Abstract

In the aerospace field, the BT25y titanium alloy is recommended as a candidate material for manufacturing compressor discs and rotor blades of aircraft engines. The influence of hot deformation parameters on the microstructural evolution, recrystallization softening, and globularization mechanism of the BT25y alloy with an initial lamellar structure was studied. Furthermore, the coupling relationship between dynamic recrystallization and lamellar globularization was explored by means of EBSD, SEM, and TEM techniques. The experiment results indicate that the characteristics of initial lamellar α, α/α sub-grain boundaries within α lamellae, and the α/β phase boundary show significant variations due to the formation of equiaxed α grains during hot deformation. As the strain rate increases, the recrystallization mechanism of α phase gradually shifts from CDRX softening characterized by sub-grain evolution and lamellae fracture, to DDRX softening characterized by grain boundary arching and sub-grain boundary bridging. As the deformation temperature increases, the intense thermal activation promotes the accumulation of distortion storage energy, providing enhanced driving force for the occurrence of dynamic recrystallization. The research results will contribute to a deeper understanding of the relationship between dynamic recrystallization and lamellar globularization, providing theoretical guidance for the deformation process optimization and mechanical property control of the BT25y alloy.

1. Introduction

In the contemporary aviation industry, it is imperative to adopt high-strength materials to effectively improve the thrust-to-weight ratio of aircraft engines. Titanium alloys are becoming increasingly widely used in the aerospace industry due to their low density, high specific strength, good corrosion resistance, and high creep strength [1]. The BT25y alloy belongs to the high-strength martensitic titanium alloy serving in high temperatures, with a nominal composition of Ti-6.5Al-2Sn-4Zr-4Mo-1W-0.2Si and excellent comprehensive mechanical properties [2]. In recent years, it has received widespread attention globally due to its recommendation for manufacturing the dual-performance integral blade for aircraft engines operating in the temperature range of 450–550 °C (with a lamellar structure at the edge and an equiaxed structure at the core) [3]. So, precisely controlling the microstructure characteristics of various parts of the dual-performance integral blade to obtain a lamellar structure with favorable high-temperature endurance, creep and fatigue crack propagation resistance at the edge of the blade, and an equiaxed structure with good yield strength, tensile strength, and low cycle fatigue performance at the core of the blade is the key technical problem that needs to be urgently solved during the hot deformation of the BT25y alloy.

During the hot deformation process of metallic materials, dynamic recrystallization (DRX), as an important microstructural evolution behavior, not only affects the microstructure characteristics but also has a significant effect on the mechanical properties of materials [4,5]. Zhu et al. [6] studied the hot deformation behavior of the Ti-B25 high-strength titanium alloy used for naval antenna tubes. They found that deformation temperature and strain rate have a notable impact on the microstructural evolution of the Ti-B25 alloy, and a higher deformation temperature promotes the occurrence of continuous dynamic recrystallization (CDRX). Li et al. [7] investigated the relationship between softening mechanisms and deformation temperatures of the TC32 titanium alloy and found that dynamic recovery (DRV) dominates in the high-temperature deformation, and DRX behavior plays a major role at low temperatures. Lu et al. [8] analyzed the microstructural evolution of the Ti-6Al-3Nb-2Zr-1Mo alloy during hot deformation and found that both CDRX and discontinuous dynamic recrystallization (DDRX) softening mechanisms act simultaneously at lower temperatures below the β phase transition temperature. Additionally, increasing the deformation temperature promotes the softening mechanism, transforming from CDRX behavior to DDRX behavior. Yu et al. [9] studied the dynamic softening behavior of the TC17 alloy with an initial bimodal structure during high-strain-rate deformation and elucidated the influence of different α morphologies on the DRX behavior of the β matrix. The results showed that the equiaxed α phase has a much more significant effect on the DRX behavior of the β phase than that of lamellar α. Moreover, the β phase mainly undergoes CDRX softening at low temperatures and gradually transforms from CDRX to geometric dynamic recrystallization (GDRX) as plastic deformation goes on at high temperatures. In conclusion, different types of titanium alloys present obviously distinctive softening behaviors, even at similar deformation temperatures and strain rate levels. However, the dynamic softening behavior of the BT25y alloy with an initial lamellar structure during hot deformation and the dominant softening mechanism corresponding to different deformation conditions are still unclear. Therefore, the dynamic softening behavior and its influence on the complex microstructure characteristics of the BT25y alloy with initial lamellar structure are investigated by means of isothermal compression and microstructure characterization in this study.

The globularization of lamellar α is also an evolutionary behavior that significantly affects the microstructure characteristics and mechanical properties of titanium alloys during high-temperature deformation. Generally, the α phase in titanium alloys exists in different forms, such as lath, needle, or equiaxed morphology. The morphological evolution of the α phase directly or indirectly affects the mechanical properties of titanium alloys. The lamellar structure with basketweave distribution presents good fracture toughness, high-temperature durability, and creep performance, but it has poor tensile plasticity and fatigue strength. While the presence of equiaxed or nearly globular α can improve the tensile property and low-cycle fatigue performance, it also reduces the crack propagation resistance [10,11]. Therefore, it is of great significance to study the globularization process and regulatory strategy of lamellar α. Bai et al. [12] systematically studied the globularization mechanism of a basketweave structure in the Ti-25Zr-4Al-1.5Mn alloy with different rolling temperatures and its influence on the mechanical properties. They found that an appropriate deformation temperature can optimize the content of equiaxed α and sub-grains in the microstructure, thus exhibiting excellent plasticity apart from high yield strength. Bruna et al. [13] investigated the globularization crystallography and dynamic phase evolution during thermomechanical processing of the Ti-6Al-4V alloy. They found that dynamic globularization was accompanied by randomization and loss of the Burgers orientation relationship between the α and β phases, resulting in texture weakening and property improvement. Lin et al. [14] studied the globularization behavior of the α phase and DRX softening of the β phase for the Ti-55511 alloy hot compressed in the α + β phase region and found that the extensive formation of equiaxed α from lamellar globularization can promote the rapid occurrence of DRX softening in the β matrix. Li et al. [15] studied the hot deformation behavior of the Ti-10V-1Fe-3Al and Ti-10V-2Cr-3Al alloys with an initial lamellar structure. The results showed that the deformation behavior in the α + β phase region was controlled by the kinking or globularization of lamellar α, while the softening mechanism in the β phase region was mainly DRV or DRX behaviors. Therefore, the dynamic globularization of lamellar α experiences complex evolution of grain morphology and crystal orientation, which has a significant effect on the softening behavior of the β matrix and thus influences the microstructure constitution of titanium alloys. However, the globularization rule and in-depth mechanism of the BT25y alloy with an initial lamellar structure during hot deformation are still unclear. The coupling relationship between dynamic globularization and DRX behavior still needs to be clarified. Currently, it is still impossible to achieve precise control over the microstructural evolution of the BT25y alloy with an initial lamellar structure.

With the rapid development of electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) technology, the accuracy and efficiency of microstructure analysis have been significantly improved. Characterizing the microstructural evolution of titanium alloys during hot deformation by means of electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) analysis can provide insight into the underlying regulatory mechanisms that affect the complex microstructure constitution. Therefore, EBSD technology combined with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observation was adopted to systematically identify the recrystallization mechanism of the α phase under different deformation conditions, to further explore the relationship between the recrystallization behavior of the β matrix and dynamic globularization of lamellar α, and to figure out the intrinsic dependency between the dynamic globularization and recrystallization mechanism of lamellar α.

2. Materials and Experimental Procedures

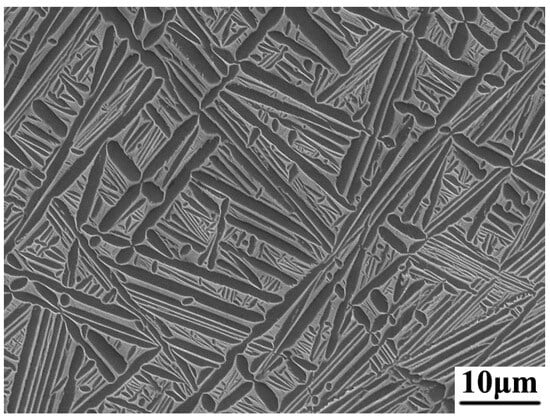

The raw material used in this study is a supplied BT25y rod blank, with a chemical composition of 6.44Al, 3.94Mo, 3.62Zr, 1.68Sn, 0.58W, 0.22Si, 0.09O, 0.046C, 0.01N, and 0.001H, and the remainder being Ti. The phase transition temperature was measured by the metallographic method at 965 °C. In order to obtain a lamellar structure, the original rod blank was first processed into short rods with dimensions of 15 mm × 100 mm. Next, the rods were annealed at 995 °C in the β single-phase region for 30 min and air-cooled to obtain the initial microstructure, as shown in Figure 1. The microstructure is entirely composed of a β-transformed structure with continuous prior grain boundaries and disorderly interwoven lamellar α precipitates on the β matrix. The lamellar α owns a large aspect ratio and a straight α/β phase boundary with the surrounding β matrix. Finally, several cylindrical specimens with dimensions of 10 mm × 15 mm were cut along the outer circumference of the short rod for isothermal compression.

Figure 1.

The initial microstructure of the BT25y alloy used in this experiment [16].

The isothermal compression experiment was conducted on the Gleeble-3500 thermal simulation machine (Dynamic Systems Inc., Poestenkill, NY, USA). Before isothermal compression, each group of specimens is heated at a rate of 10 °C/s to the deformation temperature and held for 5 min to ensure uniform temperature distribution in all parts of the specimen. Four sets of deformation temperatures, including 850 °C, 880 °C, 910 °C, and 940 °C, and four sets of strain rates, including 0.001 s−1, 0.01 s−1, 0.1 s−1, and 1 s−1, were set up in this study. All the deformation amounts were controlled at 60%. Throughout the deformation, argon gas was adopted to prevent the specimen from oxidizing under high temperatures. Once the isothermal compression was completed, the specimen was immediately quenched with water to room temperature for subsequent microstructure analysis. Then, the specimen was cut in half along the central axis and polished with the standard metallographic method. Etching was performed with a mixed solution of 3% HF:6% HNO3:91% H2O for SEM and 6% perchloric acid:30% n-butanol:64% methanol for EBSD, respectively. TEM samples were prepared through two-jet thinning with a mixed solution of 6% perchloric acid:34% n-butanol:60% methanol. The microstructure characteristics, such as phase composition, grain orientation, substructure morphology, recrystallization content, and texture distribution, were obtained through SEM, TEM, and EBSD analysis, which can be further used to analyze the microstructural evolution and corresponding regulatory mechanism under different hot deformation conditions. In this study, a Tescan MIRA3 field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic) was used for microstructure observation, a Tecnai F30 G2 field emission transmission electron microscope (TEM) (FEI, Hillsboro, Oregon, USA)was used for substructure characterization, and a NordlysMax EBSD detector (Oxford Instruments, Oxford, UK) was installed on the SEM for grain orientation, recrystallization content and texture analysis.

3. Results

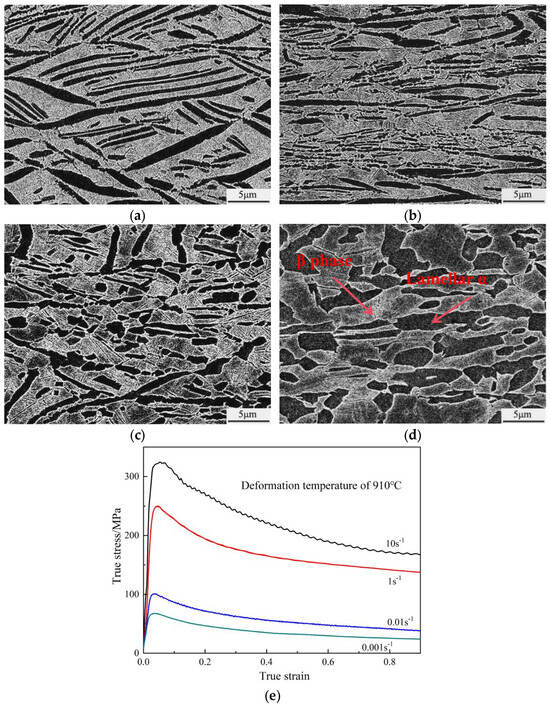

3.1. The Microstructural Evolution with Strain Rate

Figure 2 shows the microstructure of the BT25y alloy with an initial lamellar structure corresponding to different strain rates and the same deformation temperature of 910 °C. It can be seen from Figure 2a that when deformed at a high strain rate of 10 s−1, the microstructure characteristics present little difference with the original microstructure before hot deformation, except that some coarse lamellar α whose longitudinal axis tilted with an angle of 0~20° to the vertical compression direction becomes kinked. Part of the phase boundaries between the initial lamellar α and the β matrix are no longer straight contours, but present a serrated morphology. As the strain rate decreases to 1 s−1, slender lamellar α with small width preferably suffers dynamic globularization, thus a certain number of small equiaxed α grains can be observed on the β matrix. While coarse lamellar α with thick width still remains in the microstructure. When the strain rate is further reduced to 0.01 s−1, a large number of equiaxed or nearly globular α grains can be seen in Figure 2c. According to Table 1, the corresponding globularization rate of lamellar α is 63.1%, indicating that deformation at a low strain rate can promote the occurrence of dynamic globularization. The residual α lamellae get decreased in content and increased in width, which present obvious kinking in local areas. At the kinking sites, thermal grooves can be observed wedging from the α/β phase boundary towards the inside of lamellar α along the width direction [17,18]. As can be seen from Figure 2d, the microstructure is composed of quantities of nearly equiaxed α grains and short rod-like α grains when the strain rate decreases to 0.001 s−1. However, a small amount of original lamellar α has not been completely broken with severely kinked morphology, resulting in a considerable number of thermal grooves on the α/β phase boundaries. In addition, due to the prolonged high-temperature residence time, both initial lamellar α and the newly formed equiaxed α coarsen significantly. Therefore, the diameter of equiaxed α and the width of lamellar α in the microstructure corresponding to a low strain rate of 0.001 s−1 are obviously higher than those of other strain rates. Figure 2e presents the true stress–strain curves corresponding to different strain rates. As the strain rate increases from 0.001 s−1 to 10 s−1, the flow stress rises significantly. When deformed at a high strain rate, the dislocation multiplication rate exceeds the dislocation rearrangement and annihilation rates, thus work hardening dominates. When deformed at a low strain rate, it can provide more time for the occurrence of dynamic softening behaviors like DRV and DRX, resulting in a decrease in the flow stress.

Figure 2.

Microstructure corresponding to the deformation temperature of 910 °C and different strain rates of (a) 10 s−1; (b) 1 s−1; (c) 0.01 s−1; and (d) 0. 001 s−1; (e) corresponding true stress–strain curves.

Table 1.

Globularization rate of lamellar α under different deformation conditions.

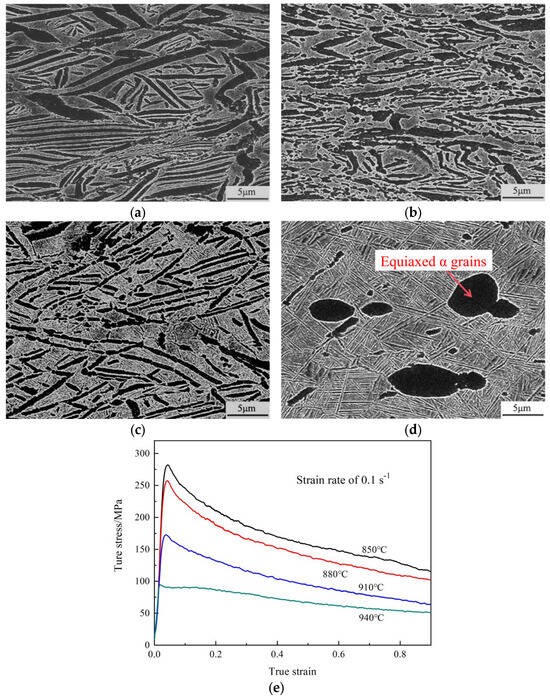

3.2. The Microstructural Evolution with Deformation Temperature

Figure 3 shows the microstructure of the BT25y alloy corresponding to the same strain rate of 0.1 s−1 and different deformation temperatures. By comparing the four types of microstructures, it can be found that when deformed at temperatures below the phase transition temperature, the content of primary α decreases due to the phase transformation of α → β, while the globularization rate of lamellar α gradually increases as the deformation temperature increases. It can be seen in Figure 3a that when deformed at a low temperature of 850 °C in the α + β phase region, the atomic diffusion and interface migration are hindered, thus a large number of severely kinked coarse lamellar α remains in the microstructure. The volume fraction of equiaxed α grains obtained through dynamic globularization is accordingly limited. When the deformation temperature rises to 880 °C, the kinking sites of lamellar α become fracture sources, which contribute to the increase in the globularization rate of lamellar α. The residual α lamellae are flattened along a direction approximately perpendicular to the compression axis. Additionally, the α/β phase boundaries present a serrated contour with a large number of thermal grooves. As the deformation temperature rises to 910 °C, the total content of the α phase decreases due to the phase transformation of α → β, while the remaining lamellar α has not been significantly coarsened. Due to enhanced atomic diffusion and boundary migration under high temperature, a large number of α lamellae disintegrate and fracture into short rod-like α or nearly globular α grains. When the deformation temperature reaches 940 °C, the primary lamellar α suffers sufficient dynamic globularization and transforms into globular or elliptical α grains. Almost no coarse α lamellae can be observed in the microstructure, as shown in Figure 3d. In addition, the primary α grains gradually dissolve and transform into the β phase under high temperatures, resulting in a significant decrease in the content of the α phase. As can be seen from Figure 3e, both the peak stress and steady-state flow stress decrease significantly as the temperature increases from 850 °C to 940 °C. This phenomenon can be attributed to two primary factors. Firstly, the enhancement of thermal activation contributes to the accumulation of distortion storage energy, which provides a driving force for the occurrence of DRV and DRX softening. Secondly, elevated temperature promotes the α → β phase transformation, which leads to an increase in the amount of the ductile β phase and decrease in the deformation resistance.

Figure 3.

Microstructure corresponding to the strain rate of 0.1 s−1 and different deformation temperatures of (a) 850 °C; (b) 880 °C; (c) 910 °C; and (d) 940 °C; (e) corresponding true stress–strain curves.

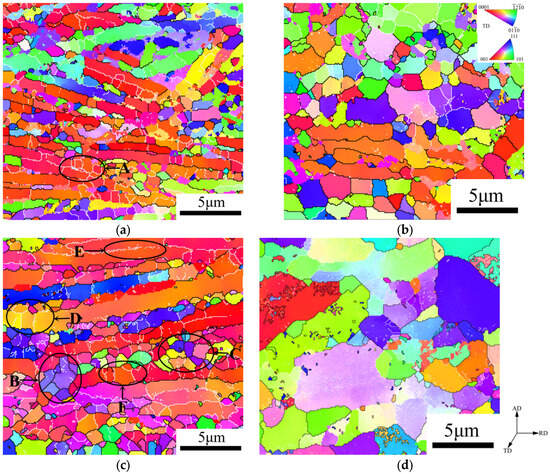

Figure 4a,b show the IPF plots of the BT25y alloy at different strain rates and the same deformation temperature of 910 °C. In the figure, the black line represents high-angle grain boundaries (HAGBs), while the white line represents low-angle grain boundaries (LAGBs). It can be seen that there are significant differences in grain morphology, grain size, and sub-grain content between microstructures corresponding to different strain rates. As shown in Figure 4a, when deformed at a strain rate of 0.1 s−1, a large amount of initial lamellar α is flattened along a direction approximately parallel to the horizontal direction, and equiaxed α with a very small grain size can be observed in local regions. Since dislocations proliferate rapidly under high strain rates, the distortion storage energy increases significantly and drives the occurrence of DRV softening, leading to the rearrangement of dislocations within lamellar α and the formation of sub-grain boundaries to a large degree, as indicated by Arrow A [19]. According to Table 1, the corresponding proportion of LAGBs is as high as 39.9%, occupying the highest value among the four deformation parameters. Due to the limited deformation time, although a large number of LAGBs generate within lamellar α, it cannot provide sufficient time for most sub-grain boundaries to gradually evolve into high-angle grain boundaries, failing to achieve the separation and fracture of initial lamellar α. Therefore, the globularization rate of lamellar structure under high strain rates is relatively lower. As the strain rate drops to 0.01 s−1, most of the lamellar α has undergone dynamic globularization, and a large number of equiaxed or nearly globular α grains with average sizes of about 1.92 μm can be observed in the microstructure. Thus, only a small amount of LAGBs can be observed in the remaining lamellar α, which accounts for about 29.3%, according to Table 1.

Figure 4.

The orientation distribution maps corresponding to different deformation temperatures and strain rates of (a) 910 °C/0.1 s−1; (b) 910 °C/0.01 s−1; (c) 880 °C/0.1 s−1; and (d) 880 °C/0.001 s−1.

Figure 4c,d show the IPF plots of the BT25y alloy at different strain rates and the same deformation temperature of 880 °C. By comparing Figure 4c with Figure 4a, it can be observed that necklace-like structures composed of a series of small equiaxed α grains are generated along the grain boundaries of initial lamellar α as the deformation temperature decreases to 880 °C. It is worth noting that some equiaxed grains within these necklace-like structures have the same or similar orientations as adjacent grains, as indicated by Arrow B in Figure 4c. The other equiaxed grains present a significant misorientation with adjacent grains due to the different shear stress levels experienced by various parts of the primary lamellar α during the initial deformation stage, as indicated by Arrow C. The parts that experienced higher stress participate in the plastic deformation preferentially and become severely kinked first [20]. Dislocations proliferate, rearrange into sub-grain boundaries, and further transform into large-angle grain boundaries, resulting in significant orientation differences between adjacent grains. As the kinking degree of lamellar α increases, the previously less stressed parts may rotate to a favorable orientation and are able to participate in the plastic deformation in the subsequent deformation stage. Similarly, sub-grain boundaries form in these areas under the effect of dislocation rearrangement and polygonization. Therefore, the same or similar orientations can be observed among adjacent equiaxed α grains. Another notable phenomenon is that a large number of sub-grain boundaries generate in the directions either approximately parallel or perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of lamellar α, as indicated by Arrow D. Nevertheless, some sub-grain boundaries do not initiate from the α/β phase boundaries with higher distortion energy, but rather preferentially initiate from the interior of lamellar α, as indicated by Arrow E. These sub-grain boundaries intersect with each other, dividing the initial lamellar α into continuously distributed sub-grains with different sizes, as pointed by Arrow F. As the strain rate drops to 0.001 s−1, most of the initial α lamellae have already undergone complete dynamic globularization due to the long residence time at high temperatures. According to the statistics, the generated equiaxed α grains occupy about 71.9% of the total microstructure, which achieves the highest globularization rate among the four deformation parameters. Moreover, the newly formed equiaxed α grains suffer significant coarsening, with an average size of approximately 2.47 μm, which is obviously coarser than that of 880 °C/0.1 s−1.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Recrystallization Mechanism of Primary Lamellar α and the β Matrix

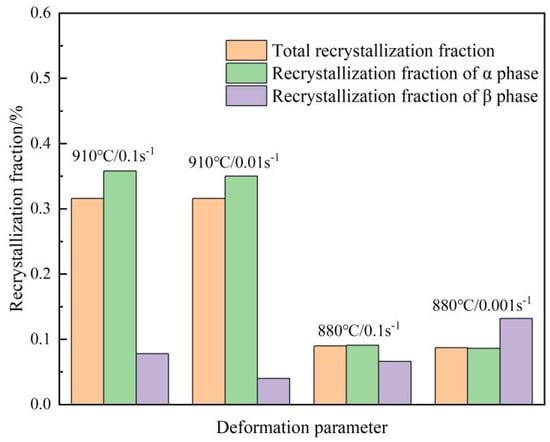

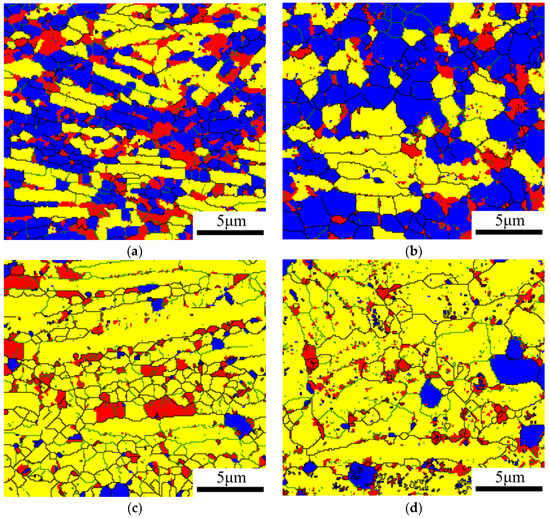

Through analyzing the statistical data in Figure 5, it can be concluded that the occurrence of DRX behavior is closely related to the strain rate and deformation temperature. As can be found in Figure 6, for the same strain rate, the volume fraction of DRX grains is significantly increased with elevated deformation temperature. Since the thermal activation effect and atomic diffusion ability are improved at high temperatures, the critical shear stress for the dislocation slip is reduced, and thus the number of activated slip systems increases, which promotes intense dislocation movement and interaction with each other to form dramatical dislocation entanglement, leading to the accumulation of distortion storage energy as the driving force for DRX softening [21]. Generally, the newly formed recrystallized grains are smaller in size than the initial lamellar α and are distributed more evenly, which can improve the strength and ductility of BT25y alloy under the effect of fine grain strengthening.

Figure 5.

Recrystallization fraction of α and β phases under different deformation conditions.

Figure 6.

Recrystallization distribution maps under different deformation conditions (blue, recrystallized grains; yellow, recovered grains; red, deformed grains): (a) 910 °C/0.1 s−1; (b) 910 °C/0.01 s−1; (c) 880 °C/0.1 s−1; (d) 880 °C/0.001 s−1.

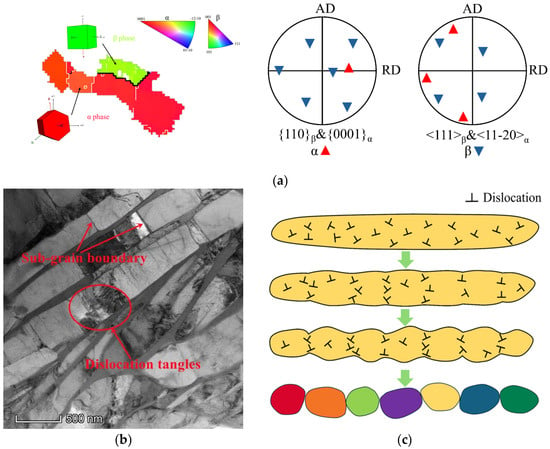

Additionally, it can be found in Figure 5 that the effect of the strain rate on the volume fraction of DRX grains in the α phase is not particularly significant compared to the deformation temperature. Nevertheless, the microstructural evolution varies with increasing strain rate. As Figure 7a shows, the crystallographic orientation of the initial lamellar α alters due to lamellar kinking during low-strain-rate deformation, resulting in a disruption of the BOR orientation relationship between lamellar α and its surrounding β matrix. Moreover, under the driving force of distortion storage energy accumulated at the kinking sites, a large number of dislocations proliferate and entangle within lamellar α [22]. These dislocations are rearranged through slip, climb, and cross-slip to form sub-grains with LAGBs during DRV softening, as shown in Figure 7b. Due to sufficient deformation time at a low strain rate, the LAGBs gradually transform into HAGBs through the absorption of dislocations and sub-grain rotation, resulting in the formation of new DRX grains. Meanwhile, the disintegration and fracture of lamellar α are synchronously achieved, transforming the initial lamellar α into small equiaxed α grains, as shown by the schematic diagram in Figure 7c. This process is mainly characterized by the evolution of sub-grain and fracture of lamellar α, which is consistent with the microstructural evolution characteristics of the CDRX mechanism [23]. Furthermore, it can be obtained from Table 1 that the proportion of LAGBs corresponding to low strain rates of 880 °C/0.001 s−1 and 910 °C/0.01 s−1 accounts for 31.8% and 29.3%, respectively, which is significantly lower than that corresponding to higher strain rates. As these LAGBs continuously absorb dislocations and transform into HAGBs during plastic deformation, the proportion of LAGBs decreases significantly, once again proving that the CDRX mechanism is the main softening behavior for low-strain-rate deformation.

Figure 7.

Microstructure characterization corresponding to the low strain rates of 0.01 s−1 and 0.001 s−1: (a) pole correspondence between kinking lamellar α and the surrounding β matrix; (b) dislocation and sub-grain boundary within α lamellae by TEM observation; (c) schematic diagram of the CDRX mechanism in lamellar α.

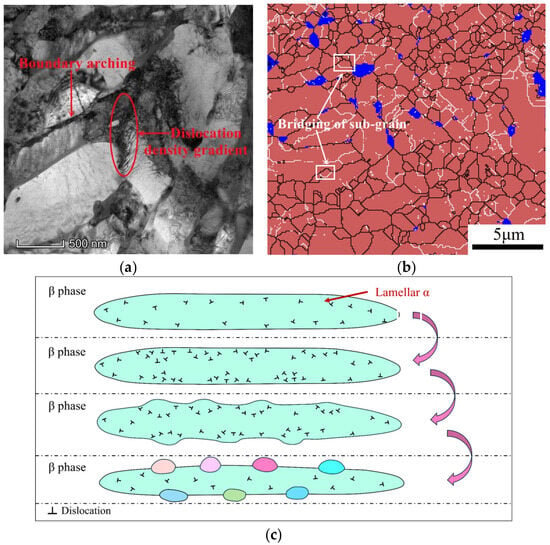

On the contrary, when the strain rate increases to 0.1 s−1, the content of LAGBs corresponding to deformation temperatures of 880 °C and 910 °C increases to 34% and 39.9%, respectively. Although deformation at high strain rates can promote rapid proliferation and rearrangement of dislocations into a large number of sub-grain boundaries within lamellar α, these sub-grain boundaries do not have sufficient time to continuously absorb dislocations and evolve into high-angle grain boundaries. As shown in Figure 8a, dislocations multiply rapidly and accumulate at the high-energy α/β phase boundary, presenting a significant dislocation density gradient along the direction perpendicular to the phase boundary. The presence of a dislocation density gradient leads to intensified non-uniform plastic deformation, which further contributes to the distribution of the strain gradient perpendicular to the α/β phase boundary. Thus, atoms migrate under the driving force of unevenly distributed distortion energy from the grain boundary of lamellar α to low-strain areas along the direction perpendicular to the α/β phase boundary to form arched grain boundaries, as indicated in Figure 8a, serving as slip steps to ensure the coordination of plastic deformation between adjacent grains. At the same time, dislocations accumulate near the grain boundaries and rearrange into sub-grain boundaries with small angles on the inner side of lamellar α, which act as a bridge to connect the two ends of the arched grain boundary together, forming a large number of completely or partially enclosed sub-grains at the α/β phase boundary, as shown in Figure 8b. Due to the driving force from boundary energy minimization, the curvature of arched grain boundaries continuously increases, which leads to migration of the arched grain boundaries towards areas far away from the curvature center. Meanwhile, the bridging sub-grain boundaries with low angles would continuously absorb dislocations and transform into HAGBs. Then, these early-formed arching grain boundaries and newly generated bridging grain boundaries would further propagate along the dislocation density gradient by continuously absorbing surrounding dislocations, ultimately transforming into newly undistorted equiaxed α grains, as shown by the schematic diagram in Figure 8c. This process is accompanied by the arching of grain boundaries and bridging of sub-grain boundaries, which are typical microstructural evolution characteristics of DDRX softening.

Figure 8.

Microstructure characterization corresponding to a high strain rate of 0.1 s−1: (a) dislocation density gradient perpendicular to the α/β phase boundary by TEM observation; (b) bridging of the sub-grain at the arched grain boundary; (c) schematic diagram of the DDRX mechanism.

Comparing Figure 7 with Figure 8, it can be found that the microstructural evolution from the separation and fracture of lamellar α along the α/α sub-grain boundaries to nucleation at the arched α/β phase boundaries is consistent with the transition from CDRX softening at low strain rates of 0.01 s−1 and 0.001 s−1 to DDRX softening at a high strain rate of 0.1 s−1 or larger. According to the statistical data in Figure 5, when deformed at a temperature of 910 °C, there is little difference in the volume fraction of recrystallized α grains for strain rates of 0.1 s−1 and 0.01 s−1. However, it can be observed from Figure 6 that the grain size of recrystallized α corresponding to the strain rate of 0.1 s−1 is significantly smaller than that of 0.01 s−1. As mentioned above, the CDRX mechanism dominating in low strain rate deformation is mainly characterized by the disintegration of lamellar α along the α/α sub-grain boundaries. During the disintegration and fracture process of lamellar α, there is sufficient time for substructure evolution and subsequent grain growth, resulting in a relatively larger size of recrystallized grains [24]. As the strain rate increases, the softening behavior shifts from the CDRX mechanism to the DDRX mechanism. DDRX grains originate from nucleation at the arched grain boundary, which requires a greater driving force to overcome the high nucleation energy barriers compared with CDRX softening [25]. Thus, the formation of new crystal nuclei calls for a certain incubation period, and the nucleation process is much more sluggish, which results in quite smaller DDRX grains. As a result, a significant difference exists in the grain size of equiaxed α obtained through the two DRX mechanisms corresponding to different strain rates.

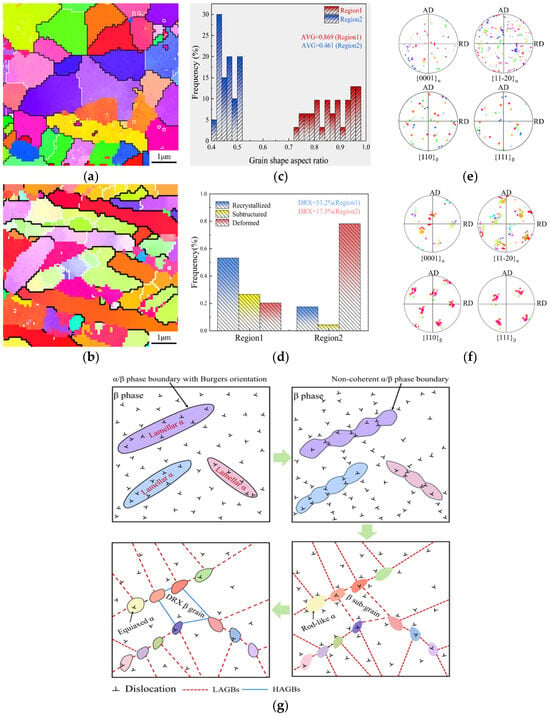

The previous studies on the recrystallization mechanism of titanium alloys mainly focus on the α phase, and studies on the recrystallization mechanism of the β matrix in α + β type titanium alloys are rarely involved. Figure 9 shows the EBSD analysis results of Regions 1 and 2 in Figure 2c and Figure 3c, respectively. It can be seen that the proportion of HAGBs and LAGBs in both the α phase and β phase is significantly different in Regions 1 and 2. Moreover, the grain morphology, crystallographic orientation, and sub-grain content in the α phase are also different from each other. The ratio of width to length was adopted to characterize the globularization rate of lamellar α in Figure 9c. The larger the width-to-length ratio of α phase, the higher the globularization rate of lamellar α. The volume fraction of DRX β grains was adopted in Figure 9d to characterize the DRX degree in the β phase. The results show that the average value of the width-to-length ratio of α phase is 0.869, and the volume fraction of DRX β grains is 53.2% for Region 1. The average value of the width-to-length ratio of α phase is 0.461, and the volume fraction of DRX β grains is 17.5% for Region 2. Obviously, the width-to-length ratio of α phase in Region 1 is higher than that of Region 2, so the initial lamellar α in Region 1 suffers more significant dynamic globularization. Similarly, the DRX fraction of β phase in Region 1 is higher than that of Region 2. For Region 2, more initial lamellar α remains in the microstructure, with a relatively smaller width-to-length ratio and lower globularization rate. Meanwhile, the DRX fraction is relatively lower in β phase, which is dominated by DRV softening. Therefore, it can be considered that the globularization rate of lamellar α and the DRX degree of β matrix present the same variation rule, namely, the higher globularization rate of lamellar α, the greater DRX degree of β phase. Figure 9e,f present the orientation relationship between the α phase and the β matrix in Region 1 and Region 2, respectively. As can be seen, the pole locations of the α and β phases in Region 1 are more dispersed, indicating that their orientation distributions are more random, and the Burgers relationship between these two phases is disrupted more severely. Thus, both the globularization rate of lamellar α and the DRX degree of β matrix are higher than those of Region 2. During plastic deformation, the kinking of initial lamellar α contributes to the variation in the crystallographic orientation and disruption of the Burgers orientation relationship between lamellar α and the β matrix, leading to the formation of a non-coherent α/β interface. The literature shows that non-coherent interfaces at the α/β phase boundary can effectively hinder the movement of dislocations [26]. A large number of dislocations accumulate and entangle at the α/β phase boundary, resulting in a sharp increase in the local stress and maintaining a high-energy state at the phase boundary. Driven by the strong stress field and high distortion energy, dislocations in the β phase rearrange to form β sub-grains near the α/β phase boundary. Moreover, as the globularization rate of lamellar α increases, the newly formed equiaxed α grains slide through the α/β phase boundary, increasing the misorientation of β sub-grains near the phase boundary and promoting the transformation of LAGBs into HAGBs, finally converting the β sub-grains into independently distributed recrystallized β grains, as shown in Figure 9g. Thus, recrystallized β grains preferentially nucleate at the α/β phase boundary. Actually, the evolution process conforms to the microstructure characteristics of CDRX softening. Therefore, it can be considered that the dynamic globularization of lamellar α can partly promote the CDRX softening of the β phase.

Figure 9.

EBSD analysis results of Regions 1 and 2: (a,b) IPF maps; (c) the width-to-length ratio of the α phase; (d) the volume fraction of DRX grains in the β phase; (e,f) pole figures of Regions 1 and 2; (g) schematic diagram of the DRX mechanism in the β phase at the α/β phase boundary.

When deformed under low strain rates, the initial lamellar α suffers significant dynamic globularization, and the crystallographic orientations of emerging equiaxed α are randomly distributed. The newly formed non-coherent α/β phase boundaries between the equiaxed α and β matrix can effectively hinder dislocation movement and provide sufficient distortion energy for the occurrence of DRX softening in the β phase near the phase boundaries [27]. While deformed at high strain rates, a large number of initial lamellar α still remains in the microstructure, as shown in Figure 4a,c. The remaining lamellar α and surrounding β matrix still maintain an approximate Burgers orientation relationship due to the limited globularization rate of lamellar α [28]. Dislocations can freely slip through the α/β phase boundary, which is not conducive to the pile-up, proliferation, and rearrangement of dislocations. Therefore, the generation of β sub-grains and transformation into β recrystallized grains are inhibited. Thus, the softening mechanism of β phase during high-strain-rate deformation is mainly DRV behavior rather than DRX behavior. The evolution of the β phase is also affected by the deformation temperature. When deformed at a low temperature of 880 °C, the volume fraction of β recrystallized grains is quite limited, especially at high strain rates. As the deformation temperature rises to 910 °C, the content of β phase increases due to the occurrence of the α → β phase transition. Additionally, the thermal activation effect is enhanced at high temperatures, providing more energy for atomic diffusion to accelerate dislocation climb and boundary movement, which eventually promotes the occurrence of DRX softening. Therefore, the content of β recrystallized grains increases with elevated deformation temperatures. In conclusion, the occurrence of DRX behavior in the β phase is significantly influenced by thermal activation related to the deformation temperature and lamellar globularization induced by the strain rate.

4.2. The Coupling Relationship of DRX Softening and Lamellar Globularization

When deformed at the temperature of 910 °C, a large number of equiaxed α grains are generated in the microstructure of 0.01 s−1, as shown in Figure 2c. However, the α phase corresponding to 0.1 s−1 is mostly presented in the form of long lamellae or short rods, and the content of equiaxed α grains is very limited, as shown in Figure 3c. Thus, it can be concluded that appropriately reducing the strain rate can promote the dynamic globularization of lamellar α. During hot deformation at a lower strain rate, it can provide sufficient time for the entanglement and rearrangement of dislocations into substructures within lamellar α. Furthermore, the α/α sub-grain boundaries continuously absorb dislocations and evolve into high-angle grain boundaries. Finally, the original lamellar α is separated and broken into small equiaxed α grains, resulting in the improvement of the globularization rate in the lamellar structure. Accordingly, the globularization process of lamellar α is highly consistent with CDRX softening characterized by sub-grain evolution and lamellar disintegration [29]. As can be seen in Figure 4b, the microstructure corresponding to 910 °C/0.01 s−1 is composed of a large number of small equiaxed α grains generated from the dynamic globularization of lamellar α. Coincidentally, the blue markings in Figure 6b indicate that these equiaxed grains are also products of DRX behavior, which can further confirm that the globularization process of lamellar α is accompanied by the occurrence of CDRX softening. As the strain rate increases, the softening behavior gradually shifts from the CDRX mechanism to the DDRX mechanism, so the dynamic globularization of lamellar α, dependent on CDRX softening, would also be inhibited. Therefore, although dislocations proliferate in large quantities in a short period of time at high strain rates, they cannot provide sufficient time for the evolution of the α/α sub-grain boundary and dynamic globularization of lamellar α.

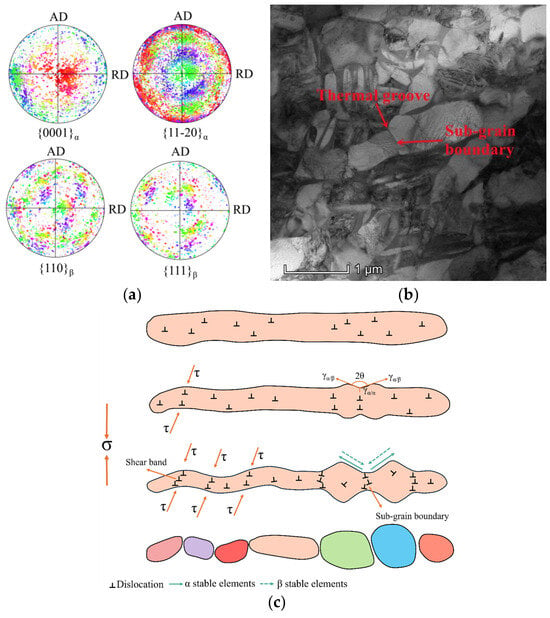

The evolution of the α/β phase boundary also has a significant effect on the dynamic globularization of lamellar α. As is well known, the phase boundary between the initial lamellar α and surrounding β matrix is generally presented in a straight contour, and the two phases usually maintain a Burgers orientation relationship [30]. The pole locations corresponding to the (0001) and (110) groups in the α phase and the (110) and (111) groups in the β phase shown in Figure 10a are dispersed, and the pole correspondence relationship between the two phases gradually disappears, indicating that the crystallographic orientations of the α phase and the β phase become much more random as the plastic deformation proceeds, and the Burgers relationship between lamellar α and the β matrix is disrupted. Therefore, when dislocations move from the interior of lamellar α to the α/β phase boundary, dislocations accumulate and pile up severely, which brings about a sharp increase in the distortion energy at the α/β phase boundary. Then, a large number of boundary atoms diffuse into the surrounding low-energy region, resulting in the alteration of atomic arrangement orientation on both sides of the α/β phase boundary and ultimately giving rise to the loss of interface coherency. According to previous studies [31,32], the loss of coherency at the α/β phase boundary leads to localized deformation within lamellar α, which results in the kinking of lamellar α at multiple sites and the formation of a serrated phase boundary contour. A large number of dislocations are generated at the kinking sites, which would further evolve into α/α sub-grain boundaries through glide, climb, and cross-slip. Meanwhile, some grain boundaries may slip under the effect of shear stress, contributing to the generation of shear bands, as shown in Figure 10c. The dihedral angle θ between these newly formed internal interfaces and neighboring α/β phase boundaries is very unstable [33]. In order to balance the interfacial energies between these internal interfaces and α/β boundaries, the dihedral angle θ would reduce spontaneously. Thus, thermal grooves generate at the junction of internal interfaces and α/β phase boundaries, as shown in Figure 10b. Then, α-stable elements would migrate from the α/α sub-grain boundary to neighboring α/β phase boundaries, while the β-stable elements diffuse in an opposite direction, resulting in the continuous wedge of the β phase into α lamellae along the α/α sub-grain boundary, as shown in Figure 10c. Once the β phase penetrates α lamellae, the initial lamellar α would be separated into several short rod-like or nearly equiaxed α grains. Then, these short rod-like α grains transform into small equiaxed α grains under the effect of terminal migration [34]. As a result, the dynamic globularization of lamellar α is achieved.

Figure 10.

Microstructural evolution corresponding to a low strain rate of 0.01 s−1/910 °C: (a) pole correspondence between (0001)α and (110)β, (110)α and (111)β; (b) thermal groove and sub-grain boundary observed by TEM; (c) schematic diagram of the globularization mechanism.

5. Conclusions

- During isothermal compression, the strain rate and deformation temperature have a significant effect on the microstructural evolution of the BT25y alloy. With the increase in deformation temperature, intense thermal activation promotes the accumulation of distortion storage energy, providing a driving force for DRX softening. As the strain rate decreases, it provides sufficient time for the formation of substructures by dislocation proliferation, entanglement, and rearrangement within lamellar α, evolution of LAGBs to HAGBs through continuous dislocation absorption, and disintegration of lamellar α into a series of small equiaxed α grains. As a result, the globularization rate of the lamellar structure increases, along with grain coarsening.

- The recrystallization mechanism of the BT25y alloy varies from CDRX softening characterized by the formation of sub-grain boundaries within lamellar α, wedging of the β phase along the α/α sub-grain boundaries, and the separation of lamellar α into small equiaxed α grains under a low strain rate (<0.1 s−1) to DDRX softening characterized by the arching of original grain boundaries and bridging of newly sub-grain boundaries to form new grains under a high strain rate (>0.1 s−1).

- The dynamic recrystallization of both the α and β phases is closely related to the globularization process of lamellar α. The dynamic globularization of lamellar α synchronously occurs with the CDRX behavior, while the DRX degree of the β phase is influenced by the content of equiaxed α grains generated from the dynamic globularization of lamellar α.

- The Burgers relationship between lamellar α and the β matrix is disrupted during hot deformation, leading to the loss of interface coherency at the α/β phase boundary and kinking of lamellar α with thermal grooves. Then, the β phase wedges into α lamellae from the thermal grooves and continuously propagates along the α/α sub-grain boundary, separating initial lamellar α into nearly equiaxed or rod-like α grains and finally resulting in the dynamic globularization of lamellar α.

Author Contributions

Writing—review and editing, X.Y. (Xuemei Yang) and X.Z.; investigation, X.Z., J.F. and B.Z.; formal analysis, C.W., Y.S. and J.W.; data curation, C.W. and J.W.; validation, B.Z. and Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F. and X.Y. (Xuemei Yang); supervision, X.Y. (Xuewei Yan); methodology, X.Y. (Xuewei Yan) and X.S.; conceptualization, X.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Henan Natural Science Foundation (No. 242300420359), the Henan Provincial Science and Technology Tackling Project (Nos. 242102230057 and 242102221028), the Key Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities in Henan Province (No. 24B430020), the Youth Research Fund in Zhengzhou University of Aeronautics (No. 24ZHQN01008), the Laboratory Open Program in Zhengzhou University of Aeronautics (No. ZHSK25-62), and the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students in Higher Educational Institutions in Henan Province (No. 202410485005).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Ning, Y.; Guo, H.; Li, H.; Yuan, S.; Xin, S. Microstructural evolution and mechanical property of isothermally forged BT25y titanium alloy with different double-annealing processes. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 745, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zeng, W.; Tian, F.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, Y. Modeling constitutive relationship of BT25 titanium alloy during hot deformation by artificial neural network. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2012, 21, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.X. Study on relation of structure and performance of BT25y titanium alloy finish forged bar. Titan. Ind. Prog. 2012, 29, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Tang, B.; Liu, D.; Wei, B.; Zhu, L.; Liu, R.; Kou, H.; Li, J. Dynamic recrystallization and hot processing map of Ti-48Al-2Cr-2Nb alloy during the hot deformation. Mater. Charact. 2021, 179, 111332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Khatirkar, R.; Singh, J. A review of microstructure and texture evolution during plastic deformation and heat treatment of β-Ti alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 899, 163242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Wang, B.; Wang, B.; Tian, Y. Dynamic phase transition and dynamic recrystallization of Ti-B25 high-strength titanium alloy during high-temperature deformation. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1018, 179188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, L.W.; Li, M.B.; Wang, X.N.; Shang, G.Q.; Zhu, Z.S. Characterization of hot deformation behavior of TC32 titanium alloy. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 474, 12045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Song, K.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Zhou, F.; Cao, Q.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, B. Investigation on microstructure and texture evolution of Ti-6Al-3Nb-2Zr-1Mo alloy during hot deformation. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 96520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhu, H.; Chen, J.; Xia, W.; Sun, Y.; Su, B.; Deng, Y.; Song, M. Dynamic recrystallization behavior and mechanism of bimodal TC17 titanium alloy during high strain rate hot compression. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Fu, M.; Zhan, M.; Lei, Z.; Li, Y. Deformation behavior and microstructure evolution of titanium alloys with lamellar microstructure in hot working process: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 39, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zeng, W.; Ma, H.; Zhou, D. Static globularization mechanism of Ti-17 alloy during heat treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 736, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.K.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Z.B.; Yang, R.D.; Zhang, S.Z.; Chen, T.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liang, S.X.; Liu, R.P. Strong and plastic near-α titanium alloy by Widmanstätten structure spheroidization. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 225, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegari, B.; Oliveira, J.P.; Coelho, R.S.; Brito, P.P.; Schell, N.; Soldera, F.; Mücklich, F.; Pinto, H.C. New aspects of globularization crystallography and dynamic phase evolution during thermomechanical processing of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 276, 125388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Xiao, Y.W.; Jiang, Y.Q.; Pang, G.D.; Li, H.B.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhou, K.C. Spheroidization and dynamic recrystallization mechanisms of Ti-55511 alloy with bimodal microstructures during hot compression in α+β region. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 782, 139282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ding, Z.L.; Zwaag, S. The modeling of the flow behavior below and above the two-phase region for two newly developed meta-stable β titanium alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2021, 23, 1901552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.M.; Guo, H.Z.; Yao, Z.K.; Yuan, S.C. Flow behavior and dynamic recrystallization of BT25y titanium alloy during hot deformation. High Temp. Mater. Proc. 2018, 37, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semiatin, S.L.; Furrer, D.U. Modeling of microstructure evolution during the thermo-mechanical processing of titanium alloys. In Fundamentals of Modeling for Metals Processing; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2009; Volume 22A, p. 522. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, I.; Froes, F.H.; Eylon, D.; Welsch, G.E. Modification of alpha morphology in Ti-6Al-4V by thermomechanical processing. Metall. Trans. A 1986, 17, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, C.; Wang, S.; Sun, H.; Feng, Y. Constitutive relationship and deformation mechanism of SLM Ti-6Al-4V alloy under high strain rate. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1038, 182659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Luo, J. Deformation anisotropy and lamellar α re-orientation of TC17 alloy under the different slip modes of HCP structure. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Shi, X.; Yan, X.; Guo, H. Dynamic softening behavior of Ti-6.5Al-2Sn-4Zr-4Mo-1W-0.2Si alloy with lamellar starting microstructure during hot deformation. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 16, 3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Fan, X.; Zhan, M.; Wang, L.; Tan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Y. Lamellar kinking in primary hot working of titanium alloy: Cross-scale behavior and mechanism. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 307, 117659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Hou, M.; Yu, K.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, H. Flow behavior and dynamic recrystallization mechanism of a new near-alpha titanium alloy Ti-0.3Mo-0.8Ni-2Al-1.5Zr. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Deng, Y.; An, Y.; Yuan, L.; Zhan, X.; Wang, B. Strain rate affects the deformation mechanism of a Ti-55511 titanium alloy: Modeling of constitutive model and 3D processing map using machine learning. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Fang, H.; Yu, J.; Sun, S.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, R. A study on the collaborative deformation mechanisms of continuous and discontinuous dynamic recrystallization under low strain rates for the Ti6455x alloy with a low activation energy. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2024, 330, 118478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Yang, R.; Yang, J.; Xu, X.; He, Y.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Fu, A.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, H. The investigation of α/β interface structure in Ti-5Al-6Nb(V/Cr) model titanium alloys. Mater. Charact. 2025, 225, 115161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Suwas, S. Enhanced superplasticity for (α + β)-hot rolled Ti-6Al-4V-0.1B alloy by means of dynamic globularization. Mater. Des. 2014, 58, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, M.Q. Further mechanism of α/β interphase boundary evolution and dynamic globularization of Ti-5Al-2Sn-2Zr-4Mo-4Cr at elevated temperature deformation. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2022, 32, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T.; Belyakov, A.; Kaibyshev, R.; Miura, H.; Jonas, J.J. Dynamic and post-dynamic recrystallization under hot, cold and severe plastic deformation. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 60, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Xin, R.; Huang, C.; Xin, S. Transformation twins enable high strength-ductility synergy in a lamellar Ti-55531 alloy: Variant selection and deformation mechanisms. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1036, 181943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Song, X.; Hui, S.; Ye, W. In-situ SEM observations of fracture behavior of BT25y alloy during tensile process at different temperature. Mater. Des. 2017, 116, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Zhu, J.; Zaefferer, S.; Raabe, D. Effect of retained beta layer on slip transmission in Ti-6Al-2Zr-1Mo-1V near alpha titanium alloy during tensile deformation at room temperature. Mater. Des. 2014, 56, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Ye, P.; Han, W.C.; Li, M.Q. Collaborative behavior in α lamellae and β phase evolution and its effect on the globularization of TC17 alloy. Mater. Des. 2018, 146, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.U.; Kesavan, D.; Kamaraj, M. Possible globularization mechanism in LPBF additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V alloys. Mater. Charact. 2023, 205, 113303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.