Abstract

This study investigates the as-cast Mg-8Gd-1Y-2Sm-1.2Zn-0.5Mn (wt.%) alloy with high rare-earth content. Solution treatments were conducted at 480 °C, 520 °C, and 560 °C for 6–10 h. Microstructure and mechanical properties were characterized using OM, XRD, SEM-EDS, and compression testing. The as-cast alloy shows a dendritic structure with continuous grain-boundary phases (Mg5RE, W, and LPSO), exhibiting a compressive yield strength of 145 MPa, ultimate strength of 238 MPa, and fracture strain of 12.66%. Solution temperature has a critical influence on phase dissolution and grain refinement. Notably, the overall plasticity of the material did not show a significant dependence on the specific solution temperature or holding time within the studied range. Treatment at 520 °C produces the most balanced microstructure: clear grain boundaries, extensive phase dissolution, refined grains, and enhanced solid-solution strengthening. Specifically, 520 °C for 10 h results in the finest and most uniformly distributed residual phases, a homogeneous matrix, the highest compressive strength, and suitable conditions for subsequent aging, thus being identified as optimal. Fractography reveals a transition from quasi-cleavage in the as-cast state toward enhanced ductility after solution treatment. However, small cleavage facets after 10 h are attributed to stress concentrations from rare-earth-rich regions and reduced deformation compatibility due to retained LPSO phases.

1. Introduction

Magnesium alloys are lightweight metallic materials with considerable application potential in the aerospace industry, owing to their high specific strength, low density, and excellent damping capacity [1]. With a density of only 1.74–2.0 g/cm3, magnesium is approximately 33% and 77% lighter than aluminum and steel, respectively [2]. However, their wider application has been significantly constrained by inherent limitations, including a suboptimal strength–ductility balance, relatively poor corrosion resistance, and limited room-temperature formability.

The addition of rare-earth (RE) elements provides an effective strategy to address these limitations. Elements such as gadolinium (Gd), yttrium (Y), and neodymium (Nd) can synergistically enhance the strength, ductility, and corrosion resistance of magnesium alloys through mechanisms including microstructural refinement, texture modification, and the formation of strengthening precipitates [3]. The combined addition of multiple RE elements can further promote such synergistic strengthening effects, offering a promising direction for developing next-generation high-performance Mg alloys. In the context of high-temperature aerospace materials, adding 2.5–4.0 wt.% of RE elements like Gd or Y can significantly elevate the long-term service temperature of Mg alloys from 120 °C to 300 °C. For example, a typical as-cast Mg-10Gd-3Y-0.5Zr alloy retains a yield strength of 220 MPa at 250 °C [4]. For biomedical applications, studies have shown that RE additions can markedly improve both mechanical properties and corrosion resistance [5]. In binary Mg–Sm systems, the maximum solid solubility of samarium in magnesium is 5.8 wt.%, indicating considerable potential for solid-solution and age-hardening effects. The aging precipitation sequences and precipitate phases in such alloys have been extensively studied. For instance, Xie et al. [6] revealed that the formation of the β1 phase in this system is governed by a diffusion-displacement coupling mechanism. Meanwhile, Zhou et al. [7] investigated the effect of trace Mn additions on the ductility of wrought Mg alloys, demonstrating that minor Mn can refine the grain size from 28.30 μm to 5.10 μm and simultaneously enhance both strength and ductility by reducing the critical resolved shear stress difference between basal and non-basal slip systems.

Heat treatment is a key process for regulating the microstructure and properties of magnesium alloys, and its optimal design is crucial for enhancing their strength and toughness. For example, Zhang et al. [8] reported that solution treatment significantly improves the mechanical properties of Mg-Gd-Y-Zn-Zr series alloys, achieving a tensile strength of 343 MPa and an elongation of 18.9% after treatment at 520 °C for 12 h. Liu et al. [9] studied the homogenization of Mg-Zn-Sn series alloys, finding that single-stage homogenization leads to the decomposition of the Mg2Zn3 phase and precipitation of the Mg2Sn phase, with overheating occurring at 350 °C. They identified an optimal two-stage process: 335 °C for 24 h followed by 400 °C for 6 h. Researchers from the Russian Academy of Sciences [10] balanced strength and ductility in a Mg-Y-Gd-Zr alloy containing Sm by employing an optimized heat treatment (515 °C/6 h solution treatment + 200 °C/32 h aging), yielding significantly better comprehensive properties than the conventional IMV7-1 alloy. Through a combination of thermodynamic calculations and experimental verification, Li et al. [11] optimized the heat treatment for Mg-Gd-Y-Zn-Zr alloys, determining 500 °C for 18 h as the optimal solution treatment. In a study on the same alloy system, Han, D. et al. [12] observed that solution treatment at 500 °C for 5 h promoted the growth of newly formed lamellar LPSO phases from grain boundaries into the grain interiors. This microstructural evolution contributed to optimal mechanical properties after peak aging at 200 °C for 4 h, confirming the significant influence of LPSO phase regulation on alloy performance.

Based on the aforementioned research, current studies on multi-component Mg-RE alloys have primarily focused on systems containing a limited variety of rare earth elements (e.g., Gd, Y, and Nd) or simpler compositions, with research topics largely addressing aging strengthening, precipitation phase regulation, and microstructure–property correlations. However, there remains a scarcity of reports concerning the mechanical property evolution and heat treatment optimization of multi-component Mg alloys containing elements such as Sm, Zn, and Mn, particularly those with a high total rare earth content and specifically designed elemental ratios. Furthermore, systematic investigations on the as-cast room-temperature compressive properties and fracture characteristics of such alloys are lacking in the existing literature, while studies on the relationship between heat treatment processes and microstructure–property correlations in these systems are also relatively insufficient. In light of this, the present study selects a multi-component high-rare-earth magnesium alloy with a Zn/(Gd + Y) ratio of approximately 0.133, namely Mg-8Gd-1Y-2Sm-1.2Zn-0.5Mn, and systematically investigates the effects of solution treatment on its microstructure and properties. The aim is to establish a microstructural control basis for subsequent optimization of heat treatment protocols and plastic processing while also providing experimental data and references for the design of heat treatment processes in similar multi-component high-rare-earth magnesium alloys.

2. Materials and Methods

An ingot of the Mg-8Gd-1Y-2Sm-1.2Zn-0.5Mn (wt.%) alloy was prepared by vacuum induction melting, with the chemical composition detailed in Table 1. The alloy was prepared using high-purity Mg (≥99.98%) and Zn (≥99.98%) ingots, along with Mg-Gd, Mg-Y, Mg-Sm, and Mg-Mn master alloys (Changchun, China). Melting was carried out under a protective atmosphere of CO2 mixed with 0.5 vol% SF6. The charge was first heated to approximately 730 °C for complete melting, held at 750 °C for 20 min, and then poured into a cylindrical mold preheated to 350 °C. Finally, the casting was air-cooled to room temperature. Cylindrical specimens (Φ 8 mm × 10 mm) were machined from the central, more uniform region of the as-cast ingot (Φ 100 mm × 130 mm). Solution treatments were conducted in a KF1200 chamber resistance furnace. Based on relevant alloy phase diagrams and prior heat treatment studies [13,14,15,16,17], three solution temperatures—480 °C, 520 °C, and 560 °C—were selected, with holding times of 6 h, 8 h, and 10 h at each temperature. To prevent quenching cracks, all treated specimens were immediately quenched in hot water at 80 °C. The samples were labeled according to their processing conditions: SC48006, SC48008, SC48010, SC52006, SC52008, SC52010, SC56006, SC56008, and SC56010.

Table 1.

The actual composition of Mg-8Gd-1Y-2Sm-1.2Zn-0.5Mn (wt.%).

Metallographic specimens of both as-cast and solution-treated alloys were prepared by sequential polishing using waterproof abrasive paper followed by etching. The etching was performed with a supersaturated picric acid solution (composition: 5 g of picric acid, 5 g of acetic acid, 10 mL of distilled water, and 100 mL of ethanol) for 40–60 s. Before use, the etching solution was preheated to 80 °C in a water bath maintained at a constant temperature. Microstructural observation was conducted using a Leica DM2700M optical microscope (Wetzlar, Germany). For each specimen, the average grain size was determined by taking five optical micrographs at 50× magnification from different regions, measuring all grains within each micrograph using Nano Measurer 1.2 software, and calculating the arithmetic mean of the five datasets. Phase identification for all samples was performed using X-ray diffraction (XRD). To ensure reliable mechanical property measurements, cylindrical specimens (Φ 8 mm × 10 mm) were first polished to a smooth finish after heat treatment to minimize the influence of surface defects. Room-temperature uniaxial compression tests were then conducted using a CMDW-100 universal testing machine (Shanghai, China) at a constant crosshead speed of 1 mm/min. Three tests were performed for each condition to ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of the obtained data. Microstructural analysis, compositional examination, and fractography of the compressed specimens were performed using an Apreo 2S HiVac high-resolution field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Shanghai, China) equipped with an energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of As-Cast Alloy

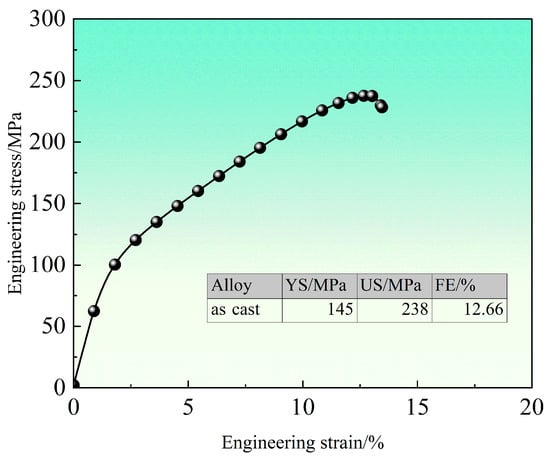

Figure 1 shows the room-temperature engineering stress–strain curves and corresponding mechanical properties of the as-cast alloy. The curve exhibits a brief initial linear elastic region without a distinct yield plateau. The as-cast alloy demonstrates a yield strength of approximately 145 MPa, an ultimate compressive strength of about 238 MPa, and a fracture strain of 12.66%. This fracture strain indicates limited deformability, attributed to the divorced eutectic phases and microsegregation in the as-cast structure. Furthermore, the presence of second-phase particles along grain boundaries and residual internal stresses from solidification contribute to the relatively high yield and compressive strengths of the alloy in the as-cast condition.

Figure 1.

Compression engineering stress–strain curve of as-cast alloy at room temperature.

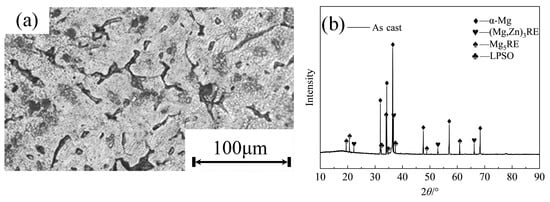

Figure 2a shows the as-cast microstructure of the alloy, which exhibits typical dendritic solidification characteristics. A distinct network of continuous or semi-continuous secondary phases is distributed along the interdendritic regions and grain boundaries. Locally, granular or island-shaped precipitates are also observed, indicating significant segregation of rare-earth and Zn elements during solidification, where they enriched the interdendritic areas to form eutectic or secondary phases. This microstructure reveals pronounced compositional segregation and inhomogeneous phase distribution in the as-cast state. The continuous secondary phases are potential brittle weak points, while the dendritic matrix shows a relatively uniform solid-solution structure. As shown in the XRD pattern of the as-cast alloy (Figure 2b), four primary phases are identified: the α-Mg matrix, the Mg5RE phase, the W phase, and the LPSO phase. Notably, the Mg5RE phase shows strong diffraction peaks, suggesting a substantial volume fraction. The presence of these secondary phases influences the alloy’s mechanical properties, where the distribution and morphology of the Mg5RE phase likely contribute to increased hardness and embrittlement.

Figure 2.

Microstructure and XRD of as-cast alloy: (a) metallography; (b) XRD pattern.

3.2. Mechanical Properties in the Heat-Treated State

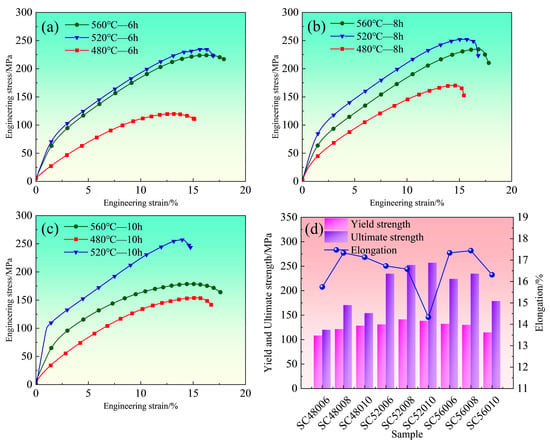

Figure 3a–c show the room-temperature compressive engineering stress–strain curves for holding durations of 6 h, 8 h, and 10 h at different temperatures, with the corresponding mechanical property data summarized in Figure 3d. Analysis of the curves indicates that the material exhibits the lowest strength at 480 °C (determined by the universal testing machine software according to the proof stress at specified plastic elongation). Both yield and compressive strengths peak at 520 °C, followed by a decrease at 560 °C. As shown in Figure 3d, the strength generally increases and then decreases after heat treatment. With few exceptions, the post-fracture elongation is not significantly influenced by the solution temperature or its duration. Specifically, the highest strength is achieved after solution treatment at 520 °C for 10 h, although this condition also results in the lowest elongation. In comparison, both the 480 °C—6 h and 560 °C—10 h conditions yield relatively inferior mechanical properties.

Figure 3.

Solid-solution-state room-temperature compression engineering stress–strain curve: (a) curve under different solid-solution temperatures for 6 h; (b) curves at different solid-solution temperatures for 8 h; (c) curves at different solid-solution temperatures for 10 h; (d) mechanical properties diagram of solid-solution state.

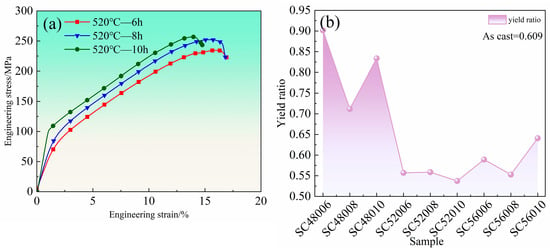

Figure 4a shows the room-temperature engineering compressive stress–strain curves for the alloy solution treated at 520 °C under various holding times, while Figure 4b presents the corresponding yield ratio for each condition. With extended holding time at 520 °C, the strength of the material increases progressively. Specifically, after holding for 10 h, the compressive strength reaches approximately 257 MPa. As shown in Figure 4b, the yield ratio is highest at 480 °C (attributed to incomplete microstructural homogenization, e.g., residual stress and coarse undissolved eutectics) and lowest at 520 °C. The yield ratio, to some extent, reflects the plasticity of structural materials: a lower ratio indicates a greater capacity for plastic deformation. The as-cast alloy has a yield ratio of 0.609, whereas all samples treated at 520 °C exhibit ratios below 0.6, with the 10 h treatment achieving the minimum value of 0.537. Although the improvement in elongation at 520 °C for 10 h is relatively modest compared to the as-cast state, the reduced yield ratio suggests enhanced uniform plastic deformation, allowing for greater deformation before failure.

Figure 4.

Compressive mechanical properties of solid solution at room temperature: (a) compression engineering stress–strain curves at room temperature with different holding time at 520 °C; (b) yield ratio diagram.

3.3. Microstructure in the Heat-Treated Condition

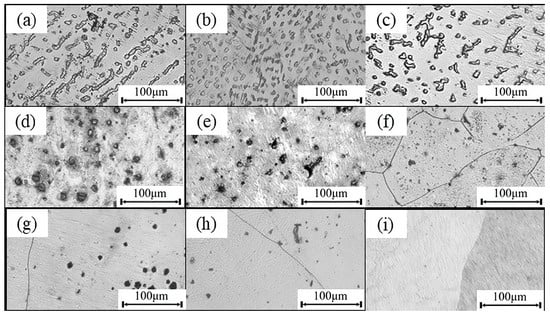

Figure 5 shows the microstructural evolution of the alloy after solution treatment at different temperatures (480 °C, 520 °C, and 560 °C) and holding times (6 h, 8 h, and 10 h). Under the 480 °C condition (Figure 5a–c), the RE-rich secondary phases, which were originally continuous or semi-continuous along interdendritic regions and grain boundaries, begin to dissolve. As the holding time increases from 6 h to 10 h, these phases fragment and show a tendency to spheroidize. However, their amount and volume fraction remain relatively high, indicating incomplete dissolution into the matrix at this temperature. When the temperature is increased to 520 °C (Figure 5d–f), the secondary phases dissolve more extensively. The coarse phases initially present at grain boundaries are significantly refined and dispersed into finer particles. With prolonged holding time, the composition within the matrix becomes more uniform, grain boundaries no longer show continuous secondary phases, and they become increasingly distinct. At the elevated temperature of 560 °C (Figure 5g–i), although the remaining secondary phases continue to decrease and the number and size of precipitates are further reduced, noticeable grain growth occurs. As the holding time is extended to 10 h, grain growth becomes more pronounced, accompanied by a localized tendency toward “overheating.” This suggests that extended treatment at this temperature promotes grain coarsening and microstructural degradation, which may adversely affect the mechanical properties of the material.

Figure 5.

Microstructure of the solid-solution alloy: (a–c) SC48006, SC48008, and SC48010; (d–f) SC52006, SC52008, and SC52010; (g–i) SC56006, SC56008, and SC56010.

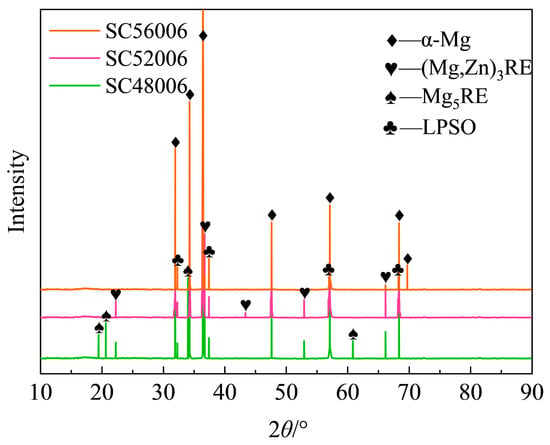

Analysis of the XRD patterns for the solution-treated samples (Figure 6) shows that after holding for 6 h at different temperatures, the diffraction peak intensity of the Mg5RE phase decreases significantly as the solution temperature increases from 480 °C to 560 °C, indicating progressive dissolution of this phase. Concurrently, the characteristic peak intensity of the W phase also gradually diminishes. Diffraction peaks corresponding to the LPSO phase remain detectable under all conditions, with a slight increase in intensity observed at and above 520 °C, suggesting a marginal rise in its content and confirming its favorable thermal stability. Based on the grain size measurements in Table 2 for the 6 h treatments, the grain size first decreases and then increases as the solution temperature rises. Although the overall grain size remains relatively large, the sample treated at 520 °C exhibits the finest structure among the conditions tested. The solution-treated material’s large grain size results in insufficient ductility, which is a disadvantage compared to materials in similar application fields [18,19].

Figure 6.

XRD patterns at different solid-solution temperatures for 6 h.

Table 2.

The average grain size at different solution temperatures.

Based on the comprehensive analysis of microstructure and mechanical properties presented above, the sample treated at 480 °C showed significant compositional segregation, unclear grain boundaries, and a high amount of undissolved secondary phases. Although these phases provided limited strengthening, the coarse grain size (490.95 μm) led to suboptimal alloy strength. When the temperature was raised to 560 °C, excessive grain growth occurred (557.88 μm), resulting in increasingly blurred grain boundaries and the onset of localized melting, which reduced the alloy strength and compromised the effectiveness of the solution treatment. In contrast, the sample treated at 520 °C exhibited clear grain boundaries, extensive dissolution of secondary phases—now finer and more uniformly distributed—and increased solid solubility of rare-earth elements in the matrix. These microstructural features promoted grain refinement (406.16 μm) and pronounced solid-solution strengthening. XRD results confirmed the coexistence of W and LPSO phases, which synergistically strengthened the matrix, increasing the compressive strength by approximately 8.075% compared with the as-cast condition. Therefore, 520 °C is identified as the optimal solution temperature, effectively addressing the incomplete dissolution observed at 480 °C while avoiding the grain coarsening associated with 560 °C.

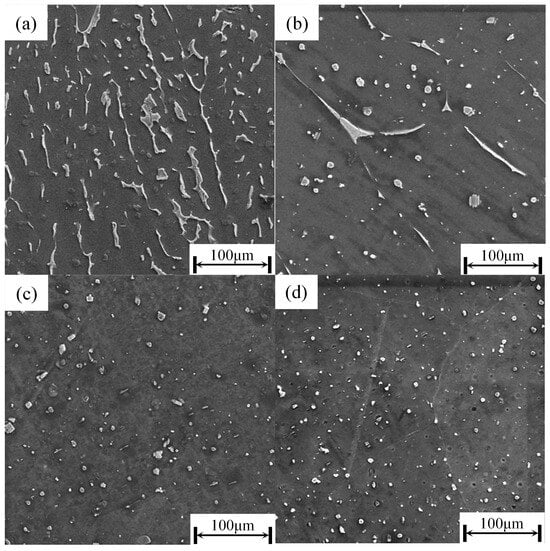

3.4. Morphology and Composition of the Secondary Phase

As shown in Figure 7, the second phase in the as-cast microstructure (Figure 7a) is primarily distributed as a continuous, coarse network with an elongated or irregular morphology. During holding at 520 °C, its morphology evolves progressively: after 6 h, the elongated structure breaks up into dispersed blocky or short rod-shaped particles of varying sizes; by 8 h, the second phase further refines and distributes more uniformly, with an increased proportion of granular forms; and after 10 h, granular particles dominate, resulting in a more discrete overall distribution. In summary, with prolonged holding time, the second phase gradually transitions from a continuous coarse network to a fine, dispersed granular morphology.

Figure 7.

The SEM images of the as-cast and solid-solution morphology at 520 °C: (a) as cast; (b) SC52006; (c) SC52008; (d) SC52010.

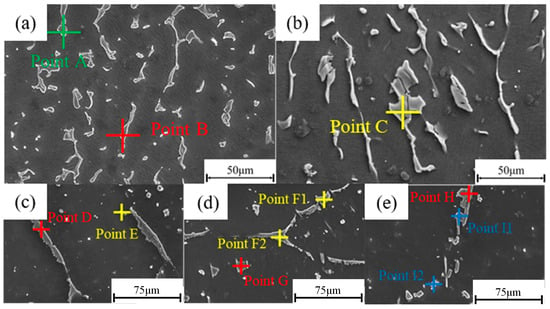

Figure 8 shows the EDS spectra for the as-cast and solution-treated conditions. Figure 8a,b correspond to the as-cast microstructure, while Figure 8c–e indicate the locations of point scans performed after 6 h, 8 h, and 10 h at 520 °C, respectively. The corresponding chemical compositions are summarized in Table 3. In the as-cast state (Figure 8a,b), three main types of secondary phases are observed. The blocky phase marked at point A (green) has a composition approximating Mg5RE. The blocky phase at point B (red) shows a Zn/(Sm + Gd) atomic ratio near 1, consistent with the LPSO phase. The network-like phase at point C (yellow) has a composition close to (Zn, Mg)3RE, aligning with the findings of Ding et al. [17]. After solution treatment at 520 °C for 6 h (Figure 8c), the phase composition changes notably. The content of the Mg5RE phase decreases significantly, while the LPSO phase (e.g., at point D) coarsens and distributes along grain boundaries. The small blocky phase at point E is identified as (Zn, Mg)3RE based on EDS results, consistent with Yin et al.’s results [20], indicating its tendency to dissolve during treatment. When the holding time is extended to 8 h (Figure 8d), the Mg5RE phase dissolves completely. The fine blocky phase within the grain at point G has a Zn/(Sm + Gd) ratio ~0.8, close to unity, and is preliminarily identified as LPSO. Points F1 and F2 exhibit a Zn/(Sm + Gd) atomic ratio of about 3:2, indicating the presence of W-phase particles along grain boundaries, which contribute to strengthening. According to Yin et al., (Zn, Mg)3RE and W phases share structural similarities and similar XRD patterns [20]. After 10 h at 520 °C (Figure 8e), the W phase is nearly absent. The irregular blocky phase at the grain boundary (point H) is identified as LPSO based on composition. Cubic precipitates at grain boundaries (points I-1 and I-2) show high concentrations of rare-earth elements, with Mg below detection limits, suggesting the formation of RE-rich phases. Similar phases have been characterized via TEM by Chen et al., with comparable compositional results [21].

Figure 8.

As-cast and 520 °C solid-solution EDS patterns: (a,b) as cast; (c–e) SC52006, SC52008, and SC52010.

Table 3.

The corresponding EDS results of each point in Figure 8 (at.%).

To further examine the effect of holding time at 520 °C on solid-solution behavior, energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis of the matrix was performed on the as-cast and solution-treated specimens (held for 6 h, 8 h, and 10 h). The results are shown in Table 4. In the as-cast condition, the main solute elements in the matrix were Gd (1.32 at.%) and Sm (0.38 at.%), with no significant dissolution of other alloying elements. After 6 h (SC52006), Zn began to dissolve into the matrix (0.46 at.%), while the solute contents of Gd and Sm were lower than those in the as-cast state, indicating that the solid-solution process was still incomplete. When the holding time was extended to 8 h (SC52008), the solid solubility of Zn increased markedly to 0.70 at.%, Mn began to dissolve, and the solute levels of Gd and Sm recovered to near the as-cast values, reflecting enhanced dissolution of alloying elements. At 10 h (SC52010), the Zn content rose further to 0.85 at.%, Mn stabilized at 0.33 at.%, and the concentrations of Gd and Sm reached levels comparable to and as stable as those in the as-cast specimen. These results indicate that prolonging the holding time promotes the dissolution of alloying elements into the Mg matrix. After 10 h, the solid solubility approaches a near-saturated and stable state, demonstrating a more complete solid-solution process.

Table 4.

Matrix energy spectrum composition of as-cast and 520 °C solid-solution states (at.%).

To clarify the effect of second-phase evolution on the mechanical properties of the rare-earth magnesium alloy under different holding times at 520 °C, this study systematically examines the matrix solid-solution behavior and related strengthening mechanisms. In the as-cast condition, the coarse secondary phases, which exhibited a continuous elongated or irregular network, fragmented into dispersed blocky or short-rod particles after 6 h at 520 °C. Although the Mg5RE phase content decreased notably, the solid solubility of Zn remained low (0.46 at.%), and the dissolved amounts of Gd and Sm were still below the as-cast levels. Consequently, solid-solution strengthening from matrix lattice distortion was weak. Undissolved large grain-boundary phases pinned dislocations, but insufficient refinement and non-uniform distribution of these phases limited strength improvement. Conversely, the fragmentation and dispersion of the originally continuous brittle phases alleviated stress concentration, resulting in a relative increase in ductility. After extending the holding time to 8 h, the second phase became more dispersed but remained relatively coarse. At this stage, the Mg5RE phase dissolved completely, the Zn solid solubility rose to 0.70 at.%, and the solid-solution levels of Gd and Sm stabilized. A noticeable solid-solution strengthening effect began to develop. Improved phase dispersion reduced stress concentration during deformation, while moderate obstruction of dislocation slip allowed a balance of enhanced strength and retained ductility. After 10 h, the matrix approached relative saturation in Zn, Gd, and Sm, leading to the strongest solid-solution strengthening. The second phase reached its finest size and was uniformly distributed. The LPSO phase and rare-earth-rich phases were further stabilized and contributed to precipitation strengthening. Specifically, the LPSO phase with reduced dimensions at 520 °C can accommodate dislocations through self-deformation, thereby strengthening the matrix, while the rare-earth-rich phase particles precipitated after a 10 h hold at 520 °C effectively pin dislocations via an Orowan mechanism, and this synergy between solid-solution and precipitation strengthening accounts for the highest alloy strength. The decrease in ductility, however, is attributed to two main factors: (1) hard and brittle rare-earth-rich phases near grain boundaries acted as stress concentrators and micro-crack initiation sites; and (2) the increased volume fraction of the LPSO phase required coordinated deformation with the Mg matrix during plastic straining. Although the LPSO phase can accommodate slip deformation aligned with the matrix, its kinking deformation is difficult to synchronize, significantly raising the overall deformation resistance and markedly reducing elongation [22]. Despite the loss in ductility after the 10 h treatment, the second phase transformed from the original coarse, continuous network into fine, uniformly distributed particles. Together with sufficient matrix solid solution and the strong synergy between solid-solution and precipitation strengthening, this condition satisfies the prerequisites for subsequent pre-aging treatments. Considering the overall strength advantage and process compatibility, 520 °C for 10 h is identified as the optimal solution-treatment condition for this rare-earth magnesium alloy.

3.5. Fracture Appearance

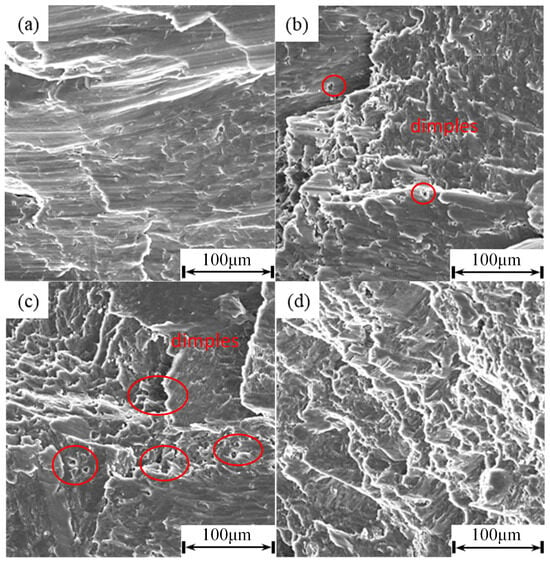

Figure 9 shows the compressive fracture morphologies of the as-cast specimen and the specimens solution treated at 520 °C for different durations. The as-cast sample exhibits prominent cleavage steps and lamellar tearing features, indicative of a quasi-cleavage fracture mode. This is primarily due to the continuously distributed brittle secondary phases (e.g., eutectic phases) in the interdendritic regions of the as-cast structure. These phases form weak interfaces along grain boundaries and interdendritic zones, promoting rapid crack propagation and resulting in the material’s relatively low plasticity and toughness. After solution treatment at 520 °C, the fracture morphology gradually evolves with prolonged holding time. Following treatment for 6 h, several shallow dimples begin to appear on the fracture surface, and the cleavage facets become more fragmented. This suggests that the solution treatment promotes the dissolution of some brittle phases, leading to more tortuous crack paths and improved toughness compared with the as-cast condition. When the treatment time is extended to 8 h at 520 °C, dimple features become more noticeable and are accompanied by evident tear ridges, indicating that the connectivity of the brittle secondary phases is further disrupted. This impedes crack propagation and contributes to a transition from quasi-cleavage to a mixed ductile fracture mode, accompanied by the most significant improvement in plasticity. However, after extending the solution time to 10 h, the fracture surface displays numerous small cleavage facets along with river patterns. These features are likely associated with the excessive formation of LPSO phases, which reduces deformation compatibility, as well as stress concentration induced by rare-earth-rich phases, collectively leading to a decrease in plasticity. These observations align with the previously discussed mechanical properties and microstructural characterization, confirming the reduction in material plasticity under these conditions.

Figure 9.

Compression fracture morphology: (a) as cast; (b) SC52006; (c) SC52008; (d) SC52010.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The as-cast rare-earth magnesium alloy shows a dendritic structure with continuous or semi-continuous networks of secondary phases distributed along intergranular and grain boundary regions. Locally, isolated blocky or island-shaped precipitates are observed, indicating considerable compositional segregation and inhomogeneous phase distribution. XRD analysis identifies the α-Mg matrix, Mg5RE phase, W phase, and LPSO phase. The alloy exhibits a room-temperature yield strength of about 145 MPa, an ultimate compressive strength of 238 MPa, and a fracture strain of 12.66%.

- (2)

- The solution temperature plays a critical role in regulating the microstructure and properties of the alloy. At 480 °C, severe compositional segregation, coarse grains, and a high fraction of undissolved secondary phases lead to the lowest strength. At 560 °C, excessive grain growth and incipient melting cause a decrease in strength. In contrast, at 520 °C, grain boundaries become well defined, secondary phases dissolve more completely, and the solid solution of rare-earth elements strengthens the matrix, accompanied by grain refinement to 406.16 μm, resulting in the highest strength. Therefore, 520 °C is established as the optimum solution temperature. It is noted that the overall plasticity of the material remains largely unaffected by the solution temperature and holding time, and its improvement is limited due to the relatively large average grain size.

- (3)

- Through SEM/EDS characterization, the mechanism by which second-phase evolution influences mechanical properties during solution treatment at 520 °C under different holding times was elucidated. After 6 h, the Mg5RE phase decreased, while elements such as Zn remained insufficiently dissolved. By 8 h, complete dissolution of the Mg5RE phase occurred, and W and LPSO phases provided synergistic pinning. After 10 h, the second phase reached its smallest size, accompanied by strong synergistic strengthening from solid-solution and precipitation effects as well as a homogeneous solute distribution in the matrix, satisfying the prerequisite for subsequent aging treatment. In summary, the optimal solid-solution condition is 520 °C for 10 h.

- (4)

- The as-cast specimen shows a quasi-cleavage fracture surface with limited ductility. After solution treatment at 520 °C, toughness improves from 6 h to 8 h, and the fracture mechanism shifts from quasi-cleavage to a mixed mode, accompanied by a clear increase in plasticity. At 10 h, the fracture surface exhibits many small cleavage facets with river patterns, attributable to excessive LPSO phases that reduce deformation compatibility and to stress concentrations caused by rare-earth-rich phases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C. and Z.C.; Formal analysis, F.W., C.X., and Z.Q.; Funding acquisition, Z.C.; Investigation, Z.Q. and F.W.; Methodology, F.W., C.X., and C.C.; Project administration, Z.C.; Resources, C.C.; Supervision, Z.C.; Visualization, F.W., C.X., and Z.C.; Writing—original draft, Z.Q.; Writing—review and editing, C.X., C.C., and Z.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52175353), the Shanxi Province Basic Research Program Joint Funding Project (202403011211004), the Shanxi Province Science and Technology Achievement Transformation Guidance Program Project (202404021301039), the Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Plan Item (20250201062GX), and the Key R&D Program Projects of Shanxi Province (202102150401002).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, G.; Yang, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Xie, W.; Wei, G.; Yang, Y.; Peng, X.; Tan, J. Innovative developments and strategic utilization of advanced magnesium alloys in aerospace engineering. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1039, 183073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasathyakawin, S.; Ravichandran, M.; Baskar, N.; Anand Chairman, C.; Balasundaram, R. Mechanical properties and applications of Magnesium alloy–Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Ayoub, I.; He, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Hao, Q.; Cai, Z.; Ola, O.; Tiwari, S.K. Magnesium alloys with rare-earth elements: Research trends applications, and future prospect. J. Magnes. Alloys 2025, 13, 3524–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Wang, C.; Dong, B.-X.; Yang, H.-Y.; Zhan, L.; Luo, D.; Qiu, F.; Jiang, Q.-C. Rare Earth Elements in Heat-Resistant Magnesium Alloys: Mechanisms, Performance, and Design Strategies. Materials 2025, 18, 4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Choudhari, A.; Gupta, A.K.; Kumar, A. Rare-Earth based magnesium alloys as a potential biomaterial for the future. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 3841–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Yang, Y.; Wen, C.; Chen, J.; Zhou, G.; Jiang, B.; Peng, X.; Pan, F. Applications of magnesium alloys for aerospace: A review. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 3609–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, T.; Tang, A.; Shi, H.; Jing, X.; Peng, P.; Zhang, J.; Pan, F. Ductility enhancement by activating non-basal slip in Mg alloys with micro-Mn. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2024, 34, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, Y.; Li, J.; Yue, H.; Li, C.; Ma, J.; Qin, J.; Guo, S.; Li, C.; Chen, Q. Effect of stacking faults and long period stacking order on mechanical properties for rare-earth magnesium alloy: As-cast versus as-solutioned. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 1601–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-H.; Ma, M.-L.; Li, X.-G.; Li, Y.-J.; Shi, G.-L.; Yuan, J.-W.; Zhang, K. Homogenization treatment of Mg-6Zn-3Sn (wt.%) alloy and its effects on microstructure and mechanical properties. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2023, 33, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhlin, L.L.; Dobatkina, T.V.; Tarytina, I.E.; Luk’yanova, E.A.; Ovchinnikova, O.A. Effect of Samarium on the Strength Properties of Mg–Y–Gd–Zr Alloys. Russ. Metall. (Met.) 2021, 2021, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, G.; Yin, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Guan, R. Designing the heat treatment process for Mg-10Gd-4Y-xZn-0.6Zr (wt.%) alloy: A study on the transformation of microstructure and properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 6711–6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Chen, H.; Zang, Q.; Qian, Y.; Cui, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Y. Effect of solution treatment on microstructure and properties of Mg-6Gd-3Y-1.5Zn-0.6Zr alloy. Mater. Charact. 2020, 163, 110295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, L.; Sun, M.; He, M.; Zhao, Y. Recent progress in high-strength Mg-Gd-based alloys: The role of heat treatments in controlling microstructures and mechanical properties☆. J. Rare Earths 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Jin, P. The influence of the LPSO on the deformation mechanisms and tensile properties at elevated temperatures of the Mg-Gd-Zn-Mn alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 6216–6229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yi, M.; Yu, J.; Li, B.; Zhang, Z. The Formation of 14H-LPSO in Mg–9Gd–2Y–2Zn–0.5Zr Alloy during Heat Treatment. Materials 2021, 14, 5758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.L.; Wu, D.; Chen, R.S.; Han, E.-H. Effects of Gd/Y Ratio on the Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Cast Mg–Gd–Y–Zr Alloys. In Proceedings of the Magnesium Technology 2019; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.-B.; Zhao, Y.-H.; Lu, R.-P.; Yuan, M.-N.; Wang, Z.-J.; Li, H.-J.; Hou, H. Effect of Zn addition on microstructure and mechanical properties of cast Mg-Gd-Y-Zr alloys. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2019, 29, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Y.-Q. Study on the room temperature compression deformation mechanism and microstructural evolution of Mg-Gd-Y-Zr alloy. Vacuum 2024, 230, 113655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Chen, Z.; Yuge, K.; Kishida, K.; Inui, H.; Heilmaier, M. A new route to achieve high strength and high ductility compositions in Cr-Co-Ni-based medium-entropy alloys: A predictive model connecting theoretical calculations and experimental measurements. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 959, 170555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Le, Q.; Lan, Q.; Bao, L.; Cui, J. Effects of Zn/Gd ratio on the microstructures and mechanical properties of Mg-Zn-Gd-Zr alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 695, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Tao, X.; Wang, L.; Ma, K.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Wei, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Bai, P. Phase transformation during solid-solution and aging treatment of a Mg-Gd-Y-Zn-Zr alloy containing LPSO and W phases. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1005, 176176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H. Investigation on the Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of LPSO Containing Mg-Gd-Y-Zn Magnesium Alloys. Ph.D. Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.