Abstract

Ultra-high heat input welding offers high efficiency for large-scale offshore engineering, but excessive heat input can degrade low-temperature toughness. This study investigates the microstructural evolution and impact toughness of EH36 ship steel under high heat inputs (300–500 kJ/cm) using Gleeble-3500 thermal simulation, Charpy impact tests, and multi-scale characterization (OM, SEM, EBSD). Results show that impact toughness peaks at 400 kJ/cm, with surface and core energies reaching 343.33 J and 215.18 J, respectively. The optimal toughness is attributed to the formation of acicular ferrite and a high fraction of high-angle grain boundaries (up to 48.7%), which effectively inhibit crack propagation. These findings provide a practical basis for selecting heat input to balance welding efficiency and mechanical performance in marine steel fabrication.

1. Introduction

Welding processes with a heat input exceeding 300 kJ/cm are referred to as ultra-high heat input welding technology [1]. As offshore development advances, the demand for marine steel plates continues to increase. Compared with traditional multi-pass welding, ultra-high heat input welding can complete thick-plate welding in a single pass due to its high heat input [2,3]. The high welding efficiency significantly reduces processing time and energy consumption, leading many enterprises to increase heat input for the single-pass welding of thick plates [4]. However, while large heat input welding improves welding efficiency, it also comes with the risk of grain coarsening, which leads to a decrease in toughness [5].

EH36 steel is a typical low-alloy, high-strength marine steel, renowned for its excellent impact toughness, corrosion resistance, low-temperature toughness and good weldability [6,7,8,9]. It is widely applied in key fields such as shipbuilding, offshore engineering platforms, and large bridges and buildings [10]. As modern marine resource development continues to venture into the deep sea and polar regions, structures such as ships and offshore platforms are often exposed to lower temperatures and endure harsh environments like wave impacts and ice collisions [11,12]. These place higher demands on the low-temperature impact toughness of the welding area of EH36 steel.

The heat-affected zone (HAZ), particularly the coarse-grained region (CGHAZ), is often the most critical region in a welded joint because it undergoes significant microstructural changes that can lead to localized embrittlement [13]. Many scholars have studied the influence of heat input on materials. Han et al. [14]. have shown that high heat input can reduce the content of acicular ferrite and granular bainite in the weld seam and coarsen the grains. Xiao et al. [15]. investigated the influence of heat input on the low-temperature toughness of welded joints and pointed out that a lower heat input can reduce composition segregation and dendrite size, thereby enhancing the low-temperature toughness of the joints. Xu et al. [16]. investigated the influence of the size and type of inclusions on the nucleation of acicular ferrite in the material. International research by authors such as Bhadeshia [17] has also emphasized the critical role of microstructure control in the HAZ for ensuring joint integrity. Jiang et al. [18] reported that post-weld heat treatment of welded joints can significantly enhance impact toughness. At present, in the application process of EH36, high linear energy welding technology is often adopted for welding. However, excessive heat input may cause the growth of austenite grains to become coarser. It may even form brittle phases, thereby reducing the toughness of the welded joint. However, most of the existing research focuses on lower heat inputs (<300 kJ/cm), while the studies on the influence of heat inputs above 300 kJ/cm on the low-temperature impact toughness of EH36 steel are limited, which to some extent hinders the application of EH36 steel [19,20].

In this work, welding thermal cycles corresponding to different levels of heat input were simulated using a Gleeble thermal mechanical simulation system. The microstructural evolution within the simulated coarse-grained heat-affected zone (CGHAZ) was characterized utilizing optical microscopy (OM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The primary objective is to elucidate the correlation between welding heat input, resultant microstructure, and the low-temperature impact toughness of the CGHAZ. The findings derived from this research are intended to provide a scientific basis and practical guidance for selecting appropriate welding parameters, specifically heat input, during the fabrication of low-alloy, high-strength marine steels.

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

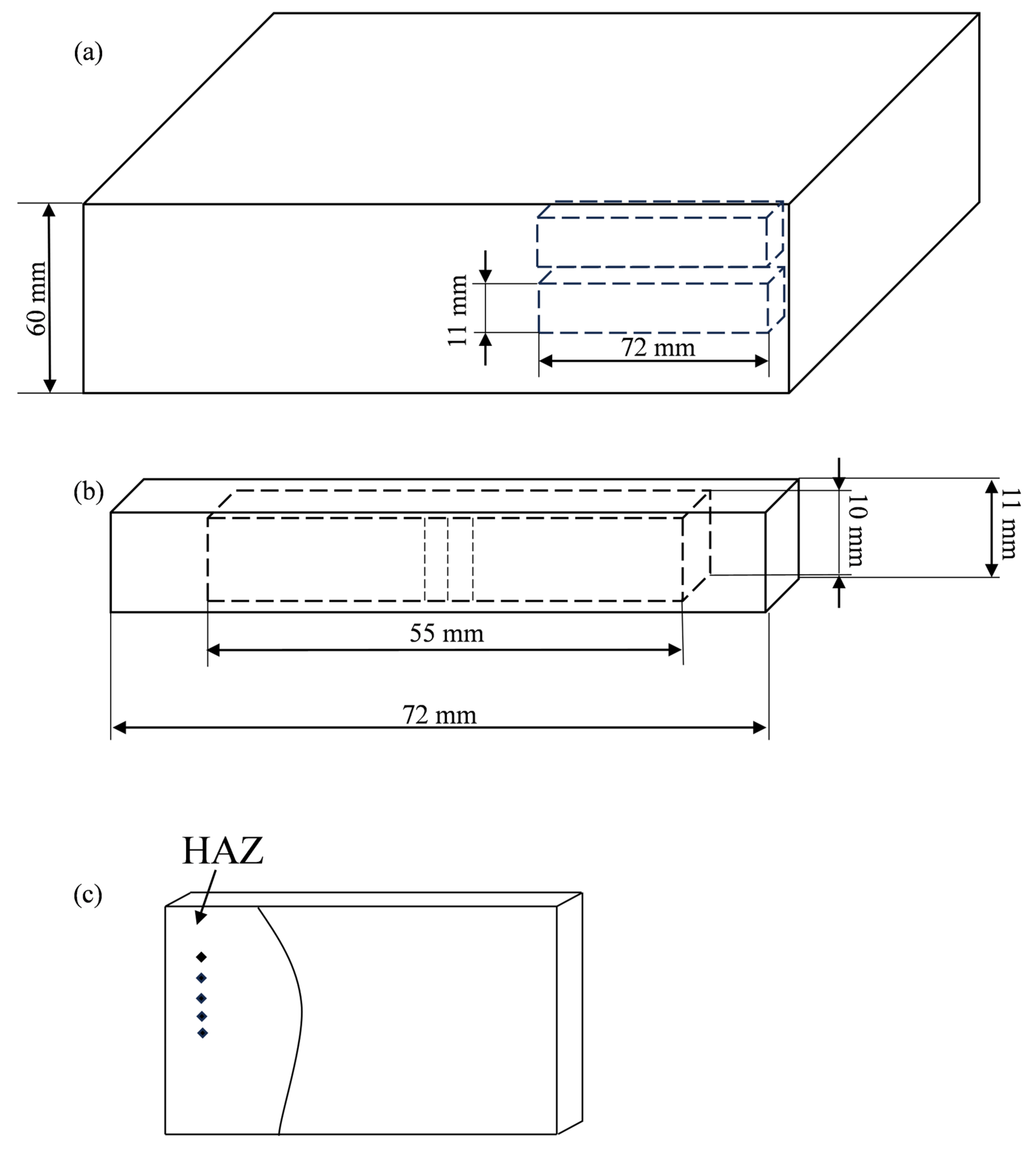

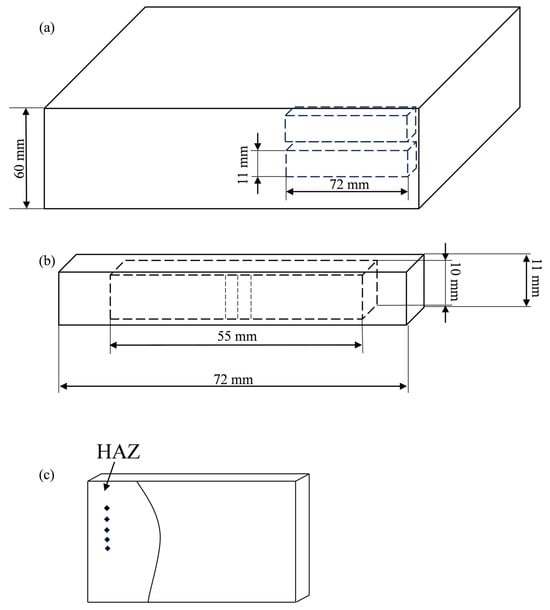

The simulations utilized a commercial EH36 steel plate, the detailed chemical composition of which is provided in Table 1 (composition provided by the steel manufacturer). The base material impact energy ≥ 345 J at −40 °C. As shown in Figure 1a, thermal simulation specimens with dimensions of 72 mm × 11 mm × 11 mm were cut from the surface and the core (1/2 thickness) of the steel plate, respectively, by wire cutting. The welding thermal simulation experiment was carried out using the Gleeble-3500 (Dynamic Systems Inc., Poestenkill, NY, USA) thermal mechanical simulation system. The specific experimental conditions included a heating rate of 130 °C/s, a peak temperature of 1300 °C, a holding time of 1 s, and a welding heat input of 300–500 kJ/cm; the cooling rate was calculated by the Rykalin [21] model. For each heat input condition, three surface and three core specimens were prepared and tested to ensure statistical reliability. Impact test samples were cut from the samples after thermal simulation by wire cutting, as shown in Figure 1b. The sample size is a standard specimen of 55 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm. The low-temperature impact toughness is tested at −40 °C, with anhydrous ethanol as the cooling medium. After cooling to the specified temperature, the sample is placed in a low-temperature bath and maintained for 15–20 min before the impact test is conducted. After the test is completed, the fracture morphology is observed using SEM (Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic). Then, a small piece of sample is cut from the impacted sample using wire cutting for traditional metallurgical grinding and polishing. The microstructure was characterized by erosion with 4% nitric acid–ethanol solution and by OM (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and SEM. The Vickers hardness distribution of the core and core samples was measured using a Vickers microhardness tester (Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA) with a load of 500 g. Five indentations were made for each specimen condition. After re-grinding and polishing, the surface stress layer was removed by electrolytic polishing with a 10% perchloric acid–alcohol solution, and the crystallographic information of the sample was analyzed at an accelerated voltage of 20 kV using EBSD.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of EH36 steel (wt.%).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagrams of sampling for thermal simulation specimens (a), impact specimens (b), and Vickers hardness (c).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Low-Temperature Impact Toughness and Microhardness

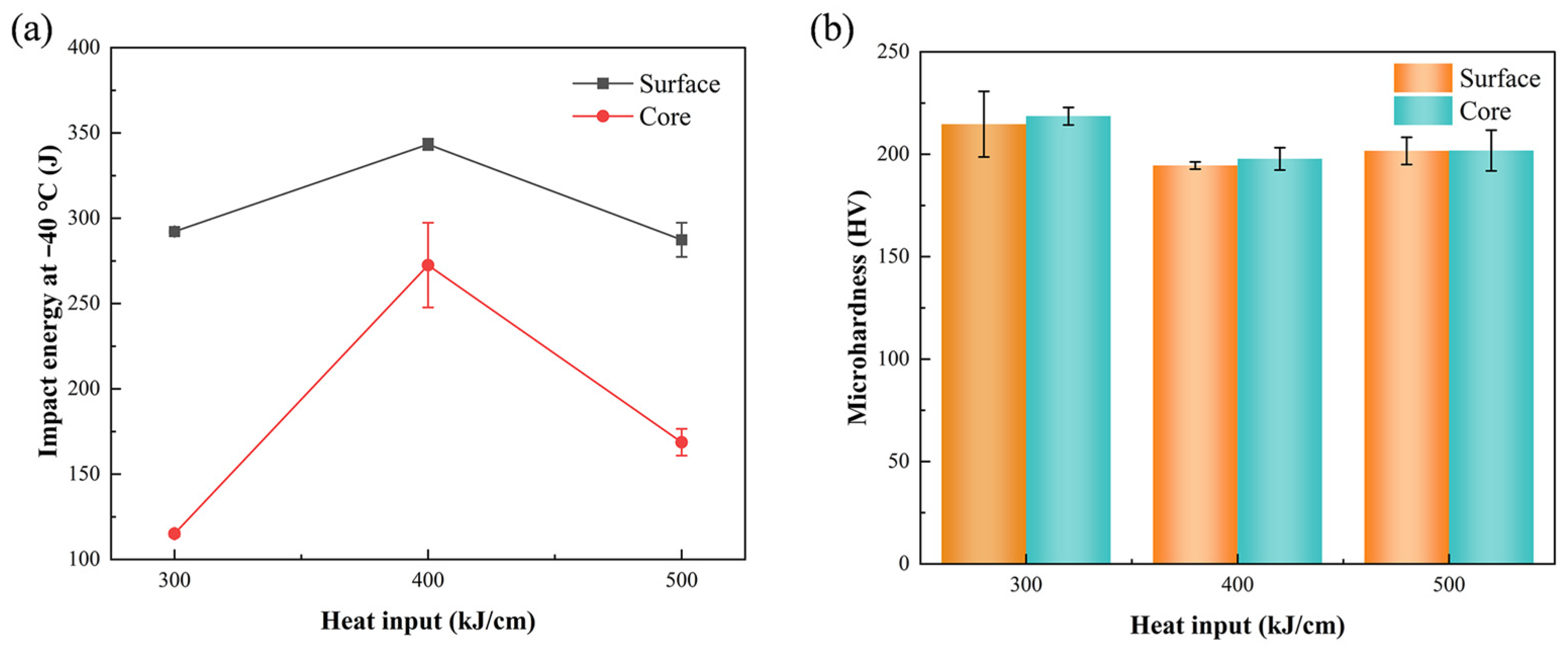

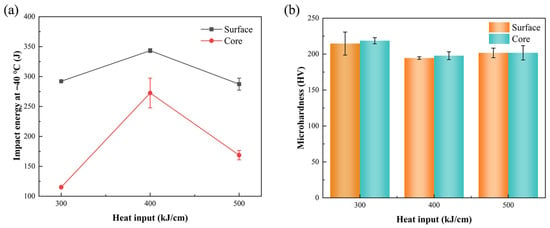

The relationship between the measured impact absorption energy (at −40 °C) and the applied welding heat input for both surface and core regions of the simulated CGHAZ is graphically summarized in Figure 2a. A consistent pattern emerged for specimens at both locations, characterized by an initial increase in impact toughness with heat input, followed by a peak and a subsequent decline. For specimens extracted from the surface region, the impact energy rises from 292.15 J at 300 kJ/cm to a peak of 343.33 J at 400 kJ/cm, before declining to 287.35 J at 500 kJ/cm. A more pronounced trend is evident in specimens from the core region. Here, the impact energy increases substantially from 115.07 J at 300 kJ/cm to 215.18 J at 400 kJ/cm, followed by a decrease to 168.70 J at 500 kJ/cm. These results clearly indicate that an optimal heat input of 400 kJ/cm yields the best combination of low-temperature impact toughness for both surface and core regions of the EH36 steel CGHAZ under the investigated conditions.

Figure 2.

Impact energy (a) and Vickers hardness (b) of the core and surface at the test temperature of −40 °C.

Figure 2b presents the corresponding Vickers microhardness measurements taken within the simulated CGHAZ for the different heat input conditions. The microhardness demonstrates an inverse correlation with the impact toughness trend. The 300 kJ/cm condition displayed the highest hardness values, with the surface and core measuring 214.6 HV and 218.6 HV, respectively. Conversely, the lowest hardness values coincide with the peak toughness condition (400 kJ/cm), measuring 194.5 HV and 197.7 HV for the surface and core, respectively. This inverse relationship between hardness and impact toughness is typical in steels and often reflects a trade-off between strength and ductility/toughness, influenced by microstructural features such as phase constituents, grain size, and dislocation density.

It is noteworthy that the impact energy results for the core specimens at 400 kJ/cm show greater variability (larger error bar), while the hardness measurements at the same condition exhibit the lowest variability. This apparent contradiction can be explained by the different sensitivities of the two tests: Charpy impact toughness is highly sensitive to local microstructural inhomogeneities (such as isolated brittle phases or large grains), which can cause scatter in results even if the average hardness is uniform. The high HAGB content at 400 kJ/cm may lead to a more tortuous crack path, which on average improves toughness but can also lead to greater test-to-test variability depending on the exact crack initiation site.

3.2. Impact Fracture Morphology

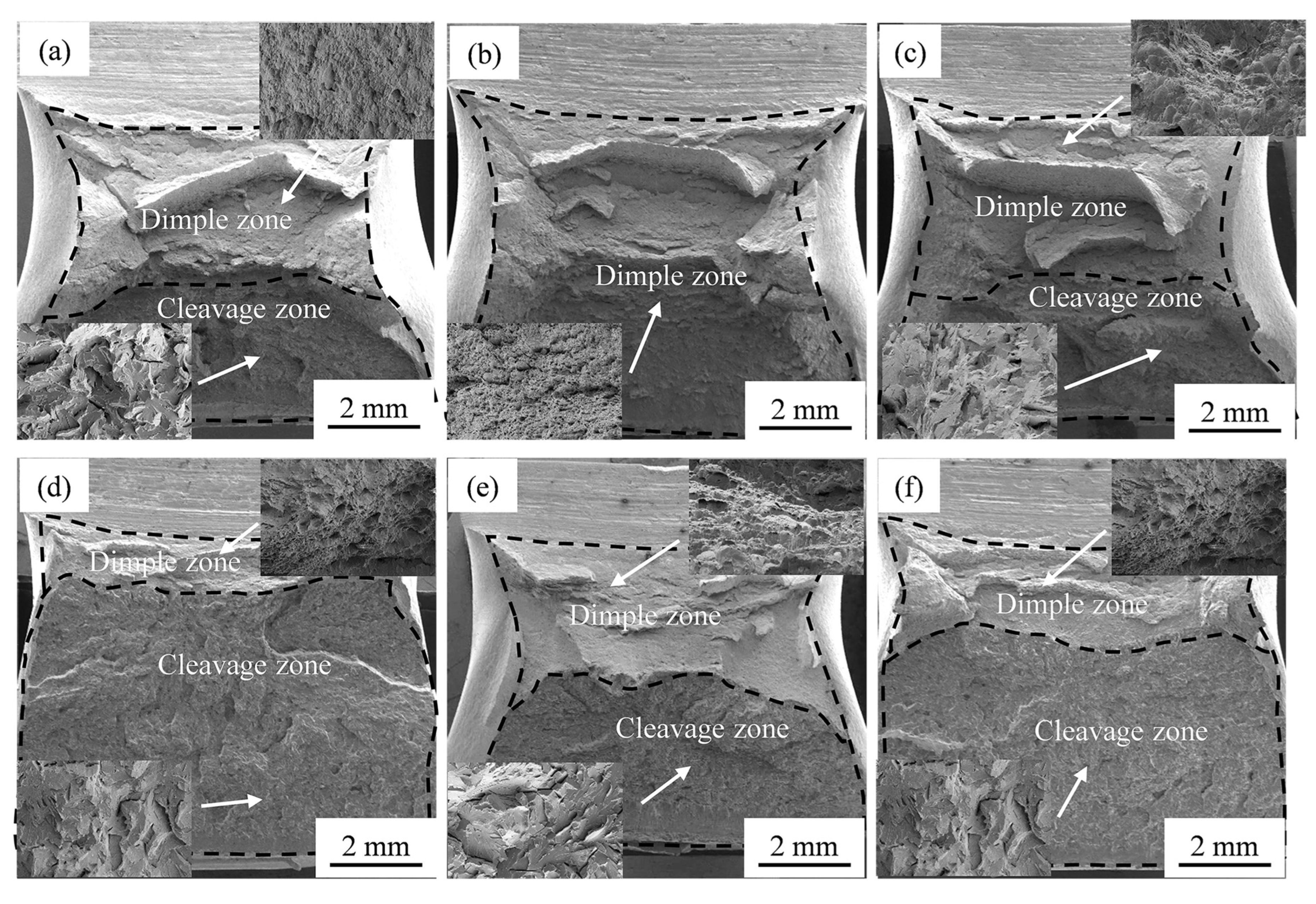

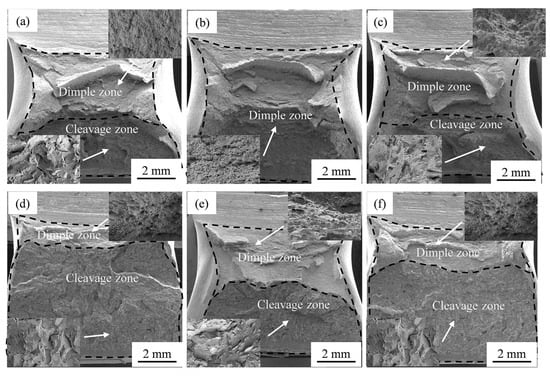

Figure 3 shows the SEM images of the impact fracture surface and core after thermal simulation under heat inputs of 300, 400 and 500 kJ/cm. For surface specimens, when the heat input is 400 kJ/cm, the fracture surfaces consist almost entirely of dimple zones (Figure 3b), while when the heat input is 300 (Figure 3a) and 500 kJ/cm (Figure 3c), the size of the dimple zones of the specimens decreases, and cleavage surfaces appear, but the dimple zones are mainly present. In the core sample, under a heat input of 300 kJ/cm (Figure 3d), only the fracture surface near the V-notch contains a very small number of dimples, while the fracture morphology in the distal region is predominantly cleavage. When the heat input is 500 kJ/cm (Figure 3f), the dimples near the V-shaped notch are slightly more than 300 kJ/cm, and the distal region is still dominated by cleavage. When the heat input is 400 kJ/cm (Figure 3e), the size of the dimple zone is the largest, each accounting for half of the cleavage surface. Except for the core sample of 400 kJ/cm, the remaining samples all exhibited the mixed ductile–brittle characteristics after thermal simulation.

Figure 3.

SEM images of the surfaces (a–c) and cores (d–f) of the simulated specimens with different heat inputs of 300 kJ/cm (a,d), 400 kJ/cm (b,e), and 500 kJ/cm (c,f) after Charpy impact tests.

3.3. Microstructure

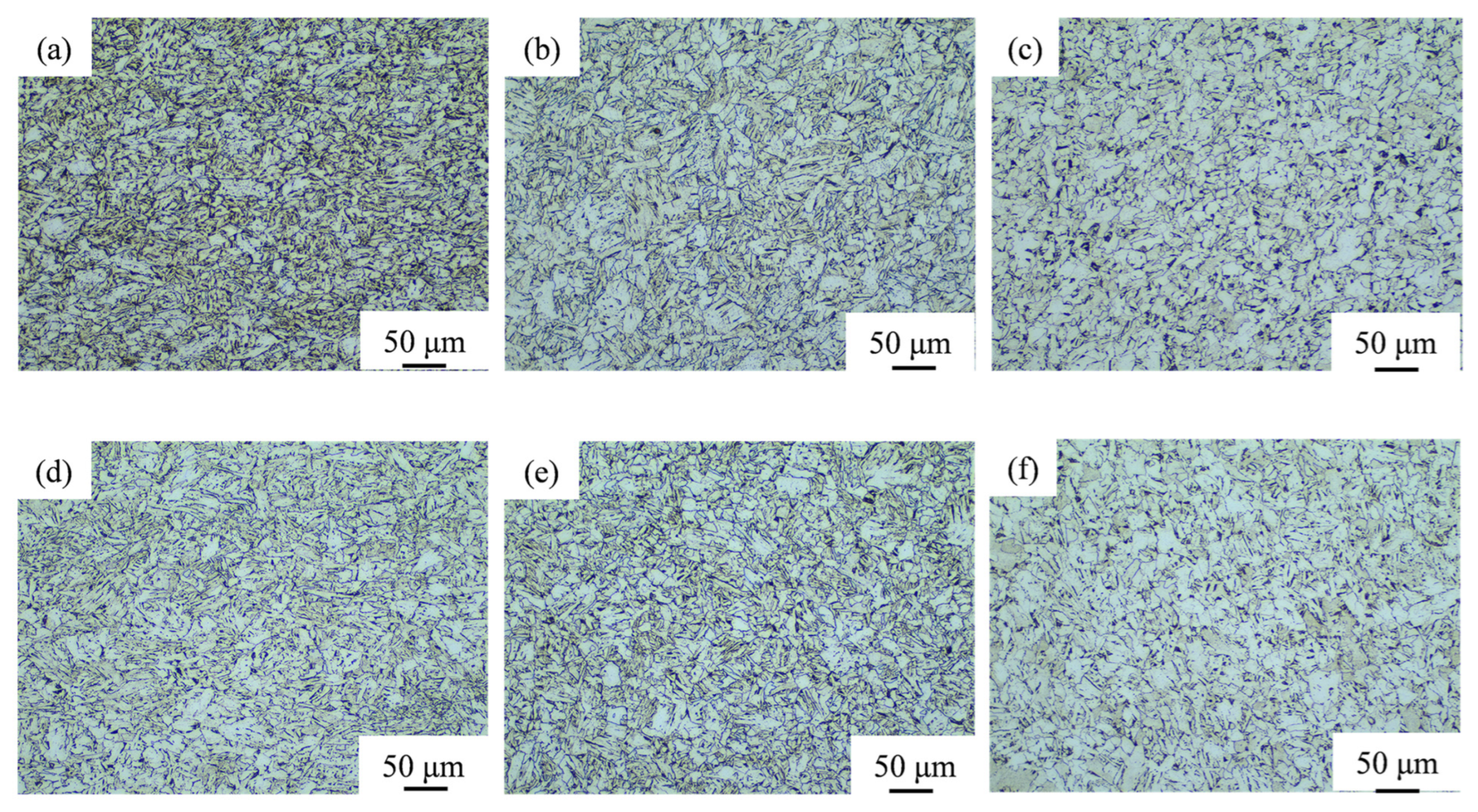

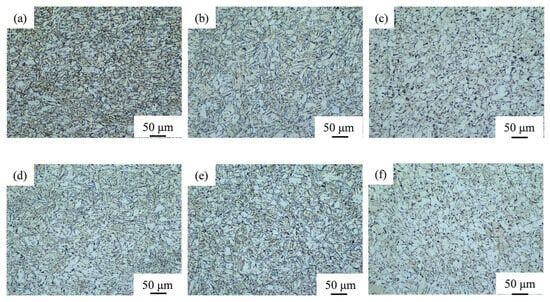

Figure 4 shows the metallographic structures of the surface and core parts under different heat inputs. The analyzed region corresponds to the center of the thermally simulated zone, as shown in Figure 4a, under a heat input of 300 kJ/cm; the metallographic structure of CGHAZ is partially larger and the structure is uneven. Figure 4b shows that there are many AFs distributed in the CGHAZ at the core with a heat input of 400 kJ/cm. Figure 4c shows that when the heat input reaches 500 kJ/cm, the grain size of the CGHAZ microstructure at the core tends to average out. The trend of the core sample tissue is roughly the same. The reason for this phenomenon might be that as the input increases, the related cooling rate also decreases accordingly. When the heat input is 300 kJ/cm, the cooling rate is relatively fast, and only a fraction of the grains had sufficient time to grow, thus avoiding uneven grain size. When the heat input is 500 kJ/cm and the cooling rate is slow, it provides sufficient growth time for the grains, so the grain size is uniform. Due to its “locking” or “interlocking” structural form, AF can effectively prevent crack propagation, thereby enhancing the impact toughness of the material [22]. Therefore, the impact toughness of the 400 kJ/cm sample is the highest. Although a small amount of AF was generated in the 300 kJ/cm core sample, its impact toughness was lower than that of the 500 kJ/cm sample. To explore this issue, SEM experiments were conducted on the samples.

Figure 4.

Metallographic images of surface (a–c) and core (d–f) specimens at heat inputs of 300 kJ/cm (a,d), 400 kJ/cm (b,e), and 500 kJ/cm (c,f).

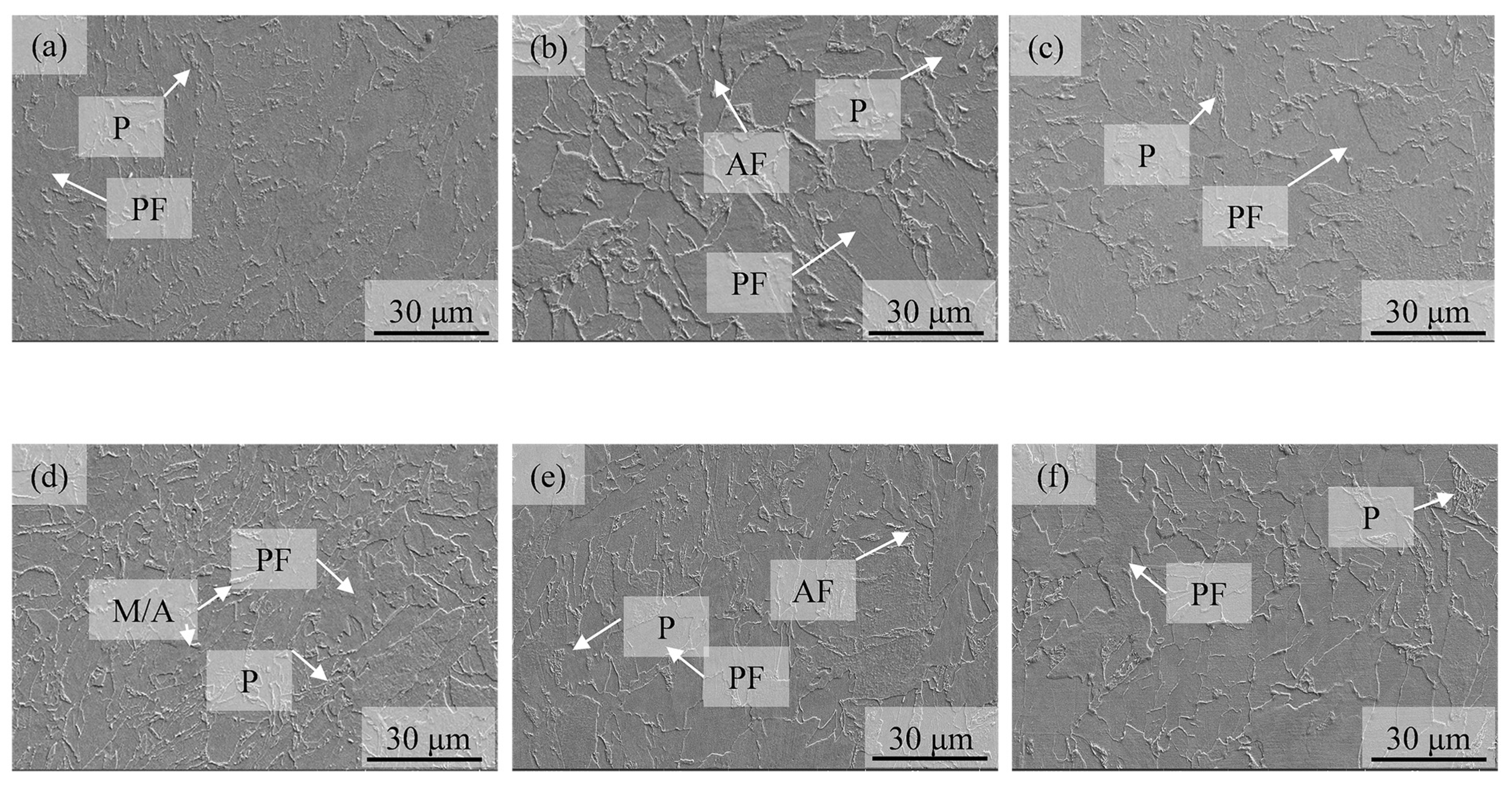

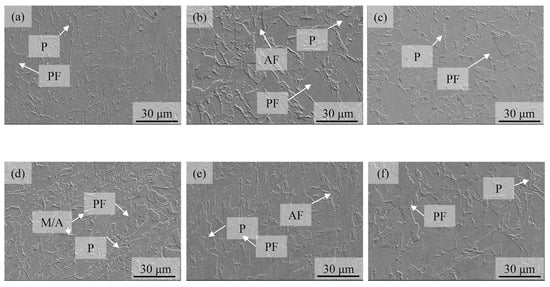

Figure 5 shows the SEM images of the surface and core of the thermal simulation sample under heat inputs of 300, 400 and 500 kJ/cm. For the surface samples, at 300 kJ/cm, the microstructure is mainly polygonal ferrite (PF) and pearlite (P) distributed along the grain boundaries, while at 400 kJ/cm, the microstructure is mainly AF and PF with a small amount of P, and at 500 kJ/cm, it is mainly larger-volume PF and some P distributed within the grains. However, in the core samples, the tissue contained a small amount of M/A component at 300 kJ/cm, while the tissue composition at 400 and 500 kJ/cm was not much different from that at the surface. As a brittle phase, M/A, although it has relatively high strength, will seriously reduce the plasticity and toughness of the material. Therefore, the toughness of the 300 kJ/cm core sample is worse than that of the 500 kJ/cm heat input one.

Figure 5.

SEM images of surface (a–c) and core (d–f) specimens at heat inputs of 300 kJ/cm (a,d), 400 kJ/cm (b,e), and 500 kJ/cm (c,f).

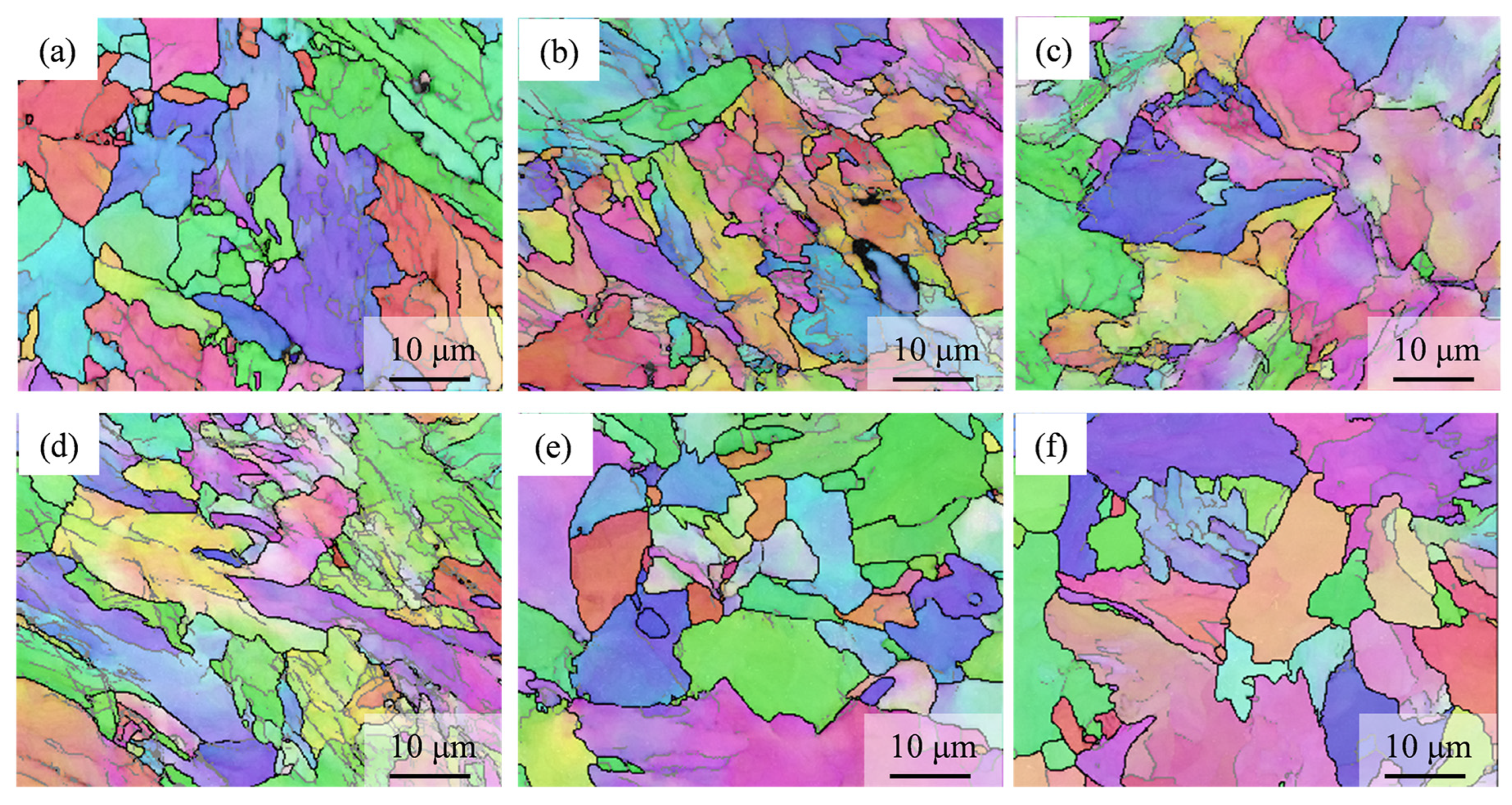

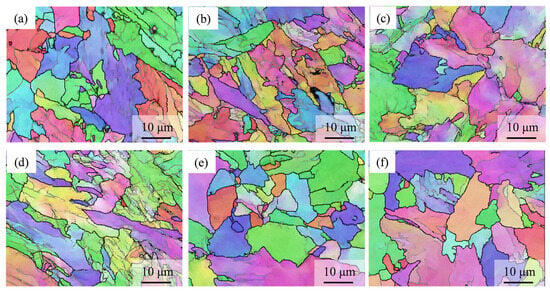

Studies have shown that an orientation angle of more than 45° can effectively prevent brittle cracking [23]. To explore the influence of this factor and to observe the crystal structure more intuitively, EBSD analysis was conducted on the samples. Figure 6 shows the inverse pole figures (IPF) of the surface and core thermal simulation specimens. From the IPF diagram, we can find that the microstructure of the 300 kJ/cm sample is highly uneven. The equivalent circular diameter of large grains can reach 30 μm, while that of small grains is only 2–3 μm. When the heat input was 400 kJ/cm, obvious AF could be observed in both the surface and core samples, and the grain size was smaller and more uniform compared to 500 kJ/cm. The grain morphology and size shown in the IPF diagram correspond to the trend of impact toughness.

Figure 6.

IPF maps of surface (a–c) and core (d–f) specimens at heat inputs of 300 kJ/cm (a,d), 400 kJ/cm (b,e), and 500 kJ/cm (c,f).

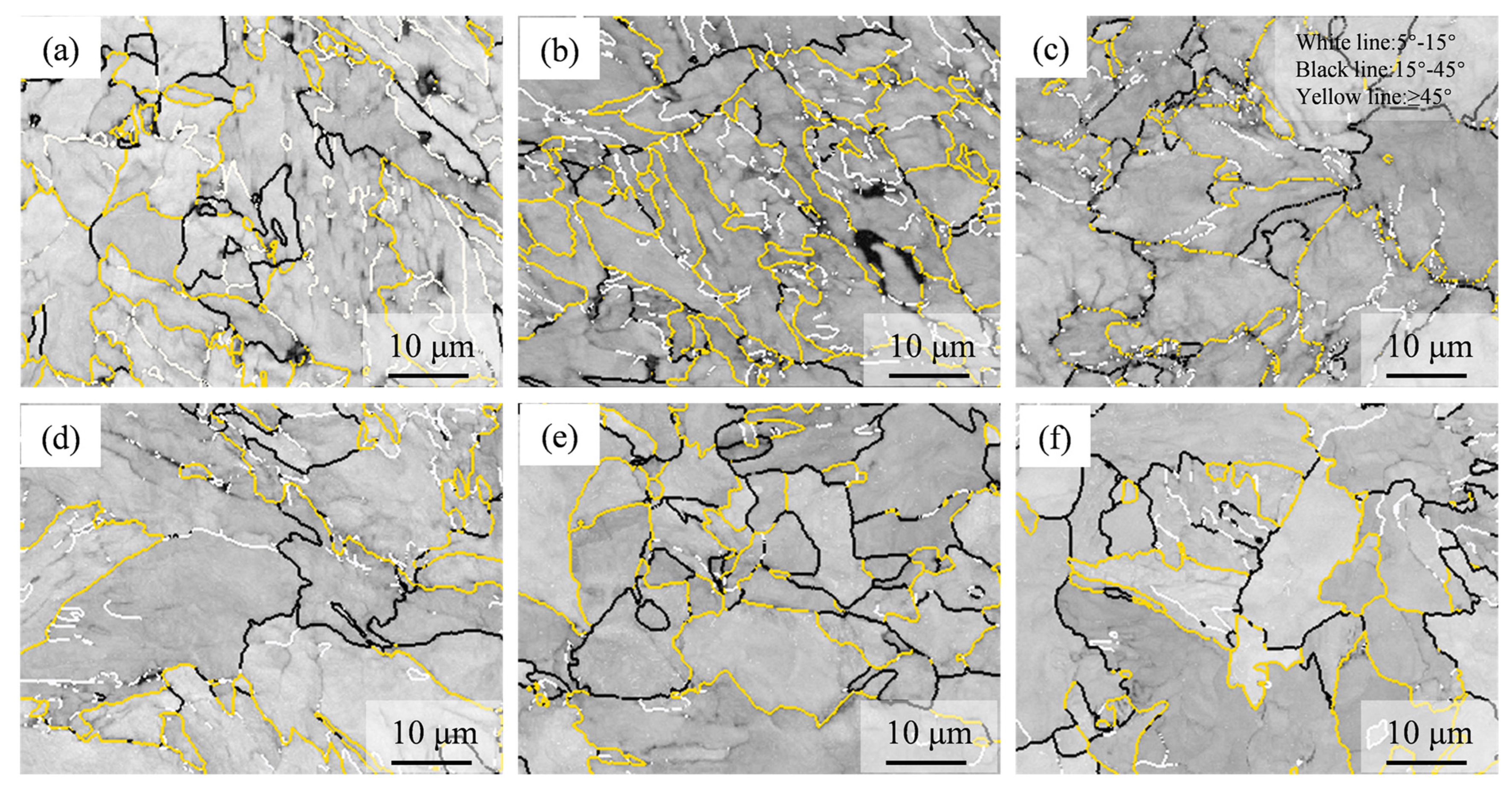

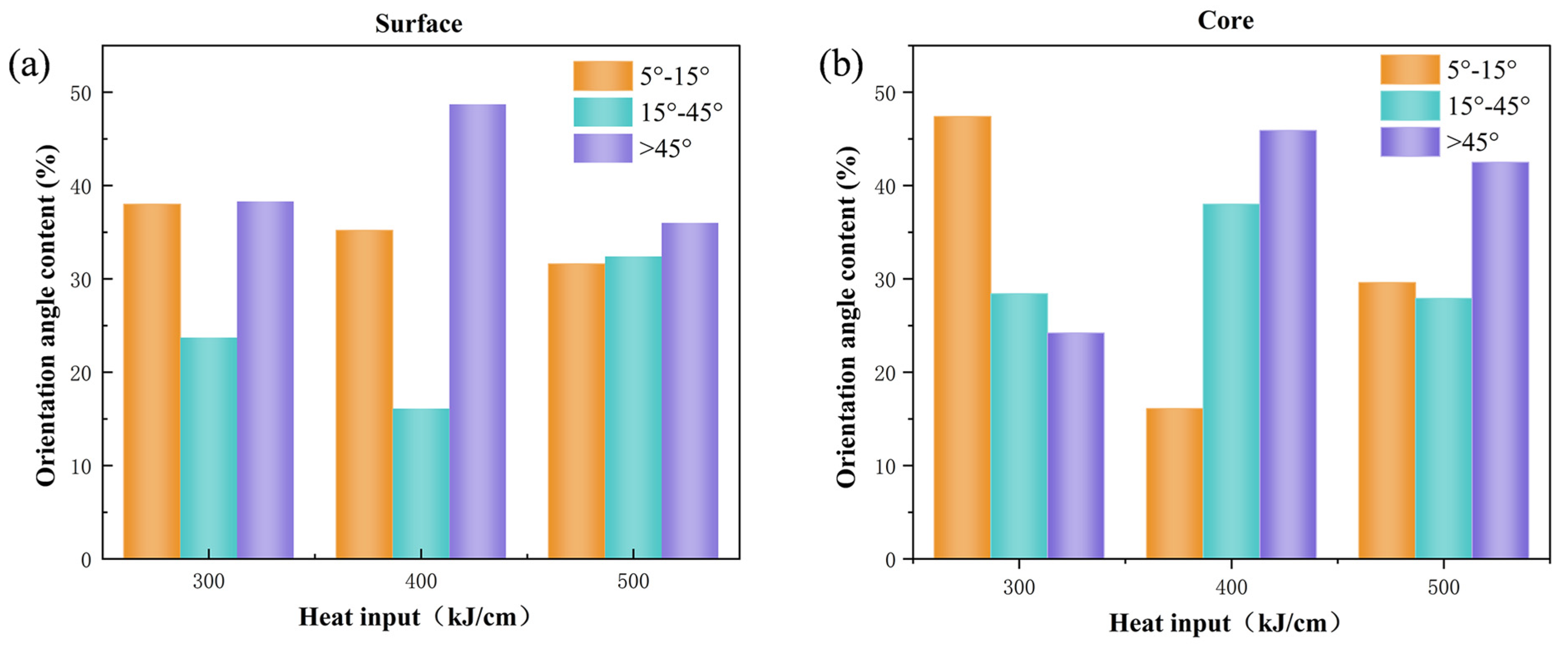

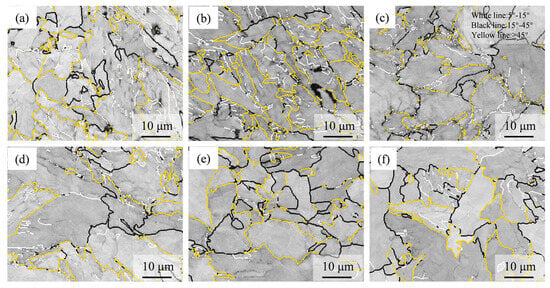

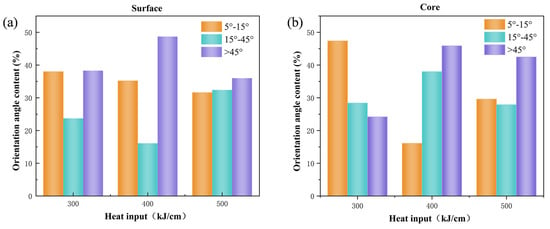

Figure 7 shows the grain boundary diagrams of the surface and core samples after thermal simulation. To clearly distinguish the grain boundaries of different orientations, lines of different colors are used to outline the grain boundaries of different orientations. Among them, the white line represents the grain boundaries with an orientation of 5–15°, the black line represents the grain boundaries with an orientation of 15–45°, and the yellow line represents the grain boundaries with an orientation exceeding 45°. The different grain boundary orientations are shown in Figure 8. By comparison, it can be found that the proportion of HAGBs (>45°) in the 400 kJ/cm sample is significantly higher, with 48.7% in the surface sample and 45.9% in the core sample. However, in the core samples, the HAGBs of the 300 kJ/cm samples was only 24.2%, and that of the 500 kJ/cm samples was 42.5%. In the surface samples, the HAGBs of the 300 kJ/cm sample was 38.3%, and that of the 500 kJ/cm sample was 36%. It is well known that HAGBs can effectively prevent the propagation of cracks and absorb the energy generated during fracture [24]. Based on the impact test data, it was found that the proportion of HAGBs was higher than that of the impact absorption energy in a one-to-one correspondence. When the heat input was 400 kJ/cm, the proportion of HAGBs was the highest, and at this time, the impact absorption energy of the sample was also the highest. The proportion of HAGBs in the 300 and 500 kJ/cm specimens also corresponds to the results of the impact test.

Figure 7.

Grain boundary maps of surface (a–c) and core (d–f) specimens at heat inputs of 300 kJ/cm (a,d), 400 kJ/cm (b,e), and 500 kJ/cm (c,f).

Figure 8.

Proportion of grain boundary misorientation angles for (a) surface and (b) core specimens under different heat inputs.

4. Conclusions

This investigation systematically examines the influence of welding heat input on the microstructural development and consequent low-temperature impact toughness of the CGHAZ in EH36-grade marine steel, employing thermal simulation and multi-scale characterization techniques. The principal conclusions derived from the experimental results and analysis are summarized as follows:

- The low-temperature (−40 °C) impact toughness of the simulated CGHAZ in EH36 steel exhibits a non-monotonic dependence on welding heat input. With increasing heat input from 300 kJ/cm to 500 kJ/cm, the impact absorption energy for both surface and core locations demonstrates a clear trend of initial increase, reaching a maximum, followed by a subsequent decrease. The best low-temperature impact toughness can be obtained when the heat input is 400 kJ/cm.

- Under the heat input of 400 kJ/cm, AF is generated in the simulated CGHAZ. AF has a “locking” or “interlocking” structural form. Through the synergistic effect of fine-grained strengthening and microstructure interlocking mechanisms, it effectively hinders the development of cracks, thereby significantly enhancing the material’s resistance to brittle fracture.

- EBSD analysis reveals that the specimen subjected to the 400 kJ/cm thermal cycle possesses the highest proportion of HAGBs compared to those subjected to the 300 kJ/cm and 500 kJ/cm cycles. These HAGBs form an extensive network that acts as a potent barrier to crack propagation, effectively absorbing fracture energy and promoting crack deflection and arrest. The quantified fraction of HAGBs shows a direct positive correlation with the measured impact energy, establishing a fundamental microstructural rationale for the observed mechanical behavior.

Practical implications: For the industrial welding of EH36 steel, a heat input of approximately 400 kJ/cm is recommended to achieve an optimal balance between welding efficiency and joint toughness. Heat inputs significantly above or below this value may reduce low-temperature performance, particularly in the core region. Further work should explore the effects of welding procedure variations and post-weld treatments to expand the operational window for high heat input welding in marine applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G. and P.Z.; methodology, Y.Z. and L.Z.; software, X.W.; validation, Z.L. and P.Z.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, Q.G. and G.S.; resources, L.Z., Q.G. and X.W.; data curation, Z.L.; writing-original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, P.Z., F.G. and Y.Z.; visualization, G.S. and L.Z.; supervision, X.W.; project administration, F.G.; funding acquisition, F.G. and Q.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Foundation of Department of Natural Resources of Guangdong [Grant No. (2024) 24].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Qunye Gao was employed by Yangjiang Jianheng Intelligent Equipment Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Shi, J.; Pang, Q.; Li, W.; Xiang, Z.; Qi, H. Evolution of Inclusions in DH36 Grade Ship Plate Steel during High Heat Input Welding. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; An, T.; Cao, Z.; Zuo, Y.; Ma, C.; Kang, J. Effect of Heat Input on Microstructure, Variant Pairing, and Impact Toughness of CGHAZ in 1000 MPa-Grade Marine Engineering Steel. Structures 2025, 77, 109139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, G.; Zeng, X.; Wei, K. Single-Pass High-Power Laser-Arc Hybrid Welding of Thick Stainless Steel Clad Plates: Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 5733–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Jing, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y. Prediction and Optimization Method for Welding Quality of Components in Ship Construction. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Xie, Z.; Shang, C.; Liu, Z. Crystallographic Study on Microstructure Evolution and Mechanical Properties of Coarse Grained Heat Affected Zone of a 500 MPa Grade Wind Power Steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 3921–3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.-S.; Park, K.-T.; Lee, C.-H.; Chang, K.-H.; Van Do, V.N. Low Temperature Impact Toughness of Structural Steel Welds with Different Welding Processes. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2015, 19, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Y. Erosion-Corrosion Performance of EH36 Steel Under Sand Impacts of Different Particle Sizes. Acta Metall. Sin. 2023, 59, 893–904. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Gouripeddi, R.; Facelli, J.C. Human Activity Pattern Implications for Modeling SARS-CoV-2 Transmission. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 199, 105896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, W.; Philip, B.; Zhenying, X.; Junfeng, W. Study on Fatigue Crack Growth Performance of EH36 Weldments by Laser Shock Processing. Surf. Interfaces 2019, 15, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-J.; Lee, K.; Cerik, B.C.; Choung, J. Comparative Study on Various Ductile Fracture Models for Marine Structural Steel EH36. J. Ocean Eng. Technol. 2019, 33, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, W.; Xiao, G.; Chen, K.; Zhang, H.; Guo, N.; Xu, L. Impact of Microstructure Evolution on the Corrosion Behaviour of the Ti–6Al–4V Alloy Welded Joint Using High-Frequency Pulse Wave Laser. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 4300–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.W.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Z.J.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Z.F. Forecasting Low-Cycle Fatigue Performance of Twinning-Induced Plasticity Steels: Difficulty and Attempt. Met. Mater. Trans. A 2017, 48, 5833–5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippold, J.C.; Kotecki, D.J. Welding Metallurgy and Weldability of Stainless Steels; Wiley-Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Pang, Q.; Li, W.; Bian, S. Effect of High Welding Heat Input on the Microstructure and Low-Temperature Toughness of Heat Affected Zone in Magnesium-Treated EH36 Steel. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.K.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, F.J.; Dai, K.S.; Zai, X.; Yang, X.; Chen, B.J. Effect of Heat Input on Cryogenic Toughness of 316LN Austenitic Stainless Steel NG-MAG Welding Joints with Large Thickness. Mater. Des. 2015, 86, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y. Effect of Mg Addition on Formation of Intragranular Acicular Ferrite in Heat-Affected Zone of Steel Plate after High-Heat-Input Welding. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2018, 25, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadeshia, H.K.D.H. Bainite in Steels: Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Junda, W.; Yun, G.; Hongwei, M. Strength and Impact Toughness of Q690CFD Welded Joints under Varied Heat Input. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2026, 236, 109986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kasyap, P.; Pandey, C.; Basu, B.; Nath, S.K. Role of Heat Inputs on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties in Coarse-Grained Heat-Affected Zone of Bainitic Steel. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2021, 35, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sharma, A.; Pandey, C.; Basu, B.; Nath, S.K. Impact of Subsequent Pass Weld Thermal Cycles on First-Pass Coarse Grain Heat-Affected Zone’s Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Naval Bainitic Steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 31, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rykalin, N.N. Calculation of Heat Processes in Welding. U.S.S.R. 1960. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2152/14232 (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Yang, J.R.; Bhadeshia, H.K.D.H. Acicular Ferrite Transformation in Alloy-Steel Weld Metals. J. Mater. Sci. 1991, 26, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, T.A.; Pourazizi, R.; Ohaeri, E.; Szpunar, J.; Zhang, J.; Qu, J. Investigation of the Hydrogen Induced Cracking Behaviour of API 5L X65 Pipeline Steel. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 17671–17684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourgues, A.-F.; Flower, H.M.; Lindley, T.C. Electron Backscattering Diffraction Study of Acicular Ferrite, Bainite, and Martensite Steel Microstructures. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2000, 16, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.