Aging Kinetics and Activation Energy-Based Modeling of Electrical Conductivity Evolution in a Cu–4Ti Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

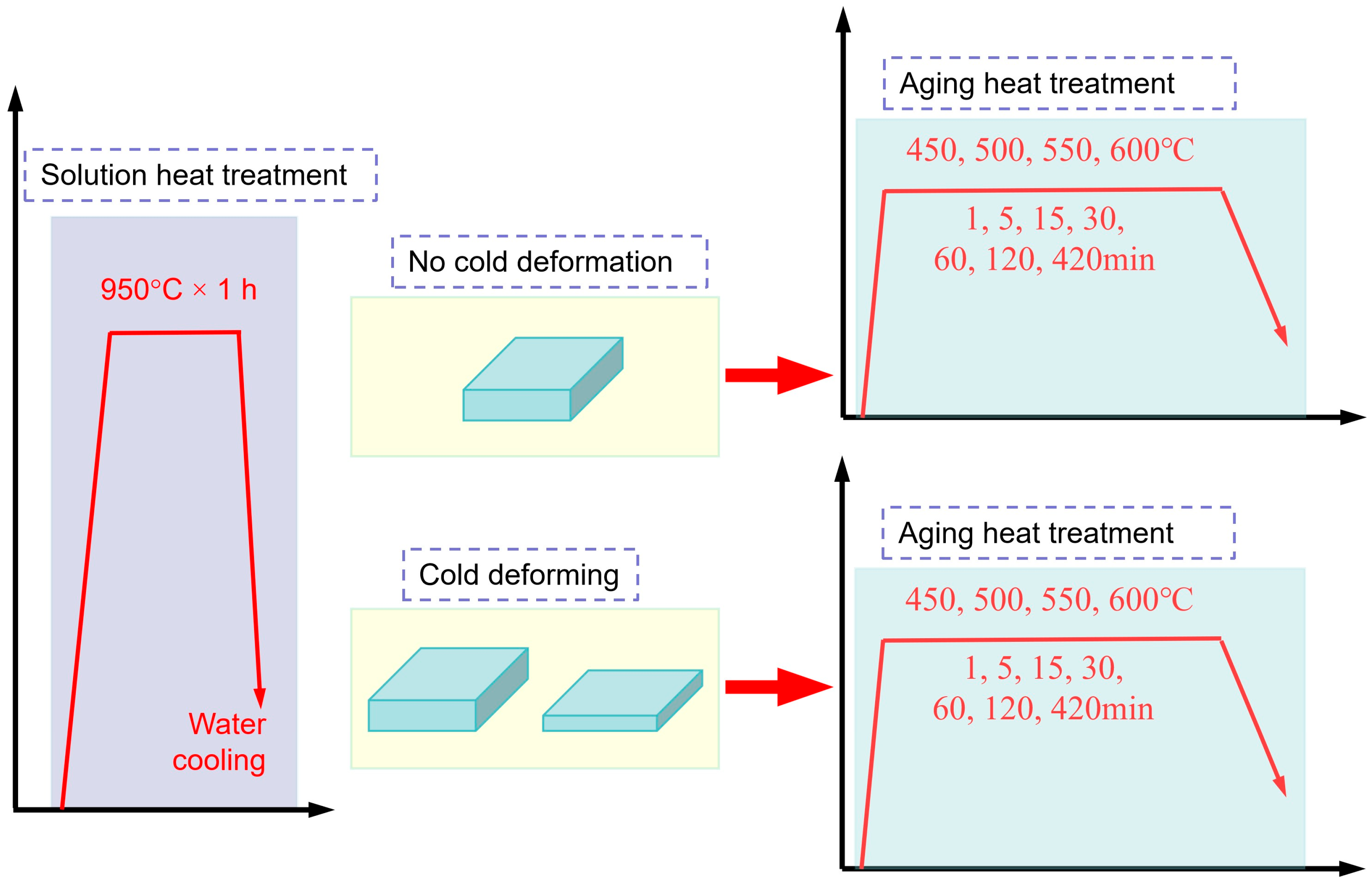

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

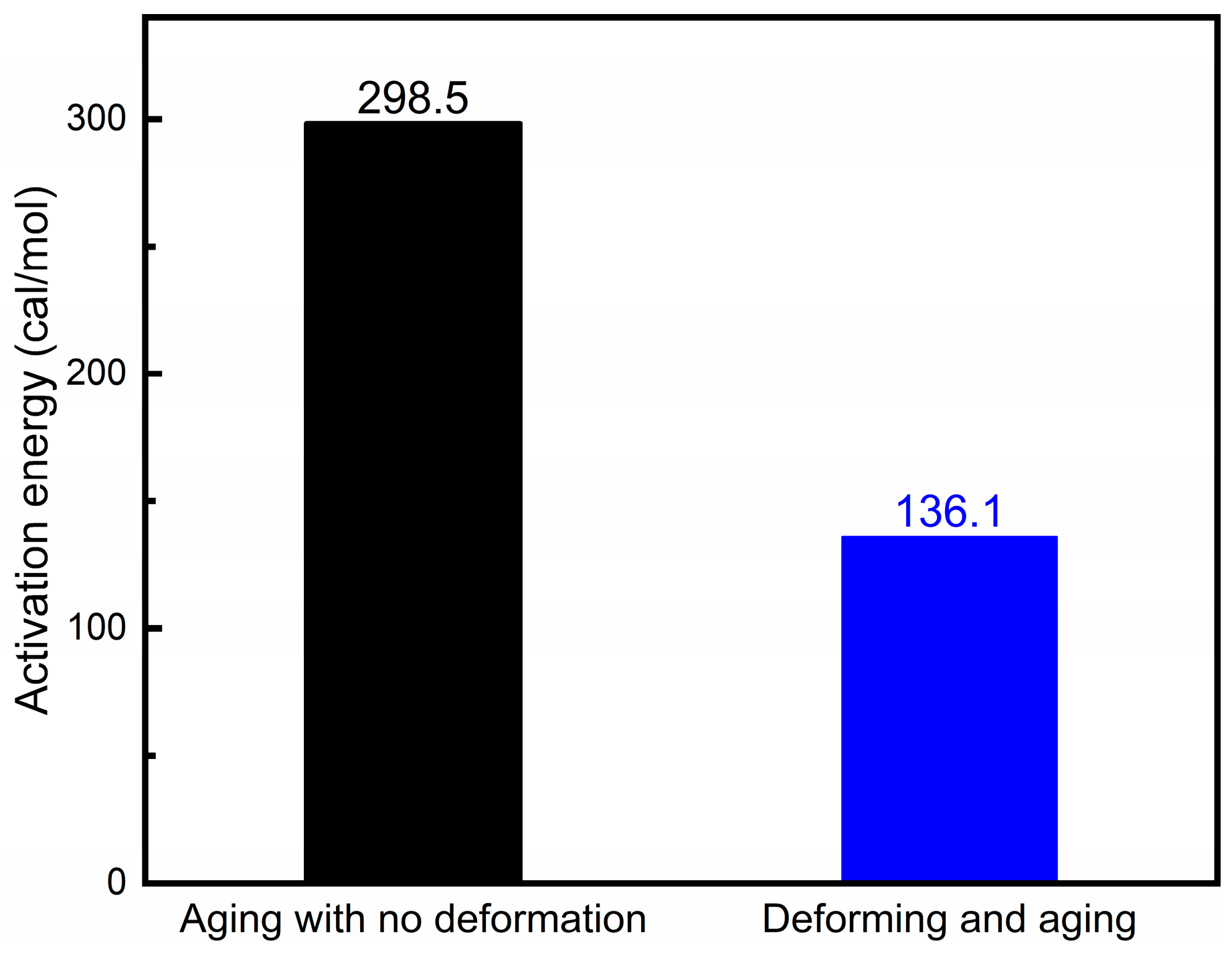

3. Activation Energy Determination for Aging of Cu–4Ti Alloys

3.1. Rationale and Overview

3.2. Calculation of Activation Energy During Aging Heat Treatment [27,28,29]

3.3. Statistical Determination of Activation Energy for Cu–4Ti Alloy

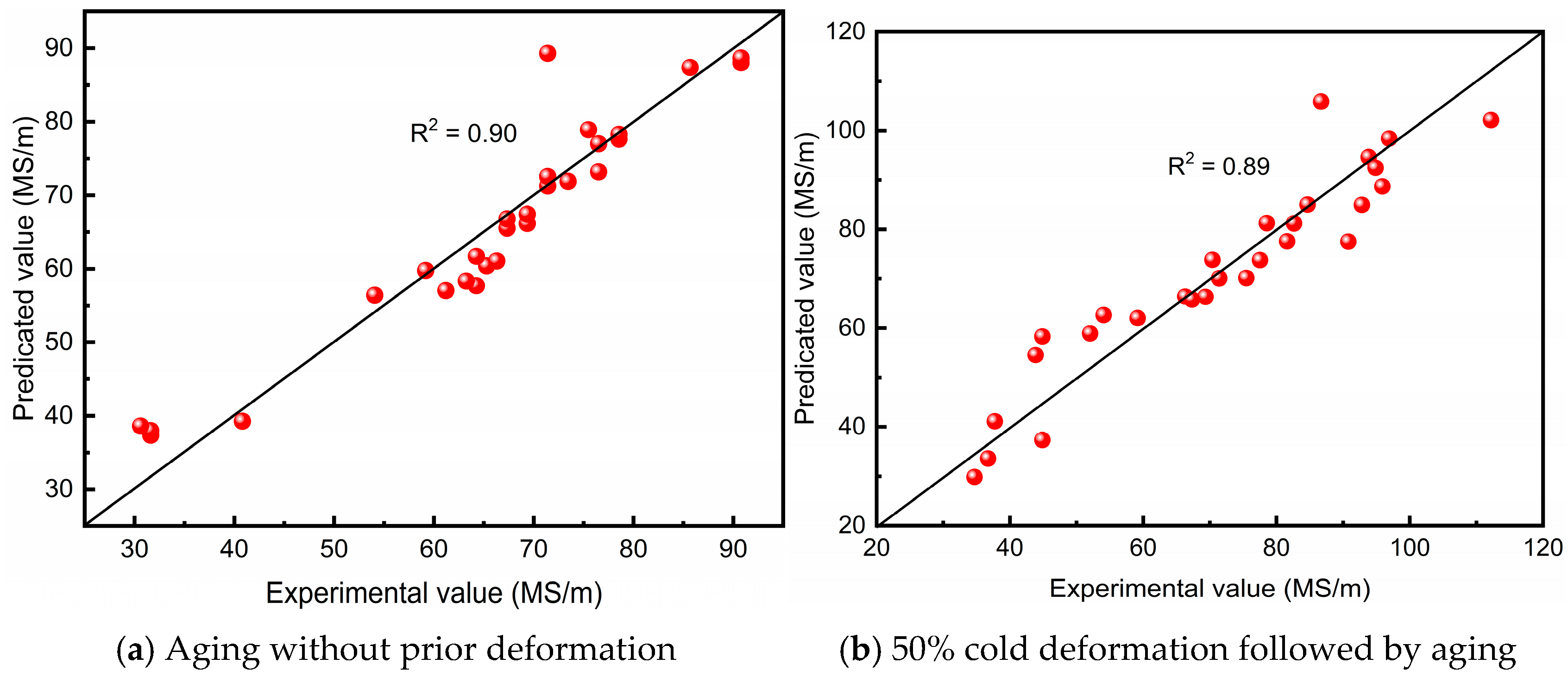

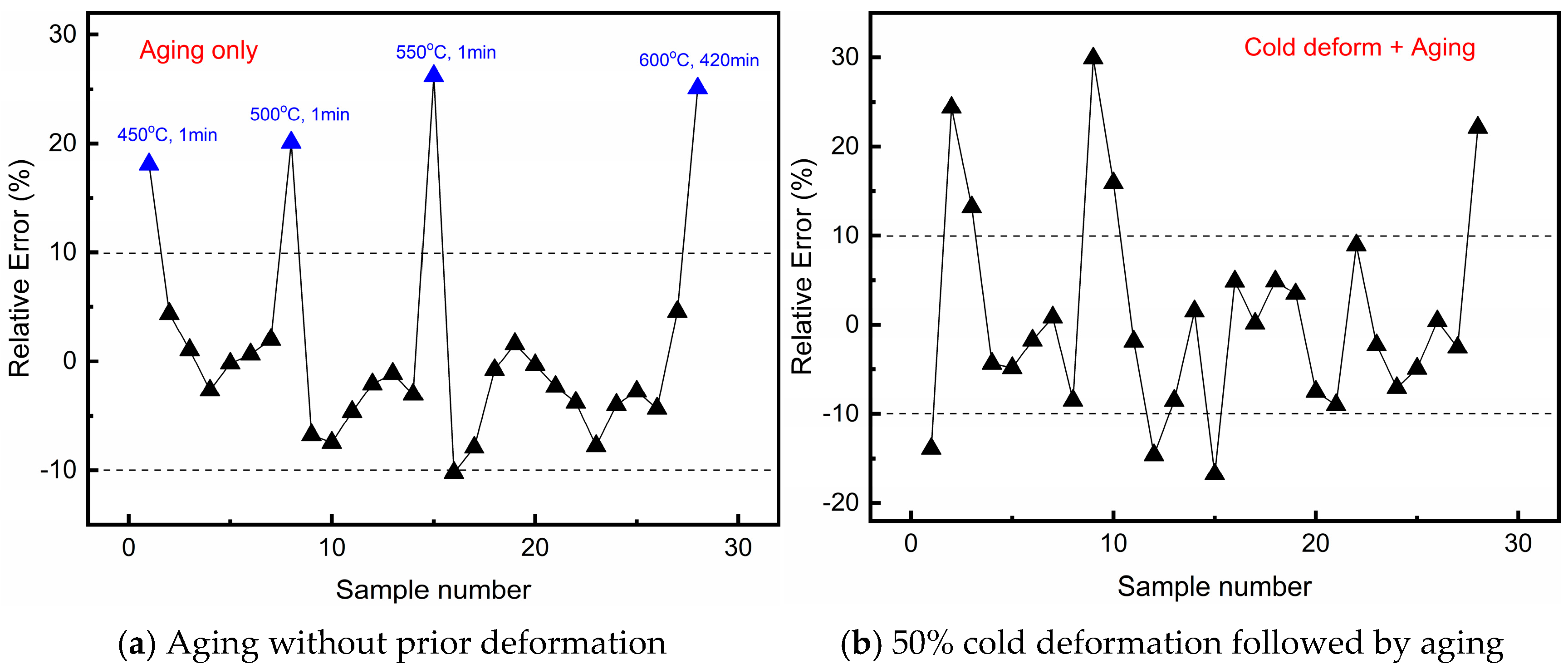

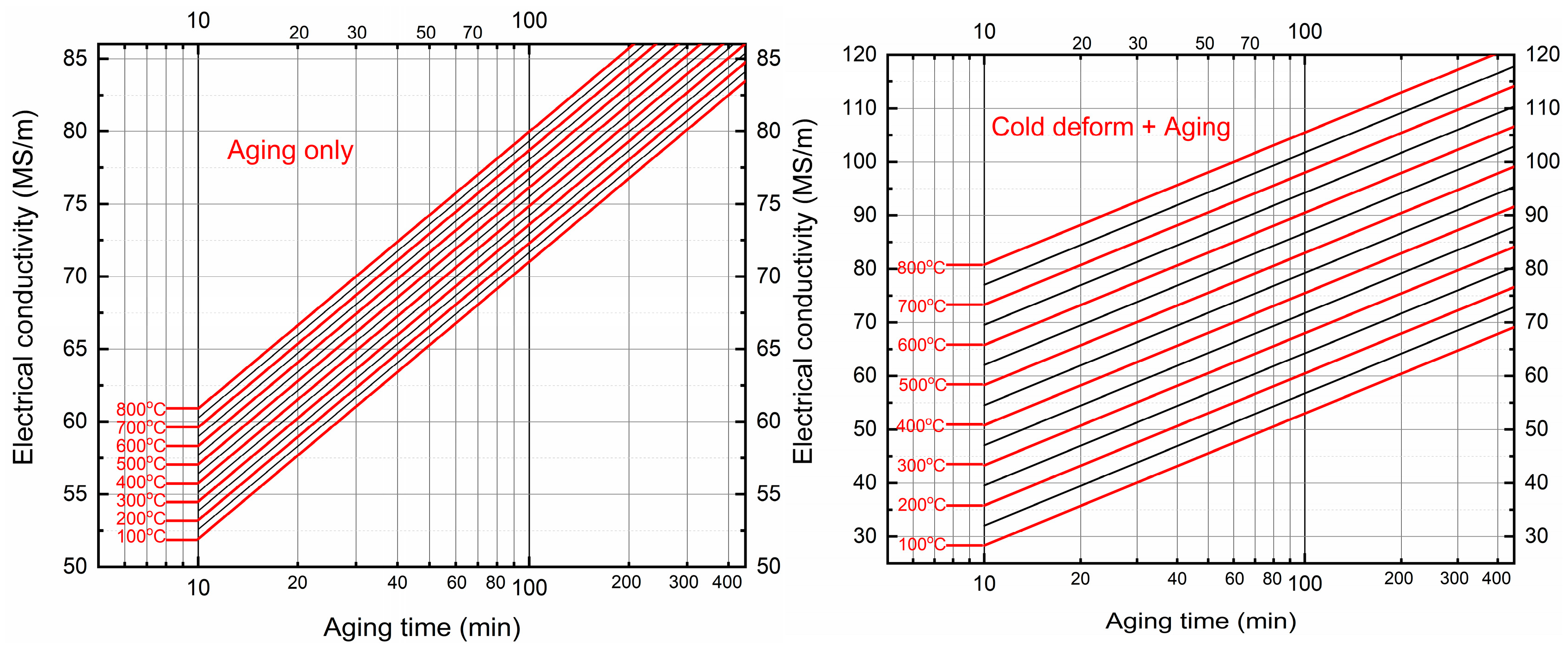

4. Establishment of the Predictive Model for Electrical Conductivity During Aging of Cu–4Ti Alloy

5. Physical Basis for the Linear–Logarithmic Temperature–Time Dependencies

5.1. Diffusion-Controlled Precipitation and the Linear Temperature Dependence

5.2. Logarithmic Dependence on Aging Time

5.3. Influence of Cold Deformation: Dislocation Density and Accelerated Diffusion Paths

6. Kinetic Curve Construction for the Aging Process of Cu–4Ti Alloy

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L.; Lu, F.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Ruan, Y. Reverse design of copper alloy composition based on ensemble learning and genetic algorithm. J. Mater. Res. 2025, 40, 2834–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xu, P.; Wang, J.; Hong, Z.; Wang, W.; Dai, F. Overcoming the trade-off between conductivity and strength in copper alloys through undercooling. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsse, S.; Gouné, M.; Lin, W.C.; Girard, L. Dataset of mechanical properties and electrical conductivity of copper-based alloys. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, N.; Sinha, S.K.; Munir, B.; Srishilan, C.; Srivastava, C.; Sarkar, S. Designing scheme of compositionally tuned high-strength and high-conductive copper alloy: A systematic phase transformation study. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 1264–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Zhang, C.M.; Ma, Y.X.; Jia, S.; Song, K.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, X.; Xiao, Z.; Guo, H. Enhanced strength of a high-conductivity Cu-Cr alloy by Sc addition. Rare Met. 2024, 43, 6054–6067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Niu, R.; Bayat, M.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, Y.; Tan, Q.; Liu, S.; Hattel, J.H.; Li, M.; et al. Manufacturing of high strength and high conductivity copper with laser powder bed fusion. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lv, D.; Liu, J.; Guo, C.; Guo, S.; Zhang, J. A Cu-Ni-Ti Alloy with Excellent Softening Resistance Combined with Considerable Hardness and Electrical Conductivity Obtained by the Traditional Aging Process. JOM 2024, 76, 4327–4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Xie, G.; Liu, F.; Xue, W.; Wang, R.; Liu, X. Optimizing the overall performance of Cu-Ni-Si alloy via controlling nanometer-lamellar discontinuous precipitation structure. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2025, 32, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; He, Z.; Xiao, P. Synergistic Strengthening of Cu-Cr-Zr-Mg Alloy by Multi-step Deformation-Aging Process. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, W.Y.; Huang, G.J.; Tseng, C.W.; Chiu, K.C.; Yang, S.; Chen, J.K. Heat Treatment-Induced Pore Migration and Conductivity Evolution in Additively Manufactured Copper. J. Mater. Eng. Perform 2025, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Wang, M.; Guo, M.; Wang, H.; Mo, Y.; Liu, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Lou, H. Improved hot workability of Cu-3.18wt%Ti alloy via cooperative control of dynamic recrystallization and precipitation. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 6307–6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczny, J.; Labisz, K.; Ürgün, S.; Yiğit, H.; Fidan, S.; Bora, M.Ö.; Atapek, Ş.H.; Ćwiek, J. Modelling of Hardness and Electrical Conductivity of Cu–4Ti (wt.%) Alloy and Estimation of Aging Parameters Using Metaheuristic Algorithms. Materials 2025, 18, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markandeya, R.; Nagarjuna, S.; Sarma, D.S. Effect of prior cold work on age hardening of Cu–4Ti–1Cr alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 404, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Qi, J.; Wang, X.; Jie, J.; Guo, R. A Novel Microstructure of Cu-Ti Alloy with Ultrahigh Electrical Conductivity and Strength. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 2017–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhu, S.; Gao, H.; Tang, J.; La, P.; Zhan, F.; Zhu, M. Microstructure and Properties of Cu–Ti Alloys Prepared by Aluminothermic Reaction and Subsequent Rolling. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2023, 124, 1555–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhou, M.; Tian, B.; Zou, J.; Jing, K.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, Q.; Tian, C.; Li, X.; et al. Effects of Trace La on the Aging Properties of the Cu-Ti-Zr Alloys. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 4054–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyal Ukabhai, K.; Curle, U.A.; Masia, N.D.E.; Smit, M.; Mwamba, I.A.; Norgren, S.; Öhman-Mägi, C.; Hashe, N.G.; Cornish, L.A. Formation of Ti2Cu in Ti-Cu Alloys. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 2022, 43, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.Z.; Lee, J.; Lim, S.H.; Ahn, J.H.; Kim, K.; Kim, S. Optimization of conductivity and strength in Cu-Ni-Si alloys by suppressing discontinuous precipitation. Met. Mater. Int. 2016, 22, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semboshi, S.; Amano, S.; Fu, J.; Iwase, A.; Takasugi, T. Kinetics and Equilibrium of Age-Induced Precipitation in Cu-4 At. Pct Ti Binary Alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2017, 48, 1501–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z. Suppression of discontinuous precipitation by Fe addition in Cu–Ti alloys. Rare Met. 2025, 44, 1982–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Dai, X.; Han, P.; Zhou, C.; Wei, Y.; Hou, L. Age hardening studies of a Cu–4Ti–Cr–Fe alloy. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 1848–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; You, H.; Du, H.; Wang, Q.; Hou, L.; Kobayashi, E.; Samberger, S.; Wei, Y. Precipitation behavior and properties change of Cu-3Ti-0.5Mg-0.5Sn alloy during two-stage cold rolling and aging treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1031, 181089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, H.; Song, K.; Zhou, Y.; Cheng, C.; Guo, H.; Guo, Y.; Tian, J. Aging process and strengthening mechanism of Cu–Cr–Ni alloy with superior stress relaxation resistance. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 3579–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, A.; Sun, L.; Deng, Y.; Yuan, M. Study of the Precipitation Kinetics, Microstructures, and Mechanical Properties of Al-Zn-Mg-xCu Alloys. Metals 2022, 12, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, M.; Gan, C.; Zhang, Z.; Aliaksandr, V.; Victor, Z.; Zou, Z. Effects of aging processes on the microstructure, texture, properties and precipitation kinetics of the Cu–Cr–Zr–Nb alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zu, G.; Li, M.; Han, Y.; Zhu, W.; Wu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Ran, X. Comparative Investigation on Microstructure, Texture, and Properties of Copper-Bearing and Copper-Free Non-oriented Electrical Steels. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2025, 56, 3650–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshaghi, A.; Pouransari, Z. Optimizing Arrhenius parameters for multi-step reactions via metaheuristic algorithms. J. Math. Chem. 2025, 63, 1065–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; Song, R.; Sun, J. High-temperature compression behavior prediction of medium Mn steel: A comparative study of Arrhenius constitutive equation, machine learning, and symbolic regression models. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 4788–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Z. Prediction flow behavior of Mg-12Gd-3Y-0.6Zr alloy during hot deformation based on Arrhenius and BP-ANN models: A comparative study. Appl. Phys. A 2024, 130, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Wang, Q. Development of Predictive Models for Tempering Behavior in Low-Carbon Bainitic Steel Using Integrated Tempering Parameters. Metals 2024, 14, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas Vicente, F.; Carcel Carrasco, J.; Fernández Antoni, R.; Ferrero Taberner, J.C.; Pascual Guillamón, M. Hardness Prediction in Quenched and Tempered Nodular Cast Iron Using the Hollomon-Jaffe Parameter. Metals 2021, 11, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, S.; Wei, Y. A Gauss–Newton method for mixed least squares-total least squares problems. Calcolo 2024, 61, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Song, C. STP Method for Solving the Least Squares Special Solutions of Quaternion Matrix Equations. Adv. Appl. Clifford Algebras 2025, 35, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Peng, L.J.; Li, J.; Mi, X.; Zhao, G.; Huang, G.; Xie, H.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Z. Properties and microstructure of copper–titanium alloys with magnesium additions. Rare Met. 2024, 43, 2290–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarpour, M.R.; Mirabad, H.M.; Hemmati, A.; Kim, H.S. Processing and microstructure of Ti-Cu binary alloys: A comprehensive review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 127, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Fan, Y.; Li, H.; Li, W.; Zhang, W.; Yucel, O.; Wang, C. In Situ Observation and Growth Kinetics of Primary and Eutectic Structures in a Hypereutectic Cu–Ti Alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2024, 55, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Hirata, V.M.; Hernandez-Santiago, F.; Saucedo-Muñoz, M.L.; Avila-Davila, E.O.; Villegas-Cardenas, J.D. Analysis of β’ (Cu4Ti) Precipitation During Isothermal Aging of a Cu–4 wt%Ti Alloy. In Characterization of Minerals, Metals, and Materials 2020; Li, J., Zhang, M., Li, B., Monteiro, S.N., Ikhmayies, S., Kalay, Y.E., Hwang, J.-Y., Escobedo-Diaz, J.P., Carpenter, J.S., Andrew, D., et al., Eds.; The Minerals, Metals & Materials Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ti | Zn | P | Pb | Mn | Ni | Cu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.95 | 0.13 | 0.065 | 0.003 | 0.03 | 0.01 | Bal. |

| 28.00 | −9.25 | 0.04 | 1846.20 | 20.10 | 0.01 | −284.91 | 0.00 | 2.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, G.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, W.; Wang, Q. Aging Kinetics and Activation Energy-Based Modeling of Electrical Conductivity Evolution in a Cu–4Ti Alloy. Metals 2026, 16, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010061

Sun G, Liu H, Zhang Y, Wu W, Wang Q. Aging Kinetics and Activation Energy-Based Modeling of Electrical Conductivity Evolution in a Cu–4Ti Alloy. Metals. 2026; 16(1):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010061

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Guojin, Hong Liu, Yingtang Zhang, Wenbin Wu, and Qi Wang. 2026. "Aging Kinetics and Activation Energy-Based Modeling of Electrical Conductivity Evolution in a Cu–4Ti Alloy" Metals 16, no. 1: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010061

APA StyleSun, G., Liu, H., Zhang, Y., Wu, W., & Wang, Q. (2026). Aging Kinetics and Activation Energy-Based Modeling of Electrical Conductivity Evolution in a Cu–4Ti Alloy. Metals, 16(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010061