeOOH) is one of the most critical aspects of developing a protective patina on weathering steel, yet it remains one of the most difficult to replicate in accelerated testing. Goethite requires specific crystallization conditions, including carefully controlled wetting and drying, specific pH levels, and extended exposure durations, which allow the transformation of lepidocrocite to goethite. A key metric used to evaluate the stability of the patina is the mass ratio of goethite to the lepidocrocite mass ratio ( often referred as the stability index. Accelerated lab tests typically struggle to achieve this natural, stable corrosion product due to their inability to mimic the complex environmental interactions required for goethite formations.

The protective performance of weathering steel depends largely on the development of a compact, stable, and adherent oxide layer with goethite as its primary component. Artificial conditions in accelerated tests often promote the formation of less stable oxides or alter the crystalline structure of the protective patina layer, leading to results that poorly correlate with real environments and fail to reflect long-term performance characteristics.

6.2.2. Alloy Element Effects