1. Introduction

Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy sheets, owing to their lightweight nature, high strength, and excellent corrosion resistance, find widespread application in lightweight engineering fields, including aerospace, automotive, and rail transportation [

1,

2]. However, they exhibit poor formability at room temperature and low forming precision [

3,

4]; thus, they are mostly shaped via hot stamping technology [

5,

6]. The hot deformation process of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy is extremely complex. Strain hardening and dynamic softening during hot deformation exert significant influences on the microstructure and properties of the alloy post-forming. Temperature and strain rate play pivotal roles in the hot deformation mechanisms that govern the microstructure and properties of aluminum alloys [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Constitutive equations, which quantitatively describe the deformation capacity of metallic materials under varying temperatures, strain rates, and other conditions through mathematical language [

13,

14], stand as an irreplaceable model in the calculation of deformation forces and simulating hot deformation processes [

15,

16,

17]. Consequently, investigating the hot deformation behavior of aluminum alloys and establishing their constitutive equations hold great significance. Constitutive models can be broadly classified into phenomenological models, micro-mechanism models, and artificial neural network models [

18,

19]. Owing to its high precision and operational convenience, the Arrhenius constitutive model has been widely adopted [

20].

The Arrhenius constitutive model offers advantages in characterizing the influences of temperature, strain rate, and strain on metals during high-temperature deformation processes, making it widely applicable for predicting hot deformation behavior and optimizing processing parameters. In recent years, modifying the Arrhenius constitutive model to adapt to the deformation characteristics of different metallic materials has become a significant research focus. Enhancements to the Arrhenius model have concentrated on strain compensation, parameter coupling, and the integration of microscopic mechanisms, substantially improving its prediction accuracy and physical significance.

Researchers abroad have conducted numerous studies on the intrinsic equations governing the high-temperature deformation of aluminum alloy sheets. Frequently, Arrhenius-type equations are employed to describe the behavior, incorporating a strain rate sensitivity factor, material parameters, and activation energy. These models are typically designed for specific temperature and strain rate ranges that apply to high-temperature deformation conditions. To enhance accuracy, many research teams have further refined traditional intrinsic models by introducing internal variables such as dynamic recrystallization, particle slip, and other mechanisms to better represent materials’ behavior under different conditions.

Liu et al. [

21] investigated the hot tensile deformation behavior and microstructure evolution of a 7075 aluminum alloy sheet. Through the establishment of a hyperbolic sine Arrhenius constitutive equation, the authors investigated the fracture morphology and microstructural evolution. The findings revealed that the activation energy for hot deformation of the alloy is 132.52 kJ/mol. Furthermore, with increasing deformation temperature or decreasing strain rate, the softening mechanism of the alloy transitions from dynamic recovery to dynamic recrystallization. Long et al. [

22] developed a strain compensation model for an Al–Cu–Li alloy via isothermal compression tests. They employed a fifth-order polynomial to fit the strain-dependent parameters, achieving a mean absolute relative error of only 4.65%. The superiority of the model was demonstrated through comparative verification with the Johnson–Cook and Zerilli–Armstrong models. Additionally, the influence of particle-stimulated nucleation (PSN) induced by coarse second-phase particles was analyzed. Gong et al. [

23] proposed a strain-compensated Arrhenius model for a magnesium alloy but highlighted that the material parameters are influenced by multiple factors, necessitating a move beyond reliance solely on strain. Wang et al. [

24] optimized the constitutive model for 2219-O aluminum alloy through friction and temperature correction, proposing a modified model with a simpler structure. Its prediction accuracy was comparable to that of the strain compensation model, and the reliability of the hot forming simulation was verified via secondary development in DEFORM-3D. Xia et al. [

25] compared the strain compensation (SC), genetic algorithm (GA), and K function modification (KM) models for 2A12-T4 aluminum alloy, finding that the KM model achieved the highest accuracy due to its coupling of temperature and strain rate effects, thereby extending the applicability of the modification methods. Furthermore, Yu et al. [

26] developed an Arrhenius model incorporating the Zener–Hollomon (Z) parameter for an Al–Mg–Si–Ce–B alloy to describe dynamic recovery (DRV) and continuous dynamic recrystallization (CDRX) behaviors. The softening mechanisms were validated by TEM/EBSD, and the model successfully identified unstable deformation regions under conditions of low temperature and high strain rate. Shi et al. [

27] enhanced the correlation coefficient of the model for an Al–Cu–Mn alloy to 96.2% through strain compensation and analyzed the regulatory effects of DRV and nano-precipitates on the flow stress.

In summary, the current core refinements of the Arrhenius constitutive model are manifested in the following aspects: (1) strain compensation: enhancing the characterization of parameter evolution with strain through polynomial fitting; (2) integration of the Z-parameter: coupling temperature and strain rate effects to improve the model’s universality across diverse deformation conditions [

28]; (3) incorporation of microscopic mechanisms: integrating mechanisms such as dynamic recrystallization (DRX) and dynamic recovery (DRV) to enhance physical significance [

29]; and (4) experimental correction: reducing errors through friction/temperature correction or model comparison. These improvements have significantly enhanced the model’s predictive accuracy for flow stress, providing a more reliable theoretical tool for optimizing hot working processes (such as finite element simulation) and microstructural control.

Most existing Arrhenius constitutive equations for the high-temperature deformation of aluminum alloys are primarily developed for high-temperature compression. The specimens used in high-temperature compression tests are cylindrical, and during compression, the fracture strain is less sensitive to deformation conditions, resulting in a wide strain range of experimental data. However, for high-strength aluminum alloy sheets at elevated temperatures, the fracture strain is significantly affected by deformation conditions—under certain conditions, the fracture strain is relatively small, leading to a narrow strain range of experimental data. Since the fitting of constitutive equation parameters in existing models relies on polynomial fitting, which only considers the effect of strain while ignoring the influences of temperature and strain rate, the constitutive equations exhibit high prediction accuracy only within the strain range of the experimental data, whereas beyond this strain range, the prediction accuracy deteriorates sharply. Consequently, the applicable strain range of existing constitutive equations is limited, which is insufficient to predict the flow stress of high-strength aluminum alloys during actual production processes.

This study focuses on investigating the flow behavior of rare-earth aluminum alloys through hot tensile tests conducted under different temperatures and strain rates. It analyzes the effects of strain rate, strain, and deformation temperature on the material parameters of these alloys and proposes a strain-compensated Arrhenius constitutive equation. Furthermore, through error analysis, a modified model to predict flow stress under diverse conditions has been developed. Currently, the strain-compensated Arrhenius constitutive model is widely adopted for describing the high-temperature deformation behavior of aluminum alloys. However, for rare-earth aluminum alloys, this model can only characterize the true stress–strain curves within a strain of 0.085. In actual hot stamping processes, the material deformation strain often exceeds 0.085, which limits the engineering application of the conventional strain-compensated Arrhenius constitutive equation. In contrast, the modified Arrhenius constitutive model developed in the present work is capable of precisely depicting the flow stress within the scope of experimental data and extrapolating to those outside the experimental data range. This broadens the strain range for characterizing the high-temperature deformation behavior of the material, thereby providing a theoretical basis for the numerical simulation of actual hot stamping processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.R.; Methodology, H.R. and Q.Z.; Software, H.R.; Validation, H.R.; Formal analysis, H.R.; Investigation, H.R., Q.Z. and B.D.; Resources, F.S.; Data curation, F.S. and K.C.; Writing—original draft, H.R.; Writing—review & editing, B.D.; Visualization, K.C. and Q.Z.; Supervision, B.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Fuzhen Sun, Keqian Cai and Quanda Zhang were employed by the company Beijing National Innovation Institute of Lightweight Ltd. and He Ren is a student of the same company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, L.; Hou, Y.; Li, Z. Enhancing mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of a high strength 7A99 Al alloy by introducing pre-rolling in solution and aging treatments. J. Alloys Compd. Interdiscip. J. Mater. Sci. Solid-State Chem. Phys. 2022, 898, 162972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, X.; Cao, L.; Liao, B.; Liu, Q. Hot deformation and dynamic recrystallization in Al-Mg-Si alloy. Mater. Charact. 2021, 173, 110976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Pang, Q.; Lu, J.; Hu, Z. Comparative study on deformation behavior, microstructure evolution and post-forming property of an Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy in a novel warm forming process. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 312, 117854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, H. Microstructure evolution and mechanical responses of Al–Zn–Mg–Cu alloys during hot deformation process. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 13429–13478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Dong, Y.; Zheng, J.-H.; Foster, A.; Lin, J.; Dong, H.; Dean, T.A. The effect of hot form quench (HFQ®) conditions on precipitation and mechanical properties of aluminium alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 761, 138017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Lin, J.; Ganapathy, M.; Dean, T. Experimental and modelling techniques for hot stamping applications. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 15, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, X.-M. A critical review of experimental results and constitutive descriptions for metals and alloys in hot working. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 1733–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, H.; Abbasi, S.; Momeni, A.; Taheri, A.K. On the constitutive modeling and microstructural evolution of hot compressed a286 iron-base superalloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 564, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-H. Effect of strain rate and deformation temperature on strain hardening and softening behavior of pure copper. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2016, 26, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Qiu, W. Microstructure evolution and hot deformation behavior of Cu-3Ti-0.1Zr alloy with ultra-high strength. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2020, 30, 2737–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Han, M.; Zhang, K.; Lu, Z. Effects of sintering temperature on microstructure evolution and hot deformation behavior of tial-based alloys prepared by spark plasma sintering. JOM 2018, 70, 2739–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Fu, S.H.; Wang, T.; Zhao, Y.X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.C. Microstructure evolution and processing map of superalloy gh720li during isothermal compression. Mater. Sci. Forum 2013, 747–748, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, X.-M.; Wen, D.-X.; Chen, M.-S. A physically-based constitutive model for a typical nickel-based superalloy. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2014, 83, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, B.; Ye, L.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Lin, H.; Dong, Y.; Liu, X. Hot deformation behavior and 3D processing maps of aa7020 aluminum alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 845, 156113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.-P.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.-Z.; Zhou, C.-X.; Xu, G.-F. Constitutive relationship for high temperature deformation of powder metallurgy Ti–47Al–2Cr–2Nb–0.2W alloy. Mater. Des. 2012, 37, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Xia, Y.-C.; Chen, X.-M.; Chen, M.-S. Constitutive descriptions for hot compressed 2124-t851 aluminum alloy over a wide range of temperature and strain rate. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2010, 50, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-A.; Qin, G.; Wang, H.; Geng, P. Constitutive modeling and dynamic recrystallization mechanism elaboration of fgh96 with severe hot deformation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 21, 2947–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhu, C.; Li, S.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, P.; Yang, R.; Zhao, S. A comparative study on modified and optimized zerilli-armstrong and arrhenius-type constitutive models to predict the hot deformation behavior in 30Si2mncrmove steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 3918–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, D.; Mandal, S.; Bhaduri, A. A comparative study on johnson cook, modified zerilli–armstrong and arrhenius-type constitutive models to predict elevated temperature flow behaviour in modified 9Cr–1Mo steel. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2009, 47, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Hamada, A.; Patnamsetty, M.; Borek, W.; Gouda, M.; Chiba, A.; Ebied, S. Constitutive modeling and hot deformation processing map of a new biomaterial Ti–14Cr alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 4097–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Shan, Z.; Li, X.; Zang, Y. Hot tensile deformation behavior and microstructure evolution of 7075 aluminum alloy sheet. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 724–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.; Wu, D.-X.; Wang, S.-Y.; Jiang, Y.-P.; Xia, R.-Z.; Li, S.-S.; Zhou, Y.-T.; Peng, P.; Dai, Q.-W. An optimized constitutive model and microstructure characterization of a homogenized Al-Cu-Li alloy during hot deformation. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 929, 167290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; He, Y.-B.; Zhang, T.; Chen, K.; Wu, Y.-X.; Zhang, X.-L.; Liu, X.-L. Modified constitutive behavior model of Mg-10Gd-3Y-0.4Zr alloy during high-temperature deformation process. J. Cent. South Univ. 2023, 30, 2458–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qin, G.; Li, C. A modified arrhenius constitutive model of 2219-O aluminum alloy based on hot compression with simulation verification. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 3302–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Shu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Pater, Z.; Li, Z.; Xu, H.; Ma, Z.; Xu, C. Modified arrhenius constitutive model and simulation verification of 2A12-T4 aluminum alloy during hot compression. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 1325–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Pan, Q.; Wang, W.; Huang, Z.; Xiang, S.; Liu, B. Dynamic softening mechanisms and zener-hollomon parameter of Al–Mg–Si–Ce–B alloy during hot deformation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 6395–6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Zhang, F.; He, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Gao, W.; Li, Z. Constitutive equation and dynamic recovery mechanism of high strength cast Al-Cu-Mn alloy during hot deformation. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cheng, Z.; Yu, W.; Wang, G.; Zhou, J.; Cai, Q. Deformation Behavior and Constitutive Equation of 42CrMo Steel at High Temperature. Metals 2021, 11, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Wang, W.; Ma, S.; Yan, H.; Mu, Z.; Zhang, S. Arrhenius constitutive model and dynamic recrystallization behavior of 18CrNiMo7-6 steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 6334–6347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Initial microstructure of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Er alloy sheet.

Figure 2.

Dimensions of test specimen.

Figure 3.

Thermocouple welding position.

Figure 4.

Specimen clamping method.

Figure 5.

Schematic illustrations of isothermal tensile.

Figure 6.

Flow stress curves of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Er alloy under different temperatures: (a) 623 K; (b) 673 K; (c) 723 K.

Figure 7.

The amount of peak stress influenced by lg(έ) and temperature.

Figure 8.

OM images under different deformation conditions.

Figure 9.

Relationship between (a) lnέ − σ; (b) lnέ − lnσ; (c) lnέ − ln[sinh(ασ)]; and (d) 1/T − ln[sinh(ασ)].

Figure 10.

Relationships between material parameters: (a) α; (b) n; (c) Q; (d) lnA; and true strain ε by polynomial fitting.

Figure 11.

Measured stress values (curves) and predicted values obtained from the strain-compensated Arrhenius constitutive equation (dots): (a) 623 K; (b) 673 K; (c) 723 K; (d) correspondence between measured and calculated flow stress values.

Figure 12.

Changes in α(ε, T) (a) with respect to T and ε; (b) 3D graphical representation of α(ε, T) through curved surface fitting.

Figure 13.

(a) Variation in v(ε, έ) with respect to true strain and strain rate; (b) 3D graphical representation of v(ε, έ) through curved surface fitting; (c) variation in w(ε, έ) with respect to true strain and strain rate; (d) 3D graphical representation of w(ε, έ) through curved surface fitting.

Figure 14.

Variation in H(η) with true strain, strain rate, and temperature.

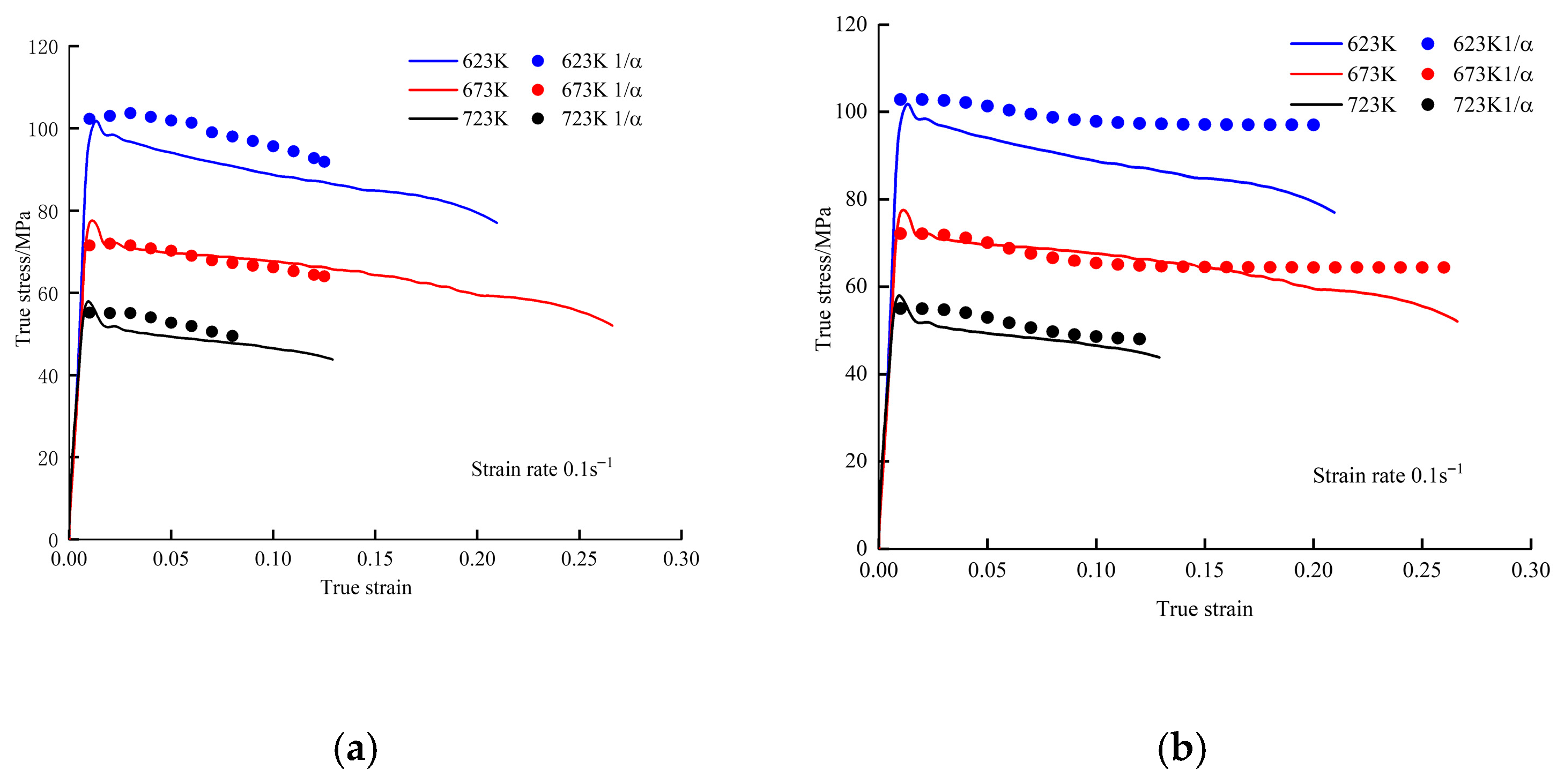

Figure 15.

(a) Comparisons between 1/α calculated based on experimental data and experimented flow stresses; (b) comparisons between 1/α calculated based on fitting function and experimented flow stresses.

Figure 16.

Measured stress values (curves) and predicted values obtained from the modified Arrhenius constitutive equation (dots): (a) 623 K; (b) 673 K; (c) 723 K; (d) correspondence between measured and calculated flow stress values.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Er alloy sheet.

| Alloy | Zn | Mg | Cu | Zr | Fe | Si | Ti | Cr | Mn | Er |

|---|

| Al-Zn-Mg-Cu-Er alloy | 8.316 | 2.334 | 2.041 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.083 | 0.049 | 0.041 | 0.011 | 0.11 |

Table 2.

Coefficients of polynomial for material parameters.

| Coefficients | Value | Coefficients | Value |

|---|

| A0 | 0.01314 | C0 | 151.61552 |

| A1 | −0.01252 | C1 | 4347.57528 |

| A2 | 0.72539 | C2 | −454,465.27 |

| A3 | −4.0323 | C3 | 1.7959 × 107 |

| B0 | −102.41871 | C4 | −3.38551 × 108 |

| B1 | 6.04561 | C5 | 3.09378 × 109 |

| B2 | −102.41871 | C6 | −1.1019 × 1010 |

| B3 | 3292.59742 | D0 | 26.43138 |

| B4 | −58,910.527 | D1 | 302.86983 |

| B5 | 595,130.31 | D2 | −44,819.331 |

| | | D3 | 1.92077 × 106 |

| | | D4 | −3.95504 × 107 |

| | | D5 | 3.5217 × 108 |

| | | D6 | −1.283 × 109 |

Table 3.

Fitting equation coefficient of α.

| Coefficients | Value |

|---|

| E0 | 0.00815 |

| E1 | 1.67628 × 10−4 |

| E2 | 0.05769 |

| E3 | 0.02272 |

| E4 | 0.01564 |

| E5 | 673.69858 |

| E6 | 60.81226 |

| E7 | 0.00413 |

Table 4.

Fitting equation coefficient of v.

| Coefficients | Value |

|---|

| F0 | −1.1472 |

| F1 | 8.28338 |

| F2 | −1.05712 |

| F3 | −0.45491 |

| F4 | 0.06915 |

| F5 | 9.82289 |

Table 5.

Fitting equation coefficient of w.

| Coefficients | Value |

|---|

| G0 | 2.37765 |

| G1 | −13.22238 |

| G2 | 2.21982 |

| G3 | 8.64514 |

| G4 | −0.02316 |

| G5 | −14.79753 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |