Abstract

This work proposes a data-driven design framework for high-pressure die-cast (HPDC) aluminum alloys that integrates robust data refinement, machine learning (ML) modeling, explainability, and inverse design. A total of 1237 tensile-test records from T5-aged HPDC alloys were aggregated into a curated dataset of 382 unique composition–heat-treatment combinations. Four regression models—Ridge regression, Random Forest (RF), XGBoost (XGB), and a multilayer perceptron (MLP)—were trained to predict yield strength (YS), ultimate tensile strength (UTS), and elongation (EL). Tree-based ensemble models (XGB and RF) achieved the highest accuracy and stability, capturing nonlinear interactions inherent to industrial HPDC data. In particular, the XGB model exhibited the best predictive performance, achieving test R2 values of 0.819 for UTS and 0.936 for EL, with corresponding RMSE values of 15.23 MPa and 1.112%, respectively. Feature-importance and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analyses identified Mn, Si, Mg, Zn, and T5 aging temperature as the most influential variables, consistent with metallurgical considerations such as microstructural stabilization and precipitation strengthening. Finally, RF-based inverse design suggested new composition–process candidates satisfying UTS > 300 MPa and EL > 8%, a region scarcely represented in the experimental dataset. These results illustrate how interpretable ML can expand the feasible design space of HPDC aluminum alloys and support composition–process optimization in industrial applications.

1. Introduction

Lightweight design under increasingly stringent fuel-efficiency and emission regulations has intensified the demand for aluminum components in the automotive sector. The rapid growth of electric vehicles has further accelerated the adoption of large, integrated structural castings (e.g., mega-castings), reinforcing the importance of high-pressure die casting (HPDC) as a manufacturing route [1]. Therefore, HPDC Al–Si–Mg–Cu alloys are therefore widely used in body-in-white and chassis applications because of their excellent castability, high productivity, ability to form complex geometries, and capability to develop strength via T5 heat treatment without solution treatment [2]. Despite these advantages, the mechanical performance of HPDC aluminum alloys is governed by a complex and strongly coupled interplay between alloy chemistry, processing conditions, and microstructural heterogeneity. Key metallurgical factors include eutectic Si morphology and distribution, the formation and modification of Fe- and Mn-bearing intermetallic phases, precipitation behavior during T5 aging, and casting-related defects such as porosity and oxide-film entrapment. In particular, the absence of solution treatment in T5 processing makes tensile properties highly sensitive to the as-cast microstructure, while rapid solidification and turbulent filling inherent to HPDC introduce significant spatial variability and defect sensitivity. These nonlinear and interacting effects complicate the establishment of robust composition–process–property relationships under industrial conditions [3].

Previous studies have clarified the key microstructural contributors to tensile behavior, including eutectic Si morphology, Fe-based intermetallics, and porosity characteristics [4,5,6]. Ji et al. showed that the interaction between aging conditions and as-cast constituents critically affects both the strength and ductility of HPDC Al–Si–Mg alloys [7]. Lee et al. summarized the influence of the eutectic Si fraction, size, and distribution on tensile strength, elongation, and fracture toughness [8]. Porosity size and distribution are also the dominant sources of scatter in tensile properties of HPDC components [9]. However, much of the existing literature is based on narrow composition windows or relatively small laboratory datasets, which limits its ability to represent the variability, noise, and process-driven heterogeneity typical of industrial HPDC production. Therefore, quantitative prediction across broad industrial composition–process spaces (particularly alloy composition and post-casting T5 aging parameters) remains challenging.

Machine learning (ML) has recently gained traction for alloy design and property prediction because it can handle multivariate and nonlinear relationships more effectively than conventional empirical approaches [10,11]. Nevertheless, many ML studies rely on limited datasets, single-model pipelines, or insufficient treatment of measurement/process noise, which often results in weak generalizations to industrial data. In addition, limited interpretability is a major barrier to the practical use of ML in alloy design and process optimization [12]. Explainable AI methods such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) have been introduced to quantify the contributions of individual variables and improve metallurgical interpretability [13]; however, yet studies that jointly apply ML and SHAP to large-scale industrial HPDC datasets remain scarce.

Inverse design has also attracted attention as a way to directly identify composition–process combinations that satisfy the target property constraints. Wang et al. demonstrated the potential of an ML-based inverse design to complement conventional trial-and-error experiments [14]. Ren et al. reported accelerated alloy development by iteratively integrating ML with computational materials approaches [15]. However, for HPDC, substantial noise, process variability, and microstructural inhomogeneity make the inverse design particularly challenging, and integrated frameworks that combine robust data handling, interpretable ML, and inverse design have not been sufficiently explored.

Therefore, in this study, 1237 industrial tensile-test records for T5-aged HPDC aluminum alloys were refined using robust statistical aggregation to construct a curated dataset of 382 unique composition–heat-treatment combinations. Ridge regression, random forest, gradient-boosted decision trees, and multilayer perceptron models were then compared to predict yield strength (YS), ultimate tensile strength (UTS), and elongation (EL). SHAP was used to interpret the nonlinear contributions from alloying and aging variables, and RF was employed as a surrogate model for the inverse design to propose new candidates satisfying UTS > 300 MPa and EL > 8%. By integrating data refinement, predictive modeling, interpretability, and inverse design, this study provides a practical route toward strength–ductility balancing and composition–process optimization for industrial HPDC aluminum alloys.

2. Experimental Data and Machine Learning Methodology

A total of 1237 T5 aging–tensile test records were collected from the HPDC aluminum alloy specimens. The dataset was obtained from industrial HPDC production rather than controlled laboratory-scale experiments, and the casting conditions were not intentionally fixed but varied according to industrial practice across multiple production lines. Each record includes the alloy composition (Si, Mg, Cu, Zn, Fe, Mn, Cr, Ni, Ti, Zr, and Sr), T5 aging conditions (temperature and time), and tensile properties (YS, UTS, and EL). The compositions are given as weight percentages (wt.%). As summarized in Table 1, the dataset spans a broad composition range representative of industrial Al–Si–Mg–Cu–(Zn) die-casting alloys; for example, Si, Mg, Cu, and Zn vary over 0.00–11.49 wt.%, 0.00–6.50 wt.%, 0.00–4.70 wt.%, and 0.00–9.40 wt.%, respectively, while minor elements (Fe, Mn, Cr, Ni, Ti, Zr, and Sr) also show wide distributions. The T5 aging temperature ranges from 100 to 350 °C and the aging time from 30 to 2880 min, covering practical industrial conditions. Tensile testing was conducted following standardized testing procedures in accordance with relevant ASTM standards, while upstream casting parameters such as melt temperature, injection pressure, and piston speed were not strictly controlled.

Table 1.

List of input features (chemical composition and T5 heat-treatment parameters) and target mechanical properties (yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, and elongation) included in the dataset used for model training and evaluation.

For repeated tests with identical compositions and heat-treatment combinations, substantial scatter was observed, which is typical for HPDC alloys owing to their porosity, shrinkage, and local microstructural heterogeneity. To obtain representative values while mitigating the influence of outliers, a rule-based robust aggregation was applied. The arithmetic mean of two replicates was used. For the three replicates, a 2-of-3 mean was computed from the two values closest to the median. The median was used for four or more repeats. After aggregation, the dataset was consolidated into 382 unique composition–heat-treatment combinations for subsequent modeling. These repeated tests originate from industrial HPDC production rather than from strictly controlled laboratory experiments, and therefore inherently reflect process-induced variability such as porosity and defect populations associated with practical casting conditions. Accordingly, the aggregated values represent statistically robust responses under realistic industrial scatter rather than defect-free intrinsic properties.

Four supervised regression models were considered to capture nonlinear composition–process–property relationships: (1) Ridge regression, (2) Random Forest (RF), (3) gradient-boosted decision trees (XGB), and (4) a multilayer perceptron (MLP). Ridge regression was used as a linear baseline because of its L2-regularized coefficient stabilization under multicollinearity [16]. The RF was adopted as a bagging-based ensemble capable of capturing nonlinearities and high-order interactions via bootstrap sampling and random feature selection [17]. For RF, the number of trees and minimum leaf size were optimized using 5-fold cross-validation. XGB builds trees sequentially to reduce residual errors by following the negative gradient of the loss function. The general framework was introduced by Friedman [18], which provides an efficient implementation with regularization and optimized tree construction [19]. In this study, an XGB-style model was implemented using a MATLAB (ver. 2025b) LSBoost ensemble. The number of trees, learning rate, and minimum leaf size were tuned via 5-fold cross-validation with attention paid to overfitting. The MLP model was implemented as a fully connected feed-forward network with one hidden layer. The model parameters were optimized via backpropagation using gradient-based methods such as stochastic gradient descent or Adam [20,21]. Given the dataset size (382 samples), a shallow architecture was adopted to balance flexibility and generalization, and the number of hidden neurons (10, 20, and 30) was tuned using 5-fold cross-validation.

All models used the same input variables (13 alloying elements and two T5 parameters) and were trained separately for the YS, UTS, and EL (single-output regression). Missing values were imputed using the column-wise means. For Ridge regression and MLP, the inputs were standardized using Z-score normalization based on the training statistics. The dataset was split into training (80%) and test (20%) subsets, and the hyperparameters were selected by 5-fold cross-validation of the training set. The test performance was evaluated using MAE, RMSE, and R2. To assess the robustness to data partitioning, the 80/20 split was repeated with 100 random seeds, and the mean and standard deviation of the test R2 were reported for each model–target pair.

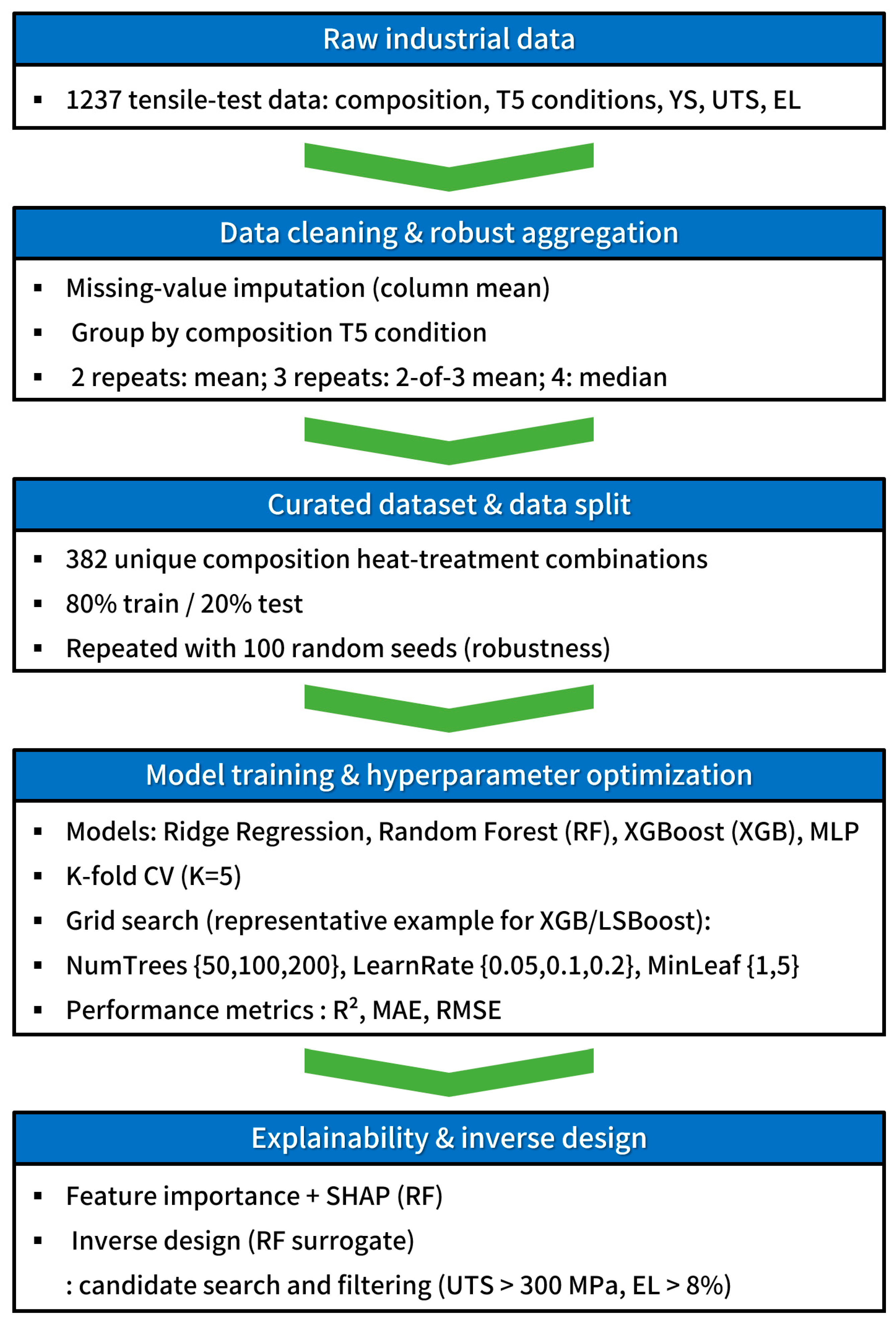

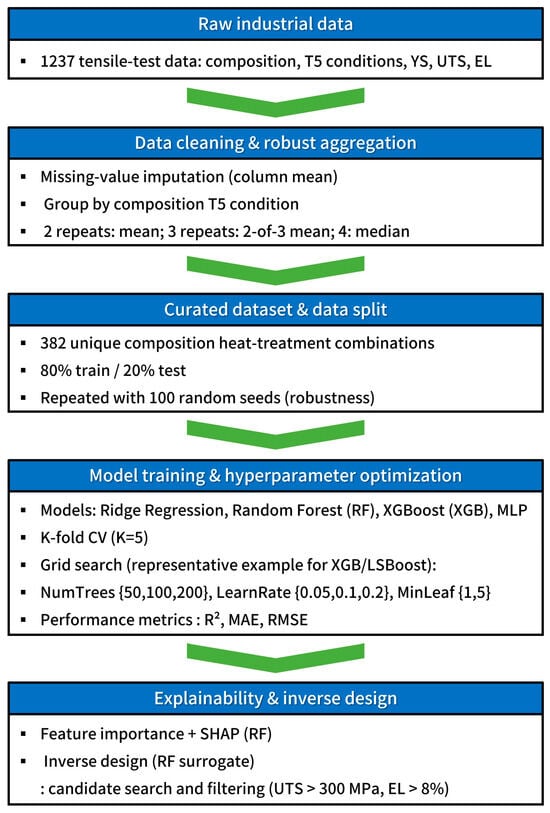

The experimental data preparation and machine learning methodology described in this section constitute a unified data-driven framework, spanning raw industrial data collection, robust statistical aggregation, curated dataset construction, model training and hyperparameter optimization, model evaluation, and subsequent explainability and inverse design analyses. To provide a clear overview of this end-to-end procedure and enhance reproducibility, the entire workflow is schematically summarized in Figure 1, which illustrates the logical sequence and interconnection of the individual steps employed in this study.

Figure 1.

Overall workflow of the proposed data-driven framework.

3. Results and Discussion

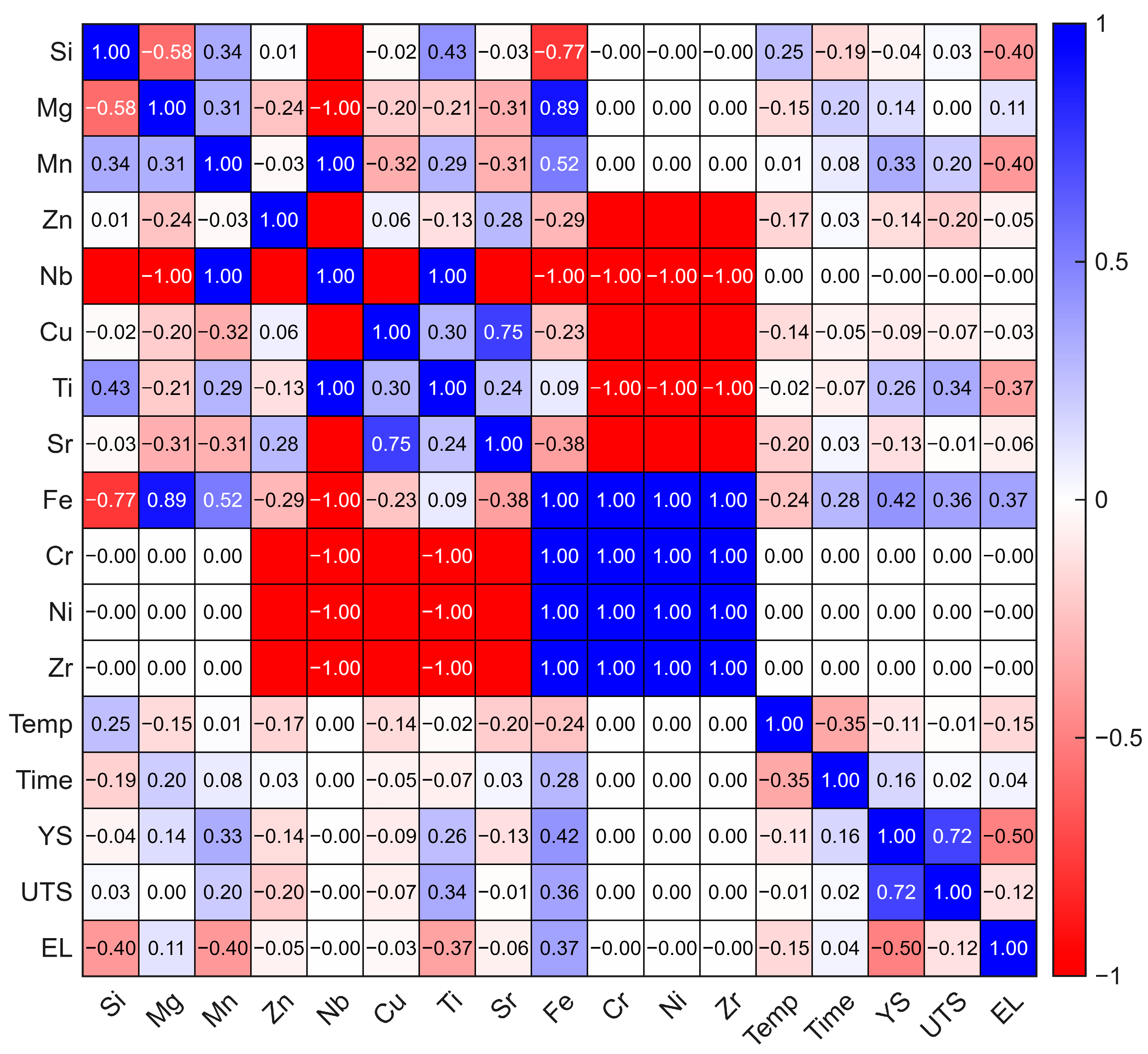

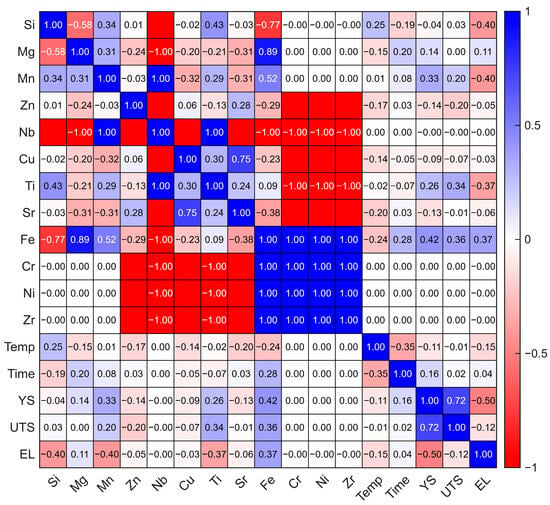

Figure 2 summarizes the Pearson correlations among the alloying variables, T5 aging conditions, and tensile properties of the refined dataset (382 composition–heat-treatment combinations). Several element pairs showed strong positive correlations, including Mg–Fe (0.89), Cu–Sr (0.75), and Mn–Fe (0.52), which likely reflect the recurring industrial alloying practices in die casting. For example, the Mg–Fe correlation may be associated with composition-control strategies in commercial Al–Si–Mg alloys (e.g., coordinated adjustment of Mg with Fe reduction) or raw-material supply characteristics [22]. Negative correlations such as Si–Mg (–0.58) and Si–Fe (–0.77) are consistent with high-Si alloy practice (e.g., Al–9–12Si), where Mg and Fe are often kept comparatively low [23,24,25]. The correlations between composition and T5 parameters were generally weak, suggesting that composition and aging conditions were largely managed independently, although T5 time showed weak positive correlations with Fe (0.42) and Mn (0.33) [26].

Figure 2.

Pearson correlation matrix among alloying elements, T5 heat-treatment parameters, and mechanical properties.

The YS was positively correlated with Mn (0.33) and Fe (0.26), whereas the EL was negatively correlated with Si (–0.40), Mg (–0.11), and Mn (–0.40). These trends are consistent with common cast-alloy behavior, where Mn/Fe-bearing phases can increase the strength but often reduce the ductility [4,27]. The negative Si–EL correlation may be linked to microstructural features at higher Si levels, including a higher porosity propensity, persistence of eutectic Si networks, and increased fractions of brittle constituents [28]. As expected, YS and UTS were strongly correlated (0.72), whereas EL showed negative correlations with UTS (–0.50) and YS (–0.42), reflecting a strength–ductility trade-off [29].

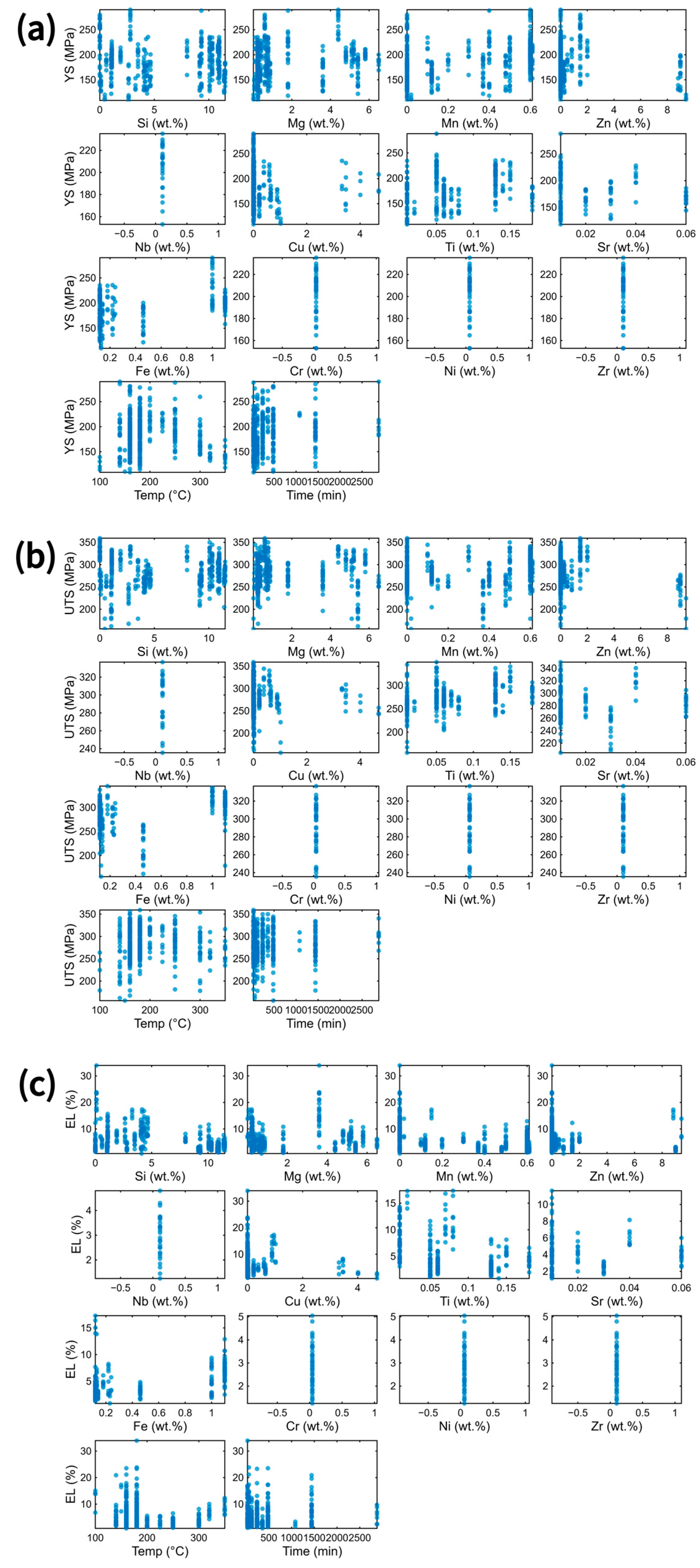

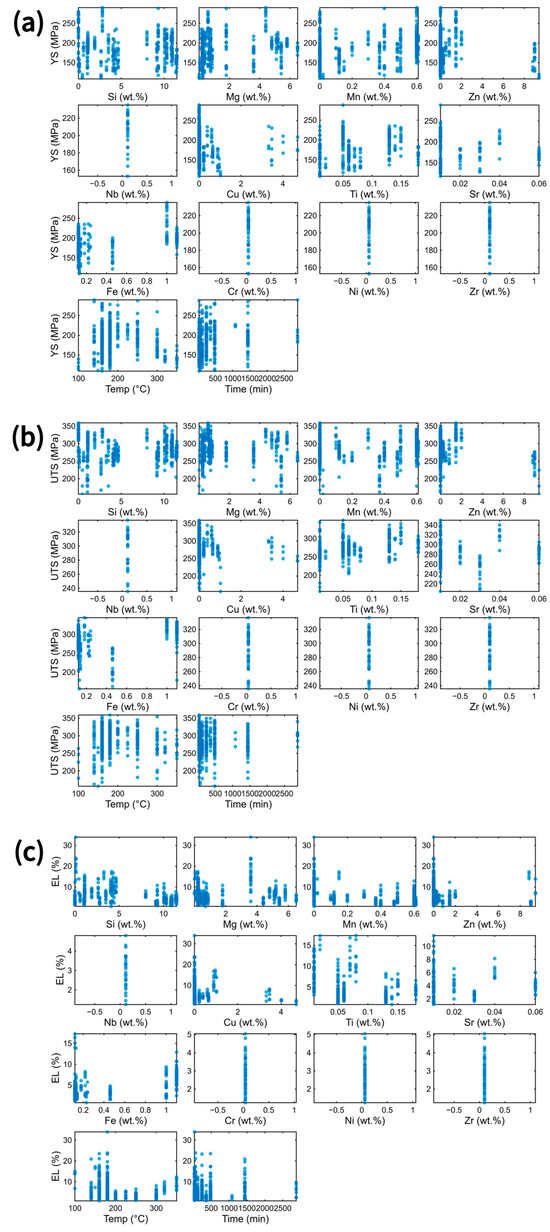

Figure 3 further indicates that none of the tensile properties exhibits a clear monotonic dependence on any single composition or T5 variable, with substantial scatter observed across all inputs. This supports the view that tensile performance in multicomponent HPDC alloys is governed by coupled effects of alloying interactions, as-cast microstructure, and process-induced defects such as microporosity. The similar distributions of YS and UTS are consistent with precipitation-strengthened Al alloys, whereas EL shows broader dispersion and frequent convergence to low values for certain groups [29,30]. These observations suggest that major alloying contents alone (Si, Mg, Cu, Zn) do not fully explain property variation, and that microstructural factors—eutectic Si morphology, Fe/Mn-bearing intermetallics, precipitation/solid-solution behavior, porosity characteristics, and cooling-rate effects—play critical roles [31,32]. The large scatter even under identical T5 conditions also highlights the importance of the as-cast state in T5 processing without solution treatment [33].

Figure 3.

Scatter plots of (a) YS, (b) UTS, and (c) EL as a function of alloying elements and T5 heat-treatment conditions.

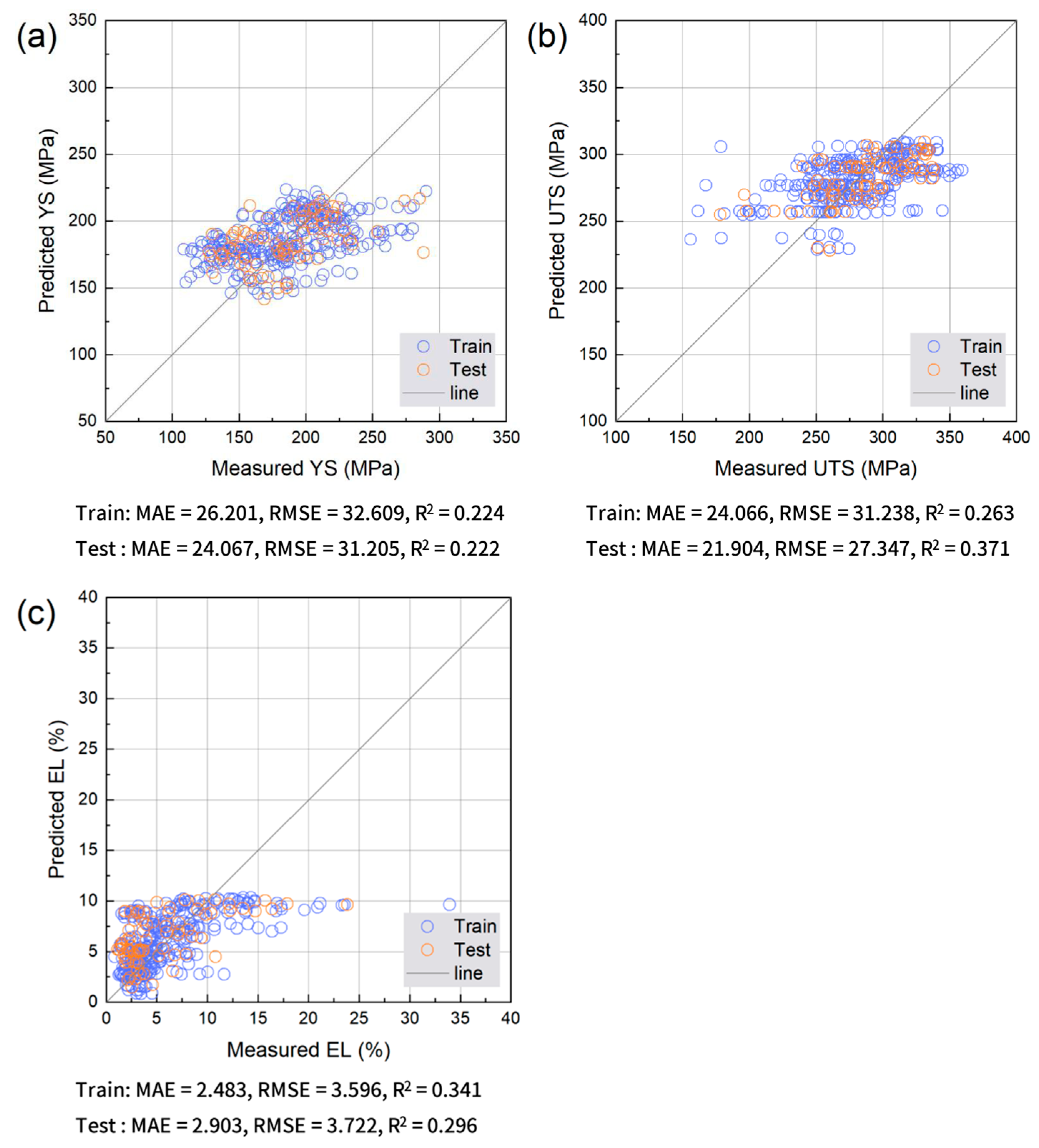

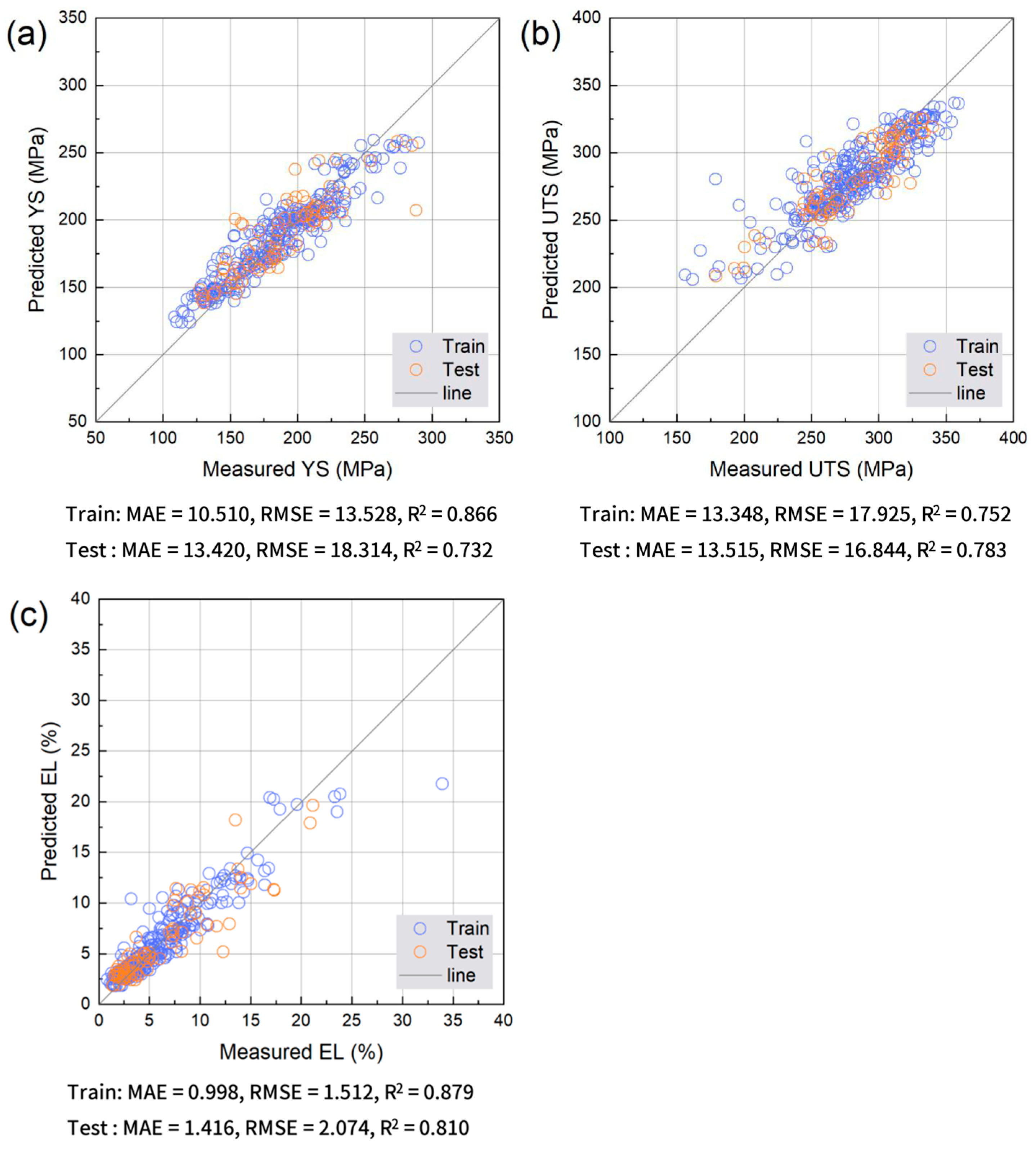

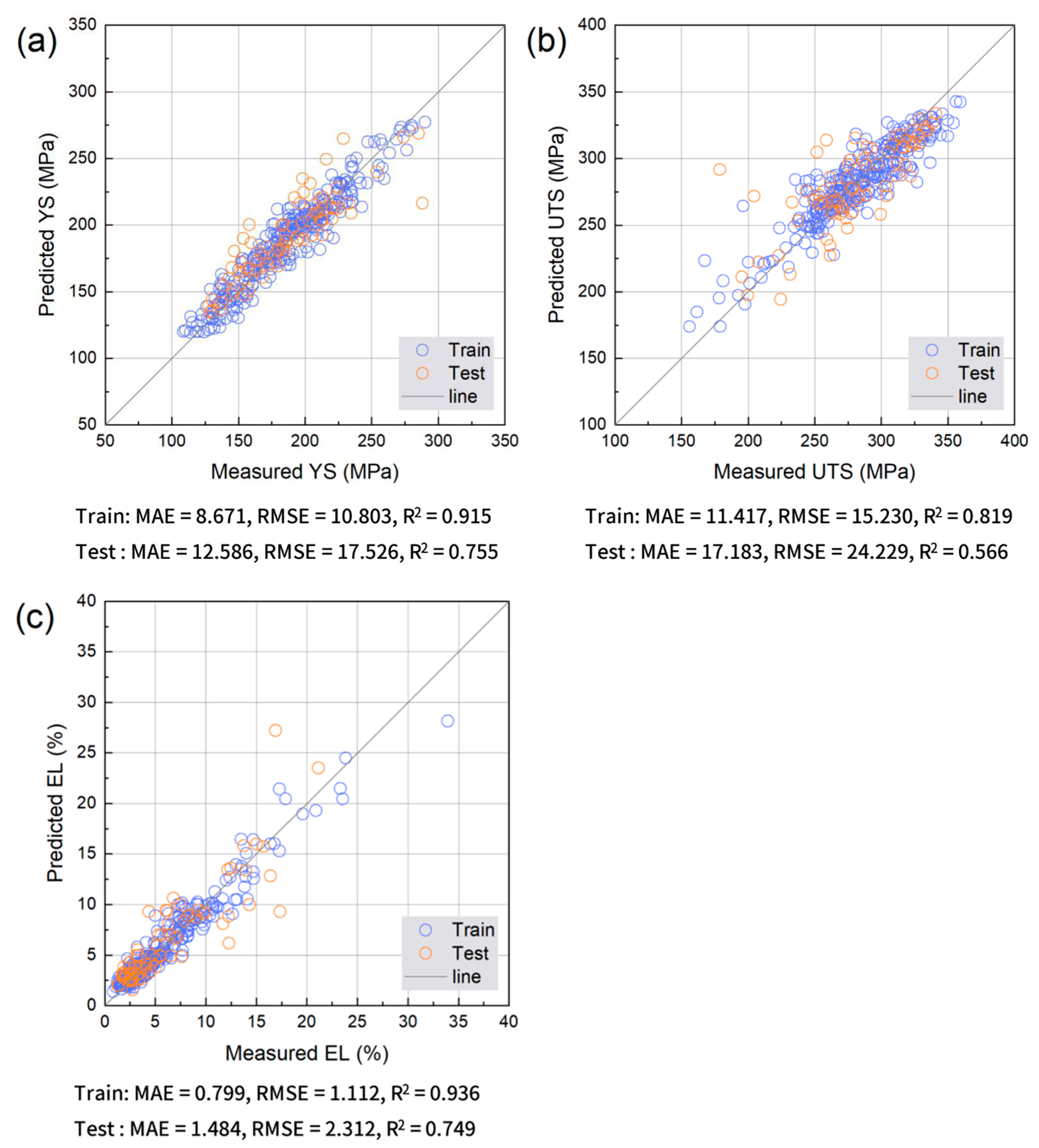

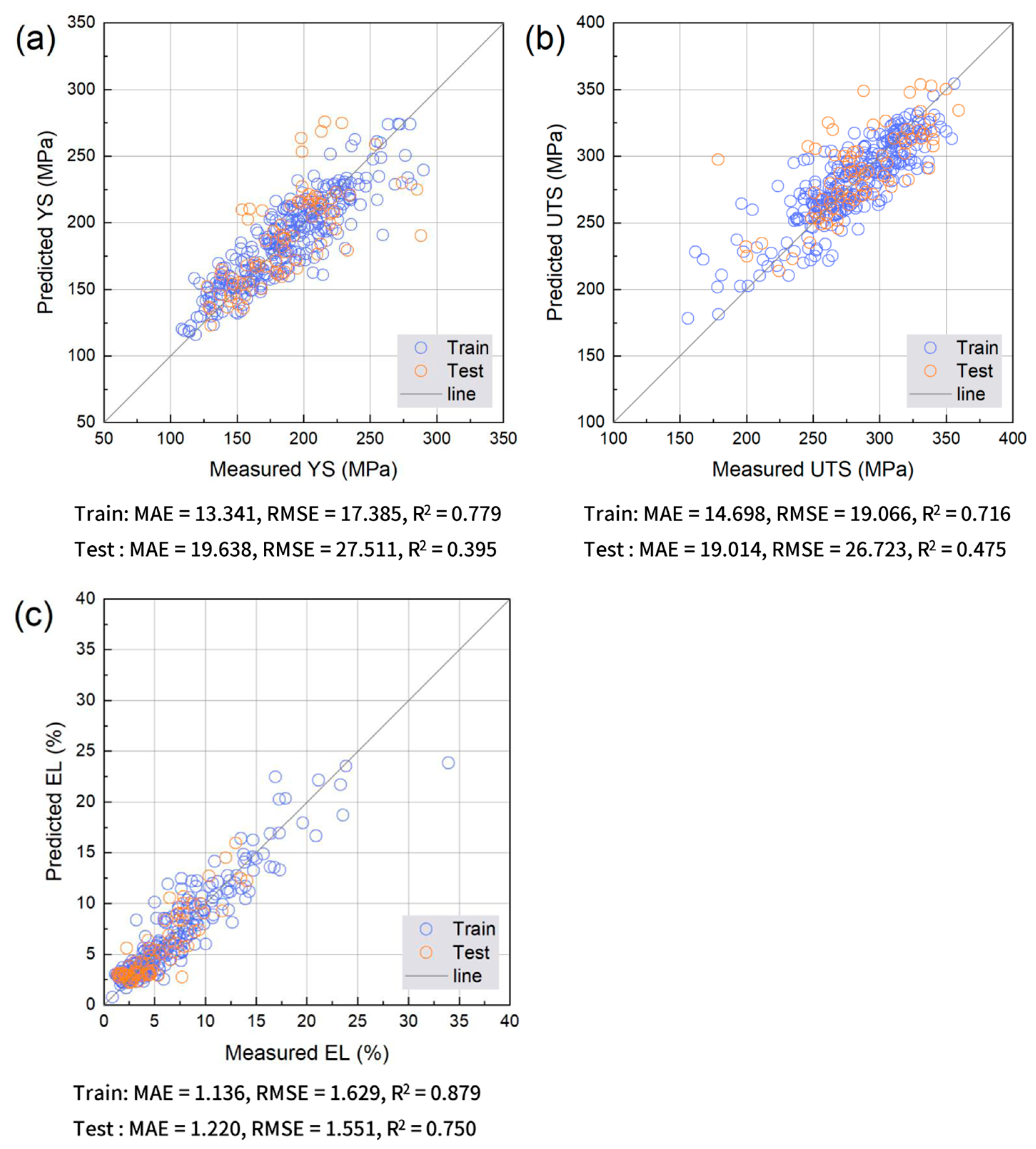

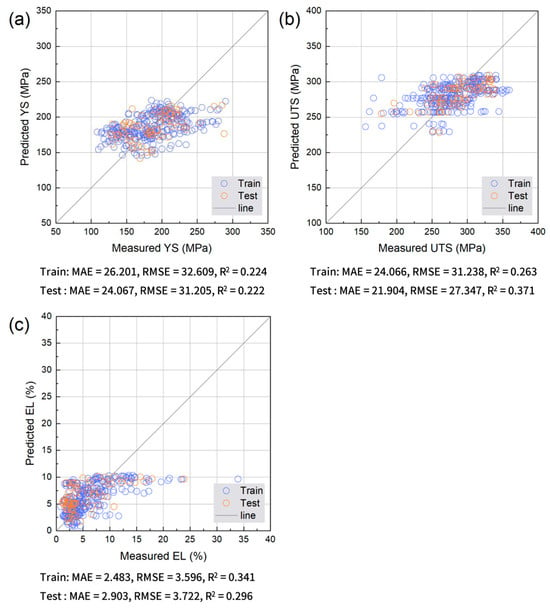

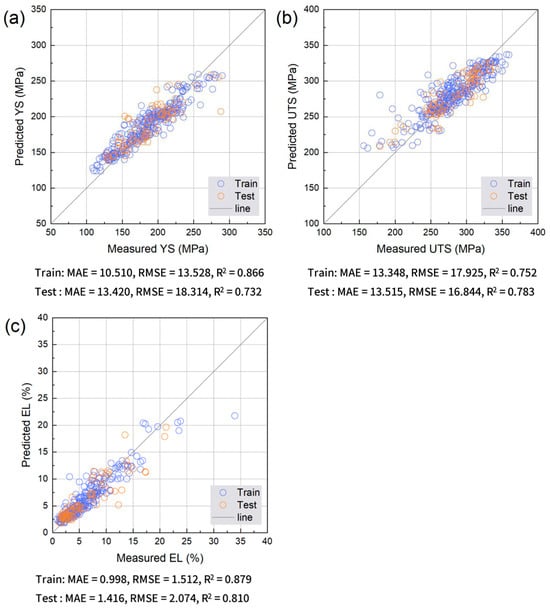

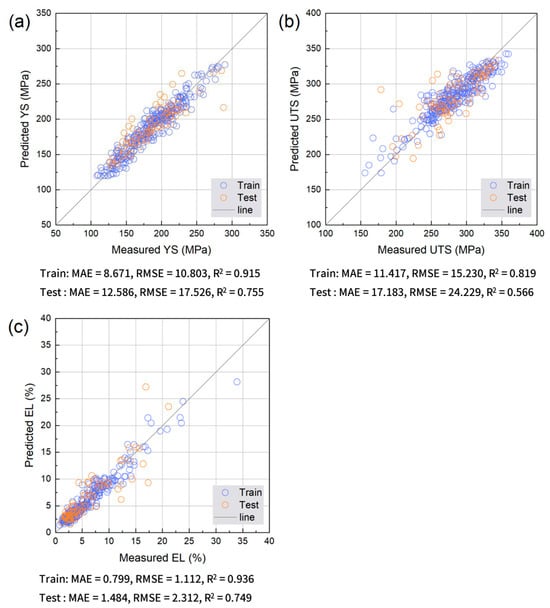

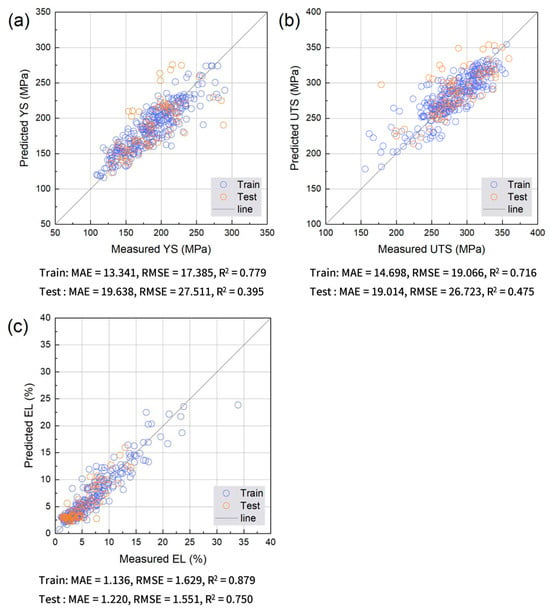

Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 compare the predicted and measured values for the Ridge regression, RF, XGB, and MLP. Ridge regression shows substantial scatter for all targets, with larger deviations in high-strength regimes and a limited ability to reproduce the distribution of EL, indicating that linear models are insufficient for the nonlinear, defect-sensitive behavior of HPDC alloys [16,28]. The RF markedly tightens the distributions around y = x, improving both the strength and ductility predictions, particularly at low EL, where prediction is the most challenging [28]. XGB provides the most compact alignment with the y = x line across targets, with reduced scatter at high YS/UTS and improved EL alignment despite its strong sensitivity to porosity and microstructural factors [28]. MLP improves over Ridge regression but remains less consistent than tree-based ensembles, showing larger dispersion and greater sensitivity in both strength and EL predictions.

Figure 4.

Comparison between measured and predicted (a) YS, (b) UTS, and (c) EL obtained using Ridge Regression. Training and test data points are shown together with the y = x reference line.

Figure 5.

Comparison between measured and predicted (a) YS, (b) UTS, and (c) EL obtained using the Random Forest model. Training and test data points are shown together with the y = x reference line.

Figure 6.

Comparison between measured and predicted (a) YS, (b) UTS, and (c) EL obtained using XGB model. Training and test data points are shown together with the y = x reference line.

Figure 7.

Comparison between measured and predicted (a) YS, (b) UTS, and (c) EL obtained using the MLP neural network. Training and test data points are shown together with the y = x reference line.

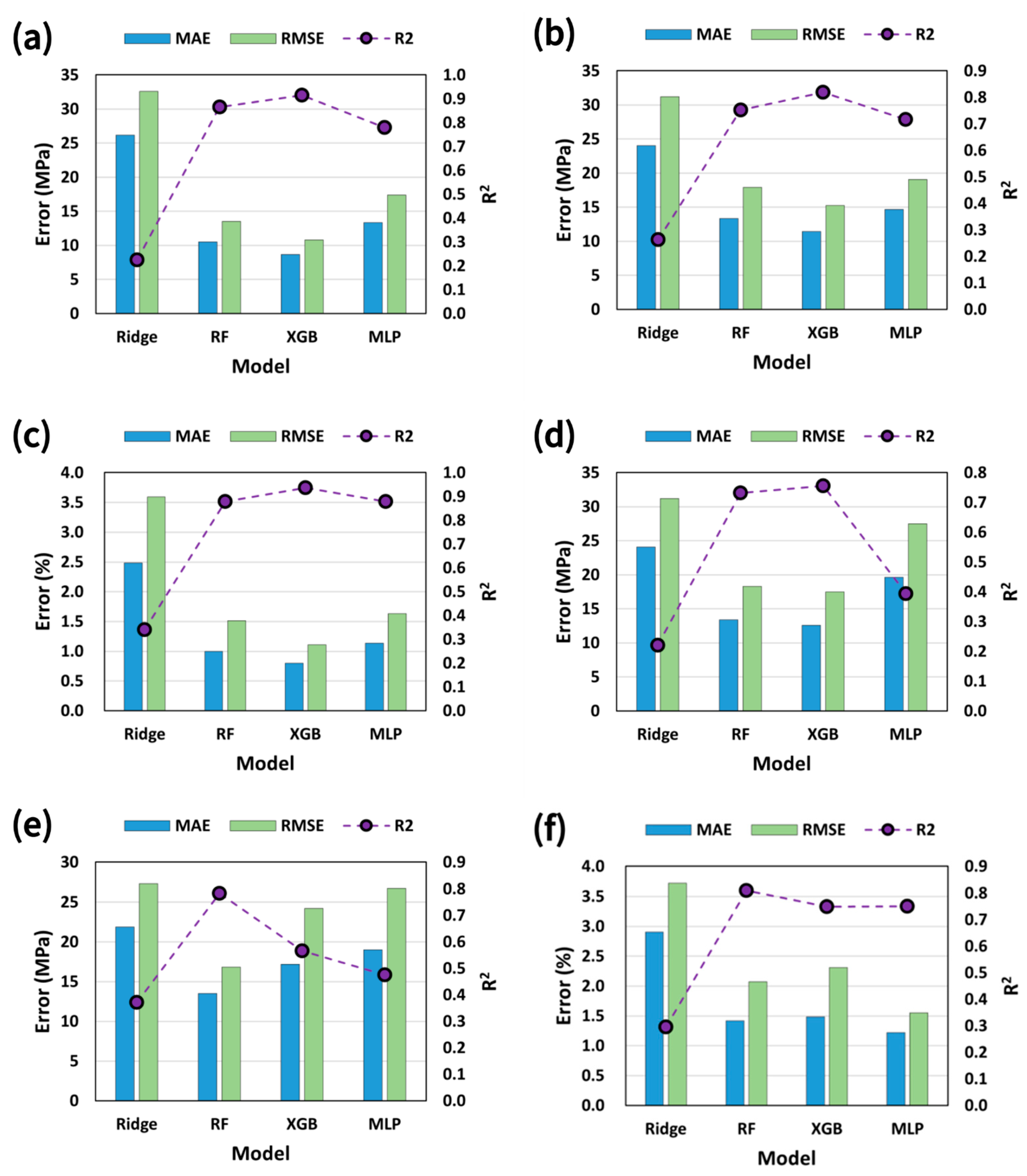

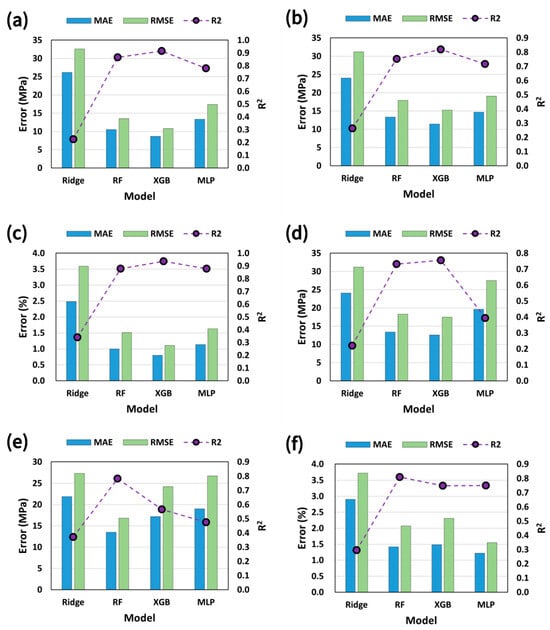

Figure 8 quantifies these trends using the MAE, RMSE, and R2 for the training and test sets. Ridge regression shows the lowest R2 and the highest errors. RF achieves substantially reduced errors with relatively small training–test gaps. XGB provides the best overall performance, showing the lowest errors and highest R2, reflecting its ability to capture nonlinear interactions in the data rather than any specific optimal processing condition. MLP performs better than Ridge regression but is inferior to RF and XGB, particularly for EL. These results align with prior reports that XGBoost can learn complex nonlinear alloy behavior [34] and that RF offers robust performance and interpretable variable-importance measures in multicomponent materials problems [35]. Overall, tree-based ensembles appear to be well suited for industrial HPDC data characterized by microstructural variability and measurement noise.

Figure 8.

Performance comparison of Ridge, Random Forest (RF), XGBoost (XGB), and MLP models in predicting (a,d) YS, (b,e) UTS, and (c,f) EL. Panels (a–c) show MAE, RMSE, and R2 for the training dataset, and panels (d–f) present the corresponding metrics for the test dataset.

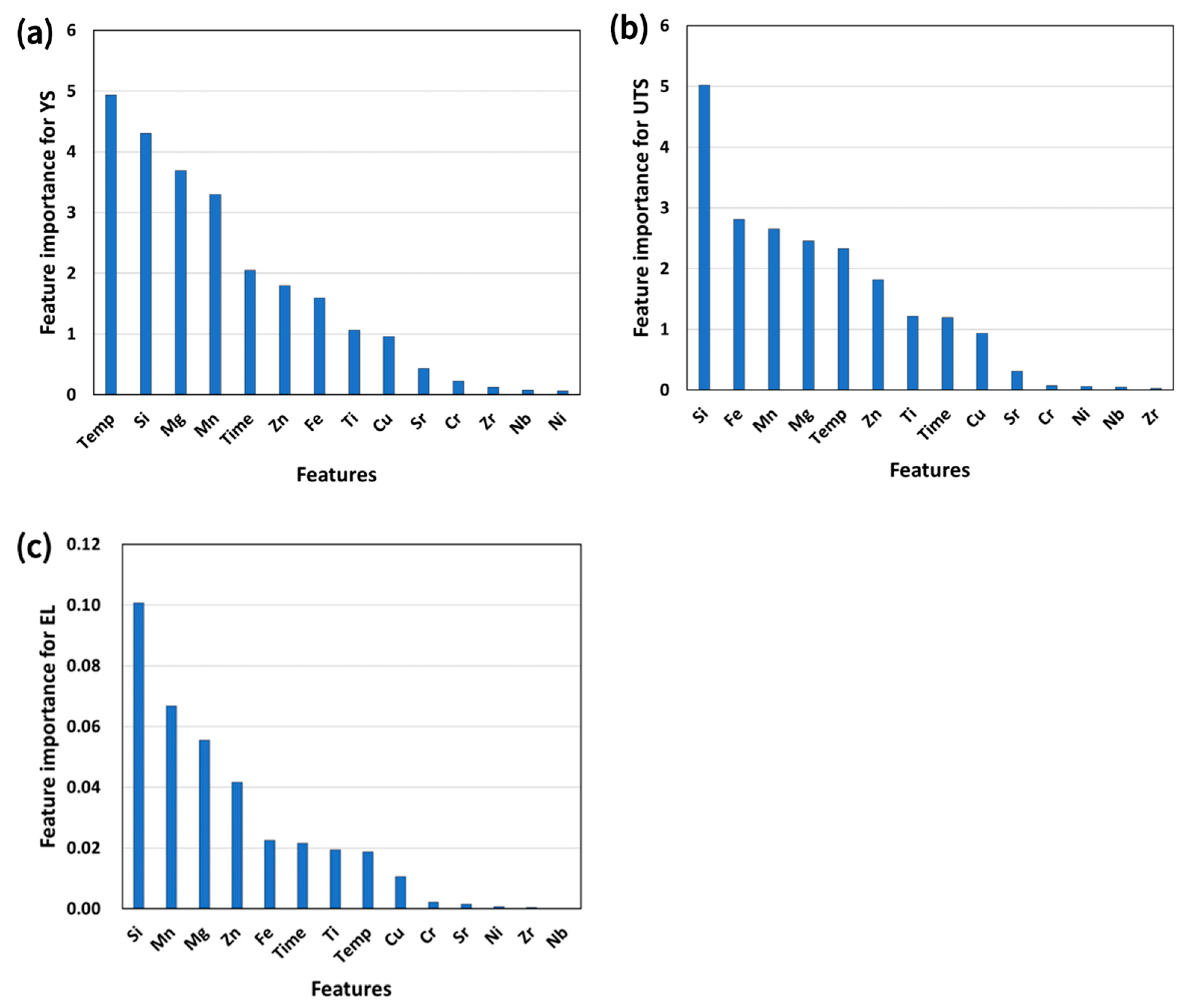

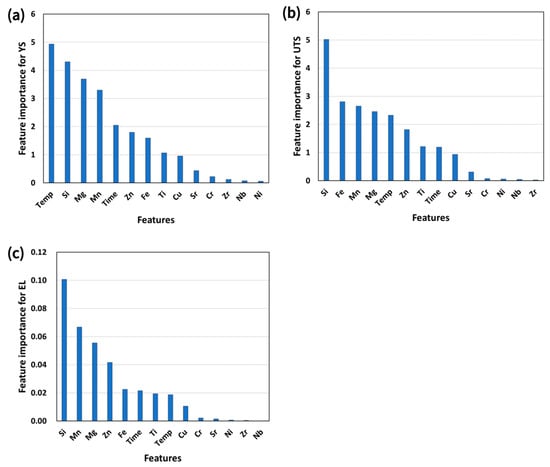

Figure 9 shows the importance of the global features. For the YS, the T5 temperature is the most influential variable, followed by Si, Mg, and Mn, which is consistent with the strong temperature sensitivity of the aging response and contributions from key alloying elements and intermetallic tendencies [36,37]. Minor elements such as Sr, Cr, and Zr are less important, suggesting more indirect effects related to microstructural control than absolute concentration [36,37]. For UTS, Si dominates, followed by Fe, Mn, and Mg, consistent with the influence of eutectic Si and Fe-bearing intermetallics on tensile strength [38,39], and with the known role of Fe-bearing brittle phases (e.g., β-AlFeSi) in die-cast alloys [40]. For elongation (EL), Si and Mn are the most influential, which is consistent with the ductility sensitivity to eutectic Si networks, porosity, and Fe-phase characteristics [28].

Figure 9.

Relative feature importance of alloying elements and T5 heat-treatment parameters for predicting (a) YS, (b) UTS, and (c) EL.

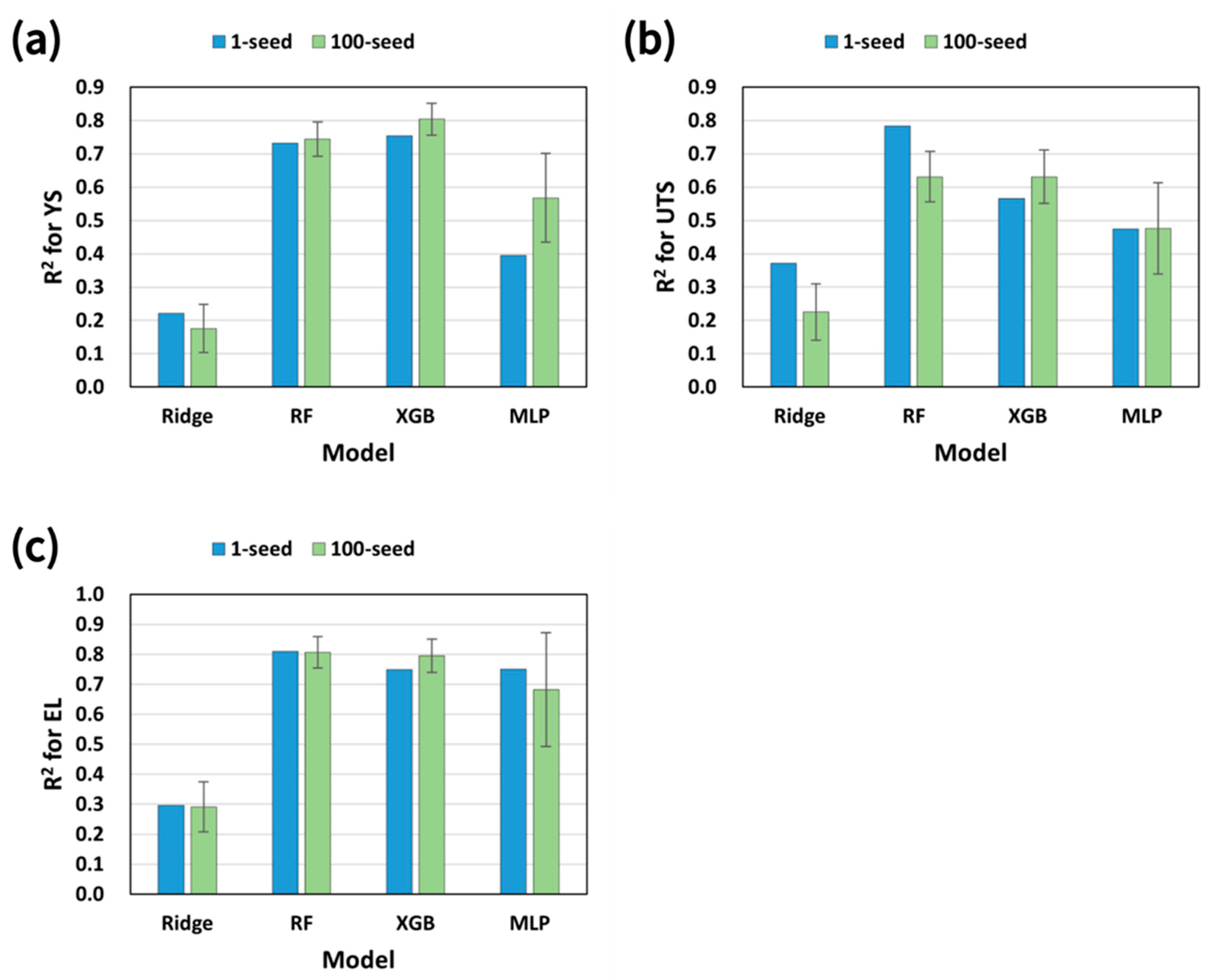

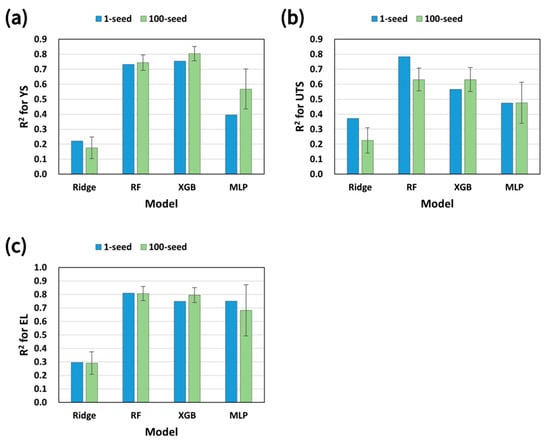

Figure 10 examines the robustness via repeated random training/testing splits. Ridge regression shows low and variable R2 values, whereas RF and XGB maintain high R2 values with small dispersion across seeds. The MLP attains a competitive mean R2 values but exhibits larger variability, indicating greater sensitivity to data partitioning and model initialization. This repeated evaluation supports the practical robustness of tree-based ensembles for noisy industrial datasets.

Figure 10.

R2 comparison of four models (Ridge, RF, XGB, MLP) using 1-seed and 100-seed experiments for predicting (a) YS, (b) UTS, and (c) EL.

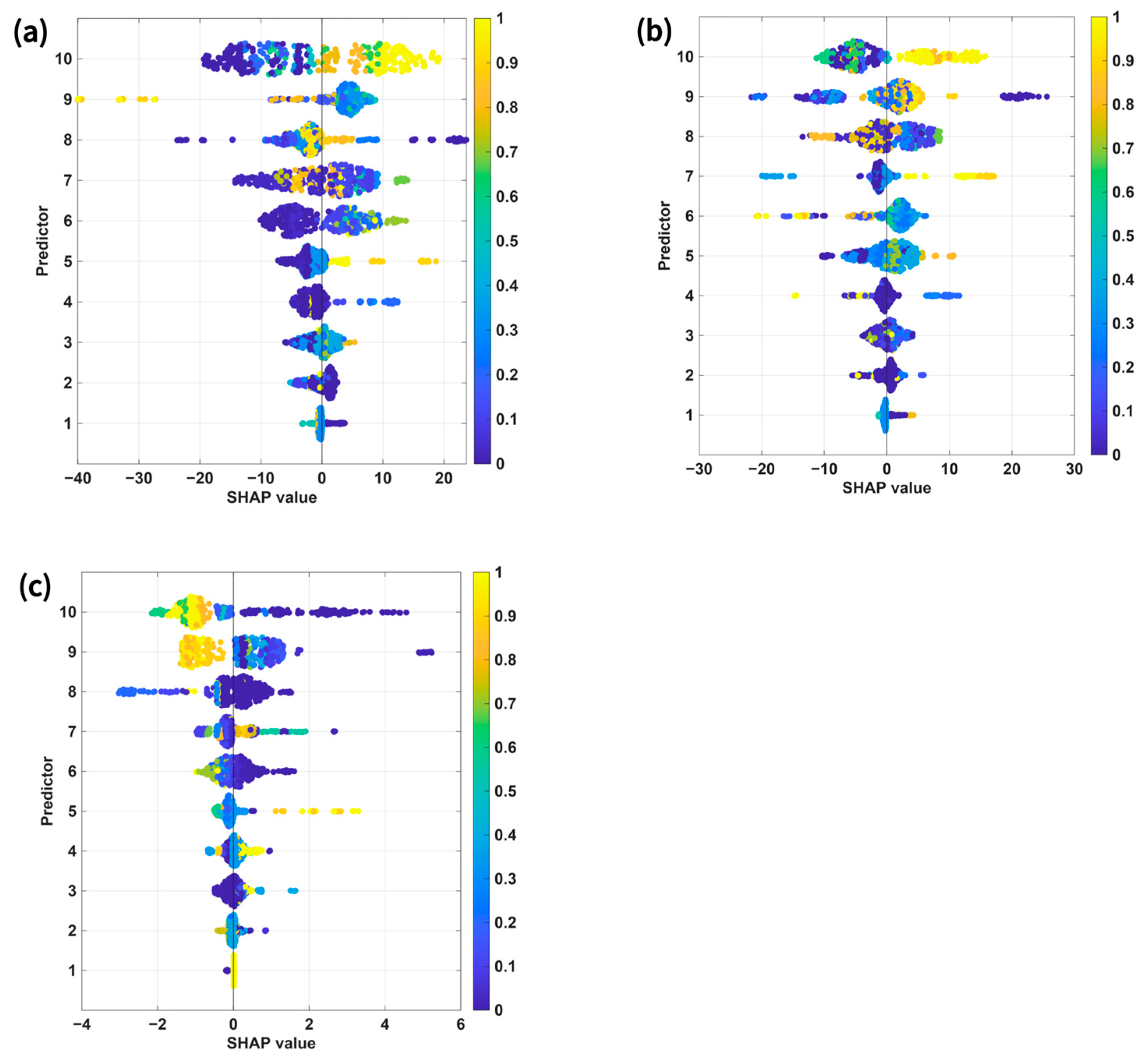

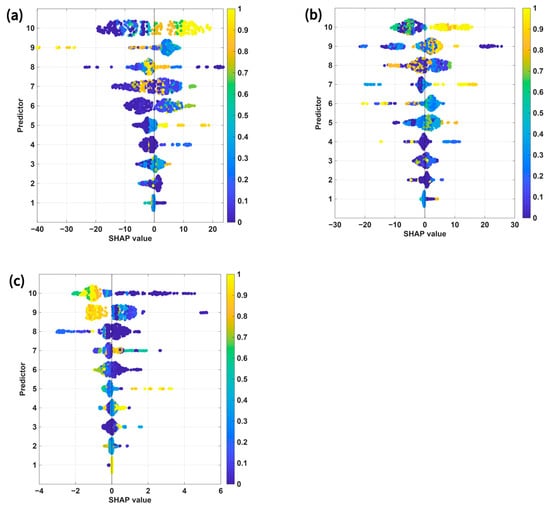

Figure 11 applies SHAP to RF predictions to interpret sample-wise contributions [41]. From a metallurgical standpoint, the SHAP-derived trends can be interpreted in the context of well-established microstructure–property relationships in HPDC aluminum alloys. Mn shows the largest SHAP spread for the YS and UTS, with generally positive contributions at higher Mn levels, which is consistent with its metallurgical role in intermetallic formation and microstructural stabilization [39]. The Mg and T5 temperature also positively contribute to the strength, reflecting age-hardening sensitivity [37]. For the UTS, Si exhibits a clear tendency to increase its contributions at higher values, consistent with eutectic Si effects [8], whereas Fe and temperature show condition-dependent contributions associated with Fe-phase formation and aging response [36,40]. Such condition-dependent SHAP signatures are expected in HPDC alloys, where phase morphology and defect sensitivity strongly interact with processing conditions. For the EL, Mn, Si, and Zn exhibit the largest spreads. A higher Mn content often contributes positively to EL, potentially reflecting the Mn-assisted modification of Fe-bearing phases, although composition- and process-dependent adverse effects are also possible [42]. Mixed SHAP signs for Mg and temperature likely reflect the interplay between precipitation strengthening, strength–ductility trade-off, and porosity/as-cast microstructure sensitivity under T5 conditions [37,43,44]. These interpretations are consistent with reports on Mn-driven β-to-α Fe-phase modification and the existence of an optimal Mn/Fe range [45], as well as Mn-related dispersoid effects under elevated-temperature conditions [46]. The larger SHAP dispersion for the EL than for the strength metrics also agrees with prior observations that microporosity and eutectic Si damage evolution drive ductility scattering in HPDC alloys [47,48].

Figure 11.

SHAP summary (swarm) plots for the Random Forest (RF) model showing the contribution of each variable to the pre-diction of (a) YS, (b) UTS, and (c) EL. Colors indicate normalized feature values, and SHAP values represent the magnitude and direction of each feature’s influence.

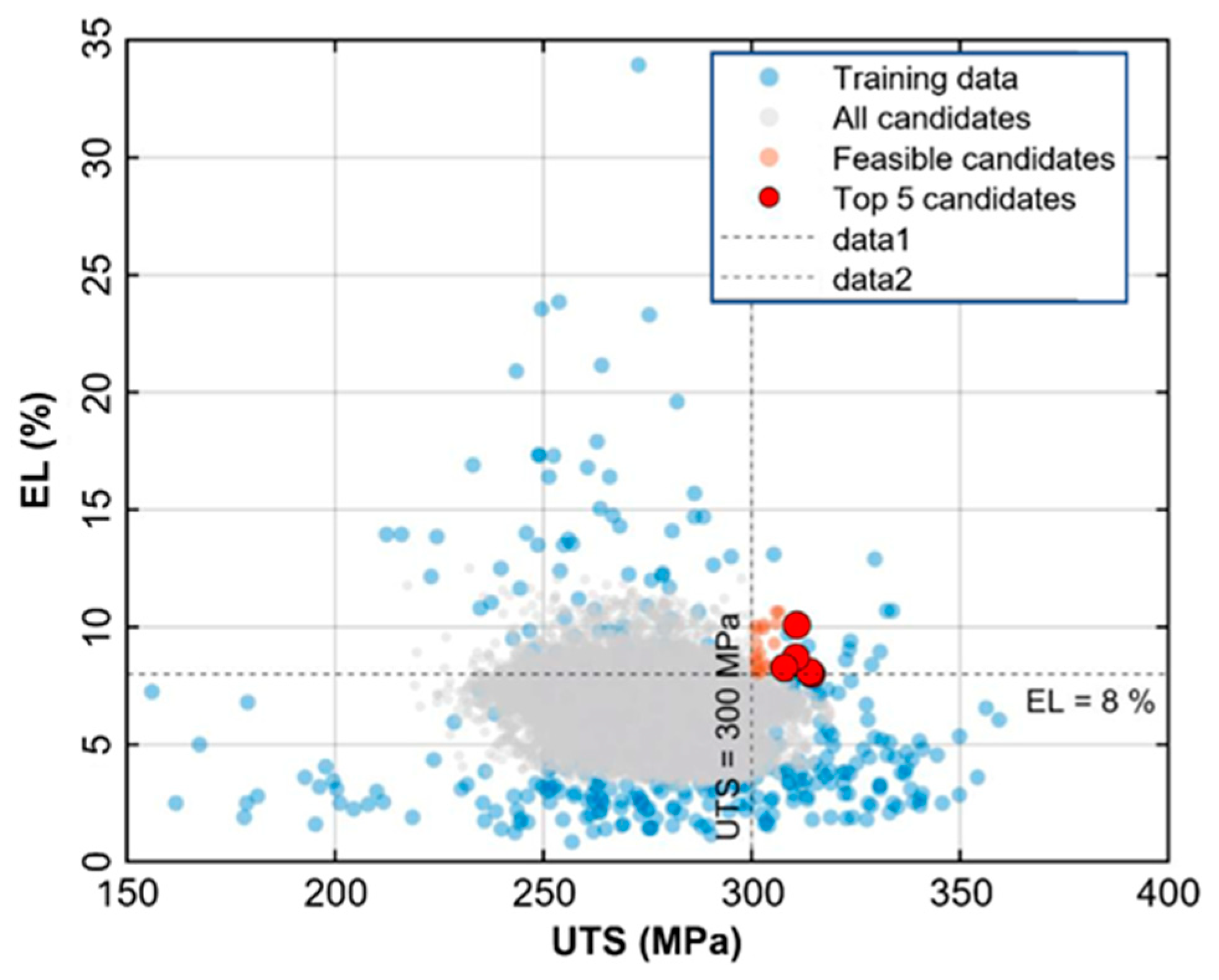

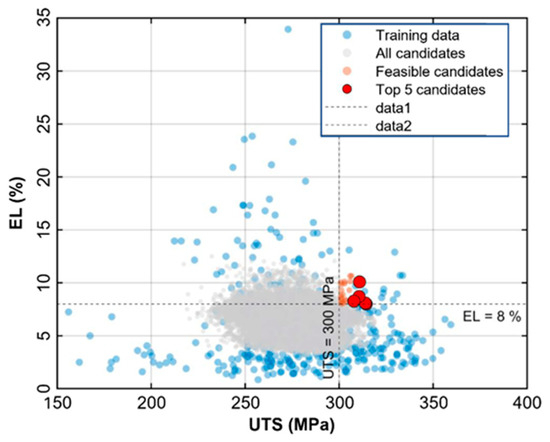

Figure 12 shows the RF-based inverse design for identifying candidates that satisfy UTS > 300 MPa and EL > 8%. As the experimental dataset contained few records that met both constraints, the empirical search was limited. The inverse design results suggest feasible composition–process combinations in sparsely sampled regions, with top candidates clustering around UTS ≈ 300–320 MPa and EL ≈ 8–10%. Although strength–ductility trade-off has been widely reported for Al–Si–Mg and Al–Si–Cu systems [49], the proposed candidates provide practical starting points for targeted experimental validation and further optimization. Table 2 summarizes the top five candidates and their predicted properties. Common tendencies include maintained Mn levels (typically within a narrow range of approximately 0.53–0.59 wt.%) and relatively low Mg variation (around 0.07–0.22 wt.%), while Zn separates into low- and high-Zn groups, suggesting that the surrogate model explores multiple viable strengthening routes, such as solid-solution-dominated and precipitation-assisted strengthening. These results are consistent with previously reported ML-based inverse design strategies [14,15] and extend them to industrial HPDC datasets. It should be noted that the proposed candidates are model-guided design suggestions derived from industrial data, and experimental validation of selected compositions will be pursued in future work.

Figure 12.

Inverse design results using the Random Forest model under the target conditions of UTS > 300 MPa and EL > 8%. Red markers indicate the top 5 candidate compositions satisfying both criteria.

Table 2.

Top five candidate alloy compositions identified by the Random Forest–based inverse design under the target conditions of UTS > 300 MPa and EL > 8%.

4. Conclusions

A large industrial dataset of T5-aged HPDC aluminum alloys (1237 tensile tests) was refined using robust statistical aggregation to construct a curated dataset of 382 unique composition–heat-treatment combinations. Using this dataset, four regression models—Ridge regression, Random Forest (RF), XGB, and MLP—were evaluated to predict yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, and elongation. Tree-based ensemble models (XGB and RF) provided the best overall predictive accuracy and stability, consistently achieving higher test R2 values and lower prediction errors (MAE and RMSE) than linear and neural-network-based models. In contrast, Ridge regression was limited by strong nonlinearity and defect sensitivity, while MLP showed less stable generalization under the present dataset size and variability. Feature-importance and SHAP analyses consistently identified Mn, Si, Mg, Zn, and T5 aging temperature as key variables governing tensile behavior, providing interpretable trends compatible with metallurgical understanding. The RF-based inverse design further suggested new composition–process candidates satisfying UTS > 300 MPa and EL > 8% in regions scarcely represented by experimental data, offering practical starting points for targeted experimental validation and optimization of post-casting processing conditions (i.e., T5 aging temperature and time). Quantitatively, the best-performing tree-based ensemble model achieved test R2 values of approximately 0.866 for YS, 0.752 for UTS, and 0.879 for EL, together with low MAE and RMSE values, demonstrating robust predictive capability against the noise and variability inherent in industrial HPDC data. Based on this model, the top inverse-designed alloy candidates are predicted to exhibit UTS values of approximately 300–320 MPa and elongations of about 8–10%, while maintaining yield strengths on the order of 200–220 MPa, providing concrete and experimentally testable performance targets for future alloy development. Overall, this study presents a reproducible data-driven workflow that integrates robust data refinement, predictive modeling, interpretable analysis, and inverse design, providing a practical route for accelerating composition–process exploration in industrial HPDC aluminum alloys.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K. and S.-J.L.; Methodology, S.C., S.K. and M.L.; Software, J.C.; Investigation, S.C., S.K., J.L., J.C., J.K. and J.-G.J.; Data curation, M.L.; Writing—original draft, S.C.; Writing—review & editing, J.-G.J. and S.-J.L.; Visualization, J.L. and J.-G.J.; Supervision, J.K. and S.-J.L.; Funding acquisition, S.-J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the Jeonbuk RISE Center (Glocal University), funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Jeonbuk State, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-13-JBU).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yang, J.; Liu, B.; Shu, D.; Yang, Q.; Hu, T. Vehicle giga-casting Al alloys technologies, applications, and beyond. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1013, 178552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tian, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, J. Research progress on multi-component alloying and heat treatment of high strength and toughness Al–Si–Cu–Mg cast aluminum alloys. Materials 2023, 16, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.W.; Lee, J.Y.; Cho, Y.H.; Jang, J.I.; Kim, S.B.; Lee, J.M. Enhanced mechanical properties and homogeneous T5 age-hardening behavior of Al-Si-Cu-Mg casting alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 960, 170982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Yang, W.; Gao, F.; Watson, D.; Fan, Z. Effect of iron on the microstructure and mechanical property of Al–Mg–Si–Mn and Al–Mg–Si diecast alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 564, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhlouf, M.M.; Guthy, H.V. The aluminum–silicon eutectic reaction: Mechanisms and crystallography. J. Light Met. 2001, 1, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.G.; Rooy, E.L. Aluminum Alloy Castings: Properties, Processes, and Applications; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Yuan, S.; Wang, W.; Gan, P.; Ji, J.; Zeng, J. Effect of short solution and artificial ageing on microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-Si-Mg-La-Ce alloy formed by high pressure die casting. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1020, 179436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Kwon, Y.N.; Lee, S. Effects of eutectic silicon particles on tensile properties and fracture toughness of A356 aluminum alloys fabricated by low-pressure-casting, casting-forging, and squeeze-casting processes. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 461, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lordan, E.; Dou, K.; Wang, S.; Fan, Z. Influence of porosity characteristics on the variability in mechanical properties of high pressure die casting (HPDC) AlSi7MgMn alloys. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 56, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramprasad, R.; Batra, R.; Pilania, G.; Mannodi-Kanakkithodi, A.; Kim, C. Machine learning in materials informatics: Recent applications and prospects. npj Comput. Mater. 2017, 3, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, K.T.; Davies, D.W.; Cartwright, H.; Isayev, O.; Walsh, A. Machine learning for molecular and materials science. Nature 2018, 559, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P.; Ji, X.; Li, M.; Lu, W. Small data machine learning in materials science. npj Comput. Mater. 2023, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Seo, N.; Son, S.B.; Lee, S.J.; Jung, M. Application of machine learning algorithms and SHAP for prediction and feature analysis of tempered martensite hardness in low-alloy steels. Metals 2021, 11, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y. Inverse design of materials by machine learning. Materials 2022, 15, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, F.; Ward, L.; Williams, T.; Laws, K.J.; Wolverton, C.; Hattrick-Simpers, J.; Mehta, A. Accelerated discovery of metallic glasses through iteration of machine learning and high-throughput experiments. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaaq1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoerl, A.E.; Kennard, R.W. Ridge regression: Applications to nonorthogonal problems. Technometrics 1970, 12, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hornik, K. Approximation capabilities of multilayer feedforward networks. Neural Netw. 1991, 4, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinomiya, Y.; Yamamoto, J.; Kato, K.; Ono, H.; Yamaguchi, K.; Komori, K. Thermodynamics of formation of Al3Fe inter-metallic compound for Fe removal from molten Al–Mg alloy. Mater. Trans. 2023, 64, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crepeau, P.N. Effect of iron in Al-Si casting alloys: A critical review (95–110). AFS Trans. 1995, 103, 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Rheinfelden. Primary Aluminium Casting Alloys, Datasheet L 2.06/3-KH. Available online: https://www.foundry-planet.com/fileadmin/redakteur/Material/08-03-10-Leporello_engl.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Riestra, M. High Performing Cast Aluminium-Silicon Alloys. Ph.D. Dissertation, School of Engineering, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Chang, C.S.T.; Wanderka, N.; Banhart, J.; Hirsch, J. The Effect of Fe, Mn and Trace Elements on Precipitation in Al-Mg-Si Alloy. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Aluminium Alloys, Yokohama, Japan, 5–9 September 2010; pp. 492–497. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, C.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Z. Effect of Si on Fe-rich intermetallic formation and mechanical properties of heat-treated Al–Cu–Mn–Fe alloys. J. Mater. Res. 2018, 33, 898–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Ling, S. Microstructure and mechanical properties of hypo/hyper-eutectic Al–Si alloys synthesized using a near-net shape forming technique. J. Alloys Compd. 1999, 287, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, B.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.Z.; Chen, C.X.; Wang, H.T.; Liu, F. Breaking through the strength-ductility trade-off dilemma in an Al-Si-based casting alloy. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Yu, F.; Zhao, D. Aging Behavior and Precipitates Analysis of Wrought Al-Si-Mg Alloy. Materials 2022, 15, 8194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajkowski, M.; Bernat, Ł.; Hajkowski, J. Mechanical properties of Al-Si-Mg alloy castings as a function of structure refinement and porosity fraction. Arch. Foundry Eng. 2012, 12, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zheng, J.; Godlewski, L.; Zindel, J.; Li, M.; Li, W.; Huang, S. Influence of pore characteristics and eutectic particles on the tensile properties of Al–Si–Mn–Mg high pressure die casting alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 783, 139280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.B.; Lee, J.M.; Koo, T.M.; Lee, S.U.; Lee, J.Y.; Son, K.S.; Cho, Y.H. Influence of cooling condition after solidification on T5 heat treatment response of hypoeutectic Al-7Si-0.4 Mg casting alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 906, 164339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peivaste, I.; Jossou, E.; Tiamiyu, A.A. Data-driven analysis and prediction of stable phases for high-entropy alloy design. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.; Konnur, T.; Chattopadhyay, P.P.; Pal, S. Structure prediction of multi-principal element alloys using ensemble learning. Eng. Comput. 2020, 37, 1003–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.T.; Lin, J.X.; Wu, X.P.; Niu, L.Y.; Li, G.Y. The Effect of Sr Modification on the Microstructure and Properties of Mg2Si Reinforced Near-Eutectic Al-Si Alloy. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 750, 638–641. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Chen, S.; Dong, Q.; Qin, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, B.; Nagaumi, H. Tailoring microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-Mg-Si-Cu alloy with varying Mn and/or Cr additions. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 892, 146053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, D.U.; Kim, M.S. Experimental investigation on tensile properties and yield strength modeling of T5 heat-treated counter pressure cast A356 aluminum alloys. Metals 2021, 11, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cinkilic, E.; Huang, X.; Wang, G.G.; Liu, Y.C.; Weiler, J.P.; Luo, A.A. Optimization of T5 heat treatment in high pressure die casting of Al–Si–Mg–Mn alloys by using an improved Kampmann-Wagner numerical (KWN) model. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 865, 144604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Blake, P.; Dou, K.; Ji, S. Strengthening die-cast Al-Mg and Al-Mg-Mn alloys with Fe as a beneficial element. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 732, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.Y.; Park, T.Y.; Han, S.W.; Lee, H.M. Effects of Mn on the crystal structure of α-Al (Mn, Fe) Si particles in A356 alloys. J. Cryst. Growth 2006, 291, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurdjevic, M.; Manasijević, S.; Patarić, A.; Stopić, S.; Mihailović, M. Impact of Mg on the Feeding Ability of Cast Al–Si7–Mg (0_0.2_0.4_0.6) Alloys. Crystals 2024, 14, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lordan, E.; Zhang, Y.; Dou, K.; Jacot, A.; Tzileroglou, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Patel, J.; Lazaro-Nebreda, J.; Zhou, X.; et al. High-pressure die casting: A review of progress from the EPSRC future lime hub. Metals 2022, 12, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.Y.; Doty, H.W.; Kaufman, M.J. The effects of Mn additions on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Al–Si–Cu casting alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 488, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhmonov, J.; Liu, K.; Rometsch, P.; Parson, N.; Chen, X.G. Effects of Al(MnFe)Si dispersoids with different sizes and number densities on microstructure and ambient/elevated-temperature mechanical properties of extruded Al–Mg–Si AA6082 alloys with varying Mn content. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 861, 157937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. Effects of Damage Evolution of Eutectic Si Particle and Microporosity to Tensile Property of Al-xSi Alloys. J. Korea Foundry Soc. 2021, 41, 434–444. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, C.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Ryu, J.H.; Kim, H.J. Mechanical and Die Soldering Properties of Al-Si-Mg Alloys with Vacuum HPDC Process. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Aluminium Alloys, Yokohama, Japan, 5–9 September 2010; pp. 1768–1773. [Google Scholar]

- Dons, A.L.; Heiberg, G.; Voje, J.; Mæland, J.S.; Løland, J.O.; Prestmo, A. On the effect of additions of Cu and Mg on the ductility of AlSi foundry alloys cast with a cooling rate of approximately 3 K/s. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 413, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.