Abstract

In this study, dried biomass of the alga Chlorella vulgaris was ground into a powder as an eco-friendly, low-cost inhibitor to mitigate the corrosion of carbon steel in acidic solutions. Electrochemical and weight loss measurements, surface morphology observations, adsorption isotherms, activation energy, and potential of zero charge calculations were applied to evaluate the inhibition performance. Electrochemical results indicate that C. vulgaris powder can simultaneously inhibit both the anodic and cathodic corrosion processes of carbon steel, demonstrating good inhibition performance and classifying it as a mixed-type inhibitor with both anodic and cathodic characteristics. Weight loss data further confirm that at a concentration of 300 mg/L, the corrosion inhibition efficiency reaches 88%. The fitted adsorption isotherm reveals that the adsorption of Chlorella vulgaris powder on the carbon steel surface follows the Langmuir model. Density functional theory (DFT) and molecular dynamics simulations indicate that the excellent inhibition performance is attributed to the combined effects of physisorption and chemisorption of constituents such as amino acids and cellulose present in C. vulgaris.

1. Introduction

Hydrochloric acid (HCl) is extensively used in industrial processes such as descaling, pickling, and acid cleaning of carbon steels [1,2,3,4]. However, severe metal dissolution often occurs during these operations, leading to substantial material degradation and process inefficiency. Acid corrosion also poses a significant challenge in mineral leaching systems, where HCl acts as a lixiviant in reactor environments [5,6]. The addition of corrosion inhibitors is therefore a widely adopted strategy to mitigate these detrimental effects [7,8,9,10].

Traditional organic inhibitors including imidazole, benzimidazole, quinoline, furan, and pyrimidine derivatives have demonstrated high inhibition efficiencies due to their ability to form protective films via π–electron interactions and heteroatom coordination with the metal surface [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Nonetheless, their toxicity, non-biodegradability, and high production costs restrict their large-scale application, prompting a global shift toward green and sustainable alternatives [17,18,19].

In recent decades, research has increasingly focused on naturally derived corrosion inhibitors extracted from renewable biomass sources such as plant seeds, leaves, barks, and nutshells [20,21,22]. These extracts are rich in nitrogen-, oxygen-, and sulfur-containing compounds, including alkaloids, polyphenols, terpenoids, flavonoids, and polysaccharides [23,24]. The heteroatoms in these biomolecules act as adsorption centers, facilitating chemisorption on metal surfaces and forming barrier films that hinder corrosion. However, the extraction of plant-based inhibitors often requires multiple organic solvents and complex procedures, which may compromise their environmental advantages [25,26].

Microalgae have recently emerged as promising feedstocks for eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors due to their high photosynthetic efficiency, rapid growth, and diverse biochemical composition. Among them, C. vulgaris, a unicellular green alga with spherical cells of 2–10 μm in diameter, is widely distributed in freshwater ecosystems [27]. Although eutrophication-induced algal blooms of C. vulgaris can cause ecological issues such as biofouling and water quality deterioration [28], this microalga also represents an abundant and low-cost biomass resource. It has found broad applications in biofuel production, wastewater remediation, animal feed, and pharmaceuticals owing to its rich content of proteins, amino acids, lipids, carbohydrates, pigments, and minerals [29,30,31,32,33].

From a corrosion inhibition perspective, the biomolecular constituents of C. vulgaris are particularly attractive. Proteins and amino acids provide nitrogen and oxygen functional groups capable of coordinating with iron atoms, while lipids and pigments enhance hydrophobic film formation, reducing active corrosion sites. Compared to terrestrial plant extracts, C. vulgaris offers advantages in renewability, compositional diversity, and ease of cultivation under controlled conditions. Despite these advantages, systematic studies on its application as a corrosion inhibitor in acid media remain scarce. Therefore, the present work investigates the inhibition behavior and mechanism of C. vulgaris extract on carbon steel corrosion in 1 M HCl solution using electrochemical, gravimetric, and surface analytical techniques, including Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy. The results aim to elucidate the adsorption characteristics and film-forming properties of algal biomolecules, contributing to the rational design of green corrosion inhibitors.

2. Experimental

2.1. Preparation of C. vulgaris Powder

C. vulgaris was cultured in a culture medium containing (g/L) 0.2 MgSO4, 0.24 K2HPO4, 0.0153 KH2PO4, 0.0116 CaCl2∙2H2O, 0.5 carbamide, and 0.0005 trace nutrients in distilled water. Cells multiplied quickly after 5 days of incubation in the lab with indirect natural sunlight [34,35]. The harvested C. vulgaris broth was centrifuged at 2795× g for 5 min. After that, the recovered pellet was rinsed thrice using distilled water. The collected C. vulgaris pellet was dehydrated in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h. After that, it was ground to a fine powder using an agate mortar. Finally, the functional groups of the main components in the C. vulgaris powder were identified using an IR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Nicolet iS20, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.2. Metal Specimen Preparation

A commercially available ordinary carbon steel was tested. Its composition was (wt%) 0.35 Mn, 0.17 C, 0.17 Si, 0.035 S, 0.035 P, 0.30 Ni, 0.25 Cr, 0.25 Cu, and balanced Fe. A specimen of this metal buried in epoxy resin (exposed disk surface area of 0.785 cm2) was employed for electrochemical corrosion testing. Additional specimens (5 cm × 1 cm × 0.3 cm) were used for measuring weight loss. Only the top 5 cm × 1 cm surface was exposed. Disk-shaped specimens (thickness 0.3 cm, radius 0.5 cm,) were used for surface observations. All the specimens above were abraded up to 1200 grit. After that, the specimens were cleaned using anhydrous acetone and ethyl alcohol.

2.3. SEM Observation and Weight Loss

For surface observations and weight loss measurements, specimens were retrieved from a 1 M HCl solution after a 3 h corrosion test in the presence of different concentrations (the C. vulgaris powder was directly dissolved into the corresponding volume of 1 M HCl to achieve the target concentration) of C. vulgaris as a corrosion inhibitor at 303 K. The specimens were cleaned using deionized water and anhydrous ethyl alcohol before drying with N2 gas [36]. After that, the specimens were viewed under a FESEM (field-emission scanning electron microscope) (Model Sirion 200, FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) and weighed using an electronic balance (readability: 0.1 mg). The weight loss-based corrosion rate (CR) and corrosion inhibition efficiency (η) were calculated according to the following formulas, respectively [1,37,38]:

In Equation (1), Δm is the weight difference before and after corrosion, ρ is the density of carbon steel, S is the exposed surface area, and t is the corrosion duration. In Equation (2), subscript 0 indicates uninhibited corrosion.

2.4. Electrochemical Corrosion Testing

The electrochemical tests were conducted using an electrochemical workstation (Princeton Applied Research, Oak Ridge, TN, USA) with a classical three-electrode glass cell, employing a platinum sheet as the counter electrode. Before electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) scans, there was a 0.5 h time period to monitor the open circuit potential (OCP) to ensure that the working electrode (carbon steel specimen) was at a steady state. Then, EIS was scanned with a sinusoidal voltage (10 mV amplitude, 105–10−2 Hz scan range). The potentiodynamic polarization voltage scan range was −200 to 200 mV vs. OCP [1,39]. To obtain the potentials of zero charge, EIS was applied at different potentials [40].

2.5. Quantum Chemical Calculations

The main constituents of C. vulgaris are proteins (amino acids) and cellulose, among which glutamic acid and aspartic acid are the most abundant amino acids. From a molecular perspective, glutamic acid (SEAEA), aspartic acid (LAC), and cellulose (MICC) exhibit favorable corrosion inhibition potential, which may account for the inhibitory effect of C. vulgaris on carbon steel in HCl solution. Therefore, the molecular structures of these three compounds were optimized, and their adsorption activities were evaluated using the Gaussian 09 program. Theoretical calculations were performed using density functional theory (DFT) with the hybrid B3LYP functional. The TZV(P) basis set was used for oxygen and nitrogen atoms, while the SV(P) basis set was applied for carbon and hydrogen atoms [41].

2.6. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

To further clarify the potential corrosion inhibition mechanism of Chlorella vulgaris, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted using the Forcite module in Materials Studio 8.0 to investigate the adsorption behavior of SEAEA, LAC, and MICC molecules on the carbon steel surface under vacuum and in 1 M HCl solution. The COMPASS high-accuracy force field and an NVT ensemble were employed, with a total simulation time of 200 ps, a temperature of 303 K, and a time step of 0.5 fs. The model dimensions for the inhibitor–Fe(110) system under vacuum were 32.27 Å × 32.27 Å × 16.50 Å, whereas those for the inhibitor–Fe(110) composite system in 1 M HCl were 32.27 Å × 32.27 Å × 58.33 Å [41].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. FT-IR Analysis of C. vulgaris Powder

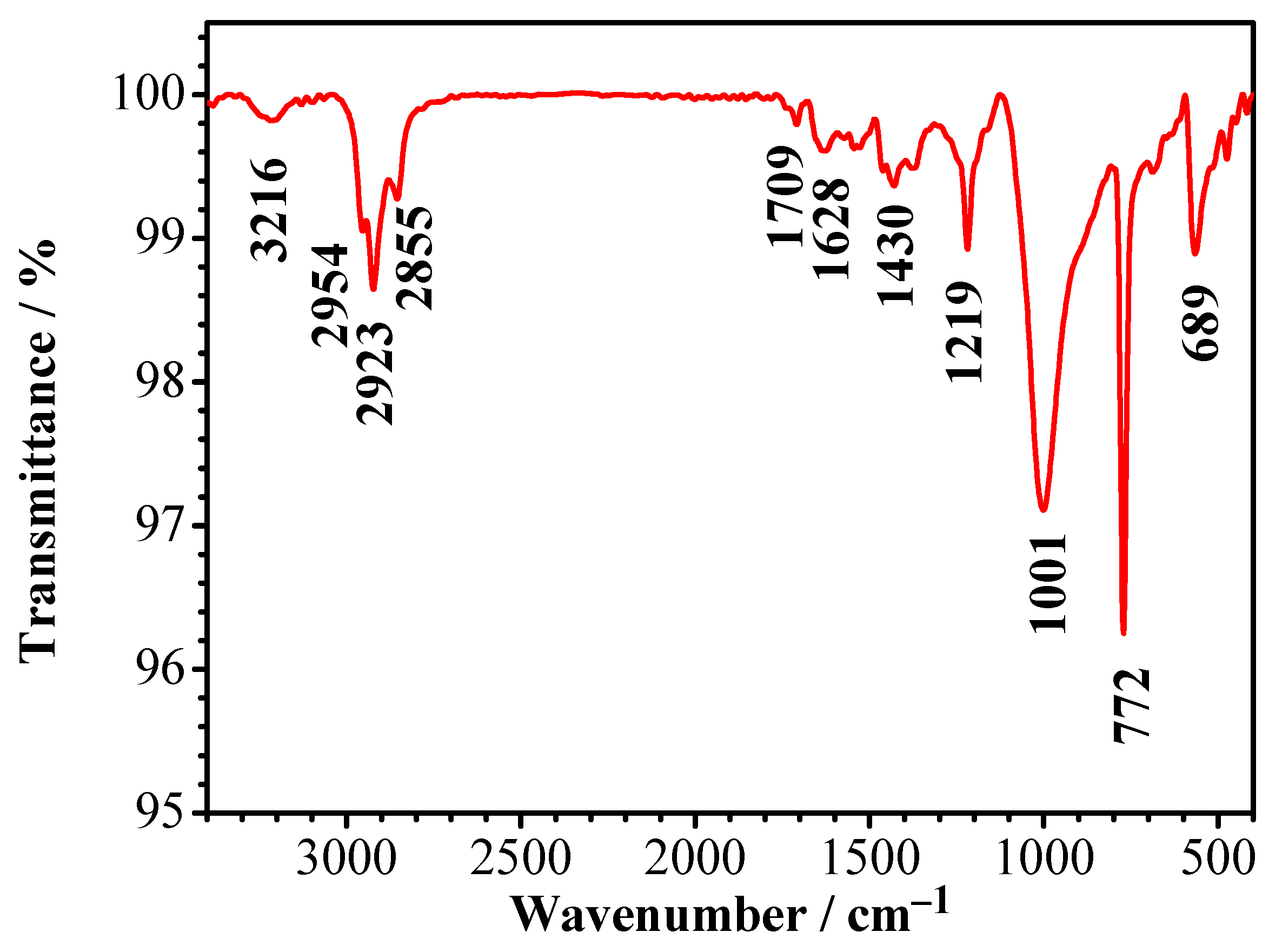

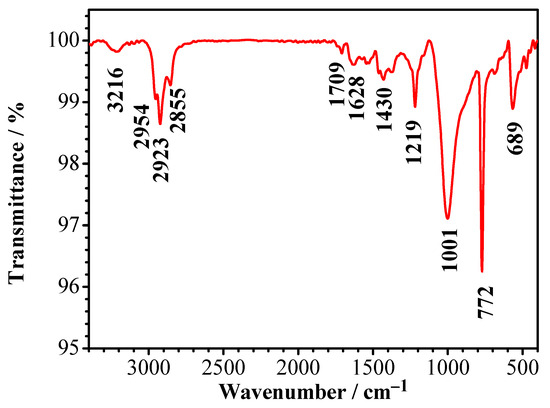

Figure 1 shows the FT-IR spectrum of the C. vulgaris powder. Bands at 689 cm−1, 772 cm−1, 1001 cm−1 and 1430 cm−1 are attributed to aromatic hydrocarbons, while bands at 1219 cm−1, 1545 cm−1 and 1709 cm−1 belong to amide groups [42,43,44,45]. The band at 1629 cm−1 indicates amino acids [46], and bands at 2855 cm−1, 2923 cm−1, and 2954 cm−1 are due to aliphatic hydrocarbon groups [47]. The band at 3216 cm−1 corresponds to a hydroxyl group [48]. The results of FT-IR analysis proved that the C. vulgaris powder was composed of complex chemical compounds containing heteroatoms (SEAEA, LAC, MICC, etc.).

Figure 1.

FT-IR spectrum of C. vulgaris powder.

3.2. Weight Loss

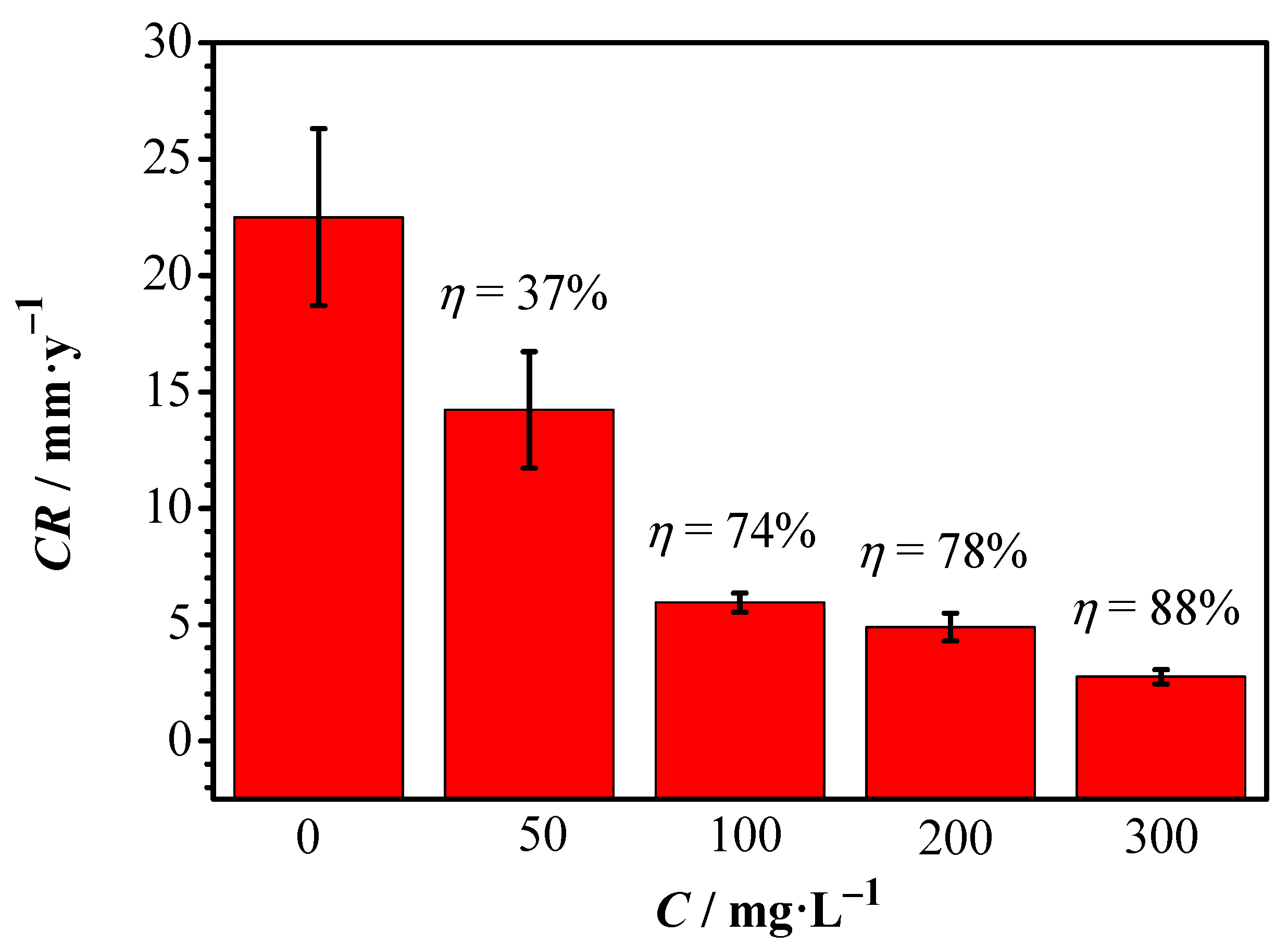

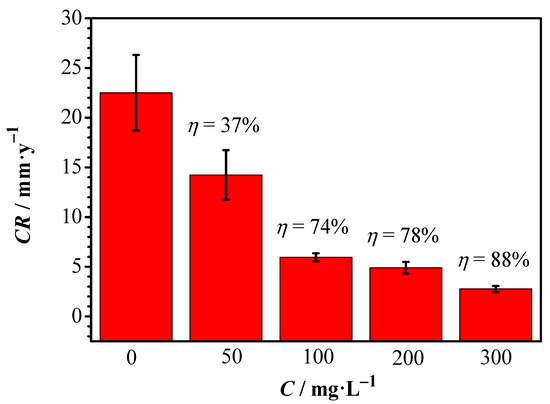

The weight loss test is the most classical and accurate method for evaluating the corrosion inhibition behavior of inhibitors. The CR plot based on the weight loss data is presented in Figure 2. It shows that the most severe corrosion by the 1 M HCl solution occurred without the inhibitor (22.5 mm/y). The presence of C. vulgaris inhibited corrosion. The inhibition efficiency at a low dosage of 50 mg/L was 37%, and it increased with increasing C. vulgaris concentration. The inhibition efficiency was 74% at 100 mg/L inhibitor, 78% at 200 mg/L inhibitor, and 88% at 300 mg/L inhibitor concentrations, indicating a positive correlation between the corrosion inhibition effect of C. vulgaris on carbon steel in 1 M HCl and its concentration.

Figure 2.

Corrosion rates based on weight loss data of carbon steel after 3 h exposure in 1 M HCl solution with different concentrations of C. vulgaris at 303 K.

3.3. EIS

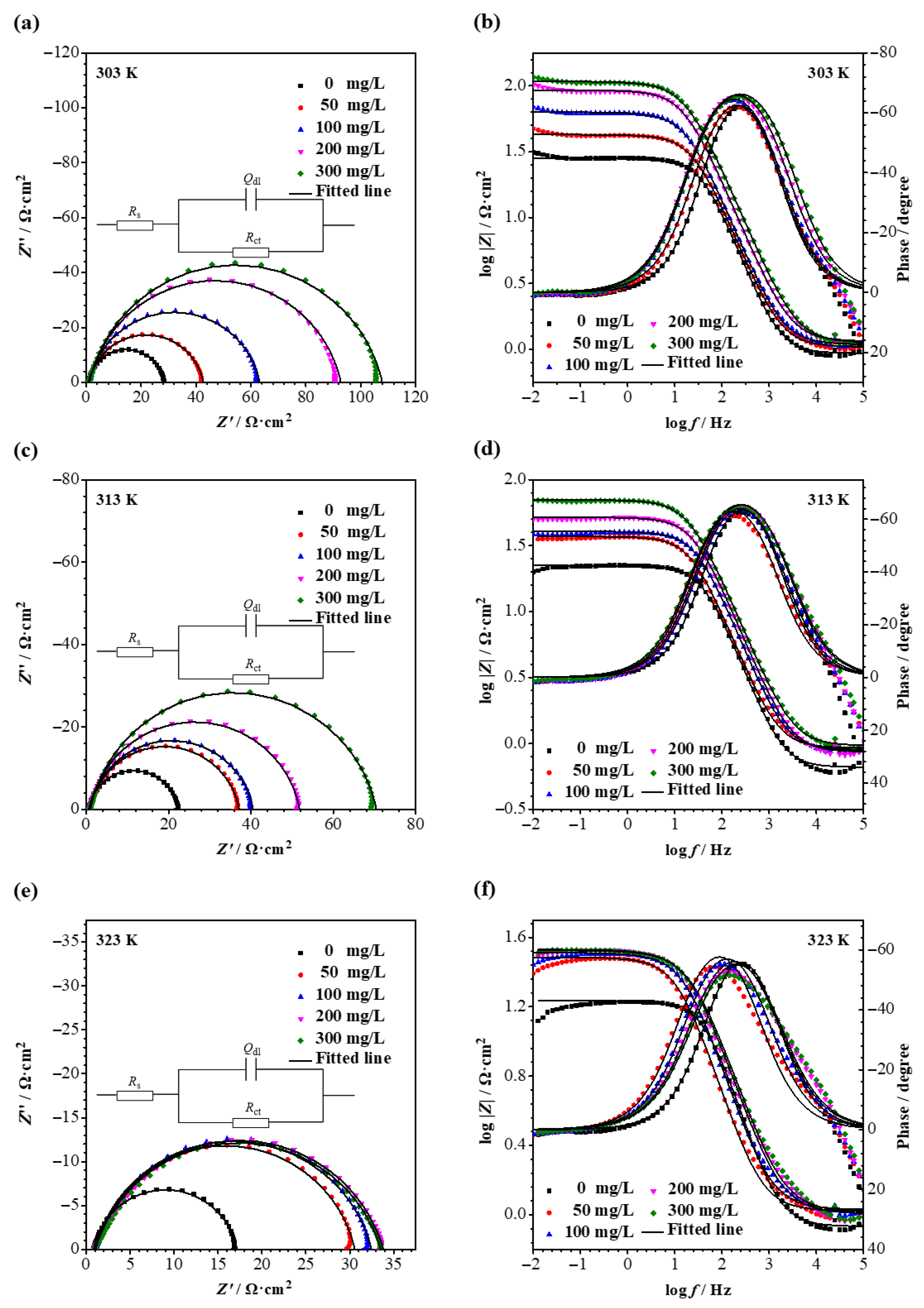

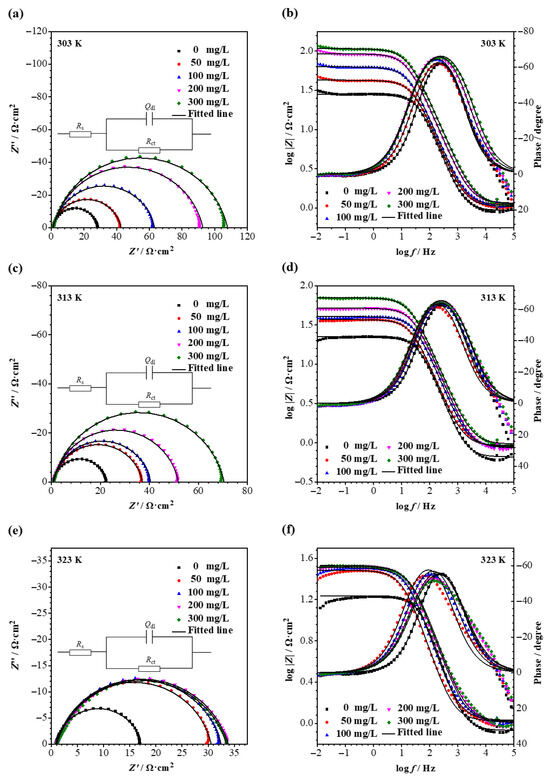

Electrochemical testing is another important method for evaluating the corrosion inhibition performance of inhibitors, in addition to the weight loss test. EIS plots for various conditions are presented in Figure 3, which shows that the semicircle diameters in the Nyquist plot (Figure 3a) are the smallest in the absence of C. vulgaris at 303 K, indicating the smallest corrosion resistance and the most serious corrosion when the inhibitor is absent. The diameter of the semicircle increased with the addition of the inhibitor. EIS data followed the same trend at 313 K and 323 K, except that the semicircle diameter apparently decreased with increasing temperature, indicating more severe corrosion at higher temperatures.

Figure 3.

Nyquist and Bode plots for carbon steel after 1 h exposure in 1 M HCl solution at different C. vulgaris concentrations and temperatures, and the equivalent electrical circuit used to fit EIS data is shown in the Nyquist plot. (a,b) are Nyquist and Bode plots at 303 K, respectively; (c,d) are Nyquist and Bode plots at 313 K, respectively; (e,f) are Nyquist and Bode plots at 323 K, respectively.

An equivalent circuit is shown in Nyquist plots in Figure 3. This one-time constant model fit the EIS spectra in Figure 3 well. Table 1 lists the fitted parameters of solution resistance (Rs), charge transfer resistance (Rct), and double-layer capacitance (Qdl). As shown in Table 1, Rct increased when the C. vulgaris concentration increased. The increasing Rct indicates that the C. vulgaris powder mitigated acid corrosion by slowing down charge transfer. The above EIS results are consistent with the conclusions drawn from the weight loss tests.

Table 1.

Fitted parameters from EIS data in Figure 3.

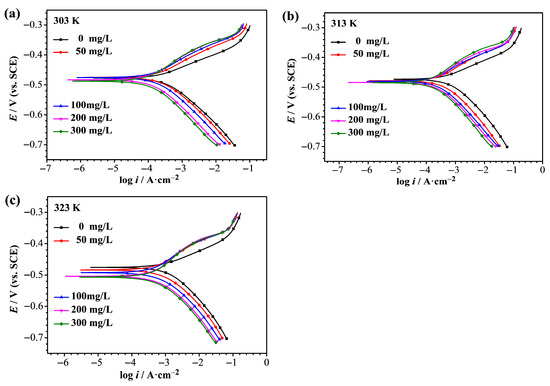

3.4. Potentiodynamic Polarization Analysis

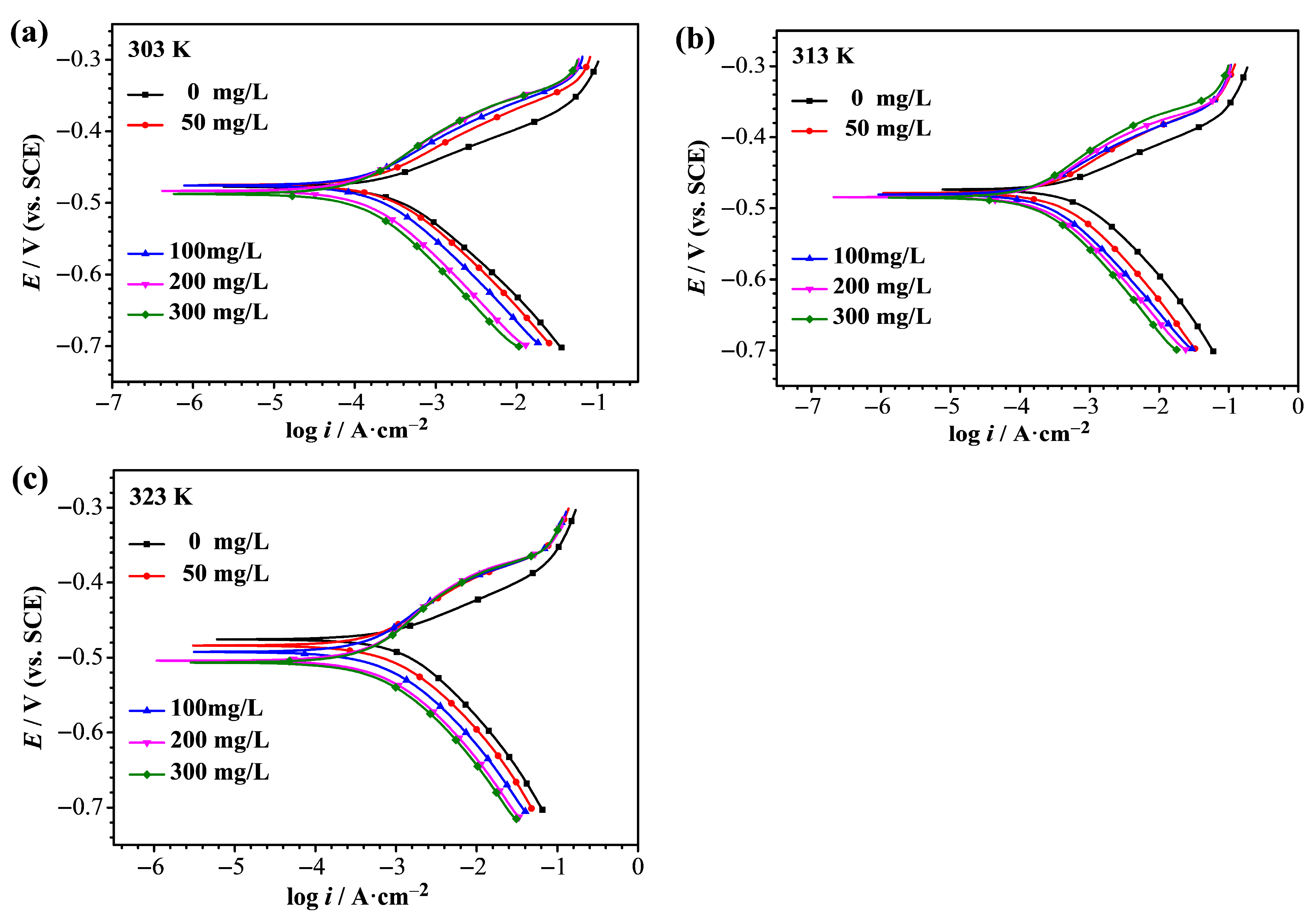

Figure 4 shows potentiodynamic polarization curves for acid corrosion at different inhibitor concentrations and temperatures. In Figure 4, both the anodic and cathodic curves shift to the left when the inhibitor is present. This indicates that C. vulgaris can simultaneously inhibit both the cathodic and anodic corrosion processes of carbon steel in 1 M HCl, functioning as a mixed-type inhibitor with both cathodic and anodic inhibition characteristics. Parameters from fitting potentiodynamic polarizations are listed in Table 2, which contains Tafel slopes (βa and βc for cathodic reactions and anodic reactions, respectively, corrosion potentials (Ecorr), and corrosion current density (icorr). With the addition of C. vulgaris to the 1 M HCl acid solution, icorr decreased sharply, and the corresponding icorr-based corrosion inhibition efficiency (ηi) data indicate good performance of C. vulgaris in the acid corrosion. With the addition of C. vulgaris, the Ecorr shifts negatively, but the change is less than 85 mV. This further confirms that Chlorella vulgaris can inhibit both the anodic dissolution of carbon steel and the cathodic hydrogen evolution in 1 M HCl. The efficiency data at 303 K are lower than those based on weight loss in Figure 2 because the latter were cumulative, whereas the former were only for the 15 min scan duration. The results of potentiodynamic polarizations are consistent with the EIS data, which demonstrate that C. vulgaris effectively mitigates the acid corrosion of carbon steel.

Figure 4.

(a–c) represent the potentiodynamic polarization curves of carbon steel after 1 h of exposure in 1 M HCl solution containing different concentrations of Chlorella vulgaris at different temperatures.

Table 2.

Fitted parameters from potentiodynamic polarization curves in Figure 4.

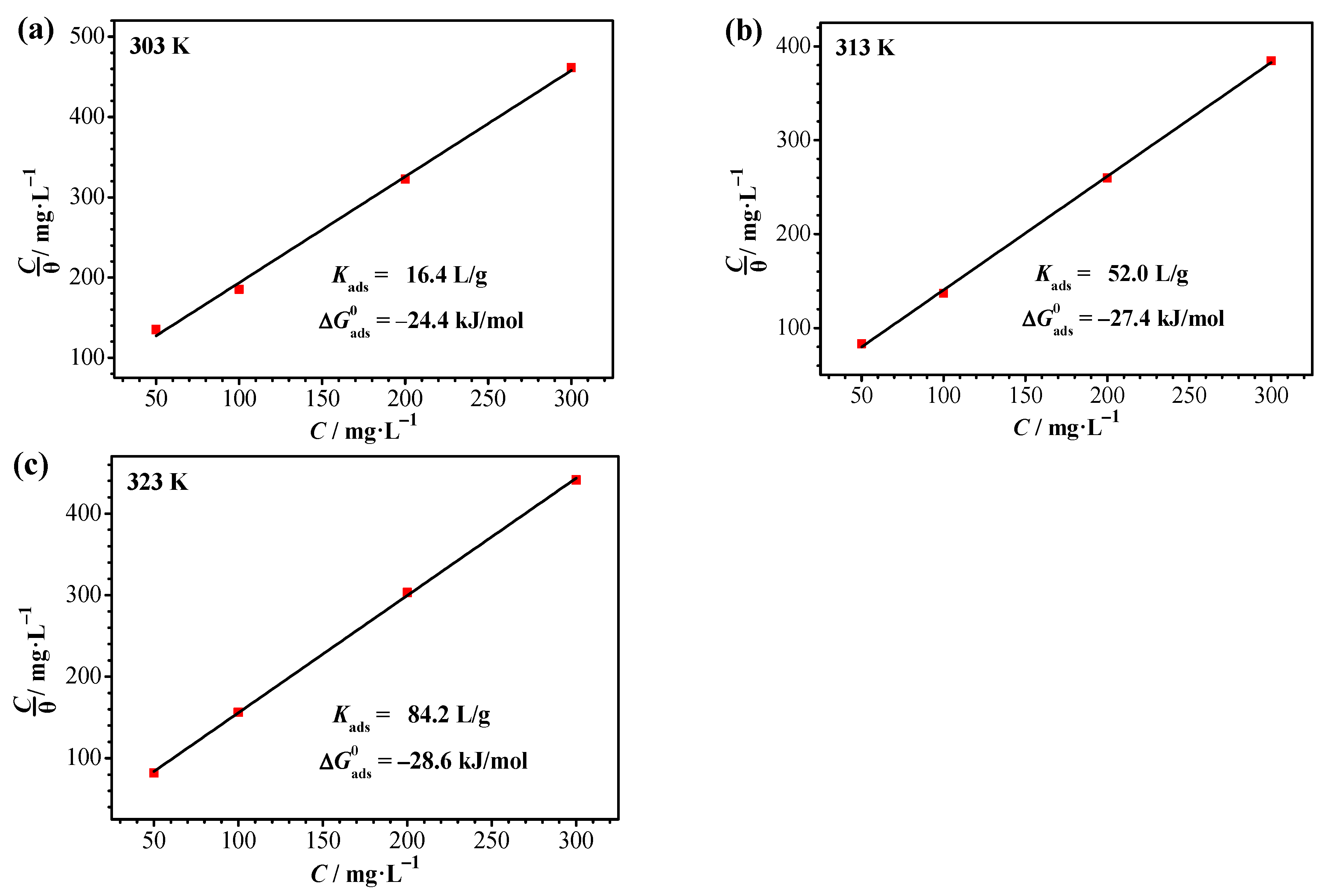

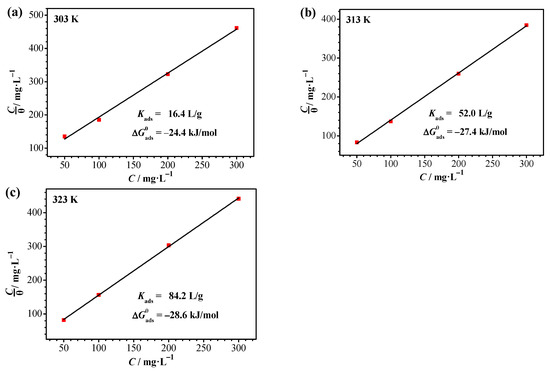

3.5. Inhibitor Adsorption Isotherm

Among several adsorption isotherms, the Langmuir adsorption isotherm was found to be the best fit for the results. This isotherm is expressed below:

where θ, Kads and C are the fraction of the metal surface covered by the inhibitor, adsorption equilibrium constant and the equilibrium inhibitor concentration, respectively. Equation (3) can be linearized to obtain a straight line of C/θ vs. C. θ was calculated by using ηi, assuming the corrosion inhibition efficiency came from a monolayer of the corrosion inhibitor molecules on the metal surface. θ at unity corresponded to 100% corrosion inhibition. Figure 5 shows a good linear correlation at all the tested temperatures.

Figure 5.

Langmuir adsorption isotherms of C. vulgaris on carbon steel in 1 M HCl solution at different temperatures: (a) 303 K, (b) 313 K, (c) 323 K.

Kads is related to the Gibbs free energy (ΔG0ads) according to the following relationship in the literature [36]:

where CH2O, R, and T are water density, universal gas constant, and corrosion temperature (absolute), respectively.

As shown in Figure 6, the ΔG0ads values at 303 K, 313 K, and 323 K were −24.4 kJ/mol, −27.4 kJ/mol and −28.6 kJ/mol, respectively. ΔG0ads > −20 kJ/mol corresponds to physisorption, which could be attributed to the electrostatic adsorption. ΔG0ads < −40 kJ/mol indicates chemisorption [18]. The ΔG0ads values in Figure 5 for different T are between −40 kJ/mol and −20 kJ/mol, suggesting that both physisorption and chemisorption happened.

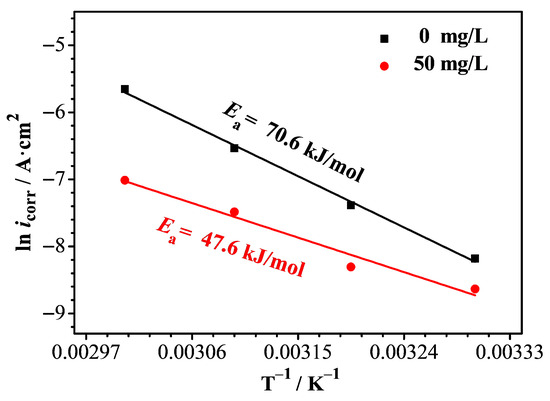

Figure 6.

Arrhenius plots of mild steel corrosion at the end of 1 h exposure in 1 M HCl solution with and without C. vulgaris.

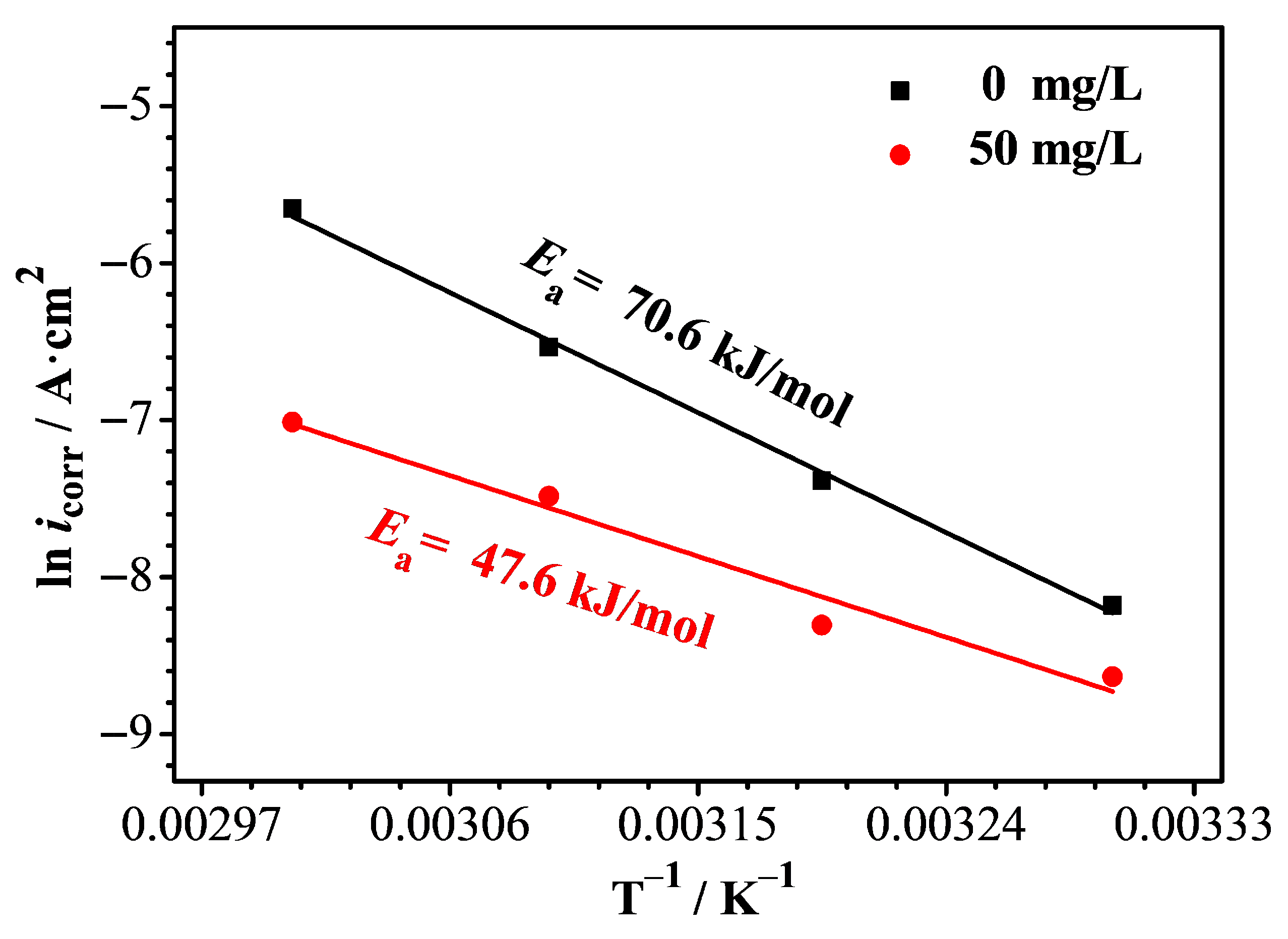

3.6. Activation Energy

To better understand the adsorption mechanism of C. vulgaris at different temperatures, the activation energy (Ea) for adsorption was calculated from icorr values obtained from potentiodynamic polarization with (50 mg/L inhibitor) and without the inhibitor based on the Arrhenius equation below [1,39]:

In which A is the pre-exponential factor. A and Ea were calculated from a linear regression of lnicorr vs. 1/T. The value of Ea is shown in Figure 6. The high Ea value of 70.6 kJ/mol corresponded to the absence of the inhibitor. With a 50 mg/L inhibitor, it decreased to 47.6 kJ/mol. This is common for corrosion inhibitors [1,49]. The value of lnA decreased from 19.8 (0 mg/L inhibitor) to 10.1 (50 mg/L inhibitor), and the significant decrease in A offset the unfavorable decrease in Ea, leading to a decreased icorr. This behavior suggests that inhibitor adsorption alters the metal–solution interface, reducing the number of active sites available for charge transfer and changing the nature of the rate-determining step. Therefore, although the apparent Ea decreases, the overall corrosion rate is still substantially reduced due to the dominant effect of the lowered A value. This phenomenon has been reported in several inhibitor systems where surface coverage and interfacial restructuring play a more critical role than the energy barrier alone [49].

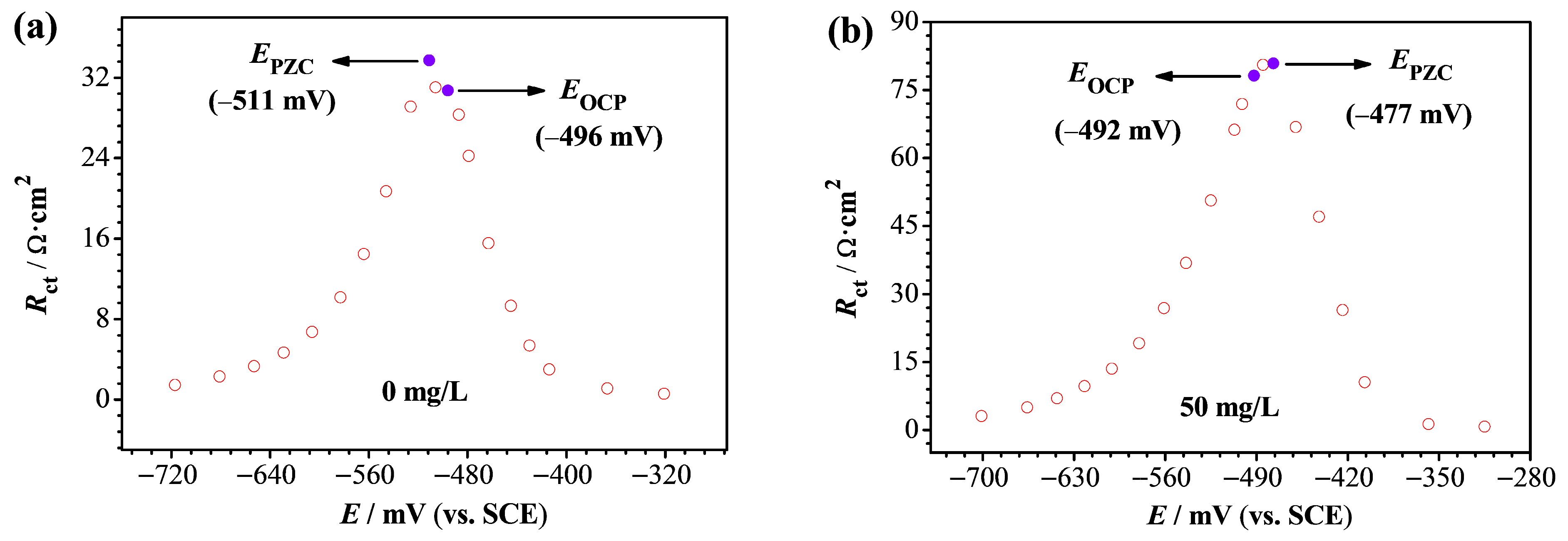

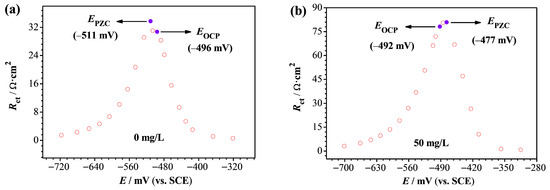

3.7. Potential of Zero Charge

The corrosion inhibition in this work was attributed to the adsorption of C. vulgaris molecules to the specimen surface, which shielded the carbon steel from direct exposure to HCl. Potential of zero charge (Epzc) and Eocp may affect the charge of a metal surface based on the following equation:

in which Er is the so-called Antropov’s rational corrosion potential [40]. Rct was obtained from EIS measurements by applying different potentials, and then Epzc was determined at the maximum Rct. The electric double layer was absent on the specimen’s surface at the electrode potential (Epzc).

In Figure 7, the value of Er in the absence of C. vulgaris is 15 mV. This positive value suggests that the carbon steel surface had a positive charge. In comparison, when there was 50 mg/L C. vulgaris in the acid solution, Er became negative (−15 mV). The negative value was attributed to the accumulation of cations at the beginning, and the negative surface state was beneficial to the adsorption of cations in the C. vulgaris powder.

Figure 7.

Rct vs. applied potential on carbon steel in 1 M HCl solution without (a) and with (b) C. vulgaris at 303 K measured after 1 h exposure.

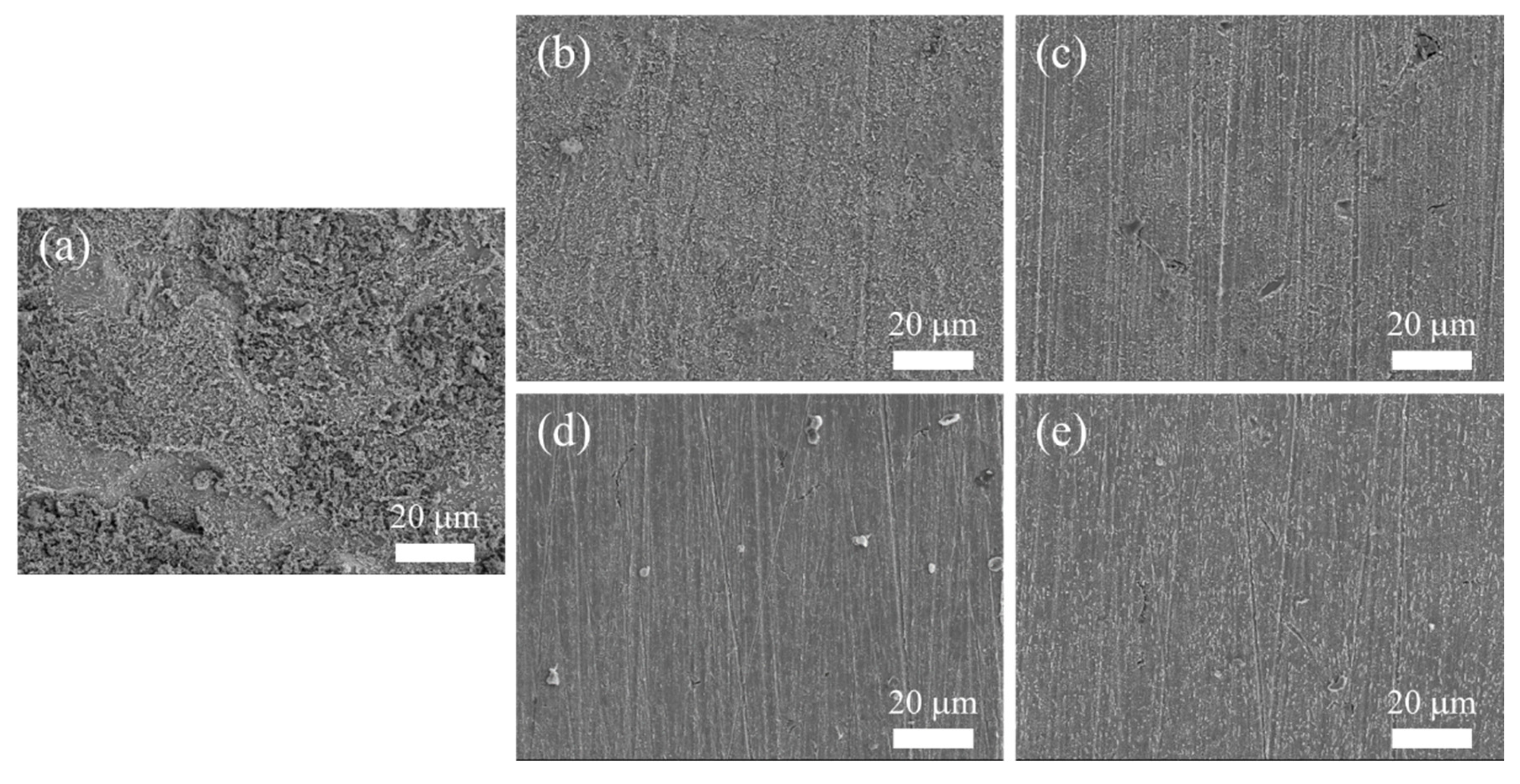

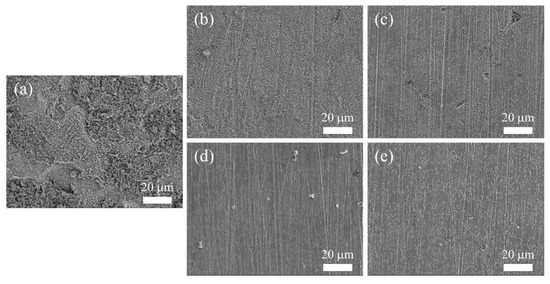

3.8. SEM Observation

Compared with electrochemical and weight loss tests, morphological analysis provides a more intuitive visualization of the influence of Chlorella vulgaris on the corrosion behavior of carbon steel in 1 M HCl. Surface morphologies of the carbon steel after acid corrosion with different C. vulgaris concentrations at 303 K are shown in Figure 8. On the corroded specimen without C. vulgaris, corrosion products are clearly visible in Figure 8. However, the specimen’s surface was much cleaner with polishing lines revealed when 50 mg/L C. vulgaris was present, indicating a good inhibition efficiency. This result is consistent with the findings from weight loss tests and electrochemical measurements.

Figure 8.

Surface morphologies of mild steel after 3 h exposure in 1 M HCl solution with different concentrations of C. vulgaris at 303 K: (a) 0 mg/L, (b) 50 mg/L, (c) 100 mg/L, (d) 200 mg/L and (e) 300 mg/L.

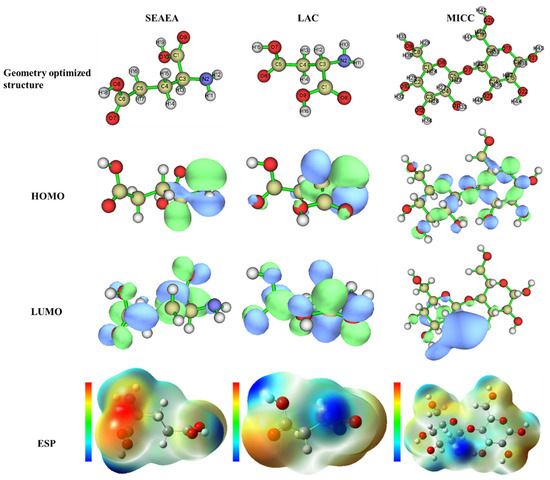

3.9. DFT

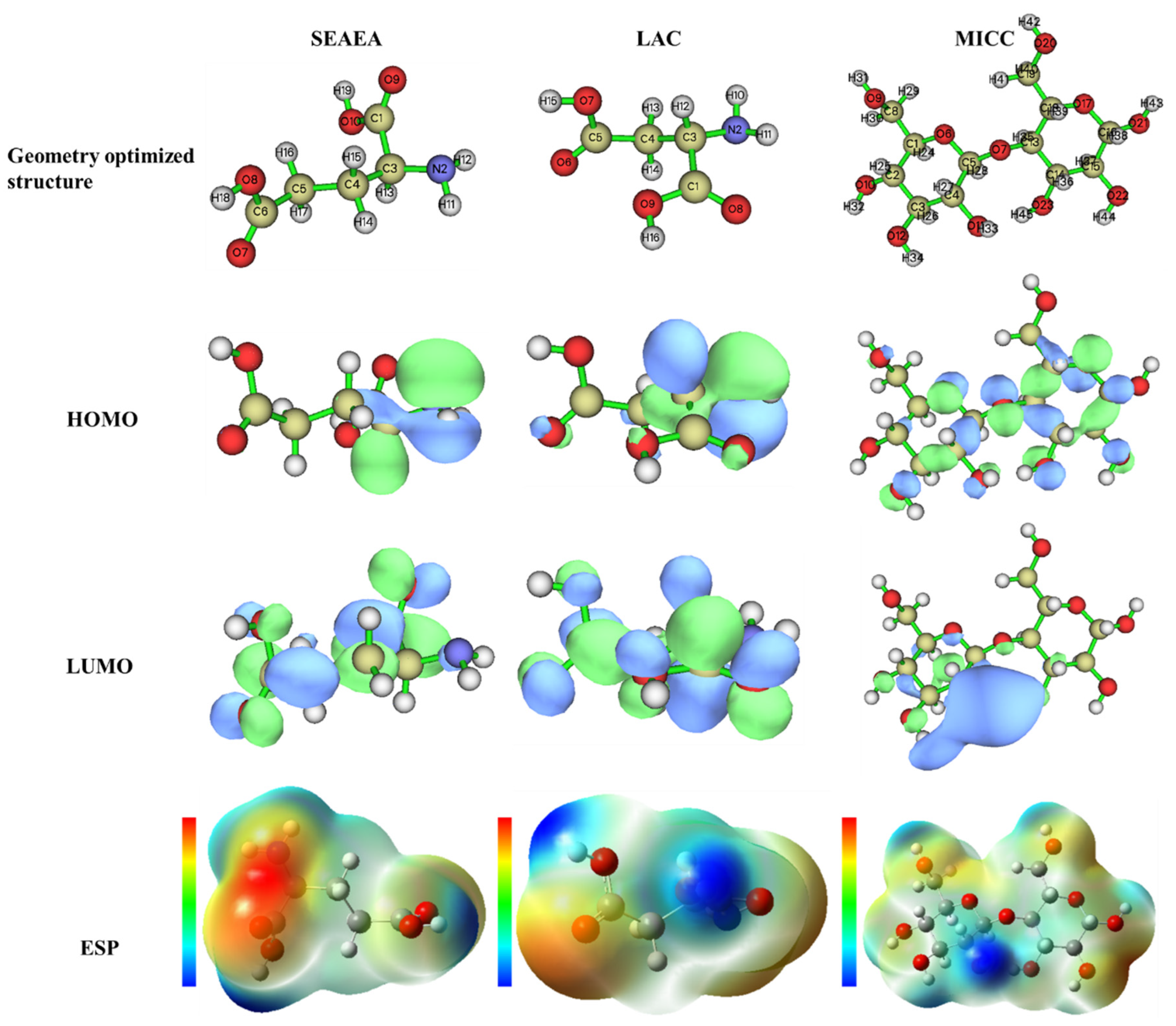

Figure 9 presents the spatially optimized geometries and electron cloud distributions within the molecular frameworks of SEAEA, LAC, and MICC obtained from DFT calculations. The calculated parameters, including the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital energy (ELUMO), the highest occupied molecular orbital energy (EHOMO), global softness (σ), fraction of electron transfer (ΔN), global hardness (γ), electronegativity (χ), and energy gap (ΔE), are summarized in Table 3. These parameters were determined according to Equations (7)–(11).

where I = −EHOMO and A = −ELUMO. For bulk iron, the work function φFe = 4.82 eV and χFe = 0.00 (adopting the theoretical values) [50,51].

Figure 9.

Structure optimization, HOMO, LOMO, and ESP plots of SEAEA, LAC and MICC.

Table 3.

Quantum chemical parameters of SEAEA, LAC and MICC.

The optimized structures indicate that all three molecules possess stable configurations and contain multiple polar functional groups (-COOH, -OH, -NH2), providing potential adsorption sites for electron donation or acceptance. Both SEAEA and LAC contain carboxyl and amino groups, which can coordinate with the metal surface through oxygen or nitrogen atoms. MICC, with its larger structure and abundant hydroxyl groups (-OH), can form multi-point adsorption on the steel surface, enhancing the compactness of the protective layer. Analysis of HOMO and LUMO distributions shows that HOMO is primarily localized on oxygen- or nitrogen-containing functional groups, indicating strong electron-donating characteristics favorable for coordination with the metal surface. In contrast, the LUMO extends over the molecular backbone, suggesting that these regions can accept electrons from iron atoms, thereby facilitating adsorption onto the metal. SEAEA and LAC exhibit relatively localized HOMO distributions, whereas MICC shows broader HOMO and LUMO distributions, implying potential multi-site adsorption. These results demonstrate that all three molecules are capable of electron exchange with the metal surface, with MICC likely forming a more stable adsorption film due to its multi-hydroxyl structure. In the molecular electrostatic potential (ESP) maps, red regions correspond to high electron density (electron-rich), concentrated around carboxyl (C=O) and hydroxyl oxygen atoms. In contrast, blue regions represent low electron density (electron-poor), mainly around hydrogen atoms. The O and N atoms act as the primary adsorption-active centers, enabling coordination with the iron surface via lone pairs and facilitating an electron donation–back-donation mechanism.

Beyond structural analysis, energy parameters are crucial for assessing molecular reactivity. EHOMO reflects the ability of a molecule to donate electrons to the metal surface; higher values (less harmful) indicate easier electron donation. As shown in Table 3, LAC (–6.94 eV) > SEAEA (–6.97 eV) > MICC (–7.06 eV), suggesting that LAC has slightly stronger electron-donating ability, favoring coordination with iron via carboxyl and amino groups. ELUMO indicates the molecule’s ability to accept electrons from the metal; higher (more positive) values signify stronger electron-accepting capability. MICC exhibits the highest LUMO level (0.81 eV), demonstrating its potential to form a stable adsorption layer through back-donation from the metal. SEAEA and LAC have negative LUMO values, implying that adsorption is predominantly governed by electron donation, with weak back-donation. ΔE characterizes chemical reactivity and adsorption tendency, with smaller gaps indicating higher reactivity. SEAEA (6.59 eV) and LAC (6.62 eV) are lower than MICC (7.87 eV), indicating that amino acid molecules more readily undergo electron exchange and chemical adsorption on the iron surface. Due to its larger structure and multiple bonding sites, MICC mainly adsorbs through multi-point physical interactions to form a protective layer. χ reflects electron-attracting ability, while γ correlates with chemical inertness. MICC shows the lowest χ (3.12 eV) and highest γ (3.94 eV), indicating high chemical stability and resistance to protonation or degradation. SEAEA and LAC display stronger electronic interactions. ΔN is commonly used to describe the electron transfer potential between systems of differing electronegativities, such as a metal surface and an inhibitor molecule [52]. The calculated ΔN indicates that all three molecules have high electron-donating potential, consistent with their multi-hydroxyl, multi-site adsorption structures, which can form dense and continuous protective films on the metal surface. Overall, the anticorrosive effect of C. vulgaris arises from the synergistic combination of chemical adsorption by amino acids and multi-point coverage adsorption by cellulose.

Fukui functions are widely applied to reveal local molecular reactivity, effectively identifying sites prone to electron gain or loss. (nucleophilic attack) reflects the susceptibility of an atom to nucleophilic attack, i.e., its ability to acquire electrons from the metal surface. (electrophilic attack) indicates the susceptibility to electrophilic attack, i.e., the atom’s capacity to donate electrons to the metal surface. The Fukui functions were calculated using Equations (12) and (13) [41].

where and refer to nucleophilic and electrophilic attack, , and represent the charge of the k atom for the neutral, anionic, and cationic inhibitor species, respectively [53].

The Fukui functions derived from DFT calculations are summarized in Table 4. For SEAEA, the highest values are located at N2 (0.370), C3 (0.051), and O9 (0.043), indicating that these atoms readily accept back-donated electrons from the metal surface. The highest values appear at O9 (0.207), O10 (0.155), and C1 (0.252), suggesting that these oxygen atoms and carboxyl carbon can effectively donate electrons to the metal. Thus, N and carboxyl O atoms serve as the primary adsorption-active sites, facilitating coordination or hydrogen-bonded adsorption with the Fe surface. For LAC, the highest values are observed at N2 (0.385), O8 (0.038), and O6 (0.030), while the highest values occur at O8 (0.212), O9 (0.142), and C1 (0.268), indicating that amino nitrogen and carboxyl oxygen play key roles in both electron acceptance and donation. Similar to SEAEA, LAC forms a stable chemisorbed layer on the steel surface through a synergistic N–O adsorption mechanism. In MICC, high values are concentrated at O23 (0.113), O7 (0.090), C13 (0.061), and C14 (0.064), whereas high values are distributed over O23 (0.035), O11 (0.126), and O9 (0.002). These results indicate that the multiple hydroxyl oxygen atoms act as the primary electron donor and acceptor centers, reflecting a multi-site adsorption characteristic. Compared to amino acid molecules, MICC possesses a greater number of active sites with a more uniform distribution, promoting the formation of a dense, multi-point adsorption layer.

Table 4.

Condensed Fukui function of atoms in SEAEA, LAC and MICC structures.

Overall, the Fukui function analysis further confirms that the anticorrosive effect of C. vulgaris on carbon steel in acidic media is primarily mediated through the synergistic adsorption mechanisms of SEAEA, LAC, and MICC.

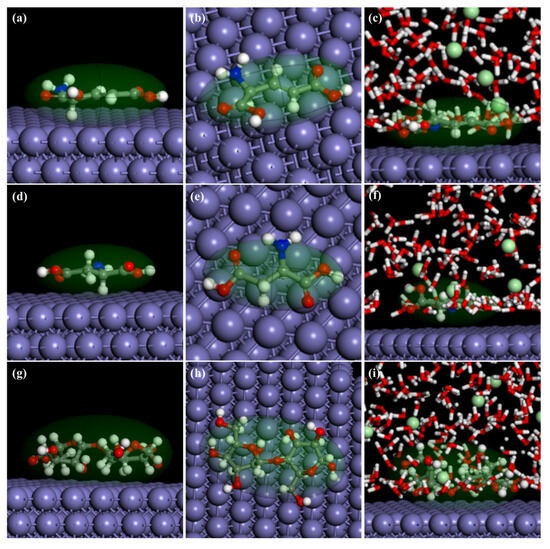

3.10. MD

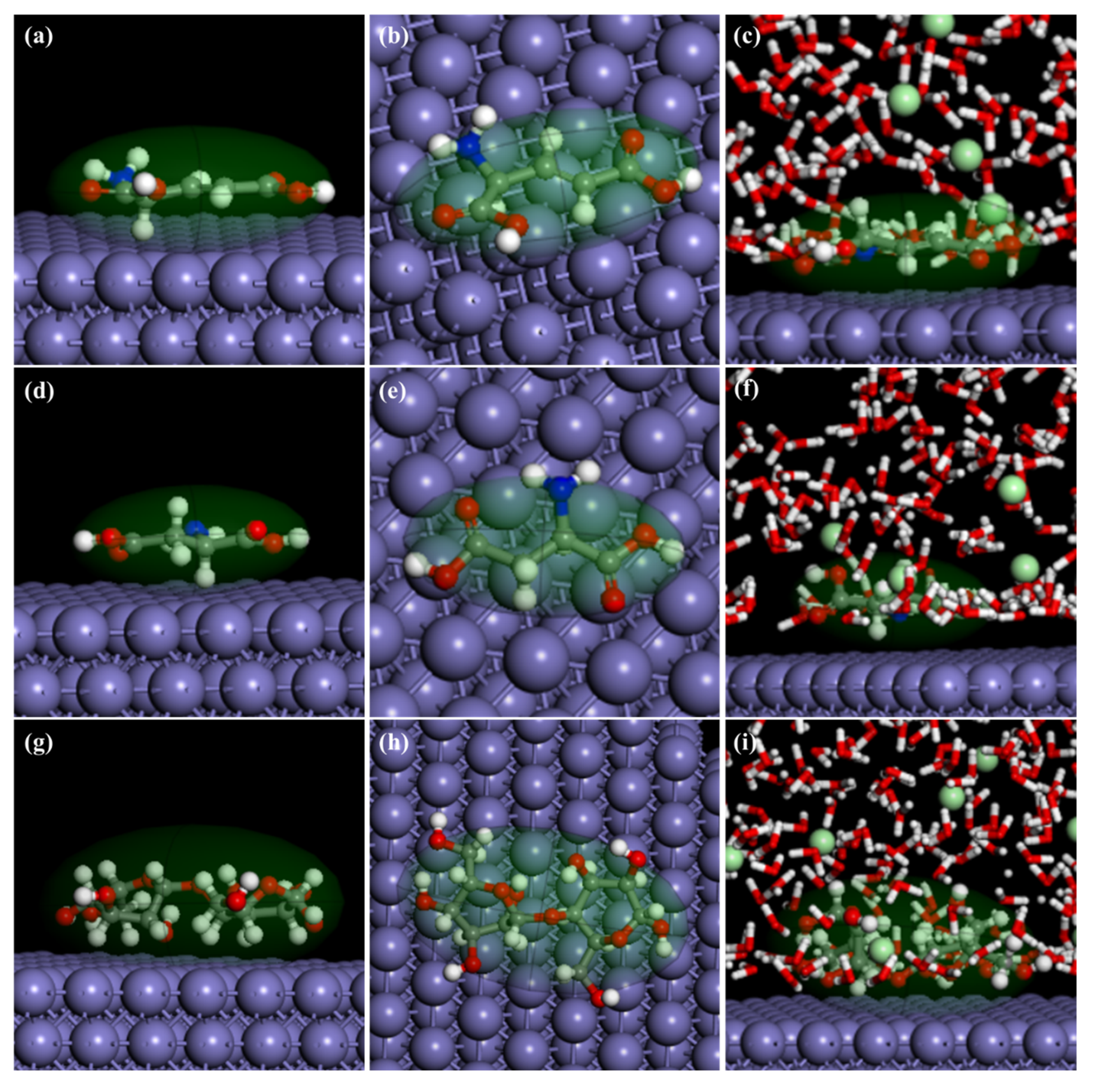

Figure 10 illustrates the interactions between SEAEA, LAC, and MICC molecules and the carbon steel surface under vacuum and in 1 M HCl solution, with the corresponding parameters summarized in Table 5. The binding energy () and interaction energy () between the inhibitor molecules and the carbon steel surface were calculated according to Equations (14) and (15) [41].

where the energy of the Fe(110) surface in the 1 M HCl medium without corrosion inhibitors is designated as , represents the total energy of the simulation system, and denotes the total energy of the corrosion inhibitor.

Figure 10.

The MD simulation of SEAEA, LAC and MICC adsorbed on the Fe(110) surface; (a,b) are side views and top views of SEAEA on the Fe(110) surface in vacuum state, (d,e) are side views and top views of LAC on the Fe(110) surface in vacuum state, (g,h) are side views and top views of MICC on the Fe(110) surface in vacuum state, and (c,f,i) represent side views of SEAEA, LAC and MICC on the Fe(110) surface in 1 M HCl, respectively.

Table 5.

and of SEAEA, LAC and MICC on carbon steel surface in MD simulation.

As shown in Figure 10, under vacuum conditions, SEAEA, LAC, and MICC molecules are adsorbed almost flat on the Fe(110) surface, where the π–electron clouds overlap with the metal surface, indicating strong chemisorption. The oxygen- and nitrogen-containing functional groups of the molecules are oriented toward the iron surface, facilitating the formation of coordination bonds. In the 1 M HCl system, the presence of water molecules together with H+ and Cl− ions leads to a partial relaxation of the adsorption configurations; however, a high surface coverage is still maintained, suggesting strong resistance to desorption and good interfacial stability.

According to the data in Table 5, all three inhibitors exhibit negative values on the Fe(110) surface, confirming that their adsorption is energetically favorable and stable. The Fe/LAC system shows the highest binding energy (−175.26 kJ·mol−1), indicating that LAC has the strongest adsorption affinity toward Fe(110). The presence of polar functional groups such as hydroxyl and carboxyl moieties, whose oxygen atoms can donate electrons to the vacant 3d orbitals of iron, results in strong chemisorption. The Fe/MICC system exhibits a binding energy of −134.32 kJ·mol−1, suggesting a combination of chemisorptive and physisorptive interactions. The Fe/SEAEA system shows the lowest binding energy (−87.98 kJ·mol−1), implying that its interaction with the metal surface is relatively weak and mainly governed by van der Waals and electrostatic forces.

4. Conclusions

A low-cost, eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor was prepared by grinding dried C. vulgaris biomass. Electrochemical measurements indicated a good corrosion inhibition efficiency against carbon steel corrosion by 1 M HCl at three temperatures. The corrosion inhibition efficiency was 88% for 300 mg/L C. vulgaris at 303 K, as determined by the weight loss data. Surface morphology observations supported the good corrosion efficiency. Adsorption isotherm data and the potential of zero charge analysis indicated that both physical and chemical adsorptions of C. vulgaris occurred on the carbon steel surface. DFT and MD simulations reveal that the main components of C. vulgaris—SEAEA, LAC, and MICC—possess multiple active sites and heteroatoms (N and O), which exhibit strong interactions with the carbon steel surface. This strong interfacial interaction serves as a key factor contributing to the corrosion inhibition effect of C. vulgaris on carbon steel in a 1 M HCl solution, providing qualitative mechanistic insights into its inhibition behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, Z.L., X.L., J.L., S.C., G.L., X.W., Y.L., J.W. and J.Y.; software, Z.L., X.L., J.W. and J.Y.; validation, Z.L., Y.L., J.W. and J.Y.; formal analysis, Z.L., X.L., J.L., S.C., G.L., X.W., Y.L., J.W. and J.Y.; investigation, Z.L., X.L., J.W. and J.Y.; resources, Z.L., Y.L., J.W. and J.Y.; data curation, Z.L., X.L. and J.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L., X.L., J.L., S.C., G.L., X.W., Y.L., J.W. and J.Y.; writing—review and editing, Z.L., X.L., J.L., S.C., G.L., X.W., Y.L., J.W. and J.Y.; visualization, Z.L., X.L., J.W. and J.Y.; supervision, Z.L.; project administration, Z.L., J.W. and J.Y.; funding acquisition, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 52401074) and the HDH Cooperation Foundation of Southwest Research Institute of Technology and Engineering (HDHDW59A010301).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Zhong Li was employed by Nanjing Iron and Steel Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Hou, B.S.; Xu, N.; Zhang, Q.H.; Xuan, C.J.; Liu, H.F.; Zhang, G.A. Effect of benzyl substitution at different sites on the inhibition performance of pyrimidine derivatives for mild steel in highly acidic solution. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2019, 95, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, A.R.; El-lateef, H.M.A.; Mohamad, A.D.M. Polyhydrazide incorporated with thiadiazole moiety as novel and effective corrosion inhibitor for C-steel in pickling solutions of HCl and H2SO4. Macromol. Res. 2018, 26, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohare, P.; Ansari, K.R.; Quraishi, M.A.; Obot, I.B. Pyranpyrazole derivatives as novel corrosion inhibitors for mild steel useful for industrial pickling process: Experimental and quantum chemical study. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 52, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ituen, E.B.; Solomon, M.M.; Umoren, S.A.; Akaranta, O. Corrosion inhibition by amitriptyline and amitriptyline based formulations for steels in simulated pickling and acidizing media. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 174, 984–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, H.; Sharma, D.K. Advances in the chemical leaching (inorgano-leaching), bio-leaching and desulphurisation of coals. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2019, 6, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedoročková, A.; Hreus, M.; Raschman, P.; Sučik, G. Dissolution of magnesium from calcined serpentinite in hydrochloric acid. Miner. Eng. 2012, 32, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umoren, S.A.; Eduok, U.M. Application of carbohydrate polymers as corrosion inhibitors for metal substrates in different media: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 140, 314–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, P.B.; Sethuraman, M.G. Natural products as corrosion inhibitor for metals in corrosive media—A review. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Free, M.L.; Woollam, R.; Durnie, W. A review of surfactants as corrosion inhibitors and associated modeling. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 90, 159–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umoren, S.A.; Solomon, M.M. Synergistic corrosion inhibition effect of metal cations and mixtures of organic compounds: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 246–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlović, M.B.P.; Radovanović, M.B.; Tasić, Ž.Z.; Antonijević, M.M. Imidazole based compounds as copper corrosion inhibitors in seawater. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 225, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeachu, I.B.; Obot, I.B.; Sorour, A.A.; Abdul-Rashid, M.I. Green corrosion inhibitor for oilfield application I: Electrochemical assessment of 2-(2-pyridyl) benzimidazole for API X60 steel under sweet environment in NACE brine ID196. Corros. Sci. 2019, 150, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, Y.; Qi, S.; Dong, D.; Cang, H.; Lu, G. The inhibition performance of long-chain alkyl-substituted benzimidazole derivatives for corrosion of mild steel in HCl. Corros. Sci. 2016, 102, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedair, M.A. The effect of structure parameters on the corrosion inhibition effect of some heterocyclic nitrogen organic compounds. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 219, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fakih, A.M.; Abdallah, H.H.; Aziz, M. Experimental and theoretical studies of the inhibition performance of two furan derivatives on mild steel corrosion in acidic medium. Mater. Corros. 2019, 70, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, J.; Ansari, K.R.; Srivastava, V.; Quraishi, M.A.; Obot, I.B. Pyrimidine derivatives as novel acidizing corrosion inhibitors for N80 steel useful for petroleum industry: A combined experimental and theoretical approach. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 49, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, P.B.; Ismail, M.; Ghoreishiamiri, S.; Mirza, J.; Ismail, M.C.; Kakooei, S.; Rahim, A.A. Reviews on corrosion inhibitors: A short view. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2016, 203, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hou, B.; Xiang, J.; Chen, X.; Gu, T.; Liu, H. The performance and mechanism of bifunctional biocide sodium pyrithione against sulfate reducing bacteria in X80 carbon steel corrosion. Corros. Sci. 2019, 150, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Li, X. Inhibition by Ginkgo leaves extract of the corrosion of steel in HCl and H2SO4 solutions. Corros. Sci. 2012, 55, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umoren, S.A. Biomaterials for corrosion protection: Evaluation of mustard seed extract as eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor for X60 steel in acid media. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2016, 30, 1858–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassannejad, H.; Nouri, A. Sunflower seed hull extract as a novel green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in HCl solution. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 254, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokar, M.; Farahani, T.S.; Ramezanzadeh, B. Electrochemical and surface characterizations of morus alba pendula leaves extract (MAPLE) as a green corrosion inhibitor for steel in 1 M HCl. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 63, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odewunmi, N.A.; Umoren, S.A.; Gasem, Z.M. Watermelon waste products as green corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in HCl solution. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibakhshi, E.; Ramezanzadeh, M.; Bahlakeh, G.; Ramezanzadeh, B.; Mahdavian, M.; Motamedi, M. Glycyrrhiza glabra leaves extract as a green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 1 M hydrochloric acid solution: Experimental, molecular dynamics, Monte Carlo and quantum mechanics study. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 255, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsani, A.; Mahjani, M.G.; Hosseini, M.; Safari, R.; Moshrefi, R.; Shiri, H.M. Evaluation of Thymus vulgaris plant extract as an eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor for stainless steel 304 in acidic solution by means of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, electrochemical noise analysis and density functional theory. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 490, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Tan, B.; Bao, H.; Xie, Y.; Mou, Y.; Li, P.; Chen, D.; Shi, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, W. Evaluation of Ficus tikoua leaves extract as an eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in HCl media. Bioelectrochemistry 2019, 128, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, C.; Zebib, B.; Merah, O.; Pontalier, P.-Y.; Vaca-Garcia, C. Morphology, composition, production, processing and applications of Chlorella vulgaris: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 35, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Sun, K.; Ban, J.; Bi, J. Public perception of blue-algae bloom risk in Hongze Lake of China. Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.R.D.; Moreira, D.M.; Kunigami, C.N.; Aranda, D.A.G.; Teixeira, C.M.L.L. Comparison between several methods of total lipid extraction from Chlorella vulgaris biomass. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015, 22, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbetts, S.M.; Whitney, C.G.; MacPherson, M.J.; Bhatti, S.; Banskota, A.H.; Stefanova, R.; McGinn, P.J. Biochemical characterization of microalgal biomass from freshwater species isolated in Alberta, Canada for animal feed applications. Algal Res. 2015, 11, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escapa, C.; Coimbra, R.N.; Paniagua, S.; García, A.I.; Otero, M. Nutrients and pharmaceuticals removal from wastewater by culture and harvesting of Chlorella sorokiniana. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 185, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, J.; Cardoso, C.; Bandarra, N.M.; Afonso, C. Microalgae as healthy ingredients for functional food: A review. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 2672–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupatini, A.L.; Colla, L.M.; Canan, C.; Colla, E. Potential application of microalga Spirulina platensis as a protein source. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Xu, D.; Dao, A.Q.; Zhang, G.; Lv, Y.; Liu, H. Study of corrosion behavior and mechanism of carbon steel in the presence of Chlorella vulgaris. Corros. Sci. 2015, 101, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Sharma, M.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Y.F.; Liu, H. Microbiologically influenced corrosion of 316L stainless steel in the presence of Chlorella vulgaris. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2018, 129, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Tan, B.; Chen, S. Evaluation of Ginkgo leaf extract as an eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor of X70 steel in HCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2018, 133, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Asif, M.; Zhang, T.; Hou, B.; Li, Y.; Xia, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, H. Corrosion Behavior of Aspergillus niger on 7075 Aluminum Alloy and the Inhibition Effect of Zinc Pyrithione Biocide. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, G39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiong, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Xia, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, H. Study of the corrosion behavior of Aspergillus niger on 7075-T6 aluminum alloy in a high salinity environment. Bioelectrochemistry 2019, 129, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.A.; Hou, X.M.; Hou, B.S.; Liu, H.F. Benzimidazole Derivatives as Novel Inhibitors for the Corrosion of Mild Steel in Acidic Solution: Experimental and Theoretical Studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 278, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüce, A.O.; Solmaz, R.; Kardaş, G. Investigation of inhibition effect of rhodanine-N-acetic acid on mild steel corrosion in HCl solution. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 131, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Chen, L.; Xie, B.; Lai, C.; He, J.Y.; Feng, J.S.; Yang, Y.G.; Ji, R.W.; Liu, M.N. Two semi flexible nonplanar double Schiff bases as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in HCl solution: Experimental and theoretical investigations. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkorn, T.; Klotz, B.; Sørensen, S.; Patroescu, I.V.; Barnes, I.; Becker, K.H.; Platt, U. Gas-phase absorption cross sections of 24 monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the UV and IR spectral ranges. Atmos. Environ. 1999, 33, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtarinezhad, A.; Shirazi, F.H.; Vatanpour, H.; Mohamazadehasl, B.; Panahyab, A.; Nakhjavani, M. FTIR-Microspectroscopy Detection of Metronidazole Teratogenic Effects on Mice Fetus. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2014, 13, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Alhazmi, A.H. FT-IR Spectroscopy for the Identification of Binding Sites and Measurements of the Binding Interactions of Important Metal Ions with Bovine Serum Albumin. Sci. Pharm. 2019, 87, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, C.L.M.; Shore, R.F.; Pereira, M.G.; Martin, F.L. Assessing Binary Mixture Effects from Genotoxic and Endocrine Disrupting Environmental Contaminants Using Infrared Spectroscopy. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 13399–13412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aja, M.; Jaya, M.; Nair, K.V.; Joe, I.H. FT-IR spectroscopy as a sentinel technology in earthworm toxicology. Spectrochim. Acta. A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 120, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, L.J.; Izawa, M.R.M.; Banerjee, N.R. Infrared spectroscopic characterization of organic matter associated with microbial bioalteration textures in basaltic glass. Astrobiology 2011, 11, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voll, D.; Beran, A. Dehydration process and structural development of cordierite ceramic precursors derived from FTIR spectroscopic investigations. Phys. Chem. Miner. 2002, 29, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, A.; Sokolova, E.; Raicheva, S.; Christov, M. AC and DC study of the temperature effect on mild steel corrosion in acid media in the presence of benzimidazole derivatives. Corros. Sci. 2003, 45, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, J.; Srivastava, V.; Quraishi, M.A.; Chauhan, D.S.; Lgaz, H.; Chung, I.-M. Polar group substituted imidazolium zwitterions as eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acid solution. Corros. Sci. 2020, 172, 108665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basik, M.; Mobin, M. Chondroitin sulfate as potent green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 1 M HCl. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1214, 128231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murmu, M.; Saha, S.K.; Murmu, N.C.; Banerjee, P. Effect of stereochemical conformation into the corrosion inhibitive behaviour of double azomethine based Schiff bases on mild steel surface in 1 mol L−1 HCl medium: An experimental, density functional theory and molecular dynamics simulation study. Corros. Sci. 2019, 146, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messali, M.; Larouj, M.; Lgaz, H.; Rezki, N.; Al-Blewi, F.F.; Aouad, M.R.; Chaouiki, A.; Salghi, R.; Chung, I.-M. A new schiff base derivative as an effective corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic media: Experimental and computer simulations studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1168, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.